Abstract

The Indian armed forces have over 5000 cases of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection since 1990. The spouses of the affected soldiers are at a constant risk of contracting infection if not informed of their husband's HIV status. The onus of counselling the spouse has been delegated to the commanding officer (CO) of the soldier as per policy. The spouses usually reside at their hometown away from the soldier's unit and bridging this “geographical discordance” and offering effective counselling becomes a tricky issue for the commanding officer (CO). This article examines the effectiveness of this strategy as practised in Indian armed forces.

Key Words: HIV, Partner counseling

Introduction

The Indian armed forces have experienced a fair share of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic and approximately 5000 personnel have tested positive for HIV since 1990. The incidence rate since 1999 seems to have stabilised at around 500 cases per year [1]. The patients are usually detected HIV positive during blood screening for voluntary blood donation, surveillance of patients who have sexually transmitted disease (STD), herpes zoster or tuberculosis and when the physician suspects immunodeficiency clinically [2].

It is morally and ethically imperative to inform the spouse/partner of the individual's HIV positive status. Once informed, the spouse can decide to access available HIV prevention, counselling and testing services. If not infected with HIV, they can be advised about protected sex, thus reducing the likelihood of acquiring the virus or, if already HIV-infected, their prognosis can be improved through earlier diagnosis and treatment. The entire process comprises the field of “Partner Counselling and Referral Services” (PCRS). A spouse who is not informed by either the infected soldier or the authorities is at an imminent risk of contracting the infection with every sexual encounter.

PCRS in Armed Forces

How effectively have we tackled the issue of PCRS in the armed forces? The existing policy identifies the Commanding Officer (CO) of the affected soldier as the person primarily responsible for counselling in consultation with his medical advisors. The guidelines issued for prevention and management of human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the armed forces in this regard (DGAFMS letter number 5496/HIV policy/DGAFMS/DG 3-A dated 23 May 2003) mentions “In case of families of HIV positive serving personnel, responsibility for counselling will rest with the Commanding Officer/Officer Commanding of the unit in consultation with the Senior Executive Medical Officer (SEMO)/Authorised Medical Attendant (AMA), to motivate them to get themselves investigated at the nearest service/civil HIV testing centre for E/R/S test.” The policy is clear about the need to inform the spouse by the CO. However, it leaves many questions unanswered.

Does the CO automatically qualify as the best counsellor? What training has he received to carry out this delicate task? Counselling in HIV is a very specialised field and requires appropriate training even for doctors who wish to carry out this activity. Would not the regimental medical officer (RMO) or the medical officer (MO) at nearby field ambulances make for better counsellor? It might be far easier to impart a systematic training to medical personnel in this respect using locally available resources.

If we do concede, that the CO is the best available option, a far more disturbing aspect needs deliberation. How does the CO go about executing his role? Occasionally, the CO is lucky enough to have the spouse residing with the soldier in the same unit. In that case a counselling session can take place in the unit itself. More often than not, there exists a “geographical discordance” between the soldier's unit and his hometown, where his wife normally resides.

What then is the best way to tackle this situation? Should the CO post a letter to the spouse? If it is done so (as is sometimes the case), there is no form of support service available to the wife when the devastating news gets broken. Also, in a fair proportion of cases, the wife is uneducated and requires the services of a third person to read the letter. The confidentiality of the patient's HIV status is then no longer restricted to the spouse.

Effectiveness of our system

Are the other health care providers in India facing a similar problem? Not really. In all other civilian centres managing HIV patients, the treating physician, the patient and the spouse usually reside in the same town/city. It is easy for the physician to sound the patient about the need to inform the spouse and do the counselling himself in the next visit. The patient too feels comfortable if the treating doctor acts as the counsellor in such a delicate situation. Alternatively trained counsellors are available to perform this skilled task. The peculiar nature of “geographical discordance” in armed forces prevents such a simple system to exist and is undoubtedly the biggest hurdle that we face today for delivering effective PCRS.

Is the current system, in its present form, working effectively? We did a cross sectional survey of 86 HIV positive patients from immunodeficiency centre at Base Hospital, Delhi Cantt (BHDC) from Jan-Feb 2003. The median duration since testing positive for HIV was > 5 months (Table 1). Of these, 60% of soldiers had not yet informed their spouses. Interestingly, the spouses had not received any official counselling or intimation from the COs either! The soldiers could not muster the necessary courage to inform their wives, fearing the stigma and possible repercussions. Though they agreed in principle about the need to inform their spouse, they kept on postponing the decision. Also, despite necessary information, the soldiers found it very difficult to justify sudden usage of condoms well into their married life. Rather than face embarrassing questions, they preferred to continue with unprotected sex. The spouse was thus continuously facing the risk of contracting HIV infection from her husband, when the knowledge of her husband's HIV status would have empowered her to say an emphatic ‘No’ to unprotected sex.

Table 1.

Profile of patients surveyed at BHDC, New Delhi

| Number of patients | 86 |

| Mean age ± SD (years) | 35.1 ±6.29 |

| Married | 85 |

| Median time from detection of HIV (months) | 5 (IQR 17-2 months) |

| Concordance with spouse (n=85) | |

| a) Spouse HIV positive | 10 (12%) |

| b) Spouse negative | 23 (28%) |

| c) Spouse not informed | 51 (60%) |

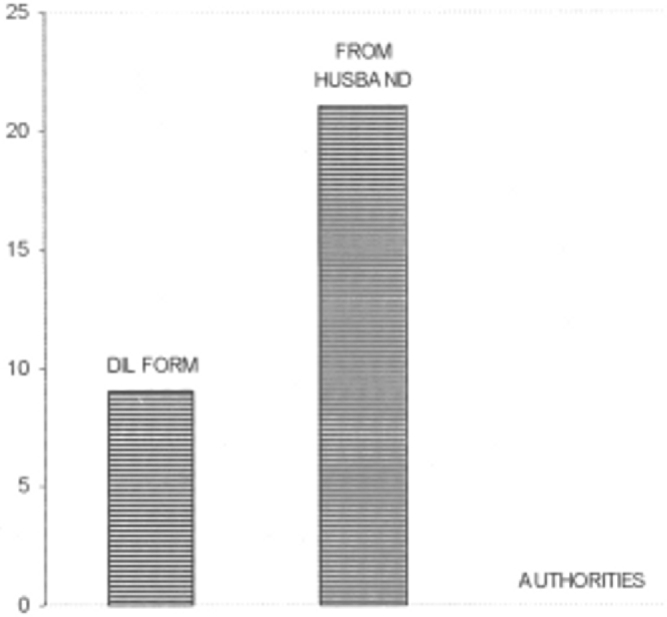

Do we have a feedback system to check whether the spouse was informed at all? Again, the answer is “No”. In another cross sectional survey of 30 spouses of HIV positive patients at BHDC who were interviewed, about 30% of them got their news when a Dangerously Ill List (DIL) form reached them. The others had been informed by their husbands (Fig 1). No official counselling letter had reached any of the spouses in the group surveyed.

Fig 1.

Mode of information of husband's HIV status (n=30)

Reappraisal of PCRS

The armed forces has made significant inroads in the last two years towards the management of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Antiretroviral drugs are available to the affected soldiers and their families. The policy towards disposal of service personnel has seen some radical changes. New immunodeficiency centres are being set up and are being suitably equipped. Despite teething troubles, the overall change has been a very positive one. PCRS in armed forces possibly represents our blind spot and a radical change in approach is needed if we are serious about protecting the spouses of soldiers from turning HIV positive.

Firstly, it is worth redefining the “Counsellor” in our system. Would the RMO/SEMO be a better choice with appropriate training? The CO could then restrict himself to the administrative aspects alone. However, if it is decided that the primary onus lies with the CO, then a systematic training program needs to be set in motion, sensitising all the COs about aspects of counselling. This would then need to be an ongoing activity.

The issue of “geographical discordance” will still not be tackled effectively. The Centre for Disease Control (CDC), USA has advocated many effective approaches for PCRS. These include the client referral approach, the dual referral approach and the contract referral approach [3]. In the client referral approach, the HIV-infected client informs his or her partner of their possible exposure to HIV and refers them to counselling, testing, and other support services. In the dual referral approach, the HIV-infected client and the health care provider inform the partner together. In the contract referral approach, if the HIV-infected client is unable to inform the partner within an agreed-upon time, the provider has the permission and necessary information to do so.

When the spouse is residing with the soldier in the same station, the dual referral approach can be practised. However, for the vast majority of our soldiers, the contract referral approach is possibly the best possible option. On being tested positive for HIV, the patient can be given a 3 month period in which to inform his spouse and sent on annual leave. At the end of 3 months, the spouse should be called for a counselling session by the CO and the RMO along with the patient if she lives locally. Alternatively, a letter should be dispatched if she lives away. This may be preceded by a telephone call so that she is mentally primed to receive the news. The awareness of the fact that a letter will anyway reach his wife in 3 months may ensure that the soldier informs his wife himself in most cases. An effective feedback system has to be worked out to confirm that the spouse has been adequately informed.

There are many other aspects that would need to be smoothened out. How best to word the letter? What kind of a feedback system is to be developed? Should the wife be advised to travel to the nearest MH to get counselled? Who coordinates the details? Who pays for her travel expenses? These are difficult questions that need urgent answers. Else, we shall be putting thousands of spouses of the HIV positive soldiers at a real risk of getting infected everyday.

Conflicts of Interest

None identified

References

- 1.Singh M. Proceedings of the International Conference and CME on HIV/ AIDS: The Military Face; Sept 2004: AFMC, Pune. DGAFMS and US Pacific Command. 2004. Status of HIV/AIDS in Indian Armed Forces. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh M. HIV/AIDS scenario in Armed Forces. Proceedings of the Armed Forces workshop on HIV/AIDS; 2002 Nov 08-09: Base Hospital. Office of DGAFMS; New Delhi: 2002. Status of HIV/AIDS among Armed Forces personnel; pp. 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention . Division of HIV/ AIDS Prevention; National Centre for HIV, STD and TB Prevention. Georgia; Atlanta: 1998. HIV Partner Counselling and Referral Services — Guidance. [Google Scholar]