Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to (1) evaluate the effects of maxillary second and third molar eruption status on the distalization of first molars with a modified palatal anchorage plate (MPAP), and (2) compare the results to the outcomes of the use of a pendulum and that of a headgear using three-dimensional finite element analysis.

Methods

Three eruption stages were established: an erupting second molar at the cervical one-third of the first molar root (Stage 1), a fully erupted second molar (Stage 2), and an erupting third molar at the cervical one-third of the second molar root (Stage 3). Retraction forces were applied via three anchorage appliance models: an MPAP with bracket and archwire, a bone-anchored pendulum appliance, and cervical-pull headgear.

Results

An MPAP showed greater root movement of the first molar than crown movement, and this was more noticeable in Stages 2 and 3. With the other devices, the first molar showed distal tipping. Transversely, the first molar had mesial-out rotation with headgear and mesial-in rotation with the other devices. Vertically, the first molar was intruded with an MPAP, and extruded with the other appliances.

Conclusions

The second molar eruption stage had an effect on molar distalization, but the third molar follicle had no effect. The application of an MPAP may be an effective treatment option for maxillary molar distalization.

Keywords: Distalizing, Headgear, Class II, Palatal plate

INTRODUCTION

Distalization of the maxillary molars is an important treatment modality for patients with Class II malocclusion, but several concerns have been raised regarding the eruption of the second and third molars during or after distalization.1,2,3

Although headgear is effective in distalization, it is unesthetic and depends on patient cooperation.4,5 A pendulum appliance is an intraoral device placed in non-compliant patients, but it has drawbacks including distal tipping of the molars and loss of anterior anchorage.6,7,8,9,10 To overcome the loss of anterior anchorage, a bone-anchored pendulum appliance has been introduced, but there is still an issue with distal tipping of the molars.10,11,12

Recently, skeletal anchorage devices have been applied to achieve molar distalization and en masse retraction with decreased side effects and decreased dependence on patient cooperation.13,14,15,16,17 A modified palatal anchorage plate (MPAP) was effective in molar distalization in adults and adolescents with minimal distal tipping.18,19 Yu et al.20 showed advantageous treatment effects with a palatal plate compared with buccal mini-implants in a finite element (FE) study of maxillary distalization.

Several studies reported that the position of the second molar had a limited effect, if any, on the distalization of the first molars with a pendulum appliance.6,8,9,21 Recently, Flores-Mir et al.22 reported the minimal effects of the maxillary second and third molar eruption stages on molar distalization. However, their conclusion was based on low-level evidence.

Meanwhile, Kinzinger et al.2 clinically demonstrated that when the second molar had erupted, there was a greater loss of anchorage with maxillary distalization via a conventional pendulum appliance. They also provided a mathematical explanation of their results. However, no study has been conducted to explain the effects of eruption stages on molar distalization with temporary anchorage devices.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of maxillary second and third molar eruption stage on the distalization of the first molars with an MPAP and to compare the results to the outcomes of a pendulum and headgear using a three-dimensional (3D) FE analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Creation of the finite element model

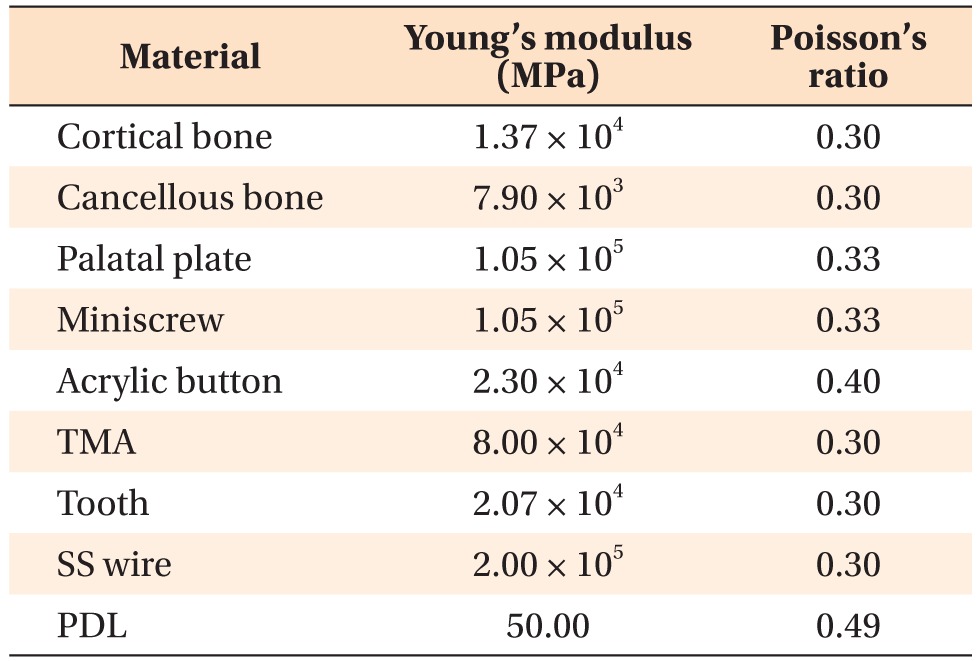

A FE model was created from computed tomography (CT) images of a dry skull of an adolescent (slice thickness, 1 mm). MIMICS version 15.01 (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) was applied to extract a 3D model from the CT images. The model was imported into Visual-Mesh version 7.0 software (ESI Group, Paris, France) to produce a tetrahedral FE mesh; the maxilla including the teeth and alveolar bone was meshed into 1-mm tetrahedrons, and the rest of the skull excluding the maxilla was meshed into 5-mm tetrahedrons. The teeth, alveolar bone, and periodontal ligament (PDL) were considered homogenous and isotropic. A small sliding condition and the Lagrange multiplier method were used to define the contact interface. The contacts between the teeth were assumed to be frictionless. The thickness of the PDL was considered to be 0.2 mm. The thickness of the cortical bone was determined according to Farnsworth et al.23 The mechanical properties of the bone, teeth, miniscrews, stainless steel (SS) wire, and PDL in the model are shown in Table 1.24,25

Table 1. Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio for various materials.

TMA, Titanium molybdenum alloy; SS, stainless steel; PDL, periodontal ligament.

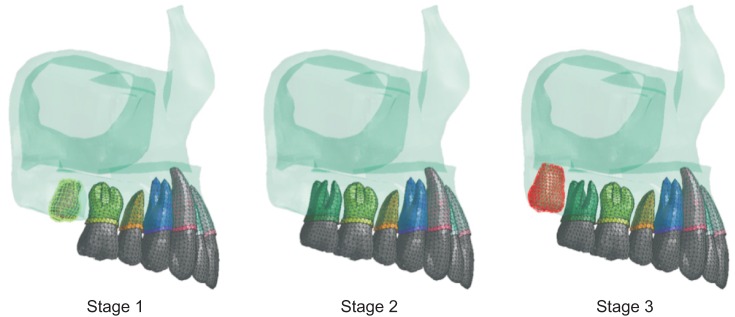

The maxillary molar eruption stages were determined according to previous studies, and defined as follows.2,26 Stage 1: the second molars follicles are placed directly toward the cervical one-third of the first molar root; Stage 2: the second molars are completely erupted; and Stage 3: the third molar follicles are placed directly toward the cervical one-third of the second molar root (Figure 1). For molars in the dental follicle, it was assumed that one-half of the root was formed, and cusps were at the height of the alveolar crest and parallel to the adjacent teeth. The material properties of the elements of the dental follicle surrounding the unerupted molar were similar to those of the PDL.

Figure 1. The finite element model eruption stages. Stage 1, an erupting second molar at the cervical one-third of the first molar root; Stage 2, a fully erupted second molar without the third molar; and Stage 3, an erupting third molar at the cervical one-third of the second molar root.

3D coordinate system and boundary conditions

The 3D coordinates were based on the occlusal plane: X (anteroposterior plane), Y (transverse plane), and Z (vertical plane). Positive values for X, Y, and Z indicated forward, left, and upward displacement. Boundary conditions were set to fixate the circumaxillary sutures in all directions.

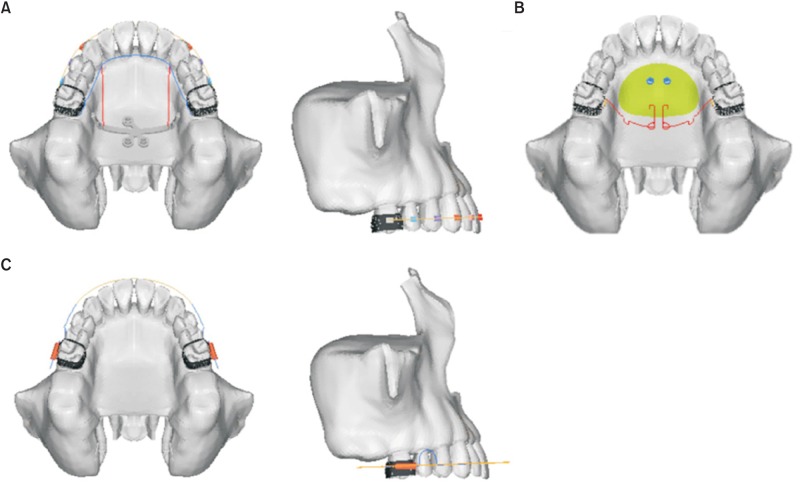

Appliance design (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Designs of the appliances. A, Modified palatal anchorage plate with brackets and orthodontic arch wire; B, bone-anchored pendulum appliance; and C, cervical-pull headgear.

Modified palatal anchorage plate

An MPAP (Jeil Medical, Seoul, Korea) was fixed in the paramedian palatal region at the sagittal level of the center of the first molar by three miniscrews (length, 8 mm; diameter, 2 mm; Jeil Medical). An SS palatal bar 1.0 mm in diameter was connected to the bands of the maxillary first molars, extending anteriorly along the lingual gingival margin of the maxillary teeth. A Roth 0.022-inches (in) bracket system (Tomy, Tokyo, Japan) was attached to the teeth and a 0.019 × 0.025-in SS archwire was tied through frictionless translational joints.

Distalization forces of 150 g were applied by connecting the most apical notch of the palatal plate to the hooks of the palatal bar located near the center of the lingual gingival margin of the canines with no elevation from the palatal bar.

Bone-anchored pendulum

An acrylic button was fixed in the anterior palate with two miniscrews. The pendulum springs were made of titanium molybdenum alloy (TMA) wires and attached to the acrylic button. To avoid a multi-stage analysis, the spring wire was pre-calibrated to determine the amount of rotation that is produced by 150-g with a given shape and length. Then, the initial deformation and rotation were assigned in the software, and calculations of stress and displacement were performed.

Cervical-pull headgear

The facebow consisted of an SS wire 1.1 mm in diameter. On each side, a 150-g distalization force was applied from the buccal tube of the maxillary first molar band at 15° inferior to the occlusal plane.

Analysis

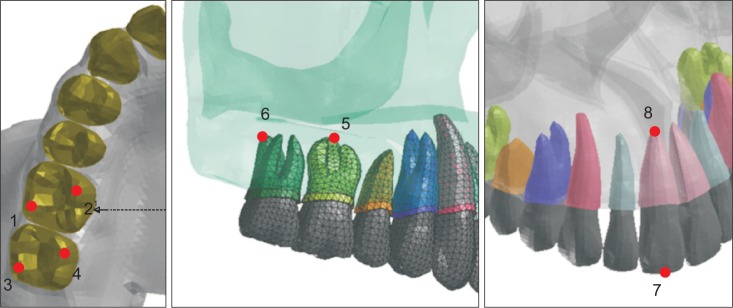

A non-linear static analysis was performed via PAM-MEDYSA V2011 and Visual-Viewer 7.0 (ESI Group). Figure 3 shows the landmarks.

Figure 3. Landmarks. 1, Distobuccal cusp of the first molar; 2, mesiolingual cusp of the first molar; 3, distobuccal cusp of the second molar; 4, mesiolingual cusp of the second molar; 5, palatal root apex of the first molar; 6, palatal root apex of the second molar; 7, midpoint of the incisal edge of the central incisor; and 8, root apex of the central incisor.

RESULTS

Displacement

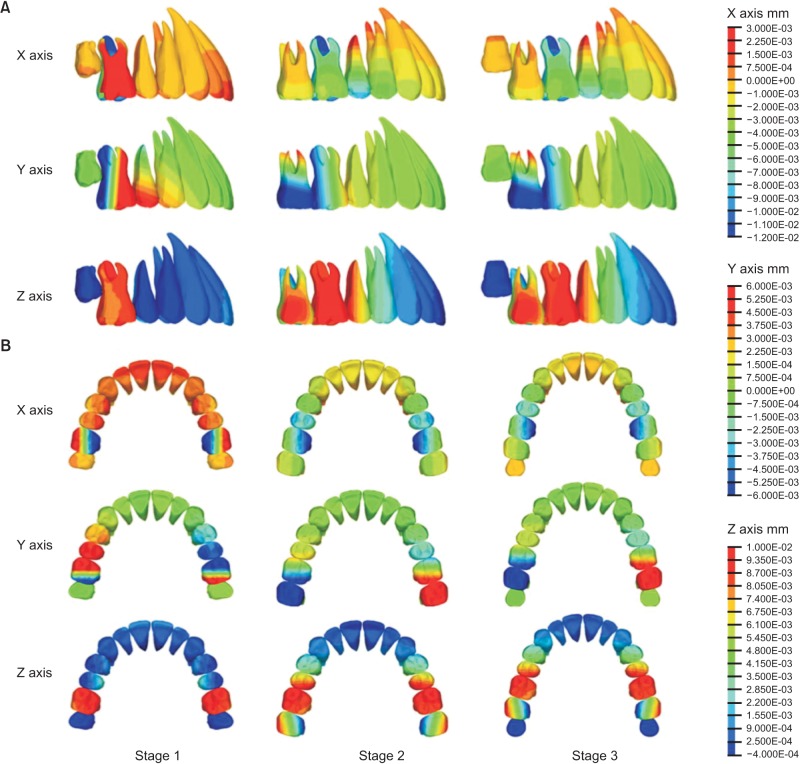

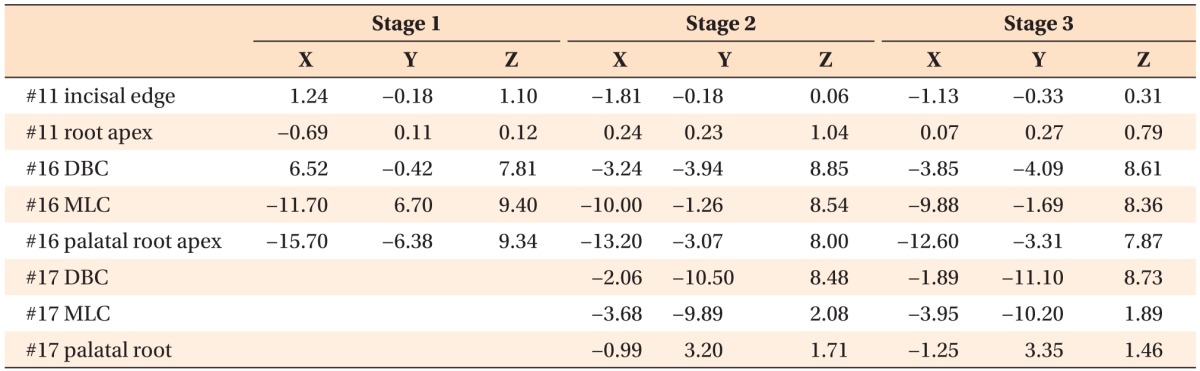

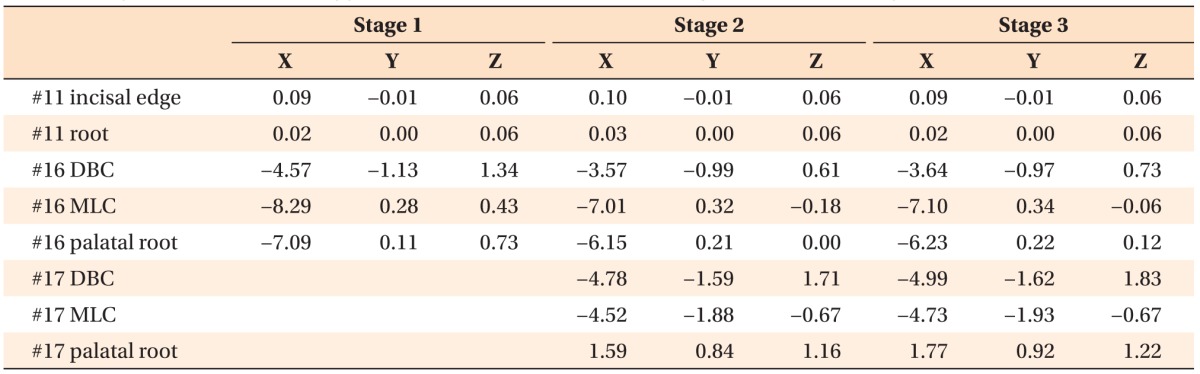

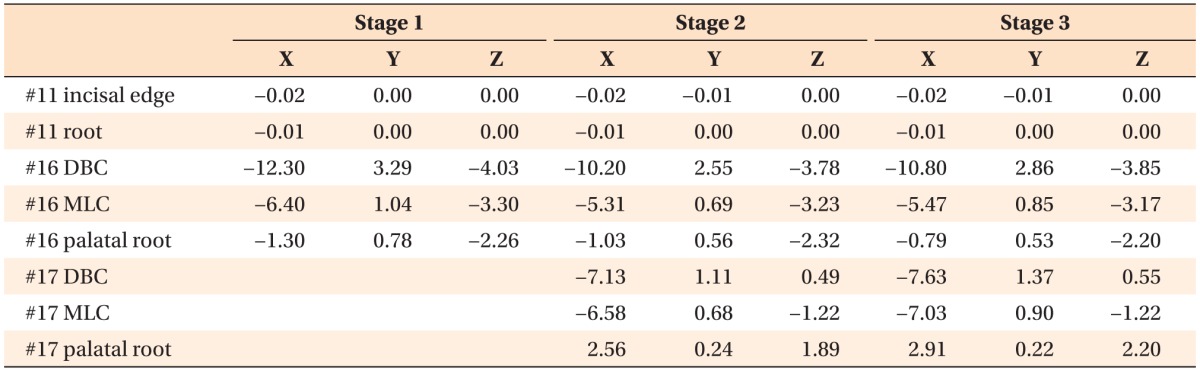

Modified palatal anchorage plate (Figure 4, Tables 2, 3, 4)

Figure 4. Contour images of tooth displacement from the modified palatal anchorage plate appliance. A, Buccal view; B, occlusal view. Positive values mean forward, left, and upward directions.

Table 2. Displacement after the application of distalization forces using a modified palatal anchorage plate (units, µm).

DBC, Distobuccal cusp; MLC, mesiolingual cusp; X, anteroposterior axis; Y, transverse axis; Z, vertical axis.

Positive values indicate forward, inward, and upward displacements.

Table 3. Displacement after the application of distalization forces using a bone-anchored pendulum (units, µm).

DBC, Distobuccal cusp; MLC, mesiolingual cusp; X, anteroposterior axis; Y, transverse axis; Z, vertical axis.

Positive values indicate forward, inward, and upward displacements.

Table 4. Displacement after the application of distalization forces using a cervical-pull headgear (units, µm).

DBC, Distobuccal cusp; MLC, mesiolingual cusp; X, anteroposterior axis; Y, transverse axis; and Z, vertical axis.

Positive values indicate forward, inward, and upward displacements.

In Stage 1, the first molar showed distalization with more movement at the root than at the crown. This was accompanied by intrusion and mesial-in rotation. The central incisor demonstrated slight amounts of flaring and intrusion.

In Stages 2 and 3, the mesial-in rotation of the first molar was less than in Stage 1, and the slight flaring of the central incisor became lingual tipping. The second molar demonstrated distalization, distal tipping, buccal tipping, and intrusion.

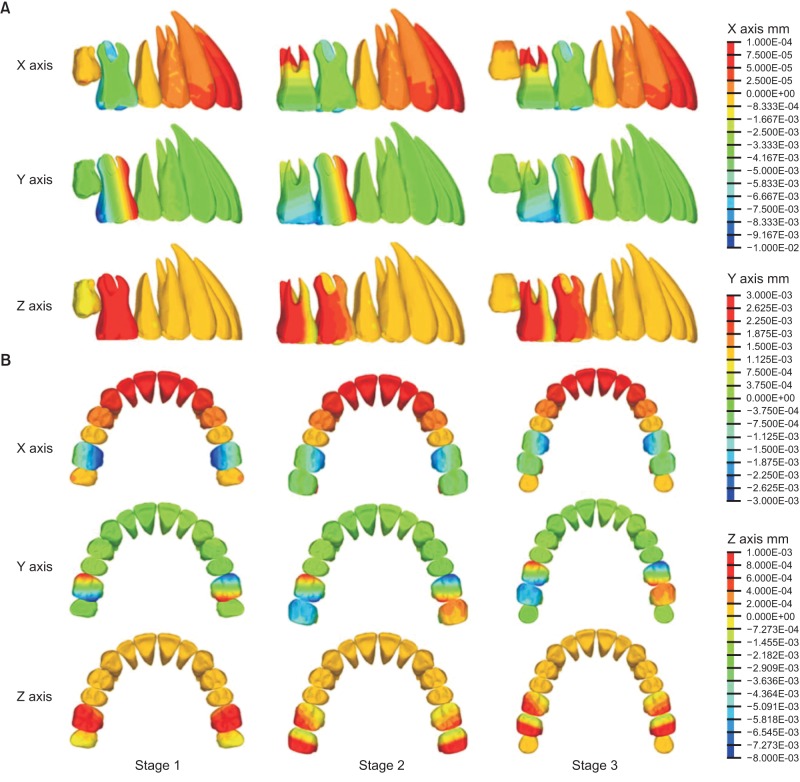

Bone-anchored pendulum appliance (Figure 5, Tables 2, 3, 4)

Figure 5. Contour images of tooth displacement from the bone-anchored pendulum appliance. A, Buccal view; B, occlusal view. Positive values mean forward, left, and upward directions.

In Stage 1, the first molar showed distalization and a slight amount of distal tipping. This was accompanied by intrusion, buccal tipping, and mesial-in rotation. The central incisor demonstrated a slight amount of flaring and intrusion.

In Stages 2 and 3, there was no noticeable change in the displacement patterns of the central incisor from Stage 1. However, the first molar showed slight extrusion of the mesiolingual cusp. The second molar demonstrated uncontrolled distal and buccal tipping and extrusion of the mesiolingual cusp.

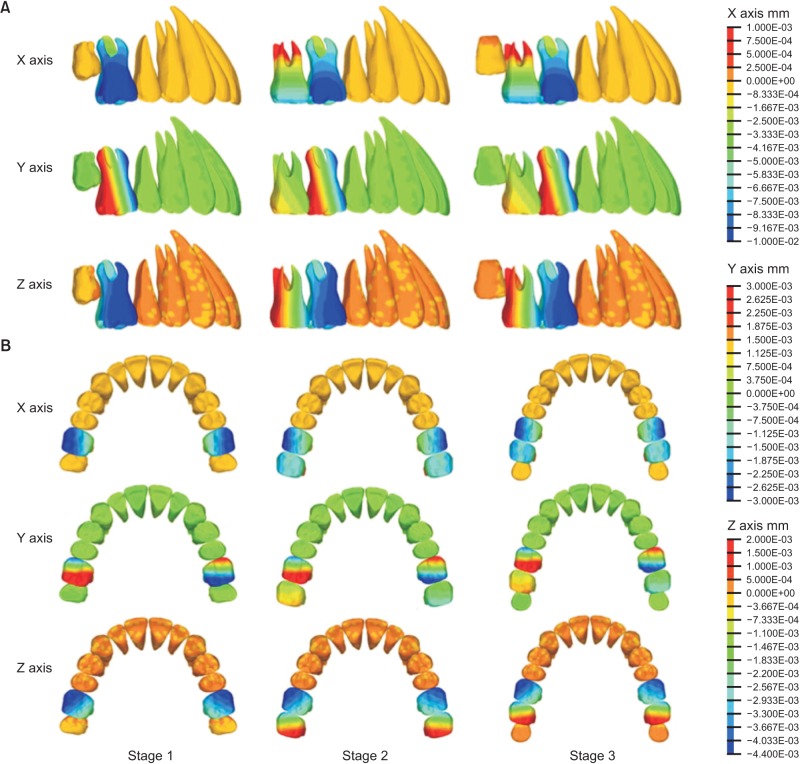

Cervical-pull headgear (Figure 6, Tables 2, 3, 4)

Figure 6. Contour images of tooth displacement from the cervical-pull headgear. A, Buccal view; B, occlusal view. Positive values mean forward, left, and upward directions.

In Stage 1, the first molar showed distalization and a large amount of distal tipping. This was accompanied by extrusion and distal-in rotation. The central incisor demonstrated no effect.

In Stages 2 and 3, there was no noticeable change in the first molar displacement patterns from Stage 1. The second molar showed uncontrolled distal tipping, extrusion, and buccal tipping.

Stress distribution

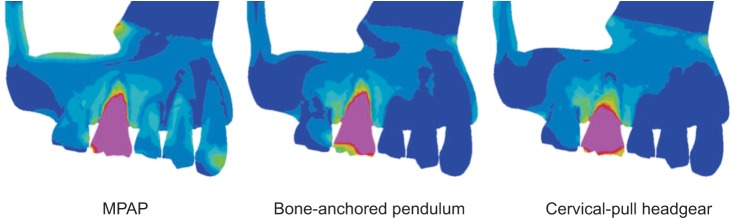

The von Mises stress distribution showed concentrations of stress around the mini-screws of the MPAP and the bone-anchored pendulum appliances, and around the bands of the first molar of the headgear appliance.

Figure 7 demonstrates longitudinal sections of alveolar bone from Stage 2 models, illustrating the differences in stress distributions depending on the appliance. The headgear had lower stresses in the apical third of the first molar root than those of the MPAP and bone-anchored pendulum. In addition, the anterior wall of the maxilla showed slight stresses with the MPAP and pendulum. All teeth demonstrated slight stresses when the MPAP was applied, especially at the central incisor.

Figure 7. The von Mises stress distribution after the application of distalization forces using an modified palatal anchorage plate (MPAP), bone-anchored pendulum, and headgear appliances during Stage 2 eruption.

DISCUSSION

Currently, there is a trend towards non-extraction treatment in patients with Class II malocclusion. However, treatment timing is still controversial; therefore, our study aimed to evaluate the effects of maxillary second and third molar eruption status on distalization of the first molars.

For all devices in our study, there was no difference between Stages 2 and 3 regarding the displacement tendencies of the maxillary dentition. For the headgear, the three stages showed similar displacement tendencies. The MPAP appliance showed greater distalization of the first molar root than that of the crown in all growth stages. This might be because the direction of force passes apical to the center of resistance of the maxillary dentition.27,28

Recently, a study reported that the displacement of the entire arch might be dictated by a direct relationship between the center of resistance of the whole arch, the point of force application, and its vector.29 The MPAP appliance exhibited mesial-in rotation of the first molars because the force was applied from the palatal side. However, this rotation of the first molars was less in Stages 2 and 3 because the center of resistance was positioned more posteriorly. Therefore, when more root movement of the first molar is required, it might be recommended to use an MPAP, regardless of the eruption stages of the maxillary second and third molars.

In addition, in Stage 1, the central incisor presented a slight amount of anterior displacement. This might be due to deformation in the shape of the maxilla under reciprocal forces transferred to the palate through the MPAP plate and its miniscrews. Moreover, clinical studies on the treatment effects of the MPAP showed no such displacement.18,19 Meanwhile, in Stages 2 and 3, the central incisor presented lingual movement.

A previous study reported that the distal tipping of the first molar after distalization using different devices supported by skeletal anchorage ranged between 0.8° and 12.2°.30 In agreement, the bone-anchored pendulum appliance showed first molar distalization and a small amount of distal tipping accompanied by intrusion, mesial-in rotation, and buccal tipping in Stage 1. In Stages 2 and 3, the intrusion component of the force decreased and buccal tipping increased, resulting in extrusion of the mesiolingual cusp. However, this extrusion was small in magnitude and clinically negligible. In addition, the second molars showed uncontrolled distal tipping.

The displacements can be explained by the rotational nature of the force applied by the TMA spring wire and the relationship between its point of application and the position of the center of resistance of the multi-rooted teeth, which is suggested to be located somewhere between the furcation area and 1–2 mm cervical to the root apex.31

Contrary to previous studies, the bone-anchored pendulum presented a slight amount of anterior displacement of the central incisor.10,11,12 This was previously reported in a clinical study on maxillary molar distalization using skeletal anchorage.32 This might be due to deformation in the shape of the maxilla.

With cervical-pull headgear, the first molar showed distalization and a large amount of distal tipping in which the crown was displaced by about 9.5 times the amount of root displacement. In agreement with Oosthuizen et al.,33 the headgear results also showed mesial-out rotation and extrusion of the first molar. In Stages 2 and 3, the second molar showed uncontrolled distal tipping combined with extrusion. In addition, Reimann et al.34 evaluated the effects of headgear on molar distalization with and without second and third molars. They showed that the displacement of the first molar was twice that of the second molar without the presence of the third molar; and it was 10% greater when both the second and third molars were absent. In our study, the sagittal displacement of the distobuccal cusp of the second molar was 70% of that of the first molar. Meanwhile, the displacement of the distobuccal cusp of the first molar with an unerupted second molar was 20% greater than that when the second molar was erupted. Unfortunately, the angulation and rotation of the molars were not evaluated in the study by Reimann et al.34

The von Mises stress distribution showed lower stress in the apical third of the first molar root with the headgear than with the MPAP or bone-anchored pendulum. This was in agreement with the distal tipping movement that occurred with headgear application, and the bodily movement and decreased tipping with the other appliances. The relationship between the force vector of each appliance and the center of resistance might be the main reason for the different displacement patterns. Moreover, the slight stresses on the anterior wall of the maxilla with the MPAP and bone-anchored pendulum suggest minor deformation of the maxilla under their reaction forces (Figure 7).

Our results suggest that the most efficient treatment timing when using an MPAP is after the full eruption of the second molar, since this decreases the mesial-in rotation of the first molar. On the other hand, it is more efficient to use a bone-anchored pendulum appliance before the eruption of the second molar because distalization after its eruption results in extrusion of the first molar and increases its buccal tipping. In addition, the presence or absence of the third molar tooth follicle demonstrated a minimal or no effect on tooth movement with any of the appliances. However, the FE analysis is useful only for the assessment of the initial force system. This might be a key element behind the differences between our results and those of Kinzinger et al.2 Hence, the extension of the interpretation of our results into a clinical situation should be approached with caution.

In our study, the fixed orthodontic appliance was placed on the teeth with the MPAP, since it was introduced in previous studies as a whole treatment entity.18,19,35,36,37 Meanwhile, the headgear and the pendulum were applied without braces, because although several authors placed headgear and brackets simultaneously,38,39 others placed the braces after the end of that headgear phase.40,41,42 Moreover, several authors applied pendulums separately, and then followed with fixed orthodontic appliances.43,44,45 Hence, the treatment techniques of headgear and a pendulum without braces were selected for comparisons with an MPAP in our study. Future studies to evaluate different headgear and pendulum techniques are recommended.

In this study, the results may differ from the biological response in patients. Moreover, the effect of time was not factored in; thus, clinical outcomes may be different from these results. Therefore, clinical evaluations of these results are warranted to overcome the FE limitation regarding the time effect and anatomical variability.

CONCLUSION

The presence or absence of a third molar tooth follicle showed no significant effect on first molar movement, regardless of the appliance.

In Stage 1, MPAP resulted in distalization of the first molar, but more at the root than at the crown. The bone-anchored pendulum resulted in distalization, distal and buccal tipping, and intrusion. When the bone-anchored pendulum appliance was used in Stage 2, extrusion and increased buccal tipping of the first molar resulted.

The application of an MPAP may be an effective treatment option for maxillary molar distalization.

Footnotes

This study was partly supported by funds from the Department of Dentistry and Graduate School of Clinical Dental Science, The Catholic University of Korea.

The authors report no commercial, proprietary, or financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

References

- 1.Gianelly AA. Distal movement of the maxillary molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114:66–72. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinzinger GS, Fritz UB, Sander FG, Diedrich PR. Efficiency of a pendulum appliance for molar distalization related to second and third molar eruption stage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;125:8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlsson I, Bondemark L. Intraoral maxillary molar distalization. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:923–929. doi: 10.2319/110805-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egolf RJ, BeGole EA, Upshaw HS. Factors associated with orthodontic patient compliance with intraoral elastic and headgear wear. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;97:336–348. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(90)70106-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lima Filho RM, Lima AL, de Oliveira Ruellas AC. Longitudinal study of anteroposterior and vertical maxillary changes in skeletal class II patients treated with Kloehn cervical headgear. Angle Orthod. 2003;73:187–193. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2003)73<187:LSOAAV>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh J, Nanda RS. Evaluation of an intraoral maxillary molar distalization technique. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;110:639–646. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)80041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byloff FK, Darendeliler MA. Distal molar movement using the pendulum appliance. Part 1: Clinical and radiological evaluation. Angle Orthod. 1997;67:249–260. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1997)067<0249:DMMUTP>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byloff FK, Darendeliler MA, Clar E, Darendeliler A. Distal molar movement using the pendulum appliance. Part 2: The effects of maxillary molar root uprighting bends. Angle Orthod. 1997;67:261–270. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1997)067<0261:DMMUTP>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bussick TJ, McNamara JA., Jr Dentoalveolar and skeletal changes associated with the pendulum appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;1(17):333–343. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(00)70238-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polat-Ozsoy O, Kircelli BH, Arman-Ozçirpici A, Pektaş ZO, Uçkan S. Pendulum appliances with 2 anchorage designs: conventional anchorage vs bone anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:339.e9–339.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byloff FK, Kärcher H, Clar E, Stoff F. An implant to eliminate anchorage loss during molar distalization: a case report involving the Graz implant-supported pendulum. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2000;15:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kircelli BH, Pektaş ZO, Kircelli C. Maxillary molar distalization with a bone-anchored pendulum appliance. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:650–659. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0650:MMDWAB]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papadopoulos MA. Orthodontic treatment of Class II malocclusion with miniscrew implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:604.e1–604.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.03.013. discussion 604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinzinger GS, Gülden N, Yildizhan F, Diedrich PR. Efficiency of a skeletonized distal jet appliance supported by miniscrew anchorage for noncompliance maxillary molar distalization. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaya B, Sar C, Arman-Özçirpici A, Polat-Özsoy O. Palatal implant versus zygoma plate anchorage for distalization of maxillary posterior teeth. Eur J Orthod. 2013;35:507–514. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjs059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Miyazawa K, Tabuchi M, Sato T, Kawaguchi M, Goto S. Effectiveness of en-masse retraction using midpalatal miniscrews and a modified transpalatal arch: treatment duration and dentoskeletal changes. Korean J Orthod. 2014;44:88–95. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2014.44.2.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimura M, Sannohe M, Nagasaka H, Igarashi K, Sugawara J. Nonextraction treatment with temporary skeletal anchorage devices to correct a Class II Division 2 malocclusion with excessive gingival display. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kook YA, Bayome M, Trang VT, Kim HJ, Park JH, Kim KB, et al. Treatment effects of a modified palatal anchorage plate for distalization evaluated with cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;146:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sa'aed NL, Park CO, Bayome M, Park JH, Kim Y, Kook YA. Skeletal and dental effects of molar distalization using a modified palatal anchorage plate in adolescents. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:657–664. doi: 10.2319/060114-392.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu IJ, Kook YA, Sung SJ, Lee KJ, Chun YS, Mo SS. Comparison of tooth displacement between buccal mini-implants and palatal plate anchorage for molar distalization: a finite element study. Eur J Orthod. 2014;36:394–402. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjr130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joseph AA, Butchart CJ. An evaluation of the pendulum distalizing appliance. Semin Orthod. 2000;6:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flores-Mir C, McGrath L, Heo G, Major PW. Efficiency of molar distalization associated with second and third molar eruption stage. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:735–742. doi: 10.2319/081612-658.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farnsworth D, Rossouw PE, Ceen RF, Buschang PH. Cortical bone thickness at common miniscrew implant placement sites. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanne K, Hiraga J, Kakiuchi K, Yamagata Y, Sakuda M. Biomechanical effect of anteriorly directed extraoral forces on the craniofacial complex: a study using the finite element method. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;95:200–207. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu HS, Baik HS, Sung SJ, Kim KD, Cho YS. Three-dimensional finite-element analysis of maxillary protraction with and without rapid palatal expansion. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:118–125. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjl057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarrafpour B, Swain M, Li Q, Zoellner H. Tooth eruption results from bone remodelling driven by bite forces sensed by soft tissue dental follicles: a finite element analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teuscher U. An appraisal of growth and reaction to extraoral anchorage. Simulation of orthodontic-orthopedic results. Am J Orthod. 1986;89:113–121. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(86)90087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeong GM, Sung SJ, Lee KJ, Chun YS, Mo SS. Finite-element investigation of the center of resistance of the maxillary dentition. Korean J Orthod. 2009;39:83–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sung EH, Kim SJ, Chun YS, Park YC, Yu HS, Lee KJ. Distalization pattern of whole maxillary dentition according to force application points. Korean J Orthod. 2015;45:20–28. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2015.45.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fudalej P, Antoszewska J. Are orthodontic distalizers reinforced with the temporary skeletal anchorage devices effective? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith RJ, Burstone CJ. Mechanics of tooth movement. Am J Orthod. 1984;85:294–307. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(84)90187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelgör IE, Büyükyilmaz T, Karaman AI, Dolanmaz D, Kalayci A. Intraosseous screw-supported upper molar distalization. Angle Orthod. 2004;74:838–850. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2004)074<0838:ISUMD>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oosthuizen L, Dijkman JF, Evans WG. A mechanical appraisal of the Kloehn extraoral assembly. Angle Orthod. 1973;43:221–232. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1973)043<0221:AMAOTK>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reimann S, Keilig L, Jäger A, Brosh T, Shpinko Y, Vardimon AD, et al. Numerical and clinical study of the biomechanical behaviour of teeth under orthodontic loading using a headgear appliance. Med Eng Phys. 2009;31:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kook YA, Park JH, Bayome M. Space regaining with modified palatal anchorage plates. J Clin Orthod. 2015;49:587–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kook YA, Park JH, Kim Y, Ahn CS, Bayome M. Sagittal correction of adolescent patients with modified palatal anchorage plate appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015;148:674–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kook YA, Park JH, Bayome M, Sa'aed NL. Correction of severe bimaxillary protrusion with first premolar extractions and total arch distalization with palatal anchorage plates. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015;148:310–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baccetti T, Franchi L, Stahl F. Comparison of 2 comprehensive Class II treatment protocols including the bonded Herbst and headgear appliances: a double-blind study of consecutively treated patients at puberty. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135:698.e1–698.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.03.015. discussion 698-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shpack N, Brosh T, Mazor Y, Shapinko Y, Davidovitch M, Sarig R, et al. Long- and short-term effects of headgear traction with and without the maxillary second molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;146:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lima Filho RM, de Oliveira Ruellas AC. Long-term maxillary changes in patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion treated with slow and rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varlik SK, Iscan HN. The effects of cervical headgear with an expanded inner bow in the permanent dentition. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:425–430. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freitas MR, Lima DV, Freitas KM, Janson G, Henriques JF. Cephalometric evaluation of Class II malocclusion treatment with cervical headgear and mandibular fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:477–482. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caprioglio A, Cafagna A, Fontana M, Cozzani M. Comparative evaluation of molar distalization therapy using pendulum and distal screw appliances. Korean J Orthod. 2015;45:171–179. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2015.45.4.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angelieri F, de Almeida RR, Janson G, Castanha Henriques JF, Pinzan A. Comparison of the effects produced by headgear and pendulum appliances followed by fixed orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:572–579. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel MP, Henriques JF, de Almeida RR, Pinzan A, Janson G, de Freitas MR. Comparative cephalometric study of Class II malocclusion treatment with Pendulum and Jones jig appliances followed by fixed corrective orthodontics. Dental Press J Orthod. 2013;18:58–64. doi: 10.1590/s2176-94512013000600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]