Abstract

Background. It is unknown whether immunosuppression influences the physiologic state of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. We evaluated the impact of host immunity by comparing M. tuberculosis and human gene transcription in sputum between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected and uninfected patients with tuberculosis.

Methods. We collected sputum specimens before treatment from Gambians and Ugandans with pulmonary tuberculosis, revealed by positive results of acid-fast bacillus smears. We quantified expression of 2179 M. tuberculosis genes and 234 human immune genes via quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. We summarized genes from key functional categories with significantly increased or decreased expression.

Results. A total of 24 of 65 patients with tuberculosis were HIV infected. M. tuberculosis DosR regulon genes were less highly expressed among HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis than among HIV-uninfected patients with tuberculosis (Gambia, P < .0001; Uganda, P = .037). In profiling of human genes from the same sputa, HIV-infected patients had 3.4-fold lower expression of IFNG (P = .005), 4.9-fold higher expression of ARG1 (P = .0006), and 3.4-fold higher expression of IL10 (P = .0002) than in HIV-uninfected patients with tuberculosis.

Conclusions. M. tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients had lower expression of the DosR regulon, a critical metabolic and immunomodulatory switch induced by NO, carbon monoxide, and hypoxia. Our human data suggest that decreased DosR expression may result from alternative pathway activation of macrophages, with consequent decreased NO expression and/or by poor granuloma formation with consequent decreased hypoxic stress.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis/genetics, Mycobacterium tuberculosis/physiology, sputum/microbiology, tuberculosis, pulmonary/epidemiology, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome/immunology

(See the editorial commentary by Schluger on pages 1137–8.)

Tuberculosis is the leading cause of death among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected persons [1]. HIV infection has pervasive effects on human immunity, including altered cytokine and chemokine expression, changes in macrophage polarization, and T-cell dysfunction and depletion, leading to clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic presentations of tuberculosis unlike those observed in immunocompetent hosts [2]. It is poorly understood how HIV-associated immune impairment affects the physiologic state of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Enhanced understanding of this interaction is crucial because the phenotypic state of M. tuberculosis alters antibiotic effectiveness [3, 4] and may affect transmission fitness [5].

M. tuberculosis dynamically adapts its physiologic state to withstand immune responses and diverse tissue microenvironmental conditions [6, 7]. In vivo microenvironments have variable pH, nutrient availability, and oxygen tension. Hypoxia is encountered in the necrotic center of well-organized granulomas [8, 9] and macrophage phagosomes [5]. Among persons with HIV infection, granuloma formation is impaired. Unlike immunocompetent persons, in whom granulomas display a finely organized architecture with spatially modulated gradients of T-cell and macrophage phenotypes [10–12], patients with tuberculosis with advanced HIV infection develop disorganized granulomas that are poorly contained collections of polymorphonuclear cells and eosinophils with a paucity of mononuclear, epithelioid, or giant cells [13–17]. Poorly contained lesions in animal tissues are not hypoxic, and this may also be the case in HIV‐infected patients with tuberculosis [8, 9, 18, 19].

In response to conditions that limit aerobic respiration (hypoxia, carbon monoxide [CO], or nitric oxide [NO]), M. tuberculosis increases expression of the DosR regulon, a set of 48 genes that is essential for survival and virulence in well-formed hypoxic granulomas [6, 8, 20]. DosR proteins additionally appear to modulate adaptive immunity, eliciting T-cell responses that enhance host granuloma formation [8, 21].

Gene expression profiling of pathogens in host tissues, fluids, or cultured cells provides a molecular snapshot of dynamic host-pathogen interactions [6, 22] but has not been used to probe M. tuberculosis adaptation to the altered immune milieu of HIV-infected patients. Understanding the bacterial transcriptional phenotype in clinical samples from patients with tuberculosis is important because transcriptional profiling studies indicate that the physiologic state of M. tuberculosis in human samples differs from the physiologic state of the organism in murine and in vitro models of tuberculosis [23–25].

To elucidate how the immunologic state of the host correlates with the physiologic state of M. tuberculosis, we compared M. tuberculosis gene expression in the sputa of HIV-infected and uninfected patients with untreated active pulmonary tuberculosis. To elucidate how differences in the human immune state are correlated with M. tuberculosis transcriptional responses, we used the same sputum samples to measure the expression of a panel set of human genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses.

METHODS

Enrollment and Specimen Collection

Adults with pulmonary tuberculosis (based on positive results of either sputum acid-fast bacillus smear or GeneXpert M. tuberculosis/RIF testing) were enrolled prior to receipt of antibiotic treatment at the Medical Research Council TB Diagnostic Laboratories in Fajara, Gambia, and at Mulago National Referral Hospital in Kampala, Uganda (Supplementary Materials). Specimen collection and laboratory assays followed previously described methods [23]. Briefly, spontaneously expectorated sputum was preserved within 5 minutes in guanidine thiocyanate solution. Sputa were needle sheared, centrifuged at 9000 × g, and stored in Trizol at −80°C. All patients were offered HIV testing. Chest radiographs were evaluated for cavitation, using a standardized protocol. Institutional review boards in Gambia, Uganda, and the United States (Supplementary Materials) approved the study. All patients provided written informed consent.

Laboratory Analysis

We selected only samples with both known HIV status and infection with lineage 4 (EuroAmerican) M. tuberculosis strains, based on spoligotyping, to limit potential confounding due to lineage differences. After extraction of total RNA, quality was assessed using a test panel targeting 24 M. tuberculosis transcripts. M. tuberculosis transcriptional profiles were then quantified on good-quality RNA via multiplex quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) [23]. Briefly, after first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis, cDNA underwent controlled multiplex amplification, using M. tuberculosis–specific flanking primers. Transcripts for 2179 M. tuberculosis genes were quantified via multiplex qRT-PCR with a LightCycler 480 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), using TaqMan probes.

To elucidate immunologic alterations that may be responsible for differences in M. tuberculosis transcriptional phenotypes of HIV-infected and uninfected patients, we also assayed a panel of 234 human genes selected because of their association with T-cell phenotypes or macrophage polarization. Details of TaqMan primers are available at: http://genes.stanford.edu/oli/genes.php?organism=h. Human gene expression was assayed in the Ugandan samples only.

Analysis

Messenger RNA (mRNA) expression data were normalized using a median normalization method validated for samples with low nondetection [26]. We identified differentially expressed M. tuberculosis genes in HIV-infected versus uninfected hosts via t tests, with an α level 0.05. To explore trends and summarize enrichment in previously described M. tuberculosis physiologic categories [23], we evaluated the proportion of genes in each category with a nominal (unadjusted) P value of <.05. Statistical significance of categorical enrichment was determined using a modified 1-way Fisher exact test [27]. Categories with an adjusted P value of <.05 after Benjamini-Hockberg (BH) adjustment for multiple comparisons were considered significant. We identified differentially expressed human genes in HIV-infected versus uninfected hosts using t tests with a BH-adjusted α of 0.05 and a fold-change cutoff of 1.75. Analysis used the R statistical suite, version 3.0.1, except as noted in the Supplementary Materials.

RESULTS

Enrollment and Clinical Characteristics

In a pilot study, we assayed M. tuberculosis gene expression in the sputa of 19 Gambian adults with drug-susceptible, sputum acid-fast bacillus smear-positive, culture-positive pulmonary tuberculosis, 4 of whom were HIV infected (enrollment flow is shown in Supplementary Figure 1). Thereafter, we enrolled 46 adults with pulmonary tuberculosis in Uganda, 20 of whom were HIV infected. Among HIV-infected Ugandan patients, the median CD4+ T-cell count was 25 cells/μL (interquartile range, 6–71 cells/μL; Table 1). None were receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy at the time of tuberculosis diagnosis. Among Ugandans with chest radiographs available, cavitation was more common among HIV-uninfected patients (19 [91%]) than among HIV-infected patients (9 [47%]; P = .009).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Tuberculosis in Gambia (Pilot Study) and Uganda Who Underwent Pathogen-Targeted Gene Expression Profiling, by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Status

| Characteristic | HIV Infected | HIV Uninfected | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Gambia | 36 (28–44) | 25 (21–32) | .4 |

| Uganda | 30 (26–37) | 30 (22–35) | .4 |

| Women | |||

| Gambia | 3 (75) | 1 (7) | .02 |

| Uganda | 9 (45) | 8 (31) | .5 |

| CD4+ T-cell count, cells/μLa | |||

| Uganda | 26 (6–71) | … | |

| Radiographic cavitation | |||

| Gambiab | 1 (33) | 8 (67) | .7 |

| Ugandac | 9 (47) | 19 (90) | .009 |

| Light microscopy results | |||

| Gambia | |||

| Negative | … | ||

| Scanty/1+ | … | 1 (7) | |

| 2+ | 1 (25) | 4 (27) | |

| 3+ | 3 (75) | 10 (67) | |

| Uganda | |||

| Negative | 2 (10) | … | |

| Scanty/1+ | 3 (15) | 5 (19) | |

| 2+ | 9 (45) | 8 (31) | |

| 3+ | 6 (30) | 13 (50) | |

Data are median (interquartile range) or no. (%) of patients.

a Data were unavailable in the pilot experiment in Gambia.

b Data were missing for 1 HIV-infected patient and 3 HIV-uninfected patients.

c Data were missing for 1 HIV-infected patients and 5 HIV-uninfected patients.

Less Induction of M. tuberculosis DosR Regulon Genes in HIV-Infected Patients

In Gambia, comparison of M. tuberculosis gene expression profiles between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients showed that 447 genes (20.5% of the profiled) had a P value of <.05, considerably more than expected by chance alone (Supplementary Table 1A). When repeated in Uganda, 385 genes (17.7%) had a P value of <.05 (Supplementary Table 1B).

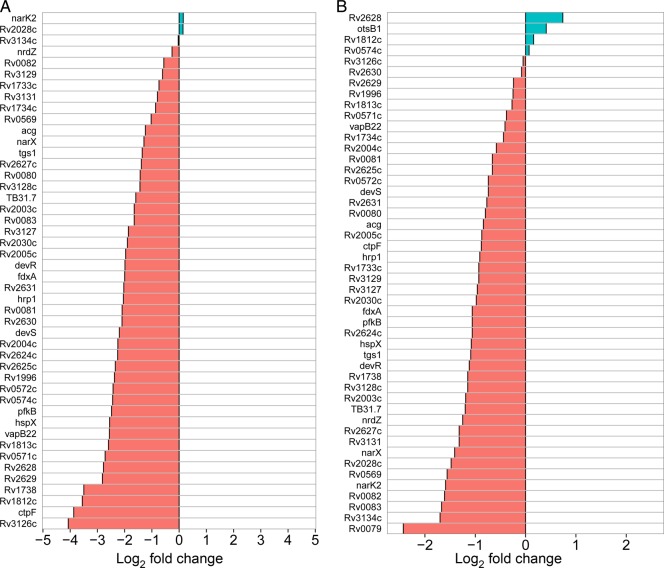

Enrichment analysis of functional gene categories in genes with a P value of <.05 showed that the expression of DosR regulon genes was significantly lower among HIV-infected patients than among HIV-uninfected patients (BH-adjusted P < .0001 in Gambia; P = .03 in Uganda). In Gambia, 32 of 48 DosR regulon genes had significantly lower expression (P < .05) among HIV-infected patients (Figure 1A and 1B); no DosR genes had significantly higher expression in HIV-infected individuals. In Uganda, 14 DosR regulon genes had significantly lower expression among HIV-infected patients; 1 DosR gene, which encodes hypothetical protein Rv2628, had higher expression in HIV-infection individuals. In Gambia, the DosR regulon was the only gene category significantly differentially expressed. In Uganda, the category of primary metabolism genes, including tricarboxylic acid cycle genes, ATP synthases, and other aerobic respiration genes, also had lower expression among HIV-infected patients (BH-adjusted P = .03).

Figure 1.

Expression of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis DosR regulon in sputa from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected vs uninfected patients with tuberculosis in Gambia (A) and Uganda (B). Red indicates decreased expression in HIV-infected individuals, and blue indicates increased expression.

Host Transcriptome Indicates Altered Immune Milieu in HIV-Infected Patients

Expression of human genes associated with T-cell phenotypes and macrophage polarization were profoundly different between HIV-infected and uninfected patients. Of 234 genes that encode immunity and inflammatory functions, 86 (36.8%) had a P value of <.05; 33 (14.0%) remained significant with a fold change of >1.75 after adjustment for multiple comparisons (significantly altered genes are shown in Table 2; the full list of genes is shown in Supplementary Table 2). Relative to HIV-uninfected patients, HIV-infected patients had 3.4-fold lower expression of IFNG (BH-adjusted P = .005) and 1.8-fold lower expression of IRF1 (BH-adjusted P = .02). HIV-infected patients had 4.9-fold higher expression of ARG1 (BH-adjusted P = .0006) and 3.4-fold higher expression of IL10 (BH-adjusted P = .0002). There was no significant difference between HIV-infected and uninfected patients in the expression of TNF, NOS, and HMOX1 (BH-adjusted P = .49, .17, and .26, respectively).

Table 2.

Human Genes Significantly Differentially Expressed in the Sputum of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)–Infected Versus Uninfected Ugandan Patients With Tuberculosis After Adjustment for Multiple Comparisons

| Gene | Expression in HIV-Infected Patients | Fold Change From Expression in Uninfected Patients | Adjusted P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL13 | Downregulated | −6.64 | .011 |

| CXCL9 | Downregulated | −4.77 | .000 |

| IFNG | Downregulated | −3.40 | .005 |

| SCYA22 | Downregulated | −2.73 | .022 |

| IDO1 | Downregulated | −2.52 | .016 |

| FOXP3 | Downregulated | −2.47 | .042 |

| IL1B | Downregulated | −2.25 | .020 |

| MMP12 | Downregulated | −2.18 | .022 |

| SCYA3 | Downregulated | −2.15 | .016 |

| BD1 | Downregulated | −2.09 | .023 |

| RELA | Downregulated | −2.00 | .024 |

| CDKN1A | Downregulated | −1.86 | .039 |

| DTR | Downregulated | −1.83 | .011 |

| IRF1 | Downregulated | −1.79 | .024 |

| OAS2 | Upregulated | 1.80 | .022 |

| TLR10 | Upregulated | 2.02 | .016 |

| SMAD1 | Upregulated | 2.16 | .016 |

| IGF1R | Upregulated | 2.24 | .022 |

| STAT4 | Upregulated | 2.38 | .007 |

| CD8B | Upregulated | 2.45 | .001 |

| MMP8 | Upregulated | 2.51 | .012 |

| IL18 | Upregulated | 2.69 | .003 |

| NLRC4 | Upregulated | 2.70 | .016 |

| CD8A | Upregulated | 2.74 | .021 |

| TCF4 | Upregulated | 2.79 | .000 |

| LSGAL10 | Upregulated | 2.81 | .006 |

| IGF1 | Upregulated | 2.83 | .016 |

| SERPINB10 | Upregulated | 3.04 | .016 |

| IL10 | Upregulated | 3.40 | .000 |

| BBC3 | Upregulated | 4.17 | .016 |

| ARG1 | Upregulated | 4.88 | .001 |

| IFI27 | Upregulated | 6.32 | .001 |

| IFNB1 | Upregulated | 6.74 | .022 |

DISCUSSION

This analysis provides novel insight into how HIV infection transforms the interaction between M. tuberculosis and host immunity. We found that the presence of HIV infection in patients with tuberculosis was associated primarily with decreased induction of the DosR regulon, a crucial metabolic switch with immunomodulatory effects. This interaction was identified among patients in Gambia and confirmed among Ugandans. Host transcriptional data suggest that lower expression of DosR regulon among HIV-infected patients may be a direct result of arginase 1–driven decreased macrophage NO production and/or an indirect result of decreased hypoxic stress in poorly formed granulomas. This analysis provides a novel perspective on the complex interplay between HIV-associated immune impairment, altered tissue microenvironments, and M. tuberculosis physiologic state.

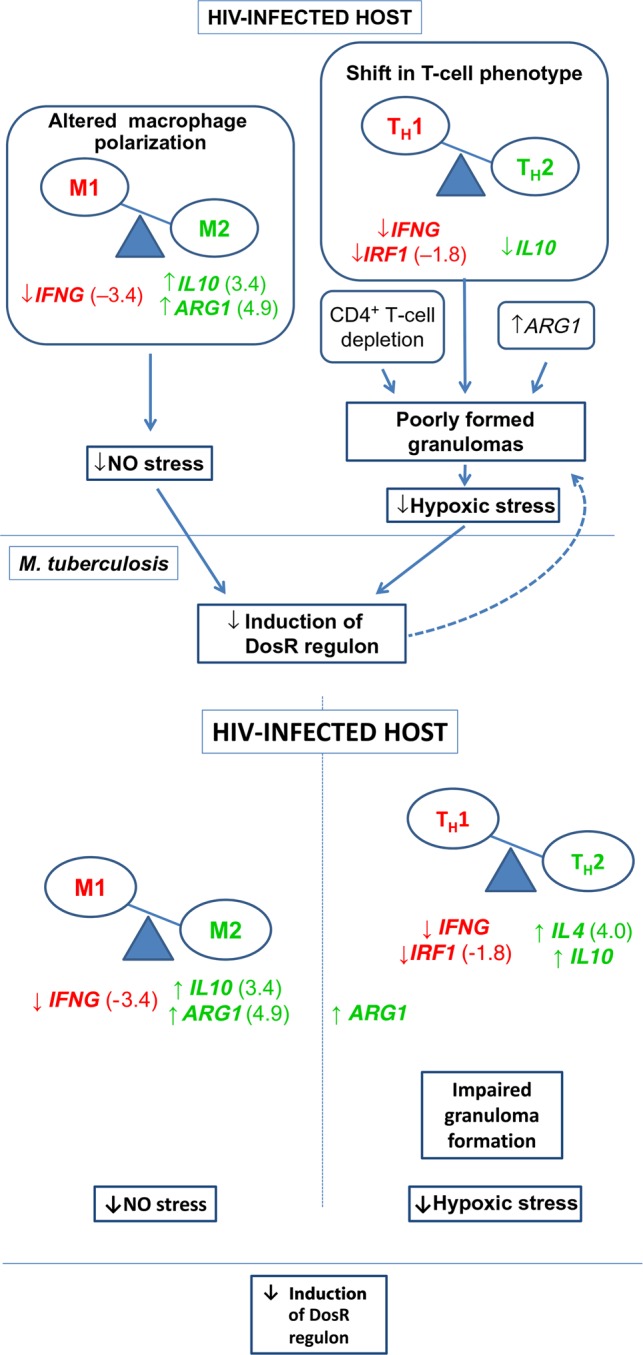

The DosR regulon is an M. tuberculosis genetic program that directs metabolic adaptation to conditions that inhibit aerobic respiration, including hypoxia and the presence of NO and CO [28]. Our data identify several interacting mechanisms by the host that are likely to decrease NO and hypoxic stress for M. tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients, resulting in decreased induction of the M. tuberculosis DosR regulon (Figure 2). First, human gene expression signatures in these M. tuberculosis–infected samples suggests that the presence of HIV infection biases macrophages to the alternatively activated (M2) phenotype. The classification of the M2 phenotype is increasingly complex, with at least 3 recognized M2 subtypes [29]. However a consistent paradigm is that M2 macrophages have reduced inducible NO synthase activity and greater arginase 1 activity [11], ultimately resulting in reduced NO production. Reduced production of NO likely impairs control of M. tuberculosis in host tissues because NO is host-protective: it interferes with bacterial DNA and proteins and enhances apoptosis of M. tuberculosis–infected macrophages [30]. NO also inhibits M. tuberculosis aerobic respiration, resulting in a reduced M. tuberculosis replication rate and increased DosR expression [20].

Figure 2.

Differential expression of human genes associated with granuloma formation and macrophage polarization in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected versus uninfected patients with tuberculosis, with hypothesized consequences. Red indicates significantly decreased and green significantly increased expression in HIV-infected samples. Mean fold-change in HIV-infected samples relative to uninfected samples is shown in parentheses. Expression of cytokine genes suggests that the presence of HIV infection biases macrophages to the alternatively activated (M2) phenotype, a change anticipated to diminish NO stress. Poor granuloma formation and consequent diminished hypoxic stress may result from (1) CD4+ T-cell depletion, (2) a shift in the residual CD4+ T-cell population from the T-helper type 1 (TH1) interferon γ–producing phenotype toward the TH2 phenotype, or (3) arginase 1–mediated inhibition of T-cell proliferation. DosR regulon proteins induce T-cell and interferon γ responses, enhancing granuloma formation. Decreased expression of the DosR regulon is therefore anticipated to further impair granuloma formation.

Consistent with a shift toward an M2 phenotype, HIV-infected patients had a 4.9-fold increase in expression of ARG1 (Figure 2); arginase 1 at increased levels outcompetes NOS2 for their common substrate, L-arginine, downregulating macrophage NO production and increasing the susceptibility of mice to M. tuberculosis [31, 32]. Similarly, HIV-infected patients had 3.4-fold increased expression of IL10, a marker of M2 macrophage polarization that is associated with enhanced M. tuberculosis survival [32, 33]. Conversely, HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis in this study had markedly decreased (by 3.4-fold) expression of IFNG, a principal mediator of classical (M1) macrophage activation in tuberculosis [34]. These observations, which are consistent with previous in vitro and human studies of HIV-infected macrophages [35, 36], represent a confluence of alterations that impair anti–M. tuberculosis effector mechanisms and likely reduce NO production, with consequent decrease in M. tuberculosis's requirement for DosR regulon expression.

Decreased hypoxic stress due to dysregulated granuloma morphology represents an additional HIV-associated alteration likely to diminish induction of M. tuberculosis DosR expression [8, 9, 18, 19]. In immunocompetent hosts who form well-organized hypoxic granulomas, DosR is necessary to sustain persistent infection after the onset of adaptive immunity [8]. Conversely, DosR is not necessary for infection in animal models that form poorly organized, nonhypoxic lesions similar to those observed in HIV-infected patients [8, 9, 18, 19]. Our data support multiple mechanisms that may sabotage granuloma formation. In addition to profound CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion, HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis had decreased expression of IFNG and increased expression of IL10, consistent with a shift in the residual CD4+ T-cell population from the T-helper type 1 (TH1) IFN-γ–producing phenotype toward the TH2 phenotype. IL-10 is an antiinflammatory cytokine that inhibits formation of mature granulomas [37]. A TH1 to TH2 shift has long been considered characteristic of HIV-associated immune dysregulation [38], tending to impair granuloma formation [10–12]. Further, increased ARG1 expression limits T-cell proliferation, independent of its effect on NO [10]. Since poorly formed granulomas such as those observed in HIV-infected patients are less hypoxic than well-formed granulomas typical of immunocompetent patients [8, 9, 18, 19], the anticipated result is diminished hypoxic stress and decreased M. tuberculosis requirement for DosR.

A final potential explanation for lower DosR expression among HIV-infected patients is CO. Heme oxygenase 1–mediated CO generation appears to induce DosR expression in M. tuberculosis–infected macrophages [39]. However, HMOX1 was not differentially expressed between HIV-infected and uninfected persons, suggesting that differential CO exposure is less likely the cause of decreased DosR expression among HIV-infected patients. The putative mechanisms leading to decreased DosR expression during HIV infection may be cumulative and interacting; all shape the tissue microenvironment to which M. tuberculosis must adapt.

The interaction between host microenvironments and bacterial physiology is not unilateral; M. tuberculosis may modulate host immunity. A number of DosR regulon proteins have strong T-cell– and IFN-γ–inducing capacity [21] and appear to enhance granuloma formation [8]. Consistent with this hypothesis, DosR mutants cause less tissue pathology in mice relative to wild-type M. tuberculosis, despite a similar bacillary burden [8, 40]. This suggests that downregulation of the DosR regulon may not only be a consequence but also a cause of altered host responses in patients coinfected with HIV and M. tuberculosis.

The M. tuberculosis transcriptional alterations we identified among HIV-infected subjects are important because the pathogen's phenotypic state influences antibiotic effectiveness both in vitro [3] and in vivo [41]. For example, C3Heb/FeJ mice, which form human-like caseating hypoxic granulomas in response to M. tuberculosis infection, are less susceptible to clofazimine than Balb/c mice that form nonhypoxic granulomas that are poorly formed [41, 42]. Future research is needed to understand specifically how the altered tissue microenvironments that result from HIV-associated immune dysregulation affect M. tuberculosis response to antibiotics in humans.

This study has several limitations. Different M. tuberculosis strains could have different gene expression responses. We alleviated but did not entirely eliminate this potential confounder by restricting our analysis to M. tuberculosis of EuroAmerican lineage. Furthermore, to address the possibility that HIV-infected patients were preferentially infected with strains that had lower capacity to express the DosR regulon, we exposed 5 clinical strains from our HIV-infected patients and 5 from uninfected patients to NO in vitro and evaluated expression of DosR regulon and enduring hypoxic response genes. This revealed no difference in the capacity of M. tuberculosis strains from HIV-infected and uninfected patients to express these genes (Supplementary Materials). Second, since our patients did not undergo lung biopsy, we could not directly assess granuloma organization or tissue oxygen tension. However, previous reports have described a strong and consistent impact of HIV on granuloma morphology [13–15], and disorganized, uncontained granulomas are shown in animals to be nonhypoxic [8, 9, 18, 19]. Since HIV-infected subjects in this study had advanced HIV infection (with a median CD4 T-cell count of 26 cells/μL), we presume they had similarly deranged granuloma formation. Third, eukaryotic cells are lysed by GTC, potentially resulting in loss of human mRNA in the supernatant during sample preparation. However, in the pellet used for transcriptional profiling of human mRNA remains vastly more abundant than M. tuberculosis mRNA. Since sample preparation was standardized and blinded to HIV status, systematic differences between HIV-infected and uninfected patients causing differential loss of specific transcripts seems unlikely.

In conclusion, in 2 geographically distinct populations, we found that M. tuberculosis differentially adapts its physiologic state to the HIV-infected host. M. tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients displayed decreased induction of the DosR regulon, a bacterial response to hypoxia and NO that has immunomodulatory effects. Our data suggest that this may be due to alternative activation of macrophages, with consequent decreased NO expression and/or decreased hypoxic stress in disorganized granulomas. These observations identify novel connections between host immunity, host tissue microenvironments, and bacterial phenotypes. Further investigation of what determines of M. tuberculosis phenotypes during human infection is important because bacterial physiologic state influences antibiotic effectiveness.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://jid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank study participants in The Gambia and Uganda and the staff and administration of Mulago National Referral Hospital and the Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration.

Financial support. This work was supported by the European Research Council Starting (grant INTERRUPTB 311725 to B. C. d. J.), the National Institutes of Health (grants UL1 RR025780 and 2T15LM009451-06 [to B. J. G.], R21AI101714 [to J. L. D.], K23AI080147 [to J. L. D.], K24HL087713 [to L. H.], R01HL090335 [to L. H.], 5R01AI104589 [to P. N.], and 2RO1 AI061505 [to M. I. V.]), the Veteran′s Administration (CDA1IK2CX000914-01A1 to N. D. W.), and a Boettcher Foundation Webb-Waring Award (to M. S.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: WHO report 2014. 2014.

- 2.Diedrich CR, Flynn JL. HIV-1/Mycobacterium tuberculosis coinfection immunology: how does HIV-1 exacerbate tuberculosis? Infect Immun 2011; 79:1407–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karakousis PC, Williams EP, Bishai WR. Altered expression of isoniazid-regulated genes in drug-treated dormant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 61:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voskuil MI, Visconti KC, Schoolnik GK. Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene expression during adaptation to stationary phase and low-oxygen dormancy. Tuberculosis 2004; 84:218–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham-Bussel A, Zhang T, Nathan CF. Nitrite produced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages in physiologic oxygen impacts bacterial ATP consumption and gene expression. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:E4256–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnappinger D, Ehrt S, Voskuil MI et al. Transcriptional adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages: insights into the phagosomal environment. J Exp Med 2003; 198:693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rachman H, Strong M, Ulrichs T et al. Unique transcriptome signature of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect Immun 2006; 74:1233–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehra S, Foreman TW, Didier PJ et al. The DosR regulon modulate adaptive immunity and is essential for M tuberculosis persistence. Am J Resp Crit Care 2015; 191:1185–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Via LE, Lin PL, Ray SM et al. Tuberculous granulomas are hypoxic in guinea pigs, rabbits, and nonhuman primates. Infect Immun 2008; 76:2333–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duque-Correa MA, Kühl AA, Rodriguez PC et al. Macrophage arginase-1 controls bacterial growth and pathology in hypoxic tuberculosis granulomas. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:E4024–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattila JT, Ojo OO, Kepka-Lenhart D et al. Microenvironments in tuberculous granulomas are delineated by distinct populations of macrophage subsets and expression of nitric oxide synthase and arginase isoforms. J Immunol 2013; 191:773–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marino S, Cilfone NA, Mattila JT, Linderman JJ, Flynn JL, Kirschner DE. Macrophage polarization drives granuloma outcome during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun 2015; 83:324–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Noronha ALL, Báfica A, Nogueira L, Barral A, Barral-Netto M. Lung granulomas from Mycobacterium tuberculosis/HIV-1 co-infected patients display decreased in situ TNF production. Pathol Res Pract 2008; 204:155–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller H, Krüger S. Immunohistochemical analysis of cell composition and in situ cytokine expression in HIV- and non-HIV-associated tuberculous lymphadenitis. Immunobiology 1994; 191:354–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Perri G, Cazzadori A, Vento S et al. Comparative histopathological study of pulmonary tuberculosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected and non-infected patients. Tuber Lung Dis 1996; 77:244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen J-Y, Barnes PF, Rea TH, Meyer PR. Immunohistology of tuberculosis adenitis in symptomatic HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol 1988; 72:186–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva AA, Mauas T, Saldiva PHN et al. Immunophenotype of lung granulomas in HIV and non-HIV associated tuberculosis. MedialExpress 2014; 1:174–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Converse PJ, Karakousis PC, Klinkenberg LG et al. Role of the dosR-dosS two-component regulatory system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence in three animal models. Infect Immun 2009; 77:1230–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aly S, Wagner K, Keller C et al. Oxygen status of lung granulomas in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice. J Pathol 2006; 210:298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voskuil MI, Schnappinger D, Visconti KC et al. Inhibition of respiration by nitric oxide induces a Mycobacterium tuberculosis dormancy program. J Exp Med 2003; 198:705–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leyten EMS, Lin MY, Franken KLMC et al. Human T-cell responses to 25 novel antigens encoded by genes of the dormancy regulon of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect 2006; 8:2052–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tailleux L, Waddell SJ, Pelizzola M et al. Probing host pathogen cross-talk by transcriptional profiling of both Mycobacterium tuberculosis and infected human dendritic cells and macrophages. PLoS One 2008; 3:e1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter ND, Dolganov GM, Garcia BJ et al. Transcriptional adaptation of drug-tolerant Mycobacterium tuberculosis during treatment of human tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:990–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garton NJ, Waddell SJ, Sherratt AL et al. Cytological and transcript analyses reveal fat and lazy persister-like bacilli in tuberculosis sputum. PLoS Med 2009; 5:e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honeyborne I, McHugh TD, Kuittinen I et al. Profiling persistent tubercule bacilli from patient sputa during therapy predicts early drug efficacy. BMC Med 2016; 14:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia B, Walter ND, Dolganov G et al. A minimum variance method for genome-wide data-driven normalization of qRT-PCR expression data. Anal Biochem 2014; 458:11–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosack D, Dennis G, Sherman B, Lane H, Lempicki R. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol 2003; 4:R70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honaker RW, Dhiman RK, Narayanasamy P, Crick DC, Voskuil MI. DosS responds to a reduced electron transport system to induce the Mycobacterium tuberculosis DosR regulon. J Bacteriol 2010; 192:6447–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27:451–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan ED, Chan J, Schluger NW. What is the role of nitric oxide in murine and human host defense against tuberculosis? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001; 25:606–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Kasmi KC, Qualls JE, Pesce JT et al. Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat Immunol 2008; 9:1399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schreiber T, Ehlers S, Heitmann L et al. Autocrine IL-10 induces hallmarks of alternative activation in macrophages and suppresses antituberculosis effector mechanisms without compromising T cell immunity. J Immunol 2009; 183:1301–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray PJ, Young RA. Increased antimycobacterial immunity in Interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infect Immun 1999; 67:3087–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med 1993; 178:2249–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel NR, Swan K, Li X, Tachado SD, Koziel H. Impaired M. tuberculosis-mediated apoptosis in alveolar macrophages from HIV+ persons: potential role of IL-10 and BCL-3. J Leukoc Biol 2009; 86:53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boussiotis VA, Tsai EY, Yunis EJ et al. IL-10–producing T cells suppress immune responses in anergic tuberculosis patients. J Clin Invest 2000; 105:1317–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cyktor JC, Carruthers B, Kominsky RA, Beamer GL, Stromberg P, Turner J. IL-10 inhibits mature fibrotic granuloma formation during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol 2013; 190:2778–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clerici M, Shearer GM. A TH1→TH2 switch is a critical step in the etiology of HIV infection. Immunol Today 1993; 14:107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar A, Deshane JS, Crossman DK et al. Heme oxygenase-1-derived carbon monoxide induces the Mycobacterium tuberculosis dormancy regulon. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:18032–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartek IL, Rutherford R, Gruppo V et al. The DosR regulon of M. tuberculosis and antibacterial tolerance. Tuberculosis 2009; 89:310–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irwin SM, Gruppo V, Brooks E et al. Limited activity of clofazimine as a single drug in a mouse model of tuberculosis exhibiting caseous necrotic granulomas. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:4026–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harper J, Skerry C, Davis SL et al. Mouse model of necrotic tuberculosis granulomas develops hypoxic lesions. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.