Creating informed consent processes that honor patient autonomy without overburdening patients or physicians is a perennial challenge. Nowhere are these stressors and competing interests more visible than in intensive care units (ICUs). Some advocate bundled consent for common interventions to decrease time pressures and increase focus on goals of care.[1] Others express concern that the temporal delay between bundled consent and interventions may decrease comprehension and compromise informed consent.[2] To address these issues, we sought to describe consent practices within adult ICUs.

We included questions regarding consent in adult ICUs within a questionnaire administered to nurse managers of all ICUs in the state of Pennsylvania in the United States (US).[3] We asked whether their ICUs required separate consent, bundled consent, or no consent for 16 common interventions. We defined “bundled” as consent including at least one intervention with admission.

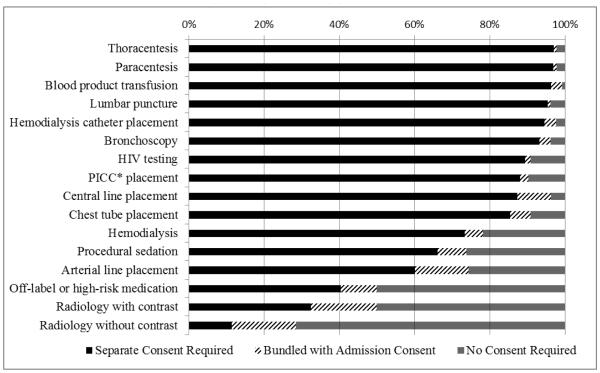

Among 223 eligible nurse managers, 136 (61%) completed the survey, representing 24 (18%) medical, 11 (8%) surgical, 77 (57%) combined medical/surgical, and 22 (16%) specialty ICUs (cardiac, burn, neurological, transplant, trauma) within 98 hospitals. Units had 3-42 beds (median 12) with 40-9000 (median 1050) annual admissions. Twenty-five percent (34/134) reported that patients or their surrogates were required to sign consent for ICU admission. Nineteen percent (25/134) reported utilizing a bundled consent. Figure 1 displays the proportions of ICUs that required separate consent, bundled consent, or no consent for 16 common interventions.

Figure. Consent Requirements for Sixteen Common ICU Interventions.

*PICC = peripherally inserted central catheter.

Respondents selecting “unsure” were excluded from analysis; this made up less than 4% of responses except for: off-label or high-risk medication (30%); hemodialysis (8%); and radiology with contrast (6%).

Informed consent practices vary across ICUs. For ten of the sixteen interventions queried, more than 85% of units required separate informed consent. Two previous US studies reported separate consents for the same procedures in 55-85% of ICUs. A prior European study found lower consent requirements perhaps reflecting cultural differences or changing practices. [4] Bundled consents for ICU admission and procedures are rarely utilized; usage by one-fifth of adult ICUs is slightly lower than previously reported.[5] Our findings may indicate a shift towards more stringent informed consent practices. Future research is needed to understand the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches to consent in the ICU.

A strength of our study is that it describes practices across a statewide census of adult ICUs, enhancing generalizability. Pennsylvania is a geographically and socioeconomically diverse state that includes local, regional, and national referral-level ICUs, with and without academic affiliations and across the urban-rural spectrum. Prior studies have had low response rates, have been limited to academic centers, or have been otherwise narrow in the hospital populations surveyed. Limitations of this study include inclusion of a single state in the US, inability to account for regional influences and local legislation, and the possibility of response error.

In summary, ICUs vary in their informed consent practices. Bundled consent for common procedures remains rare, despite conceivable advantages over just-in-time consent. These findings should prompt discussion regarding best practices for clinical informed consent within ICUs.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None to report

Conflict of Interest: None to report

Contributors’ Statement

Dr. Weiss conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the initial analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Drs. Halpern and Joffe conceptualized and designed the study, participated in interpretation of data, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Drs. Kohn and Kerlin, and Ms. Madden designed the survey, acquired the data, participated in interpretation of the data, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

References

- 1.Davis N, Pohlman A, Gehlbach B, Kress JP, McAtee J, Herlitz J, Hall J. Improving the process of informed consent in the critically ill. JAMA. 2003;289:1963–1968. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeGirolamo A, Mallareddy M, Veerabjadraiah D, Smina M, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. Informed consent for invasive procedures in a community hospital medical intensive care unit. Conn Med. 2004;68:223–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohn R, Madden V, Kahn JM, Asch DA, Barnato AE, Halpern SD, Kerlin MP. Variation in Intensive Care Unit Organizational Patterns: a State-Wide Analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A4698. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent JL. Information in the ICU: are we being honest with our patients? The results of a European questionnaire. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:1251–1256. doi: 10.1007/s001340050758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modra LJ, Hilton A, Hart GK. Informed consent for procedures in the intensive care unit: ethical and practical considerations. Crit Care Resusc. 2014;16:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]