Highlights

-

•

RCC is the predominant primary tumor for isolated pancreatic metastases.

-

•

Pancreatic metastases from RCC generally tends to slow growth and indolent behavior.

-

•

Surgical resection may be curative and should be considered in selected patients.

-

•

It is still controversial whether to perform typical or atypical surgical procedures.

-

•

Pancreatic metastasis after a prolonged period may imply change in tumor biology.

Keywords: Pancreatic metastasis, Renal cell carcinoma, Surgical resection

Abstract

Introduction

Pancreatic metastases are uncommon and only found in a minority of patients with widespread metastatic disease at autopsy. The most common primary cancer site resulting in pancreatic metastases is the kidney, followed by colorectal cancer, melanoma, breast cancer, lung carcinoma and sarcoma.

Presentation of case

Herein, we report a 63-year-old male patient who presented −3.5 years after radical nephrectomy performed for renal cell carcinoma (RCC)-with a well-defined lobular, round mass at the body of the pancreas demonstrated by abdominal Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). The patient underwent distal pancreatectomy combined with splenectomy and cholecystectomy. Histopathological examination revealed clusters of epithelial clear cells, immunohistochemically positive for RCC marker, and negative for CD10 and CA19-9. A final diagnosis of clear RCC metastasizing to pancreas was obtained in view of the past history of RCC, microscopy and the immunoprofile. This was the second metachronous disease recurrence after a previous metastatic involvement of the liver, developed 19 months from the initial diagnosis. The patient has remained well at a 6 month follow up post-resection.

Discussion

Solitary pancreatic metastases may be misdiagnosed as primary pancreatic cancer. However, imaging including computed tomography (CT) and MRI, may discriminate between them. Surgical procedures could differentiate solitary metastasis from neuroendocrine neoplasms. The optimal resection strategy involves adequate resection margins and maximal tissue preservation of the pancreas.

Conclusion

Recently, an increasing number of surgical resections have been performed in selected patients with limited metastatic disease to the pancreas. In addition, a rigid follow-up scheme, including endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and CT is essential give patients a chance for a prolonged life.

1. Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for approximately 2% of all adult malignancies and represents the third most common tumor of genitourinary tract affecting 115,200 new cases and 49,000 deaths in Europe [1]. RCC behavior is variable; up to 20% of cases may have periods of slow tumor growth or stability lasting many years. In the meantime, 20%–30% of patients are diagnosed with metastases at presentation, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10% once metastases spread. Nevertheless pancreas is an unusual localization of metastatic disease, the kidney being the most common primary cancer site resulting in an isolated pancreatic metastasis which can occur a long time period after nephrectomy [2]. Patients are usually asymptomatic or can present with weight loss, jaundice, abdominal pain, or pancreatitis related to pancreatic duct obstruction [3].

Only few cases with pancreatico-duodenal metastasis were described in the literature in which upper gastrointestinal bleeding was the first manifestation of malignant recurrence [4]. The long disease free interval, from the time of nephrectomy to the diagnosis of metastasis, indicates a biological pattern of slow growth, favouring local surgical resection. Therefore a long follow up is indicated in patients with RCC [5]. At present, data are lacking on the treatment of solitary pancreatic metastases of RCC with novel targeted agents [6]; nevertheless, it may be reasonable to reserve this medical approach for patients with distant lesions outside the pancreas.

2. Methods

This work has been reported in line with the CARE Guidelines [7].

3. Case presentation

A 63-year-old male underwent a right sided radical nephrectomy for a RCC measuring 8 × 7 × 4 cm diagnosed in May 2012. The tumor, with a Fuhrman nuclear grade of II, was confined to the kidney. No vascular or lymph node involvement was revealed. The stage of the disease at the initial diagnosis was II. 19 months later, the patient relapsed with a lesion measuring 3.5 × 2.5 × 1.3 cm in the posterior surface of the liver. On the basis of these findings, a partial hepatectomy with resection of segment VIII of the liver was performed and no subsequent pharmacological intervention was provided. In October 2015, the patient was admitted with right upper quadrant pain and jaundice. There was no history of a change in bowel habit, GI bleeding, pancreatitis, liver or gallbladder disease; nevertheless, recent weight loss of about 2 kg as well as colic abdominal pain that resolved spontaneously 2 months earlier, were reported. Physical examination revealed normal bowel sounds, deep jaundice and mild tenderness in the epigastrium and right upper quadrant, without evidence of peripheral lymphadenopathy, palpable mass or hepatosplenomegaly.

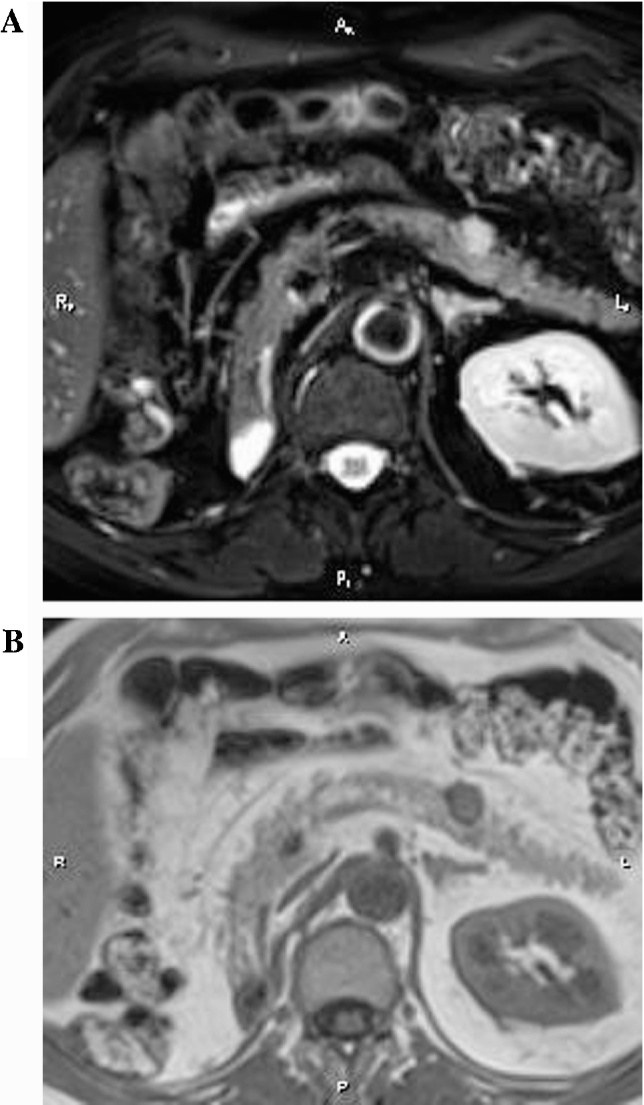

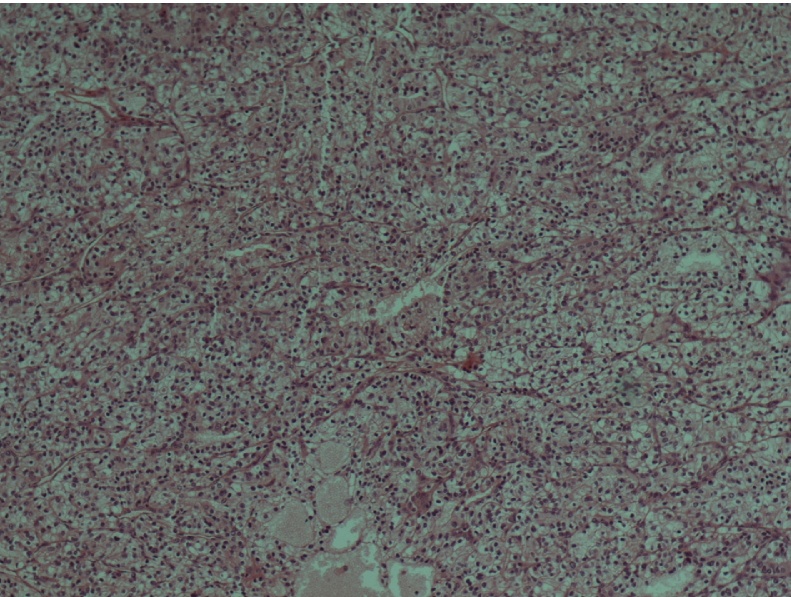

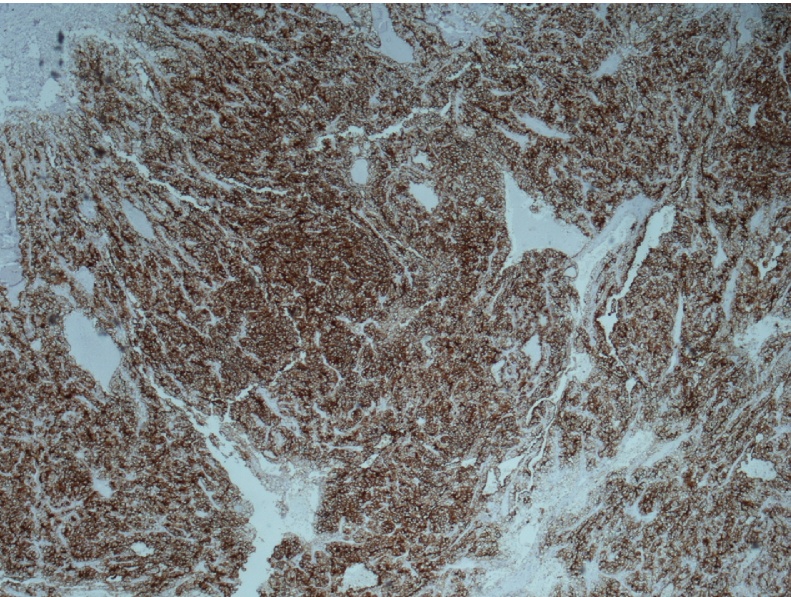

Magnetic Reverse Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed gallbladder stones and further assessment with an abdominal MRI demonstrated the presence of a well-defined lobular, round mass at the body of the pancreas measuring 1,4 × 1,3 × 1,5 cm (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of upstream pancreatic duct dilation or signs of lymphatic infiltration. EUS confirmed the above data and a double EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) was performed with a 22G biopsy needle. Subsequent cytologic examination of the specimen revealed a neoplastic population consisting of small and medium-sized malignant cells with scant cytoplasm and various-sized hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 2). The performed immunohistochemical analysis of tumor cells was positive for RCC marker and negative for CD10 and CA19-9 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

A and B: T2 weighted with Fat saturation image (Fig. 1A) and T1 weighted (Fig. 1B) in axial plane at the same level of pancreas body. The lesion is depicted as a high signal intensity and low to intermediate respectively, nodule. Part of the lesion is protruding out of the pancreatic body frontal contour.

Fig. 2.

Clear cell renal carcinoma composed of nests of cells with clear cytoplasm (×100).

Fig. 3.

CD10 positive membrane immunostaining in clear cell renal carcinoma (×40).

Taking into consideration the patient’s medical history, this occupying lesion in the body of the pancreas was suggestive of metastasis from RCC. The patient underwent distal pancreatectomy combined with splenectomy and cholecystectomy. Due to the preceding surgical operation, adjuvant administration of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) was not indicated. Therefore, the management of the patient was restricted to life-long monitoring and no signs of disease progression were detected in his recent clinical and radiological assessment six months post-resection.

4. Discussion

Pancreatic metastases are rare and account for only 2–5% of detected lesions in this organ. RCC metastasizes to the pancreas with a slightly more common incidence compared to other tumors and this spread could occur as late as 10–32 years. Preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic metastasis is a matter of challenge. An accurate histologic diagnosis of RCC spreading secondarily to the pancreas is paramount in proper management, especially in the absence of a clinically relevant history. The clinical characteristics of these metastatic lesions include abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia and jaundice, though the majority of patients are asymptomatic and occasionally found in follow-up. They present with an indolent behavior and have better prognosis than pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Prognostic factors correlated with impaired survival among these patients are the presence of symptoms and occurrence of metastases in a time period less than 2 years [8]. Various tumor factors, including large diameter and high stage group as well as nuclear grade have been determined as important risk factors for tumor recurrence. Patients with tumors greater than 5 cm in greatest diameter had a greater frequency of tumor recurrence than those with tumors smaller than 5 cm in a study (P = 0.01) [9].

Metastases from RCC share morphological and imaging features with endocrine pancreatic neoplasms and the differential diagnosis between hypervascular metastases and nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumors may be problematic [10]. The CT scan characteristics of the pancreatic metastases generally resembled those of primary RCC, with well-defined margins and greater enhancement than a normal pancreas with a central area of low attenuation. Peripherally enhanced tumors are more likely to be metastatic than primary pancreatic cancers, which tend to be non- or poorly-enhanced masses [10]. On MRI (with contrast), smaller lesions show homogeneous enhancement whereas rim enhancement is noted in larger lesions. The emergence of EUS – if feasible – has been the diagnostic modality of choice for detecting even small lesions. A fundamental principle for the indication of an EUS-FNA biopsy is the determination of whether the information obtained has the potential to affect patient management. An EUS-guided FNA biopsy is examined in patients with a solid pancreatic mass suspected to be a malignant tumor. FNA cytology though often non-specific for RCC metastases, might be performed preoperatively. However, for resectable tumors, preoperative diagnosis would not alter the treatment, and surgery without previously performed FNA biopsy is reasonable. Diagnostic approach to pancreatic cysts include EUS imaging; nevertheless, there are reports concerning a dissemination risk from EUS-FNA. The enhanced diagnostic capability of EUS-FNA must be balanced against the risk of tumor seeding. Smaller-gauge needles have similar cytology yields as large-gauge needles and additional advantage of greater flexibility for difficult approachable areas, such as the uncinate process [11]. In cases in which the initial EUS-FNA is negative for malignancy, if suspicion remains high, surgical exploration or repeat EUS-FNA is advised. Differential diagnosis should be made especially from neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas [10].

The introduction of targeted agents (tyrosine kinase and Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors) has dramatically changed the therapeutic landscape of patients with metastatic RCC, improving their outcome [12]. However, surgical resection of pancreatic metastases seems to play a crucial role in the management of these patients paving the way for a possible cure. At that regard, it is important to accurately diagnose pancreatic involvement by metastatic RCC on histology, especially given that RCC metastasis may manifest more than a decade after its initial presentation and diagnosis. Pancreatic metastases of RCC represent a relatively indolent tumor phenotype, which further supports the strategy of typical operation. Nevertheless, operations such as partial, distal and total pancreatectomy are indicated in terms of tumor traits and patients’ status. The selection of patients undergoing surgery should be rational, taking into account life expectancy, comorbidity, metastatic extent and tumor biology for the benefit to be optimal. In the largest series of cases with surgical resection of pancreatic metastases from RCC, Schwarz et al. reported 3-, 5-, and 10-year overall survival (OS) of 72, 63, and 32% respectively, highlighting the long-term beneficial impact of surgery in these patients [13]. The role of adjuvant and neoadjuvant targeted therapies remains under investigation.

5. Conclusion

More clinical research is needed to elucidate the impact of both surgery and targeted therapeutic interventions in the management of patients with pancreatic metastases from RCC. Their behavior is indolent, with long-term survival. Close and long-term follow-up is important for designing optimal treatment, and these patients should be evaluated with a multidisciplinary approach. A high index of suspicion is required for patients with a history of RCC and they should be provided lifelong multidisciplinary follow-up for early detection of metastases.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., Eser S., Mathers C., Rebelo M., Parkin D.M., Forman D., Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136:359–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faure J.P., Tuech J.J., Richer J.P., Pessaux P., Arnaud J.P., Carretier M. Pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: presentation, treatment and survival. J. Urol. 2001;165:20–22. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballarin R., Spaggiari M., Cautero N., De Ruvo N., Montalti R., Longo C., Pecchi A., Giacobazzi P., De Marco G., D'Amico G., Gerunda G.E., Di Benedetto F. Pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: the state of the art. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4747–4756. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i43.4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espinoza E., Hassani A., Vaishampayan U., Shi D., Pontes J.E., Weaver D.W. Surgical excision of duodenal/pancreatic metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2014;4:218. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zerbi A., Ortolano E., Balzano G., Borri A., Beneduce A.A., Di Carlo V. Pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: which patients benefit from surgical resection? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008;15:1161–1168. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grassi P., Verzoni E., Mariani L., De Braud F., Coppa J., Mazzaferro V., Procopio G. Prognostic role of pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: results from an Italian center. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 2013;11:484–488. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gagnier J.J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D., CARE Group The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014;67:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masetti M., Zanini N., Martuzzi F., Fabbri C., Mastrangelo L., Landolfo G., Fornelli A., Burzi M., Vezzelli E., Jovine E. Analysis of prognostic factors in metastatic tumors of the pancreas: a single-center experience and review of the literature. Pancreas. 2010;39:135–143. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bae9b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chae E.J., Kim J.K., Kim S.H., Bae S.J., Cho K.S. Renal cell carcinoma: analysis of postoperative recurrence patterns. Radiology. 2005;234:189–196. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341031733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moletta L., Milanetto A.C., Vincenzi V., Alaggio R., Pedrazzoli S., Pasquali C. Pancreatic secondary lesions from renal cell carcinoma. World J. Surg. 2014;38:3002–3006. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2672-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasan M.K., Hawes R.H. EUS-guided FNA of solid pancreas tumors. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2012;22:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2012.04.016. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Veldt A.A., Haanen J.B., van den Eertwegh A.J., Boven E. Targeted therapy for renal cell cancer: current perspectives. Discov. Med. 2010;10:394–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarz L., Sauvanet A., Regenet N., Mabrut J.Y., Gigot J.F., Housseau E., Millat B., Ouaissi M., Gayet B., Fuks D., Tuech J.J. Long-term survival after pancreatic resection for renal cell carcinoma metastasis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014;21:4007–4013. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3821-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]