Abstract

Objectives

To conduct a systematic literature review of selected major provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) pertaining to expanded health insurance coverage. We present and synthesize research findings from the last 5 years regarding both the immediate and long‐term effects of the ACA. We conclude with a summary and offer a research agenda for future studies.

Study Design

We identified relevant articles from peer‐reviewed scholarly journals by performing a comprehensive search of major electronic databases. We also identified reports in the “gray literature” disseminated by government agencies and other organizations.

Principal Findings

Overall, research shows that the ACA has substantially decreased the number of uninsured individuals through the dependent coverage provision, Medicaid expansion, health insurance exchanges, availability of subsidies, and other policy changes. Affordability of health insurance continues to be a concern for many people and disparities persist by geography, race/ethnicity, and income. Early evidence also indicates improvements in access to and affordability of health care. All of these changes are certain to ultimately impact state and federal budgets.

Conclusions

The ACA will either directly or indirectly affect almost all Americans. As new and comprehensive data become available, more rigorous evaluations will provide further insights as to whether the ACA has been successful in achieving its goals.

Keywords: Affordable Care Act (ACA), health insurance, health care, systematic review

On March 23, 2010, following a long and controversial political and legislative process, President Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) into law, ushering in the most significant changes to the U.S. health care system since the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. The ACA includes a series of ambitious reforms that build upon the existing system of employer‐sponsored insurance (ESI) and creates new requirements for individuals, employers, health care providers, and insurance companies. It is intended to address three main areas: access to health insurance, health care costs, and the delivery of care (Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum 2015). Certain elements of the law became active soon after its passage in 2010, but most provisions took effect in 2014 (see Table 1 for the ACA timeline).1

Table 1.

Timeline for Implementation of Major Provisions of the ACA

| 2010 | Employers are provided funding to cover individuals retiring between the ages of 55 and 65 |

| Federal government offers tax credits to cover a portion of the employer's contribution for small businesses with less than 25 employeesa | |

| Establishes a new Patient's Bill of Rightsb | |

| Requires all plans to include certain preventive services without cost‐sharingb | |

| Insurance companies cannot deny coverage to children under age 19 with preexisting conditionsb | |

| Creates a new process to monitor premium rate increases and report the minimum medical loss ratioa | |

| *Young adults are covered by their parent's health insurance until age 26 (dependent coverage provision)b | |

| Provides financial incentives to PCPs, nurses, and physician assistants, and increases payments to PCPs in rural communities, underserved areas, and community health centersc | |

| 2011 | Provides a 10% bonus payment from Medicare to PCPs for 5 years |

| 2012 | Imposes new annual fees on the pharmaceutical manufacturing sectora |

| Creates a Medicare Value‐Based Purchasing programd | |

| 2013 | *Initial open enrollment in the individual health insurance marketplace beginsd |

| The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative begins to test models for reimbursement | |

| *Increases Medicaid reimbursement rates for primary care services provided by PCPs to 100% of the Medicare rates for 2013 and 2014 | |

| Increases Medicare Part A tax rate from 1.45% to 2.35% on individuals earning over $200,000 and couples earning $250,000, as well as a 3.8% tax on unearned income for high‐income tax payers | |

| Imposes 2.3% excise tax on the sale of any taxable medical device | |

| Modifies tax treatment of health savings and flexible spending accounts | |

| 2014 | Insurance companies cannot deny coverage based on preexisting conditions and can only vary rates based on rating area, family size, tobacco use, and age (but not on health status, previous claims history, or gender) |

| Risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridor programs go into effect to help stabilize premiums and reduce adverse selection | |

| *Increases small business tax credits for those participating in the state insurance exchangesa | |

| *Provides tax credits to individuals or families earning between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level who purchase their health insurance through the exchanges | |

| All health insurance plans must provide an “essential health benefits package” | |

| *Expands federally funded Medicaid coverage to cover individuals earning up to 133% of the federal poverty level in certain states | |

| Initial enrollment in the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) begins on November 15 | |

| Imposes annual fees on the health insurance sectora | |

| *U.S. citizens without health insurance pay a tax penalty (individual mandate)a | |

| 2015 | *Employers with 100 or more full‐time employees pay a penalty if they fail to offer health insurance coverage (employer mandate) |

| 2016 | *Employers with 50 or more full‐time employees pay a penalty if they fail to offer health insurance coverage (employer mandate) |

| 2018 | Excise tax of 40% imposed on employer‐sponsored private health insurance plans above a certain value (“Cadillac tax”) |

Provisions went into effect on January 1, unless noted otherwise. The provisions discussed in this review are marked with an asterisk (*). PCP stands for primary care physician.

Assessed annually.

Effective for plans beginning on or after September 23, 2010.

Effective dates vary.

Effective October 1.

Source: Compiled by the authors using information from the US Department of Health and Human Services (http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts/timeline/timeline-text.html) and Kaiser Family Foundation (http://kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/summary-of-the-affordable-care-act/) websites.

The ACA includes multiple strategies to target different groups and increase overall insurance coverage. Young adults are now able to remain on their parents’ insurance plans as dependents until age 26 (dependent coverage provision). Larger employers are required to offer affordable, comprehensive health insurance to full‐time employees (employer mandate). Individuals who do not have ESI must purchase insurance on their own or pay a penalty (individual mandate), and premium tax credits are available to some. These individuals and small businesses can purchase plans through state‐level exchanges or the federal marketplace. To assist low‐income individuals, the ACA expands Medicaid eligibility to all individuals under age 65 (nonelderly) with annual incomes up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level, but not all states have agreed to participate. These provisions aim not only to expand insurance coverage but also to improve the affordability of insurance plans.

The ACA also imposes new regulations on insurance companies and their policies. For example, insurance companies can no longer charge higher premiums or deny coverage due to preexisting conditions, and insurance policies have to provide a minimum amount of preventive services without any cost‐sharing. The ACA calls for changes in various taxes pertaining to insurance policies and overall financing. Other provisions focus on improving the delivery of care by streamlining services, incorporating health information technology, strengthening the health care workforce, reducing fraud and waste, and altering payments in a way that incentivizes providers to contain costs while improving the quality of care.2

Assessing the full and lasting impacts of the ACA is challenging because the provisions are multifaceted and the potential outcomes extend to taxpayers, patients, health care providers, insurance companies, and governments. Preimplementation projections of the ACA's effects were largely based on simulation models of earlier Medicaid enrollment or the Massachusetts health insurance expansion (e.g., Gruber 2011a). In 2010, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO 2010) projected that by 2019, 32 million people would gain health insurance coverage, ESI coverage would decline slightly, and significant increases in federal spending due to the ACA would be offset by increased revenue. Making precise predictions is daunting, however, as many factors affect successful implementation of the ACA, such as enrollment levels, insurer participation, and providers’ willingness to accept Medicaid patients.

While the ACA is comprised of 10 titles and hundreds of sections, this review focuses on key provisions related to expansion of health insurance coverage through dependent coverage provisions and ESI, health insurance exchanges, employer and individual mandates, and Medicaid expansion. Unlike other summaries of the existing literature (e.g., Hall and Lord 2014; Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum 2015), we conduct a structured and systematic review of research findings regarding the effects of the ACA since 2010 and focus on the key provisions listed above. Besides a summary and synthesis of current findings, we also offer suggestions for future research.

Methods

Literature Search

We used three methods to identify relevant studies for our analysis. First, we performed structured and systematic searches using the Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science, the National Library of Medicine's Medline (PubMed), and the American Economic Association's EconLit. We searched for the phrase “Affordable Care Act” in titles, abstracts, or topics without any additional keywords to avoid inadvertently excluding relevant studies. These searches yielded a total of 1,375 studies from Web of Science, 1,656 studies from Medline, and 97 studies from EconLit. We focused on published articles in the English language that appeared in peer‐reviewed scholarly journals as well as reports that appeared in the “gray literature.” Second, we augmented our systematic searches to include relevant reports from various research organizations and government agencies. Third, we browsed the reference sections of the retrieved articles. The entire search process was conducted from July to September 2015, and it was limited to studies appearing since 2010.

Inclusion Criteria and Screening

Our inclusion criteria are essentially based on whether the study provides a systematic evaluation of one or more elements of the ACA's implementation. Given the vast number of studies on this topic, we focus on those provisions related to the expansion of health insurance coverage. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included, but we excluded studies that merely describe the legislation or examine data from prior to the implementation (i.e., to establish a baseline). We also eliminated any studies that simply use projections or extrapolations based on data prior to implementation of the ACA. Finally, we excluded studies pertaining to ethical, legal, or political aspects of the ACA.

During the first round of screening, two coauthors independently screened the title and abstract of each study to identify those that potentially met the inclusion criteria. After a comparison of the two sets of ratings, any inconsistencies were resolved through discussions. When necessary, a third coauthor was asked to render a judgment. As a result, we obtained 162 full‐text articles for a final examination pertaining to relevance and to eliminate any inappropriate items such as opinion pieces. Ultimately, we selected a total of 72 studies through our elaborate screening process. These were augmented by 24 reports and articles found in the gray literature. While Table 2 lists the final set of 96 studies together with brief descriptions, given space limitations, we do not cover all in the results section. The discussion below includes only those studies that were deemed most relevant or provide more recent evidence, and they are organized by groupings of key ACA provisions.

Table 2.

Summary of Selected Research Studies

| Research Study | Data/Methods | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham, Feldman, and Simon (2014)* | National Association of Insurance Commissioners; CPS; KFF; Descriptive statistics to describe each state's insurance market and to test the differences in attributes between exchange participants and nonparticipants; Multivariate regression analysis with an incumbent insurer's decision to participate in the exchanges as the outcome measure | Insurer participation in exchanges is related to presence in the region and size of the insurer. |

| Akosa Antwi, Moriya, and Simon (2013)* | SIPP; DD with insurance coverage and labor market outcomes as outcome measures | Dependent coverage provision is associated with increases in coverage and parental coverage among young adults relative to comparison group. |

| Akosa Antwi et al. (2015)* | National Emergency Department Sample; DD with ED visits as the outcome measure | Dependent coverage provision is associated with modest decline in ED visits for young adults relative to comparison group. |

| Akosa Antwi, Moriya, and Simon (2015)* | Nationwide Inpatient Sample, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; DD with number and sources of inpatient admissions, fraction of admissions insured, and the intensity of treatment as outcome measures | Dependent coverage provision is associated with increases in mental health visits and inpatient visits by young adults relative to comparison group. |

| Angier et al. (2015)* | Longitudinal study of coverage status for adult encounters in community health centers (CHCs); multivariate regression analysis of CHC visits by insurance and Medicaid expansion status | The proportion of uninsured visits decreased and Medicaid‐covered visits increased in Medicaid expansion states in 2014 compared to 2013. |

| Artiga, Rudowitz, and Ranji (2015)* | Focus groups with either previously uninsured adults who enrolled in the ACA Medicaid expansion (Ohio and Arkansas) or those who would be eligible if their state had expanded Medicaid (Missouri) | States’ decision whether to expand Medicaid or how they went about the expansion implementation affected experiences of low‐income adults, including their access to care as well as their ability to work. |

| Artiga, Stephens, and Damico (2015)* | CPS; Descriptive statistics on the uninsured and those who fall within the “coverage gap” after imputing eligibility for ACA subsidies, unauthorized immigrant status, and ESI offer status | Estimate there are 3.7 million adults in the coverage gap in 22 states that have not expanded Medicaid as of March 2015. |

| Bachrach, Boozang, and Glanz (2015)* | Interviews with state officials; estimates of the budgetary impact of Medicaid expansion in a sample of eight states | Medicaid expansion allows states to realize savings (through reductions in spending on programs for the uninsured) and revenue gains (through existing insurer or provider taxes). |

| Barbaresco, Courtemanche, and Qi (2015)* | BRFSS; DD with outcomes related to health care access, preventive care utilization, risky behaviors, and self‐assessed health | Dependent coverage provision is associated with some improvements in health care access and health‐related outcomes among young adults relative to comparison group. Report large gains for men and college graduates. |

| Barcellos et al. (2014)* | American Life Panel; multivariate regression analysis with knowledge about ACA, health insurance literacy, and expectations for changes in health care as outcomes | Knowledge of the ACA and health literacy is low overall, especially among low‐income individuals. |

| Barker et al. (2014a)* | Area Health Resource File; descriptive statistics on geographic variation in marketplace premiums | Premiums for exchange plans are higher in less densely populated areas. |

| Barker et al. (2014b)* | Healthcare.gov and state agencies; overview of important factors that influence the differences in marketplace plans across geographic areas (urban vs. rural) | Urban counties, on average, have more plans and plans with higher actuarial values available on their exchanges. |

| Blavin et al. (2015)* | Health Reform Monitoring Survey; multivariate regression analysis with employer offer rates, employee take‐up rates, and ESI coverage as outcomes | Offer, take‐up, and coverage rates for ESI have remained the same under the ACA. |

| Blumberg and Rifkin (2014)* | Case study using stakeholder interviews in eight states | Identify reasons for SHOP's slow start and areas for improvement. |

| Blumenthal and Collins (2014)* | Overview and assessment of existing findings | Provide a progress report on ACA as of mid‐2014. |

| Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum (2015)* | Overview and assessment of existing findings | Review various effects of the ACA at the 5‐year mark. |

| Brandon and Carnes (2014)* | Case studies of marketplace launches in Kentucky and North Carolina | Describe elements of successful exchanges. |

| Brooks (2014)* | Description and discussion of the “family glitch” | Many dependents face challenges with “affordable” care and will remain uninsured if the family glitch is not fixed. Low‐income families and those who live in Medicaid nonexpansion states have been disproportionately affected. |

| Busch, Golberstein, and Meara (2014)* | MEPS; DD with insurance coverage and out‐of‐pocket medical expenditures as outcome measures | Dependent coverage provision is associated with a decrease in the proportion of young adults with high out‐of‐pocket medical expenses relative to comparison group. |

| Cantor et al. (2012)* | CPS; DD with insurance coverage by source as outcome measure | Estimate rapid and substantial increase in the number of young adults who gained parental coverage by 2011. |

| Carlson et al. (2014)* | CPS; DD with self‐rated health as outcome measure | Dependent coverage provision is associated with improvements in self‐reported health among young adults relative to comparison group. |

| CMS (2014)* | CMS press release of data on marketplaces | Reports that more issuers and health plans are available through exchanges in 2015 than in 2014. |

| Chandra, Holmes, and Skinner (2013)* | Various sources; overview of trends in health care spending and the contributing factors | As of 2013, cost‐saving features of the ACA were not yet fully implemented, so they could not explain the slowdown in health care expenditures that began in 2006. |

| Chua and Sommers (2014)* | MEPS; DD with insurance coverage, selected measures of health care utilization, and self‐reported health as outcome measures | The dependent coverage provision is associated with improvements in self‐reported health status and protection against medical expenditures among young adults aged 19–25 years. |

| Claxton et al. (2012) | KFF/HRET Survey of Employer Health Benefits; Descriptive statistics on ESI coverage, premiums, and parental coverage for young adults | Examine trends in ESI coverage, premiums, and parental coverage for young adults. |

| Claxton et al. (2014a)* | KFF/HRET Employer Health Benefit Survey; descriptive statistics on ESI offers, enrollment, premiums, cost‐sharing, and worker contributions | The ESI market has experienced little change since the passage of the ACA. |

| Cohen and Martinez (2015)* | Early release of NHIS estimates for health insurance coverage and the overtime trends | Provide estimates of health insurance coverage for 2014 by age, race/ethnicity, geography, type of insurance, and poverty level. |

| Collins et al. (2012) | CF Health Insurance Tracking Survey; descriptive statistics on insurance coverage and burden of medical bills and debt | The health and monetary consequences of uninsurance are significant for young adults, particularly those who are poor. |

| Collins et al. (2013a)* | CF Health Insurance Tracking Survey; descriptive statistics on uninsurance and enrollment under parents’ policy among the young adults | Report increase in the number of young adults on a parents’ policy between 2011 and 2013, in particular among those with low incomes. |

| Collins et al. (2013b) | CF ACA Tracking Survey; descriptive statistics on consumers’ experiences in marketplace at the end of the first month | Majority of potentially eligible adults are aware of the marketplace as a source of coverage but few reported visiting it at this point in time. Some individuals who visited but did not enroll yet reported technical problems with marketplace websites. |

| Collins et al. (2014a)* | MEPS; descriptive statistics on the national trends in ESI coverage, premiums, cost‐sharing, and worker contributions | ESI premiums, deductibles, and employee contributions increased between 2003 and 2013 but at a slower rate after 2010. |

| Collins et al. (2014b) | CF ACA Tracking Survey; descriptive statistics on consumers’ experiences in marketplace at the end of the first 3 months | Consumers’ ability to compare benefits and premiums in the marketplace has improved since the rollout, but many reported difficulties with plan selection. |

| Collins et al. (2015a)* | CF Biennial Health Insurance Survey; descriptive statistics on health insurance coverage, affordability, burden of medical bills and debt, access to routine health care | Report results of survey showing improvements in coverage and affordability. |

| Collins et al. (2015b)* | CF ACA Tracking Survey; descriptive statistics on consumers’ experiences with marketplace and Medicaid coverage | Report results of survey showing satisfaction with health plans and improvements in coverage and access. |

| CBO (2014)* | Various sources; estimates of the number of uninsured subject to ACA‐related penalties | Estimates 4 million out of 30 million uninsured will be subject to penalties in 2016. |

| CBO (2015a)* | Various sources; estimates the budgetary and economic consequences that would arise from repealing the ACA | Provides estimated effects of repeal on health insurance coverage and the federal budget both in the short and long term, with a warning that they are subject to substantial uncertainty. |

| CBO (2015b)* | Various sources; federal budget projections for 2015–2025 | The appendix provides estimated budgetary effects of the insurance coverage provisions of the ACA. |

| Cox et al. (2014)* | Marketplace enrollment data from seven states; calculate state‐specific measures of market competition for individual plan markets and the exchanges | There are some instances in which insurers’ market shares have changed significantly under the ACA, with some notable examples due to new entrants. |

| Cox et al. (2015)* | Health insurer rate filings in 10 state departments and Washington, DC; descriptive statistics on marketplace premiums and insurer participation | Insurer participation in 2016 is similar to 2015. Average increase in premiums for silver plans between 2015 and 2016 is 4.4%. |

| Cunningham, Garfield, and Rudowitz (2015)* | Ascension Health data on discharges and hospital finances; pre‐post descriptive statistics on discharge volumes, uncompensated care, and hospital finances | Evaluate changes in hospital discharges and financial outcomes for Ascension Health system in Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states immediately before and after the ACA implementation. |

| Depew and Bailey (2015)* | MEPS; DD with total premiums and employee contributions for family or single plans as outcomes | Premiums for family health plans increased by 2.5–2.8% due to the dependent coverage provision. |

| Dickstein et al. (2015)* | Healthcare.gov; U.S. Census; Multivariate regression analysis with number of insurers and health insurance premiums as outcomes | Examine whether the definition of the coverage region affects market outcomes in the ACA insurance exchanges. |

| Doty, Rasmussen, and Collins (2014)* | CF ACA Tracking Survey; descriptive statistics on insurance coverage and marketplace experiences among Latinos | Uninsured rate among Latinos decreased in states expanding Medicaid. Overall rate of uninsured adults decreased from 20% in 2013 to 15% in 2014. |

| Gabel et al. (2013)* | Survey of private firms with 3–50 employees; descriptive statistics on insurance plans in the small‐group market and small employers’ experiences with SHOP exchanges | Both small firms that decided to offer health insurance benefits and those that did not rated most features of SHOP exchanges highly. These decisions were very price sensitive. |

| Geyman (2015) | Overview and assessment of existing findings | Assesses the ACA's first 5 years and presents arguments for replacing it with single‐payer national health insurance. |

| GAO (2014a)* | CMS and state data; descriptive statistics on the number and types of issuers participating in exchanges and prior to the exchanges | Most state exchanges had multiple issuers in 2014, with variation across states. |

| GAO (2014b)* | CMS, state data, and interviews with stakeholders; descriptive statistics and stakeholders’ views regarding SHOP characteristics | Discusses factors contributing to lower than expected enrollment in the SHOP. |

| GAO (2015)* | Various sources; structured literature search; stakeholder interviews; descriptive statistics on premiums | Examines the effects of tax credits and the availability of affordable health plans. Reviews the variations in premium costs by income, age, and geography. |

| Giovannelli, Lucia, and Corlette (2015)* | Review of state‐specific provider network adequacy standards for marketplace plans in the 50 states and Washington, DC | State regulators seek to enhance network transparency for consumers and to monitor compliance. |

| Golberstein et al. (2015)* | National inpatient samples; California state data; DD with inpatient admissions and ED visits for psychiatric diagnoses as outcomes | ACA's dependent coverage provision is associated with increased inpatient admissions and decreased ED visits for 19‐ to 25‐year olds, relative to comparison group. |

| Graetz et al. (2014)* | Premium data from all marketplaces; descriptive statistics on affordability of premiums (by age, income, geographic area) | Many people with incomes just above threshold for subsidies will not have affordable coverage, and hence will be exempt from the individual mandate. |

| Haeder and Weimer (2013)* | Various sources; qualitative analyses to identify the common themes in insurance early exchange implementation; multivariate regression analysis of timely exchange establishment | Many state commissioners of insurance have played constructive roles in exchange planning despite strong political opposition to the ACA from state governors and legislatures. |

| Hall and Moore (2012) | State data; descriptive statistics on the Preexisting Condition Insurance Plan enrollment and costs | Examine the experience with the temporary Preexisting Condition Insurance Plan. |

| Hall and Swartz (2012) | Case studies of Maryland, California, and Colorado | Document the differences across states in terms of their initial approaches and experiences with establishing and designing exchanges. |

| Hall and Lord (2014)* | Overview and assessment of existing findings | Insurance industry's profitability does not seem to be hurt, individual insurance premiums have been lower than expected, and government costs have been less than initially projected. |

| Hamel et al. (2014)* | KFF Survey of Nongroup Health Insurance Enrollees; descriptive statistics on the views and experience of nongroup enrollees | Majority with exchange coverage is previously uninsured and satisfied with coverage. |

| Hernandez‐Boussard et al. (2014)* | State Inpatient and Emergency Department Databases from California, Florida, New York; DD with ED visits (by various individual characteristics) as the outcome measure | Rate of ED visits increased after ACA's dependent coverage provision implementation but at a slower rate for young adults relative to comparison group. |

| Holahan, Buettgens, and Dorn (2013)* | Urban Institute's Health Insurance Policy Simulation Model; national and state‐level projections of cost and coverage under the ACA Medicaid expansion for the period 2013–2022 | The states that had not expanded Medicaid as of July 2013 generally are the ones that would potentially benefit the most from this provision. |

| Howard and Shearer (2013) | Description and discussion of various state policies and programs to reduce churning and promote continuity of coverage/care | There are various approaches by states to limit the program eligibility changes and/or the impact those changes have on individual consumers. |

| Jacobs and Callaghan (2013)* | Qualitative and quantitative analysis to explain the variations in relative state progress in implementing Medicaid expansion | Examine how economic conditions, past policies, politics, and administrative capacity influence states’ Medicaid expansion decision. |

| KFF and CF (2015)* | KFF/CF 2015 National Survey of Primary Care Providers; descriptive statistics on the impact of the ACA on patient population, providers’ practice capacity, and their opinions about the ACA's impact on medical practice | Majority of primary care providers surveyed saw increase in uninsured or Medicaid patients (in expansion states) without reducing quality of care. |

| Karpman, Weiss, and Long (2015)* | Urban Institute Health Reform Monitoring Survey; descriptive statistics | The proportion of middle‐ and high‐income adults reporting access problems decreased in 2014 compared to 2013. Disparities persist for certain age, income, and ethnic groups, and 40% of adults reported various provider access problems. |

| Kaufman et al. (2015)* | Encounter data from Quest Diagnostics; descriptive statistics on the number of newly identified diabetes patients in 2013 versus 2014 | Number of Medicaid patients with new diabetes diagnoses increased, particularly in Medicaid expansion states. |

| Keehan et al. (2015)* | Data from various sources including CMS, Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Census; projections based on actuarial and econometric modeling methods | Provide various projections for national health expenditures (by spending categories, per enrollee, by sponsor type, etc.) for 2014–2024. |

| Kirzinger, Cohen, and Gindi (2013)* | NHIS; descriptive statistics on the trends in insurance coverage and source of coverage among young adults | After the dependent coverage provision of the ACA took effect, private health insurance coverage among young adults aged 19–25 increased relative to a comparison group, while coverage in their own name has decreased. |

| Kotagal et al. (2014)* | BRFSS, NHIS; DD with health status, presence of a usual source of care and ability to afford medications, dental care, or physician visits as outcome measures | Find increase in coverage for young adults of 19–25 years old relative to a comparison group, but more limited changes in access to care and health status. |

| Kowalski (2014)* | National Association of Insurance Commissioners data; state‐specific seasonally adjusted trend regressions of health insurance coverage, premiums, and costs | Suggests that state policies toward the ACA have differential effects on welfare of market participants. |

| Lau et al. (2014)* | MEPS; pre‐post design using multivariate regression analysis of health care use including routine examination in the past year, blood pressure/cholesterol screenings, influenza vaccination, and annual dental visit | ACA's dependent coverage provision has increased insurance coverage and the use of some preventive services among young adults. |

| Levitt, Cox, and Claxton (2015)* | Health Coverage Portal data on insurance company filings; descriptive statistics on marketplace enrollments (by state) | Discuss individual market coverage in 2014. About 85% of those with marketplace plans were eligible for subsidies. |

| Lipton and Decker (2015)* | NHIS; DD with likelihood of HPV vaccine initiation, completion and awareness as outcome measures | ACA's dependent coverage provision is associated with an increase in HPV vaccination rates for young adults relative to comparison group. |

| Martinez, Ward, and Adams (2015)* | NHIS; descriptive statistics on changes in health insurance coverage and selected measures of health care access and utilization | Document disparities in access to care, coverage, and health care utilization. |

| McCue and Hall (2013) | Insurer data from the Department of Health and Human Services; descriptive statistics on premium increases for individual and small‐group plans as well as the contributing factors including the ACA | Insurers attributed three‐quarters or more of the larger rate increases to factors such as trends in medical expenses. They attributed only a very small portion of these changes to the ACA. |

| McCue and Hall (2015)* | Insurer data from the Department of Health and Human Services; descriptive statistics on premium increases for individual and small‐group plans as well as the contributing factors including the ACA | Insurers attributed the great portion of larger rate increases to factors such as trends in medical expenses, and most of them did not attribute these changes to the ACA. |

| McMorrow et al. (2015)* | NHIS; descriptive statistics on the trends in insurance coverage and source of coverage among young adults | The dependent coverage provision reduced uninsurance mainly among high‐income young adults, while the later ACA provisions reduced uninsurance mainly among low‐ and moderate‐income young adults, particularly in Medicaid expansion states. |

| Mulcahy et al. (2013)* | IMS Health Charge Data Master database; DD with nondiscretionary ED visits (by type of insurance coverage and reason for visit) as the outcome measure | ACA's dependent coverage provision is associated with an increase in the privately covered proportion of young adult ED visits (and a decrease in uninsured young adult ED visits) relative to comparison group. |

| O'Hara and Brault (2013)* | ACS; DD with uninsurance and private health insurance coverage rates as the outcome measures | Estimate insurance rates by state, gender, race, ethnicity, English speaking, and citizenship status. Disparities by gender narrowed, but those by race and ethnicity persist. |

| Olson (2015) | Case study of Pennsylvania in terms of its existing Medicaid program and how it has been affected by the ACA | Examine financial and other considerations in policy makers’ Medicaid expansion decision. |

| Polsky et al. (2014)* | Data on all plans offered in the marketplaces from the Health Insurance Exchanges (HIX) 2.0 dataset; descriptive statistics on silver plans | Compare insurer competition, plan characteristics, and premiums in health insurance exchanges for rural and urban areas. |

| Polsky et al. (2015)* | Simulated patient study of primary care practices in 10 states; descriptive statistics on the availability of appointments and waiting times for appointments for new patients by state and insurance type | Availability of primary care appointments for Medicaid patients increased following an increase in Medicaid reimbursements while no changes were observed for the private insurance group. |

| Rasmussen et al. (2014)* | CF ACA Tracking Survey; descriptive statistics on premiums, out‐of‐pocket costs, people's ability to compare plans and their experiences in terms of finding out about their eligibility for financial assistance or Medicaid | Most adults with marketplace coverage are satisfied with their plans. Those with low or moderate incomes report having premiums and deductibles similar to those with ESI. |

| Rasmussen et al. (2015) | CF Biennial Health Insurance Survey; descriptive statistics on health insurance coverage, cost‐related problems getting needed care, and medical debt in California, Florida, New York, and Texas | California and New York have their own exchanges and expanded Medicaid. Uninsured rates in these states are lower and affordability is better than in Florida and Texas, which rely on the federal exchange and did not expand Medicaid. |

| Rosenbaum et al. (2014)* | Review plan‐to‐plan transition policies implemented in 16 states and Washington, DC, to mitigate the effects of churning and to ensure continuity of care. | There are various strategies to mitigate the effects of churning across Medicaid, CHIP, and publicly subsidized private coverage, but they are rather complex and may take time to implement and to yield the desired results. |

| Saloner and Le Cook (2014)* | National Survey of Drug Use and Health; DD with selected measures of mental health and substance abuse treatment as outcomes | ACA's dependent coverage provision is associated with increased use of mental health treatment among young adults relative to comparison group. No significant changes were observed in substance use treatment. |

| Schoen, Radley, and Collins (2015)* | MEPS, CPS; descriptive statistics on ESI plan trends regarding their premiums, affordability, worker contributions, and out‐of‐pocket costs | Report that the cost of ESI premiums rose faster than median incomes during 2003–2013. A slowdown in the growth rate of premiums was observed over the last 3 years following the ACA implementation. |

| Scott et al. (2015)* | National Trauma Data Bank; DD with uninsurance status and clinical outcomes for trauma patients as outcome measures | Dependent coverage provision is associated with a significant decrease in the rate of uninsured trauma patients ages 19–25, but there are no significant changes in clinical trauma outcomes. |

| Shane and Ayyagari (2014)* | MEPS; DD with insurance coverage by race, income, marital status, and policy holder status as the outcome measures | While the dependent coverage provision increased insurance coverage among all racial and ethnic groups, it did not reduce overall disparities. Disparities may have widened among low‐income individuals. |

| Skopec and Kronick (2013)* | Various sources including MEPS and marketplace insurance premiums from selected states; descriptive comparisons of the premiums in the individual and small‐group markets to earlier CBO estimates | Premiums for silver plans in 2014 are lower than CBO estimates and appear to be affordable for the most part. |

| Sommers and Kronick (2012)* | CPS; DD with insurance coverage and type as well as policy holder status as outcomes | Dependent coverage provision led to increases in insurance coverage for young adults, especially among minorities. |

| Sommers et al. (2013)* | NHIS, CPS; DD with insurance coverage and access to care as outcome measures | Dependent coverage provision is associated with significant increases in private health insurance and access to care for young adults relative to comparison group. |

| Sommers, Kenney, and Epstein (2014)* | Administrative records on Medicaid enrollment in four states, ACS; DD with coverage through Medicaid, private health insurance coverage, and uninsurance as outcome measures | Find steady increase in Medicaid enrollment in four Medicaid expansion states, especially among those with health‐related limitations. |

| Sommers et al. (2014a)* | Gallup‐Healthways, Well‐Being Index, and CMS data; multivariate regression analysis with insurance coverage and access to care as outcome measures | Report that 7.3 to 17.2 million adults gained coverage by mid‐2014. |

| Sommers et al. (2015)* | Gallup‐Healthways Well‐Being Index; multivariate regression analysis and DD with self‐reported coverage, access to care, and health as outcome measures | Self‐reported insurance coverage, access to primary care and medications, affordability, and health improved significantly after the first 2 years under the ACA. |

| Swartz, Hall, and Jost (2015)* | Various sources including interviews; case study of Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Maryland, Montana, and Texas | Describe various competitive strategies adopted by insurance carriers during the first year of the ACA marketplaces. These competitive strategies vary by state. |

| Vujicic, Yarbrough, and Nasseh (2014)* | NHIS, 2008–2012; DD with private dental benefits coverage, dental care utilization, and financial barriers to obtaining needed dental care as outcome measures | Dependent coverage provision is associated with “spillover” increases in dental coverage, dental care utilization, and affordability for young adults relative to comparison group. |

| Wallace and Sommers (2015)* | BRFSS; DD with insurance coverage, self‐reported health, and access to health care as outcome measures | Dependent coverage provision is associated with better self‐reported health and access to health care among young adults relative to comparison group. |

| Wilensky and Gray (2013) | Review of Medicaid policies in all 50 states and Washington, DC | Evaluate coverage of ACA‐required preventive services under Medicaid in different states. |

Studies that are marked with an asterisk (*) were deemed most relevant or provide more recent evidence and are discussed in this review.

ACA, Affordable Care Act; ACS, American Community Survey; BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CBO, Congressional Budget Office; CF, Commonwealth Fund; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; CPS, Current Population Survey; DD, difference‐in‐differences analysis; ED, emergency department; ESI, employer‐sponsored insurance; HRET, Health Research and Educational Trust; KFF, Kaiser Family Foundation; MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; SIPP, Survey of Income and Program Participation.

Results

Dependent Coverage Provision

Under the so‐called young adult mandate, individuals between the ages of 19–25 years are allowed to remain on their parents’ health insurance plans. Since this mandate took effect in 2010, many researchers have already examined the impact of the law on this population. Most of this literature uses a quasi‐experimental difference‐in‐differences approach to compare young adults aged 19–25 to slightly older individuals before and after 2010. Although magnitudes vary, all studies show a rapid increase in insurance coverage among young adults after this provision took effect (Cantor et al. 2012; Sommers and Kronick 2012; Akosa Antwi, Moriya, and Simon 2013; Kirzinger, Cohen, and Gindi 2013; O'Hara and Brault 2013; Chua and Sommers 2014; Kotagal et al. 2014). Collins et al. (2013a) reported that in 2013 an estimated 15 million young adults were on a parent's policy in the past 12 months, an increase of 1.3 million since 2011. Approximately half of these were full‐time students (Collins et al. 2013a). These estimates are in line with other studies suggesting that 1–3 million uninsured young adults gained coverage under the ACA (Akosa Antwi, Moriya, and Simon 2013; O'Hara and Brault 2013; Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum 2015; McMorrow et al. 2015).

The gains in coverage are especially pronounced for men, unmarried individuals, and nonstudents (Sommers et al. 2013). Consistent with adverse selection, young adults in worse health acquired coverage sooner and with greater frequency than others (Sommers et al. 2013). This mandate primarily benefitted those with relatively high incomes, while Medicaid expansion and marketplace reforms implemented in 2014 targeted lower income young adults (McMorrow et al. 2015). Overall, the rate of uninsured young adults decreased from 30 percent in 2009 to 19 percent in 2014, which translates to about 6 million of them remaining uninsured in 2014 (McMorrow et al. 2015). Disparities persist by race, ethnicity, and income (O'Hara and Brault 2013; Shane and Ayyagari 2014). Most studies report that gains in insurance coverage are associated with better access to health care for young adults (Sommers et al. 2013; Wallace and Sommers 2015), especially among men and college graduates (Barbaresco, Courtemanche, and Qi 2015). Others find that the ACA is associated with improvements in self‐reported health status among young adults (Carlson et al. 2014; Chua and Sommers 2014; Barbaresco, Courtemanche, and Qi 2015; Wallace and Sommers 2015).

Studies have examined the effect of expanded dependent coverage on the utilization of emergency department (ED) care (Mulcahy et al. 2013; Hernandez‐Boussard et al. 2014; Akosa Antwi et al. 2015), preventive services (Lau et al. 2014; Barbaresco, Courtemanche, and Qi 2015; Lipton and Decker 2015), dental care (Vujicic, Yarbrough, and Nasseh 2014), and mental health treatment (Saloner and Le Cook 2014; Golberstein et al. 2015). Akosa Antwi, Moriya, and Simon (2015) found that inpatient hospital visits increased 3.5 percent and mental health visits increased 9 percent among young adults, without significant differences in hospital length of stay or charges. ED visits actually decreased among young adults (Hernandez‐Boussard et al. 2014; Akosa Antwi et al. 2015).

Besides the changes in insurance coverage and health care utilization among this group, the proportion of young adults reporting high out‐of‐pocket spending for health care decreased significantly following passage of the ACA (Busch, Golberstein, and Meara 2014; Chua and Sommers 2014). Compared to individual plans, premiums for plans covering children have increased 2.5–2.8 percent more due to the dependent coverage provision, but employers absorbed much of this increase (Depew and Bailey 2015). The amount of uncompensated care for young adults decreased as a greater proportion of ED, trauma center, and psychiatric inpatient utilization being covered by private insurance (Mulcahy et al. 2013; Akosa Antwi, Moriya, and Simon 2015; Golberstein et al. 2015; Scott et al. 2015).

Overall Health Insurance Coverage, Access, and Affordability

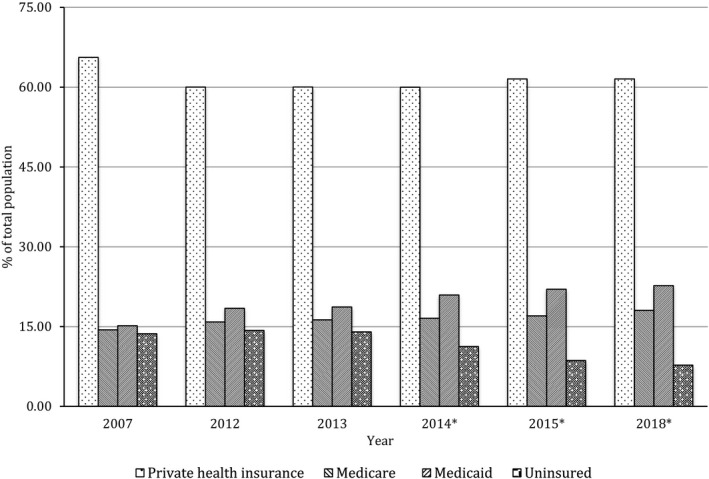

Preliminary data suggest that the law has substantially decreased the number of uninsured Americans (Sommers et al. 2014a, 2015; Cohen and Martinez 2015; Collins et al. 2015a,b). Figure 1 shows recent trends and projections for various sources of health insurance coverage and uninsurance rates (Keehan et al. 2015). The rate of uninsured adults decreased from 20 percent in 2013 to 15 percent in 2014 (Doty, Rasmussen, and Collins 2014), with further declines expected in coming years (Keehan et al. 2015). According to Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum (2015), an estimated 7–16 million uninsured people acquired coverage since 2010, with young adults, low‐income individuals, and minorities experiencing large gains. Similarly, the CBO (2015a) estimates that 17 million more people would have been uninsured in 2015 without the ACA. In the first 5 years of the ACA, 11.7 million purchased new plans from the marketplace, 10.8 million more have Medicaid coverage, and 3 million young adults are on their parents’ policies (Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum 2015).

Figure 1.

Health Insurance Coverage in the United States before and after the ACA

- Notes. *Indicates projections. Estimated percentages in a given year do not sum to 100% due to rounding and because individuals can have multiple sources of health insurance coverage.

Source: Keehan et al. (2015).

The majority of new enrollees are satisfied with their plans and feel more financially secure, although paying the premiums is still a challenge for some (Hamel et al. 2014; Collins et al. 2015b). The 2014 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey was the first since 2003 to show a decline in the number of adults reporting problems affording needed medical care (Collins et al. 2015b). Sommers et al. (2015) found significant improvements in access to primary care services and medications, affordability of care, and self‐reported health after the first 2 years of the ACA. Analyses indicate that expanded coverage has led to better access to a physician (Sommers et al. 2014a; Collins et al. 2015b) among all income groups (Karpman, Weiss, and Long 2015). Although the proportion without a regular source of care decreased from 29.8 percent in 2013 to 26 percent in 2014, almost 40 percent of respondents still had at least one access problem (Karpman, Weiss, and Long 2015). Disparities in access measures persist for different racial/ethnic and income groups (Cohen and Martinez 2015; Karpman, Weiss, and Long 2015; Martinez, Ward, and Adams 2015).

Over the 2016–2025 period, the CBO (2015b) projects that the ACA will reduce the number of uninsured by 24–25 million people relative to what would have occurred otherwise. However, about 26–29 million nonelderly are still expected to lack coverage, including unauthorized immigrants, those who live in non‐Medicaid expansion states, individuals affected by the “family glitch” (discussed below), and those who choose not to enroll in Medicaid or purchase insurance (CBO 2015b). The uninsured are more likely to be young, low‐income, and Hispanic (Collins et al. 2015b).

Health Insurance Exchanges, Tax Credits, and the Individual Mandate

Impact of Marketplace Design and Implementation

Political factors along with administrative capabilities influenced whether a state established its own exchange or relied on the federal marketplace (Haeder and Weimer 2013; Brandon and Carnes 2014). The type of exchange established and malfunctions in implementation can have significant implications for market participants (Kowalski 2014). According to Brandon and Carnes (2014), commodification of insurance plans (i.e., making them transparent and accessible to consumers), competition, and communication are three elements of successful exchanges.

Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum (2015) discussed several problems that occurred during ACA implementation including cancelation notices for noncompliant plans (which were later allowed to be renewed), narrow provider networks, and plans with very high deductibles. Furthermore, the public had a limited understanding and awareness of the ACA provisions (Collins et al. 2013a; Barcellos et al. 2014; KFF and CF 2015). Some survey results show that premiums and deductibles for plans purchased through the marketplace are comparable to ESI for those with similar incomes (Rasmussen et al. 2014). Premiums for marketplace plans are generally lower in areas that are more densely populated and in states with state‐based exchanges (Barker et al. 2014a).

Use of Marketplace Subsidies

Levitt, Cox, and Claxton (2015) estimate that plans purchased in the marketplace accounted for 43 percent of all individually purchased plans in 2014, and 85 percent of those enrolling in marketplace plans qualified for tax credits. A Government Accountability Office (GAO 2015) analysis suggests that the premium tax credit has contributed to higher rates of insurance coverage—in contrast to the employer tax credit, which had a more limited impact. In 2014, tax credits reduced marketplace premiums by an average of 76 percent (GAO 2015). As incomes rise and subsidies decline, however, premiums may increase sharply, making it increasingly difficult for those at the subsidy threshold (300–400 percent of the FPL) to afford health insurance (Graetz et al. 2014).

Although almost anyone can purchase insurance through the marketplace (undocumented immigrants is a key exception), those who have access to ESI may not be eligible for tax credits, even if they meet the income requirements (HHS, 2014).3 Employees are not eligible if they and/or their spouses are offered “affordable” ESI coverage. When assessing affordability, however, the provision is unclear whether to consider the cost of individual coverage for the employee alone or the cost of family coverage. The Internal Revenue Service interprets the statute on the basis of individual coverage, which is much cheaper than family coverage. Due to this so‐called family glitch, a significant number of low‐ to moderate‐income individuals—2–4 million according to various estimates—may be denied financial assistance (Brooks 2014).

Effect of the Individual Mandate

The individual mandate is intended to attract new enrollees, increase the number of insured, diversify risk pools, and lower premiums (Gruber 2011b). The CBO (2014) estimates that 4 million people will be penalized for violating the individual mandate in 2016 and about $4 billion will be collected in penalties. Sheils and Haught (2011) predict that nongroup premiums would increase by 12.6 percent and 7.8 million people would not have coverage without this mandate.

Participation and Competition in the Exchanges

Several studies focus on participation of (Abraham, Feldman, and Simon 2014; CMS 2014; GAO 2014a) and competition among (Cox et al. 2014; Swartz, Hall, and Jost 2015) insurers in the exchanges. Among the incumbent insurers in 2012, 10 percent participated in the marketplace in 2014—depending on presence in the region, size, and whether the insurer had prior experience in the group market (Abraham, Feldman, and Simon 2014). As the ACA matures, participation may increase further—25 percent more insurance companies joined the marketplace in 2015 than in 2014 (CMS 2014).

Competition in state‐sponsored exchanges varies considerably both within and across states (Cox et al. 2014; GAO 2014a; Kowalski 2014; Polsky et al. 2014; Dickstein et al. 2015; Swartz, Hall, and Jost 2015). Dickstein et al. (2015) reported that states can alter competition and market outcomes by how they define their coverage regions. In 2014, almost all state exchanges had multiple issuers, most included a mix of large and small companies, and more populous states usually had a wider selection of plans (GAO 2014a). An average of 37.3 plans were available through exchanges in urban counties compared to 25.7 plans in rural counties (Barker et al. 2014b). As the ACA restricts the ability of insurance companies to alter their risk pool, they compete instead by offering different cost‐sharing arrangements, benefits, and provider networks (Swartz, Hall, and Jost 2015). Furthermore, incentives may remain to restrict or ration care for some higher cost patients (McGuire et al. 2014). To protect consumers from the risks associated with “narrow network plans,” 27 states established quantitative standards for network adequacy and governmental oversight is expected to increase over time (Giovannelli, Lucia, and Corlette 2015).

Employer Mandate and the ESI System

One of the overarching questions about the ACA is how it will impact ESI, and whether the vast majority of workers will continue to obtain health insurance via their workplace. Recent studies indicate an absence of major changes in ESI since the ACA has gone into effect (Claxton et al. 2014a; Blavin et al. 2015). In 2014, the proportion of employers offering ESI (55 percent) and the average annual premium for individual coverage therein ($6,025) were similar to those in 2013 (Claxton et al. 2014a). Since 2003, premiums, deductibles, and employee contributions for ESI have gradually increased, but at a slower rate starting in 2010 (Collins et al. 2014a; Schoen, Radley, and Collins 2015). Note that these preliminary findings are based on partial implementation of the employer mandate. Thus, additional research is needed to evaluate whether these trends persist as the employer mandate and associated penalties go into full effect in 2016.

The Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP)

As of June 2014, 18 state‐based SHOP marketplaces enrolled 76,000 individuals from 12,000 small employers, and premiums for SHOP plans were similar to those for other small‐group plans (GAO 2014b). Gabel et al. (2013) surveyed small firms and found the majority favored several SHOP features. However, participation in SHOP is lower than expected due to a number of challenges (GAO 2014b). Some employers believe the small business tax credit, intended as an incentive to use SHOP, is too limited in its scope and requires a complex application process (Blumberg and Rifkin 2014; GAO 2014b). Initial participation in SHOP was also hampered by technical problems with the website, lack of awareness about the program, and limited involvement by brokers (Blumberg and Rifkin 2014; GAO 2014b). Moving forward, it is unclear whether small businesses will embrace this feature of the ACA, especially as some employers consider other options to provide coverage, such as private insurance exchanges or continued reliance on grandfathered, noncompliant plans (Blumberg and Rifkin 2014).

Medicaid Expansion

Although provisions for full Medicaid expansion did not take effect until 2014, California, Connecticut, Minnesota, and Washington, DC began early enrollment in 2010. Sommers, Kenney, and Epstein (2014) found a steady increase in Medicaid enrollment in these states, with the highest take‐up among those with health limitations. Potential Medicaid beneficiaries are generally healthier than those who are already enrolled, but those with chronic conditions are less likely than existing enrollees to have the disease(s) under control (Decker et al. 2013). As of September 2015, 30 states and Washington, DC had implemented Medicaid expansion and 20 chose not to participate (KFF 2015). Expansion decision is heavily influenced by political factors as well as state economic conditions, administrative capabilities, and prior policies toward low‐income residents and the uninsured (Jacobs and Callaghan 2013). An estimated 3.7 million adults in nonexpansion states are in the “coverage gap,” with low‐income blacks disproportionately affected (Artiga, Stephens, and Damico 2015). This means they earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to be eligible for premium tax credits in the marketplace.

The availability of coverage affects access and health outcomes of Medicaid beneficiaries (Artiga, Rudowitz, and Ranji 2015; Kaufman et al. 2015; Sommers et al. 2015). According to the 2014 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (Collins et al. 2015b), 78 percent of adults who have used their newly gained Medicaid coverage to obtain care said “they would not have been able to access or afford this care before.” Another study found that new coverage led to increases in the number of diabetes diagnoses for Medicaid patients (Kaufman et al. 2015). Sommers et al. (2015) found the proportion of low‐income adults with difficulties accessing a physician and medication decreased more in Medicaid expansion states than in nonexpansion states.

Frequent eligibility changes or “churning” is an ongoing concern in all states as individuals’ incomes vary and they transition to and from Medicaid, the marketplace, possibly ESI, and no coverage (Rosenbaum et al. 2014; Sommers et al. 2014b). Low‐income adults in nonexpansion states are particularly vulnerable to being uninsured (Collins et al. 2015b) or incurring high out‐of‐pocket costs in the marketplace (Hill 2015). Eventually, states will need to address churning, which has implications for tax credits, continuity of care, and health outcomes (Rosenbaum et al. 2014).

A group of studies have focused on providers’ experiences with expanding Medicaid (Angier et al. 2015; Cunningham, Garfield, and Rudowitz 2015; KFF and CF 2015). Ascension Health, the largest nonprofit health system in the United States, had more Medicaid discharges and revenues, and lower cost of care for the poor in expansion states. In other states, however, they experienced only a small increase in Medicaid discharges, a decrease in Medicaid revenue, and higher cost of care for the poor (Cunningham, Garfield, and Rudowitz 2015). Provider participation in public insurance programs has been an ongoing concern as some physicians are reluctant to accept Medicaid beneficiaries due to low reimbursement rates (Polsky et al. 2015). Following a temporary increase in Medicaid payments to providers during 2013–2014, the availability of primary care appointments increased for Medicaid enrollees, while wait times for new appointments remained the same (Polsky et al. 2015). A survey of primary care providers shows that the proportion accepting new Medicaid patients in 2015 is similar to that in 2011–2012 (KFF and CF 2015). A majority of providers surveyed, however, saw an increase in uninsured or Medicaid patients in expansion states without negatively affecting the quality of care (KFF and CF 2015).

Insurance Premiums, Health Care Expenditures, and Government Budgets

Health Insurance Premiums

Premiums continue to increase faster than median family income, leading more individuals to opt for high–deductible plans (Collins et al. 2014a; Schoen, Radley, and Collins 2015). While certain provisions of the ACA are likely to increase premiums (e.g., expansion of dependent coverage, extended benefits, ban on charging more for preexisting conditions), other features (e.g., restrictions on administrative costs and profits for insurance companies, risk‐sharing programs, individual mandate, competition in the marketplace) are expected to have the opposite effect (Blumenthal and Collins 2014; Collins et al. 2014a; Cox et al. 2015; Schoen, Radley, and Collins 2015). Overall, average premiums and spending by private health insurers in 2014 were lower than projected (Skopec and Kronick 2013). Average annual growth in premiums per enrollee for all private health insurance was 2.1 percent in 2013 and is projected to be 5.4 percent in 2014 and 2.8 percent in 2015 (Keehan et al. 2015). Insurers requesting large rate increases primarily attributed the change to higher prices for services and certain ACA requirements such as new taxes (McCue and Hall 2015). Even if premiums continue to gradually increase, most individuals are expected to receive expanded insurance benefits, and out‐of‐pocket costs may actually decline for those who are eligible for tax credits (Hill 2012; Keehan et al. 2015).

Health Care Expenditures

In recent years, national health care spending slowed from the relatively high growth rates experienced during the 1990s and early 2000s, averaging 4.0 percent annually over the 2008–2013 period (Chandra, Holmes, and Skinner 2013; Dranove, Garthwaite, and Ody 2014; Keehan et al. 2015). Nevertheless, the portion of GDP spent on health care is expected to increase from 17.4 percent in 2013 to 19.6 percent in 2024 (Keehan et al. 2015). Health care spending is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.8 percent over the period of 2014–2024, and much of this increase may be driven by the ACA's coverage expansions as well as higher prescription drug spending, a stronger economy, and an aging population (Keehan et al. 2015).

The expansion of insurance coverage under the ACA is expected to increase utilization of primary care and other services (Dall et al. 2013). The ACA includes a number of different approaches that have the potential to control rising health care expenditures, such as reducing medical errors, creating exchanges, taxing high cost insurance plans, and adjusting provider reimbursements (Gruber 2011a). It is too soon, however, to fully evaluate whether or to what extent these cost control measures will impact prices and utilization (Chandra, Holmes, and Skinner 2013; Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum 2015). Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum (2015) asserted that the ACA may be contributing to slower health care spending growth and, at a minimum, has not led to a rapid increase in spending.

Budgetary Effects of the ACA

As individuals with chronic diseases enroll in Medicaid and gain access to health services, overall health care utilization and spending will likely increase, creating challenges for state budgets. The latest estimates indicate that Medicaid spending increased 12 percent and enrollment increased 12.9 percent in 2014 (Keehan et al. 2015). Federal contributions cover all expansion costs during the first 3 years, which will benefit providers and generate economic activity (Holahan, Buettgens, and Dorn 2013). State budgets may be more strained later on, when they are required to fund more of the expansion. Even so, decreases in uncompensated care are expected to offset some of spending increases associated with Medicaid expansion. Overall, studies present evidence that expanding Medicaid is financially prudent for most states (Holahan, Buettgens, and Dorn 2013; Bachrach, Boozang, and Glanz 2015).

Due to its major role in Medicaid expansion and the establishment of health insurance exchanges, the federal government will end up financing a larger proportion of health care than before the ACA (Keehan et al. 2015). The actual estimate depends on the number of states participating in Medicaid expansion and a number of other factors. Changes in ESI also need to be taken into account as reductions in ESI coverage could increase federal tax receipts. However, this revenue increase could be offset by higher wages, which generate tax revenues but also lead to higher social security spending. Overall, the CBO (2015a) estimates that federal deficits will grow to $137 billion from 2016 to 2025 if the ACA were repealed.

Discussion and Opportunities for Future Research

Opportunities abound for researchers to study the most sweeping health care legislation in recent U.S. history. Results from this current systematic review highlight gaps in the existing literature and can serve as a resource for researchers considering where additional work is needed. Studies so far clearly show that the ACA has led to expansions in insurance coverage and improved access to care, especially among young adults, the relatively poor, less healthy populations, and minorities. With the exception of the dependent coverage provision, most investigations of the ACA so far are descriptive in nature, and rigorous study designs are needed to provide more convincing empirical evidence. In addition, further research is required to demonstrate the full impact of the ACA on health care prices, utilization, and perhaps most important, health outcomes.

The findings so far clearly establish areas for future investigation. For example, given that young adults have different health behaviors and health care needs than older adults, it is unknown whether the results for young adults are generalizable to the rest of the nonelderly population. Our review also identified a number of studies related to delivery reforms, workforce issues, and insurance company regulations, but due to the preliminary stage of these inquiries, we chose to exclude them from our analysis.

Augmenting and improving the existing studies will provide a deeper understanding of insurance expansions such as the composition of risk pools, the type of health care (e.g., acute, chronic, preventive, emergency, hospital, diagnostic services) some of the newly insured receive, and the quality of care therein. Going forward, out‐of‐pocket costs associated with the new plans purchased in marketplaces will need to be tracked. How will narrow provider networks affect consumer satisfaction and outcomes? In the aggregate, health care expenditures have moderated recently, but is this a temporary trend and to what extent it can be attributed to the ACA? More rigorous analyses and study designs, rather than simply reporting descriptive statistics, are needed to control for factors such as economic trends and geographic variation, which will permit further investigation of mechanisms underlying changes and trends in prices, utilization, and cost.

Other questions require better data and longer follow‐up periods. What happens to ESI as employer penalties go into full effect? What will the labor market implications be? How do eventual changes in premiums and health care expenditures compare to initial projections? How will federal and state health care expenditures change if more states expand Medicaid? Lastly, the legislative process has largely stalled when it comes to identifying and fixing inefficiencies in the ACA (e.g., family glitch). How will the political process evolve after the 2016 election year?

Studies in the gray literature often present results from surveys of specific populations (e.g., low‐income adults, women) or longitudinal surveys that track changes in coverage, costs, and attitudes toward reforms (e.g., Doty, Rasmussen, and Collins 2014; Hamel et al. 2014; Collins et al. 2015b). Analyses of large and nationally representative datasets will be necessary to substantiate findings from earlier preliminary studies. Both private and federal surveys as well as administrative data sources have limitations, so it is encouraging that several new initiatives are underway to collect better data pertaining to the ACA (Claxton et al. 2014b). An example is the Commonwealth Fund's joint program with the University of Chicago to track premiums, deductibles, and other features of health insurance plans (Whitmore et al. 2014). Such initiatives are critical as many of the compelling research questions related to the long‐term effects of the ACA require better data, rigorous research designs, and more time. Although many questions about the ACA remain unanswered, especially regarding costs and outcomes, it is clear that the ACA has accomplished two of its main goals—decreasing the number of uninsured and improving access to care.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: We gratefully acknowledge two anonymous referees and Theodore Ganiats, M.D., for their constructive comments and suggestions on earlier versions of the paper. We also thank Joanna Faley for research assistance and Carmen Martinez for administrative support.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

Notes

A more comprehensive and detailed description of the ACA's provisions is available from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and the Commonwealth Fund (CF).

While not the focus here, the provisions related to improving the delivery of health care are important components of the ACA and have the potential to significantly influence both the cost and quality of care. See Blumenthal, Abrams, and Nuzum (2015) for a progress report on the ACA's health care delivery reforms.

Eligibility for tax credits depends on whether the employer coverage meets two tests: (1) Is it affordable (i.e., the individual employee premium for the least expensive plan offered must be less than 9.5 percent of family income)? (2) Does it meet the minimum value (i.e., is it designed to pay 60 percent of total medical costs for a population)? (HHS 2014).

References

- Abraham, J. M. , Feldman R., and Simon K.. 2014. “Did They Come to the Dance? Insurer Participation in Exchanges.” American Journal of Managed Care 20 (12): 1022–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akosa Antwi, Y. , Moriya A. S., and Simon K. I.. 2013. “Effects of Federal Policy to Insure Young Adults: Evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act's Dependent‐Coverage Mandate.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5 (4): 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Akosa Antwi, Y. , Moriya A. S., and Simon K. I.. 2015. “Access to Health Insurance and the Use of Inpatient Medical Care: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act Young Adult Mandate.” Journal of Health Economics 39: 171–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akosa Antwi, Y. , Moriya A. S., Simon K., and Sommers B. D.. 2015. “Changes in Emergency Department Use among Young Adults after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's Dependent Coverage Provision.” Annals of Emergency Medicine 65 (6): 664–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angier, H. , Hoopes M., Gold R., Bailey S. R., Cottrell E. K., Heintzman J., Marino M., and DeVoe J. E.. 2015. “An Early Look at Rates of Uninsured Safety Net Clinic Visits after the Affordable Care Act.” The Annals of Family Medicine 13 (1): 10–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artiga, S. , Rudowitz R., and Ranji U.. 2015. How Have State Medicaid Expansion Decisions Affected the Experiences of Low‐Income Adults? Perspectives from Ohio, Arkansas, and Missouri. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief [accessed on March 1, 2016]. Available at http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/how-have-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-affected-the-experiences-of-low-income-adults-perspectives-from-ohio-arkansas-and-missouri/ [Google Scholar]

- Artiga, S. , Stephens J., and Damico A.. 2015. The Impact of the Coverage Gap in States Not Expanding Medicaid by Race and Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief [accessed on October 8, 2015]. Available at http://kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/the-impact-of-the-coverage-gap-in-states-not-expanding-medicaid-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach, D. , Boozang P., and Glanz D.. 2015. States Expanding Medicaid See Significant Budget Savings and Revenue Gains. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Issue Brief [accessed March 1, 2016]. Available at http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2015/04/states-expanding-medicaid-see-significant-budget-savings-and-rev.html [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresco, S. , Courtemanche C. J., and Qi Y.. 2015. “Impacts of the Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Provision on Health‐Related Outcomes of Young Adults.” Journal of Health Economics 40: 54–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellos, S. H. , Wuppermann A. C., Carman K. G., Bauhoff S., McFadden D. L., Kapteyn A., Winter J. K., and Goldman D.. 2014. “Preparedness of Americans for the Affordable Care Act.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (15): 5497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker, A. R. , McBride T. D., Kemper L. M., and Mueller K.. 2014a. Geographic Variation in Premiums in Health Insurance Marketplaces. RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis; Rural Policy Brief no. 2014‐10 [accessed on October 8, 2015]. Available at http://www.public-health.uiowa.edu/rupri/publications/policybriefs/2014/Geographic%20Variation%20in%20Premiums%20in%20Health%20Insurance%20Marketplaces.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker, A. R. , McBride T. D., Kemper L. M., and Mueller K.. 2014b. A Guide to Understanding the Variation in Premiums in Rural Health Insurance Marketplaces. RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis; Rural Policy Brief no. 2014‐5 [accessed on October 8, 2015]. Available at http://cph.uiowa.edu/rupri/publications/policybriefs/2014/Rural%20HIM.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blavin, F. , Shartzer A., Long S. K., and Holahan J.. 2015. “An Early Look at Changes in Employer‐Sponsored Insurance under the Affordable Care Act.” Health Affairs 34 (1): 170–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg, L. J. , and Rifkin S.. 2014. Early 2014 Stakeholder Experiences with Small‐Business Marketplaces in Eight States. The Urban Institute; [accessed on October 8, 2015]. Available at http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/413204-Early-Stakeholder-Experiences-with-Small-Business-Marketplaces-in-Eight-States.PDF [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal, D. , Abrams M., and Nuzum R.. 2015. “The Affordable Care Act at 5 Years.” New England Journal of Medicine 372 (25): 2451–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal, D. , and Collins S. R.. 2014. “Health Care Coverage under the Affordable Care Act—A Progress Report.” New England Journal of Medicine 371 (3): 275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon, W. P. , and Carnes K.. 2014. “Federal Health Insurance Reform and ‘Exchanges’: Recent History.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 25 (1): xxxii–lvii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, T. 2014. “Health Policy Brief: The Family Glitch.” Health Affairs [accessed on December 10, 2014]. Available at http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_129.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Busch, S. H. , Golberstein E., and Meara E.. 2014. “ACA Dependent Coverage Provision Reduced High Out‐of‐Pocket Health Care Spending for Young Adults.” Health Affairs 33 (8): 1361–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, J. C. , Monheit A. C., DeLia D., and Lloyd K.. 2012. “Early Impact of the Affordable Care Act on Health Insurance Coverage of Young Adults.” Health Services Research 47 (5): 1773–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D. L. , Lennox Kail B., Lynch J. L., and Dreher M.. 2014. “The Affordable Care Act, Dependent Health Insurance Coverage, and Young Adults’ Health.” Sociological Inquiry 84 (2): 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] . 2014. “CMS Releases New Data Demonstrating Increased Choice, Competition in the Health Insurance Marketplace in 2015” [accessed October 8, 2015]. Available at http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2014-Press-releases-items/2014-11-14.html

- Chandra, A. , Holmes J., and Skinner J.. 2013. “Is This Time Different? The Slowdown in Health Care Spending.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2013 (2): 261–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua, K. P. , and Sommers B. D.. 2014. “Changes in Health and Medical Spending among Young Adults under Health Reform.” Journal of the American Medical Association 311 (23): 2437–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton, G. , Rae M., Panchal N., Damico A., Whitmore H., Kenward K., and Osei‐Anto A.. 2012. “Health Benefits in 2012: Moderate Premium Increases for Employer‐Sponsored Plans; Young Adults Gained Coverage under ACA.” Health Affairs 31 (10): 2324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton, G. , Rae M., Panchal N., Whitmore H., Damico A., and Kenward K.. 2014a. “Health Benefits in 2014: Stability in Premiums and Coverage for Employer‐Sponsored Plans.” Health Affairs 33 (10): 1851–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton, G. , Levitt L., Brodie M., Garfield R., and Damico A.. 2014b. Measuring Changes in Insurance Coverage under the Affordable Care Act. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief [accessed on March 1, 2016]. Available at http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/measuring-changes-in-insurance-coverage-under-the-affordable-care-act/ [Google Scholar]