Abstract

Objective

Semaphorin 4D (Sema4D)/CD100 has pleiotropic roles in immune activation, angiogenesis, bone metabolism, and neural development. We undertook this study to investigate the role of Sema4D in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Soluble Sema4D (sSema4D) levels in serum and synovial fluid were analyzed by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay. Cell surface expression and transcripts of Sema4D were analyzed in peripheral blood cells from RA patients, and immunohistochemical staining of Sema4D was performed in RA synovium. Generation of sSema4D was evaluated in an ADAMTS‐4–treated monocytic cell line (THP‐1 cells). The efficacy of anti‐Sema4D antibody was evaluated in mice with collagen‐induced arthritis (CIA).

Results

Levels of sSema4D were elevated in both serum and synovial fluid from RA patients, and disease activity markers were correlated with serum sSema4D levels. Sema4D‐expressing cells also accumulated in RA synovium. Cell surface levels of Sema4D on CD3+ and CD14+ cells from RA patients were reduced, although levels of Sema4D transcripts were unchanged. In addition, ADAMTS‐4 cleaved cell surface Sema4D to generate sSema4D in THP‐1 cells. Soluble Sema4D induced tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) production from CD14+ monocytes. IL‐6 and TNFα induced ADAMTS‐4 expression in synovial cells. Treatment with an anti‐Sema4D antibody suppressed arthritis and reduced proinflammatory cytokine production in CIA.

Conclusion

A positive feedback loop involving sSema4D/IL‐6 and TNFα/ADAMTS‐4 may contribute to the pathogenesis of RA. The inhibition of arthritis by anti‐Sema4D antibody suggests that Sema4D represents a potential therapeutic target for RA.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common autoimmune disease that causes chronic inflammation of the synovium. RA synovitis evokes arthritis symptoms and leads to destruction of cartilage and bone in joints. Recent advances in understanding the pathogenesis of RA have revealed that complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors evoke autoimmunity, accompanied by the production of critical autoantigens such as citrullinated proteins 1, 2. Once RA has developed, autoimmunity is sustained and leads to persistent synovitis, which in turn causes destruction of bone and cartilage 3, 4. The mechanisms of sustained synovitis remain unclear. Recently, proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) were shown to have key roles in RA. Biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which can block these cytokines, constitute the current standard of care 5, 6. However, a substantial proportion of RA patients still do not achieve drug‐free remission of their disease with biologic DMARDs. In order for RA patients to achieve true remission of their disease, it will be necessary to identify another key molecular player that contributes to autoimmunity, immune activation, and bone destruction in RA.

Semaphorins were originally identified as neural guidance factors 7. The semaphorin family consists of more than 20 proteins, categorized into 8 subclasses based on their structural features 8. Recent research on semaphorins demonstrated that these proteins have pleiotropic roles, including regulation of immune responses 9, 10, angiogenesis 11, 12, tumor metastasis 13, 14, and bone metabolism 15, 16, 17. Semaphorins involved in various aspects of immune responses are referred to as “immune semaphorins” 18. Previous studies have shown that immune semaphorins have important roles in immunologic disorders, including multiple sclerosis (MS), airway hypersensitivity, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's) (GPA), and RA 9, 10. For instance, the level of soluble semaphorin 4A (sSema4A) is elevated in the serum of MS patients, in which Th17 cell populations are also increased 19. Recently, a SEMA6A variant was identified as a significant contributor to the risk of GPA 20. In addition, serum levels of Sema3A and Sema5A have been suggested to be relevant to RA 21, 22, 23. However, the pathologic significance of semaphorins in autoimmunity remains unclear.

Sema4D/CD100 was the first semaphorin shown to have a role in the immune system 24, 25, 26, and it was originally identified as a T cell activation marker 24. Indeed, Sema4D is abundantly expressed on the surface of T cells 24; however, it is also expressed in a broad range of hematopoietic cells. Although Sema4D is a membrane‐bound protein, it also exists as a functional soluble form (sSema4D) following proteolytic cleavage upon cellular activation 27, 28. Sema4D binds several receptors, plexin B1/B2, CD72, and plexin C1, which mediate the effects of Sema4D on neural cells, immune cells, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells 25, 29. Several studies have demonstrated that Sema4D has crucial roles in the immune system. For example, Sema4D promotes activation of B cells and antibody production by B cells 30, Sema4D expressed on dendritic cells (DCs) is involved in antigen‐specific T cell priming 31, Sema4D induces cytokine production by monocytes 32, and Sema4D mediates retrograde signals in mediating restoration of epithelium integrity 29.

Several studies have shown that Sema4D is relevant to the pathogenesis of autoimmunity. For instance, Sema4D‐deficient mice are resistant to the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis 33, a murine model of MS. Sema4D is expressed on tumor‐associated macrophages, and Sema4D produced by tumor‐associated macrophages is involved in tumor angiogenesis and vessel maturation 34. Notably, Sema4D derived from osteoclasts suppresses bone formation by osteoblasts, and blocking of Sema4D results in increased bone mass 15. Immune abnormality, angiogenesis, and bone destruction all have critical roles in the progression of RA 35, 36, suggesting that Sema4D might exacerbate RA. However, the involvement of Sema4D in the pathogenesis of RA has not yet been determined.

In this study, we found that sSema4D levels were elevated in serum and synovial fluid from RA patients. The increased levels of sSema4D were produced by an inflammation‐related proteolytic mechanism, and the resultant sSema4D in turn induced inflammation, suggesting the existence of an inflammatory activation loop in RA synovium. Inhibition of Sema4D ameliorated the symptoms of collagen‐induced arthritis (CIA). These results suggest that Sema4D represents a potential target for treatment of RA.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

Blood samples were obtained from 101 patients with RA, 34 with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), 10 with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and 10 with osteoarthritis (OA) at Osaka University Hospital and National Hospital Organization Osaka Minami Medical Center. Patients with RA were diagnosed according to the 1987 revised criteria of the American College of Rheumatology 37. Blood samples were also obtained from healthy individuals recruited from university staff, hospital staff, and the student population. Seven RA and 10 OA synovial tissue samples were obtained from patients undergoing synovectomy or knee replacement, and RA and OA synovial fluid samples were obtained from patients undergoing knee arthrocentesis. All samples were obtained after informed consent was provided by the subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with approval from the local ethics committees of Osaka University Hospital and National Hospital Organization Osaka Minami Medical Center. This study was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000013076).

Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs)

Soluble Sema4D levels in serum and synovial fluid samples and cell culture supernatants were measured using an ELISA kit (MyBioSource). Serum and synovial fluid samples were stored at −20°C prior to ELISAs. The lower detection limit of sSema4D was 125 pg/ml. Levels of ADAMTS‐4 in serum and synovial fluid samples were also determined using an ELISA kit (MyBioSource). The concentrations of human TNFα and IL‐6 in culture supernatants were determined using DuoSet ELISA kits for each cytokine (R&D Systems).

Histology

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on 7 RA and 10 OA synovial tissue samples. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and subjected to antigen retrieval by autoclaving in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 minutes at 125°C, after which endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with Dako REAL peroxidase blocking solution. Sections were allowed to react overnight with mouse anti‐Sema4D polyclonal antibody (1:100; BD Biosciences), mouse anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibody (1:100; Dako), Ready‐to‐Use mouse anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody (1:1; Dako), and Ready‐to‐Use mouse negative control Ig cocktail (1:1; Dako) or rabbit anti‐CD31 polyclonal antibody (1:50; Abcam). Slides were then incubated with a peroxidase‐labeled polymer conjugated to secondary anti‐rabbit antibodies using EnVisionTM1/HRP (Dako) and then developed with 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine as the chromogen.

Histologic analyses were performed on joints from mice with CIA. Hindlimb specimens from mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Wako Pure Chemical) and decalcified. Hematoxylin and eosin and Safranin O staining were used to assess synovitis.

Cell preparations

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated by density‐gradient centrifugation using Ficoll‐Paque Plus (GE Healthcare Bio‐Sciences). CD14+ monocytes were collected using CD14 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec), yielding >90% CD14+ cells.

Flow cytometry

PBMCs were prepared in heparinized tubes by Ficoll‐Paque density‐gradient centrifugation and then analyzed on a FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) using FlowJo software (Tree Star). To prevent nonspecific binding, cells (2 × 105) were incubated with human AB serum (Lonza) for 45 minutes at 4°C and then labeled with antibodies against indicated cell surface antigens. The following antibodies were used: fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti‐human Sema4D (A8; BioLegend), phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti‐human CD3 (HIT3a; BioLegend), PE‐conjugated anti‐human CD14 (M5E2; BioLegend), and PE‐conjugated anti‐human CD19 (HIB19; Tonbo Biosciences).

Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR)

CD3+, CD19+, or CD14+ cells (1 × 104) were sorted using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), and complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a SuperScript II cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT‐PCR analysis was performed on a 7900HT Fast Real‐Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using a TaqMan PCR protocol. Assay ID numbers for TaqMan primer sets (Applied Biosystems) were Hs00174819_m1 for human SEMA45 and HS00192708_m1 for human ADAMTS4. Expression levels of tested genes were normalized to that of the housekeeping gene ACTB (Hs01060665_g1) and calculated using the ΔCt method.

Shedding of sSema4D

The monocytic cell line THP‐1 and PBMCs from RA patients were cultured at 37°C for 12 hours in 96‐well plates at a density of 5 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10 μg/ml of matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP‐3; Sigma‐Aldrich), MMP‐9 (R&D Systems), ADAM‐17 (R&D Systems), and ADAMTS‐4 (R&D Systems). Soluble Sema4D concentrations were measured using an ELISA kit (MyBioSource).

Isolation of synovial cells and stimulation by IL‐6 and TNFα

Samples of knee articular synovium were obtained from RA patients. Synovial tissues were chopped finely and then digested for 45 minutes with continuous stirring at 37°C with collagenase D (800 Mandl units/ml; Roche) and dispase I (10 mg/ml; Invitrogen) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal calf serum (FCS). After digestion, the samples were filtered through a cell strainer (BD Biosciences). Adherent synovial cells were harvested and passaged into another dish. For experiments, synovial cells at passages 2–3 were seeded in 96‐well plates at 1 × 105 cells per well and then stimulated for 2 days with 1 μg/ml of IL‐6 and 0.1 μg/ml of TNFα (PeproTech) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% FCS. At the end of the stimulation period, cells were collected, and messenger RNA (mRNA) was extracted. Quantitative RT‐PCR analysis of ADAMTS‐4 was performed as described above. Concentrations of ADAMTS‐4 in culture supernatants were also measured by ELISA.

Monocyte culture and cytokine assays

CD14+ monocytes from RA patients (1 × 105) were stimulated with or without various concentrations of soluble human Sema4D‐Fc fusion protein, naturally cleaved sSema4D, or CD72 ligation antibody (BU40; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For blocking experiments, cells were cocultured with 1 μg/ml of naturally cleaved Sema4D and 10 μg/ml of anti‐Sema4D/CD100 antibody (3E9) (33) or isotype‐matched control IgG for 48 hours. Concentrations of human TNFα and IL‐6 in culture supernatants were determined by ELISA.

Human Sema4D‐Fc fusion protein and sSema4D were produced and purified as previously described 28, 32, and Recombinant Human IgG1 Fc (R&D Systems) was used as a control. Naturally cleaved sSema4D was affinity‐purified using a column containing CNBr‐activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow resin (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) conjugated to anti‐Sema4D monoclonal antibody (A8) as described previously 28.

Induction and assessment of CIA

Eight‐week‐old male DBA/1J mice were purchased from Oriental Yeast Company. Bovine type II collagen (2 mg/ml; Chondrex) was dissolved in 0.05M acetic acid and emulsified with an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant (Sigma‐Aldrich). Mice were immunized by intradermal injection at the base of the tail with 100 μl (2 mg/ml) of the emulsion (day 0). Booster injections of 100 μl of emulsion consisting of equal parts of Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Sigma‐Aldrich) and 2 mg/ml type II collagen in 0.05M acetic acid were administered at another site at the base of the tail on day 21. Mice with CIA received intraperitoneal injections of 50 mg/kg anti‐Sema4D antibody (BMA‐12) 30 (n = 6), 25 mg/kg anti‐Sema4D antibody (n = 8), or isotype control antibodies (Chugai Pharmaceutical) on day 28 and day 35. Serum was collected on day 42. Serum levels of IL‐6, TNFα, and IL‐1β were determined using a Bio‐Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine Assay (Bio‐Rad).

Serum titers of anti–type II collagen antibodies were detected by ELISA (Chondrex). Arthritis clinical scores were determined on a scale of 0–4 for each paw (0 = normal; 1 = erythema and swelling of 1 digit; 2 = erythema and swelling of 2 digits or erythema and swelling of the ankle joint; 3 = erythema and swelling of 3 digits or swelling of 2 digits and the ankle joint; and 4 = erythema and severe swelling of the ankle, foot, and digits with deformity). Two paws of each mouse were evaluated histologically. Joint pathology was assessed and quantitated as described previously 38. The paws of mice treated with anti‐Sema4D antibody (n = 12), control antibody (n = 12), or no antibody (n = 12) were stained with anti‐CD31 antibodies. Vessels were counted manually in 5 fields (40×) per paw and averaged. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Osaka University.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD or mean ± SEM. Nonparametric Mann‐Whitney U tests were used to compare 2 groups, and comparisons between 3 groups were performed using the Kruskal‐Wallis test followed by the Mann‐Whitney U test. P values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant. Correlations between clinical parameters and serum sSema4D levels were determined using Pearson's correlation coefficient (r).

RESULTS

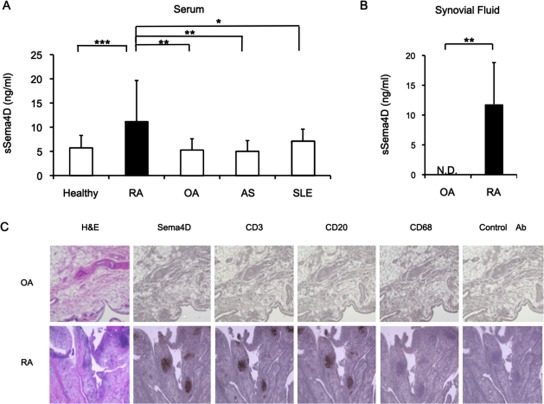

Elevation of sSema4D levels in RA, and accumulation of Sema4D‐expressing cells in RA synovium

To investigate the pathologic implications of Sema4D in RA, we first measured the serum concentrations of Sema4D in patients with several autoimmune and joint‐destructive diseases. As shown in Figure 1A, serum sSema4D levels were significantly higher in RA patients than in healthy individuals (mean ± SD 11.2 ± 8.4 ng/ml versus 5.6 ± 2.7 ng/ml; P < 0.001) (demographics and characteristics of RA patients are shown in Supplementary Table 1, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract). In contrast, serum sSema4D levels were not elevated in patients with OA, AS, or SLE (mean ± SD 5.2 ± 2.4 ng/ml, 4.9 ± 2.3 ng/ml, and 7.0 ± 2.6 ng/ml, respectively). Notably, Sema4D levels were also elevated in the synovial fluid of RA patients (mean ± SD 11.8 ± 7.0 ng/ml), but Sema4D was undetectable in the synovial fluid of OA patients (P < 0.01) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Levels of soluble semaphorin 4D (sSema4D) in serum and synovial fluid samples from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and Sema4D protein expression in RA synovium. A, Soluble Sema4D levels in serum samples from healthy individuals and from 101 patients with RA, 10 patients with osteoarthritis (OA), 10 patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and 34 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). B, Levels of sSema4D in synovial fluid samples from 7 RA patients and 10 OA patients. Values in A and B are the mean ± SD. ND = not detectable. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; ***= P < 0.001. C, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemical staining for Sema4D, CD3, CD20, and CD68 in synovial tissue samples from patients with OA or RA. Images shown are representative of samples from 7 RA patients and 10 OA patients. Original magnification × 40. Ab = antibody.

Table 1.

Correlations between levels of soluble semaphorin 4D and clinical features in the 101 patients with rheumatoid arthritisa

| Category, feature | r | P |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical disease activity (DAS28) | 0.383 | <0.01 |

| Autoantibodies | ||

| RF | 0.328 | <0.01 |

| ACPA | −0.041 | NS |

| Biomarkers | ||

| CRP | 0.346 | <0.01 |

| MMP‐3 | 0.055 | NS |

| Bone turnover markers | ||

| BAP | 0.255 | <0.05 |

| Osteocalcin | 0.092 | NS |

| Urinary deoxypyridinoline | 0.318 | <0.05 |

| ICTP | 0.091 | NS |

| Serum NTX | 0.026 | NS |

| Spine DXA | −0.145 | NS |

DAS28 = Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; RF = rheumatoid factor; ACPA = anti–citrullinated protein antibody; NS = not significant; CRP = C‐reactive protein; MMP‐3 = matrix metalloproteinase 3; BAP = bone alkaline phosphatase; ICTP = C‐terminal crosslinking telopeptide of type I collagen; NTX =N‐telopeptide of type I collagen; DXA = dual x‐ray absorptiometry.

Immunohistochemical staining revealed accumulation of Sema4D‐positive cells in RA synovium, clustered mainly in follicle‐like germinal centers. However, such accumulation and clustering of Sema4D‐expressing cells were not observed in OA synovium (Figure 1C). CD3 and CD20 were colocalized in Sema4D‐stained follicle‐like germinal centers, indicating that the Sema4D‐expressing cells were synovial infiltrating lymphocytes (see Supplementary Figure 1, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract). In contrast, CD68+ macrophages faintly expressed Sema4D. Additionally, the distribution of CD68+ cells was patchy, and their localization patterns were different from those of T and B cells.

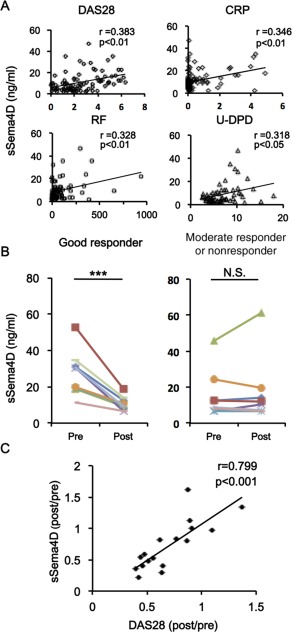

Correlation of serum sSema4D levels with RA disease activity and biomarkers

To determine the clinical implications of sSema4D, we examined the correlations between serum sSema4D levels and clinical features. Table 1 summarizes the correlations between patients’ clinical features and serum sSema4D levels. There were no apparent correlations between sSema4D levels and age, sex, disease duration, or medications (data not shown). In contrast, serum sSema4D levels were positively correlated with disease activity markers such as the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) 39 (r = 0.383, P < 0.01), the C‐reactive protein (CRP) level (r = 0.346, P < 0.01), and the rheumatoid factor (RF) titer (r = 0.328, P < 0.01). In addition, levels of bone metabolic markers such as bone alkaline phosphatase (BAP) (r = 0.255, P < 0.05) and urinary deoxypyridinoline (r = 0.318, P < 0.05) correlated with serum sSema4D levels.

Scatterplots confirmed the relationships between serum levels of sSema4D and these disease activity markers (Figure 2A). Sequential analysis of serum sSema4D levels was performed in RA patients treated with biologic DMARDs (n = 17); specifically, serum levels of sSema4D were evaluated before and 6 months after initiation of biologic DMARD therapy (14 patients were treated with TNF inhibitors, and 3 patients were treated with tocilizumab). A significant decrease in serum sSema4D levels after biologic DMARD treatment was observed in patients who were good responders according to the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria 40 (Figure 2B). In contrast, sSema4D levels were not changed in patients with a moderate response or no response (Figure 2B). The posttreatment change ratio of Sema4D after biologic DMARD treatment was significantly correlated with the change ratio of the DAS28 (r = 0.799, P < 0.001) (Figure 2C), suggesting the involvement of Sema4D in determining the clinical status of RA. The reductions in serum sSema4D levels did not differ significantly between patients treated with TNF inhibitors and those treated with an IL‐6 inhibitor. Thus, the reduction in serum sSema4D levels simply correlated with reduction in disease activity.

Figure 2.

Correlations of serum levels of soluble semaphorin 4D (sSema4D) with markers of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. A, Positive correlation of serum sSema4D levels with the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28), the C‐reactive protein (CRP) level, the rheumatoid factor (RF) titer, and the level of urinary deoxypyridinoline (u‐DPD). B, Serum sSema4D levels before and after biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment in 9 good responders and 8 moderate responders or nonresponders according to the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria. *** = P < 0.001. NS = not significant. C, Correlation of change ratio in serum sSema4D levels with change ratio of DAS28 after treatment with biologic DMARDs (n = 17 samples).

Shedding of Sema4D in RA patients

Sema4D is abundantly expressed in T cells but weakly expressed in other cell types such as B cells 24. Sema4D is also expressed on antigen‐presenting cells, including macrophages and DCs 32. As shown in Figure 1C, we observed Sema4D‐expressing cells in the synovium. Next, we examined Sema4D expression in PBMCs from RA patients and healthy individuals. In healthy individuals, cell surface Sema4D was expressed abundantly on CD3+ and CD14+ cells and at lower levels on CD19+ cells (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the cell surface expression of Sema4D was down‐regulated on all cells from RA patients, especially on cells positive for CD3 or CD14. In contrast, qRT‐PCR revealed that the expression of mRNA for Sema4D was not reduced in RA patients (Figure 3B), suggesting that the reduction in cell surface Sema4D was due to shedding of Sema4D from the cell surface.

Figure 3.

Semaphorin 4D (Sema4D) expression, and soluble Sema4D (sSema4D) production with ADAMTS‐4 as the sheddase. A, Histograms of cell surface expression of Sema4D in peripheral blood CD3+, CD19+, and CD14+ cells. Results shown are representative of findings from 5 rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients and 5 healthy individuals. B, Expression of mRNA for Sema4D in peripheral blood CD3+, CD19+, and CD14+ cells. Results shown are from 5 RA patients and 5 healthy individuals. C, Levels of sSema4D in culture supernatant of THP‐1 cells cultured with recombinant matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP‐3), MMP‐9, ADAM‐17, and ADAMTS‐4 (n = 5 samples per group). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. D, Serum levels of ADAMTS‐4 in 20 RA patients and 16 healthy individuals. E, Synovial fluid levels of ADAMTS‐4 in 7 RA patients and 10 osteoarthritis (OA) patients. Values in B–E are the mean ± SEM. ** = P < 0.01. NS = not significant.

Previous studies showed that although Sema4D is a membrane‐bound protein, it can be cleaved from the cell surface by metalloproteinases to yield a soluble form 27. Therefore, we examined the proteolytic cleavage of Sema4D. ADAMs, ADAMTS, and MMPs are proteolytic enzymes that digest extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen, and they process bioactive substances that have a physiologic role in RA 41. We incubated Sema4D‐expressing cells (THP‐1 cells) with recombinant metalloproteinases including MMP‐3, MMP‐9, ADAM‐17, and ADAMTS‐4, and then we measured sSema4D levels in the culture supernatants. ADAMTS‐4 significantly induced the release of sSema4D into the culture supernatant (Figure 3C) (see Supplementary Figure 2, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract). Consistent with this, we detected elevated levels of ADAMTS‐4 in serum and synovial fluid in the RA patients examined in this study (Figures 3D and E).

Proinflammatory cytokine production by sSema4D

To determine the pathogenic role of elevated sSema4D levels in RA, we investigated the effect of sSema4D on TNFα and IL‐6 production. Treatment with naturally cleaved sSema4D increased production of TNFα and IL‐6 by CD14+ monocytes in a dose‐dependent manner (Figure 4A). In addition, recombinant sSema4D‐Fc fusion protein also induced TNFα and IL‐6 production by PBMCs in a dose‐dependent manner (see Supplementary Figure 3, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract). Moreover, anti‐Sema4D antibody suppressed TNFα and IL‐6 production induced by sSema4D (Figure 4B). CD72 is a receptor for Sema4D, and a CD72 ligation antibody also induced TNFα and IL‐6 production in CD14+ monocytes, in which Sema4D induced dephosphorylation of CD72 (see Supplementary Figures 4 and 5, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract).

Figure 4.

Inflammatory cytokine production induced by semaphorin 4D (Sema4D), and elevated ADAMTS‐4 expression by inflammatory cytokines. A, Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) levels in culture supernatant of CD14+ monocytes from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients after stimulation with naturally cleaved soluble Sema4D (sSema4D) for 72 hours. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. B, TNFα and IL‐6 levels in culture supernatant of CD14+ monocytes from RA patients after stimulation with naturally cleaved sSema4D for 48 hours with or without anti‐Sema4D antibody. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. C and D, Elevated expression of ADAMTS‐4 mRNA (C) and elevated ADAMTS‐4 protein levels (D) in primary cultures of TNFα‐ and IL‐6–stimulated synovial cells from RA patients. Data were compiled from 5 independent experiments. Values are the mean ± SEM. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01. non = not stimulated.

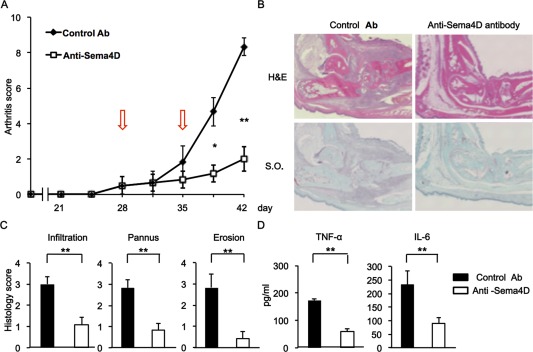

Figure 5.

Blocking of semaphorin 4D (Sema4D) ameliorates severity of collagen‐induced arthritis (CIA) in mice. A, Average arthritis scores of mice with CIA. Anti‐Sema4D or control antibody (Ab) (50 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally on days 28 and 35 (arrows) (n = 6 mice per group). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. B, Sections of a mouse ankle joint on day 42 after first immunization. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Safranin O (SO). Original magnification × 100. C, Average pathologic scores of paw sections on day 42 (n = 6 mice per group). D, Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) on day 42 (n = 6 mice per group). Values are the mean ± SEM and are representative of 3 independent experiments. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01.

Because previous studies showed that inflammatory cytokines induce ADAMTS‐4 in synovial cells 42, we examined ADAMTS‐4 production in TNFα‐ and IL‐6–stimulated synovial cells. TNFα and IL‐6 treatment increased mRNA and protein levels of ADAMTS‐4 (Figures 4C and D). These results not only indicated that sSema4D can induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines but also implied that such cytokines in turn up‐regulate the cleavage of Sema4D by ADAMTS‐4.

Amelioration of CIA severity by blocking of Sema4D

To determine the pathologic roles of Sema4D in arthritis, we examined the effect of anti‐Sema4D antibody treatment on CIA. Arthritis scores in anti‐Sema4D antibody–treated mice were significantly lower than those in control mice (Figure 5A), and the decrease in arthritis scores was attenuated in mice treated with half a dose of antibody (see Supplementary Figure 6, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract). Histologic analysis revealed that blocking Sema4D in mice with CIA also reduced inflammatory infiltration into the synovium, decreased pannus formation, and ameliorated erosion of adjacent cartilage and bone (Figure 5B). Histologic scores in the joints of anti‐Sema4D antibody–treated mice were significantly reduced (Figure 5C). Furthermore, serum TNFα and IL‐6 levels on day 42 were significantly reduced in anti‐Sema4D antibody–treated mice (Figure 5D). We evaluated angiogenesis by antibody staining for CD31, a marker of blood vessel endothelium. Mice treated with anti‐Sema4D antibody exhibited poor induction of angiogenesis at sites of inflammation (see Supplementary Figures 7A and B, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract). Additionally, the serum level of anticollagen antibody was reduced in these animals (see Supplementary Figure 8, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the clinical implications of sSema4D in RA. Levels of sSema4D were elevated in RA serum and synovial fluid. However, sSema4D levels were not elevated in OA and SLE, suggesting that high sSema4D levels are specifically associated with RA. Serum sSema4D levels correlated with known clinical and biologic markers of RA (Table 1). In particular, serum sSema4D levels correlated with the DAS28, the CRP level, the RF titer, and the urinary deoxypyridinoline level in RA patients. Successful treatment of RA reduced serum sSema4D levels, and reductions in the sSema4D level were significantly correlated with reductions in clinical disease activity as measured by the DAS28. Collectively, these results suggest that sSema4D is a potentially useful biomarker for RA disease activity. In addition, serum sSema4D levels were correlated with levels of CRP, a well‐known acute‐phase protein induced by proinflammatory cytokines such as IL‐1β, IL‐6, and TNFα (43). Because sSema4D induced IL‐6 and TNFα production from CD14+ monocytes, it is possible that sSema4D affects CRP production via induction of IL‐6 and TNFα in RA patients. The RF titer was also correlated with serum sSema4D levels. Given that Sema4D has been implicated in activation of B cells and antibody production 28, 31, sSema4D may be directly relevant to RF production.

Recent work showed that Sema4D expressed in osteoclasts inhibits bone regeneration by inhibiting osteoblasts 15. Consistent with this, we found that some bone metabolic markers were correlated with serum sSema4D levels in RA (Table 1). The bone formation marker BAP and the bone resorption marker urinary deoxypyridinoline were correlated with serum sSema4D levels. However, other bone formation markers (such as osteocalcin) and bone resorption markers (such as C‐terminal crosslinking telopeptide of type I collagen and serum N‐telopeptide of type I collagen) were not correlated with serum sSema4D levels. The relationship between serum sSema4D levels and bone metabolic markers in RA patients is a subject of controversy, although the local concentration of Sema4D may be relevant to joint destruction in RA. Further studies will be needed to determine the importance of Sema4D in bone destruction in RA.

Because Sema4D is strongly expressed in immune cells 24, we initially assumed that elevated expression of SEMA4D explained the increase in sSema4D in RA serum and synovial fluid. Contrary to our expectation, however, fluorescence‐activated cell sorting analysis revealed that levels of Sema4D were actually reduced in lymphocytes and monocytes from the peripheral blood of RA patients. Because expression of Sema4D mRNA was stable in all cells, it is likely that the relative reduction in cellular levels of Sema4D was due to cleavage and shedding of Sema4D from the cell surface. In support of this notion, a previous study showed that EDTA, an inhibitor of metalloproteinases, inhibits sSema4D secretion, suggesting that sSema4D is produced via a shedding mechanism 27. Other studies showed that ADAM‐17 regulates Sema4D exodomain cleavage on activated platelets 44, 45. Taken together, the results of these studies prompted us to investigate the generation and function of Sema4D.

We examined several proteolytic enzymes as candidate sheddases for sSema4D. Proteolytic enzymes such as ADAMTS, ADAMs, and MMPs influence inflammation and progression of arthritis 46, 47, 48. Herein we showed that induction of sSema4D is dependent on ADAMTS‐4. Originally, ADAMTS‐4 was considered to have a key role in the degradation of cartilage proteoglycan (aggrecan) in OA and RA. Consistent with this, levels of ADAMTS‐4 were elevated in RA serum, and TNFα and IL‐6 induced the production of ADAMTS‐4.

In this study, we demonstrated that production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL‐6 increased upon stimulation with sSema4D. We also showed that sSema4D induced dephosphorylation of CD72 (see Supplementary Figure 5, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract). CD72 contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine–based inhibition motif in its cytoplasmic region 49. Investigators in our group have previously reported that Sema4D induces dephosphorylation of CD72, turning off its negative signal in B cells 32. It thus appears that Sema4D is involved in cytokine production in monocytes as well.

Our results indicated that sSema4D induces TNFα and IL‐6 production and that both TNFα and IL‐6 can induce ADAMTS‐4, which is involved in generation of sSema4D. Therefore, we hypothesized that the vicious circle of sSema4D/TNFα/IL‐6/ADAMTS‐4 functions as an autocrine accelerator of the IL‐6/TNFα inflammatory axis in RA. It is well known that TNFα and IL‐6 induce osteoclastogenesis through RANKL production, and ADAMTS‐4 induces cartilage degradation in RA 48. In addition, Sema4D inhibits bone formation 15. Therefore, the autocrine loop involving Sema4D induces cartilage destruction, inhibits bone regeneration, and evokes continuous inflammatory symptoms. This Sema4D loop may have a central role in RA inflammation and the associated joint destruction (see Supplementary Figure 9, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.39086/abstract).

We analyzed the effect of anti‐Sema4D antibody treatment in a mouse model of inflammatory arthritis. Blocking Sema4D in CIA exerted favorable therapeutic effects, decreasing destruction of cartilage and bone, cell infiltration into the synovium, and production of TNFα and IL‐6 (Figure 5). To investigate the therapeutic effects of anti‐Sema4D antibody on ongoing arthritis, we administered anti‐Sema4D antibody after arthritis had already commenced. These observations suggest that Sema4D represents a possible therapeutic target for treatment of RA. Recently developed biologic DMARDs inhibit TNFα and IL‐6 function; however, these therapies do not inhibit cytokine production directly. Therefore, RA flares are often observed after cessation of biologic DMARD therapy. Thus, it seems likely that direct inhibition of TNFα and IL‐6 production by anti‐Sema4D therapy would be useful for RA management. An anti‐Sema4D antibody is currently undergoing a phase I clinical trial (NCT01313065) in cancer patients 50. However, the long‐term feasibility of anti‐Sema4D antibody is still unknown. Careful and well‐designed clinical applications will be needed.

In summary, we demonstrated that serum sSema4D levels are well correlated with known markers of clinical features and laboratory findings. The critical roles of Sema4D in RA pathogenesis suggest that Sema4D is a potential novel target for RA treatment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Drs. Yoshida and Ogata had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Yoshida, Ogata, Kumanogoh.

Acquisition of data. Yoshida, Ogata, Ebina, Shi, Nojima, Kimura, Ito, Morimoto, Nishide, Hosokawa, Hirano, Shima, Narazaki, Tsuboi, Saeki, Tomita, Tanaka.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Yoshida, Ogata, Kang, Kumanogoh.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure 1. Sema4D expression in RA synovium Immunohistochemical staining for Sema4D, CD3, CD20, and CD68 in synovial tissue of patients with RA. Representative images from seven RA patients are shown. (40× field)

Supplementary Figure 2. sSema4D production from PBMCs Levels of sSema4D in culture supernatant of PBMCs from healthy individuals and RA patients (n = 5 per group). Data are representative of three independent experiments. ** p < 0.01.

Supplementary Figure 3. sSema4D‐Fc induces production of inflammatory cytokines. TNF‐α and IL‐6 levels in culture supernatant of CD14+ monocytes from RA patients stimulated with Sema4D‐Fc protein (n = 5). Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. ** p < 0.01.

Supplementary Figure 4. CD72 agonistic antibody induces production of inflammatory cytokines. CD72 agonistic antibody induced TNF‐α and IL‐6 production from CD14+ monocytes from RA patients. Representative results of three independent experiments are shown (n = 5). ** p < 0.01.

Supplementary Figure 5. Sema4D induces tyrosine dephosphorylation of CD72 in THP‐1 cells Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of CD72 was significantly reduced following sSema4D treatment of THP‐1 cells. 1 × 107 THP‐1 cells were stimulated with 1 μg/ml of sSema4D and phosphorylation of CD72 were evaluated by western blotting. Method was described previously 32.

Supplementary Figure 6. Dose dependent effect of anti‐Sema4D to suppress CIA. Average arthritis scores of CIA mice. Anti‐Sema4D or control antibody (25 mg/kg) was administrated intraperitoneally on days 28 and 35 (arrow). (n = 8 per group). Data are representative of two independent experiments. *** p < 0.001.

Supplementary Figure 7. Anti‐Sema4D antibody inhibits angiogenesis of CIA. Total synovial vessel density (assessed on paraffin sections immunohistochemically stained for CD31) in mice treated with control antibody or anti‐Sema4D antibody. A) photomicrographs of synovial membrane tissues stained for CD31. B) Average density of vessels (vessels/mm2). (n = 12 per group). * p < 0.05.

Supplementary Figure 8. Anti‐Sema4D antibody inhibits collagen‐specific IgG production Collagen‐specific IgG production in sera of mice treated with control or anti‐Sema4D antibody (n = 6 per group). * p < 0.05. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Supplementary Figure 9. Sema4D is a key component of the autocrine inflammatory loop in RA. We hypothesized that the sSema4D/TNF‐α and IL‐6/ADAMTS4 axis functions as a vicious cycle, triggering an inflammatory loop that contributes to the pathogenesis of RA. TNF‐α and IL‐6 induce osteoclastogenesis through RANKL production, and ADAMTS4 induces cartilage degradation in RA (47). In addition, Sema4D inhibits bone formation (15). Thus, Sema4D may play a central role in RA as a component of an autocrine inflammatory loop.

Supplementary Table 1. Demographics and characteristics of RA patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the patients and healthy volunteers who participated in this research.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kochi Y, Suzuki A, Yamamoto K. Genetic basis of rheumatoid arthritis: a current review. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014;452:254–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holmdahl R, Malmstrom V, Burkhardt H. Autoimmune priming, tissue attack and chronic inflammation: the three stages of rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol 2014;44:1593–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ogura H, Murakami M, Okuyama Y, Tsuruoka M, Kitabayashi C, Kanamoto M, et al. Interleukin‐17 promotes autoimmunity by triggering a positive‐feedback loop via interleukin‐6 induction. Immunity 2008;29:628–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhao W, Zhang C, Shi M, Zhang J, Li M, Xue X, et al. The discoidin domain receptor 2/annexin A2/matrix metalloproteinase 13 loop promotes joint destruction in arthritis through promoting migration and invasion of fibroblast‐like synoviocytes. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:2355–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cessak G, Kuzawinska O, Burda A, Lis K, Wojnar M, Mirowska‐Guzel D, et al. TNF inhibitors: mechanisms of action, approved and off‐label indications. Pharmacol Rep 2014;66:836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshida Y, Tanaka T. Interleukin 6 and rheumatoid arthritis. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:698313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kolodkin AL. Semaphorins: mediators of repulsive growth cone guidance. Trends Cell Biol 1996;6:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhou Y, Gunput RA, Pasterkamp RJ. Semaphorin signaling: progress made and promises ahead. Trends Biochem Sci 2008;33:161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takamatsu H, Kumanogoh A. Diverse roles for semaphorin‐plexin signaling in the immune system. Trends Immunol 2012;33:127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumanogoh A, Kikutani H. Immunological functions of the neuropilins and plexins as receptors for semaphorins. Nat Rev Immunol 2013;13:802–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vadasz Z, Attias D, Kessel A, Toubi E. Neuropilins and semaphorins: from angiogenesis to autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev 2010;9:825–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gu C, Giraudo E. The role of semaphorins and their receptors in vascular development and cancer. Exp Cell Res 2013;319:1306–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rehman M, Tamagnone L. Semaphorins in cancer: biological mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2013;24:179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rizzolio S, Tamagnone L. Semaphorin signals on the road to cancer invasion and metastasis. Cell Adh Migr 2007;1:62–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Negishi‐Koga T, Shinohara M, Komatsu N, Bito H, Kodama T, Friedel RH, et al. Suppression of bone formation by osteoclastic expression of semaphorin 4D. Nat Med 2011;17:1473–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hayashi M, Nakashima T, Taniguchi M, Kodama T, Kumanogoh A, Takayanagi H. Osteoprotection by semaphorin 3A. Nature 2012;485:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fukuda T, Takeda S, Xu R, Ochi H, Sunamura S, Sato T, et al. Sema3A regulates bone‐mass accrual through sensory innervations. Nature 2013;497:490–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumanogoh A, Kikutani H. Immune semaphorins: a new area of semaphorin research. J Cell Sci 2003;116:3463–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakatsuji Y, Okuno T, Moriya M, Sugimoto T, Kinoshita M, Takamatsu H, et al. Elevation of Sema4A implicates Th cell skewing and the efficacy of IFN‐β therapy in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2012;188:4858–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xie G, Roshandel D, Sherva R, Monach PA, Lu EY, Kung T, et al. Association of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's) with HLA–DPB1*04 and SEMA6A gene variants: evidence from genome‐wide analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2457–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Catalano A. The neuroimmune semaphorin‐3A reduces inflammation and progression of experimental autoimmune arthritis. J Immunol 2010;185:6373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gras C, Eiz‐Vesper B, Jaimes Y, Immenschuh S, Jacobs R, Witte T, et al. Secreted semaphorin 5A activates immune effector cells and is a biomarker for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:1461–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vadasz Z, Haj T, Halasz K, Rosner I, Slobodin G, Attias D, et al. Semaphorin 3A is a marker for disease activity and a potential immunoregulator in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14:R146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bougeret C, Mansur IG, Dastot H, Schmid M, Mahouy G, Bensussan A, et al. Increased surface expression of a newly identified 150‐kDa dimer early after human T lymphocyte activation. J Immunol 1992;148:318–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elhabazi A, Marie‐Cardine A, Chabbert‐de Ponnat I, Bensussan A, Boumsell L. Structure and function of the immune semaphorin CD100/SEMA4D. Crit Rev Immunol 2003;23:65–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang Y, Liu B, Ma Y, Jin B. Sema 4D/CD100‐plexin B is a multifunctional counter‐receptor. Cell Mol Immunol 2013;10:97–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Elhabazi A, Delaire S, Bensussan A, Boumsell L, Bismuth G. Biological activity of soluble CD100. I. The extracellular region of CD100 is released from the surface of T lymphocytes by regulated proteolysis. J Immunol 2001;166:4341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang X, Kumanogoh A, Watanabe C, Shi W, Yoshida K, Kikutani H. Functional soluble CD100/Sema4D released from activated lymphocytes: possible role in normal and pathologic immune responses. Blood 2001;97:3498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ji JD, Ivashkiv LB. Roles of semaphorins in the immune and hematopoietic system. Rheumatol Int 2009;29:727–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kumanogoh A, Watanabe C, Lee I, Wang X, Shi W, Araki H, et al. Identification of CD72 as a lymphocyte receptor for the class IV semaphorin CD100: a novel mechanism for regulating B cell signaling. Immunity 2000;13:621–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shi W, Kumanogoh A, Watanabe C, Uchida J, Wang X, Yasui T, et al. The class IV semaphorin CD100 plays nonredundant roles in the immune system: defective B and T cell activation in CD100‐deficient mice. Immunity 2000;13:633–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ishida I, Kumanogoh A, Suzuki K, Akahani S, Noda K, Kikutani H. Involvement of CD100, a lymphocyte semaphorin, in the activation of the human immune system via CD72: implications for the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses. Int Immunol 2003;15:1027–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Okuno T, Nakatsuji Y, Moriya M, Takamatsu H, Nojima S, Takegahara N, et al. Roles of Sema4D–plexin‐B1 interactions in the central nervous system for pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2010;184:1499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sierra JR, Corso S, Caione L, Cepero V, Conrotto P, Cignetti A, et al. Tumor angiogenesis and progression are enhanced by Sema4D produced by tumor‐associated macrophages. J Exp Med 2008;205:1673–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Semerano L, Clavel G, Assier E, Denys A, Boissier MC. Blood vessels, a potential therapeutic target in rheumatoid arthritis? Joint Bone Spine 2011;78:118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Okamoto K, Takayanagi H. Regulation of bone by the adaptive immune system in arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Williams‐Skipp C, Raman T, Valuck RJ, Watkins H, Palmer BE, Scheinman RI. Unmasking of a protective tumor necrosis factor receptor I–mediated signal in the collagen‐induced arthritis model. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:408–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty‐eight–joint counts: development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Gestel AM, Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis: comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nagase H, Kashiwagi M. Aggrecanases and cartilage matrix degradation. Arthritis Res Ther 2003;5:94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tian Y, Yuan W, Fujita N, Wang J, Wang H, Shapiro IM, et al. Inflammatory cytokines associated with degenerative disc disease control aggrecanase‐1 (ADAMTS‐4) expression in nucleus pulposus cells through MAPK and NF‐κB. Am J Pathol 2013;182:2310–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yeh ET. CRP as a mediator of disease. Circulation 2004;109:II11–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhu L, Bergmeier W, Wu J, Jiang H, Stalker TJ, Cieslak M, et al. Regulated surface expression and shedding support a dual role for semaphorin 4D in platelet responses to vascular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:1621–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mou P, Zeng Z, Li Q, Liu X, Xin X, Wannemacher KM, et al. Identification of a calmodulin‐binding domain in Sema4D that regulates its exodomain shedding in platelets. Blood 2013;121:4221–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lin EA, Liu CJ. The role of ADAMTSs in arthritis. Protein Cell 2010;1:33–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Edwards DR, Handsley MM, Pennington CJ. The ADAM metalloproteinases. Mol Aspects Med 2008;29:258–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Burrage PS, Mix KS, Brinckerhoff CE. Matrix metalloproteinases: role in arthritis. Front Biosci 2006;11:529–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kumanogh A, Kikutani H. The CD100‐CD72 interaction: a novel mechanism of immune regulation. Trends Immunol 2001;22:670–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Patnaik A, Ramanathan RK, Rasco DW, Weiss GJ, Campello‐Iddison V, Eddington C, et al. Phase 1 study of VX15/2503, a humanized IgG4 anti‐SEMA4D antibody, in advanced cancer patients [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2014;32 Suppl:5s. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Sema4D expression in RA synovium Immunohistochemical staining for Sema4D, CD3, CD20, and CD68 in synovial tissue of patients with RA. Representative images from seven RA patients are shown. (40× field)

Supplementary Figure 2. sSema4D production from PBMCs Levels of sSema4D in culture supernatant of PBMCs from healthy individuals and RA patients (n = 5 per group). Data are representative of three independent experiments. ** p < 0.01.

Supplementary Figure 3. sSema4D‐Fc induces production of inflammatory cytokines. TNF‐α and IL‐6 levels in culture supernatant of CD14+ monocytes from RA patients stimulated with Sema4D‐Fc protein (n = 5). Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. ** p < 0.01.

Supplementary Figure 4. CD72 agonistic antibody induces production of inflammatory cytokines. CD72 agonistic antibody induced TNF‐α and IL‐6 production from CD14+ monocytes from RA patients. Representative results of three independent experiments are shown (n = 5). ** p < 0.01.

Supplementary Figure 5. Sema4D induces tyrosine dephosphorylation of CD72 in THP‐1 cells Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of CD72 was significantly reduced following sSema4D treatment of THP‐1 cells. 1 × 107 THP‐1 cells were stimulated with 1 μg/ml of sSema4D and phosphorylation of CD72 were evaluated by western blotting. Method was described previously 32.

Supplementary Figure 6. Dose dependent effect of anti‐Sema4D to suppress CIA. Average arthritis scores of CIA mice. Anti‐Sema4D or control antibody (25 mg/kg) was administrated intraperitoneally on days 28 and 35 (arrow). (n = 8 per group). Data are representative of two independent experiments. *** p < 0.001.

Supplementary Figure 7. Anti‐Sema4D antibody inhibits angiogenesis of CIA. Total synovial vessel density (assessed on paraffin sections immunohistochemically stained for CD31) in mice treated with control antibody or anti‐Sema4D antibody. A) photomicrographs of synovial membrane tissues stained for CD31. B) Average density of vessels (vessels/mm2). (n = 12 per group). * p < 0.05.

Supplementary Figure 8. Anti‐Sema4D antibody inhibits collagen‐specific IgG production Collagen‐specific IgG production in sera of mice treated with control or anti‐Sema4D antibody (n = 6 per group). * p < 0.05. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Supplementary Figure 9. Sema4D is a key component of the autocrine inflammatory loop in RA. We hypothesized that the sSema4D/TNF‐α and IL‐6/ADAMTS4 axis functions as a vicious cycle, triggering an inflammatory loop that contributes to the pathogenesis of RA. TNF‐α and IL‐6 induce osteoclastogenesis through RANKL production, and ADAMTS4 induces cartilage degradation in RA (47). In addition, Sema4D inhibits bone formation (15). Thus, Sema4D may play a central role in RA as a component of an autocrine inflammatory loop.

Supplementary Table 1. Demographics and characteristics of RA patients.