Abstract

Objective

Computerized adaptive testing (CAT) provides improved precision and decreased test burden when compared to traditional fixed length tests. Concerns regarding reliability of CAT-based measurements have been raised because different items are administered both between and within individuals over time. The study measures test-retest reliability of a depression CAT inventory (CAT-DI).

Methods

A random sample of 101 adults at an academic emergency department (ED) was screened twice during their visit with the CAT-DI. Test-retest scores, bias, and reliability were assessed.

Results

79.2% patients scored in the normal (0–49), 13.9% mild (50–64), 4.1% moderate (65–74) and 2.8% severe (75–100) ranges. Test-retest scores were without significant bias and had a reliability of r = .92.

Conclusions

The CAT-DI provided stable trait estimation in ED patients with test-retest reliability greater than traditional fixed-length. Test-retest reliability concerns due to different item presentations upon repeat testing were not supported by our findings.

Overview

Depression is associated with increased mortality, adverse physical health outcomes, and costs (1–2). The emergency department (ED) plays an important safety net role for patients with behavioral health problems (3) and thus may be an ideal setting to diagnose and initiate treatment for patients with depression. Current estimates suggest that between 8% to 32% of ED patients presenting depression (4–6). However, high patient volumes and limited access to behavioral health expertise often make the detailed assessments of depression severity required to initiate treatment unfeasible in the ED. Therefore, any strategy that reduces the burden of empirically-based assessment of depression has the potential to improve outcomes (7).

Existing issues with depression screening and diagnosis in the ED may be overcome if one looks at the recent considerable progress made in the development of rapid screening (8) and measurement (9–10) of depression using computerized adaptive testing (CAT) based on multidimensional item response theory (IRT) (9,11,12). The advantages of this approach include: the use of large item banks (e.g. over 1000 items) which tap every domain, subdomain, and facet of an underlying disorder from which a small optimal set of items are adaptively administered for a given patient depending on their severity level; a constant level of precision for all subjects and for all measurement occasions within subjects as their severity level changes; adaptation across testing sessions, where the previous depression severity score is used to initiate the next testing session; elimination of response-set bias in which subjects are repeatedly asked the same questions; models for both diagnostic screening and dimensional severity based on different statistical approaches; incorporation of the multidimensionality of mental health constructs; and the ability to combine items with different response formats, different severity levels, and different ability to discriminate high and low levels of the construct of interest in the same test. The paradigm shift is from traditional measurement, which fixes the number of items administered and allows measurement uncertainty to vary, to IRT-based CAT, which fixes measurement uncertainty and allows the content and number of items to vary.

While CAT promises several practical advantages for depression screening and measurement, concerns have been raised in the literature about test-retest reliability (stability) (13). Test-retest reliability reflects the variation in measurements for a given person under the same conditions in a short period of time. Because the same test is administered twice, differences between scores should be due solely to measurement error. This is often problematic for psychological testing since the construct being measured may change between the two test administrations (14). Repeated administration of classical fixed-length tests within a short time interval is problematic because it can lead to inflated test-retest reliability due to recall. This is not true for CAT administration where different items are administered upon repeat administration even if the underlying trait of interest has not changed. However, it has been suggested that the use of different items upon repeat administration may lead to diminished stability relative to traditional fixed-length tests.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the test-retest reliability of the CAT Depression Inventory (9) (CAT-DI) in the dynamic environment of an academic ED.

Methods

From May 2015 to July 2015, 101 patients, from a larger sample of 1000, presenting to the University of Chicago Medical Center ED were screened twice within the course of their ED visit with the CAT-DI. Research assistants randomly selected patients to approach from a snapshot of the current ED census. Patients with critical illness, under the age of 18, non-English speaking, without decisional capacity, or with a behavioral health related chief complaint were excluded. Following written consent, the CAT-DI was administered twice by research assistants using tablet computers. The second test was administered within 1 to 3 minutes following the end of the first test. All procedures were approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

The CAT-DI test was designed to ask different questions on the repeated administrations not only based on changes in severity but also by selecting the next two optimal items at each point in the adaptive testing session and randomly selecting between them with a .5 probability. In this way, even if the depressive severity level is unchanged, different items will be presented during the two testing sessions. Scores were expressed on a 100-point scale with precision equal to 5 points. Pearson product-moment correlation was used to assess test-retest reliability and a paired t-test was used to examine bias.

Results

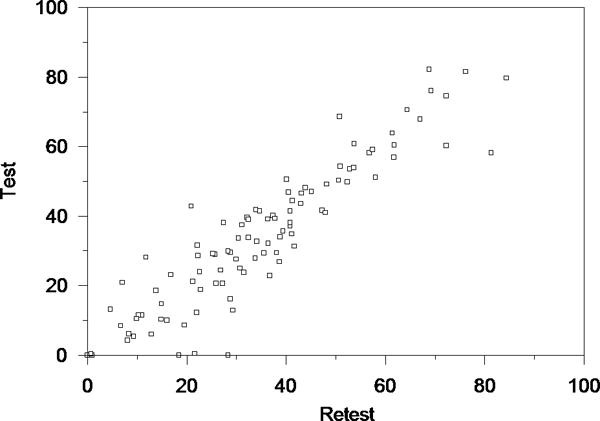

Test-retest reliability was r = .92. The range of scores on the two testing sessions were 0 – 84.4 and 0 – 82.1. Means (standard deviations) were 34.60 (19.28) and 33.81 (20.77) with an average difference of .83, t=1.02, df=100, p=.31, indicating no significant bias between test sessions. The figure reveals consistent results between the two testing sessions. Median time to test completion was 93s (IQR 67 – 128s) across the total sample. The sample included 79.2% patients in the normal range (0–49), 13.9% mild (50–64), 4.1% moderate (65–74) and 2.8% severe (75–100) based on categories developed in our original study (9).

Figure 1. Test Retest Correlation.

Computerized Adaptive Testing – Depression Inventory (CAT-DI)

Summary

CAT based on multidimensional IRT led to stable trait estimation upon repeated testing. Scores were both highly correlated between the two occasions and without evidence of bias. Concerns regarding limitations on test-retest reliability due to administration of different items were not supported by our findings. Test-retest reliability for CAT-DI in fact exceeded that observed for the fixed-length PHQ-9 (r=.84) (15). The ED is an ideal setting to test the reliability of CAT due to the dynamic nature of acute conditions, which can lead to greater fluctuations in mood.

It may be that items that provide good discrimination of high and low levels of depression in a psychiatric setting may fail to do so in a general medical ED. In future work we will examine differential item functioning between these two settings and identify specific items (e.g. somatic items) which may be less useful for the assessment of depression in the ED. These items can be eliminated from the adaptive administration process in the ED leading to further increases in precision and decreases in test length in this setting.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant number R01 MH66302.

We acknowledge the efforts of Dave Patterson and our research volunteers Alexandra Berthiaume, Cody Davis, Annie Hao, and Anna Shin in the conduct of this study.

Footnotes

Disclosures

RG is a founder of Adaptive Testing Technologies which distributes the CAT-Mental Health instruments.

Contributor Information

David Beiser, University of Chicago – Emergency Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Milkie Vu, University of Chicago – Emergency Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Robert Gibbons, Email: rdg@uchicago.edu, University of Chicago – Center for Health Statistics.

References

- 1.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3135–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang PS, Kessler RC. Global burden of mood disorders. In: Stein DJ, Kupfer DJ, Schatzberg AF, editors. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Mood Disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolan MA, Mace SE. Pediatric mental health emergencies in the emergency medical services system. Pediatrics. 2006;18:1764–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg SE, Whittamore KH, Harwood RH, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems among older adults admitted as an emergency to a general hospital. Age and Ageing. 2012;41:80–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoyer D, David E. Screening for depression in emergency department patients. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012;43:786–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar A, Clark S, Boudreaux ED, et al. A multicenter study of depression among emergency department patients. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2004;11:1284–9. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbons RD, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Computerized adaptive testing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093634. Epub ahead of print, March 28, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibbons RD, Hooker G, Finkelman MD, et al. The computerized adaptive diagnostic test for major depressive disorder (CAD-MDD): A screening tool for depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74:669–74. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbons RD, Weiss DJ, Pilkonis PA, et al. Development of a computerized adaptive test for depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:1104–12. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Achtyes ED, Halstead S, Smart L, et al. Validation of computerized adaptive testing in an outpatient nonacademic setting: The VOCATIONS Trial. Psychiatric Services. 2015;66:1091–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbons RD, Hedeker DR. Full-information item bi-factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1992;57:423–36. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbons RD, Bock RD, Hedeker D, et al. Full-information item bifactor analysis of graded response data. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2007;31:4–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan K. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:350–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidshofer KR, Murphy CO. Psychological testing: principles and applications. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]