Abstract

Objectives

Robustness of an existing meta-analysis can justify decisions on whether or not to conduct an additional study addressing the same research question. We illustrate the graphical assessment of the potential impact of an additional study on an existing meta-analysis using published data on statin use and the risk of acute kidney injury.

Study Design and Setting

A previously proposed graphical augmentation approach is used to assess sensitivity of current test- and heterogeneity statistics extracted from existing meta-analysis data. In addition, we extended the graphical augmentation approach to assess potential changes in the pooled effect estimate after updating a current meta-analysis and applied the three graphical contour definitions to data from meta-analyses on statins use and acute kidney injury risk.

Results

In the considered example data, the pooled effect estimates and heterogeneity indices demonstrated to be considerably robust to the addition of a future study. Supportingly, for some previously inconclusive meta-analyses, a study update might yield statistically significant kidney injury risk increase associated with higher statins exposure.

Conclusion

The illustrated contour approach should become a standard tool for the assessment of the robustness of meta-analyses. It can guide decisions on whether to conduct additional studies addressing a relevant research question.

Introduction

Given an existing meta-analysis, it is often of particular interest to determine whether conducting and adding a new study would change conclusions, or whether the existing evidence provides a definitive answer to the research question. In order to improve the quality and value of research being conducted, international collaborative groups such as the Evidence-Based Research Network and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group, are seeking tools either to qualify the discussion as to whether further studies are required or to communicate high quality evidence as “when further studies are unlikely to change the estimate” [1, 2]. Furthermore, when using meta-analyses as primary analysis method for the assessment of treatment effects based on consecutively conducted studies, for being time and cost effective, it is of particular interest to know if the initiation of another study to be included in an existing meta-analysis could relevantly change the actual results and conclusion. The idea of assessing justification for a new trial or study based on evidence syntheses has been widely discussed in literature [3–5]. In particular, it would be helpful to assess the potential impact of an additional study, by investigating the possible change in the pooled effect estimate, statistical significance and in the level of between-study variance of an existing meta-analysis. This would facilitate the implementation of valid stopping rules for usefulness and futility, the assessment of robustness of a meta-analysis as well as steer update prioritization of portfolios of systematic reviews and sample size calculations for the design of future studies added to an existing meta-analysis [6–7].

In a recent methodological research article, Langan and colleagues proposed [8] a graphical approach for assessing the impact of additional evidence on a meta-analysis based on contours for statistical significance of the pooled effect estimate and the estimated between study heterogeneity. While these statistics reflect aspects of stochastical uncertainty and dispersion, they do not allow for a meaningful interpretation from a clinical practice perspective. For instance, a new study may change the pooled effect towards statistical significance, yet the change may not be clinically relevant. On the other hand, an additionally conducted and added study may not yield into a significant pooled effect estimate but may considerably change magnitude or even direction of the effect measure. Further discussion on differences between clinical and statistical importance of changes in effect estimates can be found in literature [3, 12, 15].

In this article, we extend Langan’s approach to allow for a graphical assessment of the sensitivity of the pooled effect estimate of an existing meta-analysis with respect to the addition of a new single study.

We apply the contour graph method to real meta-analysis data on the effect of high-dose statins on the risk of acute kidney injury and illustrate the amount of ambiguity with respect to relevant effect and heterogeneity statistics when adding evidence of a subsequently conducted study.

Methods

Contour plot approach

As previously described by Langan and colleagues [8], contour plots can be used to display the impact of an additional study on the estimates of relevant model parameters. These graphical augmentations overlay and divide a funnel plot (displaying single point estimates on the x-axis and corresponding standard errors on the y-axis) into multiple regions. The regions show the potential impact that the additional study could have on important aspects of the analysis, in particular the statistical significance of the pooled meta-analysis effect estimate and the estimate of between-study heterogeneity.

We developed a routine to display these two contours, following the approach suggested by Langan et al. In addition, we implemented a third graph displaying contours of the change in the pooled effect estimate of an existing meta-analysis after adding results of a subsequently conducted new study.

The contours of statistical significance relate to the statistical test of null-effect of the pooled effect parameter of the updated meta-analysis. The contours show the magnitude of the effect and standard error for the potential additional study for which a certain predefined level of statistical significance of the pooled estimate from the updated meta-analysis would be exceeded. In fact, the contours define regions where the new study result must be located in order to reject the null-effect hypothesis at a desired level (usually 5%).

Studies of a meta-analysis differ inevitably in design, conduct and participants. To quantify the extent of this heterogeneity is therefore important because it determines the possible strength of conclusions drawn based on the results of the meta-analysis [9]. We chose the I2 statistic as the corresponding measurement for heterogeneity. The heterogeneity contours indicate the impact of an additional study on the estimate of between-study variance. The heterogeneity contours therefore display the two-dimensional location of an effect estimate and a standard error of a new study that would be required to move the I2 statistic to a specific pre-determined value. Four contours are displayed, three informative I2 values (determined by the I2 of the existing meta-analysis) and the last one relating to the current I2 value of the meta-analysis. Effect and standard error estimates of an additional study would increase the value of I2 if they are located inside the region encircled by the contour or decrease the value if they fall outside the contour lines.

It is of particular interest to predict the change in the overall effect estimate since it measures the strength of the association between the exposure factor and the outcome. Therefore, in addition to the two contour approaches for statistical significance and study heterogeneity, we implemented additional graphs displaying the change in the exposure effect parameter of interest. In particular we defined the following two contours for the change in the statins exposure associated excess of odds for acute kidney injury: less or equal than 50% and above 50%. Furthermore, we added contours for a null-effect OR of 1 and for the current pooled effect estimate.

These contour lines can be used to visualize the robustness of the current meta-analysis to the addition of a future study, since the result of a new study is generally expected to be in the same region as the previously included studies.

Data source and data extraction

In a recently published article, Dormuth et al. [10] conducted meta-analyses on the association between hospitalization for acute kidney injury and the use of high vs. low-potency statins in patients suffering from kidney disease. Outcome and exposure data from about two million patients aged 40 years and older being newly treated with statins were included in seven Canadian provincial databases (Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec and Saskatchewan) and two international databases (the United Kingdom and the United States). The results for the nine studies were pooled together in meta-analyses on the same health research question in different subpopulations. Daily statin doses were categorized as high or low according to their potency in lowering serum concentrations of low density lipoprotein cholesterol. There were four exposure duration categories: patients who were treated with statins for less or equal to 120 days, between 121 and 365 days, between 366 and 730 days and patients who were not exposed to statins within the first 120 days but after. Within these subgroups, the comparison of high potency versus low potency statins was conducted for patients with and without chronic kidney disease yielding a total of eight meta-analyses.

The point estimates (propensity score adjusted odds ratios) of each study were extracted from the figures provided in the article of Dormuth et al. [10]. However, since only confidence intervals were available, the R function optim [11] was used to derive estimates of the corresponding standard errors of the log odds ratios for each study.

Results

We denote SEls to be the standard error for the largest study and, similarly SEst for the standard error of the smallest study of each meta-analysis. Unlike Langan’s contour plots, our proposed graphs are displayed with larger standard errors at the top of the graph and the different contours correspond to the different impacts that the study can have on the summary statistics of the meta-analysis. For the purposes of brevity, graphical representations of the analysis results are only displayed for the four meta-analyses on patients with chronic kidney disease (see Figure 2 supplementary material for the contour plots referring to the four meta-analyses in patients without kidney disease). However, for all eight meta-analyses, potential relevant changes of effect and heterogeneity estimates are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Current meta-analysis summary statistics (represented by index numbers) and their potential changes according to the contour method (indicated by arrows as described below) for the eight meta-analyses on statins exposure and risk of acute kidney injury conducted by Dormuth et al. [10]

| Overall effect estimate (Odds Ratio [95%CI]) | Statistical significance (p-value) | Heterogeneity index (I2 in %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A 1.11 [0.99;1.24] | E 1.34 [1.25;1.43] | A0.07 ↘ |

E <0.01 | A32 ↗ |

E30 ↗ |

| B 1.08 [0.96;1.22] | F 1.11[1.04;1.19] | B0.19 ↘ |

F <0.01 | B 0 | F 0 |

| C 1.04 [0.92;1.18] | G 1.15 [1.09;1.22] | C 0.5 | G <0.01 | C 0 | G 0 |

| D 1.16 [0.85;1.57] | H 1.06 [0.98;1.15] | D 0.35 | H 0.12 | D49 ↗ |

H 0 |

Arrows indicate defined* relevant possible changes of the corresponding summary statistic:

Change in the overall effect estimate (OR) that would alter excess odds by more than 50% (↗ or ↘)

Change in the statistical significance of overall effect estimate: from p≥0.05 to p<0.05 (↘) from p<0.05 to p≥0.05 (↗)

Absolute change in I2 heterogeneity index of >20% (↗)

A: Patients with chronic kidney disease exposed with statins for less than 120 days of current therapy

B: Patients with chronic kidney disease exposed with statins between 120 days and 365 days of current therapy

C: Patients with chronic kidney disease exposed with statins between 365 days and 730 days of current therapy

D: Patients with chronic kidney disease not exposed to statins within the first 120 days but after

E: Patients without chronic kidney disease exposed with statins for less than 120 days of current therapy

F: Patients without chronic kidney disease exposed with statins between 120 days and 365 days of current therapy

G: Patients without chronic kidney disease exposed with statins between 365 days and 730 days of current therapy

H: Patients without chronic kidney disease not exposed to statins within the first 120 days but after

Overall effect estimate

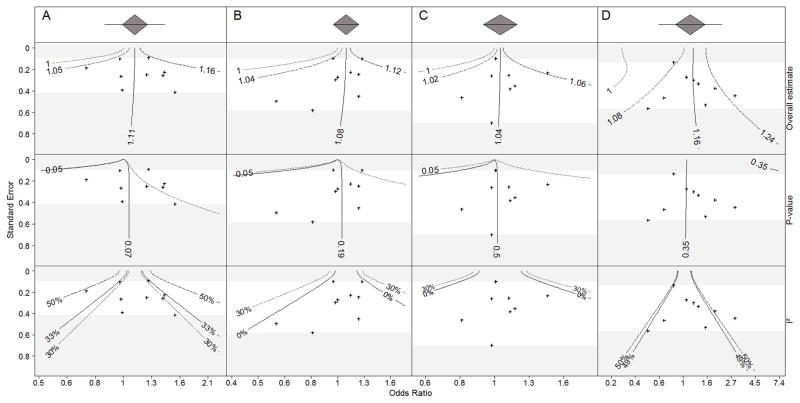

The first row panel of Figure 1 embed our proposed contour plots for the overall effect estimates for the four meta-analyses on high versus low potency statins in chronic kidney disease patients. Although in most instances the null effect contour is close to the contour that displays a 50% reduction in excess odds, a study that could change the direction of the estimated overall effect would need to be located apart from the other studies with respect to both the effect estimate and the standard error.

Figure 1. Contour plot analyses for the four meta-analyses (A to D) on hospitalization for acute kidney injury in patients with chronic kidney disease after receiving low potency or high potency statins. Odds ratio values > 1 indicate a risk increase associated with higher potencies of statins.

First row panel: odds ratio (OR) estimate contour; the solid line depicts those coordinates of a new study that would reveal the same OR as derived by the nine currently included studies. The dashed lines represent coordinates of a new study which lead to a decrease or increase of the excess odds of 50%. The dotted line represents coordinates of a new study which would lead to an estimated null treatment effect (OR=1).

Second row panel: statistical significance contour; the solid line depicts those coordinates of a new study that would reveal the same p-value for the pooled effect estimate as derived by the nine currently included studies. The dashed lines represent coordinates of a new study which lead to a p-value of 0.05 and therefore divide the plot into significance and non-significance regions.

Third row panel: heterogeneity contour based on the inconsistency index (I2), the solid lines depict those coordinates of a new study that would reveal the same I2 value as derived by the nine currently included studies. Dashed lines (if representable) depict I2 values of 30% and 50%.

Overlapping of contours: On the left side of column panel A, the p-value dotted line for the 0.05 level is overlapped by the solid line for the 0.07 level.

Absence of contours: On the plot D, contours for 0.05 p-value and 30% I2 are missing because it is not possible that this new meta-analysis get significant and that its heterogeneity decreases until 30%. For plots B and C, contours for 50% I2 are not displayed for a better readability and avoid overlapping of contours.

Statistical significance

The plots in the second row panel of Figure 1 show the impact of a potential study on the statistical significance of the overall effect estimate. The plots for the meta-analyses A and B (first and second column, Figure 1) indicate a wide region of potential study outcomes (to the right of the last contour) that would lower the statistical significance of the effect estimate to a value below 0.05, For example, using the current data, the estimated log odds ratio for meta-analysis A (patients treated for fewer than 120 days) is not statistically significantly different from 0 (p=0.07). To establish a statistically significantly higher risk of hospitalization for patients who were treated with high potency statins, the odds ratio a new study would have to be higher than 1.11 with standard error equal to SElt or higher than 1.73 for an additional study with standard error equal to SEst.

Similarly, in Table 1, the estimated treatment effect from meta-analysis B (patients treated for between 120 and 365 days) is not statistically significantly different from null (p=0.19). To be able to observe a statistically significantly higher risk of hospitalization for high potency statins, for an additional study with standard error equal to SElt, the odds ratio would have to be larger than 1.22.

Table 1 shows that the current p-value for the C meta-analysis is 0.5, which indicates very little evidence against the null hypothesis. However, one could observe a statistically significant pooled effect estimate indicating a higher risk of hospitalization for high potency statins if a study with standard error equal to SElt yielded an odds ratio larger than 1.3.

In Figure 1, the current D meta-analysis is also not statistically significant (p=0.35). In contrast to the first three meta-analyses, however, the contours for a statistically significant overall effect at level 0.05 are not even present on the graph. Therefore it is very unlikely that even with a large study with the pooled effect estimate of the updated meta-analysis would become statistically significant.

Heterogeneity

The plots in the third row panel of Figure 1 show the effect of an additional study on the estimate of between study heterogeneity, I2. For meta-analyses A and D, no plausible additional study result would reduce the estimate of I2 below 32% and 50% respectively, regardless of the value of the effect estimate or the standard error. For meta-analyses B and C, the current meta-analyses yield I2 estimate of 0%. The contours show that it is quite unlikely that one would observe a study that would change the I2 estimate from 0% for meta-analysis C, whereas it is quite plausible that one would estimate some level of heterogeneity in meta-analysis B upon observing data from an additional study.

Discussion

The contours method used for assessing the impact of future study data on an existing meta-analysis was applied to data on statins use and acute kidney injury in order to determine whether inclusion of a future tenth study was justified or not. The potential impact was evaluated and illustrated for the pooled effect estimate, statistical significance and heterogeneity, according to a wide range of possible effect estimates and standard errors that the additional study might have.

These contour graphs provide regions where the estimate and standard error of a new study would have to lie in order to warrant clinically relevant and statistically significant conclusions from the updated meta-analysis. We stress that the choice of increments for the effect estimate contours depends on the context of the studies being considered in the meta-analysis (e.g. type and clinical relevance of the outcome, range of previously observed and expected effect sizes). We suggest that, in contrast to contours for p-values for formal hypothesis tests, contours for effect sizes should be ideally not considered as strict rejection boundaries but rather reviewed as a continuous scale for the assessment of clinical relevance.

The illustrative example in this article is based on observational data. It is commonly accepted that the potential for bias in effect estimation is larger in non-randomised studies. However, meta-analyses can get close to the results of RCTs if selection bias can be excluded, all potential confounding variables are measured and sophisticated confounder-adjustment procedures are employed. The design and statistical analysis approach of the cohort studies included in the example meta-analyses, at their best, aimed to fulfill these conditions.

There are some further limitations which have been already widely discussed in previous work: although the choice of the statistical model (fixed or random effects) should not exclusively rely on the observed data, changes in the statistical model choice may occur after including a new study. The funnel plot approach, however, does not enable automated handling of such situations so that manual review of results and subsequent reconsideration of model choice is required. Moreover, the method could potentially be improved by estimating the between-study variance (τ2) with a Bayesian approach instead of the used Dersimonian and Laird method. The Bayesian approach is more sophisticated because it allows incorporation of uncertainty in the estimation of all parameters, including τ2 [12, 13]. However, the main problem with the Bayesian approach is the need to specify a prior distribution for the parameters of interest. The contour graphs could then also be extended by illustrating the impact of the new study on the confidence interval of the overall random effect estimate of the meta-analysis. It would be of particular interest to examine how the width of a random effects confidence interval and prediction interval increases or decreases according to a new study’s effect estimate and standard error. For the fixed effects approach, corresponding contours for confidence interval limits and widths have been proposed previously [15]. Earlier proposals of clinical equivalence contours incorporate formal test results such as changes in p-values for pooled effect estimates [15]. The contours extension suggested within this work reflects potential changes in effect estimates and purposively disregards aspects of statistical significance.

The proposed method focuses on the inclusion of evidence from only one additional study on the meta-analysis but not for multiple additional studies. Generalizing this approach to the addition of multiple studies would need more assumptions, such as adjustment of p-value for multiple sequential testing [15]. For example, previous work by Yosuf and Pogue [16], and subsequently by Wetterslev et al. [17] and Thorlund et al. [18] suggested building monitoring boundaries for cumulative meta-analysis and determining the optimal information size. These boundaries control for random error in case of multiple testing when sequentially accumulating data and mainly address the problem of spurious effect determination induced by early significance testing at inappropriate cumulative sample size.

Finally, conclusions based on the contour plot approach can become difficult if different clinical outcomes have to be simultaneously considered. Sophisticated methods need to be developed to help summarise information across multiple outcomes.

Langan’s approach and its extension to point-estimate contours being illustrated in this article represent an exploratory toolkit to visualize the sensitivity of all relevant meta-analysis statistics. Due to its straightforward implementability and interpretation, the contour plot method should become a standard tool for the assessment and reporting of the robustness of meta-analyses. We suggest that future versions of the extfunnel functions in R and Stata should be extended to include the effect size contours as proposed in this article. With this article, we provide a brief tutorial on how to apply the contour plot approach to meta-analysis data using the statistical software package R (online supplemental material).

The discussed approach can effectively guide decisions on whether or not to initiate additional evidence-contributing studies in a wide range of research areas with controversial or inconclusive state of evidence.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Chalmers I, Nylenna M. A new network to promote evidence-based research. The Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1903–1904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [last accessed April 13, 2015]; Web-url: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org.

- 3.Ferreira ML, Herbert RD, Crowther MJ, Verhagen A, Sutton AJ. When is a further clinical trial justified? BMJ. 2012;345:e5913. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takwoingi Y, Hopewell S, Tovey D, Sutton AJ. A multicomponent decision tool for prioritising the updating of systematic reviews. BMJ. 2013;347:f7191. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutton AJ, Cooper NJ, Jones DR. Evidence synthesis as the key to more coherent and efficient research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;(9):29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roloff V, Higgins JPT, Sutton AJ. Planning future studies based on the conditional power of a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2013;32:11–24. doi: 10.1002/sim.5524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowther MJ, Hinchliffe SR, Donald A, Sutton AJ. Simulation-based sample-size calculation for designing new clinical trials and diagnostic test accuracy studies to update an existing meta-analysis. Stata J. 2013;13:451–473. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langan D, Higgins JP, Gregory W, Sutton A. Graphical augmentations to the funnel plot assess the impact of additional evidence on a meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(5):511–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dormuth CR, Hemmelgarn BR, Paterson JM, James MT, Teare GF, Raymond CB, et al. Use of high potency statins and rates of admission for acute kidney injury: multicenter, retrospective observational analysis of administrative databases. BMJ. 2013;346:f880. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.‘stats’ package, R software, R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. URL http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton AJ, Cooper NJ, Jones DR, Lambert PC, Thompson JR, Abrams KR. Evidence-based sample size calculations based upon updated meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2007;26(12):2479–500. doi: 10.1002/sim.2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2009;172(1):137–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowther MJ, Langan D, Sutton AJ. Graphical augmentations to the funnel plot to assess the impact of a new study on an existing meta-analysis. Stata J. 2012;12(4):605–622. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Whitehead A, Simmonds M. Sequential methods for random-effects meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2011;30:903–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pogue J, Yusuf S. Overcoming the limitations of current meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The Lancet. 1998;351(9095):47–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2008;61(1):64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorlund K, Devereaux PJ, Wetterslev J, Guyatt G, Ioannidis JPA, Thabane L, Gluud L, Als-Nielsen B, Gluud C. Can trial sequential monitoring boundaries reduce spurious inferences from meta-analyses? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38(1):276–286. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.