Abstract

Quality of care is a prominent discourse in modern health‐care and has previously been conceptualised in terms of ethics. In addition, the role of knowledge has been suggested as being particularly influential with regard to the nurse–patient–carer relationship. However, to date, no analyses have examined how knowledge (as an ethical concept) impinges on quality of care. Qualitative semi‐structured interviews were conducted with 26 patients with palliative and supportive care needs receiving district nursing care and thirteen of their lay carers. Poststructural discourse analysis techniques were utilised to take an ethical perspective on the current way in which quality of care is assessed and produced in health‐care. It is argued that if quality of care is to be achieved, patients and carers need to be able to redistribute and redevelop the knowledge of their services in a collaborative way that goes beyond the current ways of working. Theoretical works and extant research are then used to produce tentative suggestions about how this may be achieved.

Keywords: discourse, district nursing, ethics, palliative care, poststructuralism

Knowledge influences the nurse–patient–carer relationship in various ways (Cheek and Porter 1997), but it has not been explored as an ethical concern that alters the quality of care. To explore this, data from a study focusing on patients’ and carers’ views of the quality of their palliative and supportive district nursing care are analysed using a poststructuralist theoretical framework. To provide context, a review and definition of palliative and supportive care and district nursing are presented. In addition, how poststructuralist theory can assist in reconceptualising quality of care and research methods is discussed. Interview data are then presented, followed by a discussion of the relationship of the poststructural framework to other research and theory to interpret the findings.

Palliative and supportive care

Palliative care is defined as follows:

An approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life‐threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.

(Sépulveda et al. 2002, 94–5)

Supportive care extends the time that care begins to prediagnostic stages and incorporates non‐life‐threatening illnesses (National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services 2002). Difficulty accessing palliative care arises when patients are not identified as having palliative care needs (Ahmed et al. 2004). The question – ‘Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next year?’ (Moss et al. 2010) – has been utilised to assess patients’ palliative care needs and provide appropriate support and services. However, such classificatory systems of healthcare provision create significant imbalances of power. For example, the ‘surprise’ question installs healthcare professionals as the ultimate arbiter of deciding care provision; patients’ and carers’ views on their likely mortality in the next year remain unrepresented and unrepresentable. Despite this, the evidence overwhelmingly supports professional input at the end of life (Krammer et al. 2009).

District nursing and palliative care

In the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK), district nurses are registered nurses who provide care in peoples’ homes or community clinics. In other countries, they may be referred to as home‐care nurses. District nursing care has become complex with an increased focus on the management and continued medical treatment of patients who are discharged earlier from hospital (QNI 2011), as well as providing care to prevent hospitalisation (Department of Health 2013).

UK government policy advocates for palliative and supportive home care (Department of Health 2009), and district nurses provide a wide variety of this care in the form of early support visits to build relationships with patients and carers, pain control, symptom management, medication administration, personal care (such as washing and dressing), wound care (Austin et al. 2000; Beaver, Luker and Woods 2000; Griffiths, Ewing and Rogers 2013) and co‐ordinating of other services (Walshe and Luker 2010). District nurses also claim to provide psychological care (Griffiths 1997), but this can be limited in its nature (Griffiths, Ewing and Rogers 2010).

Quality care as ethical care

Ethical theories have been used to assess quality of care (Kuis, Hesselink and Goossensen 2014) but have focused on measuring care which has in itself been argued to be ethically problematic (Nagington, Luker and Walshe 2013). This study utilises poststructural theory to shape an understanding of quality care as ethical care without relying on measurement.

Poststructural morality is often considered in the Nietchzian sense of there being no doer only the deed. Hence, morality focuses more on discourse and the effect it has on subjectivities than the effect of one individual's actions on another (Garber, Hanssen and Walkowitz 2000). Subjectivity can be considered in the Butlerian sense as performative, where subjects must continually perform a variety of discourses to become and remain intelligible in the social world (Butler 1997b, 2005). Thus, performativity challenges the notion of a sovereign subject who has agency over the discourses that they draw upon to construct the self. Instead, performativity relies on a submission to society's power networks. This inherently limits the freedom of a subject to choose the discourses that they perform (Butler 1997b). Such discursive performances have classically been considered in terms of gender and sexuality (Butler 1990), but performative theory can be applied to an array of other discourses (Butler 1997a).

The ethical implications of performativity can be most clearly understood through Deleuze and Guattari's (1988) concept of subjectivities constantly becoming‐other. In brief, becoming‐other is a way of conceptualising subjects performing new discourses or performing old discourses in novel ways, hence moving away from the extant social frameworks that originally brought subjects into existence; becoming‐other therefore can be considered to be at the root of poststructural ethics. Hence, as ethics is a performative endeavour which extends beyond the individual, analytical methods must focus on the way in which discourses produce or preclude a becoming‐other in subjectivities rather than the act of any one individual.

In the case of this study, the patient or carer subjectivity is considered a performative discourse in relation to the social sphere of interest: district nursing care. Consequently, this analysis focuses on whether the discourses in the field of district nursing produce or preclude a becoming‐other in patients’ and carers’ subjectivities.

Deleuze and qualitative research

Deleuzian influences on qualitative research have been conceptualised as processes of plugging in Jackson and Mazzei (2012) and seeking multiple entryways into knowledge production (Mazzei and McCoy 2010). The process of plugging one text (understood as interview data, philosophical works, art, etc.) into another is a key to Deleuzian research methodologies. It conceptualises the underlying process to what Deleuze (in his work with Guattari) describes as rhizomatic knowledge that he places in opposition to arborescent forms of knowledge. For Deleuze, arborescent knowledge is typified by the building up of knowledge in specific fields and the attempt to gain power and legitimacy through the closed systems of language that this creates and extends. Rhizomatic knowledge on the other hand is a way of avoiding, producing forms of knowledge that continue to exert ever‐increasing power, and instead, by constantly shifting and plugging into other forms of knowledge, the effects of power are diffused and challenged (Deleuze and Guattari 1988). It has been argued that this allows ‘previously unthought questions, practices and knowledge [to be produced]’ (Mazzei and McCoy 2010, 504) that go beyond the empirical data or the initial theoretical framework. Plugging in therefore does not finish with the plugging in of data to theory and cannot be thought of as finishing when one has viewed the empirical data through a particular theoretical lens instead plugging in requires that one continue to connect to other fields of research and other theories. Seeking multiple entryways into analysis simply means that analysis need not always start with data. Instead, theory, previous research, art, literature or any other source of knowledge may be used as entryways into knowledge production.

Methods

Recruitment

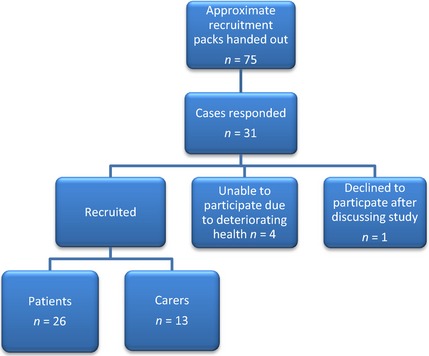

Meetings were arranged with all recruiting healthcare professionals and their managers across five community healthcare organisations and five hospices to discuss the study and explain the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Box 1). Figure 1 summarises the outcome of the recruitment process. Approximate figures are given for distribution of recruitment packs as exact figures were unobtainable due to staff illness and uncertainty.

Box 1. Participant inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

All participants

Over 18 years old

Able to consent

Able to participate in an in‐depth interview

Patients only

Receiving or requiring palliative or supportive care

‘Active’ on a district nursing caseload

Exclusion criteria

All participants

Current contact with the authors in a professional or social capacity

Resident of a nursing or residential home

Carers only

Professional care staff of the patient

Patient declined to be interviewed

Figure 1.

Summary of recruitment process.

Sample characteristics

The sample was balanced in terms of gender (17 male and 14 females) and age (mean 69; range 48–98). However, only two patients were from ethnic minorities, and any self‐defining lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans* (LGBT) individuals were absent. In addition, patients with cancer (n = 18) were the predominant diagnostic group, with non‐malignant (n = 6) and comorbidity (n = 1) underrepresented in comparison with the national average at the time (Office of National Statistics 2010).

One patient (P8) did not disclose her diagnosis or identify with terms such as severe, life limiting or palliative. One patient (P12) had recently undergone potentially curative surgical and medical treatment, but despite these uncertainties still felt, she had received palliative and supportive care from district nurses to cope with her diagnosis and treatment. The remaining 24 patients openly identified as having a severe, life‐limiting or palliative diagnosis. All carers acknowledged diagnosis and prognosis. All patient and carer interviews were included in this analysis.

Data collection

Interviews offered the most appropriate entryway into the field as the research focused primarily on gaining an understanding of patients’ and carers’ views. They have also been identified as being an ethically acceptable method of data collection in palliative care research (Gysels, Shipman and Higginson 2008). An initial semi‐structured research protocol was produced by reviewing the literature and then consulting with a research advisory group. As data collection proceeded, the protocol was iteratively developed by coding participants’ responses (Charmaz 2006). Initial coding aimed neither to abstract too far from the words used by participants nor code in keeping with previous transcripts. This form of coding served as a way to develop the interview protocol and to condense complexity so texts could eventually be plugged into and through each other. In addition to this thematic development of the protocol, an ongoing review of the literature and theoretical works continued to raise alternative themes to explore with participants in interviews, thereby offering multiple entryways into the field. For example, when reviewing the coding of interviews one to six, it became clear that knowledge was something mentioned specifically in interviews P1, C1, P6 and C6 (patients 1 and 6, and carers 1 and 6, respectively) and implicitly in all other interviews. Plugging this into the theoretical framework and other research, it became appropriate to add a section about knowledge in the revised interview protocol. However, there were key limitations to this method as it quickly became apparent that it was not possible to formally revise the protocol after every interview because delaying interviewing patients would frequently have resulted in them dying or becoming too unwell to be interviewed. Therefore, the protocol was formally revised after P6's interview and P18's interview. In addition, it had been planned to do second interviews with all participants to gain a longitudinal understanding of how quality care may change over time. However, due to high morbidity and mortality rates, as well as some participants declining second interviews, only three‐second interviews occurred. Therefore, no analysis is attempted about any of the differences expressed between first and second interviews. Instead, these interviews served as a way to refine analytical ideas.

A summary of the interview characteristics and final protocol topics can be found in Table 1 and Box 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary of interview characteristics

| Patient | Carer | Joint patient–carer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of first interviews | 23 | 10 | 3 |

| Duration of first interviews (minutes) | |||

| Mean | 67 | 53 | 71 |

| Range | 26–109 | 12–109 | 51–109 |

| Number of second interviews | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Duration of second interviews (minutes) | |||

| Mean | 55 | 58 | 61 |

| Range | 40–69 | ||

Box 2. Summary of interview protocol questions.

Interview protocol summary

General experience of district nurses

Relationship with district nurses

Time keeping of district nurses

Experience of care at home

Continuity of district nursing

Previous contact with district nurses

Previous knowledge of district nurses

Discussion of district nurses with others

Use of touch by district nurses

What do patients do for district nurses

Information sheets about district nursing

Data analysis

The themes identified from the initial coding of the data to develop the interview protocol allowed initial entryways into the data. These were then plugged into the theoretical framework to ask the key question ‘does the discourse expressed in this code produce or preclude a becoming‐other in patients’ and carers’ subjectivities?’ A process of memo writing (Clarke 2005) was then undertaken to capture initial analytical insights. Further codes were then plugged into to explore the effect of the initial entryway on patients’ and carers’ subjectivities and further memos were written. However, the themes and entryways did not remain stable; instead, there remained what Jackson and Mazzei (2012) describe as a constant state of flux, where themes merge, split apart and reform to produce new analytical ideas. This resulted in a complex mapping of how discourses produced or precluded a becoming‐other in patients and carers subjectivities. As analysis progressed, it became apparent that while all discourses had moral implications, there were some that plugged into a wider array of discourses than others, often despite the different arrangements that were made; knowledge was one of these. Not only did knowledge connect to and effect a wide range of codes (as described in the empirical data section below) but it also connected to a wide range of theoretical and empirical studies (as described in the Discussion section of this article). As a result, knowledge was mapped as having significant effects on five subthemes, summarised below.

Ethical considerations

All necessary research governance and ethical approvals (NHS committee reference 10/H1013/3) were received. To maintain the anonymity of participants, alphanumeric codes are used, such as P1 for patients and C1 for carers.

Rigour and validity

Poststructuralism suggests rules and structures in themselves cannot lead to claims of validity and rigour (Lather 1993; Rolfe 2006). However, certain aspects of the research will influence the data produced and must be accounted for. For example, only MN conducted interviews and all authors are registered nurses. This inevitably leads to interviews being influenced by MNs own personal biography (in particular his background in palliative and supportive care nursing) and healthcare discourses in general. To ensure there was critical reflection of these influences, all interview transcripts and analyses were reviewed by CW and KL. While participant peer review of this analysis could have further ameliorated these problems (Denzin 2007), patients either died or became too unwell to engage in a peer‐reviewing process of this analysis.

Findings

In the next section, we explore patients’ and carers’ knowledge in relation to district nursing care. We begin by summarising their extant knowledge and how it developed further. We then explore how this compares to their knowledge of their diagnosis and prognosis. Finally, patients’ and carers’ ability to network and how it influences knowledge dissemination are considered.

Patients’ and carers’ extant knowledge of district nursing

In all interviews without exception, patients and carers could not conceive of what district nurses could do for them beyond the current care provision. This lack of knowledge was present before patients and carers met district nurses with patients utilising dated experiences of district nursing and mass media to understand district nursing:

C3: I remember them coming to help my parents … when they were both ill, they both had cancer and died some time ago … that's about all I can remember prior to that.

—

Interviewer: So did you have much of an idea of what district nurses were before [they came to visit you]?

C10: No. My only conception … which is probably untrue, was the sort of things you read in books or see on television.

Patients and carers claimed to have had knowledge on two key aspects of district nursing care: personal care (such as washing and dressing) and biomedical care (such as dressing wounds and administering medications):

P2: They bathe people in bed and things like that, you know.

—

P4: I just thought they went around dressing wounds.

Knowledge of district nurses prior to meeting district nurses was therefore broadly congruent with the historical accounts of the district nursing role that in some cases remained true. For example, dressing wounds still forms a core part of the district nursing role, but tasks such as bathing do not (Walshe and Luker 2010). Mass media did not expand patients’ and carers’ knowledge of district nursing to incorporate other roles such as psychosocial care.

Patients’ and carers’ current knowledge of district nursing

In all but one case (P3), patients’ initial interactions with district nurses were for reasons which involved physical care, such as wound dressings:

Interviewer: So when you say they explained the service what sort of things did they say to you?

P12: They'd say obviously… we've been asked to come X amount of times a week to do these dressings.

Typically, patients and carers were only informed about the care for which they were referred to district nurses for, not other aspects of district nursing. While patients did not report an active avoidance of district nurses discussing topics such as psychological support, there was a lack of knowledge around the district nurses’ roles beyond physical care:

Interviewer: You mentioned… district nurses liaising with other people [to organise psychological support], do you see the district nurses as being the right person suitable to actually do the talking with you and to help you individually?

P19: No… by the time they'd found out I was a bit depressed I think I needed someone else…

Interviewer: So their role then would've been to…

P19: To have contacted someone else, yes.

Interviewer: Do you feel they avoided talking about your emotions and your depression?

P19: No, I just think that they … well, I presume they don't know much about it… I don't know what they're qualified and what they're doing…

There were, however, occasions where psychological care occurred:

P12: One of them one day started asking me things and what‐have‐you and she was sat there and I sort of twigged and I thought she's doing a bit of counselling on me … [she] ended up referring me to [local hospice] … [which] has done me more good than anything.

It appears that if patients are offered psychological care (even if merely in the form of assessment and referral), it is beneficial. However, it frequently did not occur as patients lacked knowledge of it. This suggests that access to psychological support in district nursing care is not just due to ‘blocking behaviours’ as observed by Griffiths et al. (2010). Furthermore, psychological care for carers was inaccessible:

Interviewer: It sounds like … you'd have been in the home, at the same time [as the district nurses visits]…?

C3: Yeah, I think it might have been one and a half, two months… I've always understood that they're there to help the patient first and foremost, if the carer is having problems it's with the carer to find their own solutions … They never specifically came to talk to me and it's been the same right to this day and that's what I expected, to be honest. Although, there's been one district nurse… she'd come downstairs and say, how are you getting on? Are you alright … I appreciated her for that.

This further suggests that knowledge of district nursing was not only limited to physical care, but was limited to physical care of the patient, not the carer.

Knowledge of prognosis and diagnosis versus knowledge of district nursing care

All but one patient (P8) had knowledge around their diagnosis and prognosis, for example:

P25: the kidney doctor … told me I'd only six months.

C25: They said … you were in the final stages [of kidney failure]…

When asked about what district nurses may do when disease progressed (like all participants), P25 and C25 were unable to conceptualise the district nursing role developing:

Interviewer: So do you feel that the district nurses could do anything more for you if you became more unwell at home…?

P25: Like bedfast or anything like that? … they did ask me at [hospital] where did I want to die? Have you booked your funeral? And then I paid for my funeral right away [laughter].

C25: … the way things are at the moment it's fine. But when it starts to deteriorate we don't know what really to expect or what's expected of different people or what, we don't know that yet.

Hence, both P25 and C25 had a realistic idea of the future, even incorporating conversations around preferred places of death. However, this conversation is framed by the patient's and carer's lack of knowledge preventing informed decisions. A lack of knowledge also had other negative impacts:

P24: Is somebody going to tell me what happens… once [local cancer hospital] say there's nothing else we can do … it's just, at the end you do kind of worry, is it going to be a case of a district nurse who will come in every day and give you pain relief, or is it just that you would just ring them up if you feel you need … it's just things that do go through your mind.

Hence, it appears a lack of knowledge produces an uncertainty that is concerning for patients and carers.

Disseminating knowledge

Patients and carers did not receive written information (apart from telephone numbers) about district nursing:

Interviewer: Has anyone ever sat down and talked to you about the [district nursing] service?

C21: No, no.

Interviewer: And you've not had anything written about the service?

C21: No.

Some participants suggested information leaflets to remedy this:

Interviewer: So how do you think you could best learn more about the district nursing service then?

P14: Perhaps a leaflet… just to say that these services are available.

There is limited evidence (from the final three interviews) about how this would be received emotionally:

Interviewer: Would it have upset you getting leaflet saying district nursing palliative care?

P24: No it wouldn't because even ten years ago they told me without chemo that I wouldn't last six months, I had the chemo, I was very lucky that it gave me five years, so if I'd have had a leaflet then, no, it wouldn't have worried me. I'd have just known that that was, you know, the fall back, who would look after me if the chemo didn't work… once you get cancer… you don't necessarily think you're going to get through it… so, no, I think it would be a good thing to know… what there is to help.

Therefore, written information on palliative and supportive care services could be welcomed and not be distressing.

District nursing and the home: an inability to network

There are two specific ways in which district nursing care structured the home. First, through providing care in patients’ homes, district nurses became essential to maintaining patient's homes:

P21: Being away [from home] is not a nice experience, certainly not the one that I went through, but being at home is absolutely vital.

Interviewer: So how important are the district nurses in keeping you at home then?

P21: You know, well, they're vital.

Second, unlike other areas of health‐care, patients and carers were geographically isolated from other recipients of care and only one patient (P26) had previously discussed district nursing care with other patients. Therefore, district nursing care becomes essential to maintaining patients and carers at home but because care is conducted at home, patients and carers struggle to develop knowledge about their district nursing services.

Discussion

Knowledge and poststructural ethics

Patients’ and carers’ knowledge of district nurses primarily relates to physical care for patients. Contact with district nurses did not in itself develop knowledge of district nursing. Hence, unless care such as psychological support was performed by district nurses, knowledge about it did not develop: this hindered accessing care. There were also few ways that patients and carers could develop their knowledge. This was due, in part, to patients’ and carers’ geographical isolation in their homes but also suggests a broader lack of structures to disseminate knowledge about district nursing. This lack of knowledge cannot be generally explained by an inability for patients and carers to understand their diagnosis and prognosis. Instead, there was a generally clear understanding of how illnesses would progress, but a lack of knowledge to link this to how district nurses may be involved with potential future care needs.

Having summarised some of the main findings from this analysis of the data above, we now turn to a consideration of these ideas in relation to other research and theory.

The ethics of developing knowledge about district nursing

There were no reports of discussions about non‐physical or future care provision from district nurses. Hence, physical care (such as dressings) was the predominant knowledge about district nursing care. When knowledge did extend beyond this, it was only because nurses performed care such as psychological support, not because patients exercised any knowledge about such care being accessible. Therefore, the way in which knowledge functions can prevent patients and carers becoming‐other; or to put it another way, if ethical care is to be achieved, patient/carer subjectivities need to be able to expand beyond the predominant discourses (physical care) that are performed by district nurses, towards discourses that would produce alternative subjective positions, such as a patient who can identify themselves as having psychological needs. While physical care itself does not preclude this, nor is it immoral to continue exclusively doing physical care, the way in which knowledge of district nursing is continually restricted to the performance of physical care discourses can be considered to be unethical because any potential for patients’ and carers’ subjectivities to become‐other is restricted or precluded. Hence, if quality care is going to be improved from a poststructural ethics perspective, consideration needs to be given to how the functioning of knowledge can be altered to produce rather than preclude a becoming‐other in patients’ and carers’ subjectivities.

Theoretical strategies on how to reform patients’ and carers’ subjectivities

Knowledge and ways to expand it have been examined from various theoretical perspectives. Some authors espouse a radical approach where anything less than a complete rewriting/reclaiming of one's subjectivity would perpetuate subjugation (Contu 2008; Dick 2008). Other authors suggest a process more properly termed ‘struggle’ where small subversive acts have the potential to lead to wider systematic change (Deetz 2008). While radical rewritings of subjectivity may be productive in other situations, suggesting it in the district nurse–patient/carer relationship seems counter‐productive because of the role district nurses have in sustaining patients at home. A radical approach may result in patients and carers resisting to such an extent that they are left with no home‐care options for the bodily vulnerability that they face towards the end of life. Radical approaches also go against contemporary poststructuralist thinking, which views radical rewritings of subjectivity as being particularly precarious activities to engage in that risk social rejection if one's actions are completely or largely unrecognisable (Butler 1997a). Instead, it has been argued that more gradual and subtle rewritings of subjectivity are more fruitful (Butler 1997a). Therefore, developing knowledge in non‐radical ways will be considered below. The empirical data suggest access to knowledge on district nursing, and an inability to network with other patients and carers to gain knowledge in a patient led way, is particularly relevant to producing a becoming‐other.

Access to knowledge on district nursing

Information leaflets were suggested in the empirical data, thinking about these ideas in relation to Foucauldian theory enables a theorisation of the process of developing a leaflet may need to look like beyond what the empirical data are able to suggest. Foucault highlights that redistributing knowledge is not only reliant on establishing what is legitimate knowledge, but also who has the power to legitimate it (Foucault 2002). Hence, what must be challenged is who has a claim to producing knowledge about district nursing. Foucauldian theory suggests that the production, distribution and legitimisation of knowledge must include patients and carers. To do otherwise would risk further inscribing the district nursing knowledge of palliative and supportive care onto patient–carer subjectivities without any alternative understandings being present; potentially further precluding a becoming‐other by virtue of the power that knowledge has in forming subjectivities. This is not to say that district nurses and management are disallowed involvement; instead, patients and carers must be given equal weighting with regard to what underpins and counts as knowledge about district nurses.

For example, there are limited examples of knowledge being circulated about district nurses by organisations such as the Queens Nursing Institute1 (QNI 2011). However, these documents fail to expand the district nursing role beyond a biomedical/physical care discourse and appear more concerned with maintaining a strict definition of ‘district nurse’ as pertaining to those with a specialist postregistration qualification (QNI 2009, 2014). The empirical data from this study suggest that patients’ and carers’ understanding who ‘district nurses’ are was not what was impacting on the quality of care. Instead, what impacted on the quality of care was the way in which knowledge functioned restricting patients’ and carers’ subjectivities in relation to district nursing. So, while independent, the QNI does not currently appear to help expand patients’ and carers’ knowledge of district nursing services in an ethical manner.

Networking and collective action as resistance

Knowledge as a theme can also be plugged into the idea of networking via the work of Fleming (2008) to conceptualise how a becoming‐other could be produced through social networks. The empirical data suggest that networking between patients and carers receiving district nursing care was problematic because most patients received district nursing care in their own homes. While some patients were in contact with hospice day care services thus come into contact with other patients and carers who received district nursing care, only two patients (P12 and P26) discussed their district nursing care with other patients (in the case of P12, this was prompted by the first interview and reported in her second interview). This suggests that there is little opportunity or impetus for networking by patients and carers receiving district nursing care. However, even if patients and carers were to discuss district nursing care more often, it is unlikely that more than one or two patients would have the same group of district nurses. The potential of knowledge to produce a becoming‐other in these settings is therefore weakened because any sharing of knowledge would be dispersed across a wide range of services within multiple organisations who allocate district nursing resources in differential ways.

A further barrier is the way in which collective actions would function. In this study, the only people who patients and carers met with who could influence their district nursing care were district nurses. Therefore, if an individual wished to resist the discourses and structures of their care, it was their district nurses (or to put it another way, those who are being resisted against and produced knowledge about district nursing) who were left with a responsibility to change the way they acted. There was no report of any structures to seek out patients’ and carers’ views and adapt care accordingly.

While isolation and lack of management structures may remain a reality for many patients and carers, this need not automatically preclude their ability to network and share knowledge via Internet technologies (Zhang et al. 2010; Shirky 2011). Even within health‐care, patients and carers are able in a limited way to collectively influence each other via sites such as NHS choices2 (NHS Choices 2012). However, these do not allow any social networking. Ratings are left, comments are made, but debate and socialising is prevented. Hence, consumerism remains within a framework that resolutely denies debating and networking. While this would appear better than no networking at all, NHS choices do not cover district nursing. However, there is evidence emerging that new forms of social media (such as Facebook) are being used independently by patients to express their views in rudimentary ways such as ‘liking’ a hospital's Facebook page (Timian et al. 2013). This emerging field of social media may allow patients and carers who are geographically isolated to network, challenge and develop knowledge in a patient and carer led way. However, access to and use of social media rely on several privileges such as the financial and educational resources to own and use the appropriate technology. In addition, relying on pages that are managed by the institutions that are offering care may result in a stifling of critical and patient led discussions of care.

Limitations

Despite the Deleuzian methodological aims, there remain limitations to the plugging in that can occur due to the extant social frameworks that research operates within (Kincheloe 2001). One limitation to this study was the heterogeneity in the sample. While there was a balance of genders and a wide spread of ages, patients with cancer were disproportionately represented, a frequent problem in palliative and supportive care research (Ewing et al. 2004). This was despite all recruiters being explicitly asked to include patients regardless of their pathological diagnosis. In addition, the sample only contained two non‐white participants (one first‐generation Jamaican and one second‐generation Asian British), and no self‐defining LGBT people. It is recognised that access of palliative and supportive care is problematic for black and minority ethnic (Calanzani, Koffman and Higginson 2013) and LGBT people (Almack, Seymour and Bellamy 2010). However, it is not possible to know why these individuals are underrepresented in this research as access to caseload demographics was not permitted.

In addition, participants were willing to participate in a study with ‘palliative and supportive care’ in the title of the leaflet and ‘severe and life‐limiting illness’ in the description. Therefore, they may not be representative of the wider palliative and supportive care population where healthcare professionals and service users may differentially understand and identify with these categories.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria (Box 1) that were used by healthcare professionals also created tension for a study that claims to be Deleuzian. However, research ethics committees require clear criteria and disallow direct approaches by research team members to potential participants. Hence, professionals and extant discourses on appropriate research ethics hold significant power over who is counted as a ‘suitable’ participant. While problems around gatekeeping are not unique to palliative care, they are somewhat compounded by the difficulty that professionals have in even discussing palliative and supportive care with patients (Fallowfield, Jenkins and Beveridge 2002). To try and ameliorate this, the patient and carer advisory group helped design the information leaflets and suggested using the phrase ‘severe and/or life limiting’ in the study information leaflet while maintaining ‘palliative and supportive care’ in the title. In addition, the involvement of service users offered reassurance to both the ethics committee and recruiting healthcare professionals.

Finally, high rates of morbidity and mortality meant only three participants engaged in second interviews. This makes it difficult to explore how patients’ and carers’ views of district nursing develop as their illness progresses. A larger sample may help gain further insight into this area.

Conclusion

Knowledge, when considered an ethical endeavour in relation to becoming‐other, impacts on the quality of care that patients and carers receive from district nurses. Several ways of expanding patients’ and carers’ knowledge of district nursing services have been explored, and two key aspects have been argued to be relevant. First, knowledge production about district nursing should have clear involvement of patients and carers without privileging professional discourses. Second, any development of knowledge in this area of health‐care is likely to require novel approaches because of the geographical isolation of this particular social group, utilising information technology is one possible approach.

Finally, quality of care can be reconceptualised as a proactive ethical endeavour where the central aim produces rather than precludes becoming‐other. Knowledge of district nursing care has been demonstrated as a key component in achieving this. However, there remain limits on the way in which a becoming‐other can function in healthcare settings. If, as we suggest above, people have a bodily vulnerability which necessitates some form of support, then within any state funded system, one will need to take discourses of patienthood (private systems may offer a limited opportunity to break free from such discourses, but they are of course replete with economic inaccessibility issues for the majority of the population). While there have been attempts to use the term ‘service user’ instead of ‘patient’, such terms still necessitate one group identifying the other via extant discourses which results in the ethical complexities of how such identifications function on an ethical level. Hence, becoming‐other is not only a proactive ethical endeavour, but a continuous one without an achievable end. Instead, all that can be spoken of are discourses that can produce or preclude more or less ethical forms of care.

Acknowledgement

Funding was provided by the Dimbleby Cancer Care Trust and the University of Manchester Alumni Fund.

Nagington M, Walshe C and Luker KA. Nursing Inquiry 2016; 23: 12–23 Quality care as ethical care: a poststructural analysis of palliative and supportive district nursing care

Footnotes

The Queens Nursing Institute (QNI) is a registered charity which aims to improve the care of people in their own homes. Until the 1960s, they were directly involved in the training of district nurses and still maintain strong links with clinical staff. See http://www.qni.org.uk for further information.

NHS choices is a government built but publicly accessible Website where patients can rate and research healthcare providers. Potential patients can then research hospitals, primary care physicians and dentists to examine which provider they wish to receive care from based on information such as average waiting times for specific procedures and hospital acquired infection rates.

References

- Ahmed N, Bestall JE, Ahmedzai SH, Payne SA, Clark D and Noble B. 2004. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Palliative Medicine 18(6): 525–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almack K, Seymour J and Bellamy G. 2010. Exploring the impact of sexual orientation on experiences and concerns about end of life care and on bereavement for lesbian, gay and bisexual older people. Sociology 44(5): 908–24. [Google Scholar]

- Austin L, Luker K, Caress A and Hallett C. 2000. Palliative care: Community nurses’ perceptions of quality. Quality in Health Care 9(3): 151–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver K, Luker K and Woods S. 2000. Primary care services received during terminal illness. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 6(5): 220–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. 1990. Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. 1997a. Excitable speech: A politics of the performative. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. 1997b. The psychic life of power: Theories in subjection. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. 2005. Giving an account of oneself. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calanzani N, Koffman J and Higginson I. 2013. Palliative and end of life care for black, asian and minority ethnic groups in the UK. London: Marie Curie Cancer Care. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. 2006. Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cheek J and Porter S. 1997. Reviewing Foucault: Possibilities and problems for nursing and health care. Nursing Inquiry 4(2): 108–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AE. 2005. Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Contu A. 2008. Decaf resistance. Management Communication Quarterly 21(3): 364–79. [Google Scholar]

- Deetz S. 2008. Resistance: Would struggle by any other name be as sweet? Management Communication Quarterly 21(3): 387–92. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze G and Guattari F. 1988. A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK. 2007. Grounded theory and the politics of interpretation In The Sage handbook of grounded theory, eds Bryant T. and Charmaz K, 454–71. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . 2009. End of life care strategy quality markers and measures for end of life care. London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . 2013. Care in local communities: A new vision and model for district nursing. London: Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Dick P. 2008. Resistance, gender and bourdieu's notion of field. Management Communication Quarterly 21(3): 327–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing G, Rogers M, Barclay S, McCabe J, Martin A and Todd C. 2004. Recruiting patients into a primary care based study of palliative care: Why is it so difficult? Palliative Medicine 18(5): 452–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA and Beveridge HA. 2002. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: Communication in palliative care. Palliative Medicine 16(4): 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming P. 2008. Beyond power and resistance: New approaches to organisational politics. Management Communication Quarterly 21(3): 301–9. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. 2002. The archaeology of knowledge. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Garber MB, Hanssen B and Walkowitz RL. 2000. Introduction: The turn to ethics In The turn to ethics, eds Garber MB, Hanssen B. and Walkowitz RL, vii–xii. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J. 1997. Holistic district nursing: Caring for the terminally ill. British Journal of Community Health Nursing 2(9): 440–4. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J, Ewing G and Rogers M. 2010. “Moving swiftly on”: Psychological support provided by district nurses to patients with palliative care needs. Cancer Nursing 33(5): 390–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J, Ewing G and Rogers M. 2013. Early support visits by district nurses to cancer patients at home: A multi‐perspective qualitative study. Palliative Medicine 27(4): 349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysels M, Shipman C and Higginson I. 2008. Is the qualitative research interview an acceptable medium for research with palliative care patients and carers? BMC Medical Ethics 9(1): 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AY and Mazzei LA. 2012. Thinking with theory in qualitative research: Viewing data across multiple perspectives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kincheloe JL. 2001. Describing the bricolage: Conceptualizing a new rigor in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry 7(6): 679–92. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer L, Martinez J, Ring‐Hurn E and Williams M. 2009. The nurses’ role in interdisciplinary and palliative care In Palliative care nursing: Quality care to the end of life, eds Matzo M. and Sherman DW, 97–106. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kuis EE, Hesselink G and Goossensen A. 2014. Can quality from a care ethical perspective be assessed? A review. Nursing Ethics 21(7): 774–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lather P. 1993. Fertile obsession: Validity after poststructuralism. The Sociological Quarterly 34(4): 673–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzei L and McCoy K. 2010. Thinking with Deleuze in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 23(5): 503–9. [Google Scholar]

- Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, Auber M, Kurian S, Rogers J et al. 2010. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine 13(7): 837–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagington M, Luker K and Walshe C. 2013. ‘Busyness’ and the preclusion of quality palliative district nursing care. Nursing Ethics 20(8): 893–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services . 2002. Definitions of supportive and palliative care. London: NCHSPCS. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Choices . 2012. Your health, your choices. http://www.nhs.uk/Pages/HomePage.aspx (accessed on 07 April 2014).

- Office of National Statistics . 2010. Deaths by age, sex and underlying cause, 2010 registrations. London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- QNI . 2009. 2020 vision: Focusing on the future of district nursing. London: Queens Nursing Institute. [Google Scholar]

- QNI . 2011. Nursing people at home: The issues, the stories, the actions. London: Queens Nursing Institute. [Google Scholar]

- QNI . 2014. 2020 vision 5 years on: Reassessing the future of district nursing. London: Queens Nursing Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe G. 2006. Judgements without rules: Towards a postmodern ironist concept of research validity. Nursing Inquiry 13(1): 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sépulveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T and Ullrich A. 2002. Palliative care: The world health organization's global perspective. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 24(2): 91–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirky C. 2011. The political power of social media. Foreign Affairs 90(1): 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Timian A, Rupcic S, Kachnowski S and Luisi P. 2013. Do patients “like” good care? Measuring hospital quality via facebook. American Journal of Medical Quality 28(5): 374–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walshe C and Luker K. 2010. District nurses’ role in palliative care provision: A realist review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 47(9): 1167–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Johnson TJ, Seltzer T and Bichard SL. 2010. The revolution will be networked. Social Science Computer Review 28(1): 75–92. [Google Scholar]