Abstract

The use of longitudinal methodology as a means of capturing the intricacies in complex organizational phenomena is well documented, and many different research strategies for longitudinal designs have been put forward from both a qualitative and quantitative stance. This study explores a specific emergent qualitative methodology, audio diaries, and assesses their utility for work psychology research drawing on the findings from a four‐stage study addressing transient working patterns and stress in UK temporary workers. Specifically, we explore some important methodological, analytical and technical issues for practitioners and researchers who seek to use these methods and explain how this type of methodology has much to offer when studying stress and affective experiences at work. We provide support for the need to implement pluralistic and complementary methodological approaches in unearthing the depth in sense‐making and assert their capacity to further illuminate the process orientation of stress.

Practitioner points

This study illustrates the importance of verbalization in documenting stress and affective experience as a mechanism for accessing cognitive processes in making sense of such experience.

This study compares audio diaries with more traditional qualitative methods to assess applicability to different research contexts.

This study provides practical guidance and a methodological framework for the design of audio diary research and design, taking into account challenges and solutions for researchers and practitioners.

Keywords: audio diaries, qualitative, stress

Background

Audio diaries are becoming more widely utilized in a variety of social science disciplines and are promoted as having many advantages, such as accessing sense‐making in periods of change and flux, and allowing the researcher to capture phenomena as they unfold, thus increasing immediacy and accuracy of data capture (Monrouxe, 2009). They are often considered as favourable to their written counterparts due to the additional benefits for the participant, such as an ease in completion and lower levels of attrition (Markham & Couldry, 2007). The aim of this study was to explore the usefulness of qualitative audio diaries in furthering our understanding of workplace phenomena, in particular workplace stress, and to provide support and guidance for work psychology practitioners and researchers who may be considering using audio diaries as a qualitative research method or as part of a mixed‐method study.

Over the last 25 years, a number of authors have advocated for the use of qualitative methods in the work psychology field (Locke, Golden‐Biddle, & Reay, 2002; Symon & Cassell, 2012) highlighting their potential to contribute to our understanding of key work psychology issues. More recently, Cassell and Symon (2011) explored the perceptions work psychologists hold about the quality of qualitative enquiry, motivated in part by the ‘concern to enhance the methodological options available to work psychologists’ (p. 634). In this study, we seek to address this challenge by discussing the potential contributions of qualitative audio diaries. Before we can move forward with equipping researchers and practitioners with a broader skill set, we need to understand emergent methodologies in order to capture their contribution (Halbesleben, 2011). Consequently, we provide a detailed account of this emergent methodology by considering its use and design strategies. This study is positioned therefore to address a knowledge gap regarding the practical application of the methodology itself, as well as providing an evaluative framework for assessing the utility of the approach.

We seek to encourage methodological pluralism here. We are not suggesting that any one methodological approach is superior to another, but rather aim to highlight the choices available to work psychology researchers. We recognize that the field of workplace stress is dominated by positivist‐informed approaches and quantitative methods, so here we take a critical realist stance where the validity of a range of both qualitative and quantitative techniques and their power to supplement one another's achievements is embraced. Luthans and Davis (1982) draw distinctions between the dominant approach of nomothetic analysis at the group level (synonymous with a reductionist quantitative approach) and idiographic analysis, reflective of qualitative, ‘subjective’ enquiry. There is a long history of considering the idiographic–nomothetic distinction (Allport, 1937; Windelband, 1894), and we suggest it can serve as a lens through which to illustrate methodological debates within work psychology. Scholars argue that amongst the confusion of varying epistemological and ontological stances, the transition from one approach to the other within a singular study can highlight important contributions above and beyond that of a singular method. We seek to apply this approach to the stress and coping field with the view to illuminating the complementary nature of mixed‐method designs when investigating workplace stress.

The participants in this study were temporary workers. We were interested in the consortium of employees which constitutes the peripheral workforce, as little is known about the collective impact of a range of reported detrimental circumstances upon this group despite a growing trend to examine the disparate areas of unfair treatment that these workforce are thought to experience (for a review, see Crozier & Davidson, 2009). Numerous studies suggest that the day‐to‐day experience of this peripheral workforce can be bleak, encompassing difficulties such as poor pay and benefits; a lack of training and investment in development; poor dysfunctional relationships with other employees; social isolation; stigmatization and discrimination, amongst other negative characteristics (Biggs, Burchell, & Millmore, 2006; Biggs & Swailes, 2006; Ellingson, 1998; Gordon, 1996; Halbesleben & Clark, 2010; Rogers, 1995, 2000; Svensson & Wolvén, 2010). Our specific interests here lay in exploring the stress experiences of this relatively underexplored and non‐standard occupational group to examine the interplay between a range of challenging circumstances and their psychological impact.

The study is structured in the following way. We begin by exploring the use of diary studies in work psychology research, before considering audio diary research and its applicability to examining methodological debates and research gaps in workplace stress. We next outline the research project including the design of the audio diaries. Following this, the findings are presented in two sections: Firstly, to see how the use of diaries extends our understanding of stress at work, and secondly, by considering the participants’ responses to the diary methodology. Finally, we discuss what has been learned about the method and provide some recommendations for its use by other work psychology researchers.

Diary studies in work psychology

In a special edition of this journal on diary studies edited by Van Eerde, Holman, and Totterdell (2005), the editors discuss the rise in diary studies within work psychology, acknowledging a growing trend in capitalizing on the benefits offered by longitudinal designs. A review of the work psychology literature highlights how the use of diary studies is increasing and demonstrates how they have much to contribute to our understanding of a range of work psychology phenomena in particular by taking account of both intra‐ and interindividual variability; overcoming reliance on retrospective accounts; and allowing the measurement of a range of complexity in fluctuating individual and organizational variables (Ohly, Sonnentag, Niessen, & Zapf, 2010). Examples include Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, and Schaufeli's (2009) study of work engagement and financial returns; Zacher and Wilden's (2014) study of leadership and innovation; and Unger, Niessen, Sonnentag, and Neff's (2014) research on time allocation between work and private life. Whilst the majority of diary studies are quantitative in nature, some studies present findings from written qualitative diaries on a range of work psychology topics (Radcliffe & Cassell, 2015). Poppleton, Briner, and Keifer (2008) used qualitative diaries to explore work–non‐work relationships and cite the advantages of the technique as capturing context, immediacy and complexity plus as yielding findings complementary to quantitative studies on similar topics. Clarkson and Hodgkinson (2007) discussed the contribution of the qualitative occupational stress diary claiming it a ‘simple but powerful self‐reflective tool’ (p684) that can complement and extend more traditional (quantitative) methodologies by contributing depth to already established theoretical relationships.

Despite the rise in diary studies of a qualitative nature, relatively few publications devote time towards assessing the specific contribution of qualitative diary studies (Symon, 2004). Notable exceptions include a recent account by Radcliffe (2013) and that of Waddingham (2005) who both discuss the contribution as capturing episodic data of a dynamic nature that is particularly suitable for extrapolating variables that operate outside of the work domain but that are crucial to our interpretation of job roles. Such complexity, they argue, cannot be elucidated from more traditional data collection methods.

However, the use of both quantitative and qualitative diary studies is not without its difficulties. Mazzetti and Blenkinsopp (2012) highlight the limitations of diary studies including the significant demands on participants that lead to high levels of attrition. They suggest that in seeking to make the diary process more straightforward for participants, diaries inevitably become more formulaic thus reducing the richness of the data collected where instructions can be prescriptive and dilute freedom in participant responses. Similarly, Poppleton et al. (2008) note the challenges of competing philosophies in implementing qualitative approaches, where they suggest that the qualitative parameters can lead to some nomothetic summary and introduction of quantitative analysis, which dilutes a qualitative stance but is often necessary in summarizing findings for publication.

Audio diary studies

One method that has been underutilized in work psychology research is audio diaries. Audio diaries involve the audio recording of participants’ responses and reflections over a period of time (Buchanan, 1991). Many of the publications that report the findings of audio diary research are sociological in nature or positioned within the educational field (Monrouxe, 2009; Worth, 2009). A central theme evident in papers discussing this approach is the participatory nature of the methodology; indeed, the construction of personal experience as directed by the participant (as opposed to the researcher) can be viewed as a performance (Latham, 2003) and, moreover, a creative endeavour in the form of a verbal monologue. In audio diaries, the frame of reference sits firmly with the respondents (Hislop, Arber, Meadows, & Venn, 2005), and any directive activity by the researcher needs to be considered in advance of the start of the data collection because the researcher typically has little involvement in the course of gathering accounts from participants. As with other types of diaries, Monrouxe (2009) insists that a key advantage of the technique is the minimization of researcher influence over participants’ responses. This means that audio diaries are potentially useful for capturing phenomena that might otherwise be inaccessible to researchers, specifically capturing private experiences and those that are sensitive and therefore logistically difficult to capture via researcher involvement.

Audio diaries can provide advantages above and beyond those provided by written diaries. The fluidity in speech enables an immediacy of response that may work to overcome the traditional limitations of self‐report methodology over and above the contribution that a written diary can make. Indeed, researchers have suggested that minimal cognitive processing takes place before the recording of traditional diary accounts, thus potentially capturing a more appropriate representation of participants’ current psychological mindset, compared with other methodologies that may rely on retrospective accounts (Bakker & Bal, 2010; Fisher & Noble, 2004). Bernays, Rhodes, and Terzic (2014) suggest that audio diaries provide participants with greater control over how they record their accounts, and researchers who have compared the use of audio diaries to written diaries have suggested that ‘diaries spoken into voice recorders tended to be less structured but often saw the diarist reflect on his or her relation to a particular issue in great depth’ (Markham & Couldry, 2007, p. 684). Researchers have also highlighted pragmatic advantages of audio diaries rather than written diaries when working with particular groups, for example those who have difficulty writing (Harvey, 2011), or older people with eyesight difficulties (Koopman‐Boyden & Richardson, 2013). Furthermore, Hislop et al. (2005) suggest that the use of audio diaries results in higher completion rates than using a written diary format due to the relative convenience of the technique. Therefore, it appears that this method has much to offer work psychologists interested in capturing longitudinal data.

Conceptually, we argue that audio is potentially more accessible in capturing the cognitive processing involved in making sense of stress experiences. Ericsson and Simon (1993) explore the merits of verbal reports as data where oral responses to a probe involve a cognitive process of bringing the information into attention, converting it to a ‘verbalizable code’ and then vocalizing it (p. 16). A distinction is made between concurrent verbal reporting categorized by ‘talking’ and ‘thinking’ aloud in an immediate response to environmental stimuli, and retrospective verbal reporting where such verbalization takes place some time after the exposure to an event. Ericsson and Simon (1993) further delineate between direct and encoded verbalization to correspond to time elapsed between the exposure to the environment and the reporting on one's experience. Similarly, consideration is given to the intermediate processes that can operate between access to the environmental stimuli and retrieval accuracy. Therefore, in seeking to compare written and audio diaries in terms of the cognitive processes in operation, we position written diaries as a potential intermediary that could interfere with the retrieval of information. Hayes and Flower (1986) explain the 3‐step process involved in writing and cognition, where planning and goal setting form the first stage and translating the plans into text then follows, before a final stage of editing and reviewing. We suggest that audio diaries omit the third stage of this process and therefore allow the researcher access to the unfiltered accounts more readily than a written diary.

Conceptual application of audio diaries to stress research

A consideration of debates in work stress methodology helps to assert the broader relevance of methodological debate to the social science and psychology field. A general discourse exists that proposes important complementary contributions of both qualitative and quantitative methods within empirical enquiry. Pawson and Manzano‐Santaella (2012) support the need for dual methods in assessing CMO configuration (context–mechanism–outcome)‐based theorizing, signposting the need for fluid and flexible designs that are mindful of the strengths of realist enquiry as straddling both positivistic and constructivist ideologies and obtaining ‘the best of both worlds by operating in both worlds’ (p. 189). Similarly, Edwards (2005) explores the need for context to shape yet not constrain our methodological choices and suggests the notion of critical realism fits well with changing organizations and landscapes. Within critical realism, Bhaskar (1989) offers a way between the competing epistemologies of positivism and constructivism that facilitates multimethods research design. From this perspective, it is a mistake to start with an epistemological assertion; rather, there are important variations in situation and context which impact upon what happens in organizations, rather than a general series of rules. There is a growing need in work psychology to acknowledge the relevance of research context, not only in terms of how we interpret the applicability of our findings but also in terms of how we select from a range of design frameworks and resultant analytical procedures.

Work‐related stress is an extensively developed subject matter, and the nature of research enquiry on stress at work has evolved to consider a range of research methodologies, including different types of diary studies. For example, Jones and Fletcher (1996) advocate the use of methodologies alternative to the cross‐sectional for investigating work‐related stress, and many studies have utilized diary accounts in unearthing stress and well‐being experiences (Clarkson & Hodgkinson, 2007; Mazzetti & Blenkinsopp, 2012).

We know from the stress and coping literature (Earnshaw & Cooper, 1996; O'Driscoll & Cooper, 2002) that the appraisal process where an individual interprets and evaluates their exposure to stressors is pertinent to how stress outcomes manifest themselves (Dewe, O'Driscoll, & Cooper, 2010). In building on this idea, we position our theoretical framework as deriving from an understanding of some key principles: First, the methodological debates about the need for pluralistic approaches to the extension of quantitative investigation of work‐related stress; and second, the discourse, context and cognition literature with specific reference to the merits of self‐talk and storytelling in capturing the need for narrative approaches to stress phenomena (Van Dijk, 2006).

A need for pluralism in stress research

The widely acknowledged dominant paradigm in stress research is quantitative enquiry at the between‐person approach, not least because the stress phenomenon is an auditable construct typified by its prevalence and existence in different employee populations (Johnson et al., 2005). Recently, there has been a call for the increased use of alternative and qualitative methods for examining the processes that sit below the surface in making sense of stress experience, coping and appraisal (Dewe, 2009; Lazarus, 1999, 2000). Identification of a need for discursive, longitudinal enquiry to accelerate thinking and theory formation is suggested, not always as an alternative to cross‐sectional and/or quantitative approaches but as an addition to them.

Much of the debate surrounding methodological pluralism in stress research is concerned with the juxtaposed nature of different approaches. Folkman and Moskowitz (2004)'s distinction between momentary and retrospective accounts indicates the need for inclusive methodologies that capitalize on the benefits of different methods and perspectives. In shaping our understanding of coping, the authors imply that both can illuminate stress in their own unique ways. Whilst often the momentary approach is considered more accurate and free from distortion given its immediacy, in understanding coping the cognitive processes that develop between exposure to the event and retrospective reporting are indicative of the sense‐making process and are thereby artefacts of coping rather than biases or falsehoods.

Diary studies typically involve a move towards more momentary accounts given their longitudinal nature, yet at the same time capitalize on reflection of one's circumstances, and thus encapsulate both momentary and retrospective elements. Similarly, other seminal reviews cite the need for both a holistic and microanalytic perspective of stress at the inter‐ and intra‐individual level. Lazarus (1999, 2000) put forward the need to assimilate both of these concerns where the notions of analysis (reductive positivistic approach) and synthesis (combining multiple sources or ideas) are of equal import yet traditionally philosophically opposed to one another. He suggested that as stress and coping are dynamic and fluid, analyses that garner rich discursive and narrative accounts over time and intra‐individually are warranted to overcome a reliance on reductive strategies that simplify the processes and their conception. Other researchers have positioned the importance of taking account of within‐person variation in coping (Armeli, Todd, & Mohr, 2005) and suggest that future research needs to explore new technologies for data capture.

In terms of broadening methodological options, we focus our attention on two conceptual contributions of qualitative audio diaries for stress research: First, an increased understanding of the process orientation of stress; and second, exploring meaning in appraisal and coping.

Folkman and Moskowitz (2004) outline the process‐orientated nature of workplace stress whereby the evolving nature of appraisal as a function of ongoing interplay between an individual and their environment can be at odds with cross‐sectional reductionist quantitative scoring systems or checklist approaches. This is especially so when (often unanticipated) changes in environmental stimuli bring about a change in reflection, appraisal and coping that can go unaccounted for in the data capture. Research designs that allow for the multitude of unforeseen circumstances to be documented and contextualized as they occur during the data collection window can offer valuable insights into stress and coping processes. A number of quantitative studies incorporate a process approach (Armeli et al., 2005; Park, Armeli, & Tennen, 2004; Tennen, Affleck, Armeli, & Carney, 2000) that yield interesting differences in between‐ and within‐person data, highlighting the need for focus on significant variation of appraisal and coping at the within‐person level.

As part of the process‐orientation approach, the need to consider how different coping strategies are integrated together within situational parameters, rather than used independently of one another is an important proposition aligned with qualitative enquiry. Here, the researcher is not seeking to quantify whether certain types or strategies of coping are taking place more so than others, but instead seeks to capture the range of different coping strategies and their interplay in influencing the sense‐making process (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004; Lazarus, 2000). For example, traditionally problem‐ and emotion‐focused copings have been juxtaposed with one another, and critical accounts of coping discourse illuminate the complex and interrelated nature of different coping styles and types – Again as a function of the interplay with environmental and intrapersonal complexity (Dewe et al., 2010).

Developments in appraisal research focus on the need for capture of primary appraisal, the complexities of which are often ignored despite its role as the catalyst of coping, and contribution to elucidatory power in documenting the stress experience (Dewe et al., 2010). The need to address the mechanisms of how meaning is assigned to events is paramount if stress research is to progress. Smith and Kirby (2009) investigate relational models of appraisal that place appraisal in the context of its occurrence and assess dispositional and situational factors. The constructs of motivational relevance and congruence are important in determining the intensity and positivity/negativity of emotional response; thus, the appraised importance of the situation plus the appraised desirability of one's circumstances impacts on the individual, arguably more so than the presence of stressors themselves (Dewe et al., 2010).

Cognition, self‐talk, and storytelling

Skinner, Edge, Altman, and Sherwood (2003) assess cognitive restructuring as a strategy that involves appraisal in a way that reframes and adjusts the perception of stressful events to reconcile any tensions and thus minimize distress. We contend that the audio diary tool may serve as a vehicle for illuminating evidence of cognitive restructuring in action. Storytelling theory supports the notion that engaging in verbalization of recent events encourages central cognitive changes such as forming judgements about the environment and one's role within it (McGregor & Holmes, 1999) often in response to alleviating psychological discomfort. The theoretical interplay between storytelling and the person–environment fit model incorporating a data collection method that explores verbalization over time is thus potentially very valuable for exploring affective responses to interpreting one's stress experience.

Furthermore, we liken audio diaries in stress research to the phenomena of self‐talk as an important cognitive coping strategy and a lens through which the researcher can access stress manifestations. Hardy (2006) states that self‐talk often takes the form of overt and external verbal dialogue that is heard by others and is pertinent to making sense of the affective responses to stress exposure. Research on forming stories suggests that the process of deconstructing events and exploring reactions to them allows the emotional impact of an experience to become more manageable (Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999), which would suggest that audio diaries do not just provide a tool for the documentation of stress and coping, but also actively encourage coping to take place.

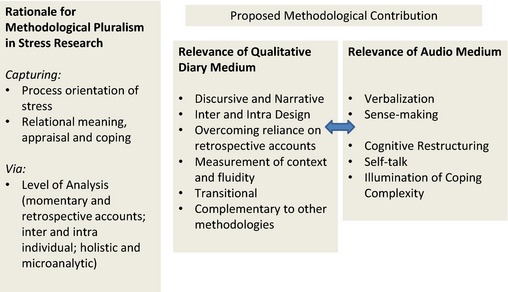

In summary, we argue here that a verbalization methodology enables researchers access to a volunteered reconstruction of events (Martinovski & Marsella, 2003) that provides access to the cognitive processes involved in making sense of stressful encounters. Therefore, we conceptualize important processes that we seek to examine through the audio diary methodology: The delineation of the process‐driven nature of stress, followed by its impact on relational meaning, appraisal and coping. Figure 1 illustrates how the contribution of the qualitative diary and audio medium maps to the need for methodological pluralism in stress research.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

The research project

The data presented herein are drawn from the findings of a sequential four‐staged mixed‐methods study conducted between 2007 and 2009 that made use of both qualitative and quantitative enquiry. We position our study from a critical realist perspective (Bhaskar, 1989) in that ontologically we believe there is a real world independent of our observations, but that we all understand and make sense of that world differently, hence our use of different methods to access those understandings. The study addressed UK temporary clerical agency workers’ experiences of occupational stress. Given that there is little published theory or commentary on the benefits and utility of audio diaries compared to other longitudinal diary designs, we chose to use audio diaries because we wanted to test their worth and capture their value (or lack of) in examining fast‐changing yet underexplored organizational phenomena.

Fifty semi‐structured interviews were conducted at stage one, followed by six idiographic audio diaries at stage two, methodological reflection interviews at stage three, and a large‐scale quantitative survey at stage four. The audio diaries were positioned between the two traditional stages of qualitative interviews and a quantitative survey as we wanted to explore the contribution of audio diaries in extrapolating key themes above and beyond qualitative interview data. The results presented herein are therefore drawn from two stages of data collection; the audio diaries proper to assess their findings relevant to the theoretical context they were used to investigate; and the methodological reflection interviews to capture the experiences of those who participated.

Designing the audio diaries

The approach to diary design was based on an idiographic framework which by definition involves analysis at the singular or individual ‘level’, in this case at participant level. The extant literature on audio diary design (whilst sparse) was influential in informing the design choices, and we employ this approach in response to the need for both intra‐ and interindividual approaches in stress research (Lazarus, 2000) and in emergent diary study designs seeking to explore interpersonal processes (Poppleton et al., 2008). Six participants were selected from their earlier involvement with the interview stage from a pool of 26 volunteers. Participants were selected according to the diversity demographics of age and gender. It was anticipated that sampling across these criteria would serve to illustrate the range of personal and employment circumstances and thus extrapolate important variation in experiences whilst overcoming the homogeneity of sampling common in some other purposive idiographic data strategies (Bakker & Bal, 2010). Other studies utilizing an idiographic approach to audio diaries typically employ a small sample size, where for some a sample as low as four participants (Holt & Dunn, 2004) is reported within a one‐stage methodology. Those with slightly larger sample sizes tend to collectively analyse the integrated findings of their full sample in a nomothetic fashion, in a similar vein to thematic analysis of larger qualitative interview samples (Monrouxe, 2009). Thus, our idiographic approach with six individuals allows a depth of discursive analysis of the time‐dependent variation within a single participant, where the focus is on intraparticipant variability. Table 1 illustrates the participants’ personal and job demographic information.

Table 1.

Personal and job demographics of the diary sample

| Participant gender and age | Job role | In assignment at start of the diary? | Length of time in current assignment | Total length of time in temporary employment | Assignment length expectations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (M) 20 | Administration Assistant (from week 2) | No | n/a | 6 months | n/a |

| B (M) 29 | Sales Administrator | Yes | 3 months | 1 year | 6 months |

| C (M) 56 | Clerical Officer | Yes | 7 weeks | 3 years | Don't know |

| D (F) 19 | Receptionist | Yes | 2 weeks | 2 months | Don't know |

| E (F) 23 | Legal Secretary | Yes | 5 weeks | 6 months | Don't know |

| F (F) 41 | Secretary/PA | Yes | 2 months | 17 months | 4 months |

As with Holt and Dunn (2004) and Holt, Tamminen, Black, Sehn, and Wall (2008), a prompt sheet was designed to provide structure and guidance for participants, whilst at the same time allowing freedom in the amount of time devoted to each prompt reflective of a semi‐structured approach. Issues of attrition were highlighted in some studies as being linked with unstructured enquiry in diary studies (Latham, 2003), so having a framework through which participants could navigate their experiences was deemed useful. Worth (2009) suggests that as participants are likely to have a lack of experience with participation in such studies it is useful to provide a ‘list of questions to start them off’ (p. 11), and other researchers advocate the use of a ‘brief guide’ or suchlike to guide responses (Finnerty & Pope, 2005). Moreover, Boyd et al. (2004) suggest that structure is an aid to encouraging participation where participants in audio diary studies may not record if they are unsure of where to begin – An anxiety potentially exacerbated by the verbal nature of the data gathered. Monrouxe (2009) observes a lack of consistency in participant responses when generic instructions devoid of specific prompts were used. In summary, whilst there appears to be a lack of clear specific guidance in the extant research, the majority of studies recommend embedding some structure to questioning or prompting within audio diary design.

Based on the emergent themes from the earlier qualitative interviews which utilized existing occupational stress theory to explore pertinent stressors for temporary employees, ten prompts were designed as can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Instructions for audio diary and prompt sheet

| Instructions for completion of audio diary | Thank you for agreeing to complete a Work Diary about your experiences as a temporary worker |

You will find enclosed in this pack the following documents:

| |

How to complete the diary study:

| |

| Please carry out your tape recordings on a Wednesday and a Friday each week, after you have finished work for the day. You will be sent a text message to remind you that the tape recording should be carried out on that day | |

| Prompt Sheet | Each time you carry out a tape recording, please comment on the issues below. Please work through them in order |

You can talk in as much or as little detail as you would like. Some of the issues below may be of more relevance to you than others; therefore, you might spend more time on some prompts than on others.

|

Participants were asked to devote as much or as little time to the prompts as they deemed relevant, thus allowing a structure but balancing this with autonomy in shaping their diary accounts (Latham, 2003). An interval‐contingent design (Eckenrode & Bolger, 1995) was employed where participants were asked to record at predetermined intervals, twice weekly for a period of 4 weeks. Participants received a text message to their mobile telephone as a reminder on recording days. At the start of the process, each of the six participants met individually with the researcher. During the meeting, participants were given an instruction pack that included the following: An information sheet about the study; a consent form; an instruction booklet; the prompt sheet; a written diary template for any notes and to record demographic information; and a Dictaphone and tapes.

Similar to what has been reported in other diary studies, there was great variation in length of recordings both within and between participants (Finnerty & Pope, 2005; Monrouxe, 2009), where the shortest recording for any singular diary interview was just under two minutes and the longest twelve minutes. Each participant's total recording time therefore varied significantly, with the most lengthy being 81 min, and the shortest at eleven minutes. The total amount of recording time across the full sample was 287 min. Five of the six participants completed all the recordings across the 4‐week period, with one participant partially completing their recording (omitting three of the eight entries requested). Each participant's diary was transcribed and subject to a thematic analysis at the within‐person level, thus producing six individual accounts.

Evaluating the audio diary experience: Methodological reflection Interviews

Riach (2009) suggests that participant‐situated reflexivity is a useful approach in extrapolating key dimensions about the success or failure of a research strategy; therefore, we chose to interview participants about their experiences of completing audio diaries in order to better understand the technique from the position of the participants, as opposed to a broader deconstruction of the apparent merits and challenges from the researchers’ viewpoint. To this end, after the completion of the audio diaries, each participant was interviewed by the researcher where four broad questions were posed: ‘Can you tell me about your experience of completing an audio diary?’ ‘Which part of the research did you enjoy participating in the most – Audio diaries or earlier interviews? Please give reasons for your choice.’ ‘Did you encounter any difficulties when participating in the audio diary?’ and ‘Do you think audio diaries or written diaries are more suitable in capturing your experiences?’

Data from these interviews were analysed at the nomothetic level by template analysis (King, 2004) allowing identification of codes and associated themes to collectively assess the contribution of the technique across all participants. The analytical path began with overarching themes derived from each of the broad interview questions. Contingent themes were deciphered from higher order themes to form the final template. As this part of the enquiry sought to gain an evaluation of the technique, the positivity or negativity of participants’ responses was captured in assessing the impact of the two questions that assessed the comparison of audio diaries with other techniques, permissible within the flexibility of a template analysis (King, 2004).

Findings

In this section, we first address the contributions of the audio diaries to the subject matter of exploring stress experience within the temporary workforce. Second, the participants’ views of the diary method are presented.

The contribution of audio diaries to our understanding of stress experiences

The findings are positioned around the theoretical principles that influence our conceptual framework.

The process orientation of stress

The idiographic consideration of the participants’ experiences as temporary workers highlighted a range of pertinent issues regarding different phases and stages of the employment cycle, indicative of the transitional nature and adjustment challenges that characterize the experience of this workforce (Garsten, 1999) and indeed that of any workforce in a state of flux, uncertainty or change (Dewe et al., 2010). In the audio diaries, the changing circumstances of participants since their initial interview and throughout the recording process were enlightening. For example, current unemployment was evidenced in the case of participant A:

I'm not working this week…but I didn't know that right ‘til the end of the week before last. On the lunch break I was told I wouldn't be needed on the following Monday… I was a bit annoyed.

Similarly, threats and uncertainty of employment ending midway through the audio diary process in the case of participant C were identified and signified significant challenges:

This is crucial to me, this, what I will talk about now…basically I do not know how long this work will last…everyone is being secretive, managers included. There are Chinese whispers about when X [permanent employee] will be returning – today someone said it was next week…which will leave me in the lurch.

The audio diaries also illustrated movement between a number of temporary assignments over the recording period resulting in the offer of permanent employment and the transition from a temporary to fixed contract for participant E. Here, the relative satisfaction as a function of the different employment situations and their fit with participant E's aspirations and intentions were documented, ranging from dissatisfaction with working in an accountancy firm:

This isn't going to look good on my CV, it doesn't add anything…it has no relevance…I feel I am getting further and further away from getting a permanent role in a law firm… at least it is only for a week;

to a shift in emotional response to the next assignment:

I am glad I am back in a solicitors, it means I can try to gather skills here that will help for my future career, it is a step closer.

The changing responses to these rapidly shifting work patterns highlight the adjustment process and participants’ evaluations of the person–environment fit paradigm in action. We can see evidence of reframing situational factors akin to cognitive restructuring and positive self‐talk (McGregor & Holmes, 1999; Skinner et al., 2003).

Building on the notion of transitional difficulties, a further important consideration around seeking permanent work whilst employed in a temporary role was identified in the audio diaries. A lack of flexibility for time off work within temporary assignments impacted upon participants’ availability to attend interviews for permanent positions:

I have an interview for something but now I'm not allowed the time off from here…I will be temping forever if there is no way they understand that sometimes I might need to take a morning off for something important.

Some of the constraints within the employment situation are seen to act as barriers for routes out of temporary assignments, despite opportunities being available, thus perpetuating an involuntary temporary employment situation.

In summary, the periods of flux and change are captured where the audio diaries thus play out an active illustration of the interaction between a number of different stressors at different time points, described by Dewe et al. (2010) as an important research gap in understanding the manifestation of stress experiences. The role of uncertainty appeared to extensively moderate participants’ reflections on other facets of the working environment, and for each participant, a very different ‘process’ of their employment was evidenced.

Relational meaning, appraisal, and coping

The idiographic application of the audio diary technique allowed the profiling of demographic criteria and the role individual differences played in influencing appraisal and reflection of stress experiences and outcomes. Personal demographics and the motivations for undertaking temporary working appear to impact the intricate relationship between the individual and the stressors present in the work environment. For example, in the case of participant A, the precarious nature of the temporary working environment is appraised as less damaging due to a lack of financial dependence:

I will give it a couple of weeks and if they [the employment agency] don't find me anything I suppose I will look elsewhere…I don't have to rush too much though as I am [living] at home [with parents] so I don't need to worry in the same way other people might.

In contrast, participant B explains his levels of satisfaction with the role as a function of its precarious nature:

There simply is no satisfaction for me being a temp…it is against my work ethic in a way…I want to have something stable…I think it's really annoying, and ironic in a way…as I actually like this job and could get a lot from it, but the issue I have is it is not permanent and as I have said I feel really low about that.

This emphasizes tensions and paradoxes where a positive appraisal of job content is overshadowed by the definition of the role as temporary, thus impacting reflection of fit between the individual and environment. Such discourses are illustrative of the relational appraisal process and its motivational counterparts and responds to a need for research to consider the relatedness of short‐ and long‐term stressors and how individuals make sense of the relative influences of each (Dewe et al., 2010).

The presence of both positive and negative appraisal and coping of the same stressor contingent on situational change was evident. For example, one participant explained their acceptance of a lack of training during one recording:

there is no training…you have to take that as a given I think…I didn't expect to get trained in the same way as the permanent staff. But if you know that and are OK with it then it's fine

but then charted the training need as problematic in their next diary entry:

Today I was a bit bothered with it all to be honest…I didn't know how to enter data into a different system to the one I've used so far…and it was expected by others that I would know…because I've not been trained it was so hard…I had to ask someone who was snowed under and they were a bit annoyed I think…I felt a bit worried.

All participants cited exposure to a range of stressors within their audio diary accounts. Much of the associated appraisal illustrated both positive and negative construction of experience. For example, expression of anxiety as a function of adjustment into new job roles was offset by acceptance of the circumstances and positive restructuring:

…it is important to just try and go with the flow and relax…it is what this way of working is all about…it's not a bad thing really

It has been good for me doing temporary work…having to integrate into new workplaces has been good for my confidence…it is useful to have exposure to this I think.

The differences highlighted between the separate idiographic accounts illustrate that each individual has a unique set of circumstances and preferences that inevitably affect not only the amount of attention they give to each prompt in their audio diary, but also to what extent they evaluate each prompt or potential stressor in a positive or negative light. The audio diary process yields interesting findings as to how individuals understand and make sense of their workplace experiences and their temporal nature. Indeed, Lepine, Podsakoff, and Lepine (2006) suggest that the question still remains as to whether issues pertaining to appraisal and fit between individual and environment are researched in a way that captures the richness and complexity of the stress process. From our findings, we suggest that audio diaries enable the researcher to gain insight into these complexities in a manner that is potentially inaccessible in more traditional research techniques.

Participant methodological reflection interviews

These interviews focused upon participants’ views of the method. We used these interviews in addition to the findings proper to provide further evidence of the contribution of the audio medium.

Positive impact

In terms of positive impact, participants experienced the audio diary process as cathartic in that it helped them to reflect upon and face the challenges in their employment situation, illustrating some pertinent psychological phenomena in the stress management process, akin to cognitive restructuring and self‐talk (Skinner et al., 2003). Indeed, it was seen as providing them with a reflective outlet for the challenges of their employment situation. Similarly, participants suggested the approach helped to develop their self‐awareness and enabled them to capture their future career aspirations, often providing motivation to further their plans for permanent employment via rumination and capitalization of the challenges they faced:

I've been plodding on for a while in this role and it is easy to push the things I don't like to the back of my mind… [doing this] has helped to make me realise I need to get myself sorted and keep looking [for permanent employment].

…doing the diary…has made me think about what I want from a job and what decisions I need to make about my options.

Practicality

In reflecting on their general experiences, an emergent theme was the practicality of the audio diary method. Participants explained that completing the diaries was both convenient and instantaneous:

it just happens, so I can be doing whatever at home and this at the same time…I don't have to take time out or plan around it…only ten minutes of my evening.

You don't have to plan I can just speak it as it comes to mind…which is helpful I suppose…I don't have to spend time before, I can just go with it.

In reflecting on their experiences, participants reflected on the process of completing an audio diary. In particular, issues pertaining to the reminder system and the structure of the prompt sheet resulted in participants feeling guided through the requirements of their involvement:

The list worked well… I would have been a bit stumped without that…, it was like a ticking off of all the things I could mention so it made the process seem simpler than if I just had to speak about me in general.

Similarly, the reminder system of a text message on the day of recording was discussed as a tool that enabled participants to track their progress and assisted them in getting into the habit of recording:

At first I thought I'd remember as it was on my mind as a new thing but the reminder was helpful… I know where I am when the message comes through and it did help me to rely on that…after the first two weeks I was more in the habit but then I might be busy or forget so it was handy…

Comparing audio diaries to interviews

Four of the participants preferred participation in their diary to the earlier qualitative interviews. Audio diaries were considered as preferable to interview participation due to their private and reflective nature. Participants noted that being on their own whilst the recording process took place meant they felt more able to divulge sensitive information relating to the emotional impact of the work environment and felt less self‐conscious in doing so, reflective of the ‘self‐talk’ coping strategy (McGregor & Holmes, 1999):

Half the stuff on the tape I don't think I could have shared across the table, with you sat there… it seemed to come more naturally as I was on my own…having someone in person listening you are expecting, I don't know … some sort of reaction there and then…knowing the interviewer wasn't next to me…you almost forget someone will eventually listen [to the recording]’.

Similarly, with regard to the definition of audio diaries as reflective, here participants focused on the ‘thinking time’ involved in their audio diaries allowing a deeper account to emerge and contrasted this to an interview situation where more basic descriptive accounts are likely, indicative of the contribution of audio diaries as accessing richer cognitive processing of events (Martinovski & Marsella, 2003):

When I do the diary I can sort of think it as I go…or I can pause and then stop for a bit to think more about what it is I want to say….I don't do that in an interview…I would be wasting time or wouldn't come across well…it [the audio diary] is good for this as I have told you more just in my own way and in my own time, if you know what I mean.

Whilst raising potential issues with regard to the benefits of audio diaries as capturing immediacy (Monrouxe, 2009), this does illustrate their usefulness in allowing participants the time for reflection without feeling under pressure to respond immediately, as they might do in an interview situation. We assert that the concurrent versus retrospective verbalization paradigm (Ericsson & Simon, 1993) is helpful here in balancing accuracy of recall with a need for processing of stress experiences and therefore making sense of them in a storytelling capacity (Van Dijk, 2006).

Audio diaries were also seen as preferable to interview participation in allowing control and freedom. Building on the notion of privacy and reflection, autonomy in style and format of speech were valued by participants as well as the flexibility to discuss a range of issues at one's own pace and in an order of one's own choosing:

I can speak about one thing then switch to something else if I wanted to…I didn't really think about the thread of it…there is no conversation it is just me and I valued that as I had no limits on me. I liked how I can choose the things to say with no one bringing me back round or asking me to say less or more about something…it seems more real to me I'd say.

For those participants who preferred participation in interviews, this was acknowledged with reference to interviews as being directive and therefore associated with relieving anxiety regarding how long to discuss an issue or how much attention to devote to it:

When someone asks the questions, I can see how much you want me to say in a way… I know when to stop and I think there's encouragement to carry on if something is important or has a use to what you want to look at.

Difficulties

When asked about any difficulties they encountered with the diary process, participants put forward a number of concerns. Specifically, these were related to the need to have a private ‘space’ to record, without interruption:

As you have to speak you need to be on your own… best to be in a room where no one else is and that can be a struggle sometimes. I had to say to him [family member] ‘don't come in here for a bit’… and there were times when that was hard or not very practical.

Participants also discussed a difficulty of coherence in their narration punctuated with concerns about the style of storytelling that was appropriate or comfortable:

Sometimes I didn't speak it very well, didn't really say it as I would in a conversation… [it] felt a bit weird as you never speak like that usually… I think you need to find your way of doing it and it can be strange to just start talking about something with no one asking you about it in a real life setting…

A related point that emerged was the authenticity of participants’ manner of presenting their information, where they discussed adapting their tone and style of speech during the adjustment to the diary process:

It is a bit like when you do a phone voice, you know? You are conscious you should be clear and you change your accent or the way you might talk about something… I did this less as it [the diary process] went on, but it was hard to really be myself at first. I probably thought more about how I should say things instead of, I don't know, just saying it as it came to me.

However, some concerns were offset by the importance participants assigned to broadcasting their views and contributing to the research process:

I have to admit I have found this difficult and a bit repetitive at times…it has been tiring…but I do really want to tell my story as a temp…this is a great way [to do that]…and make improvements hopefully to the lessons companies should learn.

Audio as preferable to written diaries

The majority stated that an audio diary was preferable to a written one. Participants discussed once more the ease and instant nature of an audio recording and cited this as a convenience. They discussed written diaries as being more onerous, challenging and troublesome for those with less confidence in their written ability:

I don't mind writing things down but I think it's harder…you can't just write in the way that you might talk it over – I don't know, but it's sort of hard to say it in writing and you could struggle and get annoyed if it isn't reading as you thought it would sound.

Similarly, there were participants who discussed drafting diary entries from both an audio and written point of view, suggesting that audio involves less ‘editing’ than written accounts (Hayes & Flower, 1986):

If I was writing then I'd maybe edit it – go back, cross things out, move things around…. with the tape you don't do that…suppose you could re‐record and go over it again but think the temptation isn't there as much as it would be to cross something out in pen.

A related point was that of comfort with the recording process. Indeed, one individual specified that they felt the need to rehearse or pre‐plan their recording due to anxiety and worry over the perception they would convey. This concern illustrated in the quote below has implications for the adjustment to the recording process:

…honestly for the first week I was nervous and felt a bit on show, silly as I know no one could hear me but it was strange, so I wrote a speech and then read it out loud.

Similarly, participants explored the idea that a written account would be more amenable to integrating within their home circumstances and would allow more flexibility with regard to where they conducted their recording:

I think if I was to write it I could do it anywhere… on the train, at work or you know, in front of the TV with other things going on. With this [the diary] you have to take yourself off and box off the time… so in that way it isn't as good.

In summary, the methodological reflection interviews facilitated useful insight into the utility of the audio diary methodology from the participant viewpoint. A range of strengths and weaknesses of this approach are next discussed with reference to the literature.

Discussion and conclusions

Our findings support the utility of audio diaries for exploring and capturing depth and reflection of cognitive systems in action, where the verbalization of the technique permits the elucidation and documentation of coping and appraisal as artefacts of the process orientation of stress (Edwards, 1998; Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999; Van Dijk, 2006). The context also suggests that audio diaries are useful tools for the examination of fluid and transient working patterns in underexplored employee populations. In broadening this applicability, we note Dewe et al.'s (2010) point that stressors continually shift and change as a function of rapidly changing societal, cultural, economic and organizational landscapes and thus in line with our critical realist approach we need to devote attention to the meaning that individuals assign to their experiences and the way that these change as a function of environmental and perceptual changes. We also need to recognize that as with any other method that encourages participant reflection of their experiences, the very act of completing the diary itself may contribute such changes. Indeed this can be seen as a contribution of the method allowing insight not only into the stress experiences themselves but additionally how participants deconstruct and make sense of them in a cognitive and affective manner.

Furthermore, we confirm that such a methodology appears well suited and builds upon the strengths of cross‐sectional and quantitative designs where audio diaries yield useful findings which allow the researcher access to a range of important manifestations of stress. Of specific utility was the attention drawn to the interplay between the precarious nature of the employment situation (a stressor growing in pertinence in all industry sectors – Dewe et al., 2010) and the participants’ ways of both accounting for it and managing the psychological consequences.

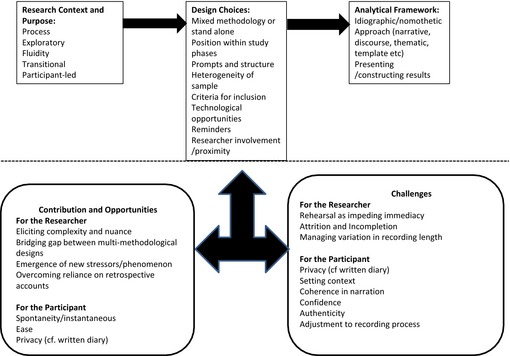

Figure 2 highlights the choices, challenges and contributions of this methodological approach. In considering opportunities and challenges afforded by the audio diary technique, central to our findings is the juxtaposition or dilemma‐centred nature of many of these factors. Although we note the potential strength of participant‐led accounts within a semi‐structured approach characterized by a lack of researcher involvement, we also consider that this is potentially hampered by participants’ reflections as feeling unsure of how to respond (thus impacting recording length, detail and attrition). Equally, the opportunity of immediacy and the verbal nature of the data gathered is what potentially makes audio diaries unique and affords the researcher the advantage of gaining access to participants’ unfiltered and less‐processed accounts (Bakker & Bal, 2010; Markham & Couldry, 2007), yet at the same time we encounter the possibility of participants’ rehearsing their recordings due to anxiety, unfamiliarity with the approach and a reported lack of authenticity. Similarly, whilst participants discussed the convenience of simply recording their responses into an audio device, other participants suggested this impinged on flexibility, where there was a need to be alone in order to record.

Figure 2.

Framework for the use of audio diaries in work psychology.

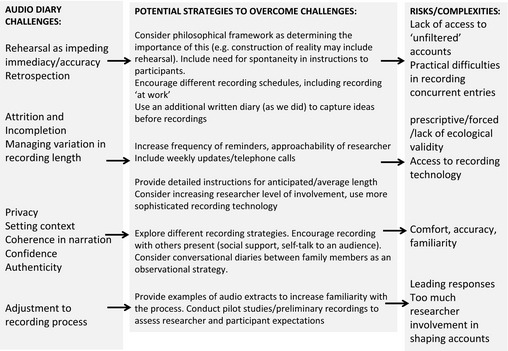

We propose a number of decisions that researchers might consider in alleviating and overcoming audio diary challenges, highlighted in Figure 3, and propose to conduct further research to assess the impact of such design choices.

Figure 3.

Decision framework to address challenges in audio diary design.

Despite the challenges, the technique provided a number of important insights into the world of stress appraisal and coping, where data gathered were plentiful and diverse, and participants appeared to engage fully in the process, supporting claims by researchers that audio diaries are an accessible technique (Bernays et al., 2014; Hislop et al., 2005). Longitudinal methodologies that rely on an extended investment of time from participants are often criticized for their onerous nature and as such are associated with detrimental methodological consequences such as high attrition and missing data (Poppleton et al., 2008). Here, we found support for audio diaries as being more participant‐friendly than written diaries but again refer here to individual characteristics (such as confidence and writing ability) as being potential moderating variables in terms of preference for participation. Equally of merit is the contribution and relevance of audio diaries to a mixed‐methodological approach. As with other diary studies that are positioned between different methodologies (Waddingham, 2005), we found that the data findings here both extended and complemented the earlier qualitative interviews and provided a range of further important factors to incorporate into a quantitative survey. Having said this, this does not mean that diary studies cannot stand on their own; indeed, the richness of data generated suggests that they could be a stand‐alone method in some research designs. We are suggesting here that this is another useful technique to add to the stress researcher's methodological toolkit in embracing pluralism in stress methodology. Finally, we suggest that audio diaries offer something innovative to the work psychology researcher and practitioner. Conceptually, the value that verbalization of stress experiences can bring for both the researcher and participants illuminates the accessibility of the technique in capturing not only the experiences themselves but also the cognitive and affective processes that underpin them.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Marilyn Davidson for her invaluable support and advice with this research study.

References

- Allport, G. (1937). In Hurlburt, R. T., & Knopp, T. J. (2006). Münsterberg in 1898, not Allport in 1937, introduced the terms ‘idiographic’ and ‘nomothetic’ to American Psychology. Theory and Psychology, 16, 287–293. doi:10.1177/0959354306062541 [Google Scholar]

- Armeli, S. , Todd, M. , & Mohr, C. (2005). A daily process approach to individual differences in stress‐related alcohol use. Journal of Personality, Special Issue: Advances in Personality and Daily Experience, 73, 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B. , & Bal, P. M. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: A study among starting teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 189–206. doi:10.1348/096317909X402596 [Google Scholar]

- Bernays, S. , Rhodes, T. , & Terzic, K. J. (2014). Embodied accounts of HIV and Hope: Using audio diaries with interviews. Qualitative Health Research, 24, 629–640. doi:10.1177/1049732314528812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. A. (1989). Reclaiming reality: A critical introduction to contemporary philosophy. London, UK: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, D. , Burchell, B. , & Millmore, M. (2006). The changing world of the temporary worker: The potential HR impact of legislation. Personnel Review, 35, 191–206. doi:10.1108/00483480610645821 [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, D. , & Swailes, S. (2006). Relations, commitment and satisfaction in agency workers and permanent workers. Employee Relations, 28(2), 130–143. doi:10.1108/01425450610639365 [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D. , Egbu, C. , Chinyio, E. , Xiao, H. , Chin, C. , & Lee, T. (2004). Audio diary and debriefing for knowledge management in SMEs. ARCOM Twentieth Annual Conference, Heriot Watt University, pp. 741–747. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, D. A. (1991). Vulnerability and agenda: Context and process in project management. British Journal of Management, 2, 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, C. , & Symon, G. (2011). Assessing good qualitative research in the work psychology field: A narrative analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84, 633–650. doi:10.1111/j.2044‐8325.2011.02009.x [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, G. P. , & Hodgkinson, G. P. (2007). What can occupational stress diaries achieve that questionnaires can't? Personnel Review, 36, 684–700. doi:10.1108/00483480710773990 [Google Scholar]

- Crozier, S. E. , & Davidson, M. J. (2009). The challenges facing the temporary workforce: An examination of stressors, well‐being outcomes and gender differences In Antoniou A., Cooper C. L., Chrousos G. P., Spielberger C. D. & Eysenck M. (Eds.), Handbook of managerial behavior and occupational health, new horizons in management series (pp. 206–217). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Dewe, P. (2009). Coping and appraisals in a work setting: A closer examination of the relationship In Antoniou A.‐S., Cooper C., Chrousos G., Spielberger C. & Eysenck M. (Eds.), Handbook of managerial behaviour and occupational health (pp. 62–76). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Dewe, P. J. , O'Driscoll, M. P. , & Cooper, C. L. (2010). Coping with work stress: A review and critique. Chichester, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw, J. , & Cooper, C. L. (1996). Stress and employer liability. London, UK: Institute of Personnel Development. [Google Scholar]

- Eckenrode, J. , & Bolger, N. (1995). Daily and within‐day event measurement In Cohen S., Kessler R. C. & Gordon L. U. (Eds.), Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 80–101). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J. R. (1998). Cybernetic theory of stress, coping and well‐being: Review and extension to work and family In Cooper C. L. (Ed.), Theories of organizational stress (pp. 122–152). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, P. (2005). The challenging but promising future of industrial relations: Developing theory and method in context‐sensitive research. Industrial Relations Journal, 36, 264–282. doi:10.1111/j.1468‐2338.2005.00358.x [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson, J. E. (1998). Factors relating to the satisfaction and performance of temporary workers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 913–921. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson, K. A. , & Simon, H. A. (1993). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data (Revised ed.). Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Finnerty, G. , & Pope, R. (2005). An exploration of student midwives’ language to describe non‐formal learning in professional practice. Nurse Education Today, 25, 309–315. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2005.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, C. D. , & Noble, C. S. (2004). A with‐in person examination of correlates of performance and emotions while working. Human Performance, 17, 145–168. doi:10.1207/s15327043hup1702 [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S. , & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 745–774. doi:10.1146/annrev.psych55.090902.141456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsten, C. (1999). Betwixt and between: Temporary employees as liminal subjects in flexible organizations. Organization Studies, 20, 601–617. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J. (1996). In Weins‐Tuers, B. A. & Hill, E. T. (2002). Do they bother? Employer training of temporary workers. Review of Social Economy, 60, 543–566. doi:10.1080/0034676022000028064 [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2011). Commentary: A plea for more training opportunities in qualitative methods. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84, 661–665. doi:10.1111/j.2044‐8325.2011.02040.x [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. , & Clark, S. K. (2010). The experiences of alienation among temporary workers in high skilled jobs: A qualitative analysis of temporary firefighters. Journal of Managerial Issues, 22, 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, J. (2006). Speaking clearly: A critical review of the self talk literature. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7(2), 81–97. doi:10.10162fj.psychsport.2005.04.002 [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, L. (2011). Intimate reflections: Private diaries in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 11, 664–682. doi:10.1177/1468794111415959 [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, J. , & Flower, L. (1986). Writing research and the writer. American Psychologist, 41, 1106–1113. doi:10.1037/0003‐066X.41.10.1106 [Google Scholar]

- Hislop, J. , Arber, S. , Meadows, R. , & Venn, S. (2005). Narratives of the night: The use of audio diaries in researching sleep. Sociological Research Online. Retrieved from http://www.socresonline.org.uk/10/4/hislop.html [Google Scholar]

- Holt, N. , & Dunn, J. G. H. (2004). Longitudinal idiographic analyses of appraisal and coping responses in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5, 213–222. doi:10.1016/S1469‐0292(02)00040‐7 [Google Scholar]

- Holt, N. L. , Tamminen, K. A. , Black, D. E. , Sehn, Z. L. , & Wall, M. P. (2008). Parental involvement in youth sport settings. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9, 663–685. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.08.001 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. , Cooper, C. L. , Cartwright, S. , Donald, I. , Taylor, P. , & Millet, C. (2005). The experience of work‐related stress across occupations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(2), 178–187. doi:10.1108/02683940510579803 [Google Scholar]

- Jones, F. , & Fletcher, B. C. (1996). Taking work home: A study of daily fluctuations in work stressors, effects on moods and impacts on marital partners. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 69, 89–106. doi:10.1111/j.2044‐8325.1996.tb00602.x [Google Scholar]

- King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of texts In Cassell C. M. & Symon G. (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 256–270). London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman‐Boyden, P. , & Richardson, M. (2013). An evaluation of mixed methods (diaries and focus groups) when working with older people. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16, 389–401. doi:10.1080/13645579.2012.716971 [Google Scholar]

- Latham, A. (2003). Research, performance, and doing human geography: Some reflections on the diary‐photograph, diary‐interview method. Environment and Planning A, 35, 1993–2017. doi:10.1068/a3587 [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. London, UK: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S. (2000). Toward better research on stress and coping. American Psychologist, 55, 665–673. doi:10.1037/0003‐066X.55.6.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepine, J. A. , Podsakoff, N. P. , & Lepine, M. A. (2006). A meta‐analytic test of the challenge stressor‐hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 764–775. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2005.18803921 [Google Scholar]

- Locke, K. , Golden‐Biddle, K. , & Reay, T. (2002). An introduction to qualitative research: Its potential for industrial and organizational psychology In Rogelberg S. (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 99–118) London, UK: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F. , & Davis, T. R. (1982). An idiographic approach to organizational behavior research: The use of single case experimental designs and direct measures. Academy of Management Review, 7, 380–391. doi:10.5465/AMR.1982.4285328 [Google Scholar]

- Markham, T. , & Couldry, N. (2007). Tracking the reflexivity of the (dis)engaged citizen: Some methodological reflections. Qualitative Inquiry, 13, 675–695. doi:10.1177/1077800407301182 [Google Scholar]

- Martinovski, B. , & Marsella, S. (2003). Dynamic reconstruction of selfhood: Coping processes in discourse. In Proceedings of joint international conference on cognitive science Sydney, NSW, Australia: Institute of Cognitive Science. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzetti, A. , & Blenkinsopp, J. (2012). Evaluating a visual timeline methodology for appraisal and coping research. Journal of occupational and organizational psychology, 85, 649–655. doi:10.1111/j.2044‐8325.2012.02060.x [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, I. , & Holmes, J. G. (1999). How storytelling shapes memory and impressions of relationships over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 403–419. doi:10.1037/0022‐3514.76.3.403 [Google Scholar]

- Monrouxe, L. V. (2009). Negotiating professional identities: Dominant and contesting narratives in medical students’ longitudinal audio diaries. Current Narratives, 1, 41–59. doi:10.1111/j.1365‐2923.2009.03440.x [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll, M. P. , & Cooper, C. L. (2002). Sources and management of excessive job stress and burnout In Warr P. B. (Ed.), Psychology at work (pp. 188–223). London, UK: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Ohly, S. , Sonnentag, S. , Niessen, C. , & Zapf, D. (2010). Diary studies in organizational research: An introduction and some practical recommendations. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9(2), 79–93. doi:10.1027/1866‐5888/a000009 [Google Scholar]

- Park, C. L. , Armeli, S. , & Tennen, H. (2004). Appraisal‐coping goodness of fit: A daily internet study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 558–569. doi:10.1177/0146167203262855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R. , & Manzano‐Santaella, A. (2012). A realist diagnostic workshop. Evaluation, 18, 176–191. doi:10.1177/1356389012440912 [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J. W. , & Seagal, J. D. (1999). Forming a story: The health benefits of narrative. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55, 1243–1254. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097‐4679(199910)55:10<1243:AIDJCLP6<3.0.CO;2‐N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppleton, S. , Briner, R. B. , & Keifer, T. (2008). The roles of context and everyday experience in understanding work–non‐work relationships: A qualitative diary study of white‐ and blue‐collar workers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81, 481–502. doi:10.1348/09631/7908X295182 [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe, L. S. (2013). Qualitative diaries: Uncovering the complexities of work‐life decision‐making. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 8(2), 163–180. doi:10.1108/QROM‐04‐2012‐1058 [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe, L. S. , & Cassell, C. M. (2015). Flexible working, work–family conflict, and maternal gatekeeping: The daily experiences of dual‐earner couples. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88, 835–855. doi:10.1111/joop.12100 [Google Scholar]

- Riach, K. (2009). Exploring participant‐centred reflexivity in the research interview. Sociology, 43, 356–370. doi:10.1177/0038038508101170 [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J. K. (1995). Just a temp – Experience and structure of alienation in temporary clerical employment. Work and Occupations, 22(2), 137–166. doi:10.1177/0730888495022002002 [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J. K. (2000). Temps: The many faces of the changing workforce. New York, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, E. A. , Edge, K. , Altman, J. , & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 216–269. doi:10.1037/10033‐2909.129.2.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. A. , & Kirby, L. D. (2009). Putting appraisal into context: Toward a relational model of appraisal and emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 23, 1352–1372. doi:10.1080/02699930902860386 [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, S. , & Wolvén, L. (2010). Temporary agency workers and their psychological contract. Employee Relations, 32, 184–199. doi:10.1108/01425451011010122 [Google Scholar]

- Symon, G. (2004). Qualitative research diaries In Cassell C. M. & Symon G. (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 98–112). London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Symon, G. , & Cassell, C. (2012). Assessing qualitative research In Symon G. & Cassell C. (Eds.), Organizational qualitative research: Core methods and current challenges (pp. 204–223) London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tennen, H. , Affleck, G. , Armeli, S. , & Carney, M. A. (2000). A daily process approach to coping: Linking theory, research and practice. American Psychologist, 55, 626–636. doi:10.1037/0003‐066x.55.6.626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger, D. , Niessen, C. , Sonnentag, S. , & Neff, A. (2014). A question of time: Daily time allocation between work and private life. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 85(1), 158–176. doi:10.1111/joop.12045 [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T. A. (2006). Discourse, context and cognition. Discourse Studies, 8(1), 159–177. doi:10.1177/1461445606059565 [Google Scholar]

- Van Eerde, W. , Holman, D. , & Totterdell, P. (2005). Editorial: Special section on diary studies in work psychology. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 151–154. doi:10.1348/096317905X40826 [Google Scholar]

- Waddingham, K. (2005). Using diaries to explore the characteristics of work‐related gossip: Methodological considerations from exploratory multimethod research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 221–236. doi:10.1348/096317905X40817 [Google Scholar]

- Windelband, W. (1894). In Hurlburt, R. T., & Knopp, T. J. (2006). Münsterberg in 1898, not Allport in 1937, introduced the terms ‘idiographic’ and ‘nomothetic’ to American Psychology. Theory and Psychology, 16, 287–293. doi:10.1177/0959354306062541 [Google Scholar]

- Worth, N. (2009). Making use of audio diaries in research with young people: Examining narrative, participation and audience. Sociological Research Online, 14(4), 1–11. doi:10.5153/sro.1967 [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, D. , Bakker, A. B. , Demerouti, E. , & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82, 183–200. doi:10.1348/096317908X285633 [Google Scholar]

- Zacher, H. , & Wilden, R. G. (2014). A daily diary study on ambidextrous leadership and self‐reported employee innovation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87, 813–820. doi:10.1111/joop.12070 [Google Scholar]