Abstract

Understanding the genetic variation in germplasm is of utmost importance for crop improvement. Therefore, efforts were made to analyse the molecular marker based genetic diversity of 20 Annona genotypes from five different species of family Annonaceae. During analysis, a set of 11 RAPD primers yielded a total of 152 bands with 80.01 % polymorphism and PIC for RAPD ranged from 0.86 to 0.92 with a mean of 0.89. With 93.05 % polymorphism, 12 SSR primers produced 39 amplicons. The PIC for SSRs ranged from 0.169 to 0.694 with of average of 0.339. The dendrogram produced from pooled molecular data of 11 RAPD and 12 SSR primers showed seven clusters at a cutoff value of 0.78. The dendrogram discriminated all the Annona genotypes suggesting that significant genetic diversity was present among the genotypes. Proximate fruit composition study of nine fruiting genotypes of Annona revealed that A. squamosa possessed significantly higher amount of most of studies biochemical which gives an opportunity to fruit breeders to improve the other Annona species. Likewise, A. muricata being rich in seed oil content can be exploited in oil industries.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13205-016-0520-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Annona, Fruit proximate composition, Genetic diversity, RAPD, SSR

Introduction

Annona, a member of family Annonaceae, is one of the largest tropical and subtropical families of trees, shrubs, and lianas with circa 135 genera and 2500 species distributed worldwide (Escribano et al. 2007). In genus Annona, merely six species, i.e. A. squamosa (widely cultivated), A. reticulata, A. cherimola, A. muricata, A. atemoya (a natural hybrid A. squamosa × A. cherimola) and A. diversifolia produce edible fruits. The origin of most of Annona species is South America and the Antilles, however, wild soursop (A. muricata) is thought to have originated in Africa (Pinto et al. 2005). The current distribution of important species covers almost all continents, with soursop and sugar apple showing the widest distribution, mainly in tropical regions. India is considered as secondary centre of origin for A. squamosa. Chromosome numbers of Annona are 2n = 2x = 14 and 16, except for A. glabra, which is a tetraploid species (2n = 4x = 28).

The pulp of Annonas is rich in minerals and vitamins (Gyamfi et al. 2011) and also a potential source of dietary fibre (up to 50 % w/w dry basis). High nutritive value of A. cherimola is due to fatty acids, edible fibres, carbohydrates, and minerals such as calcium, phosphorous and potassium (Lopez and Reginato 1990). Annona seeds, especially A. squamosa contain good amount of oil (Mariod et al. 2010) which can be exploited for industrial purpose. In addition, leaves, roots, barks, fruits and seeds of genus Annona have been considered as potential source of medicinally important compounds (Pinto et al. 2005). Hence, Annonas, a versatile plant with multiple use, are hardy and deciduous in nature, very easy to cultivate with minimum inputs, require comparatively little care and do not suffer from serious pests and diseases.

Fruits of A. squamosa and A. muricata occupy a promising position in today’s fruit market due to high demand by the processing industries (Santos et al. 2011). Though, their cultivation is still in incipient stages of domestication (Zonneveld et al. 2012). The genetic resources and plant diversity of outcrossing tropical tree species including Annonas are being eroded due to modernization of agriculture and land use changes. Hence, genetic resources of edible Annonas are exclusively present in situ, i.e. on farm, in home gardens/orchards and/or in natural populations.

Measuring genetic diversity is a mean for ranking the accessions for their use in breeding program. However, very few efforts have been carried out to identify diverse germplasm of Annonas. High variability among Annona population exists due to protogynous basis cross-pollination. In the past, morphological traits have been used as tools to characterize unexplored potential of germplasm for developing high yielding genotypes with better fruit quality (Folorunso and Modupe 2007). But traditional morphological markers are known to be significantly affected by edaphic and climatic conditions, hence, are not trustworthy due to high environmental influence (Kumar et al. 2014). Therefore, it is better to analyse diversity using molecular markers.

There are limited reports on exploitation of molecular markers for diversity analysis in Annonas. Few of these markers are random amplified polymorphic marker (RAPD) marker (Bharad et al. 2009; Ronning et al. 1995), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers (Rahman et al. 1998; Zhichang et al. 2011) and simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers (Escribano et al. 2004; Kwapata et al. 2007). On the other hand, information regarding nutritional value is of utmost important to select desired genotype for domestication in area of adaptation. Very little information is available on proximate analysis of Annona fruits (Onimawo 2002; Kulkarni et al. 2013; Boake et al. 2014). Keeping in view about scanty information of Annonas, efforts have been made to study the genetic diversity using RAPD and SSR molecular markers and proximate analysis of fruits of selected accessions.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and DNA isolation

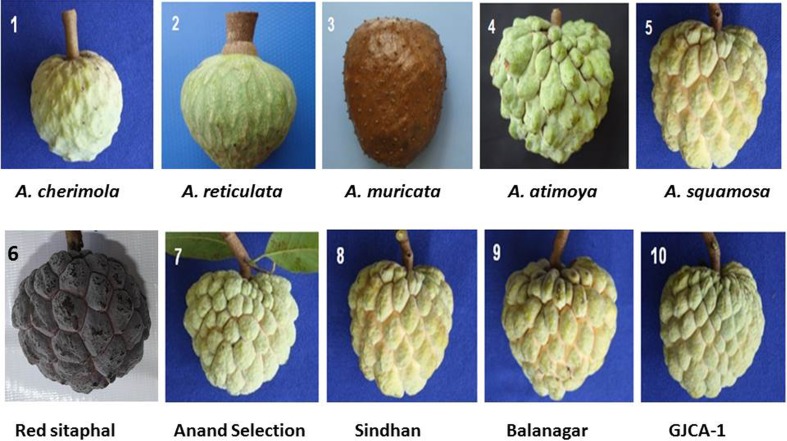

For molecular diversity analysis, a total of 20 Annona genotypes belonging to five different species were collected from various locations (Table 1; Fig. 1). DNA was extracted from young and tender leaves using CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle 1990). Extracted DNA was quantified using Nanodrop (Thermo scientific, USA) and further diluted to 20 ng/μl with TE buffer and stored at 4 °C for analysis.

Table 1.

List of Annona accessions used in present study

| Species | Accession | Collection area | Proximate analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. cherimola | – | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | ✓ |

| A. reticulata | – | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | ✓ |

| A. muricata | – | Gir Forest, Gujarat | ✓ |

| A. atemoya | – | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | ✓ |

| A. squamosa | Red Sitaphal | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | ✓ |

| A. squamosa | Anand Selection | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | ✓ |

| A. squamosa | Sindhan | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | ✓ |

| A. squamosa | Balanagar | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | ✓ |

| A. squamosa | GJCA-1 | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | ✓ |

| A. squamosa | Vidyanagar local | Anand, Gujarat | × |

| A. squamosa | ACC-1 | Mumbai, Maharashtra | × |

| A. squamosa | ACC-2 | Mumbai, Maharashtra | × |

| A. squamosa | ACC-3 | Mumbai, Maharashtra | × |

| A. squamosa | ACC-4 | Hyderabad, Telangana | × |

| A. squamosa | ACC-5 | Hyderabad, Telangana | × |

| A. squamosa | ACC-6 | Mumbai, Maharashtra | × |

| A. squamosa | Sindhan × Anand Selection | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | × |

| A. squamosa | Sindhan × Balanagar | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | × |

| A. squamosa | Anand Selection × Balanagar | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | × |

| A. squamosa | Balanagar × Red Sitaphal | Horticulture farm, AAU, Anand | × |

Fig. 1.

Fruit of different Annona species 1 A. cherimola; 2 A. reticulata; 3 A. muricata; 4 A. atemoya; 5 A. squamosa 6 Red Sitaphal; 7 Anand Selection; 8 Sindhan; 9 Balanagar and 10 GJCA-1

RAPD and SSR analysis

RAPD amplifications were carried out in 15 µl reaction volume containing: 40–50 ng DNA, 2 µl PCR Dream Taq buffer (10×) with 20 mM MgCl2 (Thermo Scientific, USA), 0.4 µl of 10 mM dNTPs (Thermo scientific, USA), 0.2 µl Dream Taq polymerase (5 U/μl, Thermo scientific, USA) and 1 μl of 10 pmol of primer (Table 2). Amplification was then performed in a DNA thermocycler (Eppendorf, Germany) using steps: (1) initial denaturation at 94 °C for 7 min, (2) 45 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 50 s, (3) primer annealing at 38 °C for 50 s, (4) extension at 72 °C for 1.2 min and (5) final extension at 72 °C for 7 min.

Table 2.

Characterization of RAPD primers among different genotypes of Annona species

| Locus name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Fragment size (bp) | Number of loci | Number of polymorphic loci | Polymorphism (%) | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPB-6 | TGCTCTGCCC | 423–1406 | 13 | 12 | 92.30 | 0.89 |

| OPB-7 | GGTGACGCAG | 146–1322 | 19 | 18 | 94.73 | 0.92 |

| OPB-8 | GTCCACACGG | 209–1328 | 16 | 14 | 87.50 | 0.89 |

| OPB-10 | CTGCTGGGAC | 294–1166 | 15 | 10 | 66.67 | 0.92 |

| OPB-12 | CCTTGACGCA | 246–1391 | 16 | 15 | 93.75 | 0.89 |

| OPD-2 | GGACCCAACC | 311–1325 | 10 | 8 | 80.00 | 0.86 |

| OPD-16 | AGGGCGTAAG | 180–1305 | 14 | 5 | 35.71 | 0.92 |

| OPD-20 | ACCCGGTCAC | 302–1268 | 11 | 6 | 54.54 | 0.89 |

| OPF-4 | GGTGATCAGG | 395–1308 | 12 | 10 | 83.33 | 0.86 |

| OPF-5 | CCGAATTCCC | 404–1400 | 14 | 14 | 100.00 | 0.87 |

| OPF-10 | GGAAGCTTGG | 451–1362 | 12 | 11 | 91.66 | 0.87 |

| Total | 152 | 123 | – | 9.79 | ||

| Average | 13.81 | 11.18 | 80.01 | 0.89 |

SSR amplification was carried out using 12 pairs of primers (Table 3) reported by Escribano et al. (2008). PCRs were performed in a 10 μl reaction mixture containing: 15 ng template DNA, 1 µl of PCR Dream Taq buffer (10×) with 20 mM MgCl2 (Thermo scientific, USA), 0.3 μl of each primer (10 pmol; forward and reverse), 0.3 μl of dNTPs (10 mM) and 0.15 µl Dream Taq polymerase (5U/μl, Thermo scientific, USA). The PCR cycling conditions were: 94 °C for 7 min as an initial denaturation step, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 50 s, for 50 s at annealing temperature (48–57 °C depending upon the primer), 72 °C for 1 min (extension) and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min.

Table 3.

Characterization of SSR primers among different genotypes of Annona species

| Locus name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Fragment size (bp) | Number of alleles | Number of polymorphic alleles | Polymorphism (%) | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMCH-29 | F: GTACCATCTTTTAGGAAATC | 196–280 | 4 | 4 | 100 | 0.496 |

| R: TGCAATCTATGTTAGTCAC | ||||||

| LMCH-43 | F: CTAGTTCCAAGACGTGAGAGAT | 210–375 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0.177 |

| R: ATAGGAATAAGGGACTGTTGAG | ||||||

| LMCH-48 | F: TTAGAGTGAAAAGCGGCAAG | 157–192 | 2 | 1 | 50 | 0.227 |

| R: TCAAGCTACAGAAAGTCTACCG | ||||||

| LMCH-70 | F: GAAGTTTTAGAGGCGATTCC | 152–178 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0.254 |

| R: TTTTGCCACTTTACTGTCAC | ||||||

| LMCH-71 | F: AGATAACACCCGCCCACTAT | 282–497 | 3 | 2 | 66.67 | 0.169 |

| R: ACAACTTTTCTCCCAACCTATC | ||||||

| LMCH-78 | F: ATTTGATTGATTGATTTCCTA | 172–235 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0.265 |

| R: CTTTTGCTTTCTTTCACATC | ||||||

| LMCH-79 | F: GAAGCAAGTAGACACGTAGTA | 212–384 | 5 | 5 | 100 | 0.694 |

| R: AGGGTTGGTATTTCTTTATAGT | ||||||

| LMCH-112 | F: TAACCCAGGATCTACAATAAT | 194–278 | 4 | 4 | 100 | 0.525 |

| R: TTGCATACATTTTCCTATTT | ||||||

| LMCH-114 | F: AAAATGTAGTGTGAAAGATGAC | 202–246 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0.351 |

| R: GTCCATTCAGTTTTAAGTGC | ||||||

| LMCH-119 | F: CAGAAAATTAGCAGAGGACTCA | 191–287 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0.265 |

| R: GTGGGTTGGGTTTTTAGGTC | ||||||

| LMCH-122 | F: AGCAAAGATAAAGAGAAGATAA | 190–212 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0.310 |

| R: ATCCAAGCCTATTAACAACT | ||||||

| LMCH-128 | F: CTTGTTAAAATGGCTGTTACT | 252–288 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0.343 |

| R: GCATTGAGCTGACATAACTC | ||||||

| Total | 39 | 37 | – | 4.068 | ||

| Average | 3.25 | 3.08 | 93.05 | 0.339 |

Amplified products of RAPD and SSR were electrophoresed on 1.5 and 2.5 % agarose gel, respectively, using 1× TBE buffer. The gels were photographed by gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California). A 100-bp DNA ladder was used as a DNA size standard. Each experiment was repeated twice for each primer and only reproducible fingerprints (DNA bands) were considered for data analysis.

Biochemical analysis

Out of 20 Annona genotypes, only nine were matured enough to produce fruits, hence proximate fruit composition analysis was performed only for nine genotypes. To determine various biochemical in fruits, three fully ripened mature fruits of similar and comparative stage were collected. A total of ten parameters of fruit and one parameter of seed, i.e. seed oil content was studied. For biochemical analysis, the fruit pulp and seeds was separated, freeze-dried, homogenised and stored at −20 °C until analysis. The starting material for biochemical analysis was 5 g pulp for moisture content, 2 g pulp each for ash and fibre content while 1 g pulp each for total carbohydrate, total soluble sugars (TSS), reducing sugars, protein, phenol, titratable acidity and ascorbic acid content. Similarly, 1 g seed powder (from homogenised composite seed sample) was used for oil content analysis. For proximate analysis, samples were prepared as per Onimawo (2002). Moisture content was obtained by heating the samples to a constant weight in a thermostatically controlled oven at 105 °C (Onimawo 2002). Total soluble sugar was estimated by the Anthrone method as suggested by Dubois et al. (1956). The ash, protein content, fibre content and total carbohydrates were obtained using the methods described by Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC 1980). Reducing sugars were estimated by method of Nelson (1944) while phenol content was calculated by the method described by Bray and Thorpe (1954). Titratable acidity, ascorbic acid content and seed oil content were estimated as per Mehta et al. (1993).

Data analysis

For each RAPD and SSR primer, the presence (1) or absence (0) of bands in each accession was scored to generate rectangular data matrix. The pairwise genetic similarity coefficient was calculated using Jaccard’ coefficient by NTSYS-pc v2.02 (Rohlf 1998). The matrices derived from RAPD and SSR data were correlated using MXCOMP module of NTSYS-pc. Polymorphism information content (PIC) was calculated according to Anderson et al. (1993). In case of biochemical parameters, data were subjected to evaluate arithmetic mean, standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV) using the standard formula specified in Chandel (1997).

Results and discussion

Molecular diversity and cluster analysis

RAPD analysis

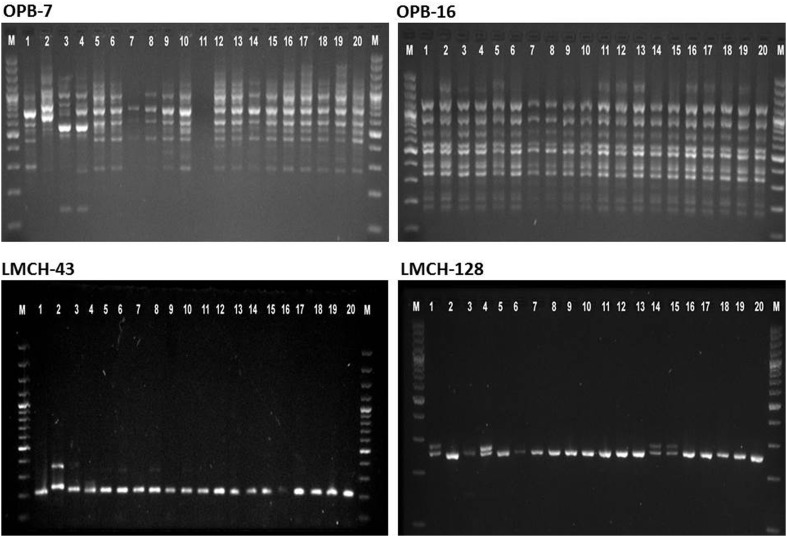

Eleven arbitrary decamer primers with clear and reproducible bands used for RAPD analysis could produce 152 fragments from the 20 genotypes of Annonas. The number of detected bands per primer varied from 10 to 19 with a mean of 13.81 bands per primer (Table 2; Fig. 2). Molecular size of the amplified PCR products ranged from 146 bp (OPB-7) to 1406 bp (OPB-6) which is comparable with results of Bharad et al. (2009) where fragment size ranged between 208 and 1354 bp. Out of total, 123 (80 %) loci were polymorphic. The number of polymorphic bands ranged from 5 to 18 with an average of 11.18. The highest polymorphism of 100 % was exhibited by primer OPF-5 while it was lowest (35.71 %) by OPD-16. The high polymorphism is an indication of prevalence of good diversity among accessions studied in present investigation. The polymorphism percentage, in this study, was much higher than the earlier reports in Annonas (73 %, Bharad et al. 2009; 29 %, Guimaraes et al. 2013). In contrast, Ronning et al. (1995) reported 93.5 % (86 out of 92 bands) polymorphism in A. cherimola, A. squamosa and their hybrids with 15 primers. Moreover, across the species polymorphism was 32 % higher than Elhawary et al. (2013) who showed merely 47.85 % polymorphism in four species (A. cherimola, A. squamosa, A. muricata and A. glabra) of the Annonaceae grown in Egypt.

Fig. 2.

DNA amplification profile of RAPD (OPB-7 and OPB-16) and SSR (LMCH-29 and LMCH-79) markers

The discrimination power of each RAPD primer was estimated by the PIC, which ranged from 0.86 (OPD-2 and OPF-4) to 0.92 (OPB-7, OPB-10 and OPD-16) with an average of 0.89 indicating the presence of high level of genetic diversity among different Annona genotypes. Genetic similarity matrix among cultivars showed an average distance ranging from 0.40 (A. muricata/ACC-4) to 0.93 (ACC-2/ACC-3) with a mean value of 0.70 (Table 2). The range of distance indicated moderate divergent in studied genotypes at the DNA level. This moderate diversity (7–60 %) range suggesting a good adaptability of Annonas in the region studied. The diversity recorded in present investigation was much higher than the earlier reported (19–57 % with AFLP) in China by Zhichang et al. (2011) in five Annona species.

SSR analysis

Microsatellites or SSRs, dispersed uniformly in genome, have become the markers of choice for fingerprinting purposes due to their high polymorphism, co-dominance nature, and reproducibility (Kumar et al. 2016). Development of SSRs is prohibitively expensive, but once the SSRs have been developed, they are cost- and time-effective in comparison to RAPD. Moreover, SSRs show cross genus- and species-amplification. Though, SSRs are potential marker to assess genetic diversity but have not been much exploited in Annonas especially A. squamosa (Gupta et al. 2015). Cross-species amplification of SSRs, developed in cherimoya, was successfully amplified in present study. This was is in congruence with Escribano et al. (2004) where SSRs markers of cherimoya were found highly transferable in different taxa of family Annonaceae. In this study, a total of 39 fragments were amplified from SSRs, of which 37 (93.05 %) were polymorphic (Table 3; Fig. 2). Lowest (50 %) polymorphism was produced by primer LMCH-48. The number of fragments per primer ranged from 2 to 5, with an average of 3.25 fragments per SSR; the number of polymorphic fragments ranged from 1 to 4, with an average of 3.08 fragments. The fragments per SSR was little lower than Escribano et al. (2007) where 4.9 bands/SSR were observed with 16 SSRs in A. cherimola. Though, it is higher than previous studies with isozymes (Perfectti and Pascual 1998). This indicates the effectiveness of SSRs to unravel diversity. In this study, amplicon size ranged from 152 bp (LMCH-70) to 497 bp (LMCH-71) which similar to results obtained previously in cherimoya with 15 SSRs (Escribano et al. 2004, 2008). PIC value ranged from 0.169 (LMCH-71) to 0.694 (LMCH-79) with an average of 0.339 indicating existence of sufficient genetic diversity among different Annona genotypes. With a mean of 0.67, similarity values among different Annona accessions ranged 0.12 (A. reticulata and A. muricata) to 1. A similar diversity level was observed in A. cherimola (Escribano et al. 2007) and in A. senegalensis (Kwapata et al. 2007).

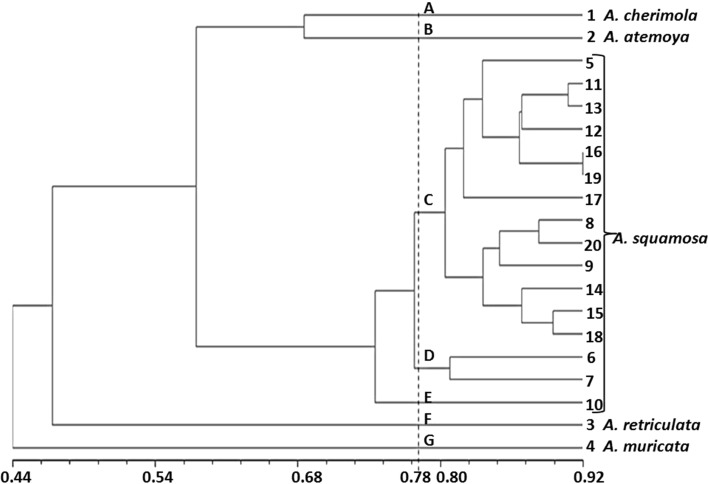

Combined RAPD and SSR based cluster analysis

Matrices calculated for RAPD and SSR markers were compared via Mantel tests. Mantel test based correlation of similarity matrices was 0.86. Moreover, with the fact that RAPD and SSR target different portions of the genome, an UPGMA analysis was performed by combining both marker systems. This allowed a better coverage of genome. The dendrogram produced from pooled molecular data of 11 RAPD and 12 SSR primers showed seven clusters viz., cluster ‘A’ (A. cherimola), cluster ‘B’ (A. atemoya), cluster ‘C’ (Red Sitaphal, Balanagar, GJCA-1, ACC-1, ACC-2, ACC-3, ACC-4, ACC-5, ACC-6, Anand Selection × Balanagar, Sindhan × Anand Selection, Sindhan × Balanagar and Balanagar × Red Sitaphal), cluster ‘D’ (Anand Selection and Sindhan), cluster ‘E’ (Vidyanagar local), cluster ‘F’ (A. reticulata) and cluster ‘G’ (A. muricata) at cutoff value of 0.78 similarity coefficient (Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 2). Previously, Guimaraes et al. (2013) revealed five clusters with RAPD analysis of 64 A. squamosa accessions. In this study, atemoya was lying between its parental genome which is to be expected as atemoya, is the progeny of A. cherimola × A. squamosa hybridizations (Ronning et al. 1995). High level of genetic dissimilarity among Annona species as well as accessions of A. squamosa demonstrated that the level of genetic variation in the species is substantial and indicated that genetic base is quite broad. Hence, accessions can be exploited for Annona breeding for fruit yield and quality. The reason for high diversity can be attributed due to the collection of germplasm from various diverse locations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Dendrogram of 20 Annona genotypes based on combined RAPD and SSR data. (5. Red Sitaphal, 6. Anand Selection, 7. Sindhan, 8. Balanagar, 9. GJCA-1, 10. Vidyanagar Local, 11. ACC-1, 12. ACC-2, 13. ACC-3, 14. ACC-4, 15. ACC-5, 16. ACC-6, 17. Sindhan × Anand Selection, 18. Sindhan × Balanagar, 19. Anand Selection × Balanagar and 20. Balanagar × Red Sitaphal)

Fruit proximate composition

The nutrient composition of the fruits of different genotypes is presented in Table 4. Annona genotypes were found to be statistically different (P < 0.05) in the context of all studied fruit quality parameters. The minimum (72.55 %) and maximum (81.23 %) moisture content was observed from GJCA-1 and A. muricata, respectively. Fruits from all Annona species showed high moisture contents which is a typical characteristic of fleshy fruits. Low dry matter also indicated that the Annonas are more prone to spoilage and have low storability (Onyechi et al. 2012). The range of moisture content in this study is in accordance with previous reports where it ranged between 73.2 and 79.65 % in A. squamosa (Orsi et al. 2012; Othman et al. 2014) and 75–85.3 % in A. muricata (Orsi et al. 2012; Sawant and Dongre 2014).

Table 4.

Statistics of fruit (pulp) quality parameters (fresh weight basis) and seed oil content (OC) of nine Annona genotypes [repetitions (n) = 2]

| Genotypes | MC (%) | AC (%) | TC (%) | TSS (%) | RS (%) | FC (%) | PC (%) | PhC (%) | TA (%) | Asc (mg/100 g) | OC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. cherimola | 79.26 | 1.56 | 17.54 | 14.41 | 4.33 | 2.22 | 1.69 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 19.60 | 29.33 |

| A. reticulata | 73.00 | 1.48 | 22.71 | 14.89 | 4.80 | 2.18 | 1.85 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 23.36 | 29.05 |

| A. muricata | 81.23 | 1.69 | 16.48 | 8.92 | 3.27 | 2.34 | 1.15 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 39.24 | 32.50 |

| A. atemoya | 76.63 | 1.62 | 20.71 | 14.62 | 6.67 | 3.82 | 1.84 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 32.74 | 28.41 |

| A. squamosa (mean) | 73.99 | 1.36 | 23.24 | 16.62 | 7.81 | 3.28 | 1.97 | 0.3 | 0.22 | 31.53 | 25.39 |

| - Red Sitaphal | 74.48 | 1.41 | 22.51 | 16.08 | 7.49 | 3.28 | 1.78 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 28.41 | 23.13 |

| - Anand Selection | 74.42 | 1.32 | 22.66 | 16.29 | 7.61 | 3.18 | 1.81 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 32.21 | 24.41 |

| - Sindhan | 73.65 | 1.43 | 23.04 | 16.69 | 7.81 | 3.38 | 2.13 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 32.06 | 26.56 |

| - Balanagar | 74.85 | 1.32 | 23.95 | 17.44 | 8.39 | 3.24 | 2.14 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 33.39 | 26.52 |

| - GJCA-1 | 72.55 | 1.32 | 24.05 | 16.63 | 7.75 | 3.32 | 1.98 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 31.57 | 26.35 |

| Minimum | 72.55 | 1.32 | 16.48 | 8.92 | 3.27 | 2.18 | 1.15 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 19.60 | 23.13 |

| Maximum | 81.23 | 1.69 | 24.05 | 17.44 | 8.39 | 3.82 | 2.14 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 39.24 | 32.50 |

| Mean | 75.56 | 1.46 | 21.52 | 15.11 | 6.46 | 3.00 | 1.82 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 30.29 | 27.36 |

| CD @ 5 % | 5.37 | 0.14 | 2.16 | 1.31 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 3.50 | 3.10 |

| SD | 2.94 | 0.14 | 2.74 | 2.54 | 1.84 | 0.59 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 5.81 | 2.81 |

| S.Em ± | 1.79 | 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.17 | 1.03 |

| CV (%) | 4.11 | 5.67 | 5.80 | 5.02 | 4.30 | 7.35 | 10.72 | 8.86 | 9.59 | 6.67 | 6.55 |

MC moisture content, AC ash content, TC total carbohydrates, TSS total soluble sugars, RS reducing sugars, FC fibre content, PC protein content, PhC phenol content, TA titratable acidity ASC ascorbic acid content, OC seed oil content

Ash contents, an index of total mineral content, ranged from 1.32 % (Anand Selection, Balanagar and GJCA-1) to 1.69 % (A. muricata). A study from Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India by Singh et al. (2014) on A. muricata fruits also concluded that soursop pulp contained appreciable amount of ash (3.05 %).

The fruit has calories equivalent to that of mangoes (SCUC 2006) as the amount of sugars in fruit pulp of A. squamosa was found to be quite high (21.42 % of fresh pulp) (Sravanthi et al. 2014). The proximate analysis revealed that the main constituent of the fruits was total carbohydrates which were ranged from 16.48 % (A. muricata) to 24.05 % (GJCA-1) with mean value of 21.52 % indicating Annonas are excellent source of energy. The carbohydrate content has been reported to be 14.63–15.1 % in A. muricata pulp (Benero et al. 1971) and 19–25 % in A. squamosa (Duke and DuCellier 1993). The highest value of TSS, an index of fruit sweetness, was obtained from Balanagar (17.44 %) followed by Sindhan (16.69 %), GJCA-1 (16.63 %) and Anand Selection (16.29 %) while the lowest value (8.92 %) obtained from A. muricata. Analyses carried out in the United States reported A. muricata and A. squamosa fruit contained 13.54 g and 19.24 g (per 100 g edible portion, exclude seeds and skin) total sugars (http://www.bda-ieo.it/test/ComponentiAlimento.aspx?Lan=Eng&foodid=8634_2). Though, fruit with high TSS are very prone to splitting.

Reducing sugars are important for resistance mechanism against stresses and had the highest value of 8.39 % in Balanagar, while the lowest value of 3.27 % was obtained from A. muricata. Dietary fibre was recorded maximum for A. atemoya (3.82 %) and minimum for A. reticulata (2.18 %). Higher dietary fibre decreases the risk of many disorders, such as constipation, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and obesity (Onimawo 2002).

Proteins are the building block of the body and are important components of various enzymes. Pinto et al. (2005) reported that pulp of Annonas have low protein but an appreciable vitamin C composition. In this study, protein content was found in the range of 1.15 (A. muricata) to 2.14 % (Balanagar). Previous reports on protein content in A. squamosa (1.2–2.4 %) by Pinto et al. (2005) and in A. muricata (1.21 %) by Amusa et al. (2003) are at par with present investigation.

Phenolic compounds are one of the most widely spread groups of phytochemicals. Plants need phenolic compounds for pigmentation, growth, reproduction, resistance to diseases and many other functions like antifeedants and attractants for pollinators, and functioning as sunscreen against UV light. In this study, it was found in the range of 0.26–0.50 % with maximum content for A. muricata and minimum for Sindhan. In addition to the antioxidant capacity, phenolics can influence the flavour determining fruit astringency and bitterness (Silva et al. 2013).

A variation between genotypes mean in connection to pulp titratable acidity which contributes to the acidity and aroma was highly significant. In current investigation, it ranged from 0.17 % in Balanagar to 0.65 % in A. muricata. The similar trend of titratable acidity was reported by Onimawo (2002) and Abbo et al. (2006) in A. muricata. Ascorbic acid, a potent antioxidant, was the range of 19.60 (A. cherimola) to 39.24 mg/100 g (A. muricata).

Very little attention has been paid to exploit the seeds for industrial purposes as little attempts have been made to extract oil from the seeds. Annona seeds were found rich enough in crude oil content, placing the seeds in the group of oil seeds, ranged from 23.13 % (Red Sitaphal) to 32.50 % (A. muricata). Findings with respect to oil studies are similar to the observations made by Djenontin et al. (2012). Though the seed oil content was lower than many oil seed crop like soybean, the result indicates that Annona oil can be new source of oil which can be exploited in industries instead of discarding as waste (Mariod et al. 2010).

Conclusion

The conventional phenotypic based diversity analysis has now swapped by DNA markers. This study with RAPD and SSR markers suggested that at DNA level there is considerable genetic diversity among Annona genotypes. Similarly, Annona genotypes were significantly diverse for investigated biochemical parameters. Interestingly, A. muricata, a rich source of seed oil, can be exploited in oil industries. The genotypes characterized based on molecular marker and biochemical gives an opportunity to fruit breeders to alter the fruit qualities of genus Annona.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge Department of Horticulture, AAU, Anand, for providing research material, Department of Agricultural Biotechnology and Department of Biochemistry, AAU, Anand, for providing all essential lab facilities to conduct the experiment.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Abbo ES, Olurin T, Odeyemi G. Studies on the storage stability of soursop (Annona muricata L.) juice. Afr J Biotechnol. 2006;5:108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Amusa N, Ashaye O, Oladapo M, Kafaru O. Pre-harvest deterioration of soursop (Annona muricata) at Ibadan Southwestern Nigeria and its effect on nutrient composition. Afr J Biotechnol. 2003;2:23–25. doi: 10.5897/AJB2003.000-1099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JA, Churchill GA, Autrique JE, Tanksley SD, Sorrells ME. Optimizing parental selection for genetic linkage maps. Genome. 1993;36:181–186. doi: 10.1139/g93-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official method of analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemist. Washington DC: AOAC; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Benero JR, Rodriguez AJ, de Sandoval AR. A soursop pulp extraction procedure. J Agr U Puerto Rico. 1971;55:518–519. [Google Scholar]

- Bharad SG, Kulwal PL, Bagal SA. Genetic diversity study in A. squamosa by morphological, biochemical and RAPD markers. Acta Hort. 2009;839:615–623. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2009.839.84. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boake AA, Faustina D, Jacob K, Ibok O. Dietary fibre, ascorbic acid and proximate composition of tropical underutilized fruits. Afr J Food Sci. 2014;8:305–310. doi: 10.5897/AJFS2014.1165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bray HG, Thorpe WV. Analysis of phenolic compounds of interest in metabolism. Method Biochem Anal. 1954;52:1–27. doi: 10.1002/9780470110171.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel SRS. A handbook of agricultural statistics. Kanpur: Achal Prakashan Mandir; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Djenontin TS, Wotto WD, Avlessi F, Lozano P, Sohounhloué DKC, Pioch D. Composition of Azadirachta indica and Carapa procera (Meliaceae) seed oils and cakes obtained after oil extraction. Ind Crop Prod. 2012;38:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus. 1990;12:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gills K, Hemilton J, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duke JA, DuCellier JL. CRC handbook of alternative cash crops. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Elhawary SS, Tantawy MEE, Rabeh MA, Fawaz NE. DNA fingerprinting, chemical composition, antitumor and antimicrobial activities of the essential oils and extractives of four Annona species from Egypt. J Nat Sci Res. 2013;3(13):59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Escribano P, Viruel MA, Hormaza JI. Characterization and cross species amplification of microsatellite (SSRs) markers in cherimoya (A. cherimola Mill. Annonaceae) Mol Ecol Notes. 2004;4:746–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00809.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Escribano P, Viruel MA, Hormaza JI. Molecular analysis of genetic diversity and geographic origin within an ex situ germplasm collection of cherimoya by using SSRs. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2007;132:357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Escribano P, Viruel MA, Hormaza JI. Development of 52 new polymorphic SSR markers from cherimoya (A. cherimola Mill.), transferability to related taxa and selection of a reduced set for DNA fingerprinting and diversity studies. Mol Ecol Notes. 2008;8:317–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folorunso AE, Modupe OV. Comparative study on the biochemical properties of the fruits of some Annona species and their leaf architectural study. Not Bot Horti Agrobot. 2007;35:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes RJF, Nietsche S, Rocha GB. Genetic diversity in sugar apple (A. squamosa L.) by using RAPD markers. Rev Ceres. 2013;60:428–431. doi: 10.1590/S0034-737X2013000300017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta Y, Pathak AK, Singh K, Mantri SS, Singh SP, Tuli R. De novo assembly and characterization of transcriptomes of early-stage fruit from two genotypes of Annona squamosa L. with contrast in seed number. BMC Genom. 2015;16:86–99. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1248-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyamfi K, Sarfo D, Nyarko B, Akaho E, Serfor-Armah Y, Ampomah-Amoako E. Assessment of elemental content in the fruit of graviola plant, Annona muricata, from some selected communities in Ghana by instrumental neutron activation analysis. Elixir J. 2011;41:5671–5675. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Joshi S, Kamthe P, Tekale P. Proximate analysis of peel and seed of Annona squamosa (Custard apple) fruit. Res J Chem Sci. 2013;3:92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Fougat RS, Sharma AK, Kulkarni K, Ramesh Mistry JG, Sakure AA, Kumar S. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of selected species of Plantago with emphasis on Plantago ovata. Aust J Crop Sci. 2014;8:1639–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Parekh Mithil J, Patel Chandni B, Zala Harshvardhan N, Sharma Ramavtar, Kulkarni Kalyani S, Fougat Ranbir S, Bhatt Ram K, Sakure Amar A. Development and validation of EST-derived SSR markers and diversity analysis in cluster bean. J Plant Biochem Biotech. 2016;25(3):263–269. doi: 10.1007/s13562-015-0337-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapata K, Mwase WF, Bokosi JM, Kwapata MB, Munyenyembe P. Genetic diversity of Annona senegalensis Pers. populations as revealed by simple sequence repeats (SSRs) Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6:1239–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez LA, Reginato G. Cherimoya. In: Nagy S, Shaw PE, Wardowski WF, editors. Fruits of tropical and subtropical origin, composition, properties and uses. Lake Alfred: Florida Science Source; 1990. pp. 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mariod AA, Elkheir S, Ahmed YM, Matthaus B. A. squamosa and C. nilotica seeds, the effect of the extraction method on the oil composition. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2010;87:763–769. doi: 10.1007/s11746-010-1548-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SL, Lodha ML, Sane PV. Recent advances in plant biochemistry. New Delhi: Publication and Information Division; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DH. A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi’s method for determination of the glucose. J Biol Chem. 1944;153:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Onimawo IA. Proximate composition and selected physicochemical properties of the seed, pulp and oil of soursop (A. muricata) Plant Food Hum Nutr. 2002;57:165–171. doi: 10.1023/A:1015228231512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyechi U, Ibeanu U, Nkiruka V, Eme EP, Madubike K. Nutrient phytochemical composition and sensory evaluation of soursop (Annona muricata) pulp and drink in South Eastern Nigeria. Int J Basic Appl Sci. 2012;12:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi DC, Carvalho VS, Nishi ACF, Damiani C, Asquieri ER. Use of sugar apple, atemoya and soursop for technological development of jams—chemical and sensorial composition. Ciênc Agrotec. 2012;36:560–566. doi: 10.1590/S1413-70542012000500009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Othman OC, Fabian C, Lugwisha E. Post harvest physicochemical properties of soursop (A. muricata L.) fruits of Coast region. Tanzan J Food Nutr Sci. 2014;2:220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Perfectti F, Pascual L. Characterization of cherimoya germplasm by isozyme markers. Fruit Var J. 1998;52:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto ACQ, Cordeiro MCR, de Andrade SRM, Ferreira FR, Filgueiras HAC, Alves RE, Kinpara DJ. Annona species. Southampton: International Centre for Underutilized Crops, University of Southampton; 2005. p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M, Shimada T, Yamamoto T, Yonemoto JY, Yoshida M. Genetical diversity of cherimoya cultivars revealed by amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis. Breed Sci. 1998;48:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf FJ. NTSYSpc. Numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system. Version 2.0. New York: Exeter Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ronning CM, Schnell RJ, Gazit S. Using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers to identify Annona cultivars. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1995;120:726–729. [Google Scholar]

- Santos MQC, Lemos EEP, Salvador TL, Rezende LP, Salvador TL, Silva JW, Barros PG, Campos RS. Rooting cuttings of soft soursop (Annona muricata) ‘Giant of Alagoas’. Acta Hortic. 2011;923:241–245. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2011.923.36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawant TP, Dongre RS. Bio-chemical compositional analysis of Annona muricata: a miracle fruit’s review. Inter J Univers Pharm Biosci. 2014;3:82–104. [Google Scholar]

- SCUC . Annona: Annona cherimola, A. muricata, A. reticulata, A. senegalensis and A. squamosa, field manual for extension workers and farmers. Southampton: University of Southampton; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Silva PPM, Carmo LF, Silva GM, Silveira-Diniz MF, Casemiro RC, Spoto MHF. Physical, chemical, and lipid composition of juçara (Euterpe edulis MART.) pulp. Braz J Food Technol. 2013;24:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Singh DR, Singh S, Banu VS. Phytochemical composition, antioxidant activity and sensory evaluation of potential underutilized fruit soursop (Annona muricata L.) in Bay Islands. J Andaman Sci Assoc. 2014;19:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sravanthi T, Waghrey K, Daddam JR. Studies on preservation and processing of custard apple (Annona squamosa L.) pulp. Intern J of Plant, Anim Environ Sci. 2014;4(3):676–682. [Google Scholar]

- Zhichang Z, Guibing H, Ruo O, Yunchun L, Yeyuan C, Shirong L. Studies of the genetic diversity of seven sweetsop (Annona squamosa L.) cultivars by amplified fragment. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10(35):6711–6715. [Google Scholar]

- Zonneveld MV, Scheldeman X, Escribano P, Viruel MA, Damme PV, Garcia W, Tapia C, Romero J, Sigueñas M, Hormaza JI. Mapping genetic diversity of cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.): application of spatial analysis for conservation and use of plant genetic resources. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.