Abstract

Socioeconomically disadvantaged cancer survivors are less likely to have adequate follow-up care. In this study, we examined whether socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors are at risk for not having follow-up care discussions with providers, a critical determinant of access to follow-up care and desirable health outcomes. Using the 2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and Experiences with Cancer Survivorship Supplement, we used a binary logit model with sample weights to examine associations between 1,320 cancer survivors’ socioeconomic status (SES) and reports of follow-up care discussions with providers, controlling for clinical and demographic characteristics. The multivariable model indicated survivors with incomes ≤200% Federal Poverty Level (FPL) had a lower probability of reporting a follow-up care discussion than survivors with incomes >400% FPL (p<.05). Survivors with <high school education had a lower probability of reporting a discussion than survivors who had a college education (p<.05). However, even after controlling for income, survivors with financial hardship had a greater probability of reporting a discussion than survivors with no financial hardship (p<.05). Insurance status was not a significant predictor of reporting a discussion (p>.05). Socioeconomically disadvantaged cancer survivors are at risk for not having follow-up care discussions with providers, particularly those who report lower income and education. Development of educational interventions targeting provider communication with socioeconomically disadvantaged cancer survivors, and survivors’ understanding of the benefits of follow-up care discussions, may promote access to these services. Future research assessing mechanisms underlying relationships between survivors’ SES indicators and reports of follow-up care discussions with providers is also warranted.

Introduction

The number of cancer survivors is growing rapidly in the United States; by 2024 it is expected to reach almost 19 million [1]. As more people survive cancer due to treatment improvements, ensuring appropriate, high-quality follow-up care has become a priority. At a minimum, follow-up care for cancer involves regular medical visits in order to address late and long term effects of treatment and surveillance for early detection of recurrence or new malignancies [2]. The provision of follow-up care after cancer treatment has been strongly endorsed by national guidelines, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology [3], National Comprehensive Cancer Network [4], and the American Cancer Society [5]. However, prior research indicates that survivors with low socioeconomic status (SES; i.e., income, education, insurance, financial hardship) often do not receive adequate follow-up care [6, 7], health care professionals often fail to provide appropriate care to uninsured survivors [8], and survivors covered by public insurance (e.g. Medicaid) report poorer quality follow-up care [9]. Evidence also suggests that socioeconomically disadvantaged cancer survivors experience poorer health outcomes than higher-SES survivors [10].

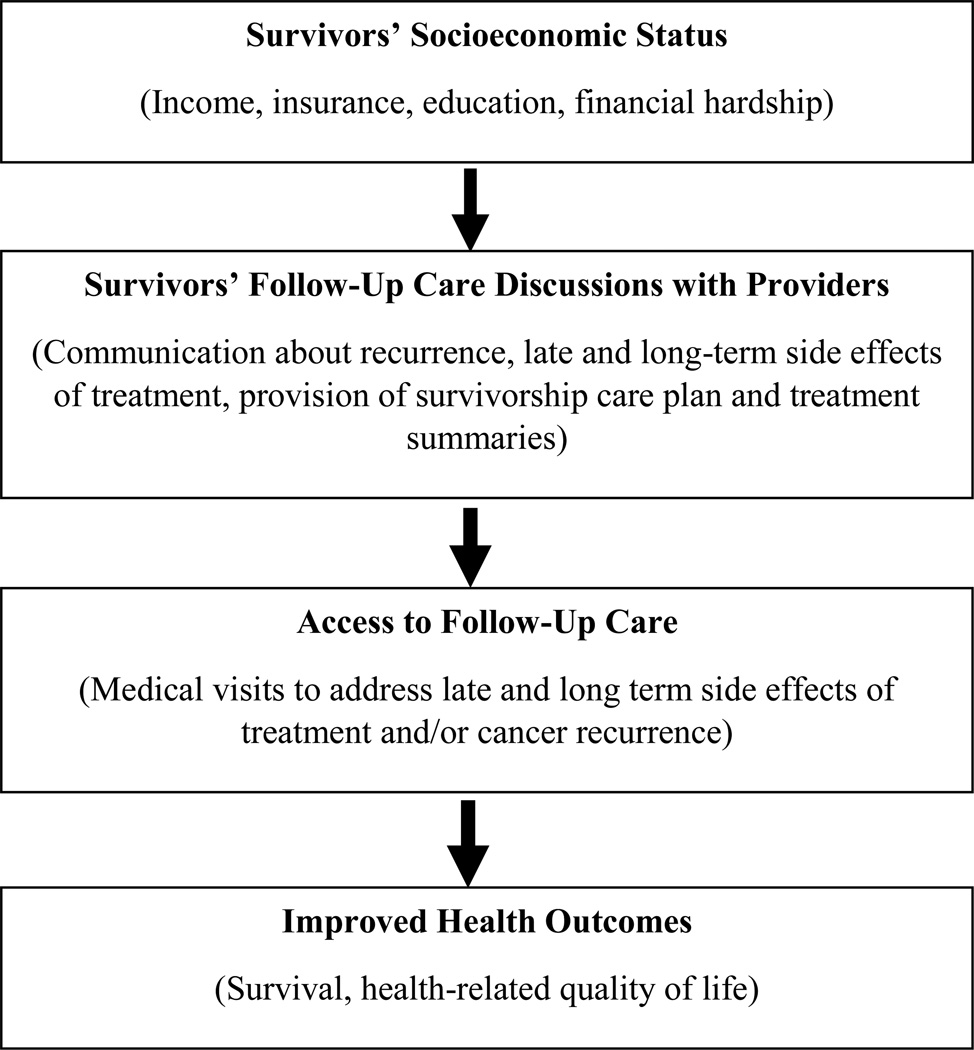

Discussions about follow-up care between providers and survivors should ideally occur after cancer treatment is complete to provide information and advice about late and long-term effects of treatment the survivor may experience, risk of recurrence, and surveillance for recurrence or new cancers. All providers should have discussions about follow-up care even though the provider responsible for delivering follow-up care, and extent of follow-up care, may vary depending on the survivors’ risk profile and medical needs. Many recommendations suggest that, during the discussion, written documents such as a survivorship care plan or treatment summary should be provided to the patient [2]. These discussions are thought to promote access to follow-up care by clarifying care recommendations and division of care responsibilities among follow-up care providers (e.g. oncologists, primary care providers, specialists), and educating survivors about the kind of follow-up care they should seek and providers about what kind of care they should provide to survivors. Prior research indicates that survivors who had follow-up care discussions were more likely to receive follow-up care [11] and rate their follow-up care as higher quality [9]. As such, follow-up care discussions have the potential to promote access to follow-up care for socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors. However, socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors may also be at risk for not having follow-up care discussions with their providers because either the provider or survivor may assume that the cost of the follow-up care recommended during follow-up care discussions (e.g. surveillance screening and other non-cancer care) and related non-medical expenses (e.g. transportation, childcare) is prohibitive [12, 13]. Providers may also assume that socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors are not capable of understanding complex information and therefore forgo a discussion about follow-up care [14]. Whether or not socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors are truly at risk for not having follow-up care discussions with their providers, a critical determinant of access to follow-up care and desirable health outcomes, is unclear. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptualized relationship between SES, follow-up care discussions, access to follow-up care, and survivors’ health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Relationship between SES, Follow-Up Care Discussions, Access to Follow-Up Care, and Survivors’ Health Outcomes (adapted from the National Cancer Institute’s patient-centered communication framework)[14]

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between cancer survivors’ SES and reports of follow-up care discussions with providers. To the extent that SES does not influence follow-up care discussions with providers, follow-up care discussions may be a high-leverage method of increasing access to follow-up care for socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors.

Methods

Data Source and Sample

The study sample was drawn from the 2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS)-Household Component Full-Year Consolidated Files and Experiences with Cancer Survivorship Supplement (ECSS). Briefly, the MEPS data are a publically available data source and nationally representative survey of families and individuals’ healthcare utilization and expenditures in the United States civilian, non-institutionalized population. In 2011, the Household Component was supplemented with responses from the ECSS – a paper-based, self-administered survey of cancer survivors. This survey was developed in conjunction with the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and American Cancer Society to ask participants about the burden of cancer, lasting effects of the disease, financial impacts, and employment outcomes for cancer survivors and their families [15]. The 2011 ECSS sample consisted of 1,419 adult cancer survivors aged 18 years or older. Cancer survivors were identified based on responses to the following question in the survey: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had cancer or a malignancy of any kind?” The overall MEPS response rate in 2011 was 54.9%, and the ECSS was 90%. After excluding survivors who were missing data on whether they reported a follow-up care discussion with their provider (n=72) and whether they reported financial hardship (n=27) the final study sample included 1,320 cancer survivors.

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Several independent variables were used to capture SES based on common indicators identified in the literature [16], including insurance status (public, private, or uninsured), adjusted family income as percent of federal poverty level (FPL), and years of education. In addition, a measure of whether participants experienced “financial hardship”, indicated by answering “yes” or "no” to ever being unable to cover their share of the costs of medical visits due to cancer in the ECSS survey was also included in the model.

Follow-Up Care Discussions

The outcome variable was a self-reported response to a question which asked survivors if their doctor or other healthcare provider ever discussed regular follow-up care and monitoring after completing treatment for their cancer. This variable is composed of four response categories: (1) discussed it with me in detail, (2) briefly discussed it with me, (3) did not discuss it with me at all, (4) I don’t remember. Since the focus of the study was on whether a survivor reported any discussion of follow-up care, rather than on the quality of the discussion, this variable was collapsed and recoded to be dichotomous (i.e., “yes” [discussed it with me in detail or briefly discussed it with me] or “no” [i.e. did not discuss it with me at all or I don’t remember]).

Control Variables

The following clinical and demographic characteristics were included in the model because they were likely correlated with SES and reports of follow-up care discussions: rural versus urban (based on residence in a Metropolitan Statistical Area), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White or minority), gender, marital status, age, cancer type, and years since last cancer treatment. Comorbidities were assessed based on survivors’ response to whether doctor or other health professional ever told the survivor whether he or she had any MEPS priority conditions (excluding cancer). The total number of priority conditions were summed for each survivor.

Statistical Analysis

Population proportions were estimated for all variables for the overall study sample and according to whether a follow-up care discussion was reported. Unadjusted relationships between each of the variables and the outcome variable were estimated using the Chi-square statistic. For our adjusted analysis, we used a binary logit model with sample weights to assess multivariable associations between SES (i.e. income, education, insurance, and financial hardship) and probability of reporting follow-up care discussions with the provider. Beta coefficients and average marginal effects were calculated for all variables. The Variance Inflation Factor values were examined and indicated there was not substantial multicollinearity in the data (i.e. all variables were <10). In addition, the pairwise correlation between family income as percent of FPL and financial hardship indicated a weak linear relationship (Pearson’s r=.11), thus both variables were retained in the model. A two-sided p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. All data were analyzed using Stata 13 (College Park, TX) and accounted for the complex survey design to obtain nationally representative estimates generalizable to the civilian, non-institutionalized population.

Results

Sample characteristics

When combining the two surveys, our final sample was 1,320. One-quarter of cancer survivors had adjusted family incomes below 200% of the FPL, yet only 12% of survivors reported having financial hardship. Nearly one-third of survivors had either public insurance (24%) or were uninsured (4%). Over half had at least some college education (53%), while only 11% had less than a high school education. (Table 1). Overall, 86% of cancer survivors reported having a follow-up care discussion with their provider. Over half of survivors (61%) reported discussing follow-up care in detail, 23% reported discussing follow-up care briefly, and 14% either did not report a discussion or did not remember (data not shown).

Table 1.

Unadjusted analysis of determinants of reporting a follow-up care discussion with a healthcare provider (n=1,320), population weighted estimates

| Clinical and Demographic Characteristics |

Total Study Sample (%) | Did Not Report Follow- Up Care Discussion (%) |

Reported Follow-up Care Discussion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. of Survivors† | 1,320 | 205 | 1,115 |

| Years of Education* | |||

| ≥16 years | 36 | 21 | 38 |

| ≥12 – < 16 years | 53 | 60 | 52 |

| <12 years | 11 | 19 | 9 |

| Family Income (% FPL)* | |||

| >400% | 47 | 31 | 50 |

| 200–400% | 28 | 33 | 27 |

| <200% | 25 | 36 | 23 |

| Financial Hardship | |||

| No | 88 | 92 | 88 |

| Yes | 12 | 8 | 12 |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 72 | 66 | 73 |

| Public | 24 | 31 | 23 |

| Uninsured | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Age* | |||

| <55 | 23 | 20 | 24 |

| ≥55–<65 | 24 | 19 | 25 |

| ≥65–<75 | 27 | 22 | 28 |

| ≥75 | 26 | 39 | 23 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 44 | 43 | 44 |

| Female | 56 | 57 | 56 |

| Race | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 90 | 89 | 90 |

| Minority | 10 | 11 | 10 |

| Rural | |||

| No | 82 | 83 | 82 |

| Yes | 18 | 17 | 18 |

| Marital Status* | |||

| Not Married | 40 | 53 | 38 |

| Married | 60 | 47 | 62 |

| MEPS Priority Conditions‡ | |||

| 0 Conditions | 16 | 11 | 16 |

| 1 Condition | 17 | 15 | 18 |

| 2–8 Conditions | 67 | 74 | 66 |

| Cancer Type* | |||

| Breast | 15 | 5 | 16 |

| Prostate | 13 | 6 | 14 |

| Lung | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Colorectal | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| Hematologic | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Gynecologic | 10 | 14 | 10 |

| Other | 51 | 62 | 49 |

| Treatment Status* | |||

| <5 years posttreatment | 35 | 24 | 37 |

| ≥5 years posttreatment | 40 | 43 | 40 |

| Never treated/Missing | 25 | 32 | 23 |

Value given is number rather than percent.

p<.05

MEPS priority conditions include arthritis, asthma, diabetes, emphysema, heart disease (angina, coronary heart disease, heart attack, other heart condition/disease), high cholesterol, hypertension, and stroke.

Relationship between SES and Follow-Up Care Discussions

The unadjusted analysis indicated that, survivors who had lower family incomes (e.g. < 200% of the FPL, 23%) and fewer years of education (e.g. <12 years, 9%) were significantly less likely report a follow-up care discussion than survivors with higher family incomes (e.g. >400% of the FPL, 50%) and more years of education (e.g.≥16 years, 38%), respectively (all p<.05). However, financial hardship and insurance status were not significantly associated with reporting a follow-up care discussion (Table 1).

The coefficients and average marginal effects from the adjusted logit model controlling for demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2. Consistent with the unadjusted analysis and our hypotheses, family income and years of education were significant predictors of reporting a follow-up care discussion (p<.05). On average, survivors with family incomes less than 200% of the FPL had a 6% lower probability of reporting a follow-up discussion than survivors with incomes >400% of the FPL (p<.05). In contrast to the unadjusted analysis and in stark contrast to our hypothesis, on average, survivors who reported financial hardship (i.e. inability to pay medical bills) had a nearly 7% greater probability of reporting a follow-up care discussion than survivors without financial hardship, even after controlling for income level (p<.05). Years of education were also a significant predictor of reporting a discussion about follow-up care with the provider. On average, survivors who had a less than a high school education had a 11% lower probability of reporting a follow-up care discussion than survivors who had a college education or greater (e.g. ≥16 years) (p<.05). Likewise, on average, survivors who had only some college education had a 6% lower probably of reporting a follow-up care discussion than survivors who had a college education or greater (p<.05).

Table 2.

Binary logit model regression estimation results: Beta coefficients and average marginal effects of reporting follow-up care discussions with providers

| Variables | Beta Coefficient (Standard Error) |

Average Marginal Effect (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Education (≥16 years = referent) | |||

| ≥12–<16 years | −0.63* (0.27) |

−6.1* | |

| <12 years | −1.01* (0.32) |

−11.1* | |

| Income (% FPL) (>400% FPL=referent) | |||

| 200–400% | −0.35 (0.29) |

−3.5 | |

| <200% | −0.56* (0.28) |

−6.1* | |

| Financial Hardship (No=referent) | 0.74* (0.30) |

6.6* | |

| Insurance (Private Only = referent) | |||

| Public Only | 0.18 (0.24) |

1.9 | |

| Uninsured | 0.26 (0.45) |

2.7 | |

| Age (<55 years= referent) | |||

| ≥55–<65 years | −0.26 (0.33) |

−2.5 | |

| ≥65–<75 years | −0.11 (0.32) |

−1.0 | |

| ≥75 years | −0.68* (0.31) |

−7.6* | |

| Gender (Male=referent) | 0.04 (0.26) |

0.5 | |

| Race (White, non-Hispanic=referent) | −0.01 (0.29) |

−0.1 | |

| Rural (Urban = referent) | 0.25 (0.27) |

2.6 | |

| Marital Status (Not Married = referent) | 0.43 (0.24) |

4.7 | |

| MEPS Priority Conditions (0 Conditions=referent)† | |||

| 1 Condition | −0.11 (0.38) |

−1.1 | |

| 2–8 Conditions | −0.22 (0.29) |

−2.3 | |

| Cancer Type (Other=referent) | |||

| Breast | 1.83* (0.32) |

14.3* | |

| Prostate | 1.11* (0.36) |

10.8* | |

| Lung | 0.10 (0.67) |

1.3 | |

| Colorectal | 0.49 (0.45) |

5.7 | |

| Hematologic | 0.49 (0.50) |

5.8 | |

| Gynecologic | −0.05 (0.30) |

−0.6 | |

| Treatment Status (<5 years posttreatment=referent) | |||

| ≥5 years posttreatment | −0.63* (0.27) |

−6.1* | |

| Never treated/Missing | −0.82* (0.27) |

−8.5* | |

| _cons | 2.80* (0.43) |

||

p < 0.05

MEPS priority conditions include arthritis, asthma, diabetes, emphysema, heart disease (angina, coronary heart disease, heart attack, other heart condition/disease), high cholesterol, hypertension, and stroke.

Survivors with public insurance or who were uninsured, on average, had slightly higher probabilities of reporting a follow-up care discussion compared to survivors who had private insurance, but these findings were not significant.

Discussion

Using a nationally representative sample of cancer survivors, we examined the relationship between SES and reports of follow-up care discussions with health care providers. Overall, as hypothesized, we found that socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors are at risk for not having follow-up care discussions with their providers. These findings are consistent with extant research which shows cancer survivors who are lower-income are less likely to receive appropriate follow-up care [6]. This may be due to our finding that lower-income survivors are less likely to have follow-up care discussions than higher-income survivors among other factors. Numerous studies have also shown that survivors with lower educational levels are more likely to report suboptimal communication with providers [17] and inadequate follow-up care and monitoring than more highly educated survivors [6]. This is consistent with our finding that survivors with less than a college education are less likely to have follow-up care discussions than survivors with a college education or greater.

We expected survivors who reported financial hardship to be less likely to report a follow-up care discussion due to concerns about the cost of follow-up care. However, we found that survivors who reported financial hardship (indicated by answering “yes” to ever being unable to cover their share of the costs of medical visits due to cancer) were more likely to report a discussion about follow-up care. One possible explanation for this finding is that survivors’ family income and financial hardship are conceptually distinct constructs, which is reflected by the finding they were only weakly correlated in our analysis. In particular, income measurement in MEPS is relatively objective, while financial hardship is more subjective. For example, survivors who report financial hardship may not value survivorship care services and therefore view these costs as difficult to cover. These survivors might be considered less “activated” in their survivorship care (i.e., understand one’s own role in the care process and possessing the knowledge, skills, and confidence to take on that role) [18], and as such, providers may consider them as targets for intervention by initiating follow-up care discussions. Similarly, survivors’ financial hardship may offer more of a cue to discussing follow-up care than survivors’ income because it is more visible to providers. Thus, providers may proactively initiate follow-up care discussions with survivors they perceive are unable to meet healthcare expenses to prevent future health problems that could contribute to more financial hardship. Conversely, survivors who are unable to meet healthcare expenses may also be proactive in communicating this to their provider and initiating follow-up care discussions for similar reasons. However, these are unlikely explanations given prior research indicating providers’ and patients lack of discussion about costs of care in making decisions about cancer care [19, 20]. Future cancer survivorship research could benefit by examining the role financial hardship plays in delivery of follow-up care in addition to common socioeconomic indicators.

The finding that insurance status was not associated with reporting a follow-up care discussion was also surprising. Although insurance has been identified as an important financial factor for receiving high quality cancer treatment, providers and survivors may be unaware of the costs for survivorship care, and patients may move forward with care regardless of payment by the insurer [20]. Additionally, this finding may relate to how MEPS collects data on insurance: Participants are asked their insurance status at the time of the survey, which may not coincide with their cancer episode. Thus, the variable used may not be a relevant indicator of the survivors’ insurance status when receiving follow-up care for their cancer.

This study had several limitations. First, cancer stage at diagnosis was not included in the model as a covariate because these data are not captured in MEPS, thus potentially leading to biased estimates. This is an important consideration since cancer stage could be associated with whether or not a provider decides to discuss follow-up care, which assumes treatment ends at some point. Regardless of cancer type, a provider may perceive the need to discuss follow-up care for a survivor treated for a Stage IV cancer to be less of a priority than a survivor who has completed an initial course of treatment for an early-stage cancer, since survivors with advanced disease who completed treatment may still have active or incurable disease [21]. Second, the self-administered nature of MEPS may have resulted in inaccurate or underestimated responses of financial variables (i.e. income and financial hardship) due to the sensitive nature of these data. Third, depending how on how many years had passed since cancer treatment was completed, survivors’ recollection of whether a follow-up care discussion occurred may have been inaccurate. However, due to this possibility of recall bias for reporting a follow-up care discussion, our study addresses this potential issue by including time since last cancer treatment as a covariate in the model. Fourth, this study did not examine whether SES indicators were associated with quality of follow-up care discussions (i.e. discussed it with me in detail, briefly discussed it with me). Lastly, since the CSAQ survey was administered only in 2011, this analysis was cross-sectional, and thus the ability to determine a causal relationship between SES and report of a follow-up care discussion is limited.

Despite these limitations, our study has important implications. Cancer survivors are at increased risk for unemployment, debt, and income strains post-treatment even if they are insured [19, 22, 23] and as our results and others have demonstrated, there are many socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors who might benefit from follow-up care discussions. As such, we need to ensure that the growing number of socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors and those experiencing financial hardship have access to follow-up care, which may be promoted by regular discussions about follow-up care between survivors and providers.

Conclusion

The results of this analysis using a sample of cancer survivors from the MEPS dataset found significant associations between SES and the probability of reporting a follow-up care discussion with a provider. The findings from this study increase our understanding of the determinants of cancer survivors’ discussions with providers about follow-up care and can inform educational interventions for improving the dissemination and provision of survivorship care planning services. This could be accomplished by developing trainings or toolkits to improve provider communication with socioeconomically disadvantaged survivors and educational materials to promote survivors’ understanding of the benefits of follow-up care discussions. Routine delivery of survivorship care plans with its associated discussion may also help close this gap. Additional research evaluating the effectiveness of strategies for increasing the uptake of survivorship care services and examining the role of follow-up care discussions on receipt of cancer (and non-cancer) medical care, and subsequent survivors’ health outcomes, is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Marisa Domino, PhD for her feedback on the manuscript.

Funding: Ms. DiMartino’s effort was funded by grant number 5 R25 CA057726 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Ethical Standards:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Lisa D. DiMartino, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1103E McGavran-Greenberg, 135 Dauer Drive, Campus Box 7411, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7411, Phone: (919) 491-4767, Fax: (919) 843-6308, dimartin@email.unc.edu.

Sarah A. Birken, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7411, birken@unc.edu.

Deborah K. Mayer, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carrington Hall #7460, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7460, dmayer@unc.edu.

References

- 1.Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures. [ http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/survivor-facts-figures] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt ME, Ganz P Institute of Medicine (U.S.), American Society of Clinical Oncology., American Society of Clinical Oncology and Institute of Medicine Symposium on Cancer Survivorship. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, Reaman GH, Tyne C, Wollins DS, Hudson MM. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:631–640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Survivorship, version 1.2013. [ www.nccn.org] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center Systems Policy and Practice: Clinical Survivorship Care Overview. Washington, D.C.: The George Washington Cancer Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aziz NM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivorship research among ethnic minority and medically underserved groups. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:789–801. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.789-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer NR, Weaver KE, Hauser SP, Lawrence JA, Talton J, Case LD, Geiger AM. Disparities in barriers to follow-up care between African American and White breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2706-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlesinger M, Dorwart RA, Epstein SS. Managed care constraints on psychiatrists' hospital practices: bargaining power and professional autonomy. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:256–260. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, Clauser SB, Oakley-Girvan I. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor's perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1280–1289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baquet CR, Commiskey P. Socioeconomic factors and breast carcinoma in multicultural women. Cancer. 2000;88:1256–1264. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000301)88:5+<1256::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Earle CC. Associations among cancer survivorship discussions, patient and physician expectations, and receipt of follow-up care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2577–2583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Aziz NM. Forgoing medical care because of cost: assessing disparities in healthcare access among cancer survivors living in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116:3493–3504. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson HS, Littles M, Jacob S, Coker C. Posttreatment breast cancer surveillance and follow-up care experiences of breast cancer survivors of African descent: an exploratory qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29:478–487. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr . Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. NIH Publication No. 07-6225. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. 2011 [ http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/household.jsp.]

- 16.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, Posner S. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294:2879–2888. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen JD, King AJ, Guntzviller LM, Davis LA. Patient-provider communication and low-income adults: age, race, literacy, and optimism predict communication satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zafar SY, Tulsky JA, Abernethy AP. It's time to have 'the talk': cost communication and patient-centered care. Oncology (Williston Park) 2014;28:479–480. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peppercorn J. The financial burden of cancer care: do patients in the US know what to expect? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14:835–842. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.963558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer DK, Green M, Check DK, Gerstel A, Chen RC, Asher G, Wheeler SB, Hanson LC, Rosenstein DL. Is there a role for survivorship care plans in advanced cancer? Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:2225–2230. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2586-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitney RL, Bell JF, Reed SC, Lash R, Bold RJ, Kim KK, Davis A, Copenhaver D, Joseph JG. Predictors of financial difficulties and work modifications among cancer survivors in the United States. J Cancer Surviv. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0470-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Jr, Banegas MP, Davidoff A, Han X, Virgo KS, McNeel TS, Chawla N, Blanch-Hartigan D, et al. Financial Hardship Associated With Cancer in the United States: Findings From a Population-Based Sample of Adult Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]