Abstract

In general, patients with diabetes performing self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) can strongly rely on the accuracy of measurement results. However, various factors such as application errors, extreme environmental conditions, extreme hematocrit values, or medication interferences may potentially falsify blood glucose readings. Incorrect blood glucose readings may lead to treatment errors, for example, incorrect insulin dosing. Therefore, the diabetes team as well as the patients should be well informed about limitations in blood glucose testing. The aim of this publication is to review the current knowledge on limitations and interferences in blood glucose testing with the perspective of their clinical relevance.

Keywords: blood glucose testing, diabetes, interference, reliability, self-monitoring of blood glucose, SMBG

Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) both in insulin-treated and non-insulin-treated people with diabetes is supported by recently published trials, reviews, meta-analyses, and guidelines.1-7 SMBG is recommended to be performed in a structured approach.2,5,8,9 It is reported to be only useful when blood glucose (BG) data are interpreted and utilized for immediate therapeutic actions.3,4,10-13 For instance, the need for adequate dosing of insulin heavily depends on reliable glucose information.8 In particular, patients with insulin-treated diabetes perform SMBG as a substantial element of daily management of diabetes.14,15 The term “BG system” denotes the combination of a BG meter and test strips, and both determine analytical performance.8 The analytical and handling performance of BG systems has largely improved over the past decades. In addition, the implementation of in-meter safety features (ie, validity of test strips check) has further increased the safety of these devices.16 Consequently, patients with appropriate training and a good performance of BG testing can typically rely on the precision of BG measurement results. However, in the daily practice a range of factors with potential impact on the reliability of BG measurement needs to be considered. In fact, this is an important aspect in field of point-of-care (POC) testing.17 Members of the diabetes team and patients should be well informed about all factors potentially falsifying BG measurement results: human, meter-inherent, test-strip-inherent, environmental, physiological, and medication-related impact factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors With a Potential Impact on the Analytical Performance of SMBG.

| Human | Incorrect use of BG meters |

| Incorrect performance of coding | |

| Inappropriate storage and usage of test strips | |

| Inappropriate education of patients and diabetes team | |

| Meter-inherent | Accuracy |

| User-friendliness | |

| Test-strip-inherent | Lot-to-lot variances |

| Vial-to-vial variances | |

| Strip-to-strip variances | |

| Environmental | Temperature |

| Humidity | |

| Altitude | |

| Electromagnetic radiation | |

| Physiological | Peripheral blood perfusion |

| Hematocrit | |

| Partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) | |

| Triglycerides | |

| Bilirubin | |

| Uric acid | |

| Medicational | Ascorbic acid (intravenously) |

| Acetaminophen (paracetamol) | |

| Dopamine | |

| Mannitol | |

| Icodextrin |

The risk of misinterpretation of BG readings can be minimized by detailed information on the factors potentially affecting BG measurement. Hence, the aim of this publication is to review the current knowledge on limitations and interferences significant for reliable BG testing.

Nonetheless, due to the rapid technological progress, it should be kept in mind that performance of most more recent BG meters may not always be reflected by the reviewed literature, since it reports on data generated with older BG generations.17 Moreover, it is important to note that some studies on limitations of BG meters were performed under extreme conditions which do not comply with the approved conditions of usage.

Preanalytical Factors

Inappropriate handling of SMBG has been identified as the most common factor affecting BG results; more than 90% of overall inaccuracies result from incorrect use of BG meters.4,18 Due to the minute blood samples utilized by modern BG systems, even minor contamination with glucose containing fluids may substantially increase the measurement. Sugar-containing products, such as fruits, can leave considerable amounts of glucose on the skin, thereby causing falsely high SMBG results.17,19,20 In daily practice, a substantial number of patients do not wash their hands before performing BG measurements.

The coding procedure is another potential source of error. Coding is needed to transfer information from the test strip calibration to the BG meter. Incorrect coding may lead to measurement errors of ±30% or more.21 However, most modern BG systems no longer require a coding step.22

Furthermore, BG measurement may be compromised by usage of deteriorated test strips, which may result from inappropriate storage, mechanical stress, or usage after the expiry date.18,23,24 BG test strips were found to perform more reliably when stored in closed vials than in open vials, which is of special importance when used under extreme environmentalconditions.17 The impact of inappropriate storage of test strips on BG readings is demonstrated by the case of a 72-year-old Japanese patient with type 2 diabetes. To simplify the SMBG procedure, he removed the test strips from the packaging and stored them, together with the BG meter, in a small pouch. Due to repeated pseudohypoglycemic readings, the patient abandoned his antihyperglycemic medication, thereby reaching a BG level of 21.8 mmol/L (393 mg/dL).24

This case report also exemplifies the importance of patient education. Inappropriate patient education has been identified as a leading cause of inadequate SMBG performance. One study found that 69% of the patients who had initially failed in their SMBG performance achieved acceptable SMBG results after reeducation.25

Meter-Inherent Factors

Simulations suggest an increasing likelihood of treatment errors in response to decreasing accuracy of BG systems.26 Even when used by trained laboratory professionals, every BG meter entails a certain degree of imprecision and bias associated with it.4 Other inherent system limitations such as ease of handling, and readability of the numbers shown on the display need to be considered.4,22 Moreover, data transfer from the internal meter memory into a computer may be a time-consuming and cumbersome procedure.4

The usability of BG meters plays a key role in warranting reliable and accurate measurement results.22 Helpful features, for example, are safeguards that indicate test strip expiration, underdosing of blood sample, exposure to abnormal temperature, and so on.17

Beyond these potential technological barriers, there is the human error factor, for example, incomplete test strip insertion into the meter, or application despite of low-battery status.27

Hence, even if a given BG meter with a given lot of test strips fulfils the accuracy requirements of the regulatory authorities, this does not necessarily imply that all devices and lots will do so after market introduction, particularly under real-life conditions.17

To ensure high quality under real-life conditions, and in response to ISO (International Organization for Standardization) 15197:2013 requirements,28 apart from extensive testing, a user performance evaluation is required to show whether patients are able to obtain accurate measurement results with a given system. For this purpose, measurements should be performed by the end users simply following the instructions of use, without any training or assistance.

Test-Strip-Inherent Factors

Manufacturing of test strips is a complex process involving various factors, so it is unreasonable to assume that all test strips—even within a certain brand—will produce (almost) identical measurement results. Requirements for BG systems—including accuracy—are described in detail in the internationally accepted standard EN ISO 15197.29 According to the currently applicable version ISO 15197:2013,28 95% of BG results must fall within ±15 mg/dL of the reference method at BG concentrations <100 mg/dL and within ±15% at BG concentrations ≥100 mg/dL. In addition, 99% of all values must fall into zones A and B of the Parkes error grid for type 1 diabetes. Three different lots need to be tested and all 3 must pass. The previous version, ISO 15197:2003,30 which had less rigorous requirements, may still be referred to for a transitional period.

A potential concern involving test strips is the variance between test strip lots (lot-to-lot variation).31 In a study, 4 test strip lots for each of 5 different BG systems were evaluated, including measurement results ranging from <50 mg/dL to >400 mg/dL. The maximum lot-to-lot difference between any 2 of the 4 evaluated test strip lots per BG system found ranged between 1.0% and 13.0%.31 Only 1 of the 5 systems achieved at least 95% of the measurements within the accuracy limits of ISO 15197:2003 with each test strip lot.

A more recent study, however, demonstrated that 7 of 9 systems fulfill the accuracy criteria of ISO 15197:2013,28 independent of the comparison measurement method applied. These systems showed, with all 3 tested lots, 95%-100% of results within ±0.83 mmol/L (±15 mg/dL) and ±15% of the comparison measurement results at BG concentrations of <5.55 mmol/L (<100 mg/dL) and ≥5.55 mmol/L (≥100 mg/dL).32

Due to a mandate from the European and US regulatory authorities, in the future 3 different test strip lots will have to be included in the accuracy evaluation of BG systems,32 as required by ISO 15197:2013.28

Small strip-to-strip variation and vial-to vial variation may occur due to the manufacturing process. For instance, small variations in the reaction well size and/or loss of enzyme coverage may influence the accuracy of BG systems as well as reduction of the mediator.23

The activity of the 2 enzymes employed for BG measurement, glucose oxidase (GO) and glucose dehydrogenase (GD) was reported to be potentially susceptible of interference by other substances. GD, however, seems less susceptible.33

Environmental Factors

Temperature and Humidity

Like every biochemical process, the test strip reaction during glucose measurement is influenced by temperature.34 Therefore, BG measurements with currently available test strips is temperature-dependent. BG performance under conditions that do not comply with the approved usage may result in erroneous BG measurements. For this reason, patients should be instructed to use BG systems within the specified operating temperature range only.22 Nowadays, many modern BG systems have a built-in temperature sensor that utilizes the measured temperature to correct the glucose measurement result. However, usually the temperature is measured inside the meter housing and not at the site of the glucose reaction on the test strip. The temperatures between the meter itself and the tests strip can be quite different. A study on 9 SMBG systems available in Norway explored the impact of temperature changes on the accuracy of BG measurements.35 A change from 5°C to room temperature immediately before measurement, produced upward discrepancies >5% in 4 of these SMBG systems. Conversely, after a rapid change from 30°C to room temperature, 4 of the 9 BG systems presented downward discrepancies >5%.35 A period of acclimatization (up to 15-30 minutes) seemed to lessen these effects. A recently published study on 5 modern BG systems showed that compensating mechanisms within the system allowed a good performance at extreme high and low temperatures. Rapid extreme changes in temperature, however, may be associated with a time lag of limited function from 15 to 30 minutes.36

Erroneous BG results may also result from inadequate correction parameters of the meter-internal temperature sensor due to differences in acclimatization time between meter and test strip.22 Still, to a large degree, studies performed under extreme conditions do not comply with the approved conditions of usage and, therefore, poor performance at these off-label conditions cannot be ascribed to the BG meters under review.

In addition, a study on POC testing devices with simulated field conditions revealed the impact of extreme temperatures on test strips performance.37 After cold-stressing (−21°C) and heat-stressing (40°C) for up to 4 weeks, glucose test strips showed an impaired performance, with falsely elevated results after heating and falsely decreased results after cooling.37 A study employing an environmental chamber was conducted to assess the impact of short-term exposure (15-60 minutes) to high temperature and humidity on POC glucose test strips (in original vial packaging) and BG meters performance.38 Even after a relatively short exposure (15 minutes) at 42ºC with 83% relative humidity, the tested BG systems produced significantly elevated BG results.38 Measurement discrepancies of 20 mg/dL (BG meter) and 13 mg/dL (test strip) have been reported, the summed increase of 33 mg/dL can be assumed to potentially lead to inadequate treatment decisions.38 Importantly, as in the previous study, the conditions used in these studies were not in accordance with the approved conditions for usage.

Another study explored the impact of midterm stress at high temperature and humidity by using an environmental chamber for 50 days.39 Eight BG meters and their associated test strips were tested for reliability using the appropriate glucose control solution. Test strip vials were opened every day to simulate real-life usage by patients. Glucose values were recorded at temperatures of 54-87°F (12-31°C) and humidity values ranging from 49% to 100%, resembling the environmental conditions experienced by patients performing SMBG.39 High temperature and humidity, but mostly temperature were found to affect the reliability of many BG meters. For instance, in 1 BG meter an increase in temperature of 33°F (18°C) resulted in a 37 mg/dL overestimation of BG. As stated above, such deviations can lead to significant errors in diabetes management.39 Erroneous BG measurements may particularly occur if BG meters are used under conditions which do not comply with the approved usage.

Altitude

Typical high altitude conditions include a decrease in partial pressure of oxygen (pO2), ambient temperature, and relative humidity. Various BG systems have been studied at high altitudes (>2000 m) under field as well as under controlled conditions.22 The analytical performance of most tested BG systems was found to be compromised by higher altitudes, however, usually only at much higher than 2000 m elevations.40-44 Both, under- and overestimated BG values have been observed, being a relatively lowered pO2 the main reason for these measurement deviations.22 Under decreasing pO2 clinically relevant deviations with a risk of treatment errors have been demonstrated with some meters,41,45 an effect normally related to increased BG readings. In a study conducted in Tanzania, 3 BG meters taken to Mt Kilimanjaro (>5800 m) showed BG readings of 50, 214, and 367 mg/dL on the same sample.40 Comparable results have been obtained in another study using a hypobaric chamber.41,45

Electromagnetic Radiation Emitted From Mobile Phones

Mobile phones emit electromagnetic radiation in the microwave range. A study was performed to evaluate potential effects of such waves on the performance of BG systems.46 In 1 group of participants, blood samples within the normoglycemic range were analyzed in the absence and presence of a ringing mobile phone (located directly next to the BG system). A mean difference of 7.5 ± 4.8 mg/dL between the 2 measurements was calculated. In the control group, the mean difference between the 2 repeated measurements per participant in the absence of electromagnetic fields was 1.1 ± 0.9 mg/dL. In conclusion, electromagnetic interference from mobile phones has been reported to potentially impact the accuracy of home BG meters. Therefore, the authors recommend the use of mobile phones at least 50 cm away from home BG meters.46

Physiological Factors

A range of physiological factors, such as peripheral blood perfusion, hematocrit, pO2, triglycerides, bilirubin, and uric acid, has been observed to potentially impact the performance of BG systems.18,33,47-50

A reduction in peripheral blood perfusion due to hypotension may affect a BG system’s performance. In 2007 a review showed that glucose-1-dehydrogenase based POC devices as well as GO-based BG meters may produce incorrect results under such conditions.33 Particularly in critically ill patients, an incorrect diagnosis of hypoglycemia due to poor peripheral perfusion (eg, circulatory shock) may be harmful.34 Peripheral hypoperfusion may result in an increased tissue glucose extraction and a lower glucose value in capillary in comparison to venous blood. Therefore, it is necessary to check whether a particular BG meter has been labeled by the manufacturer for use with critically ill patients.

Accuracy of SMBG measurement may also be affected by high or low hematocrit values.18,23,33,34,51 Hematocrit levels outside the reference interval are reported to be more prevalent than expected, even in Western countries.49,52 In general, low hematocrit values (< 35%) frequently result in too high readings, while an increase in hematocrit is associated with a decrease in BG readings.33,53 A study on 19 SMBG systems found that only a few meters were unaffected by hematocrit interference.49 Nevertheless, modern BG systems correcting automatically for hematocrit are considered to be less susceptible to high or low hematocrit.33

Triglycerides take up volume, thereby decreasing the amount of glucose in the capillary volume. As a consequence, high levels of triglycerides may result in falsely low BG readings.23

In BG systems utilizing GO-based test strips, the potential interference of pO2 has been reported.18,22,23,54,55 Oxygen acts as a competitor to the mediator by taking electrons from the enzyme. Therefore, high oxygen values (eg, in patients utilizing oxygen) may deliver falsely low BG readings. On the other hand, low oxygen levels (eg, in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) might help deliver falsely high BG values.23,56 On the other hand, a study using GD test strips showed them not to be significantly affected by different oxygen pressure.54 With a GO-based measurement, however, an increase in pO2 to >100 Torr (eg, in critically ill patients receiving oxygen treatment) may result in a remarkable underestimation of BG values.22,54 An evaluation of 5 SMBG systems utilizing a GO enzyme reaction on test strips showed BG measurements to be affected by pO2 values < 45 and ≥ 150 mmHg in the blood sample.56

The practical relevance of these correlations is highlighted by an investigation of capillary blood samples obtained from the fingertips of 110 patients (31 with type 1 diabetes mellitus, 69 with type 2 diabetes, 10 without diabetes, no acute serious diseases). A broad range of capillary pO2 values was demonstrated to occur in daily clinical practice.57

Uric acid is a DNA degradation product, and as such, very high uric acid concentrations, exceeding 20 mg/dL, can be observed in patients under chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or cancers with rapid cell turnover, such as certain lymphomas.58

At very high levels, uric acid may be oxidized by the electrode, thereby potentially delivering falsely high BG results.23 This might entail a considerable clinical significance for patients suffering from severe gout. An extreme example is the clinical case of a 54-year-old woman with diabetes and chronic kidney disease who presented a distinct hypoglycemic encephalopathy despite of BG readings > 160 mg/dL.59 High uric acid and low hematocrit values have been suggested to cause falsely high BG readings, thereby resulting in inappropriate therapeutic decisions.59

Medication-Related Factors

A number of different substances have been reported to interfere with BG measurement.17,51 A study on 30 substances—including,among others, acetaminophen (paracetamol), acetylsalicylic acid, various antibiotics, heparin, and warfarin—found glucose measurements of 6 handheld BG meters to be potentially affected by ascorbic acid, acetaminophen, dopamine, maltose, and mannitol.50 Depending on the BG system and substance, deviations both, up and down, could be demonstrated.

Acetaminophen is used by about 200 million people worldwide; many acetaminophen-containing drugs are accessible without prescription.17 Elevated acetaminophen plasma levels may affect BG measurements, causing inaccurately high BG results in certain electrochemical systems. Due to varying individual drug metabolization rates, no concrete acetaminophen threshold level for impact on BG results can be defined.17

Furthermore, presence of the glucose polymer icodextrin has been observed to potentially impact BG meter performance.60 Icodextrin is employed to improve ultrafiltration in peritoneal dialysis. During peritoneal dialysis, 20%-30% of icodextrin is absorbed into the systemic circulation and metabolized to oligosaccharides such as maltose.60 Both GO- and GD-based measurement technologies, are reported to be susceptible to interference with icodextrin metabolites, leading to overestimations of BG.60 Conversely, falsely low BG readings may result in presence of high bilirubin levels or in monoclonal gammopathies.33

Practical Consequences

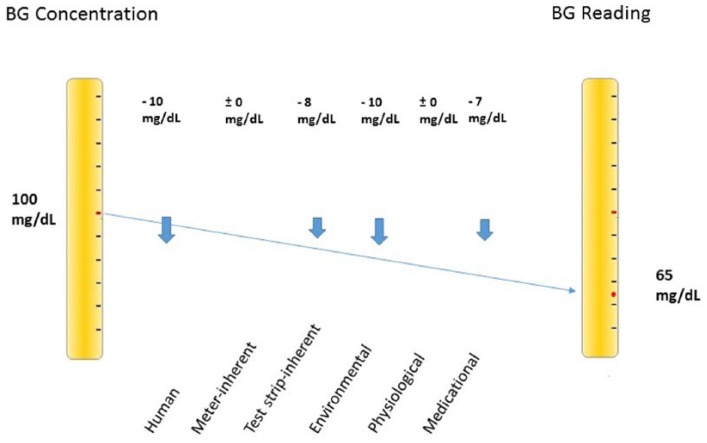

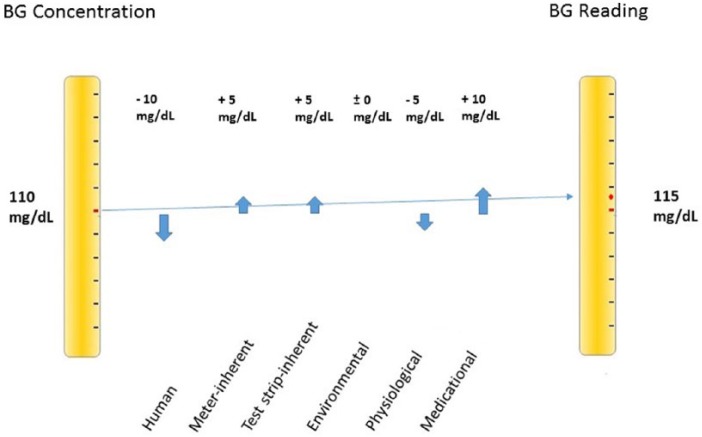

Modern BG systems complying with ISO 15197:2013 accuracy criteria28 operate reliably under controlled conditions.32 Nevertheless, a variety of potential error sources must be taken into account under daily life conditions. Erroneous BG readings may result in contraindicated treatment decisions.61,62 Small measurement errors might not impact insulin dosing. However, if they are large, clinically relevant insulin doses might be administered.61 Even relatively small measurement errors may add up to a substancial total deviation (Figure 1). Yet, it is possible that erroneous readings balance each other out (Figure 2). This implies that possible error sources should be eliminated as comprehensively as possible.

Figure 1.

Relatively small divergences may sum up to a substancial total deviation of −35 mg/dL.

Figure 2.

Deviations may also balance themselves, resulting in a total deviation of only +5 mg/dL.

Error sources which can directly be influenced by the user are, for example, utilization of expired test strips, contamination of the test finger with glucose containing fluids, inappropriate hand washing, insufficient blood sample or, in general, failure to comply with operating instructions. Meter-inherent factors normally are beyond user’s control. These considerations should be kept in mind with respect of selection of BG meters as well as user education.

Selection of BG Meters

BG systems adherent to established standards, such as ISO 15197:2013,28 have a greater probability of providing reliable BG values.32 ISO 15197:2013 requirements include the evaluation of influential values, such as hematocrit. Moreover, the use of BG systems which do not need calibration by the user (“no-coding” BG systems) may contribute to a reduction in handling errors.28

User-friendly BG systems, providing high accuracy and low susceptibility to potential disturbance factors, should be preferred. In addition, there is a need for complete, comprehensible, and clear information in the labeling, for example, about an oxygen dependency, operational limits or storage under extreme conditions, such as high and low temperature and humidity.22,37 It is pertinent to note, however, that many patients (and members of the diabetes team) do not carefully read the instructions for appropriate use.

Adequate Education of Patients and Diabetes Team

To provide reliable BG results, even BG systems with high analytical performance require correct handling and appropriate measurement conditions. Inadequate education has been identified as a leading cause of bad SMBG performance.25 Thus, patients need appropriate education in the correct performance of SMBG as well as for handling and storage of test strips. Education must also include careful interpretation of BG readings, since blind trust in exceptional results may produce wrong and even dangerous treatment decisions.

Incidentally, adequate information on physiological and medication factors with a potential impact on BG readings needs to be provided. In addition, at least during preparation time before a stay under extreme environmental conditions, adequate information on potential physical disturbing factors. For example, patients with diabetes planning activities at high altitude should check whether their BG system is proven not to be affected by high altitude. At the very least, a careful interpretation of BG readings at high altitude is recommended.17

People with diabetes should also be aware of the possible influence of extreme temperature variations. Especially when using BG systems without a specific technology for preventing temperature impact, patients are recommended to perform SMBG not earlier than 15-20 minutes after a substantial shift in temperature.22

Conclusion

Adequate handling and storage of BG systems inclusive of test strips, as well as proper performance of the quantifying process are mandatory prerequisites for reliable SMBG results. In addition, erroneous BG measurement can be a result of physiological, environmental, and medication factors. To avoid clinical risks in response to such incorrect results, appropriate patient education and diabetes management team training are mandatory.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BG, blood glucose; GD, glucose dehydrogenase; GO, glucose oxidase; ISO, International Organization for Standardization; POC, point-of-care; pO2, partial pressure of oxygen; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: RH is an employee of Roche Diabetes Care GmbH, Mannheim, Germany. GF, BK, RZ, LH, and OS are members of national and international advisory boards of Roche Diabetes Care GmbH, Mannheim, Germany

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The generation of the manuscript was supported by an unrestricted grant of Roche Diabetes Care GmbH, Mannheim, Germany

References

- 1. Duran A, Martin P, Runkle I, et al. Benefits of self-monitoring blood glucose in the management of new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus: the St Carlos Study, a prospective randomized clinic-based interventional study with parallel groups. J Diabetes. 2010;2:203-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schnell O, Alawi H, Battelino T, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes: recent studies. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:478-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Schikman CH, et al. Structured self-monitoring of blood glucose significantly reduces A1C levels in poorly controlled, noninsulin-treated type 2 diabetes: results from the Structured Testing Program study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:262-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klonoff DC, Blonde L, Cembrowski G, et al. Consensus report: the current role of self-monitoring of blood glucose in non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5:1529-1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016;39(suppl 1):S1-S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ryden L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: the Task Force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3035-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. International Diabetes Federation. Global guideline for type 2 diabetes. 2012. Available at: http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/IDF-Guideline-for-Type-2-Diabetes.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2015.

- 8. Schnell O, Hinzmann R, Kulzer B, et al. Assessing the analytical performance of systems for self-monitoring of blood glucose: concepts of performance evaluation and definition of metrological key terms. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:1585-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. IDF. Guideline for management of postmeal glucose in diabetes. 2011. Available at: http://www.idf.org. Accessed April 29, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Bosi E, Scavini M, Ceriello A, et al. Intensive structured self-monitoring of blood glucose and glycemic control in noninsulin-treated type 2 diabetes: the PRISMA randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2887-2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schnell O, Alawi H, Battelino T, et al. The role of self-monitoring of blood glucose in glucagon-like peptide-1-based treatment approaches: a European expert recommendation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:665-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franciosi M, Lucisano G, Pellegrini F, et al. ROSES: role of self-monitoring of blood glucose and intensive education in patients with type 2 diabetes not receiving insulin. A pilot randomized clinical trial. Diabet Med. 2011;28:789-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kempf K, Kruse J, Martin S. ROSSO-in-praxi: a self-monitoring of blood glucose-structured 12-week lifestyle intervention significantly improves glucometabolic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:547-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blevins T. Value and utility of self-monitoring of blood glucose in non-insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Postgrad Med. 2013;125:191-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bergenstal RM, Ahmann AJ, Bailey T, et al. Recommendations for standardizing glucose reporting and analysis to optimize clinical decision making in diabetes: the ambulatory glucose profile. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:562-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heinemann L. Control solutions for blood glucose meters: a neglected opportunity for reliable measurements? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;9:723-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heinemann L. Quality of glucose measurement with blood glucose meters at the point-of-care: relevance of interfering factors. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:847-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tonyushkina K, Nichols JH. Glucose meters: a review of technical challenges to obtaining accurate results. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:971-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hortensius J, Slingerland RJ, Kleefstra N, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose: the use of the first or the second drop of blood. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:556-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirose T, Mita T, Fujitani Y, Kawamori R, Watada H. Glucose monitoring after fruit peeling: pseudohyperglycemia when neglecting hand washing before fingertip blood sampling: wash your hands with tap water before you check blood glucose level. Diabetes Care. 2012;34:596-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baum JM, Monhaut NM, Parker DR, Price CP. Improving the quality of self-monitoring blood glucose measurement: a study in reducing calibration errors. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2006;8:347-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmid C, Haug C, Heinemann L, Freckmann G. System accuracy of blood glucose monitoring systems: impact of use by patients and ambient conditions. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15:889-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ginsberg BH. Factors affecting blood glucose monitoring: sources of errors in measurement. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:903-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tamaki M, Kanazawa A, Shirakami A, et al. A case of false hypoglycemia by SMBG due to improper storage of glucometer test strips. Diabetol Int. 2014;5:199-201. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bergenstal R, Pearson J, Cembrowski GS, Bina D, Davidson J, List S. Identifying variables associated with inaccurate self-monitoring of blood glucose: proposed guidelines to improve accuracy. Diabetes Educ. 2000;26:981-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Breton MD, Kovatchev BP. Impact of blood glucose self-monitoring errors on glucose variability, risk for hypoglycemia, and average glucose control in type 1 diabetes: an in silico study. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4:562-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Downie P. Practical aspects of capillary blood glucose monitoring: a simple guide for primary care. Diabetes Primary Care. 2013;15:149-153. [Google Scholar]

- 28. International Organization for Standardization. In vitro diagnostic test systems—requirements for blood-glucose monitoring systems for self-testing in managing diabetes mellitus. EN ISO/DIS 15197:2013. Available at: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=54976. Accessed July 17, 2015.

- 29. Freckmann G, Schmid C, Baumstark A, Rutschmann M, Haug C, Heinemann L. Analytical performance requirements for systems for self-monitoring of blood glucose with focus on system accuracy: relevant differences among ISO 15197:2003, ISO 15197:2013, and current FDA recommendations. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;9:885-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. International Organization for Standardization. In vitro diagnostic medical devices—measurement of quantities in biological samples—metrological traceability of values assigned to calibrators and control materials. ISO 17511:2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baumstark A, Pleus S, Schmid C, Link M, Haug C, Freckmann G. Lot-to-lot variability of test strips and accuracy assessment of systems for self-monitoring of blood glucose according to ISO 15197. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:1076-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Freckmann G, Link M, Schmid C, Pleus S, Baumstark A, Haug C. System accuracy evaluation of different blood glucose monitoring systems following ISO 15197:2013 by using two different comparison methods. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17:635-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dungan K, Chapman J, Braithwaite SS, Buse J. Glucose measurement: confounding issues in setting targets for inpatient management. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:403-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pitkin AD, Rice MJ. Challenges to glycemic measurement in the perioperative and critically ill patient: a review. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:1270-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nerhus K, Rustad P, Sandberg S. Effect of ambient temperature on analytical performance of self-monitoring blood glucose systems. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13:883-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Deakin S, Steele D, Clarke S, et al. Cook and chill: effect of temperature on the performance of nonequilibrated blood glucose meters. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;9:1260-1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Louie RF, Sumner SL, Belcher S, Mathew R, Tran NK, Kost GJ. Thermal stress and point-of-care testing performance: suitability of glucose test strips and blood gas cartridges for disaster response. Disaster Med Pub Health Prep. 2009;3:13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lam M, Louie RF, Curtis CM, et al. Short-term thermal-humidity shock affects point-of-care glucose testing: implications for health professionals and patients. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8:83-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Haller MJ, Shuster JJ, Schatz D, Melker RJ. Adverse impact of temperature and humidity on blood glucose monitoring reliability: a pilot study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bilen H, Kilicaslan A, Akcay G, Albayrak F. Performance of glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) based and glucose oxidase (GOX) based blood glucose meter systems at moderately high altitude. J Med Eng Technol. 2007;31:152-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. de Mol P, Krabbe HG, de Vries ST, et al. Accuracy of handheld blood glucose meters at high altitude. PLOS ONE. 2010;5:e15485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fink KS, Christensen DB, Ellsworth A. Effect of high altitude on blood glucose meter performance. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4:627-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oberg D, Ostenson CG. Performance of glucose dehydrogenase-and glucose oxidase-based blood glucose meters at high altitude and low temperature. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moore K, Vizzard N, Coleman C, McMahon J, Hayes R, Thompson CJ. Extreme altitude mountaineering and type 1 diabetes; the Diabetes Federation of Ireland Kilimanjaro Expedition. Diabet Med. 2001;18:749-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gautier JF, Bigard AX, Douce P, Duvallet A, Cathelineau G. Influence of simulated altitude on the performance of five blood glucose meters. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1430-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mortazavi S, Gholampour M, Haghani M, Mortazavi G, Mortazavi A. Electromagnetic radiofrequency radiation emittedfrom GSM mobile phones decreases the accuracy of home blood glucose monitors. J Biomed Phys Eng. 2014;4:111-116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tang Z, Lee JH, Louie RF, Kost GJ. Effects of different hematocrit levels on glucose measurements with handheld meters for point-of-care testing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1135-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Louie RF, Tang Z, Sutton DV, Lee JH, Kost GJ. Point-of-care glucose testing: effects of critical care variables, influence of reference instruments, and a modular glucose meter design. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ramljak S, Lock JP, Schipper C, et al. Hematocrit interference of blood glucose meters for patient self-measurement. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:179-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tang Z, Du X, Louie RF, Kost GJ. Effects of drugs on glucose measurements with handheld glucose meters and a portable glucose analyzer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:75-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Weber C, Neeser K. Glucose information for tight glycemic control: different methods with different challenges. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4:1269-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lyon ME, Lyon AW. Patient acuity exacerbates discrepancy between whole blood and plasma methods through error in molality to molarity conversion: “mind the gap!” Clin Biochem. 2011;44:412-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Solnica B, Skupien J, Kusnierz-Cabala B, et al. The effect of hematocrit on the results of measurements using glucose meters based on different techniques. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50:361-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tang Z, Louie RF, Lee JH, Lee DM, Miller EE, Kost GJ. Oxygen effects on glucose meter measurements with glucose dehydrogenase- and oxidase-based test strips for point-of-care testing. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1062-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kost GJ, Vu HT, Lee JH, et al. Multicenter study of oxygen-insensitive handheld glucose point-of-care testing in critical care/hospital/ambulatory patients in the United States and Canada. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:581-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Baumstark A, Schmid C, Pleus S, Haug C, Freckmann G. Influence of partial pressure of oxygen in blood samples on measurement performance in glucose-oxidase-based systems for self-monitoring of blood glucose. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:1513-1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Freckmann G, Schmid C, Baumstark A, Pleus S, Link M, Haug C. Partial pressure of oxygen in capillary blood samples from the fingertip. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:1648-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Montesinos P, Lorenzo I, Martin G, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: identification of risk factors and development of a predictive model. Haematologica. 2008;93:67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jadhav PP, Jadhav MP. Fallaciously elevated glucose level by handheld glucometer in a patient with chronic kidney disease and hypoglycemic encephalopathy. Int J Case Rep Images. 2013;4:485-488. [Google Scholar]

- 60. King DA, Ericson RP, Todd NW. Overestimation by a hand-held glucometer of blood glucose level due to icodextrin. Isr Med Assoc J. 2010;12:314-315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Koschinsky T, Heckermann S, Heinemann L. Parameters affecting postprandial blood glucose: effects of blood glucose measurement errors. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2:58-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Budiman ES, Samant N, Resch A. Clinical implications and economic impact of accuracy differences among commercially available blood glucose monitoring systems. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:365-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]