Abstract

Capture success and prey selectivity were investigated in clownfish Amphiprion ocellaris larvae using videography. Three prey types were tested using developmental stages (nauplii, copepodites and adults) of the copepod Parvocalanus crassirostris. Predatory abilities improved rapidly between days 1 and 14 post-hatch. Initially, capture success was limited to nauplii with few attacks on larger stages. Captures of copepodites were first observed at 3 dph, and of adults at 8 dph. Consistent strikes at the larger prey were observed on the day prior to successful captures (2 dph for copepodites, 7 dph for adults). Difference in capture success between nauplii and adults at 8 dph was an order of magnitude. Differences in capture success among prey types persisted but decreased to three-fold by 14 dph. Younger A. ocellaris attacked nauplii preferentially and avoided adult prey. Strike selectivity declined with age, and no selectivity was observed after 10 dph. However, numerically 50% of the ingested prey were still nauplii at 14 dph under the experimental conditions.

The planktonic larval phase of fishes is characterized by high recruitment variability and mortality rates that exceed 99%1. While multiple factors contribute to this variability, the inability to find and capture sufficient food during the planktonic phase is one factor that can lead to poor growth and increased mortality2,3,4,5,6. Marine larval fishes are typically zooplanktivorous, feeding on a variety of micro- and meso-zooplankton as shown by gut content analysis7,8,9,10,11. Although food availability may not be limiting in some habitats8,12, faster growth rates are correlated with higher recruitment success in both temperate and coral reef larval fishes2,13,14. Furthermore, growth rates are often correlated with prey abundances6,15. Larvae of sub-tropical reef fishes have higher energetic demands13 and swimming endurances in late stage planktonic fish larvae appear to be related to feeding status, suggesting that availability of prey may be critical for larvae near settling16.

The diets of wild-caught larval fishes are often dominated by copepods as indicated by gut content analyses9,12,17,18,19. However, feeding success on evasive prey can be low in larval fishes20,21, which could effectively lower the number of available prey, at least in early stage larval fishes22,23. Here, we investigated the changes in capture success and prey selectivity between first feeding and age of settlement in a predator-prey system that serves as a model for coral reef systems: the larvae of the clownfish, Amphiprion ocellaris preying on different developmental stages of the sub-tropical calanoid copepod Parvocalanus crassirostris.

Copepod Prey

Copepods are small crustaceans that inhabit marine and freshwater environments. Free-living planktonic forms range in size from 0.1 to 10 mm in length, and they are an important source of food for invertebrates, fishes, birds and even marine mammals24,25,26. Copepods are also among the most evasive planktonic organisms in the pelagic environment27. They possess an array of mechanosensory setae on the first antenna, which are sensitive to hydromechanical disturbances28,29,30,31,32,33. Escape responses are characterized by high accelerations and swimming speeds (>100 m s−2, and >350 m s−1 for a 1 mm copepod) and very short response latencies (<3 ms)34,35,36,37,38,39.

The copepod prey in this study was a small sub-tropical species, the paracalanid, Parvocalanus crassirostris, which ranged in size from 60 to 400 μm in length40. Behavioral sensitivity and escape behaviors of multiple developmental stages (nauplii and copepodites) of P. crassirostris have been quantified using an artificial stimulus41. The early developmental stages, nauplii, were found to be less sensitive to the hydromechanical stimulus, and their behavioral latency was longer than those of the copepodites (4 vs. 3 ms)41. Maximum escape speeds increased with copepod size from 36 to >150 mm per second and scaled with length41. All developmental stages of this copepod had well-developed escape responses, and maximum swim speeds are similar to those reported for 3 to 8 mm larval fish (~60 to 200 mm s−1)42,43.

Larval fish predatory behavior

Predatory behavior of fish larvae involves a slow approach while bending of the tail followed by a sudden forward thrust and capture of prey22,44. Feeding success increases with development: larvae increase their swimming speeds, and their approach is less likely to elicit an escape response in the prey21,44. Although copepods are typically found in larval fish guts, fish larvae such as cod (Gadus morhua) may not start feeding on even the youngest copepod stages until nine days post-hatch, four to five days after first feeding, preferring to feed initially on protozoa, which swim more slowly and have limited escape responses21. Thus, while low encounter rates with prey may contribute to low feeding rates6,45,46, capture success may be equally important, in particular at first feeding when predatory abilities are still poorly-developed, even for non-evasive prey5,21,44,47.

Clownfish-copepod interaction

The planktonic larval phase of clownfish (Amphiprion: Pomacentridae) spans approximately two weeks from hatching, which is representative of the duration of the larval phase of many reef fishes48. In contrast to many temperate fish larvae, clownfish feed on copepods and phytoplankton through most of the larval period49, although not much is known about their feeding success. As newly hatched larvae, clownfish carry a yolk sac, which is fully absorbed by the third day post-hatch50. During the first two days, feeding rates in at least some species is very low, and capture success on non-evasive rotifers is less than 60%47,51. Captive rearing protocols have been developed for several clownfish species, including A. ocellaris, used in this study52.

Zooplankton communities in many sub-tropical environments are dominated by small copepod species (≤1 mm in length) in the families Paracalanidae (Calanoida), Clausocalanidae (Calanoida), and Oithonidae (Cyclopoida)53,54,55,56,57,58. The paracalanid P. crassirostris has a widespread distribution and occurs in coastal waters in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. In much of its geographic range, this species co-occurs with members of the Pomacentridae, including A. ocellaris and other clownfish species61,62.

P. crassirostris is similar in size, body form, life history and ecology to other small paracalanids that dominate many sub-tropical habitats61,63. Gut content analysis studies of coral reef fish larvae usually classify calanoid copepod prey by developmental stage (nauplii, copepodites) or size (small vs. large species)9,18, where paracalanid prey, such as P. crassirostris would be among the “nauplii”, “copepodites” and “small calanoids” categories. According to these studies larval Pomacentridae consume copepod nauplii, copepodites and small calanoids but not large copepods9,18.

Here, we investigated growth, capture success and prey selectivity of larvae of the clownfish, Amphiprion ocellaris under experimental conditions using video recordings of predator-prey interactions between larval fish and copepod prey that ranged in size and evasive capabilities. Nauplii, copepodites and adults, i.e., different developmental stages of the copepod P. crassirostris were used as prey. While prey selectivity is usually determined from gut contents, the focus of this study was to quantify which prey types were preferentially attacked and determine the outcome of the interaction. While predator’s mouth gape has been used to predict prey size64,65,66,67, this may not apply when highly evasive zooplankton prey are considered. Specifically, we hypothesized that changes in capture success and prey selectivity between first feeding and age of settlement could not be explained by mouth gape. Thus, the goal was to quantify predatory abilities of a larval fish during its planktonic phase in order to understand how feeding success on a natural prey changed during early development.

Results

Amphiprion ocellaris growth

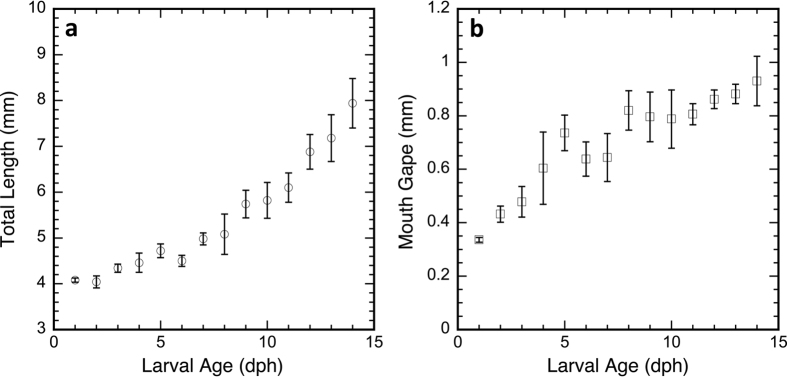

During the first two weeks post-hatch, the larvae nearly doubled their total length from 4.1 mm at 1 day post-hatch (dph) to 7.9 mm at 14 dph (Fig. 1a), while mouth gape increased by a factor of 3 from 0.3 to 1 mm during this time period (Fig. 1b). By 2 dph, the mouth gape exceeded the prosome length of the largest prey (~400 μm, adult female).

Figure 1. Growth of Amphiprion ocellaris larvae during the first two weeks post-hatch.

(a) Average total length for six individuals for each time point between 1 and 14 dph. (b) Average mouth gape. Error bars: standard deviations.

Capture success as a function of larval age

Capture success was investigated in two experiments using three prey types that differed in evasiveness: P. crassirostris nauplii, copepodites and adults. In Experiment I, feeding trials consisted of single prey types, and A. ocellaris predatory success was determined on days 1, 3 and 10 dph. In Experiment II, feeding trials consisted of mixed prey assemblages and predatory success and prey selectivity were determined daily between 1 and 14 dph. Under our experimental conditions, rejection of prey was not observed and all successful captures led to ingestion of prey (100% ingestion rate).

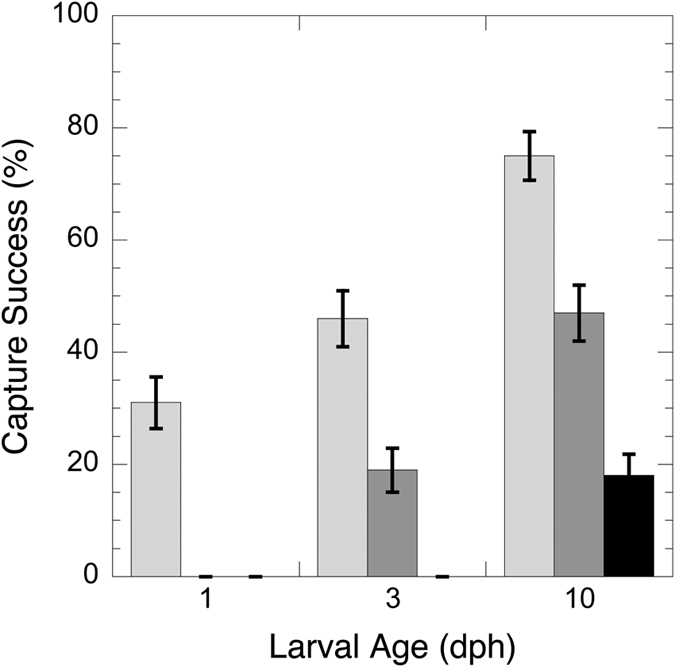

Prey type and larval age both had a significant effect on strike outcome in both experiments (p < 0.005; Tables 1 and 2). For Experiment I, A. ocellaris prey capture success in behavioral trials with single prey at 1, 3, and 10 dph was always higher on nauplii than for the other prey types, and capture success rates increased with larval age. Initially, larvae were capturing nauplii with a 31% success rate, but unable to capture either copepodites or adults. At 3 dph, the larvae were capturing both nauplii and copepodites at 46% and 19% success rate, respectively, but not adults. At 10 dph, all three prey types were captured, although success rates differed by a factor of four between adult and naupliar prey types (Fig. 2).

Table 1. Statistical analysis for Experiments I and II.

| Expt | Effect on attack outcome | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expt. I | Larval fish age | 2 | <0.005 |

| Prey type | 2 | <0.005 | |

| Expt. II | Larval fish age | 13 | <0.005 |

| Prey type | 2 | <0.005 |

The effects of age of fish larvae and prey type on attack outcome were tested using a logistic regression.

Table 2. The effect of prey types presented in experiment II on attack outcome for days 1 to 14, and days 7 to 14 post-hatch.

| Age Interval | Attack outcome by prey type | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days 1–14 | Nauplii | 1 | <0.005 |

| Copepodites | 1 | <0.005 | |

| Adults | 1 | 0.997* | |

| Days 7–14 | Nauplii | 1 | <0.005 |

| Copepodites | 1 | <0.005 | |

| Adults | 1 | <0.005 |

*Days 1–14 post-hatch included no successful captures of adult prey during the initial 7 days.

Figure 2. Capture success rate of nauplii (light gray), copepodites (dark gray) and adult (black) Parvocalanus crassirostris by Amphiprion ocellaris at 1, 3 and 10 dph in Experiment I.

Number of observations = 100, except for attacks on adults at 1 dph which resulted in fewer than 25 observed strikes. Single prey type added at an initial density of 1 ml−1. Error bars: standard deviations.

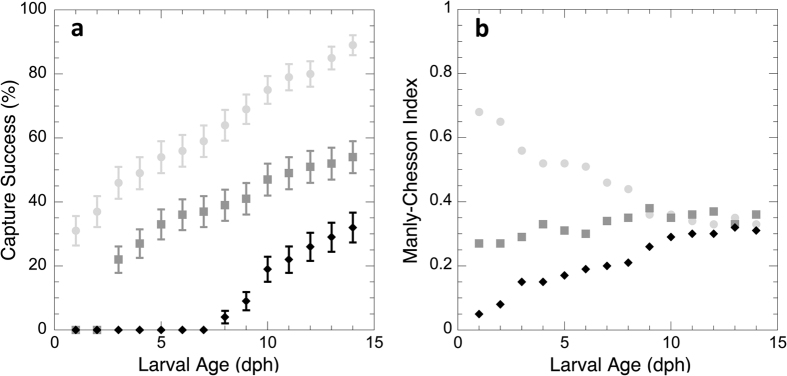

Similar results were obtained in Experiment II using mixed prey assemblages (Fig. 3a). This experimental series confirmed that fish larvae captured only nauplii initially. Successful capture of copepodites was first observed at 3 dph, and successful capture of adults was first observed at 8 dph (Fig. 3a). Predatory capability increased with age as shown by the successive addition of copepodites and adults to the capture repertoire, as well as a steady increase in capture success for each prey type. Thus, in these experiments, the larval fish captured only nauplii and copepodites during pre-flexion, and added adult prey after reaching post-flexion at 7 dph. By 14 dph, capture success rates were ca. 90% for nauplii, 50% for copepodites and 30% for adults (Fig. 3a). A regression analysis for the period that nauplii, copepodites and adults were captured (7 to 14 dph) showed significant effects (p < 0.005) on strike outcome for the three prey types (Table 2).

Figure 3. Capture success rate and prey selectivity of Amphiprion ocellaris between 1 and 14 dph on nauplii, copepodites and adults of Parvocalanus crassirostris in Experiment II.

(a) Capture success rate on nauplii (light gray circles), copepodites (dark gray squares), and adults (black diamonds) in mixed prey assemblages with 1 prey ml−1 in equal proportions by prey type. Number of observations = 100 strikes per prey type and dph, except for days 1 to 6 dph for adult prey, and 1 dph for copepodite prey. Error bars: standard deviations. (b) Manly-Chesson index calculated for each day post-hatch. Nauplii: light gray circles; copepodite: dark gray square; adults: black diamonds.

Prey selectivity

Predation selectivity, defined as a pattern of predator preference or avoidance for striking a prey type that cannot be explained by the probability of encountering that prey type in the environment, was quantified via the Manly-Chesson Selectivity Index for each larval age (Fig. 3b). Since the three prey types were at equal densities, a value close to 1/3 indicates no selective behavior in strike rates by the predator. Strikes on copepodite prey were close to this predicted 1/3 for the entire 14-day period, even though these prey were not captured until day 3. However, selective feeding occurred for the other two prey types. Initially, larvae preferentially attacked nauplii while avoiding adults, but the preference for nauplii and avoidance of adults decreased during the larval period, approaching 1/3 after 10 dph. A Pearson chi-square analysis confirmed that strikes on nauplii were significantly different (p < 0.05) from 1/3 between days 1 and 8 post-hatch, but not between days 10 and 14 post-hatch. The observed proportion of strikes on adult copepods was also significantly different (p < 0.05) from 1/3 between days 1 and 9 post-hatch.

Discussion

The interaction between a predator and a prey can be described as a process that involves multiple steps from search and encounter to strike, capture, and ultimately ingestion45,68. The high densities of prey (1 prey per ml) in the current study assured high encounter rates between predator and prey, and thus, did not examine search behavior, but focused on capture success. While copepods are the preferred prey of many, if not most marine larval fishes, they are also among the most evasive zooplankters35,36,41,69. Thus, early fish larvae may require much higher ambient plankton abundances than would be predicted from ingestion rates and search volumes due to low feeding efficiency23. Here, we investigated two aspects of feeding efficiency: prey choice and capture success of a larval fish predator between first preying and settlement preying on a small calanoid copepod with a well-described and quantified escape response.

Predatory success in the clownfish larvae was characterized by a steady increase in capture rates with age for each prey type. The capture success rates reported here (none to 90%) are comparable to those reported in the literature for marine fish larvae feeding on either non-evasive (Artemia and rotifers) or evasive (mixed plankton, nauplii) prey. Depending on larval age and fish species reported rates of capture success range from 6% to over 90%20,21,22,23,44,70. However, not all fish larvae ingest copepod nauplii initially, feeding instead on smaller auto- and heterotrophs21,71,72. While improvements in capture efficiency/success of fish larvae have been established for both non-evasive and evasive prey22,23,44,70, no studies have quantified how this capture success changes over time using natural prey. A. ocellaris added prey during the planktonic phase from a single prey type (nauplii) and modest capture success (~30%) at first feeding to all three prey types by 8 dph. Energetic demands increase steeply during the larval period, and larvae increase the number of prey consumed and ingest larger prey44,70. In our experiments, which focused on a single, small calanoid species, the addition of larger prey to the diet was the result of changes in strike selectivity and increase in capture success. Nevertheless, in A. ocellaris differences in capture success which were as much as 15-fold between nauplius and adult prey at 8 dph suggest that capture of large prey came at a cost. While the difference in capture success between nauplii and adults persisted through development, it declined to 3-fold by 14 dph.

Fish larvae are not only characterized by rapid growth, but also many other developmental changes including the maturation of the sensory, motor, and digestive systems50,73,74. All of these factors are likely contributors to improvements in predatory behavior. In addition, learning may be a factor as well, as suggested by the observation of consistent, yet unsuccessful strikes on copepodites and adults on the day prior to their successful capture. In the current study, the fish larvae were exposed to different developmental stages of P. crassirostris in the rearing tank, and this may have contributed to their ability to capture the prey as observed in the behavioral experiments. Other studies have also suggested that experience and learning contribute to feeding success23,44.

Based on mouth gape measurements, A. ocellaris would have been expected to feed on adult P. crassirostris by day 2–3 post-hatch. Thus, fish gape, which has been used as a predictor for the maximum size of prey64,65,66,67,75 was not a valid predictor of prey consumption in this study. In contrast, non-evasive prey, such as rotifers (lorica length: 100–300 μm), which are similar in size to P. crassirostris copepodites, are captured with a 100% success rate at 3 dph, as was shown experimentally for the congener, Amphiprion periderion47. While it has been suggested that the physical development of the larval fish feeding apparatus could limit prey size to less than 50% of gape width76, escape capabilities by potential prey may be equally important given the differences in capture success that are independent of prey size.

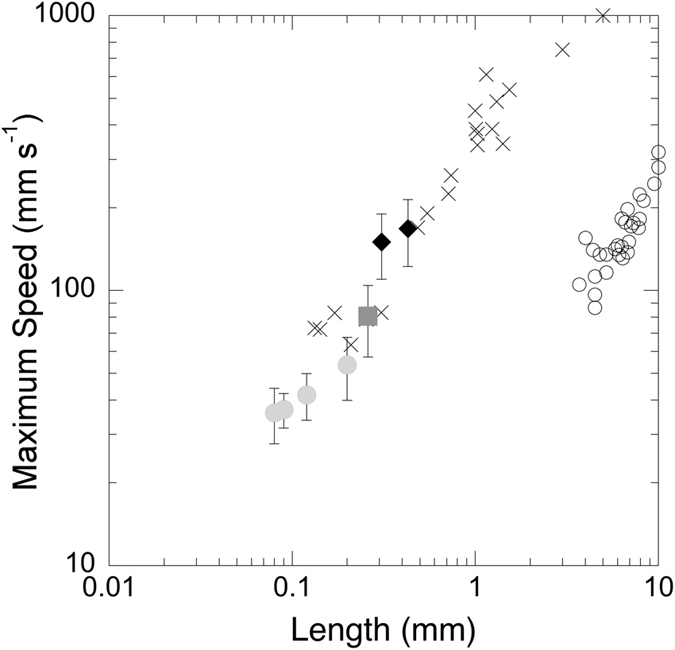

Calanoid copepods detect approaching predators using sensitive mechanoreceptors located on the first antenna29,30,32,77. The presence of large axons and myelin ensures that response latencies are in the millisecond range39,78, and that escapes are characterized by rapid acceleration, high speeds and large force production35,36,37,41. For all developmental stages of planktonic copepods, maximum escape speeds scaled by length are nearly an order of magnitude higher than those of fishes38,41,42,79. In Fig. 4, maximum swim speeds are plotted against length for different species of fish larvae (length: 3–12 mm) and for calanoid copepods, including P. crassirostris. Based on the relative sizes of the larval predator (4–8 mm) and the prey, maximum swim speeds of nauplii and early copepodites (CI) would be lower than those predicted for A. ocellaris larvae. However, maximum swim speeds of adult P. crassirostris are higher than those predicted for the smaller and younger A. ocellaris larvae (<6–7 mm; Figs 1 and 4). Thus, initial capture success of adult copepods by the fish larvae (8 dph) occurs before they have reached comparable maximum swim speeds. For a successful strike, the larval fish has to get close enough to the prey without alerting it to the predator’s presence21.

Figure 4. Maximum escape speeds plotted against total length for calanoid copepods, including Parvocalanus crassirostris and larval fishes.

Maximum swimming speeds for P. crassirostris are averages and error bars are standard deviations (nauplii: light gray circles; copepodite: dark gray square; adults: black diamonds)41. Crosses: other published copepod data35,36,38,41. Open circles: larval fish data are maximum average swim speeds for individuals from five species ranging in length from 3.7 and 10 mm42.

Although maximum escape speeds may be an important factor in promoting successful escapes by the prey, sensory detection also plays a significant role in alerting copepods to approaching prey80,81. Compared with adults, naupliar stages have lower mechanosensitivity, and longer delays to behavioral responses41. On average, P. crassirostris copepodites responded at a greater distance from the stimulus (2.8 vs. 3.8 mm) with a shorter latency (3 vs. 4 ms) and reached maximum swim speeds (~5 vs. >10 ms) more quickly than nauplii in response to an artificial stimulus41. These differences in sensory detection and escape capabilities among prey types are likely to contribute to the significant differences in capture success by the larval fish at any given age during the planktonic phase.

Each component of the sensori-motor system of the prey will influence the outcome of a predator-prey interaction. However, the relative importance of sensory detection, response latency and escape behavior is likely to change with development of the prey and the predator. Furthermore, copepod escape responses differ among species36,82, and some of these differences are already present in nauplii41,83. While P. crassirostris co-occurs with clownfish larvae, it is nevertheless, only one of the common species found in coastal pelagic environments58,84. Little is known about how species-specific differences in copepod escape response might affect the diet of coral reef fishes, however, there is evidence of selective feeding in larvae of Atlantic mackerel even at the copepod nauplius level71. Specifically, gut content analysis suggested that mackerel selected for the nauplii of two species, but against those of the third species.

The Manly-Chesson Selectivity Index is used extensively as an indicator of whether a particular prey is consumed in proportion to its occurrence85. However, in general, this index is based on gut content analysis, and as a result does not distinguish between encounter probability, selectivity, and capture success69. Here, we applied the Manly-Chesson Index to specifically address the predator’s selectivity for prey type, independent of capture success. Thus, it addresses the question of whether the clownfish larvae preferentially strike or avoid certain prey types as a function of age during the planktonic phase. Fish larvae that were too young to capture the adult copepods showed low selectivity for this prey type, while showing preference for the nauplii. Selectivity for nauplii decreased steadily with larval age. Based on the observation that no prey were rejected in our experimental conditions, relative feeding rates of A. ocellaris on the three prey types can be calculated by multiplying capture success by the selectivity index. Thus, numerically, nauplii constituted 100% of the diet of A. ocellaris larvae at first feeding, and this percentage dropped to 50% at 14 dph, while the relative number of copepodites and adults increased with age reaching an estimated 33% and 17%, respectively.

The trends we observed in strike selectivity and capture success would suggest that the contribution of nauplii to the diet would continue to decrease with increasing size of fish larvae. Gut content analyses of larger Pomacentridae (≥8 mm) are consistent with this prediction. While nauplii were still consumed, copepodites constituted the majority of the gut contents (84%)9, with positive selectivity for small copepods (copepodites) and avoidance of nauplii18. Given the difference in nutrition (~30-fold difference in dry weight between nauplii and adult P. crassirostris), fish larvae would be better off preying on adults than nauplii even with a lower capture success rate. However, encounter rates with nauplii may be much greater in the natural environment, given that the younger life stages typically outnumber copepodites and adults86. Thus, given the higher capture success and higher abundances of nauplii, low numbers of nauplii in fish guts would suggest avoidance of these small prey as larval fish become larger.

In this study, we focused on predatory success during the early larval fish phase of the false percula clownfish, A. ocellaris. Predator-prey experiments performed with larval fish between 1 and 14 dph and different developmental stages of copepod prey (P. crassirostris nauplii, copepodites and adult copepods) determined that initial capture success was low and limited to nauplii, the least evasive of the three prey types. Predatory abilities showed incremental improvement in capture success occurring at daily intervals with the addition of more evasive prey at 3 and 8 dph and increases in capture success for all prey types. While copepods are the most common prey of larval fishes, species differ in their swimming and escape behaviors36,41. We tested a single species of copepod, yet in their habitat fish larvae will encounter a diverse array of copepod species as well as developmental stages. While adult fishes modulate their predatory strategy in response to prey type82,87, the ability for larval fishes to do so may be more limited. Thus, differences in capture success for different copepod species could contribute to prey selectivity that is calculated from gut contents.

Materials and Methods

Cultivation P. crassirostris

P. crassirostris were cultured following dilution and algal feeding protocols developed for a related paracalanid, Bestiolina similis88,89,90. Briefly, multiple high-density (up to 10 individuals ml−1) copepod cultures were maintained in 20 L containers. Tisochrysis lutea (formerly known as Isochrysis galbana Tahitian strain) was added daily and phytoplankton densities in the copepod cultures were maintained between 104 and 105 cells ml−1. In order to match the feeding needs of A. ocellaris larvae, P. crassirostris cultures were managed for the production of nauplii and copepodites by timing peaks in P. crassirostris reproduction, which occurred shortly after dilution of the stock culture89. Phytoplankton and copepods were maintained in seawater (35 ppt), constantly aerated and kept under a 12:12 hour light:dark cycle at ambient temperature (21–26 °C). Lighting was provided with 20-watt fluorescent lights (T12/Daylight).

Preparation of experimental prey fields

P. crassirostris were sorted by sieving using pairs of sieves with coarser and finer mesh sizes to isolate the target prey. The first pair, with 35 and 100 μm Nitex mesh sizes, concentrated nauplii of stages NI to NIV, which ranged in length between 60–130 μm in length and 40–60 μm in width40,89,90. The second pair, with mesh sizes of 200 and 275 μm, isolated copepodites (CI to CIII), which ranged in size between 200–300 μm in length and 80–110 μm in width40,90. The third pair, with mesh sizes of 323 and 400 μm, concentrated adult females (length: 400 μm, width: 160 μm)40,90. Prey samples were checked for the target stages and enumerated under a dissecting stereomicroscope (Olympus Corporation, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan; SZX-ILLB2) at 50× magnification. The concentrated P. crassirostris samples were then used to seed the observation chamber with either a single prey type at 1 individual ml−1 (experiment I), or 0.33 individuals ml−1 per prey type for the mixed prey trials (experiment II) (see below).

Larval fish rearing protocol

Experimental data were obtained from Amphiprion ocellaris larvae reared in the laboratory. Two experimental series were completed using seven broods of ca. 200 eggs each from a breeding pair of A. ocellaris (Table 3). Eggs were obtained from a fish breeder on the day of hatching (0 days post hatch [dph]), allowed to hatch overnight, and transferred to a rearing container (20 L) maintained in a water bath kept at 25 to 27 °C. Fish larvae were fed daily on all life stages of P. crassirostris to target prey densities of 5 copepods ml−1. The daily feeding ration was usually depleted by the next morning, and daily consumption of prey by the fish larvae was estimated at 300 to 1000 copepods per individual per day depending on larval age and prey size. In addition, the rearing tank was seeded with T. lutea and phytoplankton densities were kept at 1 × 103 cells ml−1. Fish handling and behavioral protocols were carried out in accordance with approved guidelines set by the Office of Research Compliance at the University of Hawaii (Hawaii, USA), and all experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (IACUC) for animal research under protocol number 1045. At 14 dph all surviving fish larvae (ca. 20–30%) were returned to the breeder.

Table 3. Summary of experimental conditions during Experiments I and II.

| Experiment I | Experiment II | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (days post-hatch) | 1, 3 & 10 | 1–14 |

| Quantitative analysis | Capture success | Capture success Prey selectivity |

| Prey densities (ind ml−1) | 1 | 1 |

| Prey assemblages | Single prey/trial(NI-NIV) + (CI-CIII) + (CVI) | Mixed prey/trial(NI-NIV) + (CI-CIII) + CVI |

| Fish larvae (#/trial) | 10 | 10 |

| Broods (#/experiment) | 2 | 5 |

| 60 min trials (#) | 29 | 72 |

| Time of day | 10:00–13:00 | 10:00–16:00 |

Morphological measurements of fish larvae

Larval length and gape width were measured from 1 to 14 dph at 1-day intervals. For each set, six A. ocellaris were euthanized from a single brood using a solution of 0.06 g/ml Ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate salt (MS222) (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., Saint Louis, MO, USA; catalog no. A5040-25G), preserved in a solution of 5% formalin in seawater, and measured for total length and jaw size within one week of fixation. Total length, a metric commonly used for clownfish larvae, is the greatest straight-line distance measured between the most anterior and posterior points of the body91,92. Measurements of fish larvae were made using a reticle calibrated with a 2.0 mm microscope micrometer at 12× for total length and 100× for mouth gape (Wild model M5A dissecting microscope). Upper jaw lengths were measured from the anterior-most point of the premaxilla to the posterior edge of the maxilla. Lower jaw lengths were measured from anterior-most part of the mandible to it posterior edge. Mouth gape was determined using Pythagorean theorem, assuming that the jaws represent two sides of a right triangle and the hypotenuse is the expected mouth gape93,94.

Behavioral observations

The experimental design for the behavioral observations was close to the feeding conditions in the rearing tank in terms of prey numbers and fish density. Thus, the goal of these observations was to obtain quantitative data on larval fish capture success on prey upon which they had been reared. For each trial, 10 A. ocellaris larvae were transferred from the rearing tank into the observation chamber (18 × 18 × 10 cm aquarium made of Plexiglas) filled with 3 L of filtered seawater (Whatman filters, GF/C). The fish larvae were allowed to acclimate for 15 minutes, before adding the 3 × 103 prey (1 ml−1). Each experimental trial lasted for 60 minutes and prey densities declined by 25% or less during this time. A. ocellaris and P. crassirostris interactions were filmed at 30 frames per second (fps) with a CCTV video camera (Panasonic Corporation, Kadoma, Osaka, Japan; model WV-BP310) equipped with a Nikkor 50 mm lens (Nikon Corporation, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan; model 1433) and recorded on a digital high definition videocassette recorder (Sony Corporation, Minato, Tokyo, Japan; model GV-HD700). The camera lens was positioned 0.3 m from the observation chamber and the lens was focused in a plane at the center with a field of view of 4 cm2. The container was uniformly illuminated from above with one 20-watt fluorescent light providing 1,900 lumens of light. Water temperature was between 23 and 25 °C.

Each day upon completion of filming, fish larvae were either fixed for length and gape measurements (see above), or they were returned to a second rearing container to avoid re-sampling. For the data analysis, videos were reviewed, larval predatory strikes identified and scored as to outcome (successful/unsuccessful). In a second analysis for experiment II, predatory strikes were scored for the targeted prey type to determine selectivity. For approximately 15% of strikes, resolution, clarity or contrast was insufficient to accurately determine prey type and these were excluded from the final dataset.

Behavioral Experiments

Experimental details are summarized in Table 3. In Experiment I, larval fish were presented with one of the three prey types at three ages (1, 3 and 10 dph) to determine the ability of the predator to capture a particular prey type in the absence of other choices. The choice of ages included first feeding (1 dph), absorption of the yolk sac (3 dph) and post-flexion (10 dph). In these experimental conditions, the number of strikes scored for any individual trial increased with larval age, and the number of strikes per trial was greater than 10, so that more than one strike would have been recorded for an individual fish. For each combination of prey type and larval fish age, video footage was reviewed until 100 strikes with unambiguous outcomes were identified, and each strike was scored for capture success. Ambiguous outcomes were noted, but not included in subsequent data analysis. A total of 29 trials (290 fish larvae) were run to obtain 100 observations for each prey type. At 1 and 3 dph, the fish larvae attempted few strikes on adult copepods resulting in fewer than 100 observations for this prey type.

In experiment II, capture success was examined in the presence of mixed prey assemblages with equal densities of each prey type (Table 3) to determine changes in predatory ability at one-day intervals from 1 to 14 dph. In this experiment, 72 feeding trials (720 fish larvae) were completed using five separate broods (Table 3). As in experiment I, the number of strikes per trial was usually greater than 10, so that more than one strike would have been recorded for any individual fish. Because the frequency of strikes differed between trials, and in particular with age, the predatory ability of A. ocellaris was determined by scoring capture success of 100 strikes for any given prey type. Videotapes from experimental trials for a given larval age were reviewed and analyzed until the cumulative number of scored strikes reached 100. Fewer than 100 strikes were scored for larval fish attacking copepodites on 1 dph and adult prey on 1–6 dph because of low strike incidence.

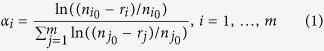

In addition, the predator’s choice of prey (selectivity) was determined by analyzing strike frequency on each prey type. For the prey selectivity analysis, 100 strikes were chosen from a subset of strikes by using a random number generator to select a starting point (to the minute) amongst all of the footage recorded for each larval age and then reviewing the strikes in continuous order to determine the targeted prey type for each strike. Prey selectivity was computed as the Manly-Chesson selectivity index85:

|

Where in Equation (1) ri = the number of prey individuals of type i attacked, ni0 = the number of prey individuals of type i present at the beginning of each 60 min trial, m = the total number of prey types present and j signifies prey category since each prey category is added in series. This index accounts for the dynamic probabilities of prey encounter over the course of experimental trials without prey replacement. Use of the index requires the assumption that encounters with prey items, which do not result in consumption do not affect the predator’s subsequent behavior. Note that the application of the index here is unusual since it computes an index for prey strikes, not consumed prey85. Distinguishing between prey types was done by size.

Statistical analysis

A logistic regression analysis was performed on the data with strike outcome as the dichotomous dependent variable and larval A. ocellaris age (Expt I: 1, 3 and 10 dph, Expt. II: 1–14 dph) and prey type (nauplii, copepodites and adults) as independent variables. The likelihood-ratio method was used to estimate probability values, and standard deviations for capture success for each prey and larval age combination were calculated based on a binomial distribution. A Pearson chi-square test was performed on the selectivity data to test the null hypothesis that strikes on each prey type occurred in proportion to the availability of each prey type in the environment, which was assumed to be 1/3 since prey types were presented in equal proportion. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of IBM SPSS version 19.0.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Jackson, J. M. and Lenz, P. H. Predator-prey interactions in the plankton: larval fish feeding on evasive copepods. Sci. Rep. 6, 33585; doi: 10.1038/srep33585 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank D.K. Hartline, J. Bailey-Brock, and C. Tamaru for their comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Special thanks to A. Taylor and A. Castelfranco for assistance with statistics, T. Murphy and H. Akaka for technical assistance, and K. Brittain for providing A. ocellaris eggs and her advice on larval rearing. The work was partly funded by a grant to C. Tamaru from the Center for Tropical and Subtropical Aquaculture (CTSA, USDA) and by NSF OCE 123549 to PHL and D.K. Hartline. This is SOEST contribution no. 9824.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.M.J. and P.H.L. conceived the study, J.M.J. completed the experiments and data analysis, J.M.J. and P.H.L. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Houde E. D. Emerging from Hjort’s shadow. J Northw Atl Fish Sci 41, 53–70 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Bergenius M. A., Meekan M. G., Robertson R. D. & McCormick M. I. Larval growth predicts the recruitment success of a coral reef fish. Oecologia 131, 521–525 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasuka A., Oozeki Y., Kimura R., Kubota H. & Aoki I. Growth-selective predation hypothesis revisited for larval anchovy in offshore waters: cannibalism by juveniles versus predation by skipjack tunas. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 278, 297–302. (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Rønnestad I. et al. Feeding behaviour and digestive physiology in larval fish: current knowledge, and gaps and bottlenecks in research. Rev Aquacult 5, S59–S98 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- China V. & Holzman R. Hydrodynamic starvation in first-feeding larval fishes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 8083–8088, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323205111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulzitski K. et al. Close encounters with eddies: oceanographic features increase growth of larval reef fishes during their journey to the reef. Biol Lett 11 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Figueiredo G. M., Nash R. D. & Montagnes D. J. The role of the generally unrecognised microprey source as food for larval fish in the Irish Sea. Mar Biol 148, 395–404 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- De Figueiredo G. M., Nash R. D. & Montagnes D. J. Do protozoa contribute significantly to the diet of larval fish in the Irish Sea? J Mar Biol Assoc UK 87, 843–850 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Sampey A., McKinnon A. D., Meekan M. G. & McCormick M. I. Glimpse into guts: overview of the feeding of larvae of tropical shorefishes. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 339, 243–257 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Llopiz J. K. & Cowen R. K. Variability in the trophic role of coral reef fish larvae in the oceanic plankton. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 381, 259–272 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Morote E., Olivar M. P., Villate F. & Uriarte I. A comparison of anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) and sardine (Sardina pilchardus) larvae feeding in the Northwest Mediterranean: influence of prey availability and ontogeny. ICES J Mar Sci 67, 897–908 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Llopiz J. K. Latitudinal and taxonomic patterns in the feeding ecologies of fish larvae: a literature synthesis. J Marine Syst 109 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Houde E. D. Comparative growth, mortality, and energetics of marine fish larvae: Temperature and implied latitudinal effects. Fish Bull 87, 471–495 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Houde S. E. L. & Roman M. R. Effects of food quality on the functional ingestion response of the copepod Acartia tonsa. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 40, 69–77 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Sponaugle S., Llopiz J. K., Havel L. N. & Rankin T. L. Spatial variation in larval growth and gut fullness in a coral reef fish. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 383, 239–249 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Leis J. M. & Clark D. L. Feeding greatly enhances swimming endurance of settlement-stage reef-fish larvae of damselfishes (Pomacentridae). Ichthyol Res 52, 185–188 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Lough R. G. & Mountain D. G. Effect of small-scale turbulence on feeding rates of larval cod and haddock in stratified water on Georges Bank. Deep-Sea Res Pt II 43, 1745–1772 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Carassou L., Le Borgne R. & Ponton D. Diet of pre-settlement larvae of coral-reef fishes: selection of prey types and sizes. J Fish Biol 75, 707–715 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard P., Munk P. & Janekarn V. Contrasting feeding patterns among species of fish larvae from the tropical Andaman Sea. Mar Biol 146, 595–606 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Munk P. & Kiørboe T. Feeding behaviour and swimming activity of larval herring (Clupea harengus) in relation to density of copepod nauplii. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 24, 15–21 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Von Herbing I. H. & Gallager S. M. Foraging behavior in early Atlantic cod larvae (Gadus morhua) feeding on a protozoan (Balanion sp.) and a copepod nauplius (Pseudodiaptomus sp.). Mar Biol 136, 591–602 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal H. Untersuchungen über das Beutefangverhalten bei Larven des Herings Clupea harengus. Mar Biol 3, 208–221 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal H. & Hempel G. In Marine Food Chains (ed Steele J. H.) 344–364 (University of California Press, 1970). [Google Scholar]

- Runge J. A. Should we expect a relationship between primary production and fisheries? The role of copepod dynamics as a filter of trophic variability. Hydrobiologia 167, 61–71 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Huys R. & Boxshall G. A. Copepod evolution (The Ray Society, Unwin Brothers, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- Humes A. G. How many copepods? Hydrobiologia, 292, 1–7 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Buskey E. J., Lenz P. H. & Hartline D. K. Sensory perception, neurobiology and behavioral adaptations for predator avoidance in planktonic copepods. Adapt Behav 20, 57–66 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Strickler J. R. & Bal A. K. Setae of the first antennae of the copepod Cyclops scutifer (Sars): Their structure and importance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70, 2656–2659 (1973). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen J., Lenz P. H., Gassie D. V. & Hartline D. K. Mechanoreception in marine copepods - electrophysiological studies on the 1st antennae. J Plankton Res 14, 495–512 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Hartline D. K., Lenz P. H. & Herren C. M. Physiological and behavioral studies of escape responses in calanoid copepods. Mar Freshw Behav Phy 27, 199–212 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Lenz P. H. & Hartline D. K. In Nervous Systems and Control of Behavior The Natural History of the Crustacea (eds Derby C. & Thiel M.) Ch. 11, 293–320 (Oxford University Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Weatherby T. M. & Lenz P. H. Mechanoreceptors in calanoid copepods: designed for high sensitivity. Arthropod Struct Dev 29, 275–288 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields D. M., Shaeffer D. S. & Weissburg M. J. Mechanical and neural responses from the mechanosensory hairs on the antennule of Gaussia princeps. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 227, 173–186 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Strickler J. R. In Swimming and Flying in Nature (eds Wu T. Y.-T., Brokaw C. J. & Brennan C.) 599–613 (Plenum Press, 1975). [Google Scholar]

- Buskey E. J., Lenz P. H. & Hartline D. K. Escape behavior of planktonic copepods in response to hydrodynamic disturbances: high speed video analysis. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 235, 135–146 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Burdick D. S., Hartline D. K. & Lenz P. H. Escape strategies in co-occurring calanoid copepods. Limnol Oceanogr 52, 2373–2385 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Lenz P. H. & Hartline D. K. Reaction times and force production during escape behavior of a calanoid copepod, Undinula vulgaris. Mar Biol 133, 249–258, doi: 10.1007/S002270050464 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz P. H., Hower A. E. & Hartline D. K. Force production during pereiopod power strokes in Calanus finmarchicus. J Marine Syst 49, 133–144, doi: 10.1016/J.Jmarsys.2003.05.006 (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz P. H., Hartline D. K. & Davis A. D. The need for speed. I. Fast reactions and myelinated axons in copepods. J Comp Physiol A 186, 337–345 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon A. D. et al. The potential of tropical paracalanid copepods as live feeds in aquaculture. Aquaculture 223, 89–106 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Bradley C. J., Strickler J. R., Buskey E. J. & Lenz P. H. Swimming and escape behavior in two species of calanoid copepods from nauplius to adult. J Plankton Res 35, 49–65, doi: 10.1093/Plankt/Fbs088 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P. J., Brown J. A., Gotceitas V. & Pepin P. Developmental changes in escape response performance of five species of marine larval fish. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 53, 1246–1253 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd T. D., Costain K. E. & Litvak M. K. Effect of development rate on the swimming, escape responses and morphology of yolk-sac stage larval American plaice Hippoglossoides platessoides. Mar Biol 137, 737–745 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. R. Swimming and feeding behavior of larval anchovy Engraulis mordax. Fish Bull 70, 821–838 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen J. & Strickler J. R. Encounter probabilities and community structure in zooplankton: a mathematical model. J Fish Res Board Can 34, 73–82 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Lasker R. Marine fish larvae: morphology, ecology, and relation to fisheries 87 (Sea Grant Program, Seattle: Washington, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin D. J. Suction prey capture by clownfish larvae (Amphiprion perideraion). Copeia 1994, 242–246 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Wellington G. M. & Victor B. C. Planktonic larval duration of one hundred species of Pacific and Atlantic damselfishes (Pomacentridae). Mar Biol 101, 557–567 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Green B. S. & McCormick M. I. Ontogeny of the digestive and feeding systems in the anemonefish Amphiprion melanopus. Environ Biol Fishes 61, 73–83 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Liew H. J., Ambak M. A. & Abol-Munafi A. B. False Clownfish - Breeding, Behavioral, Embryonic and Larval Development, Rearing and Management of Clownfish Under Captivity (LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin D. J., Strickler J. R. & Sanderson B. Swimming and search behaviour in clownfish, Amphiprion perideraion, larvae. Anim Behav 44, 427–440 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, T., A. & Balasubramanian T. Broodstock development, spawning and larval rearing of the false clownfish, Amphiprion ocellaris in captivity using estuarine water. Curr Sci India 97, 1483–1486 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. T. The annual cycle of zooplankton in a Long Island Estuary. Estuaries 5, 261–274 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Hopcroft R. R., Roff J. C. & Lombard D. Production of tropical copepods in Kingston Harbour, Jamaica: the importance of small species. Mar Biol 130, 593–604 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Lo W. T., Chung C. L. & Shih C. T. Seasonal distribution of copepods in Tapong Bay, southwestern Taiwan. Zool Stud 43, 464–474 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Hoover R. S. et al. Zooplankton response to storm runoff in a tropical estuary: bottom-up and top-down controls. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 318, 187–201 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Duggan S., McKinnon A. D. & Carleton J. H. Zooplankton in an Australian tropical estuary. Estuar Coast 31, 455–467 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon A. D., Duggan S., Carleton J. H. & Böttger-Schnack R. Summer planktonic copepod communities of Australia’s North West Cape (Indian Ocean) during the 1997–1999 El Niño/La Niña. J Plankton Res 30, 839–855 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon A. D., Duggan S. & De’ath G. Mesozooplankton dynamics in nearshore waters of the Great Barrier Reef. Estuar Coast Shelf S 63, 497–511 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Jungbluth M. J. & Lenz P. H. Copepod diversity in a subtropical bay based on a fragment of the mitochondrial COI gene. J Plankton Res 35, 630–643, doi: 10.1093/Plankt/Fbt015 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz P. H. The biogeography and ecology of myelin in marine copepods. J Plankton Res 34, 575–589, doi: 10.1093/Plankt/Fbs037 (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timm J. & Kochzius M. Geological history and oceanography of the Indo‐Malay Archipelago shape the genetic population structure in the false clown anemonefish (Amphiprion ocellaris). Mol Ecol 17, 3999–4014 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornils A. & Blanco-Bercial L. Phylogeny of the Paracalanidae giesbrecht, 1888 (Crustacea: Copepoda: Calanoida). Mol Phylogenet Evol 69, 661–672 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt R. J. & Holbrook S. J. Gape-limitation, foraging tactics and prey size selectivity of two microcarnivorous species of fish. Oecologia, 63, 6–12 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremigan M. T. & Stein R. A. Gape-dependent larval foraging and zooplankton size: implications for fish recruitment across systems. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 51, 913–922 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- DeVries D. R., Stein R. A. & Bremigan M. T. Prey selection by larval fishes as influenced by available zooplankton and gape limitation. T Am Fish Soc 127, 1040–1050 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Gill A. B. The dynamics of prey choice in fish: the importance of prey size and satiation. J Fish Biol 63, 105–116 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Holling C. S. The functional response of predators to prey density and its role in mimicry and population regulation. Mem Entomol Soc Can 97, 5–60 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- Drenner R. W., Strickler J. R. & O’Brien W. J. Capture probability: The role of zooplankter escape in the selective feeding of planktivorous fish. J Fish Res Board Can 35, 1370–1373 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Houde E. D. & Schekter R. C. Feeding by marine fish larvae: developmental and functional responses. Environ Biol Fishes 5, 315–334 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Peterson W. T. & Ausubel S. J. Diets and selective feeding by larvae of Atlantic mackerel Scomber scombrus on zooplankton. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 17, 65–75 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Russo T., Costa C. & Cataudella S. Correspondence between shape and feeding habit changes throughout ontogeny of gilthead sea bream Sparus aurata L., 1758. J Fish Biol 71, 629–656 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Jones W. R. & Janssen J. Lateral line development and feeding behavior in the mottled sculpin, Cottus bairdi (Scorpaeniformes: Cottidae). Copeia 1992, 485–492 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Yúfera M. & Darias M. J. The onset of exogenous feeding in marine fish larvae. Aquaculture 268, 53–63 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Scharf F. S., Juanes F. & Rountree R. A. Predator size-prey size relationships of marine fish predators: interspecific variation and effects of ontogeny and body size on trophic-niche breadth. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 208, 229–248 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Krebs J. M. & Turingan R. G. Intraspecific variation in gape–prey size relationships and feeding success during early ontogeny in red drum. Sciaenops ocellatus. Environ Biol Fishes 66, 75–84 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Lenz P. H., Weatherby T. M., Weber W. & Wong K. K. Sensory specialization along the first antenna of a calanoid copepod, Pleuromamma xiphias (Crustacea). Mar Freshw Behav Phy 27, 213–221 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. D., Weatherby T. M., Hartline D. K. & Lenz P. H. Myelin-like sheaths in copepod axons. Nature (London) 398, 571–571 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenici P. The scaling of locomotor performance in predator–prey encounters: from fish to killer whales. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 131, 169–182 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R. D., Buskey E. J. & Marsden K. C. Effects of water motion and prey behavior on zooplankton capture by two coral reef fishes. Mar Biol 146, 1145–1155 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Gemmell B. J., Sheng J. & Buskey E. J. Morphology of seahorse head hydrodynamically aids in capture of evasive prey. Nat Commun 4 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggett R. J. & Buskey E. J. Calanoid copepod escape behavior in response to a visual predator. Mar Biol 150, 599–607 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Titelman J. & Kiørboe T. Predator avoidance by nauplii. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 247, 137–149 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon A. D. & Duggan S. Summer copepod production in subtropical waters adjacent to Australia’s North West Cape. Mar Biol 143, 897–907 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Chesson J. The estimation and analysis of preference and its relatioship to foraging models. Ecology 64, 1297–1304 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. T. The importance of small planktonic copepods and their roles in pelagic marine food webs. Zool Stud 43, 255–266 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth D. Modulation of attack behavior and its effect on feeding performance in a trophic generalist fish. J Exp Biol 200, 2155–2164 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderLugt K., Cooney M. J., Lechner A. & Lenz P. H. Cultivation of the paracalanid copepod, Bestiolina similis (Calanoida: Crustacea). J World Aquacult Soc 40, 616–628 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- VanderLugt K. & Lenz P. H. Management of nauplius production in the paracalanid, Bestiolina similis (Crustacea: Copepoda): effects of stocking densities and culture dilution. Aquaculture 276, 69–77 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J. M. Larval clownfish Amphiprion ocellaris predatory success and selectivity when preying on the calanoid copepod Parvocalanus crassirostris M.S. thesis, University of Hawaii at Manoa, (2011).

- Frakes T. & Hoff F. H. Effect of high nitrate-N on the growth and survival of juvenile and larval anemonefish, Amphiprion ocellaris. Aquaculture 29, 155–158 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Arvedlund M., McCormick M. I. & Ainsworth T. Effects of photoperiod on growth of larvae and juveniles of the anemonefish Amphiprion melanopus. Naga, The ICLARM Quarterly 23, 18–23 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Shirota A. Studies on the mouth size of fish larvae. Bull Jpn Soc Sci Fish 36, 353–367 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- Guma’a S. A. The food and feeding habits of young perch, Perca fluviatilis, in Windermere. Freshw Biol 8, 177–187 (1978). [Google Scholar]