Abstract

We report the current best estimate of the effects of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) in the treatment of major depression (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PAD) and social anxiety disorder (SAD), taking into account publication bias, the quality of trials, and the influence of waiting list control groups on the outcomes. In our meta‐analyses, we included randomized trials comparing CBT with a control condition (waiting list, care‐as‐usual or pill placebo) in the acute treatment of MDD, GAD, PAD or SAD, diagnosed on the basis of a structured interview. We found that the overall effects in the 144 included trials (184 comparisons) for all four disorders were large, ranging from g=0.75 for MDD to g=0.80 for GAD, g=0.81 for PAD, and g=0.88 for SAD. Publication bias mostly affected the outcomes of CBT in GAD (adjusted g=0.59) and MDD (adjusted g=0.65), but not those in PAD and SAD. Only 17.4% of the included trials were considered to be high‐quality, and this mostly affected the outcomes for PAD (g=0.61) and SAD (g=0.76). More than 80% of trials in anxiety disorders used waiting list control groups, and the few studies using other control groups pointed at much smaller effect sizes for CBT. We conclude that CBT is probably effective in the treatment of MDD, GAD, PAD and SAD; that the effects are large when the control condition is waiting list, but small to moderate when it is care‐as‐usual or pill placebo; and that, because of the small number of high‐quality trials, these effects are still uncertain and should be considered with caution.

Keywords: Cognitive behavior therapy, major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, meta‐analysis, publication bias, quality of trials, waiting list control groups

Every year almost 20% of the general population suffers from a common mental disorder, such as depression or an anxiety disorder1. These conditions not only result in personal suffering for patients and their families, but also in huge economic costs, in terms of both work productivity loss and health and social care expenditures2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Several evidence‐based treatments are available for common mental disorders, including pharmacological and psychological interventions. Many patients receive pharmacological treatments, and these numbers are increasing in high‐income countries7. Psychological treatments are equally effective in the treatment of depression8 and anxiety disorders9, 10, 11. However, they are less available or accessible12, especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries. At the same time, about 75% of patients prefer psychotherapy over the use of medication13.

The most extensively tested form of psychotherapy is cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). Dozens of trials and several meta‐analyses have shown that CBT is effective in treating depression8, 14 and anxiety disorders9, 10, 11. However, in recent years, it has become clear that the effects of CBT and other psychotherapies have been considerably overestimated due to at least three reasons.

The first reason is publication bias15, 16. This refers to the tendency of authors to submit, or journals to accept, manuscripts for publication based on the direction or strength of the study's findings17. There is considerable indirect evidence of publication bias in psychotherapy research, based on excess publication of small studies with large effect sizes16. Moreover, there is also direct evidence of publication bias: a recent study found that almost one quarter of trials of psychotherapy for adult depression funded by the US National Institutes of Health were not published15. After adding the effect sizes of these unpublished trials to those of the published ones, the mean effect size for psychotherapy dropped by more than 25%.

The second reason why the effects of psychotherapies have been overestimated is that the quality of many trials is suboptimal. In a meta‐analysis of 115 trials of psychotherapy for depression, only 11 met all basic indicators of quality, and the effect sizes of these trials were considerably smaller than those of lower quality ones18. However, that meta‐analysis only included trials up to 2008, and since then many new studies have been conducted. Because more recent trials are typically of a better quality than older ones, it is not known what the current best estimate of the effect size of CBT is after taking these newer studies into account.

A third reason why the effects of psychotherapy have been overestimated is that many trials have used waiting list control groups. Although all control conditions in psychotherapy trials have their own problems19, 20, the improvement found in patients on waiting lists has been found to be lower than that expected on the basis of spontaneous remission19. It has been suggested, therefore, that waiting list is in fact a “nocebo” (the opposite of a placebo; an inert treatment that appears to cause an adverse effect) and that trials using it considerably overestimate the effects of psychological treatments21. Other control conditions, such as care‐as‐usual and pill placebo, can allow a better estimate of the true effect size of CBT.

In the present paper, we report the most up‐to‐date and accurate estimate of the effects of CBT in the treatment of major depression (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PAD) and social anxiety disorder (SAD), taking into account the three above‐mentioned major problems of the existing psychotherapy research: publication bias, low quality of trials, and the nocebo effect of waiting list control groups.

METHODS

Identification and selection of studies

We searched four major bibliographic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase and the Cochrane database of randomized trials) by combining terms (both MeSH terms and text words) indicative of psychological treatment and either SAD (social phobia, social anxiety, public‐speaking anxiety), GAD (worry, generalized anxiety), or PAD with or without agoraphobia (panic, panic disorder), with filters for randomized controlled trials. We also checked the references of earlier meta‐analyses on psychological treatments for the included disorders. The deadline for the searches was August 14, 2015.

For the identification of trials of CBT for MDD, we used an existing database22 updated to January 2016 by combining terms indicative of psychological treatment and depression (both MeSH terms and text words).

We included randomized trials in which CBT was directly compared with a control condition (waiting list, care‐as‐usual or pill placebo) in adults with MDD, GAD, PAD or SAD. Only trials in which recruited subjects met diagnostic criteria for the disorder according to a structured diagnostic interview – such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID), the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) or the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) – were included.

In addition to any therapy in which cognitive restructuring was one of the core components, we also included purely behavioral therapies, i.e., trials of behavioral activation for depression and exposure for anxiety disorders. We included therapies that used individual, group and guided self‐help formats, but excluded self‐guided therapies without any professional support, because their effects have been found to be considerably smaller than other formats23. Studies on therapies delivering only (applied) relaxation were excluded, as were studies on eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), interpersonal or psychodynamic therapy, virtual reality therapy, transdiagnostic therapies, as well as studies in which CBT was combined with pill placebo.

In order to keep heterogeneity as low as possible, we included only studies using waiting list, care‐as‐usual or pill placebo control groups. Care‐as‐usual was defined broadly as anything patients would normally receive, as long as it was not a structured type of psychotherapy. Psychological placebo conditions were not included, because they have considerable effects on depression24 and probably also on anxiety disorders19. Comorbid mental or somatic disorders were not used as an exclusion criterion. Studies on inpatients and on adolescents or children (below 18 years of age) were excluded, as were studies recruiting patients with other types of depressive disorders than MDD (dysthymia or minor depression). We also excluded maintenance studies, aimed at people who already had a partial or complete remission after an earlier treatment, and studies that did not report sufficient data to calculate standardized effect sizes. Studies in English, German and Dutch were considered for inclusion.

Quality assessment and data extraction

We assessed the quality of included studies using four criteria of the “risk of bias” assessment tool developed by the Cochrane Collaboration25. Although “risk of bias” and quality are not synonyms25, the former can be seen as an indicator of the quality of studies. The four criteria were: adequate generation of allocation sequence; concealment of allocation to conditions; blinding of assessors; and dealing with incomplete outcome data (this was assessed as positive when intention‐to‐treat analyses were conducted, meaning that all randomized patients were included in the analyses). The assessment of the quality of included studies was conducted by two independent researchers, and disagreements were solved through discussion.

We also coded participant characteristics (disorder, recruitment method, target group); characteristics of the psychotherapies (treatment format, number of sessions); and general characteristics of the studies (country where the study was conducted, year of publication).

Meta‐analyses

For each comparison between a psychotherapy and a control condition, the effect size indicating the difference between the two groups at post‐test was calculated (Hedges’ g). Effect sizes of 0.8 can be assumed to be large, while effect sizes of 0.5 are moderate, and effect sizes of 0.2 are small26. Effect sizes were determined by subtracting (at post‐test) the average score of the psychotherapy group from the average score of the control group, and dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation. Because some studies had relatively small sample sizes, we corrected the effect size for small sample bias27. If means and standard deviations were not reported, we calculated the effect size using dichotomous outcomes, and if these were not available either, we used other statistics (such a t or p value).

In order to calculate effect sizes, we used all measures examining depressive symptoms, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI28 or BDI‐II29) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression30, or anxiety symptoms, such as the Beck Anxiety Inventory31, the Penn State Worry Questionnaire32, the Fear Questionnaire33, and the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale34. We did not use measures of mediators, dysfunctional thinking, quality of life or generic severity. To calculate pooled mean effect sizes, we used the Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis (CMA) software (version 3.3.070). Because we expected considerable heterogeneity among the studies, we employed a random effects pooling model in all analyses.

Numbers‐needed‐to‐treat (NNT) were calculated using the formulae provided by Furukawa35, in which the control group's event rate was set at a conservative 19% (based on the pooled response rate of 50% reduction of symptoms across trials of psychotherapy for depression)36. As a test of homogeneity of effect sizes, we calculated the I2 statistic (a value of 0 indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values indicate increasing heterogeneity, with 25 as low, 50 as moderate, and 75 as high heterogeneity)37. We calculated 95% confidence intervals around I2 using the non‐central chi‐squared‐based approach within the Heterogi module for Stata38, 39.

We conducted subgroup analyses according to the mixed effects model, in which studies within subgroups are pooled with the random effects model, while tests for significant differences between subgroups are conducted with the fixed effects model. For continuous variables, we used meta‐regression analyses to test whether there was a significant relationship between the continuous variable and the effect size, as indicated by a Z value and an associated p value. Multivariate meta‐regression analyses, with the effect size as the dependent variable, were conducted using CMA.

We tested for publication bias by inspecting the funnel plot on primary outcome measures and by Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill procedure40, which yields an estimate of the effect size after the publication bias has been taken into account. We also conducted Egger's test of the intercept to quantify the bias captured by the funnel plot and to test whether it was significant.

RESULTS

Selection and inclusion of trials

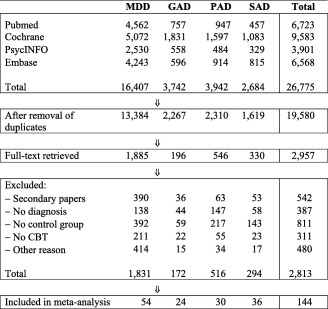

After examining a total of 26,775 abstracts (19,580 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 2,957 full‐text papers for further consideration. We excluded 2,813 of the retrieved papers. The PRISMA flow chart describing the inclusion process and the reasons for exclusion is presented in Figure 1. A total of 144 trials met inclusion criteria for this meta‐analysis: 54 on MDD, 24 on GAD, 30 on PAD, and 36 on SAD.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion of trials. MDD – major depression, GAD – generalized anxiety disorder, PAD – panic disorder, SAD – social anxiety disorder, CBT – cognitive behavior therapy

Characteristics of included trials

The 144 trials included a total of 184 comparisons between CBT and a control condition (63 comparisons for MDD, 31 for GAD, 42 for PAD, and 48 for SAD). A total of 11,030 patients were enrolled (6,229 in the CBT groups, 2,469 in the waiting list control groups, 1,823 in the care‐as‐usual groups and 509 in the pill placebo groups). A total of 113 trials were aimed at adults in general and 31 at other more specific target groups. Eighty trials recruited patients (also) from the community, 51 recruited exclusively from clinical populations, and 13 used other recruitment methods. Sixty‐seven trials were conducted in North America, 14 in the UK, 36 in other European countries, 15 in Australia, 4 in East Asia, and 8 in other geographic areas. Of all included trials, 44 (30.6%) were conducted in 2010 or later.

CBT was delivered in individual format in 87 comparisons, in group format in 53, in guided self‐help format in 35, and in a mixed or another format in 9. The number of treatment sessions ranged from one to 25.

Quality assessment

Sixty trials reported an adequate sequence generation, while the other 84 did not. A total of 46 trials reported allocation to conditions by an independent (third) party. Seventy trials reported blinding of outcome assessors and 57 conducted intention‐to‐treat analyses. Only 25 trials (17.4%) met all four quality criteria, 62 met two or three criteria, and the remaining 57 met one or none of the criteria. Of the trials conducted in 2010 or later, 29.5% were rated as high‐quality, compared to 12.0% of the older studies.

Effects of CBT on MDD

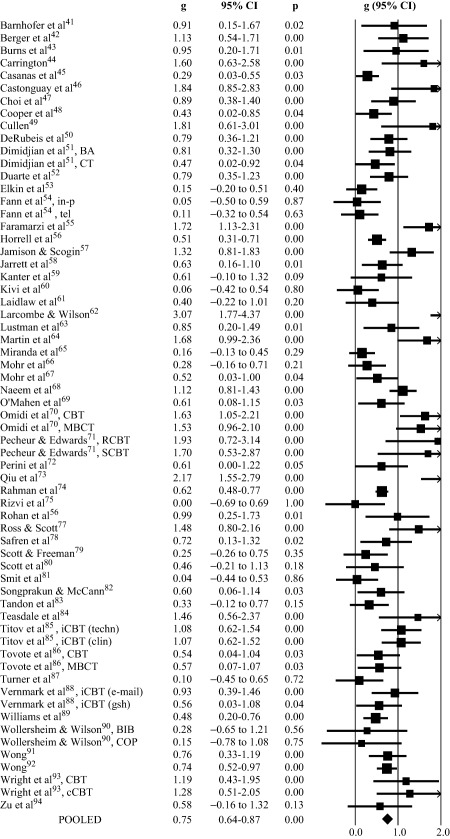

The pooled effect size of the 63 comparisons between CBT and control conditions in MDD41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94 was g=0.75 (95% CI: 0.64‐0.87), with high heterogeneity (I2=71). This effect size corresponds to a NNT of 3.86. Studies using a waiting list control group had significantly (p=0.002) larger effect sizes (g=0.98; 95% CI: 0.80‐1.17) than those using care‐as‐usual (g=0.60; 95% CI: 0.45‐0.75) and pill placebo control groups (g=0.55; 95% CI: 0.28‐0.81) (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1.

Effects of cognitive behavior therapy for major depression (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PAD) and social anxiety disorder (SAD) compared to control conditions

| N | g | 95% CI | p | I2 | 95% CI | p | NNT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD | |||||||||

| All control conditions | All studies | 63 | 0.75 | 0.64‐0.87 | <0.001 | 71 | 62‐77 | 3.86 | |

| High‐quality studies | 11 | 0.73 | 0.46‐1.00 | <0.001 | 78 | 56‐86 | 3.98 | ||

| Adjusted for publication bias | 71 | 0.65 | 0.53‐0.78 | 76 | 69‐80 | 4.55 | |||

| Type of control | Waiting list | 28 | 0.98 | 0.80‐1.17 | <0.001 | 68 | 50‐77 | 0.002 | 2.85 |

| Care‐as‐usual | 30 | 0.60 | 0.45‐0.75 | <0.001 | 69 | 54‐78 | 4.99 | ||

| Pill placebo | 5 | 0.55 | 0.28‐0.81 | <0.001 | 45 | 0‐78 | 5.51 | ||

| High‐quality studies | Waiting list | 6 | 0.93 | 0.49‐1.37 | <0.001 | 82 | 56‐90 | 0.06 | 3.02 |

| Care‐as‐usual | 5 | 0.43 | 0.16‐0.70 | 0.002 | 46 | 0‐79 | 7.29 | ||

| GAD | |||||||||

| All control conditions | All studies | 31 | 0.80 | 0.67‐0.93 | <0.001 | 33 | 0‐56 | 3.58 | |

| High‐quality studies | 9 | 0.82 | 0.60‐1.04 | <0.001 | 46 | 0‐73 | 3.49 | ||

| Adjusted for publication bias | 42 | 0.59 | 0.44‐0.75 | 62 | 44‐72 | 5.08 | |||

| Type of control | Waiting list | 24 | 0.85 | 0.72‐0.99 | <0.001 | 13 | 0‐47 | <0.001 | 3.35 |

| Care‐as‐usual | 4 | 0.45 | 0.26‐0.64 | <0.001 | 0 | 0‐68 | 6.93 | ||

| Pill placebo | 3 | 1.32 | 0.83‐1.81 | <0.001 | 0 | 0‐73 | 2.08 | ||

| High‐quality studies | Waiting list | 8 | 0.88 | 0.67‐1.10 | <0.001 | 33 | 0‐69 | 0.05 | 3.22 |

| Care‐as‐usual | 1 | 0.45 | 0.08‐0.83 | 0.02 | 0 | 6.93 | |||

| PAD | |||||||||

| All control conditions | All studies | 42 | 0.81 | 0.59‐1.04 | <0.001 | 77 | 69‐82 | 3.53 | |

| High‐quality studies | 4 | 0.61 | 0.27‐0.96 | 0.001 | 26 | 0‐75 | 4.89 | ||

| Type of control | Waiting list | 33 | 0.96 | 0.70‐1.23 | <0.001 | 77 | 67‐82 | <0.001 | 2.92 |

| Care‐as‐usual | 4 | 0.27 | −0.12 to 0.65 | 0.17 | 31 | 0‐77 | 12.25 | ||

| Pill placebo | 5 | 0.28 | 0.03‐0.54 | 0.03 | 8 | 0‐67 | 11.77 | ||

| High‐quality studies | Waiting list | 4 | 0.61 | 0.27‐0.96 | 0.001 | 26 | 0‐75 | 4.89 | |

| SAD | |||||||||

| All control conditions | All studies | 48 | 0.88 | 0.74‐1.03 | <0.001 | 64 | 50‐73 | 3.22 | |

| High‐quality studies | 8 | 0.76 | 0.47‐1.06 | <0.001 | 71 | 25‐84 | 3.80 | ||

| Type of control | Waiting list | 40 | 0.98 | 0.83‐1.14 | <0.001 | 64 | 47‐73 | <0.001 | 2.85 |

| Care‐as‐usual | 3 | 0.44 | 0.12‐0.77 | 0.01 | 23 | 0‐79 | 7.11 | ||

| Pill placebo | 5 | 0.47 | 0.24‐0.70 | <0.001 | 0 | 0‐64 | 6.59 | ||

| High‐quality studies | Waiting list | 5 | 1.00 | 0.61‐1.40 | <0.001 | 71 | 0‐87 | 0.03 | 2.79 |

| Care as usual | 2 | 0.30 | −0.04 to 0.64 | 0.08 | 0 | 10.91 | |||

| Pill placebo | 1 | 0.57 | 0.20‐0.93 | 0.002 | 0 | 5.29 |

NNT – Number‐needed‐to‐treat

Figure 2.

Effects of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for major depression compared to control conditions: forest plot. BA – behavioral activation, CT – cognitive therapy, in‐p – in person, tel – telephone, MBCT – mindfulness based CBT, RCBT – religious CBT, SCBT – secular CBT, iCBT – Internet‐delivered CBT, techn – supported by a technician, clin – supported by a clinician, e‐mail – supervised by e‐mail, gsh – guided self‐help format, BIB – bibliotherapy, COP – coping, cCBT – computerized CBT

Only 11 of the 63 studies were rated as being high‐quality. The effect size in these studies was similar to that in the total pool (g=0.73; 95% CI: 0.46‐1.00; I2=78). No high‐quality study used a pill placebo control group. The difference between waiting list and care‐as‐usual among the high‐quality studies was not significant (p=0.06), but this may be related to the small number of those studies.

Egger's test indicated considerable asymmetry of the funnel plot (intercept: 1.54; 95% CI: 0.59‐2.50; p=0.001). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill procedure also indicated considerable publication bias (number of imputed studies: 8; adjusted effect size: g=0.65; 95% CI: 0.53‐0.78; I2=76). For high‐quality studies, no indication for publication bias was found (but this may again be related to the small number of those studies).

Effects of CBT on GAD

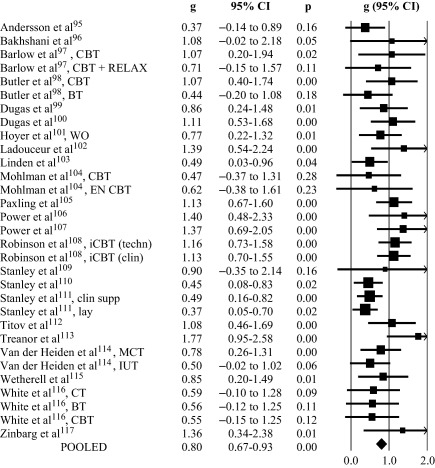

The pooled effect size of the 31 comparisons between CBT and control conditions in GAD95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117 was g=0.80 (95% CI: 0.67‐0.93; NNT=3.58), with low to moderate heterogeneity (I2=33) (Table 1 and Figure 3). The vast majority of studies (24 of 31) used a waiting list control group. Studies using a pill placebo control group (g=1.32) had a significantly (p<0.001) larger effect than those using a waiting list (g=0.85) or care‐as‐usual control group (g=0.45). The number of studies using pill placebo (N=3) and care‐as‐usual control groups (N=4) was very small, however (Table 1 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for generalized anxiety disorder compared to control conditions: forest plot. RELAX – relaxation, BT – behavior therapy, WO – worry exposure, EN CBT – enhanced CBT, iCBT – Internet‐delivered CBT, techn – technician assistance, clin – clinician assistance, clin supp – supported by a clinician, lay – lay provider, MCT – metacognitive therapy, IUT – intolerance‐of‐uncertainty therapy, CT – cognitive therapy

Only 9 of the 31 studies were rated as high‐quality, and 8 of these used a waiting list control group, so the effects of care‐as‐usual and pill placebo among high‐quality studies could not be estimated.

Egger's test was significant (intercept: 1.60; 95% CI: 0.38‐2.83; p=0.006). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill procedure resulted in an adjusted effect size of g=0.59 (95% CI: 0.44‐0.75; I2=62; number of imputed studies: 11). For high‐quality studies, no indication for publication bias was found (but this may again be related to the small number of those studies).

Effects of CBT on PAD

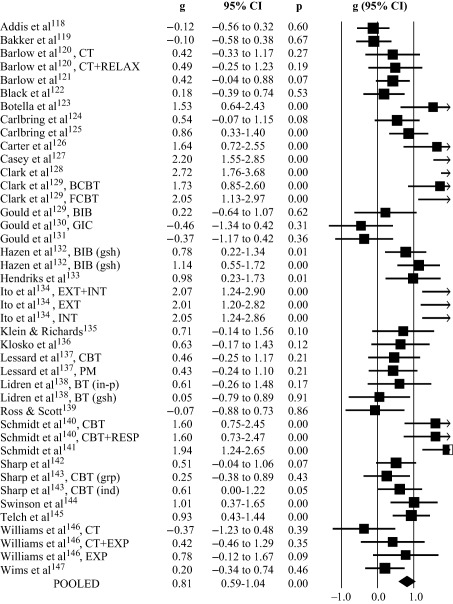

The 42 comparisons between CBT and control conditions in PAD118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147 resulted in a pooled effect size of g=0.81 (95% CI: 0.59‐1.04; I2=77; NNT=3.53). In the vast majority of the comparisons (N=33), a waiting list control condition was used. The difference between studies using a waiting list (g=0.96) and either care‐as‐usual (g=0.27) or pill placebo (g=0.28) was significant (p<0.001). The four comparisons of CBT versus care‐as‐usual even indicated a non‐significant effect size (g=0.27; 95% CI: −0.12 to 0.65; p=0.17) (Table 1 and Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for panic disorder compared to control conditions: forest plot. CT – cognitive therapy, RELAX – relaxation, BCBT – brief CBT, FCBT – full CBT, BIB – bibliotherapy, GIC – guided imaginal coping, gsh – guided self help, grp – group format, EXT – external cues, INT – interoceptive, PM – panic management, in‐p – in person, RESP – respiratory training, ind – individual format, EXP – exposure

The four high‐quality studies all used a waiting list control group and resulted in an effect size of g=0.61 (95% CI: 0.27‐0.96).

Although Egger's test indicated significant asymmetry of the funnel plot (intercept: 3.62; 95% CI: 0.90‐6.34; p=0.005), Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill procedure did not indicate any missing studies and therefore the adjusted and unadjusted effect sizes were the same. In the four high‐quality studies, no indication for publication bias was found.

Effects of CBT on SAD

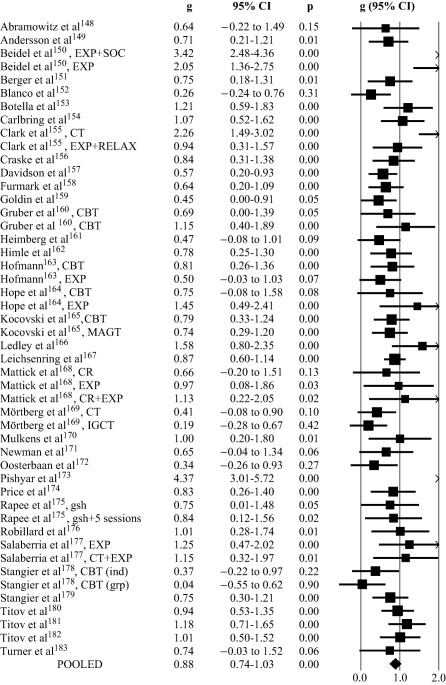

The 48 comparisons between CBT and a control condition148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183 resulted in a pooled effect size of g=0.88 (95% CI: 0.74‐1.03; I2=64; NNT=3.22). Again, the large majority of studies used a waiting list control group (N=40), with only three using care‐as‐usual and five pill placebo. The studies using a waiting list control group resulted in significantly (p<0.001) larger effect sizes (g=0.98) than those using a pill placebo (g=0.47) or care‐as‐usual control group (g=0.44) (Table 1 and Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for social anxiety disorder compared to control conditions: forest plot. EXP – exposure, SOC – social skills, CT – cognitive therapy, RELAX – relaxation, cCBT – computerized CBT, MAGT – mindfulness acceptance group therapy, CR – cognitive restructuring, IGCT – intensive group CT, gsh – guided self help, ind – individual format, grp – group format

Only eight studies were rated as high‐quality, and five of these used a waiting list control group. This implies that for SAD there are not enough high‐quality studies to assess the effects of CBT compared to care‐as‐usual or pill placebo.

Egger's test pointed at significant asymmetry of the funnel plot (intercept: 2.46; 95% CI: 0.96‐3.96; p=0.001), but Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill procedure did not indicate missing studies and the adjusted and unadjusted effect sizes were the same.

Multivariate meta‐regression analyses

We conducted four separate analyses, for each disorder, with the effect size as the dependent variable and characteristics of the participants (adults in general or more specific populations), the intervention (format and number of sessions) and the study in general (type of control group, quality and geographic area) as predictors. As shown in Table 2, very few predictors were significant in these analyses, possibly because of the relatively small number of studies per disorder and the relatively large number of predictors.

Table 2.

Standardized regression coefficients of characteristics of studies on cognitive behavior therapy for major depression (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PAD) and social anxiety disorder (SAD) compared to control conditions

| MDD | GAD | PAD | SAD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff | SE | p | Coeff | SE | p | Coeff | SE | p | Coeff | SE | p | ||

| Quality of trial | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.46 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.94 | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.43 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.92 | |

| Control condition | Waiting list | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||||

| Care‐as‐usual | −0.43 | 0.15 | 0.01 | −0.30 | 0.38 | 0.43 | −0.61 | 0.41 | 0.69 | −0.67 | 0.46 | 0.15 | |

| Pill placebo | −0.44 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.15 | −0.67 | 0.34 | 0.05 | −0.53 | 0.29 | 0.08 | |

| Adults vs. specific target groups | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.95 | −0.43 | 0.28 | 0.14 | −0.07 | 0.38 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.38 | |

| Format | Individual | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||||

| Group | −0.23 | 0.21 | 0.28 | −0.17 | 0.23 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.37 | −0.06 | 0.25 | 0.83 | |

| Guided self‐help | −0.32 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.84 | −0.36 | 0.30 | 0.24 | −0.06 | 0.36 | 0.86 | |

| Mixed/other | −0.28 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.89 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.65 | |

| Number of sessions | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.67 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.19 | |

| Geographic area | North America | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||||

| Europe | −0.02 | 0.19 | 0.92 | −0.51 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.25 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.24 | 0.59 | |

| Australia | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.29 | −0.19 | 0.30 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.20 | |

| Other | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.04 | −0.78 | 0.66 | 0.25 | 1.58 | 0.48 | 0.003 | ||||

Significant p values are highlighted in bold prints

DISCUSSION

In this study, we aimed to establish the most up‐to‐date and accurate estimate of the effects of CBT in the treatment of MDD, GAD, PAD and SAD. We also aimed to examine whether the problems of publication bias, low quality of trials, and the use of waiting list control groups have an impact on the effect sizes. We found that the overall effects for all four disorders were large, ranging from g=0.75 for MDD to g=0.80 for GAD, g=0.81 for PAD, and g=0.88 for SAD.

The first problem, publication bias, mostly affected the outcomes of CBT for GAD and MDD. For GAD, it was estimated that about one quarter of the studies were missing and, after adjusting for these missing studies, the effect size dropped from g=0.80 to g=0.59. For MDD, 14% of the studies were missing, and the pooled effect size dropped from g=0.75 to g=0.65. However, this was a relatively small drop compared to that reported in other studies on publication bias in psychotherapies for MDD15, 18, 184. This may be due to the fact that we used more stringent inclusion criteria for this meta‐analysis (only patients meeting diagnostic criteria for MDD; only waiting list, treatment‐as‐usual or pill placebo control groups; only CBT). In PAD and SAD, we found few indications of publication bias.

The second problem we aimed to examine was the quality of trials. We found that the methodological quality in most studies was low or unknown. We evaluated the quality by the Cochrane “risk of bias” assessment tool, and found that across all disorders only 25 trials (17.4%) were rated as high‐quality. The effect size was lower in high‐quality studies for PAD (g=0.61 compared to g=0.81 in all studies) and SAD (g=0.76 compared to g=0.88 in all studies). We did not find strong indications that the quality of trials was associated with the effect size in MDD and GAD. Although we did not find a strong association between effect size and quality of trials for all disorders, the small number of high‐quality studies still means that the overall effect sizes we found for all four disorders are uncertain.

The third problem we aimed to examine was the influence of waiting list control groups on the effects of CBT. We found that the vast majority of studies for the three anxiety disorders used a waiting list control group (77.4% of the comparisons for GAD, 78.6% for PAD, and 83.3% for SAD). In MDD, the number of studies using care‐as‐usual and pill placebo control conditions was larger, but still 44.4% (28 out of 63) of the included studies used a waiting list control group. This means that much of the evidence on the effects of CBT is based on the use of waiting list control groups. As indicated earlier, improvements found in patients on waiting lists are lower than can be expected on the basis of spontaneous remission19, 185. Waiting list is probably a “nocebo”21, considerably overestimating the effects of psychological treatments. This was confirmed in our meta‐analysis, in which we found for each of the disorders that studies with a waiting list control group resulted in significantly higher effect sizes than those with a care‐as‐usual or pill placebo control group.

The few studies on anxiety disorders that used care‐as‐usual or pill placebo control groups indicated small to moderate effect sizes. In the four studies comparing CBT for PAD with care‐as‐usual, the effect size was even non‐significant (p=0.17). Furthermore, because of the small number of studies, and the even smaller number of high‐quality studies, the effects of CBT in anxiety disorders are quite uncertain.

An exception to the small to moderate effects of CBT in anxiety disorders was the group of studies comparing CBT to pill placebo for GAD. These studies resulted in a very large effect size (g=1.32). However, because of the small number of trials and the low quality of all three of them, these results should be considered with caution.

One reason to conduct this meta‐analysis was to examine whether the quality of trials has increased in recent years. Indeed, 29.5% of the studies conducted in 2010 or later were rated as high‐quality, while that was true for only 12.0% of the older studies. Furthermore, 52.0% of all high‐quality studies were conducted in 2010 or later. This is likely to have led to a more accurate estimate of effect sizes.

The present study has several strengths, including the broad scope of the meta‐analyses, covering four common mental disorders, the rigorous selection and assessment of the trials, and their relatively large number.

One possible limitation is that we used strict inclusion criteria, only focusing on trials in which patients met diagnostic criteria for the disorder according to a structured interview and trials in which either a waiting list, care‐as‐usual or pill placebo control group was used. We did not include studies in which, for example, generic counselling was used as a control condition. This may contribute to explain the small number of trials comparing CBT with control conditions other than waiting lists, especially in anxiety disorders and among the sets of high‐quality studies. Furthermore, care‐as‐usual control groups can vary considerably depending on the country and the treatment setting where the therapy is offered, and may therefore be too heterogeneous to allow a reliable assessment of the effects across studies. Finally, we only focused on short‐term outcomes, because only few studies reported long‐term outcomes and the follow‐up periods differed considerably.

On the basis of our data, we conclude that CBT is probably effective in the treatment of MDD, GAD, PAD and SAD, and that the effects are large when compared to waiting list control groups, but small to moderate when compared to more conservative control groups, such as care‐as‐usual and pill placebo. Because of the small number of high‐quality studies, these effects are still uncertain and should be considered with caution.

REFERENCES

- 1. Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta‐analysis 1980‐2013. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:476‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;382:1575‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jacobi F et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2011;21:718‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hu T‐W. Perspectives: an international review of the national cost estimates of mental illness, 1990‐2003. J Mental Health Policy Econ 2006;9:3‐13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P et al. Scaling‐up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:415‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bloom DE, Cafiero E, Jané‐Llopis E et al. The global economic burden of non‐communicable diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:848‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL et al. The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: a meta‐analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry 2013;12:137‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Acarturk C, Cuijpers P, van Straten A et al. Psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: a meta‐analysis. Psychol Med 2009;39:241‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole S et al. Psychological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a meta‐analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2014;34:130‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sánchez‐Meca J, Rosa‐Alcázar AI, Marín‐Martínez F et al. Psychological treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: a meta‐analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:37‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Olfson M, Marcus SC. National trends in outpatient psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:1456‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD et al. Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta‐analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:595‐602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barth J, Munder T, Gerger H et al. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: a network meta‐analysis. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Driessen E, Hollon SD, Bockting CLH et al. Does publication bias inflate the apparent efficacy of psychological treatment for major depressive disorder? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of US National Institutes of Health‐funded trials. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cuijpers P, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E et al. Efficacy of cognitive‐behavioural therapy and other psychological treatments for adult depression: meta‐analytic study of publication bias. Br J Psychiatry 2010;196:173‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dickersin K. The existence of publication bias and risk factors for its occurrence. JAMA 1990;263:1385‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Bohlmeijer E et al. The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: a meta‐analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychol Med 2010;40:211‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mohr DC, Spring B, Freedland KE et al. The selection and design of control conditions for randomized controlled trials of psychological interventions. Psychother Psychosom 2009;78:275‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuijpers P, Cristea IA. How to prove that your therapy is effective, even when it is not: a guideline. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2015;28:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Furukawa TA, Noma H, Caldwell DM et al. Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta‐analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014;130:181‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L et al. Psychological treatment of depression: a meta‐analytic database of randomized studies. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cuijpers P, Donker T, Johansson R et al. Self‐guided psychological treatment for depressive symptoms: a meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2011;6:e21274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cuijpers P, Driessen E, Hollon SD et al. The efficacy of non‐directive supportive therapy for adult depression: a meta‐analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2012;32:280‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed Hillsdale: Erlbaum, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta‐analysis. Orlando: Academic Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI‐II, Beck Depression Inventory: manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56:893‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL et al. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther 1990;28:487‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marks IM, Mathews AM. Brief standard self‐rating for phobic patients. Behav Res Ther 1979;17:263‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liebowitz MR. Social phobia In: Klein DF. (ed). Modern trends in pharmacopsychiatry. Berlin: Karger, 1987:141‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Furukawa TA. From effect size into number needed to treat. Lancet 1999;353:1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Weitz E et al. The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: a meta‐analysis. J Affect Disord 2014;159:118‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ioannidis JPA, Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E. Uncertainty in heterogeneity estimates in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2007;335:914‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Orsini N, Bottai M, Higgins J et al. Heterogi: Stata module to quantify heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistical Software Components S449201. Boston: Boston College Department of Economics, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel‐plot‐based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta‐analysis. Biometrics 2000;56:455‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barnhofer T, Crane C, Hargus E et al. Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy as a treatment for chronic depression: a preliminary study. Behav Res Ther 2009;47:366‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berger T, Hämmerli K, Gubser N et al. Internet‐based treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing guided with unguided self‐help. Cogn Behav Ther 2011;40:251‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Burns A, O'Mahen H, Baxter H et al. A pilot randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for antenatal depression. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carrington CH. A comparison of cognitive and analytically oriented brief treatment approaches to depression in black women. College Park: University of Maryland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Casanas R, Catalan R, del Val JL et al. Effectiveness of a psycho‐educational group program for major depression in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Castonguay LG, Schut AJ, Aikens DE et al. Integrative cognitive therapy for depression: a preliminary investigation. J Psychother Integr 2004;14:4‐20. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Choi I, Zou J, Titov N et al. Culturally attuned Internet treatment for depression amongst Chinese Australians: a randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2012;136:459‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cooper PJ, Murray L, Wilson A et al. Controlled trial of the short‐ and long‐term effect of psychological treatment of post‐partum depression. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:412‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cullen JM. Testing the effectiveness of behavioral activation therapy in the treatment of acute unipolar depression Dissertation, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:409‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:658‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Duarte PS, Miyazaki MC, Blay SL et al. Cognitive‐behavioral group therapy is an effective treatment for major depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2009;76:414‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT et al. National Institute of Mental Health treatment of depression collaborative research program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989;46:971‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Vannoy S et al. Telephone and in‐person cognitive behavioral therapy for major depression after traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. J Neurotrauma 2015;32:45‐57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Faramarzi M, Alipor A, Esmaelzadeh S et al. Treatment of depression and anxiety in infertile women: cognitive behavioral therapy versus fluoxetine. J Affect Disord 2008;108:159‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Horrell L, Goldsmith KA, Tylee AT et al. One‐day cognitive‐behavioural therapy self‐confidence workshops for people with depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2014;204:222‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jamison C, Scogin F. The outcome of cognitive bibliotherapy with depressed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:644‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jarrett RB, Schaffer M, McIntire D et al. Treatment of atypical depression with cognitive therapy or phenelzine: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:431‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kanter JW, Santiago‐Rivera AL, Santos MM et al. A randomized hybrid efficacy and effectiveness trial of behavioral activation for Latinos with depression. Behav Ther 2015;46:177‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kivi M, Eriksson MC, Hange D et al. Internet‐based therapy for mild to moderate depression in Swedish primary care: short term results from the PRIM‐NET randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther 2014;43:289‐98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Laidlaw K, Davidson K, Toner H et al. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy vs treatment as usual in the treatment of mild to moderate late life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;23:843‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Larcombe NA, Wilson PH. An evaluation of cognitive‐behaviour therapy for depression in patients with multiple sclerosis. Br J Psychiatry 1984;145:366‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Freedland KE et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:613‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Martin PR, Aiello R, Gilson K et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for comorbid migraine and/or tension‐type headache and major depressive disorder: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2015;73:8‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL et al. Treating depression in predominantly low‐income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:57‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Goodkin DE et al. Comparative outcomes for individual cognitive‐behavior therapy, supportive‐expressive group psychotherapy, and sertraline for the treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001;69:942‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mohr DC, Duffecy J, Ho J et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a manualized TeleCoaching protocol for improving adherence to a web‐based intervention for the treatment of depression. PLoS One 2013;8:e70086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Naeem F, Sarhandi I, Gul M et al. A multicentre randomised controlled trial of a carer supervised culturally adapted CBT (CaCBT) based self‐help for depression in Pakistan. J Affect Disord 2014;156:224‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. O'Mahen H, Himle JA, Fedock G et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for perinatal depression adapted for women with low incomes. Depress Anxiety 2013;30:679‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Omidi A, Mohammadkhani P, Mohammadi A et al. Comparing mindfulness based cognitive therapy and traditional cognitive behavior therapy with treatments as usual on reduction of major depressive disorder symptoms. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2013;15:142‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pecheur DR, Edwards KJ. A comparison of secular and religious versions of cognitive therapy with depressed Christian college students. J Psychol Theol 1984;12:45‐54. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Perini S, Titov N, Andrews G. Clinician‐assisted Internet‐based treatment is effective for depression: randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:571‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Qiu J, Chen W, Gao X et al. A randomized controlled trial of group cognitive behavioral therapy for Chinese breast cancer patients with major depression. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2013;34:60‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy‐based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:902‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rizvi SJ, Zaretsky A, Schaffer A et al. Is immediate adjunctive CBT more beneficial than delayed CBT in treating depression? A pilot study. J Psychiatr Pract 2015;21:107‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rohan KJ, Roecklein KA, Tierney Lindsey K et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive‐behavioral therapy, light therapy, and their combination for seasonal affective disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75:489‐500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ross M, Scott M. An evaluation of the effectiveness of individual and group cognitive therapy in the treatment of depressed patients in an inner city health centre. J R Coll Gen Pr 1985;35:239‐42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Wexler DJ et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT‐AD) in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37:625‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Scott AI, Freeman CP. Edinburgh primary care depression study: treatment outcome, patient satisfaction, and cost after 16 weeks. BMJ 1992;304:883‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Scott C, Tacchi MJ, Jones R et al. Acute and one‐year outcome of a randomised controlled trial of brief cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder in primary care. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:131‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Smit A, Kluiter H, Conradi HJ et al. Short‐term effects of enhanced treatment for depression in primary care: results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 2006;36:15‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Songprakun W, McCann TV. Effectiveness of a self‐help manual on the promotion of resilience in individuals with depression in Thailand: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tandon SD, Leis JA, Mendelson T et al. Six‐month outcomes from a randomized controlled trial to prevent perinatal depression in low‐income home visiting clients. Matern Child Health J 2014;18:873‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Teasdale JD, Fennell MJ, Hibbert GA et al. Cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder in primary care. Br J Psychiatry 1984;144:400‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Titov N, Andrews G, Davies M et al. Internet treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS One 2010;5:e10939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tovote KA, Fleer J, Snippe E et al. Individual mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for treating depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2014;37:2427‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Turner A, Hambridge J, Baker A et al. Randomised controlled trial of group cognitive behaviour therapy versus brief intervention for depression in cardiac patients. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2013;47:235‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Vernmark K, Lenndin J, Bjärehed J et al. Internet administered guided self‐help versus individualized e‐mail therapy: a randomized trial of two versions of CBT for major depression. Behav Res Ther 2010;48:368‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Williams C, Wilson P, Morrison J et al. Guided self‐help cognitive behavioural therapy for depression in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2013;8:e52735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Wollersheim JP, Wilson GL. Group treatment of unipolar depression: a comparison of coping, supportive, bibliotherapy, and delayed treatment groups. Prof Psychol Res Pract 1991;22:496‐502. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wong DFK. Cognitive behavioral treatment groups for people with chronic depression in Hong Kong: a randomized wait‐list control design. Depress Anxiety 2008;25:142‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Wong DFK. Cognitive and health‐related outcomes of group cognitive behavioural treatment for people with depressive symptoms in Hong Kong: randomized wait‐list control study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008;42:702‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Wright JH, Wright AS, Albano AM et al. Computer‐assisted cognitive therapy for depression: maintaining efficacy while reducing therapist time. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1158‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Zu S, Xiang Y‐T, Liu J et al. A comparison of cognitive‐behavioral therapy, antidepressants, their combination and standard treatment for Chinese patients with moderate‐severe major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord 2014;152:262‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Andersson G, Paxling B, Roch‐Norlund P et al. Internet‐based psychodynamic versus cognitive behavioral guided self‐help for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2012;81:344‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Bakhshani NM, Lashkaripour K, Sadjadi SA. Effectiveness of short term cognitive behavior therapy in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Med Sci 2007;7:1076‐81. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Barlow DH, Rapee RM, Brown TA. Behavioral treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther 1992;23:551‐70. [Google Scholar]

- 98. Butler G, Fennell M, Robson P et al. Comparison of behavior therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:167‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Dugas MJ, Brillon P, Savard P et al. A randomized clinical trial of cognitive‐behavioral therapy and applied relaxation for adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther 2010;41:46‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R, Léger E et al. Group cognitive‐behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: treatment outcome and long‐term follow‐up. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71:821‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Hoyer J, Beesdo K, Gloster AT et al. Worry exposure versus applied relaxation in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychother Psychosom 2009;78:106‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ladouceur R, Dugas MJ, Freeston MH et al. Efficacy of a cognitive‐behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: evaluation in a controlled clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:957‐64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Linden M, Zubraegel D, Baer T et al. Efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy in generalized anxiety disorders. Psychother Psychosom 2005;74:36‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Mohlman J, Gorenstein EE, Kleber M et al. Standard and enhanced cognitive‐behavior therapy for late‐life generalized anxiety disorder: two pilot investigations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;11:24‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Paxling B, Almlöv J, Dahlin M et al. Guided internet‐delivered cognitive behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther 2011;40:159‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Power KG, Jerrom DWA, Simpson RJ et al. A controlled comparison of cognitive‐behaviour therapy, diazepam and placebo in the management of generalized anxiety. Behav Psychother 1989;17:1‐14. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Power KG, Simpson RJ, Swanson V et al. A controlled comparison of cognitive‐behaviour therapy, diazepam, and placebo, alone and in combination, for the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord 1990;4:267‐92. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Robinson E, Titov N, Andrews G et al. Internet treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS One 2010;5:e10942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Stanley MA, Hopko DR, Diefenbach GJ et al. Cognitive‐behavior therapy for late‐life generalized anxiety disorder in primary care: preliminary findings. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;11:92‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Stanley MA, Wilson NL, Novy DM et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder among older adults in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2009;301:1460‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Stanley MA, Wilson NL, Amspoker AB et al. Lay providers can deliver effective cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized trial. Depress Anxiety 2014;31:391‐401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Titov N, Andrews G, Robinson E et al. Clinician‐assisted Internet‐based treatment is effective for generalized anxiety disorder: randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:905‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Treanor M, Erisman SM, Salters‐Pedneault K et al. Acceptance‐based behavioral therapy for GAD: effects on outcomes from three theoretical models. Depress Anxiety 2011;28:127‐36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. van der Heiden C, Muris P, van der Molen HT. Randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of metacognitive therapy and intolerance‐of‐uncertainty therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther 2012;50:100‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Wetherell JL, Gatz M, Craske MG. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71:31‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. White J, Keenan M, Brooks N. Stress control: a controlled comparative investigation of large group therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Psychother 1992; 20:97‐113. 21614450 [Google Scholar]

- 117. Zinbarg RE, Lee JE, Yoon KL. Dyadic predictors of outcome in a cognitive‐behavioral program for patients with generalized anxiety disorder in committed relationships: a ‘spoonful of sugar’ and a dose of non‐hostile criticism may help. Behav Res Ther 2007;45:699‐713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Addis ME, Hatgis C, Krasnow AD et al. Effectiveness of cognitive‐behavioral treatment for panic disorder versus treatment as usual in a managed care setting. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:625‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Bakker A, van Dyck R, van Balkom AJ. Paroxetine, clomipramine, and cognitive therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:831‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Barlow DH, Craske MG, Cerny JA et al. Behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Ther 1989;20:261‐82. [Google Scholar]

- 121. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK et al. Cognitive‐behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000;283:2529‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Black DW, Wesner R, Bowers W et al. A comparison of fluvoxamine, cognitive therapy, and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:44‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Botella C, García‐Palacios A, Villa H et al. Virtual reality exposure in the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia: a controlled study. Clin Psychol Psychother 2007;14:164‐75. [Google Scholar]

- 124. Carlbring P, Westling BE, Ljungstrand P et al. Treatment of panic disorder via the Internet: a randomized trial of a self‐help program. Behav Ther 2001;32:751‐64. [Google Scholar]

- 125. Carlbring P, Bohman S, Brunt S et al. Remote treatment of panic disorder: a randomized trial of internet‐based cognitive behavior therapy supplemented with telephone calls. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:2119‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Carter MM, Sbrocco T, Gore KL et al. Cognitive‐behavioral group therapy versus a wait‐list control in the treatment of African American women with panic disorder. Cogn Ther Res 2003;27:505‐18. [Google Scholar]

- 127. Casey LM, Newcombe PA, Oei TP. Cognitive mediation of panic severity: the role of catastrophic misinterpretation of bodily sensations and panic self‐efficacy. Cogn Ther Res 2005;29:187‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A et al. A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:759‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackmann A et al. Brief cognitive therapy for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999;67:583‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Gould RA, Clum GA, Shapiro D. The use of bibliotherapy in the treatment of panic: a preliminary investigation. Behav Ther 1993;24:241‐52. [Google Scholar]

- 131. Gould RA, Clum GA. Self‐help plus minimal therapist contact in the treatment of panic disorder: a replication and extension. Behav Ther 1995;26:533‐46. [Google Scholar]

- 132. Hazen AL, Walker JR, Eldridge GD. Anxiety sensitivity and treatment outcome in panic disorder. Anxiety 1996;2:34‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Hendriks G‐J, Keijsers GPJ, Kampman M et al. A randomized controlled study of paroxetine and cognitive‐behavioural therapy for late‐life panic disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;122:11‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Ito LM, De Araujo LA, Tess VLC et al. Self‐exposure therapy for panic disorder with agoraphobia: randomised controlled study of external v. interoceptive self‐exposure. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:331‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Klein B, Richards JC. A brief Internet‐based treatment for panic disorder. Behav Cogn Psychother 2001;29:113‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Klosko JS, Barlow DH, Tassinari R et al. A comparison of alprazolam and behavior therapy in treatment of panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990;58:77‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Lessard M‐J, Marchand A, Pelland M‐È et al. Comparing two brief psychological interventions to usual care in panic disorder patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain. Behav Cogn Psychother 2012;40:129‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Lidren DM, Watkins PL, Gould RA et al. A comparison of bibliotherapy and group therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994;62:865‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Ross CJ, Davis TM, Macdonald GF. Cognitive‐behavioral treatment combined with asthma education for adults with asthma and coexisting panic disorder. Clin Nurs Res 2005;14:131‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Schmidt NB, Trakowski JH, Staab JP. Extinction of panicogenic effects of a 35% CO2 challenge in patients with panic disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 1997;106:630‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Schmidt NB, McCreary BT, Trakowski JJ et al. Effects of cognitive behavioral treatment on physical health status in patients with panic disorder. Behav Ther 2003;34:49‐63. [Google Scholar]

- 142. Sharp DM, Power KG, Simpson RJ et al. Fluvoxamine, placebo, and cognitive behaviour therapy used alone and in combination in the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord 1996;10:219‐42. [Google Scholar]

- 143. Sharp DM, Power KG, Swanson V. A comparison of the efficacy and acceptability of group versus individual cognitive behaviour therapy in the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia in primary care. Clin Psychol Psychother 2004;11:73‐82. [Google Scholar]

- 144. Swinson RP, Fergus KD, Cox BJ et al. Efficacy of telephone‐administered behavioral therapy for panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:465‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Telch MJ, Lucas JA, Schmidt NB et al. Group cognitive‐behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1993;31:279‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Williams SL, Falbo J. Cognitive and performance‐based treatments for panic attacks in people with varying degrees of agoraphobic disability. Behav Res Ther 1996;34:253‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Wims E, Titov N, Andrews G et al. Clinician‐assisted Internet‐based treatment is effective for panic: a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:599‐607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Abramowitz JS, Moore EL, Braddock AE et al. Self‐help cognitive‐behavioral therapy with minimal therapist contact for social phobia: a controlled trial. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2009;40:98‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Andersson G, Carlbring P, Holmström A et al. Internet‐based self‐help with therapist feedback and in vivo group exposure for social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:677‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Beidel DC, Alfano CA, Kofler MJ et al. The impact of social skills training for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord 2014;28:908‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Berger T, Hohl E, Caspar F. Internet‐based treatment for social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol 2009;65:1021‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Blanco C, Heimberg RG, Schneier FR et al. A placebo‐controlled trial of phenelzine, cognitive behavioral group therapy, and their combination for social anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:286‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Botella C, Gallego MJ, Garcia‐Palacios A et al. An Internet‐based self‐help treatment for fear of public speaking: a controlled trial. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2010;13:407‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Carlbring P, Gunnarsdóttir M, Hedensjö L et al. Treatment of social phobia: randomised trial of internet‐delivered cognitive‐behavioural therapy with telephone support. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:123‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Clark DM, Ehlers A, Hackmann A et al. Cognitive therapy versus exposure and applied relaxation in social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:568‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Craske MG, Niles AN, Burklund LJ et al. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for social phobia: outcomes and moderators. J Consult Clin Psychol 2014;82:1034‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Davidson JR, Foa EB, Huppert JD et al. Fluoxetine, comprehensive cognitive behavioral therapy, and placebo in generalized social phobia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:1005‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Furmark T, Carlbring P, Hedman E et al. Guided and unguided self‐help for social anxiety disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195:440‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Goldin PR, Ziv M, Jazaieri H et al. Cognitive reappraisal self‐efficacy mediates the effects of individual cognitive‐behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:1034‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Gruber K, Moran PJ, Roth WT et al. Computer‐assisted cognitive behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behav Ther 2001;32:155‐65. [Google Scholar]

- 161. Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA et al. Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12‐week outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:1133‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Himle JA, Bybee D, Steinberger E et al. Work‐related CBT versus vocational services as usual for unemployed persons with social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Behav Res Ther 2014;63:169‐76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Hofmann SG. Cognitive mediation of treatment change in social phobia. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:392‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Bruch MA. Dismantling cognitive‐behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:637‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Kocovski NL, Fleming JE, Hawley LL et al. Mindfulness and acceptance‐based group therapy versus traditional cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2013;51:889‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Ledley DR, Heimberg RG, Hope DA et al. Efficacy of a manualized and workbook‐driven individual treatment for social anxiety disorder. Behav Ther 2009;40:414‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Leichsenring F, Salzer S, Beutel ME et al. Psychodynamic therapy and cognitive‐behavioral therapy in social anxiety disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Mattick RP, Peters L, Clarke JC. Exposure and cognitive restructuring for social phobia: a controlled study. Behav Ther 1989;20:3‐23. [Google Scholar]

- 169. Mörtberg E, Clark DM, Sundin Ö et al. Intensive group cognitive treatment and individual cognitive therapy vs. treatment as usual in social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007;115:142‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Mulkens S, Bögels SM, de Jong PJ et al. Fear of blushing: effects of task concentration training versus exposure in vivo on fear and physiology. J Anxiety Disord 2001;15:413‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Newman MG, Hofmann SG, Trabert W et al. Does behavioral treatment of social phobia lead to cognitive changes? Behav Ther 1994;25:503‐17. [Google Scholar]

- 172. Oosterbaan DB, van Balkom AJ, Spinhoven P et al. Cognitive therapy versus moclobemide in social phobia: a controlled study. Clin Psychol Psychother 2001;8:263‐73. [Google Scholar]

- 173. Pishyar R, Harris LM, Menzies RG. Responsiveness of measures of attentional bias to clinical change in social phobia. Cogn Emot 2008;22:1209‐27. [Google Scholar]

- 174. Price M, Anderson PL. The impact of cognitive behavioral therapy on post event processing among those with social anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther 2011;49:132‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Rapee RM, Abbott MJ, Baillie AJ et al. Treatment of social phobia through pure self‐help and therapist‐augmented self‐help. Br J Psychiatry 2007;191:246‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Robillard G, Bouchard S, Dumoulin S et al. Using virtual humans to alleviate social anxiety: preliminary report from a comparative outcome study. Stud Health Technol Inf 2010;154:57‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177. Salaberria K, Echeburua E. Long‐term outcome of cognitive therapy's contribution to self‐exposure in vivo to the treatment of generalized social phobia. Behav Modif 1998;22:262‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. Stangier U, Heidenreich T, Peitz M et al. Cognitive therapy for social phobia: individual versus group treatment. Behav Res Ther 2003;41:991‐1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179. Stangier U, Schramm E, Heidenreich T et al. Cognitive therapy vs interpersonal psychotherapy in social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:692‐700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180. Titov N, Andrews G, Schwencke G et al. Shyness 1: distance treatment of social phobia over the Internet. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008;42:585‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181. Titov N, Andrews G, Schwencke G. Shyness 2: treating social phobia online: replication and extension. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008;42:595‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182. Titov N, Andrews G, Choi I et al. Shyness 3: randomized controlled trial of guided versus unguided Internet‐based CBT for social phobia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008;42:1030‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183. Turner SM, Beidel DC, Jacob RG. Social phobia: a comparison of behavior therapy and atenolol. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994;62:350‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184. Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G et al. A meta‐analysis of cognitive‐behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can J Psychiatry 2013;58:376‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185. Cuijpers P, Cristea IA. What if a placebo effect explained all the activity of depression treatments? World Psychiatry 2015;14:310‐1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]