Abstract

The ryanodine receptors (RyRs) are intracellular calcium channels responsible for rapid release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum (SR/ER) to the cytoplasm, which is essential for the excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling of cardiac and skeletal muscles. The near-atomic resolution structure of closed RyR1 revealed the molecular details of this colossal channel, while the long-range allosteric gating mechanism awaits elucidation. Here, we report the cryo-EM structures of rabbit RyR1 in three closed conformations at about 4 Å resolution and an open state at 5.7 Å. Comparison of the closed RyR1 structures shows a breathing motion of the cytoplasmic platform, while the channel domain and its contiguous Central domain remain nearly unchanged. Comparison of the open and closed structures shows a dilation of the S6 tetrahelical bundle at the cytoplasmic gate that leads to channel opening. During the pore opening, the cytoplasmic “O-ring” motif of the channel domain and the U-motif of the Central domain exhibit coupled motion, while the Central domain undergoes domain-wise displacement. These structural analyses provide important insight into the E-C coupling in skeletal muscles and identify the Central domain as the transducer that couples the conformational changes of the cytoplasmic platform to the gating of the central pore.

Keywords: RyR1, calcium channel, excitation-contraction coupling, membrane transport, voltage-gated calcium channels

Introduction

Ryanodine receptors (RyRs) are responsible for rapid release of Ca2+ ions from the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum (SR/ER) to the cytoplasm, a critical step in the excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling of skeletal and cardiac muscles1,2,3,4. There are three RyR isoforms (RyR1-3) in mammals, among which RyR1 is primarily expressed in skeletal muscles, RyR2 mainly functions in cardiac muscles, and RyR3 remains poorly characterized5,6,7,8,9.

The homotetrameric RyRs are the largest known ion channels, with a molecular weight of > 2.2 MDa2,3. Electron microscopic examinations showed that RyR1 has a mushroom-shaped contour with a square canopy of 270 Å by 270 Å and a height of 160 Å10,11,12,13,14. The gigantic cytoplasmic region provides the docking station for a variety of regulators including small molecules, proteins, and post-translational modifications exemplified by phosphorylation15,16. The identified modulators include, but are not limited to Ca2+, caffeine, ATP, ryanodine, 2,2′,3,5′,6-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB95), and FK506-binding proteins (FKBPs)17,18,19,20,21,22. Among these, PCB95 was reported to stabilize the fully open state of RyR1 in single-channel recording and [3H]-ryanodine-binding assay14.

We recently determined the cryo-EM structure of RyR1 in a closed state with an overall resolution of 3.8 Å23. The near-atomic resolution structure resolves 70 % of the 2.2 MDa molecular mass of RyR1 and provides the basis for detailed function-structure correlation analysis. In addition to the channel domain that exhibits a voltage-gated ion channel superfamily fold, nine distinct domains in the cytoplasmic region were identified in each protomer, including the N-terminal domain (NTD), three SPRY domains, the phosphorylation hotspots P1 and P2 domains, the Handle domain, the Helical domain, and the Central domain (Supplementary information, Figure S1A)23. The scaffold of the cytoplasmic region in each protomer comprises two super spirals, one formed by the Helical domain, while the other constituted together by the armadillo repeats (or the α-solenoid repeats) in the NTD, the Handle domain, and the Central domain24. The plasticity of the cytoplasmic super spirals may provide the molecular basis for allosteric gating of the pore domain upon stimuli. This hypothesis was in part supported by comparing the cryo-EM structures of RyR1 captured in multiple conformations25. Nevertheless, the low resolutions prevented reliable definition of the channel state.

Here, we report the cryo-EM structures of closed RyR1 between 3.8–4.2 Å resolutions with the cytoplasmic region exhibiting multiple conformations and an open-state structure at 5.7 Å resolution. Structural comparison reveals important insight into the gating mechanism of RyRs.

Results

“Breathing motion” of the cytoplasmic region of closed RyR1

The RyR1-FKBP12 complex was purified following the previously reported protocol23. To acquire a structure in an open state, we tried distinct conditions for sample preparation. In one trial, the protein purified in the presence of 0.015% (w/v) Tween-20 was incubated with 50 μM CaCl2 and 10 μM PCB95 before loading to the grids for cryo sample preparation. Images were taken on a FEI Tecnai Polara electron microscope operating at 300 kV and mounted with a prototype FEI Falcon-III detector. Out of 334 000 good particles, three major classes were obtained at 3.8 Å, 4.0 Å, and 4.2 Å resolutions (Supplementary information, Figures S1 and S2). The cytoplasmic region of these three classes exhibits gradual shifts (Figure 1A). Unexpectedly, despite the presence of 50 μM Ca2+ and 10 μM PCB95, the central pore remains closed in all three classes (Figure 1B).

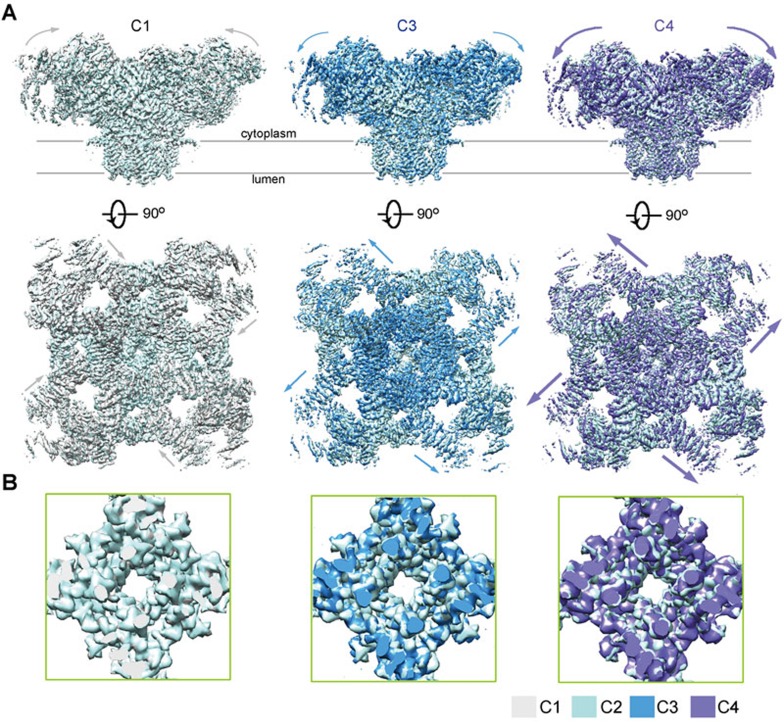

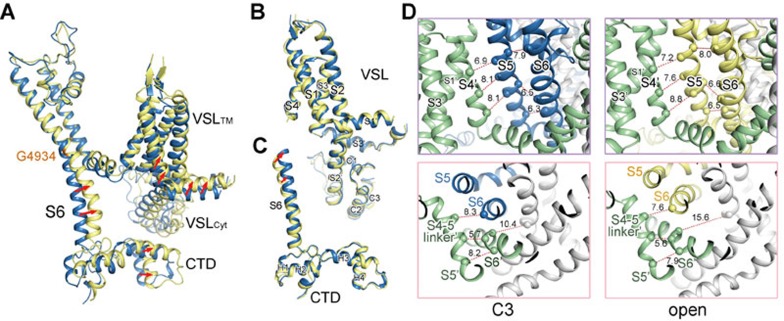

Figure 1.

Cryo-EM structures of RyR1 in three additional closed conformations. (A) Three additional RyR1 structures were obtained. Compared with the previously reported RyR1 structure, the cytoplasmic region of the three new classes undergoes pronounced shifts. The four classes of closed RyR1 are designated C1 through C4, among which C2 is the previously reported one23. Shown here are the superimpositions of the three new structures with the C2 conformer. The arrows indicate the structural shifts from C2 to the indicated conformer. Please refer to Supplementary information, Movie S1 for the conformational transition from C1 to C4. (B) The channel domain remains nearly identical in the four classes. Shown here are the cytoplasmic views of the pore-forming segments. The EM maps were generated in Chimera47.

The three new maps all deviate from the published one in the cytoplasmic region23 (Figure 1A). The cytoplasmic region, particularly the previously defined corona and peripheral zones, in the four conformers displays a consecutive conformational transition (Supplementary information, Movie S1). We name the four conformers C1 through C4, among which C2 is the published one23. From C1 to C4, the corona of the cytoplasmic region moves gradually toward the lumen (Figure 1A). The morph generated based on the conformers C1 and C4 reveals a “breathing motion” of the gigantic cytoplasmic scaffold. We will focus on these two conformers, which display the largest degree of structural shifts, for detailed analysis.

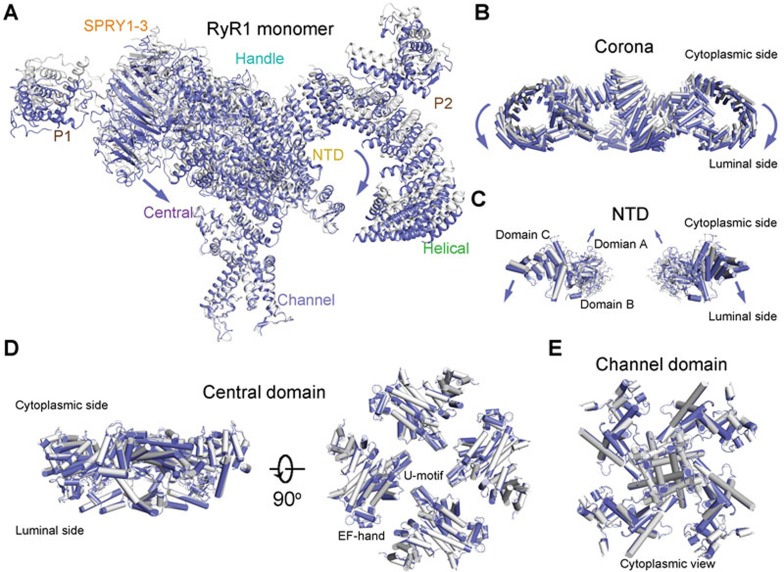

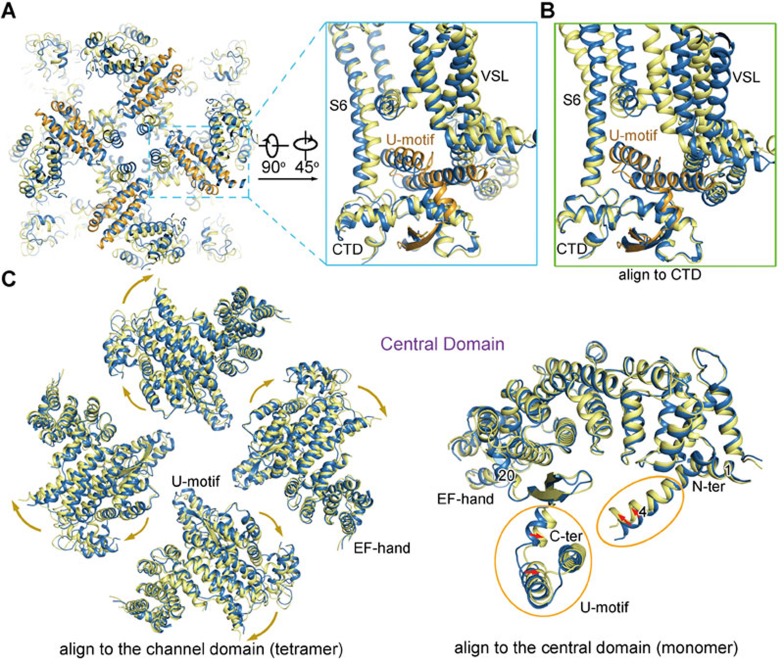

When the structures of C1 and C4 tetramers are superimposed relative to the channel domain, distinct motions of the cytoplasmic domains were observed (Figure 2A). As seen in the morph (Supplementary information, Movie S1), the outskirt of the Handle domain and the Helical domain, which constitute the corona, appears to rock towards the lumen (Figures 2A and 2B). The motion of the NTD is more complex with domains A and B moving upwards, while the armadillo repeats-containing domain C, which immediately precedes the Handle domain in the super spiral, moves concordantly with the shifts of the corona toward the lumen (Figure 2C and Supplementary information, Movie S1). In contrast, the channel domain and Central domain remain nearly unchanged (Figures 2D and 2E). Consequently, the corona and NTD appear to pivot around the Central domain in each protomer (Supplementary information, Movie S1). It is noteworthy that despite the pronounced structural shifts, there is little intra-domain rearrangement when the individual domains in the two structures are compared, suggesting rigid-body shifts of these domains that lead to the overall breathing motion of the cytoplasmic region (Supplementary information, Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Conformational changes of the individual domains between C1 and C4 conformers. (A) Structural comparison between C1 (gray) and C4 (violet) protomers. The two tetrameric structures are superimposed relative to the channel domain. The violet arrows indicate the conformational changes from C1 to C4. The same is applied to the other panels. (B) Structural shifts of the corona between C1 and C4 tetramers. The outskirt of the corona, composed of the Handle and Helical domains, moves towards the SR lumen from C1 to C4. Shown here is a side view. (C) The NTD undergoes a rocking motion with the central domains A and B upwards and the outer domain C downwards. For visual clarity, only two diagonal protomers are shown in side view. (D, E) The Central (D) and channel (E) domains remain nearly unchanged between C1 and C4 states. All structure figures were prepared with PyMol48.

Structural determination of RyR1 in the open state

The structural observation that RyR1 remains closed in the presence of 10 μM PCB95 and 50 μM Ca2+ was unexpected. We reasoned that the choice of detergent may also affect the open probability of the channel. Indeed, it was shown that the highest [3H]-ryanodine-binding affinity was achieved in the presence of CHAPS among the tested detergents, suggesting RyR1 may have a higher open probability when purified in CHAPS2. Therefore, we replaced Tween-20 by CHAPS for purification of the RyR1-FKBP12 complex. After data collection and careful classifications, the complex obtained in 0.5% (w/v) CHAPS, 10 μM PCB95, and 50 μM Ca2+ gave rise to a much higher percentage of particles in the open state. Finally, we were able to reconstruct an EM map, in which the central pore appeared open, with an overall resolution of 5.7 Å (Supplementary information, Figures S1 and S2). Despite that the side chains were not traceable at this moderate resolution, most of the secondary structures can be reliably assigned based on the near-atomic structure of the closed RyR1 (Figure 3A).

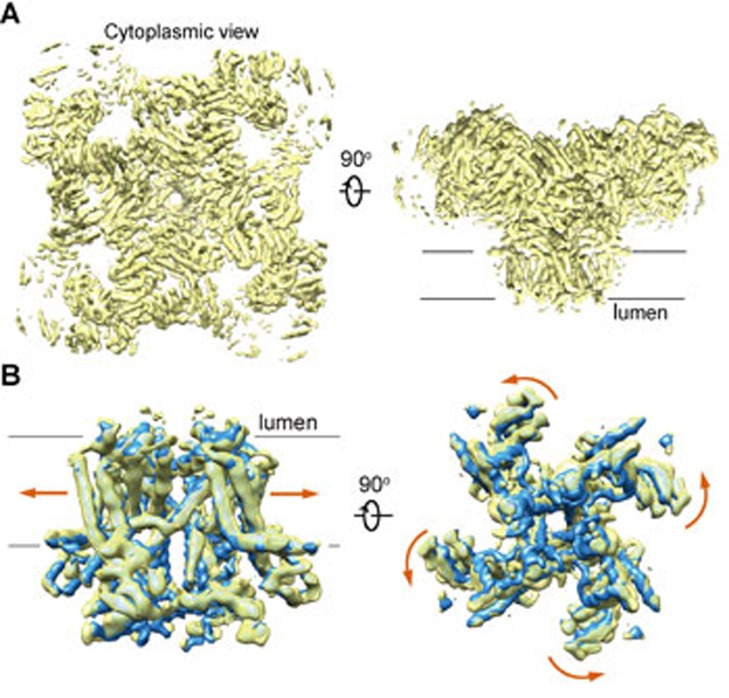

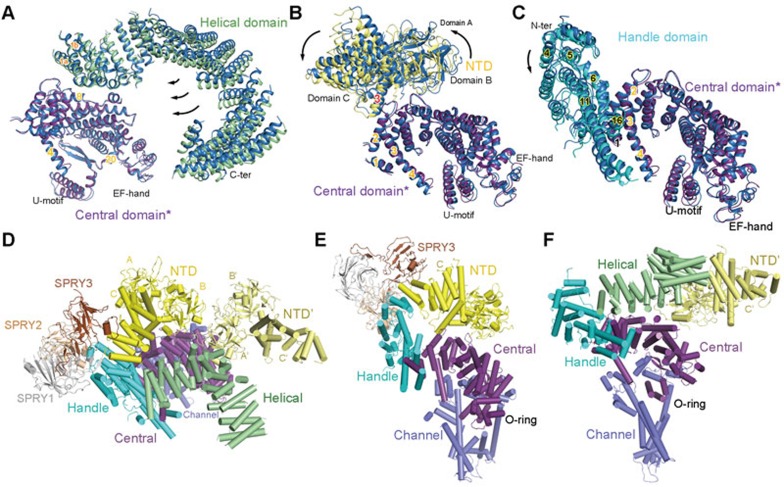

Figure 3.

The cryo-EM reconstruction of an open RyR1. (A) The overall cryo-EM map of the open RyR1 at 5.7 Å resolution. Two perpendicular views are shown. (B) Comparison of the channel domain between the open and the C3 conformers. Shown on the right is the cytoplasmic view. The arrows indicate the conformational change from the C3 (blue) to the open (yellow) state.

Comparing the new map to the four closed RyR1 maps shows that the overall conformation of the cytoplasmic region in the new map closely resembles that of C3 conformer (Supplementary information, Figure S4). To pinpoint the switch for pore opening, we focus on the comparison between the new map and that of the C3 conformer. Similar to the aforementioned comparison between C1 and C4 conformers, when individual domains in the cytoplasmic region are compared, little change is found within the Helical domain, Handle domain and NTD (Supplementary information, Figure S5). In contrast, superimposition of EM maps of the channel domain reveals obvious dilation of the pore, supporting the definition of an open channel (Figure 3B). The channel domain, including the pore-forming S5 and S6 segments and the voltage-sensor like (VSL) domain, undergoes an overall small-degree counterclockwise rotation from the closed to open state when viewed from the cytoplasmic side (Figure 3B).

Cryo-EM structure of the open RyR1

The moderate resolution of the open RyR1 structure disallowed side chain assignment. Nevertheless, the pronounced backbone shifts of S6 segments support the open conformation of the new structure as seen in the EM map (Figure 3B, Supplementary information, Figure S2B). When the structures of the open- and closed (C3)-RyR1 are overlaid relative to the channel domain, the luminal halves including those of S5, S6, the selectivity filter, and P loops, remain nearly unchanged. On the other side, the transmembrane fragment close to the cytoplasm and cytoplasmic extension of the S6 segment (designated the S6Cyt segment hereafter) swing outwards, resulting in the dilation of the intracellular gate (Figure 4A, Supplementary information, Movie S2). The distance between the Cα atoms of the constriction site residue Ile4937 in the diagonal protomers increases from 10.4 Å to 15.6 Å (Figure 4B). The calculated pore diameter of the constriction site in the high-resolution closed RyR1 was ∼1.6 Å, blocking Ca2+ passage. Now that the diameter is expanded by ∼5 Å, it would allow permeation of single-file Ca2+ even with hydration shell (Supplementary information, Movie S2).

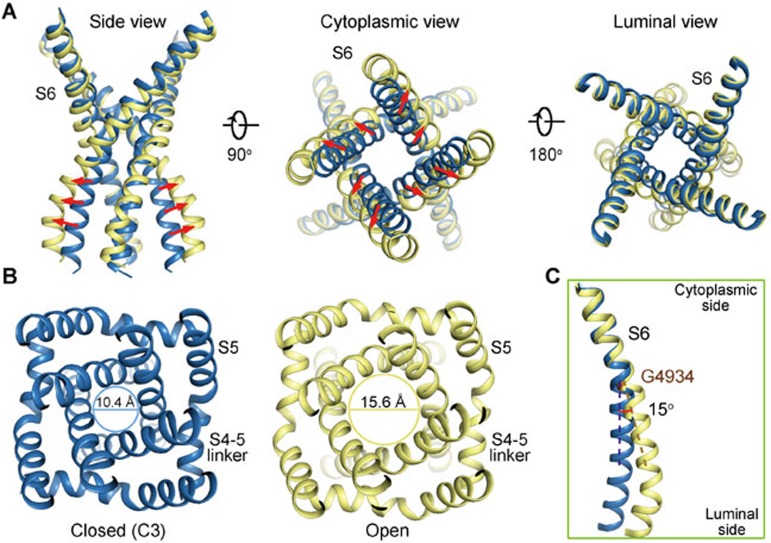

Figure 4.

Dilation of the inner gate leads to channel opening. (A) The cytoplasmic gate of the S6 bundle undergoes a dilation that leads to pore opening, while the luminal segments have little change. (B) Dilation of the cytoplasmic gate. The indicated distances are measured between the Cα atoms of the gating residue Ile4937 on the S6 segments in the diagonal protomers. Please refer to Supplementary information, Movie S2 for the conformational changes of the channel domain. (C) Comparison of the S6 segment relative to the luminal halves of the pore-forming segments (residues 4 836-4 935) shows that the structural deviation between the open (yellow) and closed (blue) states occurs at Gly4934.

To identify the deviation point of the S6 segments, the two structures are superimposed relative to the selectivity filter (SF) and the supporting helices (residues 4 836 to 4 935; Figure 4C). An ∼15° bending of S6 helix occurs at a conserved Gly residue (Gly4934 in RyR1; Figure 4C). The structural observation supports a recent characterization that substitution of Gly4934 led to altered channel gating and ion conductance. Gly may provide the molecular basis for conformational flexibility26.

Coupled conformational changes of the cytoplasmic O-ring of the channel domain

As analyzed previously, the S6Cyt segment, CTD, and the cytoplasmic segments of the VSL domain (designated the VSLCyt domain) together constitute an O-ring (Figure 5A). When the channel domains in the structures of the open and C3 states are superimposed relative to the SF and the supporting helices, the elements in the cytoplasmic O-ring appear to undergo concordant shift (Figures 3B and 5A). Comparison of the individual domains shows little intra-domain rearrangement within the VSL or CTD domain (Figures 5B and 5C). In addition, there is no relative motion between the CTD and the C-terminal segment of S6, supporting our previous finding that the presence of a zinc-finger motif at the joint of CTD and S6 may rigidify the two structural moieties23 (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Coupled conformational shifts of the segments within the channel domain during pore opening. (A) Structural comparison of the channel domain in one protomer between the open and C3 structures relative to the luminal halves of the pore-forming segments (residues 4 836-4 935). The cytoplasmic “O-ring” composed of the cytoplasmic segments of S6 (S6Cyt), the VSLCyt, and the CTD appears to undergo concordant shifts. (B) The VSL appears rigid during pore opening. There is no intra-domain rearrangement observed between the VSL domain in the open and closed structures. Therefore, the VSL domain undergoes a rigid-body shift during pore opening. (C) There is no relative motion between CTD and the S6Cyt segment during the pore dilation. (D) The concerted motions between the S5 and S6 segments in the same protomer, and between the S5 segment and the S4 and S4-5 segments in the neighbouring protomers. The distances between the Cα atoms of the indicated residues are presented in Å. For visual clarity, the specified protomer is coloured blue and yellow in the closed and open states, respectively, while the neighbouring protomer is coloured green in both states. The other two protomers that are not discussed are coloured gray. Please refer to Supplementary information, Movie S3 for the concordant shifts of the channel segments during pore dilation.

The extensive interactions between the S5 and S6 segments within one protomer and those between the VSL and the pore-forming segments in the neighbouring protomer were analyzed in details in our previous report23. We predicted that these extensive interactions may provide the molecular basis for coupled conformational changes. Indeed, comparison of the open and C3 structures shows that these elements undergo coupled motion during pore opening (Figure 5D, Supplementary information, Movie S3). For instance, the inter-helical distances between S4 in one protomer and S5 in the adjacent protomer in the C3 structure are similar to those in the open structure (Figure 5D, upper panels). Similarly, the distances between the Cα atoms of Ile4826 on the S4-5 segment and Ile4931 on the S6 segment in the neighbouring protomers and between Val4830 on S4-5 and Ile4936 on S6 in the same protomer also remain nearly the same in the open and C3 structures (Figure 5D, lower panel; Supplementary information, Movie S3).

The structural observations suggest that shifts of VSL and CTD may pull the S6 segments as well as the constraining S4-5 segments outwards to open the intracellular gate.

Coupled conformational changes between the cytoplasmic O-ring of the channel domain and the U-motif of the Central domain

As shown previously, the cytoplasmic O-ring of the channel domain accommodates the U-motif in the Central domain. The helical hairpin of the U-motif pierces through the O-ring, whereas the anti-parallel β-strands are located at the concave surface below the O-ring (Figure 6A). The intricate interactions between the U-motif and the O-ring tie them into a stable unit. Indeed, the U-motif moves together with the O-ring during pore opening (Figure 6A). When the open and C3 structures are superimposed relative to CTD, the U-motif can be almost completely overlaid, indicating coupled motion between the CTD and the U-motif (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Coupled conformational changes between the channel domain and the Central domain. (A) Concordant conformational changes between the cytoplasmic “O-ring” of the channel domain and the U-motif of the Central domain. Shown here are the luminal and side views of the U-motif and the O-ring. The U-motif in the open RyR1 is coloured orange. Please refer to Supplementary information, Movie S4 for the concerted conformational changes. (B) Structural comparison of the O-ring and the U-motif between the C3 conformer and the open structure relative to CTD. There is little shift of the U-motif relative to CTD. (C) Comparison of the Central domain between the open and the C3 structures relative to the tetrameric channel domain (left panel) and relative to the individual Central domain (right panel). The tetrameric Central domain is shown in cytoplasmic view. The yellow and green arrows indicate the conformational transition from C3 to the open state.

The above analysis is based on the structure deviation between the open- and closed-RyR1 structures. In terms of gating, the channel is pulled-open by signals applied to the cytoplasmic region. Therefore, it is likely that the displacement of U-motif mobilizes the O-ring, leading to the dilation of the S6 segments. We next analyzed the conformational changes of the cytoplasmic domains that may lead to the U-motif shift.

The Central domain undergoes a slight outward displacement from the closed to open conformation when viewed from the SR lumen (Figure 6C). Within the Central domain, the U-motif and the nearby helix α20, as well as the extruding helix α4, slightly squeeze toward the center of the concave side of the armadillo repeats, but there is little rearrangement of the armadillo repeats (Figure 6C, right panel). The domainwise shift and the intra-domain rearrangements of the Central domain likely provide the pulling-force for the channel domain. We then examined the potential effect of the corona and peripheral domains on the structural changes of the Central domain.

Lateral rotation of the Central domain triggered by structural shifts of the NTD, Handle and Helical domains

To understand the potential action of other cytoplasmic domains on the Central domain, we compared them pairwise between the open and C3 structures (Figures 7A–7C, Supplementary information, Movie S4). When the Central and Helical domains are compared relative with the Central domain, the superspiral of the Helical domain appears to rotate around the interface between the two domains involving the amino terminal concave surface of the Central domain and the amino terminal helices α1a and α1b in the Helical domain (Figure 7A). Similarly, the NTD also slightly revolves around the interface with the Central domain, but to the opposite direction of the rotation of the Helical domain relative to the Central domain (Figure 7B). As the Handle domain and the armadillo repeats of the NTD are consecutive, it is not surprising that the rotation of the Handle domain is consistent with that of the NTD, i.e., centering around the interface with the Central domain (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

The extensive interaction network among the cytoplasmic domains provide the molecular basis for long-range allosteric gating. (A-C) The motions of the Helical domain, NTD, and Handle domain relative to the Central domain between the closed and open structures. The comparison is made relative to the Central domain (labeled with asterisk). In all panels, domains in C3 are blue, while those in the open structure are domain-coloured. (D) Extensive interfaces among the armadillo repeats-containing cytoplasmic domains, including the NTD, Helical, Handle, and Central domains. The NTD from the neighbouring protomer is also shown, coloured pale yellow and labeled NTD'. (E) The extensive internal interactions within one cytoplasmic superhelical assembly consisting of the armadillo repeats in NTD, the Handle domain, and the Central domain. Note that the Central domain also interacts with the NTD. (F) The extensive interaction network involving the Helical domain, the Handle domain, the Central domain in one protomer and the NTD in the adjacent protomer. Please refer to our previous publication23 for detailed analysis of the cytoplasmic interaction network.

In our previous analysis of the 3.8 Å structure of closed RyR1, we paid particular attention to the interaction network among the super spiral assemblies in the cytoplasmic region. Basically, all the armadillo repeats-containing domains contact each other (Figures 7D–7F). They together constitute a network of pronounced plasticity, which can transduce the conformational changes initiated to any point of the helical surface. The collective motions of the Helical domain, the NTD, and the Handle domain may lead to the observed compression of the Central domain toward its concave side (Figure 6C, right panel). In addition to the internal rearrangement of the Central domain, an overall concerted lateral rotation of the Central and the other cytoplasmic domains occur between the open and closed states when viewed from the side (Supplementary information, Movie S4).

Discussion

In this study, we report the structures of RyR1 in three closed states and an open state. It is particularly interesting when the conformational changes among the closed structures and between the closed and open structures are compared (Supplementary information, Movies S1 and S4). It is evident that the corona, peripheral domains, and NTD of the cytoplasmic region undergo vertical motions during the conformational changes between the distinct closed states (Supplementary information, Movie S1). In contrast, despite the overall similarity between the open and C3 structures, the lateral rotation of the cytoplasmic domains is evident (Supplementary information, Movie S4).

As illustrated above, the pore opening requires dilation of the S6 helical bundle at the intracellular gate (Figure 4). The shift of S6 is triggered by the motion of VSLCyt and CTD (Figure 5), which is induced by the displacement of the U-motif in the Central domain (Figure 6). The shift of the U-motif results from both intra-domain rearrangement and overall lateral rotation of the Central domain. In essence, the pore opening requires mobilization of the Central domain, which thereby serves as the transducer of the long-range conformational changes.

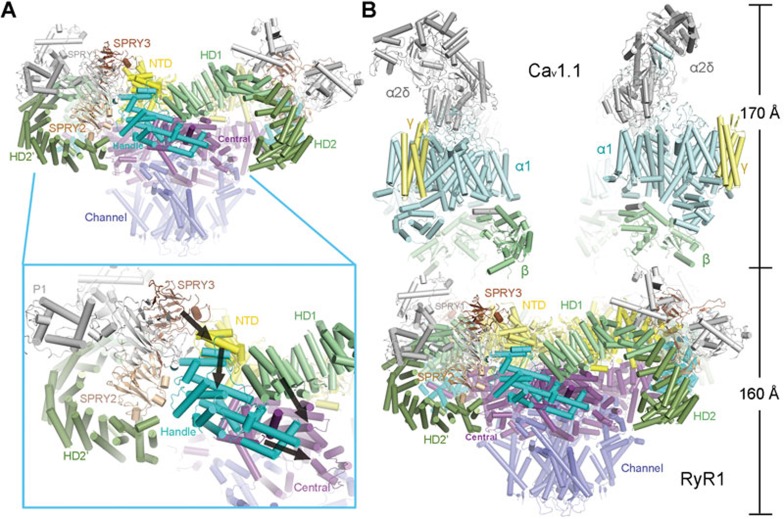

Under physiological condition, RyR1 is activated through direct physical contacts with the Cav1.1 complex as well as the surrounding RyR1 tetramers in the crystalline-like assembly27,28,29,30,31,32. It was shown that multiple areas of the RyR1 cytoplasmic region, such as the SPRY3 domain, are involved in the coupling with Cav1.1 complex (Figure 8A)33. Note that the SPRY3 domain is in direct contact with NTD. Potential shifts of the SPRY3 domain may be translated to the conformational changes of NTD, and subsequently the Handle domain and the Central domain. We speculate that the shift of SPRY3 may involve a displacement to trigger the lateral rotation of the cytoplasmic domains of RyR1 (Figure 8A, inset).

Figure 8.

Speculative mechanism of the excitation-contraction coupling. (A) Conformational changes to any cytoplasmic domain may be propagated to the Central domain along the interaction network described in Figure 7. Shown here are side views of tetrameric RyR1. Inset: an example of a speculative route (black arrows) for the propagation of conformational changes that can be triggered by motion of the SPRY3 domain. (B) Speculative model of the complex between RyR1 and the Cav1.1 complex. Structural determination of both RyR1 and the Cav1.1 complex provides the foundation for elucidating the molecular mechanism of RyR1 opening induced by depolarization of the plasma membrane. Structures of the Cav1.1 complex (PDB code: 3JBR)34 and RyR1 were manually docked in COOT43.

Although the elements in the Cav1.1 complex that bind to RyR1 remain to be elucidated, the recent structural determination of the Cav1.1 complex laid out the foundation for investigation of the gating mechanism of RyR1 (Figure 8B)34. Structures of the complex between Cav1.1 and RyR1 as well as the structures of Cav1.1 in multiple states would offer the answer to address the fundamental problem of how depolarization of the plasma membrane would induce the pore opening of RyR1, which resides in the SR membrane. We speculate that the conformational changes of the voltage-sensing domains of Cav1.1α1 upon depolarization would induce shifts of the β-subunit and other cytoplasmic segments of Cav1.1, which may trigger the motion of the adjoining RyR1 cytoplasmic domains exemplified by the SPRY3 domain. The structural shifts at the periphery of the RyR1 cytoplasmic region are propagated along the superhelical assemblies of the cytoplasmic domains to the Central domain, eventually leading to the opening of the intracellular gate. The speculative mechanism awaits experimental evidence. In addition, high resolution structures of RyR channels in various states are required to reveal the modulation of the channel activity by multiple signals such as Ca2+ and PCB95.

Materials and Methods

Protein purification

The RyR1-FKBP12 complex that was captured in multiple closed conformations was purified following similar protocol as before with slight modifications23. The buffer for the last step size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex-200, 10/30, GE Healthcare) purification was changed to 20 mM MOPS-Na, pH 7.4, 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 0.015% Tween-20 (w/v; Sigma-Aldrich) and protease inhibitor cocktail including 2 mM PMSF, 2.6 μg/ml aprotinin, 1.4 μg/ml pepstatin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin (Amresco). The fractions containing RyR1-FKBP12 complex were pooled for EM analysis. Before loading to grids for cryo sample preparation, the complex was incubated with 50 μM CaCl2 and 10 μM PCB95 for 30 min on ice. The sample that gave rise to the open structure was purified with 0.5% CHAPS (w/v; Amresco) instead of Tween-20. The other procedures were the same.

Cryo-EM image acquisition

Aliquots of 3 μl purified RYR1 at a concentration of ∼30 nM were placed on glow-discharged holey carbon grids (Quantifoil Cu, R2/2), on which a home-made continuous carbon film (estimated to be ∼30 Å thick) had previously been deposited. Grids were blotted for 2 s and flash-frozen in liquid ethane using an FEI Vitrobot II. Grids were transferred to an FEI Tecnai Polara electron microscope that was operating at 300 kV. Images were recorded manually using a prototype FEI Falcon-III detector at a calibrated magnification of 104 478, yielding a pixel size of 1.34 Å. A dose rate of 20 electrons/Å2/s, and an exposure time of 2 s were used on the Falcon.

Image processing

Similar image processing procedures were employed as reported23. We used MOTIONCORR35 for whole-frame motion correction, CTFFIND336 for estimation of the contrast transfer function parameters, and RELION-1.437 for all subsequent steps. References for template-based particle picking38 were obtained from 2D class averages that were calculated from a manually picked subset of the micrographs. A 20 Å low-pass filter was applied to these templates to limit model bias. To discard false positives from the picking, we used initial runs of 2D and 3D classification to remove bad particles from the data. The selected particles were then submitted to 3D auto-refinement, particle-based motion correction and radiation-damage weighting38. The resulting “polished particles” were used for masked classification only on pore region with subtraction of the residual signal35, and the original particle images from the resulting classes were submitted to a second round of 3D auto-refinement. All 3D classifications and 3D refinements were started from a 40 Å low-pass filtered version of the high-resolution consensus structure. Fourier Shell Coefficient (FSC) curves were corrected for the effects of a soft mask on the FSC curve using high-resolution noise substitution39. Reported resolutions are based on gold-standard refinement procedures and the corresponding FSC = 0.143 criterion40. Prior to visualization, all density maps were corrected for the modulation transfer function of the detector, and then sharpened by applying a negative B-factor that was estimated using automated procedures41.

For the sample purified in TWEEN-20/PCB95/Ca2+, 334K particles were selected after initial 2D and 3D classification. Subsequent 3D auto-refinement and particle polishing yielded a map with relatively fuzzy densities in the cytoplasmic region. 3D classification into five classes with small angular sampling yielded three classes with better density of the cytoplasmic region. Relatively poor reconstructed density was observed in the other two classes. Separate 3D auto-refinements of the corresponding particles in the original data set for the three best classes gave rise to reconstructions to 3.8–4.2 Å resolution (also see Supplementary information, Figure S1 and Table S1).

For the sample purified in CHAPS/PCB95/Ca2+, initial classification selected 46K particles. After particle polishing, application of the masked classification procedure on the pore region with residual signal subtraction into three classes identified a single class with good density and open conformation. After 3D auto-refinement, the corresponding 30K particles gave a map with a resolution of 5.7 Å.

Model building and refinement

The initial model (PDB: 3J8H) was docked into each map by using DireX42. The resulting models were manually adjusted in COOT43 to further improve the fitting of secondary structures and side chains. Subsequently, all models were refined using REFMAC44 with secondary structure restraints generated by ProSMART45. To prevent overfitting, the optimal weight for refinement in REFMAC were determined by cross-validation46.

Accession codes

The atomic coordinates of the C1, C3, C4, and open-RyR1 structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the accession codes 5GKY, 5GKZ, 5GL0, and 5GL1, respectively. The cryo-EM maps have been deposited to EMDB with the following accession codes: EMD-9518 (C1), EMD-9519 (C3), EMD-9520 (C4), and EMD-9521 (open state).

Author Contributions

NY conceived the project. ZY, XB, JW, and NY designed experiments. XB, ZY, JW, and ZL performed experiments. All authors analyzed the data and contributed to manuscript preparation. NY and ZY wrote the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Tsinghua University Branch of China National Center for Protein Sciences (Beijing) for providing the facility support. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2015CB9101012014 and ZX09507003006), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31321062 and 81590761). The research of Nieng Yan was supported in part by an International Early Career Scientist grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an endowed professorship from Bayer Healthcare.

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Image processing and resolution estimation.

3D classification scheme.

Structural superimposition of cytoplasmic domains between C1 (gray) and C4 (violet).

Map comparison of the open RyR1 with the four closed conformers.

Structural comparison of the cytoplasmic domains between the open (yellow) and the C3 (dark blue)-state RyR1.

Relative motion among the armadillo repeats-containing domains between the C1 and C4 conformers.

Conformational changes between C1 and C4. The Morph illustrates the structure shifts from C1 to C4. The cytoplasmic regions undergo overall breathing motions while the channel domain and the Central domain remain nearly unchanged. All the intermediate morphs shown here and in other movies were generated using CNS2. All movies were made by PyMol. 2 Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR system. Nature protocols 2007; 2:2728–2733.

Conformational changes of the channel domain between the closed and open RyR1. The morph illustrates the conformational changes of the channel domain between the C3 closed and open states. The inter-helical distances of the S6 segments in the diagonal protomer at the intracellular gate are shown.

Coupled conformational changes within the channel domain. This animation illustrates the concerted motion among the S4-5 linker, the S5 and S6 segments in one protomer and the S4 segment from the neighboring protomer.

Conformational changes between the closes and open RyR1. The morph illustrates the overall conformational changes between the closed (C3) and open structures of RyR1. In contrast to the conformational changes shown in Supplementary information, Movie S1, both the channel and Central domains undergo intra-domain rearrangements during pore opening. In addition, the Central domains undergo a domain-wise lateral rotation between the open and closed states.

Data collection and model statistics

References

- Pessah IN, Waterhouse AL, Casida JE. The calcium-ryanodine receptor complex of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1985; 128:449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui M, Saito A, Fleischer S. Purification of the ryanodine receptor and identity with feet structures of junctional terminal cisternae of sarcoplasmic reticulum from fast skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 1987; 262:1740–1747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai FA, Erickson HP, Rousseau E, Liu QY, Meissner G. Purification and reconstitution of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle. Nature 1988; 331:315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, Hamilton SL. Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010; 2:a003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima H, Nishimura S, Matsumoto T, et al. Primary structure and expression from complementary DNA of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Nature 1989; 339:439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Sorrentino V. Molecular genetics of ryanodine receptors Ca2+-release channels. Cell Calcium 2002; 32:307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu K, Willard HF, Khanna VK, Zorzato F, Green NM, MacLennan DH. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) of rabbit cardiac muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 1990; 265:13472–13483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai J, Imagawa T, Hakamat Y, Shigekawa M, Takeshima H, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression from cDNA of the cardiac ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel. FEBS Lett 1990; 271:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakamata Y, Nakai J, Takeshima H, Imoto K. Primary structure and distribution of a novel ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel from rabbit brain. FEBS Lett 1992; 312:229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radermacher M, Wagenknecht T, Grassucci R, et al. Cryo-EM of the native structure of the calcium release channel/ryanodine receptor from sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biophys J 1992; 61:936–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radermacher M, Rao V, Grassucci R, et al. Cryo-electron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction of the calcium release channel/ryanodine receptor from skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol 1994; 127:411–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samso M, Wagenknecht T, Allen PD. Internal structure and visualization of transmembrane domains of the RyR1 calcium release channel by cryo-EM. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005; 12:539–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serysheva, II, Ludtke SJ, Baker ML, et al. Subnanometer-resolution electron cryomicroscopy-based domain models for the cytoplasmic region of skeletal muscle RyR channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105:9610–9615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samso M, Feng W, Pessah IN, Allen PD. Coordinated movement of cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of RyR1 upon gating. PLoS Biol 2009; 7:e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez P, Bhogal MS, Colyer J. Stoichiometric phosphorylation of cardiac ryanodine receptor on serine 2809 by calmodulin-dependent kinase II and protein kinase A. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:38593–38600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens XH, Lehnart SE, Reiken SR, Marks AR. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ Res 2004; 94:e61–e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalk R, Lehnart SE, Marks AR. Modulation of the ryanodine receptor and intracellular calcium. Annu Rev Biochem 2007; 76:367–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Petegem F. Ryanodine receptors: structure and function. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:31624–31632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G, Rios E, Tripathy A, Pasek DA. Regulation of skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) by Ca2+ and monovalent cations and anions. J Biol Chem 1997; 272:1628–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver DR, Lenz GK, Lamb GD. Regulation of the calcium release channel from rabbit skeletal muscle by the nucleotides ATP, AMP, IMP and adenosine. J Physiol 2001; 537:763–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew SG, Wolleben C, Siegl P, Inui M, Fleischer S. Positive cooperativity of ryanodine binding to the calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum from heart and skeletal muscle. Biochemistry 1989; 28:1686–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelu MG, Danila CI, Gilman CP, Hamilton SL. Regulation of ryanodine receptors by FK506 binding proteins. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2004; 14:227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Bai XC, Yan C, et al. Structure of the rabbit ryanodine receptor RyR1 at near-atomic resolution. Nature 2015; 517:50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari R, Bailes E, Bunting KA, Coates JC. Armadillo-repeat protein functions: questions for little creatures. Trends Cell Biol 2010; 20:470–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efremov RG, Leitner A, Aebersold R, Raunser S. Architecture and conformational switch mechanism of the ryanodine receptor. Nature 2015; 517:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Y, Xu L, Mowrey DD, et al. Channel gating dependence on pore lining helix glycine residues in skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem 2015; 290:17535–17545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios E, Brum G. Involvement of dihydropyridine receptors in excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Nature 1987; 325:717–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe T, Beam KG, Adams BA, Niidome T, Numa S. Regions of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor critical for excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 1990; 346:567–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F, Ramesh V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca(2+) release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophys J 1999; 77:1528–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protasi F, Franzini-Armstrong C, Flucher BE. Coordinated incorporation of skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptors and ryanodine receptors in peripheral couplings of BC3H1 cells. J Cell Biol 1997; 137:859–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protasi F, Franzini-Armstrong C, Allen PD. Role of ryanodine receptors in the assembly of calcium release units in skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol 1998; 140:831–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin CC, D'Cruz LG, Lai FA. Ryanodine receptor arrays: not just a pretty pattern? Trends Cell Biol 2008; 18:149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CF, Mukherjee S, Allen PD. Amino acids 1–1,680 of ryanodine receptor type 1 hold critical determinants of skeletal type for excitation-contraction coupling. Role of divergence domain D2. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:39644–39652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Yan Z, Li Z, et al. Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel Cav1.1 complex. Science 2015; 350:aad2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai XC, Rajendra E, Yang G, Shi Y, Scheres SH. Sampling the conformational space of the catalytic subunit of human gamma-secretase. elife 2015; 4:e11182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Grigorieff N. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 2003; 142:334–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres SH. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol 2012; 180:519–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres SH. Semi-automated selection of cryo-EM particles in RELION-1.3. J Struct Biol 2015; 189:114–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, McMullan G, Faruqi AR, et al. High-resolution noise substitution to measure overfitting and validate resolution in 3D structure determination by single particle electron cryomicroscopy. Ultramicroscopy 2013; 135:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres SH, Chen S. Prevention of overfitting in cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods 2012; 9:853–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal PB, Henderson R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J Mol Biol 2003; 333:721–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Schroder GF. Real-space refinement with DireX: from global fitting to side-chain improvements. Biopolymers 2012; 97:687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2010; 66:486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 1997; 53:240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls RA, Fischer M, McNicholas S, Murshudov GN. Conformation-independent structural comparison of macromolecules with ProSMART. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2014; 70:2487–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez IS, Bai XC, Murshudov G, Scheres SH, Ramakrishnan V. Initiation of translation by cricket paralysis virus IRES requires its translocation in the ribosome. Cell 2014; 157:823–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, et al. UCSF chimera- -a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 2004; 25:1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System on World Wide Web http://www.pymol.org 2002

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Image processing and resolution estimation.

3D classification scheme.

Structural superimposition of cytoplasmic domains between C1 (gray) and C4 (violet).

Map comparison of the open RyR1 with the four closed conformers.

Structural comparison of the cytoplasmic domains between the open (yellow) and the C3 (dark blue)-state RyR1.

Relative motion among the armadillo repeats-containing domains between the C1 and C4 conformers.

Conformational changes between C1 and C4. The Morph illustrates the structure shifts from C1 to C4. The cytoplasmic regions undergo overall breathing motions while the channel domain and the Central domain remain nearly unchanged. All the intermediate morphs shown here and in other movies were generated using CNS2. All movies were made by PyMol. 2 Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR system. Nature protocols 2007; 2:2728–2733.

Conformational changes of the channel domain between the closed and open RyR1. The morph illustrates the conformational changes of the channel domain between the C3 closed and open states. The inter-helical distances of the S6 segments in the diagonal protomer at the intracellular gate are shown.

Coupled conformational changes within the channel domain. This animation illustrates the concerted motion among the S4-5 linker, the S5 and S6 segments in one protomer and the S4 segment from the neighboring protomer.

Conformational changes between the closes and open RyR1. The morph illustrates the overall conformational changes between the closed (C3) and open structures of RyR1. In contrast to the conformational changes shown in Supplementary information, Movie S1, both the channel and Central domains undergo intra-domain rearrangements during pore opening. In addition, the Central domains undergo a domain-wise lateral rotation between the open and closed states.

Data collection and model statistics