Abstract

While considerable work has examined the association between social relationships and health, most of this research focuses on the relevance of social network composition and quality of dyadic ties. In this study, I consider how the social network structure of ties among older adults’ close family members may affect cardiovascular health in later life. Using data from 938 older adults that participated in Waves 1 and 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), I test whether older adults who occupy bridging positions among otherwise disconnected or poorly connected kin in their personal social network are more likely to present elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a biomarker for cardiovascular risk. Results indicate that occupying a bridging position among family members is significantly associated with elevated CRP. This effect is unique to bridging kin network members. These findings suggest that ties among one’s closest kin may generate important resources and norms that influence older adults’ health, such that bridging kin network members may compromise physical wellbeing. I discuss these results in the context of prior work on social support, family solidarity, and health in later life.

Keywords: social networks, bridging, cardiovascular risk, aging, family

INTRODUCTION

Heart disease is the leading cause of death among older Americans (National Center for Health Statistics 2015) and is responsible for over $100 billion in national health expenditures each year (Heidenreich et al. 2011). While aging and lifestyle habits such as smoking are known to put people at higher risk, research also suggests that social relationships profoundly influence cardiovascular health in later life. This is especially true with respect to older adults’ family relationships, which are closely linked to a variety of social processes that shape health outcomes (e.g., Rook 2015; Silverstein, Chen, and Heller 1996). To date, most work on this topic has explored how the quality of older adults' dyadic kin relationships influence risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Kiecolt-Glaser, Gouin, and Hantsoo 2010; Rook 2015), emphasizing the protective effects of positive kin relationships and the adverse effects of ambivalent or negative family ties (e.g., Liu and Waite 2014; Uchino et al. 2015).

Considerable research also suggests that the structure of one's personal network influences health in important ways (Berkman et al. 2000; Valente 2010). Network structure generally describes one's connections to others in the social environment, including network size, composition, frequency of interaction, and closeness with network members, as well as the connections that exist among network members (Seeman and Berman 1988; Burt 1992; Cornwell et al. 2009). While prior work has considered how some aspects of network structure influence health (e.g., Berkman et al. 2000), little attention has been given to whether and how the ties that exist among one's network members inform older adults’ CVD risk. Theoretical and empirical work on social networks suggests that this structural characteristic may be important, as a network's influence on an individual stems not only from one's direct ties to network members, but also from the connections that exist between network members (Coleman 1988; Milardo 1988; Simmel 1950).

Indeed, theory on kin networks proposes that the range of social resources that stem from family ties may be most effectively studied by looking beyond dyadic relationships. Kin dyads are necessarily embedded in broader family structures, characterized by particular family histories and life course events. Such interdependencies can ultimately shape the configuration of family ties and the various supports, strains, and caretaking arrangements that aging adults experience (Van Gaalen, Dykstra, and Flap 2008; Widmer 2010). Unlike kin, non-kin network members are not intertwined within a broader family system. Although non-kin ties— especially friendships — are key sources of companionship and socialization, these relationships are often disconnected from the kinship system, are not embedded in the set of normative obligations and social resources that emanate from family interconnectivity (Huxhold, Miche, and Schüz 2014; Wellman 1990; Widmer 2010).

Bridging is one measure of social network structure that refers to a lack of connectivity among network members. Generally speaking, a focal individual (i.e., ego) occupies a bridging position when two network members (i.e., alters) have direct ties to ego, but are not directly connected to each other (Burt 1992; 2000). In this paper, I consider the possibility that bridging kin in particular may be associated with cardiovascular risk in later life. Prior research indicates that social support, strain, and regulation are key mechanisms linking social relationships to the physiological processes associated with CVD risk (Graham, Christian, and Kiecolt-Glaser 2007; House, Umberson, and Landis 1988; Uchino 2006). I argue that bridging kin alters may influence CVD risk through its associations with each of these social mechanisms known to impact the biological pathways associated with CVD.

Occupying a bridging position may undermine ego's access to stress-buffering social supports and coordinated care that would otherwise emerge from, or be facilitated by, the ties between their closest kin. Bridging kin may also reflect conflictive social relations, complex family histories, or poorly functioning or otherwise burdensome caregiving networks, contributing to older adults' social strain, and requiring that they spend discrete periods of time with close relatives to maintain their personal networks (Burt 2000; Feld 1981; Wellman 1990). For older adults especially, bridging kin may reflect declines in intergenerational solidarity, and contrasting with expectations around close-knit, dense family structures and normative caretaking obligations (Bengtson 2001; Widmer and La Farga 1999).

Using nationally representative longitudinal data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NHSAP), I examine whether occupying a bridging position among kin network members is associated with elevated cardiovascular risk among older adults. I also consider whether CVD risk is associated with bridging any network alters, or whether this health outcome pertains specifically to bridging kin alters.

BACKGROUND

Physiological Links between Social Relationships and Cardiovascular Health

The cardiovascular system is a main physiological pathway linking social relationships and physical health (Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2010; Uchino 2006). The mechanisms accounting for this association are often theorized within the context of three areas of social relationships: social support, social strain, and social regulation (Graham et al. 2007; House et al. 1988).

Broadly speaking, social support refers to the emotional care, and instrumental and practical aids that come from social ties and that benefit individuals' mental and physical health (House et al. 1988). Strong evidence in support of the stress-buffering hypothesis suggests that social support protects against CVD, in part through protecting individuals from the potentially deleterious physiological effects (e.g., higher blood pressure, weaker immune regulation) of stressful life events that can contribute to poorer cardiovascular health (Cohen and Willis 1985; Uchino 2006). Indeed, these social supports provide key coping resources for older adults experiencing life strains. Likewise, social strain emanating from demanding social ties, or ambivalent or negative social exchanges, is linked to compromised immune functioning and cardiovascular reactivity (e.g., changes in heart rate or blood pressure) among older adults (Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2010). Interpersonal stressors that lead to poorer mental health are considered to be a primary means by which social relationships adversely influence physical health (Thoits 2011). Social control or regulation refers to the capacity of others in one's social environment to communicate with one another and influence the health or behaviors of a given individual (House et al. 1988; Umberson 1987, 1992). Social ties that coordinate to collectively enhance an individual's health promoting behaviors, or provide care to an aging family member, can ultimately impact those individual behaviors or management of chronic health conditions that influence cardiovascular health.

As these theories propose multiple mechanisms linking social relationships to CVD risk, there is considerable interest among scholars as to how social network factors relate to cardiovascular health. Some work in this area has focused, understandably, on the closest social ties that older adults maintain. Non-kin ties are associated with some cardiovascular health benefits, including lower depressive symptomatology and better mental health (Fiori, Antonucci, and Cortina 2006). Nevertheless, non-kin network members are more likely to be disconnected from the kinship network, offering limited types of social supports and having less capacity for collective regulation than kin ties (Huxhold et al. 2014; Wellman 1990). Indeed, kin relationships can have an especially pronounced effect on physical health, underscoring the importance of family relations in studying the physiological mechanisms linking social relationships and CVD (Yang, Schorpp, and Harris 2014).

Kin Network Structure and Cardiovascular Risk

Certain aspects of family network structure may influence older adults' health in ways that can shape cardiovascular health. More so than friendships, a larger number of supportive family members is associated with lower CVD risk and better psychological health (Uchino et al. 2015). Among older adults especially, intergenerational solidarity theory suggests that positive kin ties contribute to healthful aging, including decreased mortality among older parents (Silverstein and Bengtson 1991). Applications of this research paradigm often use a dyadic framework, emphasizing frequent contact, reciprocal support exchange, and normative obligations within the parent-child bond, and their implications for older adults’ psychological well-being and stress (e.g., Silverstein et al. 1996; Marks, Lambert, and Choi 2002). Likewise, extensive work on the conjugal bond generally finds that older adults’ cardiovascular health is strongly associated with marital quality, perhaps more so for women than men (see Robles et al. 2014 for review). While positive marital quality may protect against cardiovascular reactivity, the stress and emotional burdens of spousal caregiving in later life may significantly increase older adults’ psychological distress (Galinsky and Waite 2014; Liu and Waite 2014). Despite this evidence, little work has considered how the broader configuration of kin ties within one's social network may influence the social determinants of CVD risk. That is, little attention has been paid to the health implications of how one’s family members are connected to each other.

With respect to network structure, I focus in particular on the issue of bridging. An individual (i.e., ego) occupies a bridging position when they have direct social connections to at least two individuals (i.e., alters) who are not directly connected to one another (Burt 2005). Importantly, whereas bridging refers to the absence of ties among alters, social closure refers to the presence of ties or connections among alters and the social resources that inhere in those ties (Burt 2000; Coleman 1988). Various strands of social network theory propose that the implications of bridging positions and social closure may depend on the particular context of interest. For instance, bridging has been discussed extensively in terms of potential social and economic benefits, including strategically playing two network members against one another, controlling the flow of resources between otherwise disconnected network members, and accessing information from diverse social domains that social closure may otherwise preclude (Burt 2000; Feld 1981; Gould and Fernandez 1989).

Still, other work suggests that social network bridging may be risky, particularly as it relates to health and wellbeing. Certain social resources that benefit individual health may depend on there being social closure among one's closest network members (Coleman 1988). For instance, older adults who bridge members of their social networks are more likely to experience abuse or mistreatment than those with more social closure among network alters (Schafer and Koltai 2015). In this circumstance, a bridging position may compromise alters' capacity to share information and coordinate protection ego against stressful or harmful events. More generally, individuals who are embedded in networks with greater connectivity benefit from more relationships based on trust and reciprocal obligation, which is particularly important for exchanging social support, enforcing social control, and monitoring network members’ behaviors (Coleman 1988; Cornwell 2009).

To this end, there are several reasons why bridging kin in particular may be associated with elevated CVD risk, given its correlates with many of the mechanisms that link social relationships to cardiovascular disease.

Social support

Among older adults' especially, social networks are largely kin-based (Cornwell, Laumann, and Schumm 2008), and are typically characterized by more instrumental and emotional support exchange than non-kin ties (Grundy and Henretta 2006). These supports are most accessible when kin alters are connected to one another (Hurlbert, Haines, and Beggs 2000). For instance, with regard to instrumental supports, kin close to an older adult often coordinate and consult with one another around the responsibilities of caring for an aging family member (Wellman 1990). Coordinated care among kin may more effectively monitor and manage older adults' chronic conditions than a dyadic relationship with a given network alter, reducing the caregiving burden of a single individual (Ingersoll-Dayton et al. 2003). Likewise, kin networks with more social closure are more likely to serve as consistent sources of high emotional support, with "several persons collaborating" toward such support provision (Widmer 2010: 46).

Research on demographic trends in family configuration serves to illustrate this point. Bridging kin may reflect complex family histories including divorce and remarriage that result in ego being the sole individual connecting members of multiple family systems who are unlikely to otherwise have ties with one another. As divorce is associated with the disruption or weakening of family ties, divorced older adults are limited in their ability to draw on intergenerational supports and are more likely to experience intergenerational estrangement (Dykstra 1997). Likewise, greater geographic dispersion of family may make it more likely that older adults bridge kin whose contact with one another is otherwise infrequent or nonexistent given their physical distance, which challenges reciprocal support exchange within the kin network and the capacity of kin to coordinate care (Bengtson 2001; Dykstra and Fokkema 2010; Hank 2007; Van Gaalen et al. 2008). In these ways, occupying a bridging position among kin may indicate compromised access to those emotional and practical social supports that, consistent with the stress-buffering hypothesis, are important means of protecting older adults' cardiovascular health from the psychological and physiological impact of stressful life events and chronic social strains. As many chronic conditions common among the elderly feature inflammation (Sarkar and Fisher 2006), the potential for interconnected kin to efficiently influence disease management may have direct implications for CVD risk.

Social regulation

Bridging one's closest kin may also undermine access to important health benefits that stem from an interconnected family structure. Consistent with social control theory, connectivity among kin alters provides opportunities for alters to communicate with one another around ego’s health, and collectively influence ego’s adoption or deterrence of certain behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity) that may impact cardiovascular health (Umberson 1987; 1992). Although some health habits may be reinforced or deterred through influential dyadic ties, the key argument here is that the ties among one's closest kin offer the potential for coordinated efforts and collective pressures that may more purposefully and effectively influence ego's health-related behaviors (Berkman et al. 2000; Cornwell 2009). Indeed, some studies suggest that greater connectivity among network alters may be particularly consequential for normative reinforcement of health behaviors such as smoking cessation, even more so than dyadic ties (e.g., Christakis and Fowler 2008; Valente 2010). Bridging kin may therefore attenuate kin’s capacity to collectively monitor and influence individual wellbeing (Cornwell 2009; Schafer and Koltai 2015). When network members are connected to one another, they are better able enforce social norms and/or sanction deviations from certain health behaviors (Coleman 1988).

Social strain

Finally, bridging can indicate dissonant social relations and/or a lack of embeddedness in cohesive social groups (Bearman and Moody 2004), contributing to stress and social strain. According to structural balance theory, the absence of ties between one’s closest social network members may induce psychological distress for ego. Individuals generally prefer that their close social relations also have ties with one another, as this type of transitive or closed network structure generates feelings of liking and positivity within the network (Davis 1963). In the case of family, poorly connected kin may reflect conflict or estrangement among family members, contrasting with general desires for positivity among network alters, as well as normative obligations around family connectivity. Relatedly, stress may also result from felt pressures to mediate kin in conflict with one another (Sorkin and Rook 2004; Agllias 2011).

Social strain may also be a consequence of broader family processes that are antecedents of bridging kin positions. Poorer cardiovascular health may emanate in part from the stress associated with circumstances surrounding family reconfiguration such as divorce, remarriage, and widowhood that may be reflected by bridging kin positions (Mineau, Smith, and Bean 2002). Additionally, bridging kin may reflect poorly functioning caregiving patterns that extend beyond traditional dyadic interactions. This network circumstance may cause strain for an individual who provides care within a family system, or assumes responsibility around coordinating family members who collectively provide care. Indeed, shared responsibilities within well-functioning, informal caregiving networks are important aspects of kin relationships that lower the burden and stress of individual caregivers and provide more effective care, but that also require connectivity among members of the network (Tolkacheva et al. 2010). For each of these reasons, bridging kin may impact CVD risk by contributing to levels of interpersonal strain that are more generally associated with cardiovascular reactivity (Chiang et al. 2012; Fuligni et al. 2009).

Hypothesis 1: Occupying a bridging position among kin will be associated with increased CVD risk, given its correlates with the social processes (social support, social regulation, social strain) that influence the physiological processes linking social relationships and cardiovascular health.

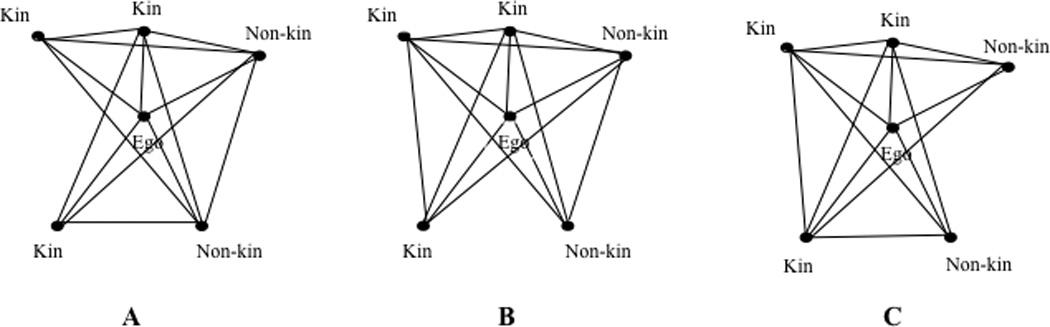

Figure 1 illustrates three possible types of bridging in the context of kin and non-kin alters. Diagram A illustrates an individual (ego) who bridges kin. Diagram B illustrates an individual who bridges a kin and non-kin pair, and diagram C shows a bridging position among a pair of non-kin alters. Individuals' personal networks can include any combination of these three scenarios, or have no bridging potential at all (i.e., complete social closure). My primary argument is that the network structure represented in Diagram A (bridging kin) may be uniquely associated with elevated CVD risk, as non-kin ties are less embedded in the norms and support systems that characterize the broader family system.

Hypothesis 2: An association between bridging network alters and CVD risk will be specific to bridging kin network alters.

Figure 1.

Three Hypothetical Respondent Networks Demonstrating Variations in Bridging Status Among Kin and Non-Kin Network Members.

Note: In each diagram, “Ego” refers to the respondent. Black lines between network members (black circles) indicate that the network members are socially connected.

Prior research also reveals gender differences in how kin networks are experienced and maintained. Women tend to report greater emotional closeness and interaction with kin than do men, even following divorce, have a higher proportion of kin network alters (Gerstel 1988; Laditka and Laditka 2001), and more often assume roles around organizing family gatherings among both their own and their partner’s sides of the family (Widmer 2010). As families are inherently comprised of formal roles (e.g., spouse, sibling) that carry expectations around relations to other family members, psychological distress may occur when a role domain is strained or conflicted (Thoits 1995). Indeed, women also experience greater psychological distress than men when perceiving kin relationships to be strained (Gerstel and Gallagher 1993). Physiological disease pathways associated with social strain may be activated by engaging with social network members in a way that fails to reinforce or define meaningful social roles, particularly those roles that provide a sense of value and attachment (Berkman et al. 2000). In this way, an association between bridging kin and cardiovascular risk may differ by gender.

Hypothesis 3: Women who occupy bridging positions among kin will be more likely to exhibit elevated CRP than men, due in part to the greater stress that results from having poorly connected kin network members.

The Present Study

The primary motivation for this study is the idea that significant resources and social norms that influence older adults' health may depend on there being ties among kin network members, apart from the quality and resources available through one's direct, dyadic relationships. Hence, I test the possibility that bridging otherwise disconnected or poorly connected kin network members may contribute to CVD risk by undermining older adults' access to important stress buffers and social regulation, and contributing to social strain. I also examine whether any association between bridging and CVD risk is specific to kin alters, or be related to bridging any network alters (kin or non-kin).

As an indicator of CVD risk, I focus on C-reactive protein (CRP) - a widely used biomarker for CVD, inflammation, and mortality in the research and clinical contexts (Pearson et al. 2003). CRP is both an independent predictor of CVD, as well as a diagnostic measure of cardiovascular burden (Bozkurt, Mann, and Deswal 2010), and has been used to suggest linkages between CVD and social relationships (Ford, Loucks, and Berkman 2006; Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2010).

It is important to emphasize that prior work has considered how other characteristics of network structure and quality may shape CVD risk, and it is possible that some of these measures attenuate any relationship between bridging and CRP levels. For instance, larger networks may provide individuals with greater social integration and alternative sources of social support (Berkman and Syme 1979), thereby lowering CVD risk. More kin-based personal networks may reflect a close-knit family structure (Haines and Hurlbert 1992), potentially increasing health benefits from more coordinated family support. Emotional closeness with alters may indicate stronger interpersonal attachment and greater access to social support (Graham et al. 2007; Haines and Hurlbert 1992; Thoits 2011), while frequent interaction may provide more opportunities for support exchange and monitoring of health behaviors (York Cornwell and Waite 2012). A key goal of this study, therefore, is to test whether bridging may be associated with CVD risk independently of other social network measures studied by prior research.

DATA AND ANALYSIS

The NSHAP

To investigate this research question, I use data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), collected in 2005–2006 and 2010–2011, respectively, from a nationally representative sample of older adults. The NSHAP is an in-depth survey of older adults' social relations and health, collecting information on respondents' social networks, marriages, social engagement, medication use, health history, and sexuality, as well as physical, psychological, and cognitive wellbeing. A number of physiological, biomeasure, and anthropomorphic measures were also collected, allowing for a comprehensive study of how close social relationships and health are associated within the older population (Suzman 2009).

Wave 1 included 3,005 community-dwelling Americans ages 57–85 (born between 1920 and 1947) at the time of data collection. The NSHAP uses a multi-stage, national area probability design balanced for age and gender subgroups, and oversampling African Americans and Hispanics. Eligible individuals were selected from households screened by the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) in 2004, which provided the NSHAP sample for Wave 1. The response rate was 75.5%. Of those surviving and age-eligible Wave 1 respondents, 2,548 (89%) also participated in Wave 2. Surveys were conducted by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC), and included in-home interviews and biomeasure collection, followed by leave-behind questionnaires that respondents were asked to return by mail to the NORC.

The NSHAP is an ideal dataset for exploring the relationship between social network bridging and CRP as an indicator of CVD risk. The NSHAP is one of the only nationally representative datasets of older adults that collects both social network data and biomeasures. Bridging kin may be particularly stressful for older adults given their reliance on family for social support. Because the NSHAP elicits detailed information on the nature of respondents' relationships to their social network members, I can explore whether any association between bridging positions and CRP levels is unique to kin relations, or if it is instead reflective of stress or compromised social support that may be associated with the phenomenon of bridging in general. Finally, the longitudinal nature of the NSHAP is advantageous in reducing endogeneity bias, as it is plausible that older adults in poorer health are less physically capable of maintaining connectivity among family members, such as organizing family events that bring together otherwise poorly connected kin.

C-Reactive Protein

The outcome of interest in these analyses is whether respondents present elevated CRP levels at Wave 2 as an indicator of cardiovascular risk. Although the NSHAP collects several biomarkers, including blood pressure and heart rate, CRP is one of the most reliable markers for systematically identifying cardiovascular risk (Willerson and Ridker 2004), beyond many traditional risk indicators such as hypertension and cholesterol (Cushman et al. 2005).

A random five-sixths of Wave 1 participants (2,494) were asked to provide a blood sample as part of the in-home interview, which was later used to obtain CRP measurements. About 82% of this sample was willing and able to provide blood samples. Those respondents who agreed to provide samples did not differ significantly from those who disagreed with regard to age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, partner status, income, self-reported physical or mental health, and number doctor visits in the prior year (Nallanathan et al. 2008). Of the 2,032 samples made available for analysis at Wave 1 (McDade, Lindau, and Wroblewski 2011), 1,468 (72.2%) also provided a sample at Wave 2. Among these respondents, 85 provided samples that were insufficient for laboratory analysis at either wave (primarily due to an insufficient volume of blood). An additional 173 participants are excluded from the present analysis due to presenting CRP measures greater than 10.0 mg/L at either wave. Concentrations this high signify an acute inflammatory infection, and are not reliable measures for assessing the effects of chronic low-grade inflammation reflective of CVD risk, or for comparing CRP levels across waves (Pearson et al. 2003). This results in 1,210 participants who provided analyzable samples at both waves.

Prior work establishes that CRP concentrations greater than 3.0 mg/L are clinically meaningfully elevated levels, indicating the presence of chronic low-grade inflammation that is associated with increased CVD risk (Pearson et al. 2003). Researchers recommend interpreting CVD risk by classifying CRP measures as low or normal (≤3.0 mg/L) or as high (>3.0 mg/L) (Pearson et al. 2003). This criteria is used in the clinical setting to make medical treatment decisions, and represents a meaningful cut point for inferring individual immune dysregulation and mortality risk. Following this recommendation, I generate a dichotomous indicator of whether a respondent presents elevated CRP levels at each wave based on whether their CRP concentrations are above the 3.0 mg/L benchmark (see Liu and Waite 2014; Yang et al. 2014 for other examples of this application).

Social Network Structure and Kin Ties

As part of the in-home interview, the NSHAP asked respondents to respond to a conventional name generator that is designed to gather information about individuals’ core social support networks (Bailey and Marsden 1999; Marsden 1987). Specifically, respondents were asked to name individuals with whom they had discussed "important matters" in the prior year. Respondents could name up to five people who were recorded in Roster A, and described the nature of their relationship to each alter (e.g., child, friend, neighbor), the closeness of their relationship, and their frequency of contact. Respondents were then asked if s/he had a spouse/partner if one was not named in Roster A. If so, the spouse/partner was recorded in Roster B. Respondents were then asked if there was any other person with whom they are especially close. If so, this person was added in Roster C. Respondents also reported how often each network member (including the spouse/partner) talks with every other network member.

To classify the types of alter pairs that respondents bridge, I combine data on alters’ relationships to ego (i.e., kin or non-kin) and the reported frequency of interaction among all network members. I consider any alter as kin that is related to the respondent by birth or marriage. Using NSHAP-provided relationship categories, this includes any alter that respondents describe as a spouse, parent, in-law, child, step-child, brother, sister, or other relative. I classify all other alters as non-kin. My primary measure of bridging uses a dichotomous indicator of whether the respondent reports that at least one pair of network members of a given type (kin or non-kin) were totally unconnected or only poorly connected to each other (i.e., they interact once a year or less often).

My main interest is in examining whether occupying bridging positions among kin is a structural feature of social networks that is uniquely associated with elevated CRP. Because the opportunity to bridge family members depends on having at least two kin network members, I restrict the analyses to those respondents who provided information on at least two kin alters. I address issues related to potential selection bias based on this restriction below.

Covariates

I control for basic sociodemographic characteristics at Wave 1, including age (divided by 10 to make the coefficient more meaningful), race (white, African American, or other race), gender, ethnicity (Hispanic versus non-Hispanic), partner status (married/partnered versus single/never married, widowed, or divorced), and educational attainment (less than high school versus high school, some college, and bachelor’s degree or higher).

Smoking, obesity, and depression each contribute to elevated CRP, as does having chronic conditions with some inflammatory component (King et al. 2003, 2004). Likewise, depression and chronic health conditions – many of which are correlates of smoking and obesity - may limit one’s ability to maintain a tight-knit family structure, compromising how effectively one can organize family gatherings or otherwise maintain contact among kin. I include a dichotomous indicator of whether respondents reported being a smoker at Wave 1 (1 = yes). I determine obesity status using the NSHAP measures of body mass index (BMI), considering anyone with a BMI of 30 or higher as obese in accordance with Centers for Disease Control (CDC) BMI interpretation guidelines. (BMI is calculated as an individual's weight in kilograms divided by the square of his or her height in meters. Weight and height are among the anthropomorphic measurements collected as part of the NSHAP in-home interviews). Depression is measured by averaging respondents’ standardized responses to a modified version (11 items) of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D) (α = .80), asking participants to rate how often they experience symptoms such as “having trouble getting going.” The NSHAP also asks respondents whether they have ever been diagnosed with each of seventeen conditions, most of which are chronic and lifestyle-related in nature (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, cancers), and which feature inflammation. I sum respondents’ affirmative responses to reflect their overall history of inflammatory conditions. I also include a count respondents’ total regular prescription and over-the-counter medications recorded by the interviewer and later classified according to the Multum drug typology (Qato et al. 2009). A greater number of regular medications could reflect poorer health and higher CRP, while some medications such as antidepressants and cholesterol treatments may have anti-inflammatory properties (e.g., Ansell et al. 2003; Miller, Maletic, and Raison 2009)

As discussed, other measures of social network structure may influence cardiovascular risk, bridging kin, and the relationship between these two variables. I control for network size as the sum of all network confidants (kin and non-kin) named by the respondent, as well as average frequency of interaction with and emotional closeness to alters at Wave 1. Emotional closeness is measured as the average of respondents' reports of how close they feel to each network member (1 = "not very close," 4 = "extremely close"). Likewise, frequency of interaction is the average of respondents' reports of how often they talk with each alter (1 = "less than once a year," 8 = "every day"). I also control for the proportion of kin in respondents' networks (number of kin alters divided by network size) at Wave 1. Finally, following evidence that support and quality of family relationships is associated with inflammation (Sbarra 2009; Yang et al. 2014), I create a scale of general questions about family support, including how often respondents feel that: (1) they can rely on family, and (2) they can trust family. Participants responded using a 1 to 3 scale (1 = "hardly ever (or never)," 2 = "some of the time," 3 = "often"). The Cronbach's α indicates moderate reliability (α = .67).

All controls use Wave 1 measures, allowing me to consider the relationship between bridging kin and elevated CRP net of baseline health status and social network features. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for all variables.

Table 1.

Descriptions, Weighted Means, and Standard Deviations of Key Variables (N = 938).a

| Proportion or Weighted Meana | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Elevated CRP W2 (1 = yes) | .31 | .46 |

| Elevated CRP W1 (1 = yes) | .20 | .40 |

| Bridging kin W1 (1 = yes) | .21 | .41 |

| Female W1 | .52 | .50 |

| Age (divided by 10) W1 | 6.77 | 0.73 |

| Race | ||

| White | .83 | .38 |

| African American | .10 | .30 |

| Other race | .07 | .26 |

| Hispanic | .10 | .30 |

| Partner status | ||

| Married | .72 | .45 |

| Separated/divorced | .09 | .29 |

| Widowed | .18 | .38 |

| Never married | .01 | .10 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | .16 | .37 |

| High school or equivalent | .27 | .44 |

| Some college | .34 | .47 |

| Bachelor’s or more | .24 | .43 |

| Chronic conditions (0–9) W1 | 2.26 | 1.54 |

| Currently smokes W1 | .12 | .32 |

| Obese W1 | .37 | .48 |

| Depressive Symptoms CES-D W1 (α = .80) (Range: −.60 −2.34) |

−0.05 | 0.54 |

| Medication count (0–20) | 5.17 | 3.82 |

| Network size (2–7) W1 | 4.41 | 1.42 |

| Average closeness to alters W1 (1–4) |

3.14 | 0.45 |

| Average frequency of interaction with alters W1 (1–8) |

6.77 | 0.73 |

| Proportion of kin in network W1 | .73 | .22 |

| Family relationship quality W1 (α = .67) (Range: 1–3) |

2.50 | 0.54 |

Estimates are weighted using NSHAP Wave 1 respondent level weights (adjusted for age and urbanicity, and attrition and selection at Wave 2). Estimates are calculated for all respondents who have non-missing data on key variables in the final model, and who have at least two kin network members.

Analytic Strategy

I first consider the prevalence of bridging kin and elevated CRP within the analytic sample, including the types of poorly connected kin pairs. I then use logistic regression analysis to generate a series of multivariate models predicting the probability of presenting elevated CRP. Given that the outcome of interest is dichotomous (i.e., whether or not a respondent has elevated CRP at Wave 2), logistic regression is an appropriate analytic strategy.

I first examine the relationship between bridging kin and CRP when controlling only for Wave 1 CRP. Next, I consider how this relationship changes when accounting for sociodemographics and health-related variables known to impact cardiovascular risk. A third model includes family and social network covariates (apart from health controls) that may influence respondents' likelihood of bridging kin or exhibiting elevated CRP associated poor family relationship quality. A final model includes all covariates together, examining the relationship between bridging kin and CRP levels when accounting for all baseline predictors. Additional analyses consider the relationship between the number of kin pairs one bridges as a predictor, as well as whether there is a multiplicative effect of gender and bridging kin in predicting CRP. I also compare the main results with additional models designed to test whether an association between poorly connected kin and elevated CRP is unique to kin alters, or whether it extends to other types of poorly connected network members.

Attrition and Selection

Because the possibility of bridging kin depends on having at least two kin alters (who may or may not be connected to one another), I include in the analysis only those respondents who name at least two kin alters in their personal networks at Wave 1. (Supplemental analyses that code respondents with 0 or 1 kin alters as "not bridging kin" are consistent with the results presented here.) The final models include the 938 respondents with non-missing data on all variables and at least two kin alters. Of the 1,210 respondents that provided analyzable and valid blood samples at both waves, 47 name zero kin in their Wave 1 network and 172 report one kin alter. Additional excluded respondents (N = 53) had missing data one or more covariates, the majority of whom did not report on family quality, which was collected as part of a leave-behind questionnaire. (These respondents do not significantly differ from those included in the models with regard to CRP levels at either wave or whether they bridge kin.)

It is possible that those respondents included in the analyses differ systematically from those who are missing data on one or more variables, who are excluded on the basis of naming fewer than two kin network members, or who did not participate in both waves. To account for this possibility, I follow the inverse probability weighting adjustment used in other NSHAP studies to correct for non-random attrition between waves and potential selection bias (e.g., Cornwell and Laumann 2015; Schafer and Koltai 2015; York Cornwell and Waite 2012). I first use a logit model to predict whether a baseline respondent is included in the final analytic sample, using a number of sociodemographic, health, and network-related covariates (including total network size and total kin network members (0–7)) as predictors. I then multiply the inverse of this predicted probability by the Wave 1 NSHAP person-level weights that adjust for age and urbanicity, and apply these weights to the regression models. The final weights attenuate selection bias by giving greater weight to those cases that are more likely to be excluded, and allowing the models to generate estimates that better approximate those that would be derived if all respondents were included in the final sample. All models also use the NSHAP sample clustering and stratification to account for the multistage, clustered survey design and selection at Wave 1.

FINDINGS

I begin by briefly describing the network structure and baseline health of the respondents who are included in the analytic sample. Approximately 21% of respondents occupy a bridging position between at least one pair of kin alters at Wave 1. On average, respondents name between four and five network members, and report interacting with network members relatively often (between once a week and several times a week). Respondents also tend report high emotional closeness with network alters (between "very" and "extremely" close), and the networks are largely kin based (73% kin alters, on average).

With regard to health, 20% of respondents present elevated CRP at Wave 1, compared to approximately 31% at Wave 2. Respondents report, on average, having had between two or three chronic conditions, few depressive symptoms, and take about five medications regularly. Only 12% report being smokers at Wave 1, and 37% have BMIs categorized as "obese."

Bridging Kin and CRP

Table 2 presents the frequency of bridging among various types of triads involving kin network members. The majority of disconnected or poorly connected pairs include a child of the respondent, with respondents most frequently bridging a child and a sibling.

Table 2.

Matrix Showing Frequency of Unconnected or Poorly Connected Kin by Alters' Relationship to Respondent (Unweighted).a

| Alter Relationship to Respondent |

Spouse | Child | Parent | Sibling | In-Law | Other Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse | -- | |||||

| Child | 1 (3) | 18 (25) | ||||

| Parent | 2 (2) | 5 (7) | 0 | |||

| Sibling | 16 (17) | 83 (146) | 0 | 4 (4) | ||

| In-Law | 5 (5) | 28 (48) | 2 (2) | 29 (42) | 9 (13) | |

| Other Relative | 8 (10) | 34 (57) | 0 | 16 (21) | 9 (10) | 7 (8) |

Frequencies are based on those respondents with non-missing data on all key variables and who are included in the final models presented in Table 3. Numbers outside parentheses represent the number of respondents that occupy bridging positions between at least one pair of the respective types of kin. Numbers in parentheses represent the total number of unconnected or poorly connected pairs of type in the final sample. (These numbers can be higher than those outside of the parentheses because some individuals report more than one disconnected pair of a given type in their network. For example, a spouse that does not speak with either of their two children would bridge two spouse-child pairs).

Table 3 presents the results of the logistic regression models. All estimates in this and subsequent tables are presented using marginal effects, avoiding issues in comparing log-odds and odds ratios across models, and making the results more substantively interpretable (Mood 2010). In this way, the coefficient of a given variable can be interpreted as the greater (or lesser) likelihood of having elevated CRP at Wave 2 when all other covariates in the model are held constant at their mean values. In the description that follows, I also report the odds ratios [OR] and corresponding standard errors [SE] to accompany interpretations of the marginal effects.

Table 3.

Marginal Effects of Logistic Regression Models Predicting W2 Elevated CRP (N = 938).a

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridging Kin W1b | .099* (.039) |

.111** (.040) |

.135*** (.038) |

.137*** (.039) |

| Age (divided by 10) W1 | −.013 (.033) |

.005 (.033) |

−.009 (.034) |

|

| Female | .086** (.033) |

.097** (.035) |

.099** (.032) |

|

| Race (ref=White) | ||||

| African American | .170** (.065) |

.172** (.065) |

.175** (.067) |

|

| Other | .113 (.100) |

.082 (.083) |

.101 (.092) |

|

| Partner status W1 (ref=Married/Partnered) |

||||

| Separated/Divorced | −.091† (.054) |

−.076 (.056) |

−.092† (.050) |

|

| Widowed | −.051 (.050) |

−.060 (.052) |

−.046 (.050) |

|

| Never married | .133 (.143) |

.100 (.138) |

.107 (.140) |

|

| Network size W1 | −.012 (.015) |

−.014 (.014) |

||

| Proportion of kin in network W1 |

−.023 (.086) |

−.050 (.085) |

||

| Family relationship quality W1 |

.022 (.048) |

.002 (.046) |

||

| Average closeness to alters (1–4) W1 |

−.099* (.050) |

−.109* (.048) |

||

| Average interaction with alters (1–8) W1 |

.057* (.023) |

.047* (.024) |

||

| Chronic conditions W1 | .018 (.013) |

.014 (.014) |

||

| Currently smokes W1 | −.039 (.069) |

−.028 (.067) |

||

| Obese W1 (1=yes) | .109* (.049) |

.110* (.046) |

||

| Depression W1 | −.075† (.044) |

−.091* (.044) |

||

| Medications W1 | .007 (.005) |

.008† (.005) |

||

| Elevated CRP W1 | .329*** (.060) |

.305*** (.047) |

.324*** (.054) |

.309*** (.046) |

| F(df) | 23.34***(2, 50) | 8.63***(18, 34) | 4.40***(18, 34) | 7.81***(23, 29) |

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<.10 (Two-tailed tests). Standard errors in parentheses.

Estimates are weighted using NSHAP Wave 1 respondent level weights (adjusted attrition and selection at Wave 2, age and urbanicity). All models are adjusted for multistage, clustered survey design and include controls for educational attainment and Hispanic ethnicity, which are not significant and is not show due to space constraints.

Applies only to respondents with at least two kin network members.

Model 1 presents the predicted probability of having elevated CRP levels at Wave 2 when controlling only for Wave 1 CRP and whether one bridges kin. Those who bridge kin are 9.9% more likely to present elevated CRP at Wave 2 than those who do not (p < .05) (OR = 1.60, SE = .31). Model 2 considers the association between bridging kin and elevated CRP when accounting for sociodemographic and health-related variables. Those who bridge kin are 11.1% more likely to present elevated CRP than those with social closure among kin confidants (p < .01) (OR = 1.71, SE = .35). Women and African Americans are significantly more likely to have elevated CRP, and these relationships remain statistically significant when additional controls are added in subsequent models. Greater depressive symptomatology is marginally associated with a lower likelihood of elevated CRP (p < .10) (OR = .70, SE = .14), while being obese is associated with elevated CRP (p < .05) (OR = 1.70, SE = .40). Individuals who are separated/divorced at Wave 1 are also marginally (9.1%) less likely to present elevated CRP than married respondents (p < .10) (OR = .62, SE = .19).

In Model 3, the inclusion of network-related covariates drives the emergence of a highly significant association between bridging kin and the probability of elevated CRP. This suppression effect is driven largely by frequency of contact with network members. Net of sociodemographic and network covariates, the likelihood of presenting elevated CRP is approximately 13.5% higher among those who bridge kin than among those who do not bridge kin (p < .001) (OR = 1.92, SE = .37). More frequent contact with alters is also associated with a higher probability of having elevated CRP (p < .05) (OR = 1.32, SE = .15), while greater average emotional closeness with network members is associated with lower likelihood of elevated CRP (p < .05) (OR = .62, SE = .15).

The full model (Model 4) demonstrates that the relationship between bridging kin and the probability of presenting elevated CRP remains statistically significant (p < .001) with the simultaneous inclusion of health and network-related covariates. Among those who bridge kin, the probability of presenting elevated CRP at Wave 2 is 13.7% higher than those who do not occupy this network position, holding all other variables at their mean values (OR = 1.948, SE = .38). Greater average closeness with alters remains predictive of a lower probability of presenting elevated CRP (p < .05) (OR = .59, SE = .14), while more frequent contact with network alters predicts a higher likelihood of this outcome (p < .05) (OR = 1.26, SE = .15). Respondents who are obese at Wave 1 are 11.0% more likely to present elevated CRP at Wave 2 compared to non-obese respondents (p < .05) (OR = 1.71, SE = .37) while depression is negatively associated with elevated CRP (p < .05) (OR = .64, SE = .13). Those who are separated/divorced at Wave 1 are also marginally (9.2%) less likely to present elevated CRP than those who are married (p < .05) (OR = .62, SE = .17). An increase in the number of medications is associated with a .8% increase in the probability of presenting elevated CRP (p < .10) (OR = 1.04, SE = .02).

Following these findings, I considered whether the probability of elevated CRP increases with the number of kin pairs that one bridges, truncating this measure at four or more disconnected or poorly connected kin pairs. As shown in Table 4, a one unit increase in the number of kin pairs that a respondent bridges is associated with a 4.4% increase in the probability of presenting elevated CRP at Wave 2 (p < .01) (OR = 1.28, SE = .12).

Table 4.

Marginal Effects of Regression Models Predicting W2 Elevated CRP Using Number of Disconnected or Poorly Connected Kin Pairs (N = 938).a

| Variables | (1) |

|---|---|

| Number of Kin Pairs R Bridges W1b | .044** (.017) |

| Age (divided by 10) W1 | −.007 (.029) |

| Female | .085** (.028) |

| Race (ref=White) | |

| African American | .147* (.058) |

| Other | .091 (.079) |

| Partner status W1 (ref=Married/Partnered) | |

| Separated/Divorced | −.078† (.045) |

| Widowed | −.037 (.045) |

| Never married | .110 (.116) |

| Network size W1 | −.012 (.012) |

| Proportion of kin in network W1 | −.047 (.070) |

| Family relationship quality W1 | .001 (.040) |

| Average closeness to alters (1–4) W1 | −.095* (.042) |

| Average interaction with alters (1–8) W1 | .038* (.020) |

| Chronic conditions W1 | .013 (.012) |

| Currently smokes W1 | −.024 (.059) |

| Obese W1 (1=yes) | .094* (.038) |

| Depression W1 | −.079* (.038) |

| Elevated CRP W1 | .265*** (.033) |

| F(df) | 7.49***(23, 29) |

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<.10 (Two-tailed tests). Standard errors in parentheses.

Estimates are weighted using NSHAP Wave 1 respondent level weights (adjusted for attrition and selection at Wave 2, age and urbanicity). All models are adjusted for multistage, clustered survey design and include controls for educational attainment and Hispanic ethnicity, which are not significant and not show due to space constraints.

Applies only to respondents with at least two kin network members.

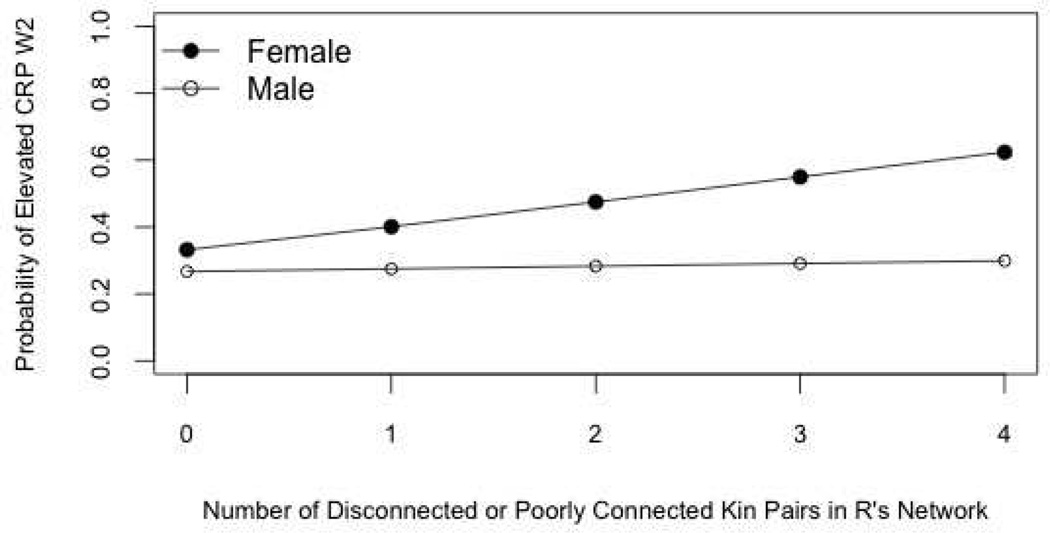

Gender Interaction

Additional models indicate that there is not a statistically significant multiplicative effect of gender and bridging at least one pair of kin alters. When using a continuous measure of bridging, however, and controlling for all covariates in Model 4 of Table 3, an interaction between bridging kin and gender is marginally significant (p < .10). This interaction is graphed in Figure 2. Among women bridging one pair of kin, the predicted probability of having elevated CRP at Wave 2 is roughly 14 percentage points higher than that of men. Among women bridging four pairs of kin, the predicted probability of having elevated CRP is nearly 33 percentage points higher than that of men. As few respondents bridge more than two kin pairs (20 men, 30 women), future work should test the robustness of this interaction with a larger sample of men and women that bridge multiple pairs of kin.

Figure 2.

Predicted Probability of Elevated CRP at Wave 2, by Gender.

Note: Predicted values are derived holding all other covariates in Table 4 at their mean values.

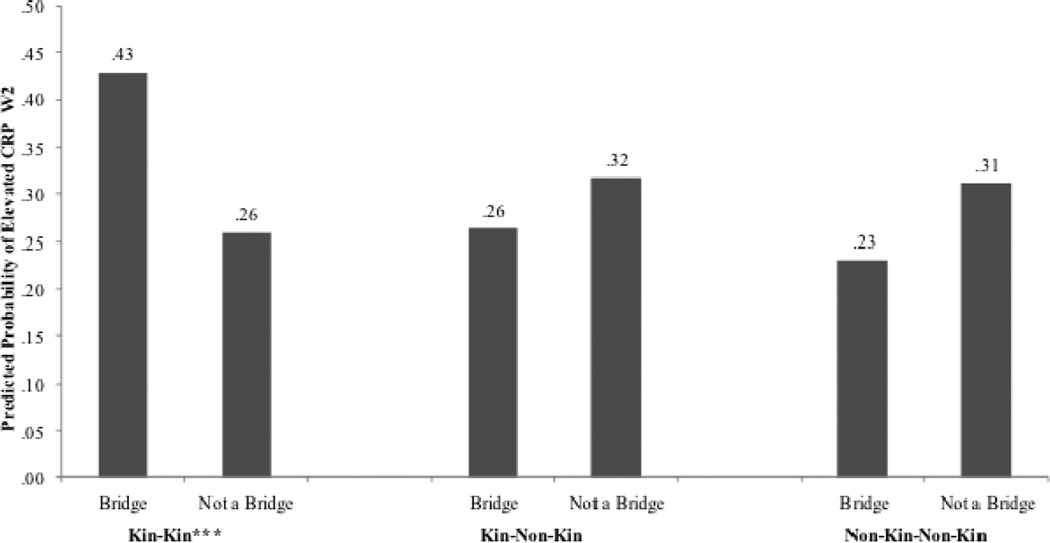

Comparisons by Bridging Type

Finally, I consider whether the relationship between poorly connected kin and elevated CRP levels is unique to bridging kin alters, or extends to bridging other types of alter pairs. Additional analyses use the covariates in the full model (Table 3, Model 4), substituting bridging kin status with two other dichotomous measures of network bridging, separately. The first model considers the effect of bridging at least one pair of kin and non-kin alters in predicting elevated CRP, while the second model examines the effect of bridging at least one pair of non-kin alters. In each scenario, the analytic sample and weights are adjusted accordingly based on the bridging circumstance of interest (i.e., only respondents with at least one kin alter and one non-kin alter are included in the first of these models, and only respondents with at least two non-kin alters are included in the second model).

Figure 3 summarizes these results, comparing the predicted probability of elevated CRP by bridging status (bridge versus not a bridge) and by the type of alter pair one bridges (i.e., kin and kin; kin and non-kin; non-kin and non-kin). For all three comparisons, predicted probabilities reflect the effect of bridging when holding all covariates in Model 4 at the mean values for all respondents with at least two network members, regardless of whether they are kin and/or non-kin. Full model results are available upon request.

Figure 3.

Marginal Effects of Bridging Status by Type of Alter Pair.

*** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05 (Two-tailed tests).

Note: For each type of alter pair (i.e., kin and kin, kin and non-kin, non-kin and non-kin), marginal effects reflect predicted probabilities of elevated CRP using three separate models (one model for each type of alter pair). Each model is weighted using NSHAP Wave 1 respondent level weights (adjusted for attrition and selection at Wave 2, age, and urbanicity), and is adjusted for multistage, clustered survey design. All covariates (Table 3, Model 4) are held at the mean values for all respondents with at least two network members (regardless of whether they are kin or non-kin), and who provide information on all other variables in the model. Categorical variables are held at their modal values.

The probability of presenting elevated CRP is approximately 65% greater for those who bridge kin relative to those who do not (p < .001). In the other two circumstances, the difference in predicted probabilities between bridges and non-bridges is not statistically significant. Bridging a pair of kin and non-kin alters, or a pair of non-kin alters, actually predicts lower probabilities of presenting elevated CRP than their non-bridging counterparts, which is the opposite pattern of what we find in the case of bridging a pair of kin alters.

DISCUSSION

Building on prior work examining the link between kin network structure and health, this study highlights the significance of connections among kin network members in informing older adults’ cardiovascular risk. Bridging kin at Wave 1- as a measure of poor or absent ties among one's closest sources of family support - is significantly associated with elevated CRP at Wave 2. More so for women than men, a greater number of poorly connected kin pairs is associated with a higher probability of elevated CRP.

Collectively, these findings suggest that the ties among one’s closest kin generate important resources and norms that influence older adults’ health. Bridging kin may undermine older adults' access to those social supports, coordinated social regulation, and caregiving that are strongly linked to interconnected kinship networks. Access to these social supports are particularly important for cardiovascular health, buffering the cardiovascular system from the adverse effects of various life stressors (Cohen and Willis 1985; Uchino 2006). Likewise, bridging kin may reflect ego’s caregiving burdens or family histories of reconfiguration (divorce and remarriage) that can contribute to individuals’ social strain. Even geographic dispersion of kin may increase the likelihood that an older adult serves as the sole tie between otherwise disconnected family members. Less proximity, particularly among older adults and their children, may reduce the opportunities for collective caregiving and reciprocal support exchange within the broader family system (Hank 2007). In these ways, elevated levels of CRP associated with bridging kin may reflect a number of the key social processes – namely, social support, social regulation, and social strain – known to impact the physiological pathways associated with CVD risk.

The finding that women's CVD risk may be more affected by bridging a greater number of kin pairs may reflect theoretical frameworks around gender roles in families. Specifically, the role of “kinkeeper,” more often assumed by women than men, relates directly to responsibilities of keeping family members in touch with one another (Gerstel and Gallagher 1993). Given the psychological distress associated with role strain (Thoits 1995), women may experience greater social strain than men (and, in turn, greater cardiovascular reactivity) as a result of bridging a greater number of kin pairs — a network structure that may challenge "kinkeeping" roles.

It is important to note that the association between bridging and elevated CRP is unique to bridging kin network members. Indeed, social network theory proposes that individuals' relationships are structured around social contexts, with bridging indicating fewer shared foci among disconnected alters (Feld 1981). Non-kin alters may not know one another, or have less of a reason to interact, especially if they represent distinct social domains for the individual. Bridging a pair of kin and non-kin alters, or a pair of non-kin alters, may therefore be more normative and less stress-inducing than bridging kin, explaining the lack of significant effect in these circumstances. As prior research suggests that bridging positions and non-kin alters may facilitate ego's exposure to non-redundant information, older adults may even benefit from novel health-related resources elicited through bridging positions that include a non-kin alter (Burt 2000; Schafer 2013).

Respondents also bridge a variety kin pairs (Table 2), spanning both the nuclear and extended family. While the NSHAP does not collect information on the context or circumstances that explain bridging positions, different theoretical frameworks may shed light on how bridging different kin pairs influence CVD risk. In extending intergenerational ambivalence theory beyond the parent-child dyad, it is possible that bridging one's nuclear family members may reflect a break with traditional or idealized norms around intergenerational relationships, causing social strain (Luescher and Pillemer 1998; Luscher 2002). Such ambivalence is thought to be particularly stressful for individuals occupying social roles that are incompatible with beliefs and expectations around how family relations should, ideally, be structured, and has been negatively associated with parental health (Pillemer et al. 2007). Ambivalence theory may be especially applicable to older adults who bridge children or a spouse and a child, for example, as the wellbeing of older adults may be partly a function of one’s investment in the ties among children and parents (Pezzin, Pollak, and Schone 2013).

In other instances, bridging kin might be less norm violating, as in the case of bridging in-laws and one's own nuclear family members whose relationship is engendered only by way of the respondent's marriage (Widmer 2006). Nevertheless, while some scholars have referred to the modern nuclear family as “isolated,” other research points to increasing reliance and persistent maintenance of the extended kin network as a significant source of social support and coordinated caregiving, particularly in a time of increasing complexity and diversity in family structures (Bengtson 2001; Swartz 2009). Likewise, according to family systems theory, the social supports available through key dyads such as the conjugal or parent-child relationship may be strengthened (or diminished) by the configuration of the more extended family system in which the dyad is embedded (Widmer 2010). The quality and social supports that characterize ego's dyadic ties with a given family member(s) can impact how ego copes with stress or strain emanating from a dyadic tie with another kin member (Cox and Paley 1997). When one’s closest kin are not connected to one another, kin alters may be less familiar with or embedded in ego’s dyadic family relationships, and less able to offer effective support to ego surrounding relationship strains emanating from other kin dyads.

Relatedly, it is worth noting that the majority of poorly connected kin pairs in this study include a respondent’s child and another relative, which in many cases is the respondent's sibling. A long line of literature on intergenerational solidarity focuses on the parent-child bonds as a key context for social support and normative filial obligation, which are highly consequential for aging parents' health and mortality (Pillemer et al. 2007; Silverstein and Bengtson 1994). The findings from this study suggest that ties among one's closest children and sibling(s) may also be a significant source of intergenerational kin support, beyond traditionally considered dyadic ties. When adult children do not assume the same ties with family as do their parents, and older adults may feel less accomplished in transferring norms around family solidarity across generational lines (Silverstein, Conroy, and Gans 2012). As extensive prior work establishes that siblings - as well as adult children - are significant sources of emotional and instrumental aide throughout the lifespan, often as life-long social network members (Cicirelli 2013), an older adult’s social support system may be also significantly less coordinated when the sibling and child are not tied to one another. Hence, this work may suggest other avenues for developing a more multidimensional, nuanced conceptualization of intergenerational family solidarity with implications for older adults' wellbeing (e.g., Dykstra and Fokkema 2010).

These results also extend prior work on the intersection of social networks and aging. Consistent with prior research, older adults’ health may benefit from larger networks and greater emotional closeness with alters, net of bridging kin, perhaps through the trust, support, and more general stress-buffering effects of social integration (Berkman et al. 2000). More unexpected is the finding that greater interaction with alters is positively associated with CRP, which also increases the significance of the relationship between bridging kin and CRP in the models. Indeed, foundational network theory proposes that when ties are high in time, energy, and emotion- like those typical of egocentric networks - bridging reduces the amount of time one can devote to interacting with each alter individually (Feld 1981). At the same time, higher interaction may reflect more demanding social ties. Consistent with recent work on caregiving networks, greater dyadic interaction may indicate that the respondent is a provider in a poorly functioning caregiving network, contributing to caregiver burden and social strain (Graham et al. 2007; Tolkacheva et al. 2010). Greater interaction could also indicate that the respondent is in poor health, necessitating the receipt of extensive support from alters (Uchino 2004).

Somewhat surprising is that married respondents at Wave 1 are more likely than those who are separated/divorced to present elevated CRP at Wave 2. This result may be explained by changes in partner status that occur between waves, such as divorce or widowhood, which are associated with declines in health (Mineau et al. 2002). (In supplemental models available upon request, the difference in predicted probability between married/partnered and divorced/separated respondents is no longer statistically significant after controlling for whether respondents become a widow or divorced/separated between waves.) Depression, too, is unexpectedly negatively associated with CRP. Other studies with similar findings suggest that depression is also associated with elevated levels of cortisol, which is known to have anti-inflammatory properties (Whooley et al. 2007). Though antidepressant use does not mediate the effect in this study, the anti-inflammatory properties of antidepressants may also have to do with the length and dosage of such treatment. This information, however, is not collected as part of the NSHAP.

A number of limitations should be considered. First, although the lagged modeling approach helps to reduce concerns about endogeneity, these findings can still be used only to consider a potentially causal relationship, rather than to draw more conclusive causal arguments. In addition to issues around unobserved heterogeneity, only a relatively small proportion of the analytic sample experience a change in bridging kin status between waves (25%). Further research using a sample with more within-person variation on this key predictor variable and additional waves of data may be better suited to assess causal claims. Indeed, although supplemental analyses (available upon request) indicate that the findings are robust to certain alternate modeling strategies (i.e., change scores as dependent variables, multinomial logit models, and cross- lagged models), the results are not robust to a fixed effects analysis.

Additionally, because the NSHAP only collects egocentric network data, I cannot consider family structures beyond personal network data, which may also have implications for respondents' access to social support and perceptions of family solidarity. Future work should also explore the implications of bridging kin on the health of younger and middle-aged adults. This relationship may manifest more prominently in later life when family cohesion and kin relations may be more significant determinants of social support and wellbeing. Future research may also investigate the extent to which the association between bridging kin and CRP can be attributed to certain pairs of disconnected kin (e.g., two children, a child and a sibling, etc.), and/or the contextual circumstances of bridging kin positions.

Despite these limitations, this work lends credence to the idea that connections among kin alters, in addition to dyadic network measures, should be explored in considering the health implications of social network structure and family relationships. These results add a structural nuance to other research establishing the importance of family relationships for healthful aging. This work is especially germane in light of demographic and geographic trends that may influence family structure. Divorce and remarriage often influence family configuration and reassembly. Likewise, while increased longevity allows for more shared years across generations (Bengtson 2001), greater geographic dispersion of family members may make kinship connectivity more difficult to sustain (Schmeeckle and Sprecher 2004). As these circumstances are likely to influence family dynamics, further understanding how kin network structure influences morbidity and mortality in later life is especially important.

Highlights.

Study examines social network bridging and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.

Older adults that bridge kin are ~65% more likely to present elevated CVD risk.

This association is unique to bridging kin network members.

Bridging kin may be linked to greater social strain and less social support.

This association may be more consequential for women than for men.

Acknowledgments

The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AG021487, R37AG030481, R01AG033903). The author thanks Benjamin Cornwell, Matthew Hall, Karl Pillemer, and Erin York Cornwell for their comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agllias Kylie. No Longer on Speaking Terms: The Losses Associated with Family Estrangement at the End of Life. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2011;92(1):107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell Benjamin J, et al. Inflammatory/antiinflammatory Properties of High-Density Lipoprotein Distinguish Patients from Control Subjects Better than High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels and Are Favorably Affected by Simvastatin Treatment. Circulation. 2003;108(22):2751–2756. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103624.14436.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey Stefanie, Marsden Peter V. Interpretation and Interview Context: Examining the General Social Survey Name Generator Using Cognitive Methods. Social Networks. 1999;21(3):287–309. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman Peter S, Moody James. Suicide and Friendships among American Adolescents. American journal of public health. 2004;94(1):89–95. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson Vern L. Beyond the Nuclear Family: The Increasing Importance of Multigenerational Bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman Lisa F, Glass Thomas, Brissette Ian, Seeman Teresa E. From Social Integration to Health: Durkheim in the New Millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51(6):843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman Lisa F, Syme S Leonard. Social Networks, Host-Resistance, and Mortality: A Nine-Year Follow-up Study of Alameda County Residents. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1979;109(2):186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt Biykem, Mann Douglas L, Deswal Anita. Biomarkers of Inflammation in Heart Failure. Heart failure reviews. 2010;15(4):331–341. doi: 10.1007/s10741-009-9140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt Ronald. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burt Ronald S. The Network Structure of Social Capital. Research in Organizational Behavior. 2000;22:345–423. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, Ronald S. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang Jessica J, Eisenberger Naomi I, Seeman Teresa E, Taylor Shelley E. Negative and Competitive Social Interactions Are Related to Heightened Proinflammatory Cytokine Activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(6):1878–1882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120972109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis Nicholas A, Fowler James H. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:2249e2258. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicirelli Victor. Sibling Relationships Across the Lifespan. Springer Publishers; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Sheldon, Willis Thomas A. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell Benjamin. Network Bridging Potential in Later Life: Life-Course Experiences and Social Network Position. Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21(1):129–154. doi: 10.1177/0898264308328649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell Benjamin, Laumann Edward O. The Health Benefits of Network Growth: New Evidence from a National Survey of Older Adults. Social science & medicine (1982) 2015;125:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell Benjamin, Laumann Edward O, Schumm Philip L. The Social Connectedness of Older Adults: A National Profile. American Sociological Review. 2008;73(2):185–203. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox Martha J, Paley Blair. Families as Systems. Annual review of psychology. 1997;48:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman Mary, et al. C-Reactive Protein and the 10-Year Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease in Older Men and Women: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2005;112(1):25–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis James A. Structural Balance, Mechanical Solidarity, and Interpersonal Relations. American Journal of Sociology. 1963;68(4):444–462. [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra Pearl A. The Effects of Divorce on Intergenerational Exchanges in Families. The Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences. 1997;33(2):77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra Pearl A, Fokkema Tineke. Relationships between Parents and Their Adult Children: A West European Typology of Late-Life Families. Ageing and Society. 2010;31(04):545–569. [Google Scholar]

- Feld Scott L. The Focused Organization of Social Ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1981;86(5):1015–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger Leon. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Antonucci TC, Cortina KS. Social Network Typologies and Mental Health Among Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series. B. Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61(1):P25–P32. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.p25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford Earl S, Loucks Eric B, Berkman Lisa F. Social Integration and Concentrations of C-Reactive Protein among US Adults. Annals of Epidemiology. 2006;16(2):78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni Andrew J, et al. A Preliminary Study of Daily Interpersonal Stress and C-Reactive Protein Levels among Adolescents from Latin American and European Backgrounds. Psychosomatic medicine. 2009;71(3):329–333. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181921b1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gaalen Ruben I, Dykstra Pearl A, Flap Henk. Intergenerational Contact beyond the Dyad: The Role of the Sibling Network. European Journal of Ageing. 2008;5(1):19–29. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky Adena M, Waite Linda J. Sexual Activity and Psychological Health as Mediators of the Relationship between Physical Health and Marital Quality. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2014;69(3):482–492. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel Naomi. Divorce and Kin Ties: The Importance of Gender. Journal of Marriage and Family1. 1988;50(1):209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel Naomi, Gallagher Sally K. Kinkeeping and Distress: Gender, Recipients of Care, and Work-Family Conflict. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1993;55(3):598–608. [Google Scholar]

- Gould Roger V, Fernandez Roberto M. Structures of Mediation: A Formal Approach to Brokerage in Transaction Networks. Sociological Methodology. 1989;19:89–126. [Google Scholar]

- Graham Jennifer E, Christian Lisa M, Kiecolt-Glaser Janice K. Close Relationships and Immunity. In: Robert Ader., editor. Psychoneuroimmunology. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Inc.; 2007. pp. 781–798. [Google Scholar]

- Grundy Emily, Henretta John C. Between Elderly Parents and Adult Children: A New Look at the Intergenerational Care Provided by the ‘sandwich Generation’. Ageing and Society. 2006;26(05):707. [Google Scholar]

- Haines VA, Hurlbert JS. Network Range and Heath. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour. 1992;33(3):254–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hank Karsten. Proximity and Contacts Between Older Parents and Their Children: A European Comparison. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(1):157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich Paul A, et al. Forecasting the Future of Cardiovascular Disease in the United States: A Policy Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(8):933–944. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House James S, Umberson Debra, Landis Karl R. Structures and Processes of Social Support. Annual Review of Sociology. 1988;14(1):293–318. [Google Scholar]