Abstract

Background

Appropriate outcome selection is essential if research is to guide decision‐making and inform policy. Systematic reviews of the clinical, cosmetic and patient‐reported outcomes of reconstructive breast surgery, however, have demonstrated marked heterogeneity, and results from individual studies cannot be compared or combined. Use of a core outcome set may improve the situation. The BRAVO study developed a core outcome set for reconstructive breast surgery.

Methods

A long list of outcomes identified from systematic reviews and stakeholder interviews was used to inform a questionnaire survey. Key stakeholders defined as individuals involved in decision‐making for reconstructive breast surgery, including patients, breast and plastic surgeons, specialist nurses and psychologists, were sampled purposively and sent the questionnaire (round 1). This asked them to rate the importance of each outcome on a 9‐point Likert scale from 1 (not important) to 9 (extremely important). The proportion of respondents rating each item as very important (score 7–9) was calculated. This was fed back to participants in a second questionnaire (round 2). Respondents were asked to reprioritize outcomes based on the feedback received. Items considered very important after round 2 were discussed at consensus meetings, where the core outcome set was agreed.

Results

A total of 148 items were combined into 34 domains within six categories. Some 303 participants (51·4 per cent) (215 (49·5 per cent) of 434 patients; 88 (56·4 per cent) of 156 professionals) completed and returned the round 1 questionnaire, and 259 (85·5 per cent) reprioritized outcomes in round 2. Fifteen items were excluded based on questionnaire scores and 19 were carried forward to the consensus meetings, where a core outcome set containing 11 key outcomes was agreed.

Conclusion

The BRAVO study has used robust consensus methodology to develop a core outcome set for reconstructive breast surgery. Widespread adoption by the reconstructive community will improve the quality of outcome assessment in effectiveness studies. Future work will evaluate how these key outcomes should best be measured.

Short abstract

A compass for future studies

Introduction

Breast cancer affects almost 50 000 women in the UK each year1, up to 40 per cent of whom will require a mastectomy2. For some, the loss of a breast can be devastating and reconstructive breast surgery (RBS) is offered to improve outcomes3.

Decision‐making in RBS, however, can be difficult. There are several procedures available, ranging in complexity from expander/implant‐based reconstructions to more challenging autologous procedures4, 5. Factors such as body habitus, co‐morbidities and the need for postoperative radiotherapy6 may influence the choice of reconstructive method. However, the majority of patients are technically suitable for a range of procedures. Patients and surgeons therefore face challenging decisions regarding the optimal type and timing of surgery.

The provision of high‐quality data, ideally from well designed, multicentre randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and prospective studies is central to this process7, 8. Systematic reviews summarizing the clinical9, cosmetic10 and patient‐reported11, 12 outcomes of RBS, however, have demonstrated a paucity of well designed studies, and an inconsistent approach to outcome assessment and reporting in each of these areas. Cross‐study comparison and meta‐analysis is therefore difficult and the need for improvement in outcome reporting in RBS is increasingly being recognized9, 10, 13.

The standardization of endpoints (core outcome sets) for use in effectiveness studies is one way in which inappropriate and non‐uniform outcome reporting may be addressed14, 15. A core outcome set is defined as an agreed set of outcomes to be reported as a minimum in all studies of a particular condition15, 16. Uptake of a core outcome set has the potential to reduce reporting bias, create homogeneity in outcome reporting and improve meta‐analysis17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22. It is hypothesized that development of a core outcome set may result in similar improvements in the value of research in RBS23, 24.

The aim of the BRAVO (Breast Reconstruction And Valid Outcomes) study was to use a robust consensus process to develop a core outcome set for effectiveness studies in RBS.

Methods

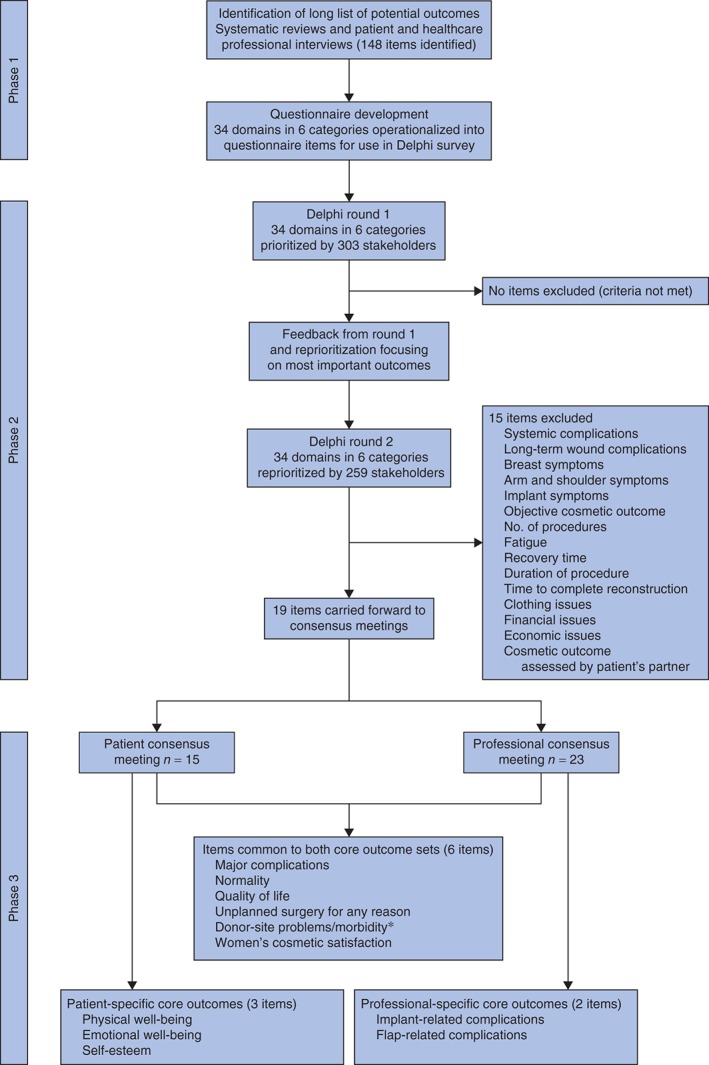

Development of the core outcome set involved three phases: phase 1, development of a questionnaire with a list of potential outcomes; phase 2, sequential surveys with key stakeholders using Delphi methods to prioritize outcomes; and phase 3, consensus meetings with patients and professionals to agree the core outcome set (Table 1, Fig. 1). Full ethical approval was obtained for the study (REC‐11/SW/0305).

Table 1.

Summary of methods used to develop a core outcome set

| Phase 1 | Identification of all outcomes that may be measured following reconstructive breast surgery |

| Systematic literature searches to identify clinical outcomes, patient‐reported and cosmetic outcomes | |

| Qualitative interviews with patients and healthcare professionals regarding which outcomes they feel should be measured following reconstructive breast surgery | |

| This produces a list of all potential outcomes | |

| The list is grouped into outcome domains to avoid repetition | |

| The domains inform questionnaire items to use in phase 2 | |

| Phase 2 | Prioritization of outcomes by key stakeholders – Delphi survey |

| Stakeholders are surveyed and asked to prioritize each outcome | |

| Results of the survey are fed back to stakeholders in a second survey (Delphi methods) and they are asked to reprioritize each outcome | |

| Data are analysed by the research group using predefined criteria to reduce the list of information | |

| This produces two outcome lists (from patients and healthcare professionals) ready for phase 3 | |

| Phase 3 | Consensus meetings are held separately with key stakeholder groups |

| The items are presented to each group and items are rated as, ‘in’, ‘out’ or ‘unsure’ during anonymized voting | |

| Items rated as ‘unsure’ are discussed and more voting is undertaken | |

| The process produces two sets (1 selected by patients, 1 by professionals). These are compared and combined into one outcome set |

Figure 1.

Summary of the development of a core outcome set for reconstructive breast surgery. *Donor‐site symptoms and donor‐site complications were merged into one item

Phase 1: questionnaire development

A long list of outcomes was generated from systematic reviews of the clinical9, cosmetic10 and patient‐reported12 outcomes of breast reconstruction, and semistructured interviews with patients and professionals were undertaken as part of the BRAVE (Breast Reconstruction And Valid Evidence) study, which aimed to determine the feasibility of clinical trials in breast reconstruction25, 26, 27, 28, 29. The list was constructed by two independent researchers extracting verbatim each of the outcomes reported in papers included in the systematic reviews. They scrutinized the transcripts of 62 semistructured interviews with patients (implant‐based reconstruction, 11 patients; latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction, 10; abdominal flap reconstruction, 11) and professionals (oncoplastic breast surgeons, 11; plastic surgeons, 11; clinical nurse specialists, 11; psychologists, 2) conducted within the BRAVE study during which outcome selection for research studies was discussed. Duplicate items were removed and the outcomes categorized into domains by two independent researchers using the qualitative technique of content analysis30, and dual extraction and categorization of outcomes with senior discussion if discrepancies occurred31. A domain was defined as a broad class of outcome; for example, the domain wound‐related problems included infection, wound dehiscence, skin necrosis and delayed wound healing. Domains were further categorized into overarching outcome themes or ‘categories’ using the same methodology31; for example, systemic complications and wound‐related problems were classified as early complications and the identified domains were operationalized into a questionnaire item, which involved asking respondents how important it was to measure each item in research and audit studies in RBS. Each item was structured with the medical terminology in bold italics followed by a lay description, as in the example: ‘How important is it to assess implant‐related complications – implant‐related problems such as infection that would require the implant to be removed?’. This allowed the questionnaire to be read and understood by all stakeholders. Respondents were asked to score the importance of evaluating each item in effectiveness studies in RBS on a 9‐point Likert scale from 1 (not important) to 9 (extremely important). The scoring system was selected after discussion with the study statistician and experts in core outcome set development to facilitate maximum discrimination between questionnaire items based on previous experience in this area, and has been used widely in this field14, 32. The questionnaire was piloted with patients and professionals to check face validity, understanding and acceptability.

Phase 2: Delphi consensus methods

Delphi survey methods, with anonymized feedback of results, involving key stakeholders were used to develop the core outcome set33.

Stakeholder selection

Key stakeholders were defined as individuals who may be involved in decision‐making for RBS and would have an in‐depth understanding of which outcomes should be measured in research and audit studies in this area. These were identified by the BRAVO Steering Group as patients, breast and plastic surgeons, clinical nurse specialists and psychologists. The steering group elected a priori to recruit patients and professionals in a 2 : 1 ratio such that patients' views were represented preferentially when the groups were combined because RBS is a patient‐selected optional intervention.

Patients were purposively sampled from three centres (Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow). All women who had undergone RBS using expander/implants, latissimus dorsi or abdominal flaps as either immediate or delayed procedures, or who had undergone therapeutic mammoplasty, defined as reduction pattern wide local excision and contralateral symmetrization, within 5 years of the start of the study were eligible to participate. Maximum variation sampling34 with a sampling matrix was used to ensure adequate inclusion of all identified groups with regard to procedure type (implant, latissimus dorsi and abdominal flaps, therapeutic mammoplasty), timing of surgery (immediate, delayed), age at time of surgery (less than 45 years, 45–65 years, over 65 years), time since surgery (less than 2 years, 2–4 years, more than 4 years) and treatment centre, such that a complete breadth of perspectives was included. Attention was also paid to demographic factors such as educational background, employment and marital status to ensure that no group was excluded35.

Professionals were recruited purposively from breast and plastic surgical units across the UK. Maximum variation sampling was used with regard to type of centre (teaching hospital versus district general hospital), sex and duration of practice to ensure a comprehensive representation of views. A priori, the aim was to recruit 200 patients, 30 breast surgeons, 30 plastic surgeons, 30 clinical nurse specialists and ten psychologists. This was detailed in the full protocol written for this study, which is available from the author.

Delphi surveys

Potential patient participants from all three centres were approached by post. Responders consenting to participate were sent a questionnaire with a prepaid envelope. Non‐responders were sent a reminder 3 weeks later. Healthcare professionals (HCPs) at breast and plastic surgery centres in the UK were identified from previous research participation and recent publications. Each professional was contacted by post with a study invitation letter and questionnaire. Non‐responders were sent a reminder 3 weeks later. Batches of invitations were sent until the desired sample size was achieved or until the sample pool had been exhausted.

The first‐round questionnaires were analysed by calculating the proportions of participants rating each item as very important (score 7, 8 or 9). All respondents were sent a second‐round questionnaire containing summary round 1 scores for each item; all feedback was anonymous. First‐round non‐responders were considered to have declined study participation and were not contacted again. In round 2, participants were asked to reprioritize the outcomes based on feedback from round 1. Participants were also asked to identify the seven outcomes of most importance, those ‘core’ to measure in effectiveness studies in RBS.

Phase 3: consensus meetings

Separate consensus meetings for key stakeholders were held to prevent professionals dominating the meetings. The patients' meeting was held in Bristol in February 2014, and the professionals' meeting in Liverpool in July 2014. All patients and professionals who had completed the round 2 questionnaire were invited to attend the consensus meetings. Travel expenses were offered to encourage participation, but no additional financial incentives were provided. Attendees were selected purposively to ensure that all key stakeholder groups were represented, using similar maximum variation criteria to those described for phase 2.

Each meeting was led by an independent facilitator whose role was to lead and promote the discussion and mediate if necessary. The meetings included a summary of the work to date, discussion, and anonymous electronic voting using TurningPoint software (Turning Technologies, Youngstown, Ohio, USA) to determine consensus.

A list of the items retained after round 2 was sent to all participants in advance of the meeting to enable them to consider independently which items they felt should be included in the core outcome set. Each item was presented in the meeting and attendees were asked to vote anonymously on their importance on a scale of 1 (not important) to 9 (extremely important). Items were classified as definitely ‘in’, definitely ‘out’ or ‘unsure’ based on predetermined criteria. Items that were classified as unsure were discussed among the group. A further round of anonymized voting was conducted, whereby participants were asked to rate the item as in or out based on the discussion. Discussion and voting were undertaken iteratively until consensus was achieved. Members were then asked to ratify the final core outcome set. All items retained from both the patients' and HCPs' meetings were included in the final combined core set.

Sample size

There are currently no guidelines for the numbers of participants required to develop a core outcome set14. Given the complexity of RBS, however, it was considered that approximately 300 participants would be necessary to ensure that all the relevant stakeholder groups were sampled adequately. In addition, approximately 20 participants were approached for each consensus meeting to facilitate discussion while ensuring that all key stakeholder subgroups were represented.

Data analysis

Items were retained for round 2 if more than 50 per cent of respondents in either the patient or the professional group, or both groups combined, scored the item 7–9, and less than 15 per cent of either group or both combined scored the item as not important (score 1–3). The patient and professional groups were analysed separately initially and also together. The separate analysis ensured that outcomes important to individual stakeholder groups were not excluded from the analysis prematurely.

In round 2, participants received group feedback from round 1 in the form of the percentage of respondents rating each item as very important (score 7–9), in addition to their own score for that item from round 1. It was hypothesized that the type of feedback received would influence how items were prioritized in round 2. The feedback was therefore provided from either the participants' group alone (patients or professionals) or both groups separately (patients and professionals) via random allocation to allow this to be explored. Full details of the impact of different stakeholder feedback on responses in round 2 will be reported separately.

Round 2 responses were analysed with more stringent criteria. Items rated as very important (score 7–9) by at least 70 per cent of respondents in either the patient or professional group, or both groups combined, were retained and carried forward for discussion at the phase 3 consensus meetings. These cut‐offs were selected for pragmatic reasons as there is currently no consensus regarding cut‐off selection in Delphi studies14, 36.

Before the consensus meetings, criteria for consensus regarding item inclusion and exclusion were agreed. Items scored as extremely important (score 8 or 9) by more than 70 per cent of participants and not important (score 1–3) by less than 15 per cent were definitely included in the final core outcome set. Items considered as extremely important (8 or 9) by less than 30 per cent of participants were definitely excluded from the final set. Ratification was sought for the items definitely included or excluded following the initial vote, and items that were scored 8 or 9 by between 30 and 70 per cent of participants were discussed by the group in an attempt to reach consensus. A second round of anonymous interactive voting followed the discussion to determine whether these remaining items should be included or excluded from the final core outcome set based on the predetermined criteria. If uncertainty remained after the second vote, further discussion was facilitated to allow consensus to emerge. The consensus meetings concluded with all participants ratifying the core outcome set for RBS.

Results

Phase 1: questionnaire development

Review of all data sources identified 148 individual outcomes that were categorized using content analysis into 34 domains. These were further classified using the same methodology into six categories: short and long‐term complications, symptoms, psychosocial well‐being, practical issues and cosmesis. Each domain was operationalized to generate a questionnaire item (Table S1 and Appendix S1, supporting information).

Phase 2: Delphi consensus methods

A total of 434 patients from three high‐volume breast units were invited to participate in round 1. Of these, 281 (64·7 per cent) responded; 39 (9·0 per cent) declined. Of 242 (55·8 per cent) who consented to participate, 215 (88·8 per cent) completed and returned the questionnaire. Participants had a median age of 54 (range 29–76) years and had undergone the full range of reconstructive techniques (expander/implants 54, 25·1 per cent; latissimus dorsi flaps 59, 27·4 per cent; abdominal flaps 74, 34·4 per cent) and therapeutic mammoplasty (25, 11·6 per cent). These were carried out as immediate (110, 51·2 per cent) and delayed (80, 37·2 per cent) procedures at a median of 33 (range 4–97) months before the study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics of participants in the BRAVO study

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Consensus meetings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient participants | n = 215 | n = 190 | n = 15 |

| Centre | |||

| Bristol | 77 (35·8) | 68 (35·8) | 13 (87) |

| Liverpool | 74 (34·4) | 62 (32·6) | 2 (13) |

| Glasgow | 64 (29·8) | 60 (31·6) | 0 (0) |

| Age (years)* | |||

| < 45 | 21 (9·8) | 20 (10·5) | 2 (13) |

| 45–65 | 166 (77·2) | 146 (76·8) | 9 (60) |

| > 65 | 28 (13·0) | 24 (12·6) | 4 (27) |

| Median (range) | 54 (29–76) | 54 (29–76) | 55 (43–76) |

| Time since breast reconstruction (months)† | |||

| 0–24 | 72 (33·5) | 67 (35·3) | 4 (27) |

| 25–48 | 88 (40·9) | 75 (39·5) | 10 (67) |

| > 48 | 49 (22·8) | 42 (22·1) | 1 (7) |

| Unknown | 6 (2·8) | 6 (3·2) | 0 (0) |

| Median (range) | 33 (4–97) | 32 (4–97) | 35 (21–72) |

| Timing of surgery | |||

| Immediate reconstruction | 110 (51·2) | 100 (52·6) | 10 (67) |

| Delayed reconstruction | 80 (37·2) | 66 (34·7) | 4 (27) |

| Therapeutic mammoplasty | 25 (11·6) | 24 (12·6) | 1 (7) |

| Type of surgery | |||

| Implant‐based reconstruction | 54 (25·1) | 47 (24·7) | 4 (27) |

| Latissimus dorsi flap | 59 (27·4) | 52 (27·4) | 5 (33) |

| Abdominal flap | 74 (34·4) | 64 (33·7) | 5 (33) |

| Therapeutic mammoplasty | 25 (11·6) | 24 (12·6) | 1 (7) |

| Other‡ | 3 (1·4) | 3 (1·6) | 0 (0) |

| Education | |||

| Compulsory only | 65 (30·2) | 57 (30·0) | 3 (20) |

| Additional education | 139 (64·7) | 125 (65·8) | 11 (73) |

| Unknown | 11 (5·1) | 8 (4·2) | 1 (7) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 23 (10·7) | 18 (9·5) | 0 (0) |

| Married/living with partner | 153 (71·2) | 138 (72·6) | 13 (87) |

| Separated or divorced | 28 (13·0) | 26 (13·7) | 2 (13) |

| Widowed | 6 (2·8) | 4 (2·1) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 5 (2·3) | 4 (2·1) | 0 (0) |

| Employment status | |||

| Full‐ or part‐time employment | 130 (60·5) | 118 (62·1) | 11 (73) |

| Homemaker/housewife | 17 (7·9) | 11 (5·8) | 0 (0) |

| Retired | 45 (20·9) | 42 (22·1) | 3 (20) |

| Not working | 16 (7·4) | 13 (6·8) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 7 (3·3) | 6 (3·2) | 1 (7) |

| Professional participants | n = 88 | n = 69 | n = 23 |

| Sex | |||

| F | 46 (52) | 37 (53·6) | 14 (61) |

| M | 42 (48) | 32 (46·4) | 9 (39) |

| Profession | |||

| Consultant breast surgeon | 40 (45) | 35 (51) | 11 (48) |

| Consultant plastic surgeon | 21 (24) | 15 (22) | 5 (22) |

| Clinical nurse specialist | 20 (23) | 15 (22) | 6 (26) |

| Psychologist | 7 (8) | 4 (6) | 1 (4) |

| Time in post (years) | |||

| < 5 | 18 (20) | 12 (17) | 4 (17) |

| 5–10 | 30 (34) | 24 (35) | 9 (39) |

| 10–20 | 29 (33) | 25 (36) | 9 (39) |

| > 20 | 8 (9) | 6 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (4) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise.

At time of breast reconstruction.

At time of entering study.

Patients undergoing bilateral complex surgery who could not be classified into any one group.

Some 156 professionals were invited to participate, of whom 88 (56·4 per cent) completed and returned the questionnaire. Respondents included 40 (45 per cent) breast surgeons, 21 (24 per cent) plastic surgeons, 20 (23 per cent) specialist nurses and seven (8 per cent) psychologists. No professional actively declined to participate in the study (Table 2).

In round 1, none of the items met the exclusion criteria, so all 34 items were carried forward to round 2.

All round 1 respondents were invited to participate in round 2. Of these, 259 (190 patients, 88·4 per cent; 69 HCPs, 78 per cent) completed and returned the questionnaire. Demographics of patient and professional participants were similar between rounds 1 and 2 (Table 2). Round 1 scores were also similar between responders and non‐responders to round 2 scores for both stakeholder groups (data not shown).

Provision of feedback, advice regarding reprioritization of the most important items and application of the more stringent cut‐off criteria resulted in the exclusion of 15 items following round 2 (Fig. 1). Nineteen items were carried forward for discussion in the phase 3 consensus meetings. These included three items (bleeding, wound‐related complications and donor‐site symptoms) that were excluded by the professional group, but retained on the basis of patients' views. Scores for individual items in each round are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of item scores by round and outcome of consensus meetings by item

| % rating item ‘very important’ (score 7–9) | Consensus meetings(item voted ‘in’,‘out’ or ‘unsure’) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | ||||||||

| Patients (n = 215) | HCPs (n = 88) | All (n = 303) | Patients (n = 190) | HCPs (n = 69) | All (n = 259) | Item carried forward to meeting | Patient/HCP initial views | Patient/HCP final decision | |

| Problems that may occur in the first monthafter operation | |||||||||

| Systemic complications | 71·6 | 60 | 68·3 | 54·4 | 41 | 50·8 | No | – | – |

| Bleeding‐related complications | 83·3 | 59 | 76·2 | 74·9 | 43 | 66·3 | Yes* | Out/out | Out/out |

| Wound‐related complications | 85·1 | 71 | 80·9 | 79·6 | 68 | 76·4 | Yes* | Out/out | Out/out |

| Implant‐related complications | 87·7 | 92 | 89·0 | 83·8 | 90 | 85·4 | Yes | Out/in | Out/in |

| Flap‐related complications | 89·7 | 92 | 90·4 | 87·0 | 91 | 88·2 | Yes | Unsure/unsure | Out/in |

| Major complications | 92·1 | 90 | 91·4 | 93·6 | 90 | 92·6 | Yes | In/in | In/in |

| Problems that may occur in the months or yearsafter operation | |||||||||

| Long‐term wound‐related complications | 69·8 | 59 | 66·7 | 59·6 | 44 | 55·5 | No | – | – |

| Long‐term implant‐related complications | 83·0 | 82 | 82·7 | 77·7 | 77 | 77·3 | Yes | Unsure/unsure | Out/out |

| Long‐term flap‐related complications | 81·3 | 82 | 81·5 | 77·3 | 78 | 77·3 | Yes | Unsure/out | Out/out |

| Donor‐site complications | 82·2 | 83 | 82·4 | 76·7 | 78 | 77·0 | Yes | Unsure/unsure | In/in† |

| Unplanned surgery for any reason | 83·7 | 84 | 83·8 | 82·1 | 83 | 82·2 | Yes | Unsure/unsure | In/in |

| Symptoms that may occur after reconstructivebreast surgery | |||||||||

| Fatigue | 42·8 | 28 | 38·6 | 28·7 | 12 | 24·2 | No | – | – |

| Breast symptoms | 75·4 | 61 | 71·3 | 62·4 | 38 | 56·0 | No | – | – |

| Arm and shoulder symptoms | 73·5 | 78 | 74·9 | 67·7 | 57 | 65·0 | No | – | – |

| Implant‐related symptoms | 72·5 | 71 | 71·9 | 62·4 | 59 | 61·4 | No | – | – |

| Donor‐site symptoms | 79·3 | 73 | 77·4 | 72·5 | 65 | 70·4 | Yes* | Unsure/unsure | In/in† |

| Self‐esteem | 81·4 | 88 | 83·2 | 83·5 | 87 | 84·4 | Yes | Unsure/unsure | In/out |

| Body image | 84·7 | 90 | 86·1 | 85·6 | 91 | 87·1 | Yes | Unsure/unsure | Out/out |

| Normality | 86·1 | 86 | 86·1 | 89·4 | 90 | 89·5 | Yes | In/in | In/in |

| Emotional well‐being | 83·7 | 88 | 84·8 | 87·8 | 84 | 86·8 | Yes | Unsure/unsure | In/out |

| Sexual well‐being | 77·9 | 80 | 78·4 | 72·0 | 77 | 73·5 | Yes | Out/out | Out/out |

| Quality of life | 87·4 | 98 | 90·4 | 92·5 | 97 | 93·7 | Yes | In/in | In/in |

| Practical issues relating to reconstructivebreast surgery | |||||||||

| Physical well‐being | 80·5 | 86 | 82·1 | 83·6 | 88 | 84·9 | Yes | In/unsure | In/out |

| Recovery time | 73·5 | 62 | 70·2 | 66·0 | 43 | 59·8 | No | – | – |

| Duration of the procedure | 48·6 | 32 | 43·8 | 28·0 | 13 | 24·2 | No | – | – |

| Time to complete reconstruction | 66·7 | 49 | 61·5 | 47·3 | 24 | 41·2 | No | – | – |

| No. of procedures required | 75·9 | 61 | 71·7 | 69·0 | 48 | 63·4 | No | – | – |

| Clothing issues | 65·9 | 76 | 68·9 | 66·1 | 63 | 65·2 | No | – | – |

| Financial issues | 54·2 | 51 | 53·3 | 39·2 | 30 | 36·7 | No | – | – |

| Economic issues | 35·1 | 60 | 42·4 | 23·9 | 39 | 27·8 | No | – | – |

| Issues relating to the appearance of thereconstructed breast | |||||||||

| Patient‐reported cosmetic outcome | 91·6 | 93 | 92·1 | 94·7 | 97 | 95·3 | Yes | Unsure/unsure | Out/out |

| Objective cosmetic outcome | 76·2 | 72 | 74·8 | 68·6 | 63 | 67·2 | No | – | – |

| Cosmetic appearance assessed by patient's partner | 56·3 | 55 | 56·0 | 51·4 | 37 | 47·4 | No | – | – |

| Women's cosmetic satisfaction | 92·6 | 97 | 93·7 | 92·6 | 99 | 94·2 | Yes | In/in | In/in |

Carried forward to meeting on basis of patient scores.

Items combined in final core outcome set. HCP, healthcare professional.

Phase 3: consensus meetings

Of the 190 patients invited, 16 agreed to participate in the consensus meetings, and 15 who were representative of the patient stakeholder group attended the meetings (Table 2). Following the initial vote, five items (major complications, normality, quality of life, physical well‐being and women's cosmetic satisfaction) were definitely included in the core outcome set and four items were definitely excluded (Table 3). The remaining ten items were discussed and revoted on. This led to four further items (unplanned surgery, emotional well‐being, self‐esteem, and a composite of donor‐site complications and symptoms termed ‘problems’) being included in the final core outcome set and five items being excluded. All group members ratified the nine‐item core outcome set.

Of the 69 professionals invited, 25 agreed to participate in the consensus meeting and 23 who were representative of the professional stakeholder group attended the meetings (Table 2). Following the first vote, five items (major complications, implant‐related complications, quality of life, normality and women's cosmetic satisfaction) were definitely included and four items definitely excluded from the core outcome set based on the prespecified criteria (Table 3). The remaining ten items were discussed and revoted on. This led to three further items (flap‐related complications, unplanned surgery, and a composite of donor‐site symptoms and complications) being included in the core outcome set and the remaining six being excluded. All members of the professional group then ratified the eight‐item core outcome set.

Combining the patient and professional sets generated a final 11‐item core outcome set (Fig. 1, Table 4).

Table 4.

Final core outcome set for effectiveness studies in reconstructive breast surgery

| Item | Definition (from questionnaire) |

|---|---|

| Implant‐related complications* | Implant‐related problems in the first 30 days following surgery such as implant infection that would require the implant to be removed |

| Flap‐related complications* | Problems with the tissue flap used to reconstruct the breast that occur within the first 30 days following surgery including the need for another operation |

| Major complications† | Any problem that leads to another operation or readmission to hospital for treatment after being sent home in the first 30 days following the surgery |

| Unplanned surgery for any reason† | Any problem that occurs in the months or years after breast reconstruction that requires an operation that is not planned |

| Donor‐site problems/morbidity† | Any problems or symptoms arising from the area from which the tissue was taken to reconstruct the breast, including hernias, stiffness or numbness in the back, tummy or bottom |

| Self‐esteem‡ | Feeling self‐confident |

| Emotional well‐being‡ | Feelings of emotional and psychological health after surgery |

| Normality† | Feeling ‘back to normal self’ or ‘whole’ as a result of surgery |

| Quality of life† | Women's quality of life following surgery |

| Physical well‐being‡ | Physical activity such as how well women can perform work and leisure‐related tasks after surgery |

| Women's cosmetic satisfaction† | Women's overall satisfaction with the appearance of their reconstructed breast(s) after surgery |

Item core to professional group only;

item core to both patients and professionals;

item core to patient group only.

Discussion

The BRAVO study has used rigorous consensus methods involving key stakeholders to develop a core outcome set for use in effectiveness studies in RBS. Effectiveness studies are important to both patients and healthcare providers as they determine whether interventions work in the real world, and therefore inform both clinical decision‐making and health policy37. The core outcome set was developed following detailed scrutiny of the literature and qualitative work with patients and professionals to identify all potentially relevant outcomes, followed by an iterative consensus process using the views of over 250 key stakeholders representative of women undergoing RBS and professionals involved in the provision of specialist care. The final core outcome set therefore includes 11 items that are important to both patients and professionals, such as major complications requiring readmission or reoperation, unplanned surgery, quality of life, normality, self‐esteem, physical and emotional well‐being, and women's satisfaction with the cosmetic outcome of their surgery. It is now recommended that researchers use the core outcome set to inform the selection of measures used in future effectiveness studies in RBS.

The concept of standardizing outcomes to reduce the use of inappropriate outcomes, eliminate reporting bias and facilitate data synthesis is not new. The OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials) initiative championed the methodology by describing a ‘filter’ of ‘truth, discrimination and feasibility’ to determine outcome selection in rheumatoid arthritis over 20 years ago38, 39, but it is only recently that the potential for core outcome sets to improve the value of research has been realized in a broader context21, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44. To this end, the UK Medical Research Council‐funded COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) Initiative (www.comet-initiative.org) was launched in January 2010, with the ultimate aim of developing core outcome sets for all conditions and treatments16. COMET aims to support the development of core outcome sets by bringing together researchers with an interest in the development, reporting and application of core outcome sets, with a view to establishing robust and efficient methods by which new sets may be developed16. COMET provides a means of identifying existing, ongoing and planned core outcome sets, and provides a free, publicly available internet‐based resource containing over 306 studies relevant to the development of core outcome sets to facilitate the exchange of ideas and information35, 45. Over 300 core outcome sets are currently under development, and standardized endpoints have already been proposed for use in adjuvant breast cancer treatment trials46.

Although this work is novel and was conducted using robust consensus methodology with key stakeholders who were representative of women undergoing reconstructive surgery and the professionals involved in the provision of specialist care, there are some methodological limitations. There is no agreement regarding the optimal methodology for the development of a core outcome set and it is possible that an alternative consensus method may have led to a different final set of items. However, given the scope and setting of this core outcome set, the Delphi process and consensus meetings were considered appropriate and enabled a much larger sample of participants to be involved than other purely face‐to‐face methods would have allowed. The response rate in round 1 was only 51·4 per cent, suggesting that the use of questionnaires and consensus meetings may not have appealed to all stakeholders. Non‐responders may have valued different outcomes to the participants. Data were not collected on these individuals as they did not give consent to participate, so variations between responders and non‐responders could not be explored fully. The use of a robust maximum variation sampling strategy, however, ensured that all predefined stakeholder subgroups were sampled adequately such that the sample was as representative as possible of the women undergoing reconstructive surgery and professionals involved in their care. It was therefore unlikely that any major group was not represented. It is also possible that the composition of the stakeholder groups may have influenced the outcomes selected for inclusion in the final core outcome set. Although early subgroup analysis suggested that different specialties may initially prioritize different outcomes, as the study progressed there was less heterogeneity in the outcomes selected. This convergence of views is likely to represent the fact that the selected items in a core outcome set are only the baseline minimum number to include in all studies, and the stakeholders appreciated that future studies in their particular field could result in the inclusion of additional and specific items as required.

The main limitation of the study is that it was conducted solely within the UK, which has a state‐funded healthcare system. It is unclear to what degree the outcomes valued in this setting would be concordant with those valued in other healthcare systems or cultural settings. This may limit the generalizability of the results. Finally, the core outcome set was developed specifically for RBS without reference to breast cancer or its treatment. As many women undergo RBS following a diagnosis of malignancy, there may be a need to develop and integrate a breast cancer surgery core outcome set to ensure that outcomes that are important in this context are included.

This work has identified a list of core outcome domains to be measured and reported as a minimum in effectiveness studies in RBS. As a core outcome set is not itself a measurement instrument, the next crucial step will be to determine how these key outcomes should be measured; the recently published OMERACT Filter 2.039 provides guidance in this area. Literature reviews will be required to generate a list of available measurement instruments and, where no instruments are available, these will need to be developed. Application of further consensus methods will therefore be necessary to determine what constitutes major, implant‐related and flap‐related complications, and how these should be defined. In addition, the development of a robust instrument to evaluate domains such as normality will be vital if the core outcome set is to be applied in a meaningful way. Application of the principles of truth, discrimination and feasibility39 or, more formally, the COSMIN (COnsensus‐based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments) checklist47 may help to inform the selection of the most appropriate instrument for domains such as physical well‐being and health‐related quality of life where more than one instrument could be used. This additional work will be essential for the core outcome set in RBS to gain widespread acceptance and use.

The BRAVO study has used robust consensus methodology to develop a core outcome set for effectiveness studies in RBS. Its widespread adoption by the reconstructive community will improve the quality of outcome assessment and the value of the work to patients and surgeons. Future work will be necessary to evaluate how these key outcomes should best be assessed.

Collaborators

Members of the Steering Group are collaborators in the study: S. T. Brookes (Centre for Surgical Research, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK), S. J. Cawthorn (Bristol Breast Care Centre, North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol, UK), D. Harcourt (Centre for Appearance Research, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK), R. Macefield (Centre for Surgical Research, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK), R. Warr (Department of Plastic Surgery, North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol, UK), E. Weiler‐Mithoff (Canniesburn Plastic Surgery Unit, Glasgow, UK), P. R. Williamson (Medical Research Council (MRC) North West Hub for Trials Methodology Research, Department of Biostatistics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK) and S. Wilson (Department of Plastic Surgery, North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol, UK).

Supporting information.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1 Categorization of items into domains and categories (Word document)

Appendix S1 Round 1 Delphi questionnaire (Word document)

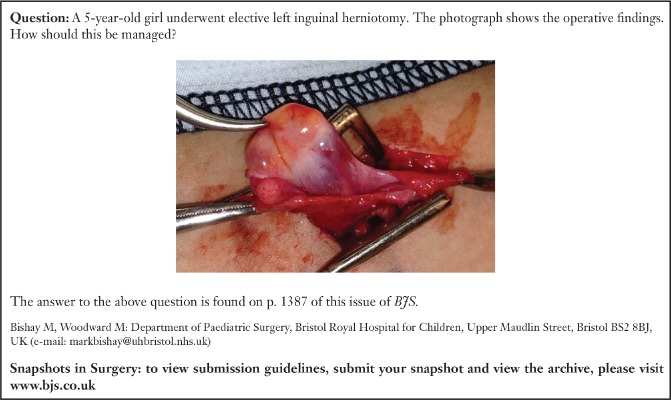

Snapshot quiz 15/10

Supporting information

Table S1 Categorization of items into domains and categories (Word document)

Appendix S1 Round 1 Delphi questionnaire (Word document)

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken with the support of the MRC ConDuCT‐II Hub (Collaboration and innovation for Difficult and Complex randomized controlled Trials In Invasive procedures – MR/K025643/1). P.R.W. is funded by the MRC North West Hub for Trials Methodology Research (grant no. G0800792). S.P. is supported by an Academy of Medical Sciences Clinical Lecturer Starter Grant.

Presented to the 12th European Society of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery Quadrennial Meeting, Edinburgh, UK, July 2014, and the Association of Breast Surgery Meeting, Liverpool, UK, May 2014; published in abstract form as Eur J Surg Oncol 2015; 40: 633–634

The copyright line for this paper was changed on 27 July 2015 after original online publication

References

- 1. Cancer Research UK . Breast Cancer Statistics. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/breast [accessed 24 February 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matala CM, McIntosh SA, Purushotham AD. Immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy for cancer. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 1455–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harcourt D, Rumsey N. Psychological aspects of breast reconstruction: a review. J Adv Nurs 2001; 35: 477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cordeiro PG. Breast reconstruction after surgery for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 1590–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thiruchelvam PT, McNeill F, Jallali N, Harris P, Hogben K. Post‐mastectomy breast reconstruction. BMJ 2013; 347: f5903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rainsbury D, Willett A. (eds). Oncoplastic Breast Reconstruction: Guidelines for Best Practice, Association of Breast Surgery and British Association of Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons; Royal College of Surgeons of England: London, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? BMJ 1999; 318: 318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barratt A. Evidence based medicine and shared decision making: the challenge of getting both evidence and preferences into health care. Patient Educ Couns 2008; 73: 407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Potter S, Brigic A, Whiting PF, Cawthorn SJ, Avery KN, Donovan JL et al Reporting clinical outcomes of breast reconstruction: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103: 31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Potter S, Harcourt D, Cawthorn S, Warr R, Mills N, Havercroft D et al Assessment of cosmesis after breast reconstruction surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18: 813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen C, Cano S, Klassen A, King T, McCarthy CM, Cordeiro PG et al Measuring quality of life in oncologic breast surgery: a systematic review of patient‐reported outcome measures. Breast J 2010; 16: 587–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee C, Sunu C, Pignone M. Patient reported outcomes of breast reconstruction after mastectomy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg 2009; 209: 123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morrow M, Pusic AL. Time for a new era in outcome reporting for breast reconstruction. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103: 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR. Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. PLoS Med 2011; 8: e1000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clarke M. Standardising outcomes for clinical trials and systematic reviews. Trials 2007; 8: 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williamson P, Altman D, Blazeby J, Clarke M, Gargon E. Driving up the quality and relevance of research through the use of agreed core outcomes. J Health Serv Res Policy 2012; 17: 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tugwell P, Boers M. OMERACT Conference on outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials: introduction. J Rheumatol 1993; 20: 528–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duncan PW, Jorgensen HS, Wade DT. Outcome measures in acute stroke trials: a systematic review and some recommendations to improve practice. Stroke 2000; 31: 1429–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williamson PR, Gamble C, Altman DG, Hutton JL. Outcome selection bias in meta‐analysis. Stat Methods Med Res 2005; 14: 515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chan A‐W, Altman DG. Identifying outcome reporting bias in randomised trials on PubMed: review of publications and survey of authors. BMJ 2005; 330: 753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kirkham JJ, Gargon E, Clarke M, Williamson PR. Can a core outcome set improve the quality of systematic reviews? – a survey of the Co‐ordinating Editors of Cochrane review groups. Trials 2013; 14: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kirkham JJ, Boers M, Tugwell P, Clarke M, Williamson PR. Outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis randomised trials over the last 50 years. Trials 2013; 14: 324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ward JA, Potter S, Blazeby JM. Outcome reporting for reconstructive breast surgery: the need for consensus, consistency and core outcome sets. Eur J Surg Oncol 2012; 38: 1020–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ward J, Potter S, Blazeby J; BRAVO study steering group . BRAVO for Breast Reconstruction. http://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2012/02/01/comet-team-bravo-for-breast-reconstruction [accessed 24 February 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Potter S. Investigating the Feasibility of Randomised Clinical Trials in Breast Reconstruction (PhD thesis). University of Bristol: Bristol, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Potter S, Cawthorn S, Mills N, Blazeby J. Investigation of the feasibility of clinical trials in breast reconstruction. Lancet 2013; 381: S88. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Potter S, Mills N, Cawthorn S, Blazeby J. Understanding decision‐making for reconstructive breast surgery: a qualitative study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2012; 38: 458. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Potter S, Mills N, Cawthorn S, Donovan J, Blazeby JM. Time to be BRAVE: is educating surgeons the key to unlocking the potential of randomised clinical trials in surgery? A qualitative study. Trials 2014; 15: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Potter S, Mills N, Cawthorn S, Wilson S, Blazeby J. Exploring inequalities in access to care and the provision of choice to women seeking breast reconstruction surgery: a qualitative study. Br J Cancer 2013; 109: 1181–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Macefield R, Jacobs M, Korfage I, Nicklin J, Whistance RN, Brookes ST et al Developing core outcomes sets: methods for identifying and including patient‐reported outcomes (PROs). Trials 2014; 15: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. COMET Initiative . Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials. http://www.comet-initiative.org [accessed 24 February 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 2000; 32: 1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed methods sampling: a typology with examples. J Mixed Methods Res 2007; 1: 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Williamson P, Altman D, Blazeby J, Clarke M, Devane D, Gargon E et al Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials 2012; 13: 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM et al Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67: 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Singal AG, Higgins PDR, Waljee AK. A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clin Trans Gastroenterol 2014; 5: e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boers M, Brooks P, Strand V, Tugwell P. The OMERACT filter for outcome measures in rheumatology. J Rheumatol 1998; 25: 198–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d'Agostino MA et al Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT Filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67: 745–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gargon E, Gurung B, Medley N, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M et al Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014; 9: e99111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG, Gamble C, Dodd S, Smyth R et al The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 2010; 340: c365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smyth RM, Kirkham JJ, Jacoby A, Altman DG, Gamble C, Williamson PR. Frequency and reasons for outcome reporting bias in clinical trials: interviews with trialists. BMJ 2011; 342: c7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Williamson P, Clarke M. The COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) Initiative: its role in improving Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; (5)ED000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Macleod MR, Michie S, Roberts I, Dirnagl U, Chalmers I, Ioannidis JP et al Biomedical research: increasing value, reducing waste. Lancet 2014; 383: 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gargon E, Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M. The COMET Initiative database: progress and activities from 2011 to 2013. Trials 2014; 15: 279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hudis CA, Barlow WE, Costantino JP, Gray RJ, Pritchard KI, Chapman JA et al Proposal for standardized definitions for efficacy end points in adjuvant breast cancer trials: the STEEP System. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 2127–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL et al The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health‐related patient‐reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63: 737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Categorization of items into domains and categories (Word document)

Appendix S1 Round 1 Delphi questionnaire (Word document)