Abstract

Objective

In this paper we synthesize the evidence from eye tracking research in tobacco control to inform tobacco regulatory strategies and tobacco communication campaigns.

Methods

We systematically searched 11 databases for studies that reported eye tracking outcomes in regards to tobacco regulation and communication. Two coders independently reviewed studies for inclusion and abstracted study characteristics and findings.

Results

Eighteen studies met full criteria for inclusion. Eye tracking studies on health warnings consistently showed these warnings often were ignored, though eye tracking demonstrated that novel warnings, graphic warnings, and plain packaging can increase attention toward warnings. Eye tracking also revealed that greater visual attention to warnings on advertisements and packages consistently was associated with cognitive processing as measured by warning recall.

Conclusions

Eye tracking is a valid indicator of attention, cognitive processing, and memory. The use of this technology in tobacco control research complements existing methods in tobacco regulatory and communication science; it also can be used to examine the effects of health warnings and other tobacco product communications on consumer behavior in experimental settings prior to the implementation of novel health communication policies. However, the utility of eye tracking will be enhanced by the standardization of methodology and reporting metrics.

Keywords: tobacco, smoking, eye tracking, health warnings, plain packaging, advertising, health communication

Effective tobacco control requires a comprehensive strategy that includes limiting the impact of tobacco industry advertising,1 persistent anti-tobacco promotion through the use of mass media communication campaigns, excise tax measures, clean air legislation, smoking cessation, and tobacco regulatory measures, such as enhanced warning labels on tobacco product packaging and advertising.2 Due to misleading tobacco product packaging3,4 or exposure to pro-tobacco advertising and point-of-sale promotion,5,6 tobacco users are often unaware or misinformed about risks associated with product use.3 To combat this, developing salient and informative tobacco control communication campaigns and regulatory strategies (eg, health warnings) and understanding the role of labeling and marketing on consumer perceptions of tobacco products are research priorities of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products (CTP).7 In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), a treaty representing nearly the entire world's population, also informs regulatory strategies related to tobacco product packaging and labeling (eg, best practices for developing effective health warnings and adopting packaging restrictions such as plain packaging)8 and emphasizes the role of communication to change tobacco-related attitudes and behavior.9

Much of the current evidence about the relative effectiveness of tobacco regulatory and communication strategies, such as plain packaging, warning labels, and anti-tobacco advertising, is derived from surveys and focus group research.10,11 Though such study designs are informative, measures of attention and cognitive processing such as post hoc recall can be biased,12 and therefore, researchers in tobacco control have called for more experimental studies, such as those utilizing eye tracking, to provide quantifiable data that can complement existing evidence and enhance effectiveness of tobacco control strategies.13

Eye tracking has several unique capabilities that make it complimentary to evidence from other methods in tobacco regulatory science and communication. Eye tracking is a direct measure of attention, which is an essential precursor to information processing, recall, and other endpoints important for regulatory science.14 The direct measures provided by eye tracking are more detailed and less prone to bias than those collected by verbal report.15 Additionally, eye tracking can be used as a tool to determine which elements of visual information increase effectiveness in conveying health information – findings that can have policy implications across health communication fields.15 For instance, eye tracking research on nutritional labels informed recommendations for policymakers to improve consumer attention to and use of nutrition labels.16

A unique strength of eye tracking methodology is that it offers insight at a psychophysiological level, providing a direct and valid measure of information acquisition amenable to experimental manipulation.17,18 Eye movements consist of 2 distinct components that reflect attention to a particular scene, both of which can be recorded by eye tracking technology, saccades and fixations. Saccades are moments of rapid eye movements occurring between fixations, generally lasting about 20-40 milliseconds whereby specific locations of a scene are projected, but not processed, onto the eye; roughly 170,000 saccades are made by humans every day.12 Fixations, on the other hand, are periods during which the eye is relatively still; such periods last about 200-500 milliseconds and serve to project a greater area of the scene onto the eye for visual processing.12 The total time fixating on an area of interest often is reported as dwell time. The pattern of saccades (ie, eye movements between fixations) and fixations observed shows how a person viewed a scene – of particular interest for tobacco communication and regulation to determine how effectively components of advertising or product packaging attract attention and how that attention is held over time.

Increasing technological advances have paved the way for more naturalistic and inexpensive recordings of eye movements (eg, participants no longer need to wear obtrusive headgear to track their eyes), thereby driving the rapid growth of its use in research across a broad array of fields, such as marketing, theory development, and academics, including tobacco regulatory science.12,18 This technology is an efficient tool to assess the effects of visual communication because attention is critical for the information reception process19 that informs subsequent decision making.20 Marketing research, for instance, has used fixation data from eye tracking to understand downstream effects on consumers (eg, memory, preference, sales choice) in relation to point-of-sale, print and television advertising, labeling, and branding of products,12 all of which are relevant to tobacco control regulation and communication. The tobacco industry also has utilized eye tracking technology to improve its marketing practices, including examining how consumers attend to print advertisements for cigarettes21 and how point-of-sale marketing is impacted by where consumers look while making purchases.22

The use of eye tracking technology across a broad array of communications research relevant to tobacco regulatory science is growing. However, to date, the existing evidence generated from eye tracking technology in tobacco regulatory science and communication has not been comprehensively examined. To improve the ability of public health professionals to utilize and assess all available evidence when developing regulatory strategies and communication campaigns, this systematic review synthesizes the evidence from eye tracking research studies in tobacco control regulation and communication. This systematic review also examines gaps in tobacco communication and regulatory science that are amenable to investigation with eye tracking methodologies.

Methods

Search Strategy

We searched 11 databases for peer-reviewed and grey literature (eg, dissertations and publicly available reports): PubMed, CINAHL via EBSCO, EMBASE via embase.com, Dissertations & Theses Global via Proquest, COCHRANE, PsychInfo via EBSCO, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Business Source Premier, Communication and Mass Media Complete, and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). Grey literature also was included to capture all available data, as the use of eye tracking in tobacco regulatory science is relatively limited. We developed a search strategy (Supplemental Table S1) in consultation with a university health sciences librarian to identify literature that contained: (1) eye tracking terms (eg, eye movement, fixation); and (2) tobacco-related terms (eg, cigarette) or health communication terms (eg, health warning). For more details, refer to Supplemental Tables S1-S3. We restricted results to English language but did not use date or geographical limitations in our search. Non-peer reviewed literature was eligible for inclusion, and is noted when presented. The search was first conducted in fall 2015, and we updated our search in March 2016 to include more recently published literature. Upon removing duplicates, the search produced 4915 records for review.

Study Selection

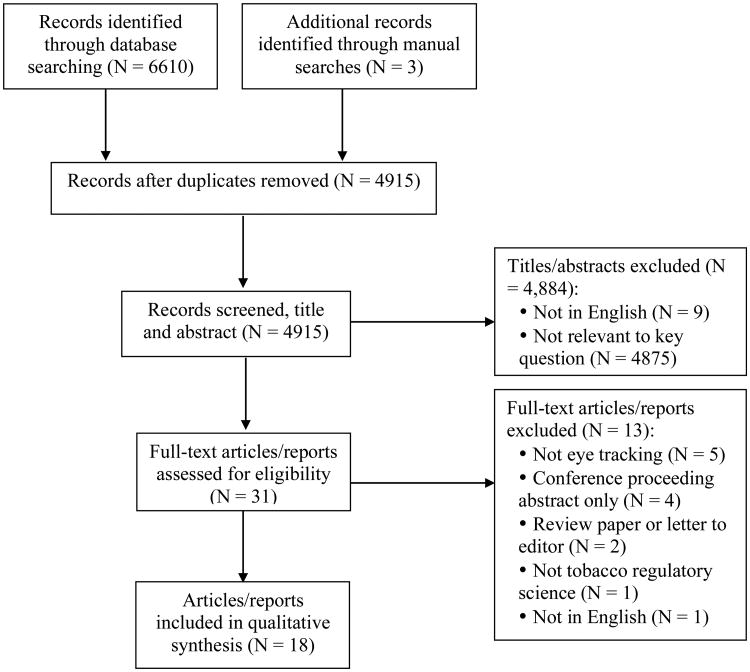

Two coders (KJ, CM) independently reviewed each record the search produced during a title and abstract review phase, and then reviewed all relevant articles during a full text review. We only included studies reporting eye tracking outcomes in regards to tobacco communication, such as tobacco packaging, warnings, advertisements, health campaigns, or point-of-sale (Figure 1). Studies examining the effects of nicotine on eye movement or attentional bias toward smoking cues were excluded because they represent their own distinct bodies of research and were not within the scope of our review. Divergent coding of studies between the 2 coders was resolved with discussion. All references of final included articles were hand-searched to identify additional relevant records for review.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Screening and Inclusion.

Data Extraction

Two authors (KJ, CM) independently read and coded the same 3 included articles and met to ensure consistent coding. Then, for all other articles, one author extracted information into a database to categorize each study design, sample recruitment and characteristics, eye tracking methodology, outcome measures, analytical methods, and results. Each article was coded by topic area of tobacco regulatory science, which included tobacco packaging, warnings, point-of-sale, advertising, and other communication.

Quality Assessment

We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration's risk of bias tool.23 Rather than using a scale or score system, the tool is based on critical assessment of different domains of bias appropriate to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs): (1) random sequence generation; (2) allocation concealment; (3) blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors; (4) incomplete outcome data; (5) selective outcome reporting; and 6) other sources of bias, such as industry funding. Though our included studies are not typical RCTs, most studies utilized experimental designs that randomly assigned participants to conditions and then assessed differences across those conditions, similar to an RCT. We assessed external validity, or generalizability, through study sample size, population (inclusion/exclusion criteria), and recruitment methods. Two authors (KJ, CM) coded 3 of the same articles and met to ensure consistency in quality assessment.

Results

Description of Studies

Eighteen eye tracking studies met criteria for inclusion14,24-40 (Table 1). Most (N = 14) were published in the past 6 years14,28-40 and the study locations varied between US14,24-26,28,29,37,40 and non-US27,30-36,38,39 venues. All studies utilized convenience sampling with sample sizes ranging from 22 to more than 300. Most studies either included only tobacco users14,29,31,35,37,38 (N = 6) or included both users and non-users24,25,27,30,32-34,39,40 (N = 9). The stimuli in most studies14,24-39 (N = 17) were static print images shown to participants via a computer screen, projector, or physical print copies. Six studies collected survey measures (eg, masked recall of warning message, perceived risk of smoking related disease) and statistically related them to eye tracking measures (eg, examining the association between recall of the package warning and dwell time on the warning).14,24,25,27,29,32 Given the overlap between each aspect of communication that was coded, we grouped the eye tracking studies into 4 topic areas: (1) health warnings in tobacco advertising; (2) tobacco product packaging, including plain packaging and warnings that appear on packages; (3) general tobacco communication; and (4) point-of-sale. Supplemental Tables S2 and S3 provide detailed characteristics and findings of each study.

Table 1. Summary of Included Studies (N = 18).

| Characteristic | % (N) | |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 1980s | 6% (1) |

| 1990s | 11% (2) | |

| 2000s | 6% (1) | |

| 2010-2016 | 78% (14) | |

|

| ||

| Study sample size | 22 (min) - 35 | 28% (5) |

| 36 - 60 | 28% (5) | |

| 61 - 99 | 17% (3) | |

| 100 - 199 | 11% (2) | |

| 200 – 326 (max) | 17% (3) | |

|

| ||

| Sample type | Convenience | 100% (18) |

| Probability | 0% (0) | |

|

| ||

| Area of tobacco controla | Packaging | 38% (7) |

| Warning | 94% (17) | |

| Point of sale | 6% (1) | |

| Advertising | 50% (9) | |

| Other communication | 17% (3) | |

|

| ||

| Location of study | US | 44% (8) |

| UK | 22% (4) | |

| Europe (Germany =1, Netherlands = 1, Hungary =1, Romania = 1, Spain = 1) | 28% (5) | |

| Taiwan | 6% (1) | |

|

| ||

| Tobacco use status of sample | Tobacco users | 33% (6) |

| Non tobacco users | 6% (1) | |

| Both tobacco and non-tobacco users | 50% (9) | |

| Not reported | 11% (2) | |

|

| ||

| Study design | Within | 22% (4) |

| Between | 33% (6) | |

| Within and between | 39% (7) | |

| Neither | 6% (1) | |

|

| ||

| Stimulus | Static or print image | 94% (17) |

| Dynamic or video image | 6% (1) | |

|

| ||

| Outcomes reported | Only eye tracking measures | 67% (12) |

| Survey measures related to eye tracking | 33% (6) | |

Note.

= Categories not exclusive

Health Warnings in Tobacco Advertising

Seven eye tracking studies investigated health warnings in the context of tobacco advertisements.14,24-29 The eye tracking studies examining health warnings had sample sizes ranging from 32 to 326 participants. Whereas one was observational,24 the others manipulated between and/or within subjects' factors.14,25-29

To our knowledge, the first study using eye tracking within tobacco regulatory and communication research was published in 1989. Fischer et al presented adolescents with 5 tobacco advertisements from magazines, which included 4 cigarette advertisements and one chewing tobacco advertisement, each with text warnings.24 Less than 10% of the total advertisement viewing time was spent on the warning, and in 44% of the cases participants did not look at the warning at all. Participants who looked at the warning longer had significantly higher masked recall of the warning.

Krugman et al also investigated attention to health warnings by manipulating text warnings in magazine advertisements for Marlboro and Camel cigarettes and assigning adolescent participants to either new or existing text warnings.25 Focus groups comprised of adolescents were used to develop new text warnings that were found to be more personal and informative to this demographic; warnings were designed specifically to increase attention towards them (ie, the Marlboro ad contained a new warning with a yellow background and the Camel ad contained a new warning with stylized font and red color). For both the Marlboro and Camel ads, the percent of participants fixating on the warning was higher for new, unfamiliar warnings as compared to existing text warnings, and those attending to the warnings fixated more quickly on the new warnings than the existing warnings. Again, masked recall of the new text warnings was positively associated with dwell time and number of fixations on the warning.

A later study by Fox26 used a subset of the data reported by Krugman et al25 and compared attention to cigarette advertisements (Camel and Marlboro) to other product type advertisements, including Miller Lite and Diet Coke. Significant differences in dwell time on ads were observed, with the Camel advertisement attracting the most attention. Additionally, more participants attended to the text warning on the Marlboro advertisement (86%) than the Camel advertisement (78%) and warning dwell time was also higher for the Marlboro advertisement (2.5 seconds) than the Camel advertisement (2 seconds). The difference in dwell time between the Marlboro and Camel ads may have resulted from a higher contrast between the white text box containing the warning on the Marlboro ad (set against a black background), compared to the lack of contrast between the white warning text box and the white background the warning was set against on the Camel ad.

Similar to Krugman et al,25 investigators in Spain randomized young adults to one of 3 versions of an advertisement for a popular Spanish cigarette brand to examine how attention to text warnings is impacted by familiarity.27 One version was the original advertisement that included the general warning message proposed by Spanish health authorities. The 2 others contained similarly sized novel text warning messages in the same format as the existing warning. These warnings were considered to be novel because they were modifications to the existing warning and were not used in Spain at the time of the study. In contrast to Krugman et al, which used color and stylized font within its new text warnings,25 visual attention to the warnings was similar among existing and novel warnings for both smokers and non-smokers. Overall, 7.6% of participants did not look at the warning area. Participants with better recall of the warning message took slightly longer to fixate at first on the warning area, but had more fixations and longer dwell time on the warning area than participants that could not recall the warning.

Rather than manipulating text-only warnings on tobacco advertisements, Peterson et al28 varied warnings between standard Surgeon General text warnings and Canadian graphic warnings. They found similar dwell times and fixations on advertisements as a whole regardless of warning type, but higher fixations occurred on graphic warnings compared to text warnings within those advertisements.

An additional tobacco control study examined graphic versus text-only warning labels on cigarette advertisements among daily adult smokers, but with a much larger sample size.29 Similar to findings from Peterson et al,28 participants viewed the warning area in the graphic condition for a significantly greater duration than in the text condition; participants in the graphic condition also viewed the graphic warning more quickly than participants in the text condition viewed the text warning. In the graphic label condition, shorter time to first fixation on the warning and longer dwell time on the graphic image were associated with correct recall of the warning, though this association was not seen among participants in the text condition.

A similar study by Klein et al,14 which included a larger graphic warning condition, found that adult smokers spent less time looking at the text-only warning compared to both the standard and larger graphic warning, consistent with findings from other included studies.28,29 Participants were more likely to fixate first on the health warning in the graphic warning conditions compared to the text warning condition. The odds of recall of the warning label were higher in the graphic warning condition, and dwell time on the warning mediated 33% of the effect of the graphic condition on warning recall.

Collectively, these eye tracking studies suggest that: (1) viewing time of the warning label is an important predictor of recall;14,24,25,27,29 (2) graphic warnings increase attention compared to text-only warnings;14,28,29 and (3) simply placing new, unfamiliar text warnings on advertisements may not increase attention toward the warnings,22 though new text warnings presented in a different format than existing text warnings (eg, added color, stylized font) may be more effective.20

Tobacco Product Packaging, Including Plain Packaging and Package Warnings

Seven eye tracking studies examined tobacco product packaging, including plain packaging and health warnings that appear on tobacco packages.30-36 Kessels et al30 experimentally manipulated the text (high-risk or coping) and photo (low or high threat) in a tobacco health warning, among both smokers and non-smokers and found that smokers and non-smokers attended to warnings in different patterns. Although smokers had more fixations and dwell time on warnings with coping text, non-smokers had more fixations and dwell time on high-risk information. Photos depicting low threat with high-risk text received significantly more fixations and dwell time than photos depicting low threat with coping text.

In a similar manner, Sussenbach et al32 varied pack warning type (text vs graphic) between subjects and threat level (aversive or non-aversive) within subjects, recruiting smokers and non-smokers to view images of 15 cigarette packages. Eye tracking data were collected only for participants who viewed the graphic warnings (ie, combined textual and pictorial warning) and showed that smokers spent more time looking at the graphic information within the warning than at the textual information within the warning; the difference in viewing time between the graphic and the text was larger for the packages with aversive warnings compared to the non- aversive. The investigators also found that smokers with longer dwell times on the textual information within the warning, compared to smokers with less attention to the textual information, reported an increase in perceived risk of smoking related diseases for themselves and others.

In an investigation on the effects of plain packaging, Munafo et al33 showed smokers and non-smokers 10 branded and 10 plain cigarette pack images with pictorial health warnings used in the United Kingdom (UK). On branded packs, non-smokers and weekly smokers exhibited a similar number of saccades, or eye movements, towards health warnings and brand, but on plain packs, they showed greater eye movements towards health warnings and fewer toward brand. In contrast, this pattern was not observed among daily smokers.

Maynard et al, 201334 showed never smokers, experimenters, weekly smokers, and daily smokers 20 images each of cigarette packages, comparing attention to health warnings on branded and plain packaging. Findings showed that smoking status was an important factor in predicting dwell time and eye movements towards the warning on different packaging. Experimenters and weekly smokers showed more attention to warnings on plain packages compared to branded packages, but this effect was not observed among never smokers or daily smokers. Among all participants, investigators found more saccades to health warnings than the rest of the pack on plain packages, but equal numbers of saccades to branding and warnings on branded packages.

Maynard et al, 201435 presented current, regular smokers in the UK with 20 blank cigarette pack images that only contained a health warning, 20 branded packs, and 20 plain packs, with varying familiar (ie, currently used in the UK) and unfamiliar pictorial health warnings. Participants showed more saccades to branding areas than health warning areas for all 3 pack types, including the blank pack that only contained a health warning and no actual brand information. Time course analysis showed that for blank packs, there was a large initial shift in attention towards the health warnings at stimulus onset, but after the first 2 seconds, participants were more likely to fixate on branding (ie, the blank region). For both branded and plain packs, participants showed a slower and smaller increase in attention towards the health warning, with fixations primarily on the branding area.

Shankleman et al36 examined the impact of both plain packaging and warning by manipulating pack type (branded or plain packages based on the Australian Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011) and warning type (black and white text warning, color text warning, or text and image warning) in a study among young adult non-smokers. They found that attention to warnings increased when the warning was presented on plain packs. Greater gaze time for color text warnings than for both black-and-white text and image and text warnings was observed. They also found that among packages with black-and-white text or color text warnings, participants spent longer looking at the warning region on plain packages compared to branded packs.

Finally, Lai et al31 reported eye tracking data for adolescents and adults after all participants viewed the same 6 cigarette packages with graphic warnings. The authors noted that warning text related to social appeal attracted the attention of adults and that text related to impotence attracted adolescents' attention. However, the paper did not report any formal statistical comparisons between the warnings shown, or between populations of interest, and the research was published in a non-peer reviewed journal.

Taken together, these eye tracking studies indicate that: (1) the text framing of a warning can influence attention to the warning, which may differ between tobacco users and non-users (eg, smokers attend more to coping text warning messages whereas non-smokers attend more to high risk text warnings);30,32 and (2) in general, non-smokers and non-daily smokers showed more attention to warnings and less attention to branding when viewing plain packs compared to branded packs;33,34,36 however, this pattern was not always observed among daily smokers.33-35

General Tobacco Communication

Three eye tracking studies examined different approaches to tobacco communication in general.37-39 Smith et al37 investigated 5 versions of corrective statement advertisements proposed by various parties, including Philip Morris and the Department of Justice. In some versions of the corrective statements, including an emotive version proposed by study investigators, participants exhibited larger pupil diameter measured through eye tracking. Participants viewing emotive statements also took less time to locate and fixate on the statements.

In a study by Vlasceanu et al,38 smokers viewed 7 loss-framed messages (ie, consequences from continued smoking) and their opposing 7 gain-framed text-based messages (ie, benefits from stopping smoking). Loss-framed messages were viewed longer by smokers with lower levels of nicotine dependence and those who did not intend to quit smoking in the next 6 months, whereas gain-framed messages were viewed longer by those who intended to quit in the next 6 months. The study should be interpreted with caution as it was published in a non-peer-reviewed journal.

Marodi et al39 examined 4 stimuli from a health promotion brochure that utilized graphic warnings for communication on tobacco prevention. The researchers asked seventh graders to view the warnings in the brochure, and then compared eye tracking measures between the graphic warnings and between the text and graphic portions of the warnings in the brochure. The authors noted that the text seemed to be more important than the image in the graphic warnings, but they did not perform any formal statistical comparisons.

Though limited in their scope and generalizability, these 3 eye tracking communication studies suggest that the message content (eg, messages evoking emotion increased attention compared to more neutral messages37) and frame38 are important factors in attention to tobacco communication, and may not show consistent effects across all groups of smokers. For instance, smokers who intended to quit soon viewed gain-framed communication messages longer, and smokers who did not intend to quit viewed loss-framed messages longer.38

Point-of-Sale

Our search strategy and inclusion criteria identified only one point-of-sale eye tracking study. Bansal-Travers et al40 examined visual attention patterns to cigarette advertising and the power wall (ie, the concentration of tobacco advertising and tobacco products behind the cash register). Items that the young adult participants (smokers and susceptible smokers) were asked to purchase were varied – candy bar only, candy bar and a specific cigarette brand, or candy bar and a cigarette brand of choice. Participants in the candy and cigarette brand of choice condition had the most fixations and dwell time on the power wall, followed by participants asked to purchase candy and a specific cigarette brand. Participants in the candy only condition had the least attention to the power wall as measured by fixations and dwell time.

Given that this is the only published eye tracking study to date to examine attention to advertising at the point-of-sale, more eye tracking studies should be conducted in this area to expand on this work. Such research can inform the development of point-of-sale policies by better understanding how consumer attention to point-of-sale advertising influences perceptions and behavior.

Quality Assessment

The majority of eye tracking studies were judged to be at low or unclear risk of bias (Figure 2). Most studies adequately randomized and concealed participant conditions, had sufficiently complete outcome data, and reported pre-specified outcomes. Many studies had unclear risk of bias for different domains because of a lack of sufficient reporting. Ten studies did not describe blinding of participants to the outcome assessment, which may affect viewing of the stimuli and/or blinding of personnel who scored masked recall to the study hypothesis.14,24-27,30,31,37-39 Eight studies were judged to be at an unclear risk of other biases, either due to not disclosing funding and conflicts of interest, or not reporting any assessment of baseline differences between condition groups.24-27,32,33,38,39 One study was judged to be at high risk of other bias because study conclusions were not substantiated by data.31 All studies employed convenience sampling and most used relatively small sample sizes that may limit generalizability.

Figure 2. Risk of Bias Assessment (N = 18).

Discussion

Whereas the published research on eye tracking in tobacco regulatory science and tobacco control communication is relatively limited, the use of eye tracking has been increasing in recent years. Though the validity of eye tracking has already been demonstrated across a broad array of fields within marketing and academic research,12 the findings from the included studies also support the utility of eye tracking in tobacco control. Eye tracking is an objective method of measuring visual attention and serves as a proxy for data acquisition, thereby providing information that is not captured by surveys and focus groups for which valid measures of attention are often lacking.12 As our brains are wired to use our visual system to gather information about the environment, the utility of eye tracking in tobacco regulatory science goes beyond traditional approaches and offers researchers the ability to observe what our brains choose to attend to without cognitive bias. The findings from this review demonstrate 4 main points that will allow researchers in tobacco control to evaluate outcomes from a range of studies related to how tobacco product packaging (eg, plain packaging and package warnings), advertising, and health warnings are visually attended to and processed by consumers. First, consumers often spend little time attending to health warnings on tobacco advertisements and product packaging or completely ignore or avoid the warnings.24,27,35 However, eye tracking also has revealed that the use of stylized and novel text messages,25 for example, contrasting colors between warning text and background,26 and graphic warnings14,28,29 may help counteract this effect. Second, plain packaging appears to detract consumer attention away from package branding and toward warnings, though this pattern is not consistently seen across all groups of smokers (eg, daily vs weekly).33-36 Third, eye tracking measures (eg, dwell time and number of fixations on warnings) are consistently associated with desirable downstream cognitive processing as indexed by warning recall.14,24,25,27,29 Finally, our findings show little experimental use of eye tracking for evaluating tobacco point-of-sale regulations or tobacco communication campaigns.

The finding in the 3 studies that demonstrated inattentiveness to warnings likely stems from, in part, heavy investment by the tobacco industry in the development of appealing ads41 and enticing product packaging42 that mislead consumers and detract attention from warning messages. Aside from the exceptional appeal of tobacco advertisements or packaging, lack of attention to warnings also may result from ‘wear-out’ effects of existing warnings.43,44 Because 2 studies25,27 found conflicting results about the effect of novel text warning messages on visual attention, additional well-designed eye tracking studies are needed to model the effectiveness of rotating warnings over time and on the impact of novel warnings, particularly new warnings with novel formats, such as colors and stylized graphics. Graphic warnings in particular may attract greater attention than text-only warnings.14,28,29 The development of salient and novel text and graphic warnings on advertisements and packaging can influence how quickly consumers fixate on the warning and how long they attend to it, which are essential for the consumer to begin to process information about the product harms.19

The size and contrast of health warnings on ads and packaging can influence warning noticeability, and thus, warning effectiveness. Non-eye tracking studies in Canada and Australia have found that larger warnings and the use of contrasting colors are associated with higher warning recall, greater warning impact, and increased risk perceptions.10,11 Similarly, we identified 2 eye tracking studies that found text warnings with contrasting colors increased viewer attention and recall25,26 and only one that explicitly measured attention to warnings of different sizes and found no differences between graphic warnings that comprised 20% versus 33% of a cigarette advertisement.14 In accordance with FCTC recommendations, more countries may adopt the use of health warnings on product packaging that comprise at least 30% of the display area.8 Eye tracking research can provide objective data regarding how size, and the interaction between size and other contextual features, affect attention, as well as the effect on tobacco-related perceptions and behavior. Furthermore, one meta-analysis of cigarette pack warnings found that pictorial warnings were more effective at attracting and holding attention compared to text-only warnings (though no effects on recall were observed),45 consistent with our findings from eye tracking studies that showed increased visual attention for graphic warnings on product packages compared to text warnings. Not only can pictorial warnings increase attention, they also can elicit stronger emotions and more negative smoking attitudes45 and importantly, increase successful smoking cessation.46

Though traditional warnings are often ignored or not noticed by consumers, plain packaging appears to be effective at directing attention away from the rest of the pack and toward warnings. On branded packaging, studies found that consumers – both smokers and non-smokers – show similar attention to warnings and brand,33-35 but attention is generally directed toward warnings and away from branding on plain packaging, though this effect seems to vary by smoking status.33-36 These results from experimental eye tracking studies provide novel, objective insight to support findings from other quantitative and qualitative study designs suggesting that plain packaging increases attention to, recall, and effectiveness of warnings,9 and are supportive of FCTC recommendations for countries to adopt plain packaging that restricts the use of elements such as colors and logos that can convey perceptions of less harm to consumers.8 Package standardization is suggested to increase the salience and effectiveness of health warnings and influence risk perceptions and tobacco-related attitudes and behavior.11 Non-eye tracking studies have shown that plain packaging can increase the noticeability, seriousness, and believability of health warnings, though warning size, type, and location are also important factors.11 Importantly, the potential for plain packaging not only to influence perceptions, but also behavior was demonstrated by a cross-sectional survey in Australia that found plain packaging decreased smoking satisfaction and increased thoughts about quitting.47

In addition, because the 5 eye tracking studies that assessed warning recall using masked recall24,25,27 or open-ended recall14,29 after participants viewed health warnings in tobacco advertising found that warning label recall was strongly associated with eye tracking measures such as dwell time and number of fixations,14,24,25,27,29 eye tracking may play a vital role in more rapidly assessing initial impacts of potential new warnings or plain packaging design. Finally, eye tracking is strongly suited for better understanding of the association between noticeability and recall, 2 meaningful outcomes emphasized by the FCTC when assessing the impact of packaging and labeling.8 A message impact framework developed by Noar et al suggests the importance of attention and recall in leading to other meaningful outcomes, such as message reactions, attitudes, intentions, and ultimately behavior.45 Eye tracking data can be used to describe how messages are attended to and recalled (ie, cognitively processed), which in turn, can lead to a better understanding of downstream effects on perceptions and behavior.

Future Directions

Given the amount of research and money the tobacco industry invests in tobacco product advertising41and packaging42 and the ongoing discord regarding the type, size, and placement of warning labels that appear on tobacco ads and products, the use of eye tracking to measure visual attention to each component of ads and packaging (eg, warning text, image, and source) can make a significant contribution to FDA and FCTC priorities to improve understanding of how consumers attend to, and are influenced by, tobacco communication and tobacco product packaging.7,8,48 By better understanding how consumers visually attend to ads and packaging and linking these data to meaningful regulatory outcomes (eg, product perceptions and use behavior), eye tracking can provide an evidence-base for developing and implementing effective regulatory strategies such as plain packaging and communication campaigns.

Through our review we found that eye tracking has been used primarily to examine visual attention to tobacco ads and tobacco product packaging, but it has been underutilized in research on tobacco control campaigns that communicate risks and target change in attitudes and behavior, priorities of the FDA and FCTC.7,9 For example, prior to the execution of multi-million dollar campaigns,49 such as those sponsored by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (eg, “Tips from Former Smokers”) and the FDA (eg, “The Real Cost”), eye tracking can examine how tobacco users and non-users view these advertisements and how attention to the ads may influence downstream perceptions and behavior. In addition, because eye tracking occurs in real time and is not subject to bias from subsequent verbal report; it also can help identify specific ad characteristics that are particularly effective or ineffective at capturing viewers' attention.15

Additionally, as existing eye tracking research primarily has focused on attention to cigarette advertisements and packages, attention to advertisements and packages for non-cigarette tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes, cigars, and hookah, should be explored. Such research can have an important regulatory impact on how these other tobacco products that are increasingly being used, particularly among youth, should be marketed and labeled.

As the use of eye tracking in tobacco control becomes more widely utilized, relating other study measures to eye tracking outcomes, such as changes in risk perception and longer-term recall, can provide valuable information about how attention to tobacco advertisements, tobacco control communication, and product packaging influences perceptions and behavior, and thus, provides objective evidence to support future regulatory policies within the US and globally. However, the overall strength of the data generated by eye tracking is limited by the lack of comparability across studies and by the variability in reporting metrics and terminology. For example, one study28 referred to particular areas of the advertisement that investigators were interested in attention to as ‘look zones’, whereas several others called these same predefined parts of the stimuli ‘areas of interest’.29,30,32,38,40 Different terms also were used across studies when referring to eye tracking outcome measures (eg, dwell time14,25-32,34,36,40 vs gaze time36 vs total fixation duration39). Though these are just slight differences in terminology, standardizing terms used by researchers in the field can clarify the evidence for other researchers and policymakers.15 Furthermore, it is unclear whether bias was introduced in many studies because they did not report blinding of participants to the outcome assessment and of research personnel who scored recall measures to the study hypothesis.14,24-27,30,31,37-39 Participant instructions, for instance, may affect how stimuli are viewed.18 As such, improved quality of reporting and ease of replicability are needed to provide more transparent evidence from eye tracking studies.50 More generally, further work is needed on standardizing eye tracking methodology and reporting metrics to strengthen the scientific evidence base supporting tobacco control policy.

Additionally, though eye tracking has unique strengths in that it can measure noticeability and attention – the first step in the process leading to other important regulatory outcomes such as comprehension, credibility, risk perception, and behavior change8 – its limitations should be acknowledged. For instance, avoidance of tobacco warning messages may actually increase thoughts of smoking harms, rather than having an adverse effect;51 in such circumstances, measurement of visual attention should be carefully considered and interpreted in the context of other data and previous literature. Second, the ecological validity of eye tracking studies can be limited (eg, viewing numerous images of cigarette packs on a computer screen for a few seconds each). Though eye tracking technology has become fairly unobtrusive for participants, findings may not necessarily translate into how consumers would actually view advertisements and product packaging in real-life settings. Another consideration for researchers utilizing eye tracking technology is whether to conduct post-eye tracking qualitative interviews of participants; such data can more fully elucidate why participants viewed stimuli a certain way (eg, familiarity with the ad).15

Limitations

Though we employed a broad search strategy that captured both peer-reviewed and grey literature, we may not have captured all relevant literature because we excluded non-English studies. Publication bias also may have impacted the number of studies found in our search as eye tracking studies without statistically significant results may not have been published.

Implications for Tobacco Regulation

Although challenges remain for researchers to apply eye tracking technologies in experimental studies, eye tracking offers an objective and quantifiable assessment of the connections among attention, health decision making, and consumer behavior. As eye tracking technology and experimental methods advance, eye tracking could be increasingly used to model the impact of changes in health communication strategies on consumer behavior prior to policy implementation. As with all scientific research, barriers may be in place to communicate and disseminate findings to a non-scientific audience, particularly when methods or measures are technical or otherwise complex. This challenge is especially true for tobacco regulatory science inasmuch as that policymakers, governmental agencies, and judges may use research to inform legal decision making. As such, eye tracking technology may provide a useful means to capture information on attention to content for varying groups of consumers, providing valid measures that are likely to be understood by non-scientific audiences.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table S1. Search Strategy

Supplemental Table S2. Characteristics of Included Studies, by Topic Area (N = 18)

Supplemental Table S3. Summary of Findings, by Topic Area (N = 18)

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number P50CA180907 from the National Cancer Institute and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statement: No human subjects were involved in this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement: All authors of this article declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Clare Meernik, Research Specialist, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Family Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC.

Kristen Jarman, Project Manager, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, Chapel Hill, NC.

Sarah Towner Wright, Clinical Librarian, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Health Sciences Library, Chapel Hill, NC.

Elizabeth G. Klein, Associate Professor, The Ohio State University College of Public Health, Division of Health Behavior and Health Promotion, Columbus, OH.

Adam O. Goldstein, Physician, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Family Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC.

Leah Ranney, Director, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Family Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC.

References

- 1.Weiss JW, Cen S, Schuster DV, et al. Longitudinal effects of pro-tobacco and anti-tobacco messages on adolescent smoking susceptibility. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(3):455–465. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2009: Implementing Smoke-Free Environments. Geneva: WHO; 2009. pp. 1–136. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mutti S, Hammond D, Borland R, et al. Beyond light and mild: cigarette brand descriptors and perceptions of risk in the international tobacco control (ITC) four country survey. Addiction. 2011;106(6):1166–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bansal-Travers M, Hammond D, Smith P, Cummings KM. The impact of cigarette pack design, descriptors, and warning labels on risk perception in the US. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(6):674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dube SR, Arrazola RA, Lee J, et al. Pro-tobacco influences and susceptibility to smoking cigarettes among middle and high school students – United States, 2011. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):S45–S51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):25–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed August 12, 2016];Center for Tobacco Products Research Priorities. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/PublicHealthScienceResearch/Research/ucm311860.htm.

- 8.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Guidelines for Implementation of Article 11 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Guidelines for Implementation of Article 12 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control. 2011;20(5):327–337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moodie C, Stead M, Bauld L, et al. Plain Tobacco Packaging: A Systematic Review. Stirling, Scotland: Centre for Tobacco Control Research, University of Stirling; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wedel M, Pieters R. A review of eye-tracking research in marketing. Review of Marketing Research. 2008;4(2008):123–147. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yong HH, Borland R, Hammond D, et al. Smokers' reactions to the new larger health warning labels on plain cigarette packs in Australia: findings from the ITC Australia project. Tob Control. 2016;25(2):181–187. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein EG, Shoben AB, Krygowski S, et al. Does size impact attention and recall of graphic health warnings? Tob Regul Sci. 2015;1(2):175–185. doi: 10.18001/TRS.1.2.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins E, Leinenger M, Rayner K. Eye movements when viewing advertisements. Front Psychol. 2014;5:210. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham DJ, Orquin JL, Visschers VHM. Eye tracking and nutrition label use: a review of the literature and recommendations for label enhancement. Food Policy. 2012;37(4):378–382. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroeber-Riel W. Activation research: psychobiological approaches in consumer research. J Consum Res. 1979;5(4):240–250. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duchowski AT. A breadth-first survey of eye-tracking applications. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2002;34(4):455–470. doi: 10.3758/bf03195475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bucher HJ, Schumacher P. The relevance of attention for selecting news content. An eye-tracking study on attention patterns in the reception of print and online media. Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research. 2006;31(3):347–368. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nonnemaker JM, Choiniere CJ, Farrelly MC, et al. Reactions to graphic health warnings in the United States. Health Educ Res. 2014;30(1):46–56. doi: 10.1093/her/cyu036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parliament Eye Tracking. Philip Morris; 1992. [Accessed August 18, 2016]. Available at: https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/to-bacco/docs/fmxv0067. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eye-Tracking Insight. Philip Morris; 1996. [Accessed August 18, 2016]. Available at: https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/plgj0172. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer PM, Richards JW, Jr, Berman EJ, Krugman DM. Recall and eye tracking study of adolescents viewing tobacco advertisements. JAMA. 1989;261(1):84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krugman DM, Fox RJ, Fletcher JE, Fischer PM. Do adolescents attend to warnings in cigarette advertising? An eye-tracking approach. J Advert Res. 1994;34(6):39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox RJ, Krugman DM, Fletcher JE, Fischer PM. Adolescents' attention to beer and cigarette print ads and associated product warnings. J Advert. 1998;27(3):57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crespo A, Cabestrero R, Grzib G, Quirós P. Visual attention to health warnings in tobacco advertisements: an eye-tracking research between smokers and non-smokers. Studia Psychologica. 2007;49(1):39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson EB, Tomsen S, Lindsay G, John K. Adolescents' attention to traditional and graphic tobacco warning labels: an eye-tracking approach. J Drug Educ. 2010;40(3):227–244. doi: 10.2190/DE.40.3.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strasser AA, Tang KZ, Romer D, et al. Graphic warning labels in cigarette advertisements: recall and viewing patterns. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessels LT, Ruiter RA. Eye movement responses to health messages on cigarette packages. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):352. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai CT, Li PF. A study on the communicative effectiveness of graphic warning labels on tobacco packages in Taiwan. China Media Research. 2011;7(1):25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sussenbach P, Niemeier S, Glock S. Effects of and attention to graphic warning labels on cigarette packages. Psychol Health. 2013;28(10):1192–1206. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.799161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munafo MR, Roberts N, Bauld L, Leonards U. Plain packaging increases visual attention to health warnings on cigarette packs in non-smokers and weekly smokers but not daily smokers. Addiction. 2011;106(8):1505–1510. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maynard OM, Munafo MR, Leonards U. Visual attention to health warnings on plain tobacco packaging in adolescent smokers and non-smokers. Addiction. 2013;108(2):413–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maynard OM, Attwood A, O'Brien L, et al. Avoidance of cigarette pack health warnings among regular cigarette smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;136:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shankleman M, Sykes C, Mandeville KL, et al. Standardised (plain) cigarette packaging increases attention to both text-based and graphical health warnings: experimental evidence. Public Health. 2015;129(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith P, Bansal-Travers M, O'Connor R, et al. Correcting over 50 years of tobacco industry misinformation. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(6):690–698. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vlăsceanu S, Vasile M. Gain or loss: how to frame an anti-smoking message? Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;203:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maródi Á, Devosa I, Steklács J, et al. Eye-tracking analysis of the figures of anti-smoking health promoting periodical's illustrations. Practice and Theory in Systems of Education. 2015;10(3):285–293. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bansal-Travers M, Adkison SE, O'Connor RJ, Thrasher JF. Attention and recall of point-of-sale tobacco marketing: a mobile eye-tracking pilot study. AIMS Public Health. 2016;3(1):13–24. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2016.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Cigarette Report for 2013. Washington, DC: FTC; 2016. [Accessed August 21, 2016]. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2013/2013cigaretterpt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, Cummings KM. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl 1):173–180. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, et al. Communicating risk to smokers: the impact of health warnings on cigarette packages. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(3):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White V, Bariola E, Faulkner A, et al. Graphic health warnings on cigarette packs: how long before the effects on adolescents wear out? Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):776–783. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, et al. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tob Control. 2016;25(3):341–354. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, et al. Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):905–912. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wakefield MA, Hayes L, Durkin S, Borland R. Introduction effects of the Australian plain packaging policy on adult smokers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e003175. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Guidelines for Implementation of Article 13 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu X, Alexander RL, Simpson SA, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of the first federally funded antismoking campaign. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(3):318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maynard OM, Munafo MR. Methods reporting in human laboratory studies. Addiction. 2013;108(5):1002–1003. doi: 10.1111/add.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yong HH, Borland R, Thrasher JF, et al. Mediational pathways of the impact of cigarette warning labels on quit attempts. Health Psychol. 2014;33(11):1410–1420. doi: 10.1037/hea0000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table S1. Search Strategy

Supplemental Table S2. Characteristics of Included Studies, by Topic Area (N = 18)

Supplemental Table S3. Summary of Findings, by Topic Area (N = 18)