Abstract

Objective

Prior research evaluated various effects of the antidepressant black-box warning on the risk of suicidality in children, but the dosing of antidepressants has not been considered. This study estimated, relative to the FDA warnings, whether the initial antidepressant dose prescribed decreased and the proportion augmenting dose on the second fill increased.

Method

The study utilized the LifeLink Health Plan Claims Database. The study cohort consisted of commercially insured children (5–17 years), young adults (18–24 years), and adults (25–64 years) initiating an SSRI (citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or sertraline) from 1/1/2000 to 12/31/2009. Dose-per-day was determined by days supply, strength, and quantity dispensed. Initiation on low dose, defined based on guidelines, and dose augmentations (dose increase >1mg/day) on the second prescription were considered across time periods related to the antidepressant warnings.

Results

Of 51,948 children who initiated an SSRI, 15% initiated on low dose in the period before the 2004 black-box warning and 31% in the period after the warning (a 16 percentage-point change); there was a smaller percentage-point change in young adults (6%) and adults (3%). The overall increase in dose augmentations in children and young adults was driven by the increase in patients initiating on a low dose.

Conclusions

As guidelines recommend children initiate antidepressant treatment on low dose, findings that an increased proportion of commercially insured children initiated an SSRI on low dose after the 2004 black-box warning suggest prescribing practices surrounding SSRI dosing improved in children following the warning but dosing practices still fall short of guidelines.

Introduction

In June 2003, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a public health advisory recommending that children treated for major depressive disorder (MDD) should not be given paroxetine because it might increase suicidal thoughts and behaviors (1). In October 2004, the FDA added a black-box warning to all antidepressants(2) based on an FDA sponsored meta-analysis that found children randomized to antidepressants had twice the rate of suicidal ideation and behavior compared with children randomized to placebo (3, 4). Based on additional analyses, the black-box warning was expanded in May 2007 to include patients ages 18–24 years (5). The warnings included recommendations for close patient monitoring after antidepressant initiation (2).

Following the black-box warning, antidepressant use overall decreased in youth,(6–16) paroxetine use decreased,(7, 11, 14) and fluoxetine use increased (11, 15). Other studies have documented shifted care from generalists to psychiatric specialists,(6, 8, 17) and a decrease in new pediatric depression diagnoses (9, 10). Recommendations for improved patient monitoring did not lead to significant changes in visit frequency after antidepressant initiation(11, 18), although physicians reported increased patient contact with antidepressant initiators after the warnings (8, 17).

In 2007, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) practice parameters stated that children and adolescents with depressive disorders should initiate antidepressant treatment on a low dose (19). Prescribing guidelines from non-US countries, published as early as 2005, also suggest initiating selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) in children (20, 21), as well as adults (22, 23), at low doses with gradual dose titration as evidence suggests antidepressant side effects may be dose related (24–26). Higher initial antidepressant dose may be associated with an increased risk of self-harm in children and young adults (10–24 years)(27, 28) highlighting the potential importance of initiating therapy at lower doses, especially among children and young adults. Despite these recommendations, it is uncertain whether starting lower and slowly titrating upward has become a more frequent antidepressant treatment strategy, and if so, whether changes in prescribing practices have been more pronounced among children than adults.

To our knowledge the only published assessment of whether the black box warnings affected prescriber management of antidepressants through dose alterations was a survey of practicing pediatricians in Canada, 11% of whom reported that the black-box warning affected their management of depression through medication dosing (29). The current study examines directly whether, in relation to FDA actions, US prescribers may have begun to exert extra caution that influenced initial dosing and subsequent dose titration, especially among children and young adults. We do so by assessing if the initial SSRI dose-per-day prescribed decreased relative to the FDA black-box warnings, and also whether the proportion of children and young adults augmenting SSRI dose on the second fill increased.

Methods

Datasource & Study Population

We used the LifeLink Health Plan Claims Database, purchased from IMS Health, which contains data from over 98 health plans throughout the US. The database includes International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) inpatient and outpatient diagnoses, Current Procedural Terminology, 4th edition (CPT-4) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) procedure codes, and records for reimbursed, dispensed retail and mail order prescriptions. Records of dispensed prescriptions include the National Drug Code (NDC), quantity, days supply, and date of dispensing. The study was exempted from the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board.

The study population consisted of commercially insured individuals initiating SSRI treatment between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2009. Children (5–17 years), young adults (18–24 years), and, for comparison, adults (25 to 64 years) were included. SSRIs were limited to citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline; escitalopram was excluded, as it was not FDA approved until late 2002, and therefore no reference of dosing before the warnings was available. Eligibility criteria further included: at least a year of insurance coverage prior to SSRI initiation; no record of antidepressant use in the prior year; 6 months of insurance coverage following the initial prescription to help ensure capture of a second prescription; and a valid initial dose-per-day as defined subsequently.

Dose-per-day & Dose augmentations

For each SSRI prescription, dose-per-day was calculated based on the days supply, strength (from NDC code), and quantity dispensed (11,704 patients were excluded due to missing values; 2.2% of the study population). We excluded 3,151 patients (0.6%) with amount-per-day values (quantity dispensed divided by days supply) outside of 0.5 to 4.0 pills-per-day for SSRIs dispensed in tablet form and outside 0.25ml to 20ml for solution form or initial dose-per-day values <2.5mg/d or values 1.5 times the recommended maximum therapeutic dose-per-day (citalopram >60mg/d, fluoxetine >120mg/d, paroxetine controlled release (CR) >93.75mg/d, paroxetine immediate release (IR) >90mg/d, and sertraline >300mg/d).

We defined low dose by age group and SSRI agent based on available guidelines and product labels (22, 23, 30–38): 5–12 years (<10mg/d citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine IR and <25mg/d sertraline), 13–17 years (<20mg/d citalopram and fluoxetine, <10mg/d paroxetine IR, and <50mg/d sertraline), and 18–64 years (<20mg/d citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine IR, <25mg/d paroxetine CR, and <50mg/d sertraline). Paroxetine CR was unavailable <12.5mg/d for children 5–17 years. As paroxetine was the only agent in which the low dose value for children 13–17 years differed from young adults, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using an alternative definition for low dose paroxetine (IR: <20mg/d, CR: <25mg/d) in children 13–17 years.

Dose augmentation was defined as an increase of >1mg/d between the initial dose-per-day and the dose-per-day of the second prescription. To be eligible for a dose augmentation, patients had to fill a second prescription for the same agent within the initial prescription’s days supply plus a 30-day grace period. One-percent (n=5,625) of the study population filled two prescriptions of the same SSRI at treatment initiation; we assumed the two prescriptions were taken sequentially as the median days supply for patients with two different doses, was 7 days (interquartile range: 7, 15) for the lower dose and 30 days (30, 30) for the higher dose. Therefore, if the dose-per-day values at index differed, the lower dose was considered the initial dose-per-day and the higher dose the dose of the second prescription.

Time Periods

Patients were stratified by date of antidepressant initiation into time periods related to three historically relevant dates (Appendix figure 1). Period 1, before heightened concerns, included the time from 1/1/2000 to 6/18/2003. Period 1 was further divided into two time periods (1/1/2000–12/31/2001 and 1/1/2002–6/18/2003) to determine if dosing was stable in the years preceding heightened concerns. Period 2 began on 6/19/2003 when the FDA recommended that paroxetine not be used in children for the treatment of MDD. Period 3 began on 10/15/2004 when the black-box warning for children <18 years was announced. Period 4 began on 5/2/2007 when the black-box warning was expanded to ages 18–24 years, and went until study end (12/31/2009). Primary comparisons considered initiation before (1/1/2000–10/14/2004) versus after the 2004 FDA black-box warning (10/15/2004–12/31/2009). For young adults an additional comparison was considered for before (1/1/2000–5/1/2007) versus after the black-box expansion (2/2/2007–12/31/2009).

Covariates

Baseline patient covariates were collected in the year prior to treatment initiation. Covariates of primary interest included age at treatment initiation, index antidepressant agent, provider specialty, and depression diagnosis. Age categories within children (5–9, 10–12, 13–17) were created based on potential variation in dosing and prescribing practices. Provider specialty was the specialty associated with the index antidepressant prescription; specialties of interest were psychiatry, psychology, and general practice (pediatrics, family practice, and general practice). The remaining specialties were classified as other or unknown if missing. A depression diagnosis was defined as an inpatient or outpatient diagnostic code (ICD-9-CM code 296.2x, 296.3x, 298.0x, 300.4x, 309.0x, 309.1x, 311.xx, 293.83, 296.90, 309.28) in the prior year. Additional covariates describe the study cohort (Table 1, footnote).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of children, young adults, and adults initiating SSRI treatmenta

| Children 5–17 yearsb (n=51,948) |

Young adults 18–24 years (n=51,653) |

Adults 25–64 years (n=395,550) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Time period of treatment initiation | ||||||

| Period 1: January 1, 2000 to June 18, 2003c | 9,829 | 19 | 8,531 | 17 | 72,426 | 18 |

| Period 2: June 19, 2003 to October 14, 2004 | 4,826 | 9 | 4,248 | 8 | 34,996 | 9 |

| Period 3: October 15, 2004 to May 1, 2007 | 14,719 | 28 | 15,145 | 29 | 109,814 | 28 |

| Period 4: May, 2, 2007 to Dec. 31, 2009 | 22,574 | 43 | 23,729 | 46 | 178,314 | 45 |

| Female | 28,913 | 56 | 34,753 | 67 | 268,820 | 68 |

| SSRI agent | ||||||

| Citalopram | 8,042 | 15 | 12,579 | 24 | 98,296 | 25 |

| Fluoxetine | 18,358 | 35 | 12,867 | 25 | 88,045 | 22 |

| Paroxetine | 5,929 | 11 | 8,678 | 17 | 77,071 | 19 |

| Sertraline | 19,619 | 38 | 17,529 | 34 | 132,138 | 33 |

| Provider specialty | ||||||

| Psychiatry | 10,876 | 21 | 5,240 | 10 | 20,848 | 5 |

| Psychology | 3,046 | 6 | 1,485 | 3 | 7,827 | 2 |

| General practice | 17,855 | 34 | 18,871 | 37 | 113,066 | 29 |

| Other | 12,095 | 23 | 15,487 | 30 | 144,792 | 37 |

| Unknown | 8,076 | 16 | 10,570 | 20 | 109,017 | 28 |

| Depression severity | ||||||

| Primary inpatient diagnosis ≤30 days pre-initiation | 1,366 | 3 | 572 | 1 | 1,075 | 0 |

| Primary inpatient diagnosis 31–360 days pre-initiation | 243 | 0 | 139 | 0 | 287 | 0 |

| Non-primary inpatient diagnosis | 675 | 1 | 505 | 1 | 3,198 | 1 |

| ≥2 outpatient diagnoses | 14,846 | 29 | 12,415 | 24 | 66,567 | 17 |

| 1 outpatient diagnosis | 7,912 | 15 | 9,821 | 19 | 60,610 | 15 |

| No depression diagnosis | 25,906 | 50 | 28,201 | 55 | 263,813 | 67 |

| Suicide attempt | 458 | 1 | 303 | 1 | 355 | 0 |

| Bipolar disorder | 1,454 | 3 | 1,109 | 2 | 4,121 | 1 |

| ADHD | 11,186 | 22 | 2,958 | 6 | 3,611 | 1 |

| Anxiety | 15,012 | 29 | 14,659 | 28 | 87,061 | 22 |

| Substance use disorder | 1,957 | 4 | 4,072 | 8 | 26,135 | 7 |

| Psychiatric hospitalization, prior year (1+) | 1,791 | 3 | 842 | 2 | 1,826 | 0 |

| Non-psychiatric hospitalization, prior year (1+) | 2,066 | 4 | 4,299 | 8 | 44,121 | 11 |

| Outpatient visits, prior year | ||||||

| < 5 | 12,914 | 25 | 15,143 | 29 | 94,496 | 24 |

| 5 – 9 | 14,313 | 28 | 14,520 | 28 | 95,330 | 24 |

| 10 – 19 | 15,178 | 29 | 13,843 | 27 | 110,316 | 28 |

| ≥ 20 | 9,543 | 18 | 8,147 | 16 | 95,408 | 24 |

| Generic prescription drug count, prior year | ||||||

| None | 8,567 | 17 | 6,538 | 13 | 34,818 | 9 |

| 1 – 2 | 17,534 | 34 | 14,151 | 27 | 87,098 | 22 |

| 3 – 4 | 11,882 | 23 | 11,706 | 23 | 80,517 | 20 |

| ≥ 5 | 13,965 | 27 | 19,258 | 37 | 119,960 | 30 |

| High-potency prescription opiate usage | 163 | 0 | 488 | 1 | 6,789 | 2 |

| Mid-potency prescription opiate usage | 6,230 | 12 | 13,814 | 27 | 119,960 | 30 |

| Cancer | 288 | 1 | 321 | 1 | 17,208 | 4 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 866 | 2 | 1,027 | 2 | 16,169 | 4 |

| Diabetes | 462 | 1 | 681 | 1 | 32,116 | 8 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 109 | 0 | 169 | 0 | 8,564 | 2 |

| Cluster headaches/migraines | 1,566 | 3 | 2,099 | 4 | 16,088 | 4 |

| Seizures | 572 | 1 | 379 | 1 | 2,421 | 1 |

Patient characteristics collected in the year prior to SSRI initiation. Healthcare utilization measures included the number of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and prescription medications in the prior year. Prior suicide attempt was defined with external cause of injury codes (E950.x–E959.x) and mid- and high-potency opiate prescriptions were defined based on National Drug Code. Psychiatric and non-psychiatric morbidities that were prevalent in all age groups were used to help describe the health status of the study cohort and were defined with ICD-9-CM codes: bipolar disorder (296.4–296.9), ADHD (314.x), anxiety disorder (300.0, 300.2, 300.3), substance use disorder (291.x, 292.x, 303.x–305.x), cancer (140.x–209.x), cardiac arrhythmia (427.x), diabetes (250.x), cerebrovascular disease (430.x–438.x), cluster headaches/migraines (346.x), and seizures (345.x). The hierarchical measure of depression severity included 5 levels for patients with at least 1 depression diagnosis: a primary (first listed) inpatient depression diagnosis ≤30 days prior to SSRI initiation (most severe) or 31–360 days, a non-primary inpatient depression diagnosis, 2+ outpatient depression diagnoses in the year prior to SSRI initiation, and 1 outpatient depression diagnosis (least severe).

5–9 years (n=6,776), 10–12 years (n=9,175), 13–17 years (n=35,997)

Period 1a: 5–17 years (n=4,678), 18–24 years (n=4,223), 25–64 years (n=35,727)

Analysis

We estimated the proportion of patients initiating on low dose before and after the 2004 FDA black-box warning and the percentage-point change with the associated Wald 95% confidence interval (CI). Results were evaluated by period of initiation and age group and were further stratified by SSRI agent to assess whether variation in prescribing practices around dosing was apparent by agent (paroxetine was associated with the initial heightened warnings and fluoxetine was the only FDA approved SSRI for treatment of MDD in children (1, 4)). Results were also stratified by presence of a depression diagnosis in the year prior to SSRI initiation and by prescribing provider type. Provider specialty stratification was restricted to psychiatry vs. general practice as we cannot be certain of the psychology provider makeup given prescribing rights for psychologists were limited to two states during the study period. Two sensitivity analyses were conducted: one assumed that the 1% of patients who filled two antidepressant prescriptions at initiation took the prescriptions concurrently rather than sequentially (ex. 10+30=40mg vs. 10mg); the other included the 0.6% of patients who were excluded from primary analyses due to initial dose values that were thought to be entry error. Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

Between 2000 and 2009, 51,948 children, 51,653 young adults, and 395,550 adults initiated an SSRI. The majority of children initiated sertraline (38%) or fluoxetine (35%) compared to citalopram (15%) or paroxetine (11%). A psychiatrist wrote the initial prescription for 21% of children, 10% of young adults, and 5% of adults (Table 1). Half of children, 45% of young adults, and 33% of adults had a depression diagnosis in the year prior to SSRI initiation and 29% of children, 28% of young adults, and 22% of adults had an anxiety diagnosis.

Initial dose-per-day

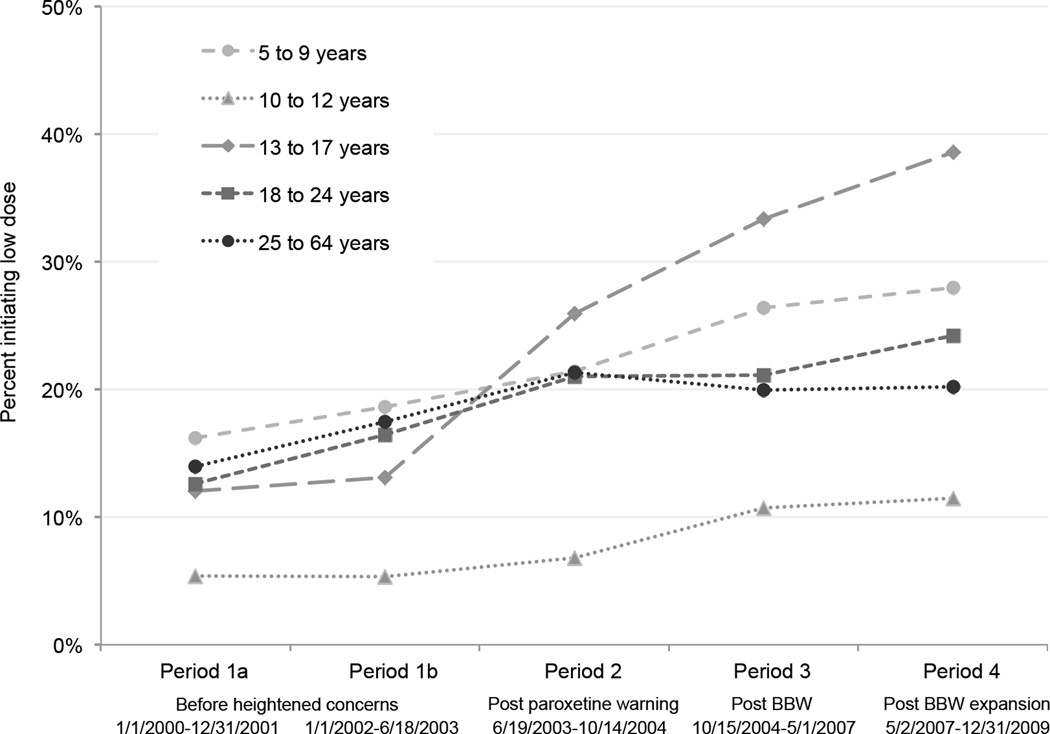

Overall, 25% of children 5–9 years, 10% of children 10–12 years, 31% of children 13–17 years, 21% of young adults, and 19% of adults initiated an SSRI on a low dose. The proportion of patients initiating SSRI treatment on a low dose increased over time (Figure 1). Increases for children 10–12 and 13–17 years began in period 2, the period immediately following the initial paroxetine warning, and continued thereafter. The proportion of the youngest children (5–9 years), young adults, and adults initiating on low dose increased slightly during the initial period; for young adults and adults this stabilized in period 3 and further increased only in young adults after the 2007 black-box expansion.

Figure 1.

Proportion of children, young adults, and adults initiating SSRI treatment on a low dose

BBW = Black-box warning

Low dose = 5–12 years (<10mg/d citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine immediate release and <25mg/d sertraline); 13–17 years (<20mg/d citalopram and fluoxetine, <10mg/d paroxetine immediate release, and <50mg/d sertraline); 18–64 years (<20mg/d citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine immediate release, <25mg/d paroxetine controlled release, and <50mg/d sertraline); Children 5–17 years: paroxetine controlled release unavailable <12.5mg/d

The increase in the proportion initiating on a low dose after the black-box warning compared with prior to the black-box warning was most prominent in children 13–17 years (37% vs. 17%), a relative increase of 116% (Table 2). Results were essentially unchanged in the sensitivity analysis that assumed patients with two index antidepressant prescriptions took them concurrently and in the analysis that included patients with initial dose values that were thought to be from entry error.

Table 2.

The proportion of patients initiating an SSRI on a low dose before and after the 2004 FDA black-box warning

| Pre-2004 FDA warning | Post-2004 FDA warning | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. low dosea |

Proportion initiating on a low dose |

No. low dosea |

Proportion initiating on a low dose |

Percentage- point change |

||||

| Overall | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||

| 5 to 17 years | 2,221 | 15 | 15 – 16 | 11,522 | 31 | 30 – 31 | 16 | 15 – 16 |

| 5 to 9 years | 360 | 19 | 17 – 21 | 1,334 | 27 | 26 – 29 | 8 | 6 – 10 |

| 10 to 12 years | 155 | 6 | 5 – 7 | 729 | 11 | 10 – 12 | 5 | 4 – 7 |

| 13 to 17 years | 1,706 | 17 | 16 – 18 | 9,459 | 37 | 36 – 37 | 20 | 19 – 21 |

| 18 to 24 yearsb | 2,136 | 17 | 16 – 17 | 8,951 | 23 | 23 – 23 | 6 | 6 – 7 |

| 25 to 64 years | 18,849 | 18 | 17 – 18 | 57,959 | 20 | 20 – 20 | 3 | 2 – 3 |

| Depression diagnosisc | ||||||||

| 5 to 17 years | 1,149 | 15 | 14 – 16 | 5,913 | 32 | 32 – 33 | 18 | 17 – 19 |

| 18 to 24 years | 832 | 13 | 13 – 14 | 3,576 | 21 | 20 – 21 | 7 | 6 – 8 |

| 25 to 64 years | 4,827 | 13 | 13 – 14 | 16,456 | 17 | 17 – 18 | 4 | 4 – 4 |

| No depression diagnosis | ||||||||

| 5 to 17 years | 1,072 | 16 | 15 – 16 | 5,609 | 29 | 29 – 30 | 14 | 13 – 15 |

| 18 to 24 years | 1,304 | 20 | 19 – 21 | 5,375 | 25 | 24 – 25 | 5 | 4 – 6 |

| 25 to 64 years | 14,022 | 20 | 19 – 20 | 41,503 | 22 | 21 – 22 | 2 | 1–2 |

| SSRI agent, 5 to 12 years | ||||||||

| Fluoxetine | 129 | 12 | 10 – 14 | 919 | 20 | 19 – 21 | 8 | 6 – 10 |

| Citalopram | 49 | 10 | 8 – 13 | 305 | 20 | 18 – 22 | 10 | 6 – 13 |

| Paroxetine | 172 | 14 | 12 – 16 | 139 | 21 | 17 – 24 | 6 | 3 – 10 |

| Sertraline | 165 | 9 | 8 – 10 | 700 | 15 | 14 – 16 | 6 | 4 – 8 |

| SSRI agent, 13 to 17 years | ||||||||

| Fluoxetine | 853 | 34 | 32 – 36 | 5,134 | 50 | 49 – 51 | 16 | 14 – 18 |

| Citalopram | 198 | 13 | 11 – 15 | 1,465 | 33 | 31 – 34 | 20 | 17 – 22 |

| Paroxetine | 33 | 1 | 1 – 2 | 33 | 2 | 1 – 2 | 0 | 0 – 1 |

| Sertraline | 622 | 17 | 15 – 18 | 2,827 | 30 | 29 – 31 | 14 | 12 – 15 |

| Service provider | ||||||||

| Psychiatry | ||||||||

| 5 to 17 years | 501 | 16 | 15 – 18 | 2,700 | 35 | 33 – 36 | 18 | 16 – 20 |

| 18 to 24 years | 196 | 14 | 12 – 16 | 861 | 22 | 21 – 24 | 8 | 6 – 11 |

| 25 to 64 years | 837 | 13 | 13 – 14 | 2,656 | 18 | 18 – 19 | 5 | 4 – 6 |

| General practiced | ||||||||

| 5 to 17 years | 769 | 15 | 14 – 16 | 3,770 | 29 | 29 – 30 | 14 | 13 – 15 |

| 18 to 24 years | 729 | 16 | 15 – 17 | 3,097 | 22 | 21 – 22 | 6 | 5 – 7 |

| 25 to 64 years | 4,492 | 15 | 15 – 16 | 15,255 | 18 | 18 – 18 | 3 | 2 – 3 |

Low dose=5–12 years (<10mg/d citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine immediate release and <25mg/d sertraline), 13–17 years (<20mg/d citalopram and fluoxetine, <10mg/d paroxetine immediate release, and <50mg/d sertraline), 18–64 years (<20mg/d citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine immediate release, <25mg/d paroxetine controlled release, and <50mg/d sertraline); Children 5–17 years: paroxetine controlled release unavailable <12.5mg/d

For young adults (18–24 years) the proportion initiating on a low dose pre-2007 expansion (period 1–3) was 19.1% and post-2007 expansion (period 4) was 24.2%, a percentage-point change of 5.1% (95% CI: 4.4–5.8)

Depression diagnosis in the year prior to SSRI initiation (ICD-9-CM codes: 296.2x, 296.3x, 298.0x, 300.4x, 309.0x, 309.1x, 311.xx, 293.83, 296.90, and 309.28)

General practice included the service providers pediatrics, family practice, and general practice

The percentage-point change in the proportion initiating on a low dose after the 2004 black-box warning compared with before was more pronounced among those with a depression diagnosis across all age groups: children (18% vs. 14%), young adults (7% vs. 5%), and adults (4% vs. 2%), (Table 2). For children the percentage-point change was higher in those with a service provider from psychiatry (18%), compared with a provider from a general practice (14%).

Among children 13–17 years, the proportion initiating on a low dose differed across agents, ranging from 2% among paroxetine initiators to 47% among fluoxetine initiators, with much less variation by agent seen in children 5–12 years (13–19%). However, in the sensitivity analysis for children 13–17 years, with an alternative low dose definition for paroxetine (IR: <20mg/d, CR: <25mg/d), 39% initiated on a low paroxetine dose before the 2004 warning and 52% after the warning. Considering all agents for children 13–17 years with the alternative paroxetine low dose definition, the percentage-point change was 15% (95% CI: 14–16): 25% before the warning to 40% after.

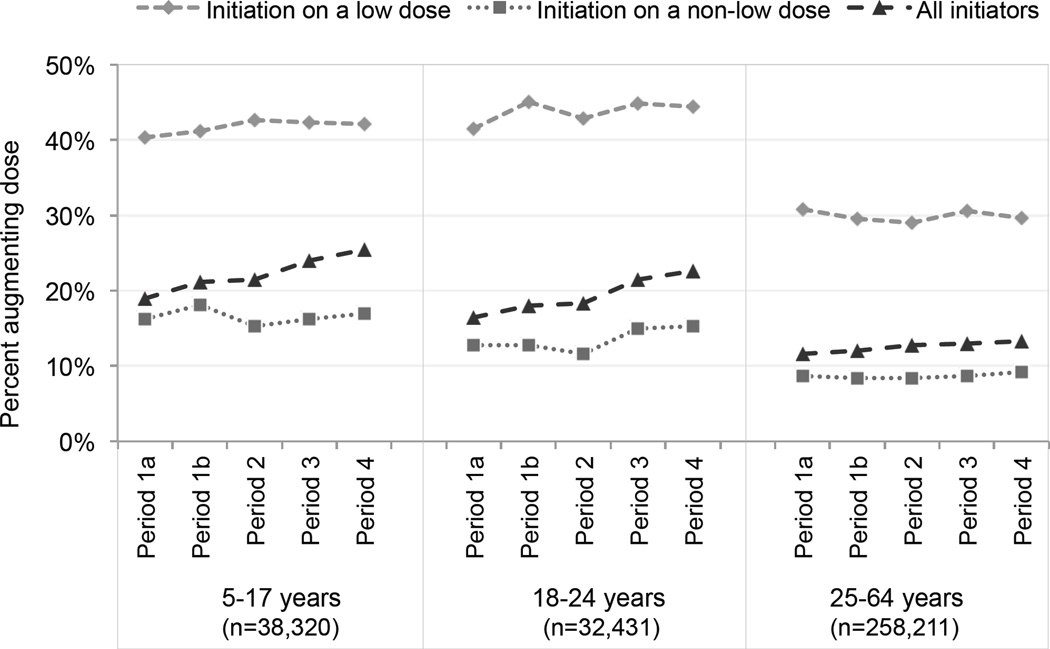

Dose augmentation

Overall, 74% of children (range across four periods: 73–74%), 63% of young adults (range: 62–65%), and 65% of adults (range: 64–69%) filled a second SSRI prescription for the same agent. Of those with a second prescription, 20% of children 5–9 years (980/4,972), 21% of children 10–12 years (1,530/7,158), 25% of children 13–17 years (6,538/26,190), 21% of young adults (6,809/32,431), and 13% of adults (33,262/258,211) augmented dose. Patients initiating on a low dose were more likely to subsequently augment dose compared to non-low dose initiators (Figure 2). Stratified by initial dose, the proportion of patients augmenting dose on the second fill remained stable across the four time periods (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of children, young adults, and adults augmenting SSRI dose on the second fill

Discussion

Overall, we saw an increase in the proportion of children and young adults initiating an SSRI on a low dose in the period after the 2004 black-box warning, compared with the period before the warning, with minimal changes in adults. The change in prescribing practices surrounding dosing was not universal, as the majority of children were not initiated on a low dose by study end. The black-box warning did not mention dosing, however, and warnings with specific reference to dosing might have a larger impact on dose-related prescribing practices. The increased proportion of children and young adults augmenting dose on the second fill after the 2004 warning was accounted for by the increase in low dose initiators.

The largest increase in the proportion initiating on a low dose after the 2004 black-box warning occurred among children 13–17 years. This may be a result of increased concern about suicidal outcomes among this age group relative to younger children, as intentional self-harm is more common in this age group (39, 40). Our finding that a lower proportion of children 10–12 years, compared with other child age groups, initiated treatment on a low dose (10% vs. 25–31%) is likely due to our definition of low dose for citalopram, fluoxetine, and sertraline changing for children when they turn 13 (i.e., higher doses constituted ‘low dose’). The oldest children in the group aged 5–12 years are more likely to initiate on a dose that would be considered low dose for children aged 13–17 years, but considered a non-low dose for children 5–12 years.

The change in the proportion of children initiating treatment on a low dose was slightly more pronounced for children prescribed antidepressants by psychiatrists compared to those prescribed by general practitioners, which may be a result of differential familiarity with treatment guidelines, the black-box warnings, or SSRIs themselves. Our finding that the proportion initiating on a low dose varies by SSRI agent may in part be due to the definition of low dose we used in primary analyses, but may also be related to variation in drug formulations that make it harder to prescribe lower doses, e.g., paroxetine CR is not available in <12.5mg/d. Given the availability of paroxetine IR and other SSRIs, low doses of other SSRIs could have been prescribed if desired.

The official announcement on the decision to add the black-box warning to all antidepressants was made more than one year after the FDA issued their initial warning on the possible increased suicidality risk with paroxetine. The interval between the initial warning (June 2003) and the formal black box warning (October 2004) was marked by media coverage on the risk of suicidality associated with pediatric antidepressant use (41). Consistent with prior research that describes decreases in antidepressant prescribing beginning before the 2004 warning (6, 7, 11, 14, 15), we observed a change in prescribing practices during this time. The change was most pronounced in children 13–17 years, where the proportion of patients initiating on low dose was stable during period 1 and then doubled after the paroxetine warning.

The black-box warning did not expand to patients 18–24 years of age until 2007. The proportion of patients 18–24 years initiating on a low dose stabilized when the 2004 black-box warning for children (<18 years) was released but increased after the warning was expanded to patients 18–24 years. The changes we observed in the proportion of patients initiating on low dose therapy in period 2 suggest that the initial warnings for children might have influenced prescribing among the 18–24 year old age group. In adults (25–64 years) as well, to whom neither black-box warning pertained, there was a similar increase in the proportion initiating on a low dose in period 2. These findings of increases after the paroxetine warnings may be consistent with spillover effects that have been observed previously (42). For example, following a 2005 black-box warning regarding the risk of atypical antipsychotic use among elderly patients with dementia, modest decreases in use were also seen among those without dementia (43). Comparatively, substantial decreases in antidepressant prescribing among children related to FDA communications (6, 7, 10, 14, 15, 18, 44, 45) were accompanied by modest decreases among adults (6, 14).

Limitations of our study should be considered. The population of antidepressant initiators increased across the study, which is a function of the datasource increasing in size; consequently, proportions are weighted towards the end of each period. Dose values were dependent on correct data entry in dispensed prescription records and free samples may have been provided to the patient at treatment initiation, possibly resulting in misclassification of the initial dose. We would not, however, expect these sources of misclassification to differentially affect children and adults across the time periods. Results are limited to patients with continuous insurance enrollment who initiated citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or sertraline and had a non-missing dose. Lastly, the working definition we adopted for initiation on a low dose was based on available product labels and guidelines, and did not account for treatment indications or patient weight.

Conclusions

Results from this descriptive study indicate that the proportion of children initiating on a low dose increased after the 2004 FDA warning on the risk of suicidality in children. The increase in children starting on a low dose was apparent after the initial advisory in 2003. Given recent findings that the dose of the antidepressant may be associated with an increased risk of self-harm,(27, 28) as well as AACAP guidelines indicating that children and adolescents with depressive disorders should initiate antidepressant treatment on a low dose,(19) our results suggest prescribing practices surrounding SSRI dosing improved in children following the black-box warnings but dosing practices still fall short of guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Stürmer, Dr. Azrael, Ms. Pate, and Dr. Miller received support for this work from an investigator-initiated research grant (RO1MH085021) from the National Institute of Mental Health (principal investigator, Dr. Miller). The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from the following IMS Health Incorporated information service(s): LifeLink® Information Assets-Health Plan Claims Database (1997–2010), IMS Health Incorporated. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not necessarily those of IMS Health Incorporated or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

Ms. Bushnell receives support from the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology and holds a part-time graduate research assistantship with GlaxoSmithKline with work unrelated to this project. Dr. Stürmer receives investigator-initiated research funding and support as principal investigator (grant R01 AG023178) from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health and from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (award 1IP2PI000075-01). Dr. Stürmer also receives research funding as principal investigator from AstraZeneca and Merck, Inc. Dr. Stürmer does not accept personal compensation of any kind from any pharmaceutical company, although he receives salary support from the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology and from unrestricted research grants from pharmaceutical companies (GlaxoSmithKline, UCB, Merck) to the Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Footnotes

Authors Dr. Miller, Dr. Swanson, Ms. Pate, Dr. White, and Dr. Azrael report no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Temple R. Anti-depressant drug use in pediatric populations: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA launches a multi-pronged strategy to strengthen safeguards for children treated with antidepressant medications; in Press Announcements. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leslie LK, Newman TB, Chesney PJ, et al. The Food and Drug Administration’s deliberations on antidepressant use in pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2005;116:195–204. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:332–339. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone M, Laughren T, Jones ML, et al. Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration. British Medical Journal. 2009;339:b2880. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nemeroff CB, Kalali A, Keller MB, et al. Impact of publicity concerning pediatric suicidality data on physician practice patterns in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:466–472. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss BG. Effects of Food and Drug Administration warnings on antidepressant use in a national sample. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM, Beebe TJ, et al. Impact of the FDA black box warning on physician antidepressant prescribing and practice patterns: Opening pandora’s suicide box. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2007;82:516–522. doi: 10.4065/82.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libby AM, Brent DA, Morrato EH, et al. Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:884–891. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libby AM, Orton HD, Valuck RJ. Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:633–639. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busch SH, Frank RG, Leslie DL, et al. Antidepressants and suicide risk: how did specific information in FDA safety warnings affect treatment patterns? Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:11–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, et al. Early evidence on the effects of regulators’ suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1356–1363. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busch SH, Frank RG, Martin A, et al. Characterizing declines in pediatric antidepressant use after new risk disclosures. Medical Care Research and Review. 2011;68:96–111. doi: 10.1177/1077558710374197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pamer CA, Hammad TA, Wu Y, et al. Changes in US antidepressant and antipsychotic prescription patterns during a period of FDA actions. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2010;19:158–174. doi: 10.1002/pds.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurian BT, Ray WA, Arbogast PG, et al. Effect of regulatory warnings on antidepressant prescribing for children and adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:690–696. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DePetris AE, Cook BL. Differences in diffusion of FDA antidepressant risk warnings across racial-ethnic groups. Psychiatric Services. 2013;64:466–471. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatia SK, Rezac AJ, Vitiello B, et al. Antidepressant prescribing practices for the treatment of children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2008;18:70–80. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrato EH, Libby AM, Orton HD, et al. Frequency of provider contact after FDA advisory on risk of pediatric suicidality with SSRIs. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:42–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birmaher B, Brent D AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1503–1526. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garland EJ, Kutcher S, Virani A. 2008 position paper on using SSRIs in children and adolescents. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;18:160–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists: Clinical guidance on the use of antidepressant medications in children and adolescents: March 2005. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nutt DJ, Davidson JRT, Gelenberg AJ, et al. International consensus statement on major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71:e08. doi: 10.4088/JCP.9058se1c.08gry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safer DJ, Zito JM. Treatment-emergent adverse events from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors by age group: Children versus adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2006;16:159–169. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emslie G, Kratochvil C, Vitiello B, et al. Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): Safety results. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1440–1455. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000240840.63737.1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung AH, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. Review of the efficacy and safety of antidepressants in youth depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:735–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller M, Swanson SA, Azrael Deborah, et al. Antidepressant dose, age, and the risk of deliberate self-harm. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174:899–909. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brent DA, Gibbons R. Initial dose of antidepressant and suicidal behavior in youth start low, go slow. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174:909–911. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheung A, Sacks D, Dewa CS, et al. Pediatric prescribing practices and the FDA black-box warning on antidepressants. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2008;29:213–215. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31817bd7c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:98–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) Depression in children and young people: Identification and management in primary, community, and secondary care. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.British Columbia Ministry of Health: Major depressive disorder in adults: Diagnosis & management. BC Guidelines and Protocols. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 33.British Columbia Ministry of Health. Anxiety and depression in children and youth – diagnosis and treatment. British Columbia Guidelines. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prozac [package insert] Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zoloft [package insert] New York, NY: Pfizer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Celexa [package insert] St Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paxil [package insert] Mississauga, Ontario: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paxil CR [package insert] Mississauga, Ontario: GlaxoSmithKline; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39.British Columbia Injury Research and Prevention Unit: BCIRPU online data tool. http://www.injuryresearch.bc.ca/ [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS) 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

- 41.Barry CL, Busch SH. News coverage of FDA warnings on pediatric antidepressant use and suicidality. Pediatrics. 2009;125:88–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dusetzina SB, Higashi AS, Dorsey ER, et al. Impact of FDA drug risk communications on health care utilization and health behaviors: A systematic review. Medical Care. 2012;50:466–478. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorsey ER, Rabbani A, Gallagher SA, et al. Impact of FDA black box advisory on antipsychotic medication use. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170:96–103. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forrester MB. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor warnings and trends in exposures reported to poison control centres in Texas. Public Health. 2008;122:1356–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh T, Prakash A, Rais T, et al. Decreased use of antidepressants in youth after US Food and Drug Administration black box warning. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2009;6:30–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.