Abstract

Just-noticeable differences (JNDs) in interaural time delay (ITD), interaural level difference (ILD), and interaural cross-correlation (ICC) were measured with low- and high-frequency noise bands over multiple sessions for 10 normal-hearing (NH) and 11 hearing-impaired (HI) listeners. Individual subject thresholds tended to improve with training then stabilize. Measured JNDs varied over these experienced listeners, for both subject groups and all tasks. Group JNDs were seldom predictable from hearing level. Individual listeners' JNDs were highly correlated across frequency for each task and group, except for ICC in the HI listeners. Further, ITD JNDs almost always significantly correlated with ILD JNDs within a group. Finally, although the ICC JNDs always significantly correlated with the ITD or ILD JNDs for the NH listeners, they often did not for the HI listeners. These findings suggest that little information about binaural sensitivity is added for NH listeners with multiple ITD, ILD, and ICC measures. For HI listeners, however, while ITD and ILD measures are well correlated, information is added with ICC measures. In general, the results suggest that less information is added with JND measures for NH listeners (15 significant correlations) than for HI listeners (six significant correlations).

I. INTRODUCTION

Interaural difference sensitivity is important in tasks varying from sound localization to speech intelligibility, and in many different types of auditory environments. Interaural difference sensitivity measurements can be used to characterize the extent to which hearing-impaired (HI) listeners' binaural hearing abilities are degraded relative to normal-hearing (NH) listeners (reviewed for hearing-impaired listeners by Durlach et al., 1981). Useful information may be gathered through the measurements to help scientists and clinicians to learn to best tailor the signal processing schemes for various kinds of auditory aids and prostheses to meet the needs of individual listeners.

Narrow-band noises at various center-frequencies have been used in many attempts at measuring sensitivity to time-invariant differences in interaural time delay (ITD) and interaural level difference (ILD) (e.g., Hawkins and Wightman, 1980; Smoski and Trahiotis, 1986; Koehnke et al., 1986; Kinkel, 1990; Gabriel et al., 1992; Holube, 1993; Koehnke et al., 1995; Smith-Olinde et al., 1998; Hawley, 2000). Sensitivity to time-varying interaural differences (varying both in time and in level) is also measured in tasks such as NoSπ detection (e.g., Koehnke et al., 1986; Gabriel et al., 1992; Koehnke et al., 1995; Hawley, 2000; Strelcyk and Dau, 2009; Goupell and Litovsky, 2014) and interaural cross-correlation (ICC) discrimination (e.g., Gabriel and Colburn, 1981, Koehnke et al., 1986; Kinkel, 1990; Gabriel et al., 1992; Holube, 1993; Koehnke et al., 1995; Goupell and Hartmann, 2006; Goupell and Litovsky, 2014). A number of these studies found large inter-subject variability within the just-noticeable difference (JND) thresholds that were measured for a particular subject group. Another common finding among these studies was that JNDs measured for a subject group were unable to be predicted by the pure-tone audiogram measures for the listeners of the group.

Even though interaural difference JNDs have been measured in many previous studies, there are a number of unanswered questions on how to best measure binaural abilities for those within a particular subject sub-population. Included among the largely unanswered questions are those related to how performance thresholds might be affected by listener-effort, concentration and training. While questions related to how training might affect interaural difference sensitivity thresholds have been addressed in some studies (e.g., Wright and Fitzgerald, 2001; Zhang and Wright, 2007; Ortiz and Wright, 2009; Zhang and Wright, 2009; Ortiz and Wright, 2010; Goupell and Barrett, 2015), one norm in these studies was for interaural difference sensitivity performance thresholds to be measured for a small number of tasks, rather than for many tasks. Another was for the performance scores to be measured for NH listeners alone, so that less is known about training effects for impaired listeners.

The measurement process can be highly time-consuming when multiple measures are involved. Given how attrition rate might increase and subject attentiveness might decrease with time-of-testing, another relevant unanswered question is whether performance thresholds for those within a subject pool even need to be measured in all the different tasks in order for the binaural abilities of those within the group to be characterized for the tasks of interest. More specifically, if it were found that the performance thresholds across two tasks were to significantly correlate, it would suggest that redundant information is added when performances are measured in the second task after being measured in the first task. More redundancy found across tasks would imply that less information regarding listener binaural ability would be lost if one of the tasks were dropped from the testing regimen to reduce overall testing time.

A challenge in interpreting the binaural hearing literature is in determining whether an impaired listener's binaural hearing ability was degraded due to the hearing impairment, or due to non-impairment-related factors. Hearing impairments might result in degraded sensitivity to interaural differences through peripherally or centrally related mechanisms (e.g., Colburn and Trahiotis, 1991; Gabriel et al., 1992). At the same time, there are a number of obstacles in determining whether an impaired listener's sensitivity was actually degraded due to the hearing impairment, or degraded due to non-impairment-related factors. First, it is unclear how to define “normal” binaural hearing. For example, for the case of ITD sensitivity at 500 Hz, data from some studies (Koehnke et al., 1986; Bernstein et al., 1998) suggest that thresholds in normal-hearing (NH) listeners can differ among listeners, while other studies (e.g., Hawkins and Wightman, 1980; Gabriel et al., 1992; Smith-Olinde et al., 1998) report similar strong performances for all tested NH listeners. It is possible that some of the reported poor performance thresholds for NH listeners were the actual result of “hidden impairments” that are not reflected by abnormal pure-tone thresholds on the audiogram, such as related to temporary threshold-shift (TTS), as discussed by Kujawa and Liberman (2009), or to obscure auditory dysfunction (OAD; Saunders and Haggard, 1989). As for those reporting no poor performers, given the small number of NH listeners reported, one might question whether some poorly performing NH subjects might have been dismissed prior to study completion (perhaps thought of as not paying adequate attention or not understanding the task). Another difficulty involved in comparing normal-hearing and hearing-impaired performance thresholds is that stimulus level can affect subject performance. Hausler et al. (1983), for example, showed improved performance as the level was raised up to 30 dB above detection level in NH listeners. While most studied NH listeners meet this criterion easily, HI listeners often have a reduced range between detection and discomfort (or equipment limitations) so that experimenters are often prevented from presenting levels 30 dB above detection threshold.

To begin to address some of the issues, this study gathered cohorts of young NH and HI listeners and measured interaural difference sensitivity thresholds in ITD, ILD, and ICC with narrow-band noises centered at 500 Hz and at 4 kHz as the listeners gained experience. Comfortably loud presentation levels were used so that stable performances might be measured in the listeners: HI listeners in particular. A number of questions were addressed, including those related to how the performance thresholds might change with experience and those related to whether thresholds in a task would significantly correlate with other factors, including correlations with hearing level (at the test center-frequency or averaged across frequencies), with center frequency of stimulus bands, or with thresholds measured in other tasks at the same frequency.

II. METHODS

A. Participants

Ten normal-hearing and eleven hearing-impaired listeners completed data collection in the current study. All listeners had English as their primary language. Seven other subjects, four with normal hearing and three with hearing impairments, either voluntarily dropped out of the study or were unable to complete the study within their period of availability. This high drop-out rate may have been related to the fact that the set of measurements took a long time (a minimum of about twelve hours) for a subject to complete. All listeners were paid for their participation, except for subject HI10, who was one of the authors of this study.

1. Normal-hearing listeners

The normal-hearing (NH) listeners were screened prior to experiments to ensure that their pure-tone thresholds were in the normal range [less than or equal to 20 dB hearing level (HL)] for octave frequencies between 250 and 8000 Hz. Four male and six female NH listeners completed data collection. Their ages ranged from 19 to 29 years old at the time of testing (the mean was 23 years old). The only experience that any NH listener in our group had on psychophysical listening tasks, to our knowledge, came from one hour of speech intelligibility testing for a later study.

2. Hearing-impaired listeners

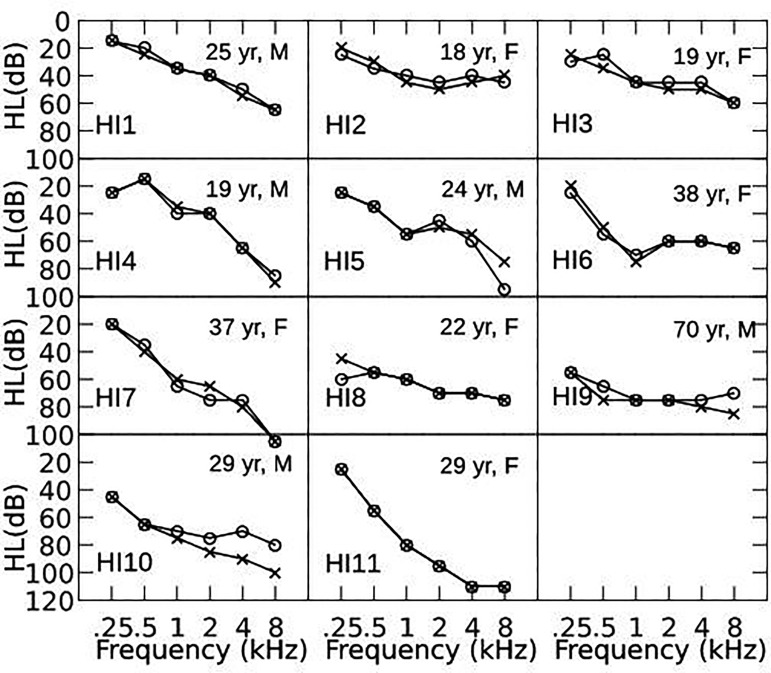

The hearing-impaired (HI) listeners were screened prior to the experiments to ensure the subjects had sensorineural hearing losses and that the losses were bilaterally symmetric. For all the subjects, sensorineural hearing loss was confirmed via the lack of an air-bone gap. All the subjects had audiograms that were left/right symmetric, defined as mean threshold difference of less than ten decibels (10 dB) for audiometric frequencies between 250 Hz and 4 kHz. The audiometric thresholds, ages, and genders of the eleven HI subjects (five male, six female) who completed data collection are given in Fig. 1. Hearing losses varied in severity. Subjects are ordered and labeled (HI1 to HI11) by increasing average hearing loss across frequencies and ears. Further details regarding subject etiology (if known), musical experience, and status with regards to hearing-aid use are reported in Table I. All HI listeners, except for HI9, were less than 40 years old at the time of the study. All the HI subjects had participated in psychophysical listening tasks in past studies and in our lab. Subject HI9 was the only one who had experience in tasks measuring interaural difference sensitivity thresholds. This subject was included to allow for cross-study comparisons to be made.

FIG. 1.

Audiograms of hearing-impaired subjects. Hearing level as a function of frequency is shown for right ear (○) and left ear (×) separately. Subject numbers are in lower left. Subject age and gender are in the upper right of each panel. Subjects are arranged (as named) in order of increasing average hearing loss.

TABLE I.

HI subject etiology, musical experience, and hearing-aid usage.

| Subject | Etiology | Musical experience | Hearing aids |

|---|---|---|---|

| HI1 | Unknown | Yes, but not musician | Owns but does not use |

| HI2 | Unknown, discovered at 6, stable | No | Owns but does not use |

| HI3 | Sensorineural, discovered at 8, stable | No | Bilateral |

| HI4 | Sticklers, birth, progressed to adolescence | Musician | Right hearing aid at time of study |

| HI5 | Unknown, birth, unsure of progressiveness | No | No |

| HI6 | Unknown, birth, stable since adolescence | Musician, but not currently | Bilateral |

| HI7 | Unknown, third grade, progressive early, stable since | Yes, but not musician | Bilateral |

| HI8 | Unknown, diagnosed at age 6, progressive | Yes, but not musician | Bilateral |

| HI9 | Alport, sensorineural | No | Bilateral |

| HI10 | Sensorineural | No | Bilateral |

| HI11 | Unknown | No | Bilateral |

B. Stimuli

Interaural difference JNDs in ITD, ILD, and ICC were measured with one-third octave Gaussian noises. There were two center frequencies for each subject: the classic low frequency of 500 Hz and a high frequency of 4 kHz when allowed given subject audiometric thresholds. When hearing loss at 4 kHz precluded measurement due to equipment-related or discomfort-threshold limitations, performance thresholds were measured at 2 kHz instead of at 4 kHz. There were also few occasions in which performance was not measurable at either 2 or 4 kHz. The choices of low and high frequencies were designed to be on either side of the transition for phase-locking to pure tones (cf. Brughera et al., 2013). Stimuli and stimulus frequencies were also chosen to allow for comparison with thresholds measured in other studies (e.g., Koehnke et al., 1986; Gabriel et al., 1992; Koehnke et al., 1995; Hawley, 2000).

The noises were 300-ms long, with 15-ms linear rise/fall times. The inter-stimulus intervals were 500 ms. The stimuli were created digitally using the matlab random number generator and then filtered to a particular narrow-band region in the frequency domain similar to Koehnke et al. (1986) by eliminating (setting to zero) frequency components outside of the one-third-octave range for each center frequency. The effects of ringing in the time-domain (due to the sharp edges in the frequency domain) were offset through imposed (after the frequency-domain filtering) 15-ms-duration, linear ramps at the beginnings and ends of all stimuli. The resulting 16-bit stimuli were digitally amplified and then converted to analog signals with a 50-kHz sampling rate for all the tasks except for the ITD threshold tasks, where the sampling rates were increased to 100 kHz or to 156.25 kHz using the System II (Tucker-Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL) PD1.1 The high sampling rates allowed small time delays to be imposed by shifting samples; for the ITD JNDs, note that the presented ITDs were spaced apart by either 10 or 6.4 μs. The stimuli were attenuated with analog attenuators through the System II PA4 and processed through the System II headphone buffer (HB6) before being presented over headphones (Sennheiser model HD265) to listeners within a double-walled sound booth. No subjects wore hearing aids or any other kinds of assistive devices during testing.

Reference stimulus levels of 65 dB sound pressure level were used for the NH listeners, following some pilot testing.2 The reference stimulus levels for the HI listeners were set to subjectively medium-high levels. As a starting objective standard, the initial stimulus levels for the HI listeners were set to be slightly higher than the equivalent of 65 dB for NH based on loudness-matching data by Moore et al. (1985). Specifically, these initial levels were: 75–80 dB when the audiometric thresholds in the stimulus frequency band were less than 30 dB, 80–85 dB when the audiometric thresholds were between 30 and 50 dB, and 85 dB or higher when the audiometric thresholds were 50 dB or higher. Feedback was immediately obtained from subjects to make sure that the chosen levels were perceived to be medium-high in loudness. The stimulus levels were adjusted from the initial values if it was found that the levels were lower or higher than medium-high as perceived by the subjects, or if there was substantially more variability than normal among the data points within an adaptive track or across the different adaptive tracks for the specific sub-task. The final stimulus level used for each subject is given in Table II. Stimulus level calibration and confirmation was performed with a Bruel & Kjaer (Naerem, Denmark) 4153 artificial ear sound level meter that had an IEC (Newark, New York) 60318-1 coupler. The maximum stimulus levels were kept below 110 dB according to IRB regulations.

TABLE II.

Final stimulus levels used for hearing-impaired (HI) listeners. For each HI listener and each test frequency, the left-ear (“L”) and right-ear (“R”) hearing losses and the stimulus level used for each test are provided in this table, along with the high frequency used for each listener. In the high-frequency ILD task, lower-than-initially planned levels were used for HI3, HI5, and HI6, to avoid exceeding the subjects' discomfort thresholds. The same was true for all high-frequency tasks for HI4. Lower than initially planned levels were used for HI9 and HI10 in ILD at 2 kHz, to avoid exceeding the equipment ceiling.

| 500-Hz HL | 500-Hz stimulus level | High-frequency HL | High-frequency stimulus level | High-freq. test freq. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | R | ITD | ILD | ICC | L | R | ITD | ILD | ICC | ||

| HI1 | 25 | 20 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 55 | 50 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 4 kHz |

| HI2 | 30 | 35 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 45 | 40 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 4 kHz |

| HI3 | 35 | 25 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 50 | 45 | 85 | 75 | 85 | 4 kHz |

| HI4 | 15 | 15 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 65 | 65 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 4 kHz |

| HI5 | 35 | 35 | 85 | 80 | 80 | 55 | 60 | 90 | 88 | 90 | 4 kHz |

| HI6 | 50 | 55 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 60 | 60 | 85 | 80 | 85 | 4 kHz |

| HI7 | 40 | 35 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 75 | DNM | DNM | DNM | 4 kHz |

| HI8 | 55 | 55 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 70 | 70 | 98 | DNM | 98 | 4 kHz |

| HI9 | 75 | 65 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 75 | 75 | 100 | 95 | 100 | 2 kHz |

| HI10 | 65 | 65 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 85 | 75 | 100 | 95 | 100 | 2 kHz |

| HI11 | 55 | 55 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 95 | 95 | DNM | DNM | DNM | 2 kHz |

C. Measurement procedures

The JNDs were measured using the four-interval, two-alternative-forced-choice paradigm, with feedback provided after each trial. The task of the subject was to determine which interval (either the second or the third) was the “target” interval containing the interaural differences amid diotic reference intervals. Performance thresholds were measured using 2-down, 1-up adaptive tracks (Levitt, 1971), so that two correct answers increased the difficulty of the task and any incorrect answer decreased the difficulty. The tracks converged to 70.7% correct. The difficulty level was controlled by the amount of change in the interaural parameter for the target interval. Strategies to determine the amount of change and the units used for the interaural difference parameter are explained below for each parameter.

1. ITD and ILD thresholds

Time-invariant interaural differences were generated for the entire waveforms for the test intervals in the ITD and ILD discrimination experiments. To minimize listener-confusion, interaural differences were generated with the intent to make the target stimulus leading or louder on the same side (moving the same direction relative to the diotic reference) consistently in all trials within a set of three sequential blocks (e.g., right ear amplitude increased and left ear amplitude decreased to move the image to the right for every target interval in an ILD set). Prior to the experiments, the subjects were verbally instructed that the task was an interaural time or level-difference discrimination task, and instructed to choose the interval in which the sound was different from the other intervals. Throughout these tasks the subjects were instructed (via a graphical user-interface) to identify the off-center interval. Because the step sizes changed by multiplicative units, adaptive track thresholds were calculated as the geometric mean of the last eight reversals (as measured in decibels or microseconds), following Koehnke et al. (1995). A track was marked as “invalid” and was discarded if the number of trials in the track reached the adaptive track threshold limit (60 trials in ITD, 65 trials in ILD) before the completion of the 12 reversals. After the data collection was complete, the last six valid tracks for each of the right- and left-leading cases were included in the computation of the subject's JND for the particular frequency. Error bars were generated from the geometric standard deviation of the twelve thresholds, following Koehnke et al. (1995).

To create interaural time delays in test intervals of Δτ, the waveform to one ear was shifted by +Δτ/2 and the other by −Δτ/2, relative to diotic. At the beginning of the experiments, the initial ITD values were 700 μs (500 Hz) and 1000 μs (high frequency). The interaural time delays in the adaptive tracks were changed by a factor of 2 (in μs) over the first four reversals and by a factor of over the last eight reversals. After the first set of three blocks, the adaptive track starting values were adjusted according to each individual performance. For the subjects with the higher thresholds measured at the beginning the starting values were increased to at most 1400 μs (500 Hz) and 4000 μs (4 kHz), while for those with the thresholds that were lower at the beginning, the starting values were decreased to as low as 175 μs (500 Hz) and 350 μs (4 kHz). The adjustments were made so that the subjects would not be exposed to too many successive trials with a minimal level of difficulty and so that the subjects' available time would therefore be used most efficiently. It was hoped that there would be about six to ten early trials per adaptive track where most to all responses would be correct before the more difficult trials. No ceiling was imposed on the ITD measurements in terms of ITD in μs. After the thresholds were computed those cases where the JNDs were higher than 1000 μs were denoted as unmeasurable. This follows previous work (e.g., Gabriel et al., 1992; Koehnke et al., 1995).

For the interaural level difference discrimination experiments ILDs were generated by amplifying the waveform at one ear and attenuating the waveform in the opposite ear with respect to a diotic reference, according to

| (1) |

where B and A are the waveform amplitudes in the two ears, giving rise to an ILD equal to Δα dB. For the ILD measurements, a random-number generator (uniform distribution) was used to impose a roving level on all intervals, over a range of ±5 dB, to prevent the use of monaural level cues of up to 10 dB (Gabriel et al., 1992). Initial test-interval ILD values were 8 dB. The ILD values (in dB) were adjusted by a factor of two during the first four reversals and by a factor of during the last eight reversals. The ILDs and the roving levels were created digitally. The tracks were discarded if they reached ceiling. The ceilings for the ILD measurements varied depending on the listener and on the center-frequency for the task. The ceilings were lower when the stimulus levels were closer to the discomfort or the equipment limit. The lowest ceiling was 22 dB, which is far above the rove limit.

2. ICC thresholds

As in the ITD and ILD measurements, the reference-interval stimuli in the ICC measurements were diotic. The test interval stimuli were generated according to the equation

| (2) |

where ni(t) and nj(t) represent independent Gaussian noise samples and XL(t) and XR(t) represent waveforms at the left and right ears. The targeted interaural correlation for a left/right waveform set is represented by ρ. Note that, for a given ρ, the actual interaural correlation values varied because of the statistical fluctuations in the levels of the noise samples. This variability was described for the technique employed in this study by Hartmann and Cho (2011) (see “Asymmetric two-generator method”). In reference to the Hartmann and Cho (2011) study, the “weak equal power” assumption applies to the current study in that the left and right ear noise powers were matched in expected value as opposed to the sample powers being scaled relative to the other so that the powers would be matched exactly. Also, note that decorrelated waveforms (found in our test intervals) contain time-varying interaural differences. Interaural difference fluctuations increase in size with decreasing ρ (relative to 1) (cf. Gabriel, 1983; Goupell and Hartmann, 2006). The subjects were verbally informed that there would be four intervals, and verbally asked to report whether interval two or three was the odd interval among the four. They were verbally informed that the test interval might sound the broadest among the intervals and were asked to report which interval was the broadest, via graphical user-interface.

For the ICC tests, the parameter ρ was converted to a decibel value according to the “equivalently de-correlated” signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) in a classical No-Sπ detection task, according to the equation

| (3) |

so that as ρ decreases from ρ = 1, S/N-equivalent becomes less negative (Durlach et al., 1986). This S/N measure was used to adjust the level of difficulty from trial to trial and to record the threshold value; note that these S/N units could be related to ρ units and that this choice does not affect the stimuli.

At the beginning of the experiments, the adaptive tracks started with the test interval ICC at ρ = 0.85 (corresponding to an equivalent S/N of −11 dB S/N) at 500 Hz and ρ = 0.6 (corresponding to −6 dB) at 2 or 4 kHz. Depending on how the subjects performed initially, the starting value was changed so that the initial trials would be easier or more difficult but never more difficult than ρ = 0.95 (−16 dB S/N) at 500 Hz or ρ = 0.7 (−8 dB) at 2 and 4 kHz. During each track, the value of ρ changed by 3 dB equivalent S/N units over the first four reversals of the tracks, and by 1.5 dB equivalent S/N units over the last eight reversals. A track was marked as “invalid” and discarded if it reached the adaptive track threshold limit of 60 trials prior to completion of the set of 12 reversals.

3. Training and data collection

Since a number of previous reports (e.g., Wright and Fitzgerald, 2001) have shown that measured thresholds in interaural difference discrimination tasks can change across multiple days as a result of learning, sensitivity thresholds were measured repeatedly for the different tasks, each over the course of multiple days. The subjects came for one session of measurements lasting one-to-three hours each week, at a minimum. There were three successive adaptive tracks for each sub-task (e.g., ICC at a center frequency, or ITD or ILD at a center frequency and favoring one side or the other). The subjects took about five minutes to complete each individual adaptive track. At the beginning of the study, the subjects were first tested on the ICC tasks, then the ITD tasks, and finally the ILD tasks. The low-frequency noise tasks preceded the high-frequency tasks. This general order of measurements was maintained as performance thresholds were measured across all the various tasks.

As noted above the adaptive tracks were marked as invalid and discarded if they reached the adaptive track threshold limit (specified above for each case) prior to the completion of the designated number of reversals. In addition, tracks were also marked as invalid and discarded if the inter-quartile range of the levels for all trials during the last eight reversals spanned more than three steps (following Koehnke et al., 1995). The thresholds for all the tasks were measured repeatedly until there were at least six adaptive track thresholds in a performance plateau region following an early learning and improvement period, with the plateau and learning regions determined by visual inspection

D. Data analysis

The thresholds and geometric standard deviations for the ITD JNDs were processed (and plotted) on a log-base-10 scale. This scale agrees with how larger step sizes for the higher values and smaller step sizes for the lower values were used in the current study ITD measurements. Log-base-10 scales have been used in a number of previous studies for plotting ITD thresholds, including Koehnke et al. (1986) and Koehnke et al. (1995).

The thresholds for the ILD JNDs were also processed (and plotted) on a log-base-10 scale. The use of this scale is agrees with how the step sizes varied with ILD both in previous studies (Koehnke et al., 1995; Smith-Olinde et al., 1998; Hawley, 2000) and in the current study. ILD JNDs have also been studied on logarithmic scales in previous studies, including those describing statistical correlations between ITD and ILD JNDs (Hawley, 2000). In support of the log-base-10 scale for ILD as well as ITD, note the similarity in the lateralization function performance shapes for ITD (in μs) and ILD (in dB) (Yost, 1981). This suggests that if ITD JNDs are plotted on a logarithmic scale, then ILD JNDs should be as well when considering that correlations are being computed across the tasks. Note also that the ITD and ILD thresholds from previous studies are relatively evenly distributed when plotted on a log scale (cf. Fig. 7 which is discussed later). Finally, considering the ICC thresholds, because linear step sizes (in decibels) were used in the ICC measurements, ICC JNDs are plotted on a linear scale, in equivalent S/N in dB [cf. Eq. (3)].

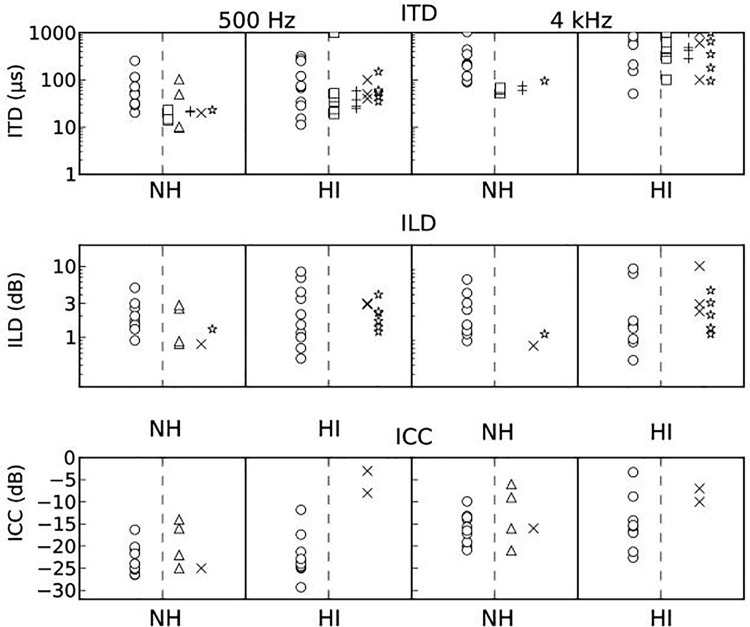

FIG. 7.

Comparison of current-study JNDs to JNDs from previous studies with highly trained subjects. Current-study thresholds (○) are compared to thresholds from Hawkins and Wightman (1980, ◻), Koehnke et al. (1986, △), Smoski and Trahiotis (1986, +), Gabriel et al. (1992, ×), Smith-Olinde et al. (1998, *). Data points for NH listeners from Gabriel et al. (1992) and Smith-Olinde et al. (1998) studies are plotted as means from the set of listeners.

Multiple statistical tests were done with the data. To assess whether the NH and HI groups performed differently, the independent samples of thresholds measured in each group were compared to test whether the groups had statistically different medians. Wilcoxon rank sum (“Rank Sum,” matlab 2012a) tests were run to evaluate significance. This non-parametric test was used so that it would not be necessary to assume a normal distribution. Separate tests were done to determine, for each group of listeners, the extent to which thresholds measured in a particular task correlated with those for a different task or with hearing level (either at the task frequency or averaged across frequencies). These factors were assessed by calculating Pearson R-squared correlation coefficients and p-values. Log10 (ITD), log10 (ILD), and dB-equivalent-S/N ICC values were used in calculating the correlation coefficients. For all tests, correlations were considered “statistically significant” when the alpha significance level for the correlation coefficients was less than α = 0.05.

III. RESULTS

A. Performance changes over time

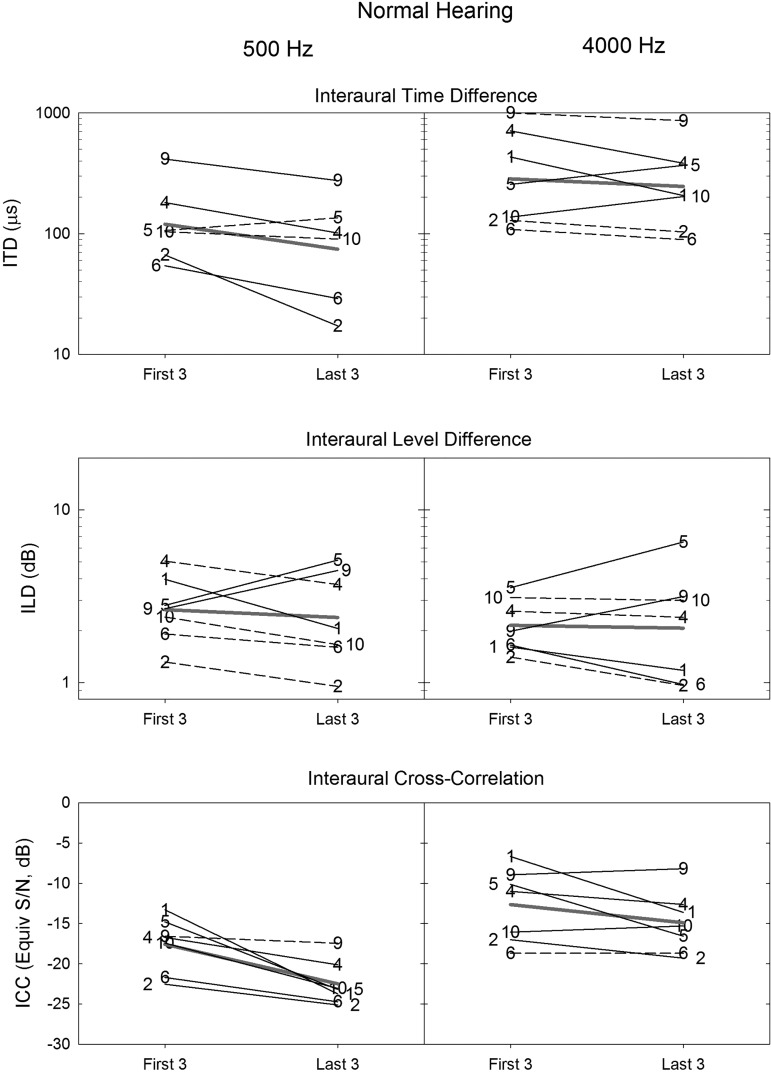

The mean thresholds measured for the NH listeners in the early adaptive tracks are compared to those measured for the same listeners in the late adaptive tracks in Fig. 2. Data are only shown for those listeners for whom the presentation levels remained fixed throughout the entire study. The thresholds measured at low frequency are shown in the left panels, and those measured at a high frequency are shown in the right panels. While most individual subject thresholds showed some degree of improvement between the first three and last three measurements, a few of the individual cases described a loss of sensitivity. Thirty-one improvements were found out of a total of 41. When a one-step criterion was used to denote performance change however (with larger-than-one-step changes denoted by solid rather than dashed lines), 19 cases with improvements were found, along with eight cases of performance becoming worse. The mean thresholds (thick lines) show improvements for all six of the interaural difference sensitivity tasks. The most noticeable improvements occurred for the 500-Hz ICC JND task, where the mean threshold changed by about 4 dB.

FIG. 2.

(Color online) Performance-change data for the NH listeners. First-three and last-three performance thresholds are shown for individual NH listeners using thin lines, with each labeled by subject number. Mean first-three and last-three performance thresholds are shown by thick lines (red if shown in color). Individual and mean performance thresholds are described for interaural time difference sensitivity tasks in the top row, interaural level difference sensitivity tasks in the middle row, and interaural correlation coefficient tasks in the bottom row. Lines for changes exceeding the one-level threshold are solid, those for smaller changes are dashed.

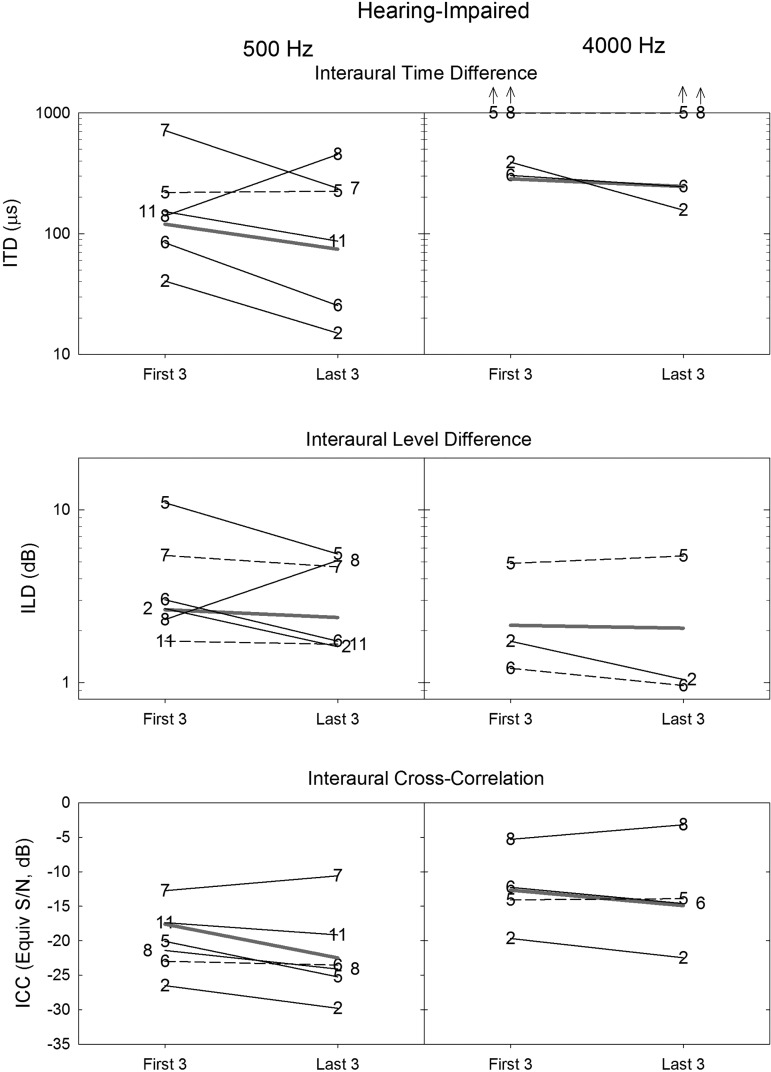

The performance-change data for the HI listeners are shown in Fig. 3. As in Fig. 2, mean thresholds measured at low frequency are shown in the left panels, with high-frequency data shown in the right panels. Out of 27 total cases, it was found performances improved in 19 of the cases. In the cases with the one-step size criterion there were 16 cases of increased sensitivity over time, compared to four cases of reduced sensitivity. The mean thresholds (thick line) show improvements in all of the interaural difference sensitivity tasks. All tasks were similar in that no single task stood out with a clearly larger improvement in mean performance threshold, relative to the other tasks. Comparing NH and HI listeners, the trends and the fraction of subjects showing improvements were similar, even though some of the HI listeners in this study had more experience in psychophysical experiments in general (outside the realm of interaural difference sensitivity measurements) than did the NH listeners. This suggests that the learning observed here may be specific to these interaural discrimination tasks.

FIG. 3.

(Color online) Performance-change data for the HI listeners. The formatting is the same as in Fig. 2.

B. ITD JNDs

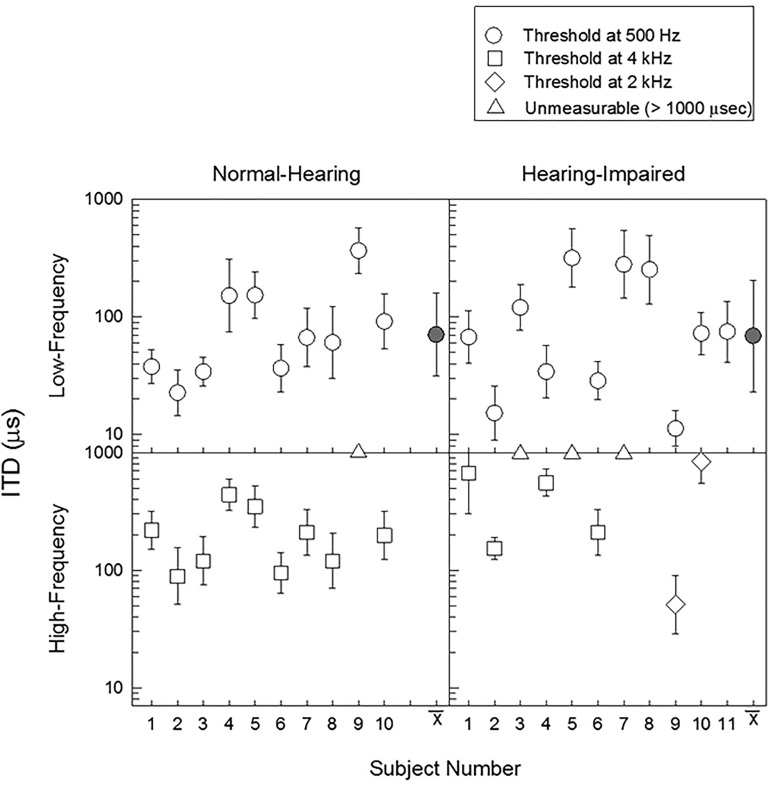

Measured ITD JNDs are shown in Fig. 4 for both NH listeners (left column) and HI listeners (right column). The low-frequency ITD thresholds for the NH listeners (upper-left panel) varied from 22 to 254 μs (mean of 58 μs). Those for the HI listeners (upper-right panel) varied from 11 to 317 μs, with a mean of 68 μs. Overall, the Wilcoxon medians showed no significant difference between the ITD thresholds for the NH and HI listeners (p = 0.597). A greater amount of inter-subject variability was found for the HI listener group than for the NH listener group, consistent with how the lowest and highest overall JNDs were found for the HI listeners.

FIG. 4.

Interaural time difference sensitivity thresholds for normal-hearing (left panels) and hearing-impaired (right panels) listeners. Within each listener group, mean with standard deviation are shown for individual subjects (open symbols) and averaged across subjects (filled symbol). Low frequency data (500 Hz, ○) are plotted on the top row, and high frequency data (4 kHz, ◻; 2 kHz, ⋄, see text for explanation) are plotted on the bottom row. Unmeasurable thresholds (i.e., thresholds greater than 1000 μs) are plotted as triangles at 1000 μs. The mean 500-Hz ITD threshold for the NH listeners was 58 μs, compared with 68 μs for the HI listeners.

High-frequency ITD JNDs are plotted in the lower panels of Fig. 4. High-frequency ITD thresholds for NH listeners (lower-left panel) varied from 90 μs to beyond the limit of our measurements (>1000 μs). Most were in the 100 to 300 μs range. High-frequency thresholds were measured at 4 kHz for seven HI listeners and at 2 kHz for two listeners (lower-right panel). As noted earlier, difficulties imposed by severe losses at the high frequencies kept the experimenter from presenting medium-high comfortable levels within the equipment limitations, and therefore thresholds were measured at 2 kHz in two listeners (HI9 and HI10) and not at all in two listeners (HI8 and HI11). The high-frequency ITD thresholds varied from 50 μs to unmeasurable (above 1000 μs). Most high-frequency ITD JNDs for the HI group were 200 μs or higher, with three listeners above 1000 μs. All listeners (both NH and HI) had larger ITD JNDs at the higher frequency than they did at 500 Hz, as expected due to no phase locking to the stimulus fine-structure at high frequency (e.g., Brughera et al., 2013).

C. ILD JNDs

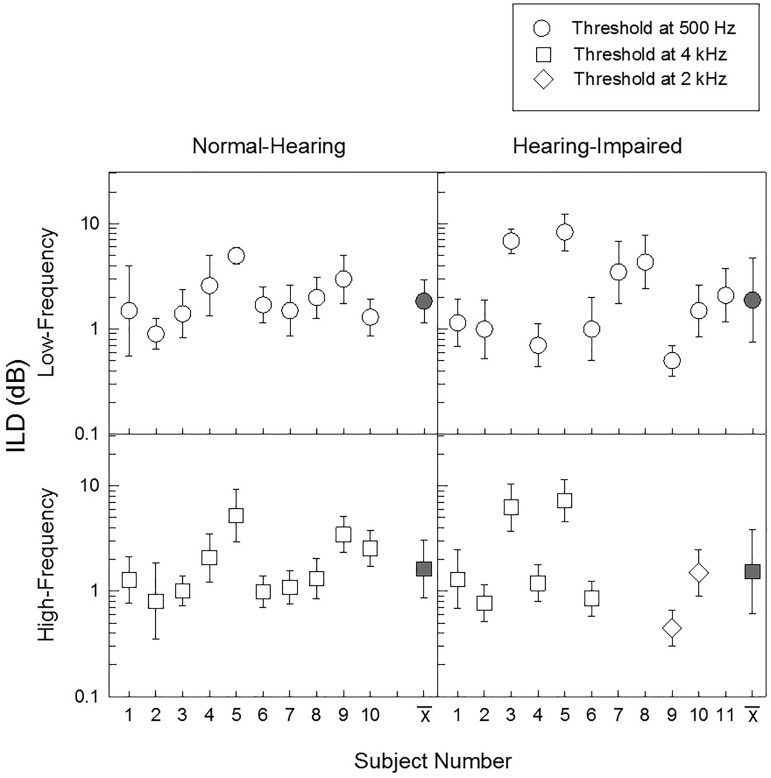

Measured thresholds for ILD discrimination are shown in Fig. 5. Low-frequency ILD thresholds varied from 0.9 to 5.0 dB (mean of 1.9 dB) for the NH listeners (upper-left panel) and from 0.5 to 8.4 dB (mean of 1.9 dB) for the HI listeners (upper-right panel). Thresholds measured at 500 Hz varied over a wide range for both groups of listeners. Those for the groups were not statistically different (p = 0.860 with HI3 and HI5 included in the group, p = 0.304 with those listeners excluded).

FIG. 5.

Interaural level difference sensitivity thresholds for normal-hearing (left panels) and hearing-impaired (right panels) listeners. Within each listener group, mean with standard deviation are shown for individual subjects (open symbols) and for averages across subjects (filled symbols). These mean values include individual values for which thresholds were beyond the roving level limit. Low frequency data (500 Hz, ○) are plotted on the top row, and high frequency data (4 kHz, ◻; 2 kHz, ⋄, see text for explanation) are plotted on the bottom row. The 500-Hz and 4-kHz mean ILD JNDs for the NH group were 1.9 and 1.9 dB, compared with 1.7 and 1.6 dB for the 500-Hz and high-frequency mean ILD JNDs for the HI group.

High-frequency thresholds for the NH listeners (measured at 4 kHz) varied from 0.8 to 5.3 dB (mean of 1.7 dB). For the HI listeners, high-frequency ILD JNDs were measured at 4 kHz in HI1–HI6 and at 2 kHz in HI9 and HI10. ILD JNDs were not measured at high frequency in HI7, HI8, and HI11 because of difficulties imposed by their severe hearing losses, such that if baseline/starting levels were too high, equipment ceiling would be reached. Measured high-frequency ILD JNDs varied from 0.5 to 7.4 dB (mean of 1.6 dB) in the HI listeners.

The mean JNDs for NH and HI listeners were similar, both at 500 Hz and at high frequency, with large overlap in the threshold ranges. For both frequencies, the median (with HI3 and HI5, who had thresholds past the rove limit, included in the group) for the HI listeners was not significantly different from that for the NH listeners (p = 0.860, p = 0.762). For both ILD tasks, the range of measurements was higher for the HI group than for the NH group.

As noted above, measured JNDs were found to be greater than 6 dB for two of the listeners, HI3 and HI5. These measured thresholds exceeded the effectiveness of the 10-dB rove which made it impossible for the listeners to use monaural cues to perform the ILD tasks at criterion performances of less than 5 dB (Gabriel et al., 1992). It is therefore possible that HI3 or HI5 were not sensitive to ILD at all; they may have performed the tasks using only monaural information.

D. ICC JNDs

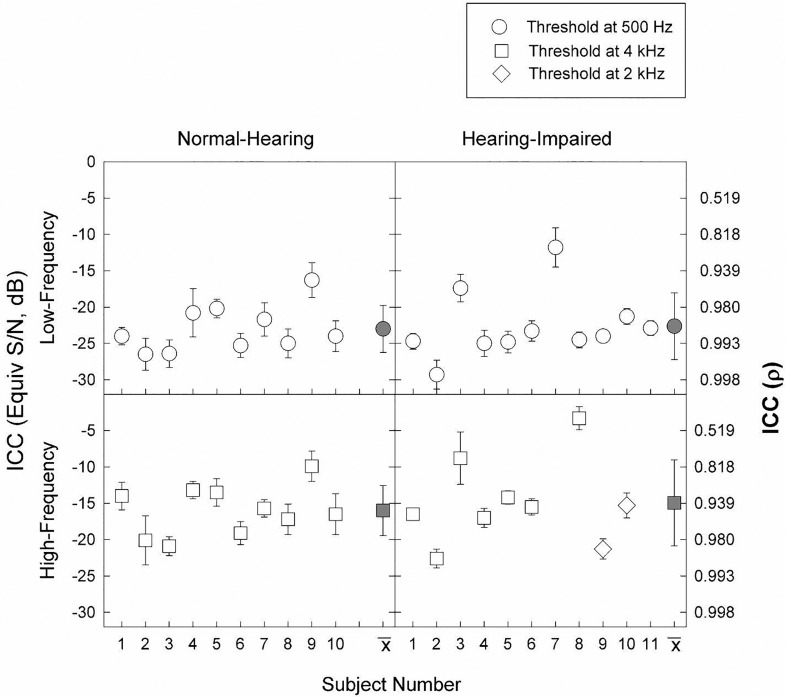

The JNDs for the ICC tasks are shown in Fig. 6. The 500-Hz ICC JNDs for the NH listeners are plotted in the upper-left panels. The measured thresholds varied from −16 to −27 dB equivalent S/N (for correlation coefficients ρ from 0.950 to 0.996). The mean value was −23 dB equivalent S/N. The low-frequency ICC JNDs for the HI listeners are plotted in the upper-right panel. The thresholds for these listeners varied from −12 to −29 dB equivalent S/N (ρ from 0.882 to 0.998) (mean of −22 dB equivalent S/N). The high-frequency ICC JNDs for NH listeners, measured at 4 kHz, are plotted in the lower-left panel. The thresholds varied from −10 dB equivalent S/N (ρ = 0.818) to −21 dB equivalent S/N (ρ = 0.984) (mean of −16 dB equivalent S/N). High-frequency ICC JNDs for HI listeners, measured in seven listeners at 4 kHz and in two listeners at 2 kHz, are plotted in the lower-right panel. Thresholds were not measured in HI7 or HI11, due to difficulties imposed by severe losses in the high frequencies which prohibited the use of medium-high comfortable levels without ceiling being reached. The thresholds varied from −3 dB equivalent S/N (ρ = 0.332) to −21 dB equivalent S/N (ρ = 0.984). The mean was −15 dB equivalent S/N. The Wilcoxon median for the NH group was not significantly different from that for the HI group, neither at 500 Hz nor at high frequency.

FIG. 6.

Interaural cross-correlation thresholds for normal-hearing (left panels) and hearing-impaired (right panels) listeners. Scale on the left gives ICC as equivalent S/N, in dB. Scale on the right, ICC (ρ), provides the corresponding value of the interaural correlation coefficient. Within each listener group, the mean with standard deviation error bars are shown for individual subjects (open symbols) and averaged across subjects (filled symbol). Low frequency data (500 Hz, ○) are plotted on the top row, and high frequency data (4 kHz, ◻; 2 kHz, ⋄, see text for explanation) are plotted on the bottom row. The mean 500-Hz and 4-kHz ICC JNDs for the NH group were −23 and −16 dB, compared with mean 500-Hz and high-frequency ICC JNDs of −22 and −15 dB for the HI group.

For all the listeners, both NH and HI, the high-frequency ICC JNDs were poorer (less negative) than the 500-Hz ICC JNDs. The 4-kHz ICC threshold for HI8 was especially poor, even though the 500-Hz ICC JND for this listener was close to the average among all listeners. For this subject, the high-frequency ITD and ILD JNDs were unable to be measured due to signal level limitations, further highlighting the difficulty this subject had with all tasks measured at high stimulus frequencies.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Performance improvements over time

It was not surprising that the mean thresholds for both subject groups were lower on the final day of testing than on the initial day of testing for the task, given that multiple other studies also found performance thresholds to improve across days of training and testing (e.g., Wright and Fitzgerald, 2001; Ortiz and Wright, 2009; Zhang and Wright, 2009; Ortiz and Wright, 2010). This result was also expected given how it was recently suggested that ICC thresholds might be poorer for untrained than for trained listeners (Goupell and Barrett, 2015). Performance improvements for interaural difference tasks have been attributed to conceptual learning (general task attributes) and stimulus learning (attributes specific to the task at hand) (e.g., Ortiz and Wright, 2009, 2010).

For the NH listeners of the current study, the greatest improvements in mean performance thresholds were found for the 500-Hz ICC task (where performance was initially tested first), and the smallest improvements were found for the 4-kHz ILD task (where performance was initially tested last). Given how the test order was uniform and how the largest improvements were found for the 500-Hz ICC task, it is possible that some of the listeners might have benefited from conceptual learning via first-exposure in the 500-Hz ICC task, so that the first performance thresholds for the other tasks might have been lower (better) than otherwise (i.e., if performance thresholds for that task had been initially measured first). At the same time, the specific extents to which the listeners might have benefited from stimulus learning versus conceptual learning was not isolated in this study since the performances were measured across multiple tasks in each session and since neither the time per session nor the days between measurements were controlled with precision.

B. Sources of performance variability

A large amount of inter-subject performance variability was always measured for a task or subject group (NH or HI), in spite of the training period. This result is not surprising for either subject group given previous outcomes (NH—Koehnke et al., 1986; HI—Gabriel et al., 1992). It follows to wonder whether the inter-subject differences found in the current study were due to differences in listening attentiveness or effort or were found as a result of fundamental differences in interaural difference sensitivity.

It seems that the differences were due to fundamental differences in interaural sensitivity. This inference is made based on evidence from both current and previous studies. In the current study, the geometric standard deviations for the JNDs (plotted in Figs. 4, 5, and 6) were typically small, on the order of only one or two small steps. This suggests a measure of consistency across adaptive tracks for a subject and task and therefore might indicate consistency of effort. Note that relatively small geometric standard deviations were even found for the NH listeners with the high JNDs (for poorest performance) (Fig. 4). Further evidence in support of the individual differences being due to fundamental differences in sensitivity comes from previous studies (Koehnke et al., 1986 for NH; Hall and Fernandes, 1983 for HI) showing large inter-subject variability for interaural difference sensitivity tasks along with small inter-subject variability for monaural-level discrimination tasks. These monaural level tasks controlled for inter-subject differences in general listening effort, at least to a degree.

C. Comparisons with previous data

Of interest is how the performance threshold ranges measured for the current study compared with those measured for previous studies. Training can impact performance, so this section only focuses on the previous studies which used highly trained listeners. Note that for this reason the thresholds from the Koehnke et al. (1995) study were not included in this plot. Even though the methods used for data collection across the current study and the Koehnke et al. (1995) study were highly similar, Koehnke et al. (1995) explicitly stated that they used relatively un-trained listeners because they wanted to determine performance in conditions that are likely to exist in a clinical setting when there is little time for testing each subject. Furthermore, this section also only focuses on the studies using 1/3-octave, Gaussian noises. Current- and previous-study performance data are compared in Fig. 7. The NH and HI data are plotted in adjoining panels for each test and are discussed separately.

1. NH listeners

Koehnke et al. (1986) found there to be high amounts of inter-subject variability across listeners and within tasks when four NH listeners were gathered and performance measured at 500-Hz in discrimination tasks for ITD, ILD, and ICC and at 4 kHz in an ICC discrimination task. The performance threshold ranges from that study were slightly lower (better performance) than those of the current study in both the 500-Hz ITD and ILD tasks. It is possible that these lower ranges may have been the result of the use of the fixed-increment method in which the interaural difference or interaural correlation was steady across trials, as opposed to the use of the adaptive (transformed up-down) method in the current study which leads to interaural differences or interaural correlations that vary across trials.

Note on the other hand that some previous studies showed JNDs to be consistently low for some of the current study's binaural tasks. Consistently low thresholds (for strong performance) were found for the JNDs for the NH listeners in studies like Hawkins and Wightman (1980), Smoski and Trahiotis (1986), Gabriel et al. (1992), and Smith-Olinde et al. (1998). Note that the performances were measured in subject groups of three or less in each of these studies. It is possible that more variability might have been found across the individual subject JNDs for those studies if their subject groups had been larger. Another possible factor is a bias toward keeping subjects who perform well and achieve low thresholds. This seems possible given the low numbers of subjects.

2. HI listeners

The ranges of ITD and ILD JNDs for the current-study HI listeners (at low and high frequencies) were comparable with previous-study JND ranges (see columns for the ITD and ILD JNDs labeled “HI” in Fig. 7). In both the current study and in the previous studies (Hawkins and Wightman, 1980; Smoski and Trahiotis, 1986; Gabriel et al., 1992; Smith-Olinde et al., 1998), most 500-Hz ITD JNDs were between about 20 and 100 μs, while most 4-kHz ITD JNDs between about 100 μs and unmeasurable. The current-study ILD JNDs varied from 1 to 8 dB, including JNDs with dB values above the roving level limit. The individual thresholds in the Gabriel et al. (1992) study varied on a similar 1–8 dB range, also including JNDs above the roving level limit, while the range for the Smith-Olinde et al. (1998) study was about 1–4 dB.

Few ICC JNDs had been previously measured for highly trained HI listeners. Relatively little was therefore known with regards to what to expect for the current study. The JNDs that were measured in the Gabriel et al. (1992) study were higher (in equivalent S/N), corresponding to poorer performance, than those that were measured in the current study. While it surprising that the current-study included better performances than the Gabriel et al. (1992) study, note that the Gabriel et al. (1992) only included four HI listeners.

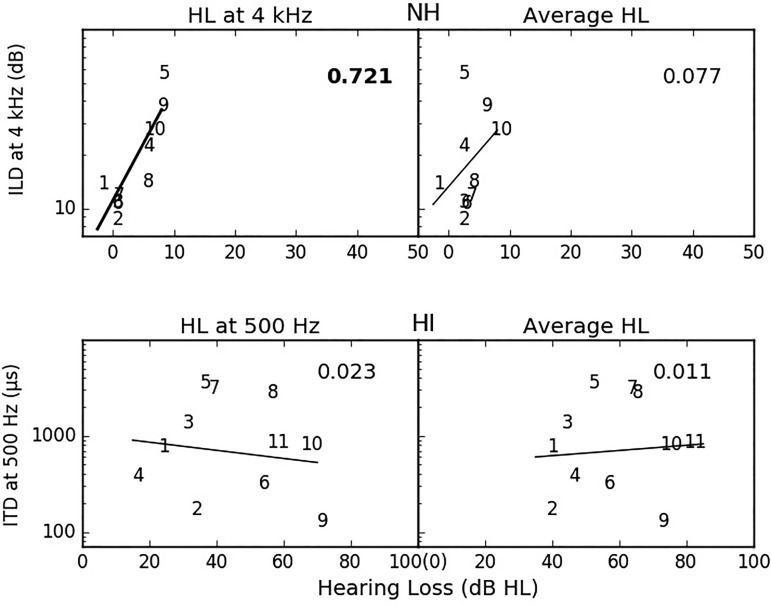

D. Lack of correlation with hearing level

For the NH listeners of the current study, the number of statistical correlations with hearing level depended on frequency. For the 500-Hz stimuli, no significant correlations were found between hearing loss (average HL or HL at the frequency of the task) and JNDs for any variable (neither ITD nor ILD nor ICC). (Refer to Table III.) For the 4-kHz stimuli, a significant correlation was found between hearing level at 4 kHz and 4-kHz ILD JND, as shown in the upper panel of Fig. 8. It is not surprising that few overall correlations were found for the NH group, when considering two factors. First, only small individual differences were found across the audiometric thresholds for this group. Second, there was no a priori reason for expecting high numbers of statistically significant correlations between hearing loss and binaural JND for this group.

TABLE III.

Summary of correlations. R-squared and p values are plotted in the table (R-squared; p format). Significant correlations (p < 0.05) are in bold. Just-noticeable differences beyond the rove limit or limit of measurability were excluded.

| Normal hearing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 Hz | 4 kHz | ||||||

| ITD | ILD | ICC | ITD | ILD | ICC | ||

| Average HL | 0.220; 0.171 | 0.005; 0.844 | 0.081; 0.423 | 0.016; 0.742 | 0.077; 0.439 | 0.011; 0.771 | |

| HL 500 | 0.115; 0.335 | 0.009; 0.797 | 0.030; 0.632 | ||||

| HL 4 kHz | 0.253; 0.167 | 0.721; 0.002 | 0.336; 0.079 | ||||

| 500 Hz | ITD | — | 0.604; 0.008 | 0.878; <0.001 | 0.810; 0.002 | 0.749; 0.001 | 0.751; 0.001 |

| ILD | — | 0.548; 0.014 | 0.473; 0.028 | 0.684; 0.003 | 0.481; 0.013 | ||

| ICC | — | 0.925; <0.001 | 0.587; 0.009 | 0.861; <0.001 | |||

| 4 kHz | ITD | — | 0.603; 0.008 | 0.887; <0.001 | |||

| ILD | — | 0.562; 0.013 | |||||

| Hearing impaired | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 Hz | High frequency | ||||||

| ITD | ILD | ICC | ITD | ILD | ICC | ||

| Average HL | 0.001; 0.599 | 0.127; 0.346 | 0.077; 0.408 | 0.023; 0.772 | 0.026; 0.762 | 0.033; 0.641 | |

| HL 500 | 0.023; 0.656 | 0.048; 0.573 | 0.002; 0.910 | ||||

| HL 4 kHz | <0.001; 0.987 | 0.002; 0.985 | 0.002; 0.913 | ||||

| 500-Hz | ITD | — | 0.860; <0.001 | 0.267; 0.103 | 0.899; 0.013 | 0.877; 0.006 | 0.654; 0.008 |

| ILD | — | 0.256; 0.165 | 0.527; 0.102 | 0.603; 0.069 | 0.788; 0.007 | ||

| ICC | — | 0.108; 0.524 | 0.090; 0.566 | 0.256; 0.164 | |||

| High-Freq | ITD | — | 0.992; <0.001 | 0.566; 0.084 | |||

| ILD | — | 0.541; 0.095 | |||||

FIG. 8.

Scatter plots of selected interaural difference thresholds as a function of hearing loss (hearing level in dB) at the task frequency in the left panels and as a function of average hearing loss in the right panels. (Average hearing loss was calculated using frequencies at octave intervals from 250 Hz to 4 kHz.) Upper panels show 4-kHz ILDs for normal-hearing listeners and the lower panels show 500-Hz ITD JNDs for the HI listeners. R-squared values are plotted in the upper-right corner of each panel. R-squared values are in bold and fit lines are thick when correlations are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

For the HI listeners, no significant correlations were found for interaural difference sensitivity as a function of hearing level (Table III), neither for average hearing level (among 250–8000 Hz) nor for hearing level at the stimulus frequency. This result, like for the NH listeners, was un-surprising. Note that the HI group included listeners with mild losses and poor interaural difference sensitivity thresholds, as well as listeners with severe losses and strong interaural difference sensitivity thresholds. Note that one of the listeners with severe loss and good binaural performance was HI9. This listener was also the only one in this study who was who was older than 40 at the time of the study. The result that there were no correlations was also not surprising given previous data (Hawkins and Wightman, 1980; Smoski and Trahiotis, 1986; Koehnke et al., 1995; Smith-Olinde et al., 1998; Hawley, 2000) showing little relationship between hearing level and interaural difference JNDs. The lower panels of Fig. 8 show an example of a lack of significant correlation between low-frequency ITD JND and hearing level for the current-study HI listeners, including HL at 500 Hz (left panel) and HL averaged among the 250–8000 Hz bands (right panel).

E. Correlations across tasks

The extent to which performances correlated across tasks is discussed in this section for the two listener groups. The correlation coefficient across tasks for a group is a barometer of the degree to which new (or redundant information) is added for the listeners of the group when performance is measured in a second task (after being done so for the first task). Knowing the degree of redundancy might be helpful for example, for a clinician or scientist who hopes to characterize performance thresholds for a listener group but within a time-constraint. High amounts of training are involved, and the overall process might be expedited if a task is removed from the testing regimen. A task is described as redundant in this section when there is a statistically significant correlation between two tasks, when the rank orders are similar across two tasks or when performance scores for all subjects (like for ILD across frequency) are similar across two tasks.

1. Within-task correlations across frequency

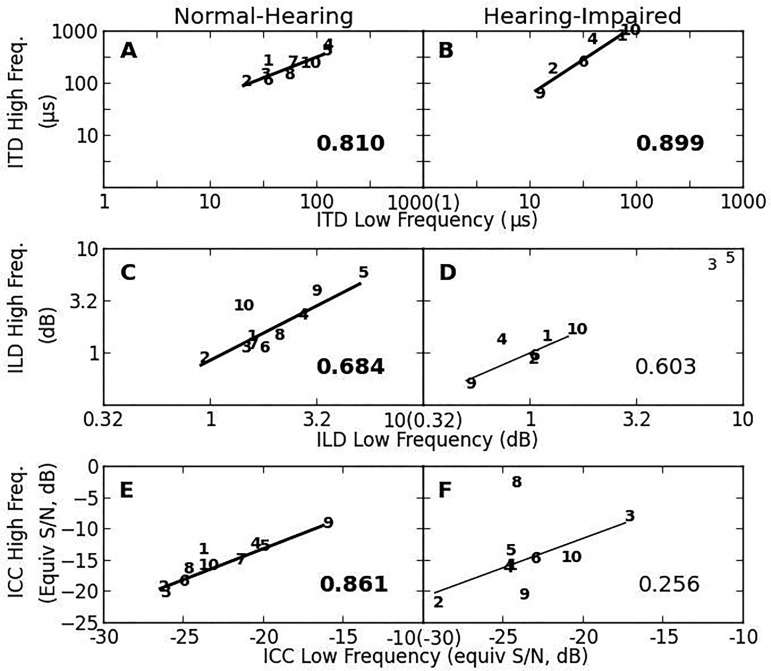

Just-noticeable differences for ITD, ILD or ICC at high frequency (4 kHz) are plotted in Fig. 9 as a function of the low-frequency (500 Hz) JNDs for the same task. Results for the NH listeners are plotted in the left panels, while those for the HI listeners are plotted in the right panels. The subjects for whom the thresholds were unmeasurable or beyond the rove limits were excluded when the correlation coefficients were determined.

FIG. 9.

Within-task frequency dependence of JNDs for ITD (top), ILD (middle), and ICC (bottom) for NH listeners (left panels) and HI listeners (right panels). For each task, performance for high frequency stimuli is plotted against performance for low frequency stimuli. R-squared values are plotted in the lower-right corner of each panel. R-squared values are bold and fit lines are thick when correlations are statistically significant (p < 0.05). For ITD JNDs for both groups, correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.05). For ICC and ILD JNDs, thresholds significantly correlated across frequency for the NH group (p < 0.05) but not for the HI group (p > 0.05). Subject numbers for listeners included in the correlation are in bold. Those for listeners excluded in the correlation are not in bold.

a. ITD.

Both subject groups showed significant correlations between ITD JND at low-frequency and ITD JND at high-frequency (p = 0.002, NH; p = 0.013, HI). This suggests that redundant information was added for both groups through the second ITD sensitivity task (upper panels, Fig. 9). Note, however, that while nine (of ten) listeners were included in the NH correlation, only six (of 11) were included for the HI correlation. Given this relatively low “N” for the HI listeners, caution is warranted for this group with respect to the possibility of a type I error (“false positive”).

While some previous-study data agree with the high correlations found here that suggest that redundant information was added for both groups with respect to cross-frequency ITD, some previous studies (for HI listeners) do not agree. While some consistency was found with respect to the rank orders in ITD across frequency for the HI group in the Gabriel et al. (1992) study, the Koehnke et al. (1995) and Smith-Olinde et al. (1998) data on the other hand show some inconsistency, for example. This inconsistency may have been the result of some HI listeners performing better when phase-locking to fine-structure was involved and others performing better when it was not involved. The lack of consistency may have been the result of stimulus level (SL) selection difficulty for the experimenter. When a listener has a sloping loss such that the audiometric thresholds vary with frequency-band, the experimenter might be faced with the decision to either equate SL or equate perceived loudness across bands. Interaural time difference thresholds can be affected by factors like SL and loudness (Hawkins and Wightman, 1980; Dietz et al., 2013).

b. ILD.

Like what was found for the ITD tasks, the current study showed significant correlations between ILD JNDs at low and high-frequency for the NH group (p = 0.003). The across-frequency correlation for ILD for the HI group was not statistically significant (p = 0.069) when HI3 and HI5 were excluded due to their JNDs being beyond the roving level. The correlation coefficient for the group of six HI listeners was high, however (R2 = 0.603) [Fig. 9(D)]. This correlation might have become statistically significant if HI4's thresholds had been more similar to one another across frequency, even though the thresholds for this listener were only apart by 0.5 dB for the two frequencies. With regards to the roving level limit, it is not clear how much HI3 or HI5 might have used binaural information to perform the ILD tasks at the two frequencies. It is still worth noting however that the cross-frequency correlation for the HI group becomes statistically significant when those two listeners are included in the HI group for both tasks (R2 = 0.603, p < 0.001). Observe that, in light of the small number of HI listeners found for this correlation, the possibility of a type I error (false positive) should be noted.

Previously published ILD threshold data largely agree that fairly redundant information is added about how sensitive listeners for a group are to ILDs when performance is measured at a second frequency. Kinkel (1990) found significant correlations of ILD across frequency for both NH and HI listeners. Along these lines, all listeners (both NH and HI) of the Smith-Olinde et al. (1998) and Hawley (2000) studies had JNDs that were within 2 dB of one another when compared across frequency. There are accounts however showing ILD JNDs for HI listeners that differed by large amounts when compared across frequency (Gabriel et al., 1992).

Some of the same measurement difficulties with stimulus level selection discussed for ITD measurements of our study might have also applied for the ILD measurements of our study. Along these lines, note that HI4 (whose data were discussed earlier in this section) had a very sloping loss. This listener's average loss at 500 Hz was 15 dB, compared with 65 dB at 4 kHz. While this listener's thresholds were relatively low at the 4 kHz ILD task (1.2 dB) where the stimulus levels were limited due to the listener having a relatively low discomfort threshold, 1.2 dB is poorer than the 0.7 dB JND that was found for this listener at 500 Hz. A significant correlation might have been found for the HI group had this listener's ILD JNDs been more similar across frequency.

c. ICC.

Just-noticeable differences for ICC were significantly correlated across frequency for the NH group (p < 0.001), but not for the HI group (p = 0.164) [cf. Figs. 9(E) and 9(F) and Table III]. One might suspect that a factor underlying the lack of significant correlation may have been that performances for HI9 and HI10 were measured at 2 kHz (which might have led to better performance) rather than at 4 kHz (cf. NH performances in Gabriel et al., 1992); however, when HI9 and HI10 listeners were taken out of the computation, the relationship was still non-significant (p = 0.158).

Few previous studies have weighed in on whether one should or should not expect for ICC to correlate across frequency for NH or HI listeners. The few existing reports do agree, however, with how the current study found ICC to be redundant across frequency for NH but not HI listeners. For example, while Koehnke et al. (1986) found that each of the four NH listeners either performed well at both frequencies or performed poorly at both frequencies, Gabriel et al. (1992) and Koehnke et al. (1995) both found that the rank orders of subject performances to differ across the two center-frequencies for the HI listeners.

2. Correlations across different tasks involving ITD, ILD, and ICC

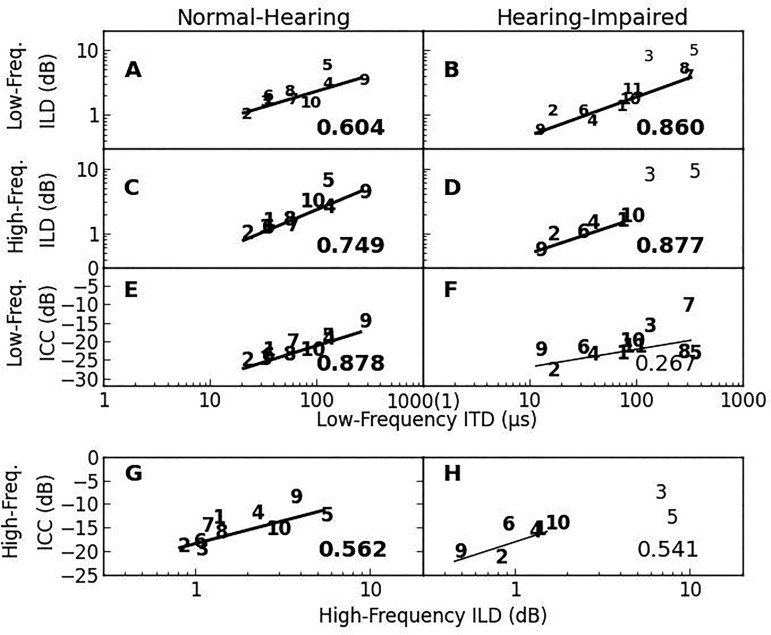

Thresholds measured for a task (ITD, ILD, or ICC) were also compared to those measured for a different task. The resulting correlation coefficients are described in Table III, with R2 and p-values bolded when statistically significant relationships were found. Scatter plots for some of the relationships are shown in Fig. 10. All data points beyond the unmeasurability criterion or beyond the rove limit (indicated by non-bold numerical identifiers) were excluded from the analysis.

FIG. 10.

Across-task correlations among ITD, ILD, and ICC discrimination tasks for normal hearing listeners (left panels) and hearing impaired listeners (right panels). The correlations for ILD for low and high frequency stimuli and for ICC for low frequency stimuli are shown in the upper panels as a function of ITD for low frequency stimuli. ICC for high frequency stimuli as a function of ILD for high frequency stimuli are plotted in the bottom panels. R-squared values are described in the lower-left of each panel, with those in bold when denoting significant correlations. Statistically significant correlations for both groups were found for ILD at both low and high frequency as a function of low-frequency ITD (p < 0.05). The same was true for low-frequency ICC as a function of low-frequency ITD for the NH group, but not for the HI group. High-frequency ICC significantly correlated with high-frequency ILD for the NH group (p < 0.05). Subject numbers for listeners included in the correlation are in bold. Those for listeners excluded in the correlation are not in bold.

a. ITD vs ILD JNDs.

ITD JNDs for a given frequency were always significantly correlated with ILD JNDs (within or across frequency) for the NH group (Table III, selected examples shown in panels A and C of Fig. 10). While significant correlations were often also found for the HI group, ILD at low frequency did not correlate with ITD at high frequency for this group (p = 0.102). Note that caution is warranted around the significant correlations found for the HI group, given the possibility of false positives for groups with limited numbers of subjects. Overall, the data suggest that highly redundant information is added when performances are measured in new ITD and ILD JND measures for NH or HI listeners.

Much of the previous-study data agree that highly redundant information is provided from these two measures for the two subject populations. Koehnke et al. (1986) and Hawley (2000), for example, found the rank-orders to be highly similar across tasks for the NH listeners for these measures. Also note that all HI listeners (when the SL was 20 dB or greater for all tasks) who performed well in the low-frequency ITD tasks also did so in the ILD tasks (Gabriel et al., 1992, Koehnke et al., 1995, Smith-Olinde et al., 1998 and Hawley, 2000). High-frequency JNDs have often been beyond the limit of measurability on the other hand, making cross-task comparison relatively more difficult for previous studies.

b. ICC vs ITD or ILD.

The ICC thresholds for the NH listeners always significantly correlated with the ITD or ILD thresholds (cf. Table III and the examples in panels E and G in Fig. 10). This suggests that highly redundant information was added for these listeners when performances were measured in each of the new measures. Koehnke et al. (1986) data agree in that all the subjects in that study either performed well or poorly across in each of the different measures. The finding is also supported by acoustical analysis by Goupell and Hartmann (2006), who described how the ICC stimulus variable ρ covaries with the size of ITD and ILD fluctuations.

For the HI listeners of this study, the ICC JNDs were significantly correlated with the ITD or ILD JNDs less often than for the NH listeners of this study. For these HI listeners, significant correlations were found for only two of the eight cases (Table III). Two example cases that did not reach significance are plotted in Fig. 10: low-frequency ICC as a function of low frequency ITD (p = 0.103, panel F), and high frequency ICC as a function of high frequency ILD (p = 0.095, panel H). For the first of these two non-significant relationships (the one with low-frequency ITD), note a few data points off the best-fit line. Hearing-impaired subject 2, HI5 and HI8 all had ICC JNDs at 500 Hz that were better than predicted by this line, while those HI3 and HI7 both had 500-Hz ICC JNDs that were poorer-than-predicted from the line. The lack of many significant correlations for the ICC task for the HI group makes sense given the performance thresholds of HI5 and HI8. Both performed well in 500 Hz ICC but relatively poorly in the ITD and ILD tasks (most of HI8s high-frequency thresholds were above 1000 μs and not measured). The results for the HI group that there were correlations with ICC involved is consistent with previous findings by Gabriel et al. (1992) and Koehnke et al. (1995). The rank orders for the HI group were always different across two tasks in those studies whenever ICC was involved.

V. CONCLUSIONS

The current study sought to address some unanswered questions involving how to best measure binaural abilities. The study included 21 listeners, 20 of whom were younger than forty years old, and 11 of whom had hearing impairments. The listeners were highly trained in different tasks that measure sensitivity to interaural differences cues (ITD, ILD, and ICC discrimination). Overall, positive effects of training were found in that the mean JNDs were lower at the end of the testing period than at the beginning for all tasks and for both subject groups. This was found in spite of the fact that the thresholds for some of the individuals were affected very little by training.

A large amount of inter-subject variability was measured in thresholds for many of the tasks and for both subject groups, even though, as expected, more inter-subject variability was usually found for the HI listeners than for the NH listeners. The broad range of interaural difference sensitivity thresholds measured for the HI listeners suggests that some of the HI listeners might benefit more than others from having amplification strategies that preserve interaural differences.

The interaural difference sensitivity thresholds (JNDs) for the HI listeners were never correlated with any measure of hearing level. Such measures included hearing level at the test frequency and average hearing level. Along these lines, observe that large hearing losses do not preclude HI listeners from being sensitive to binaural information. Observe for example, that one of the study's best interaural difference performers was HI9, whose hearing losses were severe. Also relevant to the discussion of the importance of hearing loss, note that poor interaural difference sensitivity thresholds were found for some of the NH listeners compared to those for the other listeners, in spite of normal hearing thresholds. For the NH listeners, there was significant correlation between the ILD JND and the high-frequency detection threshold, even though the detection thresholds were in the normal range for all listeners (less than 10 dB HL).

High degrees of correlation were found among the JNDs at low and high frequency both within and across tasks. Significant correlations were found across the ITD, ILD and ICC tasks for the NH listeners. Overall, 15 significant correlations were found for this group. For the HI listeners, significant correlations across frequency were found for almost all of the ITD and ILD tasks, but only a few significant correlations were found for the ICC tasks. Six significant correlations were found for this group, by comparison. The findings suggest that for well-trained NH or HI listeners much can be surmised about sensitivity to ITDs and ILDs from a more limited set of measurements (i.e., only testing low frequency stimuli or only testing ILD task). However, the findings suggest that for HI listeners, additional (new) information is often obtained by measuring ICC thresholds in addition to measuring sensitivity to ITD and ILD. Most, but not all current-study findings regarding extent of (or lack of) redundant information added were supported by previous-literature findings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Virginia Best and Gerald Kidd for their input in the analysis of the data and for their suggestions for the reporting of the data. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, NIDCD, specifically R01 Grant No. DC000100. We also thank the reviewers for many constructive and useful suggestions.

Footnotes

In order to present ITDs with small increments between values, the experimental software program was modified so the sampling rate would be 156.25 kHz for all intervals in any trials in which the ITD was 30 μs or below, and 100 kHz for all intervals in trials in which the ITD was higher than 30 μs.

There were exceptions to the standard of presentation levels being maintained throughout the study for all subjects. First, different levels were used for some of these subjects (NH 3,7,8; HI 3,4,9,10) during pilot testing. Second, for some HI listeners (HI1), levels were adjusted as a result of unstable performance tracks being gathered at a particular stimulus level in first block for some tasks.

References

- 1. Bernstein, L. R. , Trahiotis, C. , and Hyde, E. L. (1998). “ Inter-individual differences in binaural detection of low-frequency or high-frequency tonal signals masked by narrow-band or broadband noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 2069–2078. 10.1121/1.421378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brughera, A. , Dunai, L. , and Hartmann, W. M. (2013). “ Human interaural time difference thresholds for sine tones: The high-frequency limit,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 2839–2855. 10.1121/1.4795778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colburn, H. S. , and Trahiotis, C. (1991). “ Effects of noise on binaural hearing,” in Noise-Induced Hearing Loss, edited by Dancer A., Henderson D., Salvi R., and Hamernik R. ( Mosby, St. Louis: ), Chap. 26. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dietz, M. , Bernstein, L. R. , Trahiotis, C. , Ewert, S. D. , and Hohmann, V. (2013). “ The effect of overall level on sensitivity to interaural differences of time and level at high frequencies,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. (1), 494–502. 10.1121/1.4807827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durlach, N. I. , Gabriel, K. J. , Colburn, H. S. , and Trahiotis, C. (1986). “ Interaural correlation II. Relation to binaural unmasking,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 1548–1557. 10.1121/1.393681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Durlach, N. I. , Thompson, C. L. , and Colburn, H. S. (1981). “ Binaural interaction in impaired listeners,” Audiology , 181–2011. 10.3109/00206098109072694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gabriel, K. J. (1983). “ Binaural interaction in hearing-impaired listeners,” Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gabriel, K. J. , and Colburn, H. S. (1981). “ Interaural correlation discrimination: I. Bandwidth and level dependence,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 1394–1401. 10.1121/1.385821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gabriel, K. J. , Koehnke, J. , and Colburn, H. S. (1992). “ Frequency dependence of binaural performance in listeners with impaired binaural hearing,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 336–346. 10.1121/1.402776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goupell, M. J. , and Barrett, M. E. (2015). “ Untrained listeners experience difficulty detecting interaural correlation changes in narrowband noises,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , EL120–EL125. 10.1121/1.4923014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goupell, M. J. , and Hartmann, W. M. (2006). “ Interaural fluctuations and the detection of interaural incoherence: Bandwidth effects,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 3971–3986. 10.1121/1.2200147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goupell, M. J. , and Litovsky, R. Y. (2014). “ The effect of interaural fluctuation rate on correlation change discrimination,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. , 115–129. 10.1007/s10162-013-0426-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hall, J. W. , and Fernandes, M. A. (1983). “ Temporal integration, frequency resolution, and off-frequency listening in normal-hearing and cochlear-impaired listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 1172–1177. 10.1121/1.390040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hartmann, W. M. , and Cho, Y. J. (2011). “ Generating partially correlated noise—A comparison of methods,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 292–301. 10.1121/1.3596475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hausler, R. , Colburn, S. , and Marr, E. (1983). “ Sound localization in subjects with impaired hearing,” Acta Otolaryngol. Suppl. , 1–61 10.3109/00016488309105590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hawkins, D. B. , and Wightman, F. L. (1980). “ Interaural time discrimination ability of listeners with sensorineural hearing loss,” Audiology , 495–507. 10.3109/00206098009070081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hawley, M. L. (2000). “ Speech intelligibility, localization and binaural hearing in listeners with normal and impaired hearing,” Doctoral dissertation, Boston University, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holube, I. (1993). “ Experimente and modellvorstellungen zur psychoakustik und zum sprachverstehen bei normal- und schwerhorigen” (“Experimental and model results for psychoacoustics and for speech processing for normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners”), Ph.D. dissertation, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fachbereiche, Universitat Gottingen, Gottingen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kinkel, M. (1990). “ Zusammenhang vershiedener parameter des binauralen horens bei hormal- und schwerhorigen” (“Relationships between different parameters of binaural hearing for normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners”), Doctoral dissertation, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftichen Fachbereiche, Universitet Gottingen, Gottingen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koehnke, J. K. , Colburn, H. S. , and Durlach, N. I. (1986). “ Performance in several binaural-interaction experiments,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 1558–1562. 10.1121/1.393682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koehnke, J. K. , Passaro Culotta, C. , Hawley, M. L. , and Colburn, H. S. (1995). “ Effects of reference interaural time and intensity differences on binaural performance in listeners with normal and impaired hearing,” Ear. Hear. , 331–352. 10.1097/00003446-199508000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kujawa, S. G. , and Liberman, M. C. (2009). “ Adding insult to injury: Cochlear nerve degeneration after ‘temporary’ noise-induced hearing loss,” J. Neurosci. , 14077–14085. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2845-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levitt, H. (1971). “ Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 467–477. 10.1121/1.1912375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moore, B. C. J. , Glasberg, B. R. , Hess, R. F. , and Birchall, J. P. (1985). “ Effects of flanking noise bands on the rate of growth of loudness of tones in normal and recruiting ears,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 1505–1515. 10.1121/1.392045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ortiz, J. A. , and Wright, B. A. (2009). “ Contributions of procedure and stimulus learning to early, rapid perceptual improvements,” J. Exp Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. , 188–194. 10.1037/a0013161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ortiz, J. A. , and Wright, B. A. (2010). “ Differential rates of consolidation of conceptual and stimulus learning following training on an auditory skill,” Exp. Brain Res. , 441–451. 10.1007/s00221-009-2053-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saunders, G. H. , and Haggard, M. P. (1989). “ The clinical assessment of obscure auditory dysfunction—1. Auditory and psychological factors,” Ear Hear. , 200–208. 10.1097/00003446-198906000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith-Olinde, L. , Koehnke, J. , and Besing, J. (1998). “ Effects of sensorineural hearing loss on interaural discrimination and virtual localization,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 2084–2099. 10.1121/1.421355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smoski, W. J. , and Trahiotis, C. (1986). “ Discrimination of interaural temporal disparities by normal-hearing listeners and listeners with high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 1541–1547. 10.1121/1.393680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Strelcyk, O. , and Dau, T. (2009). “ Relations between frequency selectivity, temporal fine-structure processing and speech reception in impaired hearing,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. , 3328–3345. 10.1121/1.3097469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wright, B. A. , and Fitzgerald, M. B. (2001). “ Different patterns of human discrimination learning for two interaural cues to sound source localization,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. , 12307–12312. 10.1073/pnas.211220498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yost, W. A. (1981). “ Lateral position of sinusoids presented with interaural intensive and temporal differences,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. (2), 397–409. 10.1121/1.386775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]