Abstract

Background. Recent studies suggest that statin use may reduce influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE), but laboratory-confirmed influenza was not assessed.

Methods. Patients ≥45 years old presenting with acute respiratory illness were prospectively enrolled during the 2004–2005 through 2014–2015 influenza seasons. Vaccination and statin use were extracted from electronic records. Respiratory samples were tested for influenza virus.

Results. The analysis included 3285 adults: 1217 statin nonusers (37%), 903 unvaccinated statin nonusers (27%), 847 vaccinated statin users (26%), and 318 unvaccinated statin users (10%). Statin use modified VE and the risk of influenza A(H3N2) virus infection (P = .002) but not 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus (A[H1N1]pdm09) or influenza B virus infection (P = .2 and .4, respectively). VE against influenza A(H3N2) was 45% (95% confidence interval [CI], 27%–59%) among statin nonusers and −21% (95% CI, −84% to 20%) among statin users. Vaccinated statin users had significant protection against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 (VE, 68%; 95% CI, 19%–87%) and influenza B (VE, 48%; 95% CI, 1%–73%). Statin use did not significantly modify VE when stratified by prior season vaccination. In validation analyses, the use of other cardiovascular medications did not modify influenza VE.

Conclusions. Statin use was associated with reduced VE against influenza A(H3N2) but not influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 or influenza B. Further research is needed to assess biologic plausibility and confirm these results.

Keywords: influenza, vaccine effectiveness, influenza vaccine, statin

Influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) varies from year to year and depends on numerous factors, including influenza virus type/subtype, age, prior vaccination or infection, and antigenic similarity between the reference vaccine strain and circulating viruses. Older adults have the highest risk of influenza complications and commonly take statins to reduce cholesterol and manage cardiovascular risk. Statins have well-documented antiinflammatory effects, and recently published reports have raised concerns that statin use may impair the antibody response to vaccination and reduce vaccine-induced protection. In a post hoc analysis of a clinical trial, the immune response to influenza vaccine was lower among persons receiving statin therapy, compared with those not receiving statin therapy [1]. Another study using administrative records found that statin therapy was associated with lower influenza VE against nonspecific respiratory illness, but laboratory-confirmed influenza was not assessed [2], which may conflate the influence of statins [3].

Since 2004–2005, Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation has conducted annual studies of influenza VE. Enrollment and statin use data from this VE study over 10 seasons were used to examine the impact of chronic statin use on influenza VE.

METHODS

Study Cohort and Enrollment

Enrollees of annual population-based studies of influenza VE conducted at Marshfield Clinic in Marshfield, Wisconsin, during the 2004–2005 through 2014–2015 seasons served as the study cohort. Details of study population and procedures have been previously described [4–9]. During each season, patients were recruited from outpatient primary and urgent care settings if they presented with acute respiratory illness with symptom onset ≤7 days previously (or <10 days previously before 2008). Specific symptom eligibility criteria varied by season, and a small proportion of enrollments occurred in the hospital setting before 2009. Nasopharyngeal or combined nasal and throat swabs were tested for influenza by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as previously described [4]. Culture alone was performed on samples collected in 2004–2005.

This analysis was restricted to persons aged ≥45 years enrolled ≤7 days after illness onset. For individuals with multiple enrollments in a season, either the first enrollment, if all samples were negative, or the first enrollment associated with a positive influenza virus test result was used. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of enrollment into the influenza VE study. The additional analysis for this study was subsequently approved by the IRB with a waiver of informed consent.

Vaccination History

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination dates were obtained from a validated immunization registry [10]. Subjects were considered vaccinated for influenza in the current season if they received that season's influenza vaccine ≥14 days prior to illness onset and as unvaccinated if they had not received the vaccine at the time of illness onset. Subjects were excluded if vaccination occurred <14 days prior to illness onset. Prior season influenza vaccination was determined on the basis of vaccination received 1 season prior (August–July).

Statin Use

Statin exposure was determined using a validated algorithm for extracting statin orders from the electronic health record [11, 12]. The algorithm screened for all available statin medications, including combination medications. Participants were classified as statin users or nonusers as of 1 September of their enrollment season. To control for temporary or ambiguous statin exposure, subjects were excluded if they initiated or stopped statin therapy during the enrollment season (September–March) or had a history of statin use within 2 years of enrollment but were not taking statins during their season of enrollment. Participants were classified as nonusers if they were not using statins during the enrollment season and had no evidence of statin use within the 2 years prior to the enrollment season.

Statin dose was standardized to atorvastatin equivalents and categorized by tertiles (low, medium, and high dose). Statins were further classified as nonsynthetic (simvastatin, pravastatin, and lovastatin) or synthetic (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, and rosuvastatin), based on manufacturing source.

Covariates

Information on comorbidities was extracted from the electronic medical record, using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes (list available on request). Covariates included chronic pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. In addition, we extracted height and weight for body mass index (BMI) calculation, cholesterol level (closest to the date of enrollment), and number of provider visits in the prior year. Information on age, sex, and smoking status was obtained from the study enrollment questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression models were used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for laboratory-confirmed medically attended influenza-associated illness, using the test-negative design, which generates a valid estimate of VE under most scenarios [13, 14]. Models included an interaction term for current season vaccination status and statin use. VE was estimated as [1 − aOR] × 100% among nonusers and statin users. aORs were also estimated for each combination of vaccine and statin exposure: vaccinated nonusers, vaccinated statin users, and unvaccinated statin users, with unvaccinated nonusers as the reference group. The following were included a priori in all adjusted models: age, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, prior pneumococcal vaccination, and season. Age was modeled using linear tail-restricted cubic spline functions with 5 knots based on percentiles. Potentially confounding variables were assessed and retained in the final model if the covariate resulted in a relative change of ≥10% in the OR for any of the vaccine-statin exposure categories. The following were assessed for inclusion in the final model: other high-risk conditions, BMI category, smoking status, time of enrollment within seasons, and number of provider visits in the past year.

Separate models were generated for influenza A(H3N2) virus, 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus (A[H1N1]pdm09), and influenza B virus. Patients infected with influenza A virus with no subtype were excluded. For each subtype analysis, individuals infected with a different subtype were excluded. To minimize random effects, only seasons with ≥25 cases identified for a given influenza virus subtype were included (2004–2005, 2007–2008, 2010–2011, 2011–2012, 2012–2013, and 2014–2015 for influenza A[H3N2]; 2013–2014 for influenza A[H1N1]pdm09; and 2007–2008, 2012–2013, and 2014–2015 for influenza B). The 2009–2010 season was excluded because monovalent vaccine was not available before the local pandemic wave. For influenza A(H3N2), a sensitivity analysis was performed that excluded the 2014–2015 season, which was dominated by the emergence of a new antigenic cluster with low VE [15]. Additional analyses were conducted to examine the effect of prior season influenza vaccination, statin product type (synthetic or nonsynthetic), and statin dose response.

We performed several validation analyses to better assess the specificity of statin use as a potential modifier of influenza VE. First, other common cardiovascular medications used to prevent cardiovascular events were examined. The same analytic procedures were used but included an interaction term for current season vaccination status and use of nonstatin medications, including β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and diuretics. For each of these drugs, we assumed no biologically plausible interaction with influenza virus or influenza vaccine response. We also assessed the combined and independent effects of statin use and pneumococcal vaccination on influenza, since pneumococcal vaccine is not expected to protect against influenza.

All analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

We enrolled 3597 adults aged ≥45 years during 10 seasons, and 3285 were included in the analysis (Figure 1). The most common reason for exclusion was use of statins during the previous 2 years without evidence of current statin use. Statin users were older, more likely to be male, had a higher prevalence of cardiovascular conditions or diabetes, and had more outpatient visits as compared to nonusers (Table 1). A higher proportion of statin users had received pneumococcal vaccine (ever) and current season influenza vaccine. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were lower in statin users versus nonusers. These differences were statistically significant. Simvastatin (by 44% of adults) and atorvastatin (by 27%) were the most commonly prescribed statins, followed by lovastatin (by 11%), pravastatin (by 10%), rosuvastatin (by 3%), and fluvastatin (by 1%).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of individuals enrolled from the 2004–2005 through 2014–2015 influenza seasons, excluding the 2009–2010 season.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients, by Influenza Vaccination and Statin Use Status

| Characteristic | Nonusers, No. (%) |

Statin Users, No. (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated (n = 903) | Vaccinated (n = 1217) | Unvaccinated (n = 318) | Vaccinated (n = 847) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 45–54 | 497 (55) | 447 (37) | 94 (30) | 140 (17) |

| 55–64 | 272 (30) | 305 (25) | 128 (40) | 224 (27) |

| 65–74 | 89 (10) | 254 (21) | 60 (19) | 265 (40) |

| ≥75 | 45 (5) | 211 (17) | 36 (11) | 218 (26) |

| Male sex | 344 (38) | 365 (30) | 153 (48) | 392 (46) |

| White | 875 (97) | 1166 (96) | 310 (97) | 822 (97) |

| Any high-risk condition | 329 (36) | 725 (60) | 205 (64) | 691 (82) |

| Cardiovascular | 113 (13) | 267 (22) | 107 (34) | 406 (48) |

| Diabetes | 41 (5) | 146 (12) | 79 (25) | 312 (37) |

| Pulmonary | 114 (13) | 298 (25) | 55 (17) | 213 (25) |

| Other | 182 (20) | 427 (35) | 110 (35) | 395 (47) |

| Obese (BMIa ≥ 40) | 92 (10) | 156 (13) | 47 (15) | 109 (13) |

| LDL cholesterol level > 130 mg/dL | 292 (32) | 288 (24) | 62 (20) | 74 (9) |

| HDL cholesterol level < 40 mg/dL (men) or <50 mg/dL (women) | 312 (35) | 398 (33) | 142 (45) | 349 (41) |

| Received pneumococcal vaccine | 161 (18) | 678 (58) | 147 (46) | 654 (77) |

| Received prior season influenza vaccine | 152 (17) | 1048 (86) | 92 (29) | 762 (90) |

| Provider visits in past year, no. | ||||

| ≤5 | 512 (57) | 413 (34) | 136 (43) | 190 (22) |

| 6–20 | 339 (38) | 626 (51) | 153 (48) | 487 (58) |

| >20 | 52 (6) | 178 (15) | 29 (9) | 170 (20) |

Abbreviations: HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

a Body mass index (BMI) is calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the height in square meters.

There were 915 subjects with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza: 523 (54%) had influenza A(H3N2) infection, 170 (17%) had influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 infection, and 222 (23%) had influenza B infection. Characteristics of patients with influenza as compared to those who tested negative are shown in Table 2. Cases and test-negative controls differed significantly in the prevalence of cardiovascular and chronic pulmonary disease, receipt of prior pneumococcal vaccine, receipt of prior season influenza vaccine, receipt of current season influenza vaccine, and number of annual health care visits.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients, by Influenza Virus Status

| Characteristic | Influenza Virus Negative, No. (%) (n = 2370) | Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Virus Positive, No. (%) (n = 170) | Influenza A(H3N2) Virus Positive, No. (%) (n = 523) | Influenza B Virus Positive, No. (%) (n = 222) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| 45–54 | 816 (34) | 85 (50) | 186 (36) | 91 (41) |

| 55–64 | 663 (28) | 56 (33) | 144 (28) | 66 (30) |

| 65–74 | 496 (21) | 19 (11) | 104 (20) | 49 (22) |

| ≥75 | 395 (17) | 10 (6) | 89 (17) | 16 (7) |

| Male sex | 887 (37) | 62 (36) | 212 (41) | 93 (42) |

| White | 2278 (96) | 167 (98) | 510 (98) | 218 (98) |

| Any high-risk condition | 1471 (62) | 72 (42) | 294 (56) | 113 (51) |

| Cardiovascular | 693 (29) | 27 (16) | 135 (26) | 38 (17) |

| Diabetes | 434 (18) | 17 (10) | 94 (18) | 33 (15) |

| Pulmonary | 542 (23) | 23 (14) | 80 (15) | 35 (16) |

| Other | 842 (36) | 48 (28) | 154 (29) | 70 (32) |

| Obese (BMIa ≥40) | 310 (13) | 18 (11) | 50 (10) | 26 (12) |

| LDL cholesterol level > 130 mg/dL | 519 (22) | 43 (25) | 100 (19) | 54 (24) |

| HDL cholesterol level < 40 mg/dL (men) or <50 mg/dL (women) | 914 (39) | 63 (37) | 153 (29) | 71 (32) |

| Received pneumococcal vaccine | 1245 (53) | 56 (33) | 256 (49) | 83 (37) |

| Received prior season influenza vaccine | 1568 (66) | 83 (49) | 307 (59) | 96 (43) |

| Current season influenza vaccination | 1582 (67) | 70 (41) | 313 (60) | 99 (45) |

| Provider visits in past year, no. | ||||

| ≤5 | 830 (35) | 91 (54) | 218 (42) | 112 (50) |

| 6–20 | 1180 (50) | 69 (41) | 258 (49) | 98 (44) |

| >20 visits | 360 (15) | 10 (6) | 47 (9) | 12 (5) |

| Statin use, mgb | ||||

| 0 (nonuser) | 1498 (63) | 132 (78) | 333 (64) | 157 (71) |

| 1–10 | 248 (10) | 8 (5) | 49 (9) | 15 (7) |

| 710–19 | 294 (12) | 10 (6) | 66 (13) | 17 (8) |

| >20 | 330 (14) | 20 (12) | 75 (14) | 33 (15) |

Data on the 61 patients with A with no subtype are not shown.

Abbreviations: A(H1N1)pdm09, 2009 pandemic A(H1N1); HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

a Body mass index (BMI) is calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the height in square meters.

b Statin dose in atorvastatin equivalents.

Influenza A(H3N2)

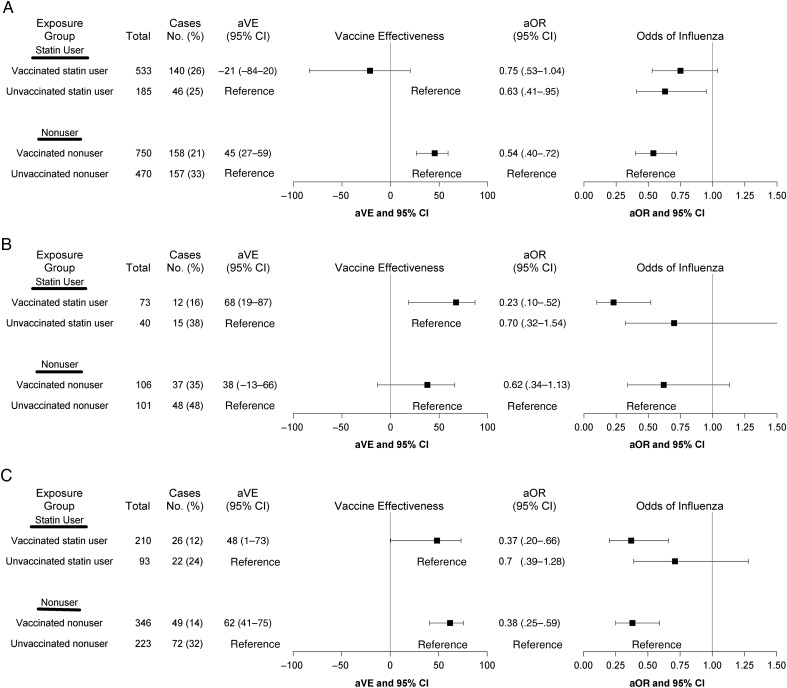

For influenza A(H3N2), vaccine effect modification by statins was demonstrated by a significant interaction (P = .03) between statin use and influenza vaccination (Figure 2A). Adjusted VE against influenza A(H3N2) was 45% (95% CI, 27%–59%) among nonusers and −21% (95% CI, −84% to 20%) among statin users. Similar results were obtained after exclusion of the 2014–2015 season, when there was a mismatch between vaccine and circulating strains. Adjusted VE was 48% (95% CI, 28%–63%) among nonusers and −46% (95% CI, −143% to 12%) among statin users (P = .0006).

Figure 2.

Adjusted vaccine effectiveness (aVE) and adjusted odd ratios (aORs), by influenza virus subtype. Models were adjusted for age, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, prior pneumococcal vaccination, and influenza season. A, Influenza A(H3N2) virus. Seasons included 2004–2005, 2007–2008, 2011–2012, 2012–2013, and 2014–2015. B, 2009 Pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus. Season included 2013–2014. C, Influenza B virus. Seasons included 2007–2008, 2012–2013, and 2014–2015. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Statins were also associated with a reduced odds of influenza A(H3N2) infection that was independent of vaccination. An apparent protective effect was observed in the unvaccinated statin users, compared with unvaccinated nonusers (aOR, 0.63; 95% CI, .41–.95). We conducted a stratified analysis based on prior season influenza vaccination to assess the effect of statin use in persons who were vaccinated in 2 consecutive seasons. This included 295 case with influenza A(H3N2) infection who were vaccinated and 206 cases with influenza A(H3N2) infection who were unvaccinated in the prior season. Statin use did not modify the effect of current season influenza vaccination among participants who did not receive prior season vaccination (P = .2) and among those who received prior season vaccination (P = .3). However, the trend of reduced VE among statin users was apparent in both models, although CIs were wide (Figure 3A and 3B). Among participants who did not receive prior season vaccine, odds of influenza A(H3N2) infection were significantly reduced in unvaccinated statin users, compared with unvaccinated nonusers (aOR, 0.55; 95% CI, .33–.92), but statin use alone was not associated with a reduced risk of influenza A(H3N2) infection among those who received prior season vaccine.

Figure 3.

Adjusted vaccine effectiveness (aVE) and adjusted odd ratios (aORs), by prior season vaccination status for influenza A(H3N2) virus. Influenza seasons included 2004–2005, 2007–2008, 2011–2012, 2012–2013, and 2014–2015. Models adjusted for age, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, prior pneumococcal vaccination, and influenza season. A, No prior season vaccination. B, Prior season vaccination. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and Influenza B

Statin use did not modify the effect of vaccination on influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 or influenza B (P = .2 and .5, respectively; Figure 2B and 2C). However, estimates for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 included only 1 season with 112 cases. For both influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and influenza B, unvaccinated statin users had a reduced odds of influenza, compared with unvaccinated nonusers, but CIs were wide and not significant.

Effect of Statin Type and Dose

Among statin users, 795 (68%) were receiving nonsynthetic statins, and 370 (32%) were receiving synthetic statins. Synthetic statin users were more likely to have cardiovascular disease (53% vs 40%; P < .001) and diabetes (42% vs 34%; P = .01), compared with nonsynthetic statin users. For influenza A(H3N2), effect modification of VE was significant for nonsynthetic statins (P = .003) but not synthetic statins (P = .2), but sample size was limited for the latter (Figure 4). Adjusted VE was 46% (95% CI, 28%–60%) among nonusers and −24 (95% CI, −102% to 24%) among nonsynthetic statin users.

Figure 4.

Adjusted vaccine effectiveness (aVE) and adjusted odd ratios (aORs) for influenza A(H3N2) virus, by statin type. Influenza seasons included 2004–2005, 2007–2008, 2011–2012, 2012–2013, and 2014–2015. Models were adjusted for age, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, prior pneumococcal vaccination, and influenza season. A, Synthetic statin. B, Nonsynthetic statin. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Odds of influenza A(H3N2) infection among nonsynthetic statin users was similar to that for vaccinated nonusers, irrespective of vaccination status. Use of nonsynthetic statins alone (without vaccination) was associated with a reduced odds of influenza A(H3N2) infection (aOR, 0.55; 95% CI, .35–.89). There was no evidence of reduced risk of influenza A(H3N2) in vaccinated or unvaccinated synthetic statin users when compared to unvaccinated nonusers.

In the dose-response analysis, there was no apparent trend in VE against influenza A(H3N2) by increasing tertile of statin dose (data not shown).

Validation Analyses

To evaluate the specificity of the statin effect, the analysis was repeated using data on other cardiovascular drug use and pneumococcal vaccination. When each drug category was analyzed separately or as a composite of cardiovascular medications, VE estimates against influenza A(H3N2), influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, and influenza B were similar for both users and nonusers (P ≥ .2). There was also no evidence of a protective effect among unvaccinated individuals who received these drugs (data not shown). Similarly, there was no effect modification with statin use and pneumococcal vaccination for influenza A(H3N2), influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, or influenza B (P ≥ .2; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that statin use modified the effect of influenza vaccination for influenza A(H3N2), but no effect was observed for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 or influenza B. For both influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and influenza B, statin users had significant vaccine protection, and VE estimates were similar to pooled VE estimates reported for working age adults in a recent meta-analysis of test-negative VE studies [16]. For influenza A(H3N2) infections, use of statins was associated with reduced vaccine-induced protection. The risk of influenza A(H3N2) infection was lowest in vaccinated nonusers and highest in vaccinated statin users when compared with unvaccinated nonusers. Statin use alone (without vaccination) was associated with significantly reduced odds of influenza A(H3N2) infection when compared to unvaccinated nonusers. A similar effect of statin use alone was observed for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and influenza B, but these were not statistically significant. These results suggest that 2 potential statin effects should be evaluated in future studies: the potential interference of statins with vaccine-induced protection and an independent protective effect from statin use that may reduce the risk of influenza in the unvaccinated population.

A statin effect on influenza severity and influenza vaccine response is biologically plausible. In contrast to some cardiovascular drugs, statins have well-documented antiinflammatory effects involving multiple components of the innate and adaptive immune response. Statins decrease inflammatory markers and CD40/CD40L expression, which impacts proinflammatory response, antibody class switching, and antibody expression [17]. Statins also alter gene expression of immune cells and inhibit T-cell activation, function, and cytotoxicity [18]. Clinical trials have shown that statins reduce cardiovascular risk independently of cholesterol reduction, likely because of their antiinflammatory properties [19].

Few studies have specifically assessed statin use and influenza severity or outcomes. An observational study reported a beneficial effect of statins on influenza in hospitalized patients seen in a mixed season with both influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 circulating [20], but another study found no effect in an influenza A(H1N1)pdm09-dominant season [21]. Influenza virus, especially influenza A(H3N2), causes more severe illness than many other respiratory viruses, and the relative effect of statins on illness severity may be greater for influenza virus. If statin users experience milder influenza, they may be less likely to seek medical attention relative to statin nonusers. This could account for the apparent protective effect of statin use alone (without vaccination) against medically attended influenza, although residual confounding could also account for this observation since statin users and nonusers differ in many characteristics.

The biological basis for a differential statin effect by influenza virus subtype is uncertain. A post hoc analysis of data from a randomized vaccine trial demonstrated that postvaccination hemagglutination inhibition titers were significantly lower in statin users versus nonusers, and this varied by subtype [1]. The influenza A(H3N2) geometric mean antibody titer (GMT) after vaccination was 40% lower in statin users versus nonusers; GMT against influenza B and influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 was 28% lower in statin users. However, postvaccination titers against influenza A(H3N2) in statin users were substantially higher than the regulatory threshold for seroprotection (1:40). Additionally, statin-using adults who were seronegative at baseline had decreased immune response to influenza A(H3N2) and influenza B but not influenza A(H1N1)pdm09.

These differences in serologic response do not fully explain the specific effect of statins we found for medically attended influenza A(H3N2) infection. It is possible that we observed a specific influenza A(H3N2) effect only because the number of cases was too small to detect a similar effect for A(H1N1)pdm09 and type B. However, influenza A(H3N2) undergoes more-rapid antigenic change as compared to other influenza virus subtypes, and we speculate that statin use may impair the breadth of influenza A(H3N2) antibody response and cell-mediated immune response after vaccination. In particular, there is evidence that influenza vaccination generates a so-called back-boost effect by stimulating antibodies against similar influenza A(H3N2) strains encountered during prior episodes of infection or vaccination [22]. It is unknown whether statin use might alter this process. We also cannot rule out the possibility of residual or unmeasured confounding.

Statin use and vaccination history are highly correlated, and it is possible that the observed effects of statins were partially or entirely due to prior vaccination history. The effect of prior vaccination can vary by season and influenza virus subtype [8, 23–32]. However, we were unable to evaluate the independent effects of prior season vaccination and statin use on VE. Statin users and nonusers differ in other characteristics that could potentially affect the risk of influenza. We examined other classes of drugs that are widely prescribed for prevention or treatment of cardiovascular disease, and we found that these drugs provided no protection against influenza A(H3N2) and did not modify vaccine-induced protection.

Although this was an observational study, it has several strengths. These include prospective enrollment and testing of patients from a defined community population over multiple seasons, confirmation of influenza virus infection and subtype by RT-PCR, and access to detailed medication and clinical data in the electronic medical record. This study also has several important limitations. First, the study was restricted to patients who sought care for acute respiratory illness, and those with milder illness who did not seek care were excluded. Second, statin exposure was based on prescription data within a single care system. Pharmacy dispensing and insurance claims were not measured, and patients with a prescription for statins may be nonadherent to the medication, leading to misclassification of statin use. However, we used a previously validated algorithm and manually validated a sample of 120 records, with results similar to those published previously [11]. Unlike previously published interventional studies where statins were started at the time of vaccination [33, 34], chronic use of statins more closely fits real-world conditions, as statins are usually intended for long-term use. Finally, small sample size in some subgroups limited our ability to assess dose-response and effect of prior season vaccination.

The results of this study are consistent with recent published studies suggesting reduced serologic response to vaccination and lower VE against nonspecific acute respiratory illness in statin users. However, the biological basis for differential strain effects by subtype is uncertain. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and explore potential mechanisms for statin-induced effects on vaccine response and influenza severity.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Burney A. Kieke, MS, Carla Rottscheit, Deanna Cole, Rebecca Pilsner, and Sandra Strey, from the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health, for contributing to study data collection and analysis; and Alicia Fry, Brendan Flannery, and Fiona Havers, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for critical review of the manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Centers for the Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement U01 IP000471).

Potential conflicts of interest. H. Q. M., B. D. W. C., J. P. K., and E. A. B. receive research support from AstraZeneca/MedImmune. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Black S, Nicolay U, Del Giudice G, Rappuoli R. Influence of Statins on Influenza Vaccine Response in Elderly Individuals. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1224–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omer SB, Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Chamberlain AT, Brosseau JL, Orenstein WA. Impact of Statins on Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Against Medically Attended Acute Respiratory Illness. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VanWormer JJ, Bateman AC, Irving SA, Kieke BA, Shay DK, Belongia EA. Reply to Fedson. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:1301–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belongia EA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG et al. Effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccines varied substantially with antigenic match from the 2004–2005 season to the 2006–2007 season. J Infect Dis 2009; 199:159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belongia EA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in Wisconsin during the 2007–08 season: comparison of interim and final results. Vaccine 2011; 29:6558–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treanor JJ, Talbot HK, Ohmit SE et al. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccines in the United States during a season with circulation of all three vaccine strains. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:951–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bateman AC, Kieke BA, Irving SA, Meece JK, Shay DK, Belongia EA. Effectiveness of Monovalent 2009 Pandemic Influenza A Virus Subtype H1N1 and 2010–2011 Trivalent Inactivated Influenza Vaccines in Wisconsin During the 2010–2011 Influenza Season. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:1262–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohmit SE, Thompson MG, Petrie JG et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the 2011–2012 season: protection against each circulating virus and the effect of prior vaccination on estimates. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaglani M, Pruszynski J, Murthy K et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Against 2009 Pandemic Influenza A(H1N1) Virus Differed by Vaccine Type During 2013–2014 in the United States. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1546–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irving SA, Donahue JG, Shay DK, Ellis-Coyle TL, Belongia EA. Evaluation of self-reported and registry-based influenza vaccination status in a Wisconsin cohort. Vaccine 2009; 27:6546–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peissig P, Sirohi E, Berg RL et al. Construction of atorvastatin dose-response relationships using data from a large population-based DNA biobank. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2007; 100:286–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller AW, McCarty CA, Broeckel U, Hytopoulos V, Cross DS. Development of reusable logic for determination of statin exposure-time from electronic health records. J Biomed Inform 2014; 49:206–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foppa IM, Haber M, Ferdinands JM, Shay DK. The case test-negative design for studies of the effectiveness of influenza vaccine. Vaccine 2013; 31:3104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson ML, Nelson JC. The test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2013; 31:2165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flannery B, Zimmerman RK, Gubareva LV et al. Enhanced genetic characterization of influenza A(H3N2) viruses and vaccine effectiveness by genetic group, 2014–2015. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:1010–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belongia EA, Simpson MD, King JP et al. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:942–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schonbeck U, Libby P. Inflammation, immunity, and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: statins as antiinflammatory agents? Circulation 2004; 109(21 Suppl 1): II18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bu DX, Griffin G, Lichtman AH. Mechanisms for the anti-inflammatory effects of statins. Curr Opin Lipidol 2011; 22:165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:2195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandermeer ML, Thomas AR, Kamimoto L et al. Association between use of statins and mortality among patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infections: a multistate study. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brett SJ, Myles P, Lim WS et al. Pre-admission statin use and in-hospital severity of 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) disease. PLoS One 2011; 6:e18120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fonville JM, Wilks SH, James SL et al. Antibody landscapes after influenza virus infection or vaccination. Science 2014; 346:996–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaglani M, Pruszynski J, Murthy K et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Against 2009 Pandemic Influenza A(H1N1) Virus Differed by Vaccine Type During 2013–2014 in the United States. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1546–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLean HQ, Thompson MG, Sundaram ME et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during 2012–2013: variable protection by age and virus type. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:1529–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLean HQ, Thompson MG, Sundaram ME et al. Impact of Repeated Vaccination on Vaccine Effectiveness Against Influenza A(H3N2) and B During 8 Seasons. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1375–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohmit SE, Petrie JG, Malosh RE et al. Substantial Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in Households With Children During the 2013–2014 Influenza Season, When 2009 Pandemic Influenza A(H1N1) Virus Predominated. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1229–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skowronski DM, Janjua NZ, De Serres G et al. A sentinel platform to evaluate influenza vaccine effectiveness and new variant circulation, Canada 2010–2011 season. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:332–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skowronski DM, Janjua NZ, Sabaiduc S et al. Influenza A/subtype and B/lineage effectiveness estimates for the 2011–2012 trivalent vaccine: cross-season and cross-lineage protection with unchanged vaccine. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:126–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skowronski DM, Janjua NZ, De Serres G et al. Low 2012–13 Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Associated with Mutation in the Egg-Adapted H3N2 Vaccine Strain Not Antigenic Drift in Circulating Viruses. PLoS One 2014; 9:e92153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skowronski DM, Chambers C, Sabaiduc S et al. Integrated Sentinel Surveillance Linking Genetic, Antigenic, and Epidemiologic Monitoring of Influenza Vaccine-Virus Relatedness and Effectiveness During the 2013–2014 Influenza Season. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:726–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skowronski DM, Chambers C, Sabaiduc S et al. A perfect storm: Impact of genomic variation and serial vaccination on low influenza vaccine effectiveness during the 2014–15 season. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosterin Hopping A, McElhaney J, Fonville JM, Powers DC, Beyer WE, Smith DJ. The confounded effects of age and exposure history in response to influenza vaccination. Vaccine 2016; 34:540–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee PY, Scumpia PO, Byars JA et al. Short-term atorvastatin treatment enhances specific antibody production following tetanus toxoid vaccination in healthy volunteers. Vaccine 2006; 24:4035–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Packard RR, Schlegel S, Senouf D et al. Atorvastatin treatment and vaccination efficacy. J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 47:1022–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]