Abstract

Background

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) who begin antidepressant treatment discontinue use before for six months, the recommended minimum treatment length. This study sought to identify predictors of six-month antidepressant persistence including predictors utilizing patients’ electronic prescription records.

Methods

Commercially insured children (3–17 years) and adults (18–64 years) with MDD who initiated antidepressant treatment, 1/1/2003–2/28/2010, were assessed for six-month persistence (based on prescriptions’ days supply, allowing a 30-day grace period). Antidepressant persistence prediction models were developed separately for children and adults. Two additional measures, days without medication between the first and second antidepressant fill (children and adults) and prior persistence on other medications (adults only), were added to the models, concordance (c) statistics were compared and risk reclassification evaluated.

Results

Among children (n=8,837 children) and adults (n=47,495) with MDD, six-month antidepressant persistence was low and varied by age (37%, 18–24 years to 52%, 3–12 and 50–64 years, respectively). Independent baseline predictors of persistence were identified, with model c-statistics: children=0.582, adults=0.584. Patients with more days without medication between fills were less likely to be persistent (10–30 vs. 0 days, children: RR=0.72, adults: RR=0.74), as were adults not previously persistent to other medications (RR=0.73).

Limitations

The definition of 6-month persistence is dependent on correct days supply values and the grace period utilized; potential predictors were limited to measures available in claims data.

Conclusions

Six-month antidepressant persistence was low and overall prediction of persistence was poor; however, days without medication between fills and prior persistence on other medications marginally improved the ability to predict antidepressant persistence.

INTRODUCTION

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends that patients with mild to severe major depressive disorder (MDD) treated with antidepressants receive a minimum of 6–12 weeks of treatment to achieve symptom remission followed by 4–9 months of treatment to prevent relapse (American Psychiatric Association, 2010). Organizations outside the United States (US) also recommend that patients with MDD continue antidepressant treatment for ≥6 months following symptom remission (Kennedy SH et al., 2009; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2005; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Nutt DJ et al., 2010). Nevertheless, low rates of 6-month antidepressant persistence have been observed in children and adults (Esposito D et al., 2009; Fontanella CA et al., 2011; Hansen D et al., 2004; Lu C and Roughead E, 2012; Mullins CD et al., 2005; Sawada N et al., 2009; Tournier M et al., 2009; Wu C et al., 2013; Yau WY et al., 2014).

Persistence, defined as the length of time between medication initiation and medication discontinuation, is a component of adherence, which is defined as the process by which patients take medication as prescribed (Vrijens B et al., 2012). Most previous studies examining factors related to persistence focused on adults. Factors identified in these studies include gender, age, race, education, co-morbidities, concomitant medication use, medication cost, adverse side effects, antidepressant agent, insurance type, follow-up visits, and symptom improvement (Assayag J et al., 2013; Bull SA et al., 2002; Esposito D et al., 2009; Hansen D et al., 2004; Lu C and Roughead E, 2012; Mullins CD et al., 2005; Sawada N et al., 2009; Wu C et al., 2012; Wu C et al., 2013; Yau WY et al., 2014). Beyond baseline measures, gaps in antidepressant prescription refills based on administrative pharmacy records predicted antidepressant discontinuation in adults. Specifically, a 14-day gap in medication supply during the first 90 days of treatment identified four of every five patients at risk for discontinuing (Hansen RA et al., 2010). Additionally, in other settings, adherence (measured by the medication possession ratio) to medications taken for unrelated chronic indications improved the prediction of oral bisphosphonate adherence (Curtis JR et al., 2009). Adherence to antidepressant treatment (90 days of medication supply in first 180 days after initiation) was a marginal predictor of concurrent antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medication adherence (medication possession ratio ≥80%) (Simon GE et al., 2013). It was unknown whether prior persistence on other chronic medications, a measure available prior to antidepressant initiation, and antidepressant refill gaps, a measure available soon after antidepressant initiation, would improve the ability to predict antidepressant persistence. As these measures could be made readily available to clinicians through prescription refill records (or by patient self-report), estimating whether they offer an advantage over standard predictors could potentially prove useful.

In Medicaid-enrolled children, factors previously identified as associated with higher antidepressant adherence (measured by the proportion of days with medication) during the treatment continuation phase include use of other psychotropic drugs, absence of substance use disorders, and foster-case Medicaid eligibility (Fontanella CA et al., 2011). By contrast, factors associated with antidepressant persistence in children have not been identified. Whether important variation in predictors of persistence in children and adults differ is unknown. To expand upon the existing literature the current study a) estimates 6-month antidepressant persistence for children and adults with MDD in a large US commercially insured population, b) creates and validates a baseline prediction model for antidepressant persistence separately in children and adults, and c) determines if our baseline prediction model improves when a patient’s delay in filling the second antidepressant prescription and a patient’s prior persistence on other chronic medications are taken into account.

METHODS

Data source & study population

Data for this analysis was drawn from the LifeLink Health Plan Claims Database, purchased from IMS Health (IMS Health Incorporated, 2015). The database covers commercially insured individuals and their dependents across the US, containing medical and pharmaceutical claims for approximately 60 million unique patients from 98+ US health plans. The database includes inpatient and outpatient International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes, Current Procedural Terminology, 4th edition, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System procedure codes and records for reimbursed, dispensed prescriptions. The database has been used in the past for epidemiologic research involving antidepressants (Miller M et al., 2014b; Valuck RJ et al., 2007) including studies describing adults and children initiating antidepressant therapy (Czaja AS and Valuck R, 2012; Milea D et al., 2010). The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

The study cohort includes children (3–17 years) and adults (18–64 years) with a diagnosis of MDD who initiate an SSRI or SNRI between January 2003 and February 2010. MDD was defined as an inpatient or outpatient diagnosis (ICD-9-CM: 296.2x, 296.3x) in the year prior to antidepressant initiation. SSRIs (sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine) and SNRIs (venlafaxine, duloxetine) included in the study were limited to those FDA approved for depression and those more commonly used. Patients were required to have no record of any antidepressant use in the prior year, to have continuous insurance enrollment in the prior year and in the 6 months following antidepressant initiation, and, to avoid imputation, a days supply value >0 for the index antidepressant prescription and prescriptions in the following 6 months. Patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in the prior year were excluded.

Antidepressant persistence

To calculate persistence, defined as ≥6 months between antidepressant initiation and antidepressant discontinuation, we followed each patient beginning on the index antidepressant’s dispensing date. For each prescription dispensing date, the days supply of medication was added to a 30-day grace period, to account for missed doses. If there was no refill by the end of the days supply plus grace period, the patient was considered to have stopped treatment at that point. The patient was categorized as non-persistent if treatment had been stopped before 180 days after the index antidepressant’s dispensing date; otherwise the patient was categorized as persistent. A 30-day grace period was selected because the majority (89%) of patients had an initial days supply value for ≤30 days (only 5% had an initial days supply of ≥90 days). Additionally, a longer grace period would have overestimated 6-month persistence. For a sensitivity analysis we used a more restrictive 15-day grace period. Switching SSRI, SNRI, or between SSRI and SNRI agents was regarded as treatment continuation.

Potential predictors

Potential predictors of persistence were collected in the year prior to antidepressant initiation and included age, sex, psychiatric and non-psychiatric co-morbidities, healthcare utilization, antidepressant class (SSRI, SNRI), prior suicide attempt (external cause of injury codes: E950.x–E959.x), high and mid-potency prescription opiate usage, recurrent MDD diagnosis (ICD-9-CM: 296.3x), and service provider type for the index antidepressant. Patient copayment for the index antidepressant was calculated by subtracting the amount paid by the insurance plan from the amount the insurance plan allowed per prescription (typically the amount paid plus patient liability). Copayment was categorized as low vs. high based on the copayment value at the 75th percentile for children (low: <$16) and adults (low: <$24). Initial antidepressant dose was categorized into low, non-low, and unknown. Low initial dose was defined per agent based on available guidelines for starting dose (American Psychiatric Association, 2010; British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2013; Geller DA et al., 2012; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK), 2005; Nutt DJ et al., 2010). The measures for substance use included patients with a substance use related hospitalization and patients with a substance use disorder diagnosis without a hospitalization. We constructed a hierarchical measure of depression severity with depression-related diagnoses characterized as inpatient vs. outpatient diagnosis and timing of the inpatient diagnosis, i.e. within 30 days of antidepressant initiation vs. 31–360 days (Miller M et al., 2014a).

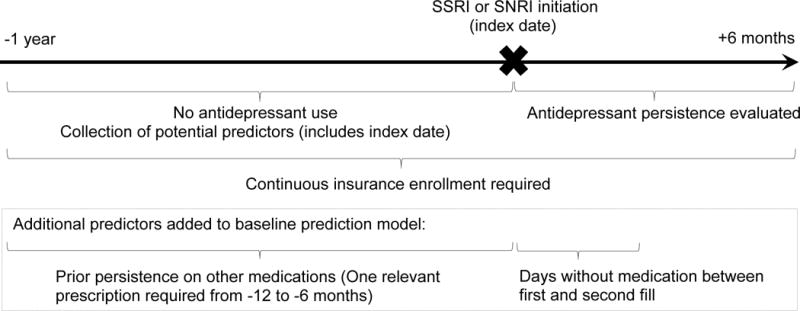

Days without medication & prior persistence on other medications

We created a measure of days without medication between the first and second antidepressant prescription fill and a measure of prior persistence on other chronic medications. The measure of days without medication was calculated by subtracting the index days supply from the number of days between the dispensing dates of the first and second prescriptions (categorized to 0, 1–9, or 10–30 days). The measure was estimated only in the subset of patients who filled a second antidepressant prescription before the end of the first 30-day grace period. The measure of prior persistence on other medications was based on use of anti-hyperlipidemics, anti-hypertensives, bone-density regulators, or chronic asthma medications, medications customarily taken consistently. As these and other medications for chronic conditions are not commonly prescribed for children, prior persistence on other medications was assessed only in adults. We defined prior persistence on other medications as the use of that medication for at least 180 days before antidepressant initiation. Therefore, the measure of prior persistence on other medications was created only in adults with a record of a dispensed prescription for a chronic medication in the 6–12 months prior to antidepressant initiation. All other adults were excluded from the analyses involving the measure of prior persistence on other medications. Patients with 180 days of continued use on ≥1 unrelated chronic medication in the year before antidepressant initiation, allowing a 30-day grace period, were considered persistent to prior other chronic medications. Figure 1 summarizes the study design.

Figure 1.

Study schematic for predicting antidepressant persistence and identification of additional predictors

Statistical analyses

We estimated the proportion of patients persistent on antidepressant treatment at 6 months overall and for each predictor, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) by age group. We used log-binomial regression to determine the adjusted risk ratios (RR) with 95% CIs for 6-month persistence. Predictors with a p-value <0.05 and a magnitude of effect ≥5% in the RR of persistence (in at least 1 strata for categorical variables), were included in the baseline prediction model. To provide a measure of model fit, the concordance (c) statistic was calculated. The c-statistic is a rank-based measure of discrimination representing the probability a randomly selected pair of persistent and non-persistent subjects will be correctly ranked with regards to their antidepressant persistence status, ranging from 0.5 (no discrimination) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination) (Cook NR, 2007; Hanley JA and McNeil BJ, 1982). When calculating the c-statistic, we entered age, copayment, outpatient visit count, and generic prescription drug count as continuous variables with polynomial terms added based on a likelihood ratio test (p<0.1). After adding the measure of days without medication between fills (continuous with polynomial term) and prior persistence on other medications to the baseline prediction models we recalculated the c-statistics. In the subset of adults with both a measure of prior persistence on other medications and a measure of days without medication we used a classification and regression tree (CART) to determine if interactions were present between predictors of antidepressant persistence, particularly between days without medication and prior persistence on other medications. We set the minimum number of observations per node to attempt a split to 30 and the complexity parameter (cp) to 0.002; we used tree pruning to balance complexity with model fit (final cp=0.0032) (Lewis RJ, 2000; Therneau T et al., 2015).

To better evaluate the clinical utility of the measure of days without medication and the measure of prior persistence on other medications we assessed clinical risk classification. Risk reclassification cross-classifies patients into strata of predicted probabilities of antidepressant persistence based on the baseline prediction model with and without an additional measure (Cook NR, 2008; Cook NR et al., 2006). Improved reclassification occurred when persistent patients moved into a higher strata of predicted probability after the additional measure was added and when non-persistent patients moved into a lower strata (Ridker PM et al., 2008). Reclassification tables are stratified by observed antidepressant persistence status (Pencina MJ et al., 2008). In the absence of predefined risk categories for antidepressant persistence, we selected a 15% window around the observed mean 6-month antidepressant persistence in each subset. These three categories created clinically meaningful groupings that separated patients with a low likelihood of antidepressant persistence from those with a higher likelihood. A wider window was not used given the narrow distribution of predicted probabilities of antidepressant persistence from the baseline prediction models (ex. interquartile range in the adult baseline model=40–50%). We calculated the overall net reclassification improvement (NRI) to summarize the improvement in the distribution of patients across the strata when each additional measure was added (positive NRI=improved reclassification, with more benefit seen as the NRI increases) (Leening MJG et al., 2014; Pencina MJ et al., 2008). Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC) and R version 3.2.0.

RESULTS

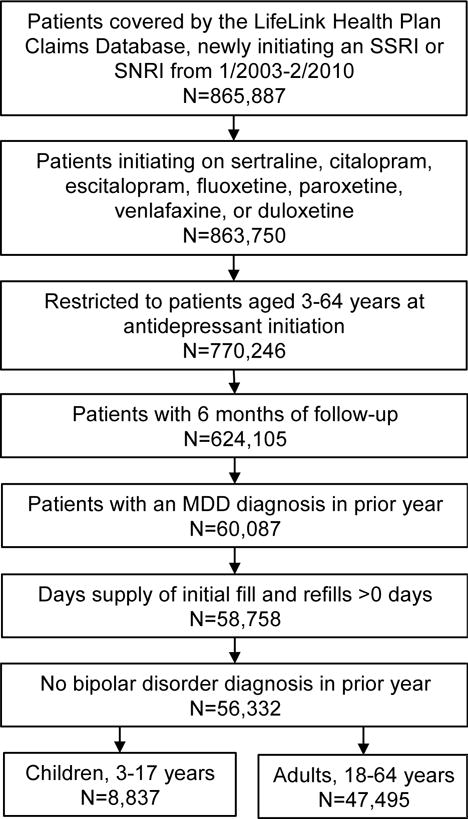

Between January 2003 and February 2010, 770,246 patients aged 3–64 years initiated an SSRI or SNRI with no antidepressant use in the prior year. Patients with <6 months of follow-up (n=146,141), no MDD diagnosis in the prior year (n=564,018), a days supply value ≤0 (n=1,329), or prior bipolar diagnosis (n=2,436) were sequentially excluded (Figure 2). The final cohort included 8,837 children and 47,495 adults.

Figure 2.

Study population inclusion criteria

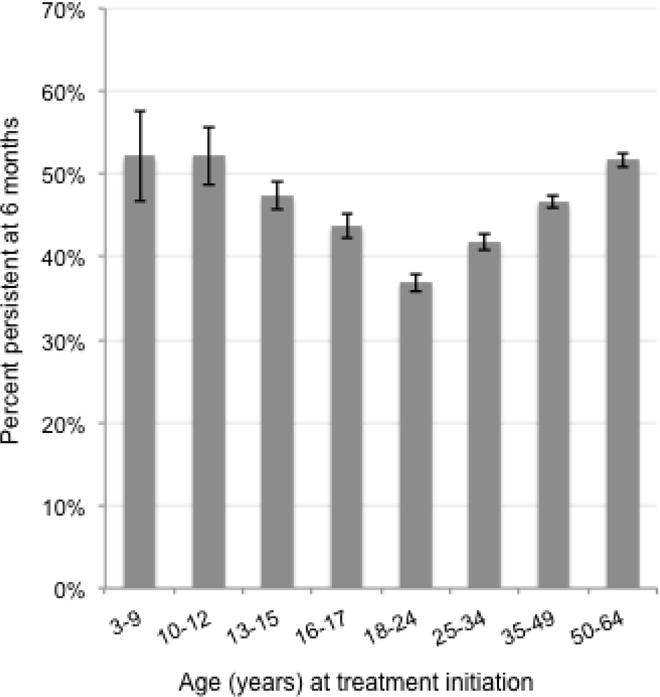

Overall, 46% of children and 45% of adults persisted on antidepressant treatment for 6 months. Persistence was lowest among those aged 18–24 years (37%), and highest among children, 3–12 years of age (52%) and among our oldest adults (i.e., those 50–64 years of age, 52%), (Figure 3). The baseline prediction model for children (Table 1, RR>1 indicates increased likelihood of persistence) resulted in a c-statistic of 0.582, indicating a weak ability to correctly discriminate between persistent and non-persistent patients. The baseline prediction model for adults (Table 2) resulted in a similar c-statistic of 0.584. The sensitivity analysis defining persistence with a more restrictive grace period (15-day), resulted in lower estimates of 6-month persistence (32% in children, 34% in adults), but the models’ predictive abilities were similar (c-statistics: children=0.574, adults=0.588).

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients persistent on antidepressant treatment at 6 months by age at initiation

Error bars depict 95% confidence intervals

Table 1.

Children with major depressive disorder, predicting persistence on antidepressant treatment at six months (n=8,837) a

| Total No. (%) | Proportion persistent % | Baseline prediction model RR (95% CI) e | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Female | 5,653 (64) | 46 | – |

| Age at antidepressant initiation (years), mean ± SD | 15 ± 2 | ||

| 3 – 9 | 318 (4) | 52 | 1.12 (1.00, 1.25) |

| 10 – 12 | 802 (9) | 52 | 1.16 (1.07, 1.25) |

| 13 – 15 | 3,288 (37) | 47 | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11) |

| 16 – 17 | 4,429 (50) | 44 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Index antidepressant class | |||

| SSRI | 8,469 (96) | 46 | – |

| SNRI | 368 (4) | 45 | – |

| Index dose | |||

| Low initial dose b | 2,381 (27) | 48 | 1.07 (1.01, 1.12) |

| Non-low initial dose | 6,267 (71) | 45 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Unknown dose | 189 (2) | 43 | 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) |

| MDD recurrent episode | 3,540 (40) | 45 | 0.94 (0.90, 0.98) |

| Depression Severity c | |||

| 1 outpatient diagnosis prior year | 1,653 (19) | 45 | – |

| ≥2 outpatient diagnoses prior year | 5,519 (62) | 48 | – |

| Non-primary inpatient diagnosis prior year | 282 (3) | 41 | – |

| Primary inpatient diagnosis 31–360 days prior | 166 (2) | 40 | – |

| Primary inpatient diagnosis ≤30 days prior | 1,217 (14) | 42 | – |

| Suicide attempt | 330 (4) | 41 | – |

| Personality disorder | 133 (2) | 45 | – |

| ADHD | 1,410 (16) | 48 | – |

| Anxiety | 2,140 (24) | 51 | 1.10 (1.05, 1.16) |

| Substance use disorder | |||

| No substance use disorder diagnosis | 8,069 (91) | 47 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Substance use disorder diagnosis, no hospitalization | 717 (8) | 33 | 0.71 (0.64, 0.79) |

| Substance use disorder related hospitalization | 51 (1) | 33 | 0.71 (0.48, 1.05) |

| Non-psychiatric related hospitalizations (1+) | 472 (5) | 43 | – |

| Outpatient visits, mean ± SD | 15 ± 13 | ||

| <5 | 1,406 (16) | 41 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 5 – 9 | 2,365 (27) | 44 | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) |

| 10 – 19 | 2,995 (34) | 46 | 1.12 (1.04, 1.20) |

| 20 – 39 | 1,660 (19) | 52 | 1.26 (1.17, 1.37) |

| ≥40 | 411 (5) | 52 | 1.28 (1.15, 1.43) |

| Generic prescription drugs, mean ± SD | 4 ± 3 | ||

| Antidepressant only | 1,647 (19) | 44 | – |

| 2 – 3 | 3,044 (34) | 46 | – |

| 4 – 5 | 1,974 (22) | 47 | – |

| 6 – 9 | 1,628 (18) | 46 | – |

| ≥10 | 544 (6) | 48 | – |

| Mid-potency opiate | 1,114 (13) | 45 | – |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 240 (3) | 49 | – |

| Diabetes | 105 (1) | 51 | – |

| Cluster headaches/migraines | 290 (3) | 47 | – |

| Provider specialty d | |||

| Psychiatry | 3,305 (37) | 48 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Psychology | 610 (7) | 47 | 0.97 (0.89, 1.07) |

| Pediatrics | 823 (9) | 50 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) |

| General, family practice | 1,215 (14) | 43 | 0.93 (0.87, 1.01) |

| Internal medicine | 265 (3) | 48 | 1.04 (0.91, 1.18) |

| Other | 1,948 (22) | 43 | 0.91 (0.86, 0.97) |

| Unknown | 671 (8) | 45 | 0.97 (0.89, 1.06) |

| Copayment for index prescription, mean ± SD | 13 ± 16 | ||

| Low copayment (<$16) | 6,616 (75) | 46 | – |

| High copayment ($16+) | 2,221 (25) | 45 | – |

SD (standard deviation), RR (risk ratio), CI (confidence interval), SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), SNRI (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor), ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder)

Symbol ‘ – ‘ signifies variable did not end up in the baseline prediction model

Comorbidity definitions are based on diagnostic codes recorded in the prior year; the prevalence of some conditions may be underestimated if the patient did not receive a diagnostic code in that year period.

Persistent at six-months defined as treatment for 180 days without gaps based on days supply, with 30 day grace period; all individuals were required to be continually enrolled for at least 180 days after antidepressant initiation

Low dose=3–12 years: <10mg/day (mg/d) Citalopram, Fluoxetine, and Paroxetine immediate release (IR), <12.5mg/d Paroxetine controlled release (CR), <25mg/d Sertraline, ≤30mg/d Duloxetine, and <37.5mg/d Venlafaxine; 13–17 years: <20mg/d Citalopram and Fluoxetine, <10mg/d Paroxetine IR, <12.5mg/d Paroxetine CR, <50mg/d Sertraline, <60mg/d Duloxetine, and <75mg/d Venlafaxine

Depression diagnoses included in severity measure: ICD-9-CM: 296.2x, 296.3x, 298.0x, 300.4x, 309.0x, 309.1x, 311.x, 293.83, 296.90, 309.28

Provider specialty associated with the index antidepressant prescription; ‘Unknown’ included missing, not available, and unknown

RR>1.00 signifies increased likelihood of persistence

Table 2.

Adults with major depressive disorder, predicting persistence on antidepressant treatment at six months (n=47,495) a

| Total No. (%) | Proportion persistent % | Baseline prediction model RR (95% CI) e | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Female | 30,458 (64) | 46 | – |

| Age at antidepressant initiation (years), mean ± SD | 40 ± 13 | ||

| 18 – 24 | 8,187 (17) | 37 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 25 – 34 | 8,935 (19) | 42 | 1.13 (1.09, 1.18) |

| 35 – 49 | 17,432 (37) | 47 | 1.26 (1.22, 1.30) |

| 50 – 64 | 12,941 (27) | 52 | 1.39 (1.34, 1.44) |

| Index antidepressant class | |||

| SSRI | 40,265 (85) | 45 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| SNRI | 7,230 (15) | 49 | 1.07 (1.04, 1.10) |

| Index dose | |||

| Low initial dose b | 6,710 (14) | 43 | 0.93 (0.90, 0.96) |

| Non-low initial dose | 39,578 (83) | 46 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Unknown dose | 1,207 (3) | 49 | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) |

| MDD recurrent episode | 25,765 (54) | 46 | – |

| Depression severity c | |||

| 1 outpatient diagnosis prior year | 13,740 (29) | 46 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| ≥2 outpatient diagnoses prior year | 29,429 (62) | 46 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) |

| Non-primary inpatient diagnosis prior year | 1,608 (3) | 39 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) |

| Primary inpatient diagnosis 31–360 days prior | 397 (1) | 39 | 0.90 (0.80, 1.02) |

| Primary inpatient diagnosis ≤30 days prior | 2,321 (5) | 37 | 0.91 (0.86, 0.97) |

| Suicide attempt | 511 (1) | 37 | – |

| Personality disorder | 639 (1) | 41 | – |

| ADHD | 1,497 (3) | 42 | – |

| Schizophrenia | 272 (1) | 43 | – |

| Anxiety | 13,105 (28) | 46 | – |

| Substance use disorder | |||

| No substance use disorder diagnosis | 41,455 (87) | 47 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Substance use disorder diagnosis, no hospitalization | 5,557 (12) | 37 | 0.84 (0.81, 0.87) |

| Substance use disorder related hospitalization | 483 (1) | 31 | 0.70 (0.61, 0.81) |

| Non-psychiatric related hospitalization (1+) | 5,320 (11) | 42 | – |

| Outpatient visits, mean ± SD | 19 ± 18 | ||

| <5 | 7,103 (15) | 44 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 5 – 9 | 10,498 (22) | 45 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) |

| 10 – 19 | 14,058 (30) | 45 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) |

| 20 – 39 | 10,887 (23) | 46 | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) |

| ≥40 | 4,949 (10) | 47 | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) |

| Generic prescription drugs, mean ± SD | 6 ± 5 | ||

| Antidepressant only | 4,835 (10) | 47 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 2 – 3 | 11,578 (24) | 46 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) |

| 4 – 5 | 9,472 (20) | 47 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) |

| 6 – 9 | 12,227 (26) | 45 | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) |

| ≥10 | 9,383 (20) | 43 | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97) |

| High-potency prescription opiate usage | 905 (2) | 39 | 0.92 (0.84, 0.99) |

| Mid-potency prescription opiate usage | 14,088 (30) | 41 | 0.88 (0.86, 0.91) |

| Cancer, malignant neoplasm | 1,769 (4) | 50 | – |

| Arthritis | 422 (1) | 48 | – |

| Osteoarthritis | 2,914 (6) | 48 | – |

| Postural hypotension | 129 (0) | 51 | – |

| Congestive heart failure | 561 (1) | 44 | – |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 2,064 (4) | 45 | – |

| Urinary incontinence | 445 (1) | 44 | – |

| Diabetes | 3,595 (8) | 47 | – |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1,071 (2) | 45 | – |

| Gait or balance disorder | 575 (1) | 48 | – |

| Cluster headaches/migraines | 2,320 (5) | 43 | – |

| Seizures | 473 (1) | 45 | – |

| Osteoporosis | 771 (2) | 48 | – |

| Provider specialty d | |||

| Psychiatry | 13,836 (29) | 47 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Psychology | 2,842 (6) | 45 | 0.95 (0.90, 0.99) |

| General, family practice; pediatrics | 12,163 (26) | 47 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) |

| Internal medicine | 4,501 (9) | 47 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) |

| Other | 10,666 (22) | 42 | 0.92 (0.89, 0.94) |

| Unknown | 3,487 (7) | 43 | 0.94 (0.91, 0.98) |

| Copayment for index prescription, mean ± SD | 17 ± 22 | ||

| Low copayment (<$24) | 35,505 (75) | 46 | – |

| High copayment ($24+) | 11,990 (25) | 45 | – |

SD (standard deviation), RR (risk ratio), CI (confidence interval), SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), SNRI (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor), ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder)

Symbol ‘ – ‘ signifies variable did not end up in the baseline prediction model

Comorbidity definitions are based on diagnostic codes recorded in the prior year; the prevalence of some conditions may be underestimated if the patient did not receive a diagnostic code in that year period.

Persistent at six-months defined as treatment for 180 days without gaps based on days supply, with 30 day grace period; all individuals were required to be continually enrolled for at least 180 days after antidepressant initiation

Low dose=18–64 years: <20mg/day (mg/d) Citalopram, Fluoxetine, and Paroxetine immediate release, <25mg/d Paroxetine controlled release, <50mg/d Sertraline, <60mg/d Duloxetine, and <75mg/d Venlafaxine

Depression diagnoses included in severity measure: ICD-9-CM: 296.2x, 296.3x, 298.0x, 300.4x, 309.0x, 309.1x, 311.x, 293.83, 296.90, 309.28

Provider specialty associated with the index antidepressant prescription; ‘Unknown’ included missing, not available, and unknown

RR>1.00 signifies increased likelihood of persistence

Days without medication

Seventy-seven percent (n=6,837) of children and 70% (n=33,212) of adults filled a second antidepressant prescription and therefore had a measure of days without medication between fills. Patients filling a second prescription were similar to the full cohort (Appendix A). In this subset, 59% of children and 65% of adults persisted on antidepressant treatment for 6 months. Days without medication between the first and second antidepressant fill was associated with antidepressant persistence (Table 3). For example, among children with an antidepressant refill who had no days without medication between fills, 64% were persistent at 6 months compared with 46% in children who had 10–30 days without medication between fills. Added to the baseline prediction models, 10–30 days without medication was associated with a decreased likelihood of persistence in children (RR=0.72) and adults (RR=0.74) compared to no days (Table 3). The c-statistic moderately improved with the measure of days without medication, children: 0.583 (baseline model in subset with second prescription) to 0.617 (baseline model + days without medication) and adults: 0.603 to 0.635.

Table 3.

Association of days without medication between fills and prior persistence on other chronic medications with antidepressant persistence

| Total No. | Proportion persistent to antidepressant % | Baseline prediction model a + additional measure RR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| CHILDREN | |||

| Days without medication between fills (n=6,828) b | |||

| 0 days | 3,707 | 64 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1 – 9 days | 2,001 | 58 | 0.91 (0.87, 0.95) |

| 10–30 days | 1,120 | 46 | 0.72 (0.67, 0.77) |

| ADULTS | |||

| Days without medication between fills (n=33,212) b | |||

| 0 days | 17,375 | 70 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1 – 9 days | 10,101 | 64 | 0.92 (0.90, 0.93) |

| 10–30 days | 5,736 | 52 | 0.74 (0.72, 0.76) |

| Prior persistence on other chronic medication (n=5,755) c | |||

| Persistent on other medication | 4,583 | 55 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Not persistent on other medication | 1,172 | 40 | 0.73 (0.68, 0.79) |

RR (risk ratio), CI (confidence interval)

Baseline prediction model for children: age, initial low dose, recurrent major depressive disorder, anxiety diagnosis, substance use, outpatient visits, provider specialty; adults: age, antidepressant class, initial low dose, depression severity, substance use, outpatient visits, prescription count, high and mid-potency opiate usage, hypotension, provider specialty

Measure of the number of days without medication between the first and second antidepressant fill, based on dispensing dates and days supply, among children and adults with a second antidepressant fill

Prior persistence on other medications measured whether an individual remained on an anti-hyperlipidemic, antihypertensive, bone-density regulator, or chronic asthma medication for at least 6 months in the year prior to antidepressant initiation

When added to the baseline model, the measure of days without medication reclassified 36% of children, 57% of those had improved reclassification (Table 4). For example, in the baseline model, 2,984 children had a predicted probability of antidepressant persistence 52–67% and were observed to be persistent. With the addition of days without medication, 20% moved correctly into a higher stratum of predicted persistence, 16% moved incorrectly into a lower stratum, and 65% remained in the same stratum (Table 4). The overall NRI was 11.1, demonstrating that the measure improved our ability to classify patients based on those strata. Similarly, the measure of days without medication reclassified 37% of adults, 58% of those had improved reclassification (Table 4). The resulting NRI in adults was 10.7.

Table 4.

Reclassification of predicted probabilities of antidepressant persistence with the measure of days without medication added to the baseline model, children (n=6,828) and adults (n=33,212)

| Baseline model + days without medication a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline model, Predicted probabilities Frequency (row %) |

||||

| CHILDREN b | <52.0% | 52.0 to 67.0% | >67.0% | Total, No. |

|

|

||||

| Persistent on antidepressant | ||||

| <52.0% | 258 (67%) | 129 (33%) | 0 | 387 |

| 52.0 to 67.0% | 469 (16%) | 1,932 (65%) | 583 (20%) | 2,984 |

| >67.0% | 15 (2%) | 172 (25%) | 504 (73%) | 691 |

| Not persistent on antidepressant | ||||

| <52.0% | 320 (74%) | 113 (26%) | 0 | 433 |

| 52.0 to 67.0% | 570 (28%) | 1,221 (59%) | 281 (14%) | 2,072 |

| >67.0% | 10 (4%) | 82 (31%) | 169 (65%) | 261 |

| ADULTS b | <57.2% | 57.2 to 72.2% | >72.2% | Total, No. |

|

|

||||

| Persistent on antidepressant | ||||

| <57.2% | 2,142 (61%) | 1,373 (39%) | 0 | 3,515 |

| 57.2 to 72.2% | 1,924 (15%) | 7,842 (61%) | 3,152 (24%) | 12,918 |

| >72.2% | 164 (3%) | 1,134 (22%) | 3,759 (74%) | 5,057 |

| Not persistent on antidepressant | ||||

| <57.2% | 2,294 (71%) | 930 (29%) | 0 | 3,224 |

| 57.2 to 72.2% | 1,871 (27%) | 3,907 (57%) | 1,026 (15%) | 6,804 |

| >72.2% | 109 (6%) | 538 (32%) | 1,047 (62%) | 1,694 |

Measure of the number of days without medication between the first and second antidepressant fill, based on dispensing dates and days supply, among children and adults with a second antidepressant fill

Overall NRI=11.1 (children) and 10.7 (adults); NRI calculation = [(number of persistent patients classified up − number of persistent patients classified down)/total number of persistent patients] + [(number of non-persistent patients classified down − number of non-persistent patients classified up)/total number of non-persistent patients]

Prior persistence on other medications

A measure of prior persistence on other medications was available in 12% (n=5,755) of adults. Compared to the full adult cohort, the subset with a measure of prior persistence on other medications were more likely to be older and male and to have more healthcare utilization and co-morbidities (Appendix A). The proportion persistent on antidepressant treatment was higher in the subset with a measure of prior persistence (52%) than in the full adult cohort (45%). Among this subgroup, adults not persistent on a prior other medication were less likely to be persistent on antidepressant treatment than were adults who were persistent on a prior other medication (40% vs. 55%), RR=0.73 when added to the baseline model (Table 3). The addition of the measure of prior persistence on other medications to the baseline model improved the c-statistic (0.571 to 0.595), with the relative change being slightly less than the change from adding the days without medication measure. Regarding risk reclassification, 29% of adults were reclassified when prior persistence was added, 57% of those had improved reclassification, an overall NRI of 8.5 (results not shown).

In adults (n=4,195) with a measure of prior persistence on other medications and a measure of days without medication, 71% were persistent on antidepressant treatment. Days without medication resulted in a larger c-statistic improvement (0.575 to 0.616) than prior persistence on other medications (0.575 to 0.595) when each measure was separately added to the baseline model. Together the measures increased the c-statistic to 0.627. The CART analysis identified three patient subgroups: patients with 10–30 days without medication between fills (likelihood of persistence=57%), patients with 0–9 days without medication who were not persistent on prior other medications (64%), and patients with 0–9 days without medication who were persistent on prior other medications (76%).

DISCUSSION

Overall, less than half of patients with MDD who initiated antidepressant therapy were persistent on SSRI or SNRI treatment at 6 months, with younger children and older adults most likely to be persistent. Our estimates of 6-month persistence, which ranged by age group and grace period, are consistent with results from prior studies, 17%–56% (Esposito D et al., 2009; Lu C and Roughead E, 2012; Mullins CD et al., 2005; Richardson LP et al., 2004; Sawada N et al., 2009; Tournier M et al., 2009; Wu C et al., 2012; Wu C et al., 2013; Yau WY et al., 2014). Our ability to predict antidepressant persistence at baseline was modest for both children and adults. However, days without medication between fills and prior persistence on other medications improved our ability to predict persistence. These additional factors could potentially be made available to prescribing physicians at least by the time of a second antidepressant prescription through prescription records to help inform treatment decisions and guide follow-up care.

In the baseline prediction models we identified independent predictors unique to children (i.e. diagnostic code for co-morbid anxiety), predictors that had stronger associations in children than adults (i.e. prior outpatients visits), and factors that were predictors in both children and adults (i.e. code for substance use disorder). Days without antidepressant medication between the first and second fills was one of the strongest predictors in children and adults identified in this study. For adults in the final baseline model, there was not a difference in the likelihood of 6-month persistence for those prescribed an antidepressant by the provider specialty of psychiatry vs. general provider. Our finding for adults is similar to previous findings that a mental health professional vs. general medical provider at initial visit did not predict antidepressant adherence (medication possession ratio ≥75%) in adults with major depression (Akincigil A et al., 2007). However, studies have shown variation by provider in the US, for example the proportion of patients not refilling an antidepressant was higher among primary care providers than psychiatrists, 18% vs. 13%(Bambauer KZ et al., 2007) and 37% vs. 32% (Lewis E et al., 2004). For children, we observed a slight decrease in the likelihood of persistence when the prescribing physician was a family practitioner/general provider.

Although medical practice has the potential to be transformed by big data and software tools that predict the risk of an outcome for a patient, improving the quality and efficiency of medical care (Bates DW et al., 2014; Murdoch TB and Detsky AS, 2013), the promise of successfully integrating these predictive tools has yet to be consistently realized in the case of antidepressant adherence. For example, one study from New England (2002–2004) found that providing real-time fax alerts on delayed antidepressant refills to physicians was not successful in increasing adherence rates (Bambauer KZ et al., 2006). Whereas another study found that using prescription refill records resulted in modest increases in adherence to antidepressants among adults when non-adherent patients and providers of non-adherent patients received educational materials (Hoffman L et al., 2003). Our findings and earlier findings that the refill gap is predictive of antidepressant discontinuation (Hansen RA et al., 2010), suggest future research is warranted to determine an effective and efficient way to incorporate prescription refill information to pharmacists and clinicians to improve antidepressant persistence.

Adherence (proportion of days with medication) to chronic medications has been associated with improved adherence to other treatments among adults (Curtis JR et al., 2009; Platt AB et al., 2010) (Simon GE et al., 2013), including adherence to antidepressants and concurrent adherence to an antihypertensive or lipid-lowering medication. Similarly, in our study adults with prior persistence on other chronic medications were more likely to persist on antidepressant treatment. In adults with both a measure of prior persistence and a measure of days without medication, days without medication offered more improvement in predicting persistence. A useful finding if the prescribing physician does not have information on prior medication use. Still, a benefit of prior persistence on other medications is that it could be obtained prior to beginning antidepressant treatment and possibly by simply asking a patient before prescribing antidepressants if they are still taking their antihypertensive or asthma medications, for example. Improving the prediction of persistence before antidepressant initiation may offer more clinical guidance in treatment type selection and early follow-up care. As only 9% of adults had both measures available, our ability to compare the influence of these two measures was limited.

Overall, our prediction models resulted in low c-statistics (0.57–0.64), revealing a poor ability to discriminate persistent and non-persistent patients. C-statistics predicting antidepressant adherence (medication possession ratio) in claims data have been similar (0.56–0.61) (Akincigil A et al., 2007) or slightly higher (0.71–0.73) (Fontanella CA et al., 2011) than our study, with the higher c-statistics from a study of Medicaid children that included follow-up visits and dosing. These low c-statistics reflect the multitude of factors that influence treatment utilization and the potential predictors available in an administrative claims datasource. Perhaps more important than discrimination is reclassification. Our overall NRIs (9–11) indicate notable improvement in reclassification when adding the measures days without medication and prior persistence on other medications. In the Framingham Heart Study, an additional measure (HDL cholesterol) added to the coronary heart disease risk prediction model resulted in a minimal c-statistic change but an NRI=12, suggesting significant improvement with the additional measure (Pencina MJ et al., 2008). Our reclassification results should be interpreted with caution, as there are no established strata (Cook NR et al., 2006; Leening MJG and Cook NR, 2013) and comparing NRIs across studies with different outcomes and strata may not be meaningful (Leening MJG and Cook NR, 2013; Leening MJG et al., 2014).

Additional limitations should be kept in mind. We cannot identify the reason patients discontinued antidepressants or who initiated the discontinuation (i.e. physician, patient, or caregiver), nor can we distinguish patients who appropriately discontinued from patients who may have benefited from continued antidepressant treatment. Persistence is based on reimbursed, dispensed prescriptions, which is an imperfect proxy for medication consumed, and does not include prescriptions dispensed in-hospital or samples given to the patient at antidepressant initiation or during treatment. Patients receiving antidepressant samples or receiving antidepressants during hospitalization are more likely to be misclassified as non-persistent at 6-months as it would result in inaccurate dispensing dates or days supply values. The prevalence of sample use ranges by drug class and by branded vs. generic products (Hampp C et al., 2015; Li X et al., 2014). While there are not estimates of antidepressant sample use in our population, available estimates of sample use include 14% of patients with some prescription use (Alexander GC et al., 2008) and 13% of patients with a prescription for a branded statin (Li X et al., 2014).

Patients with gaps in medication use stretching past the grace period were by definition classified as discontinuers, even if they later continue treatment. This may include patients steadily taking less than the prescribed dose, possibly contributing to the association between antidepressant persistence and days without medication between the first and second fill. Patients dose titrating may have an incorrect initial days supply value, inviting the possibility of misclassifying the gap between prescription fills. Our findings with respect to prior persistence on other chronic medications may have differed if persistence on non-chronic, non-preventative medications had been assessed. Relatedly, prior persistence on other medications could have been affected by MDD symptoms prior to antidepressant initiation. The measure of prior persistence did offer similar predictability among patients with severe depression at antidepressant initiation (inpatient diagnosis or prior suicide attempt) and patients with less severe depression (outpatient diagnosis), results not shown. APA guidelines recommend a minimum treatment length of 5½ months (6–12 weeks to achieve symptom remission followed by 4–9 months); given our 30-day grace period, patients ending treatment at 5½ months would still be considered persistent at 6 months in this study. Ten-percent of patients had an unknown initial dose or provider; baseline models remained the same when excluding these patients.

Conclusion

Consistent with prior literature, we observed low 6-month antidepressant persistence in a population of commercially insured children and adults with MDD. Overall our ability to discriminate between persistent and non-persistent patients at treatment initiation was poor. However, days without medication coverage between fills in children and adults, and prior persistence on other chronic medications in adults, moderately improved our ability to predict antidepressant persistence. These measures could, potentially, be available to clinicians prior to antidepressant initiation or by the time of the second antidepressant fill through prescription refill records. If effectively provided to a provider, these measures might help identify patients with a lower likelihood of antidepressant persistence and thereby contribute to treatment decisions and follow-up care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Stürmer receives investigator-initiated research funding and support as principal investigator (grant R01AG023178) from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health and from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (award 1IP2PI000075-01). Dr. Stürmer does not accept personal compensation of any kind from any pharmaceutical company, although he receives salary support from the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology and from unrestricted research grants from pharmaceutical companies (GlaxoSmithKline, UCB, Merck, AstraZeneca, Amgen) to the department of epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Ms. Bushnell receives support from the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology.

Role of funding source

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from the following IMS Health Incorporated information service(s): LifeLink® Information Assets-Health Plan Claims Database (1997–2010), IMS Health Incorporated. All Rights Reserved. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not necessarily those of IMS Health Incorporated or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

Sources of financial and material support

Dr. Miller, Dr. Azrael, Ms. Pate, and Dr. Stürmer received support for this work from an investigator-initiated research grant (R01MH085021) from the National Institute of Mental Health (principal investigator, Miller), Bethesda, MD.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Authors Dr. Azrael, Dr. Miller, Ms. Pate, Dr. Swanson, and Dr. White report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akincigil A, Bowblis J, Levin C, Walkup J, Jan S, Crystal S. Adherence to antidepressant treatment among privately insured patients diagnosed with depression. Med Care. 2007;45:363–369. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254574.23418.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GC, Zhang J, Basu A. Characteristics of patients receiving pharmaceutical samples and association between sample receipt and out-of-pocket prescription costs. Med Care. 2008;46:394–402. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181618ee0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd. American Psychiatric Association Arlington (VA); 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assayag J, Forget A, Kettani F, Beauchesne M, Moisan J, Blais L. The impact of the type of insurance plan on adherence and persistence with antidepressants: A matched cohort study. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:233–239. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambauer KZ, Adams AS, Zhang F, Minkoff N, Grande A, Weisblatt R, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Physician Alerts to Increase Antidepressant Adherence: Fax or Fiction? Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:498–504. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambauer KZ, Soumerai SB, Adams AS, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Provider and patient characteristics associated with antidepressant nonadherence: the impact of provider specialty. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:867–873. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DW, Saria S, Ohno-Machado L, Shah A, Escobar G. Big data in health care: using analytics to identify and manage high-risk and high-cost patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1123–1131. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Ministry of Health. Major depressive disorder in adults: Diagnosis & management, BC Guidelines and Protocols 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Bull SA, Hu XH, Hunkeler EM, Lee JY, Ming EE, Markson LE, Fireman B. Discontinuation of Use and Switching of Antidepressants. JAMA. 2002;288:1403. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.11.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook NR. Use and Misuse of the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve in Risk Prediction. Circulation. 2007;115 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook NR. Statistical Evaluation of Prognostic versus Diagnostic Models: Beyond the ROC Curve. Clin Chem. 2008;54:17–23. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.096529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook NR, Buring JE, Ridker PM. The Effect of Including C-Reactive Protein in Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Models for Women. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:21–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Xi J, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Lyles K, Saag KG, Delzell E. Improving the Prediction of Medication Compliance: The Example of Bisphosphonates for Osteoporosis. Med Care. 2009;47:334–341. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818afa1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja AS, Valuck R. Off-label antidepressant use in children and adolescents compared with young adults: extent and level of evidence. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:997–1004. doi: 10.1002/pds.3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito D, Wahl P, Daniel G, Stoto M, Erder M, Croghan T. Results of a retrospective claims database analysis of differences in antidepressant treatment persistence associated with escitalopram and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the United States. Clin Ther. 2009;31:644–656. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanella CA, Bridge JA, Marcus SC, Campo JV. Factors Associated with Antidepressant Adherence for Medicaid-Enrolled Children and Adolescents. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:898–909. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller DA, March J, AACAP Committee on Quality Issues Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:98–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampp C, Greene P, Pinheiro SP. Use of Prescription Drug Samples in the United States and Implications for Pharmacoepidemiologic Studies. 31st International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management; Boston, MA USA. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The Meaning and Use of the Area under a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D, Vach W, Rosholm J, Søndergaard J, Gram L, Kragstrup J. Early discontinuation of antidepressants in general practice: association with patient and prescriber characteristics. Fam Pract. 2004;21:623–629. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen RA, Dusetzina SB, Dominik RC, Gaynes BN. Prescription refill records as a screening tool to identify antidepressant non-adherence. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:33–37. doi: 10.1002/pds.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L, Enders J, Luo J, Segal R, Pippins J, Kimberlin C. Impact of an antidepressant management program on medication adherence. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:70–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMS Health Incorporated. imshealth. 2015 http://www.imshealth.com/, pp. Accessed: January 3, 2016.

- Kennedy SH, Lam RW, Parikh SV, Patten SB, Ravindran AV. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. J Affect Disord. 2009;117 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leening MJG, Cook NR. Net reclassification improvement: a link between statistics and clinical practice. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:21–23. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9759-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leening MJG, Vedder MM, Witteman JCM, Pendna MJ, Steyerberg EW. Net Reclassification Improvement: Computation, Interpretation, and Controversies: A Literature Review and Clinician’s Guide. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:122–131. doi: 10.7326/M13-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis E, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Druss BG, Pincus HA. Patients’ early discontinuation of antidepressant prescriptions. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:494. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ. An Introduction to Classification and Regression Tree (CART) Analysis. Annual Meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine; San Francisco, California. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Stürmer T, Brookhart MA. Evidence of sample use among new users of statins: implications for pharmacoepidemiology. Med Care. 2014;52:773–780. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Roughead E. New users of antidepressant medications: first episode duration and predictors of discontinuation. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milea D, Verpillat P, Guelfucci F, Toumi M, Lamure M. Prescription patterns of antidepressants: Findings from a US claims database. Current Medical Research And Opinion. 2010;26:1343–1353. doi: 10.1185/03007991003772096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Pate V, Swanson SA, Azrael D, White A, Stürmer T. Antidepressant class, age, and the risk of deliberate self-harm: A propensity score matched cohort study of SSRI and SNRI users in the USA. CNS Drugs. 2014a;28:79–88. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0120-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Swanson SA, Deborah Azrael, Pate V, Stürmer T. Antidepressant dose, age, and the risk of deliberate self-harm. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014b;174:899–909. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins CD, Shaya FT, Meng F, Wang J, Harrison D. Persistence, switching, and discontinuation rates among patients receiving Sertraline, Paroxetine, and Citalopram. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:660–667. doi: 10.1592/phco.25.5.660.63590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch TB, Detsky AS. The inevitable application of big data to health care. JAMA. 2013;309:1351–1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Depression: Management of depression in primary and secondary care. National Clinical Practice Guideline Number. 2005:23. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) Depression in children and young people: Identification and management in primary, community, and secondary care. British Psychological Society; Leicester (UK): 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: The treatment and management of depression in adults. NICE clinical guideline. 2009:90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt DJ, Davidson JRT, Gelenberg AJ, Higuchi T, Kanba S, Karamustafalıoğlu O, Papakostas GI, Sakamoto K, Terao T, Zhang M. International consensus statement on major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:e08. doi: 10.4088/JCP.9058se1c.08gry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, D’Agostino SB, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt AB, Kuna ST, Field SH, Chen Z, Gupta R, Roche DF, Christie JD, Asch DA. Adherence to Sleep Apnea Therapy and Use of Lipid-Lowering Drugs: A Study of the Healthy-User Effect. Chest. 2010;137:102–108. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LP, DiGiuseppe D, Christakis DA, McCauley E, Katon W. Quality of care for medicaid-covered youth treated with antidepressant therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:475–480. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Paynter NP, Rifai N, Gaziano MJ, Cook NR. C-Reactive Protein and Parental History Improve Global Cardiovascular Risk Prediction: The Reynolds Risk Score for Men. Circulation. 2008 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada N, Uchida H, Suzuki T, Watanabe K, Kikuchi T, Handa T, Kashima H. Persistence and compliance to antidepressant treatment in patients with depression: A chart review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Peterson D, Hubbard R. Is treatment adherence consistent across time, across different treatments and across diagnoses? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau T, Atkinson B, Ripley B. An Introduction to Recursive Partitioning Using the RPART Routines 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Tournier M, Moride Y, Crott R, Galbaud du Fort G, Ducruet T. Economic impact of non-persistence to antidepressant therapy in the Quebec community-dwelling elderly population. J Affect Disord. 2009;115:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valuck RJ, Libby AM, Orton HD, Morrato EH, Allen R, Baldessarini RJ. Spillover effects on treatment of adult depression in primary care after FDA advisory on risk of pediatric suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1198–1205. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, Dobbels F, Fargher E, Morrison V, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M, Mshelia C, Clyne W, Aronson JK, Urquhart J. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:691–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Erickson S, Piette J, Balkrishnan R. The association of race, comorbid anxiety, and antidepressant adherence among Medicaid enrollees with major depressive disorder. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Shau W, Chan H, Lai M. Persistence of antidepressant treatment for depressive disorder in Taiwan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau WY, Chan MC, Wing YK, Lam HB, Lin W, Lam SP, Lee CP. Noncontinuous use of antidepressant in adults with major depressive disorders – a retrospective cohort study. Brain Behav. 2014;4:390–397. doi: 10.1002/brb3.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.