Abstract

Soils are facing new environmental stressors, such as titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs). While these emerging pollutants are increasingly released into most ecosystems, including agricultural fields, their potential impacts on soil and its function remain to be investigated. Here we report the response of the microbial community of an agricultural soil exposed over 90 days to TiO2-NPs (1 and 500 mg kg−1 dry soil). To assess their impact on soil function, we focused on the nitrogen cycle and measured nitrification and denitrification enzymatic activities and by quantifying specific representative genes (amoA for ammonia-oxidizers, nirK and nirS for denitrifiers). Additionally, diversity shifts were examined in bacteria, archaea, and the ammonia-oxidizing clades of each domain. With strong negative impacts on nitrification enzyme activities and the abundances of ammonia-oxidizing microorganism, TiO2-NPs triggered cascading negative effects on denitrification enzyme activity and a deep modification of the bacterial community structure after just 90 days of exposure to even the lowest, realistic concentration of NPs. These results appeal further research to assess how these emerging pollutants modify the soil health and broader ecosystem function.

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs) are widely used in commercial products such as sunscreens and toothpastes, industrial products like paints, lacquers and paper, and in photocatalytic processes such as water treatment1,2,3,4. Consequently, TiO2-NPs are indirectly discharged in agricultural soils through irrigation or sewage-sludge application5 and directly as nanofertilizers or nanopesticides6. Despite their importance in soil ecosystem function, the current literature lacks thorough investigations of the effect of TiO2-NPs on soil microbial communities7.

Microbial communities play key roles in plant productivity and in biogeochemical processes8,9,10,11, such as the nitrogen (N) cycle, in which nitrification and denitrification processes control soil inorganic N availability and subsequent soil fertility10. The strong coupling between nitrification and denitrification makes the N cycle an ideal model to study the impacts of environmental disturbances on microbial functioning. Despite the recent descriptions of complete single-organism oxidation from ammonium (NH4+) to nitrate (NO3−) in some members of the Nitrospira genus12,13, nitrification is usually considered a two-step aerobic process. The current paradigm is that the rate-limiting step in nitrification is the oxidation of NH4+ into nitrite (NO2−)14, performed by both ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA)15. Nitrification is carried out by a group of microorganisms exhibiting a low phylogenetic diversity and is one of the most sensitive soil microbial processes to environmental perturbations, such as pollutant exposure16,17. In contrast to the impacts on AOB function, the influence of environmental stressors on AOA is less known18,19 as they were only recently identified as pivotal in soil nitrification20.

Under anaerobic conditions, nitrite and/or nitrate can be sequentially reduced into gaseous products (NO, N2O and N2)21 during the denitrification process. Contrarily to nitrification, the ability to perform denitrification is widespread among several phylogenetic groups and this functional guild has been shown to be moderately insensitive to some toxicants22. However, the sensitivity of denitrifiers to TiO2-NPs has not been investigated. Moreover, despite a potential resistance of the denitrifiers to this pollutant, a failure of nitrification may still impose scaffolding impacts resulting in decreased denitrification.

Some studies observed decreased overall microbial respiration and enzyme activity in soils exposed to high TiO2-NPs concentrations23,24,25. However, the targeted impact of TiO2-NPs on the N cycle, regulated by microbial communities of varying degrees of functional redundancy, has not been investigated in soils.

Here we report the effects of TiO2-NPs on an agricultural soil (silty-clay texture) subjected to a 90 d exposure of two TiO2-NPs concentrations, simulating either an environmentally realistic contamination (1 mg kg−1 dry soil) or an accidental pollution (500 mg kg−1 dry soil)26. A previous study demonstrated that among six soils of varying degrees of texture and organic matter content, silty-clay soil presented the highest effects of TiO2-NPs on soil respiration due to the lower stability of NP aggregates in the soil solution25. To further investigate the impact of TiO2-NPs on soil function, we examined their effects on nitrification and denitrification enzymatic activities (NEA and DEA, respectively), along with the quantification of the representative genes of the functional guilds performing these activities by quantitative PCR (i.e. amoA for ammonia-oxidizers and nirK and nirS for denitrifiers). Additionally, the effects of TiO2-NPs on the microbial diversity was determined by targeting the 16S rDNA bacterial and archaeal genes and amoA AOA and AOB genes with high throughput sequencing (MiSeq, Illumina). We developed a path analysis to integrate the different variables measured in our experiment to assess the multifaceted consequences of TiO2-NPs on the N cycle in an agricultural soil.

Results

Impact of TiO2-NPs on soil function

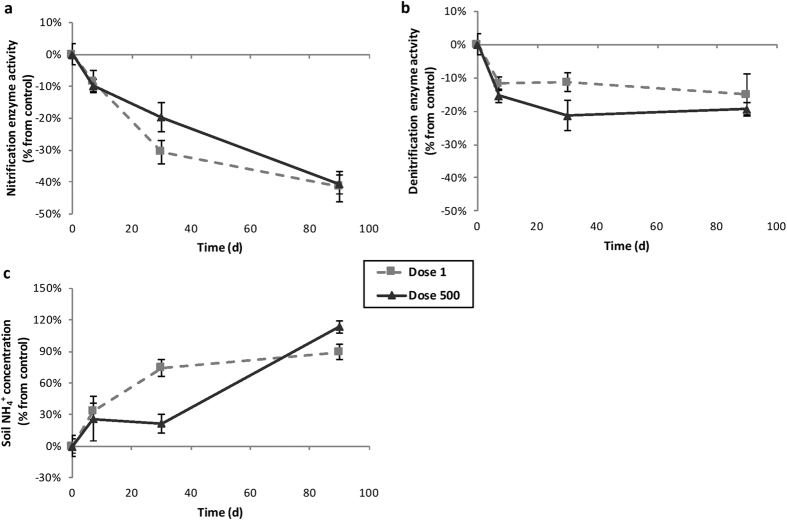

NEA and DEA were monitored after 0, 7, 30 and 90 d of incubation. As expected after 90 d in a microcosm experiment, NEA and DEA decreased over time in the controls (−17% and −16%, respectively, Fig. S1). The impacts of TiO2-NPs exposures were therefore considered as percentage relative to the controls.

After 30 d of exposure, both TiO2-NPs concentrations reduced NEA compared to the control with 31% decrease (P < 0.001) and 20% (P = 0.02) for 1 and 500 mg kg−1, respectively (Fig. 1a). These reductions were more pronounced after 90 days with about 40% decrease (P < 0.001) for both concentrations. The inhibiting effect of TiO2-NPs on NEA triggered a significant accumulation of NH4+ after 30 d for 1 mg kg−1 (Fig. 1c, +74%, P = 0.01) and for both concentrations after 90 d (1 mg kg−1: +89%, P < 0.001; 500 mg kg−1: +113%, P = 0.001). Moreover, soil NH4+ concentration was negatively correlated to NEA after 30 (r = 0.57, P = 0.01) and 90 d (r = 0.83, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Changes over time of NEA (a), DEA (b,c) soil NH4+ concentration in the different treatments (dash line: Dose 1 mg kg−1, black line: Dose 500 mg kg−1 dry soil). Results are expressed as percentage relative to the controls and error bars represent the standard error (n = 6).

DEA significantly decreased on the 3 sampling dates with 500 mg TiO2-NPs kg−1 (Fig. 1b, 7 d: −15%, P = 0.01; 30 d: −21%, P = 0.04; 90 d: −19%, P < 0.001). The soil exposure with 1 mg kg−1 resulted in a significant reduction of DEA only after 90 d of incubation (−15%, P < 0.001).

Impact of TiO2-NPs on N-related functional guild abundances

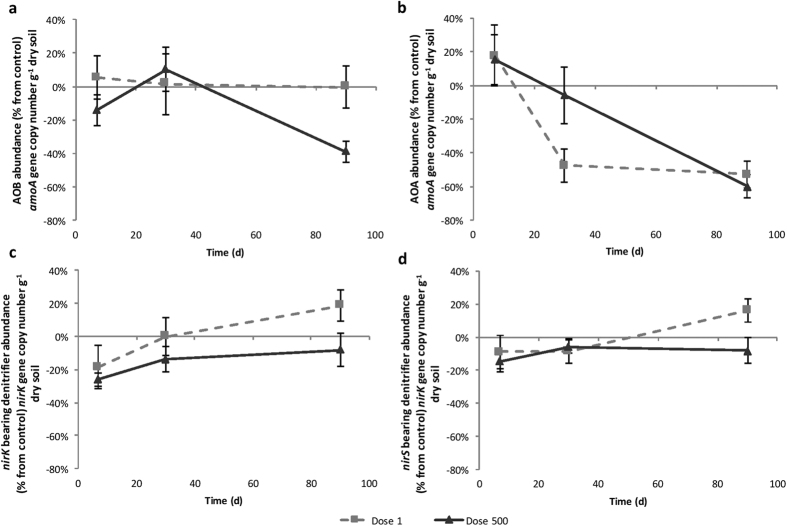

Overall, the abundance of amoA AOA gene was 75 fold higher than corresponding amoA AOB abundance (average AOA and AOB: 9.27 × 107 and 1.25 × 106 copies g−1 dry soil, respectively). The dynamics of amoA AOA and AOB under TiO2-NP treatments were contrasted (Fig. 2): while the soil exposure at 500 mg kg−1 TiO2-NPs lead to a decrease of amoA AOB abundance only after 90 d (Fig. 2a, −39%, P = 0.05), no variation was observed at 1 mg kg−1 during the course of the experiment. On the contrary, the abundance of amoA AOA strongly decreased regardless of the applied concentration after 90 d (Fig. 2b, 1 mg kg−1: −53%, P < 0.001; 500 mg kg−1: −60%, P < 0.001). NEA was negatively correlated with the abundance of amoA AOB (r = 0.42, P = 0.002, Table 1). In contrast, NEA was positively correlated with the abundance of amoA AOA (r = 0.51, P < 0.001, Table 1). In addition, soil NH4+ concentration was strongly negatively correlated with amoA AOA abundance after 90 d (r = 0.88, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Changes over time of (a) ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB), (b) ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA), (c) nirK bearing denitrifier abundance and (d) nirS bearing denitrifier abundance in the different treatments (dash line: Dose 1 mg kg−1, black line: Dose 500 mg kg−1 dry soil). Results are expressed as percentage relative to the controls and error bars represent the standard error (n = 6).

Table 1. Correlation table between the different measured variables (AOB abundance, AOA abundance, nirK abundance, nirS abundance, NEA and DEA).

| AOB | AOA | nirK | nirS | NEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOB | |||||

| AOA | 0.06 (0.69) | ||||

| nirK | 0.04 (0.79) | −0.02 (0.94) | |||

| nirS | 0.22 (0.11) | 0.27 (0.03) | −0.17 (0.20) | ||

| NEA | −0.43 (0.002) | 0.51 (<0.001) | 0.35 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.97) | |

| DEA | −0.39 (0.004) | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.53 (<0.001) | −0.08 (0.69) | 0.68 (<0.001) |

The strength of the linear relationship is given by the correlation coefficient r, P-values are given in parenthesis. Significant correlations are presented in bold. Spearman correlations were investigated on all data of the 3 sampling times (n = 54).

The abundance of nirS gene was 4.5 fold higher than the abundance of nirK, with an average of 1.15 × 107 and 2.57 × 106 copies g−1 dry soil, respectively. The nirK and nirS gene abundances were not significantly impacted by TiO2-NPs exposure (Fig. 2c,d). DEA was not correlated to the abundance of nirS but was positively correlated with the abundance of nirK (R2 = 0.28, P < 0.001, Table 1).

Impact of TiO2-NPs on soil microbial diversity

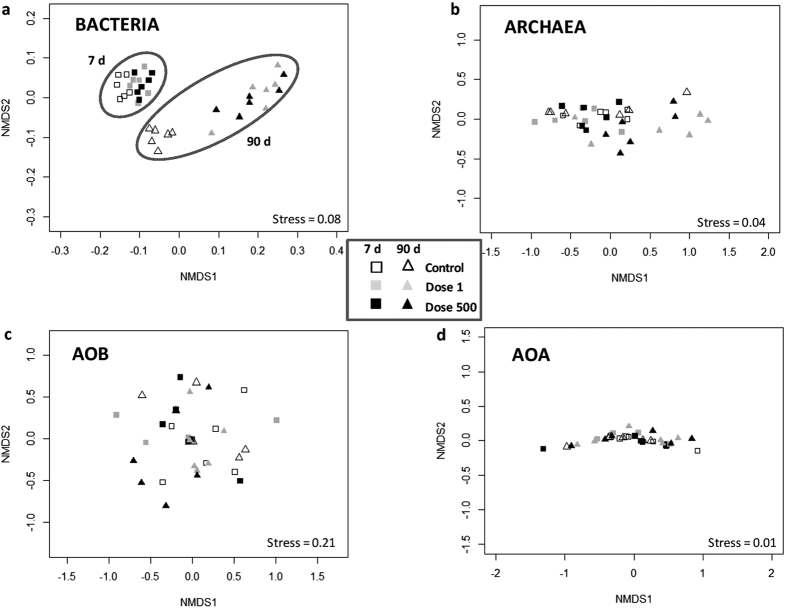

We assessed the impact of TiO2-NPs on soil microbial diversity by sequencing the 16S rDNA and amoA bacterial and archaeal genes (Table 2). The sequencing effort results in 160,301 16S rDNA bacterial sequences comprising 8,256 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) (per soil sample: 1,466 ± 8.85 OTUs) at a distance dissimilarity of 0.03. No significant change in 16S rDNA richness (ACE estimator) was observed among the soil samples. However, the TiO2-NPs exposure dosage and the time of exposure, as well as the interaction between these parameters, caused a significant shift in the bacterial community structure (TiO2-NPs: P < 0.001, time: P < 0.001, TiO2-NPs × time: P = 0.005, Fig. 3a). Both doses of TiO2-NPs significantly modified the bacterial community structure (1 mg kg−1: P = 0.001, 500 mg kg−1: P = 0.003) after 90 d and the relative abundance of several OTUs was either reduced (e.g. Acidobacteria group 6, Saprospirae) or increased (e.g. Sulfuritalea, Anaerolinea, Bacteroidia) compared to the control (Fig. S2). After 90 d, the shift observed in the bacterial community structure was associated with a modification of the relative abundance of different phyla, in particular the Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria and Chloroflexi phyla (Fig. S3).

Table 2. Main information on the diversity analysis of bacterial, archaeal, AOB and AOA communities.

| Community(Gene) | Primers | Mean Fragment size | Mean sequence number per sample | Total sequence number analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria (16S rDNA) | 515F/806R (V4 Region) | 300 bp | 4580 ± 166 | 160301 |

| Archaea (16S rDNA) | 349F/806R (V3-V4 Region) | 424 bp | 5745 ± 3332 | 206831 |

| AOB (amoA) | amoA_1F/amoA_2R | 435 bp | 11745 ± 451 | 422844 |

| AOA (amoA) | CrenamoA23F/CrenamoA616R | 252 bp | 16929 ± 9545 | 609456 |

Figure 3.

Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) analysis to determine the modification in microbial community structure in presence of TiO2-NPs (white: Control, grey: Dose 1, black: Dose 500) after 7 d (square symbols) and 90 d (triangle symbols): (a) bacterial community, (b) archaeal community, (c) AOB community, (d) AOA community.

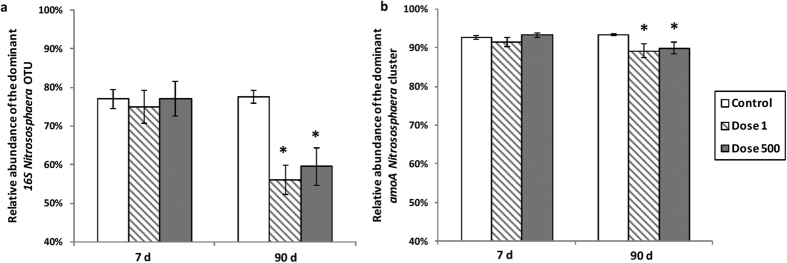

The archaeal community diversity, also inferred from the 16S rDNA gene, had low richness with a total of 364 OTUs (per soil sample: 28.75 ± 0.91 OTUs) from 206,831 archaeal sequences delineated at a dissimilarity distance of 0.03. The archaeal communities were universally dominated by a single OTU, with a relative abundance of 70.4 ± 2%. This ubiquitous OTU belongs to an ammonia-oxidizing archeon of the genus Nitrososphaera (Fig. S4). The archaeal community structure was modified over time (P = 0.002, Fig. 3b), but no community changes were detected with TiO2-NP exposure treatments (P = 0.34). The relative abundance of the dominant Nitrososphaera OTU was significantly reduced in the microcosms exposed to both concentrations of TiO2-NPs after 90 d (1 mg kg−1: −28%, P < 0.001; 500 mg kg−1: −23%, P < 0.001, Fig. 4a). Interestingly, the relative abundance of this OTU was positively correlated to the abundance of amoA AOA (r = 0.89, P < 0.001) and to NEA (r = 0.62, P = 0.02). After 90 d under TiO2-NP exposure, while the relative abundance of the dominant Nitrososphaera OTU decreased, the relative abundance of a Methanocella OTU increased by >11.5% (from 0.3 ± 0.08% in the control to 12 ± 3%) as a result of TiO2-NPs exposure (Fig. S4).

Figure 4.

Effects of TiO2-NPs on the relative abundance (a) of the dominant archaeal 16S rDNA OTU affiliated to the Nitrososphaera genus, (b) of the dominant AOA amoA cluster affiliated to the Nitrososphaera cluster. The mean and standard errors are presented (n = 6) and the treatments are represented as: white bars: Control, hashed bars: Dose 1 mg kg−1, dark grey bars: Dose 500 mg kg−1 dry soil.

The 422,844 amoA AOB gene sequences clustered into 5974 total observed clusters (per soil sample: 272 ± 2.5 clusters) at a dissimilarity of 0.05. The ACE richness estimator of the AOB community significantly decreased after 90 d in presence of 500 mg kg−1 of TiO2-NPs (−8.4%, P = 0.004). However, the AOB community structure did not vary among TiO2-NP treatments throughout the incubation (TiO2-NPs: P = 0.68, time: P = 0.21, Fig. 3c).

The 609,456 amoA AOA gene sequences yielded 2,103 total clusters (per soil sample: 44 ± 8 clusters) at a dissimilarity of 0.05. The AOA community structure assessed by amoA AOA gene sequences was neither modified when exposed to TiO2-NPs nor during the incubation (TiO2-NPs: P = 0.95, time: P = 0.31, Fig. 3d). As observed for the 16S rDNA, a single cluster belonging to Nitrososphaera cluster dominated the amoA AOA sequences in all samples, representing on average 91% of all amoA AOA sequences analyzed (Fig. S5). The other clusters obtained were also in the genus Nitrososphaera (Fig. S5). The relative abundance of the dominant amoA Nitrososphaera cluster was slightly decreased by TiO2-NP exposure after 90 d (Fig. 4b, −4%, P < 0.001 for both concentrations).

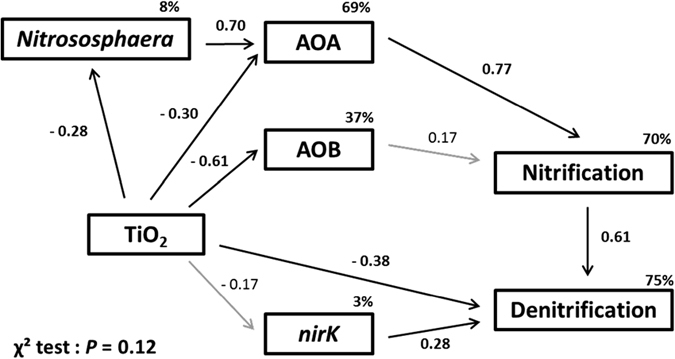

Path Analysis: Integrating the relationships among TiO2-NP exposure, microbial communities and soil function

We investigated possible causal relationships between TiO2-NPs exposure and microbial activity, abundance and diversity using a path analysis (Fig. 5). The path analysis was performed on the data set obtained after 90 d of exposure to TiO2-NPs since the greatest effects of TiO2-NPs on these soil microorganisms occurred at the 90 d sampling time (Figs 1 and 2). The variables included in the model were significantly correlated to NEA or DEA. The model explains a significant part of NEA (70%) and DEA (75%) variances. TiO2-NPs significantly and negatively affected the relative abundance of the dominant 16S rDNA OTU affiliated with Nitrososphaera (path coefficient = −0.28, P = 0.02) and also of amoA AOA and AOB overall gene abundances (path coefficient = −0.30, P = 0.03 and −0.61, P = 0.001 respectively). The dominant archaea Nitrososphaera was also an important driver of the AOA abundance (path coefficient = 0.70, P < 0.001). The path analysis supported the relative abundance of amoA AOA genes as the major driver of NEA in this soil (path coefficient = 0.77, P < 0.001) and the relative abundance of amoA AOB as a minor contributor to NEA (path coefficient = 0.17, P = 0.23). A large part of the variance of NEA was explained by indirect effects of the ubiquitous 16S rDNA Nitrososphaera OTU (indirect effect = 0.53). TiO2-NPs directly reduced DEA (path coefficient = −0.38, P = 0.007) but did not indirectly influence DEA through nirK relative abundance (indirect effects = −0.05) although nirK abundance was a driver of DEA (path coefficient = 0.28, P = 0.03). The model revealed that the DEA was mainly explained by the NEA activity (path coefficient = 0.61, P < 0.001). If the path between the NEA and the DEA was not included in the model, only 44% of DEA variance was explained (data not shown), emphasizing that TiO2-NP exposure strongly affects denitrification process through a decrease of AOA abundance and consequently NEA activity.

Figure 5. Path analysis of the direct and indirect effects of TiO2-NPs, dominant 16S rDNA Nitrososphaera sequence number, AOA abundance, AOB abundance, nirK abundance on NEA and DEA.

Path coefficients (values adjacent to the arrows) correspond to the standardized coefficients calculated based on the analysis of correlation matrices and indicate by how many standard deviations the effect variable would change if the causal variable was changed by one standard deviation. Arrows and values in bold indicate a significant causal relationship between two variables.

Discussion

TiO2-NPs impose strong perturbations of the nitrogen cycle and a modification of the bacterial community structure in an agricultural soil, even at low realistic concentration (1 mg kg−1 dry soil). Surprisingly, the two TiO2-NPs concentrations used (1 and 500 mg kg−1 dry soil) resulted in similar effects on the soil microbial activities and AOA abundance. Non classical dose-response seems to be rather common with NPs and has been observed several times on soil microbial activities24,25,27. The current hypothesis is that the NPs homo- and hetero-aggregation processes (i.e. the aggregation of NPs with themselves and the aggregation of NP with other environmental constituents) vary according to NP concentration at time of exposure28, resulting in variable NP bioavailability and toxicity for microorganisms29. Moreover, the initial particle size, coating and phase composition can affect NPs reactivity and aggregation29,30. Therefore, further research on the physicochemical properties of NPs in soils as it relates to the applied concentration is necessary to clarify this assumption.

No functional resilience was observed during the time course of the experiment, which raises concerns about the ecotoxicity of TiO2-NPs in soils. The greatest effects of TiO2-NPs appeared 90 d after the exposure suggesting that aged NPs can affect microorganisms even at low concentrations and after a long exposure. This should be considered with regards to transport experiments suggesting that TiO2-NPs exhibit a low mobility in soils and would have a long residence time in this ecosystem31,32. Most studies to date are based on shorter incubations no longer than 60 d and simulate exposures to exceptionally high NPs concentrations (>100 mg kg−1)7. Therefore, our results demonstrate that shorter-term experiments may not accurately reflect the toxic potential of NPs in soil over the long term, suggesting that further research should be conducted under more realistic NP concentrations and assessed over longer periods.

The AOA abundance was highly reduced by TiO2-NP exposure compared to the AOB abundance even with the lowest concentration. In this case, the AOA abundance decreased to 60% after 90 d, presumably explaining the high accumulation of NH4+ in soil. Consistent with Mertens et al.18, our results challenge the view that archaea are more tolerant to chronic stresses than bacteria33,34. The study of AOA ecology in soil and their response to environmental stressors is still largely unexplored yet is likely an important influence on soil health18,19,35,36,37. The response of archaea to metal oxide NPs was studied on waste activated sludge and consistent with our study, AOAs were more affected by NPs after long-term exposure38,39. Pure culture studies have shown that TiO2-NPs can be toxic to bacteria after adsorption to cell membrane causing oxidative stress associated to reactive oxygen species (ROS) production40,41 and osmotic stress42. However, the very limited knowledge of soil archaeal physiology and the absence of targeted toxicological studies on soil archaeal strains, prevent us to say that the same toxicity mechanisms are operating on the mortality of archaea and bacteria exposed to TiO2-NPs.

In this study, the archaeal diversity was very low compared to bacterial diversity and the most represented soil archaea (16S rDNA) and AOA (amoA) were affiliated with the same one Nitrososphaera phylotype. This observation is consistent with the literature reporting that this AOA is dominant in many agricultural and natural soils worldwide43,44,45,46. Interestingly, this dominant 16S rDNA Nitrososphaera OTU decreased with TiO2-NPs exposure (−28 and −23%) and was positively correlated to NEA and AOA abundance. In contrast, the relative abundance of the dominant amoA Nitrososphaera cluster was only slightly decreased by both doses (−4%). This result demonstrates that there is a lower level of diversity for amoA AOA genes than for 16S rDNA genes47 and suggests that TiO2-NPs affected taxonomically distinct AOA groups harboring similar amoA genes. Similarly, for AOB community, we did not observe any particular pattern of amoA AOB community structure despite substantial shifts in the bacterial community inferred from the 16S rDNA dataset.

Based on our results, we can assume that dominant AOA Nitrososphaera phylotypes are the main functional drivers of nitrification in the examined soil. This is supported by the positive correlations of AOA abundance with NEA but also by the negative correlation with soil NH4+ concentration and the much higher abundance of AOA which was 75 fold greater than AOB abundance. Higher abundance of AOA than AOB in soils exhibiting neutral or alkaline pH have been reported several times20,48. Our results confirm these observations and point out that AOA can dominate ammonia-oxidizing activity under alkaline pH and high organic matter content48,49,50,51,52. As illustrated by the path analysis, TiO2-NPs had negative effects on Nitrososphaera relative abundance and AOA abundance with cascading negative effects on nitrification and denitrification activities. Altogether, these results suggest the pivotal role of AOA Nitrososphaera in the response of this soil to TiO2-NP contamination exposure.

Unlike the nitrifying community, the abundance of the denitrifying community was not suppressed by TiO2-NP exposure, yet DEA decreased (around −20%) with both TiO2-NP concentrations during the incubation. The higher resistance and resilience of denitrifiers to pollutants is well supported and can be explained by their high functional redundancy, niche breadth and adaptive ability22. The path analysis indicated that decreased denitrification was primarily explained by indirect effects through TiO2-NP-mediated suppression of nitrification caused by a decrease of the AOA community. However, the decline of nitrification did not fully explain the denitrification decrease since TiO2-NPs also directly affected denitrification (path coefficient = −0.38). This path reflects that other variables that were not included in our model are likely involved in the decrease of DEA. As suggested by Cantarel et al.53, specific clusters of denitrifying bacteria could better be related to denitrification than functional gene abundance (nirK or nosZ)53.

Nanomaterials such as TiO2-NP are worrying emerging contaminants of terrestrial ecosystem. Their effects on soil function as well as on microbial diversity and abundance of key functional guilds are of particular interest for environmental risk assessment. Our results highlight the complexity of the effects that TiO2-NP exposure imposes on soil microorganisms and the N cycle. Considering the functional links and indirect effects on key players of the N cycle provides an integrative assessment of their impact on the soil microbial community and its function. Particularly, soil nitrification and ammonia-oxidation performed by AOA, justify more thorough examinations from both toxicological and environmental perspectives.

Methods

Nanoparticles, soil and experimental design

The TiO2-NPs (80% anatase, 20% rutile) were provided by Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, USA) with a particle size of 21 nm in powder and ≥99.5% purity. The aggregated size and surface charge of TiO2-NPs in water were previously characterized by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) using a NanoZS (Malvern)25. The average aggregated size and zeta potential of TiO2-NPs in the ultrapure water spiking suspension were 160 ± 7.2 nm and −13.4 ± 0.5 mV, respectively.

The soil was sampled from the upper 20 cm layer of a permanent pasture at Commarin (Côte d’Or, France), sieved (2 mm) and stored at 4 °C before use. It is a silty-clay soil comprised of 39.1% clay, 50.8% loam and 10.1% sand, with an organic matter content of 7.87%, Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) of 20.1 cmol+ kg−1 and the water content at field capacity was 51%. The soil pH (7.7) and the ionic strength (1.37 mM) were measured following ISO 10390 and ISO 11265 procedures, respectively. The pH was not modified by the addition of TiO2-NPs throughout the experiment (Data not shown).

The soil was exposed to one dose of 0 mg, 1 mg, or 500 mg kg−1 of TiO2-NPs suspended in ultrapure water and dispersed in an ultrasonic bath (Bioblock Scientific) for 5 min just before use. TiO2-NPs suspensions were added homogeneously using a multichannel pipette in order to achieve the water holding capacity. The soil was thoroughly mixed manually for 10 min to ensure a homogeneous distribution of NPs. Control soils received only ultrapure water to achieve the same final moisture. Fifty grams (equivalent dry weight) of contaminated soils were then placed into microcosms (150 ml plasma flask) and sealed with rubber stoppers. Soil microcosms were incubated for 7, 30 or 90 days at 28 °C in the dark and were weekly aerated to ensure a renewal of the atmosphere in the flasks. The experimental design consisted of 54 microcosms: 3 concentrations of TiO2-NPs (0, 1, 500 mg kg−1 dry soil) ×3 exposure times ×6 replicates per treatment. At the beginning of the experiment, six additional microcosms were prepared to assess the baseline conditions of the soil. For each incubation time, the microcosms were destructively harvested and soil subsamples were immediately assessed for NEA and DEA measurements, and 3 g were stored at −20 °C until DNA extraction.

Nitrification Enzymatic Activity (NEA) and soil NH4 + concentration

NEA was determined following the protocol described in Dassonville et al.54. Subsamples of fresh soil (3 g dry soil) were incubated with 6 ml of a solution of (NH4)2SO4 (50 μg N-NH4+ g−1 dry soil). Distilled water was added in each sample to achieve 24 ml of total liquid volume in flasks. The flasks were sealed with Parafilm® and incubated at 28 °C under constant agitation (180 rpm). 1.5 ml of soil slurry were regularly sampled after 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h of incubation, filtered through 0.2 μm pore size and stored in vials at −20 °C until measurement of NO3− concentrations using an ion chromatograph (DX120, Dionex, Salt Lake City, USA) equipped with a 4 × 250 mm column (IonPac AS9 HC). Based on the linear accumulation of NO3− over time, NEA was expressed as μg N-NO3− h−1 g−1 dry soil.

Soil ammonium concentration was determined by ion chromatography on soil extracts. They were prepared from a fresh soil subsamples equivalent of 5 g dry soil mixed with 20 ml of 0.1 M CaCl2 for 2 h at 10 °C under constant agitation (180 rpm) and filtered through 0.2 μm before analysis.

Denitrification Enzymatic Activity (DEA)

DEA was measured according to Patra et al.55. Distilled water (1 ml) containing KNO3 (50 μg N-NO3− g−1 dry soil), glucose (500 μg C-glucose g−1 dry soil) and glutamic acid (500 μg C-glutamic acid g−1 dry soil) was added to fresh soil (10 g equivalent dry soil) placed in a 150 ml plasma flask. The atmosphere was replaced by 90% helium to ensure anaerobic conditions and 10% C2H2 was added to inhibit N2O reductase activity. The flasks were sealed with rubber stoppers and incubated at 28 °C for 6 h. After two hours of incubation, gas samples were analyzed every hour for the remaining five hours to measure N2O concentration using a gas chromatograph (Micro GC R3000, SRA Instrument, Marcy L’Etoile, France). Based on the linear accumulation of N2O over time, DEA was expressed as μg N-N2O h−1 g−1 dry soil.

DNA extraction and quantification

DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of flash frozen soil using the FastDNA™ SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals laboratories) following the manufacturer’s instructions and then quantified using the Quant it™ Picogreen© dsDNA Assay kit (Molecular Probes, USA). Fluorescence was measured using a UV spectrophotometer Xenius (Safas, Monaco) (λ = 520 nm). DNA extraction yields were not affected by TiO2-NP exposure (data not shown).

Abundance of nitrifying bacteria (AOA and AOB)

The abundance of AOA and AOB was measured by quantitative PCR targeting amoA gene sequences encoding for an ammonia monooxygenase specific for each domain. Amplification was performed using gene primers amoA_1F and amoA_2R for the AOB56 and for the AOA47. The final reaction volume was 20 μl and final concentrations of reaction mix were: 0.5 μM of each primer for the bacterial amoA or 0.75 μM of CrenamoA616r and 1 μM of CrenamoA23f for the archaeal amoA, 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 1X of QuantiTect SybrGreen PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and 10 ng of soil DNA extract or of DNA standards with 102 to 107 gene copies μl−1 using a constructed linearized plasmid containing archaeal (54d9 fosmide fragment)57 and bacterial (Nitrosomonas europaea, GenBank accession number:L08050) amoA genes. The samples were run in duplicate on a Lightcycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) as follows: for bacterial amoA 15 min at 95 °C, 45 amplification cycles (30 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 54 °C, 45 s at 72 °C and 15 s at 80 °C) and 30 s at 40 °C; for archaeal amoA, 15 min at 95 °C, 50 amplification cycles (45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 55 °C and 45 s at 72 °C) and 10 s at 40 °C. Melting curves analysis confirmed adequate amplification specificity.

Denitrifying bacteria abundances

The abundance of denitrifying bacteria was measured by quantitative PCR of the genes encoding copper- and cytochrome cd1-containing nitrite reductase (nirK and nirS, respectively). Amplification was performed using nirK876 and nirK1040 gene primers58 or nirSCd3aF and nirSR3cd59. The final reaction volume for nirK quantification was 20 μL and final concentrations of reaction mix were: 1 μM of each primer, 0.02 μg of T4 gene protein 32 (QBiogene, Illkirch, France), 1X of QuantiTect SybrGreen PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and 5 ng of soil DNA extract or of standards with 102 to 107 copies of DNA (Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021). The samples were run in duplicate on a Lightcycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) as follows: 15 min at 95 °C, 45 amplification cycles (15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 63 °C and 30 s at 72 °C) and 10 s at 40 °C. The final reaction volume for nirS quantification was 25 μl and final concentrations of reaction mix were: 0.5 μM of each primer, 0.02 μg of T4 gene protein 32 (QBiogene, Illkirch, France), 1X of QuantiTect SybrGreen PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and 12.5 ng of soil DNA extract or 102–107 copies of standard DNA (Pseudomonas stutzeri ATCC 14405). The samples were run in duplicate as follows: 15 min at 95 °C, 40 amplification cycles (15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 66 °C, 30 s at 72 °C and 15 s at 80 °C) and 10 s at 40 °C. Melting curves analysis confirmed the amplification specificity.

Diversity of bacteria, archaea and ammonia-oxidizers

High-throughput sequencing of bacterial and archaeal 16S rDNA genes and amoA AOB and AOA genes (Table 2) were performed on an Illumina MiSeq® platform by Molecular Research DNA, USA. Sequencing was performed on the samples obtained after 7 or 90 d of incubation. A combination of the tools available from the RDP FunGene website60 and the open-source software Mothur (v.1.33.3)61 was used to process and analyze the sequence data (Table 2). Sequencing products were first paired in overlapping pair-ends, except for amoA (AOA) amplicons that were too long (>500 bp) for the MiSeq technology. Resulting sequence data were then sorted according to their length, and the quality of the primers (<2 errors) and barcodes (<1 error). The primers and barcodes were trimmed off before searching potential chimeric formation using UCHIME62 implemented in Mothur. Putative chimeras were removed from the dataset. For amoA sequences, nucleotide sequences were translated in amino-acids and possible frame-reading shifts were detected and corrected using the FRAMEBOT algorithm63.

In Mothur, we clustered the corrected 16S sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) by setting a 0.03 distance limit64. The amoA sequences were clustered at 0.05 dissimilarity. The taxonomic identification of bacterial and archaeal 16S rDNA genes was performed using the Greengenes 13.5 database. Similarity of amoA sequences with known references were assessed with 7 652 sequences of amoA AOB and 9 326 sequences of amoA AOA extracted from the FunGene database60. The relatedness of amoA AOA sequences with identified archaeal taxa was performed with BLAST using the database assembled by Pester et al.45. Rarefaction curves based on identified OTU and species richness estimator ACE were generated using Mothur for each sample on a normalized number of sequences. Singleton reads were not considered for subsequent analyses. Non-metric Multi-Dimensional Scaling (NMDS) was performed using the metaMDS function, available in the Vegan package65 of the R software66 based on Bray-Curtis distances, associated to Permanova (Permutational multivariate analysis of variance) using the adonis function, to explore the difference in community composition in the different treatments.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as means (±standard errors). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc Tukey HSD were performed to test the effect of TiO2-NP concentrations on measured variables at each sampling time. Where necessary, data were log-transformed prior to analysis to ensure conformity with the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances. Linear regressions were conducted to investigate relationships between all variables measured in the experiment, described by Spearman correlation coefficient (r). Effects with P < 0.05 are referred to as significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using the R statistical software 2.13.2.

Path analysis67 was performed using Amos18® (Amos Development Corporation, Crawfordville, FL, USA) to explore the causal links between TiO2-NP concentration, nitrifier and denitrifier abundances, nitrification and denitrification activities. A χ2 test was used to evaluate model fit, by determining whether the covariance structures implied by the model adequately fit the actual covariance structures of the data. A non-significant χ2 test (P > 0.05) indicates adequate model fits. The coefficients of each path as the calculated standardized coefficients were determined using the analysis of correlation matrices. These coefficients indicate by how many standard deviations the effect variable would change if the causal variable was changed by one standard deviation. The indirect effects of a variable can be calculated by the product of the coefficients along the path. Paths in this model were considered significant with a P-value < 0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Simonin, M. et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles strongly impact soil microbial function by affecting archaeal nitrifiers. Sci. Rep. 6, 33643; doi: 10.1038/srep33643 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Marie Simonin was supported by a Ph. D grant from Rhône-Alpes Region – ARC Environnement. This work was funded by a grant from the French National Program EC2CO-CNRS AT-Microbien. The authors thank the technical assistance of Jonathan Gervaix and Morgane Ginot. Microbial measurements were performed at the AME platform (Microbial Ecology UMR5557 CNRS - UMR1418 INRA, Lyon), quantitative PCR at the DTAMB platform (IFR 41, University Lyon 1) and bioinformatic analyses at the Ibio platform (Microbial Ecology UMR5557 CNRS - UMR1418 INRA, Lyon). We want to thank also Dr Jennifer D. Rocca for her review of the manuscript and her useful comments.

Footnotes

Author Contributions The study was designed by M.S., A.R., J.M.F.M., M.S., T.P., J.M.F.M. and A.R. wrote the main manuscript text, M.S. and J.P.G. conducted the experiment and A.D. and M.S. performed the diversity analyses. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Keller A. A., McFerran S., Lazareva A. & Suh S. Global life cycle releases of engineered nanomaterials. J. Nanoparticle Res. 15, 1–17 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Liu H., Liu Y., He G. & Jiang C. Comparative activity of TiO2 microspheres and P25 powder for organic degradation: Implicative importance of structural defects and organic adsorption. Appl. Surf. Sci. 319, 2–7 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Mitrano D. M., Motellier S., Clavaguera S. & Nowack B. Review of nanomaterial aging and transformations through the life cycle of nano-enhanced products. Environ. Int. 77, 132–147 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J. et al. Photocatalysis fundamentals and surface modification of TiO2 nanomaterials. Chin. J. Catal. 36, 2049–2070 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Brar S. K., Verma M., Tyagi R. D. & Surampalli R. Y. Engineered nanoparticles in wastewater and wastewater sludge – Evidence and impacts. Waste Manag. 30, 504–520 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servin A. et al. A review of the use of engineered nanomaterials to suppress plant disease and enhance crop yield. J. Nanoparticle Res. 17, 1–21 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Simonin M. & Richaume A. Impact of engineered nanoparticles on the activity, abundance, and diversity of soil microbial communities: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–14 doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4171-x (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkowski P. G., Fenchel T. & Delong E. F. The Microbial Engines That Drive Earth’s Biogeochemical Cycles. Science 320, 1034–1039 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimel J. P. & Schaeffer S. M. Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil. Front. Microbiol. 3 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippot L., Raaijmakers J. M., Lemanceau P. & van der Putten W. H. Going back to the roots: the microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 789–799 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacheron J. et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Front. Plant Sci. 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daims H. et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 528, 504–509 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kessel M. A. H. J. et al. Complete nitrification by a single microorganism. Nature advance online publication (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalchuk G. & Stephen J. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: a model for molecular microbial ecology. Annual Reviews in Microbiology 55, 485–529 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser J. I. & Nicol G. W. Archaeal and bacterial ammonia-oxidisers in soil: the quest for niche specialisation and differentiation. Trends Microbiol. 20, 523–531 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalzell D. J. B. et al. A comparison of five rapid direct toxicity assessment methods to determine toxicity of pollutants to activated sludge. Chemosphere 47, 535–545 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broos K., Mertens J. & Smolders E. Toxicity of heavy metals in soil assessed with various soil microbial and plant growth assays: A comparative study. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 24, 634–640 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens J. et al. Bacteria, not archaea, restore nitrification in a zinc-contaminated soil. ISME J. 3, 916–923 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollivier J. et al. Abundance and Diversity of Ammonia-Oxidizing Prokaryotes in the Root–Rhizosphere Complex of Miscanthus × giganteus Grown in Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils. Microb. Ecol. 64, 1038–1046 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger S., Urich T. & Schloter M. Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxydizing prokaryotes in soils. Nature 442, 806–809 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumft W. G. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61, 533–616 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissett A., Brown M. V., Siciliano S. D. & Thrall P. H. Microbial community responses to anthropogenically induced environmental change: towards a systems approach. Ecol. Lett. 16, 128–139 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W. et al. TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles negatively affect wheat growth and soil enzyme activities in agricultural soil. J. Environ. Monit. 13, 822–828 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y., Schimel J. & Holden P. Evidence for negative effects of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles on soil bacterial communities. Environmental Science & Technology 45, 1659–1664 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonin M., Guyonnet J. P., Martins J. M. F., Ginot M. & Richaume A. Influence of soil properties on the toxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles on carbon mineralization and bacterial abundance. J. Hazard. Mater. 283, 529–535 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T. Y., Gottschalk F., Hungerbühler K. & Nowack B. Comprehensive probabilistic modelling of environmental emissions of engineered nanomaterials. Environ. Pollut. 185, 69–76 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jośko I., Oleszczuk P. & Futa B. The effect of inorganic nanoparticles (ZnO, Cr2O3, CuO and Ni) and their bulk counterparts on enzyme activities in different soils. Geoderma 232–234, 528–537 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Lowry G. V., Gregory K. B., Apte S. C. & Lead J. R. Transformations of Nanomaterials in the Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 6893–6899 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis G., Hund-Rinke K., Kuhlbusch T., Brink N., van den & Nickel C. Fate and Bioavailability of Engineered Nanoparticles in Soils: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 2720–2764 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Moro P., Stampachiacchiere S., Donzello M. P., Fierro G. & Moretti G. A comparison of the photocatalytic activity between commercial and synthesized mesoporous and nanocrystalline titanium dioxide for 4-nitrophenol degradation: Effect of phase composition, particle size, and addition of carbon nanotubes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 359, 293–305 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Fang J., Shan X., Wen B., Lin J. & Owens G. Stability of titania nanoparticles in soil suspensions and transport in saturated homogeneous soil columns. Environmental Pollution 157, 1101–1109 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel C. et al. Mobility of coated and uncoated TiO2 nanomaterials in soil columns–Applicability of the tests methods of OECD TG 312 and 106 for nanomaterials. J. Environ. Manage. 157, 230–237 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleper C., Jurgens G. & Jonuscheit M. Genomic studies of uncultivated archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 479–488 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine D. L. Adaptations to energy stress dictate the ecology and evolution of the Archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 316–323 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauss K. et al. Dynamics and functional relevance of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in two agricultural soils. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 446–456 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-R., Zheng Y.-M., Shen J.-P., Zhang L.-M. & He J.-Z. Effects of mercury on the activity and community composition of soil ammonia oxidizers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 17, 1237–1244 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollivier J. et al. Effects of repeated application of sulfadiazine-contaminated pig manure on the abundance and diversity of ammonia and nitrite oxidizers in the root-rhizosphere complex of pasture plants under field conditions. Front. Microbiol. 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Yu S., Park H., Liu G. & Yuan Q. Retention of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in biological activated carbon filters for drinking water and the impact on ammonia reduction. Biodegradation 27, 95–106 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ünşar E. K., Çığgın A. S., Erdem A. & Perendeci N. A. Long and short term impacts of CuO, Ag and CeO2 nanoparticles on anaerobic digestion of municipal waste activated sludge. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 18, 277–288 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams L. K., Lyon D. Y. & Alvarez P. J. J. Comparative eco-toxicity of nanoscale TiO2, SiO2, and ZnO water suspensions. Water Res. 40, 3527–3532 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Deckers A. et al. Size-, Composition- and Shape-Dependent Toxicological Impact of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles and Carbon Nanotubes toward Bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 8423–8429 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohm B., Immel F., Bauda P. & Pagnout C. Insight into the primary mode of action of TiO2 nanoparticles on Escherichia coli in the dark. Proteomics 15, 98–113 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketani R. G. & Tsai S. M. The Influence of Different Land Uses on the Structure of Archaeal Communities in Amazonian Anthrosols Based on 16S rRNA and amoA Genes. Microb. Ecol. 59, 734–743 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates S. T. et al. Examining the global distribution of dominant archaeal populations in soil. ISME J. 5, 908–917 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pester M. et al. amoA-based consensus phylogeny of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and deep sequencing of amoA genes from soils of four different geographic regions. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 525–539 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhalnina K. et al. Ca Nitrososphaera and Bradyrhizobium are inversely correlated and related to agricultural practices in long-term field experiments. Front. Microbiol. 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourna M., Freitag T. E., Nicol G. W. & Prosser J. I. Growth, activity and temperature responses of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1357–1364 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z. & Conrad R. Bacteria rather than Archaea dominate microbial ammonia oxidation in an agricultural soil. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 1658–1671 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Zhang L., Zhu Y., Zhang J. & He J. Abundance and composition of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing archaea communities of an alkaline sandy loam. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1601–1611 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia W. et al. Autotrophic growth of nitrifying community in an agricultural soil. ISME J. 5, 1226–1236 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai C. et al. Different roles of rhizosphere effect and long-term fertilization in the activity and community structure of ammonia oxidizers in a calcareous fluvo-aquic soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 57, 30–42 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux X. et al. Soil Environmental Conditions and Microbial Build-Up Mediate the Effect of Plant Diversity on Soil Nitrifying and Denitrifying Enzyme Activities in Temperate Grasslands. Plos ONE 8, e61069 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel A. A. M. et al. Four years of experimental climate change modifies the microbial drivers of N2O fluxes in an upland grassland ecosystem. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 2520–2531 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Dassonville N., Guillaumaud N., Piola F., Meerts P. & Poly F. Niche construction by the invasive Asian knotweeds (species complex Fallopia): impact on activity, abundance and community structure of denitrifiers and nitrifiers. Biol. Invasions 13, 1115–1133 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Patra A. et al. Effect of grazing on microbial functional groups involved in soil N dynamics. Ecological Monographs 75, 65–80 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Rotthauwe J. H., Witzel K. P. & Liesack W. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 4704–4712 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treusch A. H. et al. Novel genes for nitrite reductase and Amo-related proteins indicate a role of uncultivated mesophilic crenarchaeota in nitrogen cycling. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 1985–1995 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry S. et al. Quantification of denitrifying bacteria in soils by nirK gene targeted real-time PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 59, 327–335 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandeler E., Deiglmayr K., Tscherko D., Bru D. & Philippot L. Abundance of narG, nirS, nirK, and nosZ Genes of Denitrifying Bacteria during Primary Successions of a Glacier Foreland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5957–5962 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J. A. et al. FunGene: the functional gene pipeline and repository. Front. Microbiol. 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss P. D. et al. Introducing mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7537–7541 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C., Haas B. J., Clemente J. C., Quince C. & Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. et al. Ecological Patterns of nifH Genes in Four Terrestrial Climatic Zones Explored with Targeted Metagenomics Using FrameBot, a New Informatics Tool. mBio 4, e00592–13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Morrison M. & Yu Z. Evaluation of different partial 16S rRNA gene sequence regions for phylogenetic analysis of microbiomes. J. Microbiol. Methods 84, 81–87 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J. et al. The vegan package. Community Ecol. Package (2007). [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2015).

- Shipley B. Cause and Correlation in Biology: A User’s Guide to Path Analysis, Structural Equations and Causal Inference (Cambridge University Press, 2002). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.