Abstract

Purpose

This review article provides an overview of the frequency, burden of illness, diagnosis, and treatment of bipolar disorder (BD) from the perspective of the advanced practice nurses (APNs).

Data sources

PubMed searches were conducted using the following keywords: “bipolar disorder and primary care,” restricted to dates 2000 to present; “bipolar disorder and nurse practitioner”; and “bipolar disorder and clinical nurse specialist.” Selected articles were relevant to adult outpatient care in the United States, with a prioritization of articles written by APNs or published in nursing journals.

Conclusions

BD has a substantial lifetime prevalence in the population at 4%. Because the manic or depressive symptoms of BD tend to be severe and recurrent over a patient's lifetime, the condition is associated with significant burden to the individual, caregivers, and society. Clinician awareness that BD may be present increases the likelihood of successful recognition and appropriate treatment. A number of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments are available for acute and maintenance treatments, with the prospect of achieving reduced symptom burden and increased functioning for many patients.

Implications for practice

Awareness of the disease burden, diagnostic issues, and management choices in BD has the potential to enhance outcome in substantial proportions of patients.

Keywords: Primary care, bipolar disorder, managed care, mental health, nurse practitioners

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic illness associated with severely debilitating symptoms that can have profound effects on both patients and their caregivers (Miller, 2006). BD typically begins in adolescence or early adulthood and can have life‐long adverse effects on the patient's mental and physical health, educational and occupational functioning, and interpersonal relationships (Valente & Kennedy, 2010). Although not as common as major depressive disorder (MDD), the lifetime prevalence of BD in the United States is substantial (estimated at approximately 4%), with similar rates regardless of race, ethnicity, and gender (Ketter, 2010; Merikangas et al., 2007). Long‐term outcomes are persistently suboptimal (Geddes & Miklowitz, 2013). The economic burden of BD to society is enormous, totaling almost $120 billion in the United States in 2009. These costs include the direct costs of treatment and indirect costs from reduced employment, productivity, and functioning (Dilsaver, 2011). Given the burden of illness to the individual and to society, there is an urgent need to improve the care of patients with BD.

There is a growing recognition of the substantial contribution that advanced practice nurses (APNs) such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) can make in the recognition and care of patients with BD (Culpepper, 2010; Miller, 2006). Most patients with BD present initially to primary care providers, but—through a lack of resources or expertise—many do not receive an adequate evaluation for possible bipolar diagnosis (Manning, 2010). Early recognition can lead to earlier initiation of effective therapy, with beneficial effects on both the short‐term outcome and the long‐term course of the illness (Geddes & Miklowitz, 2013; Manning, 2010). Patients with BD are also likely to have other psychiatric and medical comorbidities, and, therefore, rely on their primary care provider for holistic care (Kilbourne et al., 2004; Krishnan, 2005). Finally, the importance of collaborative, team‐based care is increasingly recognized in managing BD. APNs, by their training and experience, are well suited to facilitate optimal patient care in collaboration with the other healthcare team members (Bauer et al., 2006; Chung et al., 2007). An especially important role for APNs within primary care lies in the care of the patient, while specialists manage the bipolar illness. It is essential that these two specialties collaborate in order to stay abreast of each other's current phase of treatment.

This review provides an up‐to‐date discussion of the principles and practices of managing BD in the primary care setting. Our emphasis is on holistic, team‐oriented, multimodal approaches to care, which is compatible with the experience and therapeutic orientation of APNs.

Diagnosis of BD

Definitions in BD

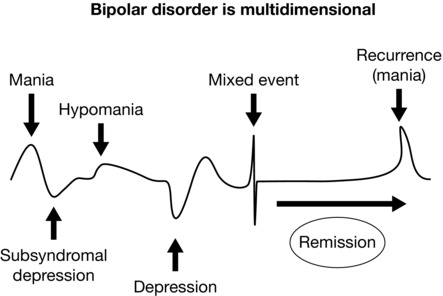

Patients with BD experience recurrent episodes of pathologic mood states, characterized by manic or depressive symptoms, which are interspersed by periods of relatively normal mood (euthymia; Figure 1; Vieta & Goikolea, 2005). Formal definitions of manic and depressive symptoms are included in the recently updated Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Notably, the depressive episodes of BD are defined by the same criteria as MDD in the DSM‐5, so that distinguishing BD from MDD frequently depends on identifying a history of manic or hypomanic symptoms (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Mood range and associated mood diagnosis (Vieta & Goikolea, 2005).

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for BD diagnoses: Overview of DSM‐5

| Episode | Description |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Specifiers | Description |

| Rapid cycling | Four or more episodes of manic, hypomanic, or major depressive episodes |

| during a 12‐month period | |

| Anxious distress | At least two of the following symptoms (on most days during the most recent mood episode):

|

|

|

There are two major types of BD. Bipolar I disorder (BD I) is defined by the presence of at least one episode of mania, whereas bipolar II disorder (BD II) is characterized by at least one episode of hypomania and depression. The main distinction between mania and hypomania is the severity of the manic symptoms: mania results in severe functional impairment, it may manifest as psychotic symptoms, and often requires hospitalization; hypomania does not meet these criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The duration of mood episodes is highly variable, both between patients and in an individual patient over time, but, in general, a hypomanic episode may last days to weeks, a manic episode lasts weeks to months, and a depressive episode may last months to years (Benazzi, 2007; Manning, 2010; Valente & Kennedy, 2010). Although a history of depressive episodes is not required to make a diagnosis of BD I by the DSM‐5 criteria, in practice most patients do experience depressive episodes; however, depressive episodes are required for a diagnosis of BD II. Long‐term studies show that patients with BD, regardless of the subtype, experience symptomatic episodes of depression more frequently and for longer durations than manic or hypomanic episodes (Baldessarini et al., 2010; Geddes & Miklowitz, 2013; Judd et al., 2003; Valente & Kennedy, 2010).

While a mood episode may consist solely of manic or depressive symptoms, it may also include a combination of these symptoms. Such episodes are newly defined in DSM‐5 as either a manic or hypomanic episode with mixed features or a depressive episode with mixed features, depending on which symptoms are predominant (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Table 1).

Rapid cycling is a term describing the occurrence of at least four mood episodes within 1 year. Identification of rapid cycling is important, because these patients are less responsive to treatment. Rapid cycling should be considered a “red flag” that indicates the need for referral to specialist care.

Diagnostic criteria for BD

Successful assessment and treatment by the healthcare team requires knowledge of the episodic nature of BD. Diagnosis of a full‐blown manic episode may be relatively straightforward. If presenting to primary care, these patients may require immediate referral to specialist hospital care because of the risk of harm to self or others. However, more common in the primary care setting is the presentation of patients with depressive symptoms, who require a differentiation between BD and MDD (Cerimele, Chwastiak, Chan, Harrison, & Unutzer, 2013; Sasdelli et al., 2013). For this reason, all patients presenting with depressive symptoms should be assessed for a history of manic or hypomanic symptoms (Cerimele et al., 2013; Sasdelli et al., 2013; Valente & Kennedy, 2010).

Use of a bipolar screening tool is a time‐efficient first step in diagnosis, to be followed by a confirmatory clinical interview. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ, Table 2) and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0), are commonly used screening tools in which scores above specific cut‐off values raise a suspicion of BD (Hirschfeld et al., 2000; Kessler & Ustun, 2004). Web‐based and electronic screening tools are also being developed with the aim of greater time efficiency (Gaynes et al., 2010; Gill, Chen, Grimes, & Klinkman, 2012). A comprehensive recent review of the screening tools in BD is provided by Hoyle, Elliott, and Comer (2015). While screening tools can help to recognize patients likely to have BD and can improve the efficiency of the clinical interview, it is important to note that case‐finding tools are not infallible and cannot replace the interview.

Table 2.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire

| The Mood Disorder Questionnaire bipolar screening tool | ||

| Please answer each question to the best of your ability. | ||

| 1. Has there ever been a period of time when you were not your usual self and … | ||

| YES | NO | |

| You felt so good or so hyper that other people thought you were not your normal self or you were so hyper that you got into trouble? | ||

| You were so irritable that you shouted at people or started fights or arguments? | ||

| You felt much more self‐confident than usual? | ||

| You got much less sleep than usual and found you didn't really miss it? | ||

| You were much more talkative or spoke much faster than usual? | ||

| Thoughts raced through your head or you couldn't slow your mind down? | ||

| You were so easily distracted by things around you that you had trouble concentrating or staying on track? | ||

| You had much more energy than usual? | ||

| You were much more active or did many more things than usual? | ||

| You were much more social or outgoing than usual; for example, you telephoned friends in the middle of the night? | ||

| You were much more interested in sex than usual? | ||

| You did things that were unusual for you or that other people might have thought were excessive, foolish, or risky? | ||

| Spending money got you or your family into trouble? | ||

| 2. If you checked YES to more than one of the above, have several of these ever happened during the same period of time? | ||

|

3. How much of a problem did any of these cause you—like being unable to work; having family, money, or legal troubles; getting into arguments or fights? Please circle one response only.

| ||

| Have any of your blood relatives (i.e., children, siblings, parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles) had manic‐depressive illness or bipolar disorder? | ||

| For a positive screen, 7 of the 13 items in no. 1 must be Yes, no. 2 must be Yes, and no. 3 must be moderate or serious. | ||

Adapted from Hirschfeld et al. (2000).

The clinical interview should aim to establish the following (Manning, 2010; Price & Marzani‐Nissen, 2012):

-

▪

The presence of past or current episodes of manic or depressive symptoms, as described in DSM‐5

-

▪

The duration and severity of these episodes, including the presence of suicidal or homicidal ideation

-

▪

The impact of mood episodes on functioning in work, social, and family roles

-

▪

The presence of comorbidities (such as substance abuse, personality disorder, and anxiety disorder including posttraumatic stress disorder)

-

▪

The history of treatments administered and the response to treatments

-

▪

The family history.

In cases of continued diagnostic uncertainty, a formal diagnosis of BD may require a consultation with an experienced primary care physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, or APN to confirm the presence of DSM‐5 criteria, as well as to categorize the bipolar subtype that is present. The clinical interview, besides establishing the bipolar diagnosis, represents an important element in treatment planning, by helping to select the optimal medication(s) and the optimal site of treatment—either within primary care or by involving specialist psychiatric support. Finally, continued interviews over the course of treatment will help establish rapport and trust with the patient that encourages communication and enhances treatment adherence (Zolnierek & Dimatteo, 2009). Open dialogue between the healthcare worker and patient represents an essential element of patient interviews.

Other elements of the patient interview should include a physical examination and laboratory tests, with the particular aim to exclude disorders that can mimic bipolar symptoms, for example, hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, infection, and substance misuse (Krishnan, 2005). Psychiatric disorders (e.g., panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder) other than MDD can also mimic symptoms of BD and these should be considered in the differential diagnosis (Goldberg, 2010).

In establishing a BD diagnosis, it can be very informative to ask family members or close friends to provide a description of the patient's symptoms (with, of course, the patient's consent). Lack of insight is a characteristic of patients with BD, and hypomanic symptoms, in particular, may not be considered a manifestation of the illness by the patient. This is also an opportunity to assess the burden that family or friends may be experiencing as well as their current relationships with the patient (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health [UK], 2006).

Misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis

Because MDD is more common than BD, and because MDD and BD have similar symptoms, it is very common for BD to be misdiagnosed as MDD (Manning, 2010; Miller, 2006). In one study, over 60% of patients who were eventually diagnosed with BD had previously been misdiagnosed with MDD.

A number of adverse consequences can result from the misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of BD (Hirschfeld, 2007; Manning, 2010; McCombs, Ahn, Tencer, & Shi, 2007). Most importantly, patients with BD who are misdiagnosed with MDD may be treated with conventional antidepressant monotherapy. Compared with appropriately treated patients, such patients are less likely to respond, are at increased risk of a switch to mania, and may experience an acceleration of mood cycling (Manning, 2010; Miller, 2006; Sidor & Macqueen, 2011; Vieta & Valenti, 2013).

Sharing the diagnosis

Discussing the diagnosis with the patient is critical to laying a foundation for effective treatment. The acceptance of a BD diagnosis may be difficult and often occurs over time. The initial diagnosis is frequently provisional, and requires additional observations or confirmatory historical information. It can also be expected that patients will show resistance to the diagnosis, possibly because of the social stigma of having a mental illness. One of the best tools to facilitate acceptance of the diagnosis is motivational interviewing, which is a form of counseling that elicits and strengthens the patient's motivation for change through a process of collaboration and rapport. Motivational interviewing was developed for patients with an alcohol or drug problem, but has been applied more broadly in recent years (Laakso, 2012). Having patience and persistence in helping patients to “own” their BD, and take responsibility for managing it, is an important objective in motivational interviewing (Laakso, 2012).

Treatment

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacological treatment is fundamental for successfully managing patients with BD. For acute episodes, the objective is symptom reduction, with the ultimate goal of full remission. For maintenance treatment, the goal is to prevent the recurrences of mood episodes. Medications used in the treatment of BD include mood stabilizers (e.g., lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine), atypical antipsychotics, and conventional antidepressants (Geddes & Miklowitz, 2013; Hirschfeld, Bowden, & Gitlin, 2002). Table 3 lists the medications that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in treating the different phases of BD.

Table 3.

Medications with FDA indication for treatment of BD

| Acute episode | Maintenance | |||

| Medication | Mania | Depression | Mixed | |

| Mood stabilizers | ||||

| Lithium | M, C | X | M, C | |

| Divalproex, divalproex ER | M, C | X | X | |

| Carbamazepine, carbamazepine ER | M, C | M, C | ||

| Lamotrigine | X | M, C | ||

| Atypical antipsychotics | ||||

| Aripiprazole | M, A | M, A | M, A | |

| Asenapine | M, A | M, A | ||

| Lurasidone | M (BP I) | |||

| Olanzapine | M, A | C (with fluoxetine, BP I) | M, A | M* |

| Quetiapine IR, XR | M, A | M (BP I and II) | M, A (only XR) | A |

| Risperidone | M, A | M, A | M, A (only RLAI) | |

| Ziprasidone | M* | M* | A | |

*Also used adjunctively but not FDA indicated.

A, adjunctive to a mood stabilizer; C, combination therapy with another mood stabilizer, antipsychotic, or antidepressant; M, monotherapy; RLAI risperidone long‐acting injectable; X, recommended in guidelines but not FDA indicated.

Mood stabilizers

Lithium was the first agent to be used in the treatment of BD. Although it has many limitations, including a delayed onset of action in the treatment of acute mania, limited efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression, and a narrow therapeutic window, lithium still has an important role today (Geddes, Burgess, Hawton, Jamison, & Goodwin, 2004; Hirschfeld et al., 2002). In particular, lithium has shown efficacy in preventing recurrence of manic episodes and it is the only medication correlated with a reduced risk of suicide in BD. A study that reduced the lithium dosage (to increase its tolerability) reported no benefit from using lithium plus optimized personalized treatment when compared to optimized personalized treatment alone (Nierenberg et al., 2013).

Sodium valproate is the most commonly used mood stabilizer. It has a more rapid onset of action than lithium for the acute treatment of mania, and was superior to placebo as an acute therapy in the largest study performed to date (Bowden et al., 1994), but the evidence for its efficacy as a maintenance treatment for mania is not so robust (Geddes et al., 2010; Kessing, Hellmund, Geddes, Goodwin, & Andersen, 2011). Placebo‐controlled studies of carbamazepine describe significant efficacy in acute mania (Weisler, Kalali, & Ketter, 2004; Weisler et al., 2005). In the absence of long‐term controlled studies, a naturalistic study over an average of 10 years reported that carbamazepine is efficacious in most patients (Chen & Lin, 2012). Lamotrigine, in contrast to the other mood stabilizers, is more effective for preventing the recurrence of depressive than manic episodes of BD (Vieta & Valenti, 2013). Lamotrigine has also been investigated for the treatment of acute bipolar depression, but the evidence for efficacy is less convincing (Geddes, Calabrese, & Goodwin, 2009). A study of lamotrigine in acute mania reported no significant difference from placebo (Frye et al., 2000).

There are a number of safety and tolerability concerns with mood stabilizers that impact their long‐term use. Lithium requires regular monitoring of blood levels, because the therapeutic window is narrow. Lithium can cause progressive renal insufficiency and thyroid toxicity. After initial assessment of renal and thyroid functions, repeat monitoring of renal and thyroid functions every 6 months is recommended to ensure normal functioning (Price & Heninger, 1994). The most common adverse events associated with lithium include tremors as well as gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Hepatotoxicity is the most common serious adverse event associated with valproate (risk: 1/20,000); other adverse effects include nausea, dizziness, somnolence, lethargy, infection, tinnitus, and cognitive impairment. Monitoring is required for hematologic abnormalities including low platelet count, low white blood count, and, in some cases, bone marrow suppression during valproate therapy (Martinez, Russell, & Hirschfeld, 1998). Carbamazepine is associated with reduced tolerability during rapid dose titration and its potential for interaction with other psychiatric and nonpsychiatric medications further limits its use (Grunze et al., 2009). Carbamazepine has an FDA boxed warning for agranulocytosis and aplastic anemia and is associated in approximately 10% of patients with the formation of a benign rash. Lamotrigine, which is overall the best‐tolerated medication in this class, can cause a rash like the Stevens–Johnson rash. Lamotrigine has been studied specifically in relation to fetal cleft palate formation; however, the evidence remains unconvincing. Fetal exposure to valproate, carbamazepine, and lithium can be teratogenic (Connolly & Thase, 2011; Dodd & Berk, 2004; Geddes & Miklowitz, 2013; Hirschfeld et al., 2002; Tatum, 2006).

Atypical antipsychotics

The atypical antipsychotics were developed in the modern era of psychopharmacology; all agents in this class have been studied by randomized controlled trials in the treatment of BD (Derry & Moore, 2007; Yatham et al., 2013). For the treatment of acute bipolar mania, all approved atypical antipsychotics (also called “second‐generation” antipsychotics) demonstrate efficacy and acceptable safety. For acute bipolar depression, however, few atypical antipsychotics have demonstrated efficacy. Only quetiapine (immediate‐release [IR] and extended‐release [XR] formulations) has proven efficacy as monotherapy for treating acute depressive episodes of BD I or BD II (Table 3; Calabrese et al., 2005; Suppes et al., 2010; Thase et al., 2006). A fixed‐dose combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine has demonstrated efficacy for treating acute depressive episodes of BD I (Tohen et al., 2003) and lurasidone has recently received FDA approval as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy (with either lithium or valproate) in BD I but not BD II (Loebel et al., 2014a, 2014b).

For the maintenance treatment of BD I, FDA‐approved atypical antipsychotics include aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine (IR and XR), risperidone long‐acting injection (LAI), and ziprasidone; these agents are approved either as monotherapy or as adjunctive therapy in combination with a mood stabilizer. A recent meta‐analysis of trials of the atypical antipsychotics in maintenance treatment concluded that aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine (IR or XR), and risperidone LAI monotherapy were statistically superior to placebo for treating manic or mixed episodes, while quetiapine alone was also significantly effective against recurrence of depressive episodes (Vieta et al., 2011).

The safety and tolerability profiles of the atypical antipsychotics have been well characterized in patients with BD. A number of safety issues are associated with these drugs as a class, including sedation/somnolence, metabolic effects (e.g., weight gain, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia), and extrapyramidal side effects (EPS). The relative risk of these effects differs between individual atypical antipsychotics. For example, the risk of adverse metabolic effects is reported to be greatest with olanzapine and lowest with ziprasidone, and intermediate with quetiapine and risperidone (Perlis, 2007). Adjunctive therapies that include atypical antipsychotics in combination with other agents (usually mood stabilizers) are also associated with a greater risk of adverse events than monotherapies (Smith, Cornelius, Warnock, Tacchi, & Taylor, 2007). Given the propensity of atypical antipsychotics to adversely affect weight, lipid levels, and other metabolic parameters, it is important to monitor patients regularly (Hirschfeld et al., 2002; The Management of Bipolar Disorder Working Group, 2010).

Conventional antidepressants

The proper use of conventional antidepressants is an area of controversy in the treatment of BD (Pacchiarotti et al., 2013). The main concern in using antidepressants as monotherapy in patients with bipolar depression is the risk of precipitating a switch to mania/hypomania, which is estimated to occur in between 3% and 15% of cases (Pacchiarotti et al., 2013; Tondo, Baldessarini, Vazquez, Lepri, & Visioli, 2013; Vazquez, Tondo, & Baldessarini, 2011). Another unresolved issue is whether maintenance treatment that includes antidepressants is effective for the prevention of recurrence (Pacchiarotti et al., 2013; Vazquez et al., 2011). If conventional antidepressants are used, it is recommended to combine them with a mood stabilizer or an atypical antipsychotic, and to taper the antidepressant dose following remission of the episode (Amit & Weizman, 2012; Connolly & Thase, 2011; Hirschfeld et al., 2002; Yatham et al., 2013). Contemporary guidelines recommend selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or bupropion rather than selective serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or tricyclics, as SSRIs and bupropion are less likely to cause manic switch. While full consensus is currently absent, there is wide agreement that antidepressant monotherapy should be avoided in patients with BD I and patients with BD II with two or more concomitant core manic symptoms, while antidepressants should be avoided entirely in patients with rapid cycling or those being treated for a mixed episode (Pacchiarotti et al., 2013).

Psychosocial treatments

Psychosocial treatments, including individual psychotherapies as well as educational and supportive group therapies, are increasingly considered an integral part of the treatment of BD (Connolly & Thase, 2011; Geddes & Miklowitz, 2013). Common components of psychosocial treatments are education about the disease and a focus on treatment adherence and self‐care. Interestingly, among the psychosocial treatments, the strongest evidence for effectiveness is for group psychoeducation of patients and caregivers (Colom et al., 2009; Reinares et al., 2008). Long‐term benefits of this approach include a reduction in days with symptoms and in days hospitalized (Colom et al., 2009).

Two other psychotherapies with evidence to support their effectiveness are BD‐specific cognitive behavioral psychotherapy (Jones et al., 2012) and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (Frank et al., 2005). Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy is an intervention designed to increase the regularity of patients’ daily routines, based on the concept that disruption of circadian rhythms is a underlying feature of mood disorders (Frank, Swartz, & Boland, 2007). These therapies can help patients improve adherence to their medication, enhance their ability to recognize triggers to mood episodes, and develop strategies for early intervention. Combining BD‐specific adjunctive psychotherapies with pharmacological therapy has been shown to significantly reduce relapse rates (Scott, Colom, & Vieta, 2007).

Peer support

BD impacts all aspects of a person's life, causing severe disruption to relationships, employment, and education. Peer support can be very helpful in dealing with the consequences of these effects through sharing of experiences, where patients can discover that others have had similar experiences and can have hope for recovery, stability, and a satisfying life. Support groups, sponsored by national organizations, may be available locally or regionally. There is also a wealth of resources available online (Table 4).

Table 4.

Web resources for BD

| Resource | Contact | Summary description of services |

| Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance | www.dbsalliance.org | Recovery‐oriented, nonprofit consumer organization providing easily understandable information on BD treatments and research trials, as well as access to discussion forums and online or face‐to‐face support groups, and training courses for living well with the illness. A special section for caregivers, family, and friends is available. All information is vetted by a scientific advisory board. |

| National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) | www.nami.org | Major national organization offering information, advocacy, |

| Information helpline: 1‐800‐950‐NAMI (6264) | and support to patients and families. Especially valuable for caregivers and families with special educational and support programs. | |

| National Mental Health Information Center (NMHIC) | www.mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/database/ | NMHIC maintains a comprehensive database to help locate mental health services anywhere in the United States, as well as suicide prevention and substance abuse programs. |

| Mental Health America | www.nmha.org | Nonprofit national association that assists patients and their |

| Ph: 1‐800‐969‐6642 | families to find treatment, support groups, and information on issues such as medication and financial concerns around treatment. | |

| International Bipolar Foundation (IBPF) | www.internationalbipolarfoundation.org | Nonprofit international organization provides information (in 60 languages) on bipolar disorder and its treatment, including educational brochures and videos, a newsletter, webinars, and updates on current research. Forums and other resources are also oriented toward caregivers/family members. |

| International Society for Bipolar Disorders | www.isbd.org | Professional international organization fostering research to advance the treatment of bipolar disorders; publishes journal Bipolar Disorders, supports advocacy worldwide, and has a special section for patients and families. |

| Psych Central | www.psychcentral.com | A sponsored, information‐packed website, Psych Central is |

| Ph: 1‐978‐992‐0008 | maintained by a psychologist, Dr. Grohol. It is not specific to BD but covers the disorder comprehensively. Special features include an “ask the therapist” facility and moderated online support groups. |

Major challenges in the management of patients with BD

A number of commonly encountered challenges can contribute to suboptimal outcomes in BD. An awareness of these challenges and the implementation of proactive strategies can help to maximize adherence to care and the benefits of treatment.

Nonadherence

Medication nonadherence is a significant problem in primary care medicine generally, and in patients with BD in particular. Experience from other areas of medicine suggests that nonadherence may be widely unrecognized (Ho, Bryson, & Rumsfeld, 2009). Validated scales for gauging nonadherence include the Morisky Adherence Scale, although this is not widely adopted in clinical practice (Morisky, Ang, Krousel‐Wood, & Ward, 2008). Reasons for nonadherence among patients with BD include the following: a denial of the diagnosis, especially in those with predominant mania; a lack of belief that the medications being offered are necessary or effective; and a wish to avoid the real or imagined adverse effects of medications (Devulapalli et al., 2010). Additional practical factors, including poor access to health care and limited resources to support treatment costs, can also affect adherence (Kardas, Lewek, & Matyjaszczyk, 2013).

Nonadherence is probably the most significant factor contributing to poor treatment outcome in BD (Hassan & Lage, 2009; Lew, Chang, Rajagopalan, & Knoth, 2006), which leads to increased emergency room visits and hospitalization (Hassan & Lage, 2009; Lage & Hassan, 2009; Lew et al., 2006; Rascati et al., 2011). Investing more time and resources to work with patients during symptom‐free periods is likely to be cost saving by reducing the utilization of these high‐cost resources (Zeber et al., 2008).

Comorbid psychiatric disorders

The complexity in treating patients with BD is increased by the high rates of cooccurring psychiatric disorders, in particular anxiety disorders and substance use disorders (Grant et al., 2005; Krishnan, 2005). The importance of these cooccurring conditions cannot be overstated; they are associated with both exacerbations of BD and poor treatment outcomes (Grant et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 1996). Although it may be prudent to refer such patients to specialist care, the first critical step is to make a correct diagnosis and to help these patients to accept the problem and the need for treatment.

Comorbid medical disorders

Patients with BD have an elevated prevalence of medical morbidities, including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hepatitis (Kilbourne et al., 2004; Krishnan, 2005). A comorbidity of increasingly recognized importance is obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which causes sleep disturbance that can trigger mood episodes (Soreca, Levenson, Lotz, Frank, & Kupfer, 2012). A recent study reported OSA in over 20% of patients with BD, which the authors mention may be an underestimate of the true prevalence (Kelly, Douglas, Denmark, Brasuell, & Lieberman, 2013). The authors concluded that unrecognized OSA may play a major role in the mortality and morbidity of BDs. All patients diagnosed with a BD should be screened with an OSA questionnaire.

The burden of medical disorders may be increased by the adverse effects of BD treatment, by cooccurring substance misuse or by decrements in self‐care secondary to BD itself (McIntyre, 2009). For example, depression typically deprives patients of the motivation and energy to engage in treatment for chronic medical conditions. Early recognition and treatment of medical disorders in patients with BD has been shown to have a major beneficial effect on all‐cause mortality (Crump, Sundquist, Winkleby, & Sundquist, 2013).

Women of childbearing age

Women are at high risk of BD recurrence during pregnancy, especially if medications are discontinued, as well as during the postpartum period. Balancing the risk of medications against the need to prevent a mood episode requires active collaboration between the healthcare providers and the patient (McKenna et al., 2005). Teratogenicity is a potential risk with most of the mood stabilizers; lamotrigine may be an exception, but there are no well‐controlled studies in humans to confirm this. Atypical antipsychotics, with the exception of lurasidone, are rated FDA pregnancy category C, meaning that they have not been shown to be either safe or unsafe for use during pregnancy; lurasidone is classed in pregnancy category B based on current data.

Suicide

Suicide rates in BD are the highest among the psychiatric disorders (Chen & Dilsaver, 1996; Tondo, Isacsson, & Baldessarini, 2003). The lifetime incidence of at least one suicide attempt was reported in one study to be 29% in patients with BD, compared to 16% for MDD (Chen & Dilsaver, 1996). Other studies have reported even higher rates of suicide attempts of 25%–60% during the course of BD, with suicide completion rates of 14%–60% (Sublette et al., 2009). The primary healthcare team should monitor all patients with BD for suicidality, especially those with persistent depressive or mixed‐mood symptoms, and immediately refer any patient at high‐risk for suicide to specialist care (Tondo et al., 2003).

Alcohol abuse in patients with BD is associated with further elevation in the risk of suicide, particularly in the presence of concurrent drug use disorders. A study that investigated this association concluded that higher suicide attempt rates in patients with BD I and alcoholism were mostly explained by higher aggression scores, while the higher rates of attempted suicide associated with other drug use disorders appeared to be the result of higher impulsiveness, hostility, and aggression (Sublette et al., 2009). This study, similar to previous reports, found that earlier age of bipolar onset increased the likelihood that alcohol use disorder would be associated with suicide attempts. Effective clinical management of substance use disorders has the potential to reduce the risk of suicidal behavior in these patients with BD.

Conclusions

BD continues to represent a substantial burden to patients, their care providers, and society. Management of BD poses a challenge to all healthcare providers, including the APNs. A suspicion of BD increases the likelihood of successful diagnosis. Emphasis should be placed on accurately identifying manic, hypomanic, and depressive episodes. A number of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments are available for acute and maintenance treatments. Healthcare providers should be aware of the efficacy and safety profiles of each of these agents, with the aim to achieve the most effective utilization of the approaches available in the management of patients with BD. An awareness of these aspects in BD—disease burden, diagnostic issues, and management choices—can enhance outcome in substantial proportions of patients. In summary, Table 5 provides a useful overview of the principles to consider when providing care for patients with BD.

Table 5.

Principles of providing care for patients with BD

| Prepare | Provide psychiatric | Provide medical | Provide support | |

| the practice | Diagnose BD | treatment | treatment | and counseling |

|

|

|

|

|

Red flags indicating need for specialist involvement:

▪ Suicidality

▪ Pregnancy and postpartum

▪ Severe psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., substance dependence, anxiety)

▪ History of treatment resistance (e.g., multiple hospitalizations)

▪ Rapid‐cycling pattern.

Adapted from Culpepper (2010).

Funding Editorial support was provided by Bill Wolvey of PAREXEL, funded by AstraZeneca.

Disclosure Ursula McCormick has received personal fees from AstraZeneca and Sunovian. Bethany Murray and Brittany McNew report no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, B. H. , & Weizman, A. (2012). Antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression: An update. Depression Research and Treatment, 2012, 684725. doi:10.1155/2012/684725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini, R. J. , Salvatore, P. , Khalsa, H. M. , Gebre‐Medhin, P. , Imaz, H. , Gonzalez‐Pinto, A. , … Tohen, M. (2010). Morbidity in 303 first‐episode bipolar I disorder patients. Bipolar Disorders, 12, 264–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M. S. , McBride, L. , Williford, W. O. , Glick, H. , Kinosian, B. , Altshuler, L. , … Sajatovic, M. (2006). Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: Part II. Impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatric Services, 57(7), 937–945. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.7.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benazzi, F. (2007). Bipolar II disorder: Epidemiology, diagnosis and management. CNS Drugs, 21(9), 727–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, C. L. , Brugger, A. M. , Swann, A. C. , Calabrese, J. R. , Janicak, P. G. , Petty, F. , … Frazer, A. (1994). Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. The Depakote Mania Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Association, 271, 918–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, J. R. , Keck, P. E., Jr. , Macfadden, W. , Minkwitz, M. , Ketter, T. A. , Weisler, R. H. , … Mullen, J. (2005). A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1351–1360. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerimele, J. M. , Chwastiak, L. A. , Chan, Y. F. , Harrison, D. A. , & Unutzer, J. (2013). The presentation, recognition and management of bipolar depression in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28, 1648–1656. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2545-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. W. , & Dilsaver, S. C. (1996). Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other Axis I disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 39, 896–899. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. H. , & Lin, S. K. (2012). Carbamazepine treatment of bipolar disorder: A retrospective evaluation of naturalistic long‐term outcomes. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 47. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H. , Culpepper, L. , de Wester, J. N. , de Wester, J. N. , Grieco, R. , Kaye, N. S. , … Ross, R. (2007). Challenges in recognition, clinical management, and treatment of bipolar disorders at the interface of psychiatric medicine and primary care. Current Psychiatry, 6(11). Retrieved from http://www.currentpsychiatry.com/education-center/education-center/article/challenges-in-recognition-clinical-management-and-treatment-of-bipolar-disorder-at-the-interface-of-psychiatric-medicine-and-primary-care/a3b717e8fc79bbb15d27bf9352f872f5.html. [Google Scholar]

- Colom, F. , Vieta, E. , Sanchez‐Moreno, J. , Goikolea, J. M. , Popova, E. , Bonnin, C. M. , & Scott, J. (2009). Psychoeducation for bipolar II disorder: An exploratory, 5‐year outcome subanalysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 112(1–3), 30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, K. R. , & Thase, M. E. (2011). The clinical management of bipolar disorder: A review of evidence‐based guidelines. Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 13, pii: PCC.10r01097. doi:10.4088/PCC.10r01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump, C. , Sundquist, K. , Winkleby, M. A. , & Sundquist, J. (2013). Comorbidities and mortality in bipolar disorder: A Swedish national cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 931–939. doi:1714400[pii];10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culpepper, L. (2010). The role of primary care clinicians in diagnosing and treating bipolar disorder. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 12(Suppl 1), 4–9. doi:10.4088/PCC.9064su1c.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derry, S. , & Moore, R. A. (2007). Atypical antipsychotics in bipolar disorder: Systematic review of randomised trials. BMC Psychiatry, 7, 40. doi:1471‐244X‐7‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devulapalli, K. K. , Ignacio, R. V. , Weiden, P. , Cassidy, K. A. , Williams, T. D. , Safavi, R. , … Sajatovic, M. (2010). Why do persons with bipolar disorder stop their medication? Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 43, 5–14. Retrieved from PM:21150842. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilsaver, S. C. (2011). An estimate of the minimum economic burden of bipolar I and II disorders in the United States: 2009. Journal of Affective Disorders, 129, 79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, S. , & Berk, M. (2004). The pharmacology of bipolar disorder during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 3, 221–229. doi:10.1517/eods.3.3.221.31074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, E. , Swartz, H. A. , & Boland, E. (2007). Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy: An intervention addressing rhythm dysregulation in bipolar disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 9, 325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, E. , Kupfer, D. J. , Thase, M. E. , Mallinger, A. G. , Swartz, H. A. , Fagiolini, A. M. , … Monk, T. (2005). Two‐year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 996–1004. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye, M. A. , Ketter, T. A. , Kimbrell, T. A. , Dunn, R. T. , Speer, A. M. , Osuch, E. A. , … Post, R. M. (2000). A placebo‐controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20, 607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynes, B. N. , DeVeaugh‐Geiss, J. , Weir, S. , Gu, H. , MacPherson, C. , Schulberg, H. C. , … Rubinow, D. R. (2010). Feasibility and diagnostic validity of the M‐3 checklist: A brief, self‐rated screen for depressive, bipolar, anxiety, and post‐traumatic stress disorders in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine, 8, 160–169. doi: 10.1370/afm.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, J. R. , Burgess, S. , Hawton, K. , Jamison, K. , & Goodwin, G. M. (2004). Long‐term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: Systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, J. R. , Calabrese, J. R. , & Goodwin, G. M. (2009). Lamotrigine for treatment of bipolar depression: Independent meta‐analysis and meta‐regression of individual patient data from five randomised trials. British Journal of Psychiatry, 194, 4–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, J. R. , Goodwin, G. M. , Rendell, J. , Azorin, J. M. , Cipriani, A. , Ostacher, M. J. , … Juszczak, E. (2010). Lithium plus valproate combination therapy versus monotherapy for relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder (BALANCE): A randomised open‐label trial. Lancet, 375, 385–395. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61828-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, J. R. , & Miklowitz, D. J. (2013). Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet, 381, 1672–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60857-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, J. M. , Chen, Y. X. , Grimes, A. , & Klinkman, M. S. (2012). Using electronic health record‐based tools to screen for bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 25(3), 283–290. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.110217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, J. F. (2010). Differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder. CNS Spectrums, 15(2 Suppl 3), 4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, B. F. , Stinson, F. S. , Hasin, D. S. , Dawson, D. A. , Chou, S. P. , Ruan, W. J. , & Huang, B. (2005). Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 1205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunze, H. , Vieta, E. , Goodwin, G. M. , Bowden, C. , Licht, R. W. , Moller, H. J. , & Kasper, S. (2009). The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: Update 2009 on the treatment of mania. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 10, 85–116. doi: 10.1080/15622970902823202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M. , & Lage, M. J. (2009). Risk of rehospitalization among bipolar disorder patients who are nonadherent to antipsychotic therapy after hospital discharge. American Journal of Health‐System Pharmacy, 66, 358–365. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld, R. M. (2007). Screening for bipolar disorder. American Journal of Managed Care, 13(7 Suppl), S164–S169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld, R. M. , Bowden, C. L. , & Gitlin, M. J. (2002). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved from http://dbsanca.org/docs/APA_Bipolar_Guidelines.1783155.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld, R. M. , Williams, J. B. , Spitzer, R. L. , Calabrese, J. R. , Flynn, L. , Keck, P. E., Jr. , … Zajecka, J. (2000). Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1873–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P. M. , Bryson, C. L. , & Rumsfeld, J. S. (2009). Medication adherence: Its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation, 119, 3028–3035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, S. , Elliott, L. , & Comer, L. (2015). Available screening tools for adults suffering from bipolar affective disorder in primary care: An integrative literature review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27, 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. , Mulligan, L. D. , Law, H. , Dunn, G. , Welford, M. , Smith, G. , & Morrison, A. P. (2012). A randomised controlled trial of recovery focused CBT for individuals with early bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 204. doi:1471‐244X‐12‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd, L. L. , Akiskal, H. S. , Schettler, P. J. , Coryell, W. , Endicott, J. , Maser, J. D. , … Keller, M. B. (2003). A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long‐term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardas, P. , Lewek, P. , & Matyjaszczyk, M. (2013). Determinants of patient adherence: A review of systematic reviews. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 4, 91. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, T. , Douglas, L. , Denmark, L. , Brasuell, G. , & Lieberman, D. Z. (2013). The high prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea among patients with bipolar disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(1), 54–58. doi:S0165-0327(13)00426-6[pii];10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing, L. V. , Hellmund, G. , Geddes, J. R. , Goodwin, G. M. , & Andersen, P. K. (2011). Valproate v. lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder in clinical practice: Observational nationwide register‐based cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 57–63. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , Nelson, C. B. , McGonagle, K. A. , Edlund, M. J. , Frank, R. G. , & Leaf, P. J. (1996). The epidemiology of co‐occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66(1), 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , & Ustun, T. B. (2004). The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13, 93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketter, T. A. (2010). Diagnostic features, prevalence, and impact of bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71, e14. doi:10.4088/JCP.8125tx11c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, A. M. , Cornelius, J. R. , Han, X. , Pincus, H. A. , Shad, M. , Salloum, I. , … Haas, G. L. (2004). Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 6, 368–373. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, K. R. (2005). Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000151489.36347.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakso, L. J. (2012). Motivational interviewing: Addressing ambivalence to improve medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33, 8–14. doi:10.3109/01612840.2011.618238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage, M. J. , & Hassan, M. K. (2009). The relationship between antipsychotic medication adherence and patient outcomes among individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder: A retrospective study. Annals of General Psychiatry, 8, 7. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew, K. H. , Chang, E. Y. , Rajagopalan, K. , & Knoth, R. L. (2006). The effect of medication adherence on health care utilization in bipolar disorder. Managed Care Interface, 19, 41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebel, A. , Cucchiaro, J. , Silva, R. , Kroger, H. , Hsu, J. , Sarma, K. , & Sachs, G. (2014a). Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 160–168. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebel, A. , Cucchiaro, J. , Silva, R. , Kroger, H. , Sarma, K. , Xu, J. , & Calabrese, J. R. (2014b). Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 169–177. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning, J. S. (2010). Tools to improve differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder in primary care. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 12(Suppl 1), 17–22. doi:10.4088/PCC.9064su1c.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J. M. , Russell, J. M. , & Hirschfeld, R. M. (1998). Tolerability of oral loading of divalproex sodium in the treatment of mania. Depression and Anxiety, 7, 83–86. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520‐6394(1998)7:2<83::AID‐DA6>3.0.CO;2‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, J. S. , Ahn, J. , Tencer, T. , & Shi, L. (2007). The impact of unrecognized bipolar disorders among patients treated for depression with antidepressants in the fee‐for‐services California Medicaid (Medi‐Cal) program: A 6‐year retrospective analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 97(1–3), 171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, R. S. (2009). Understanding needs, interactions, treatment, and expectations among individuals affected by bipolar disorder or schizophrenia: The UNITE global survey. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(Suppl 3), 5–11. doi: 10.4088?JCP.7075su1c.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, K. , Koren, G. , Tetelbaum, M. , Wilton, L. , Shakir, S. , Diav‐Citrin, O. , … Einarson, A. (2005). Pregnancy outcome of women using atypical antipsychotic drugs: A prospective comparative study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas, K. R. , Akiskal, H. S. , Angst, J. , Greenberg, P. E. , Hirschfeld, R. M. , Petukhova, M. , & Kessler, R. C. (2007). Lifetime and 12‐month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. (2006). Bipolar disorder: Etiology, diagnosis, and management. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 18, 368–373. 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky, D. E. , Ang, A. , Krousel‐Wood, M. , & Ward, H. J. (2008). Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 10, 348–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) . (2006). Bipolar disorder: The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. Living with bipolar disorder: Interventions and lifestyle advice. British Psychological Society. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55353/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg, A. A. , Friedman, E. S. , Bowden, C. L. , Sylvia, L. G. , Thase, M. E. , Ketter, T. , … Calabrese, J. R. (2013). Lithium treatment moderate‐dose use study (LiTMUS) for bipolar disorder: A randomized comparative effectiveness trial of optimized personalized treatment with and without lithium. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 102–110. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.112060751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacchiarotti, I. , Bond, D. J. , Baldessarini, R. J. , Nolen, W. A. , Grunze, H. , Licht, R. W. , … Vieta, E. (2013). The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 1249–1262. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis, R. H. (2007). Treatment of bipolar disorder: The evolving role of atypical antipsychotics. American Journal of Managed Care, 13(7 Suppl), S178–S188. Retrieved from PM:18041879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, L. H. , & Heninger, G. R. (1994). Lithium in the treatment of mood disorders. New England Journal of Medicine, 331, 591–598. doi:10.1056/NEJM199409013310907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, A. L. , & Marzani‐Nissen, G. R. (2012). Bipolar disorders: A review. American Family Physician, 85, 483–493. doi:d10089. Retrieved from PM:22534227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascati, K. L. , Richards, K. M. , Ott, C. A. , Goddard, A. W. , Stafkey‐Mailey, D. , Alvir, J. , … Mychaskiw, M. (2011). Adherence, persistence of use, and costs associated with second‐generation antipsychotics for bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services, 62, 1032–1040. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.9.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinares, M. , Colom, F. , Sanchez‐Moreno, J. , Torrent, C. , Martinez‐Aran, A. , Comes, M. , … Vieta, E. (2008). Impact of caregiver group psychoeducation on the course and outcome of bipolar patients in remission: a randomized controlled trial. Bipolar Disorders, 10, 511–519. doi:10.1155/2013/548349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasdelli, A. , Lia, L. , Luciano, C. C. , Nespeca, C. , Berardi, D. , & Menchetti, M. (2013). Screening for bipolar disorder symptoms in depressed primary care attenders: comparison between Mood Disorder Questionnaire and Hypomania Checklist (HCL‐32). Psychiatry Journal, 2013, 548349. doi:10.1155/2013/548349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. , Colom, F. , & Vieta, E. (2007). A meta‐analysis of relapse rates with adjunctive psychological therapies compared to usual psychiatric treatment for bipolar disorders. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 10, 123–129. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706006900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidor, M. M. , & Macqueen, G. M. (2011). Antidepressants for the treatment of bipolar depression: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(2), 156–167. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05385gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. A. , Cornelius, V. , Warnock, A. , Tacchi, M. J. , & Taylor, D. (2007). bipolar mania: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of co‐therapy vs. monotherapy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 115, 12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soreca, I. , Levenson, J. , Lotz, M. , Frank, E. , & Kupfer, D. J. (2012). Sleep apnea risk and clinical correlates in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 14(6), 672–676. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sublette, M. E. , Carballo, J. J. , Moreno, C. , Galfalvy, H. C. , Brent, D. A. , Birmaher, B. , …Oquendo, M. A. (2009). Substance use disorders and suicide attempts in bipolar subtypes. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(3), 230–238. doi:S0022-3956(08)00114-3[pii];10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppes, T. , Datto, C. , Minkwitz, M. , Nordenhem, A. , Walker, C. , & Darko, D. (2010). Effectiveness of the extended release formulation of quetiapine as monotherapy for the treatment of bipolar depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 121(1–2), 106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum, W. O. (2006). Use of antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 6, 1077–1086. doi:10.1586/14737175.6.7.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase, M. E. , Macfadden, W. , Weisler, R. H. , Chang, W. , Paulsson, B. , Khan, A. , & Calabrese, J. R. (2006). Efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in bipolar I and II depression: A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study (the BOLDER II study). Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 26(6), 600–609. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000248603.76231.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Management of Bipolar Disorder Working Group . (2010). VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines for management of bipolar disorder in adults Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. [Google Scholar]

- Tohen, M. , Vieta, E. , Calabrese, J. , Ketter, T. A. , Sachs, G. , Bowden, C. , … Breier, A. (2003). Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine‐fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 1079–1088. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tondo, L. , Baldessarini, R. J. , Vazquez, G. , Lepri, B. , & Visioli, C. (2013). Clinical responses to antidepressants among 1036 acutely depressed patients with bipolar or unipolar major affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 127, 355–364. doi:10.1111/acps.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tondo, L. , Isacsson, G. , & Baldessarini, R. (2003). Suicidal behaviour in bipolar disorder: Risk and prevention. CNS Drugs, 17, 491–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente, S. M. , & Kennedy, B. L. (2010). End the bipolar tug‐of‐war. Nurse Practitioner, 35, 36–45. doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000367933.64526.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, G. , Tondo, L. , & Baldessarini, R. J. (2011). Comparison of antidepressant responses in patients with bipolar vs. unipolar depression: A meta‐analytic review. Pharmacopsychiatry, 44, 21–26. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1265198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta, E. , & Goikolea, J. M. (2005). Atypical antipsychotics: Newer options for mania and maintenance therapy. Bipolar Disorders, 7(Suppl 4), 21–33. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta, E. , Gunther, O. , Locklear, J. , Ekman, M. , Miltenburger, C. , Chatterton, M. L. , … Paulsson, B. (2011). Effectiveness of psychotropic medications in the maintenance phase of bipolar disorder: A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 14, 1029–1049. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta, E. , & Valenti, M. (2013). Pharmacological management of bipolar depression: treatment, maintenance, and prophylaxis. CNS Drugs, 27, 515–529. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0073-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisler, R. H. , Kalali, A. H. , & Ketter, T. A. (2004). A multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of extended‐release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for bipolar disorder patients with manic or mixed episodes. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65, 478–484. Retrieved from PM:15119909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisler, R. H. , Keck, P. E., Jr. , Swann, A. C. , Cutler, A. J. , Ketter, T. A. , & Kalali, A. H. (2005). Extended‐release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for mania in bipolar disorder: A multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatham, L. N. , Kennedy, S. H. , Parikh, S. V. , Schaffer, A. , Beaulieu, S. , Alda, M ., … Berk, M. (2013). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: Update 2013. Bipolar Disorders, 15, 1–44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeber, J. E. , Copeland, L. A. , Good, C. B. , Fine, M. J. , Bauer, M. S. , & Kilbourne, A. M. (2008). Therapeutic alliance perceptions and medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 107, 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnierek, K. B. , & Dimatteo, M. R. (2009). Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: A meta‐analysis. Medical Care, 47(8), 826–834. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]