Abstract

Opportunities to evaluate strategies to create system-wide change in the child welfare system (CWS) and the resulting public health impact are rare. Leveraging a real-world, system-initiated effort to infuse the use of evidence-based principles throughout a CWS workforce, a pilot of the R3 model and supervisor-targeted implementation approach is described. The development of R3 and its associated fidelity monitoring was a collaboration between the CWS and model developers. Outcomes demonstrate implementation feasibility, strong fidelity scale measurement properties, improved supervisor fidelity over time, and the acceptability and perception of positive change by agency leadership. The value of system-initiated collaborations is discussed.

Keywords: Child welfare system, R3, Supervisor, System-initiated

Introduction

Establishing permanency through safety is the primary goal of the child welfare system (CWS). For families who become involved with the CWS, this requires increasing the safety of children to remain in the home or placing them in foster care and taking steps to re-establish safety to reunify them with biological, relative, or adoptive parents. In 1997, the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA; U.S. Public Law 105-89) was passed to emphasize a timely permanency decision for families, which in part includes a provision to terminate parental rights of parents whose children have been in foster care for 15 of the most recent 22 months due to failure to establish safety. With this act came an increase in federal standards for state CWS performance with a focus on indicators of child permanency, safety, and well-being. To meet these goals, CWS caseworkers and supervisors are charged with the task of helping parents establish plans to increase safety and stability. Once children are placed in foster care, reunification is the first permanency option states consider. However, it is the most challenging option to achieve in a plan-based, permanent way within the federal guidelines. Barriers to successful reunification include the skills of workers to provide parents with clear expectations and achievable service plans, and the lack of supportive services to achieve these expectations (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014).

This paper describes a real-world initiative and collaborative effort between a CWS and intervention developers to address the gap in the system's abilities to meet this federal mandate. The evolution of developing a supervisor targeted implementation approach to providing evidence-based interactions with families will be outlined, along with the associated fidelity monitoring system and fidelity measure. Measurement of fidelity is considered key for the development and implementation of any model focused on producing replicable outcomes, and therefore, the measurement properties of the fidelity measure are a key focus of analysis in this paper. The feasibility of implementing the supervisor intervention in real-world agencies, and its potential to produce supervisor change over time then will be described. Finally, qualitative responses obtained from exit interviews with agency leadership focused on perceptions of acceptability and change will be shared in the context of the potential for producing a significant system-level impact.

Background

The R3 model (targeting three distinct reinforcement strategies, described below) and supervision implementation approach was born out of a request by the New York City (NYC) CWS to train their workforce in the use of evidence-based principles in their everyday interactions with caregivers to help achieve the goals of the federal mandate. This system was in the process of adopting evidence-based practices (EBPs) for all families in the foster care system and wanted to ensure that the knowledge learned from the EBPs was generalized into daily caseworker practice and interactions. The EBPs included two parent-group treatments—Keeping Foster and Kin Parents Supported and Trained (KEEP; Chamberlain et al. 2008) and Parenting Through Change (PTC; Forgatch et al. 2013). Both behavioral interventions for families in foster care utilize evidence-based reinforcement techniques shown repeatedly to produce positive outcomes, including stability and permanency (Price et al. 2008). Although select agency staff was identified to provide KEEP and PTC services to the families served by each agency, the CWS leadership wanted all staff (i.e., the workforce) to utilize key components of the models in all aspects of their work (i.e., not limit families receipt of evidence-based services to when participating in a parenting class). In order to optimize the opportunity for system-wide change, the CWS leadership asked the EBP developers to devise an implementation approach that would infuse key elements of the EBPs into all contacts families received by CWS staff. Thus, the charge was to create a model hypothesized to be profound enough to create system change, yet simple enough to be infused throughout a workforce.

R3 as a Supervisor Strategy

Without an existing method for reaching and monitoring a system's multileveled workforce, the challenge was to develop an implementation approach that would maximize the potential reach across the system while working under the real-world conditions of the limited capacity of the EBP developer group (i.e., it was not feasible to monitor the behavior of each and every caseworker as they worked with families). To address this challenge, in collaboration with CWS leadership, the intervention developer team determined that it would be most feasible to target supervisors to reinforce the use of the three Rs with the caseworkers under their supervision (i.e., to focus R3 expert consultation on the supervisors’ ability to coach and monitor their caseworkers’ use of the R3 model).

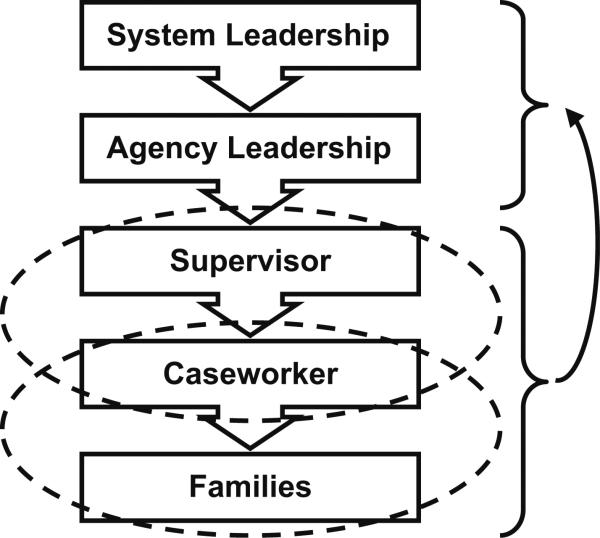

As is shown in Fig. 1, the social context within the CWS involves relationships between multiple agents that affect outcomes for families. Supervisors were selected as the target for the R3 implementation because they are positioned centrally to the organizational leadership and the onthe-ground workforce, both of whom make daily decisions that affect outcomes for families. Given that supervisors are responsible for the daily monitoring of caseworker progress and that the number of supervisors is feasible to thoroughly train, consult with, and monitor, this workforce level was identified as not only the most feasible to target but also the most likely to significantly impact the organizations overall. As noted by Aarons et al. (2012), when interventions are successful in producing positive change, the success of the implementation itself has influence over the culture and climate at the level of leadership. It was determined that supervisors would be trained to utilize the three Rs as part of their supervision approach with caseworkers and in turn, to encourage the use of the three Rs by the caseworkers with the families they serve (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

R3 aims to shape interactions

The Value of Supervision

Recent findings from the Institute of Medicine (2014) are consistent with the supervision target of R3. Specifically, poorly trained staff and limited staff supervision hinder the delivery of effective practices within the CWS, with an IOM call for research to help CWS organizations employ improvement strategies that are well developed, well implemented, and sustainable. Delivery of quality supervision, supervisors being skilled in mentoring and providing feedback, and supportive practice standards have been related to successful child welfare case completion, lower re-entry into the system, as well as CWS staff retention (Cornerstone for Kids 2006; Shim 2010).

Clinical supervision has been conceptualized as a means to increase competence and knowledge among mental health professionals and to improve client outcomes (Falander and Shafranske 2004). Model-specific training and supervision is a feature of current strategies to transport and implement a variety of EBPs for children in community practice settings. Yet, there is a dearth of empirical investigation of clinical supervision competencies. Although both of the EBPs from which R3 is based have a group supervision component and thus conducting group supervision is a natural extension of the models, evaluation of this process has not been conducted. Even more specifically, this supervision process has typically been conducted within mental health community agencies, not CWSs. Specific focus on the nature and effects of supervision on the implementation and outcomes of EBPs in community settings is lacking (Beidas and Kendall 2010; Schoenwald et al. 2009). Evaluation of the R3 supervision strategy directly addresses this gap.

The Importance of Measuring Fidelity

As with any EBP, in order to evaluate the R3 supervision strategy, a standardized method of determining if R3 is what is being delivered is needed. Fidelity includes an assessment of adherence and competency in delivering an intervention (Perepletchikova et al. 2007), and although the measurement of fidelity is challenging, it is essential. The ability to measure the quality of delivery of R3 is key to identifying what aspects of the intervention are important to achieve outcomes, and for determining if those aspects are delivered well. Integrity of model delivery at both the supervision and direct provider level has been linked to client outcomes (Schoenwald et al. 2009). Practically, standardized assessment of model delivery allows for monitoring of change over time and an objective guide to inform coaching toward improved model delivery.

Summary

Both the R3 model and implementation approach are viewed as a package, such that future rollouts of R3 in other CWSs would by definition target supervisors. This real-world initiative provided the opportunity to pilot integral components necessary for a larger implementation evaluation. Specifically, this pilot allowed for development of a fidelity measurement tool, which in turn allowed for evaluation of the potential to change supervisor behavior over time, and the feasibility of implementing a model that targeted an entire workforce. There also was the opportunity to assess the acceptability of R3 amongst the pilot agencies, important factors for future scale-up. Although the success of the overarching goal to increase the frequency and pace of successful treatment plan completion by families involved in the CWS is not yet known, this developmental project allowed key aspects of the model to be piloted.

Method

Participants

R3 was piloted within the five NYC foster care agencies already engaged in the adoption of KEEP and PTC. Two agencies had multiple locations in different boroughs in NYC that operated independently of one another and under different organizational leadership. Therefore, these locations were treated as independent sites for a total of 9 sites. Supervisors (n = 114) caseworkers (n = 281), and agency leaders (n = 23) participated in trainings. Of the supervisors, 51 directly oversaw caseworkers and were the primary target of the pilot evaluation. Across roles, the majority of participants were female (90.2 %) with ages ranging from 21 to 64 years.

R3 Model Development

Similar to the KEEP and PTC models from which R3 is derived, supervision strategies were grounded in social learning theory; people learn, and their behavior is shaped, through their interactions with others by observation, reinforcement, imitation, and modeling (Patterson et al. 1992). People modify their behavior by observing reinforcement received and provided by others and individuals exist within and respond to their environments in an adaptive way (i.e., the behaviors being reinforced will increase; Bandura 1971). The R3 supervision model utilizes group supervision to encourage group based learning and problem-solving involving interactions with, and case management service delivery to, families involved in the CWS. Supervisors are trained to use the same reinforcement strategies and principles during supervision of their casework staff as the caseworkers are trained to use during interactions with families (Fig. 1).

Selection of the Three Reinforcement Strategies

When asked to devise a method for impacting everyday interactions between CWS caseworkers and the families on their caseload, the EBP developers first were challenged with deciding what aspects of the EBPs were relevant, simple, and most likely to be easily adopted as part of the organizational culture, while also promoting the greatest potential for significantly helping families move through the CWS. Both the KEEP and PTC models rely on a foundation of parent management training that is strongly grounded in using positive reinforcement to modify behavior. Three key reinforcement targets (the three Rs; Table 1) were selected from those common across the two EBPs that have demonstrated success in achieving positive changes in parenting behavior across a range of child welfare involved populations: Reinforcement of (1) efforts (2) relationships and roles, and (3) small steps toward goal achievement. Reinforcing positives has been directly linked to improved outcomes in previous research in child welfare populations (Chamberlain et al. 2008; Price et al. 2008; Leve et al. 2002; Ramsey et al. 1989).

Table 1.

R3 approach including reinforcement targets and principles, and example associated FRI_S item

| Supervisor–caseworker | Caseworker–caregiver | |

|---|---|---|

| R3 targets | ||

| 1. Reinforcement of effort Example FRI_S: discussion included specific information on reinforcing caregivers’ efforts |

“Nice job escorting Mrs. Jones to her mental health assessment. I am sure that she feels supported by you making that extra effort to help her get to her appointment.” | “I really appreciate that you figured out the subway system to make your visit on time. Sally looked thrilled when she saw that you were waiting for her!” |

| 2. Reinforcement of relationships and roles Example FRI_S: discussion included reinforcing caregiver-child relationships |

“I really appreciate that you problem-solved with dad about how he could approach homework with the boys. I know that is a new role for him and with your support he will increase his confidence and the kids will feel it.” | “Zachary is such a polite and kind child. I see him sharing with other children in the waiting room. You have done a really nice job teaching him skills that are important as he develops friendships.” |

| 3. Reinforcement of small steps Example FRI_S: discussion identified small steps caseworkers took or will take with families. |

“Terrific work breaking the process down for mom of identifying a pediatrician. It was really smart to make sure that first she had the children's medical cards so that she could start to identify which doctors accept Medicaid in her neighborhood.” | “Great work calling the pediatrician office and scheduling an appointment for the children's wellness exam! Let's make a list of questions that you can take with you so that you are sure to understand the medications that they each take and why. You have been taking in a lot of information lately and are doing a great job keeping organized!” |

| R3 principles | ||

| 4. Use strength-focused language Example FRI_S: discussion included examples of supportive and encouraging language. |

“I can tell that you are really making efforts to get your documentation into the charts in a timely way. I appreciate you rearranging your schedule to set aside time for note writing. Let me know if I can help you as you get used to the new system.” | “You did such a nice job listening to what the judge had to say in court yesterday. I know that was hard to hear that we have more tasks to add to the service plan, but I know that you can do it. I know you are working to get your kids home quickly!” |

| 5. Notice normative/appropriate behavior Example FRI_S: caregiver and family strengths were used in case planning. |

“I really appreciate that you have been arriving to our meeting together on time. It is terrific when we are able to use all of the time to cover case discussions. Thanks for that!” | “Your house looks terrific! I know that it can be hard to keep it clean with so many kids of different ages, but you seem to really have developed a successful system!” |

| 6. Use a scientific approach (observe and reinforce Example FRI_S: solutions and strategies were discussed in behavioral terms. |

“I have noticed that you have been offering a lot of support to the new caseworkers near your cubicle area. You are a real leader on our team!” | “I notice that you have really been making efforts to bring healthy snacks to the visit. I found these coupons for the store in your neighborhood that might be helpful if you would like them.” |

| 7. Take opportunities to smile and laugh Example FRI_S: the atmosphere of the meeting was friendly and supportive (e.g., supervisor smiles, uses humor) |

“I am so sorry that baby Julia spit up on you right after mom handed her back after the visit! I know that was awful, but the look on your face was hilarious.” | “How funny that Jimmy decided to create his crayon masterpiece on the wall the very first day of your first overnight visit! I have a similar mural at my house! HaHa.” |

Examples provided of interactions between supervisors and the caseworkers they supervise, and between caseworkers and families on their caseloads

The simplicity and yet profound impact of these three methods of reinforcement made them ideal targets to select as the evidence-based techniques to infuse within the daily practice of the child welfare workforce. Moreover, these three Rs were identified as those that best related to the goal of the CWS to move families toward treatment plan completion more quickly in order to improve the system's goals of meeting the federal mandate for establishing more rapid and stable child permanency outcomes. Indeed, previous research with families in the CWS suggests that when caregivers are provided strategies for steady progress on a comprehensive set of goals, they are most likely to successfully complete their CWS treatment plans (Marsh et al. 2006).

Selection of R3 Principles

The next challenge was the development of an organizational culture that emphasized the three Rs. Four theoretically based principles from the evidence-based behavioral parenting interventions (Table 1) were selected to provide a framework for all interactions within the case management team. The principles include (1) use of strength-focused language; (2) noticing normative appropriate behavior; (3) observing and reinforcing; and (4) taking opportunities to smile and laugh. The goal is for these basic principles to be utilized when interacting with caregivers and when CWS staff is interacting with each other. Table 1 illustrates this parallel process with examples between supervisors and their caseworkers, and between caseworkers and their families. Previous research has suggested that when caregivers in the CWS feel a supportive versus adversarial relationship with their caseworkers that their children are more likely to establish permanency (Altman 2008).

Informing Implementation Through Collaboration

As noted previously, the five organizations adopting R3 already were in the process of delivering a suite of EBPs to foster, kin, and biological parents involved in the CWS. Thus, the general organizational infrastructure and preparedness of the agencies to adopt and adhere to quality assurance components was already known. This allowed the developers to leverage previous knowledge and resources (e.g., video recording equipment, virtual consultation) to create a rigorous implementation plan that would be feasible and cost-effective for the organizations. Greater attention, therefore, could be provided to understanding the culture and needs of the on-the-ground workforce who were targeted directly by R3. The developers were able to prepare their training, ongoing consultation methods, and their own expert consultation staff with input from the supervisors and caseworkers being asked to change their behavior.

Initial Training

Supervisors participated in a 1-day training using collaboratively developed training materials. This pragmatic training provided direct education regarding the three Rs and the four R3 principles. Training components included slide presentations, role-plays, and presentation of video clips. Training focused on the parallel process of providing supervision to caseworkers utilizing R3 techniques and principles, and of the caseworkers’ use of R3 techniques and principles with the families on their caseloads. A 3-h caseworker training was provided to all caseworkers in the basic strategies, specific techniques, and principles of R3.

Both sets of training took place over several days in the same week to address workforce issues. Because CWS staff work with a vulnerable population, it is not feasible to take an entire workforce within an agency “offline” simultaneously. Both supervisor and caseworker trainings included outlining of the basic expectations for R3 deployment (i.e., group supervision, video recording, observation by an expert consultant). All trainings were provided by the developers.

Fidelity Monitoring System and Measure Development

Consistent with other EBPs, it was determined that ongoing coaching, monitoring, and feedback would be necessary to create a cultural and behavioral shift that would be sustained throughout the CWS organizations. Given the observational fidelity monitoring system utilized by KEEP and PTC (i.e., both interventions utilize video recording of sessions that are uploaded to a secure web platform for observation and fidelity coding by the expert consultants), the decision to utilize a parallel system for monitoring of R3 was logical. The goal was to develop a set of supervisors within each of the agencies who demonstrated consistent competency in the R3 model, so that their use of R3 would be modeled throughout the agency to other less competent supervisors, caseworkers, and any new staff who were hired.

Provision of Rapid Feedback

Fidelity feedback includes the monitoring of adherence to intervention components as well as competency to ensure that the components are delivered well (Schoenwald et al. 2014). In R3, the goal is to provide feedback to supervisors quickly and accurately to maximize the potential that families receive consistent exposure to the three Rs. Leveraging the video recording and web-based video upload system already in place for monitoring of KEEP and PTC, supervisors recorded their supervision sessions via laptop computer and immediately uploaded their videos to a secure, encrypted system for feedback. The R3 expert consultant was automatically sent an email notification that a new video was uploaded. The expert consultant watched one video per supervisor per month; written feedback then was uploaded to the fidelity website to be reviewed by the supervisor.

Written feedback included reinforcement of what the supervisor was doing well (e.g., with provision of timestamps of concrete examples), one or two key target behaviors for change with suggestions from the meeting for how to perform the behavior using R3 strategies, and a small step that the supervisor should take in the upcoming month to address behaviors in need of change (see Table 2 for example feedback). Feedback was provided in a phasic manner such that supervisors were first provided heavier positive reinforcement than corrective suggestions, then positive reinforcement with more constructive criticism, and finally greater suggestions for generalization of skills with a link to model theories.

Table 2.

Example supervisor feedback from expert consultant across the phases of consultation using the same case example

| Phase 1: primarily supportive feedback |

| What a fun R3 supervision meeting to watch. You are doing a terrific job creating an environment where your caseworkers feel comfortable sharing both their successes and challenges throughout the week |

| You did an excellent job highlighting and reinforcing the efforts of your workers (see 28:50, 32:00). It is nice how you give them credit for steps they have taken with the families they are supporting (see 46:10 and 42:00). For example it was wonderful to hear you praise your newest caseworker for staying late to meet with the parent who just obtained a new job. It was obvious that she felt appreciated and it was nice for her to receive praise in front of her peers |

| Thank you for your ongoing hard work and efforts to create a strong R3 team. They clearly feel supported by you and it is nice to see you all laughing so much together under the stress of the job. Well done! |

| Phase 2: supportive with constructive feedback |

| Another well-done supervision meeting! This meeting rated a strong yellow! |

| You continue to do an excellent job highlighting and reinforcing the efforts of your workers (see 28:50, 32:00). You do a nice job giving them credit for steps they have taken with the families they are supporting (see 46:10 and 42:00) |

| A next step might be to problem-solve with your team ways to reinforce parents’ small steps and efforts. For example, it could be fun for the group to brainstorm ways to tangibly reinforce the mom who came in late to meet with her caseworker after a long day of working her new job. Mom might respond well to a certificate or a gold star sticker! |

| You have such a nice frame for the families’ less-than-ideal behaviors, and you clearly help your team to focus on giving their families the benefit of the doubt, which can help them not get stuck on the frustrations that are a natural part of the job (See 6:30 and 50:16). That is a terrific strategy and over time it will be great to see your caseworkers start to do that on their own! |

| Thank you for your ongoing hard work and efforts to create a strong R3 team! They clearly feel supported by you and it is nice to see you all laughing so much together under the stress of the job. Well done! |

| Phase 3: generalization and linkage to behavioral theory |

| Another well-done supervision meeting! Your meetings have consistently been rating in the green! |

| You have developed strong competency in highlighting and reinforcing the efforts of your workers (see 28:50, 32:00) and consistently give them credit for steps they have taken with the families they are supporting (see 46:10 and 42:00). It is terrific to see how you have created a culture where your seasoned caseworkers are offering support and suggestions to your newest caseworker. She responded so well to being praised for staying late to meet with her parent who just started a new job. And it was really fun to hear the group brainstorm ways to tangibly reinforce the mom for showing up after her long day of work. |

| You also have such a natural way of helping your caseworkers reframe the families’ less-than-ideal behaviors. They seem to really be catching on to this on their own and there has been a notable shift over time in the language they use to describe challenging case (See 6:30 and 50:16). This not only relates to the R3 principle of using strength focused language, but also of using a scientific approach to observe and reinforce which will help your caseworkers be able to manage challenging situations “on the fly.” You've done a terrific job of creating a very strong R3 team! |

Group Expert Consultation

Monthly group expert consultation allowed for shared learning and support, and targeting of specific organizational needs across supervisors in an agency (e.g., problem-solving how to provide tangible reinforcers to caregivers under current agency policies). Group consultation provided feedback that was relevant across supervisors from an agency, problem-solving, role plays for how to address behaviors in need of change, and examples from peers who performed the behaviors well. In other words, the consultation process also relied heavily on social learning theory (Patterson et al. 1992), similar to the EBPs from which R3 was drawn. Consultation groups ranged between three and 12 supervisors.

Measures

Fidelity of R3 Implementation for Supervisors (FRI_S)

Because R3 was a newly emerging practice, the fidelity coding system was built simultaneous to the initiation of implementation. After several months of observing videos, providing coaching, and identifying behaviors observed for quality R3 supervision sessions, the fidelity coding system was operationalized enough to provide a standardized assessment of R3 delivery.

The resulting Fidelity of R3 Implementation for Supervisors (FRI_S) was a 15-item, 5-point Likert scale designed to measure the Content (e.g., “Discussion identified small steps case workers took or will take with families,” and “Discussion included focus on small steps caregivers took or could take during the next week”) and Process/Structure (e.g., “Case workers were reinforced for small steps accomplished on their cases”) of the group supervision meetings. Items were rated by the expert consultant based on a review of the video recording of the group supervision meeting. Table 1 provides example FRI_S items for each R3 target and principle.

A competency threshold was established for the FRI_S to help in providing feedback to supervisors, without focusing on actual fidelity scores (red < 50 %; yellow = 51–79 %; green ≥ 80 %). Previous work with KEEP and PTC suggested that when trainees are provided exact scores, many individuals become focused on incremental changes in scores from one feedback session to the next rather than the more meaningful and targeted feedback about consistent intervention delivery. Table 2 illustrates how FRI_S performance is integrated into feedback.

Although implementation began in September 2013, because the development of the FRI_S fidelity scale was simultaneously evolving, tracking of fidelity data began in March 2014. All supervision groups were transferred to the non-developer expert consultant prior to the tracking of fidelity (i.e., no nesting at the rater level). The final pilot group supervision recording was collected in June 2015.

Exit Interviews with Agency Leadership

At the end of the pilot, exit interviews were conducted with each of the agency's leadership (two leaders, interviewed together, per agency) to gain their perspectives on the influence that the introduction of R3 had on their agency. All interviews were conducted by the primary developer and were posed as an opportunity to provide input and lessons learned into the ongoing refinement of, and potential future larger scale-up of the R3 model. Although a true qualitative analysis is not the focus of this paper, responses will be shared to provide insight into the potential feasibility and acceptability of R3 for future scale-ups.

FRI_S Data Analysis Strategy

In order to ensure that our measurement of R3 fidelity was psychometrically sound, the FRI_S was evaluated using Rasch measurement modeling. This approach allows for an assessment of instrument performance as well as an indication of which items are easiest or hardest to perform well thereby providing an indication of which target areas to emphasize in training. The Rasch model, a single parameter logistic model, is a restricted case of a measurement model based in Item Response Theory. The model is expressed by:

where Pni is the probability of a correct response by person n with ability level Bn on item i with difficulty level Di (Rasch 1960; Wright and Mok 2000). As reflected by person “ability” and item “difficulty,” the model has traditionally been used for educational measurement and items with dichotomous, incorrect/correct answers. However, this standard model is readily extended to rating scale data (Wright and Masters 1982), which are ubiquitous in social science research and practice. Several features of the model can be illustrated using the FRI_S as an example. The items (i.e., R3 components) are assumed to have different levels of “difficulty,” with some being easy to implement as intended and others being more challenging. Likewise, the persons (i.e., supervisors) are assumed to vary in their levels of fidelity. Following from this, a novice supervisor being rated on a challenging R3 component (e.g., “Discussion included reinforcing parent–child relationships”) would be expected to receive the lowest rating (i.e., Not at All), but on an easy component (e.g., “The atmosphere of the meeting was friendly and supportive”), the rating should be higher. Likewise, an expert-level supervisor being rated on a challenging component would be expected to receive a high rating, and on an easy component, the rating should be the highest (i.e., Very Much). This reflects the “probabilistic” nature of the model, where the likelihood of a particular rating is the result of the supervisor's level of fidelity and the R3 component in question. The results of the model provide separate “scores” for the items and supervisors, an evaluation of dimensionality, an evaluation of rating scale performance, multiple indicators of reliability, fit statistics for items, and an evaluation of the suitability of the items for the sample being measured. The models were implemented using WINSTEPS software (v3.90.2; Linacre 2015).

Results

The following outcomes target the measurement properties and instrument performance of the FRI_S, which in turn was used to evaluate changes in supervisor behavior over time. Agency leader reports related to feasibility and acceptability of the R3 model also are reported.

Performance of the FRI_S as a Measurement Instrument

The final FRI_S data-set was comprised of 265 sessions across 51 supervisors who were in 9 agencies as rated by a single expert consultant. The average number of sessions rated per supervisor was 5.2 (Min = 1, Max = 14, SD = 3.6). The results aim to provide a thorough evaluation of the FRI_S's current use in feedback. Namely, the FRI_S is intended to differentiate at least three levels of fidelity (red, yellow, green) as the basis of feedback to supervisors. Results are presented as related to key measurement questions.

Are There Multiple Dimensions of R3 Fidelity?

To evaluate the FRI_S, the first step was to determine whether there was meaningful dimensionality in the data. The Rasch measurement model assumes that items measure a single dimension, and if there are multiple dimensions, separate analyses are conducted for each. Dimensionality was evaluated by performing a principal components analysis on the standardized Rasch item-person residuals (Rasch PCA; Smith 2002). The residual variance should be random, and if meaningful structure is found, this suggests dimensionality. The analysis provides three main indicators of dimensionality (Linacre 2015): the percentage of variance explained by the item and person measures (<60 % reflects dimensionality), the eigenvalue for the first contrast in the residual variance (≥2.0 reflects dimensionality), and the percentage of variance explained by the first contrast (≥5 % reflects dimensionality).

The Rasch PCA was performed on all available FRI_S sessions and separately for each of the first five sessions. The results are summarized in Table 3. Across models, the percentage of explained variance was high; however, the eigenvalue and the variance explained by the first contrast are suggestive of dimensionality. One suspected dimension was formed by the Content items (5 of 8 loading >.30 on the contrast) and the other by the Process/Structure items (5 of 7 loading <−.30 on the contrast). However, these dimensions were moderately to strongly correlated, ranging from .30 to .73 across models. Two supplementary analyses were performed to determine the meaningfulness of this dimensionality. The first was parallel analysis, or an empirical scree test (O'Connor 2000). Parallel analyses attempts to find structure in randomly generated data with the same number of items and observations. There is significant dimensionality when a factor in the real data has a larger eigenvalue than the same factor across multiple iterations of random data. Using all of the data, across 100 iterations of random data, the 95th percentile eigenvalue for the second factor was 1.4, which is the same as the second factor of the FRI_S data. This suggests that there is a single dimension.

Table 3.

Dimensionality indicators from PCA of standardized Rasch Residuals

| Session | % variance by measures | Eigenvalue contrast 1 | % variance contrast 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 60.7 | 2.9 | 7.5 |

| 1 | 57.4 | 3.9 | 11.1 |

| 2 | 54.8 | 3.5 | 10.7 |

| 3 | 67.1 | 3.5 | 7.8 |

| 4 | 65.9 | 3.1 | 7.0 |

| 5 | 69.1 | 3.7 | 7.6 |

The next step was to perform an item bifactor model. The bifactor model is an IRT-based measurement model where every item loads on a general dimension and one or more smaller, specific dimensions (Reise 2010, 2012). The results indicate whether the items primarily measure the general dimension or the specific dimensions. One Content item (“Discussion noted documenting parent accomplishments”) and one Process/Structure item (“Supervisor managed the meeting time well, covered >2 cases”) loaded weakly, but all other items loaded ≥.40 on the general dimension and inconsistently on the specific dimensions. Given these results, the subsequent analyses are based on a single dimension of R3 fidelity.

Does the 5-Point Rating Scale Perform as Intended?

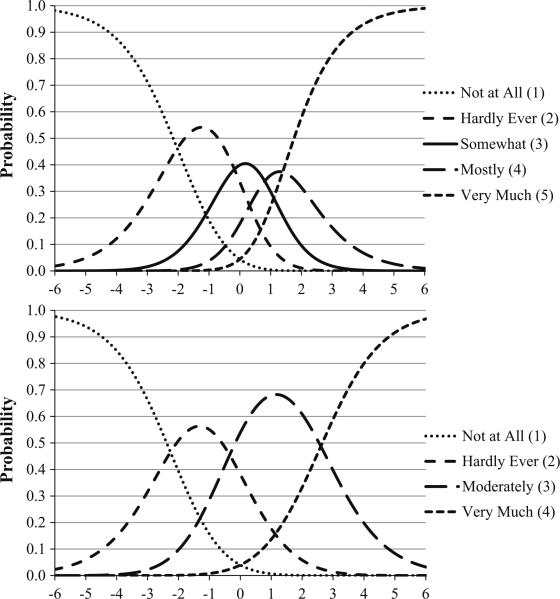

The Rasch rating scale analysis determines the extent to which raters interpreted and utilized the rating scale categories as intended by the instrument developers. The rating scale analysis was based on the data from all sessions and was performed as described by Linacre (2002). Specifically, the analysis evaluated a common five-point rating scale structure across the entire pool of items (i.e., rather than each item receiving a unique rating scale structure). The primary results are summarized in Fig. 2, which illustrate the probability of a response in a specific rating scale category depending on a supervisor's level of fidelity and the difficulty of the fidelity component being assessed. In the top panel, the x-axis represents the latent dimension of R3 fidelity. The left side reflects supervisors with low fidelity and R3 components that are very difficult (i.e., a high probability of a low rating), and the right side reflects supervisors with high fidelity and R3 components that are very easy (i.e., a high probability of a high rating). The y-axis represents the probability of a response in a particular category. There are five plotted lines, one for each rating scale category. Taken together, given a supervisor with low level fidelity and an R3 component that is difficult, the probability of a rating of 1 (Not at All) is high. As the level of fidelity increases and the difficulty of the component decreases, the probability of this rating drops and the probability of a rating of 2 (Hardly Ever) increases and becomes the most probable response. This pattern should continue for each subsequent category. Although categories 3 (Somewhat) and 4 (Mostly) do emerge as the most probable response, the probabilities are nearly equal to the adjacent categories. This indicates that Hardly Ever and Mostly were not well-discriminated and are not distinct. Of note, each category was well-utilized, with the percentage of ratings being 1 = 9 %, 2 = 22 %, 3 = 23 %, 4 = 22 %, and 5 = 24 %. Despite this, categories 3 and 4 were not well-differentiated as was further evidenced by the Rasch-Andrich thresholds, which quantify the distance between the adjacent categories. For a 5-point scale, the distance should be ≥1.0 logits (Linacre). Categories 2 and 3 were well-discriminated (1.86 logits apart), categories 3 and 4 were reasonably well-separated at 0.98; category 4 was not well discriminated from 5 with a distance of 0.58 logits. To further discriminate category 4 from category 5, categories 3 and 4 were combined, and the optimized 4-point scale is illustrated in the bottom panel of the Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

FRI_S rating scale category probability curves for the original 5-point scale (top panel) and optimized 4-point scale (bottom panel)

Are There Items that Perform Poorly?

The results provide item fit statistics that identify items that do not fit the model. Misfitting items contribute more noise than precision to the measurement of fidelity, and generally are candidates for removal or revision. The statistical indicator for misfit was the Outfit mean square statistic, with values in excess of 1.4 reflecting significant misfit (Bond and Fox 2007). Across models, there were four items with some indication of noisy performance, two of which were more consistently problematic. The less severely misfitting items were Item 6 (“Discussion noted documenting parent accomplishments”) and Item 10 (“The atmosphere of the meeting was friendly and supportive”), misfitting in two and one models, respectively. Of the more severe items, Item 13 (“Supervisor managed the meeting time well, covered >2 cases”) was significantly misfitting across all models, and item 15 (“Supervisor ended group well [on time, encouraging statements]”) was misfitting in 3 of 6 models. These items (as described subsequently) reflect easy components. The misfit statistic suggests that these items may receive lower ratings for some supervisors who otherwise have high levels of fidelity and who would be expected to have received high ratings. Upon discussion with the developers and raters, these items were ones that were ranked as less of a priority in consultation sessions in the beginning of implementation. That is, during the consultation and shaping process, expert coaches selected specific supervisor behaviors to target in feedback so that feedback was not overwhelming for supervisors. These misfitting items were identified as those that were noted but not stressed for behavior change initially. For the subsequent results, these items were removed. Though these items will continue to be included in future assessment of group supervision facilitation, they will not be included in FRI_S scores.

How Reliable are the Fidelity Measurements?

The results provide three indicators of reliability for the supervisor fidelity measurements. As described by Schumacker and Smith (2007), Rasch separation reliability ranges from 0 to 1 and reflects proportion of true variance in the total variance of fidelity scores. Across models, Rasch separation reliability was high, ranging from .86 to .92. Related to this, the Rasch separation index ranges from 0 to infinity and indicates how “spread out” the supervisor measurements are based on the sample of items. Larger numbers reflect a more fine-grained measurement of fidelity. The separation index was strong, ranging from 2.53 to 3.30, which indicates that approximately 3 distinctions can be made in the level of R3 fidelity for this sample of supervisors. The ability to differentiate 3 levels of R3 fidelity is well-suited to the use of the FRI_S as a tool for routine fidelity monitoring and feedback. Indeed, the current practice, supported by this finding, is to provide feedback with “red, yellow, and green” levels of fidelity A third statistic, strata, was computed, which ranged from 3.71 to 4.73, suggesting that approximately 4–5 distinct levels of fidelity can be discriminated in the sample of supervisors.

How Well Do the Items Target the Sample of Supervisors?

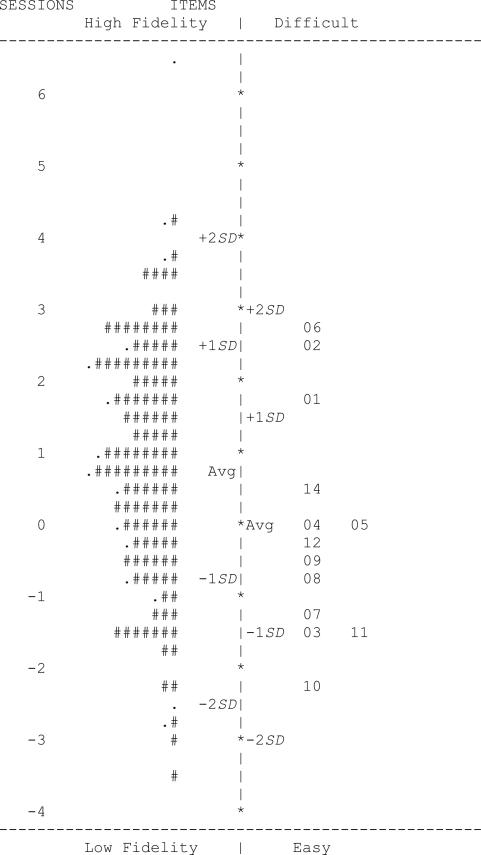

The Rasch model provides separate information about items and supervisors, from which, it is possible to evaluate how well-suited the items are for the sample. Ideally, there will be a wide range of items, a wide range of supervisors, and the two distributions will largely overlap. This means that the items are “targeted” to the sample and it is possible to measure the full range of supervisors, from novice to expert. The results are illustrated in Fig. 3. The scale of measurement for the items and sessions, located on the left, is log odds units (i.e., logits). On the left, the vertically-oriented distribution of “#” and “.” symbols are coded sessions, with each “#” representing two sessions and each “.” representing one session. Sessions located at the top are those with the highest levels of fidelity, and those at the bottom, the lowest. On the right is the distribution of items, with those at the top being the most difficult to implement and those at the bottom being the easiest. On both sides of the vertical dividing line, there are labels for sessions or items that are average, 1 SD above and below the mean, and 2 SDs above and below the mean. The figure shows that each distribution covers a wide span, and they overlap extensively. The items have a tendency to be slightly easy; however, the full range of sessions is assessed because of the 4-point rating scale. In other words, the very top- and bottom-performing sessions are assessed by the highest and lowest rating scale categories for these items.

Fig. 3.

Rasch item-person map based on all session data

Performance Over Time

After evaluating validity evidence for the present use of the FRI_S based on instrument content, response processes, and internal structure, analyses were conducted to examine supervisor behavior change over time.

Did R3 Fidelity Improve Over Time?

Based on the final measurement model, and including the revised 4-point rating scale, a raw average score was computed for each session. These scores were analyzed to evaluate the impact of R3 on supervisor fidelity over time. A challenge with the data is that the FRI_S measurements did not begin until approximately 6 months after the start of R3 implementation. Moreover, given the real-world context, there was supervisor turnover, introducing variability in the duration of R3 exposure across supervisors. Multiple strategies were considered for coding time, including the order of session uploads from each supervisor, the number of months between each upload and the supervisor's first upload, and the number of months between each upload and the start of R3 delivery. Each of these produced consistent results, and the results from the latter (time from the onset of R3) are reported here.

The impact of R3 was evaluated using a two-level mixed-effects regression model (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002) with repeated measurements of R3 fidelity (level-1) nested within supervisors (level-2). Of note, because the linear time term is centered around the start of R3 and fidelity measurement did not begin until later, the model intercept is an estimate and not directly meaningful for interpretation. Results indicated that there was significant linear change in R3 fidelity over time, β10 = 0.03, SE = 0.01, T (213) = 5.27, p < .001. Thus, at the time of the first R3 fidelity measurement, approximately 6 months after the start of R3, the average fidelity score was predicted to be 2.5 on the 1–4 rating scale, or half-way between Hardly Ever and Moderately. Eighteen months after the start of R3 (i.e., the median duration across supervisors), the average fidelity score increased to 2.9, nearing Moderately, and by 21 months, the score increased to 3.0.

Across supervisors, based on the deviance test, there was not significant variability in linear slopes, χ2 (2) = 1.53, p < .05, suggesting that the rate of change over time in R3 fidelity was generally consistent across supervisors. Importantly, these findings held when adding dummy-coded fixed effect indicators to control for the main effect of sites. Likewise, when adding cross-level interaction effects between the site indicators and the linear slope term, and using planned comparisons to obtain tests for all pairs of sites, there were no statistically significant differences in the rates of change in R3 fidelity across sites.

Did Use of the Three Categories of Fidelity Demonstrate Meaningful Change Over Time?

As previously noted, supervisors were provided feedback regarding their performance using a color-coded system. Specifically, “red” was defined as fidelity score of 50 % or less, “yellow” as 51–79 %, and “green” as 80 % or more. At the time of each supervisor's first coded session (i.e., approximately 6 months into implementation), 86 % of supervisors were not within the green fidelity range; 16 and 71 % were in the red and yellow range, respectively. Over time, however, R3 fidelity improved considerably, with 47 % of supervisors in the green range, 51 % in the yellow range, and only 2 % in the red range.

The descriptive results are consistent with the findings from an ordinal mixed-effects regression model for change over time in the log-odds of being in the red, yellow, or green range. Specifically, for the first coded session, the probability of being in the green range was 3 %; 18 months later, this increased to 22 %. Also of note, and meeting the primary goal of the R3 rollout, every agency had at least one supervisor in the green fidelity range at the end of the implementation pilot suggesting the feasibility of developing R3 competency over time.

Agency Leader Perceptions of Acceptability and Change

Although this pilot is limited by the fact that the entire workforce was not examined for change, responses collected from agency leadership as part of exit interviews at the conclusion of the pilot suggested that R3 was successful in producing significant change. Leadership reported a notable difference in the approach that staff members took with families and indicated that this influenced the overall agency climate, such as the level of tension in agency waiting areas. One agency leader reported that the number of incidents of having to call the police decreased from 12 incidents/week to 2 incidents/month. Another leader noted an overall change in how caseworkers supported one another in their work, which filtered down to parents: “There was a shift in their thinking when I asked them, back in September and back in January the response was very different. When I left that room I was pleasantly surprised because there were a lot of workers...I thought I was going to get a lot of [flack] but people spoke about being able to really form good relationships with their families. Parents were not seeing them as villains anymore. They had got to a place where they felt that they knew each other's clients...To get that feedback—I was pleasantly surprised. It's making a difference. They're feeling that it's made a difference for them.”

Leadership offered supervisors praise and recognized them as “leading the effort” amongst their organizations and supervision groups. Similarly, supervisors reported liking the approach once they recognized changes in how the caseworkers on their teams were interacting with parents. As one supervisor noted, she saw that caseworkers began to “guide birth parents in identifying barriers and work with them in helping them develop and implement interventions and/or corrective strategies rather than just telling birth parents what actions they should take in order to move forward.”

Discussion

Although the 1997 Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA; U.S. Public Law 105-89) was introduced to encourage the CWS to work more expediently and effectively toward establishing child and family permanency and safety, little was provided by way of support to help the system implement behavioral changes to meet these goals. Recently Title IV-E Waivers have been awarded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to several states selected in response to a competitive RFA, with awarded states allowed greater flexibility in how they utilize their federal funds to address their most challenging CWS problems. The goal is to increase the use of EBPs and provide resources toward prevention, however, little support is provided to help organizations to meet these changing priorities. As demonstrated by the pilot in NYC, the R3 supervisor-targeted approach might be a method to help states achieve these goals.

Collaboration in Intervention Development

As previously noted, the R3 pilot was initiated by a CWS rather than by EBP developers. It was the idea of the system to collaborate with known developers to establish methods for training their workforce to utilize techniques and strategies grounded in EBP in their everyday interactions with the families they serve. In collaboration with the CWS leadership, the EBP developers identified key concepts that were thought to be most likely to increase the potential for the CWS to meet federal mandates. The CWS leadership worked with developers to recognize challenges that might be encountered when targeting an entire work-force (e.g., inability to take an entire workforce offline at once). The EBP developers, in turn, collaborated with the workforce to understand their daily challenges, and to establish an understanding of their current practice. This pilot provides an example of how both the inner and outer context not only is necessary to consider for successful implementation (Aarons et al. 2011) but, importantly, how these contexts can drive the development of interventions and implementation approaches.

Development of Standardized Fidelity Coding and Feedback

Although the self-report of agencies regarding the perceived change in positive behavior over time is necessary for ongoing collaboration and the iterative developmental process, the creation of the FRI_S and subsequent observational fidelity coding provided strong empirical support for these outcomes. Revised to a 4-point rating scale, the FRI_S had strong evidence for its valid use as an instrument for measuring supervisor R3 fidelity. Specific items known to the developers as being emphasized less during the coaching process demonstrated the greatest amount of noise in Rasch modeling, and those items known to be most challenging to developers (e.g., “Discussion included reinforcing parent–child relationships”) were those that were most difficult to achieve high competency in for supervisors.

The FRI_S demonstrated an acceptable range of easy and hard items, which is ideal for coaching staff being asked to make significant behavior change in their way of conducting their everyday job responsibilities. When creating system change, it is helpful to have items that can be reinforced positively as operating well, and leveraging those skills to help build upon for correcting more challenging behaviors. The FRI_S provides a standardized method of identifying these workforce needs, which is essential as R3 is implemented elsewhere with a range of expert consultants and supervisors.

Success of Implementing R3 Across Agencies

As shown by outcomes of change in supervisor behavior over time, the supervisor-targeted implementation strategy was feasible to implement and successful in promoting competency in the R3 model. Although very few supervisors were operating within acceptable fidelity ranges (i.e., green) at the initial coding period, 6-months post-training, by the end of the demonstration pilot nearly half of all supervisors were operating with fidelity. Importantly, as was the goal of the pilot, every agency ended with at least one supervisor operating with fidelity and very few supervisors remained in the red range. Green-level supervisors were identified to carry forward the modeling of R3 behavior across their agencies once the pilot had ended in hopes of sustaining the noted cultural and behavioral changes. Of note, the number of supervisors meeting fidelity standards was correlated with the size of the agency; the agency with only one supervisor was a very small agency and the largest agency had the greatest number of supervisors within the green range.

Outcomes related to fidelity suggest that, as predicted by the CWS leadership, their workforce was in high need of learning skills that were consistent with basic evidence-based principles. The low odds of obtaining a green rating 6-months into the implementation suggests that these skills were challenging to adopt. This is consistent with the IOM (2014) finding that poorly trained staff and a lack of supportive supervision hinder the delivery of effective practices within the CWS. However, the collaborative effort between the CWS, the EBP developers, and the workforce was successful in meeting the overarching goals of the pilot. These outcomes are promising for the potential to implement system-wide change for a very challenging workforce delivering services to a highly challenging population of families.

Limitations and Next Steps

This manuscript describes the developmental process that was undertaken to create an implementation strategy to meet a system's goals of infusing evidence-based techniques throughout a workforce. The R3 model is the packaging of those techniques identified as being most relevant to the CWS's goal of increasing timely permanency. Given the developmental pilot nature of this project, the primary aim was to develop the strategy and assess the feasibility of implementing it successfully to create change. Nevertheless, several limitations are important to note for the next steps.

First, it should be noted that although the FRI_S fidelity coding scale demonstrated adequate psychometric properties and meaningful change over time, important assessment remains. For example, intercoder reliability was not assessed. Nor was the highly important relationship between FRI_S scores and overall system-level outcomes. Now that the FRI_S has been established, a greater depth of evaluation is essential.

Second, R3 was developed and implemented across a limited number of agencies in a system that is motivated to create change to meet the federal mandates. It is unknown how R3 might be received by a CWS that is not as open to practice change. However, it is worth noting that although for the current pilot, CWS leadership was motivated to implement R3, the supervisors and agencies themselves were highly variable in their willingness to adopt the strategy. Indeed, during the workforce training and throughout the consultation process, many supervisors expressed feeling that R3 did not allow them the necessary time to be critical of their caseworker staff, provide negative feedback, and “vent frustrations” about the families with whom they work. Future implementations should pre-teach the notion of providing corrective feedback within a positively reinforcing culture in order to promote greater behavior change.

Conclusions

This pilot illustrated the feasibility of implementing R3 and the associated fidelity monitoring system throughout a CWS workforce. Future work will examine the potential for R3 to achieve the goal of helping systems meet the federal mandate of decreasing the time to child and family permanency, safety, and well-being. The opportunity to assess these larger implementation outcomes is imminent. Based on the outcomes of this pilot, a different state has requested the use of R3 to address their lowest performing regions in the state. This implementation began in the fall of 2015, and will reach a workforce carrying a caseload of 12,144 children. Driven by the findings from the NYC pilot, this new statewide initiative includes hypotheses related to the potential for R3 to influence organizational variables such as culture, climate, and leadership. If successful, the R3 model and supervisor implementation approach might serve as a framework for addressing large-scale implementation challenges to achieve outcomes for systems working with highly vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the New York City Administration for Children's Services and the NYC supervisors and caseworkers for their collaboration in creating this model. We would also like to thank Courtenay Padgett for her project direction and Katie Lewis for her editorial assistance. This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P50 DA035763; R01 DA 032634; and 1R01DA040416-01A1) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH097748).

References

- Aarons GA, Horowitz JD, Dlugosz LR, Ehrhart MG. The role of organizational processes in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. Oxford University Press; New York: 2012. pp. 128–153. [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(1):4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997, Pub. L. No. 105-89, 111, Stat. 2115 (1997)

- Altman JC. Engaging families in child welfare services: Worker versus client perspectives. Child Welfare. 2008;87(3):41–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Vicarious and self-reinforcement processes. In: Glaser R, editor. The nature of reinforcement. Academic Press; New York: 1971. pp. 228–278. [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond TG, Fox CM. Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Reid JB, Landsverk J. Cascading implementation of a foster and kinship parent intervention. Child Welfare. 2008;87(5):27–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornerstones For Kids . The human services workforce initiative: Relationship between staff turnover, child welfare system functioning and recurrent child abuse. Cornerstones For Kids; Houston, TX: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Falander CA, Shafranske EP. Clinical supervision. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, Gewirtz AH. Looking forward: The promise of widespread implementation of parent training programs. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8:682–694. doi: 10.1177/1745691613503478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institutes of Medicine . New directions in child abuse and neglect research. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Pears KC, Fisher PA. Competence in early development. In: Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder J, editors. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM. Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. Journal of Applied Measurement. 2002;3:85–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM. WINSTEPS Rasch measurement computer program [Computer software and manual] Beaverton, OR: 2015. Winsteps.com. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Ryan JP, Choi S, Testa MF. Integrated services for families with multiple problems: Obstacles to family reunification. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28:1074–1087. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor BP. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer's MAP test. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2000;32:396–402. doi: 10.3758/bf03200807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. A social learning approach. IV. Antisocial boys. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Treat TA, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity in psychotherapy research: Analysis of the studies and examination of the associated factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:829–841. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JM, Chamberlain P, Landsverk J, Reid J, Leve LD, Laurent H. Effects of a foster parent training intervention on placement changes of children in foster care. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:64–75. doi: 10.1177/1077559507310612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey E, Walker HM, Shinn M, O'Neill RE, Stieber S. Parent management practices and school adjustment. School Psychology Review. 1989;18:513–525. [Google Scholar]

- Rasch G. Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. The Danish Institute of Educational Research; Copenhagen: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP. Bifactor models and rotations: Exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2010;92:544–559. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.496477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP. The rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2012;47:667–696. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2012.715555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Chapman JE, Garland AF. Capturing fidelity in dissemination and implementation science. In: Beidas RS, Kendall PC, editors. Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices in child and adolescent mental health. Oxford University Press; New York: 2014. pp. 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Sheidow AJ, Chapman JE. Clinical supervision in treatment transport: Effects on adherence and outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:410–421. doi: 10.1037/a0013788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker RE, Smith EV., Jr. Reliability: A Rasch perspective. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2007;67:394–409. [Google Scholar]

- Shim M. Factors influencing child welfare employee's turnover: Focusing on organizational culture and climate. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:847–856. [Google Scholar]

- Smith EV., Jr. Detecting and evaluating the impact of multidimensionality using item fit statistics and principal component analysis of residuals. Journal of Applied Measurement. 2002;3:205–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Child welfare outcomes 2009–2012: Report to Congress. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wright BD, Masters GN. Rating scale analysis. Institute for Objective Measurement; Chicago: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wright BD, Mok M. Rasch models overview. Journal of Applied Measurement. 2000;1:83–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]