Abstract

Heterotrimeric G proteins are localized to the plasma membrane where they transduce extracellular signals to intracellular effectors. G proteins also act at intracellular locations, and can translocate between cellular compartments. For example, Gαs can leave the plasma membrane and move to the cell interior after activation. However, the mechanism of Gαs translocation and its intracellular destination are not known. Here we use bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) to show that after activation, Gαs rapidly associates with the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and endosomes, consistent with indiscriminate sampling of intracellular membranes from the cytosol rather than transport via a specific vesicular pathway. The primary source of Gαs for endosomal compartments is constitutive endocytosis rather than activity-dependent internalization. Recycling of Gαs to the plasma membrane is complete 25 min after stimulation is discontinued. We also show that an acylation-deacylation cycle is important for the steady-state localization of Gαs at the plasma membrane, but our results do not support a role for deacylation in activity-dependent Gαs internalization.

Keywords: endosome, G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), heterotrimeric G protein, intracellular trafficking, lipase, protein acylation, protein palmitoylation, endosomes

Introduction

Heterotrimeric G proteins are best known for their role in transducing signals from the extracellular environment across the plasma membrane (1). However, it is becoming increasingly apparent that these signaling molecules have important functions in other cellular locations (2). Therefore, it is important to know how G proteins are distributed among various intracellular compartments, and how these proteins traffic between the plasma membrane, the cytosol, cytoskeletal elements, and intracellular organelles both in their resting state and when they are activated.

The most well studied example of activity-dependent G protein trafficking occurs in the retina, where intense illumination promotes the dissociation of transducin from rod outer segment disks and the subsequent translocation of both Gαt and Gβγ into the rod inner segment (3). Activity-dependent translocation of Gα and Gβγ subunits occurs in other cells as well (4, 5), most notably for Gαs, the subunit responsible for stimulation of adenylate cyclase. Stimulation of a cognate receptor or inhibition of GTPase activity promotes activation and translocation of Gαs from the plasma membrane to the cell interior (6–8).

One important yet poorly understood aspect of Gαs internalization is the intracellular destination of this G protein. Cell fractionation studies have shown that a large amount of constitutively active Gαs is found in the soluble fraction, suggesting that active Gαs may simply become soluble in the cytosol (8, 9). However, only a small amount of Gαs enters the soluble fraction after receptor-mediated activation, consistent with vesicle-mediated internalization and continued association with membranes. Imaging studies have shown that internalized Gαs can appear to be diffuse in the cytosol (8, 9), but association with intracellular vesicles has also been observed (10–12). Therefore, the trafficking itinerary of active Gαs has not been clearly defined. This question has taken on greater significance with the recent realization that receptors can continue to activate Gαs after agonist-induced endocytosis (13–16). It is known that active receptors and Gαs internalize via distinct pathways (8, 10, 11, 17), but it is unclear how receptors and Gαs ultimately reach a common intracellular compartment. It is also thought that internalized Gαs recycles to the plasma membrane (8), but very little is known about how this occurs.

A related issue is the possible role of deacylation in activity-dependent Gαs internalization. Gαs subunits are anchored to the plasma membrane in part by palmitoylation of a single N-terminal cysteine residue (18, 19), and activation dramatically enhances the rate of palmitate turnover (20–22). A cytosolic thioesterase, acyl protein thioesterase 1 (APT1),2 has been shown to catalyze deacylation of Gαs in vitro, and this activity is inhibited by association with Gβγ (23). These findings suggest that activation may promote APT1-mediated net removal of palmitate and thereby release active Gαs from the plasma membrane, but direct evidence supporting this model has been not been reported.

Here we map the subcellular distribution of inactive and active Gαs using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). We find that inactive Gαs is constitutively located on the plasma membrane and on multiple endomembrane compartments, including endosomes. Upon activation, Gαs reversibly translocates from the plasma membrane to several endomembrane compartments, including the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and endosomes. Neither inhibition of APT1 with a broad-spectrum serine hydrolase inhibitor nor mutation of the critical cysteine prevented Gαs translocation. Our results are consistent with a model wherein active Gαs dissociates from the plasma membrane, translocates via a non-vesicular mechanism, and indiscriminately samples intracellular membranes. Our results do not support or rule out a role for thioesterase-mediated net depalmitoylation in translocation of active Gαs.

Results

The Subcellular Distribution of Gαs

BRET can occur between non-associated membrane-bound donors and acceptors provided that they both are located in the same compartment and the acceptor is present at sufficient density. If an array of acceptors targeted to different membrane compartments is coexpressed (one at a time) with a membrane-bound donor, then a map of the donor's subcellular localization can be drawn (24). The BRET signal between a donor protein of interest and acceptor membrane markers depends on the propensity of the protein of interest to associate with different membranes, but also on the density of acceptors expressed on the surface of each compartment, the efficiency of each marker as a BRET acceptor, and the relative surface area of each compartment. Therefore, this method can only provide a qualitative map of subcellular distribution. Nevertheless, BRET produced at a given membrane compartment is directly related to the fraction of the donor associated with that compartment; therefore this method can be used to track changes in the subcellular distribution of membrane proteins over time in populations of living cells (24–26).

To use this method to determine the subcellular distribution of Gαs, we replaced residues 73–84 in the α helical domain of this subunit with the BRET donor Rluc8 (27). Previous studies have shown that insertions as large as fluorescent proteins in this region do not interfere with Gαs function (10, 12). We coexpressed Gαs-Rluc8 with unlabeled Gβ1 and Gγ2 and six standard membrane compartment markers that were fused to the BRET acceptor Venus. These markers targeted the cytosolic surface of the plasma membrane, Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, and early, late, and recycling endosomes. Confocal imaging verified that each endomembrane marker labeled morphologically appropriate and distinct intracellular structures under conditions similar to those used for BRET experiments (Fig. 1A).

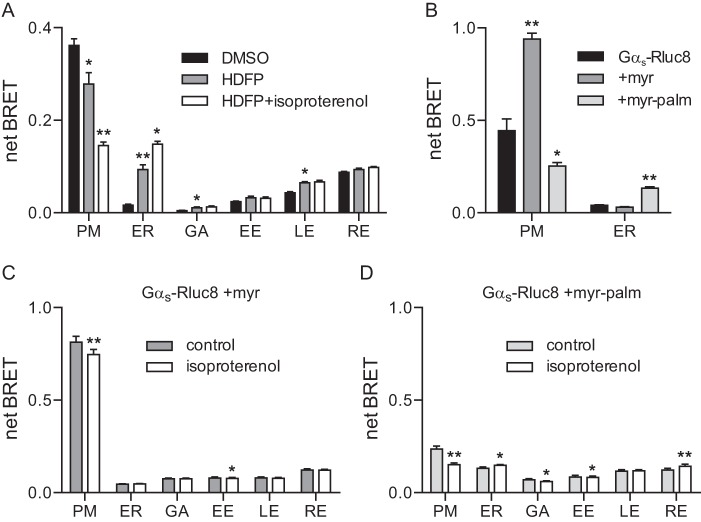

FIGURE 1.

BRET acceptors targeted to membrane compartments indicate the subcellular localization of Gαs-Rluc8. A, confocal images of HEK 293 cells expressing Venus-tagged markers of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria (MT), Golgi apparatus (GA), early endosomes (EE), late endosomes (LE), and recycling endosomes (RE). Approximately half of each panel is occupied by the cell interior. Scale bars, 3 μm. B, net BRET between Gαs-Rluc8 (with and without exogenous Gβ1 and Gγ2) and Gαs-Rluc8 IEK+ and acceptors localized to the plasma membrane (PM) or various intracellular compartments. Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 3–5 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA versus control, Dunnett's multiple comparisons).

We observed robust BRET between Gαs-Rluc8 and the plasma membrane acceptor (Fig. 1B), and much weaker BRET signals between Gαs-Rluc8 and endomembrane acceptors. The smallest endomembrane signals were observed at the Golgi apparatus, whereas the largest signals were observed at recycling endosomes (Fig. 1B). These results are consistent with previous studies that have shown that Gs is present at the plasma membrane, but also traffics constitutively through endosomal structures (4, 17, 28).

It has previously been shown that delivery of Gαs to the plasma membrane during biosynthesis depends on association with Gβγ (29). Consistent with this, we found that BRET produced by Gαs-Rluc8 at the plasma membrane decreased significantly when this subunit was expressed without exogenous Gβ1 and Gγ2 subunits (Fig. 1B). The BRET signal originating from recycling endosomes was also significantly smaller without exogenous Gβγ, whereas BRET originating from the endoplasmic reticulum was slightly but significantly larger. Trafficking of Gαs-Rluc8 to the plasma membrane in the absence of exogenous Gβγ could have been due to association with endogenous Gβγ dimers. To test this idea, we constructed a subunit (Gαs-Rluc8 IEK+) bearing mutations at the N-terminal Gβγ interface, as this mutant was shown previously to be highly defective with respect to plasma membrane association (29). Similarly, we found that BRET produced by Gαs-Rluc8 IEK+ at the plasma membrane was reduced even further than that produced by wild-type Gαs-Rluc8 in the absence of exogenous Gβγ, and BRET produced at recycling endosomes was similarly impaired (Fig. 1B). These results are consistent with a role for Gβγ in membrane targeting of nascent Gs heterotrimers (29), and demonstrate that BRET can be used to map the subcellular distribution of Gαs-Rluc8.

Activity-dependent Redistribution of Gαs

Several studies have shown that a pool of active Gαs leaves the plasma membrane and either enters the cytosol or associates with intracellular vesicles (6–12). Because the intracellular destination of Gαs is uncertain, we compared the subcellular distribution of Gαs before and after activation. Stimulation of coexpressed β2 adrenergic receptors (β2ARs) with the agonist isoproterenol for 10 min decreased BRET produced by Gαs-Rluc8 at the plasma membrane by ∼40% (Fig. 2A). Isoproterenol also increased BRET at several endomembrane compartments. The largest increase (∼100%) was observed at the endoplasmic reticulum, whereas small but significant increases (∼10%) were observed at late and recycling (but not early) endosomes (Fig. 2A). The relatively large BRET increase at the endoplasmic reticulum could reflect a specific trafficking itinerary for active Gαs-Rluc8. Alternatively, this difference could simply reflect the large surface area of the endoplasmic reticulum, which would allow this compartment to capture a large fraction of Gαs-Rluc8 if this protein is released into the cytosol to randomly sample endomembranes. In this case, isoproterenol should also induce large BRET increases at other intracellular organelles that have a large surface area. After the endoplasmic reticulum, the mitochondria have the largest collective surface area in HEK 293 cells (Fig. 1A), and indeed isoproterenol induced a 39 ± 6% increase in BRET between Gαs-Rluc8 and an acceptor located on the surface of mitochondria (p < 0.001, n = 7). Taken together these results are consistent with the notion that some active Gαs-Rluc8 is released into the cytosol and randomly samples endomembranes.

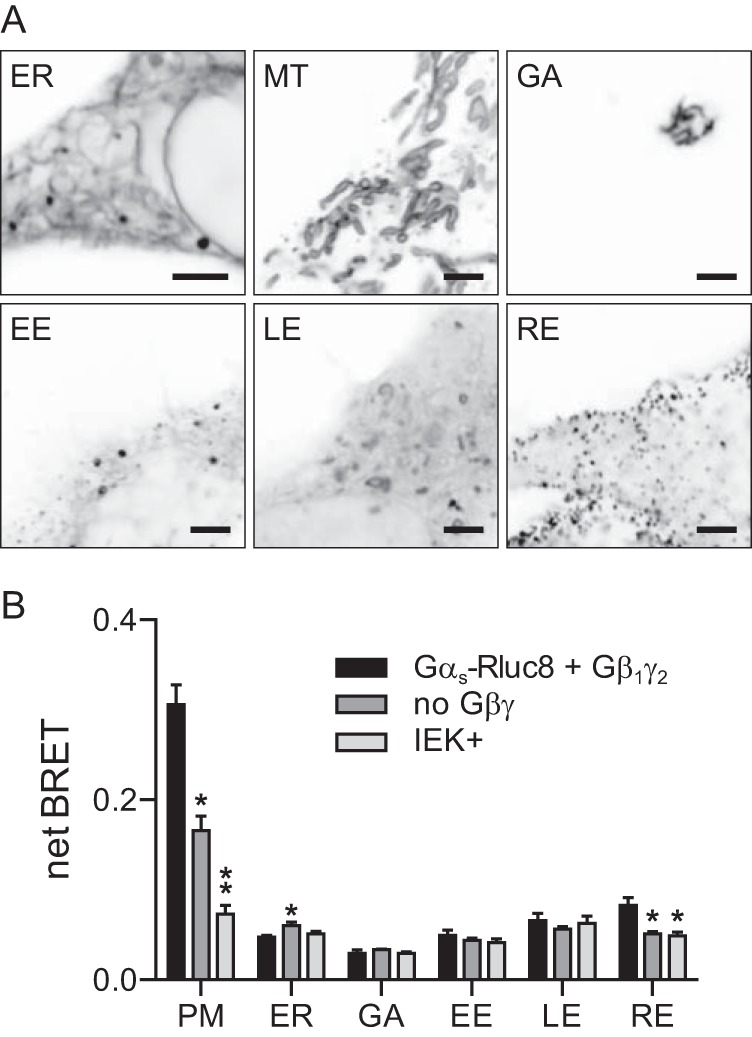

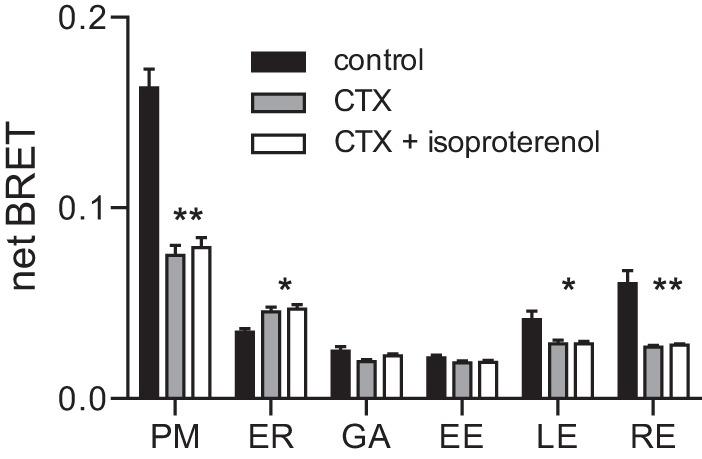

FIGURE 2.

Activity-dependent redistribution of Gαs-Rluc8. A, net BRET between Gαs-Rluc8 expressed with unlabeled Gβ1, Gγ2, β2AR, and acceptors localized to membrane compartments in control cells and in cells stimulated for 10 min with the β2AR agonist isoproterenol (10 μm). PM, plasma membrane; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GA, Golgi apparatus; EE, early endosomes; LE, late endosomes; RE, recycling endosomes. Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 18–25 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001 (paired t test). B, data points from individual experiments shown in panel A. C, a similar experiment to that shown in panel A with cells stimulated for 4 h with isoproterenol. Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 7 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05 (paired t test). D, data points from individual experiments shown in panel C.

We then examined the subcellular distribution of Gαs-Rluc8 after more prolonged activation of β2ARs. Stimulation with isoproterenol for 4 h decreased BRET at the plasma membrane and increased BRET at the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 2, C and D), similar to what was observed after stimulation for 10 min. However, prolonged activation significantly decreased BRET at all endosomal compartments (Fig. 2, C and D), i.e. the opposite of what was observed after stimulation for 10 min. Treatment with cholera toxin for 2–4 h produced a similar redistribution of Gαs-Rluc8 away from the plasma membrane and endosomes and toward the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 3). Cholera toxin also occluded BRET changes induced by acute stimulation with isoproterenol. These results indicated a biphasic effect of activation on Gαs-Rluc8 abundance in endosomes.

FIGURE 3.

Cholera toxin redistributes Gαs-Rluc8. Shown is net BRET between Gαs-Rluc8 and membrane markers in control cells, in cells treated for 2–3 h with cholera toxin (CTX; 10 μg ml−1), and in cells treated with cholera toxin and then isoproterenol for 10 min. PM, plasma membrane; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GA, Golgi apparatus; EE, early endosomes; LE, late endosomes; RE, recycling endosomes. Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 4 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA comparing CTX or CTX + isoproterenol to control, Tukey's multiple comparisons). No significant difference was observed between CTX and CTX + isoproterenol.

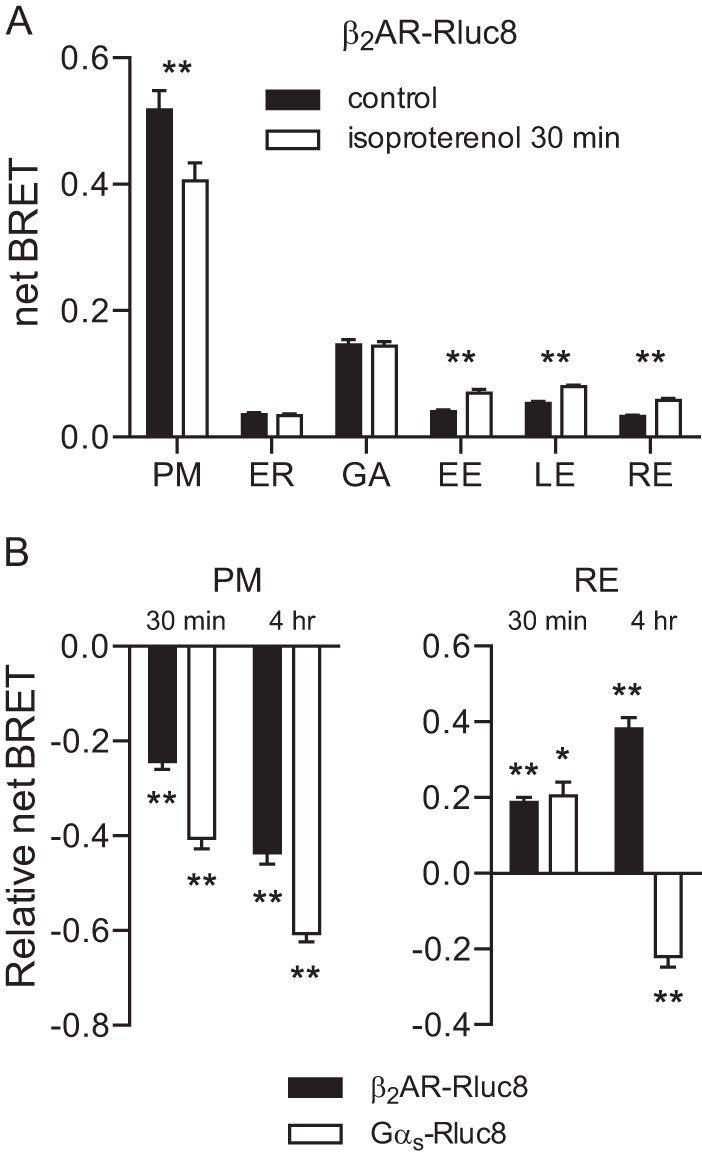

Previous studies have shown that β2ARs and Gαs localize to different intracellular structures after receptor activation (8, 10). To demonstrate this with BRET, we expressed β2AR-Rluc8 and our standard panel of membrane-localized acceptors. Prior to stimulation, β2AR-Rluc8 produced robust BRET at the plasma membrane and Golgi apparatus, and smaller signals at other endomembrane compartments (Fig. 4A). As was the case with Gαs-Rluc8, stimulation with isoproterenol for 30 min decreased BRET from β2AR-Rluc8 at the plasma membrane (25). Isoproterenol also increased BRET from β2AR-Rluc8 at endosomes, but these increases were much larger (∼50–100%) than those observed with Gαs-Rluc8, and were evident at all three endosomal compartments. Unlike what we observed with Gαs-Rluc8, isoproterenol did not increase BRET from β2AR-Rluc8 at the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 4A). We next directly compared β2AR-Rluc8 and Gαs-Rluc8 trafficking at both short (30-min) and long (4-h) time points. The abundance of both proteins at the plasma membrane decreased progressively over the course of 4 h (Fig. 4B). In contrast, although both proteins were more abundant in recycling endosomes 30 min after agonist stimulation, only β2AR-Rluc8 continued to accumulate in endosomes at 4 h, whereas Gαs-Rluc8 was depleted from this compartment. These results underscore the conclusion that β2ARs and Gαs are found in common endomembrane compartments, but traffic there via different mechanisms after receptor activation.

FIGURE 4.

Activity-dependent internalization of β2AR-Rluc8 and Gαs-Rluc8. A, net BRET between β2AR-Rluc8 and acceptors localized to membrane compartments in control cells and in cells stimulated for 30 min with isoproterenol. PM, plasma membrane; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GA, Golgi apparatus; EE, early endosomes; LE, late endosomes; RE, recycling endosomes. Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 6 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001 (paired t test). B, relative net BRET compared with vehicle-treated controls between β2AR-Rluc8 or Gαs-Rluc8 and acceptors localized to the plasma membrane or recycling endosomes in cells stimulated for 30 min or 4 h with isoproterenol. Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 9 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA versus vehicle, Dunnett's multiple comparisons).

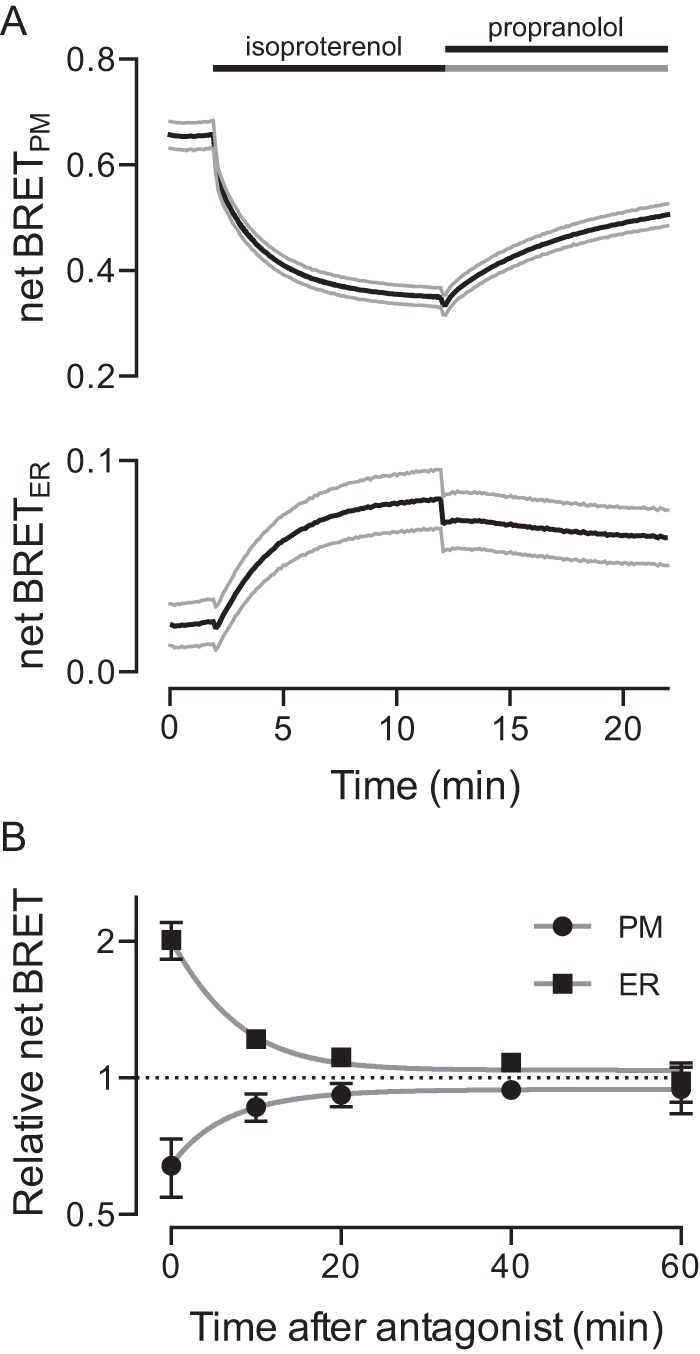

We next examined the kinetics of activity-dependent redistribution of Gαs-Rluc8 in more detail, focusing on the reciprocal changes in BRET at the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum. At room temperature (∼25 °C), stimulation with isoproterenol decreased BRET at the plasma membrane with a half-life (t½) of 95 s, and increased BRET at the endoplasmic reticulum with a similar half-life of 113 s (Fig. 5A). This time course is similar to the rate at which Gαs-fluorescent protein chimeras translocate from the plasma membrane after receptor activation (10, 12), but much slower than conformational changes associated with activation (30). The addition of the β2AR antagonist propranolol allowed recovery of BRET signals in both of these compartments (Fig. 5A). Full recovery required ∼25 min for both the plasma membrane (t½ = 320 s) and the endoplasmic reticulum (t½ = 256 s; Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

The time course of Gαs-Rluc8 internalization and recycling. A, net BRET at the plasma membrane (PM, top) and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER, bottom) during sequential addition of isoproterenol (10 μm) and the β2AR antagonist propranolol (20 μm). Lines, mean ± S.E. of n = 13 experiments. B, normalized net BRET (plotted on a log 2 scale) at the plasma membrane and the endoplasmic reticulum in cells that were sequentially exposed to isoproterenol (10 μm) and the β2AR antagonist alprenolol (20 μm). Symbols, mean ± S.E. of n = 4 independent experiments. Lines, least squares fits to a single exponential function.

Mechanisms of Reversible Gαs Translocation

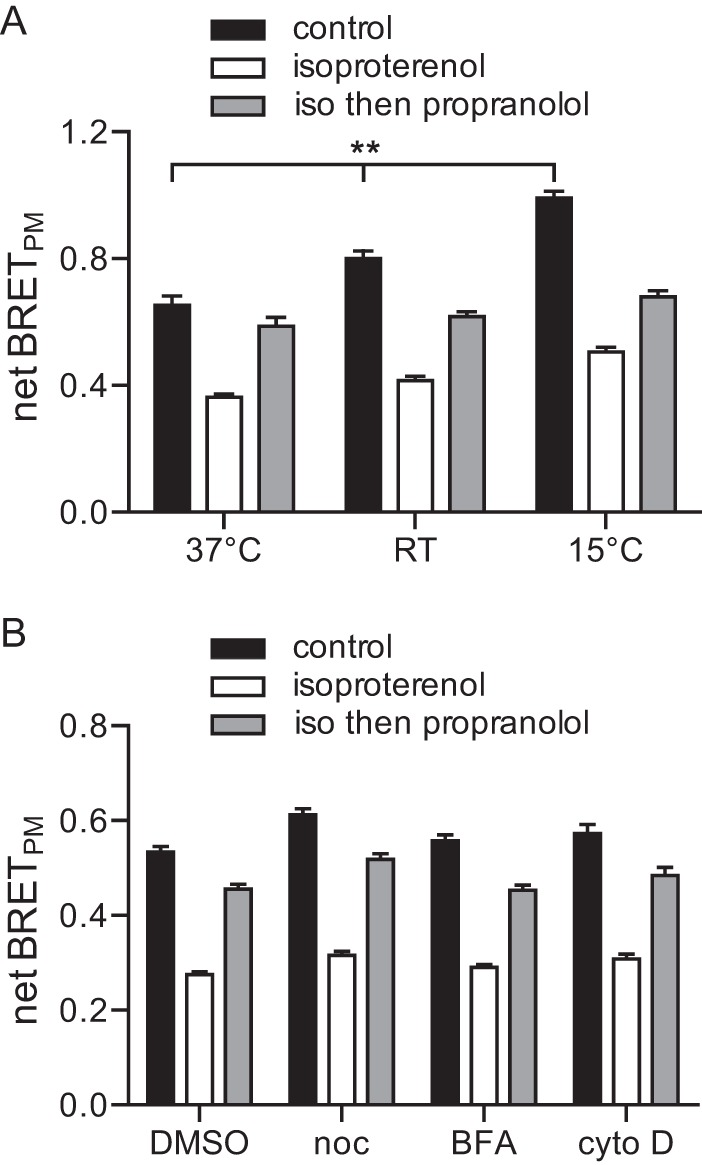

The mechanisms responsible for the translocation of Gαs away from and back to the plasma membrane after a period of activation are poorly understood. In particular, the roles of vesicular transport and palmitate cycling have not been firmly established. Therefore, we took advantage of the BRET assay to test these mechanisms. Vesicular transport is arrested by low temperatures (31); therefore we studied the loss and recovery of BRET from Gαs-Rluc8 at the plasma membrane in cells incubated at 37 °C, room temperature (∼25 °C), and 15 °C. Lowering the temperature significantly increased the baseline BRET signal from Gαs-Rluc8 at the plasma membrane, but did not affect the BRET decrease produced by isoproterenol (p > 0.05, n = 9; Fig. 6A). In contrast, lowering the temperature partially inhibited recovery of BRET at the plasma membrane, which after 15 min reached 90 ± 1% of the control value at 37 °C, but only 69 ± 1% of the control value at 15 °C (p < 0.001). The latter result suggested that vesicular transport may play a role in the return of internalized Gαs to the plasma membrane. However, disruption of microtubules with nocodazole had no effect on Gαs-Rluc8 internalization or recovery, and disruption of the Golgi apparatus with brefeldin A had only a small (but significant) effect on recovery of BRET at the plasma membrane (81 ± 0% of control versus 85 ± 0% of control for DMSO; p < 0.001; Fig. 6B), suggesting that Gαs recycles to the plasma membrane via a transport mechanism other than the classical secretory or recycling vesicular pathways.

FIGURE 6.

The sensitivity of Gαs-Rluc8 internalization and recycling to temperature and disruption of microtubules, actin, and the Golgi apparatus. A, net BRET at the plasma membrane in cells treated with vehicle (control), isoproterenol for 10 min (isoproterenol), or isoproterenol followed by propranolol for 15 min (iso then propranolol) in cells maintained throughout at 37 °C, room temperature (RT, ∼25 °C), and 15 °C. Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 9 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001; (one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparisons). The percentages of isoproterenol-induced decreases were not significantly different between any of the groups. The percentages of propranolol-induced recoveries were significantly different between all three groups (p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparisons). B, similar experiments to those shown in panel A, all performed at room temperature, in cells treated with vehicle (DMSO; n = 28), nocodazole (noc; 10 μm for 1 h; n = 12), brefeldin A (BFA; 10 μg ml−1 for 4 h; n = 13), and cytochalasin D (cyto D; 1 μm for 4 h; n = 13). Bars, mean ± S.E. The percentages of isoproterenol-induced decreases were not significantly different between any of the groups. The percentages of propranolol-induced recoveries were significantly different from DMSO only for brefeldin A (p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparisons).

APT1 removes the palmitoyl anchor from Gαs in vitro (23), and activation of Gαs increases the rate of palmitate turnover in cells (20–22). Therefore, it has been suggested that APT1-dependent depalmitoylation may be important for activity-dependent translocation of Gαs. To test this idea, we incubated cells with the broad-spectrum lipase inhibitor hexadecylfluorophosphonate (HDFP), which has previously been shown to inhibit more than 20 lipases, including APT1, and to attenuate basal Gαs palmitate turnover (32). Treatment with HDFP for 4 h decreased BRET from Gαs-Rluc8 at the plasma membrane, and increased BRET from Gαs-Rluc8 at the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and late endosomes (Fig. 7A). This result is consistent with a role for palmitate cycling in the steady-state localization of Gαs at the plasma membrane, as suggested previously for other palmitoylated membrane proteins (33). However, HDFP did not prevent isoproterenol-induced translocation of Gαs-Rluc8 from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 7A), suggesting that translocation did not require APT1 or another HDFP-sensitive hydrolase.

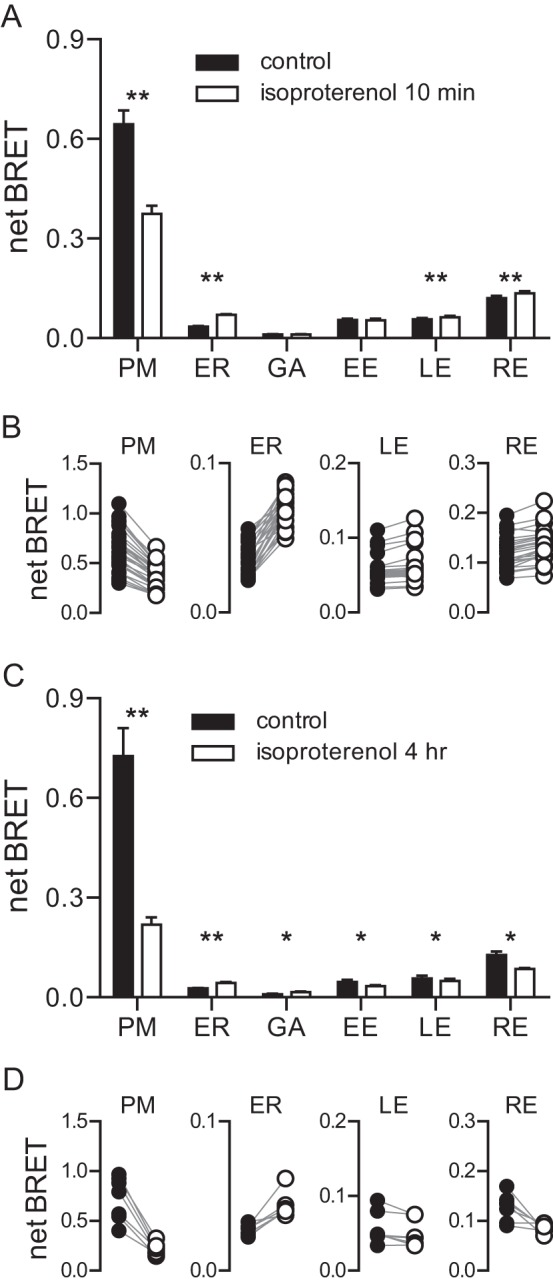

FIGURE 7.

The role of palmitate cycling in constitutive localization and activity-dependent redistribution of Gαs-Rluc8. A, net BRET at the plasma membrane and the endoplasmic reticulum generated by Gαs-Rluc8, Gαs-Rluc8 +myr, or Gαs-Rluc8 +myr-palm. PM, plasma membrane; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GA, Golgi apparatus; EE, early endosomes; LE, late endosomes; RE, recycling endosomes. Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 5 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA versus Gαs-Rluc8, Dunnett's multiple comparisons). B, net BRET between Gαs-Rluc8 expressed with unlabeled Gβ1, Gγ2, β2AR, and acceptors localized to membrane compartments in control cells, in cells treated with HDFP (20 μm) for 4 h, and in HDFP-treated cells stimulated for 10 min with isoproterenol (10 μm). Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 4 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA versus DMSO (for HDFP) or versus HDFP (for HDFP + isoproterenol), Tukey's multiple comparisons). C and D, net BRET between Gαs-Rluc8 +myr (C) or Gαs-Rluc8 +myr-palm (D) and acceptors localized to membrane compartments in control cells and in cells stimulated for 10 min with isoproterenol. Bars, mean ± S.E. of n = 8–10 independent experiments; **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05 (paired t test).

To further examine the possible role of palmitate cycling, we studied Gαs-Rluc8 subunits that were mutated to carry alternative N-terminal lipid anchors. We constructed Gαs-Rluc8 variants that were either myristoylated in addition to the usual palmitoylation (Gαs-Rluc8 +myr), or myristoylated but not palmitoylated (Gαs-Rluc8 +myr-palm) (9). A previous study has shown that Gαs +myr subunits are more strongly localized to the plasma membrane than wild-type Gαs and are resistant to activity-dependent internalization, whereas Gαs +myr-palm subunits are weakly localized to the plasma membrane, but are still susceptible to activity-dependent internalization (9). In agreement with these results, we found that Gαs-Rluc8 +myr produced significantly more BRET at the plasma membrane than wild-type Gαs-Rluc8 (Fig. 7B), and this signal was relatively resistant to isoproterenol (8 ± 1% decrease; Fig. 7C). In contrast, Gαs-Rluc8 +myr-palm produced significantly less BRET at the plasma membrane than wild-type Gαs-Rluc8, and significantly more BRET at the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 7B). Despite this weak localization at the plasma membrane, BRET from Gαs-Rluc8 +myr-palm at the plasma membrane still decreased by 36 ± 3% after stimulation with isoproterenol, and this coincided with a significant increase in BRET at the endoplasmic reticulum and recycling endosomes (Fig. 7D).

Discussion

The results of the present study extend previous studies of Gαs subcellular localization and trafficking in several important ways. Our results show that Gαs is present on the cytosolic surface of several endomembrane compartments both before and after activation. Previous studies have indicated that G proteins associate with intracellular membranes during biosynthesis (4) and that Gαs undergoes constitutive clathrin-independent endocytosis (17). Our results confirm the presence of this subunit at the endoplasmic reticulum and at least three distinct endosomal compartments. Our results also show that receptor-mediated activation of Gαs leads to only small increases in the availability of this subunit at endosomes, and this only after relatively short-term receptor activation. Activation for 4 h actually decreased the availability of Gαs at endosomes, presumably because the source of endosomal membranes (the plasma membrane) was depleted of Gαs. Therefore, we conclude that constitutive endocytosis is the primary supplier of Gαs to endosomes. It is now recognized that G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) can continue to activate Gs in endosomes (13–16), and our results suggest that internalized receptors largely activate heterotrimers that are already present in these compartments.

Although it has been known for 30 years that a fraction of Gαs leaves the plasma membrane after activation (6–8), the intracellular destination of this subunit has not been clearly established. Imaging studies have suggested that Gαs internalizes into vesicles (10–12), and one study identified Rab11-positive (recycling) endosomes as a target compartment (10). However, other imaging studies have suggested a more diffuse cytosolic (i.e. soluble) distribution of active Gαs (8, 9). Our finding that internalization of activated Gαs persists at 15 °C suggests that vesicular trafficking is not involved, and is consistent with previous findings with more specific inhibitors of endocytic trafficking (8, 10). Moreover, the magnitudes of agonist-induced BRET increases at endosomes are too small to be consistent with robust endocytosis into these compartments. This interpretation is supported by the observation that Gαs-Rluc8 appears at the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria without an appreciable delay after leaving the plasma membrane. Our results are thus consistent with a model wherein the affinity of activated Gαs for membranes is decreased (but not abolished), and subunits diffuse through the cytosol to randomly sample membrane compartments. Because the endoplasmic reticulum has the largest surface area of any endomembrane compartment, this organelle captures the largest fraction of the newly available Gαs. Indiscriminate sampling of intracellular membranes by activated Gαs is consistent with previous imaging studies (8–12), which have not identified a consensus intracellular target for this subunit.

Our results may also help to explain why, in cell fractionation studies, the appearance of Gαs in the soluble fraction is more evident after chronic activation (by mutation or ADP-ribosylation) than after receptor-mediated activation (8, 9). Immediately after receptor activation, we observe a significant loss of Gαs at the plasma membrane, but no loss from other membrane compartments. After 4 h, Gαs is further depleted from the plasma membrane, and is also less abundant at endosomes. One possible explanation for this is that over time, endosomes either recycle to the plasma membrane or fuse with endosomes bearing active receptors, thus exposing their complement of Gαs to active receptors. In other words, the Gαs that is constitutively located on intracellular membranes is transiently protected from receptor-mediated activation, and would not immediately appear in the soluble fraction.

Recycling of activated Gαs to the plasma membrane has been observed in only one prior study (8), and very little is known about the time course of recycling or the mechanisms involved. Here we show that recycling occurs over the course of 25 min, persists at low temperatures, and is resistant to disruption of microtubules and the Golgi apparatus. These results rule out a role for the classical secretory pathway in the return of activated Gαs to the plasma membrane, and argue against a role for vesicular trafficking in general. It is possible that free Gαs subunits sample all endomembrane compartments and passively redistribute back to the plasma membrane upon deactivation, as is thought to be the case for translocating Gβγ dimers (34). However, the rate at which Gαs recycles to the plasma membrane is 3-fold slower than the rate at which it leaves this compartment, suggesting that different mechanisms are involved in recycling and the initial translocation. It is also possible that the route of Gαs recycling to the plasma membrane is similar to the (still poorly defined) route taken by nascent Gαs during biosynthesis, as the initial delivery of this G protein to the plasma membrane also persists after disruption of the Golgi apparatus (35). Although there is precedent for non-vesicular delivery of palmitoylated proteins to the plasma membrane (36, 37), additional studies will be required to fully determine how Gαs traffics to and from the plasma membrane.

Finally, our results fail to support the hypothesis that internalization of activated Gαs depends on depalmitoylation. Activation of Gαs greatly increases the rate of palmitate turnover on this subunit, suggesting that net depalmitoylation may lead to detachment of Gαs from the plasma membrane (8, 20, 21). Although a great deal of circumstantial evidence supports this hypothesis, it has not been directly tested. We show here that HDFP, a lipid hydrolase inhibitor that decreases constitutive palmitate turnover on Gαs in cells (32), fails to prevent agonist-induced internalization of this subunit. That HDFP induced a redistribution of Gαs in unstimulated cells suggests that the inhibitor was effective and that a constitutive acylation-deacylation cycle is important for steady-state localization of Gαs at the plasma membrane, as is the case for other palmitoylated proteins (33). It is possible that an as yet unidentified HDFP-resistant enzyme is responsible for activity-dependent depalmitoylation and internalization of Gαs. However, it is also possible that the increase in palmitate turnover upon activation is not the primary mechanism of Gαs translocation. This possibility is consistent with a report indicating that activation increases the rate of palmitate turnover on Gαs but does not change the fraction of palmitoylated Gαs (38). This alternative is also supported by our observation that a Gαs mutant that lacks the cysteine necessary for palmitoylation undergoes a similar activity-dependent redistribution from the plasma membrane to intracellular compartments (9), although it is possible that this mutant and wild-type Gαs translocate via different mechanisms. Although not conclusive, our results suggest that a factor other than palmitoylation may dictate the affinity of activated Gαs for the plasma membrane.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK 293 cells (ATCC) were propagated in plastic flasks, on 6-well plates, and on polylysine-coated glass coverslips according to the supplier's protocol. Cells were transiently transfected in growth medium using linear polyethyleneimine (Mr 25,000; Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA) at a nitrogen/phosphate ratio of 20 and were used for experiments 12–48 h later. Up to 3 μg of plasmid DNA was transfected in each well of a 6-well plate.

Plasmid DNA Constructs

Gαs-Rluc8 was made by inserting Rluc8 (amplified from a plasmid provided by Dr. Sanjiv Sam Gambhir, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA) between residues Gly-72 and Asp-85 of the long isoform of human Gαs (from the cDNA Resource Center) with SGGGGS linkers. Gαs-Rluc8 IEK+ was made using an identical strategy, and Gαs IEK+ was provided by Dr. Philip Wedegaertner, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA. Gαs-Rluc8 +myr and Gαs-Rluc8 +myr-palm were made using Gαs-Rluc8 and sequential rounds of QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Unlabeled Gβ1, Gγ2, and β2AR were obtained from the cDNA Resource Center. The BRET acceptor localized to the plasma membrane (Venus-K-Ras) consisted of the final 25 residues of K-Ras (RKHKEKMSKDGKKKKKKSKTKCVIM) fused to the C terminus of Venus. The BRET acceptor localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (Venus-PTP1b) consisted of the last 27 residues of PTP1b (FLVNMCVATVLTAGAYLCYRFLFNSNT) fused to the C terminus of Venus. The BRET acceptor localized to the Golgi apparatus (Venus-giantin) consisted of residues 3131–3259 of giantin fused to the C terminus of Venus. The BRET acceptor localized to the mitochondrial outer membrane (Venus-MoA) consisted of residues 490–527 of human monoamine oxidase A fused to the C terminus of Venus. Plasmids encoding giantin and MoA were provided by Dr. Takanari Inoue (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Acceptors targeted to early, late and recycling endosomes were made by subcloning full-length human Rab5a, Rab7a, and Rab11a into pVenus-C1 (provided by Dr. Stephen Ikeda, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Rockville, MD). All fusion constructs were made using an adaptation of the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis protocol and were verified by automated sequencing.

Confocal Imaging

Confocal images were acquired using a Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) SP8 scanning confocal microscope and a 63×, 1.4 NA objective. Venus was excited with the 488-nm diode laser, and detected at 500–650 nm.

BRET Measurements

Cells were washed with Dulbecco's PBS, harvested by trituration, and transferred to opaque black or white 96-well plates. Fluorescence and luminescence measurements were made using a Mithras LB940 photon-counting plate reader (Berthold Technologies GmbH, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Fluorescence emission was measured at 520–545 nm after excitation at 485 nm. Background fluorescence from untransfected cells was subtracted. For BRET, coelenterazine h (5 μm; Dalton Pharma, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) was added to all wells immediately prior to making measurements. Raw BRET signals were calculated as the emission intensity at 520–545 nm divided by the emission intensity at 475–495 nm. Net BRET was this ratio minus the same ratio measured from cells expressing only the BRET donor. Kinetic experiments (e.g. Fig. 3A) were performed by measuring a BRET ratio once every 6.4 s, and drugs were added using an automated injector and 10× concentrated drug solutions.

Statistical Comparisons

Hypothesis testing was carried out using GraphPad Prism 6.0. A ratio paired t test was used when comparing two groups, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used when comparing more than two groups. Multiple comparison testing was done using Tukey's test when all groups were compared with all other groups, and a Dunnett's test was done when all groups were compared with a single control group.

Author Contributions

N. A. L. conceived the study, performed experiments, analyzed results, and drafted the manuscript. B. R. M. synthesized HDFP and helped revise the manuscript. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Stephen Ikeda, Philip Wedegaertner, Takanari Inoue, and Sanjiv Sam Gambhir, who generously provided plasmids used in this study.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants GM078319 and GM109879 (to N. A. L.) and GM114848 (to B. R. M.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

- APT1

- acyl protein thioesterase 1

- BRET

- bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- β2AR

- β2 adrenergic receptor

- HDFP

- hexadecylfluorophosphonate

- myr

- myristoylated

- palm

- palmitoylated

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- CTX

- cholera toxin.

References

- 1. Gilman A. G. (1987) G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56, 615–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hewavitharana T., and Wedegaertner P. B. (2012) Non-canonical signaling and localizations of heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell. Signal. 24, 25–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slepak V. Z., and Hurley J. B. (2008) Mechanism of light-induced translocation of arrestin and transducin in photoreceptors: interaction-restricted diffusion. IUBMB Life 60, 2–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wedegaertner P. B. (2012) G protein trafficking. Subcell Biochem. 63, 193–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saini D. K., Chisari M., and Gautam N. (2009) Shuttling and translocation of heterotrimeric G proteins and Ras. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 30, 278–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ransnäs L. A., Svoboda P., Jasper J. R., and Insel P. A. (1989) Stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors of S49 lymphoma cells redistributes the α subunit of the stimulatory G protein between cytosol and membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 7900–7903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lynch C. J., Morbach L., Blackmore P. F., and Exton J. H. (1986) α-Subunits of Ns are released from the plasma membrane following cholera toxin activation. FEBS Lett. 200, 333–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wedegaertner P. B., Bourne H. R., and von Zastrow M. (1996) Activation-induced subcellular redistribution of Gsα. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 1225–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thiyagarajan M. M., Bigras E., Van Tol H. H. M., Hébert T. E., Evanko D. S., and Wedegaertner P. B. (2002) Activation-induced subcellular redistribution of Gαs is dependent upon its unique N-terminus. Biochemistry 41, 9470–9484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hynes T. R., Mervine S. M., Yost E. A., Sabo J. L., and Berlot C. H. (2004) Live cell imaging of Gs and the β2-adrenergic receptor demonstrates that both αs and β1γ7 internalize upon stimulation and exhibit similar trafficking patterns that differ from that of the β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44101–44112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Allen J. A., Yu J. Z., Donati R. J., and Rasenick M. M. (2005) β-Adrenergic receptor stimulation promotes Gαs internalization through lipid rafts: a study in living cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 1493–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yu J.-Z., and Rasenick M. M. (2002) Real-time visualization of a fluorescent Gαs: dissociation of the activated G protein from plasma membrane. Mol. Pharmacol. 61, 352–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jalink K., and Moolenaar W. H. (2010) G protein-coupled receptors: the inside story. Bioessays 32, 13–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vilardaga J.-P., Jean-Alphonse F. G., and Gardella T. J. (2014) Endosomal generation of cAMP in GPCR signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 700–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Irannejad R., Tomshine J. C., Tomshine J. R., Chevalier M., Mahoney J. P., Steyaert J., Rasmussen S. G., Sunahara R. K., El-Samad H., Huang B., and von Zastrow M. (2013) Conformational biosensors reveal GPCR signalling from endosomes. Nature 495, 534–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsvetanova N. G., Irannejad R., and von Zastrow M. (2015) GPCR signaling via heterotrimeric G proteins from endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 6689–6696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scarselli M., and Donaldson J. G. (2009) Constitutive internalization of G protein-coupled receptors and G proteins via clathrin-independent endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3577–3585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Linder M. E., Middleton P., Hepler J. R., Taussig R., Gilman A. G., and Mumby S. M. (1993) Lipid modifications of G proteins: α subunits are palmitoylated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 3675–3679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Degtyarev M. Y., Spiegel A. M., and Jones T. L. (1993) The G protein αs subunit incorporates [3H]palmitic acid and mutation of cysteine-3 prevents this modification. Biochemistry 32, 8057–8061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wedegaertner P. B., and Bourne H. R. (1994) Activation and depalmitoylation of Gsα. Cell 77, 1063–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Degtyarev M. Y., Spiegel A. M., and Jones T. L. (1993) Increased palmitoylation of the Gs protein α subunit after activation by the β-adrenergic receptor or cholera toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 23769–23772 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mumby S. M., Kleuss C., and Gilman A. G. (1994) Receptor regulation of G-protein palmitoylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 2800–2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duncan J. A., and Gilman A. G. (1998) A cytoplasmic acyl-protein thioesterase that removes palmitate from G protein α subunits and p21RAS. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15830–15837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lan T.-H., Liu Q., Li C., Wu G., and Lambert N. A. (2012) Sensitive and high resolution localization and tracking of membrane proteins in live cells with BRET. Traffic 13, 1450–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lan T. H., Kuravi S., and Lambert N. A. (2011) Internalization dissociates β2-adrenergic receptors. PLoS ONE 6, e17361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Balla A., Tóth D. J., Soltész-Katona E., Szakadáti G., Erdélyi L. S., Várnai P., and Hunyady L. (2012) Mapping of the localization of type 1 angiotensin receptor in membrane microdomains using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer-based sensors. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 9090–9099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loening A. M., Fenn T. D., Wu A. M., and Gambhir S. S. (2006) Consensus guided mutagenesis of Renilla luciferase yields enhanced stability and light output. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 19, 391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marrari Y., Crouthamel M., Irannejad R., and Wedegaertner P. B. (2007) Assembly and trafficking of heterotrimeric G proteins. Biochemistry 46, 7665–7677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Evanko D. S., Thiyagarajan M. M., and Wedegaertner P. B. (2000) Interaction with Gβγ is required for membrane targeting and palmitoylation of Gαs and Gαq. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1327–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hein P., Rochais F., Hoffmann C., Dorsch S., Nikolaev V. O., Engelhardt S., Berlot C. H., Lohse M. J., and Bünemann M. (2006) Gs activation is time-limiting in initiating receptor-mediated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33345–33351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuismanen E., and Saraste J. (1989) Low temperature-induced transport blocks as tools to manipulate membrane traffic. Methods Cell Biol. 32, 257–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin B. R., Wang C., Adibekian A., Tully S. E., and Cravatt B. F. (2012) Global profiling of dynamic protein palmitoylation. Nat. Methods 9, 84–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rocks O., Peyker A., Kahms M., Verveer P. J., Koerner C., Lumbierres M., Kuhlmann J., Waldmann H., Wittinghofer A., and Bastiaens P. I. H. (2005) An acylation cycle regulates localization and activity of palmitoylated Ras isoforms. Science 307, 1746–1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O'Neill P. R., Karunarathne W. K. A., Kalyanaraman V., Silvius J. R., and Gautam N. (2012) G-protein signaling leverages subunit-dependent membrane affinity to differentially control βγ translocation to intracellular membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E3568–E3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takida S., and Wedegaertner P. B. (2004) Exocytic pathway-independent plasma membrane targeting of heterotrimeric G proteins. FEBS Lett. 567, 209–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zheng H., McKay J., and Buss J. E. (2007) H-Ras does not need COP I- or COP II-dependent vesicular transport to reach the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25760–25768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goodwin J. S., Drake K. R., Rogers C., Wright L., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Philips M. R., and Kenworthy A. K. (2005) Depalmitoylated Ras traffics to and from the Golgi complex via a nonvesicular pathway. J. Cell Biol. 170, 261–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jones T. L., Degtyarev M. Y., and Backlund P. S. (1997) The stoichiometry of Gαs palmitoylation in its basal and activated states. Biochemistry 36, 7185–7191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]