Abstract

The IL28B gene is associated with spontaneous or treatment-induced HCV viral clearance. However, the mechanism by which the IL28B single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) affects the extra-hepatic HCV immune responses and its relationship to HCV pathogenesis have not been thoroughly investigated. To examine the mechanism by which IL28B affects HCV clearance. Forty Egyptian patients with chronic HCV infection receiving an Interferon/ribavirin treatment regimen were enrolled into this study. There were two groups: non-responders (NR; n = 20) and sustained virologic responders (SVR; n = 20). The initial plasma HCV viral loads prior to treatment and IL28B genotypes were determined by quantitative RT-PCR and sequencing, respectively. Liver biopsies were examined to determine the inflammatory score and the stage of fibrosis. Colonic regulatory T cell (Treg) frequency was estimated by immunohistochemistry. No significant association between IL28B genotypes and response to therapy was identified, despite an odds ratio of 3.4 to have the TT genotype in NR compared to SVR (95 % confidence interval 0.3–35.3, p = 0.3). Patients with the TT-IL28Brs12979860 genotype (unfavorable genotype) have significantly higher frequencies of colonic Treg compared to the CT (p = 0.04) and CC (p = 0.03) genotypes. The frequency of colonic Treg cells in HCV-infected patients had a strong association with the IL-28B genotype and may have a significant impact on HCV clearance.

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C infection (CHC) is a global worldwide health problem, causing an increasing burden year by year, particularly in areas with high endemicity, such as Egypt [1–3]. The ultimate outcome of HCV infection is determined by the complex interaction of the host immune response, genetic predisposition and extrinsic modulators of clearance and progression.

Independent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) consistently identify variants within the IL28B gene region that are strongly associated with spontaneous and treatment-induced HCV clearance [4–9]. Of these, the rs12979860 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is one of the strongest predictors [4]. However, the exact mechanism by which its protective effect are largely unknown.

The IL28B rs12979860 CC favorable genotype has a marked differential distribution between racial groups, being least frequent in African Americans, most frequent in Asians, and intermediately frequent in Hispanics and Caucasians [4, 9]. In HCV genotype-4-infected Egyptian patients, there appear to be conflicting reports on the association between IL28Brs12979860 polymorphism and responses to therapy or immune response. Some reports have supported the association with response to therapy [10–12]. Others have failed to identify an association with HCV-specific cell-mediated immune responses [13]. The reasons for these differences are not clear, but the number and the HLA types of the enrolled patients as well as the geographical site of the study with differences in genetic backgrounds may explain some of the controversy [14, 15].

The rs12979860 SNP is located in the promoter sequence, upstream of the IL-28B gene, which encodes a member of the IFN-λ family of cytokines [4], which includes IL-29 (IFN-λ 1), IL-28A (IFN-λ 2), and IL-28B (IFN-λ 3), all of which are encoded by a gene cluster on a chromosomal region mapped to 19q13 [16, 17]. More recently, a transiently induced gene near the IFN-λ3 gene has been described to contain a dinucleotide variant, ss469415590 (TT or ΔG), that is in high linkage disequilibrium with rs12979860. The ss469415590 [ΔG] allele is a frameshift variant that creates a novel gene, designated as IFN-λ4, which encodes the interferon-lambda 4 (IFN-λ4) protein [18, 19].

The ss469415590 [TT] allele, which abrogates the production of the IFN-λ4 protein, is considered a favorable haplotype for HCV clearance, while the ss469415590 [ΔG] allele is considered unfavorable [20].

Recent in vitro studies in mice [21] and humans [22], have suggested that IFN-λ promotes the generation of immature dendritic cells (DCs) with tolerogenic activity. IFN-λ-treated DCs specifically induced proliferation and expansion of regulatory T (Treg) cells which play, a fundamental role in maintaining immune homeostasis. It has been reported that one of the potential mechanisms that might modulate HCV-specific immune responses is Treg cells [23–25]. However, the relationship between the protective effect of IFN-λ during HCV infection and Treg cells has not been explored. Treg cells are characterized by the expression of a unique transcription factor called forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3), which is highly expressed in the nucleus of Treg cells and is generally accepted to be the single best marker for quantifying Treg cells [25–28]. In cases of chronic hepatitis C (CHC), there is evidence that the frequency of Treg cells is higher than in controls and is negatively correlated with the necro-inflammatory score [29–31]. The elevated frequency of Treg cells may explain the weak HCV-specific T-cell responses in CHC [32]. Moreover, there is some evidence that individuals with CHC may harbour more Treg cells in their peripheral circulation [33] and in the liver than those uninfected [34]. Recent data from our laboratory have suggested that colonic Treg cells are negatively correlated with liver inflammation and HCV viral load, which supports a strong linkage between gut-derived Treg and HCV infection [35, 36]. Treg cells appear to assist in the maintenance of chronicity by inhibition of anti-HCV immune responses and consequently attenuate the intrahepatic tissue-damaging response to infection [26, 32].

The immunologic link between the gut and the liver through recirculation of a population of shared lymphocytes that are capable of homing to both the liver and gut via portal circulation has been reported [37].

The aim of our work was to determine the protective mechanism of the rs12979860 SNP in patients infected with HCV genotype 4 and its relationship to colonic Treg cell frequency. In addition, the relationships between IL-28B polymorphism and viral persistence, degree of liver inflammation, and fibrosis were investigated.

Patients and methods

Patient recruitment

A cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the role of colonic Treg cells and the IL28B rs12979860 SNP in CHC patients. All participants were recruited between January 2012 and September 2013 from Assiut Liver Institute outpatient clinics, Assiut, Egypt. Consent was obtained from all participants according to an IRB protocol approved by the Assiut University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Forty patients with CHC who received interferon/ribavirin therapy were enrolled and divided into two groups according to the outcome of therapy. The first group included patients who were non-responders (NR group; n = 20), and the second group included patients with sustained virologic response (SVR group; n = 20) to the standard of care in Egypt during the time of enrollment. Inclusion criteria for the patients with CHC were positivity for HCV antibodies by ELISA and HCV RNA by real-time PCR. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, history of Schistosoma infection, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and autoimmune disease. There was no exclusion was due to race, age, or gender. Twenty milliliters (ml) of blood was drawn from each subject. Figure 1 shows a flow chart describing the study design.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for study of the role of IL28B and Treg in HCV infection. A schematic presentation of the study design and the number of subjects enrolled in each group are shown

Colonic tissue biopsies

After proper preparation, three random colonic biopsies (from the descending colon, 1–3 mm in size, using biopsy forceps) were obtained from each patient via flexible sigmoidoscopy. The colonic biopsies were taken within an average of 6 months after completion of the anti-HCV therapy.

Serological and liver function tests

Liver function tests were performed using a Hitachi 911 chemical analyzer (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). HBsAg, anti-HCV and anti-HIV were tested using commercially available microparticle enzyme immunoassay kits (AXSYM, Abbott Laboratories, Germany) as specified by the manufacturer.

Determination of HCV viral load by real-time PCR

The HCV viral load in patients’ plasma was determined using real-time PCR as described [38]. Quantitative measurement of HCV RNA by real-time PCR was performed using a PCR kit (Artus® HCV RG RT-PCR supplied by QIAGEN GmbH, Germany, Cat. No. 4518263) as specified by the manufacturer.

Assessment of liver inflammation and fibrosis

Liver biopsy specimens were obtained from all patients with CHC prior to treatment and used for assessment of liver inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatic histopathological findings were interpreted independently of clinical and biochemical data by a pathologist, according to the criteria described for the METAVIR scoring system [39].

Assessment of IL28B genotypes

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were used for DNA extraction and subsequent sequencing. A DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, GmbH, Germany) was used for DNA extraction from the PBMCs. A Taq PCR Master Mix Kit (QIAGEN) and IL28B forward and reverse primers were added to the extracted DNA to amplify the rs12979860 SNP, and the amplified DNA was then subjected to gel electrophoresis. The samples with visible bands were purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) and sent to the DNA Core Facility (Massachusetts General Hospital, Cambridge, MA) for rs12979860 SNP sequence analysis.

Examination of the frequency of Treg cells

The frequencies of Treg and CD3+ T cells in colonic biopsies were determined using fluorescent immunohistochemistry as described previously [35, 36]. The number of colonic Treg and CD3+ T cells was determined by using a Zeiss LASER scanning confocal microscope (LSM710) with high-power field (1HPF = 0.4 mm2). Ten HPFs were examined for each slide and averaged. Data were calculated as the percent frequency of Treg as follows:

Statistical analysis

Data for clinical and demographic characteristics are presented as range (minimum, maximum) or mean ± SD. Continuous variables (such as Treg frequencies, liver fibrosis and inflammation, ALT, AST, platelet counts and viral load) were compared among the enrolled patients using Student’s t-test, or the Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate, with significance set at p ≤ 0.05. The ANOVA test was used to examine differences between groups of enrolled subjects. Correction for multiple testing was done using the Tukey-Kramer method. Correlations between the parameters measured were calculated using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. All statistical analyses were done using Graph Pad Prism 6 Software (San Diego, California, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the study subjects

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the enrolled subjects are summarized in Table 1. Both the SVR and NR groups had a predominantly male patient population at 85 % each. There was no significant difference in platelet count (p = 0.4), ALT (p = 0.6), or AST (p = 0.4) levels between the two groups. Regarding the histopathologic grading, there was no significant difference in their METAVIR score prior to treatment.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data for the enrolled subjects

| Demographic characteristics | NR group (N = 20) |

SVR group (N = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male:female | 17:3 | 17:3 |

| Age | ||

| Range | 21–54 | 20–51 |

| Mean ± SD | 43.5 ± 8.6 | 40.3 ± 7.8 |

| HCV viral load [106 IU/ml, (Mean ± SD)] | 0.9 ± 0.8 | NA |

| Distribution of liver inflammatory grade | ||

| Grade 1–2 | 11 | 14 |

| Grade 3–4 | 9 | 6 |

| Distribution of liver fibrosis stage | ||

| Stage 1–2 | 13 | 18 |

| Stage 3–4 | 7 | 2 |

| ALT [IU/ml (Mean ± SD)] | 37 ± 22.5 | 32.5 ± 26.7 |

| AST [IU/ml (Mean ± SD)] | 32.2 ± 23 | 25.9 ± 18.9 |

| Platelet count [×103/µl (Mean ± SD)] | 202.1 ± 64 | 217.7 ± 47 |

Relationship between the IL28Brs12979860 genotype and response to therapy

All 40 samples examined were sequenced for IL28B. Overall, 67.5 % of the patients were genotype CT, 22.5 % were genotype CC, and 10 % were genotype TT. A previous study suggested that the frequencies of these IL28B genotypes in healthy controls in Egypt are CT (52.1 %), followed by CC (29.2 %) and TT (18.8 %), which are comparable to those observed in our study [40]. The NR genotyped group was distributed as 4 (20 %) CC, 13 (65 %) CT, and 3 (15 %) TT. Likewise, the SVR group included 5 (25 %) CC, 14 (70 %) CT, and 1 (5 %) TT. The T allele was less frequent (75 %) in the SVR group, while the favorable C allele was more frequent (95 %) in the same group when compared to the NR group. There was no significant association between the IL28B genotype and response to therapy, despite an odds ratio of 3.4 to have the TT genotype in NR compared to SVR (95 % confidence interval 0.3–35.3, p = 0.3) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between IL28B genotypes and clinical parameters of HCV4-infected patients

| Clinical parameter | IL28B genotype | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT | CT | CC | TT vs CT | TT vs CC | CT vs CC | |

| CD3+ T cells (Avg ± SD) | 14 ± 9.2 | 12.37 ± 6.58 | 13.11 ± 7.94 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.78 |

| Total Treg (Avg ± SD) | 4 ± 4.08 | 1.81 ± 2.29 | 1.33 ± 2.24 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.59 |

| Treg frequency (Avg ± SD) | 0.58 ± 0.11 | 0.15 ± 0.16 | 0.17 ± 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.76 |

| Viral load (Copies/ml) (Avg ± SD) |

958000 ± 1354816 |

687434 ± 984094 |

97350 ± 90110 |

0.72 | 0.80 | 0.26 |

| Biopsy-inflammation grade (Avg ± SD) | 2.0 ± 1.15 | 2.1 ± 0.83 | 1.9 ± 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.55 |

| Biopsy-fibrosis stage (Avg ± SD) |

2.0 ± 1.15 | 1.8 ± 0.79 | 1.6 ± 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.46 | 0.51 |

| ALT (SGPT) (Avg ± SD) | 36.8 ± 21.36 | 36.2 ± 25.97 | 29.4 ± 22.53 | 0.97 | 0.59 | 0.49 |

| AST (SGOT) (Avg ± SD) | 19.0 ± 11.34 | 30.5 ± 20.61 | 29.0 ± 25.74 | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.86 |

| Platelet count (Avg ± SD) |

219.3 ± 52.94 | 209.4 ± 61.58 | 207.4 ± 46.25 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.93 |

| No response to therapy (NR) |

31 | 13 | 4 | |||

| Response to therapy (SVR) | 1 | 14 | 5 | |||

Bold means significant values (P < 0.05)

Odds ratio = 3.4, p = 0.3, 95 % confidence interval 0.3–35.3

Correlation between the IL28B genotype and HCV pathogenesis

No significant differences between the CD3+ T cell count, METAVIR inflammation and fibrosis score, ALT, AST, and platelet counts were observed when comparing TT vs. CT, TT vs. CC, and CT vs. CC, as shown in Table 2.

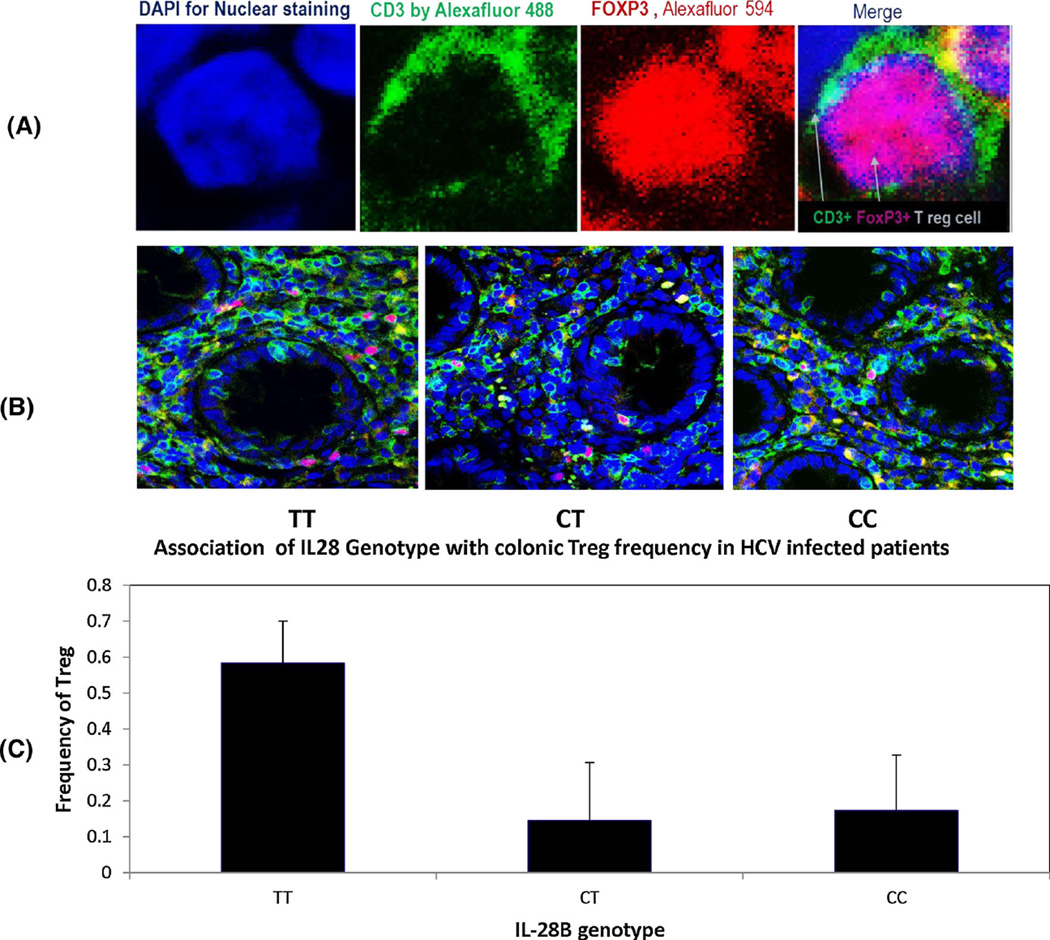

Correlation between the IL28B genotype and colonic Treg cell frequency

Forty patients were examined for colonic Treg cell frequency, 20 from the NR group and 20 from the SVR group. Colonic Treg cells were detected by indirect fluorescent immunohistochemical staining of CD3+ and FoxP3. Bivariate analysis showed significant differences in the frequency of colonic Treg in patients with TT vs. CT (p = 0.04) and TT vs. CC genotypes (p = 0.03). The average Treg cell frequency was almost threefold higher in the TT genotype group (mean ± SD = 0.58 ± 0.11 %) compared to the CT genotype (0.15 ± 0.16 %) and CC genotype groups (0.17 ± 0.15 %; Fig. 2C). From a univariate regression model, we confirmed a significant effect of IL28B genotype on the frequency of colonic Treg cells (Table 2). On the other hand, there was no significant difference in the number of CD3+ T cells or the total number of Treg cells (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of colonic Treg cells by double IF staining with anti-CD3 and anti-FoxP3 antibody. Colonic Treg cells were detected by indirect fluorescent immunohistochemical staining of CD3 and FoxP3 using mouse monoclonal anti-human CD3 antibody [PS1] and rabbit monoclonal anti-FoxP3 antibody [SP97]. A. Treg cells identified by green surface CD3 (by Alexa Fluor® 488-donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody) or red nuclear FoxP3 (by Alexa Fluor® 594 donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody). (B.). Examples of colonic Treg in TT, CT and CC genotype patients. C. The frequency of colonic Treg cells in the study groups in relationship to IL28B genotype

Discussion

In this study, we specifically examined the gut immune response and its relationship to HCV infection. The IL28B rs12979860 SNP is known to have a substantial effect on HCV pathogenesis. There is strong evidence from our laboratory that colonic Treg cells are negatively correlated with liver inflammation and HCV viral load, which suggests a strong linkage between gut-derived Treg cell populations and HCV infection [35, 36]. To investigate the mechanism by which the IL28B genotype affects the HCV gut immune response, we examined both the association between HCV clearance and IL28B rs12979860 genotype and the frequency of colonic Treg cells in treated HCV-4-infected patients.

The rs12979860 SNP has been identified as a significant predictor of SVR in chronic HCV patients that have undergone standard IFN-α therapy [4]. The rs12979860 SNP can also predict natural clearance of HCV [9]. Moreover, it has been shown that IL28B induction upon IFN stimulation is significantly lower in patients with IL28B-unfavorable genotypes (rs12979860 CT/TT) than those with an IL28B-favorable genotype (CC). IL28B induction was also lower in non-responders than in relapsers, and lower in non-sustained virologic responders to triple therapy including NS3 protease inhibitors [41]. This suggests that specific genetic differences in humans play a significant role in modulating the HCV-specific immune response. Our data showed a trend towards the TT genotype in NR subjects (OR = 3.3), but it was not statistically significant (Table 2), probably due to the small number of subjects examined. Prior research on the relationship of IL28B genotypes to treatment responses in HCV-4-infected patients has shown that patients with the TT genotype had a lower cure rate, similar to that observed in our study [42].

The exact mechanism by which IL28Brs12979860 SNP affects the immune system or facilitates specific HCV antiviral responses is unclear. To identify the potential role of IL28Brs12979860 and its relationship to colonic Treg cells in patients infected with HCV, we investigated the complex interplay between anti-HCV immune responses and genetic polymorphisms. We found a statistically significant association between colonic Treg frequencies and rs12979860 genotype TT compared with both CC and CT. The Treg cell frequencies are higher in TT compared to the CT and CC genotypes. This significant relationship was verified using a univariate regression model for IL28B genotypes on colonic Treg cells. A recent report suggested that the TT genotype is associated with an increase in IL28B induction upon IFN stimulation and lower levels of several mRNAs of genes [43]. Some of those genes, such as SOCS1, SOCS3, and IRF1, are associated with Treg induction and maintenance [44–46]. Therefore, suppression of those genes leads to an increase in Treg frequency, with subsequent suppression of the HCV-specific immune response and failure of anti-HCV therapy in patients with the IL28B TT genotype.

Additionally, the mechanism responsible for elevated colonic Treg in patients with the TT genotype may be related to the precise location of rs12979860 in the promoter region of the IL28B gene. The TT genotype might favor increased IL28B gene expression and secretion of interferon λ, resulting in stimulation of immature DCs and a consequent increase in Treg frequencies. Mennechet and Uze reported that interferon λ specifically stimulates DCs differentiation and migration to lymphoid organs and induces the proliferation of IL-2-dependent Treg cells [21]. This relationship between IL28B polymorphisms and Treg cell frequency may provide insight into the immunologic differences engendered by the genetic makeup of each patient.

T-cells also play a pivotal role in hepatic necro-inflammation and subsequent fibrosis in an effort to limit viral replication [47–50] by suppressing HCV-specific immune responses [51]. Since IL-28B rs12979860 SNP interacts intimately with the immune system, we investigated the correlations between liver histopathology and IL28B genotypes. No statistically significant relationship between IL28B and liver inflammation could be identified. Prior reports examining IL28B rs12979860 SNP association with liver inflammation and fibrosis in HCV-4 patients are controversial. Some researchers have found no substantial correlation between the rs12979860 polymorphism and necroinflammatory scores [10, 11, 42, 52]. However, other researchers found that the T allele is associated with liver fibrosis [53]. In contrast, D’Ambrosio et al. found the CC genotype to be independently associated with more severe portal inflammation [52], albeit in HCV-1 patients. The reasons for those differences are not clear, but the genetic backgrounds of the studied patients as well as the genotype of the HCV may explain some of the controversy [14, 15]. Larger studies are needed to carefully dissect the relationship between liver inflammation and IL28B genotypes in HCV-4-infected patients.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to link IL28B genotypes with the adaptive arm of the gut immune response in HCV patients. The importance of this study lies within the discovery of complex interactions between the underlying human genomics, the inherent immune response, and its defense against viral pathogens. In this study, we establish a strong relationship between high colonic Treg cell frequencies and IL-28B rs12979860 TT.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and the cross-sectional nature of our study cohort. Our results may serve as a benchmark for future investigations that are longitudinal in nature and explore the natural history of HCV infection and clearance. Based upon our findings, we recommend a more in-depth exploration of the effect of IL28B genotypes on the liver-gut immune axis. In conclusion, the frequency of colonic Treg cells in HCV-4-infected patients had a strong association with the IL-28B genotype.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the participants in this study, particularly the patients.

Funding and financial support This investigation was supported by an Egyptian Government scholarship for Helal Hetta, the Grant office, Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University, Egypt., Merck Investigator Initiated Studies (IISP #: 40458 [Shata]); National Institute of Health Grant (K24DK070528 [Sherman]); and was partially supported by Public Health Service Grant (P30 DK078392 [The Gene Expression Microarray Core Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center]); National Institute of Health Grant (NIH P30 DK078392 [Core of the Digestive Disease Research Core Center in Cincinnati]).

Abbreviations

- GWAS

Genome-wide association studies

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

- PBMCs

perIpheral blood mononuclear cells

- Treg

Regulatory T cells

- CHC

Chronic hepatitis C

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HCV-4

Hepatitis C virus genotype 4

- SVR

Sustained virologic response

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- Treg

T regulatory

- FoxP3

Forkhead box protein P3

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel diseases

- NR

Non-responder

- Peg-IFN + Rib

Pegylated interferon-α and ribavirin

- HPF

High-power field, 1 HPF=0.4 mm2

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- IF

Immunofluorescence

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval Verbal and written consent was obtained from all participants according to an IRB protocol approved by the Assiut University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of interest All authors declare that no conflict of interest exists regarding the work reported in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gouda I, Nada O, Ezzat S, Eldaly M, Loffredo C, Taylor C, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of hepatitis C virus (genotype 4) in B-cell NHL in an Egyptian population: correlation with serum HCV-RNA. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2010;18:29–34. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181ae9e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, Lavanchy D, Arthur RR, Magder LS, et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet. 2000;355:887–891. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarthy JJ, Li JH, Thompson A, Suchindran S, Lao XQ, Patel K, et al. Replicated association between an IL28B gene variant and a sustained response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2307–2314. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rauch A, Kutalik Z, Descombes P, Cai T, Di Iulio J, Mueller T, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment failure: a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1338–1345. 1345 e1331–1345 e1337. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, O’Huigin C, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youssef SS, Abbas EA, Abd el Aal AM, el Zanaty T, Seif SM. Association of IL28B polymorphism with fibrosis, liver inflammation, gender respective natural history of hepatitis C virus in egyptian patients with genotype 4. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014;34:22–27. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youssef SS, Abbas EA, Abd El Aal AM, Omran MH, Barakat A, Seif SM. IL28B rs 12979860 Predicts response to treatment in Egyptian hepatitis C virus genotype 4 patients and alpha fetoprotein increases its predictive strength. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014 doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaker OG, Sadik NA. Polymorphisms in interleukin-10 and interleukin-28B genes in Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 and their effect on the response to pegylated interferon/ribavirin-therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1842–1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Kamary SS, Hashem M, Saleh DA, Abdelwahab SF, Sobhy M, Shebl FM, et al. Hepatitis C virus-specific cell-mediated immune responses in children born to mothers infected with hepatitis C virus. J Pediatr. 2013;162:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzmaurice K, Hurst J, Dring M, Rauch A, McLaren PJ, Gunthard HF, et al. Additive effects of HLA alleles and innate immune genes determine viral outcome in HCV infection. Gut. 2015;64:813–819. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umemura T, Ota M, Katsuyama Y, Wada S, Mori H, Maruyama A, et al. KIR3DL1-HLA-Bw4 combination and IL28B polymorphism predict response to Peg-IFN and ribavirin with and without telaprevir in chronic hepatitis C. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:822–826. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheppard P, Kindsvogel W, Xu W, Henderson K, Schlutsmeyer S, Whitmore TE, et al. IL-28, IL-29 and their class II cytokine receptor IL-28R. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:63–68. doi: 10.1038/ni873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotenko SV, Gallagher G, Baurin VV, Lewis-Antes A, Shen M, Shah NK, et al. IFN-lambdas mediate antiviral protection through a distinct class II cytokine receptor complex. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:69–77. doi: 10.1038/ni875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamming OJ, Terczynska-Dyla E, Vieyres G, Dijkman R, Jorgensen SE, Akhtar H, et al. Interferon lambda 4 signals via the IFNlambda receptor to regulate antiviral activity against HCV and coronaviruses. EMBO J. 2013;32:3055–3065. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prokunina-Olsson L, Muchmore B, Tang W, Pfeiffer RM, Park H, Dickensheets H, et al. A variant upstream of IFNL3 (IL28B) creating a new interferon gene IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nat Genet. 2013;45:164–171. doi: 10.1038/ng.2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien TR, Prokunina-Olsson L, Donnelly RP. IFN-lambda4: the paradoxical new member of the interferon lambda family. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014;34:829–838. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mennechet FJ, Uze G. Interferon-lambda-treated dendritic cells specifically induce proliferation of FOXP3-expressing suppressor T cells. Blood. 2006;107:4417–4423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolganiuc A, Kodys K, Marshall C, Saha B, Zhang S, Bala S, et al. Type III interferons, IL-28 and IL-29, are increased in chronic HCV infection and induce myeloid dendritic cell-mediated FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartling HJ, Gaardbo JC, Ronit A, Knudsen LS, Ullum H, Vainer B, et al. CD4(+) and CD8(+) regulatory T cells (Tregs) are elevated and display an active phenotype in patients with chronic HCV mono-infection and HIV/HCV co-infection. Scand J Immunol. 2012;76:294–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolacchi F, Sinistro A, Ciaprini C, Demin F, Capozzi M, Carducci FC, Drapeau CMJ, Rocchi G, Bergamini A. Increased hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes and reduced HCV-specific CD4+ T cell response in HCV-infected patients with normal versus abnormal alanine aminotransferase levels. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:88–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sturm N, Thelu MA, Camous X, Dimitrov G, Ramzan M, Dufeu-Duchesne T, et al. Characterization and role of intra-hepatic regulatory T cells in chronic hepatitis C pathogenesis. J Hepatol. 2010;53:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keynan Y, Card CM, McLaren PJ, Dawood MR, Kasper K, Fowke KR. The role of regulatory T cells in chronic and acute viral infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1046–1052. doi: 10.1086/529379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magg T, Mannert J, Ellwart JW, Schmid I, Albert MH. Subcellular localization of FOXP3 in human regulatory and nonregulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1627–1638. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rushbrook SM, Ward SM, Unitt E, Vowler SL, Lucas M, Klenerman P, et al. Regulatory T cells suppress in vitro proliferation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during persistent hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:7852–7859. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7852-7859.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boettler T, Spangenberg HC, Neumann-Haefelin C, Panther E, Urbani S, Ferrari C, et al. T cells with a CD4+ CD25+ regulatory phenotype suppress in vitro proliferation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:7860–7867. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7860-7867.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itose I, Kanto T, Kakita N, Takebe S, Inoue M, Higashitani K, et al. Enhanced ability of regulatory T cells in chronic hepatitis C patients with persistently normal alanine aminotransferase levels than those with active hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:844–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amoroso A, D’Amico F, Consolo M, Skarmoutsou E, Neri S, Dianzani U, et al. Evaluation of circulating CD4+ CD25+ and liver-infiltrating Foxp3+ cells in HCV-associated liver disease. Int J Mol Med. 2012;29:983–988. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugimoto K, Ikeda F, Stadanlick J, Nunes FA, Alter HJ, Chang KM. Suppression of HCV-specific T cells without differential hierarchy demonstrated ex vivo in persistent HCV infection. Hepatology. 2003;38:1437–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward SM, Fox BC, Brown PJ, Worthington J, Fox SB, Chapman RW, et al. Quantification and localisation of FOXP3+ T lymphocytes and relation to hepatic inflammation during chronic HCV infection. J Hepatol. 2007;47:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hetta HF, Mekky MA, Khalil NK, Mohamed WA, El-Feky MA, Ahmed SH, et al. Association of colonic regulatory T cells with hepatitis C virus pathogenesis and liver pathology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1543–1551. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hetta HF, Mekky MA, Khalil NK, Mohamed WA, El-Feky MA, Ahmed SH, et al. Extra-hepatic infection of HCV in the colon tissue and its relationship with HCV pathogenesis. J Med Microbiol. 2016 doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gualdi R, Bossard P, Zheng M, Hamada Y, Coleman JR, Zaret KS. Hepatic specification of the gut endoderm in vitro: cell signaling and transcriptional control. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1670–1682. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-sherif WTSS, Afifi NA, EL-Amin HA. Occult hepatitis B infection among Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patients and its relation with liver enzymes and hepatitis B markers. Life Sci. 2012;9:467–474. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. 1996;24:289–293. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zekri AR, Salama H, Medhat E, Bahnassy AA, Morsy HM, Lotfy MM, et al. IL28B rs12979860 gene polymorphism in Egyptian patients with chronic liver disease infected with HCV. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:7213–7218. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.17.7213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murakawa M, Asahina Y, Nakagawa M, Sakamoto N, Nitta S, Kusano-Kitazume A, et al. Impaired induction of interleukin 28B and expression of interferon lambda 4 associated with nonresponse to interferon-based therapy in chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1075–1084. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marabita F, Aghemo A, De Nicola S, Rumi MG, Cheroni C, Scavelli R, et al. Genetic variation in the interleukin-28B gene is not associated with fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C and known date of infection. Hepatology. 2011;54:1127–1134. doi: 10.1002/hep.24503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iijima S, Matsuura K, Watanabe T, Onomoto K, Fujita T, Ito K, et al. Influence of genes suppressing interferon effects in peripheral blood mononuclear cells during triple antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbi J, Pardoll D, Pan F. Treg functional stability and its responsiveness to the microenvironment. Immunol Rev. 2014;259:115–139. doi: 10.1111/imr.12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhan Y, Davey GM, Graham KL, Kiu H, Dudek NL, Kay T, et al. SOCS1 negatively regulates the production of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells in the thymus. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:473–480. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu LF, Boldin MP, Chaudhry A, Lin LL, Taganov KD, Hanada T, et al. Function of miR-146a in controlling Treg cell-mediated regulation of Th1 responses. Cell. 2010;142:914–929. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Napoli J, Bishop GA, McGuinness PH, Painter DM, McCaughan GW. Progressive liver injury in chronic hepatitis C infection correlates with increased intrahepatic expression of Th1-associated cytokines. Hepatology. 1996;24:759–765. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quiroga JA, Martin J, Navas S, Carreno V. Induction of interleukin-12 production in chronic hepatitis C virus infection correlates with the hepatocellular damage. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:247–251. doi: 10.1086/517446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abrignani S. Immune responses throughout hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection: HCV from the immune system point of view. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1997;19:47–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00945024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rehermann B. Interaction between the hepatitis C virus and the immune system. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:127–141. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cabrera R, Tu Z, Xu Y, Firpi RJ, Rosen HR, Liu C, et al. An immunomodulatory role for CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T lymphocytes in hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2004;40:1062–1071. doi: 10.1002/hep.20454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D’Ambrosio R, Aghemo A, De Francesco R, Rumi MG, Galmozzi E, De Nicola S, et al. The association of IL28B genotype with the histological features of chronic hepatitis C is HCV genotype dependent. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:7213–7224. doi: 10.3390/ijms15057213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Falleti E, Bitetto D, Fabris C, Cussigh A, Fornasiere E, Cmet S, et al. Role of interleukin 28B rs12979860 C/T polymorphism on the histological outcome of chronic hepatitis C: relationship with gender and viral genotype. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:891–899. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]