Abstract

The UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 2B enzymes are important in the detoxification of a variety of endogenous and exogenous compounds, including many hormones, drugs, and carcinogens. Identifying novel mechanisms governing their expression is important in understanding patient-specific response to drugs and cancer risk factors. In silico prediction algorithm programs were used to screen for microRNAs (miRNAs) as potential regulators of UGT2B enzymes, with miR-216b-5p identified as a potential candidate. Luciferase data suggested the presence of a functional miR-216b-5p binding motif within the 3′ untranslated regions of UGTs 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10. Overexpression of miR-216b-5p mimics significantly repressed UGT2B7 (P < 0.001) and UGT2B10 (P = 0.0018) mRNA levels in HuH-7 cells and UGT2B4 (P < 0.001) and UGT2B10 (P = 0.018) mRNA in Hep3B cells. UGT2B7 protein levels were repressed in both HuH-7 and Hep3B cells in the presence of increasing miR-216b-5p concentrations, corresponding with significant (P < 0.001 and P = 0.011, respectively) decreases in glucuronidation activity against the UGT2B7-specific substrate epirubicin. Inhibition of endogenous miR-216b-5p levels significantly increased UGT2B7 mRNA levels in HuH-7 (P = 0.021) and Hep3B (P = 0.0068) cells, and increased epirubicin glucuronidation by 85% (P = 0.057) and 50% (P = 0.012) for HuH-7 and Hep3B cells, respectively. UGT2B4 activity against codeine and UGT2B10 activity against nicotine were significantly decreased in both HuH-7 and Hep3B cells (P < 0.001 and P = 0.0048, and P = 0.017 and P = 0.043, respectively) after overexpression of miR-216b-5p mimic. This is the first evidence that miRNAs regulate UGT 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10 expression, and that miR-216b-5p regulation of UGT2B proteins may be important in regulating the metabolism of UGT2B substrates.

Introduction

The UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B (UGT2B) gene subfamily is involved in the metabolic clearance of numerous endogenous compounds, including bile acids and steroid hormones, as well as exogenous agents including a variety of carcinogens and drugs (Stingl et al., 2014). UGT2B enzymes are well expressed in the liver (Ohno and Nakajin, 2009), and identifying novel mechanisms of their regulation may provide insight into UGT2B enzymatic activity and overall metabolic response in humans.

The UGT2B gene family consists of seven isoforms: UGTs 2B4, 2B7, 2B10, 2B11, 2B15, 2B17, and 2B28 (Mackenzie et al., 2005). The UGT2B genes contain six coding exons with unique, individual promoters and individual 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) (Mackenzie et al., 2005, 2010). Given that the UGT2B gene subfamily exhibits >70% DNA sequence homology with one another (Riedy et al., 2000; Guillemette et al., 2010), they appear to have evolutionarily arisen through successive rounds of gene duplication and replication slippage. All UGT2B isoforms, excluding UGT2B28, are well expressed in the liver in addition to extrahepatic tissues involved in metabolism, including stomach, colon, small intestine, and kidney (Nakamura et al., 2008; Ohno and Nakajin, 2009; Jones and Lazarus, 2014). In addition, several UGT2B isoforms are highly expressed in extrahepatic tissues locally influenced by UGT2B substrates. For instance, UGT2B15 and UGT2B17 metabolize multiple sex steroid hormones, including dihydrotestosterone, androsterone, and epiestradiol (Chouinard et al., 2007; Itaaho et al., 2008), and exhibit high expression in steroidogenic tissues, including breast, prostate, ovaries, uterus, and testes (Nakamura et al., 2008).

Although the levels of combined hepatic mRNA expression of the UGT2B gene family are close to 70% of total hepatic UGT mRNA abundance, there is also a high degree of variability in the hepatic expression of all UGT2B isoforms (Izukawa et al., 2009). UGT2B7 protein levels can vary >4-fold (Izukawa et al., 2009; Sato et al., 2012), and there is no correlation between UGT2B7 mRNA and UGT2B7 protein levels within individual human liver tissue samples (Izukawa et al., 2009; Ohtsuki et al., 2012). A potential mechanism for regulating the expression of UGT2B7 and other UGT2B genes is by microRNAs (miRNAs). miRNAs are single-stranded RNAs approximately 22 nucleotides in length that, when coupled with the RNA-induced silencing complex, bind to target mRNA 3′ UTRs and inhibit protein translation, thereby reducing protein expression (Bartel, 2009; Carthew and Sontheimer, 2009). miRNA can also decrease target mRNA levels, but this effect is dependent on the concentrations of both the target mRNA and miRNA genes (Baek et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2010; Mukherji et al., 2011). Due to their imperfect binding, miRNAs are highly promiscuous and can regulate several different genes at a given time. Reciprocally, many mRNAs can be targeted by several different miRNAs at the same time (Brennecke et al., 2005; Brodersen and Voinnet, 2009). miRNAs are also involved in the regulation of multiple members of a single pathway, including upstream transcriptional regulators, and this complexity contributes to their role as fine-tuners of protein expression. For example, miR-27b regulates the expression of CYP3A4 in human pancreatic cancer cells and also regulates the expression of the vitamin D receptor—an upstream transcriptional inducer of CYP3A4 (Pan et al., 2009).

Previous studies have identified miR-491-3p as a novel miRNA regulator of UGT1A gene expression (Dluzen et al., 2014). miR-491-3p expression levels were shown to be inversely correlated with UGT1A3 and UGT1A6 mRNA levels in normal human liver and contributed to observed interindividual variability of UGT1A gene expression (Dluzen et al., 2014). Recent studies have demonstrated that miR-376c exhibits an inverse expression level with the androgen-metabolizing UGTs 2B15 and 2B17 in prostate cancer cells (Wijayakumara et al., 2015). The opposite relationship between miR-376c and UGT2B15/UGT2B17 expression was shown in healthy prostate tissue, suggesting that low expression of miR-376c may contribute to prostate cancer development in androgen-dependent tumors by dysregulation of androgen signaling (Wijayakumara et al., 2015; Margaillan et al., 2016).

In the present study, evidence is provided that miR-216b-5p regulates the expression of several UGT2B genes, including UGTs 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents.

The pGL3-Promoter luciferase and pRL-TK renilla plasmids were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). All synthesized DNA oligonucleotides used for 3′ UTR amplification, site-directed mutagenesis (SDM), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis were from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA) or Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent was from Life Technologies. miRVana miRNA miR-216b-5p mimic (#MC12302), miRVana negative control mimic #1 (#4464058), miRVana miRNA miR-216b-5p inhibitor (#12302), and negative control inhibitor #1 (#4464076) were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). Codeine and (−)-nicotine, uridine 5′-diphosphoglucuronic acid, alamethicin, and bovine serum albumin were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Epirubicin hydrochloride was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada). Rabbit anti-UGT2B7 and anti–β-actin antibodies were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) and Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), respectively. All other chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA) unless specified otherwise.

Cells and Culture Conditions.

Human embryonic kidney cell line 293 (HEK293), human liver adenocarcinoma cell line SK-HEP-1, human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines HepG2 and Hep3B, colon adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2, human breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF-7, and human lung carcinoma cell line A-549 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HuH-7 was a kind gift from Dr. Jianming Hu (Penn State University, Hershey, PA). Hep3B, HEK293, A-549, and HuH-7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). SK-HEP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% nonessential amino acids. HepG2 and Caco-2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% nonessential amino acids (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). MCF-7 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were grown and maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Tissues and miRNA Isolation.

Pathologically normal colon and endometrium specimens (n = 5 each) were obtained from the tissue bank at Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine (Hershey, PA). Pathologically normal liver specimens (n = 5) and their matching total RNA were obtained from the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center Tissue Procurement Facility (Tampa, FL). All protocols involving the collection and analysis of tissue specimens from these tissue banks were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at their respective institutions and were in accordance with assurances filed with and approved by the United States Department of Health and Human Services. Normal jejunum tissue specimens were purchased from the Sun Health Research Institute (Sun City, AZ). All tissue samples were isolated and frozen at −70°C within 3 hours postsurgery. Colon, liver, jejunum, endometrium, and cell line total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Total RNA samples from cell lines were subject to on-column DNase digestion during RNA purification (Qiagen). Pooled breast total RNA was purchased from the Biochain Institute (Hayward, CA), whereas lung, pancreas, larynx, trachea, and kidney RNA was purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA) or Agilent (Santa Clara, CA). Small RNA (<200 nt) containing the miRNA fraction was isolated and purified from total RNA using the miRVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion). RNA concentrations were determined using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and were eluted and stored as aliquots in RNase-, DNAse-free water in a −80°C freezer.

miRNA Binding Site Predictions.

The 3′ UTR sequences of UGT2B enzymes were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Reference Sequence Database. miRNA binding site predictions were obtained using 1) TargetScan Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA (Lewis et al., 2005), scored with the Total Context+ score as described by Garcia et al. (2011), and 2) miRanda Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, algorithm v3.0 (Betel et al., 2008) with the following parameters: gap open penalty, −8.00; gap extend, −2.00; score threshold, 50.00; energy threshold, −20.00 kcal/mol; scaling parameter, 4.00.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR.

cDNAs were synthesized from total RNA using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). miRNA cDNAs were synthesized using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Ambion). TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) were used to quantify UGT2B7 (Hs_02556232_s1); UGT2B4 (Hs_02383831_s1); UGT2B10 (Hs_02556282_s1); UGT2B11 (Hs_01894900_gH); UGT2B15 (Hs_00870076_s1); UGT2B17 (Hs_00854486_sH); and ribosomal protein, large, P0 (RPLP0) (Hs99999902_m1). TaqMan microRNA assays (Ambion) were used to quantify miR-216b-5p (catalog #4427975, identifier #002326) and RNU6B endogenous control (catalog #4427975, identifier #001093) in all cell lines and tissue samples. PCR reactions were performed in 10-µl reactions in 384-well plates using an ABI 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), with incubations performed at 50°C for 2 minutes and 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. Reactions included 2× Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), TaqMan gene expression primers or TaqMan miRNA primers, and corresponding cDNA, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Each plate included a no-DNA negative control, and all reactions were performed in quadruplicate. Gene expression was compared with an endogenous, internal control (RPLP0 for mRNA or RNU6B for miRNA) using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). CT values were determined using SDS 2.4 software (Applied Biosystems), and amplification CT values higher than 40 cycles were designated as below the limit of detection.

Construction of Reporter Plasmids.

The luciferase reporter plasmids used in this study were constructed by inserting the 3′ UTRs of UGTs 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10 into the XbaI restriction site downstream of the luciferase reporter gene in the pGL3-Promoter vector. In brief, primers containing an XbaI restriction enzyme site (see Table 1) were used to amplify UGT2B 3′ UTRs using genomic DNA isolated from the HEK293 cell line. Two sets of primers were used to amplify the 3′ UTR of UGT2B7 because of sequence similarities with other UGT2B genes: UGT2B7 “outer primers” amplified the UGT2B7 3′ UTR containing 5′ upstream exon and 3′ downstream intergenic DNA sequences, and UGT2B7 “inner primers” amplified the UGT2B7 3′ UTR from the resulting PCR product from the “outer primers” amplification. Each amplified region was cloned into the XbaI restriction site of the pGL3-Promoter vector. The miR-216b-5p seed deletion plasmids were created by performing SDM using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent) and the forward and reverse mutagenesis primers listed in Table 1. A UGT2B10 vector containing the A>G single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at position 155 of the UGT2B10 3′ UTR was created by SDM with the pGL3-Promoter vector containing the “wild-type” UGT2B10 3′ UTR sequence as a template and primers whose sequences are also listed in Table 1. Nucleotide sequences of all plasmids used in this study were confirmed by DNA sequencing analysis performed at the Pennsylvania State University Nucleic Acids Core Facility (State College, PA).

TABLE 1.

List of PCR primers used for UGT2B 3′ UTR PCR amplification, cloning, and luciferase mutational analysis

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Outer UGT2B7 3′ UTR For | 5′ – CCTTCGGGTTGCAGCCCACGAC – 3′ |

| Outer UGT2B7 3′ UTR Rev | 5′ – ATAGGCTCTCAGGATTCAGAGGGGAGGG – 3′ |

| Inner UGT2B7 3′ UTR For | 5′ – GCTATCTAGAGTTATATCTGAGATTTGAAGCTGGAAAACC – 3′ |

| Inner UGT2B7 3′ UTR Rev | 5′ – GCTATCTAGATAAGGCTTTATCTTATTTTTTATTTTCCG – 3′ |

| UGT2B4 3′ UTR For | 5′ – GCTATCTAGATTACGTCTGAGGCTGGAAGCTG – 3′ |

| UGT2B4 3′ UTR Rev | 5′ – GCTATCTAGACACAATCCTGCATGAAATGATCC – 3′ |

| UGT2B10 3′ UTR For | 5′ – GCTATCTAGAGGGATTAGTTATATCTGAGATTTGAAGCTGG – 3′ |

| UGT2B10 3′ UTR Rev | 5′ – GCTATCTAGACCTAAGTCATCATGACCATGGCTCAGAGTG – 3′ |

| UGT2B7 216b Del. SDM For | 5′ – CCTTGTCAAATAAAAATTTGTTTTTCAGTTACCACCCAGTTCATGGTT – 3′ |

| UGT2B7 216b Del. SDM Rev | 5′ – TAACCATGAACTGGGTGGTAACTGAAAAACAAATTTTTATTTGACAAAG – 3′ |

| UGT2B4 216b Del. SDM For | 5′ – TTATTACAACAATAAGACGTTGTGATACAATTCCTTTCTTCTTGTG – 3′ |

| UGT2B4 216b Del. SDM Rev | 5′ – CACAAGAAGAAAGGAATTGTATCACAACGTCTTCTTGTTGTAATAA – 3′ |

| UGT2B10 216b Del. SDM For | 5′ – CTACCTTGTCAAGTAAAATTTGTTTTTCATTTACCACCCAGTTAATG – 3′ |

| UGT2B10 216b Del. SDM Rev | 5′ – CCATTAACTGGGTGGTAAATGAAAAACAAATTTTTACTTGACAAGGTAG – 3′ |

| UGT2B10 SNP rs139538767 SDM For | 5′ – CAAGTAAAAATTTGTTTTTCAGAGGTTTACCACCCAGTTAATGGTTAG – 3′ |

| UGT2B10 SNP rs139538767 SDM Rev | 5′ – CTAACCATTAACTGGGTGGTAAACCTCTGAAAAACAAATTTTTACTTG – 3′ |

| miR-216b-5p | 5′ – AAATCTCTGCAGGCAAATGTGA – 3′ |

Del, deletion; For, forward; Rev, reverse. Underlined sequences refer to the XbaI enzyme recognition site within the primer.

Luciferase Assays.

The pGL3-Promoter vector cloned with each 3′ UTR was cotransfected with the pRL-TK renilla control vector and miRVana miRNA mimics into HEK293 cells. The day before transfection, HEK293 cells were seeded onto 24-well plates at 50,000 cells/well, and after 24 hours were cotransfected with 380 ng of UGT2B 3′ UTR–containing pGL3 plasmid and 20 ng of the pRL-TK plasmid together with either scrambled miRNA control or various concentrations of miRNA mimic, using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Transfected HEK293 cells were harvested 24 hours post-transfection using passive lysis buffer, and luciferase activity was measured with a luminometer (BioTek Synergy HT, Winooski, VT) using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). All luciferase assay experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western Blot Analysis.

UGT2B7 and β-actin protein levels were determined via immunoblotting. For each Western blot, 15 µg of cellular homogenate and loading buffer was heated at 90°C for 10 minutes. Samples were run at 90 V on a 12% acrylamide gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene diflouride membrane for 2 hours at 33 V. Polyvinylidene diflouride membranes were blocked in 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 for 1 hour, probed with primary antibody (1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4°C, washed 3×, and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (1:5000 dilution). Protein bands were visualized using the Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) and Hyoblot CL autoradiography film (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ). UGT2B7 protein blots were stripped and reprobed for β-actin, which served as the loading control.

Glucuronidation Assays.

Cell homogenates for glucuronidation activity assays were harvested 48 hours post-transfection. HuH-7 or Hep3B cells were transfected with either scrambled miRNA controls, various concentrations of miR-216b-5p mimic, or 100 nM miR-216b-5p inhibitor using 30–50 ul of Lipofectamine 2000 in 10-cm dishes, according to the manufacturer’s protocol, as previously described (Dellinger et al., 2007). Collected cell pellets were subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles and three 10-second pulses using a hand-held Bio-Vortexer (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK) prior to storage at −80°C. Protein concentration was quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) and measured using either an Appliskan Luminometer with SkanIT Software v2.3 (Thermo Scientific) or the Synergy Neo and Gen5 Data Analysis Software (BioTek).

The glucuronidation assays using homogenates from HuH-7 and Hep3B cells were performed as described previously (Sun et al., 2007, 2013). HuH-7 and Hep3B cell homogenate (50–300 µg of protein) was incubated at 37°C with 500 µM epirubicin hydrochloride for 60 minutes for UGT2B7, 1 mM codeine for 90 minutes for UGT2B4, and 500 µM nicotine for 14 hours for UGT2B10. Epirubicin and nicotine reactions were terminated in the presence of cold 100% acetonitrile, whereas codeine reactions were terminated in the presence of cold 1:1 methanol:acetonitrile. Reactions were centrifuged for 20 minutes at 13,000g, and supernatant was collected for analysis on ultra-pressure liquid chromatography (UPLC)/tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS).

Epirubicin-glucuronide formation was analyzed using an ACQUITY UPLC/MS/MS system (Waters, Milford, MA) with a 1.7-µ ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 analytical column (2.1 × 50 mm; Waters, Milford, MA) in series with a 0.2-µm Waters assay frit filter (2.1 mm). Epirubicin gradient elution conditions were performed using a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, starting with 95% buffer A (0.1% formic acid) and 5% buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) for 30 seconds, a subsequent linear gradient to 50% buffer B over 2.5 minutes, and then 100% buffer B maintained over the next 2 minutes. Epirubicin glucuronides were confirmed by their sensitivity to the treatment of β-glucuronidase. Characterization of epirubicin and epirubicin-glucuronide was conducted using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) with transitions m/z 544 to 130 for epirubicin and m/z 720 to 113 for epirubicin-glucuronide. Since an epirubicin-glucuronide standard is not commercially available, quantification was based on the ratio of the area under the curves for epirubicin-glucuronide versus total epirubicin (epirubicin + epirubicin-glucuronide) and the amount of epirubicin (500 µM) added to each glucuronidation assay reaction tube. Data were quantified using the MassLynx NT 4.1 software within the QuanLynx program (Waters). All experiments were performed three to five times in independent assays.

Codeine gradient elution conditions were performed as described earlier using a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, starting with 80% buffer A (0.1% formic acid) and 20% buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) for 1 minute, followed by 100% buffer B over the next 2 minutes, then 20% buffer B through the remainder of the 6-minute run. The codeine-glucuronide was identified by the transition m/z 476.2 to 300.2, and codeine was identified by the single m/z of 300.372. Identification of codeine-glucuronide was confirmed by a d3-labeled codeine-glucuronide internal standard. Quantification was based on a ratio of codeine-glucuronide to codeine to maintain consistency across all activity assays for UGT2B enzymes. Data were quantified using the MassLynx NT 4.1 software with the TargetLynx program (Waters). All experiments were performed in triplicate in independent assays.

Nicotine glucuronides were analyzed using a QTRAP 6500 LC-MS/MS System (Sciex, Framingham, MA) with a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH HILIC 1.7-µm analytic column (2.1 × 100 mm). Nicotine elution gradient conditions were performed with a 0.4-ml/min flow rate, starting with 80% buffer B (5 mM NH4Ac in 90% acetonitrile) for 1 minute and 50 seconds, followed by a steep gradient to 100% buffer A (5 mM NH4Ac in 60% acetonitrile) for 3 minutes, and then back to 80% buffer B for the remainder of the 10-minute run. Identification of nicotine-glucuronide was confirmed by a d3-labeled codeine-glucuronide internal standard. The transition m/z was 339.456 to 163.100 for nicotine-glucuronide, and nicotine was identified by the transition m/z of 163.100 to 106 and quantified based on the ratio of nicotine-glucuronide to nicotine using 500 µM per reaction. Data were quantified using MultiQuant 2.1 software SCITEX, Concord, Ontario, Canada and performed in triplicate from independent assays.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). For all studies involving miR-216b-5p miRNA mimic or miR-216b-5p inhibitors, Student’s t test (two-tailed) and the linear trend test were used to compare experimental groups with scrambled miRNA controls. For statistical analysis of expression levels of genes labeled below the limit of detection, a CT value of 40 was assigned to generate the necessary 2-ΔΔCT values needed for statistical comparison. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

miR-216b-5p Is Predicted to Bind to the 3′ UTR of Several UGT2B Genes.

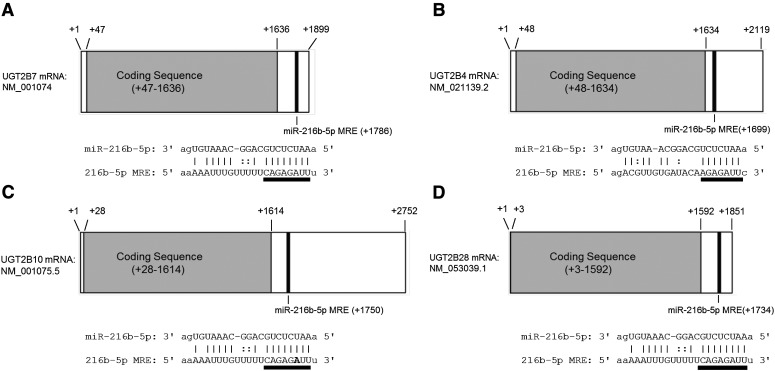

The miRanda and TargetScan miRNA prediction algorithms were used to analyze 3′ UTR sequences from mRNA encoding wild-type, active UGT2B7 (NM_001074), UGT2B4 (NM_021139.2), UGT2B10 (NM_001075.5), UGT2B11 (NM_001073.1), UGT2B15 (NM_001076.2), UGT2B17 (NM_001077.2), and UGT2B28 (NM_053039.1) for potential miRNA binding sites. miR-216b-5p, a conserved miRNA among vertebrates, was the only miRNA candidate to consistently score within the top three predicted miRNA candidates by both programs for several UGT2B genes, including UGTs 2B7, 2B4, 2B10, and 2B28. The only prediction score that fell out of the “top three” for miR-216b-5p was for UGT2B4 predicted by miRanda, where miR-216b-5p was 10th among predicted miRNA candidates. miR-216b-5p was predicted to bind within the 3′ UTR of UGT2B15 by miRanda but not by TargetScan, and was not predicted to bind to the 3′ UTR of UGTs 2B11 or 2B17 by either program. Previous studies have demonstrated high expression of miR-216b-5p in UGT2B-expressing tissues, including pancreas, liver, and other metabolic tissues, suggesting that this miRNA could be a strong candidate miRNA for regulating UGT2B expression (Endo et al., 2013)

The UGT2B7 3′ UTR contains one potential miR-216b-5p miRNA recognition element (MRE) within its 3′ UTR, located 150 nt from the UGT2B7 stop codon (between nt 1786 and 1809 relative to the 5′ end of the UGT2B7 transcript; Fig. 1A). miR-216b-5p MREs were predicted for UGTs 2B4, 2B10, and 2B28 at 65, 136, and 142 nt 3′ of their respective translation stop codons (Fig. 1, B–D). All of the predicted miR-216b-5p MREs contained “seed” sequences of 7 (UGT2B4) or 8 (UGTs 2B7, 2B10, and 2B28) nt of perfect complementarity, which is associated with a greater translation downregulation (Brennecke et al., 2005).

Fig. 1.

In silico prediction and binding of miR-216b-5p to UGT2B isoforms. The miRNA prediction algorithms miRanda and TargetScan were used to identify miRNA binding candidates for all seven UGT2B isoform mRNAs. miR-216b-5p is predicted to bind to a 3′ UTR MRE located within each of the UGT2B7 (A), UGT2B4 (B), UGT2B10 (C), and UGT2B28 (D) 3′ UTR mRNA sequences (black bars). The canonical seed sequences of the predicted hybridization between miR-216b-5p and each 3′ UTR are located underneath each gene and underlined in black. The nucleotide that constitutes an SNP within the UGT2B10 MRE is in bold.

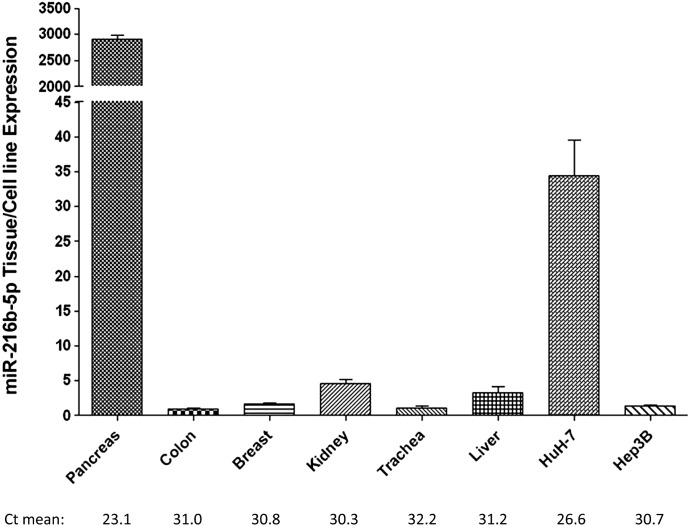

Tissue and Cell Line Expression of miR-216b-5p.

To determine the levels of expression of miR-216b-5p in tissues and cells with known UGT2B expression, total RNA was screened by real-time PCR. miR-216b-5p expression was highest in pancreas (2897 ± 166), followed by kidney (4.6 ± 0.98) > liver (3.3 ± 1.6) > breast (1.6 ± 0.46) > trachea (1.1 ± 0.68) > colon (1.0 ± 0.20, set as the reference; Fig. 2). Higher levels of miR-216b-5p were observed in the hepatic HuH-7 cell line (34 ± 8.8) as compared with the Hep3B cell line (1.4 ± 0.27; Fig. 2), with the Hep3B levels comparable to those observed in multiple human tissues, including liver. Low levels of miR-216b-5p expression were observed in normal human lung, the lung A-549 cell line, and the HEK293 cell line; no expression was detected in normal larynx, jejunum, or endometrium, or in the SK-HEP-1, HepG2, MCF-7, and Caco-2 cell lines (results not shown).

Fig. 2.

Tissue and cell line expression of miR-216b-5p. Expression levels of miR-216b-5p were quantified using qRT-PCR and set relative to the lowest-expressing tissue (i.e., colon). miR-216b-5p expression is adjusted to the RNU6B endogenous control gene in the same samples. The y-axis is broken into two segments, with a gap between 45 and 2000 to better adjust for the high expression levels quantified in the pancreas. The mean CT values are listed below the table. Columns represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent replicates.

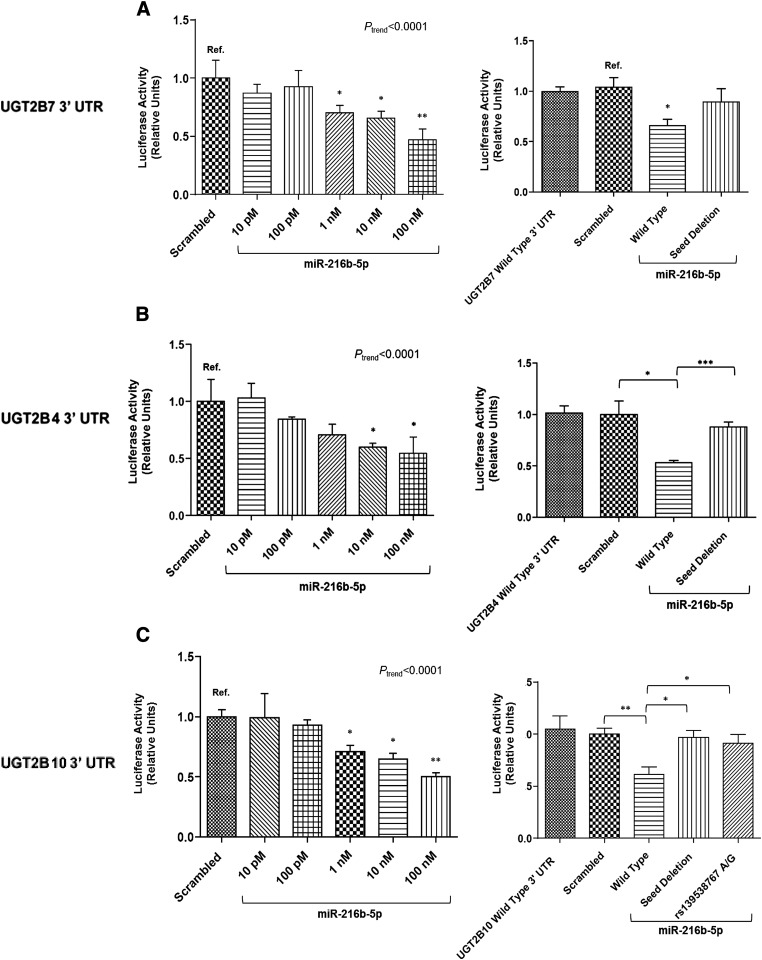

In Vitro Validation of miR-216b-5p Target Predictions.

In vitro validation of the in silico miR-216b-5p target predictions was performed for the well expressed hepatic enzymes, UGTs 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10. Analysis was not performed for UGT2B28 given its low levels of expression in human tissues, including human liver (Ohno and Nakajin, 2011). The UGT2B7 3′ UTR was cloned downstream of a luciferase reporter gene and transiently transfected into HEK293 cells with increasing concentrations of miR-216b-5p miRNA mimic. A significant dose-dependent repression of luciferase activity was observed for the UGT2B7 3′ UTR in response to increasing concentrations of miR-216b-5p (Ptrend < 0.0001), with luciferase activity significantly reduced in the presence of 1 (P = 0.037), 10 (P = 0.023), and 100 nM (P = 0.0071) miR-216b-5p mimic (Fig. 3A, left). To determine if the predicted UGT2B7 miR-216b-5p MRE is the functional binding site for the interaction between miR-216b-5p and the UGT2B7 3′ UTR, four nucleotides were deleted within the UGT2B7 3′ UTR luciferase vector MRE by site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 1A, underlined). Luciferase activity returned to that of control in the presence of 10 nM miR-216b-5p mimic for HEK293 cells overexpressing the mutated UGT2B7 3′ UTR-containing luciferase vector (Fig. 3A, right). These results suggest that miR-216b-5p functionally binds to the predicted MRE on the UGT2B7 3′ UTR, and that the interaction causes a decrease in expression of the luciferase gene.

Fig. 3.

UGT2B 3′ UTR luciferase activity in the presence of miR-216b-5p mimics. Luciferase activity of the UGT2B7 (A, left), UGT2B4 (B, left), and UGT2B10 (C, left) 3′ UTR luciferase reporter vectors cotransfected with increasing concentrations of miR-216b-5p mimic or scrambled (100 nM) miRNA control in HEK293 cells. Luciferase activity was also examined in the presence of 10 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p mimic after each UGT2B miRNA response element was mutated within the miR-216b-5p seed sequence (seed deletion columns; right panels). Luciferase activity of the UGT2B10 3′ UTR variant SNP in the presence of 10 nM miR-216b-5p was also measured (C, right). Columns represent the mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments and are normalized to the scrambled miRNA-transfected control. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Similar to that observed for UGT2B7, a significant dose-dependent repression of luciferase activity in response to increasing concentrations of miR-216b-5p after transfection of HEK293 cells was observed for both the UGT2B4 (Ptrend < 0.0001) and UGT2B10 (Ptrend < 0.0001) 3′ UTRs. For the UGT2B4 3′ UTR, the reduction of luciferase activity was significant at 10 (P = 0.024) and 100 nM (P = 0.031) miR-216b-5p (Fig. 3B, left). The luciferase activity of cell homogenates transfected with the UGT2B10 3′ UTR–containing vector decreased at 1 (P = 0.020), 10 (P = 0.010), and 100 nM (P = 0.0018) miR-216b-5p (Fig. 3C, left). Deletion of four nucleotides within the predicted miR-216b-5p “seed” sequences of each of the UGT2B 3′ UTR–containing luciferase vectors resulted in a reversal of this repression (Fig. 3, B and C, right). These results validate the in silico data and suggest that miR-216b-5p can bind with multiple UGT2B mRNAs.

A Functional miR-216b-5p Binding Site Polymorphism in the UGT2B10 3′ UTR.

Analysis of the UGT2B10 3′ UTR mRNA sequence within the SNP500Cancer Project database (Packer et al., 2004) identified a low-prevalence (∼1% in Caucasians) SNP (rs139538767) consisting of an adenine (A) to guanine (G) transition located within the predicted miR-216b-5p MRE of the 3′ UTR of UGT2B10 (Fig. 1C, bold, underlined). A UGT2B10 3′ UTR luciferase reporter vector containing the G variant was created to ascertain whether this polymorphism conferred an effect on the binding of miR-216b-5p. In contrast to the significant repression of luciferase activity observed with the wild-type UGT2B10 3′ UTR, the G variant UGT2B10 3′ UTR exhibited no repression of luciferase activity, a pattern similar to that observed for the “seed” deletion control (Fig. 3C, right). These data suggest that SNPs in MREs lying within a UGT mRNA 3′ UTR could potentially result in differential regulation of UGT expression and possibly glucuronidation activities between individuals.

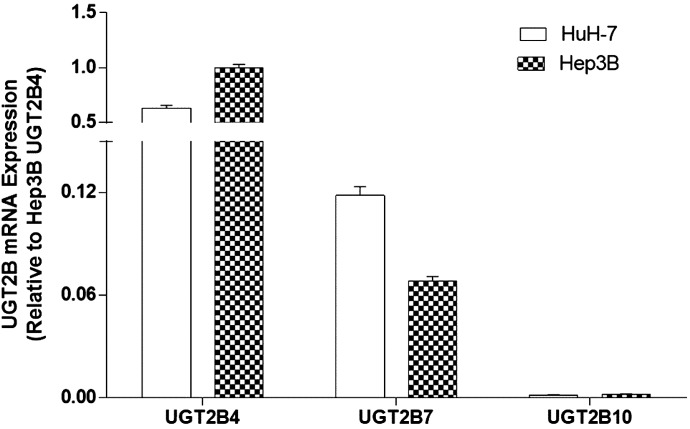

Effects of miR-216b-5p on UGT2B mRNA Expression in Hepatic Cell Lines.

The relative expression levels of UGT2B7, UGT2B4, and UGT2B10 were examined in the HuH-7 and Hep3B cell lines. HuH-7 and Hep3B cells were chosen because both cell lines express multiple UGT2B enzymes (Guo et al., 2011) and endogenously express miR-216b-5p (Fig. 2), and could therefore potentially serve as an in vitro model for miR-216b-5p UGT2B interactions. As determined by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR), UGT2B4 exhibited the highest level of mRNA expression of any UGT2B isoform, with Hep3B UGT2B4 mRNA expression the highest overall in both cell lines (reference set at 1.0; Fig. 4). In HuH-7 cells, UGT2B4 expression levels were 63% that of Hep3B UGT2B4 mRNA levels; UGT2B7 expression was 0.07 (Hep3B) and 0.12 (HuH-7) that observed for UGT2B4 in Hep3B cells, whereas UGT2B10 expression was very low in both cell lines.

Fig. 4.

UGT2B mRNA expression in HuH-7 and Hep3B cells. UGT2B mRNA expression was quantified in HuH-7 and Hep3B cells using qRT-PCR. mRNA expression was determined using RPLP0 as an internal endogenous control and expressed relative to the highest-expressing UGT2B mRNA transcript, UGT2B4, in Hep3B cells (set at 1.0 as the reference). The y-axis contains a gap between 0.15 and 0.50 to better adjust for high UGT2B4 expression levels. Columns represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent replicates.

To determine if miR-216b-5p interacts with endogenous UGT2B mRNAs, 50 nM miR-216b-5p miRNA mimic was transfected into the HuH-7 and Hep3B cell lines, and mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR. Decreases in the mRNA levels were observed after overexpression of miR-216b-5p in HuH-7 and Hep3B cells for UGTs 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10 (Fig. 5). Significant decreases were observed for UGT2B7 in HuH-7 cells (P < 0.001; Fig. 5A), UGT2B4 in Hep3B cells (P < 0.001; Fig. 5B), and UGT2B10 in both cell lines (P = 0.0018 for HuH-7 cells and P = 0.018 for HepG2 cells; Fig. 5, A and B, respectively). No effect was observed for other hepatic UGT2B enzymes, including UGTs 2B11, 2B15, and 2B17, in either cell line after overexpression of miR-216b-5p (results not shown).

Fig. 5.

UGT2B mRNA levels in HuH-7 and Hep3B cells with miR-216b-5p mimic or inhibitor. mRNA levels of UGT2B7, UGT2B4, and UGT2B10 in HuH-7 (A) and Hep3B (B) cells after transfection with 50 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p mimic were quantified by qRT-PCR relative to the endogenous internal control gene RPLP0. mRNA levels for each gene are shown relative to the scrambled control (set at 1.0 as the reference). Endogenous expression levels of miR-216b-5p were quantified using qRT-PCR in the presence of 100 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p inhibitor in HuH-7 (C) and Hep3B (D) cells. miR-216b-5p expression levels were quantified against the RNU6B endogenous internal miRNA control gene, and each gene is shown relative to the scrambled miRNA inhibitor control (set as 1.0). The mRNA expression levels of UGT2B7, UGT2B4, and UGT2B10 were quantified using qRT-PCR in the presence of 100 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p inhibitor in HuH-7 (E) and Hep3B (F) cells. Each gene was quantified against the endogenous internal control gene RPLP0, and each gene is shown relative to the scrambled miRNA inhibitor control (set as 1.0). Columns represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To examine the endogenous effects of miR-216b-5p on UGT2B mRNA levels, 100 nM miR-216b-5p inhibitor was used to transiently inhibit miR-216b-5p function in both cell lines. Endogenous levels of miR-216b-5p were significantly repressed by 100-fold (P = 0.026) and 25-fold (P = 0.0045) in HuH-7 and Hep3B cells, respectively (Fig. 5, C and D). The mRNA levels of each UGT2B isoform were quantified using qRT-PCR analysis to measure the effect on mRNA expression when endogenous miR-216b-5p is inhibited. UGT2B7 mRNA levels were significantly increased in both HuH-7 (P = 0.021) and Hep3B (P = 0.0068) cells in the presence of the miR-216b-5p inhibitor (Fig. 5, E and F). A significant (P < 0.001) increase in mRNA levels was also observed for UGT2B4 when miR-216b-5p was inhibited in HuH-7 cells (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, UGT2B10 mRNA levels were significantly repressed in both cell lines when miR-216b-5p was inhibited (Fig. 5, E and F).

Effect of miR-216b-5p on UGT2B Protein Levels and Activity in Hepatic Cell Lines.

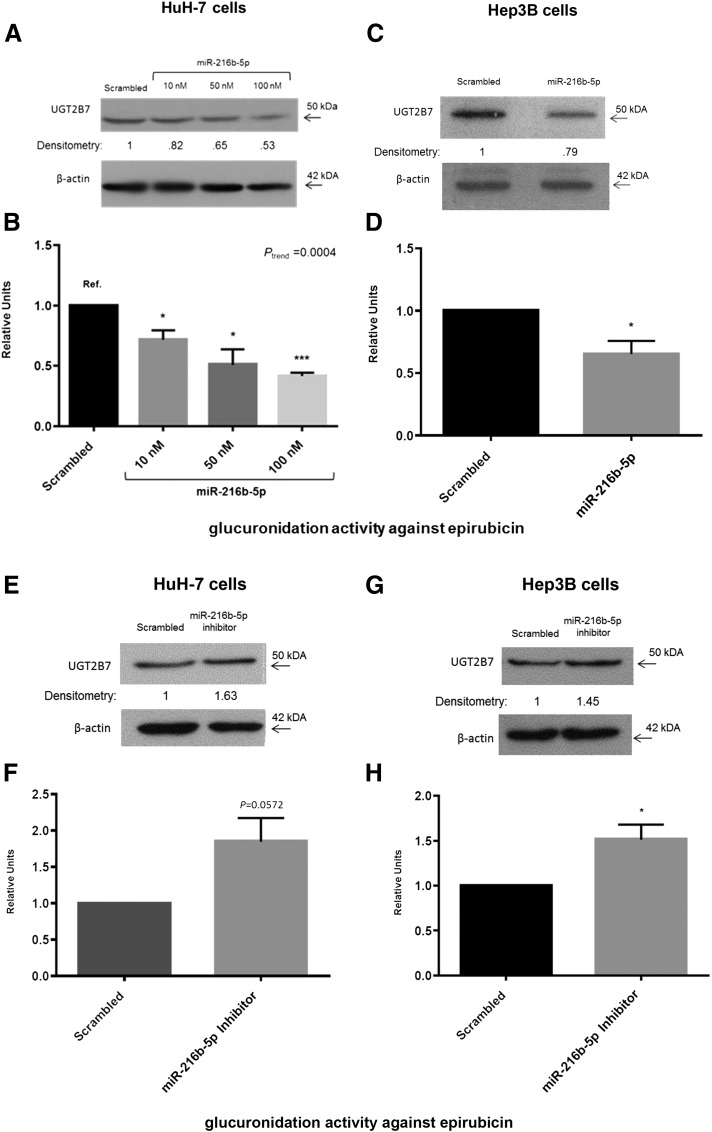

To investigate the effect of miR-216b-5p overexpression on UGT2B enzymatic activity, HuH-7 and Hep3B cells were transiently transfected with miR-216b-5p mimic, and UGT2B protein expression and/or enzymatic activities were assessed. Although useful specific antibodies are not available for most UGT2B enzymes (including UGT2B4 and UGT2B10), a sensitive and specific antibody is available from BD Biosciences for the detection of UGT2B7. Using this antibody in Western blot analysis, a 47% decrease in UGT2B7 protein after transfection with 100 nM miR-216b-5p was observed (Fig. 6A). This corresponded to significant decreases in UGT2B7 glucuronidation activity (Fig. 6B). Using the UGT2B7-specific substrate epirubicin (Innocenti et al., 2001; Zaya et al., 2006), a significant (Ptrend < 0.001) dose-dependent decrease in epirubicin glucuronidation was observed in assays with 500 µM epirubicin. As compared with the scrambled miRNA control, there was a significant (P = 0.023) 29% reduction in glucuronide formation in HuH-7 cells transfected with 10 nM miR-216b-5p, a significant (P = 0.018) 49% reduction at 50 nM miR-216b-5p, and a significant (P < 0.0001) 58% reduction at 100 nM miR-216b-5p. A similar pattern was observed in Hep3B cells, with a 21% decrease in UGT2B7 protein expression (Fig. 6C) and a significant (P = 0.011) 35% decrease in epirubicin glucuronidation after transient transfection with 50 nM miR-216b-5p (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

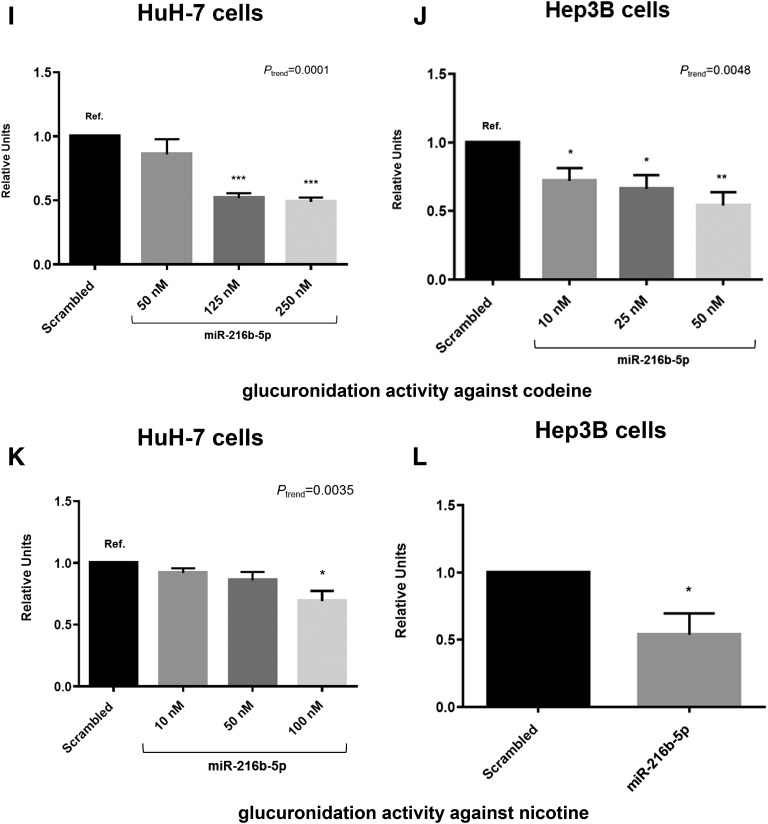

UGT2B7 protein expression and UGT2B glucuronidation activity in the presence of miR-216b-5p mimic or inhibitor. (A) Representative blot of HuH-7 UGT2B7 protein expression after transfection of 10, 50, or 100 nM miR-216b-5p mimic or 100 nM scrambled miRNA mimic control. UGT2B7 protein bands were normalized to β-actin band intensities and compared with normalized UGT2B7 protein bands from cells transfected with scrambled miRNA control. (B) UGT2B7 glucuronidation activity against epirubicin in HuH-7 cells transfected with 10, 50, or 100 nM miR-216b-5p mimic or 100 nM scrambled miRNA control. (C) Representative blot of Hep3B UGT2B7 protein expression in the presence of 50 nM scrambled control or miR-216b-5p mimic. (D) UGT2B7 glucuronidation activity against epirubicin in Hep3B cells transfected with 50 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p mimic. (E) Representative blot of UGT2B7 protein expression in HuH-7 cells transfected with 100 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p inhibitor. (F) UGT2B7 glucuronidation activity against epirubicin in HuH-7 cells transfected with 100 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p inhibitor. (G) Representative blot of UGT2B7 protein expression in Hep3B cells transfected with 100 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p inhibitor. (H) UGT2B7 glucuronidation activity against epirubicin in Hep3B cells transfected with 100 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p inhibitor. (I) UGT2B4 glucuronidation activity against codeine in HuH-7 transfected with 250 nM scrambled miRNA mimic or 50, 125, or 250 nM miR-216b-5p mimic. (J) UGT2B4 glucuronidation activity against codeine in Hep3B cells transfected with 50 nM scrambled miRNA mimic or 10, 25, or 50 nM miR-216 mimic. (K) UGT2B10 glucuronidation activity against nicotine in HuH-7 cells transfected with 100 nM scrambled miRNA mimic or 10, 50, or 100 nM miR-216b-5p mimic. (L) UGT2B10 glucuronidation activity against nicotine in Hep3B cells transfected with 50 nM scrambled or miR-216b-5p mimic. Columns represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To examine the impact of endogenous miR-216b-5p expression on the regulation of UGT2B7 in HuH-7 and Hep3B cells, transient transfection with 100 nM miR-216b-5p inhibitor was performed to significantly inhibit miR-216b-5p endogenous expression in the two cell lines. An increase of >60% in the levels of UGTB7 protein was observed in miR-216b-5p–inhibited HuH-7 cells (Fig. 6E), and this corresponded to a near-significant increase (∼85%; P = 0.0572) in epirubicin glucuronidation activity (Fig. 6F). Similar results were seen in Hep3B cells, where UGT2B7 protein expression increased by 45% (Fig. 6G), and epirubicin glucuronidation levels were significantly (P = 0.012) increased by 50% (Fig. 6H).

The effect of miR-216b-5p on UGT2B4 enzyme activity was measured via glucuronidation activity against codeine. Whereas UGTs 2B4 and 2B7 are the two UGTs that exhibit significant and roughly equivalent levels of activity against codeine (Court et al., 2003), UGT2B4 is expressed at approximately 5- and 14-times greater levels than UGT2B7 in HuH-7 and Hep3B cells, respectively (see Fig. 4), suggesting that codeine-glucuronide formation is likely driven primarily by UGT2B4 in both cell lines. Possibly due to high expression of UGT2B4 in HuH-7 cells (see Fig. 4), higher concentrations (50–250 nM) of miR-216b-5p were required for transfection to observe an effect on UGT2B4 expression. In HuH-7 cells, codeine-glucuronide formation was significantly decreased by 52% (P < 0.001) and 54% (P < 0.001) at 125 and 250 nM, respectively, with a linear trend toward decreased codeine-glucuronide formation observed with increasing concentrations of miR-216b-5p (Ptrend < 0.001; Fig. 6I). In Hep3B cells, the decrease in codeine-glucuronide formation was 28% (P = 0.040), 34% (P = 0.027), and 46% (P = 0.0090) for 10, 25, and 50 nM, respectively, with a significant trend toward decreased codeine glucuronidation with increased miR-216b-5p (Ptrend = 0.0048; Fig. 6J).

Nicotine was shown to be a selective substrate for UGT2B10 in previous studies (Chen et al., 2007, 2008). Activity assays utilizing nicotine were used to evaluate the effect of increasing concentrations of miR-216b-5p on UGT2B10 activity. A significant trend (Ptrend = 0.0035) toward decreasing nicotine-glucuronide formation was observed in HuH-7 cells with increasing concentrations of miR-216b-5p, with a reduction in nicotine-glucuronide formation of 31% (P = 0.017) at 100 nM miR-216b-5p (Fig. 6K). Similarly, Hep3B nicotine glucuronidation activity was significantly (P = 0.043) decreased by 47% at 50 nM miR-216b-5p (Fig. 6L). These results indicated that miR-216b-5p’s interaction with UGT2B 3′ UTRs affects enzymatic activity.

Discussion

This is the first study to identify an miRNA regulator of UGTs 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10. In silico miRNA prediction programs were used to identify miR-216b-5p binding motifs within the 3′ UTRs of several UGT2B enzymes, including UGT2B4, UGT2B7, UGT2B10, and UGT2B28. Results from this in silico analysis were validated by in vitro overexpression studies of luciferase vectors containing wild-type or mutated UGT2B 3′ UTR MRE sequences, suggesting that in silico prediction modeling is a useful tool to predict miRNA-gene interactions within the UGT gene family. Although UGT2B28 was not examined experimentally in the present study, overexpression of 10 nM miR-216b-5p resulted in a significant decrease in luciferase activity using vectors containing the UGT2B28 3′ UTR in previous studies (Margaillan et al., 2016).

The positions of the miR-216b-5p MREs for each UGT2B mRNA are all located between 65 and 150 nt downstream of their respective translation stop codons, and this is likely related to sequence similarities within the UGT2B gene locus. It has been hypothesized that gene-duplication events created the UGT2B gene family, with UGT2B4 being an ancestral gene (Guillemette et al., 2010). Therefore, it is likely that miR-216b-5p binding sites were duplicated and conserved during this process.

The seed sequence for miR-216b-5p shares seven of eight nucleotides with the seed sequence for the closely related miR-216a-5p. There is no predicted binding site for miR-216a-5p for UGT2B4. Both UGT2B7 and UGT2B10 have a predicted binding site for miR-216a-5p that overlaps the stop codon, with UGT2B10 having a second predicted miR-216a-5p binding site 504 nt 3′ of the UGT2B10 stop codon. While it is possible that miR-216b-5p binds to miR-216a-5p sites, the luciferase data presented in this study indicate that binding to an alternative site is likely minimal. In unpublished studies (D. F. Dluzen and P. Lazarus), miR-216a-5p mimic reduced luciferase activity for both UGT2B7 and UGT2B10 but not UGT2B4, and no significant effect on UGT2B expression or protein activity was observed in HuH-7 or Hep3B cells, suggesting that miR-216a-5p is not a major regulator of UGT2B expression/activity.

miR-216b-5p expression levels were quantified in several UGT-expressing tissues, with miR-216b-5p exhibiting moderate expression in liver and highest expression in pancreas. These results are consistent with data from the only other previous study investigating tissue expression of miR-216b-5p where high hepatic and pancreatic expression of miR-216b-5p was also observed (Endo et al., 2013). The fact that miR-216b-5p is expressed hepatically is consistent with a potential role in the regulation of hepatic UGT2B expression and in drug metabolism.

Although miR-216b-5p has not been previously linked to drug metabolism, miR-216b-5p serves as a tumor-suppressor in liver cancer cells by regulating expression of insulin-like 2 mRNA-binding protein 2 (IGF2BP) and influencing downstream protein kinase B/mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (AKT/mTOR) and Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways (Liu et al., 2015). miR-216b levels were shown to be lower in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, and higher expression is associated with increased 5-year survival (Liu et al., 2015). miR-216b-5p targets FGFR1 in pancreatic cancer cells, and decreased expression is a marker for poor prognosis in pancreatic patients (Egeli et al., 2016).

In vitro overexpression of miR-216b-5p in the HuH-7 and Hep3B hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines resulted in decreased mRNA expression of the three hepatically expressed UGT2B enzymes (UGTs 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10) predicted by in silico models to bind miR-216b-5p. Interestingly, similar decreases in mRNA expression were not observed for several other hepatic UGT2B enzymes after overexpression of miR-216b-5p, including UGTs 2B11, 2B15, and 2B17. This is consistent with the fact that none of these latter UGTs were predicted to bind miR-216b-5p in silico. For UGTs 2B7 and 2B4, these results were corroborated by in vitro studies in which endogenous miR-216b-5p was depleted using an miR-216b-5p inhibitor, resulting in the upregulation of mRNA levels for both UGTs 2B7 and 2B4 in at least one or both of the hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines tested. The decrease in UGT2B10 expression observed in the presence of the miR-216b-5p inhibitor may be due to the presence of another miRNA that binds to and competes for the same miR-216b-5p miRNA binding site. In silico analysis of UGT2B10 by both miRanda and TargetScan reveals that miR-379 is predicted to bind to UGT2B10 within eight nucleotides of the miR-216b MRE but is not predicted to bind the 3′ UTRs of both UGT2B4 and UGT2B7. Further studies are required to address this possibility.

The inhibitory pattern observed for miR-216b-5p on UGT2B mRNA expression was also observed for UGT2B7 protein. Epirubicin glucuronidation is primarily mediated by UGT2B7 (Innocenti et al., 2001; Zaya et al., 2006), and miR-216b-5p overexpression significantly reduced epirubicin glucuronide formation in both HuH-7 and Hep3B cells. In addition, depletion of endogenous miR-216b-5p using an miR-216b-5p–specific inhibitor increased UGT2B7 protein levels and activity in both cell lines. The same pattern of reduced glucuronidation activity after overexpression of miR-216 mimic was observed against codeine, a substrate of UGT2B4 (Court et al., 2003), as well as nicotine, a substrate of UGT2B10 (Chen et al., 2007, 2008). Together with the fact that miR-216b-5p overexpression also decreased UGTs 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10 mRNA expression levels, these data indicate that endogenous miR-216b-5p may play a role in UGT2B functionality and suggest a potential regulatory mechanism in normal human liver and perhaps other tissues where UGTs 2B7, 2B4, and 2B10 are coexpressed with miR-216b-5p.

Interestingly, a larger increase in UGT2B7 protein activity was observed in HuH-7 cells compared with Hep3B cells when endogenous miR-216b-5p was inhibited. This may reflect the fact that endogenous miR-216b-5p expression levels are >30-fold higher in HuH-7 cells compared with Hep3B cells, and relief from miR-216b-5p regulation would thus impact UGT2B7 expression to a greater extent in HuH-7 cells. The normal human liver tissue samples used in this study only had approximately 2-fold higher endogenous miR-216b-5p expression compared with Hep3B cells. An approximately 25% increase in UGT2B7 glucuronidation was observed in Hep3B cells with inhibited miR-216b-5p, and this may better reflect the endogenous repression of UGT2B7 in normal liver.

Interestingly, there is a known SNP within the miR-216b-5p MRE seed sequence of the UGT2B10 3′ UTR (rs139538767). This polymorphism functions in a manner similar to that observed for the UGT2B10 3′ UTR seed deletion control, resulting in an elimination of the negative regulation of UGT2B10 3′ UTR luciferase expression after miR-216b-5p overexpression. These data suggest that this SNP may cause altered regulation of the polymorphic UGT2B10 allele. The minor allele frequency of this SNP is low, with a prevalence of ∼1% in the Caucasian population, but the present study provides the first evidence of a UGT2B 3′ UTR SNP with a direct functional role in aberrant miRNA regulation.

In summary, we provide evidence of a functional miR-216b-5p binding motif within the 3′ UTR of several UGT2B isoforms. UGT2B7 and UGT2B4 mRNA and protein expression, as well as overall enzymatic activity, were significantly repressed in the presence of overexpressed miR-216b-5p and were induced after the addition of miR-216b-5p inhibitor, and this may have functional consequences on UGT2B7 and UGT2B4 enzymatic activity in vivo. UGT2B10 mRNA levels and glucuronidation activity were also reduced in the presence of the miR-216b-5p mimic. In addition, a functional SNP was identified in the UGT2B10 3′ UTR which may modify UGT2B10 regulation through an miR-216b-5p–mediated pathway. Together, these data suggest that miR-216b-5p may exhibit a regulatory function on the overall glucuronidation activity of several UGT2B enzymes, and that changes in miR-216b-5p expression or the presence of SNPs in miR-216b-5p binding motifs in UGT2B 3′ UTRs may contribute to interindividual variability of UGT2B expression and affect overall phase II metabolism in humans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Washington State University Mass Spectrometry Core Facility for their support and help with analysis of glucuronide detection. The authors acknowledge the assistance and help of Amity Platt for her advice and help in refining molecular techniques.

Abbreviations

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney cell line 293

- miRNA

microRNA

- MRE

miRNA recognition element

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- nt

nucleotide

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SDM

site-directed mutagenesis

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- UGT

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase

- UPLC

ultra-pressure liquid chromatography

- UTR

untranslated region

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Dluzen, Sutliff, Chen, Watson, Ishmael, Lazarus.

Conducted experiments: Dluzen, Sutliff.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Dluzen, Sutliff, Chen, Watson, Ishmael, Lazarus.

Performed data analysis: Dluzen, Sutliff, Chen, Watson, Ishmael, Lazarus.

Wrote or contributed to writing of the manuscript: Dluzen, Sutliff, Chen, Watson, Ishmael, Lazarus.

Footnotes

This work was supported by funds from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [Grant R01-DE13158 to P.L.] and the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences [Grant R01-ES025460 to P.L.], and also in part by a student fellowship provided by AstraZeneca (to D.F.D.).

References

- Baek D, Villén J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. (2008) The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455:64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. (2009) MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136:215–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. (2008) The microRNA.org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res 36:D149–D153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. (2005) Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol 3:e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen P, Voinnet O. (2009) Revisiting the principles of microRNA target recognition and mode of action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. (2009) Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136:642–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Blevins-Primeau AS, Dellinger RW, Muscat JE, Lazarus P. (2007) Glucuronidation of nicotine and cotinine by UGT2B10: loss of function by the UGT2B10 Codon 67 (Asp>Tyr) polymorphism. Cancer Res 67:9024–9029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Dellinger RW, Sun D, Spratt TE, Lazarus P. (2008) Glucuronidation of tobacco-specific nitrosamines by UGT2B10. Drug Metab Dispos 36:824–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouinard S, Barbier O, Bélanger A. (2007) UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B15 (UGT2B15) and UGT2B17 enzymes are major determinants of the androgen response in prostate cancer LNCaP cells. J Biol Chem 282:33466–33474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court MH, Krishnaswamy S, Hao Q, Duan SX, Patten CJ, Von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. (2003) Evaluation of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine, morphine, and codeine as probe substrates for UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 (UGT2B7) in human liver microsomes: specificity and influence of the UGT2B7*2 polymorphism. Drug Metab Dispos 31:1125–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger RW, Chen G, Blevins-Primeau AS, Krzeminski J, Amin S, Lazarus P. (2007) Glucuronidation of PhIP and N-OH-PhIP by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A10. Carcinogenesis 28:2412–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dluzen DF, Sun D, Salzberg AC, Jones N, Bushey RT, Robertson GP, Lazarus P. (2014) Regulation of UGT1A1 expression and activity by miR-491-3p. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 348:465–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeli U, Tezcan G, Cecener G, Tunca B, Demirdogen Sevinc E, Kaya E, Ak S, Dundar HZ, Sarkut P, Ugras N, et al. (2016) miR-216b targets FGFR1 and confers sensitivity to radiotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients without EGFR or KRAS mutation. Pancreas [published ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo K, Weng H, Kito N, Fukushima Y, Iwai N. (2013) MiR-216a and miR-216b as markers for acute phased pancreatic injury. Biomed Res 34:179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia DM, Baek D, Shin C, Bell GW, Grimson A, Bartel DP. (2011) Weak seed-pairing stability and high target-site abundance decrease the proficiency of lsy-6 and other microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18:1139–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemette C, Lévesque E, Harvey M, Bellemare J, Menard V. (2010) UGT genomic diversity: beyond gene duplication. Drug Metab Rev 42:24–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. (2010) Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 466:835–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Dial S, Shi L, Branham W, Liu J, Fang JL, Green B, Deng H, Kaput J, Ning B. (2011) Similarities and differences in the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes between human hepatic cell lines and primary human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos 39:528–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti F, Iyer L, Ramírez J, Green MD, Ratain MJ. (2001) Epirubicin glucuronidation is catalyzed by human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7. Drug Metab Dispos 29:686–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itäaho K, Mackenzie PI, Ikushiro S, Miners JO, Finel M. (2008) The configuration of the 17-hydroxy group variably influences the glucuronidation of beta-estradiol and epiestradiol by human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab Dispos 36:2307–2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izukawa T, Nakajima M, Fujiwara R, Yamanaka H, Fukami T, Takamiya M, Aoki Y, Ikushiro S, Sakaki T, Yokoi T. (2009) Quantitative analysis of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A and UGT2B expression levels in human livers. Drug Metab Dispos 37:1759–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NR, Lazarus P. (2014) UGT2B gene expression analysis in multiple tobacco carcinogen-targeted tissues. Drug Metab Dispos 42:529–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. (2005) Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu FY, Zhou SJ, Deng YL, Zhang ZY, Zhang EL, Wu ZB, Huang ZY, Chen XP. (2015) MiR-216b is involved in pathogenesis and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma through HBx-miR-216b-IGF2BP2 signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis 6:e1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie PI, Bock KW, Burchell B, Guillemette C, Ikushiro S, Iyanagi T, Miners JO, Owens IS, Nebert DW. (2005) Nomenclature update for the mammalian UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene superfamily. Pharmacogenet Genomics 15:677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie PI, Hu DG, Gardner-Stephen DA. (2010) The regulation of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase genes by tissue-specific and ligand-activated transcription factors. Drug Metab Rev 42:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margaillan G, Lévesque É, Guillemette C. (2016) Epigenetic regulation of steroid inactivating UDP-glucuronosyltransferases by microRNAs in prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 155 (Pt A):85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherji S, Ebert MS, Zheng GX, Tsang JS, Sharp PA, van Oudenaarden A. (2011) MicroRNAs can generate thresholds in target gene expression. Nat Genet 43:854–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Nakajima M, Yamanaka H, Fujiwara R, Yokoi T. (2008) Expression of UGT1A and UGT2B mRNA in human normal tissues and various cell lines. Drug Metab Dispos 36:1461–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S, Nakajin S. (2009) Determination of mRNA expression of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and application for localization in various human tissues by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Drug Metab Dispos 37:32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S, Nakajin S. (2011) Quantitative analysis of UGT2B28 mRNA expression by real-time RT-PCR and application to human tissue distribution study. Drug Metab Lett 5:202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki S, Schaefer O, Kawakami H, Inoue T, Liehner S, Saito A, Ishiguro N, Kishimoto W, Ludwig-Schwellinger E, Ebner T, et al. (2012) Simultaneous absolute protein quantification of transporters, cytochromes P450, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases as a novel approach for the characterization of individual human liver: comparison with mRNA levels and activities. Drug Metab Dispos 40:83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer BR, Yeager M, Staats B, Welch R, Crenshaw A, Kiley M, Eckert A, Beerman M, Miller E, Bergen A, et al. (2004) SNP500Cancer: a public resource for sequence validation and assay development for genetic variation in candidate genes. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D528–D532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan YZ, Gao W, Yu AM. (2009) MicroRNAs regulate CYP3A4 expression via direct and indirect targeting. Drug Metab Dispos 37:2112–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedy M, Wang JY, Miller AP, Buckler A, Hall J, Guida M. (2000) Genomic organization of the UGT2b gene cluster on human chromosome 4q13. Pharmacogenetics 10:251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Nagata M, Kawamura A, Miyashita A, Usui T. (2012) Protein quantification of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases 1A1 and 2B7 in human liver microsomes by LC-MS/MS and correlation with glucuronidation activities. Xenobiotica 42:823–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stingl JC, Bartels H, Viviani R, Lehmann ML, Brockmoller J. (2014) Relevance of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase polymorphisms for drug dosing: a quantitative systematic review. Pharmacol Ther 141:92–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Jones NR, Manni A, Lazarus P. (2013) Characterization of raloxifene glucuronidation: potential role of UGT1A8 genotype on raloxifene metabolism in vivo. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 6:719–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Sharma AK, Dellinger RW, Blevins-Primeau AS, Balliet RM, Chen G, Boyiri T, Amin S, Lazarus P. (2007) Glucuronidation of active tamoxifen metabolites by the human UDP glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab Dispos 35:2006–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijayakumara DD, Hu DG, Meech R, McKinnon RA, Mackenzie PI. (2015) Regulation of Human UGT2B15 and UGT2B17 by miR-376c in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 354:417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaya MJ, Hines RN, Stevens JC. (2006) Epirubicin glucuronidation and UGT2B7 developmental expression. Drug Metab Dispos 34:2097–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]