Introduction

Sarcoidosis has been comprehensively defined by Scadding and Mitchell as an idiopathic multisystem disease characterised by formation of non caseating epithelioid cell tubercles in affected tissues or organs [1]. The disease process is generalised, manifestations protean and course unpredictable. Between 20-35% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis have cutaneous manifestations, but cutaneous sarcoidosis can also occur without systemic disease in about 25% of cases [2]. It is more common in developed countries and uncommon in our country.

We present two cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis with no systemic manifestations.

Case No 1

A 43 year old male presented with an insidious onset of a gradually progressive, mildly pruritic, red plaque over his nose of six months duration. He also had blurring of vision in both eyes that predated his cutaneous symptoms by a few years. There was no history of trauma, nose bleeds or other systemic symptoms. General physical and systemic examination was normal. Dermatological examination revealed a solitary, sharply marginated, smooth, non tender, fleshy, erythematous plaque with prominent follicular openings and normal sensations, measuring 7 × 5 cm in size, over the nose (Fig 1). Ophthalmologic examination revealed normal left eye and healed Eales disease of the right eye. Nasal examination revealed no ulceration or septal perforation.

Fig 1.

Lupus pernio on the nose before treatment

Case No 2

A 40 year old female reported with two, asymptomatic red patches over her left eyebrow and left cheek of nine years duration. There were no systemic or constitutional symptoms. General physical and systemic examination was normal. Dermatological examination revealed two well defined, non tender, smooth, erythematous plaques with normal sensation above the left eye brow and on left cheek measuring 1 × 2 cm and 3 × 4 cm in size respectively. The surface showed prominent follicular plugging, telengiectasias and mild scaling (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Angiolupoid sarcoidosis on the temple

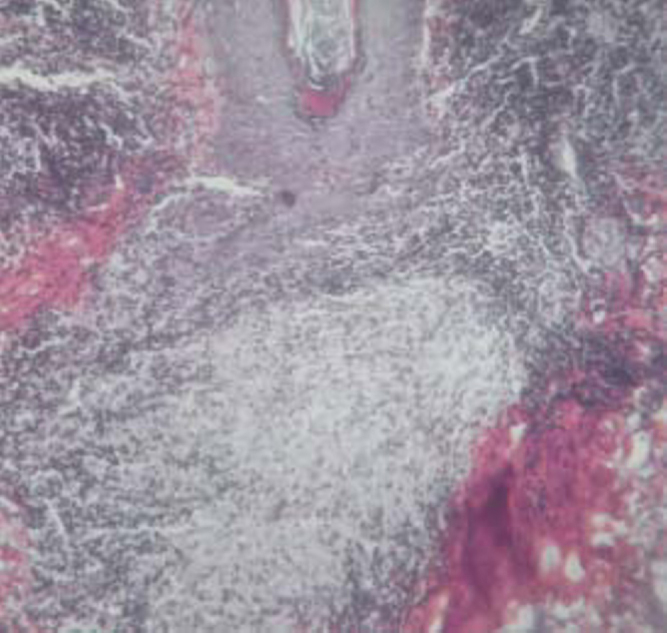

In both the cases, haematological and biochemical investigations including serum calcium were normal, mantoux test was negative, radiograph of chest and pulmonary function tests were normal. Histopathology of the lesion revealed discrete, well defined non caseating epithelioid cell granulomas with mild lymphoid infiltrate scattered throughout the dermis (Fig 3). Reticulin stain revealed reticulin fibres in and around the granulomas. No acid fast bacilli or fungal elements were seen. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme (SACE) levels were 60 IU/ml in the first case and 82 IU/ml in the second case (normal range 18-67 IU/ml).

Fig 3.

Sarcoidal granuloma (H & E stain × 100)

A diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (lupus pernio) was made in the first case. The patient was given topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream and oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. Oral prednisolone was commenced in the dose of 30 mg daily for 4 weeks and tapered gradually to the present dose of 15 mg on alternate days. Within ten months, the induration and erythema of the lesion regressed substantially (Fig 4). The second case was diagnosed as cutaneous sarcoidosis (angiolupoid). The patient was given topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream and oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. There was complete regression of the lesions within six months. Both the cases are under regular follow up.

Fig 4.

Lupus pernio on the nose after treatment

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is the result of an immune dysfunction due to a persistent antigen of low virulence that is poorly cleared by the immune system. Cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis are classified into non specific and specific types. Non specific manifestations present as erythema nodosum, erythema multiformae, calcinosis cutis or nummular eczema. Specific types are classified as maculopapular, papular (lichenoid), nodular (annular, angiolupoid, subcutaneous), plaque (lupus pernio) and erythematous types depending on the type and extent of involvement of the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Unusual and atypical forms viz atrophic, ichthyosiform, erythrodermic, ulcerated, verrucose, etc. are also known to occur [3].

Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis is most often in the form of uveitis. Eales disease is an idiopathic obliterative vasculopathy usually involving the peripheral retina and is not a manifestation of sarcoidosis [1]. Its occurrence in first case is purely coincidental.

Sarcoidosis needs to be distinguished histopathologically from lupus vulgaris and leprosy as they all have epithelioid cell granulomas. While the granulomas in lupus vulgaris are caseous and present in the upper dermis, those in leprosy are mainly around dermal nerve twigs and admixed with abundant lymphocytic infiltration. In contrast, sarcoidal granulomas are discrete, distributed uniformly in the dermis and surrounded by sparse lymphocyte cuffing (‘naked tubercles’), with fine reticulin fibers in and around the tubercles [4].

SACE is derived from epithelioid cells of the granulomas and reflects the granuloma load in the patient. SACE levels are neither diagnostic nor predictors of systemic involvement. It is elevated in approximately 60% of patients and is useful in monitoring the clinical course of the disease [5]. Gallium-67 scintigraphy is a sensitive method to demonstrate systemic involvement as it is rapidly taken up by the cutaneous lesions, salivary glands, lacrimal glands and intrathoracic lymph nodes [6]. However this facility may not be available everywhere and the test is expensive to perform.

Though numerous modalities of treatment are mentioned in literature, no consistently effective treatment of sarcoidosis exists [7]. Early treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis is essential in order to prevent permanent scarring of the skin. A conservative approach is usually followed except for those with systemic manifestations. Chronic cutaneous lesions like lupus pernio and those that may cause scarring also require immunosuppressive therapy for long periods [8]. Oral hydroxychloroquine, levamisole, allopurinol or colchicine can be used as steroid sparing agents in some cases [9]. In our series, we could achieve rewarding results by selective administration of oral prednisolone in the first case.

The clinical silence of sarcoidosis precludes an accurate prognosis, as it depends on the extent and severity of systemic involvement. Though cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis may occur at any stage of the disease, it commonly occurs at the onset. Spontaneous remissions are known to occur. However, in a recent study 30% of cases reporting with initial specific lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis later developed systemic involvement [10].

These two cases highlight a purely cutaneous presentation of a protean and uncommon disease. A long term follow up is imperative to look for systemic involvement if not demonstrated initially.

Conflicts of Interest

None identified

References

- 1.Scadding JG, Mitchell DN. Sarcoidosis. 2nd ed. Chapman and Hall; London: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hano R, Needelman A, Eiferman RA, Callen JP. Cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas and the development of systemic sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gawkrodger DJ. Sarcoidosis. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, editors. Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford Blackwell Science; London: 1998. pp. 2679–2702. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lever WF, Schamberg-Lever G. Histopathology of the skin. 7th ed. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1990. pp. 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callen JP, Hanno R. Serum angiotensin I converting enzyme level in patients with cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:232–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huisman PM, Van Royen EA. Skin uptake of Gallium 67 in cutaneous sarcoidosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:243–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, Landthaler M, Szeimies RM. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:581–584. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson NJ, King CM. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74:649–652. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.74.877.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baughman RP, Lower EE. Steroid-sparing alternative treatments for sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 1997;18:853–864. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mana J, Marcoval J, Graells J, Salazar A. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882–888. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890430098013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]