Abstract

Objective

To compare efficacy and safety of retropubic Burch urethropexy and midurethral sling in women with SUI undergoing concomitant pelvic floor repair with sacrocolpopexy.

Methods

Women were randomly assigned to Burch retropubic urethropexy (n=56) or retropubic midurethral sling (n=57) through dynamic allocation balancing age, body mass index, history of prior incontinence surgery, intrinsic sphincter deficiency, preoperative incontinence diagnosis, and prolapse stage. Overall and stress-specific continence primary outcomes were ascertained with validated questionnaires and blinded cough stress test.

Results

Enrollment was June 1, 2009, through August 31, 2013. At 6 months, no difference was found in overall (29 midurethral sling [51%] vs 23 Burch [41%]; P=.30) (odds ratio [OR] [95% CI], 1.49 [0.71–3.13]) or stress-specific continence rates (42 midurethral sling [74%] vs 32 Burch [57%]; P=.06) (OR [95% CI], 2.10 [0.95–4.64]) between groups. However, the midurethral sling group reported greater satisfaction (78% vs 57%; P=.04) and were more likely to report successful surgery for SUI (71% vs 50%; P=.04), and to resolve preexisting urgency incontinence (72% vs 41%; P=.03). No difference was found in patient global impression of severity or symptom improvement, complication rates, or mesh exposures.

Conclusion

There was no difference in overall or stress-specific continence rates between midurethral sling and Burch urethropexy groups at 6 months. However, the midurethral sling group reported better patient-centered secondary outcomes.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse is a major health condition, affecting nearly one-half of women older than 50 years in Sweden (1) and approximately two-thirds of older women in Iowa (2). In the United States, an estimated 200,000 prolapse procedures are performed annually (3) at a societal cost exceeding $1 billion (4,5). It has been estimated that by 2050, the number of annual prolapse procedures will increase by 47.2% to 310,050 (6).

Pelvic organ prolapse is often associated with urinary incontinence; up to 91% of women who present for sacrocolpopexy require a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure (7,8). Sacrocolpopexy, an abdominal procedure in which the vagina is suspended to the sacrum with a nonabsorbable mesh, is the gold standard operation for pelvic organ prolapse (9). Historically, the Burch urethropexy, an abdominal procedure where the periurethral vaginal tissue is suspended to Cooper ligament (pectineal ligament) bilaterally, has been considered the benchmark operation because it has been highly effective at treating stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (overall cure rates, 68.9%–88.9%) (10–12). Following its introduction in 1996, the midurethral sling has become the new gold standard incontinence surgery, since it is a minimally invasive vaginal option with similar efficacy to the Burch (13).

It remains unclear which urinary incontinence procedure should be performed concomitantly with a sacrocolpopexy—a Burch conveniently through the same laparotomy incision or a vaginal midurethral sling on closure of the abdominal prolapse repair. To address this question, we conducted a multicenter randomized trial comparing these incontinence procedures in women undergoing concomitant sacrocolpopexy.

Materials and Methods

This superiority trial was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating sites, was registered in clinicaltrial.gov (NCT00934999), and was reported in accordance with the modified Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Statement (14). Women 21 years of age or older were recruited from the urogynecology clinics at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and University of Missouri, Kansas City, Missouri. Study-eligible women had symptomatic stage II or greater apical or anterior vaginal wall prolapse (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification point Aa, Ba, or C at ≥1 cm) (15) and opted for an abdominal prolapse repair. Women with a uterus were eligible to participate. Additional eligibility criteria included 1) symptomatic stress or stress predominant mixed urinary incontinence symptoms (see Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx, for definitions) (16) or occult SUI (ie, demonstrable urinary leakage on preoperative urodynamics with or without prolapse reduction in a patient without overt urinary incontinence symptoms); 2) cystometric capacity ≥200 cc; 3) a signed written consent; and 4) willingness to complete follow-up visits. Women with any of the following were excluded from the trial: known or suspected disease that affects bladder function (eg, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease); pregnancy; desired fertility; urethral diverticulum; history of radical pelvic surgery or pelvic radiation therapy; or current chemotherapy or radiation therapy for malignancy.

The anti-incontinence procedure was randomly selected through a dynamic allocation approach based on the Pocock-Simon method (17) to achieve balance between the intervention groups regarding age (<55 years vs ≥55 years), body mass index (<30 kg/m2 vs ≥30 kg/m2), history of prior incontinence surgery (none vs 1), preoperative incontinence diagnosis (overt vs occult), intrinsic sphincter deficiency (defined as an abdominal leak point pressure <60 cm H2O or a maximum urethral closure pressure <20 cm H2O), and prolapse stage (<IV vs IV) using a Web-based application. The assigned patient allocation was placed in a sealed opaque envelope by the study coordinator and given to the surgical team the morning of surgery. This randomization strategy was chosen since it has been shown to be superior to a permuted block (especially when the trial has >3 variables of interest) and because it is less likely to result in group imbalances due to chance when fewer than 400 patients are randomized (18).

Treatment allocation was masked to patients and the research nurses, who performed the standardized stress tests. Although patient masking could not be ensured (the midurethral sling group had 2 suprapubic stab incisions and the Burch procedure group had none), a bandage was placed in the lower abdomen by a nurse not involved in the cough stress test assessment.

Two primary outcomes were assessed at 6 months: overall continence and stress-specific continence. Patients were considered overall continent if they met each of 3 criteria at follow-up:

Negative standardized stress test. This test consisted of retrograde filling of the bladder to 300 cc or the maximum bladder capacity (whichever was less) and asking the patient to cough and bear down in supine and standing positions. Any transurethral urine loss was considered a positive test (10)

No interim re-treatment of SUI

No self-reported urinary incontinence (ie, a 0 score on the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire, Short Form (19)

Stress-specific continence was evaluated as another primary outcome. This continence required fulfilling criteria 1 and 2 and having no self-reported stress-related incontinence leakage of urine (a response of never or rarely to 6 questions from the stress incontinence subscale of the Medical, Epidemiological, and Social Aspects of Aging questionnaire) (20). Adverse events were classified on the basis of the Clavien-Dindo grading system of surgical complications (21). Complications of grade 3 or higher were considered serious.

All women underwent an abdominal sacrocolpopexy (Figure 1A) as described by Maher et al (22), with either a Burch modified Tanagho procedure (10) (Figure 1B) or a midurethral sling (Figure 1C) with a commercially available retropubic sling (Align urethral support system; C. R. Bard Inc) as described by Ulmsten et al (23). All surgeons were fellowship trained and had experience with both SUI surgical approaches, having performed greater than 20 of each procedure before enrolling. Concomitant posterior repairs were performed for the individual patient at the surgeon’s discretion.

Figure 1.

Schematic of sacrocolpopexy and urinary incontinence procedures. A. In abdominal sacrocolpopexy, the vaginal apex is supported to the anterior longitudinal ligament of the sacrum with a polypropylene mesh. B. Retropubic view of the Burch procedure, in which the periurethral vaginal tissue is suspended to the Cooper ligament bilaterally with use of a suture bridge. C. Sagittal view of the midurethral sling. In this procedure, a piece of polypropylene mesh is placed at the midurethra in a tension-free manner. © 2014 Mayo. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Participants completed validated questionnaires preoperatively and at each follow-up visit postoperatively. Patient satisfaction, voiding dysfunction, elevated postvoid residual, apical or anterior prolapse failure, de novo or resolution of urgency incontinence, and incontinence severity were assessed postoperatively as secondary outcomes (definitions are in Appendix 1, http://links.lww.com/xxx).

Assuming a 63% composite continence rate for the Burch procedure (24), the study had 80% power to detect a 25% difference in continence rates (eg, 63% vs 88%) with 46 women per group, based on a 2-sided χ2 test with a type I error level of .05. Assuming a 20% drop-out rate, the plan was to recruit 115 trial participants. Because the loss to follow-up was considerably less than expected, recruitment was stopped at 113 participants.

Analyses were performed using an intention-to-treat principle. Two additional analyses of the primary outcomes were conducted with only the patients who had complete follow-up (within protocol analysis) and with a last value carry-forward method. Baseline characteristics and outcomes were compared between the 2 groups through the 2-sample t test for continuous variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum test for ordinal measures, and the χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. P values were 2-sided and considered significant when P was less than .05. Statistical analyses were performed in a statistical software package (SAS version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Of the 1,392 women presenting for evaluation of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, or the University of Missouri, Kansas City, Missouri, between June 1, 2009, and August 31, 2013, approximately two-thirds were excluded because they opted for vaginal prolapse repair. The other screened participants either declined participation or did not fulfill urinary incontinence inclusion criteria (Figure 2). Of the 113 patients who opted to participate, 56 were randomly assigned to the Burch group and 57 were randomly assigned to the midurethral sling group. All women received the assigned intervention. Outcome assessments at 6-month follow-up were available for 51 (91%) of the women assigned to Burch and for 53 women (93%) of those assigned to midurethral sling. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Groups were similar in baseline demographic characteristics, including the dynamic allocation variables. Most participants were white, and the groups had similar preoperative urinary incontinence diagnosis (proportion with stress, mixed, or occult), incontinence and prolapse severity, history of prior incontinence surgery, and urodynamic findings.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of enrollment, randomization, and analysis of trial participants. MUS, midurethral sling; ITT, intention to treat; SUI, stress urinary incontinence; WPA, within protocol analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics, Clinical Characteristics, Urodynamic Findings, and Concomitant Procedures of the Trial Participants

| Characteristics* | Burch (n=56) | Midurethral Sling (n=57) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at operation, mean±SD, y | 56±10 | 56±11 | .91 |

| BMI, mean±SD, kg/m2 | 28.3±4.8 | 28.1±5.3 | .78 |

| White race† | 56 (100.0) | 55 (96.5) | .50 |

| Education level | .63 | ||

| ≤High school | 15 (26.8) | 17 (30.9) | |

| >High school | 41 (73.2) | 38 (69.1) | |

| Not documented | 0 | 2 | |

| Parity | .41 | ||

| 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| 1 | 4 (7.1) | 2 (3.5) | |

| 2 | 22 (39.3) | 17 (29.8) | |

| ≥3 | 30 (53.6) | 37 (64.9) | |

| Menopausal | 37 (66.1) | 34 (59.6) | .48 |

| Smoking history | 13 (23.2) | 11 (19.3) | .61 |

| Prior incontinence surgery | 4 (7.1) | 4 (7.0) | .99 |

| Preoperative diagnosis | .99 | ||

| Occult | 11 (19.6) | 11 (19.3) | |

| SUI | 13 (23.2) | 14 (24.6) | |

| Mixed | 32 (57.1) | 32 (56.1) | |

| OABq, symptom severity,‡ mean±SD | 38±23 | 41±24 | .51 |

| OABq, HRQL§ score, mean±SD | 67±24 | 67±21 | .92 |

| Prolapse stage | .99 | ||

| II | 26 (46.4) | 26 (45.6) | |

| III | 21 (37.5) | 22 (38.6) | |

| IV | 4 (7.1) | 5 (8.8) | |

| Unknown | 5 (8.9) | 4 (7.0) | |

| Type of urodynamics | .99 | ||

| Not done | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Simple | 10 (17.9) | 11 (19.3) | |

| Complex | 44 (78.6) | 45 (78.9) | |

| ISD|| | .45 | ||

| No | 31 (75.6) | 33 (82.5) | |

| Yes | 10 (24.4) | 7 (17.5) | |

| Unknown | 3 | 5 | |

| Detrusor contraction¶ | .11 | ||

| No | 36 (81.8) | 41 (93.2) | |

| Yes | 8 (18.2) | 3 (6.8) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 | |

| Additional procedure | .52 | ||

| None | 12 (21.4) | 17 (29.8) | |

| Posterior repair | 20 (35.7) | 19 (33.3) | |

| TAH or SCH | 11 (19.6) | 13 (22.8) | |

| Posterior repair and TAH or SCH | 13 (23.2) | 8 (14.0) | |

| Estimated blood loss, median (IQR), mL | 200 (150–300) | 200 (150–300) | .73 |

| Operative time, median (IQR), min | 253 (219–284) | 251 (218–281) | .70 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), d | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | .82 |

| Voiding dysfunction# | .33 | ||

| No | 19 (33.9) | 14 (25.5) | |

| Yes | 37 (66.1) | 41 (74.5) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; ISD, intrinsic sphincter deficiency; OABq, Overactive Bladder Questionnaire, Short Form; OABq, HRQL, health-related quality-of-life component of the bother component of the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire, Short Form; SCH, supracervical hysterectomy; TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy.

Values are presented as number and percentage of patients unless specified otherwise.

Race was based on patient self-report.

The OABq symptom severity, ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing greater symptom severity or bother.

The OABq, HRQL scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better health-related quality of life.

ISD was defined as an abdominal leak point pressure <60 cm H2O or a maximum urethral closure pressure <20 cm H2O.

Detrusor contracting during the cystometry phase of the urodynamics examination. Results are based on those patients with complex urodynamics only.

Please see Appendix 1 for definition.

Using the intention-to-treat principle, we found no difference in overall continence between the 2 groups at 6-month follow-up (29 [51%] for midurethral sling vs 23 [41%] for Burch; P=.30; odds ratio [OR] [95% CI], 1.49 [0.71–3.13]). A similar number of women met criteria for stress-specific continence in each group (42 midurethral sling [74%] vs 32 Burch [57%]; P=.06; OR [95% CI], 2.10 [0.95–4.64]). Similar findings were observed when only the patients who completed a 6-month follow-up were analyzed and when 6 weeks’ results were carried forward for those missing a 6-month assessment (Table 2). In addition, there was no difference in the proportion of patients with apical or anterior prolapse failure, patients who reported persistent voiding dysfunction symptoms, or patients who had increased postvoid residual volume between groups. Only 1 patient in the Burch group required urethrolysis, with no reported need for self-catheterization or indwelling catheter beyond 6 weeks in either group.

Table 2.

Primary Outcome Analysis at 6 Months Postoperatively

| Outcome* | Burch (n=56) | Midurethral Sling (n=57) | Absolute Risk Difference (95% CI) | NNT | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall continence† | |||||

| ITT‡ | 41.1 (23/56) | 50.9 (29/57) | 9.8 ( 8.5, 28.1) | 10.2 | .30 |

| WPA§ | 45.1 (23/51) | 54.7 (29/53) | 9.6 ( 9.5, 28.8) | 10.4 | .33 |

| Carry forward|| | 41.8 (23/55) | 54.5 (30/55) | 12.7 ( 5.8, 31.3) | 7.9 | .18 |

| Stress-specific continence¶ | |||||

| ITT‡ | 57.1 (32/56) | 73.7 (42/57) | 16.5 ( 0.7, 33.8) | 6.0 | .06 |

| WPA§ | 62.7 (32/51) | 79.2 (42/53) | 16.5 ( 0.7, 33.7) | 6.1 | .06 |

| Carry forward|| | 61.8 (34/55) | 78.2 (43/55) | 16.4 ( 0.5, 33.2) | 6.1 | .06 |

Abbreviations: ITT, intention-to-treat; NNT, number needed to treat; WPA, within protocol analysis.

Values are presented as number and percentage of patients.

Overall continence was defined as an International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire, Short Form, score of 0, a negative cough stress test, and no reoperation for stress urinary incontinence.

All randomly assigned patients were included in the analysis, with those who did not return for follow-up considered not to be continent.

For WPA, only patients with complete follow-up at 6 months.

For carry forward at 6 months, 6 of the 9 patients with incomplete follow-up had assessment at 6 weeks and were considered in the last value carry-forward approach.

Stress-specific continence was defined as a response of never or rarely to 6 questions from the stress-specific subdomain of the Medical, Epidemiological, and Social Aspects of Aging questionnaire, a negative cough stress test, and no reoperation for stress urinary incontinence.

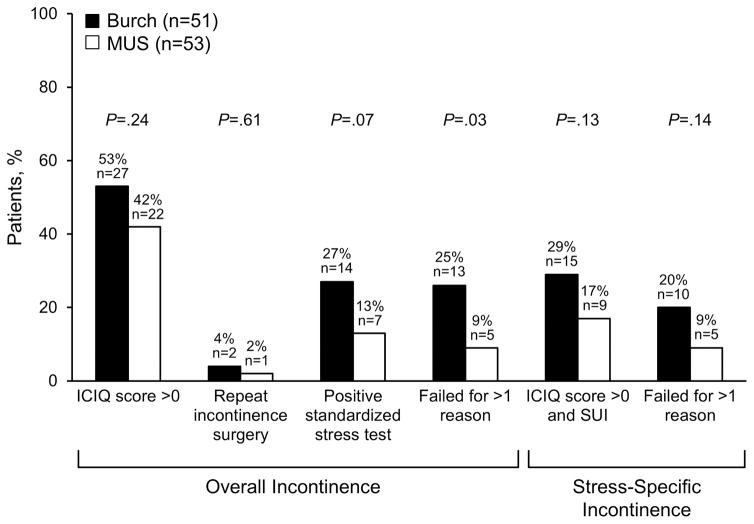

Most women were deemed incontinent because of a positive response to the International Consultation Incontinence Questionnaire question “Do you leak urine?” (Figure 3). There was no difference between the groups in the proportion of women who had an International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire score greater than 0, needed repeat operation for SUI, had positive stress test, or had an International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire score greater than zero and stress-specific symptoms. However, the direction of the association consistently favored the midurethral sling group, and fewer women in this group had failure for more than 1 reason (25% in Burch vs 9% in the sling; P=.03) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Specific factors leading to surgical failure. Stress-specific incontinence includes the results for repeat incontinence surgery and positive standardized stress test. ICIQ, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire, Short Form; MUS, midurethral sling; SUI, stress urinary incontinence.

No difference was found between the 2 groups in patient perception of symptom improvement or in incontinence severity (Table 3). However, at 6 months, women who had a midurethral sling were more likely to report a 10 for very successful (visual analog scale, 0–10) in response to the question, “In your opinion, how successful has your treatment for urinary leakage been?” than women who had a Burch (71% [34/48] vs 50% [23/46]; P=.04). In addition, patients who had a midurethral sling were more likely to report satisfaction than those who had a Burch (78% [38/49] vs 57% [27/47]; P=.04). Similar findings were observed when satisfaction was defined as a response of somewhat or completely (92% vs 72%; P=.01). No difference was found in the rate of de novo urge incontinence or rate of antimuscarinic medication use between the groups. However, women who had a midurethral sling were more likely to have resolution of preexisting urge incontinence at 6 months than women who had a Burch procedure (72% [18/25] vs 41% [9/22]; P=.03) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary Outcomes at 6 Months

| Characteristics* | Burch (n=51) | Midurethral Sling (n=53) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGIS | .09 | ||

| Normal/mild | 39 (79.6) | 44 (91.7) | |

| Moderate/severe | 10 (20.4) | 4 (8.3) | |

| Not reported | 2 | 5 | |

| Symptom improvement† | .15 | ||

| 0 | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) | |

| 2 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.0) | |

| 3 | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.0) | |

| 4 | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) | |

| 5 | 5 (10.9) | 2 (4.0) | |

| 6 | 0 (0) | 2 (4.0) | |

| 7 | 3 (6.5) | 2 (4.0) | |

| 8 | 3 (6.5) | 2 (4.0) | |

| 9 | 3 (6.5) | 3 (6.0) | |

| 10 | 26 (56.5) | 35 (70.0) | |

| Not reported | 5 | 3 | |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (7–10) | 10 (9–10) | .15 |

| Proportion reporting 10 | 26 (56.5) | 35 (70.0) | .17 |

| Not reported | 5 | 3 | |

| Treatment success‡ | .03 | ||

| 0 | 5 (10.9) | 2 (4.2) | |

| 1 | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.1) | |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 4 | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 5 | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.1) | |

| 6 | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.2) | |

| 7 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.1) | |

| 8 | 2 (4.3) | 2 (4.2) | |

| 9 | 7 (15.2) | 5 (10.4) | |

| 10 | 23 (50.0) | 34 (70.8) | |

| Not reported | 5 | 5 | |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (5–10) | 10 (9–10) | .03 |

| Proportion reporting 10 | 23 (50.0) | 34 (70.8) | .04 |

| Not reported | 5 | 5 | |

| ICIQ§ score | .13 | ||

| None (score, 0) | 24 (47.1) | 31 (58.5) | |

| Slight (score, 1–5) | 11 (21.6) | 13 (24.5) | |

| Moderate (score, 6–12) | 9 (17.6) | 6 (11.3) | |

| Severe (score, 13–18) | 5 (9.8) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Very severe (score, 19–21) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (3.8) | |

| Patient satisfaction|| | 27 (57.4) | 38 (77.6) | .04 |

| Not reported | 4 | 4 | |

| Prolapse recurrence | |||

| Anterior | 2/49 (4.1) | 3/50 (6.0) | .99 |

| Apical | 1/49 (2.0) | 0/50 (0) | .49 |

| Voiding dysfunction|| | 14/51 (27.5) | 9/49 (18.4) | .28 |

| Elevated postvoid residual|| | 1/47 (2.1) | 0/50 (0) | .48 |

| Urgency incontinence|| | |||

| De novo symptoms | 2/27 (7.4) | 3/28 (10.7) | .99 |

| Resolution of baseline symptoms | 9/22 (40.9) | 18/25 (72.0) | .03 |

| Antimuscarinic medication use | 11 (21.6) | 10 (18.9) | .73 |

Abbreviations: ICIQ, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire, Short Form; IQR, interquartile range; PGIS, Patient Global Impression of Severity.

Values are presented as number and percentage of patients unless specified otherwise.

Symptom improvement assessed with the question “Compared to how you were before your recent surgery for urinary leakage, how are your urinary leakage symptoms now?” Responses ranged from 0 (much worse) to 10 (much better) in a visual analog scale.

Treatment success assessed using the question “In your opinion, how successful has your treatment for urinary leakage been?” Responses ranged from 0 (not at all successful) to 10 (very successful) in a visual analog scale.

ICIQ scores ranged from 0 to 21, with higher scores representing more severe urinary leakage.

See Appendix 1 (http://links.lww.com/xxx) for definition.

The proportion of patients with persistent voiding dysfunction symptoms was not significantly different between the groups at follow-up (27% [14/51] vs 18% [9/49]; P=.28). In addition, among those with voiding dysfunction symptoms at baseline, the proportion who were symptom free at follow-up was not significantly different between the groups (36% [12/33] vs 23% [8/35] for Burch vs midurethral sling; P=.22).

Serious adverse events were uncommon (Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx), and no difference was found in the rate of serious adverse events between groups (9% in Burch group vs 11% in midurethral sling group; P=.77). Most of these events were related to the laparotomy rather than the incontinence part of the procedure (Appendix 1, http://links.lww.com/xxx). The proportion of women who needed surgical removal of mesh exposure did not differ between the 2 procedures (1/56 for Burch and 2/57 for midurethral sling). All the complications were related to sacrocolpopexy. One patient in the Burch group needed reoperation for incomplete bladder emptying. No bladder perforations occurred during midurethral sling trocar passage. The 1 death was unrelated to participation in the trial (the patient died of complications from drug overdose). The most common minor adverse event was urinary tract infection, with 30% (17/56) and 32% (18/57) having this complication in the Burch and midurethral sling groups.

Discussion

Our trial found no difference in overall or stress-specific continence rates between the Burch and midurethral sling groups when these procedures were performed concomitantly with a sacrocolpopexy at 6-month follow-up However, women undergoing a midurethral sling had higher satisfaction (78% [38/49] vs 57% [27/47]; P=.04), were more likely to report “very successful” continence outcome (71% [34/48] vs 50% [23/46]; P=.04), and were more likely to have resolution of baseline urgency incontinence (72% [18/25] vs 41% [9/22]; P=.03). It is possible that the greater improvement in baseline urgency incontinence with the midurethral sling led to the observed group difference in secondary outcomes. Alternatively, our study was underpowered to detect a clinically relevant difference in stress-specific continence between the groups (79% [42/53] in midurethral sling vs 63% [32/51] in Burch; P=.06).

Both the current findings and those of a large multicenter trial comparing Burch with midurethral sling (13) found no statistically significant differences in continence rates between these procedures. Moreover, a randomized trial comparing Burch with autologous sling reported continence rates following a Burch (75%) (24), using comparable composite outcomes, that were similar to ours (63%). These results suggest that the Burch procedure continues to be a viable and effective SUI procedure for women undergoing laparotomy for other indications.

Comparing outcomes across trials is challenging because heterogeneous definitions of continence exist (13,24,25) and because of differences in the patient populations studied. The present study compared SUI procedures at the time of sacrocolpopexy in patients with both prolapse and urinary incontinence symptoms at baseline. However, previous robustly designed trials (13,24,25) included a mixed population of participants undergoing SUI procedure alone and combined with prolapse repairs (13,22,24–26). This distinction is particularly relevant because patients undergoing combined SUI and prolapse repairs achieve greater continence at follow-up than women who have isolated SUI surgery (25,27).

Although the rates of de novo urgency incontinence did not differ between the groups, a higher percentage of patients reported resolution of urgency incontinence following midurethral sling than Burch (72% vs 41%; P=.03). Other investigators have reported similar findings (28,29). Theoretically, reconstitution of the pubourethral ligament may lead to improved urethral coaptation (by stabilizing the posterior urethra) and more effective urge suppression. Alternatively, the opposing vaginal vectors of the Burch (eg, upward toward the anterior abdominal wall) and the sacrocolpopexy (eg, posteriorly toward the levators) may directly affect coaptation or may alter detrusor function, thereby limiting the improvement in urge incontinence. Future studies using magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasonography may prove helpful in differentiating between these hypotheses.

Of note, our population consisted of primarily white women from the US Midwest region who underwent abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Hence, our findings may not apply to more racially diverse populations, to patients undergoing robotic or laparoscopic prolapse repairs, or to women undergoing laparoscopic Burch. In addition, all participating surgeons received their fellowship training at the same institution. This characteristic allowed for standardization of surgical approaches and postoperative care not typical in multicenter randomized trials. Even though it likely enhanced the internal validity of the trial, it limits the generalizability of our findings. Of note, primary outcome assessment is limited to 6 months and the result may differ with a longer follow-up. Finally, we did not use sham operations to ensure that the Burch procedure was masked to patients. Despite this limitation, 73% of the participants continued to have this detail blinded until their primary outcome assessment (data not shown).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded by Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Presented at the annual scientific meeting of the American Urogynecologic Society/International Urogynecological Association, Washington, District of Columbia, July 22–26, 2014, and at the 44th Annual Meeting of the International Continence Society, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, October 20–24, 2014.

References

- 1.Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svardsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Feb;180(2 Pt 1):299–305. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nygaard I, Bradley C, Brandt D Women’s Health Initiative. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: prevalence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Sep;104(3):489–97. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000136100.10818.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States, 1979–1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Jan;188(1):108–15. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helstrom L, Nilsson B. Impact of vaginal surgery on sexuality and quality of life in women with urinary incontinence or genital descensus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005 Jan;84(1):79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subak LL, Waetjen LE, van den Eeden S, Thom DH, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS. Cost of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Oct;98(4):646–51. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu JM, Kawasaki A, Hundley AF, Dieter AA, Myers ER, Sung VW. Predicting the number of women who will undergo incontinence and prolapse surgery, 2010 to 2050. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Sep;205(3):230, e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.046. Epub 2011 Apr 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culligan PJ, Blackwell L, Goldsmith LJ, Graham CA, Rogers A, Heit MH. A randomized controlled trial comparing fascia lata and synthetic mesh for sacral colpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jul;106(1):29–37. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000165824.62167.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefranc JP, Atallah D, Camatte S, Blondon J. Longterm followup of posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse abdominal repair: a report of 85 cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2002 Sep;195(3):352–8. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski HM, Cundiff G, Richter H, Gantz M, et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA. 2013 May 15;309(19):2016–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4919. Erratum in: JAMA. 2013 Sep 11;310(10):1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, Nygaard I, Richter HE, Visco AG, et al. Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006 Apr 13;354(15):1557–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bezerra CA, Bruschini H, Cody DJ. Traditional suburethral sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jul 20;(3):CD001754. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001754.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alcalay M, Monga A, Stanton SL. Burch colposuspension: a 10–20 year follow up. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995 Sep;102(9):740–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb11434.x. Erratum in: Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996, Mar; 103(3): 290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward K, Hilton P United Kingdom and Ireland Tension-free Vaginal Tape Trial Group. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002 Jul 13;325(7355):67. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7355.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Jun 1;152(11):726–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232. Epub 2010 Mar 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Jul;175(1):10–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blaivas JG, Panagopoulos G, Weiss JP, Somaroo C. Validation of the overactive bladder symptom score. J Urol. 2007 Aug;178(2):543–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.133. Epub 2007 Jun 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975 Mar;31(1):103–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott NW, McPherson GC, Ramsay CR, Campbell MK. The method of minimization for allocation to clinical trials: a review. Control Clin Trials. 2002 Dec;23(6):662–74. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandvik H, Espuna M, Hunskaar S. Validity of the incontinence severity index: comparison with pad-weighing tests. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006 Sep;17(5):520–4. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-0060-z. Epub 2006 Mar 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diokno AC, Brock BM, Brown MB, Herzog AR. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and other urological symptoms in the noninstitutionalized elderly. J Urol. 1986 Nov;136(5):1022–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004 Aug;240(2):205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maher CF, Qatawneh AM, Dwyer PL, Carey MP, Cornish A, Schluter PJ. Abdominal sacral colpopexy or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jan;190(1):20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulmsten U, Henriksson L, Johnson P, Varhos G. An ambulatory surgical procedure under local anesthesia for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1996;7(2):81–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01902378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albo ME, Richter HE, Brubaker L, Norton P, Kraus SR, Zimmern PE, et al. Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Burch colposuspension versus fascial sling to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2007 May 24;356(21):2143–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070416. Epub 2007 May 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, Kenton K, Norton PA, Sirls LT, et al. Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 3;362(22):2066–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912658. Epub 2010 May 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cosson M, Boukerrou M, Narducci F, Occelli B, Querleu D, Crepin G. Long-term results of the Burch procedure combined with abdominal sacrocolpopexy for treatment of vault prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003 Jun;14(2):104–7. doi: 10.1007/s00192-002-1028-x. Epub 2003 Mar 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trabuco EC, Carranza DA, El-Nashar SA, Klingele CJ, Gebhart JB. Midurethral slings for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 May;123(Suppl 1):197S–8S. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Athanasiou S, Grigoriadis T, Giannoulis G, Protopapas A, Antsaklis A. Midurethral slings for women with urodynamic mixed incontinence: what to expect? Int Urogynecol J. 2013 Mar;24(3):393–9. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1859-z. Epub 2012 Jul 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Habibi JR, Petrossian A, Rapp DE. Effect of transobturator midurethral sling placement on urgency and urge incontinence: 1-year outcomes. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015 Sep-Oct;21(5):283–6. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.