Abstract

PURPOSE

To evaluate acceptability and feasibility of a theoretically-based two-part (brief in-person + eight-week automated text-message) depression prevention program, “iDOVE”, for high-risk adolescents.

METHODS

English speaking emergency department (ED) patients (age 13–17, any chief complaint) were sequentially approached for consent on a convenience sample of shifts, and screened for inclusion based on current depressive symptoms & past year violence. After consent, baseline assessments were obtained; all participants were enrolled in the two-part intervention (brief in-ED + 8-week two-way text-messaging). At 8 weeks, quantitative and qualitative follow-up assessments were obtained. Measures included feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary data on efficacy. Qualitative data was transcribed verbatim, double-coded and interpreted using thematic analysis. Quantitative results were analyzed descriptively and with paired t-tests.

RESULTS

As planned, 16 participants (8 each gender) were recruited (75% of those who were eligible; 66% non-white, 63% low-income, mean age 15.4). The intervention had high feasibility and acceptability: 93.8% completed 8-week follow-up; 80% of daily text-messages received responses; 31% of participants requested ≥1 “on demand” text-message. In-person and text-message portions were rated as good/excellent by 87%. Qualitatively, participants articulated: (1) iDOVE was welcome and helpful, if unexpected in the ED; (2) the daily text-message mood assessment was “most important”; (3) content was “uplifting”; (4) balancing intervention “relatability” and automation was challenging. Participants’ mean ΔBDI-2 from baseline to eight-week follow-up was −4.9 (p=0.02).

CONCLUSIONS

This automated preventive text-message intervention is acceptable and feasible. Qualitative data emphasize the importance of creating positive, relevant, and interactive digital health tools for adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescents, Health Promotion, Text Messaging, Behavior Change, Depression, Mixed Methods

Introduction

Psychiatric disorders are the fastest growing reason for adolescent emergency department (ED) visits.(1) Adolescent ED patients with non-psychiatric chief complaints are likely to report psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety, as well as related risk factors such as violence exposure.(2–4) Indeed, depression and peer violence have a bidirectional relationship in adolescents, with reinforcing negative effects on emotional and behavioral regulation.(5) Multi-session cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for co-occurring depression and violence may effectively reduce adolescents’ depressive symptoms (6). However, at-risk adolescents have difficulty accessing mental health services (3, 7), compelling them to rely on EDs for care. EDs are therefore increasingly encouraged to perform mental health screening and referrals.(8)

Adolescents articulate interest in text-message based mental health interventions.(9, 10) Publicly available text-message services are frequently used by adolescents during mental health crises, although to our knowledge no scholarly literature describes its use or effectiveness.(11) Text-messaging is an acceptable, reliable, and valid intervention method for adolescents on numerous topics.(12) Text-message preventive interventions are feasible among adult ED patients.(13) Advantages of a text-message mental health intervention may include obviation of barriers to accessing mental health interventions, such as transportation and stigma.(8) Automated programs also inherently offer high fidelity. Limitations to text-message interventions, such as patient concerns about confidentiality(14), may also exist.

In this manuscript, we describe a pilot study of iDOVE, “intervention for DepressiOn and Violence prevention in the ED.” iDOVE is an ED-based, brief in-person and longitudinal text-message depression preventive intervention for high-risk teens seen in the ED for any reason. To our knowledge, no acceptable, feasible, and efficacious technology-based mental health interventions exist for high-risk adolescents. This pilot study’s objective was to use mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative) to assess acceptability and feasibility, and to inform intervention refinement and future mobile interventions. Secondary outcomes are preliminary efficacy at eight weeks post-enrollment.

Methods

Study Setting and Recruitment

From June-October 2014, we recruited 16 adolescents (age 13–17; eight of each gender) from a large urban pediatric emergency department located in the northeast United States. All adolescents presenting to the ED during a convenience sample of shifts were prescreened for eligibility. Adolescents were excluded a priori if they did not speak English; had a chief complaint of suicidality, psychosis, sexual assault, or child abuse; were in police or child protective services’ custody; were unable to assent due to severity of illness or developmental disabilities; or if no parent was present. All other adolescents were approached for verbal consent/assent for a brief screen on a tablet computer, determining eligibility for the larger study. Adolescents were eligible for the study if they were at high-risk for depression, defined as mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9] score 5–19)(15), and a past-year history of physical peer violence (modified Conflict Tactics Scale 2nd ed. [CTS-2] score ≥ 1).(16, 17) Additionally, adolescents had to have a text-message-capable phone.

Eligible participants assented, and parents provided written consent, for the intervention and longitudinal follow-up. Enrolled participants completed a baseline survey in the ED, and a follow-up survey and semi-structured interview eight weeks post-enrollment.

Participants were incentivized using a small gift (e.g., gum) for the screening survey, $25 for the baseline survey, $10 per month for text-messaging costs, and $40 for the eight-week follow-up survey and interview. This reimbursement is on par with that used in other ED-based studies of adolescents.(17, 18)

All study materials and recruitment procedures were approved by the hospital Institutional Review Board.

Intervention Structure and Content

The intervention had two parts: a brief, in-person in-ED session; and an eight-week automated text-messaging intervention. Both components were developed and refined from motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), existing in-person and text-message preventive interventions,(6, 12, 17, 19) and participant feedback during a formative development phase.(9, 10, 14)

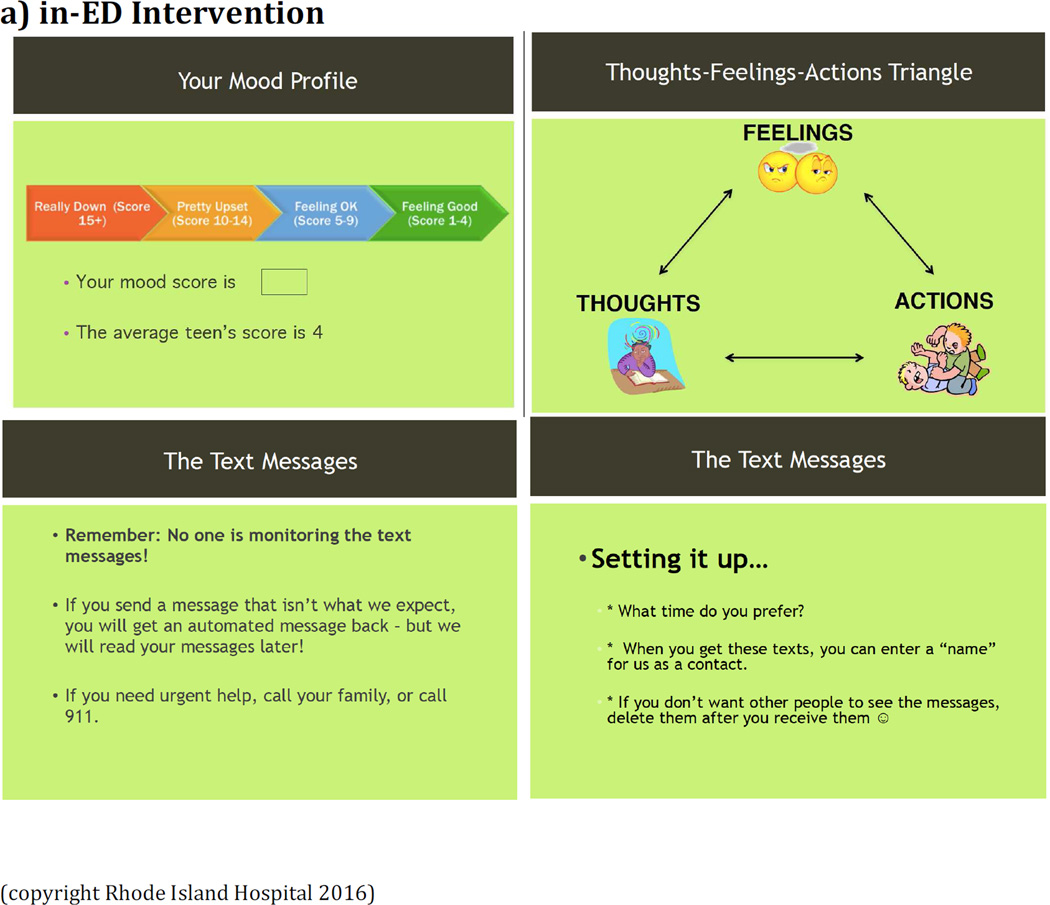

The in-ED session was a 15–20 minute scripted, PowerPoint-guided session delivered by a trained research assistant (RA) (Table 1, Figure 1)(10) covering: 1) basic CBT concepts (e.g., connecting thoughts, behavior, and mood), 2) motivational enhancement for intervention engagement (e.g., personalized feedback about mood and frequency of fights), and 3) introduction to the text-message component. The RA underwent structured training in intervention theory and methods prior to recruitment. In-ED interventions were audio-recorded. Fidelity of intervention delivery was assessed by MLR, based on intervention audio-recordings, using a 56-point adherence scale based on the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale and Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code(20).

TABLE 1.

Theory-Based Components of iDOVE Intervention

| Theory /Model |

Technique/ Strategy |

Intervention Component | Delivery Method |

Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CBT, MI |

Elicit recognition of problem(s) |

Depressive symptoms and peer violence feedback |

In-ED + Text |

(See Figure 1) |

| Beck's cognitive triangle for negative thoughts & violence identification |

REMEMBER: 1+2=3 --> Your feelings are a result of what you THINK and what you DO. You may be able to think or act your way to a better day tmrw :) (See also Figure 1) |

|||

|

CBT, MI |

Goal-setting and Motivation |

Elicit personal change goals for mood and violence |

In-ED + Text |

(See Figure 1) |

| Commitment to and comprehension of the text- message portion of the program |

Many teens said their favorite part of iDOVE was remembering to "think positive." Reward yourself for all your hard work so far. Remember that if you need extra support, you can text iDOVE at any time: ANGRY SAD, or STRESSED (See also Figure 1) |

|||

| Separate personal goals from peer standards |

You're doing awesome. Don’t let friends or anyone else pull you down a bad path. Be in control. |

|||

| Convey respect and empathy for goals |

Today is a good day to think ahead to the future. Plan a small step to get yourself there -> and tell a friend! (See also Figure 1) |

|||

| Define personal "rewards" for meeting goals |

Remember to reward yourself for your hard work so far: Think of something fun (going to a movie, getting coffee with friends…) and plan to do it! |

|||

| Increase self-efficacy for achieving these goals |

The obstacles you overcame in the past made you a stronger person. You can deal with whatever life sends your way in the future. |

|||

| CBT | Cognitive restructuring |

Identify triggers, negative thoughts, and results |

In-ED + Text |

Try to name how you're feeling right now. (Sad, angry, stressed, pissed off, worried…) Now think of an action to change that. (See also Figure 1) |

| Identify alternatives to negative thoughts |

Just because you feel bad about yourself doesn’t mean it’s true. (Example: failing a test doesn't mean someone's stupid. Maybe they just need help studying.) (See also Figure 1) |

|||

| Encourage non-violent assertiveness |

Hold on, think first! Don't do anything you would regret just because you're feeling upset |

|||

| Put negative events in perspective |

Will this matter in one week? One year? Ten years? Keep it in perspective. |

|||

| CBT | Distress tolerance |

Identify alternative ways of dealing with common stressors and potential fights ("coping plans") |

In-ED + Text |

When you're stressed in the future, sometimes walking away or going outside for a little bit can help. (See also Figure 1) |

| Provide strategies to calm down and deal with stress |

You don't need to keep feelings "bottled up." Let them out in a way that won't hurt you or others: go for a run, sing loudly, draw, write… (What else?) |

|||

| CBT | Behavioral activation |

Develop a list of fun, non- violent activities (social, physical, and indulgent) |

In-ED + Text |

Remember your list from the ER of things you can do to feel good. Do one of those today! (See also Figure 1) |

| Elicit pro-social behavioral skills |

Think of which friends/family bring out the best in you. Surround yourself with people who give you good advice. |

|||

| Reminders of community mental health/violence- prevention resources |

If you ever have a REALLY bad day, some places you could call are: [local mental health organizations and crisis numbers] (See also Figure 1) |

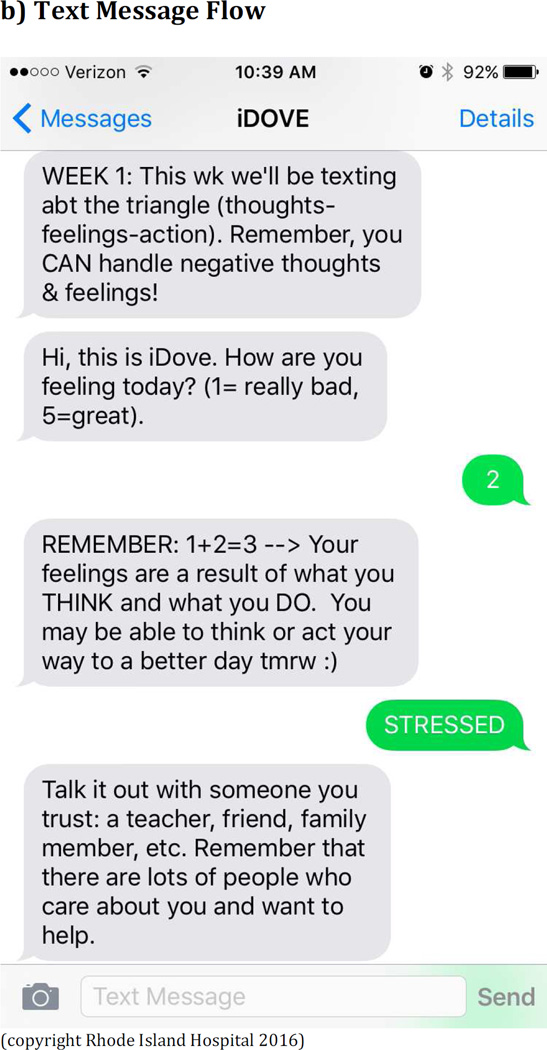

Figure 1.

Examples of in-ED session and text-message content

The text-message portion (programmed by Reify Health, Boston, MA) was structured to progressively enhance participants’ ability and motivation to identify feelings, modify thoughts and behavior, and engage positive social support (Table 1). Based on formative work(9, 10), three text-message content streams were created: for low-violence girls, low-violence boys, and high-violence adolescents of both genders. The streams had similar basic content, but differed slightly in types of behavioral activation activities, types of stressors, and language. “High-violence” was defined as a modified CTS-2 score higher than the mean score in the study’s formative phase. At enrollment, participants were assigned to the appropriate message stream and chose a time of day for message delivery.

Each day, participants received: 1) an automatically-delivered “mood” query, 2) an intervention message, pre-tailored to mood (defaulting to “negative mood” message if no response received within two hours). (Table 1) Participants could also request as-needed text-messages using keywords STRESSED, ANGRY, SAD.

For ethical reasons, the text-message system sent automatic replies to unexpected text-message responses, reminding participants of the lack of real-time monitoring and providing crisis hotline phone numbers. The RA checked text-message responses daily.

Measures

All surveys were completed using REDCAP.(21) At the close of the intervention, a semi-structured qualitative interview was conducted in person or over the phone.

Feasibility, Acceptability, and Usability

To measure feasibility, we report study recruitment and follow-up rates, percent of daily text-message queries answered, and distribution of participant-requested text-messages. To measure acceptability, we used a modified Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ). The CSQ contains eight questions about client satisfaction with mental health services. It has high internal consistency (α=0.91).(22) For this study, question 1 was separated into 3 parts (to separately assess satisfaction with in-person, text-message, and overall intervention).

Qualitative Feedback

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted by one trained RA. Topics included in-person and text-message topics (based on categories in Table 1), text-message program structure (e.g., length, frequency), and overall strengths and weaknesses of iDOVE. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Depressive symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-2) was administered at baseline and 8-week follow-up. The BDI-2 is one of the most widely used assessments of depressive symptoms and is validated for ages 13–80 (α=0.92–0.93).(23)

Potential covariates

Positive affect was measured using the positive affect subscale of the Affect Intensity and Reactivity Measure Adapted for Youth (AIR-Y) scale (α =0.90–0.94) at screening and follow-up.(24) The Violence Self-Efficacy Scale, a validated (α = 0.85) 5-item measure, assessed self-rated efficacy at avoiding fights.(25) Demographic characteristics (age, gender, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity) were measured using items from the National Survey on Adolescent Health.(26)

Analysis

Qualitative analysis was completed using thematic analysis(27), in which categories and sub-categories related to outcomes of interest were grouped together based on deductive (pre-determined, thematic) and inductive (data-driven) codes. The coding structure was iteratively refined until researchers reached consensus on a stable coding structure. Each transcript was independently coded by MLR and JRF, then discussed to ensure comprehensiveness of coding. Coded transcripts were entered into NVivo 10 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). Themes arose from the most salient codes; they were independently interpreted by MLR and JRF, compared for overlap, and discussed with the larger team.

Quantitative analyses were performed using STATA MP 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all measures. Likert-scale questions regarding usability and acceptability were analyzed using percentages. To assess changes in depressive symptoms (BDI-2) and potential covariates (modified CTS-2, AIR-Y, Violence Self-Efficacy) from baseline to follow-up, paired t-tests were calculated (to account for non-independence of baseline and follow-up). Baseline-observation was carried forward for participants with missing data.(28)

Results

Feasibility, Acceptability, and Usability

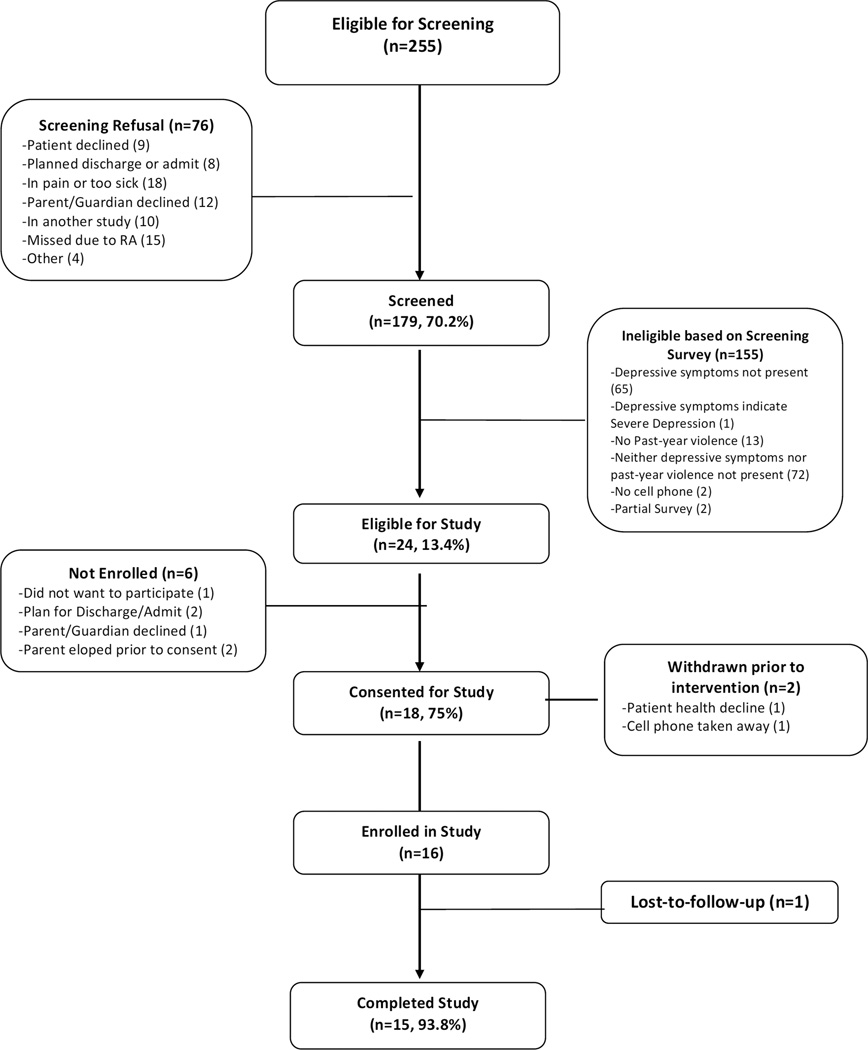

Of 255 patients eligible for screening, 179 (70.2%) completed screening; 13.4% (n=24) of these were eligible for iDOVE. Eighteen (75%) consented for the study; two were withdrawn prior to initiating the intervention due to changes in eligibility. Recruitment continued until the goal of enrolling 8 females and 8 males was reached (Figure 2). Five participants received the low-violence girl message stream; six received the low-violence boy message stream; and five (2 male, 3 female) received the high-violence message stream. Mean age was 15.4 years; the majority self-identified as non-White (66%) and non-Hispanic (87.5%); 63% received public assistance (Medicaid or free lunches); 37.5% had seen a therapist, counselor, or social worker in the prior year. Eleven participants were in the ED for medical complaints, and five for injuries.

FIGURE 2.

Study Flowchart

Fifteen of sixteen (93.8%) were retained at the 8-week follow-up. Interviews were conducted in-person (n=1) and over the phone (n=14).

Regarding usability, all participants replied to at least some of the 56 daily mood query text-messages (mean 44.8 [80% of total], range 5–56). Participants’ preferred time for the daily text-messages ranged from 2PM to 7PM (mean 3:38PM). Five participants (31%) requested on-demand messages (SAD, STRESSED, ANGRY) (mean 1.6 requests/participant, range 0–13). In-person ED sessions had high fidelity (mean 20/20) and competency (mean 54.8/56). Most participants (n=13, 86.67%) agreed or strongly agreed that iDOVE’s text-message system was easy to use. When asked whether iDOVE’s “various parts worked well together,” 80% (n=12) agreed or strongly agreed.

Regarding acceptability, the average rating on the modified Client Satisfaction Questionnaire was 80% (SD 15%; Cronbach’s alpha 0.95). Almost all (87%) rated both in-person and text-message portions of iDOVE as excellent or good (Table 2).

Table 2.

Measures of Acceptability: Participants Rating Aspects of Intervention as “Excellent/Good” (N=15)

| Survey Item | Percent |

|---|---|

| Overall Score: | Mean 32/40 (SD 6) |

| Individual Items: | |

| Quality of in-person session | 13 (87%) |

| Quality of text messages | 13 (87%) |

| Overall quality | 13 (87%) |

| Did you get the service you wanted? | 13 (87%) |

| Would you recommend iDove to a friend? | 13 (87%) |

| Has iDove helped you deal with problems more effectively? | 13 (87%) |

| Would you try iDove again? | 11 (74%) |

| Extent to which iDove has met your needs | 13 (87%) |

| How satisfied are you with help from iDove? | 13 (87%) |

| How satisfied are you with iDove? | 12 (80%) |

Qualitative Feedback

Follow-up interviews revealed four themes regarding the intervention (Table 3).

Table 3.

Qualitative Feedback

| Positive Quote | Negative Quote | |

|---|---|---|

| A Welcome, if Unexpected, Intervention |

I had no idea what I was signing up for. Honestly, I thought it was just gonna be asking me how how my day was going and you guys were gonna like put it in some data table or something, but the advice back was actually, I didn’t even expect it to be as good as it was, so, yeah, I liked it a lot … (#15, 17 y.o. M) Um, to be honest, I wasn’t really expecting it….I thought it was just going to be another day in the ER or something like that. [But] it was pretty interesting. (#7, 13 y.o. F) |

Yeah, I’m still kind of the same person as I was before…I’m a very stubborn person, you can’t change me (#16, 17 y.o. M) The iPad I was fine with, because I was kind of already laying there and I was bored out of my mind … It’s just like when we talked it was not like the right moment, cause I was kind of freaking out. (#10, 14 y.o. M) |

| Mood Check-In Was “Most Important” |

It was a question that I don’t ever get asked, like I get asked, “how are you?” but that’s like not specific enough, like, I might be feeling good, bad, I don’t…It’s like, kinda difficult to say how I feel, but then when you actually make me, that I have to actually give an answer and be like from one to five, generally one to five… It makes it a lot easier and it makes me, it helps me reflect and see how I actually feel other than just giving- saying “oh, I’m fine.” (#13, 15 y.o. M) Yeah, it’s like before I would have a hard time like talking to people, telling people how my day was but I’ve been doing this for a little bit and now it’s like, I find it easier to talk to people, like I can tell them how I’m doing like if it’s a bad day or a good day. (#14, 16 y.o. M) |

I guess, um when the message that I receive “How are you feeling today?” if we can actually say how we are feeling. Instead of using numbers, say how we’re feeling (#1, 15 y.o. F) Like [pause] like it was just like annoying doing it every day… Yea, it should have been like at the end of the week, you know what I mean? (#16, 17 y.o. M) |

| Uplifting Content |

What I what I think about that is, if my friend’s trying to put me down then I’m in control of what she or he has to say about me and I can like take it and I can go talk to that person and be like “why did you say this and this and this?” and that’s not true instead of just blowing it out into proport- into proportion and getting mad and frustrated, just go up to the person and ask them why they would say it…. They are helpful, because it helped me realize that I could better – like I could make my own decisions. (#4, 15 y.o. F) They were, they were really good, they helped me through, there was one, I know there was one incident where I wasn’t, I was having a really bad day, and I saw one of them that wa- that said um, it was like, “on good days, focus on the goals you have for yourself and the next stop to get there,” so it was like, I don’t know, it just made me happier. (#15, 17 y.o. M) |

It’s like all the same it ‘cuz like I said they’re they’re just different categories of the same thing. (#5, 15 y.o. F) |

| The Conundrum of Automation |

Um, I liked the text message more, ‘cuz I’m not really an open person, Like, I, like, there’s certain people I can like talk to, but I’ve known them for like ever, but, like, um, then the text messaging was kind of like, I felt kind of safe about it. Like, I’m not really saying like what’s going on, I’m just like putting a number, stuff like what I felt, and then you give information, like advice, and then, even if it didn’t help, it was still there. (#10, 14 y.o. M) It was helpful in like it helped me like emotional, because, like, it, when I was like, it would give, like, good feedback - when I was saying, if I was not feeling good or if I wasn’t feeling good about myself or depressed or anything. (#14, 16 y.o. M) |

Like um, when you say like how you’re feeling it would be nice if an actual person were to write out the message for you instead of it just being like an automated one…. Because then it’s just not like a randomly generated response like someone actually thought out like what to say to you. (#11, 14 y.o. F) Like, at some times it was, at times it felt repetitive, and at other times it felt like you didn’t really have a connection with it, and it felt like, sorta like a lesson at school or something, and like… That’s not what I kinda thought it would be like. Like, I thought it would be like really personal. (#13, 15 y.o. M) |

1) iDOVE was Welcome and Helpful, if Unexpected

In line with quantitative findings regarding acceptability, feasibility, and usability, all participants expressed strong qualitative enthusiasm about iDOVE:

“I would think ‘aw, I’m just gonna be upset all day,’ and then I’d receive a message and be like ‘hey, iDove texted me,’ and I’d just feel a little happier.” (#1, 15 y.o. F)

Almost all (13/15) felt iDOVE had been helpful in changing their thoughts, feelings, and actions. Many (10/15) cited the Cognitive Triangle when describing how change occurred: “Now I try to think before I say something and when I know I’m not in that great of a mood I try to do something to distract my mind” (#6, 17 y.o. F). The two participants who said the program was less helpful (#16, 17 y.o. M; #5, 15 y.o. F) spontaneously attributed this lack of helpfulness to their being “stubborn.”

Most participants (13/15) welcomed iDOVE’s initiation in the ED, despite not expecting a mental health intervention in this setting. Two participants, however, found it difficult to concentrate in the ED.

Many (9/15) highlighted that iDOVE was unexpectedly “simple,” particularly because it didn’t require them to “go out of my way” (#3). They appreciated that “it wasn’t just texting for fun or about drama, it was texting to help me” (#8, 14 y.o. M).

2) The Mood Check-In Was The “Most Important” Part

The daily check-in was almost universally (with the exception of #16, 17 y.o. M) articulated as a major strength. More than half (9/15) said the mood check-in was the “most important” element. They described the utility of this portion of iDOVE in multiple ways. Some appreciated its daily nature, saying that they would anticipate the check-in ahead of time. Others appreciated having to quantify their emotions.

Many (10/15) just liked knowing that “someone was listening” (#1, 15 y.o. F) to what their mood was each day, even if that “someone” was just a computer. Indeed, many commented that the anonymity of text-messaging provided allowed them to respond more honestly about their mood (see Theme 4 below).

Participants also mentioned that the queries helped them be aware of what constituted a good or bad day: “It’d be like a day-tracker almost, to see how I’m doing each day” (#15, 17 y.o. M). When asked to describe their overall perception of iDOVE, two participants used the mood query’s Likert-scale numbers to quantify its effect:

“[I]t went from me like going to like 3’s every day, or 2’s, 3’s or 2’s every day… to like 5’s” (#10, 14 y.o. M)

Three participants, however, suggested they would prefer using “feeling words” (e.g., replying “happy” or “sad”) instead of a Likert scale.

3) “Uplifting” Content

Participants found messages “motivating,” “reassuring,” “uplifting,” and “empowering” (spontaneously used in 11/15 interviews). Participants highlighted messages teaching self-efficacy, cognitive modifications, and problem-solving as particularly valuable. They said these messages reminded them they could handle life choices, verbal or physical fights, or disappointments. Many (9/15) said the messages reminded them of in-ED session content.

Only two participants had negative responses to messages on self-efficacy, saying these messages were too general and anodyne.

4) “Relatability”: The Conundrum of Automation

Whether the automated program was adequately “relatable” and “personal” was a common theme. These words or their stems were mentioned by 14 participants.

Many (12/15) participants appreciated the automation, even saying that its automated nature was the “key part” (#15, 17 y.o. M) because “they won’t feel so like judged” (#4, 15 y.o. F). Despite knowing the program was automated, some participants still felt as if a person were checking in:

“…even if there’s like just a machine texting me, like it was a person, you know, they’re just still supporting and then just kept reminding me to um to just think and relax myself.” (#13, 15 y.o. M)

Many (8/15) believed messages were useful even when not specifically applicable to their situation. Some (4/15), however, were concerned that automation limited iDOVE’s ability to give adequately personal advice. Some suggested the messages should respond not just to mood, but also to the specific situation that caused their mood.

“So if I sent a 2 because I got in a fight with my mom it would send me a message about… something that like didn ‘t really have to do with the situation…. And it would take longer for me to kind of get myself back up than if I got a message that was like more related.” (#3, 17 y.o. F)

Some said that when iDOVE did provide situation-specific advice, it missed the mark. As iDOVE did not receive input on nor respond to each participant’s specific situation, it sometimes (according to the same participant), “was like taking advice about something that didn’t really happen.” (#3, 17 y.o. F)

To address this dilemma, a few (3/15) participants suggested more human contact, such as incorporating the ability to call or text a real person. One participant suggested using the 1–5 mood scale and then having the program ask why they answered that way (#5, 15 y.o. F).

Quantitative changes in depressive symptoms and covariates

The mean baseline BDI-2 score was 14.9 (SD 9.3), versus 9.9 at follow-up (SD 8.7), corresponding to a change from mild to minimal depressive symptoms.(23) The mean ΔBDI-2 from baseline to eight-week follow-up was −4.9 (95% CI −9.0- - 0.85, t(15)=2.6, p=0.02). Statistically significant differences were also found in the AIM score (positive affect) between baseline (53.1, SD 9.8) and follow-up (59.8, SD 14.4) (Δ6.7, 95% CI 0.75–12.6, t(15)=2.4, p=0.03), and in Violence Self-Efficacy (baseline 10.8, SD 4.6; follow-up 13.13, SD 4.13; Δ=2.38, SD 3.1; t(15)=3.1, p=0.007). Past-two-month self-reported physical peer violence (measured with a modified CTS-2) did not differ significantly between baseline (3.88 +/− 3.54) and follow-up (3.63 +/− 4.75) (p=0.8).

Discussion

This mixed-methods pilot study demonstrates that iDOVE - an innovative brief in-person session initiated during an ED visit, followed by a longitudinal two-way text-message curriculum - is acceptable, feasible, and shows promise for improving depressive symptoms among high-risk adolescents. Others have demonstrated high satisfaction and a trend toward efficacy for adjunctive mobile health interventions for adolescents engaged in longitudinal treatment. (29) To our knowledge, our study is the first to indicate the acceptability and feasibility of initiating mobile mental health interventions in the ED setting.

Although patients are enthusiastic in theory about mobile mental health interventions, they often fail to engage. (30) Our study, in contrast, showed high participant engagement. Our highly diverse ED population - mostly of minority race or ethnicity and low socioeconomic status - had high access to text-messaging (similar to American adolescents in general(31)). And of those eligible, 75% enrolled in the study.

We observed high response rates to daily assessments (80%) and high follow-up rates (94%) - despite participants being in the ED for chief complaints unrelated to the intervention topic. These engagement and retention rates are much higher than in other ED-initiated text-messaging interventions or other digital mental health interventions(13, 30, 32); for instance, one digital CBT intervention, combining in-person sessions with text-messaging, reported that only 38% of daily messages received responses.(29) iDOVE’s surprisingly high degree of engagement may be explained in multiple ways.

First, according to qualitative data, iDOVE filled an unmet need in participants’ lives. Participants described an awareness of their lack of support systems, whether because of personal or structural barriers. Our results reinforce the importance of developing accessible, developmentally-appropriate mental health preventive interventions for adolescents.(33)

Second, participants found the intervention “uplifting,” and gave both the in-person and text-message portions of the intervention higher satisfaction ratings than reported by other technology-based mental health interventions.(34) Prior literature(12, 35) and our own formative work(9, 10) emphasize the importance of a positive tone and of participant-relevant language in automated interventions. Accordingly, all aspects of iDOVE’s content and structure were iteratively refined prior to this pilot to reflect participants’ own experiences, literacy levels, and definitions of “positive” language, using a human-centric, qualitative approach.(9, 10) We suspect that this rigorous, theoretically-grounded development process and high attention to tone impacted engagement.(36)

Third, participants may have engaged because they perceived iDOVE as helpful. Others’ work suggests that perceived efficacy is a major determinant of intervention engagement.(37) Quantitatively, iDOVE is promising: reductions in depressive symptoms and improvements in potential mediators of depression (positive affect and self-efficacy in avoiding fights) were observed. Qualitatively, participants described feeling like they were helped by the intervention. Participants described easily comprehending the concepts of cognitive behavioral therapy – and even gave concrete, unsolicited examples of applying these concepts to their life. The daily mood assessment, in and of itself, may also have served as an intervention. Self-assessment has been shown to influence outcomes of therapy.(38) Participants’ active engagement with the material may both signal an intervention’s value and increase its effect.(39) Future research, including longer-term follow-ups and randomized comparisons, is critical to demonstrate true efficacy.

This study also provides an important caution for future work on digital mental health interventions. Participants articulated strong but conflicting opinions about how best to balance desires for ease of access and anonymity with the desire for a human touch and “relatability.”(10, 40) Many participants said the fact that “no one was there” was one of their most-liked aspects of iDOVE; they felt iDOVE’s automated two-way programming was adequately interactive. However, the popularity of text-message-based interventions such as CrisisText, which provide personal interactions with trained volunteers, highlight the need for additional research on blending human components into mental health technology.(11) Participants’ varying degrees of desired personalization and human contact is epitomized by the use of iDOVE’s on-demand messages: of the 30% of iDOVE participants who used this feature, most requested multiple messages. Future work may consider ways to meld a standardized, automatic curriculum with on-demand human interaction, and to test the relative value of each component. For instance, natural language processing or geospatial location data could be used as an adjunct to daily mood ratings, to improve personalization.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this mixed-methods study is that it was an open pilot study, with a small sample size and no control group. Quantitative changes in symptoms may reflect the natural course of symptomatology after an ED visit. A larger sample and a control group are necessary for conclusions about efficacy. Additionally, this study was conducted at a single site with exclusively English-speaking adolescents who had access to a cellphone. Although language and phone access were rarely criteria for exclusion, future work should better quantify the effects in a diverse population. Other recruitment sites, such as the juvenile justice system, may produce different results.

Conclusions

Participants’ high satisfaction and 80% daily engagement in this eight-week intervention emphasize the importance of creating positive, relevant, interactive, and theory-based digital health tools. To our knowledge, no prior work demonstrates the feasibility and acceptability of text-message mental health interventions in the ED. This study reinforces the appropriateness of the text-message modality for adolescent mental health; it also highlights the acceptability of initiating mental health preventive interventions for adolescents in settings where preventive needs are not typically addressed. Future work should enhance personalization of digital mental health interventions, and should test interventions in fully powered randomized controlled trials.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

iDOVE, a brief in-person and 8-week automated text-message depression prevention intervention for high-risk adolescents, had high participant retention, text-message use, and satisfaction. Participants’ biggest concern was balancing accessibility and privacy with “relatability.” This study supports implementing text-message mental health interventions for adolescents, and provides suggestions for future interventions.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This study was funded by NIMH K23 MH095966. The study sponsor had NO role in (1) study design; (2) the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; (3) the writing of the report; or (4) the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Ranney discloses that she is a medical advisor for StudyCue LLC (unrelated to the study). First draft was written by Megan L. Ranney.

We acknowledge Shubh Agrawal for her dedication to patient recruitment, and John Patena and Margaret Thorsen for invaluable assistance during the early phases of this study.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AIR-Y

Affect Intensity and Reactivity Measure Adapted for Youth

- BDI-2

The Beck Depression Inventory

- CBT

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- CSQ

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire

- CTS-2

Conflict Tactics Scale 2nd ed.-revised

- ED

Emergency department

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- RA

Research assistant

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The data was presented in abstract form at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine’s Annual Meeting, May 2015, San Diego, CA.

References

- 1.Grupp-Phelan J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Trends in mental health and chronic condition visits by children presenting for care at U.S. emergency departments. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:55–61. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson KM, Klein JD. Adolescents who use the emergency department as their usual source of care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:361–365. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grupp-Phelan J, Delgado SV, Kelleher KJ. Failure of psychiatric referrals from the pediatric emergency department. BMC Emerg Med. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranney ML, Walton M, Whiteside L, et al. Correlates of depressive symptoms among at-risk youth presenting to the emergency department. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hilt LM. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, et al. A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:603–611. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merikangas KR. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baren JM, Mace SE, Hendry PL, et al. Children's mental health emergencies-part 1: Challenges in care: Definition of the problem, barriers to care, screening, advocacy, and resources. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:399–408. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318177a6c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranney ML, Choo EK, Cunningham RM, et al. Acceptability, Language, and Structure of Text Message-Based Behavioral Interventions for High-Risk Adolescent Females: A Qualitative Study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranney ML, Thorsen M, Patena JP, et al. ‘You need to get them where they feel it’: Conflicting Perspectives on How to Maximize the Structure of Text-Message Psychological Interventions for Adolescents. Proceedings of the 48th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences: IEEE & Computer Society Press; 2015. pp. 3247–3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregory A. R U There? A new counselling service harnesses the power of the text message. The New Yorker. New York: Condé Nast; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, et al. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;97:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suffoletto B, Kristan J, Chung T, et al. An Interactive Text Message Intervention to Reduce Binge Drinking in Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial with 9-Month Outcomes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranney ML, Choo EK, Wang Y, et al. Emergency department patients' preferences for technology-based behavioral interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:218–227. e248. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, et al. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walton M, Chermack S, Shope J, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:527–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham RM, Chermack ST, Zimmerman MA, et al. Brief motivational interviewing intervention for peer violence and alcohol use in teens: one-year follow-up. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1083–1090. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stice E, Rohde P, Gau JM, et al. Efficacy trial of a brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents: Effects at 1- and 2-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:856–867. doi: 10.1037/a0020544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, et al. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann. 1982;5:233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Brown G, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory II Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones RE, Leen-Feldner EW, Olatunji BO, et al. Psychometric properties of the Affect Intensity and Reactivity Measure adapted for Youth (AIR-Y) Psychological assessment. 2009;21:162–175. doi: 10.1037/a0015358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosworth K, Espelage D. Teen conflict survey. Bloomington, IN: Center for Adolescent Studies, Indiana University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, et al. The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: Research design. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- 27.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Interscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobak KA, Mundt JC, Kennard B. Integrating technology into cognitive behavior therapy for adolescent depression: a pilot study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2015;14:37. doi: 10.1186/s12991-015-0077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waller R, Gilbody S. Barriers to the uptake of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative evidence. Psychol Med. 2009;39:705–712. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenhart A. Teens, Social Media & Technology Overview 2015: Pew Research Center. 2015. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittaker R, Merry S, Stasiak K, et al. MEMO - A mobile phone depression prevention intervention for adolescents: development process and postprogram findings on acceptability from a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e13. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seko Y, Kidd S, Wiljer D, et al. Youth mental health interventions via mobile phones: a scoping review. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17:591–602. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donker T, Bennett K, Bennett A, et al. Internet-delivered interpersonal psychotherapy versus internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled noninferiority trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e82. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muench F, van Stolk-Cooke K, Morgenstern J, et al. Understanding messaging preferences to inform development of mobile goal-directed behavioral interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar S, Nilsen WJ, Abernethy A, et al. Mobile health technology evaluation: The mHealth Evidence Workshop. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Musiat P, Goldstone P, Tarrier N. Understanding the acceptability of e-mental health--attitudes and expectations towards computerised self-help treatments for mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kazdin AE. Reactive self-monitoring: the effects of response desirability, goal setting, and feedback. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:704–716. doi: 10.1037/h0037050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bendelin N, Hesser H, Dahl J, et al. Experiences of guided Internet-based cognitive-behavioural treatment for depression: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohr DC, Cuijpers P, Lehman K. Supportive accountability: a model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]