Abstract

Snapping hip syndrome is an audible or palpable snap in a hip joint during movement which may be accompanied by pain or locking. It is typically seen in young athletes performing activities requiring repeated extreme movements of the hip. It may also follow a physical trauma, intramuscular injections or surgeries. There are two main forms of snapping hip: extra- or intra-articular. Extra-articular snapping hip is elicited by an abnormal movement of specific tendons and is divided into two forms: internal and external. The internal form of snapping hip syndrome is attributed to an abrupt movement of an iliopsoas tendon against an iliopectineal eminence. Radiograph results in patients with this form of snapping tend to be normal. Dynamic ultrasound is the gold standard diagnostic technique in both forms of extra-articular snapping hip syndrome. The objective of the following text is to describe a step-by-step dynamic ultrasonography examination in internal extra-articular snapping hip syndrome in accordance to the proposed checklist protocol. To evaluate abrupt movement of an involved tendon, the patient needs to perform specific provocation tests during the examination. With its real-time imaging capabilities, dynamic ultrasonography detects the exact mechanism of the abnormal tendon friction during hip movement in a noninvasive way. It also allows for a diagnosis of additional hip tissue changes which may be causing the pain.

Keywords: snapping hip syndrome, dynamic ultrasonography, iliopsoas tendon

Abstract

Zespół trzaskającego biodra klinicznie manifestuje się słyszalnym lub odczuwalnym przez pacjenta przeskakiwaniem w stawie biodrowym podczas ruchu, któremu może towarzyszyć ból oraz blokowanie w stawie. Problem ten najczęściej dotyczy młodych sportowców wykonujących powtarzalne ćwiczenia z wykorzystaniem pełnego zakresu ruchu w stawie biodrowym. Przyczyną zespołu trzaskającego biodra mogą być również: przebyty uraz, ostrzykiwanie okolicy biodra lub zabieg chirurgiczny. Ze względu na etiologię zespołu trzaskającego biodra wyróżnia się jego dwie podstawowe formy: wewnątrzi zewnątrzstawową. Zespół zewnątrzstawowy jest związany z nieprawidłowym ruchem ścięgien i w zależności od nieprawidłowego ruchu danej struktury anatomicznej może występować jako forma wewnętrzna lub zewnętrzna. Złotym standardem w obrazowaniu zewnątrzstawowego zespołu trzaskającego biodra jest dynamiczne badanie ultrasonograficzne. W pracy zaprezentowano schemat dynamicznego badania ultrasonogra-prawificznego u pacjentów z podejrzeniem zewnątrzstawowego zespołu trzaskającego biodra o podtypie wewnętrznym. Aby prawidłowo ocenić ruchomość ścięgien biorących udział w zespole trzaskającego biodra, konieczne jest przeprowadzenie testów prowokacyjnych. Ultrasonografia ze względu na możliwość obrazowania poruszających się ścięgien w czasie rzeczywistym pozwala na nieinwazyjne zobrazowanie dokładnego mechanizmu konfliktowania ścięgna. Dodatkowo badanie to pozwala na rozpoznanie innych często towarzyszących patologii w stawie biodrowym, takich jak zapalenie kaletki czy ścięgna.

Introduction

Snapping hip syndrome is an audible or palpable snap in a hip during movement which may be accompanied by pain, locking, or a sharp stabbing sensation. The estimated prevalence of snapping hip syndrome in general population is 5% to 10%, and it is much higher in the population of young athletes. All activities requiring repeated extreme movements of the hip predispose to the development of snapping hip. The symptoms tend to occur more frequently among soccer players, weight lifters or runners, but the syndrome is the most common in ballet dancers(1–3). Snapping hip syndrome may follow a physical trauma, an intramuscular injection into the gluteus maximus muscle, a surgical knee reconstruction using a portion of the iliotibial band, or a total hip arthroplasty. The presence of a small femoral neck angle (coxa vara) and developmental dysplasia may also lead to the development of snapping hip syndrome.

There are two main forms of snapping hip: extra or intraarticular. Intra-articular hip pathologies include acetabular labral tears, cartilage defects, loose bodies. Extra-articular snapping may occur in the lateral or anterior region of the hip, depending on which tendon is involved in the snapping movement. The lateral form of extra-articular snapping hip (external snapping hip) is caused by a movement of the iliotibial band or gluteus maximus across the greater trochanter. Conversely, the anterior form (internal snapping hip) is attributed to the iliopsoas tendon snapping over the iliopectineal eminence. Patients with internal snapping hip report difficulty with running, standing up from a seated position, or getting in and out of the car(1, 4, 5).

The objective of the following text is to describe a step-by-step dynamic ultrasonography examination in internal extra-articular snapping hip syndrome in accordance to the proposed checklist protocol. Also, we would like to discuss how to perform specific provocation tests to evaluate an abrupt movement of an involved tendon.

Anatomy

A review of normal US hip anatomy is crucial for a good understanding of snapping hip etiology. Internal form of snapping hip is elicited by an abrupt movement of the iliopsoas tendon. The iliopsoas tendon is composed of two muscles: the psoas major muscle and the iliacus muscle. The psoas major arises medially from the anterior surface of the transverse processes, the lateral border of the vertebral bodies, and the corresponding intervertebral fibrocartilages from Th12 to L5. The iliacus muscle originates laterally from the upper two-thirds of the iliac fossa, from the inner lip of the iliac crest, and the anterior sacroiliac, lumbosacral and iliolumbar ligaments. The psoas major and some fibres of iliacus muscle insert through the iliopsoas tendon into the lesser trochanter when the remaining part of the iliacus muscular fibres insert below the lesser trochanter directly to the femur. The bony structures which are involved in internal snapping are the iliopectineal eminence (also known as the iliopubic eminence) of the pelvic brim, or the anterior aspect of the femoral head with the associated joint capsule and labrum. The iliopectineal eminence is an elevation of the pelvis situated at the level where iliac and pubic bones connect (Fig. 1)(1, 5).

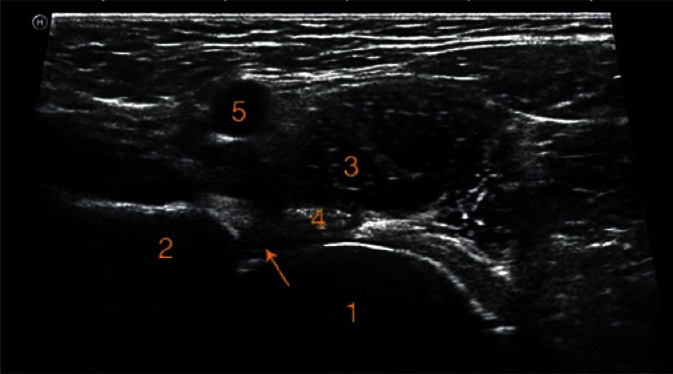

Fig. 1.

Normal anatomical structures of the anterior aspect of the hip. Ultrasound image with transducer in a transverse plane: the femoral head (1), the iliopectineal eminence (2), the iliopsoas muscle (3), the iliopsoas tendon (4), the femoral vein (5) the labrum (arrow)

Mechanism

When the limb is in a neutral position, the iliopsoas tendon lays over the iliopectineal eminence of the pelvis. During hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation, the tendon moves away from the bone when compared to a nonsnapping hip. When the patient moves the limb back to its neutral position, the tendon follows a return path, and snaps against the bone, making an audible and/or painful snap (Fig. 2)(6). Deslandes et al. observed abrupt movements of the iliopsoas tendon using dynamic ultrasonography, and described a new mechanism of the snapping. In that research snapping was mostly provoked by an abrupt movement of the iliopsoas tendon around the iliacus muscle. When the tendon moves away from the bone, it rolls anteriorly and laterally over a part of the iliacus muscle. The part of the iliacus muscle is located between the tendon and the superior pubic ramus. As the tendon follows the reverse path, the part of the iliacus muscle is released laterally, allowing an abrupt return of the tendon(7).

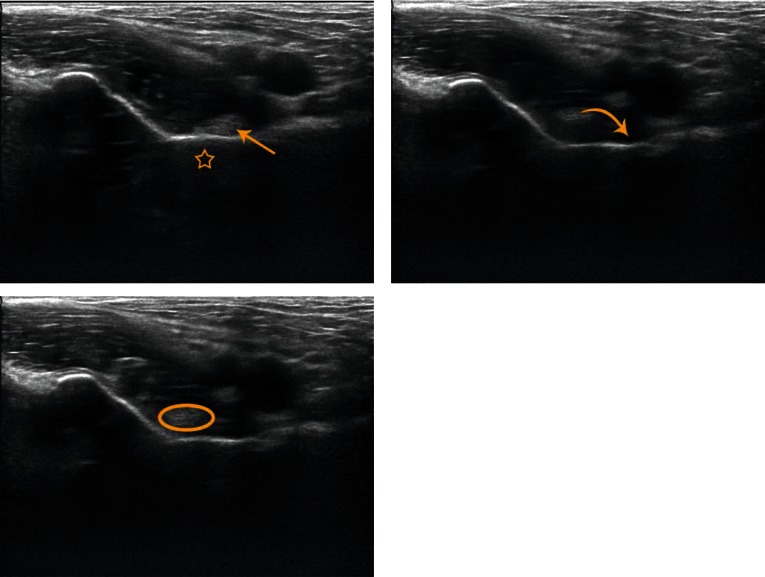

Fig. 2.

Transverse oblique sonograms of the anterior aspect of the hip joint. During neutral position of the limb the iliopsoas tendon (straight arrow) adjacent to the iliopectineal eminence (*). During hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation the iliopsoas tendon moves away from the bone (oval shape). When the limb comes back to neutral position, the iliopsoas tendon (curved arrow) follows the reverse path and snaps abruptly against the iliopectineal eminence

A rare etiology of anterior snapping hip refers to calcific tendinitis of the rectus femoris muscle. Calcific tendinitis of the direct or indirect head of the rectus femoris leads to thickening of the tendon, and might activate painful snapping(5, 8, 9).

Bursitis

Another anatomical structure which may be involved in internal snapping hip is the iliopsoas bursa. It separates distal the iliopsoas tendon from the anterior capsule of the joint and often communicates with the hip joint. Repetitive friction of the iliopsoas tendon may lead to the enlargement of the bursa, seen in the US images as a fluid collection in a typical bursa location, which is medial and deep to the iliopsoas muscle, and may extend along the iliopsoas muscle(10). The enlargement of the bursa usually is the main cause of pain, and can also lead to other symptoms when compressing the surrounding structures, such as vessels or nerves. Ultrasonography is very useful in detecting all extra-articular cystic lesions, at the same time it serves as a guide for needle aspirations of the bursa, or can be used for drug injections(1, 11).

Tendinitis

Repetitive friction of the iliopsoas tendon may also lead to its inflammation. The inflamed tendon has hypoechoic appearance, and might be thicker when compared to the contralateral side. The thickening of the tendon may further accentuate the snapping sound(1, 12). Another thing to remember when scanning tendons is that all highly ordered anatomical structures like tendons or ligaments have typical echogenic appearance. When the sonographic beam is perpendicular to the tendon, the sound waves are maximally reflected, and return to the transducer. Any other angle of the beam results in a decreased amount of sound energy returning to the transducer. This phenomenon is called anisotropy, and may cause artifactual hypoechoic appearance of the tendon, leading to a mistaken diagnosis(13).

Iliopsoas tendon bifurcation

An anatomic variant of the iliopsoas tendon is its complete or partial bifurcation, which may contribute to internal snapping. In a neutral position of the hip, medial and lateral heads of the bifurcated tendon both overly the superior pubic bone. When the hip is moved from its neutral position to the so called frog-leg position (the hip is flexed, abducted, and externally rotated), the medial head of the bifurcated tendon abruptly moves over the stable lateral head, eliciting snapping. When the hip moves back to the neutral position, the medial head of the double iliopsoas tendon follows a reversed path (moving medially from the lateral location), once again moving over the lateral head, provoking another snapping over the pelvis(1, 4, 7).

Dynamic ultrasonography

As X-ray is the modality dedicated for evaluation of bony structures, results from plain radiographs in patients with extra-articular snapping hip tend to be normal. Dynamic ultrasound is the gold standard diagnostic technique in both forms of extra-articular snapping hip syndrome(6, 14). In dynamic ultrasonography, the hip should be moved through the motion that elicits the snap, but each examination should be started with a static scan. Using linear 9 to 12 MHz transducer, transverse and longitudinal sonographic scanning of the anterior region of both hips is performed. In the case of larger patients, it is helpful to use curvilinear transducer of less than 10 MHz . The general rule is to use the highest frequency transducer to achieve the highest resolution. Also, colour or power Doppler sonography may be used to detect the possible inflammation(10).

Provocation tests

During dynamic ultrasound evaluation of internal snapping, the transducer should be placed in the anterior part of the hip. At the beginning when scanning the hip in a sagittal oblique plane, the femoral head and neck are the landmark structures (Fig. 3). Then, the transducer can be turned transversely over the femoral head to evaluate the iliopsoas tendon and muscle (Fig. 4). To evaluate the rectus femoris, the transducer should be moved laterally at the level of the anterior inferior iliac spine(6, 10, 15).

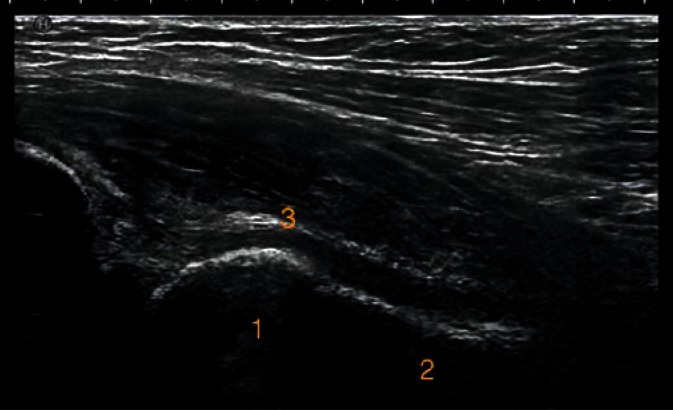

Fig. 3.

Normal anatomical structures of the anterior aspect of the hip. Ultrasound image with the transducer in a sagittal oblique plane: the femoral head (1), the femoral neck (2), the anterior capsule (3)

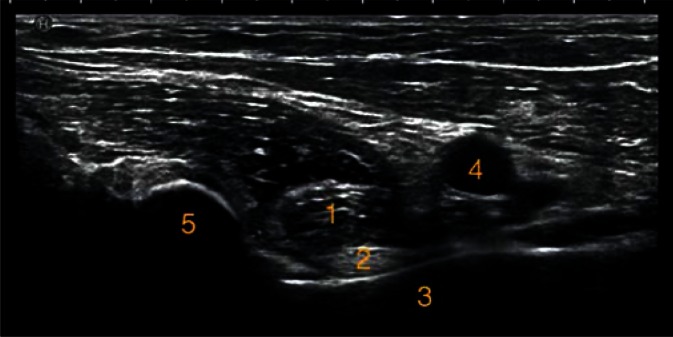

Fig. 4.

Normal anatomical structures of the anterior aspect of the hip. Ultrasound image with transducer in a transverse oblique plane: the iliopsoas muscle (1), the iliopsoas tendon (2), the iliopectineal eminence (3), the femoral vein (4), anterior inferior iliac spine (5)

For best evaluation of the iliopsoas complex, the transducer should be placed transversally at the level of the ilium superior, and positioned in the oblique axial plane.

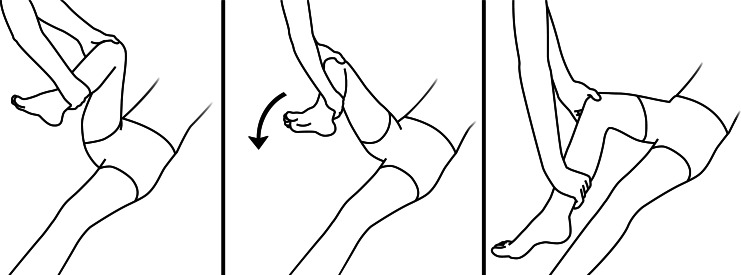

The patient stays in a supine position, and moves the leg from extension, adduction, and internal rotation to flexion, abduction, and external rotation, while the assisting person actively supports the patient’s limb (Fig. 5). This extra assistant helps to concentrate on the images and prevent probe dislocation during the limb movement. Dynamic ultrasonography is an operator-dependent technique, and requires some training. In our experience, some patients are very aware of the exact movements that evoke the snap, and those movements may be different from standard provocation tests. In these cases, we recommend to start the dynamic examination with the movements indicated by the patient.

Fig. 5.

The patient stays in a supine position. The leg moves from extension, adduction, and internal rotation to flexion, abduction, and external rotation, while the assisting person actively supports the patient’s limb

Treatment

Most cases of snapping hip syndrome may be resolved with conservative treatment. That includes rest, avoidance of aggravating activities, stretching exercises, and anti-inflammatory medication. In the case of inflammation of the local bursa or tendon sheath, a local anesthetic or corticosteroid can be injected. Conservative treatment is very effective in resolving the pain, though most of the patients still report a snapping sensation(1). Laible et al. have described conservative treatment as a very effective therapy which should be considered as the primary treatment for iliopsoas syndrome(16). Surgery may relax the involved tendon by its lengthening or complete release, however surgical intervention may result in a prolonged hip flexion or abduction weakness. The endoscopic release is reported to be a better manner of treatment of snapping hip syndrome than open procedures, but it may lead to complications in patients with undiagnosed tendon bifurcation. In these patients performing not sufficient capsulotomy may lead to incomplete lengthening by missing one of the heads of the bifid tendon. This is one of the reasons why snapping hip syndrome, which is usually evident in the physical examination, always needs confirmation in dynamic ultrasonography(3, 4, 17).

Conclusions

With its real-time imaging capabilities, dynamic ultrasonography noninvasively detects the exact mechanism of the abnormal tendon friction during hip movement with good contrast resolution for soft tissues. A good understanding of the precise mechanism of internal extra-articular snapping hip syndrome guides further successful treatment. Ultrasonography allows to picture additional hip tissue changes like tendinopathy or bursitis. It is a relatively cheap technique with few artifacts caused by orthopedic hardware when compared to MR. On the other hand, the prevalence of provoked abnormal movement of the iliopsoas tendon in non-symptomatic patients may be up to 40%(5). This study has shown the risk of overestimating the syndrome. To avoid an overlooked diagnosis, it is important to remember about the correlation between the abrupt movement of the tendon and the clinical painful and/or audible snap presented by the patient. Also, this technique requires some training, as it is an operator-dependant technique.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not report any financial or personal connections with other persons or organizations, which might negatively affect the contents of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication.

References

- 1.Lewis CL. Extra-articular snapping hip: a literature review. Sports Health. 2010;2:186–190. doi: 10.1177/1941738109357298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen WC, Cope R. Coxa saltans: the snapping hip revisited. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:303–308. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winston P, Awan R, Cassidy JD, Bleakney RK. Clinical examination and ultrasound of self-reported snapping hip syndrome in elite ballet dancers. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:118–126. doi: 10.1177/0363546506293703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shu B, Safran MR. Case report: bifid iliopsoas tendon causing refractory internal snapping hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:289–293. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1452-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tatu L, Parratte B, Vuillier F, Diop M, Monnier G. Descriptive anatomy of the femoral portion of the iliopsoas muscle. Anatomical basis of anterior snapping of the hip. Surg Radiol Anat. 2001;23:371–374. doi: 10.1007/s00276-001-0371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillin R, Marchand AJ, Roux A, Niederberger E, Duvauferrier R. Imaging of snapping phenomena. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1343–1353. doi: 10.1259/bjr/52009417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deslandes M, Guillin R, Cardinal E, Hobden R, Bureau NJ. The snapping iliopsoas tendon: new mechanisms using dynamic sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:576–581. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierannunzii L, Tramontana F, Gallazzi M. Case report: calcific tendinitis of the rectus femoris: a rare cause of snapping hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2814–2818. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1208-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azizi HF, Lee SW, Oh-Park M. Ultrasonography of snapping hip syndrome. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;94:e10–e11. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobson JA, Khoury V, Brandon CJ. Ultrasound of the groin: techniques, pathology, and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:513–523. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yukata K, Nakai S, Goto T, Ikeda Y, Shimaoka Y, Yamanaka I, et al. Cystic lesion around the hip joint. World J Orthop. 2015;6:688–704. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i9.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czyrny Z. Muscles – histology, micro/macroanatomy and US anatomy, a brand new perspective. Ultrasonografia. 2012;12:9–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang A, Miller TT. Imaging of tendons. Sports Health. 2009;1:293–300. doi: 10.1177/1941738109338361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fantino O, Borne J, Bordet B. Conflicts, snapping and instability of the tendons. Pictorial essay. J Ultrasound. 2012;15:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bancroft LW, Blankenbaker DG. Imaging of the tendons about the pelvis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:605–617. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laible C, Swanson D, Garofolo G, Rose DJ. Iliopsoas syndrome in dancers. Orthop J Sports Med. 2013;1:2325967113500638. doi: 10.1177/2325967113500638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilizaliturri VM, Jr, Camacho-Galindo J. Endoscopic treatment of snapping hips, iliotibial band, and iliopsoas tendon. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2010;18:120–127. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181dc57a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]