Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the short-term effectiveness of overminus spectacles in improving control of childhood intermittent exotropia (IXT)

Design

Randomized clinical trial

Participants

58 children 3 to <7 years old with IXT. Eligibility criteria included a distance control score of 2 or worse (mean of 3 measures during a single examination) on a scale of 0 (exophoria) to 5 (constant exotropia), and spherical equivalent refractive error between −6.00 diopters (D) and +1.00D

Intervention

Children were randomly assigned to either overminus spectacles (−2.50D over cycloplegic refraction) or observation (non-overminus spectacles if needed, or no spectacles) for 8 weeks.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was distance control score for each child (mean of 3 measures during a single examination) assessed by masked examiner at 8 weeks. Outcome testing was conducted with children wearing their study spectacles, or plano spectacles for observation group children who did not need spectacles. The primary analysis compared mean 8-week distance control score between treatment groups using an analysis of covariance model which adjusted for baseline distance control, baseline near control, pre-study spectacle wear, and prior IXT treatment. Treatment side effects were evaluated using questionnaires completed by parents.

Results

At 8 weeks, mean distance control was better in the 27 children treated with overminus spectacles than in the 31 children who were observed without treatment (2.0 vs 2.8 points, adjusted difference = −0.75 points favoring the overminus group; two-sided 95% confidence interval = −1.42 to −0.07 points). Side effects of headaches, eyestrain, avoidance of near activities, and blur appeared similar between treatment groups.

Conclusions

In a pilot randomized clinical trial, overminus spectacles improved distance control at 8 weeks in children 3 to <7 years old with IXT. A larger and longer randomized trial is warranted to assess the effectiveness of overminus spectacles in treating IXT, particularly the effect on control after overminus treatment has been discontinued.

Introduction

Intermittent exotropia (IXT), the most common form of childhood exotropia,1–4 is characterized by normal ocular alignment some of the time and a manifest exotropia at other times. While surgery is often considered for treatment, many cases of IXT are treated using non-surgical interventions such as overminus lenses or occlusion.5–8 Overminus lens therapy involves wearing full-time spectacles that have additional minus power over the cycloplegic refractive correction and is prescribed by some eye care providers to improve control and/or to reduce the angle of the exodeviation as a primary treatment or as a temporizing treatment in young children before surgery or orthoptic therapy is considered.9 One proposed mechanism for improvement with overminus lens therapy is that stimulation of accommodative convergence either reduces the angle of exodeviation or triggers reflex convergence.5, 10 An alternative hypothesis is that fusional convergence is exerted to control the exodeviation, inducing convergence accommodation and distance blur, and that overminus lenses may allow clear distance vision, facilitating fusion.11

In some patients, overminus lenses alone appear to be successful in treating IXT, with eventual weaning of the overminus lenses to a point at which the IXT is well controlled in the regular refractive correction.12, 13 Nevertheless, previous studies of overminus lens therapy have been limited to retrospective case series without comparison groups, and have varied in terms of methods used to determine amount of overminus power, treatment duration, and outcome measures.10, 12–19 The objective of this pilot randomized trial was to evaluate the initial, short-term effectiveness of prescribing overminus lens therapy to improve control of IXT among children 3 to 6 years of age in order to determine if a full-scale randomized clinical trial should be conducted to evaluate its long-term effectiveness, particularly after overminus treatment has been discontinued.

Methods

The study was supported through a cooperative agreement with the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health and was conducted by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group (PEDIG) at 21 clinical sites according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)–compliant informed consent forms were approved by institutional review boards, and a parent or guardian of each study participant gave written informed consent. An independent data and safety monitoring committee provided oversight. The study is listed on www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02223650, URL accessed 2/9/16) and the full protocol is available at www.pedig.net (URL accessed 2/9/16).

Eligibility Criteria

The study included children 3 to <7 years of age with spherical equivalent (SE) refractive error between −6.00D and +1.00D inclusive and IXT meeting the following criteria: 1) intermittent or constant exotropia at distance (mean of 3 baseline assessments of distance control18–20 ≥2 points) (Table 1), 2) IXT, exophoria, or orthophoria at near (at least 1 of 3 assessments of near control at the baseline visit ≤4 points), 3) distance exodeviation at least 15Δ measured by prism and alternate cover test (PACT), and 4) near deviation not exceeding the distance deviation by >10Δ by PACT (i.e., convergence insufficiency type IXT excluded). Prior non-surgical treatment for IXT was not permitted within the 6 months preceding enrollment. Appropriate spectacle correction was required to be worn for at least one week prior to enrollment for children whose refractive error met certain pre-study criteria for correction (Table 2, criterion #11). Previous IXT treatment with spectacles overminused by ≥1.00D SE was an exclusion criterion; however, low levels of uncorrected hyperopia (±1.0 D) were not considered overminus. Additional eligibility criteria are shown in Table 2 (online only).

Table 1.

Exotropia Control Assessment Procedure

Control of exodeviation will be measured at distance and near using the Office Control Score.20

|

| The scale below applies to both distance and near separately. |

| Intermittent Exotropia Control Scale |

| 5 = Constant Exotropia |

| 4 = Exotropia > 50% of the 30-second period before dissociation |

| 3 = Exotropia < 50% of the 30-second period before dissociation |

| 2 = No exotropia unless dissociated, recovers in >5 seconds |

| 1 = No exotropia unless dissociated, recovers in 1–5 seconds |

| 0 = No exotropia unless dissociated, recovers in <1 second (phoria) |

| Not applicable = No exodeviation present |

|

Directions: Step1: Assessment before any dissociation: Levels 5 to 3 are assessed during a 30-second period of observation; first at distance fixation and then at near fixation for another 30-second period. Both distance and near are assessed before any dissociation (i.e., before step 2, when assessing control scores of 0, 1 and 2). If the participant is spontaneously tropic (score 3, 4 or 5) at a specified test distance, then step 2 (assessment after standard dissociation) is skipped at that specific test distance. Step 2: Assessment with standardized dissociation: If no exotropia is observed during step 1 (i.e. the 30-second period of observation at the specified test distance), levels 2 to 0 are then assessed as the worst of 3 rapidly successive trials of dissociation:

|

| If the patient has a micro-esotropia by cover test but an exodeviation by PACT, the scale applies to the exodeviation. |

Enrollment Testing

At the enrollment visit, control of the exodeviation was measured at distance (6 meters) and at near (1/3 meters) using the Office Control Score,19, 20 which ranges from 0 (phoria, best control) to 5 (constant exotropia, worst control) (Table 1). Due to the variability of single measures of control, we used the “triple control score,”21, 22 a mean of 3 measures obtained at specific time-points during a 20- to 40-minute office examination.

Following an initial control assessment, near stereoacuity was assessed using the Randot® Preschool Stereoacuity test (Stereo Optical Co., Inc., Chicago, IL) at 40 centimeters, and magnitude of exodeviation was assessed at distance (6 meters) and near (1/3 meter) using the PACT. The control assessment was then performed a second time, followed by measurement of monocular distance visual acuity (VA) by a certified examiner using the Amblyopia Treatment Study (ATS) HOTV©23, 24 testing protocol, and binocular near visual acuity testing using the ATS4 test (Precision Vision, La Salle, IL). Finally, a third control assessment was performed. All three control assessments and the PACT were performed by the same study-certified examiner (either a pediatric ophthalmologist, pediatric optometrist, or certified orthoptist).

In addition to the clinical testing, the participant’s parent completed a 7-item (see Tables 3a and 3b – online only) written survey of symptoms and problems that might be associated with over-minus spectacle wear such as headaches and eye strain based on their observations in the past 2 weeks. Survey items were derived based on expert opinion of pediatric ophthalmologists and optometrists on the study planning committee. The response options were a 5-point Likert-type scale based on frequency of observations: never = score of 0, almost never = 1, sometimes = 2, often = 3, and always = 4.

Randomization

After data were entered on the PEDIG website and eligibility verified, participants were randomly assigned (using a permuted block design stratified by mean distance control score [2 to <3, 3 to <4, 4 to 5 points]) with equal probability to either overminus treatment or observation.

Treatment Regimens

Participants assigned to the overminus group were prescribed spectacles with −2.50D added to the sphere power of the cycloplegic refraction. Overminus spectacles were prescribed for all waking hours for 8 weeks, and no other IXT treatments were allowed during this time.

Participants assigned to the observation group received no treatment other than non-overminus refractive correction, if needed based on post-randomization correction criteria which were more rigorous than the pre-study correction criteria in requiring correction of smaller amounts of astigmatism (>0.50D) and anisometropia (>0.50D). Observation group participants who did not need refractive correction were prescribed plano lens spectacles which were to be worn for outcome testing at the 8-week visit but were not to be worn in the interim. The sole purpose of the plano lens spectacles was to maintain masking of examiners for outcome testing at the 8-week visit by ensuring that all participants in both treatment groups would be tested while wearing spectacles.

Follow-up Visit

Follow-up consisted of a single visit 8 weeks (±2 weeks) after randomization. Before the clinical testing, parents completed the 7-item survey which asked about symptoms experienced by their child since the start of the study. An unmasked examiner assessed compliance with overminus spectacle wear. Compliance was judged to be excellent (glasses worn >75% of waking hours), good (51% to 75%), fair (26% to 50%), or poor (≤25%), based on discussions with the parent. Afterwards, clinical testing was performed in the same order as at enrollment with all participants wearing spectacles (overminus spectacles for the overminus group; non-overminus or plano lens spectacles for the observation group). The three assessments of control and the PACT testing were performed by an examiner who was masked to the participant’s treatment group. If the spectacles were not brought to the visit, the participant was tested in trial frames prepared by an unmasked examiner who covered the lens power markings with tape.

Statistical Methods

The planned sample size of 54 participants was not statistically calculated, but rather was a convenience sample expected to provide at least 50 participants (25 participants per group) for analysis after adjusting for up to 5% loss to follow-up. Nevertheless, a priori the study had 88% power to detect a treatment group difference in mean 8-week distance control score, assuming a true difference of −0.75 points or larger (overminus minus observation) with a standard deviation of 0.926 (based on prior IXT studies), and using a 1-sided test with alpha=0.05.

The primary analysis was an intention-to-treat treatment group comparison of mean 8-week distance control using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model which adjusted for baseline distance control. Pre-study spectacle wear, prior IXT treatment, and baseline near control were included in the ANCOVA model to address potential confounding due to slight imbalances between treatment groups. A 1-sided hypothesis test using alpha=0.05 was used to determine whether the overminus group had better 8-week mean distance control than the observation group in this pilot study, to inform the decision whether to proceed with a full-scale, longer-term randomized trial. The treatment group difference in mean distance control was also calculated, along with a two-sided 95% exact confidence interval (CI), to provide a range of likely values for the estimate. Two sensitivity analyses yielded similar results: 1) an analysis that excluded 1 participant not tested in study spectacles or plano glasses (an overminus group participant tested in trial frames with the overminus correction), and 2) a post-hoc analysis that excluded 4 observation group participants who had either (non-overminus) refractive correction prescribed for the first time or a change in (non-overminus) refractive correction at baseline (data not shown).

The secondary analysis was a treatment group comparison of the proportion of participants who demonstrated a treatment response, defined as 1 or more point improvement in mean distance control between baseline and the 8-week outcome exam. A one-sided Barnard’s exact test with alpha=0.05 determined whether the overminus group had a higher proportion of participants with treatment response compared with the observation group in the pilot study, to also inform the decision whether to proceed with a full-scale, longer-term treatment trial. The treatment group difference in proportion of participants with treatment response was also calculated along with the two-sided exact 95% CI to provide a range of likely values for the estimate. The same two sensitivity analyses performed for the primary analysis were also performed and yielded similar results to the secondary analysis (data not shown). Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models were used to assess potential confounding due to treatment group imbalances in pre-study spectacle wear, pre-study treatment for IXT, and baseline near control.

Means for continuous 8-week outcomes of near exotropia control, PACT (distance and near), and stereoacuity were compared between treatment groups using ANCOVA models which included the baseline level of the outcome being evaluated. For analysis, stereoacuity was converted from seconds of arc scores to log arcsec values (in parentheses) as follows: 40 (1.60), 60 (1.78), 100 (2.00), 200 (2.30), 400 (2.60), 800 (2.90); participants with no detectable (nil) stereoacuity were assigned a value of 1600 (3.20). Barnard’s exact tests were used to compare treatment groups on post hoc outcomes of the proportion of participants with 8-week exotropia control scores that improved both >=1 point and >=2 points separately for each of distance and near. In addition, 8-week distance control mean, change from baseline, and proportion with improvement ≥1 point were tabulated for each treatment group stratified by baseline distance control (2 to <3 points, 3 to <4 points, 4 to 5 points). The primary analysis ANCOVA model was also used to assess the effect of baseline distance control on 8-week outcome in both treatment groups. In an exploratory analysis, we tested for interaction of continuous baseline distance control and treatment effect. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Between December 2014 and May 2015, 58 children were enrolled at 21 sites, with 31 participants assigned to observation and 27 to overminus treatment. Mean age was 5.1 (±1.1) years, 36 (62%) were female, and 29 (50%) were white (Table 4). The mean control score at enrollment was 3.2 (±1.1) points at distance and 1.4 (±1.1) points at near (Table 5).

Table 4.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Treatment Group (N=58)

| Observation (N=31) | Overminus (N=27) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Sex: Female | 18 | 58 | 18 | 67 |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 15 | 48 | 14 | 52 |

| Black/African American | 4 | 13 | 2 | 7 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 | 29 | 6 | 22 |

| Asian | 3 | 10 | 5 | 19 |

|

| ||||

| Age at randomization, years | ||||

| 3 to <4 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 26 |

| 4 to <5 | 11 | 35 | 4 | 15 |

| 5 to <6 | 10 | 32 | 9 | 33 |

| 6 to <7 | 7 | 23 | 7 | 26 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.2 (1) | 5.1 (1.2) | ||

| Range | 3.4 to 6.8 | 3.0 to 7.0 | ||

|

| ||||

| Refractive error in more myopic eyea (spherical equivalent, D) | ||||

| >+0.50 to +1.00 | 15 | 48 | 13 | 48 |

| 0 to +0.50 | 9 | 29 | 5 | 19 |

| <0 to >−0.50 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| −0.50 to >−1.00 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 15 |

| −1.00 to >−1.50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| −1.50 to >−2.00 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| −2.00 to >−2.50 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| −2.50 to >−3.00 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| <= −3.00 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Median | 0.38 | 0.25 | ||

| Mean (SD) | −0.04 (1.47) | −0.05 (1.40) | ||

| Range | −5.25 to +1.00 | −6.00 to +1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| Spectacle wear (pre-study)b | 7 | 23 | 10 | 37 |

|

| ||||

| Prior IXT treatment | 3 | 10 | 6 | 22 |

| Patching | 2 | 6 | 6 | 22 |

| Home anti-suppression treatment | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Preschool Randot near stereoacuity, arcsec (logarcsec)c | ||||

| 40″ (1.6 logarcsec) | 4 | 13 | 3 | 12 |

| 60″ (1.78 logarcsec) | 9 | 30 | 4 | 15 |

| 100″ (2.0 logarcsec) | 7 | 23 | 6 | 23 |

| 200″ (2.3 logarcsec) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| 400″ (2.6 logarcsec) | 4 | 13 | 4 | 15 |

| 800″ (2.9 logarcsec) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Nil (3.1 logarcsec) | 4 | 13 | 5 | 19 |

| Median (log arcsec) | 2.00 | 2.15 | ||

| Mean (SD) (log arcsec) | 2.16 (0.54) | 2.34 (0.57) | ||

| Range (log arcsec) | 1.60 to 3.20 | 1.60 to 3.20 | ||

|

| ||||

| AC/A ratiod | ||||

| <2.5 | 13 | 42 | 12 | 44 |

| 2.5 to 6.0 | 15 | 48 | 12 | 44 |

| >6.0 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 11 |

IXT = intermittent exotropia

More myopic eye refers to the eye with the numerically lowest spherical equivalent refractive error.

After randomization, for the 31 participants assigned to the observation group: 6 (19%) continued their pre-study refractive correction, 1 (3%) was prescribed a change in refractive correction, 3 (10%) were prescribed refractive correction for the first time (2 participants did not require refractive correction for eligibility but did require refractive correction under the more rigorous post-randomization criteria; 1 participant was electively prescribed correction for minimal refractive error), and 21 (68%) were prescribed plano lenses to be brought to the 8-week visit (not to be worn in the interim).

Randot Preschool stereoacuity is missing for 1 participant in the observation group and 1 participant in the overminus group because the participant did not understand the test (i.e., failed the pretest).

Accommodative convergence over accommodation (AC/A) ratio calculated by taking the difference between the distance (6m) PACT measurements with the participant wearing habitual correction and with the participant wearing −2.00D lenses over the habitual correction, and dividing the difference by 2.

Table 5.

Baseline Exotropia Control and Angle Magnitude by Treatment Group (N=58)

| Distance Alignment | Near Alignment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Observation (N=31) | Overminus (N=27) | Observation (N=31) | Overminus (N=27) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Exotropia control* | ||||||||

| 0 to <1 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | 11 | 35 | 7 | 26 |

| 1 to <2 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | 9 | 29 | 12 | 44 |

| 2 to <3 | 13 | 42 | 12 | 44 | 6 | 19 | 5 | 19 |

| 3 to <4 | 7 | 23 | 6 | 22 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 7 |

| 4 to 5 | 1 | 35 | 9 | 33 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.0) | ||||

| Range | 2 to 5 | 2 to 5 | 0 to 4 | 0 to 4 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| PACT exodeviation (Δ)** (in habitual correction) | ||||||||

| No exodeviation (orthophoria) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–9 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | 3 | 10 | 2 | 7 |

| 10–15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 35 | 10 | 37 |

| 16–18 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 13 | 4 | 15 |

| 20–25 | 19 | 61 | 18 | 67 | 10 | 32 | 8 | 30 |

| 30–35 | 8 | 26 | 5 | 19 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 7 |

| 40–45 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Mean (SD) | 25 (6) | 24 (7) | 18 (8) | 18 (8) | ||||

| Range | 16 to 45 | 15 to 45 | 6 to 45 | 6 to 40 | ||||

Δ = prism diopter; PACT = Prism and Alternate Cover Test; SD = standard deviation

---- indicates not applicable

Mean of three assessments performed throughout the exam. Mean distance exotropia control of 2 points or greater (worse) was required for eligibility. Mean near exotropia control of less than 5 points (i.e., could not be constant on all 3 of the measures) was required for eligibility.

PACT at distance was required to be at least 15Δ for eligibility. In addition, near deviation could not exceed distance deviation by more than 10Δ by PACT for eligibility (i.e., convergence insufficiency type IXT was excluded).

For the 31 participants assigned to the observation group, 6 (19%) continued their pre-study refractive correction, 1 (3%) was prescribed a change in refractive correction, 3 (10%) were prescribed refractive correction for the first time (2 participants did not require refractive correction for eligibility but did require refractive correction under the more rigorous post-randomization criteria; 1 participant was electively prescribed correction for minimal refractive error), and 21 (68%) were prescribed plano lenses to be brought to the 8-week visit (not to be worn in the interim).

Visit Completion

The 8-week visit was completed by all 31 participants in the observation group (all of whom completed the visit within the protocol-specified time window of 8 weeks ±2 weeks), and by all 27 participants in the overminus group (24 [89%] of whom completed the visit within the protocol-specified time window). A masked examiner assessed the primary and secondary outcomes in all cases.

Compliance with Overminus Spectacle Wear

In the overminus group, potentially delayed receipt of overminus spectacles and the timing of the 8-week outcome visit allowed for a variable number of weeks of possible spectacle wear immediately preceding the outcome examination: 4 to <5 weeks in 4 (15%) participants, 5 to <6 weeks in 3 (11%) participants, 6 to <7 weeks in 4 (15%), 7 to <8 weeks in 11 (41%) participants, and 8 or more weeks in 5 (19%) participants (mean = 7 weeks; range = 4 to 11 weeks).

At the 8-week visit, compliance with overminus spectacles in the overminus group was judged to be excellent in 20 (74%) participants, good in 4 (15%), fair in 1 (4%), and poor in 2 (7%).

Refractive Correction for Outcome Testing

In the overminus group, the 8-week outcome was assessed for 26 participants (96%) while wearing their overminus spectacles and for 1 participant (4%) while wearing trial frames with the overminus correction. In the observation group, the 8-week outcome was assessed for 10 participants (33%) while wearing spectacles with refractive correction and for 21 (68%) participants while wearing plano lens spectacles, because they did not require refractive correction.

Efficacy Analyses

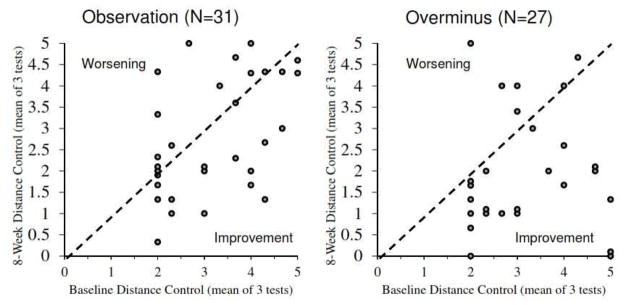

The primary outcome of adjusted 8-week mean distance control was 2.0 points in the 27 participants in the overminus group versus 2.8 points in the 31 participants in the observation group (P = 0.01 for one-sided test of the hypothesis that mean distance control is better in the overminus group vs. the observation group), supporting development of a full-scale longer-term randomized trial based on our a priori criterion of P ≤0.05. The adjusted difference in mean 8-week control was −0.75 points (two-sided 95% CI = −1.42 to −0.07 points), favoring the overminus group (Table 6) (Figure 1). The 8-week distance control improved ≥1 point from baseline in 16 (59%) of the overminus group versus 12 (39%) of the observation group (P = 0.07 for one-sided test of the hypothesis that the overminus group had a higher proportion of participants with treatment response compared with the observation group), supporting development of a full-scale longer-term randomized trial based on our a priori criterion of ≥20% more participants with treatment response in the overminus group. The treatment group difference in the proportion of participants with treatment response was 21% (two-sided 95% CI = −6% to 45%). Adjusted and unadjusted exact logistic regression models yielded similar results.

Table 6.

Exotropia Control at 8-week Outcome (Average of 3 Measurements) (N=58)a

| Distance Alignment | Near Alignment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Observation (N=31) | Overminus (N=27) | Observation (N=31) | Overminus (N=27) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| 8-week Control Score (points) | ||||||||

| 0 to <1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 15 | 10 | 32 | 15 | 56 |

| 1 to <2 | 7 | 23 | 11 | 41 | 13 | 42 | 7 | 26 |

| 2 to <3 | 10 | 32 | 5 | 19 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 7 |

| 3 to <4 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 16 | 2 | 7 |

| 4 to 5 | 10 | 32 | 6 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.1) | 0.9 (1.2) | ||||

| Range | 0.3 to 5.0 | 0.0 to 5.0 | 0.0 to 3.7 | 0.0 to 4.0 | ||||

| Difference in means (two-sided 95% CI) | −0.75 (−1.42 to −0.07)a | −0.24 (−0.68 to 0.19)a | ||||||

| Change from Baseline to 8 Weeks (points)b | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | −0.4 (1.3) | −1.2 (1.8) | −0.3 (1.1) | −0.4 (0.9) | ||||

| Range | −3.0 to 2.3 | −5.0 to 3.0 | −3.7 to 1.7 | −2.0 to 2.0 | ||||

| Improved ≥1 Pointc | 12 | 39 | 16 | 59 | 8 | 26 | 7 | 26 |

| Difference (two-sided 95% CI) | 21% (−6% to 45%) | 0.001% (−23% to 24%) | ||||||

| Improved ≥2 Pointsd | 4 | 13 | 9 | 33 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 11 |

| Difference (two-sided 95% CI) | 20% (−2% to 44%) | 5% (−12% to 24%) | ||||||

Difference in mean distance control (overminus – observation) and 95% confidence intervals are from ANCOVA model adjusting for baseline distance control, baseline near control, pre-study spectacle wear, and pre-study treatment for IXT. Difference in mean near control (overminus – observation) and 95% confidence intervals from ANCOVA model adjusting for baseline near control, pre-study spectacle wear, and pre-study treatment for IXT. P values for one-sided treatment group comparisons = 0.01 for distance control and 0.14 for near control.

Change is calculated as 8 weeks minus baseline so negative change = improvement. Maximum range of change possible is −5 (improvement) points to 3 points (worsening) for distance control and −4.67 (improvement) to 5 points (worsening) for near control.

Control improvement of ≥1 points between baseline and 8 weeks is the a priori definition of treatment response. P values for one-sided treatment group comparisons = 0.07 for distance control and 0.54 for near control.

Control improvement of ≥2 points is a post-hoc additional outcome of interest. P values for one-sided treatment group comparisons = 0.04 for distance control and 0.33 for near control.

Figure 1.

Baseline versus 8-week distance exotropia control for 1a) observation group subjects (N=31) and 1b) overminus group subjects (N=27). A few points have been offset very slightly (±0.1 point) to aid visibility.

In both treatment groups, the 8-week mean distance control improvement was greater in participants who had poorer distance control at baseline (Table 7). There was some suggestion that the magnitude of the treatment difference (favoring overminus treatment) was greater in participants with poorer baseline distance control (P = 0.07 for interaction).

Table 7.

Distance Exotropia Control at 8 Weeks According to Baseline Distance Control (N=58)

| 8-week Control Score (points) | Change in Control from Baseline to 8 Weeks (points)* | Treatment Response at 8 Weeks (Control Improved ≥1 Point) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Observation | Overminus | Observation | Overminus | Observation | Overminus | |||||||

| N | Mean | N | Mean | N | Mean | N | Mean | N | N (%) | N | N (%) | |

| BASELINE DISTANCE CONTROL SCORE (points) | ||||||||||||

| 2 to <3 | 13 | 2.3 | 12 | 1.7 | 13 | 0.1 | 12 | −0.5 | 13 | 3 (23) | 12 | 6 (50) |

| 3 to <4 | 7 | 2.8 | 6 | 2.5 | 7 | −0.5 | 6 | −0.7 | 7 | 4 (57) | 6 | 3 (50) |

| 4 to 5 | 11 | 3.4 | 9 | 2.0 | 11 | −1.0 | 9 | −2.5 | 11 | 5 (45) | 9 | 7 (78) |

Change is calculated as 8 weeks minus baseline so negative change = improvement. Maximum range of change possible is −5 (improvement) points to 3 points (worsening) for distance control and −4.67 (improvement) to 5 points (worsening) for near control.

PACT at near at 8 weeks was 12.8 PD in the overminus group versus 16.9 PD in the observation group (baseline adjusted difference = −4.2 PD (−7.4 to −1.1 PD)) (Table 8). The treatment groups were not different with respect to 8-week control at near, PACT at distance, or stereoacuity at near (Table 8).

Table 8.

8-Week Stereoacuity and PACT Outcomes According to Treatment Group (N=58)

| Randot Preschool Stereoacuitya | Observation (N=31) | Overminus (N=27) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N | % | N | % | |

| At 8 weeks | ||||

| 40″ to 60″ | 13 | 43 | 9 | 33 |

| 100″ to 400 | 10 | 33 | 14 | 52 |

| 800″ or nil | 7 | 23 | 4 | 15 |

| Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Mean (SD) (log arcsec)b | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.5) | ||

| Range (log arcsec) | 1.6 to 3.2 | 1.6 to 3.2 | ||

| Difference in means (95% CI)c | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | |||

| Change between baseline and 8 weeksd | ||||

| Mean (SD) (log arcsec) | 0.0 (0.4) | −0.1 (0.3) | ||

| Range (log arcsec) | −1.3 to 0.6 | −1.2 to 0.6 | ||

|

| ||||

| PACT exodeviation at distance (Δ) | ||||

| At 8 weeks | ||||

| No exodeviation (orthophoria) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–9 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 11 |

| 10–15 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 19 |

| 16–18 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 15 |

| 20–25 | 15 | 48 | 11 | 41 |

| 30–35 | 9 | 29 | 2 | 7 |

| 40–45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥50 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| Mean | 23.0 (6.3) | 21.1 (11.2) | ||

| Range | 6 to 30 | 4 to 50 | ||

| Difference in means (95% CI)e | −1.9 (−5.6 to 1.8) | |||

| Change between baseline and 8 weeksf | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −1.8 (5.4) | −3.3 (9.6) | ||

| Range | −15 to 5 | −19 to 25 | ||

|

| ||||

| PACT exodeviation at near (Δ) | ||||

| At 8 weeks | ||||

| No exodeviation (orthophoria) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| 1–9 | 6 | 19 | 5 | 19 |

| 10–15 | 4 | 13 | 9 | 33 |

| 16–18 | 6 | 19 | 3 | 11 |

| 20–25 | 12 | 39 | 6 | 22 |

| 30–35 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 |

| 40–45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Esodeviationg | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Mean (SD) | 16.9 (8.4) | 12.8 (8.3) | ||

| Range | 0 to 30 | −3 to 30 | ||

| Difference in means (95% CI)e | −4.7 (−7.7 to −1.7) | |||

| Change between baseline and 8 weeksf | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −0.6 (6.6) | −5.0 (6.9) | ||

| Range | −15 to 13 | −20 to 10 | ||

PACT – Prism and alternate cover test. SD – standard deviation. CI – confidence interval

Outcome stereoacuity is missing for 1 observation group participant because failed the pretest.

Logarc second stereoacuity values range from 1.6 logarcsec (40″) to 3.2 (nil), so lower values are better.

Difference in means (overminus – observation) and 95% CIs from ANCOVA models which adjust for baseline stereoacuity, baseline near control, pre-study spectacle wear, and pre-study treatment for IXT.

Change in stereoacuity is calculated as 8 weeks minus baseline so negative change = improvement. Change in stereoacuity is missing for 1 observation group participant who failed the pretest at baseline and 8 weeks, and 1 overminus group participant who failed the pretest at baseline.

Difference in means and 95% CIs from ANCOVA models which adjust for baseline PACT (baseline distance PACT for the distance PACT outcome; baseline near PACT for the near PACT outcome) baseline near control, pre-study spectacle wear, and pre-study treatment for IXT.

Change is PACT is calculated as 8 weeks minus baseline so negative change = improvement.

One participant in the overminus group had the deviation at near change from 12 PD exodeviation at baseline to 3 PD esodeviation at 8 weeks. During the same period, exodeviation at distance for this participant changed from 20 PD to 12 PD and stereoacuity at near changed from 100 arcsec to 60 arcsec.

Safety and Tolerability

Regarding possible adverse effects of treatment, one child in the overminus group developed an esodeviation of 3 prism diopters at near (whether it was esophoria or esotropia was not recorded), although this child had no reduction in stereoacuity from baseline (Table 9, online only). Two participants in the observation group and two participants in the overminus group had reduced monocular distance VA of 2 or more lines in one eye at 8 weeks and one participant in the observation group had reduced binocular near VA of two lines at 8 weeks. (Table 9, online only). Parent-reported symptoms were infrequent and appeared similar between treatment groups (Tables 3a – online only) and spectacle-related issues did not appear to occur more frequently in the 27 overminus group participants compared with the 10 observation group participants who were prescribed spectacles (Table 3b – online only).

Discussion

We evaluated the short-term effectiveness of overminus spectacles (−2.50D over the cycloplegic refraction) compared with observation (usual spectacle correction, if needed) for improving distance exotropia control in children 3 to 6 years of age with IXT. The mean distance exotropia control score 8 weeks after randomization was better in the overminus group than in the observation group (2.0 vs 2.8 points) and 21% more of the overminus group than in the observation group showed treatment response, defined as 1 point or more improvement in distance control (59% vs 39%, albeit not statistically significant).

We are not aware of any prospective randomized clinical trial that has compared overminus spectacles with observation in children with IXT. A treatment effect of overminus lens therapy for IXT has been reported in several retrospective studies without comparison groups.10, 12–19 In these previous studies, the amount of overminus prescribed ranged from 0.50D to 5.00D. The two most common prescribing approaches were 1) to prescribe a fixed amount of overminus based on refractive error and/or age10, 12, 15 and 2) to select an initial amount of overminus and increase it incrementally until a certain level of control of IXT, was achieved.13, 14, 16 In addition, treatment duration varied within each study. These previous studies reported overminus treatment to be effective in improving control of IXT, defined as either no manifest tropia,13, 15, 16, 18 reduction in Newcastle control score,19 or presence of fusion.14 The results of our pilot study, incorporating randomization of treatment assignment, standardization of visit timing, and masking of outcome assessment, also support the finding of improved control of IXT with overminus lens treatment at 8 weeks.

In our pilot randomized clinical trial, we chose 2.50D as the amount of overminus because it allowed the final power of the spectacles to be at least −1.50D SE, while maintaining a constant accommodative demand in all participants regardless of their underlying cycloplegic refractive error. Overall, participants showed good compliance and tolerance of this dose of overminus, based on parental report. The side effects of headaches, blur, eye strain, and avoidance of near work appeared to be similar between the overminus and observation groups, which suggest that the dosage of 2.50D overminus was well tolerated.

We performed secondary analyses to assess effectiveness of overminus based on the level of baseline distance control. Interestingly, children with poorer baseline mean distance control scores showed more improvement in their distance control than children with better mean distance control. Although this greater response in children with poor baseline control may be partly due to regression to the mean and having more room for improvement, the same magnitude of response was not seen in the observation group, suggesting that this greater effect of overminus treatment on children with poorer control may be real. Nevertheless, this preliminary observation suggesting greater effectiveness of overminus treatment for very poorly controlled IXT needs to be interpreted with caution because of the small sample sizes in subgroups.

Our study has limitations. By design, our current study was a pilot randomized clinical trial with a small sample size and only 8-weeks of follow-up. We do not know if the treatment effect would persist after overminus lenses are replaced with usual spectacle correction. Our estimates of improved control with overminus treatment may be overestimates, given the high test-retest variability of control (due in part to inherent variability of the condition), combined with a distance control score eligibility requirement of 2 points or worse (expected to have resulted in some improvement due solely to regression to the mean).21, 22, 25 Nevertheless, we would expect these factors would affect the randomized groups equally and therefore would not influence our primary finding that overminus treatment improved distance control compared with observation. Our study has a number of strengths over previous retrospective reviews and case series. First, we incorporated randomization of treatment assignment. Second, all 58 participants returned for 8-week follow up. In addition, participants were evaluated using standardized measures by certified examiners who were masked to treatment assignment by having all participants wear glasses for the outcome exam; including plano spectacles for testing children in the observation group who did not wear refractive correction.

In conclusion, in this pilot randomized trial we found that overminus spectacles improved distance control at 8 weeks in children 3 to 6 years old with IXT. A larger and longer randomized treatment trial is warranted to assess the effectiveness of overminus spectacles, as well as determining whether there is a lasting effect on control of IXT after overminus treatment has been discontinued.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Supported by National Eye Institute of National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services EY011751, EY023198, and EY018810. The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

This study was supported by the National Eye Institute of National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services EY011751, EY023198, and EY018810. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Appendix 1

Clinical Sites

Sites are listed in order by number of participants enrolled. Personnel are listed as (I) for Investigator, (C) for Coordinator, or (E) for Examiner.

Fullerton, CA - Southern California College of Optometry (8)

Susan A. Cotter (I); Raymond H. Chu (I); Silvia Han (I); Catherine L Heyman (I); Reena A Patel (I); Amy E Aldrich (I); Sue M. Parker (C); Angela M. Chen (E); Kristine Huang (E)

Miami, FL - Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (6)

Susanna M. Tamkins (I); Carolina Manchola-Orozco (C); Kara M. Cavuoto (E)

Baltimore, MD - Greater Baltimore Medical Center (4)

Mary Louise Z. Collins (I); Allison A. Jensen (I); Maureen A. Flanagan (C); Saman Bhatti (E); Cheryl L. McCarus (E); Srianna Narain (E)

Chicago, IL - Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago (4)

Bahram Rahmani (I); Sudhi P Kurup (I); Magdalena Stec (I); Hawke H Yoon (I); Marilyn B. Mets (I); Rebecca B. Mets-Halgrimson (I); Hantamalala X Ralay Ranaivo (C); Kristyn M Magwire (E); Vivian Tzanetakos (E); Erika A. Talip (E)

Cincinnati, OH - Cincinnati Children’s Hospital (4)

Michael E. Gray (I); Corey Suzanne Bowman (C); Shemeka Rochelle Forte (E)

Calgary, Canada - Alberta Children’s Hospital (3)

William F. Astle (I); Emi Nicole Sanders (C); Zuzana X Ecerova (E); Charlene Dawn Gillis (E); Shannon L Steeves (E)

Chicago Ridge, IL - The Eye Specialists Center, L.L.C. (3)

Benjamin H. Ticho (I); Megan Allen (I); Birva K Shah (I); Deborah A. Clausius (C)

Concord, NH - Concord Eye Center (3)

Christie L. Morse (I); Maynard B. Wheeler (I); Melanie L. Christian (C); Caroline C. Fang (E)

Houston, TX - Texas Children’s Hospital - Dpt. Of Ophthalmology (3)

Evelyn A. Paysse (I); Amit R Bhatt (I); David K. Coats (I); Lingkun X Kong (C)

New York, NY - State University of New York, College of Optometry (3)

Marilyn Vricella (I); Robert H. Duckman (I); Valerie Leung (C); Erica L Schulman-Ellis (E)

Norfolk, VA - Virginia Pediatric Eye Center (3)

Eric Crouch (I); Earl R. Crouch, Jr. (I); Gaylord G. Ventura (C)

Poland, OH - Eye Care Associates, Inc. (3)

S. Ayse Erzurum (I); Beth J Colon (C); Zainab Dinani (E)

Omaha, NE - University of Nebraska Medical Center (2)

Donny W Suh (I); Carolyn X Chamberlain (C); Dimitra M Triantafilou (E)

The Woodlands, TX - Houston Eye Associates (2)

Aaron M. Miller (I); Jorie L. Jackson (C); Kathleen Mary Curtin (E)

Durham, NC - Duke University Eye Center (1)

Laura B. Enyedi (I); David K. Wallace (I); Sarah K. Jones (C); Namita Kashyap (E)

Erie, PA - Pediatric Ophthalmology of Erie (1)

Nicholas A. Sala (I); Allyson Sala (C); V. Lori Zeto (E)

Ft. Lauderdale, FL - Nova Southeastern University College of Optometry, The Eye Institute (1)

Nadine M. Girgis (I); Erin C. Jenewein (I); Yin C. Tea (I); Surbhi X Bansal (C)

Kansas City, MO - Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics (1)

Amy L. Waters (I); Christina M. Twardowski (I); Rebecca J. Dent (C); Cindy J. Cline (E)

Lancaster, PA - Family Eye Group (1)

David I. Silbert (I); Noelle S. Matta (C)

Salt Lake City, UT - Rocky Mountain Eye Care Associates (1)

David B. Petersen (I); Beth A Morrell (C); Tori S Pickens (C); J. Ryan McMurtrey (E)

Wilmette, IL - Pediatric Eye Associates (1)

Lisa C. Verderber (I); Deborah R. Fishman (I); Roberta A Forde (C)

PEDIG Coordinating Center - Tampa, FL

Raymond T. Kraker, Roy W. Beck, Darrell S. Austin, Nicole M. Boyle, Courtney L. Conner, Danielle L. Chandler, Trevano W. Dean, Quayleen Donahue, Brooke P. Fimbel, Graham M. Hardt, James E. Hoepner, Joseph D. Kaplon, Elizabeth L. Lazar, B. Michele Melia, Gillaine Ortiz, Diana E. Rojas, Jennifer A. Shah, Rui Wu.

IXT3 Planning Committee

Angela M. Chen (co-chair), Jonathan M. Holmes (co-chair), Darron A. Bacal, Roy W. Beck, Eileen B. Birch, Danielle L. Chandler, Alex X. Christoff, Susan A. Cotter, Sarah R. Hatt, Raymond T. Kraker, David A. Leske, Richard London, B. Michele Melia, Aaron M. Miller, Evelyn A. Paysse, Michael X. Repka, David K. Wallace.

National Eye Institute - Bethesda, MD

Donald F. Everett

PEDIG Executive Committee

David K. Wallace (chair), William F. Astle (2013–2015), Roy W. Beck, Eileen E. Birch, Susan A. Cotter (2011–2014, 2015-present), Eric R. Crouch III (2014–2015), Laura B. Enyedi (2014-present), Donald F. Everett, Jonathan M. Holmes, Raymond T. Kraker, Scott R. Lambert (2013–2015), Katherine A. Lee (2014-present), Ruth E. Manny (2013-present), Michael X. Repka, Jayne L. Silver (2014-present), Katherine K. Weise (2014-present), Lisa C. Verderber (2015-present).

Strabismus Study Steering Committee

Eileen E. Birch, Danielle L. Chandler, Angela M. Chen, Stephen P. Christiansen (2013–2015), Susan A. Cotter, Eric R. Crouch III, Trevano W. Dean, Sean P. Donahue, Sarah R. Hatt, Jonathan M. Holmes, Darren L. Hoover (2010–2014), Raymond T. Kraker, Elizabeth L. Lazar, Ingryd J. Lorenzana (2014–2015), B. Michele Melia, Brian G. Mohney, Karen Pollack (2014–2015), Mitchell M. Scheiman (2010–2014), Rosanne Superstein (2013–2014), Susanna M. Tamkins (2009–2014), David K. Wallace, Tomohiko Yamada (2014-present)

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

Marie Diener-West (chair), John D. Baker, Barry Davis, Donald F. Everett, Dale L. Phelps, Stephen W. Poff, Richard A. Saunders, Lawrence Tychsen

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation: Content from this manuscript was presented at the annual American Academy of Optometry meeting (October 2015 in New Orleans, LA)

Conflict of Interest: No conflicting relationships exist for any author.

An address for reprints will not be provided.

This article contains online-only material. The following should appear online-only: Table 2, Table 3a, Table 3b, Table 9.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Govindan M, Mohney BG, Diehl NN, Burke JP. Incidence and types of childhood exotropia: A population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(1):104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in white and African American children aged 6 through 71 months: The Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Multi-ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in African American and Hispanic children ages 6 to 72 months the multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKean-Cowdin R, Cotter SA, Tarczy-Hornoch K, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia or strabismus in asian and non-Hispanic white preschool children: multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):2117–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffey B, Wick B, Cotter S, et al. Treatment options in intermittent exotropia: a critical appraisal. Optom Vis Sci. 1992;69(5):386–404. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper J, Medow N. Intermittent exotropia, basic and divergence excess type. Binocul Vis Strabismus Q. 1993;8(3):187–216. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial comparing part-time patching with observation for children 3–10 years of age with intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(12):2299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatt S, Gnanaraj L. Interventions for intermittent exotropia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;3:CD003737. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003737.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romano PE, Wilson MF. Survey of current management of intermittent exotropia in the USA and Canada. In: Campos EC, editor. Strabismus and Ocular Motility Disorders. London: The Macmillan Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds JD, Wackerhagen M, Olitsky SE. Overminus lens therapy for intermittent exotropia. Am Orthopt J. 1994;44:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horwood AM, Riddell PM. Evidence that convergence rather than accommodation controls intermittent distance exotropia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(2):e109–e17. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushner BJ. Does overcorrecting minus lens therapy for intermittent exotropia cause myopia? Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(5):638–42. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowe FJ, Noonan CP, Freeman G, DeBell J. Intervention for intermittent distance exotropia with overcorrecting minus lenses. Eye. 2009;23(2):320–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6703057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy JR. The correction of divergent strabismus with concave lenses. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom. 1954;31:605–14. doi: 10.1097/00006324-195412000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caltrider N, Jampolsky A. Overcorrecting minus lens therapy for treatment of intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:1160–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodacre H. Minus overcorrection: conservative treatment of intermittent exotropia in the young child--a comparative study. Australian Orthoptic Journal. 1985;22:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutstein RP, Marsh-Tootle W, London R. Changes in refractive error for exotropes treated with overminus lenses. Optom Vis Sci. 1989;66(8):487–91. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donaldson PJ, Kemp EG. An initial study of the treatment of intermittent exotropia by minus overcorrection. Br Orthopt J. 1991;48:41–3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watts P, Tippings E, Al-Madfai H. Intermittent exotropia, overcorrecting minus lenses, and the Newcastle scoring system. J AAPOS. 2005;9(5):460–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohney BG, Holmes JM. An office-based scale for assessing control in intermittent exotropia. Strabismus. 2006;14(3):147–50. doi: 10.1080/09273970600894716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatt SR, Liebermann L, Leske DA, et al. Improved assessment of control in intermittent exotropia using multiple measures. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(5):872–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatt S, Leske D, Liebermann L, Holmes J. Quantifying variability in the measurement of control in intermittent exotropia. J AAPOS. 2015;19:33–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes JM, Beck RW, Repka MX, et al. The Amblyopia Treatment Study visual acuity testing protocol. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(9):1345–53. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.9.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moke PS, Turpin AH, Beck RW, et al. Computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the amblyopia treatment study visual acuity testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(6):903–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatt S, Mohney B, Leske D, Holmes J. Variability of control in intermittent exotropia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;115:371–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.