Abstract

Background

Little evidence supports the use of any one vas occlusion method. Data from a number of studies now suggest that there are differences in effectiveness among different occlusion methods. The main objectives of this study were to estimate the effectiveness of vasectomy by cautery and to describe the trends in sperm counts after cautery vasectomy. Other objectives were to estimate time and number of ejaculations to success and to determine the predictive value of success at 12 weeks for final status at 24 weeks.

Methods

A prospective, non-comparative observational study was conducted between November 2001 and June 2002 at 4 centers in Brazil, Canada, the UK, and the US. Four hundred men who chose vasectomy were enrolled and followed for 6 months. Sites used their usual cautery vasectomy technique. Earlier and more frequent than normal semen analyses (2, 5, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks after vasectomy) were performed. Planned outcomes included effectiveness (early failure based on semen analysis), trends in sperm counts, time and number of ejaculations to success, predictive value of success at 12 weeks for the outcome at 24 weeks, and safety evaluation.

Results

A total of 364 (91%) participants completed follow-up. The overall failure rate based on semen analysis was 0.8% (95% confidence interval 0.2, 2.3). By 12 weeks 96.4% of participants showed azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia (< 100,000 sperm/mL). The predictive value of a single severely oligozoospermia sample at 12 weeks for vasectomy success at the end of the study was 99.7%. One serious unrelated adverse event and no pregnancies were reported.

Conclusion

Cautery is a very effective method for occluding the vas. Failure based on semen analysis is rare. In settings where semen analysis is not practical, using 12 weeks as a guideline for when men can rely on their vasectomy should lessen the risk of failure compared to using a guideline of 20 ejaculations after vasectomy.

Background

In spite of the vast published literature on vasectomy, until recently there has been little evidence to support the use of any one occlusion method over others [1,2]. Data from a number of studies now suggest that there are differences in effectiveness among the different occlusion methods. For example, several recently published studies have found higher than expected failure rates for vasectomy by ligation and excision, especially when used without fascial interposition. These reports suggest that ligation and excision without fascial interposition may not be a satisfactory occlusion technique [3-8].

Some published evidence suggests that cautery may be a more effective occlusion technique than some of the other methods currently being used [1]. In addition, at the time our study was being carried out, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in the U.K. recommended the use of cautery (or ligation and excision with fascial interposition), although they noted that the evidence in favor of cautery was at the lowest level, i.e. expert opinion [9].

In the United States, cautery is the most commonly used vasectomy occlusion method [10]. However, in resource poor countries, where 75% of the world's vasectomies are done, it is much less common–ligation and excision being the most widely used occlusion technique, especially in large public-sector programs [11].

The primary objectives of this study were to: estimate the effectiveness of cautery as currently performed at four different sites practicing slightly different techniques, using standardized semen analysis methods, and to describe the trends in sperm counts after vasectomy with cautery. Secondary objectives were to: estimate the time and number of ejaculations to success among men who were vasectomized using cautery and to describe the predictive value of success at 12 weeks for the final outcome at 24 weeks.

Methods

We conducted a prospective, non-comparative observational study of vasectomy by cautery at four centers: two family planning clinics, one in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil and the other in Oxford, U.K. ; and two university hospitals, one in Québec City, Québec, Canada and the other in Seattle, WA, U.S. No new methods were introduced. The only study intervention was to obtain earlier and more frequent semen analyses than were normally performed. Enrollment began in November 2001 and all follow-up was completed by June 2002. The study was approved by institutional review boards of Family Health International and each participating center.

Four hundred men who chose vasectomy as their method of contraception were recruited for the study at the four centers (100/center). After obtaining informed consent, men were screened for eligibility. In addition to meeting local clinic requirements for vasectomy, study admission criteria included: freely consenting to participate, willing to provide semen samples according to the follow-up schedule, willing to use an alternate contraceptive until success was confirmed, agreeing to provide follow-up information such as serious adverse events and pregnancy, agreeing to maintain a record of all ejaculations occurring between follow-up visits, able to understand the study procedures and requirements, no condition which in the opinion of the principal investigator contraindicated participation, and no history of previous vasectomy.

Vasectomy procedures and follow-up

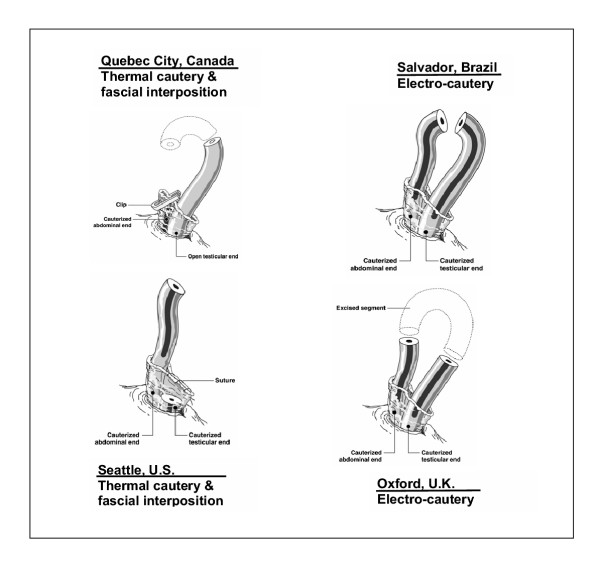

Each study site used their usual vasectomy technique. A total of 14 surgeons, all experienced with vasectomy using cautery, participated in the study (one at the U.S. site, two each at the Brazil and Canada sites, and nine at the U.K. site). As this was an observational study, no attempt was made to standardize the vasectomy techniques among sites or surgeons. Three of the sites used the no-scalpel (NSV) approach to the vas (Brazil, Canada and the U.S.) and the other site used a scalpel approach with two lateral incisions (U.K.). The occlusion techniques used varied among the sites in terms of type of cautery (thermal or electrocautery), open vs. closed ended, whether or not a portion of the vas was excised, and use of fascial interposition (Figure 1). Follow-up semen analysis was carried out at 2, 5, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24 weeks after vasectomy. Participants were asked to record all ejaculations between semen analyses on a wallet-sized card, which was turned in to study personnel at each follow-up.

Figure 1.

Occlusion techniques used at the 4 study sites. Dotted outline indicates segment of the vas excised. Darkened vas lumen indicates cauterized segment. Fascial interposition involves placing a layer of the vas sheath between the 2 cut ends of the vas to form a tissue barrier.

Semen analysis

All sites used standardized laboratory methods for determining sperm concentration of semen samples using adapted World Health Organization techniques [12]. Ejaculated semen was first examined by phase-contrast microscopy (X400) to estimate sperm concentration and then diluted with water. Sperm concentration was determined using a Neubauer hemocytometer. The laboratories conducted periodic quality control tests.

Outcome measures

Study outcomes included: effectiveness (i.e. early failure rate), trends in sperm counts, time and number of ejaculations to success, predictive value of success at 12 weeks for the outcome at 24 weeks, and safety based on serious adverse events.

The primary definition of vasectomy success was severe oligozoospermia–less than 100,000 sperm/mL in two consecutive specimens at least two weeks apart with all subsequent samples showing only rare sperm. An additional definition of vasectomy success was azoospermia–two consecutive specimens with no sperm at least two weeks apart with all subsequent samples showing only rare sperm. Early failure was defined as not meeting the definition of success during the 24 weeks of follow up and having greater than 10 million sperm /mL at week 12 or later after vasectomy. In addition, clinician declared failure–obvious failure based on large numbers of motile sperm–prior to 12 weeks was also classified as early failure.

Statistical methods

The sample size calculation was focused on the estimation of the failure rate with adequate precision based on an exact binomial 95% confidence interval. A sample size of 400 was considered sufficient to adequately estimate the failure rate assuming that the rate would not be larger than 3% and allowing for 10% lost to follow-up.

The overall failure rate was estimated based on an exact binomial 95% confidence interval. Only men who provided semen samples for at least 12 weeks or were declared a vasectomy failure by a site clinician prior to 12 weeks were included in this analysis. The sperm concentration patterns for the identified failures were examined in more detail. The sperm concentrations for all participants in the study were classified at each time point into several categories ranging from azoospermia to more than 10 million sperm per mL to study the progression towards success during the 24 weeks of follow up. Kaplan-Meier product limit estimates of the probabilities of vasectomy success at each scheduled week of follow-up through week 24 and their 95% confidence intervals were produced for severe oligozoospermia and azoospermia outcomes. Peto's standard error [13] was used to compute the 95% confidence intervals. Similar life-table analysis was conducted to study the number of ejaculations needed to achieve success instead of time.

Cox proportional hazard regressions were fitted to study the effect of age (two age groups: less than 35, and 35 and older. Further breakdown into other age groups did not provide additional useful information), site, and cumulative number of ejaculations during follow-up on time to success. Cumulative number of ejaculations was treated as a time-dependent covariate. Hazard ratios (HR) are presented in the results.

Finally, given the interest in simplifying guidelines for follow-up after vasectomy, we estimated the predictive value of a single sample showing severe oligozoospermia at 12 weeks after vasectomy for vasectomy success at the end of the 24 weeks of follow-up. Only participants who provided a semen sample at 12 weeks and completed the study were included in this analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the 400 men enrolled in the study are shown in Table 1. Median age of participants at the time of vasectomy was 36 years (range 25–62). Final disposition of study participants was as follows: out of 400, 364 (91%) completed the 24 weeks of follow-up; 19 (4.8%) discontinued early, primarily for personal reasons; and 17 (4.2%) were lost to follow-up. No pregnancies were reported during the study period and only one serious adverse event occurred, a case of measles unrelated to the vasectomy procedure.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants (N = 400; 100 per center)

| Center | |||||||||||

| Brazil | Canada | US | UK | Total | |||||||

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age group | < 30 | 20 | 20.0 | 8 | 8.0 | 9 | 9.0 | 4 | 4.0 | 41 | 10.3 |

| 30–34 | 37 | 37.0 | 36 | 36.0 | 28 | 28.0 | 16 | 16.0 | 117 | 29.3 | |

| 35–39 | 32 | 32.0 | 30 | 30.0 | 25 | 25.0 | 38 | 38.0 | 125 | 31.3 | |

| 40+ | 11 | 11.0 | 26 | 26.0 | 38 | 38.0 | 42 | 42.0 | 117 | 29.3 | |

| Married/partnered | 100 | 100.0 | 87 | 87.0 | 93 | 93.0 | 98 | 98.0 | 379 | 94.5 | |

| Number of children | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 6.0 | 6 | 6.0 | 4 | 4.0 | 16 | 4.0 |

| 1 | 5 | 5.0 | 14 | 14.0 | 18 | 18.0 | 7 | 7.0 | 44 | 11.0 | |

| 2 | 48 | 48.0 | 51 | 51.0 | 50 | 50.0 | 52 | 52.0 | 201 | 50.3 | |

| 3+ | 47 | 47.0 | 29 | 29.0 | 26 | 26.0 | 37 | 37.0 | 139 | 34.8 | |

| Prior condom use | No | 47 | 47.0 | 41 | 41.0 | 52 | 52.0 | 44 | 44.0 | 184 | 46.0 |

| Yes | 53 | 53.0 | 59 | 59.0 | 48 | 48.0 | 56 | 56.0 | 216 | 54.0 | |

Of the 400 participants enrolled, 11 did not provide any semen analysis data after vasectomy and were thus excluded from further analysis. The remaining 389 men contributed data to the analyses of trends in sperm counts and time/number of ejaculations to success. Eleven additional men had less than 12 weeks of follow-up without having been declared a failure by a study site clinician. They were excluded from the effectiveness analysis and thus data from 378 men were used for the effectiveness analysis presented here.

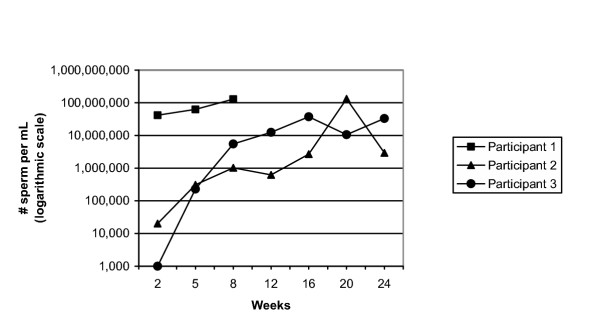

The overall failure rate was 0.8% (3/378; 95% confidence interval 0.2, 2.3). The three failures occurred at two study sites. Sperm concentration profiles for the three participants with a vasectomy failure are shown in Figure 2. One participant (Participant 1 in Figure 2) appeared to have been a technical failure, with vas occlusion not successfully carried out on one or both sides. His sperm concentration was in the normal range at the 2 week follow-up and remained high through 8 weeks after vasectomy, at which time he requested and had another vasectomy. He was discontinued from the study at that point. The other two participants (Participants 2 and 3 in Figure 2) showed semen analysis patterns consistent with very early recanalization–drops in sperm concentration to very low numbers followed by slow, steady increases to the normal range.

Figure 2.

Sperm counts for the 3 participants with vasectomy failure. The pattern for Participant 1 is consistent with technical failure, while those of Participants 2 and 3 suggest early recanalization.

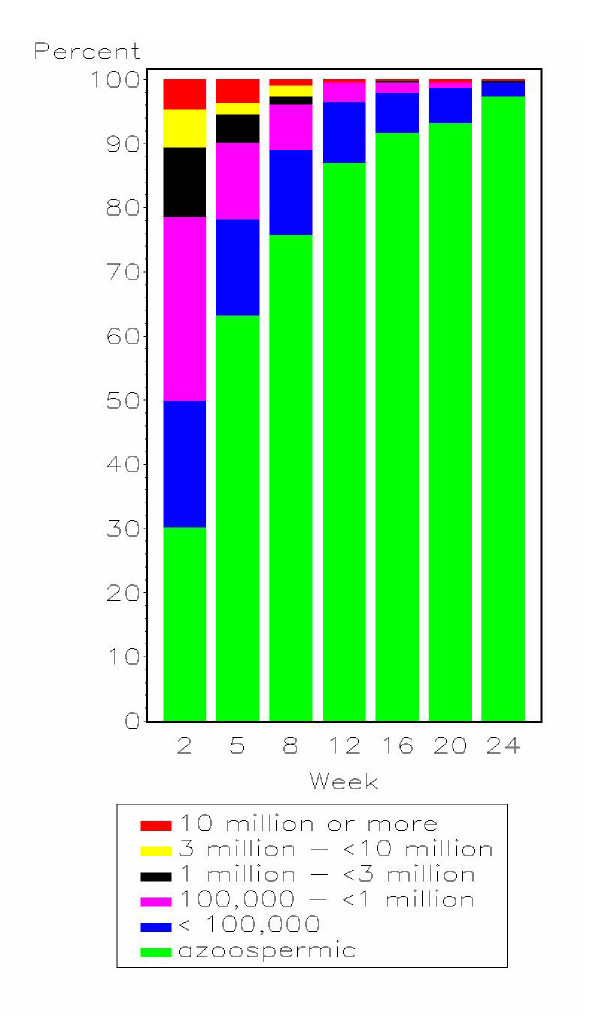

To examine trends in sperm counts over the 24 week follow-up period, semen analysis results at each time point were divided into six categories from azoospermia to 10 million or more sperm/mL (Figure 3). At the 2 week follow-up, 49.7% (190/382) of participants showed azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia, rising to 96.4% (354/367) by the 12 week half way point of the study, and eventually reaching 99.4% (361/363) by the 24 week study endpoint. This analysis considers the available data for all men at each follow-up week and, unlike the Kaplan-Meier estimates presented below, ignores the classification of each participant at previous weeks. For example, in Figure 3, a participant may be classified in a lower sperm concentration category at a particular follow-up week, and later on, be classified in a higher sperm concentration category.

Figure 3.

Sperm concentration (number sperm per mL) categories by week of follow-up (N = 389).

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative event probabilities for time to vasectomy success (defined as severe oligozoospermia and as azoospermia) are presented in Table 2. The cumulative probability for vasectomy success was essentially identical for both endpoints at 24 weeks after vasectomy. However, men reached success sooner when severe oligozoospermia was used as the definition of success compared to when azoospermia was used (e.g. at 12 weeks follow-up 95% vs. 85% success, respectively). Median time to success was within the 5 week time window for both oligozoospermia and azoospermia.

Table 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probabilities of vasectomy success (N = 389). Probabilities of success by follow up week and age (< 35 or ≥ 35 years) for success defined as oligozoospermia and azoospermia.

| Probability of success defined as oligozoospermia1 (95% CI) | Probability of success defined as azoospermia2 (95% CI) | |||||

| Follow-up week | All participants | Age < 35 years | Age ≥ 35 years | All participants | Age < 35 years | Age ≥ 35 years |

| 2 | 44.9% (39.9, 49.8) | 48.7% (40.8, 56.6) | 42.3% (36.0,48.7) | 25.8% (21.4, 30.1) | 22.7% (16.1, 29.3) | 27.8% (22.0, 33.5) |

| 5 | 74.5% (70.1, 78.9) | 77.9% (71.4, 84.5) | 72.2% (66.5, 78.0) | 58.2% (53.3, 63.1) | 61.0% (53.3, 68.7) | 56.3% (49.9, 62.7) |

| 8 | 87.7% (84.3, 91.0) | 90.0% (85.1, 95.0) | 86.1% (81.7, 90.6) | 73.6% (69.2, 78.1) | 77.6% (70.8, 84.3) | 71.0% (65.1, 76.9) |

| 12 | 94.9% (92.7, 97.1) | 97.2% (94.7, 99.6) | 93.5% (90.3, 96.7) | 85.3% (81.8, 88.9) | 91.8% (87.4, 96.3) | 81.1% (76.0, 86.2) |

| 16 | 97.1% (95.3, 98.8) | 97.9% (95.5, 100.0) | 96.5% (94.2, 98.9) | 90.2% (87.2, 93.3) | 93.9% (90.0, 97.8) | 87.9% (83.6, 96.3) |

| 20 | 98.4% (97.0, 99.8) | 99.3% (97.9, 100.0) | 97.8% (95.7, 99.9) | 94.0% (91.6, 96.5) | 95.9% (92.7, 99.1) | 92.8% (89.3, 96.3) |

| 24 | 98.4% (95.3, 100.0) | 99.3% (97.9, 100.0) | 97.8% (93.6, 100.0) | 98.0% (95.3, 100.0) | 98.2% (94.7, 100.0) | 98.1% (94.5, 100.0) |

1less than 100,000 sperm/mL in two consecutive specimens at least two weeks apart with all subsequent samples showing only rare sperm. 2two consecutive specimens with no sperm at least two weeks apart with all subsequent samples showing only rare sperm

All three covariates examined–age, site, and cumulative number of ejaculations during follow-up–had a significant effect on time to vasectomy success defined as severe oligozoospermia. Younger men were likely to reach success earlier than older men (HR = 1.29, p = 0.02, see Table 2 for success rate estimates at different time points), but cumulative success rates at the end of the study did not differ by age. In addition, compared to participants from Brazil, those from the U.S. (HR = 1.95, p < 0.0001) and the U.K. (HR = 1.41, p = 0.02) reached success significantly earlier, but those from Canada (HR = 1.21, p = 0.20) did not. The differences in the success rates by center were most apparent prior to the 12-week visit (data not shown). Finally, a higher number of cumulative ejaculations during the follow-up period played a role in accelerating occurrence of success (HR = 1.02, p = 0.007). Similar results were seen when success was defined as azoospermia (see Table 2; data on site and cumulative number of ejaculations during follow-up not shown).

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative event probabilities for number of ejaculations to vasectomy success (defined as severe oligozoospermia) reached 98.7 per 100 men (95% CI 97.4, 100.0) at 65 ejaculations. By 10 ejaculations after vasectomy, nearly 50% of men were vasectomy successes, at 20 ejaculations 77% were, and by 35 ejaculations over 90% were. The median number of ejaculations to severe oligozoospermia was 12.

The predictive value of a single semen sample showing severe oligozoospermia at 12 weeks for vasectomy success at the end of the study (using the oligozoospermia definition for success) was 99.7%. In other words, nearly all men who showed severe oligozoospermia at 12 weeks after vasectomy were vasectomy successes at the end of the 24 weeks of follow-up.

Discussion

Our results indicate that cautery is a highly effective and safe method to occlude the vas for vasectomy. Results of this prospective study found that vasectomy failure, based on semen analysis results, is rare (0.8%). In addition, no serious adverse events related to the vasectomy procedure were reported.

The published literature on cautery occlusion methods is difficult to interpret and evidence-based conclusions on effectiveness of cautery for vas occlusion are difficult to make [1]. Even in the U.S., a variety of vas occlusion methods are used [10] which may be a reflection of the limited quality of data to support the use of any one occlusion technique. In 1995 (the latest national data available), 71% of vasectomies in the U.S. were done using cautery, up from 50% in 1991 [10,14].

In 10 published studies comparing ligation and cautery as methods of vas occlusion, the failure rates based on semen analysis ranged from 0–5% for cautery occlusion [1]. Results of the two best quality studies comparing ligation and excision to cautery (rated by the review paper's authors as moderate quality) are conflicting; one study found a higher failure risk based on semen analysis for cautery [15] and the other found a lower risk [5].

Men appear to reach azoospermia sooner in terms of both time and number of ejaculations following vasectomy by cautery compared to ligation and excision. When ligation and excision (with or without fascial interposition) were used, the probability of achieving azoospermia was in the range of 60–70% at 12–14 weeks postvasectomy [7,8,16]. We found that with cautery occlusion the probability of achieving azoospermia was 85% at 12 weeks. Edwards reported 100% azoospermia by 14 weeks with cautery occlusion [17]. Men may also reach severe oligozoospermia (< 100,000 sperm/mL) faster with cautery; the probability of success at 12 weeks was 95% in our study, compared to recently published results of 91% at 14 weeks for ligation and excision with fascial interposition and 82% for ligation and excision without fascial interposition [8].

The semen analysis patterns seen in the two vasectomy failures which were not technical failures are suggestive of very early recanalization given the extremely low sperm numbers at 2 weeks followed by a gradual increases back into the range of normal or potentially fertile sperm counts (see Figure 2). This is similar to the patterns reported for vasectomy failures when ligation and excision were used [7]. This concept of very early recanalization–rapid declines in sperm numbers in the first few weeks after vasectomy followed by a gradual rise back to the normal range–has not been widely commented on in the literature, most likely because early and frequent semen analyses after vasectomy are unusual. An additional strength of this study was that semen analysis follow-up continued after men achieved azoospermia. This is unusual in the published literature on vasectomy and provides a more detailed profile of sperm concentrations of men following vasectomy.

Ideally, vasectomy success is confirmed by semen analysis. In many low resource settings, however, semen analysis is not readily accessible or available. Protocols commonly used in these settings recommend 10–12 weeks or 15–20 ejaculations as endpoints for when men can begin to rely on their vasectomy for contraception [18,19]. Our data confirm results of two recent studies which also showed that 12 weeks after vasectomy is more reliable than 20 ejaculations as an endpoint and should reduce the risk of failure [7,8]. Our finding that the predictive value of one sample at 12 weeks for success at the end of the study was 99.7% has practical implications for vasectomy services. First, it suggests that one semen analysis at 12 weeks should be sufficient to indicate whether or not a man could begin to rely on his vasectomy for contraception, and second, it is further evidence that 12 weeks is a reasonable endpoint when semen analysis is not available, if cautery is used as the occlusion method.

Younger age accelerated success, with men younger than 35 years of age achieving both severe oligozoospermia and azoospermia sooner than older men. A similar age effect was seen when ligation and excision was used [8]. However, although statistically significant, the clinical significance of the age effect, at least with cautery occlusion, is likely to be minimal given the small absolute differences in probability of success between the age groups (see Table 2).

Our study was not designed to analyze the efficacy of the various occlusion procedures used at the study sites, but rather to estimate effectiveness of occlusion techniques that include use of cautery. Given the differences in the occlusion techniques used at the study sites (see Figure 1), it was not possible to determine any effect of the specific aspects of the techniques (such as fascial interposition or removal of a segment of vas), on overall success or failure. The two failures that occurred due to apparent recanalization were at the site using electrocautery without fascial interposition or excision of a segment of the vas. Which of the three specific aspects of the occlusion procedure may have contributed to the vasectomy failures cannot be determined.

The existing evidence in favor of using fascial interposition with cautery is weak [1]. However, fascial interposition has been shown to significantly improve the success of vasectomy by ligation and excision [8]. Even fewer data are available regarding differences in the effectiveness of thermal and electrocautery. A very small study found that vas occlusion was more complete based on histologic exam when thermal cautery was used [20] and a non-randomized comparative trial found a higher, but nonsignificant, risk of failure with electrocautery compared to thermal cautery [15].

Data on the importance of removing a segment of the vas are also limited. A recent study found no association between the length of vas excised and the risk of recanalization [21] and success has been reported when no vas tissue is removed with occlusion by cautery combined with fascial interposition [5,22-24]. Clearly, additional study is needed before any evidence-based conclusions can be made about the importance of the type of cautery, use of fascial interposition, and excision of a segment of the vas in reducing the risk of vasectomy failure.

One limitation of our study is that data are based on semen analysis as opposed to pregnancy. The risk of pregnancy associated with oligozoospermia following vasectomy–including the minimum sperm concentration that could lead to pregnancy–is not well characterized. Results from a study of male hormonal contraception showed that it is necessary to reduce sperm counts to under 3 million per mL to achieve reliable contraception in men with proven fertility [25]. These results, however, might not be strictly comparable to the situation following vasectomy. None the less, it is clear that the three vasectomy failures seen here had sperm concentrations well within the fertile range (Figure 2).

In addition, it is possible that recruitment bias could have affected the study results. There was a wide variation in the percent of men who agreed to participate in the study (U.K. 98%, U.S. 96%, Brazil 70%, Canada 25%), which appears to have been related to the convenience of providing semen samples at the different sites. We have no information on men who declined to participate in the study, although there are no obvious reasons why study outcomes of the sort being measured here would differ systematically for men agreeing to participate relative to those who did not. We cannot, however, rule this out as a source of bias.

Conclusions

Despite the lack of data from randomized trials, evidence is accumulating that the use of cautery for vas occlusion reduces the likelihood of failure. We found failure based on semen analysis to be rare following vasectomy by cautery. Vasectomy success is best confirmed by semen analysis. However in settings where semen analysis is not practical, using 12 weeks as a guideline for when men can rely on their vasectomy for contraception should lessen the risk of failure compared to using a guideline of 20 ejaculations after vasectomy. By 12 weeks after vasectomy, nearly all men (96%) showed either severe oligozoospermia or azoospermia, and the predictive values of one sample at 12 weeks for success at 24 weeks was 99.7%. Additional research is needed to determine the impact of the type of cautery, use of fascial interposition, and the importance of excision of a segment of the vas on the risk of failure associated with vasectomy by cautery.

Competing interests

None of the authors have received reimbursements, fees, funding, or salary from an organization that may in any way gain or lose financially from the publication of this paper in the past five years; have held any stocks or shares in an organization that may in any way gain or lose financially from the publication of this paper; or have any other financial or non-financial competing interests to declare in relation to this paper.

Authors' contributions

MB participated in the conception, design, management, and analysis of the study, and drafted the manuscript. BI participated in the conception, design, and analysis of the study, and was primarily responsible for managing and coordinating the study's implementation. MC participated in the design of the study and was primarily responsible for the statistical analysis. DS participated in the conception, design, management and analysis of the study. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following clinical investigators and study coordinators whose work was essential to the study's success: C. Athayde, M. Sánchez and G. Atta, Salvador, Brazil; M. Tittlit and L. Caron, Québec City, Québec, Canada; W. Thompson, E. Turner and F. Roseman, Oxford, U.K.; and D. Sparks, Seattle, Washington, U.S., and Gilles Chabot for drawings of the vasectomy techniques. Partial support for this study was provided by EngenderHealth with funds from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Cooperative Agreement # HRN-A-00-98-00042-00 and Family Health International (FHI) with funds from USAID, Cooperative Agreement # CCP-A-00-95-00022-02, although the views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of EngenderHealth, FHI or USAID.

Contributor Information

Mark A Barone, Email: mbarone@engenderhealth.org.

Belinda Irsula, Email: birsula@fhi.org.

Mario Chen-Mok, Email: mchen@fhi.org.

David C Sokal, Email: dsokal@fhi.org.

the Investigator study group, Email: birsula@fhi.org.

References

- Labrecque M, Dufresne C, Barone MA, St-Hilaire K. Vasectomy Surgical Techniques: A Systematic Review. BMC Medicine. 2004;2:21. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-21. http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcurol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack AE, Barone MA. Male sterilization. In: Sciarra JJ, editor. In Gynecology and Obstetrics. Vol. 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes M, Flick A, Barone MA, Amatya R, Pollack AE, Otero-Flores J, Juarez C, McMullen S. Results of a Pilot Study of the Time to Azoospermia After Vasectomy in Mexico City. Contraception. 1997;56:215–222. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(97)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. Contraceptive failure in China. Contraception. 2002;66:173–178. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrecque M, Nazerali H, Mondor M, Fortin V, Nasution M. Effectiveness and complications associated with 2 vasectomy occlusion techniques. J Urol. 2002;168:2495–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazerali H, Thapa S, Hays M, Pathak LR, Pandey KR, Sokal DC. Vasectomy effectiveness in Nepal: a retrospective study. Contraception. 2003;67:397–401. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(03)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone MA, Nazerali H, Cortes M, Chen-Mok M, Pollack AE, Sokal D. A Prospective Study of Time and Number of Ejaculations to Azoospermia after Vasectomy by Ligation and Excision. J Urol. 2003;170:892–896. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000075505.08215.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal D, Irsula B, Hays M, Chen-Mok M, Barone MA, the Investigator Study Group Vasectomy by Ligation and Excision, With Versus Without Fascial Interposition: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Medicine. 2004;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-6. http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcmed/2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . Male and Female Sterilisation (Guideline no. 4) London: RCOG Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Haws JM, Morgan GT, Pollack AE, Koonin LM, Magnani RJ, Gargiullo PM. Clinical aspects of vasectomies performed in the United States in 1995. Urol. 1998;52:685–91. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00274-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EngenderHealth Contraceptive Sterilization: Global Issues and Trends. New York. 2002.

- WHO laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and sperm-cervical mucus interaction. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harris EK, Albert A. Survivorship Analysis for Clinical Studies. Marcel Deckker, New York; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Marquette CM, Koonin LM, Antarsh L, Gargiullo PM, Smith JC. Vasectomy in the United States, 1991. AJPH. 1995;85:644–649. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.5.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SQ, Xu B, Hou YH, et al. Relationship between vas occlusion techniques and recanalization. Adv Contra Del Sys. 1994;10:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKnijff DWW, Vrijhof HJEJ, Arends R, et al. Persistence or reappearance of nonmotile sperm after vasectomy: Does it have clinical consequences? Fertil Steril. 1997;67:332–335. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81920-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards IS. Earlier testing after vasectomy based on the absence of motile sperm. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55706-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huezo CM, Carignan CS. Medical and Service Delivery Guidelines for Family Planning. 2. London: Stephen Austin and Sones, Ltd; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher RA, Rinehart W, Blackburn R, Geller JS. The Essentials of Contraceptive Technology. Baltimore, MD: Population Information Program, Centre for Communication Programs, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. 1997.

- Schmidt SS. The Vas after Vasectomy: Comparison of Cauterization methods. Urol. 1992;40:468–470. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(92)90468-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrecque M, Hoang D-Q, Turcot L. Association between the length of the vas deferens excised during vasectomy and the risk of postvasectomy recanalization. Fertil and Steril. 2003;79:1003–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04924-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt SS. Vasectomy by section, luminal fulguration and fascial interposition. Br J Urol. 1995;76:373–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denniston GC, Kuehl L. Open-ended vasectomy: Approaching the ideal technique. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1994;7:285–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss WM. A comparison of open-end versus closed-end vasectomies: A report on 6220 cases. Contraception. 1992;46:521–525. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(92)90116-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Task Force on Methods for the Regulation of Male Fertility Contraceptive efficacy of testosterone-induced azoospermia and oligozoospermia in normal men. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:821–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]