Abstract

Background

Expression of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) across glioma grades is undocumented, and their interactions with commonly expressed genetic and epigenetic alterations are undefined but nonetheless highly relevant to combinatorial treatments.

Methods

Patients with CNS malignancies were profiled by Caris Life Sciences from 2009 to 2016. Immunohistochemistry findings for PD-1 on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) and PD-L1 on tumor cells were available for 347 cases. Next-generation sequencing, pyrosequencing, immunohistochemistry, fragment analysis, and fluorescence in situ hybridization were used to determine isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), and tumor protein 53 mutational status, O6-DNA methylguanine-methyltransferase promoter methylation (MGMT-Me) status, PTEN expression, plus epidermal growth factor receptor variant III and 1p/19q codeletion status.

Results

PD-1+ TIL expression and grade IV gliomas were significantly positively correlated (odds ratio [OR]: 6.363; 95% CI: 1.263, 96.236)—especially in gliosarcomas compared with glioblastoma multiforme (P = .014). PD-L1 expression was significantly correlated with tumor grade with all PD-L1+ cases (n = 21) being associated with grade IV gliomas. PD-1+ TIL expression and PD-L1 expression were significantly correlated (OR: 5.209; 95% CI: 1.555, 20.144). Mutations of PTEN, tumor protein 53, BRAF, IDH1, and epidermal growth factor receptor or MGMT-Me did not associate with increased intratumoral expression of either PD-1+ TIL or PD-L1 in glioblastoma multiforme even before false discovery rate correction for multiple comparison.

Conclusions

Targeting immune checkpoints in combination with other therapeutics based on positive biomarker selection will require screening of large patient cohorts.

Keywords: glioblastoma, immune checkpoint, low-grade glioma, PD-1, PD-L1

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) is expressed on T cells, prevents T-cell cytotoxic activation (with or without the interaction with its ligand), and is a potential target for immunotherapy. Tumors can appropriate physiological immune regulatory mechanisms such as programmed death ligand (PD-L)1 to prevent their immunological recognition and clearance. The PD-1 ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, are present on tumor, stromal, and other immune cells that interact with the PD-1 receptor, causing downregulation of the T-cell response. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have recently revolutionized the treatment of a number of advanced cancers, including melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer. This recent success has generated increasing interest in whether these agents could also be employed in the treatment of gliomas, particularly glioblastomas. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), the most common malignant primary brain tumor in adults, constitutes a universally lethal diagnosis, with a median survival time of 14–16 months and a 26%–33% two-year survival rate despite optimized multimodality treatment that typically includes surgery, irradiation, and chemotherapy.1 New therapeutic approaches are desperately needed, and attention has been increasingly shifted toward immunotherapeutic strategies as a potential promising treatment approach.2

Prior studies have shown that PD-1 and PD-L1 are expressed in glioblastoma,3–5 but it is unknown if these are expressed in other types or grades of gliomas, suggesting potential benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition. Previous reports have indicated that the expression of PD-1 on tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) and PD-L1 is more likely to correlate with a therapeutic response to immune checkpoint inhibitors,6,7 and as such their coassociation was also evaluated. Finally, this study evaluated the associations between immune checkpoint expression with key genetic and epigenetic alterations that may inform rational combinatorial treatment approaches.

Materials and Methods

All cases were from patients with CNS tumors submitted to Caris Life Sciences for genomic analysis between 2009 and 2016. The initial histological diagnosis based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 classification was confirmed. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) data for PD-1 on TIL and for PD-L1 on tumor cells were available for 235 and 345 cranial tumors, respectively. Additionally, next-generation sequencing, pyrosequencing, IHC, fragment analysis, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) were used to determine mutational status of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), tumor protein 53 (TP53), and BRAF, along with O6-DNA methylguanine-methyltransferase promoter methylation (MGMT-Me) status, PTEN expression, epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII) expression, and 1p/19q codeletion status.

IHC analysis was performed on full slides of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples using automated staining techniques. Dilutions and conditions were based on package insert instructions, were optimized and validated, and met the standards and requirements of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments/College of American Pathologists and the International Organization for Standardization. IHC results were evaluated independently by 6 board-certified pathologists. The primary antibody used against PD-L1 was SP142 (Spring Biosciences).8 The chromogenic reporter 3,3′-diaminobenzidine was used to allow for a colorimetric visualization of the antibody yielding a brown stain that can be analyzed with a light microscope. For the SP142 clone, the Rabbit LINKER visualization system (Dako) was used. The staining was regarded as positive if its intensity on the membrane of the tumor cells was >1+ (on a semiquantitative scale of 0–3: 0 for no staining, 1+ for weak staining, 2+ for moderate staining, or 3+ for strong staining) and the percentage of positively stained cells was >5% (Supplementary Fig. 1). The primary antibody used for PD-1 was MRQ-22 (Ventana) and staining was scored as positive if the number of PD-1+ TIL was >1 cell per high-power field.9 PD-1 TIL density was evaluated using a hotspot approach. The whole tumor sample was reviewed at a low power (4x objective), and the areas of highest density of TIL in direct contact with malignant cells of the tumor at 400x visual field (40x objective × 10x ocular) were enumerated. PTEN IHC analysis was performed using antibody 6H2.1, and tumor cells were scored for both cytoplasmic and nuclear staining. The threshold used to determine positivity was 1+ and 50% staining. During the validation process for each IHC, any interpathologist variability was addressed in a scope session with all the pathologists, led by the medical director. In addition, weekly training sessions were held for all pathologists to score randomly selected samples to reach the same scoring.

FISH was performed to detect codeletion of chromosomes 1p and 19q, performed with Abbott Molecular probes for 1p36/1q25 and 19p13/19q13. A sample was considered to have both 1p and 19q deletion when ratios of 1p/1q signals and 19q/19p signals were both <0.80.

Next-generation sequencing was performed on genomic DNA isolated from FFPE tumor tissue using the Illumina MiSeq platform. Specific regions of 47 genes were amplified using the customized Illumina TruSeq Amplicon Cancer Hotspot panel.10 All variants reported were detected with >99% confidence based on the mutation frequency present and the amplicon coverage. The presence of a mutation in TP53, PTEN, BRAF, and IDH1 was evaluated by next-generation sequencing and was declared positive relative to wild-type (negative) controls.

MGMT methylation testing was performed on extracted DNA by pyrosequencer-based analysis of 5 cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG) sites (CpGs 74–78) with previously established cutpoints.11,12 Results of samples with ≥7% and <9% methylation were considered to be equivocal. There were no equivocal results in our analyzed cohort.

Fragment analysis of EGFRvIII was performed on RNA extracted from FFPE tumor samples. Two sets of FAM (fluorophore 6-carboxyfluorescein)-linked primers were used for PCR amplification of both the wild-type and mutant EGFR alleles, and PCR products were visualized using an ABI 3500xl. Signals generated from the wild-type allele were used as an amplification control, and samples were considered positive if EGFRvIII was detected at a level that was 5x higher than the average background signal.

Statistical Analysis

We applied Fisher's exact test to compare the PD-1+ TIL expression and PD-L1 expression levels with other markers. The Cochran Armitage test was used to examine the trend of positive expression by grade. Because grade IV gliomas were significantly positively correlated with PD-1+ TIL expression and PD-L1 expression, the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test was employed to access whether tumor grade is a confounding factor for the correlations between PD-1+ TIL/PD-L1 and other markers. For binary biomarker expressions (PD-1/PD-L1), Bayesian logistic regression models13,14 were further employed to explore their associations with tumor grade, tumor type, and the expressions of other biomarkers (Supplementary materials). The probability of high expression was assumed to follow a logistic regression model, wherein logit(p) was a linear combination of the covariates. The prior distributions of covariate parameters were assumed to be normal with a mean of zero and an SD of 100, and the prior of the dispersion parameter was assumed to be gamma with both parameters = 0.001. This SD was chosen after conducting a preliminary sensitivity analysis with SDs ranging from 5 to 1000 (results not shown). For all posterior computations, 5 different initial values of each covariate parameter were used to generate 5 Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations of size 10 000 each after a 10 000-iteration burn-in period for convergence. To reduce sample autocorrelations, we thinned the Markov chain by retaining every fifth sample value. Results from these 5 chains were combined to make posterior inferences. Statistical software R v3.1.2 (with packages rjags v3–14 and coin v1.0–24) was used to conduct data analysis. Multiple comparison correction was conducted for the testing of correlations between PD-1/PD-L1 expressions and expression of other mutations using Benjamini and Hochberg's method.15 P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant, and between .05 and .1 was considered statistically weakly significant.

Results

Patient Characterization of PD-1/PD-L1 Analysis Cohort

Available for analysis were a total of 347 patients with CNS tumors, most of which were glioblastomas (WHO grade IV) (Fig. 1A) at 67.1% (n = 233), but WHO grades I/II and III gliomas were also represented, at 15.6% and 13.6%, respectively. There were also 13 gliosarcomas, representing 3.7% of the total cases for which PD-1/PD-L1 staining was available. There were 2 ependymomas with PD-1+ TIL staining available. The tumors were usually limited to adult patients, those at least 18 years old, although 10 cases (2.9%) occurred in pediatric patients. The average age was 51.9 years (range: 5–89 y). Males constituted 61.4% of cases. Table 1 summarizes the composition of the patient cohort and the biomarker characteristics based on pathology. We conducted a comprehensive search of the proper Bayesian models by (i) including/excluding demographic factors such as age and sex; (ii) modifying the structure of random effects between tumor type and tumor grade; and (iii) testing tumor grade as a continuous factor or dichotomized variable, whichever one best correlated with the expression. We found that age and sex weren′t confounding factors associated with expression.

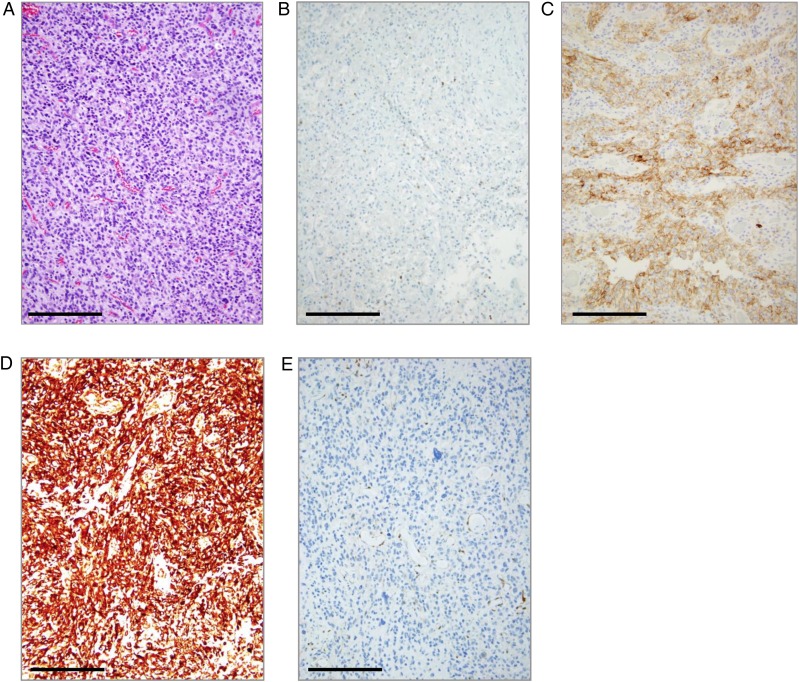

Fig. 1.

Representative IHC staining of PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 in glioblastoma. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of a glioblastoma (WHO grade IV), showing typical hypercellularity and multiple areas of vascular proliferation. Magnification is at 20x. (B) Image of PD-1-positive staining (2–5 per high-power fields) on TIL in a glioblastoma (using antibody MRQ-22). High-power field = 40x. (C) Image of PD-L1–positive staining (2+, 10%) on tumor cells of a glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) (using antibody SP142). (D) Image of PTEN-positive staining (3+) and over 50% expression on tumor cells. (E) Image of a PTEN-negative staining in a glioblastoma. Bar = 100 μm.

Table 1.

Pathological composition and characteristics of the analyzed PD-1/PD-L1 patient cohort

| All Patients | LGA | O | MOA | E | AO | AMOA | AA | GS | GBM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathology | ||||||||||

| WHO grade | I + II + III + IV | I + II | II | II | II + III | III | III | III | IV | IV |

| Number of patients (%) | 347 | 26 (7.5) | 19 (5.5) | 8 (2.3) | 2 (0.6) | 9 (2.6) | 4 (1.2) | 33 (9.5) | 13 (3.7) | 233 (67.1) |

| Parameters | ||||||||||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Male | 213 (61.4) | 7 (26.9) | 13 (68.4) | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (50.0) | 19 (57.6) | 7 (53.8) | 158 (67.8) |

| Female | 134 (38.6) | 19 (73.1) | 6 (31.6) | 5 (62.5) | 2 (100) | 5 (55.6) | 2 (50.0) | 14 (42.4) | 6 (46.2) | 75 (32.2) |

| Age, mean y (range) | 51.9 (5–89) | 39 (8–81) | 45.5 (22–78) | 45.1 (28–74) | 14 (10–18) | 48.6 (24–63) | 61 (55–69) | 42.4 (11–72) | 55.0 (35–68) | 55.6 (5–89) |

| PD-1/PD-L1 expression | ||||||||||

| PD-1 on TIL, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Positive | 74/235 (31.5) | 2/12 (16.7) | 0/12 (0.0) | 2/6 (33.3) | 0/1 (0.0) | 1/7 (14.3) | 0/2 (0.0) | 5/23 (21.7) | 7/9 (77.8) | 57/163 (35.0) |

| PD-L1 on tumor cells, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Positive | 21/345 (6.1) | 0/26 (0.0) | 0/19 (0.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | 0/2 (0.0) | 0/9 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 0/33 (0.0) | 3/12 (25.0) | 18/232 (7.8) |

| Biomarker characteristics | ||||||||||

| IDH1, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Mutated | 76/337 (22.6) | 12/24 (50.0) | 15/18 (83.3) | 5/7 (71.4) | 0/2 (0.0) | 8/9 (88.9) | 1/4 (25.0) | 17/31 (54.8) | 1/13 (7.7) | 17/229 (7.4) |

| TP53, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Mutated | 118/335 (35.2) | 12/24 (50.0) | 3/18 (16.7) | 5/7 (71.4) | 0/2 (0.0) | 2/9 (22.2) | 0/4 (0.0) | 19/31 (61.3) | 4/12 (33.3) | 73/228 (32.0) |

| BRAF, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Mutated | 10/337 (3.0) | 2/24 (8.3) | 0/18 (0.0) | 0/7 (0.0) | 0/2 (0.0) | 0/9 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 0/31 (0.0) | 1/13 (7.7) | 7/229 (3.1) |

| SEQ-PTEN, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Mutated | 81/329 (24.6) | 3/24 (12.5) | 0/18 (0.0) | 1/6 (16.7) | 0/2 (0.0) | 0/9 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 4/30 (13.3) | 7/12 (58.3) | 66/224 (29.5) |

| PTEN IHC, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Positive | 314/328 (95.7) | 23/24 (95.8) | 16/17 (94.1) | 7/7 (100.0) | 2/2 (100.0) | 8/8 (100.0) | 4/4 (100.0) | 25/27 (92.6) | 10/12 (83.3) | 219/227 (96.5) |

| EGFRvIII, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Positive | 39/263 (14.8) | 1/17 (5.9) | 0/15 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/7 (0.0) | 0/3 (0.0) | 1/27 (3.7) | 1/10 (10.0) | 36/179 (20.1) |

| MGMT promoter, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Methylated | 165/326 (50.6) | 11/23 (47.8) | 16/19 (84.2) | 3/5 (60.0) | 0/2 (0.0) | 9/9 (100.0) | 1/4 (25.0) | 22/29 (75.9) | 3/13 (23.1) | 100/222 (45.0) |

| 1p19q codeletion, n/total n (%) | ||||||||||

| Present | 35/327 (10.7) | 0/25 (0.0) | 14/19 (73.7) | 0/7 (0.0) | 0/2 (0.0) | 7/9 (77.8) | 1/4 (25.0) | 1/28 (3.6) | 0/13 (0.0) | 12/220 (5.5) |

Abbreviations: LGA, low-grade astrocytoma; O, oligodendroglioma; MOA, mixed oligoastrocytoma, E, ependymoma; AO, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; AMOA, anaplastic mixed oligoastrocytoma; AA, anaplastic astrocytoma; GS, gliosarcoma.

PD-1/PD-L1 Expression Correlates with the Grade of Glioma

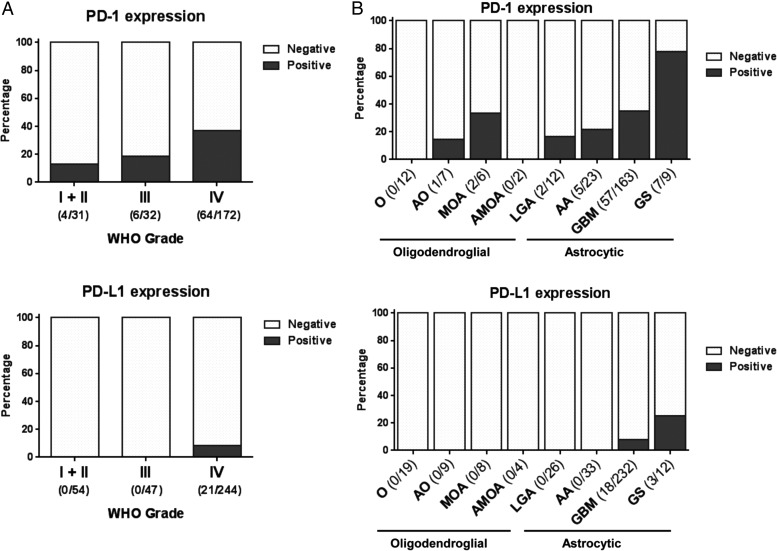

In our PD-1/PD-L1 analysis cohort, PD-1 was expressed on TIL in 31.5% (74/235) of cranial gliomas, and PD-L1 expression on tumor cells was found in 6.1% (21/345) of glioma cases (Fig. 1B and C; Table 1). PD-1/PD-L1 staining was available for 26 low-grade astrocytomas (WHO grades I and II). Of these, 16.7% (2/12) were positive for PD-1+ TIL, while none were positive for PD-L1 (n = 26). Of grade II oligodendrogliomas (n = 19), none were positive for PD-1+ TIL or PD-L1. There were 8 grade II mixed oligoastrocytomas, of which 2/6 (33.3%) were positive for PD-1+ TIL. None of the mixed oligoastrocytomas were positive for PD-L1. Within the category of grade III anaplastic astrocytomas, 21.7% (5/23) were positive for PD-1+ TIL but none were positive for PD-L1. Of grade III anaplastic oligodendrogliomas (n = 9), only one had PD-1 TIL staining. Within a limited sampling of grade III anaplastic mixed oligoastrocytomas, none had PD-1 or PD-L1 positive staining. Of the 233 GBM tumors, 35.0% (57/163) were positive for PD-1+ TIL, and 7.8% (18/232) were positive for PD-L1. Moreover, expression was enriched in the gliosarcomas with 77.8% (7/9) positive for PD-1+ TIL, and 25.0% (3/12) positive for PD-L1. Among grade IV tumors, PD-1+ TIL were more likely to be expressed in gliosarcoma than GBM (P = .014), and the same was true for PD-L1 (P = .073). Both PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 expressions were significantly correlated with grade IV gliomas (odds ratio [OR]: 6.363; 95% CI: 1.263, 96.236 for PD-1+ TIL after controlling tumor type, and OR undefined for PD-L1, given that all 21 positive PD-L1 were grade IV gliomas) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 expression based on WHO tumor grade and pathology. (A) The expressions of PD-1 increases with tumor grade and is significantly associated with grade IV gliomas; PD-L1 is only associated with grade IV gliomas. (B) PD-1+ TIL expression was more commonly associated with astrocytic tumors than with oligodendroglioma. O, oligodendroglioma; AO, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; MOA, mixed oligoastrocytoma; AMOA, anaplastic mixed oligoastrocytoma; LGA, low-grade astrocytoma; AA, anaplastic astrocytoma; GS, gliosarcoma. Number of positive and total cases are shown.

PD-1/PD-L1 Expression Associates with Tumors of Astrocytic Lineage

In general, PD-L1 expression does not occur within gliomas of oligodendroglial lineage (Fig. 2B). However, there is an occasional influx of PD-1+ TIL within mixed oligoastrocytoma (2/6, 33.3%) and anaplastic oligodendrogliomas (1/7; 14.3%). In marked contrast, PD-1+ TIL is present in all grades of astrocytic tumors with a trend to an association with grade (P = .054, Fig. 2B). PD-L1 expression was confined to grade IV astrocytic tumors.

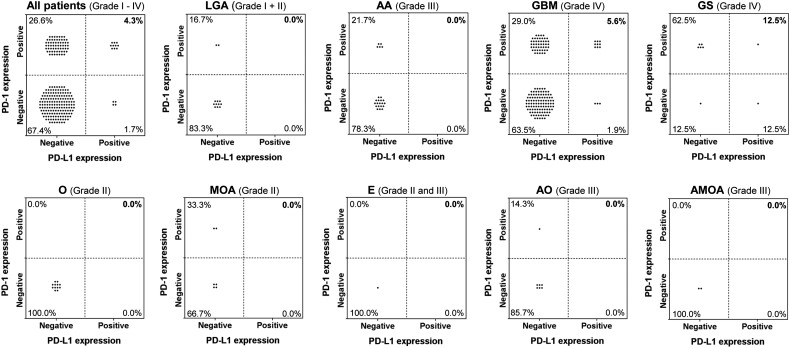

PD-1 Expression Correlates with PD-L1 Expression

Because prior reports had indicated that dual expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 may correlate with therapeutic responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors, we conducted further sub-analysis to evaluate the incidence of dual-positive glioma cases. We found positive staining for both PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 in 4.3% (n = 10) of glioma cases (Fig. 3). The highest percentage of dual-positive staining was found in the gliosarcomas at 12.5% (1/8). This was followed by grade IV glioblastomas at 5.6% (n = 9). PD-1+ TIL expression showed a very significant positive correlation with PD-L1 expression after controlling the tumor type (OR: 5.209; 95% CI: 1.555, 20.144), or within the glioblastoma cohort only (OR: 6.492; 95% CI: 1.531, 38.986). Of the 10 pediatric cases available for analysis, 6 (60.0%) carried a diagnosis of GBM. One of these 6 patients (16.7%) was PD-1 positive, and none of these were PD-L1 positive.

Fig. 3.

Simultaneous PD-1/PD-L1 expression relative to WHO tumor grade and pathology. PD-L1 expression was analyzed relative to that of PD-1+ TIL. Positive staining for both PD-1 on TIL and PD-L1 was found in 4.3% of all cranial tumors studied. PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 were coexpressed in grade IV gliomas. LGA, low-grade astrocytoma; AA, anaplastic astrocytoma; GS, gliosarcoma; O, oligodendroglioma; MOA, mixed oligoastrocytoma; E, ependymoma; AO, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; AMOA, anaplastic mixed oligoastrocytoma.

Molecular Associations in GBM with the PD-1/PD-L1 Signaling Axis

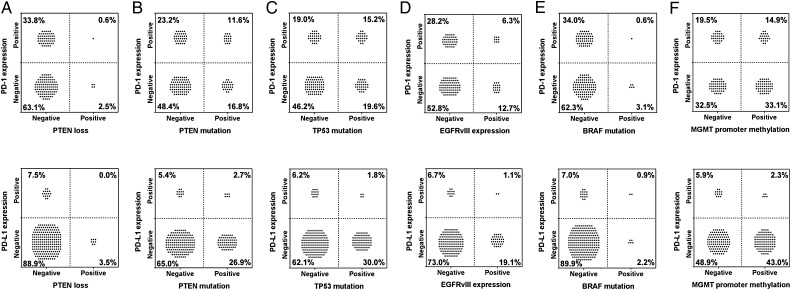

Within the glioblastoma dataset and based on IHC studies (Fig. 1D and E), the incidence of PTEN expression was 96.5% (219/227), which is higher than the previously reported incidence of 70%.16 An association between PTEN loss and the activation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase, increasing the expression of B7-H1 (PD-L1), has been noted by others.17 However, we could not confirm this association, with 0% or 0.6% of GBM cases demonstrating the absence of PTEN with associated expression of PD-L1 or PD-1+ TIL (Fig. 4A). Because the IHC analysis does not take into account the confounding factor of PTEN expression in the tumor stroma,18 we also evaluated the association of PD-L1 expression with the PTEN mutation, which may or may not lead to protein loss, and found that PTEN mutational status does not correlate with either PD-L1 expression (P = 1) or PD-1+ TIL expression (P = 1) (Fig. 4B) after false discovery rate correction.

Fig. 4.

Association of PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 with molecular determinants in glioblastomas. (A) PTEN, PD-1+ TIL, and PD-L1 were assessed using IHC analysis. (B) PTEN mutational status was determined by next-generation sequencing (NGS). (C) TP53 mutation status was determined by NGS. (D) EGFRvIII was detected using fragment analysis, using as the cutpoint the presence of a signal that was 5-fold higher than was seen in the background. (E) BRAF mutations as determined by NGS. (F) MGMT methylation status was defined according to pyrosequencer-based analysis of 5 CpG sites. None of those mutations showed a significant correlation with either PD-1+ TIL or PD-L1 expression (P-values ranged from .79 to 1 after correction for multiple testing).

In our dataset, 32.0% (73/228) of GBM tumors carried the TP53 mutation, which is consistent with the known frequency of aberrant protein expression.19 Of the GBM tumors, 15.2% (24/158) were positive for PD-1+ TIL and TP53 mutation, and 1.8% (4/227) were positive for PD-L1 and TP53 mutation (Fig. 4C), indicating that this mutation does not frequently coassociate with immune checkpoint expression (P = .79 for correlation with PD-1+ TIL and P = 1 for PD-L1, respectively). Further analysis of 26 low-grade astrocytomas that had PD-1/PD-L1 staining available demonstrated that 12/24 (50.0%) carried the TP53 mutation. Of these tumors, 1/4 (25.0%) were positive for PD-1+ TIL, and none (0/12) were positive for PD-L1 (data not shown).

Of the patients who had both PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 expression, coexpression with EGFRvIII was an uncommon event (Fig. 4D). No patients had PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint coexpression with EGFRvIII expression. This finding may have been partially influenced by the slightly lower frequency of EGFRvIII expression of 20.1% (36/179) in our dataset relative to the reported 30% incidence.20,21 The BRAF mutation is present in only a small proportion of high-grade gliomas,22 and we found this mutation in only 3.1% of GBM. Of these 7 tumors, only 1 was positive for both PD-1 and PD-L1 (Fig. 4E).

In our study, 100/222 GBM tumors (45%) were positive for MGMT-Me, which is similar to the reported frequency of 48.5%.20 Of the patients who had GBM tumors, 14.9% were copositive for PD-1+ TIL and MGMT-Me, 2.3% were copositive for PD-L1 and MGMT-Me (Fig. 4F), and 1.3% were copositive for PD-1/PD-L1 and MGMT-Me. There was no significant association between MGMT-Me expression and expression of PD-1+ TIL (P = 1) or PD-L1 (P = 1).

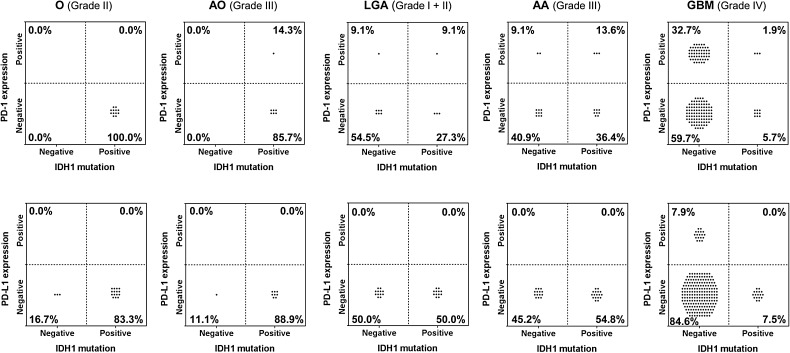

Molecular Associations of IDH1 Mutation in Gliomas with the PD-1/PD-L1 Signaling Axis

There were 28 oligodendrogliomas (grade II, n = 19 and grade III, n = 9) with PD-1/PD-L1 data available. Rarely, 14.3% of the anaplastic oligodendrogliomas (grade III) would demonstrate the presence of the IDH1 mutation, with infiltrating PD-1+ lymphocytes (Fig. 5). In none of the oligodendrogliomas was there PD-L1 expression that could be correlated with IDH1 mutation. Among the grade I and II astrocytomas, 9.1% were copositive for PD-1+ TIL and the IDH1 mutation. Fifty-five percent of the anaplastic astrocytomas were positive for IDH1 mutation. Among these, 13.6% were copositive for PD-1+ TIL and the IDH1 mutation but none was copositive for PD-L1 and the IDH1 mutation. The IDH1 mutation frequency was previously reported to occur in approximately 12% of GBM tumors,23 and in our study the incidence was 7.4.%. Among the glioblastomas, 1.9% were copositive for PD-1+ TIL and the IDH1 mutation, and none was copositive for PD-L1 and the IDH1 mutation. As such, there does not appear to be a coassociation of the IDH1 mutation and the expression of PD-1+ TIL or PD-L1.

Fig. 5.

Lack of association of PD-1 and PD-L1 with IDH1 mutational status in gliomas. The presence of IDH1 mutations was determined by next-generation sequencing, and expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 was assessed by IHC analysis. Gliomas were categorized according to WHO criteria. Regardless of glioma grade or pathology, IDH1 mutations were not commonly associated with either PD-1+ TIL or with glioma PD-L1 expression (P-values are all equal to 1 after correction for multiple testing). O, oligodendroglioma; AO, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; LGA, low-grade astrocytoma; AA, anaplastic astrocytoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme.

Presence of Mutations Studied and Expression of the PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 Signaling Axis

To ascertain whether the presence of any of the analyzed mutations influences the expression of immune checkpoints, we evaluated the GBM cohort in which 59.2% (138/233) had at least one mutation in PTEN, TP53, IDH1, BRAF, or EGFR. Overall, 23.3% of patients expressed PD-1+ TIL and a mutation (38.4% of the mutation-positive population) and 4.7% expressed PD-L1 and a mutation (8.0% of the mutation-positive population) (Supplementary Fig. 2A). The incidence of any mutation together with both PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 expression in GBM was 3.1%, providing further support that mutational status may not necessarily coassociate and enrich immune checkpoint expression. A recent study demonstrated a positive correlation between mutation frequency and age.24 In our GBM cohort, the average age of patients who did not have a mutation in these 5 genes was 58.8 years old, and the average age of patients carrying a mutation was 53.5 years old. The presence of a mutation was found to be associated with younger patients (P = .008) (Supplementary Fig. 2B). This significant difference was observed even if 6 pediatric patients were excluded. Additional analysis categorized based on the increased number of mutated genes relative to age demonstrated an inverse relationship (1 gene, n = 82, 54.6 y; 2 genes, n = 51, 51.9 y; 3 genes, n = 5; 50.4 y) (Supplementary Fig. 2C).

Discussion

In this analysis, we found that PD-L1 expression appears to be confined to grade IV gliomas and correlates with PD-1+ TIL expression. Conversely, PD-1+ TIL expression did not necessarily correlate with PD-L1 expression. A discrepancy between the presence of PD-1+ TIL and PD-L1 expression was most evident in oligodendrogliomas, which may be secondary to differences in T-cell infiltration among these tumors25 or was perhaps due to other members of the immune checkpoint family being preferentially expressed in oligodendrogliomas. But perhaps the most striking finding was the lack of correlation of various mutations with immune checkpoint expression. In a disease where recurrence is inevitable and resistance develops quickly, combination therapy is likely to be superior to monotherapy. Although there is great enthusiasm for combinatorial strategies, our analysis indicates that many of these approaches will be applicable to only a highly select subset of patients. For example, IDH1 has emerged as a therapeutic target postulated to be a driver of tumorigenesis. IDH1 inhibitors are currently under investigation in solid tumors, including gliomas (NCT 02073994, NCT 02381886). Additionally, IDH1 mutations are immunogenic, and peptide vaccine strategies are under preclinical development.26 As such, a proposed rational combination could be a PD-1 inhibitor plus an IDH1 inhibitor/peptide vaccine for secondary GBM. However, if enrollment is based on the presence of the targeted biomarker, <2% of GBM patients would potentially benefit. As another example, since p53 gene mutations are known to be involved in the progression of low-grade gliomas to higher-grade tumors such as GBM,27 copositivity (of PD-1+ TIL expression and p53 mutation) in select cases could dictate a viable combinatorial strategy of using a PD-1 inhibitor in combination with an agent targeting p53 such as SGT-53, which is a p53 nanoparticle (NCT 02340156). In this case, 15% of GBM patients may potentially benefit. Cumulatively, if therapeutic response is solely predicated on the presence of positive biomarker expression, our data would suggest that only rare patients may benefit. Our findings were focused on specific genetic alterations that occur with PD-1+ TIL and/or PD-L1 at reasonably high frequency given the heterogeneity of GBM to provide insight into some potential rational combinatorial therapies paired with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Notably, these data reveal that for combinatorial clinical trial strategies, in which likely responders are identified by biomarkers, comprehensive profiling will be required of large patient cohorts.

Silencing of the MGMT gene, which is a DNA repair protein that can reverse the effects induced by alkylating agents, has shown a survival benefit in patients treated with radiotherapy and temozolomide (TMZ) compared with patients who express unmethylated MGMT.11 PD-1+ TIL expression was associated with unmethylated MGMT. This represents a therapeutic opportunity but also a confounding factor when assessing outcomes in nonrandomized trials. MGMT-methylated GBM has been shown to more favorably respond to TMZ. We have previously shown that TMZ can potentiate antitumor immune responses.28 Newly diagnosed GBM, like most cancers, expresses neoantigens,29 but the antigen load can increase significantly after TMZ treatment, given its mutagenic properties,10,30,31 resulting in increased tumor heterogeneity over time after treatment. From this perspective, even patients with unmethylated MGMT may benefit in the context of pretreatment with TMZ followed by an immune checkpoint approach.

In contrast to a prior report,17 we did not find a correlation between PD-L1 expression and PTEN. In the former study, only a limited number (n = 6) of ex vivo GBM specimens were analyzed, using quantitative western blots (n = 3), demonstrating overlap of B7-H1 expression between PTEN wild-type and null tumors. Nevertheless, this correlation has been found in other cancers, such as lung,32 and may be contextual within various types of malignancies and in association with other genes.

Mutational load has previously been shown to correlate with clinical responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors,33–36 and glioma patients who bear this unique expression profile may be a distinctive subset for long-term responders who have received immune checkpoint inhibitors. We did not find positive correlations between various glioblastoma mutations and the expression of immune checkpoints. Because TP53 is a tumor suppressor gene that helps to aid the repair process in DNA synthesis, one could hypothesize that gliomas that express TP53 might have a lower mutational load than tumors without this gene, which has been shown in mammalian cells.37 However, this observation was also found for other mutations, such as PTEN, EGFR, BRAF, and IDH1. Unfortunately, our dataset did not include mutational load, and this is an interesting area of future investigation, including whether it is predictive of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

It is actively being debated whether PD-1/PD-L1 expression is an appropriate biomarker for treatment response to immune checkpoint inhibition, since clinical responses can occur in patients who do not express these biomarkers. Furthermore, the location of expression of PD-L1 may be a confounding variable in this analysis, since it is unclear whether clinical response is associated with PD-L1 expression on the T cells, macrophages, or tumor cells – either on the membrane or in the cytoplasm. Moreover, tissue testing of PD-L1 expression is still challenging with a variety of antibodies (eg, 5H1, 22C3, 28–8, SP142, SP263) being used with different sensitivities and specificities. Cutpoints for positivity are highly variable as well as the interpretation of staining intensities. As such, there is an urgent need for harmonization of staining procedures and testing in the field. Finally, to date, there are no data on whether glioma patients with either PD-1+ TIL or PD-L1 expression in their tumor tissue will show any response to immune checkpoint antibodies. Thus, it is uncertain whether a negative association of PD-1/PD-L1 expression with distinct genetic alterations such as an EGFRvIII mutation excludes a response to checkpoint inhibition or combinatorial therapeutic strategies.

In conclusion, if predicated on the expression of tumor PD-1 and PD-L1, our data would indicate that only a minority subset of GBM patients are likely to benefit from immune checkpoint monotherapy. These results also provide insight into potential rational combination therapies as well as combinations to avoid, based on the association of PD-1/PD-L1 with other key genetic alterations.

Supplementary material

Funding

This research was funded by the Dr. Marnie Rose Foundation and the National Institutes of Health CA 1208113, P50 CA127001, and P30 CA016672.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Audria Patrick and David M. Wildrick, PhD, for their administrative and editorial support.

Conflict of interest statement. A.B.H. serves on the Caris Life Sciences Scientific Advisory Board and is a stockholder in the company. J.X., S.K.R., and D.S. are employees of Caris Life Sciences.

References

- 1. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352 (10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Preusser M, de Ribaupierre S, Wohrer A et al. Current concepts and management of glioblastoma. Ann Neurol. 2011;70 (1):9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berghoff AS, Kiesel B, Widhalm G et al. Programmed death ligand 1 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17 (8):1064–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nduom EK, Wei J, Yaghi NK et al. PD-L1 expression and prognostic impact in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18 (2):195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Preusser M, Berghoff AS, Wick W et al. Clinical neuropathology mini-review 6-2015: PD-L1: emerging biomarker in glioblastoma? Clin Neuropathol. 2015;34 (6):313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366 (26):2443–2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515 (7528):568–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;387 10031:1909–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gatalica Z, Snyder C, Maney T et al. Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) in common cancers and their correlation with molecular cancer type. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23 (12):2965–2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yip S, Miao J, Cahill DP et al. MSH6 mutations arise in glioblastomas during temozolomide therapy and mediate temozolomide resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15 (14):4622–4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352 (10):997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Quillien V, Lavenu A, Karayan-Tapon L et al. Comparative assessment of 5 methods (methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction, MethyLight, pyrosequencing, methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting, and immunohistochemistry) to analyze O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltranferase in a series of 100 glioblastoma patients. Cancer. 2012;118 (17):4201–4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gelman A, Carlin J, Stern HS et al. Bayesian Data Analysis, 2nd ed. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc. 1995;57 (1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13 (5):283–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parsa AT, Waldron JS, Panner A et al. Loss of tumor suppressor PTEN function increases B7-H1 expression and immunoresistance in glioma. Nat Med. 2007;13 (1):84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martins FC, Santiago I, Trinh A et al. Combined image and genomic analysis of high-grade serous ovarian cancer reveals PTEN loss as a common driver event and prognostic classifier. Genome Biol. 2014;15 (12):526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ogura R, Tsukamoto Y, Natsumeda M et al. Immunohistochemical profiles of IDH1, MGMT and P53: practical significance for prognostication of patients with diffuse gliomas. Neuropathology. 2015;35 (4):324–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155 (2):462–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heimberger AB, Hlatky R, Suki D et al. Prognostic effect of epidermal growth factor receptor and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma multiforme patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11 (4):1462–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dasgupta T, Olow AK, Yang X et al. Survival advantage combining a BRAF inhibitor and radiation in BRAF V600E-mutant glioma. J Neurooncol. 2016;126 3:385–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360 (8):765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim H, Zheng S, Amini SS et al. Whole-genome and multisector exome sequencing of primary and post-treatment glioblastoma reveals patterns of tumor evolution. Genome Res. 2015;25 (3):316–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heimberger AB, Abou-Ghazal M, Reina-Ortiz C et al. Incidence and prognostic impact of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in human gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14 (16):5166–5172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schumacher T, Bunse L, Pusch S et al. A vaccine targeting mutant IDH1 induces antitumour immunity. Nature. 2014;512 (7514):324–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. England B, Huang T, Karsy M. Current understanding of the role and targeting of tumor suppressor p53 in glioblastoma multiforme. Tumour Biol. 2013;34 (4):2063–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sampson JH, Aldape KD, Archer GE et al. Greater chemotherapy-induced lymphopenia enhances tumor-specific immune responses that eliminate EGFRvIII-expressing tumor cells in patients with glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13 (3):324–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500 (7463):415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gupte M, Tuck AN, Sharma VP et al. Major differences between tumor and normal human cell fates after exposure to chemotherapeutic monofunctional alkylator. PLoS One. 2013;8 (9):e74071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson BE, Mazor T, Hong C et al. Mutational analysis reveals the origin and therapy-driven evolution of recurrent glioma. Science. 2014;343 (6167):189–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xu C, Fillmore CM, Koyama S et al. Loss of Lkb1 and Pten leads to lung squamous cell carcinoma with elevated PD-L1 expression. Cancer Cell. 2014;25 (5):590–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gubin MM, Zhang X, Schuster H et al. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature. 2014;515 (7528):577–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348 (6230):124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371 (23):2189–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515 (7528):563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Avkin S, Sevilya Z, Toube L et al. p53 and p21 regulate error-prone DNA repair to yield a lower mutation load. Mol Cell. 2006;22 (3):407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.