Abstract

The filamentous fungi Phaeoacremonium aleophilum (P.al, Teleomorph: Togninia minima) and Phaeomoniella chlamydospora (P.ch) are believed to be causal agents of wood symptoms associated with the Esca associated young vine decline. The occurrence of these diseases is dramatically increasing in vineyards all over the world whereas efficient therapeutic strategies are lacking. Both fungi occupy the same ecological niche within the grapevine trunk. We found them predominantly within the xylem vessels and surrounding cell walls which raises the question whether the transcriptional response towards plant cell secreted metabolites is comparable. In order to address this question we co-inoculated grapevine callus culture cells with the respective fungi and analyzed their transcriptomes by RNA sequencing. This experimental setup appears suitable since we aimed to investigate the effects caused by the plant thereby excluding all effects caused by other microorganisms omnipresent in planta and nutrient depletion. Bioinformatics analysis of the sequencing data revealed that 837 homologous genes were found to have comparable expression pattern whereas none of which was found to be differentially expressed in both strains upon exposure to the plant cells. Despite the fact that both fungi induced the transcription of oxido- reductases, likely to cope with reactive oxygen species produced by plant cells, the transcriptomics response of both fungi compared to each other is rather different in other domains. Within the transcriptome of P.ch beside increased transcript levels for oxido- reductases, plant cell wall degrading enzymes and detoxifying enzymes were found. On the other hand in P.al the transcription of some oxido- reductases was increased whereas others appeared to be repressed. In this fungus the confrontation to plant cells results in higher transcript levels of heat shock and chaperon-like proteins as well as genes encoding proteins involved in primary metabolism.

Introduction

Phaeoacremonium aleophilum (P.al) and Phaeomoniella chlamydospora (P.ch) are filamentous fungi frequently isolated from the wooden parts of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) trunks. Therefore these fungi are believed to be causal agents in disease development of the grapevine trunk disease Esca [4].

Grapevine trunk/dieback diseases are on the rise in vineyards all over the world [1][2] or [3]. However, no curative treatment for infected grapevine plants is known [5]. Outbreaks have been reported from almost all vine producing countries [6]. Typical symptoms of Esca trunk disease are discolored trunks and white rot, brown spots on fruits and “tiger stripes” on leaves [7]. In addition these symptoms can vary significantly, depending on the age of the vine, the cultivar and external factors like terroir [8][9]. Beside the two fungi, P.al and P.ch [10][11], additional species can be found in grapevine trunks: Fomitiporia mediterranea [12], Botryosphaeriaceae [13], Eutypa lata [14], Phomopsis viticola [15], Cylindrocarpon [16] and several others [16,17]. All these fungi belong to the phylum of Ascomycota, except the Basidiomycete F. mediterranea. Recently, the genomes of some of these species have been sequenced: P. aleophilum [18], F. mediterranea [19], Eutypa lata [20], Diaporthe ampelina, Diplodia seriata [21] and P. chlamydospora [22]. The actual role of these fungi in relation to trunk diseases is the topic of controversial discussions [23]. Generally, huge differences in the composition of Esca-associated fungal populations were found [4]. In addition P.al, P.ch and other fungi were isolated from affected grapevine plants showing disease symptoms (foliar ‘tiger stripes’) as well as from symptom-free host plants [24][25]. Also Bruez et al. [26] could not detect significant differences in fungal communities extracted from Esca symptomatic and non-symptomatic plants. These findings raised the question whether Esca is a fungal disease after all [25]. As an alternative hypotheses Hofstetter et al. discusses that Esca associated fungi may be either endophytes or saprobes. They also discuss the possibility that varieties of Esca associated fungi display different levels of pathogenicity, what cannot easily determined by using ITS sequencing or comparable methods for species identification[25]. Nevertheless internodal inoculations of P.ch and P.al in grapevine cuttings cause wood symptoms under laboratory conditions [27][28]. Therefore a Koch’s postulate regarding Esca needs to be proven. The postulate, establishing the relationship between a causative agent and the disease [29], cannot only be proved by confirming the presence of a pathogen in its host but also by measurements of its phytotoxic activity. Several studies on pathogenic behavior against plants focus on the production of extracellular cell-wall degrading enzymes and toxic metabolites [30]. For example α-glucans of different molecular weights and two naphthalene pentaketides (scytalone and isosclerone) were detected [31,32].

Plants on the other hand respond to abiotic and biotic stresses by the production of so-called reactive oxygen species (ROS) like the superoxide anion (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (OH•) or the hydroperoxyl radical (HO2•)[33]. Pathogenic or endophytic fungi are exposed to these ROS and have developed strategies to scavenge them using either small molecules that can be oxidized (glutathione, carotenoids, flavonoids, alkaloids and ascorbic acid) or detoxifying enzymes (superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, catalase and peroxiredoxins) [34].

Vitis vinifera L. callus culture have been analyzed for the production of bioactive compounds [35]; hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives and anthocyanins as well as stilbene derivatives and hydroxyphenols in supernatants of the cultures were identified. Dai et al. [36] showed that the production of gallocatechin derivatives and flavonoids increased in grapevine callus cultures, when those were incubated with the oomycete Plasmopara viticola. Furthermore, the production of Quercetin-3-rhamnoside and (+)Catechin increased in calli which were co-cultured with Esca associated fungi [37].

Both fungi grow mainly in the xylem vessels and their surrounding 'cellulose-containing cell walls in grapevine’s trunk. Concerning P.al, a transformed strain P.al GFP was localized in the lumen of xylem vessel and xylem fibers six and twelve weeks post inoculation [38]. This study is consistent with the immunolocalization performed four months post inoculation [39] and also confirms microscopic observation using non-specific technics to localize fungal agents [40]. Landi et al. showed, that the gfp expression of their Pch-sGFP71 transformed line was localized in the xylem area, especially around the vessels [41]. Valtaud et al. showed that P.ch also invades xylem vessels[40]. Note that once established in xylem lumen and fibers both species are also able to develop in other tissues, such as the parenchyma or rays, under laboratory conditions [38] [42][40], especially in plantlets generated in vitro [43]. This suggests that the main nutrient supply for both fungi is provided by the xylem sap.

We attempt to decrease the complexity of interaction between P.al or P.ch and the plant in this model system by eliminating the factors nutrient depletion, water stress and the presence of other microorganisms, including bacteria that are frequently found in the grapevine trunks by using Vitis vinifera callus culture. This model system allows us to focus exclusively on the plant–pathogen interaction.

In order to understand how P.al and P.ch respond to the environment set by V. vinifera we analyzed the transcriptomes of both fungi in axenic or mixed cultures with V. vinifera plant cells (callus culture). We could observe that these fungi respond in a different manner to the plant cell challenge where P.ch induces detoxification and translation machinery genes and P.al alters primary metabolism and induces heat shock related genes. Nevertheless both fungi increase the transcription of oxido-reductases and we could confirm that Vitis leave-disks or callus culture cells react on the presence of P.al or P.ch metabolites by ROS production.

Results

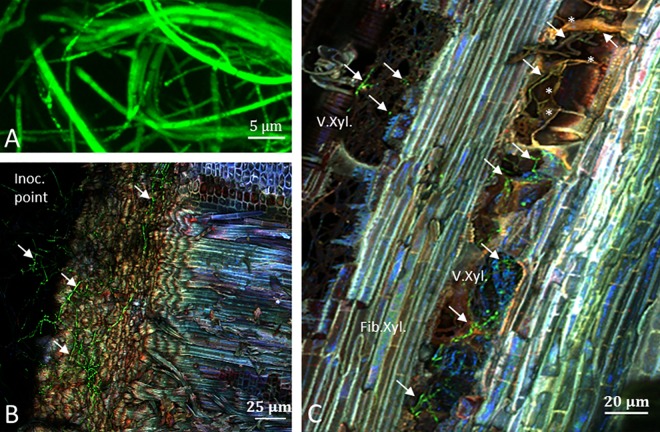

P.ch and P.al Colonization Niches

First, we wanted to confirm that both fungi occupy the same niches within the grapevine trunk. Using newly transformed P.ch expressing gfp (Fig 1A) we analyzed the colonization niches 12 weeks post inoculation (wpi) at the internode of grapevine cuttings (cv. Cabernet Sauvignon). We could observe that the inoculation point was strongly covered with P.ch::gfp1 mycelium expressing gfp 12 wpi (Fig 1B). However, distant from the inoculation point the fungus only colonized xylem vessels and adjacent fibers (Fig 1C, S1 Fig). Also the formation of tyloses, which seemed to partly hamper fungal spray, was observed in these colonized xylem vessels. We conclude therefore that xylem vessels were the main tissue colonized by P.ch::gfp1 in the internode of Cabernet-Sauvignon. This confirms findings published by Landi et al. and Valtaud et al. [41][40]. Similar results were recently found by Pierron et al. [38] for P.al, which is also colonizing xylem vessels. Therefore, we conclude that under the same conditions both fungi occupy the same niches provided by grapevine trunks.

Fig 1. P.ch-gfp1 in internode 12 weeks post inoculation.

A) mycelium expressing gfp, from a pure culture; B) Inoculation point covered with mycelium (↘) expressing gfp; C) Longitudinal section presenting P.ch-gfp1 mainly colonizing xylem vessels. (*) highlights tyloses formation in xylem vessels which partly hampered fungal spray.

A Small Proportion of Fungal Genes Are Differentially Transcribed upon Exposure to Callus Culture

We wanted to investigate the interaction of two Esca-related fungi P.al and P.ch with the plant material of Vitis vinifera in order to understand how these fungi adapt to this woody plant environment. Therefore, we focused on changes of the fungal transcriptome levels induced by plant defense mechanisms independently of nutrient depletion/starvation. Starvation is known to cause a wide range of cellular responses which are not environment specific and thereby hold little information about the particular plant host interaction. To avoid those interferences we designed a setup of axenic media with excess to all relevant nutrients. Thereby the fungi could grow at a relatively high growth rate and optimized conditions with or without callus culture (Vitis vinifera L.) added. For this reason all influences on differential gene expression should be linked to the impact of the plant/callus culture.

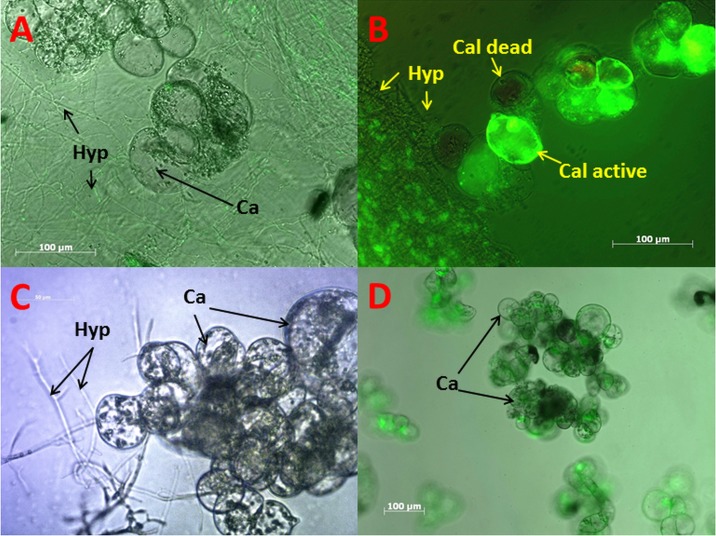

In order to investigate the transcriptional response of the two fungi to the active plant cells we verified the viability of Vitis callus cultures after the incubation in co-cultures. We stained the axenic callus cultures as well as mixed cultures with fluorescein diacetate. The plant esterases of living plant cells cleave fluorescein diactetate and therefore the fluorescence would be visible under UV light [44]. We could demonstrate that up to 80% of the callus cells were viable after 36 hours of co-incubation and 60–70% of the Vitis cells were still metabolic active after an incubation time of 72 hours (Fig 2, S2 and S3 Figs). The GFP fluorescence of the fungal cells is a first indicator for their viability. Almost 100% of the mycelium shows the heterologous expression of the GFP fluorophore (Fig 2B) without formation of aggregates or discoloration frequently observed in dying fungal cells. Furthermore, the death of fungal cells would lead to the leakage of the gf-proteins, visible by division of proteins and the allocation of the fluorescence[45]. Unfortunately, we found that the efficiency of RNA extraction from plant cells was more than 10 times lower compared to extraction from fungal cells (although a plant RNA extraction kit, see materials and methods, was used). This was reflected by the sequencing results. Only 1 to 3% of the obtained sequences could be aligned to V. vinifera genome sequences (see Table 1). Even with a higher amount of Vitis cells or shorter co-incubation times the amount of isolated plant RNA could not be significantly increased so we considered only fungal sequences in this experiment. Interestingly, we could also observe in this assay that neither of the fungi is growing into the plant cells, even if the cells are already dead.

Fig 2. Fluorescence microscopy of V. vinifera callus culture and P.ch mycelium.

A: GFP labeled P.ch visible as green hyphae (Hyp), and callus cells (Cal). B: Fluorescein-diacetate stained active callus cells and dead callus cells (none fluorescent). C: Brightfield image showing hyphae growing around callus cells. D: Monoculture of callus cells with live staining (fluorescein-diacetate).

Table 1. Counts of sequencing reads per sample; P.al or P.ch indicate monoculture of each fungi, +VV indicates co-inoculation with V. vinifera.

1 and 2 indicate the biological repetitions.

| Sample | Total Reads | Aligned to fungi | Aligned to plant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P.al1 | 41599502 | 40089907 | 96.4% | 147433 | 0.4% |

| P.al2 | 40357223 | 38680466 | 95.8% | 371056 | 0.9% |

| P.al+VV1 | 34904228 | 33545735 | 96.1% | 654957 | 1.9% |

| P.al+VV2 | 34619821 | 33088304 | 95.6% | 1111878 | 3.2% |

| P.ch1 | 37154800 | 35081026 | 94.4% | 129653 | 0.3% |

| P.ch2 | 40226826 | 37992439 | 94.4% | 150335 | 0.4% |

| P.ch+VV1 | 34393171 | 31572727 | 91.8% | 630313 | 1.8% |

| P.ch+VV2 | 30764387 | 27518852 | 89.5% | 320653 | 1.0% |

We sequenced the transcriptomes from both experiments, one experiment per strain of P. aleophilum (P.al) and P. chlamydospora (P.ch) with or without callus culture (Vv), using a HiSeq Illumina sequencer. Each sample was biologically replicated: P.al, P.al+Vv, P.ch and P.ch+Vv. Genomes from both strains are available and also gene annotations have been performed. But since this is the first transcriptome on both strains we decided to build a de novo transcriptome assembly based on the sequenced transcripts and the given genomes using Trinity [46].

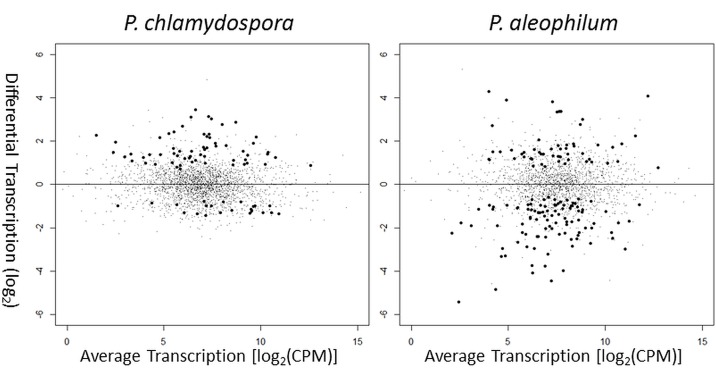

Given a probability of non-differentially regulation (H0) we identified 85 and 153 differentially regulated genes (p<0.01) in P.ch and P.al, respectively (Fig 3). Interestingly, a low number of gene transcripts were affected by callus culture addition, especially in case of P.ch.

Fig 3. MA plot of transcriptomes.

Y-axis: Differential transcription level (log2) between samples with and without addition of V. vinifera callus culture for; left: P. chlamydospora; right: P. aleophilum. Positive values indicate increased transcription in the presence of callus culture, negative values indicate decreased transcription. X-axis: average transcription levels in CPM (counts per million library reads). Black spheres indicate genes with a non-differential transcription probability (H0) of p<0.01 a.k.a. differentially transcribed; black dots indicate non-differentially regulated genes (p≥0.01).

Transcriptomes of Homologous Genes

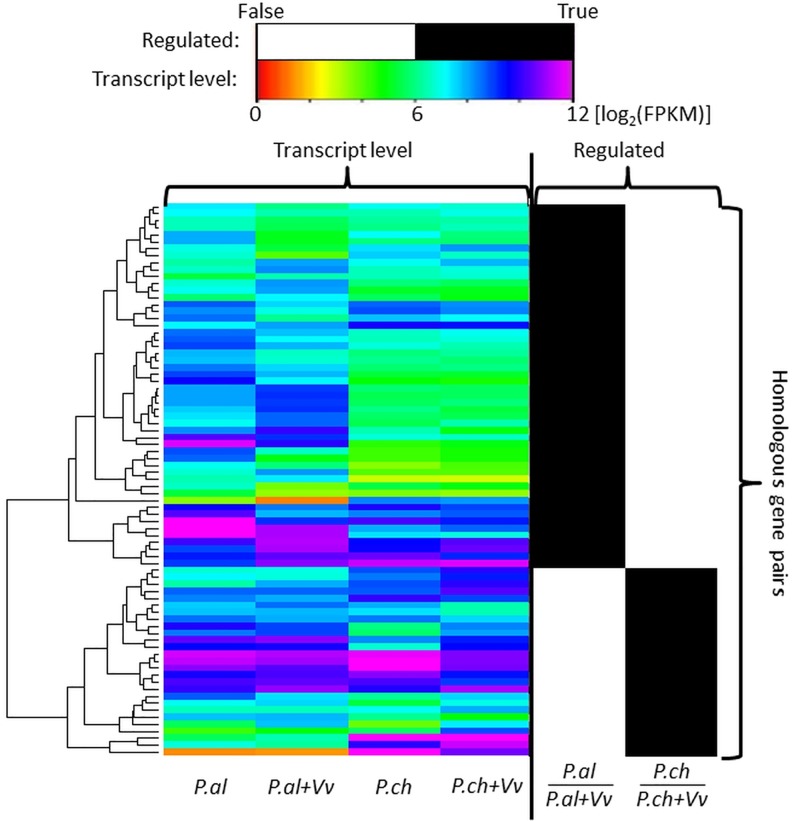

The two fungi P.al and P.ch are not closely related in the fungal kingdom, both belonging to the phylum Ascomycota, but P.al is of the class Sordariomycetes while P.ch is of class Eurotiomycetes. Based on the sequenced transcripts we used two sided BLASTp searches to find 837 homologous (orthologous and paralogous) gene pairs between P.al and P.ch (with e-values of less than 10E-20). In this group of genes 73 and 76 genes of P.al and P.ch are differentially regulated. These numbers are higher than expected since 7.6% (P.al) and 3.2% (P.ch) of the total transcriptome is differentially regulated with expected gene numbers in the homologous gene set of 54 and 23 for P.al and P.ch. In other words, especially for P.ch the majority of differentially regulated genes have a homologous gene in P.al. Strikingly, the set of differentially transcribed genes is strictly exclusive meaning that homologous genes that are differentially transcribed in P.al are not so in P.ch and the other way around (see Fig 4).

Fig 4. Heatmap of 79 differentially regulated homologous gene pairs (orthologous and paralogous) between P.al and P.ch; Transcript level: log2 FPKM values representing the transcription level of the 4 repeated samples P.al, P.ch, P.al+Vv and P.ch+Vv, Vv is indicating co-culture with V. vinifera callus.

Regulated part: black indicates differential regulation (p<0.01) a.k.a. True; and white indicates non-regulated, a.k.a. False.

This is a first hint that the response mechanism due to plant cells is very different between both fungi.

Based on transcriptome data, we selected four differentially transcribed genes from each strain plus the respective beta-tubulin genes for relative quantification by qPCR to confirm our data. Results are presented in S5 Fig.

Oxido- Reductases Are Induced in P. chlamydospora upon V. vinifera Interaction

One of the defense mechanisms of plants against microbes is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). It is not surprising that fungi interacting with plants need to produce enough redox equivalents to detoxify these or support the repair of ROS caused damages. One of the most highly induced genes is a putative Ferredoxin-NADP(H) reductase: PCH_01391.2 and three short-chain dehydrogenase/reductases (SDR): PCH_01570.2, PCH_01766.2., PCH_01970.2. Additionally, a NADPH-quinone reductase was identified: PCH_00455.2; a NAD-binding 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase: PCH_00461.2; Pyridoxamine 5-phosphate oxidase a known quencher of ROS: PCH_00427.2; a Fe-S cluster assembly protein PCH_01032.2; a Inositolphosphorylceramide-B hydroxylase for the synthesis of sphingolipids: PCH_02505.2; a Pyridine nucleotide-disulphide oxido- reductase: PCH_00915.2; a Disulfide bond forming (Dsb) protein: PCH_02049.2; a Cytochrome P450: PCH_01114.2; and a Fatty acid hydroxylase: PCH_00477.2

From these data we can clearly deduce that P.ch is reacting on V. vinifera by adaption its ability to cope with oxidative stress. The origin of this stress might be specific demands due to an altered supply for nutrients and thereby an altered metabolic flow or the production of ROS by the plant. Our experimental setup should supply the fungus with excess of nutrient so we support the second hypothesis that the production of ROS by the plant induces the observed reaction.

Detoxifying Enzymes Are Induced in P. chlamydospora upon V. vinifera Interaction

Nitronate monooxygenase PCH_02292.2, an enzyme that oxidizes alkyl nitronates to aldehydes and nitrite and also known for detoxifying plant originated nitronates is strongly induced upon V. vinifera interaction. This is especially interesting since it was unknown that V. vinifera actually produces these compounds. Nitronates are nitroaliphatic compounds produced by a variety of leguminous plants and several microbial species and 3-nitropropionic acid is a potent inhibitor of succinate dehydrogenase, a key enzyme in the respiratory chain. It is thereby a strong toxin that may play a part in plant defense. Unfortunately, we were unable to detect these alkyl nitronates in the supernatant of Vv-callus or Vv+P.ch co-culture by MS (see discussion).

PCH_01677.2, another potentially detoxifying enzyme, which functions as Dienelactone hydrolase involved in biodegradation of toxic aromatic compounds, was also induced. And an Arsenical-resistance protein ACR3 which codes for a putative arsenite efflux pump: PCH_02435.2 has been induced. This is rather interesting since arsenite was historically used as treatment against trunk diseases in grapevine so one can speculate that the ability to defend against arsenite as well as its signaling remains despite application of arsenite ceased.

Plant Cell Wall Degrading Enzymes Are Induced in P. chlamydospora during V. vinifera Interaction

Two cellulose degrading glycoside hydrolases have been identified: PCH_02658.2, PCH_02659.2; an extracellular lipase: PCH_00486.2 and a Pectinesterase: PCH_00261.2, an enzyme that degrades the primary cell-wall of plants. This indicates that P.ch is inducing plant cell wall degradation even if supply of nutrients is sufficient.

Additional genes significantly induced/repressed are listed in the S1 Table.

Ribosomal and Translational Genes Are Repressed in P. chlamydospora by V. vinifera Interaction

In P.ch, we could detect a clear down-regulatory effect on of several genes involved in the translation of proteins. Eight ribosomal proteins were down-regulated: PCH_00610.2, PCH_01336.2, PCH_01650.2, PCH_00568.2, PCH_00335.2, PCH_01634.2, PCH_00441.2, PCH_02624.2. Additionally, an eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit D: PCH_01955.2; a eukaryotic RNA Recognition Motif containing gene: PCH_00365.2; a queuine tRNA-ribosyltransferase: PCH_01604.2; and an ubiquitin-associated domain/translation elongation factor PCH_00199.2 were repressed. These findings can be a strong hint that translation in P.ch is generally repressed upon interaction with V. vinifera.

Oxido- Reductases Are Induced or Repressed in P. aleophilum upon V. vinifera Interaction

Similar to P.ch, in P.al some oxido- reductases are induced upon interaction with V. vinifera callus culture. PAL_01795.2, an Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase/oxidase; PAL_00101.2, an Acetyl-CoA hydrolase/transferase; PAL_00547.2, a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase; PAL_01859.2 a Glucose-methanol-choline oxido-reductase; PAL_00629.2, a Dyp-type peroxidase; PAL_00526.2, an Epoxide hydrolase-like protein; PAL_01386.2, a Yap1 redox domain protein; PAL_00788.2, NADH:flavin oxido-reductase/NADH oxidase; and PAL_00212.2, a NAD(P)H-quinone oxido-reductase type IV are induced. Despite the fact that fewer oxido- reductase genes are induced in P.al then in P.ch there is a correlation that both fungi need to respond to the oxidative stress introduced by V. vinifera callus culture.

Interestingly some oxido-reductases are also significantly repressed under V. vinifera conditions: PAL_00450.2, PAL_01843.2 and PAL_01340.2, Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase; PAL_01662.2, an Acyl-CoA oxidase/dehydrogenase; PAL_01151.2, an Oxoglutarate/iron-dependent dioxygenase and PAL_01001.2, a Fatty acid desaturase. Also two transcripts coding for 12-oxophytodienoate reductases are strongly repressed: PAL_01110.2 and PAL_00141.2. These proteins are part of the late steps in Jasmonic acid (JA) synthesis. It was demonstrated, that in plants Jasmonic acid (JA) is involved in regulation of plant responses to abiotic and biotic stresses as well as plant growth and development[47]. The function in fungi has to our knowledge not been a focus of major investigation.

Also several hydrolases are repressed: PAL_02006.2, PAL_01486.2, PAL_01400.2, PAL_00137.2 and PAL_00921.2, alpha/beta hydrolases; PAL_00103.2, Serine hydrolase FSH; PAL_00688.2, phosphohydrolase; PAL_00621.2 Glycoside hydrolase.

According to P.ch the P.al transcription of oxido- reductase genes is significantly altered upon V. vinifera interaction, but the pattern of the cellular response seems to be more complex. This hypothesis is supported by the altered expression of several metabolic genes described below.

Heat Shock Proteins and Chaperones Are Differentially Transcribed in P. aleophilum during the Interaction with V. vinifera Cells

In contrast to P.ch P.al responds to V. vinifera with an elevating transcription of general stress response genes: a putative chaperone and retinal-binding proteins of fungi: PAL_00041.2; ubiquitinylated protein degradation Chaperonin: PAL_00562.2; a GroES (chaperonin 10)-like Alcohol dehydrogenase: PAL_00287.2. But three GroES (chaperonin 10)-like Alcohol dehydrogenase, PAL_00725.2, PAL_00151.2 and PAL_00105.2, are repressed. Also PAL_01242.2 the tailless complex polypeptide 1 (TCP-1) chaperone is repressed.

Furthermore, some genes coding for proteins with protein-protein interaction domains are strongly induced: PAL_00046.2, PAL_00047.2, PAL_00045.2, Armadillo-like; PAL_01815.2 Leucine-rich repeat and PAL_01385.2 Basic-leucine zipper.

PAL_00304.2 and PAL_00296.2 peptidases are repressed as well as PAL_01216.2 an ATP-dependent protease.

By considering the putative function in protein modification of the enzymes whose genes are differently transcribed in callus culture media we suggest that P.al responds to V. vinifera by adapting the protein maintenance machinery.

Several Metabolic Gene Transcripts Are Differentially Regulated

Considering the very similar conditions in our experimental setup between axenic culture and callus culture we expected little impact on primary metabolism. This was in fact true for P.ch but in P.al we found several metabolic pathway gene transcripts altered.

Upregulated genes are: PAL_01632.2, Ketopantoate hydroxymethyltransferase essential for the biosynthesis of coenzyme A and penicillin production; PAL_00456.2 Dihydrodipicolinate synthetase for Lysine biosynthesis; PAL_01961.2, Prephenate dehydratase for phenylalanine and secondary metabolite biosynthesis; PAL_00051.2, N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase for Galactose metabolism; PAL_01198.2, 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine synthase in Riboflavin metabolism.

Repressed genes are: PAL_00922.2, phosphomannomutase in fructose and mannose metabolism; PAL_01940.2, maleylacetoacetate isomerase; PAL_00524.2, Inositol-pentakisphosphate 2-kinase in Inositol phosphate metabolism; PAL_00748.2, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA lyase in valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation; PAL_00144.2, long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase and PAL_00724.2, berberine involved in the biosynthesis of numerous isoquinoline alkaloids.

In comparison to P.al in P.ch only two primary metabolic pathway genes were down-regulated (PCH_00503.2 the mandelate racemase/muconate lactonizing enzyme and PCH_00882.2 a 2,5-diketo-D-gluconate reductase) and one homoserine acetyltransferase (PCH_02447.2) was up-regulated. These results indicate, that the impact on P.al in respect to primary metabolism is much more severe.

Additional P.al genes, which are significantly induced/repressed are listed in S2 Table.

Vitis Plant Cells Respond to Fungal Elicitors by ROS Production

As a validation of our results, which indicate, that the fungal cells react to the Vitis callus cultures ROS production, primary induced by fungal elicitors, we conducted a luminol and HRP based luminescence assay. Therefore we quantitatively measured the ROS production of callus cultures and grapevine leave disks in response to P.al and P.ch cultures and fungal elicitors of culture filtrate. Therefore we adapted the luminol-based ROS assay described by Smith and Heese[48].

The differing emission levels of activated luminol for the assorted samples were measured and compared to each other. As illustrated in S4 Fig the samples containing HRP plus luminol and water without any organisms or hydrogen peroxide showed no emission of luminol due to the oxidation by horseradish peroxidase to 3-aminophthalate via several intermediates. The positive control containing H2O2 shows the highest chemiluminenscence activity of all samples measured. The amount of oxidized luminol proportional to the amount of produced ROS by the plant cells is very similar for all samples containing fungal material and leave disk pieces as well as callus cultures, respectively. Pure fungal cultures showed no luminol activation whereas leave disk samples showed a low activation of luminol (results are illustrated in S4 Fig). This effect might occur caused by the wounding of the leave disks.

First, we had to establish the procedure to measure the ROS production by Vitis callus culture cells. Previously the assay was published for leave disks of tobacco and Arabidopsis [49,50] but the technique was not appropriate for the grapevine leaves as well as callus cultures. We tested the assay using B5VIT medium to obtain results comparable to the data of the interaction study and the transcriptome analysis. But the B5VIT medium itself caused an inhibition of luminescence except for the positive control, which was induced by H2O2. After several modifications the best result was obtained in water with the rest of medium included from the washing step. To correlate the amounts of ROS produced by the grapevine cells and the equivalent of hydrogen peroxide the positive control was diluted to a final concentration of 1 μM H2O2. By adjusting the control the counts per minute detected by the luminometer were similar to the luminescence of the samples containing fungal supernatant and plant tissue. In correlation to the samples of mRNA isolated for the transcriptome analysis the elucidation time was adjusted, additionally. Therefore we were able to show, that the expression of mRNA coding for ROS producing enzymes is with an obvious time shift correlated to the actual production of reactive oxygen species. Those ROS efflux to the surrounding medium or water, respectively. No or only a small amount of ROS production was measurable in callus cultures or leave disk pieces without contact to fungal secondary metabolites or elicitors.

Discussion

P. aleophilum and P. chlamydospora have to date mainly been isolated from wooden parts of grapevine trunks or the trunks of fruit trees and our aim was to investigate how these two fungi adapt to this environment. We first confirmed the niches of colonization of P.al [38] and P.ch in the xylem vessels and tissues surrounding them 12 wpi. These observations corroborate with the colonization assays reported by other colleagues several months after inoculation of vine plants with P.ch and P.al. [41][39]. Since growth in wood is extremely slow and retrieval of fungal cells difficult and very inefficient we designed an experimental setup that allows good recovery of cellular material under tightly controlled conditions. We want to point out that this setup was not designed to mimic growth conditions within the trunk since despite the limited nutrient supply and overabundant cellulose/plant cell wall material conditions; additional microorganisms are present in grapevine trunks that putatively have a strong influence on the transcriptome of the respective fungi. Also the specific effect of specialized wood tissue in planta could not be mimicked with this setup. We wanted to clarify the influence of the plant itself on these fungi by eliminating factors involved in nutrient depletion, physical restriction of fungal growth or competing microorganisms. And we wanted to reveal whether there is an analogues response of two different fungi to the same disturbance (plant-activity).

In vitro callus culture setups have already been used for research on host pathogen interaction for example in Elm trees to identify Dutch elm disease resistant genotypes [51][52] or for resistant plant breeding in e.g. maize [53], potato [54] or tobacco[55]. These setups were used to identify or generate resistant plants against specific pathogens with a major focus on the plant. A similar setup to investigate the response of pathogenic fungi against eukaryotic cells has already been undertaken with Candida albicans invading innate immune cells [56]. Here we report a setup to investigate the response of pathogenic fungi to the plant which has not been undertaken so far to the best of our knowledge.

Since this is the first report on the transcriptome of both fungi we used de-novo transcriptome assembly to identify transcripts and performed functional annotation of these. This means that all functional categorizations are based on gene-homology derived predictions.

The response of P. chlamydospora seems to be more direct to the stresses applied by the plant in comparison to P. aleophilum. P.ch responses to the oxidative stress likely facilitated by the plant originating ROS by induction of oxido- reductases and reduced translation. ROS production and programmed cell death (PCD) are closely connected in plants [57] as well as in other organisms, but our fluorescein-diacetate assays showed that the majority of plant cells was still viable after 32h inoculation with either fungi indicating that the production did not take place or that the ROS produced have effectively been quenched by the fungi.

To confirm the ROS response by the plant we conducted luminol assays and measured the amount of ROS produced by the callus culture as well as grapevine leave disk samples due to fungal elicitor’s impact. Importantly, we provide necessary control experiments showing that in our artificial but efficient setup a measurable oxidative burst is accompanied by the altered transcriptomic levels of ROS disassembling enzymes. Furthermore no statistic differences were observed between the ROS production of callus cultures and grapevine leave disks after the induction of the plant cells. The luminol assay was based on the previously published method by Smith and Heese [48]. For this reason we also conducted the assay with leave disks to compare our callus culture results to the data gathered by other induced oxidative bursts of plant cells. Meanwhile, the process of ROS production by plant cells is well known and investigated [58–60]. For other fungal pathogens, in contrast to the Esca-associated fungi, it is well known that they have developed ways to sense and modify ROS accumulation in host plants. Magnaporthe oryzae for example has a defense suppressor 1 gene, which is a novel pathogenicity factor that regulates counter defenses against the host plant [61,62]. Another example is the biotrophic fungus Ustilago maydis. Its transcription factor functions as a redox sensor and controls the hydrogen peroxide detoxification systems [63]. The transcription factor is furthermore required for virulence and is responsible for preventing the accumulation of H2O2 produced by the plant NADPH oxidases. Thus, the use of transcription factors to modify the host oxidative burst could be a general strategy for fungal pathogens to cope with plant defense reactions. The detection and measurement of reactive oxygen species was thereby accomplished. Also we could show that this ROS burst did not cause PCD since the plant cells remained viable after elicitor induction. Moreover we were able to link the transcriptome data of the two fungi explored to the preceding ROS burst conducted by the fungal cells in co-culture.

More genes for plant cell wall degradation are induced in P.ch than in P.al. Interestingly P.ch induces 2 genes specific for detoxification of plant defense metabolites: Dienelactone hydrolase and Nitronate monooxygenase. Alkyl nitronates have been found in leguminous plants as a byproduct of nitrogen fixation but are not reported in V. vinifera but since no other microorganisms were present in our study we suspect the plant as their origin. The fact that we were unable to identify alkyl-nitronate in the supernatant of callus cultures (with or without fungi added) may be due to their presents in too low amounts or the repression of production under these culture conditions. Therefore, the trigger for induction of Nitronate monooxygenase would be another unknown molecule.

The relevance of P.al and P.ch for Esca disease have been discussed [23] and we wanted to shed light on one the transcriptomic aspect of putative pathogenicity. It is well established that fungi are able to produce highly bioactive substances like toxins or antibiotics, but often only under certain growth conditions [64]. We hypothesized that the disease outbreak might not only depend on the presence of the fungi but that they accessorily need to be triggered to produce toxins (e.g. secondary metabolites) that cause disease symptoms.

To our surprise we could not find any putative secondary metabolite (SM) genes regulated due to plant co-inoculation. We considered polyketide synthases non-ribosomal peptide synthases, hybrids thereof or terpene synthases as putative SM genes but could only annotate 4 in the P.ch and 2 in the P.al transcriptome, despite the fact that based on genomic gene predictions there would be more than 10 in each strain. And none of the 6 putative SM genes was differentially regulated. One explanation for this could be that a main trigger of SM induction might be nutrient depletion, a condition we did not meet in this experimental setup at any time which includes the fact that the callus culture cells differ from wood cells.

Genes putatively involved in the translational pathways were found downregulated in P.ch what could be a hint that growth in general could be reduced in the presence of plant cells. In fact in the plant colonization experiments only very slow growth was observed, 0.5-1cm in 12 weeks, compared to 1-2cm in one week on solid B5VIT medium. But naturally the main reason for slow growth in V. vinifera cuttings must be linked to limited nutrient supply in this environment.

For P.al the situation seems to be more complicated except that also P.al seems to react on oxidative stress produced by plant ROS. There is a notable impact on primary metabolic processes that cannot be observed in P.ch and in general more genes seem to be differentially transcribed in P.al (153) then in P.ch (85) despite the fact that we found more transcribed ORFs in P.ch (2661) then in P.al (2008). We want to point out that these counts of ORFs in the respective fungi are smaller than what is predicted by ab inito gene finding on the genomes of P.al (8926)[18] and P.ch (7279)[22], meaning that only genes transcribed in at least one condition were taken into account.

In P.al we could see that genes generally considered as coding for heat shock proteins are differentially regulated. This group of proteins is involved in translational and post translational processes and we hypothesize that this is also the main reason for the differential transcription we observe for primary metabolism genes. However, it could be the other way around that primary metabolism genes have been affected by plant metabolites and therefore a general stress response has been engaged.

Further investigation into the actual factors that drive fungal adaptation to the in-planta environment need to be undertaken in order to get a deeper understanding of these pathogenic fungi. The number of genes we found to be differentially regulated is surprisingly low what hints to the conclusion that the plant cells themselves don’t cause extreme stress on the fungi or trigger very aggressive measures by the fungi. These findings are coherent to the observations that P.al and P.ch can be found in healthy appearing plants [26][25] and that the outbreak of the disease may take several years. We suggest that additional factors are involved in symptom development like interaction with other fungi/bacteria or abiotic stresses like drought or nutrient depletion. From our results we conclude therefore that the two fungi, P.al and P.ch, frequently residing in the same host plant respond to the same disturbance originating from this plant respond in a very different way. We suggest that generally this is probably a perfect way for an endophytic fungal community to withstand not only plant defense mechanisms but also other biotic and abiotic stresses.

Materials and Methods

We were allowed by Pépinière Daydé to harvest the canes in 2013 and 2014. No specific permissions were required since the material was obtained in a way that is standard procedure in vineyard work.

P.chlamydospora-Specific Localization in Xylem Vessels

Fungal strains and preparation for transformation

Phaeomoniella chlamydospora CBS 239.74 was maintained on potato dextrose agar medium (PDA, Merck, Germany) on petri dishes placed in the dark at 26°C. Prior to transformation, a test was performed to determine whether this strain was sensitive to different concentrations of hygromycine B (25 μg.mL-1, 50 μg.mL-1, 75 μg.mL-1 and 100 μg.mL-1) in PDA medium. P.ch was transformed to obtain a strain expressing gfp as done in Pierron et al.[38] and according to Gorfer et al. [65].

Plant Material

One year-old canes of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cabernet Sauvignon clone 15 were harvested in January 2013 and 2014 (Toulouse, Midi-Pyrénées, France) and used to generate three eyed cuttings as described in [38]. In short, the cuttings were treated with fungicide (0.05% Cryptonol) by soaking canes for one hour and thereafter stored at 4°C until further processing. After the preparation of the canes with a bleaching bath (2.5% active chloride) for 1 min and two following rinsing-steps in water, cuttings were incubated at 4°C overnight in a solution of 0.05% Cryptonol. The water-rinsed plant material was planted in plastic trays filled with moistened autoclaved glass-wool (photoperiod 16/8, 25°C; 90% humidity). Budding and rooting took four to six weeks before cuttings were potted in 75 cL pots containing a sterile mixture of perlite, sand and turf (1:1:1 v/v) and were transferred to a growth chamber (photoperiod 16/8, 25°C; 45% humidity). The procedure was also described in Pierron et al.[38] (2015).

Plant Inoculation

Cuttings (n = 20) were inoculated when at least six leaves were fully developed. Firstly, cuttings were partly surface-sterilised with a tissue sprayed with 70% ethanol. Plants were inoculated with hyphae of P.ch::gfp1 (n = 10) from three PDA plates. Mock-treated plants (n = 10) were inoculated with sterile PDA medium. Inoculations were performed at the internode with one syringe to ensure that the same quantity of hyphae was injected.

A wounding damage at the internode was realized (see [38]) before inoculating a cylindrical plug (3 mm long and 1 mm diameter) of P.ch::gfp1 or sterile PDA medium. Only hyphae in the periphery of the growing fungus were collected to avoid the danger of selecting fungal material at a different reproductive stage or with different cell activity at different locations on the same plate. After inoculation, the wound was covered with cellophane.

At sampling for microscopy, plants inoculated with P.ch::gfp1 or control medium (mock) were cut longitudinally or transversely with secateurs. Observations were carried out using a confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview FV1000 with multi-line laser FV5-LAMAR-2 and HeNe(G)laser FV10-LAHEG230-2) and images were processed using ImageJ (see [66]).

For P.al, same strain and procedure as in Pierron et al.[38] was used.

Fermentation, Callus Culture

The callus culture (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Gamay Fréaux; PC-1137), provided from the DSMZ (Leibniz Institute DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Culture) grew on the recommended B5VIT medium. (http://www.dsmz.de/fileadmin/downloads/PC/medium/B5VIT.pdf). Liquid cultures grew also in B5VIT medium in 250 mL flasks filled with 50–70 mL medium. The cultures were renewed twice a week, at least after 4 days of incubation by splitting of the culture.

Fungi Strains and Culture Conditions for Fermentation and Transcriptomics

Phaeomoniella chlamydospora CBS 229.95 and Phaeoacremonium aleophilum (Togninia minima) CBS 100398 were provided from the CBS-KNAW culture collection (CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, The Netherlands). The strains grew on HMG medium (4 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L malt extract, 10 g/L glucose, pH 6.5) and were transferred two new agar plates after two to four weeks. The fermentation was conducted in 50 mL HMG-liquid medium in 100 mL flasks.

Mixed Cultures (Interaction Cultures)

Previous to the interaction studies the fungi were rose in 50 mL flasks in HMG medium inoculated with a spore suspension (1x105 spores/mL) for 72 hours. Thereafter the cultures were pelletized via centrifugation (10 min, 4000 rpm, 22°C) and washed once with B5VIT medium. The aggregated mycelium was suspended in 5 mL B5VIT medium.

The callus cultures were incubated in 50 mL B5VIT medium for 6 days and then centrifuged (5 min, 1500 rpm, 22°C) and dissolved in 45 mL of fresh B5VIT medium.

The two organisms (Vitis callus culture and P.ch respectively P.al) were transferred to new flasks. The co-cultures were incubated for 72 hours (80 rpm, 22°C) on a rocking platform shaker.

All tests were made as triplets. Samples were the fungi-callus-culture mixtures and the fungi without callus culture in B5VIT medium. The preparation of the samples without callus culture was the same as in the co-cultures, but the pelleted mycelia were dissolved in 50 mL B5VIT medium.

Viability Assay

The strains P.al (GFP) and P.ch (GFP) were transformed as described by Figueiredo et al.[67]. The strains obtained from the American Type culture collection were cultivated on minimal medium (according to Kramer et al. supplemented with 400mg/L Hygromycin [67,68].

The co-cultures were also monitored with a fluorescence microscope. Therefore were strains of P.al and P.ch used which contain a pCambia Vector construct that includes a Hygromycin resistance and the coding sequence for the green fluorescence protein. The green fluorescence emission associated with GFP was detected using an Imager M.2 microscope (Zeiss, Jena) with the following filter settings: 488 nm excitation and 515 nm emission. Images have been recorded with the AxioCamMRm camera.

The co-cultures were also stained with fluorescein-diacetate to determine the amount of viable grapevine callus cells. The co-cultures were monitored for 120 hours every 24 hours. To stain the preparation 20μL of cell-mixture and 2μL fluorescein-diacetate solution (1mg/10mL) were mixed. The fluorescence is only detectable if esterases in living cells cleave the fluorescein-diacetate [69].

RNA Extraction and Sequencing

The co-incubation was stopped after 72 h. The growth medium and the mycelium or the plant cells + mycelium were separated via filtration. The mycelium/ plant cells were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at -86°C.

RNA was extracted using Qiagen RNAeasy Plant Mini Kit and RNAse-Free DNAse Set for complete removal of genomic DNA. RNA was reverse transcribed using Biorad iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit and specific transcripts were verified using qPCR (iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix, Biorad). Primers used are found in S3 Table. Total RNA samples were further processed by VetCORE, VetMed University Vienna for high throughput sequencing. RNA fragmentation and Reverse Transcription were realized according to TruSeq RNA prep Kit v2 manual (Illumina, San Diego, US) and 50bp single end sequencing was performed using HiSeq V4 Illumina sequencer. Between 30 and 40 million reads were obtained per sample.

Data Processing

After quality control, all remaining sequences were used for genome based de-novo transcriptome assembly by Trinity [46]. The obtained transcripts were filtered for low coverage and mRNA, ORF and peptide sequences were calculated using the Trinity plugin Transdecoder. For P.ch and P.al 2661 and 2008 complete ORFs and Protein sequences were found as being sufficiently transcribed for detection in this experiment in at least one condition. The ORFs were mapped back on the respective genomes using BLAT [70] and gff files were constructed containing exon positions of the respective ORFs. Novoalign (Novocraft) was used for mapping the sequencing raw files onto the respective genomes and the python script HTSeq (Anders et al., 2014) was used to obtain coverage counts per exons. Normalization and statistics of the coverage counts per transcript were done using R/Bioconductor packages limma [71], EdgeR and voom [72] to identify differentially regulated genes using mean-variance weighting (voom) and TMM normalization (Gentleman et al., 2004). A significance cut-off of p < 0.01 (adjusted for multiple testing by the false discovery rate method) was applied for analysis. Data have been deposited at NCBI GEO under the accession number GSE67197.

The protein sequences were annotated using InterProScan [73] to receive also GO (gene ontology) and KEGG (pathway) information.

ROS Assay

Leave disks of grapevine plants (1cm2) were cut into sixteen parts 24 hours before the ROS assay was conducted and placed into a 96-well plate. Each sample contained 16 pieces in a triplet. One half of the leaf sections was covered with 200 μL sterile fungal culture filtrate of Pal or Pch grown in B5Vit Medium for four days. As a control the other 50 percent of the leaf samples were covered with H2O. Thereafter the samples were incubated over night at 22°C. In a second approach cells of a three weeks old callus culture (which were transferred weekly in new B5Vit medium) were diluted to an optical density of OD600 = 0.1. Afterwards 200 μL of the dilution were centrifuged in a 1.5 mL reaction tube and the supernatant was discarded. The remaining cell pellet was resuspended in 100 μL H2O and transferred to a 96-well plate as well. To the callus culture cells 100 μL fungal culture filtrate was added.

The Peroxidase from horseradish (HRP, Sigma-Aldrich, #P8375) was prepared as a stock solution (500x) by dissolving 10 mg/ml lyophilized powder in H2OUF. The stock solution was stored at -20°C until usage in the test at a concentration of 20 μg/mL. Luminol was also prepared as a 500x stock solution by diluting 17 mg luminol (luminol, Carl Roth, # 4203.1) in 1 mL of 200 mM KOH. The concentration used finally in the test system was 0.2 μM. Therefore 20 μL of both stock solutions were added to 10 mL distilled water [48].

Immediately prior to the luminol assay the mixture of luminol and HRP was added to the leave samples and callus cultures (Repka, 2001). The measurement of ROS production by the Vitis cells as a reaction to the fungal culture filtrate was monitored without delay after the reaction solutions were added. For this purpose an EnVision Multilabel Reader (Perkin Elmer, 2104-0010A) and the standard luminescence program were used. The measurement was conducted for 12 minutes. The reaction progress was observed by measurement every 20 seconds in alteration with a 10 seconds shaking step (120 rpm). As controls fungal cells leave disks and Vitis callus culture cells were added separately to the reaction solutions also in the 96-well microtiter plate. Furthermore a control containing 1 μM H2O2 was conducted to determine the reactive potential of the HRP and the luminol solutions. The reaction solutions were also added as a negative control to water. All results are compiled in S4 Fig.

Supporting Information

P.al-GFP strain, visible as green hyphen, 12wpi in xylem vessels, indicated by arrows.

(TIF)

A: GFP labeled P.al visible as green hyphae (Hyp), and callus cells (Cal). B: Fluorescein-diacetate stained active callus cells and dead callus cells (none fluorescent). Red bar 100μm.

(TIF)

Light gray, co-incubation of callus cells with Pch; gray, co-incubation of callus cells with Pal and dark gray, axenic callus culture. The calculation was made based on staining the callus cells with fluorescein diactetate and count cells with a Neubauer counting camber.

(JPG)

Display of the transient ROS production of Vitis vinifera callus and leaf tissue cells in response P.al and P.ch culture filtrate. All values were measured using an EnVision Multibal Reader (Perkin Elmer, 2104-0010A) and a standardized luminol assay. P.ch Vitis callus is the sample where P.ch filtrate was premixed with callus culture cells. P.ch Vitis disk is the nomenclature for Vitis leaf disks that were mixed with P.ch culture filtrate preliminary to the measurement. The labeling for P.al is identically carried out. The two control reactions are the activation of the horse-reddish peroxidase by H2O2 (control hydrogen peroxide) and the buffer mixed only with luminol and HRP, which was not activated by H2O2. The emission of the activated luminol was measured every 20 seconds for 12 minutes (as can be seen at the x-axis). The measured counts per minute are arranged in analogy to all the samples conducted as triplets and in comparison to 1μM H2O2 equivalent in the control setup.

(TIF)

Different transcription levels correlate with measurements from high throughput sequencing. +VV indicates co-cultivations.

(JPG)

Columns: gene name, differential transcription (log2), average transcription (log2), probability to dismiss H0, gene description 1, gene description 2, GO annotation, pathway annotation.

(TXT)

Columns: gene name, differential transcription (log2), average transcription (log2), probability to dismiss H0, gene description 1, gene description 2, GO annotation, pathway annotation.

(TXT)

(TXT)

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Birgit Tschiatschek for support in the lab; Monika Riedle-Bauer and Ferdinant Regner (LFZ Klosterneuburg) for supplying expertise concerning grapevines/vineyards, Anja Schüffler, Angela Sessitsch and Joseph Strauss for scientific support.

Data Availability

Data have been deposited at NCBI GEO under the accession number GSE67197 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=wlmzguegrxkrtmv&acc=GSE67197

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Surico G, Mugnai L, Marchi G. Older and more recent observations on esca: a critical overview. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2006;45: 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rolshausen PE, Kiyomoto R. The Status of Grapevine Trunk Diseases in the Northeastern United States. [Internet]. 2011. Available: http://www.newenglandvfc.org/pdf_proceedings/status_grapevinetrunkdisease.pdf.

- 3.Reisenzein H, Berger N, Gerald N. Esca in Austria. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2000;39: 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer M, Kassemeyer HH. Fungi associated with Esca disease of grapevine in Germany. Vitis. 2003;42: 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert C, Khiook ILK, Lucas S, Télef-Micouleau N, Mérillon J-M, Cluzet S. A faster and a stronger defense response: one of the key elements in grapevine explaining its lower level of susceptibility to esca? Phytopathology. 2013;103: 1028–34. 10.1094/PHYTO-11-12-0305-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiarappa L. Esca (black measles) of grapevine. An overview. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2000;39: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mugnai L, Graniti A, Surico G. Esca (Black Measles) and Brown Wood-Streaking: Two Old and Elusive Diseases of Grapevines. Plant Dis. 1999;83: 404–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grosman J, Doublet B. Maladies du bois de la vigne: Synthèse des dispositifs d’observation au vignoble, de l'observatoire 2003–2008 au réseau d'épidémiosurveillance actuel. Phytoma-La Défense des végétaux. 2012;651: 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerin-Dubrana L, Labenne A, Labrousse JC, Bastien S, Rey P, Gerout-Petit A. Statistical analysis of grapevine mortality associated with esca or Eutypa dieback foliar expression. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2013;52. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards J, Pascoe IG. Occurrence of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora and Phaeoacremonium aleophilum associated with Petri disease and esca in Australian grapevines. Australas Plant Pathol. 2004;33: 273. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serra S, Mannoni MA, Ligios V. Studies on the susceptibility of pruning wounds to infection by fungi involved in grapevine wood diseases in Italy [Internet]. Phytopathologia Mediterranea. 2009. pp. 234–246. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer M. A new wood-decaying basidiomycete species associated with esca of grapevine:Fomitiporia mediterranea (Hymenochaetales). Mycol Prog. 2002;1: 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Úrbez-Torres JR, Leavitt GM, Voegel TM, Gubler WD. Identification and Distribution of Botryosphaeria spp. Associated with Grapevine Cankers in California. Plant Dis. The American Phytopathological Society; 2006;90: 1490–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moller WJ, Kasimatis AN. Dieback of grapevines caused by Eutypa armeniacae. Plant Dis Report. 1978;62: 254–258. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbez-Torres JR, Peduto Hand F, Smith RJ, Gubler WD. Phomopsis dieback: a grapevine trunk disease caused by Phomopsis viticola in California. Plant Dis. 2013;97: 1571–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halleen F, Fourie P, Crous P. A review of black foot disease of grapevine. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2006;45: 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rolshausen PE, Úrbez-torres JR, Rooney-latham S, Eskalen A, Smith RJ, Gubler WD. Evaluation of Pruning Wound Susceptibility and Protection Against Fungi Associated with Grapevine Trunk Diseases. Am J Enol Vitic. 2010;61: 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanco-Ulate B, Rolshausen P, Cantu D. Draft Genome Sequence of the Ascomycete Phaeoacremonium aleophilum Strain UCR-PA7, a Causal Agent of the Esca Disease. Genome Anouncement. 2013;1: 3–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Floudas D, Binder M, Riley R, Barry K, Blanchette R a, Henrissat B, et al. The Paleozoic origin of enzymatic lignin decomposition reconstructed from 31 fungal genomes. Science. 2012;336: 1715–9. 10.1126/science.1221748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanco-Ulate B, Rolshausen PE, Cantu D. Draft Genome Sequence of the Grapevine Dieback Fungus Eutypa lata UCR-EL1. Genome Anouncement. 2013;1: 1–2. 10.1128/genomeA.00228-13.Copyright [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morales-Cruz A, Amrine KCH, Blanco-Ulate B, Lawrence DP, Travadon R, Rolshausen PE, et al. Distinctive expansion of gene families associated with plant cell wall degradation, secondary metabolism, and nutrient uptake in the genomes of grapevine trunk pathogens. BMC Genomics. BMC Genomics; 2015;16: 469 10.1186/s12864-015-1624-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonielli L, Compant S, Strauss J, Sessitsch A, Berger H. Draft Genome Sequence of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora Strain RR-HG1, a Grapevine Trunk Disease (Esca)-Related Member of the Ascomycota. Genome Anouncement. 2014;2: 2013–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertsch C, Ramírez-Suero M, Magnin-Robert M, Larignon P, Chong J, Abou-Mansour E, et al. Grapevine trunk diseases: complex and still poorly understood. Plant Pathol. 2012;62: 243–265. [Google Scholar]

- 24.González V, Tello ML. The endophytic mycota associated with Vitis vinifera in central Spain. Fungal Divers. 2010;47: 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofstetter V, Buyck B, Croll D, Viret O, Couloux A, Gindro K. What if esca disease of grapevine were not a fungal disease? Fungal Divers. 2012;54: 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruez E, Vallance J, Gerbore J, Lecomte P, Da Costa J-P, Guerin-Dubrana L, et al. Analyses of the temporal dynamics of fungal communities colonizing the healthy wood tissues of esca leaf-symptomatic and asymptomatic vines. PLoS One. 2014;9: e95928 10.1371/journal.pone.0095928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laveau C, Letouze A, Louvet G, Bastien S, Guerin-Dubrana L. Differential aggressiveness of fungi implicated in esca and associated diseases of grapevine in France. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2009;48: 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urbez-Torres JR, Haag P, Bowen PA, O’Gorman DT. Grapevine Trunk Diseases in British Columbia: Incidence and Characterization of the Fungal Pathogens Associated with Esca and Petri Diseases of Grapevine. Plant Dis. 2014;98: 469–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch R. Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus Anthracis. Coohns Beiträge zur Biol der Pflanz. 1870;2: 277. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andolfi A, Mugnai L, Luque J, Surico G, Cimmino A, Evidente A. Phytotoxins produced by fungi associated with grapevine trunk diseases. [Internet]. Toxins. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sparapano L, Bruno G, Graniti A. Effects on plants of metabolites produced in culture by Phaeoacremonium chlamydosporum, P. aleophilum and Fomitiporia punctata. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2000; 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sparapano L, Bruno G, Graniti A. Three-year observation of grapevines cross-inoculated with esca-associated fungi. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2001; 376–386. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baxter A, Mittler R, Suzuki N. ROS as key players in plant stress signalling. J Exp Bot. 2014;65: 1229–1240. 10.1093/jxb/ert375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann S, Serrano M, Haridon FL, Tjamos SE, Metraux J. Reactive oxygen species and plant resistance to fungal pathogens. Phytochemistry. Elsevier Ltd; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mewis I, Smetanska IM, Müller CT, Ulrichs C. Specific poly-phenolic compounds in cell culture of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Gamay Fréaux. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;164: 148–161. 10.1007/s12010-010-9122-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dai GH, Andary C, Mondolot-Cosson L, Boubals D. Involvement of phenolic compounds in the resistance of grapevine callus to downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola). Eur Plant Pathol. 1995;101: 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruno G, Sparapano L. Effects of three esca-associated fungi on Vitis vinifera L.: III. Enzymes produced by the pathogens and their role in fungus-to-plant or in fungus-to-fungus interactions. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2006;69: 182–194. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierron R, Gorfer M, Berger H, Jacques A, Sessitsch A, Strauss J, et al. Deciphering the niches of colonisation of Vitis vinifera L. by the esca–associated fungus Phaeoacremonium aleophilum using a gfp marked strain and cutting systems. PLoS One. 2015;10(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleurat-Lessard P, Luini E, Berjeaud J-M, Roblin G. Immunological detection of Phaeoacremonium aleophilum, a fungal pathogen found in esca disease. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2014;139: 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valtaud C, Larignon P, Roblin G, Fleurat-Lessard P. Developmental and ultrastructural features of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora and Phaeoacremonium aleophilum in relation to xylem degradation in esca disease of the grapevine. J Plant Pathol. 2009;91: 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landi L, Murolo S, Romanazzi G. Colonization of Vitis spp. wood by sGFP-transformed Phaeomoniella chlamydospora, a tracheomycotic fungus involved in Esca disease. Phytopathology. 2012;102: 290–7. 10.1094/PHYTO-06-11-0165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pouzoulet J, Jacques A, Besson X, Dayde J, Mailhac N. Histopathological study of response of Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon to bark and wood injury with and without inoculation by Phaeomoniella chlamydospora. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2013;52: 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feliciano A, Gubler W. Histological investigations on infection of grape roots and shoots by Phaeoacremonium spp. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2001; 387–393. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saruyama N, Sakakura Y, Asano T, Nishiuchi T, Sasamoto H, Kodama H. Quantification of metabolic activity of cultured plant cells by vital staining with fluorescein diacetate. Anal Biochem. 2013;441: 58–62. 10.1016/j.ab.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mochizuki S, Minami E, Nishizawa Y. Live-cell imaging of rice cytological changes reveals the importance of host vacuole maintenance for biotrophic invasion by blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae. Microbiologyopen. 2015;4: 952–66. 10.1002/mbo3.304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson D a, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29: 644–52. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marchive C, Léon C, Kappel C, Coutos-Thévenot P, Corio-Costet M-F, Delrot S, et al. Over-expression of VvWRKY1 in grapevines induces expression of jasmonic acid pathway-related genes and confers higher tolerance to the downy mildew. PLoS One. 2013;8: e54185 10.1371/journal.pone.0054185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith JM, Heese A. Rapid bioassay to measure early reactive oxygen species production in Arabidopsis leave tissue in response to living Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Methods. 2014;10: 6 10.1186/1746-4811-10-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bindschedler L V, Dewdney J, Blee KA, Stone JM, Asai T, Plotnikov J, et al. Peroxidase-dependent apoplastic oxidative burst in Arabidopsis required for pathogen resistance. Plant J. 2006;47: 851–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allan AC, Fluhr R. Two Distinct Sources of Elicited Reactive Oxygen Species in Tobacco Epidermal Cells. Plant Cell. 1997;9: 1559–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diez J, Gil L. Effects of Ophiostoma ulmi and Ophiostoma novo-ulmi culture filtrates on elm cultures from genotypes with different susceptibility to Dutch elm disease. Eur J For Path. 1998;28: 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pijut PM, Domir SC, Lineberger RD, Schreiber LR. Use of culture filtrates of Ceratocystis ulmi as a bioassay to screen for disease tolerant Ulmus americana. Plant Sci. 1990;70: 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gengenbach BG, Green CE, Donovan CM. Inheritance of selected pathotoxin resistance in maize plants regenerated from cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74: 5113–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Behnke M. Selection of potato callus for resistance to culture filtrates of Phytophthora infestans and regeneration of resistant plants. Theor Appl Genet. 1979;55: 69–71. 10.1007/BF00285192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carlson PS. Methionine sulfoximine—resistant mutants of tobacco. Science. 1973;180: 1366–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tierney L, Linde J, Müller S, Brunke S, Molina JC, Hube B, et al. An Interspecies Regulatory Network Inferred from Simultaneous RNA-seq of Candida albicans Invading Innate Immune Cells. Front Microbiol. Frontiers; 2012;3: 85 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petrov V, Hille J, Mueller-Roeber B, Gechev TS. ROS-mediated abiotic stress-induced programmed cell death in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6: 69 10.3389/fpls.2015.00069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davies DR, Bindschedler L V, Strickland TS, Bolwell GP. Production of reactive oxygen species in Arabidopsis thaliana cell suspension cultures in response to an elicitor from Fusarium oxysporum: implications for basal resistance. J Exp Bot. 2006;57: 1817–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Brien JA, Daudi A, Butt VS, Bolwell GP. Reactive oxygen species and their role in plant defence and cell wall metabolism. Planta. 2012;236: 765–79. 10.1007/s00425-012-1696-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patel TK, Williamson JD. Mannitol in Plants, Fungi, and Plant-Fungal Interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chi M-H, Park S-Y, Kim S, Lee Y-H. A novel pathogenicity gene is required in the rice blast fungus to suppress the basal defenses of the host. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5: e1000401 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu G, Greenshields DL, Sammynaiken R, Hirji RN, Selvaraj G, Wei Y. Targeted alterations in iron homeostasis underlie plant defense responses. J Cell Sci. 2007;120: 596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Molina L, Kahmann R. An Ustilago maydis gene involved in H2O2 detoxification is required for virulence. Plant Cell. 2007;19: 2293–309. 10.1105/tpc.107.052332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keller NP, Turner G, Bennett JW. Fungal secondary metabolism—from biochemistry to genomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3: 937–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gorfer M, Klaubauf S, Bandian D, Strauss J. Cadophora finlandia and Phialocephala fortinii: Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and functional GFP expression. Mycol Res. 2007;111: 850–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Campisano A, Ometto L, Compant S, Pancher M, Antonielli L, Yousaf S, et al. Interkingdom transfer of the acne-causing agent, Propionibacterium acnes, from human to grapevine. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31: 1059–65. 10.1093/molbev/msu075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Figueiredo JG, Goulin EH, Tanaka F, Stringari D, Kava-Cordeiro V, Galli-Terasawa L V, et al. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Guignardia citricarpa. J Microbiol Methods. 2010;80: 143–7. 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kramer B, Thines E, Foster AJ. MAP kinase signalling pathway components and targets conserved between the distantly related plant pathogenic fungi Mycosphaerella graminicola and Magnaporthe grisea. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46: 667–81. 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Widholm JM. The use of fluorescein diacetate and phenosafranine for determining viability of cultured plant cells. Stain Technol. 1972;47: 189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kent WJ. BLAT—The BLAST-Like Alignment Tool. Genome Anouncement. 2002;12: 656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3: Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014;15: R29 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jones P, Binns D, Chang H, Fraser M, Li W, Mcanulla C, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30: 1236–1240. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

P.al-GFP strain, visible as green hyphen, 12wpi in xylem vessels, indicated by arrows.

(TIF)

A: GFP labeled P.al visible as green hyphae (Hyp), and callus cells (Cal). B: Fluorescein-diacetate stained active callus cells and dead callus cells (none fluorescent). Red bar 100μm.

(TIF)

Light gray, co-incubation of callus cells with Pch; gray, co-incubation of callus cells with Pal and dark gray, axenic callus culture. The calculation was made based on staining the callus cells with fluorescein diactetate and count cells with a Neubauer counting camber.

(JPG)

Display of the transient ROS production of Vitis vinifera callus and leaf tissue cells in response P.al and P.ch culture filtrate. All values were measured using an EnVision Multibal Reader (Perkin Elmer, 2104-0010A) and a standardized luminol assay. P.ch Vitis callus is the sample where P.ch filtrate was premixed with callus culture cells. P.ch Vitis disk is the nomenclature for Vitis leaf disks that were mixed with P.ch culture filtrate preliminary to the measurement. The labeling for P.al is identically carried out. The two control reactions are the activation of the horse-reddish peroxidase by H2O2 (control hydrogen peroxide) and the buffer mixed only with luminol and HRP, which was not activated by H2O2. The emission of the activated luminol was measured every 20 seconds for 12 minutes (as can be seen at the x-axis). The measured counts per minute are arranged in analogy to all the samples conducted as triplets and in comparison to 1μM H2O2 equivalent in the control setup.

(TIF)

Different transcription levels correlate with measurements from high throughput sequencing. +VV indicates co-cultivations.

(JPG)

Columns: gene name, differential transcription (log2), average transcription (log2), probability to dismiss H0, gene description 1, gene description 2, GO annotation, pathway annotation.

(TXT)

Columns: gene name, differential transcription (log2), average transcription (log2), probability to dismiss H0, gene description 1, gene description 2, GO annotation, pathway annotation.

(TXT)

(TXT)

Data Availability Statement

Data have been deposited at NCBI GEO under the accession number GSE67197 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=wlmzguegrxkrtmv&acc=GSE67197