Abstract

Background

A lack of longitudinal studies has hampered the understanding of the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in parents of children diagnosed with cancer. This study examines level of PTSS and prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from shortly after diagnosis up to 5 years after end of treatment or child's death, in mothers and fathers.

Methods

A design with seven assessments (T1–T7) was used. T1–T3 were administered during treatment and T4–T7 after end of treatment or child's death. Parents (N = 259 at T1; n = 169 at T7) completed the PTSD Checklist Civilian Version. Latent growth curve modeling was used to analyze the development of PTSS.

Results

A consistent decline in PTSS occurred during the first months after diagnosis; thereafter the decline abated, and from 3 months after end of treatment only minimal decline occurred. Five years after end of treatment, 19% of mothers and 8% of fathers of survivors reported partial PTSD. Among bereaved parents, corresponding figures were 20% for mothers and 35% for fathers, 5 years after the child's death.

Conclusions

From 3 months after end of treatment the level of PTSS is stable. Mothers and bereaved parents are at particular risk for PTSD. The results are the first to describe the development of PTSS in parents of children diagnosed with cancer, illustrate that end of treatment is a period of vulnerability, and that a subgroup reports PTSD 5 years after end of treatment or child's death. © 2015 The Authors. Psycho‐Oncology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Keywords: cancer, oncology, children, parents, posttraumatic stress

Introduction

A clinically significant level of posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) has been reported by 22–68% of parents of children on cancer treatment and 10–44% of parents of survivors of childhood cancer 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. PTSS are associated with psychiatric comorbidity, reduced quality of life, work impairment, and increased healthcare costs 6, and may interfere with cognitive processes and executive functioning 7 hampering parents' ability to make treatment decisions and provide emotional support to their children 1. For some, PTSS may develop into full or partial posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Partial PTSD is associated with comorbid psychiatric symptoms almost to the same extent as full PTSD 8.

Typically, studies of PTSS in parents of children diagnosed with cancer exclude bereaved parents. Even though survival rates have increased dramatically, around 20% of children in developed countries diagnosed with cancer will not survive the disease 9, 10. Caring for a terminally ill child and experiencing the death of one's child are among the most distressing human experiences 11. Besides grief, bereaved individuals may suffer from PTSS and PTSD 12. The prevalence of PTSD in populations who have lost a close relative to serious illness is 17–22% 1 to 6 months after the death 11, 13. No previous study has investigated PTSS and/or PTSD in parents of children lost to cancer.

The findings on level of PTSS and/or prevalence of PTSD in parents of children with cancer has been questioned because of small samples, high attrition, use of non‐robust measures, and too low or inclusive cut‐offs on measures of PTSS and/or PTSD to identify a clinically relevant level of PTSS and prevalence of potential PTSD 14, 15, 16. It has been argued that these limitations have resulted in overestimations of level of PTSS and/or prevalence of PTSD 15. Importantly, a lack of longitudinal studies has hampered the understanding of development of PTSS and prevalence of PTSD 14. This study was conducted to advance knowledge about the level of PTSS and the prevalence of PTSD among parents of children diagnosed with cancer. The study encompasses seven assessments from shortly (approximately 1 week) after diagnosis up to 5 years after end of treatment or death. A report 2 from the first three assessments showed that an initial high level of PTSS declined over the first months after diagnosis. One week to 4 months after diagnosis, partial PTSD was reported by 44–31% of mothers and 22–14% of fathers. This study investigates the development of PTSS in mothers and fathers of children diagnosed with cancer from shortly after diagnosis up to 5 years after end of treatment or child's death. Previous research has shown that mothers of children diagnosed with cancer report a higher level of PTSS than fathers 3, 17, 18. It has also been shown that there is not enough knowledge about the potential impact of child age and gender 14, 18, 19 and diagnosis 20 on parents' psychological sequelae. However, as survivors of central nervous system (CNS) tumors have a higher risk of long‐term morbidity 10, 21, and as there are reports indicating that parents of survivors of CNS tumors report heightened psychological distress 20, parental sequelae in relation to CNS tumors versus other diagnoses warrants further investigation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the very first study to report on the development of PTSS and the prevalence of full and/or partial PTSD in a cohort of mothers and fathers of children diagnosed with cancer from shortly after diagnosis up to long‐term survivorship or aftermath of a child's death.

Research questions were as follows:

What is the development of PTSS in parents of children diagnosed with cancer from shortly after diagnosis up to 5 years after end of treatment or child's death?

Is parents' level of PTSS shortly after diagnosis, age, and gender, as well as children's age, diagnosis (CNS tumor versus other diagnoses), gender, and vital status related to development of PTSS?

What is the prevalence of full and partial PTSD in mothers and fathers of survivors and bereaved mothers and fathers?

Does the prevalence of full and/or partial PTSD change over time for mothers and fathers of survivors and bereaved mothers and fathers?

Does the prevalence of full and/or partial PTSD differ between mothers of survivors and bereaved mothers and between fathers of survivors and bereaved fathers?

Methods

This study is part of a project investigating psychological and health economic consequences of being a parent of a child diagnosed with cancer. Data on health economic consequences are not reported in this paper. The project includes seven assessments (T1–T7). T1–T3 were administered in relation to the time of diagnosis: 1 week (T1), 2 (T2) and 4 months (T3) after diagnosis. T4–T7 were administered after end of treatment, stem cell/organ transplantation, or child's death. For parents whose child had completed treatment or transplantation data were collected: 1 week after treatment or 6 months after transplantation (T4), 3 months after treatment or 9 months after transplantation (T5), 1 year after treatment or 18 months after transplantation (T6), and 5 years after treatment or transplantation (T7). For bereaved parents, data were collected: 9 months (T5), 18 months (T6), and 5 years (T7) after the child's death. T4 data were not collected for bereaved parents.

T1 was set to capture experiences regarding diagnosis; T2–T3 experiences during treatment; and T4 experiences regarding end of treatment or transplantation. End of treatment is here defined as the time when the child has completed treatment at that time considered successful by the responsible pediatric oncologist. From discussions with pediatric oncologists, it was decided that 6 months after transplantation is the most equivalent time to end of treatment. For ethical reasons, the first assessment after a child's death was set to 9 months after death (T5). Data were on average collected the following number of days after diagnosis: 8 (SD = 2.2) (T1), 61 (SD = 5.9) (T2), and 119 (SD = 12.7) (T3); after treatment or transplantation: 13 (SD = 11.4) (T4); and after treatment or transplantation or child's death: 96 (SD = 14.5) (T5), 375 (SD = 18.5) (T6), and 2039 (SD = 65.6) (T7). End of treatment and transplantation are below referred to as end of treatment.

Participants

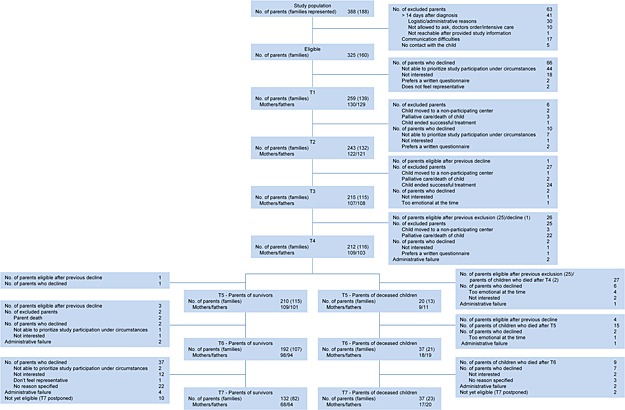

Parents of children diagnosed with cancer and treated at four of the six Swedish pediatric oncology centers (Gothenburg, Linköping, Umeå, and Uppsala) were consecutively recruited during 18 months from 2002 to 2004. Eligibility included the following: Swedish‐speaking and/or English‐speaking parents (including step‐parents) of children 0–18 years, diagnosed ≤14 days previously with a primary cancer diagnosis, and scheduled for chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Additionally, parents should have contact with the child, be considered by the responsible pediatric oncologist to be physically and emotionally capable of participating, and have access to a telephone. Eligibility at T2 and T3 included that the child was on curative treatment. Table 1 presents parent and child characteristics at T1. There were no differences regarding parent and child age between excluded parents and parents who declined participation (n = 129) versus participants (N = 259). However, parents of children with a CNS tumor were less likely to participate (χ 2 = 14.60, p = 0.001) than parents of children with other diagnoses. Most of the excluded parents were excluded because our research group was not able to approach them within 14 days after diagnosis. Two hundred fifty‐nine parents, representing 139 families, participated at T1 (80% response rate). No differences were found between those who participated at T7 (n = 169) versus those who did not (n = 90) regarding level of PTSS, age, gender, civil status, or child diagnosis (CNS tumor versus other diagnoses) at T1. However, non‐participants at T7 had a lower educational level (χ 2 = 10.80, p = 0.005) at T1, and more non‐participants than participants at T7 had no other child than the child diagnosed with cancer at T1 (χ 2 = 8.60, p = 0.014). Educational level and number of children were not related to level of PTSS at any assessment. See Figure 1 for a presentation of study enrollment. Parents of children who at the respective assessment at T4–T7 were considered successfully treated by the responsible pediatric oncologist are subsequently referred to as parents of survivors. Fifty‐four parents ended up bereaved. At T7, 132 parents of survivors (82 families) and 37 bereaved parents (23 families) participated. The retention rate from T1 to T7 was 65%, 64% among parents of survivors and 69% among bereaved parents.

Table 1.

Parent (N = 259) and child (N = 139) characteristics at T1

| Parent characteristics | n (Parents/children) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mother/father | 130/129 | 50.2/49.8 |

| Parent of daughter/son | 120/139 | 46.3/53.7 |

| Civil status | ||

| Spouse/partner | 240 | 92.7 |

| Single | 19 | 7.3 |

| Education | ||

| Basic (≤9 years) | 37 | 14.3 |

| Secondary | 135 | 52.1 |

| Post secondary (>14 years) | 81 | 31.3 |

| Not stated | 6 | 2.3 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 30 | 11.6 |

| 30–39 | 133 | 51.4 |

| ≥40 | 96 | 37.1 |

| Child characteristics | ||

| Number of siblings | ||

| 0 | 13 | 9.4 |

| 1–2 | 103 | 74.1 |

| ≥3 | 23 | 16.5 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 0–3 | 41 | 29.5 |

| 4–7 | 36 | 25.9 |

| 8–12 | 34 | 24.5 |

| 13–18 | 28 | 20.1 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Leukemia/lymphoma | 79 | 56.8 |

| Central nervous system tumor | 16 | 11.5 |

| Bone tumor | 13 | 9.4 |

| Other solid tumor | 31 | 22.3 |

| Transplantation | ||

| Yes | 18 | 12.9 |

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart. Exclusion at T1 because of communication difficulties include not Swedish/English‐speaking and having hearing deficits

Measures

Medical data and data about parents' age, gender, and educational level and child age and gender were collected at T1, whereas data on number of siblings and parents' civil status were collected at all assessments. The PTSD Checklist Civilian Version (PCL‐C) 22 was used to assess the level of PTSS and prevalence of PTSD at all assessments. PCL‐C has been used in similar populations such as parents of children admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit and parents of children with acute burns 23, 24. It contains 17 items corresponding to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV) 25 PTSD symptom clusters: re‐experiencing (items 1–5), avoidance/numbing (6–12), and hyper‐arousal (13–17). Items are scored from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘extremely’ (5) and were in this study keyed to the child's cancer disease. PCL‐C has demonstrated robust psychometric properties with adequate internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity 25.

The mean level of PTSS was assessed on a continuum. Full PTSD was assessed by the symptom criteria method: a score of ≥3 on at least one symptom of re‐experiencing, three symptoms of avoidance, and two symptoms of hyper‐arousal 22. The method corresponds to the DSM‐IV criteria 26, is the most rigorous self‐assessment of PTSD, and has shown a sensitivity of 1.00, a specificity of 0.92, and a diagnostic effectiveness of 0.92 compared with that of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders in mothers of childhood cancer survivors 27. Partial PTSD was assessed by a score of ≥3 on at least one symptom of re‐experiencing, avoidance, and hyper‐arousal 28.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committees at the respective faculties of medicine. Potential participants were approached by a coordinating nurse who provided written and oral information about the study and collected oral informed consent. A research assistant administered the PCL‐C via telephone.

Statistical analyses

Latent growth curve (LGC) modeling was used to identify development of PTSS and to estimate the potential effect of covariates on this development (research questions [RQ] 1 and 2) 29. The LGC analyses were conducted in Mplus 6.1 30 using the COMPLEX command and the MLR‐estimator (Mplus option for maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors) to correct standard errors due to parent dyads nested in children. Missing data are handled in Mplus using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) under the assumption of missing at random (MAR) 31. Analyses were performed in a hierarchy of increasing complexity and selection of the final model was based on model fit. Overall model fit was analyzed using the Steiger–Lind root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the Bentler comparative fit index (CFI). RMSEA values <0.05 indicate good fit and values between 0.08 and 0.10 moderate fit, while CFI values >0.90 indicate acceptable fit, and values close to 0.95 indicate good fit 32, 33. The child's vital status was included as a time‐varying covariate at T5–T7. Gender, age, and diagnosis (CNS tumor versus other diagnoses) were included as time‐invariant covariates of initial level of PTSS and change over time. Significant covariates were included in the final model. Time scores were set to represent mean time since diagnosis and end of treatment or child's death.

Research question 3 was answered with descriptive statistics. Change with regard to the prevalence of full and partial PTSD for mothers and fathers of survivors and bereaved mothers and fathers was examined with McNemar tests (RQ 4). Chi‐squared tests were performed to determine if the prevalence of full and partial PTSD differed between mothers of survivors and bereaved mothers and between fathers of survivors and bereaved fathers (RQ 5). SPSS Statistics Version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to answer RQs 3–5. Two‐tailed testing and an alpha level of 0.05 was used.

Results

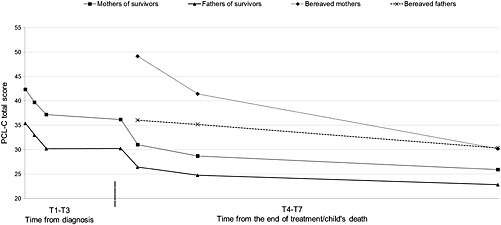

Figure 2 shows the development of PTSS from T1 to T7. The final LGC model is a conditional piecewise LGC model 34 allowing separate growth at T1–T4 and T4–T7; see Supporting Information for model details. The final model fits the data well (RMSEA = 0.043, 90% Confidence interval [CI] = 0.013–0.066; CFI = 0.98), and showed a linear and quadratic development between T1 and T4 and no decline between T4 and T7, confirming an initial decline in PTSS that abated over time. The final model includes a free intercept factor loading at T4, suggesting that the level of PTSS at T4 deviated from the overall estimated growth (Est = 4.65; p < 0.001). With the free intercept at T4 included in the model, the growth factor for T4–T7 was non‐significant, implying that the non‐significant change occurred from T5.

Figure 2.

Observed means of level of posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents (N = 259) from shortly after diagnosis up to 5 years after end of treatment/child's death. Dashed line indicates time for end of treatment

Mothers reported a higher initial level of PTSS than fathers (Est = 6.82; p < 0.001). Parent gender did not predict change in PTSS; mothers continued to report a higher level than fathers. A higher initial level of PTSS was related to a greater decline between T4 and T7 (Est = −1.38, p = 0.008). Having a girl was related to a higher initial level (p < 0.05) and a greater decline between T1 and T4 (p < 0.05). Parent age and child age and diagnosis (CNS tumor versus other diagnoses) did not predict initial level or development of PTSS. Finally, bereaved parents reported a higher level of PTSS at T5–T7 than parents of survivors.

The prevalence of full and partial PTSD for mothers and fathers of survivors at T4–T7 and bereaved mothers and fathers at T5–T7 is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Level of PTSS and prevalence of full and partial PTSD for mothers and fathers of survivors and bereaved mothers and fathers as well as comparisons of prevalence of full/partial PTSD between mothers of survivors and bereaved mothers, and between fathers of survivors and bereaved fathers

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers of survivors | Bereaved mothers | χ 2 | Fathers of survivors | Bereaved fathers | χ 2 | |

| T4 | ||||||

| PTSS, mean (SD) | 36.2 (14.7) | NA | NA | 30.2 (10.2) | NA | NA |

| Full PTSD, n (%) | 30/109 (27.5) | NA | NA | 15/103 (14.6) | NA | NA |

| Partial PTSD, n (%) | 49/109 (45.0) | NA | NA | 33/103 (32.0) | NA | NA |

| T5 | ||||||

| PTSS, mean (SD) | 31.0 (12.4) | 49.1 (8.74) | NA | 26.5 (8.6) | 36.0 (7.6) | NA |

| Full PTSD, n (%) | 16/109 (14.7) | 6/9 (66.7) | 14.81** | 6/101 (5.9) | 2/11 (18.2) | 2.24 |

| Partial PTSD, n (%) | 32/109 (29.4) | 8/9 (88.9) | 13.15** | 16/101 (15.8) | 6/11 (54.5) | 9.41** |

| T6 | ||||||

| PTSS, mean (SD) | 28.7 (12.2) | 41.4 (13.9) | NA | 24.8 (8.9) | 35.2 (11.7) | NA |

| Full PTSD, n (%) | 10/98 (10.2) | 9/18 (50.0) | 17.58*** | 6/94 (6.4) | 5/19 (26.3) | 7.15* |

| Partial PTSD, n (%) | 16/98 (16.3) | 11/18 (61.1) | 17.08*** | 14/94 (14.9) | 8/19 (42.1) | 7.46* |

| T7 | ||||||

| PTSS, mean (SD) | 25.9 (9.9) | 30.2 (13.5) | NA | 22.8 (7.0) | 30.4 (10.1) | NA |

| Full PTSD, n (%) | 7/68 (10.3) | 2/20 (10.0) | 0.01 | 1/64 (1.6) | 3/17 (17.6) | 7.40* |

| Partial PTSD, n (%) | 13/68 (19.1) | 4/20 (20.0) | 0.04 | 5/64 (7.8) | 6/17 (35.3) | 8.64** |

PTSS, posttraumatic stress symptoms; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SD, standard deviation; NA, not applicable.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < .0001 Statistical significant difference by chi‐square tests.

Among parents of survivors, there was a decline from T4 to T5 in prevalence of full and partial PTSD for mothers (p = 0.0005), and a decline in prevalence of partial PTSD for fathers (p = 0.002). After T5, no decline occurred for parents of survivors besides for partial PTSD from T5 to T6 (p = 0.031) for mothers. Among bereaved parents, there was a decline for mothers of full and partial PTSD between T6 and T7 (p = 0.008).

A larger proportion of bereaved mothers than mothers of survivors reported full and partial PTSD at T5 and T6, but not at T7 (Table 2). A larger proportion of bereaved fathers than fathers of survivors reported partial PTSD at T5, and full and partial PTSD at T6 and T7.

Discussion

This study is unique in its kind as it describes the development of PTSS in parents of children diagnosed with cancer from shortly after diagnosis up to 5 years after end of treatment or the child's death. An initial high level of PTSS decreased with time from diagnosis, but the decline abated, and from 3 months after end of treatment, only a minimal decline occurred. The same pattern was found regarding PTSD with a relatively stable prevalence from 3 months after end of treatment. Five years after end of treatment, 19% of mothers and 8% of fathers of survivors reported at least partial PTSD. Corresponding figures for bereaved parents were 20% for mothers and 35% for fathers. Mothers and bereaved parents were at particular risk for PTSS and PTSD. There was no relationship between parent age, child age, or diagnosis and level of PTSS.

In line with previous results 5, mothers reported a higher level of PTSS than fathers, and this holds true for the child's full disease trajectory. Five years after end of treatment, 10% of mothers and 2% of fathers reported full PTSD. The finding indicates an increased risk of PTSD in Swedish mothers of survivors of childhood cancer, compared with that of the general Swedish population with a lifetime PTSD prevalence of 6% 35.

The initial level of PTSS predicted development of PTSS, however, only for the period after end of treatment, which shows that parents reporting a high level of PTSS shortly after diagnosis are at risk of a high level of PTSS during the entire treatment period. The time directly after end of treatment deviated from the overall estimated growth curve with a higher level of PTSS. This shows that the period following end of treatment is challenging for parents, supporting results by others 36.

Bereavement was associated with a high level of PTSS and risk of PTSD. Eighteen months after a child's death, 67% of mothers and 18% of fathers reported full PTSD, and 5 years after a child's death, 10% of mothers and 18% of fathers reported full PTSD. Compared with that of the general population 35, and other bereaved populations 11, 13, the figures are high, signifying the traumatic implications of losing a child to cancer. Furthermore, the prevalence of PTSD decreased among mothers, but not among fathers. The high prevalence of PTSD in bereaved parents is important to acknowledge in the clinical care of families who have lost a child to cancer.

The PTSD prevalence among parents of survivors is in the lower range compared with previous reports for the population 5. This is possibly due to a psychometrically robust assessment and a conservative scoring method supporting previous critique of overestimations of level of PTSS and prevalence of PTSD in parents of children diagnosed with cancer 15. Measuring prevalence of PTSD in populations exposed to serious illness has been questioned 14, 16, 37, and the recent version of the DSM (DSM‐5) 38 does not include having a child with a serious illness as a potentially traumatic event. In the DSM‐5, adjustment disorders (AD) is instead put forth as the major psychological response to a medical illness 38, and AD has been suggested for individuals meeting the criteria for partial PTSD 37. In line with this, parents who reported at least partial PTSD should be considered as potential cases for an AD diagnosis. Regardless of conceptual ambiguities, findings show that parents of children diagnosed with cancer report PTSS, and whether addressed as PTSD or AD, the symptoms need to be recognized in the clinical care of families struck by childhood cancer.

Some study limitations should be considered. First, assessing prevalence of PTSD by self‐reports without confirmation by a structured diagnostic interview should be noted. However, the PCL‐C has shown high diagnostic effectiveness in the population when using the symptom criteria method 27. Second, although the number of participants is high for the population and type of research, there might be a power issue precluding detection of a decline in level of PTSS between T5 and T7. And, the low number of bereaved parents hampers firm conclusions regarding this subgroup. Finally, attrition may raise concerns about response bias. However, a retention rate of 65% is high for a study with seven assessments over a period of 12 years, and importantly, no difference was found for initial level of PTSS between parents participating, and parents lost to attrition, at the last assessment. Moreover, the variables related to non‐participation (parent education and siblings) were not related to level of PTSS at any assessment. Missing data are therefore assumed to not have an impact on findings.

To conclude, when operationalized in terms of PTSS, the answer to the question if time heals all wounds for parents of children diagnosed with cancer is ‘yes’ for most parents. However, mothers and bereaved parents are at risk for PTSS and PTSD. The time directly after end of treatment is a period of vulnerability, which should be recognized in the clinical care of families struck by childhood cancer. In Sweden, the psychological services offered to the population differ between childhood cancer centers. Furthermore, these services are often only available during the treatment period. The findings underscore the need to establish national guidelines for provision of psychological support to the subgroups of parents of children diagnosed with cancer who need such support even years after end of treatment or a child's death.

Supporting information

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Ljungman, L. , Hovén, E. , Ljungman, G. , Cernvall, M. , and von Essen, L. (2015) Does time heal all wounds? A longitudinal study of the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of survivors of childhood cancer and bereaved parents. Psycho‐Oncology, 24: 1792–1798. doi: 10.1002/pon.3856.

References

- 1. Dunn MJ, Rodriguez EM, Barnwell AS et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of children with cancer within six months of diagnosis. Health Psychol 2012;31:176–185. DOI:10.1037/a0025545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pöder U, Ljungman G, von Essen L. Posttraumatic stress disorder among parents of children on cancer treatment: a longitudinal study. Psycho‐Oncology 2008;17:430–437. DOI:10.1002/pon.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kazak AE, Boeving CA, Alderfer MA, Hwang WT, Reilly A. Posttraumatic stress symptoms during treatment in parents of children with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7405–7410. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2005.09.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ljungman L, Cernvall M, Grönqvist H, Ljòtsson B, Ljungman G, von Essen L. Long‐term positive and negative psychological late effects for parents of childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9e103340. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0103340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruce M. A systematic and conceptual review of posttraumatic stress in childhood cancer survivors and their parents. Clin Psychol Rev 2006;26:233–256. DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brunello N, Davidson JR, Deahl M et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder: diagnosis and epidemiology, comorbidity and social consequences, biology and treatment. Neuropsychobiology 2001;43:150–162. DOI:10.1159/000054884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leskin LP, White PM. Attentional networks reveal executive function deficits in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychology 2007;21:275–284. DOI:10.1037/0894-4105.21.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Anxiety Disord 2011;25:456–465. DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gustafsson G, Kogner P, Heyman M. Childhood Cancer Incidence and Survival in Sweden 1984–2010. Report from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry. Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ward E, DeSanitis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:83–103. DOI:10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kristensen TE, Elklit A, Karstoft KI, Palic S. Predicting chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in bereaved relatives: a 6‐month follow‐up study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014;31:390–405. DOI:10.1177/1049909113490066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zisook S, Chentsova‐Dutton Y, Shuchter SR. PTSD following bereavement. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1998;10:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elklit A, O'Connor M. Post‐traumatic stress disorder in a Danish population of elderly bereaved. Scand J Psychol 2005;46:439–445. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2005.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phipps S, Long A, Hudson M, Rai SN. Symptoms of post‐traumatic stress in children with cancer and their parents: effects of informant and time from diagnosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2005;45:952–959. DOI:10.1002/pbc.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phipps S, Klosky JL, Long A et al. Posttraumatic stress and psychological growth in children with cancer: has the traumatic impact of cancer been overestimated? J Clin Oncol 2014;32:641–646. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.8212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jurbergs N, Long A, Ticona L, Phipps S. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in parents of children with cancer: are they elevated relative to parents of healthy children? J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:4–13. DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vrijmoet‐Wiersma CM, van Klink JM, Kolk AM, Koopman HM, Ball LM, Maarten ER. Assessment of parental psychological stress in pediatric cancer: a review. J Pediatr Psychol 2008;33:694–706. DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsn007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pai AL, Greenley RN, Lewandowski A, Drotar D, Youngstrom E, Peterson CC. A meta‐analytic review of the influence of pediatric cancer on parent and family functioning. J Fam Psychol 2007;21:407–415. DOI:10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leventhal‐Belfer L, Bakker A, Russo C. Parents of childhood cancer survivors: a descriptive look at their concerns and needs. J Psychosoc Oncol 1993;11:19–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hovén E, Anclair M, Samuelsson U, Kogner P, Boman KK. The influence of pediatric cancer diagnosis and illness complication factors on parental distress. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2008;30:807–814. DOI:10.1097/MPH.0b013e31818a9553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y et al. Health status of adult long‐term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 2003;290:1583–1592. DOI:10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the 9th Annual Conference of the ISTSS, San Antonio, TX, 1993.

- 23. Balluffi A, Kassam‐Adams N, Kazak A, Tucker M, Dominguez T, Helfaer M. Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2004;5:547–553. DOI: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000137354.19807.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hall E, Saxe G, Stoddard F et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of children with acute burns. J Pediatr Psychol 2006;31:403–412. DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsj016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist‐Civilian Version. J Trauma Stress 2003;16:495–502. DOI:10.1023/A:1025714729117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th ed, American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Manne SL, Du Hamel K, Gallelli K, Sorgen K, Redd WH. Posttraumatic stress disorder among mothers of pediatric cancer survivors: diagnosis, comorbidity, and utility of the PTSD checklist as a screening instrument. J Pediatr Psychol 1998;23:357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stein MB, Walker JR, Hazen AL, Forde DR. Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. Am J Psychiatry 1997;154:1114–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: concepts, issues, and applications In Quantitative Methodology Series 2nd ed. Marcoulides GA. (ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associate: Mahwah, New Jersey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide 6th ed, Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum‐likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychol Methods 2001;6:352–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull 1990;107:238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification—an interval estimation approach. Multivar Behav Res 1990;25:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flora D. Specifying piecewise latent trajectory models for longitudinal data. Struct Equ Modeling 2008;15:513–533. DOI:10.1080/10705510802154349. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Frans O, Rimmo PA, Aberg L, Fredrikson M. Trauma exposure and post‐traumatic stress disorder in the general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;111:291–299. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wakefield CE, McLoone JK, Butow P, Lenthen K, Cohn RJ. Parental adjustment to the completion of their child's cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;56:524–531. DOI:10.1002/pbc.22725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kangas M. DSM‐5 trauma and stress‐related disorders: implications for screening for cancer‐related stress. Front Psychiatry 2013;4:1–3. DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.), American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item