Abstract

Background

Previous studies identified common variants at the ABO and VWF loci and unknown variants in a chromosome 2q12 linkage interval that contributed to the variation of plasma von Willebrand factor levels (VWF). While the association with ABO haplotypes can be explained by differential VWF clearance, little is known about the mechanisms underlying the association with VWF SNPs or with variants in the chromosome 2 linkage interval. VWF propeptide (VWFpp) and mature VWF are synthesized from the VWF gene and secreted at the same rate but have different plasma half-lives. Therefore, comparison of VWFpp and VWF association signals can be used to assess if the variants are primarily affecting synthesis/secretion or clearance.

Methods

We measured plasma VWFpp levels and performed genome-wide linkage and association studies in 3,238 young and healthy individuals for whom VWF levels have been analyzed previously.

Results and conclusions

Common variants in an intergenic region on 7q11 were associated with VWFpp. We demonstrate ABO serotype specific SNPs were associated with VWFpp levels in the same direction as VWF but with a much lower effect size. Neither the association at VWF nor the linkage on chromosome 2 previously reported for VWF was observed for VWFpp. Taken together, these results suggest that the major genetic factors affecting plasma VWF levels: variants at ABO, VWF and a locus on chromosome 2, operate primarily through their effects on VWF clearance.

Keywords: von Willebrand factor, von Willebrand disease, venous thromboembolism, genome-wide association study, genetic linkage analysis

Introduction

Plasma von Willebrand factor (VWF) levels vary approximately five fold among healthy individuals and are highly heritable.[1-5] Individuals with VWF levels at the extremes of the normal distribution are at risk for common disorders of hemostasis: low levels cause the common bleeding disorder Type I von Willebrand disease (VWD); and high levels are associated with an increased risk for both venous and arterial thrombosis.[6, 7] Therefore, identification of the genetic factors affecting VWF levels may lead to improved, personalized care for patients with VWD, arterial thrombosis and venous thromboembolic disease.[8]

Previous genome-wide association studies (GWAS) demonstrated that common variants at ABO, VWF and other loci explained ~12% of the variance in plasma VWF levels.[9] More recently, we reported genome-wide linkage and association analyses of plasma VWF levels in a cohort of young healthy individuals,[3] confirming the association between ABO A1 and B alleles with elevated VWF levels relative to the O and A2 alleles. At VWF, haplotypes containing common variants near the factor VIII binding (D’ domain) and propeptide coding regions (D1 and D2 domains) were also significantly associated with VWF levels.[3, 10] Using the sibling structure in our cohorts we preformed linkage analysis and identified an interval on chromosome (Chr) 2q12 explaining ~19% of the variation in VWF levels.[3] Although the effect may not be direct, [11] the major allelic variants at ABO influence VWF levels through altered VWF clearance[12-14], while basic mechanisms underlying the effect of the variants in VWF and in 2q12 remain unknown.

A specialized post-translational modification system facilitates the storage and secretion of VWF multimers.[15] The VWF propeptide (VWFpp) is cleaved from pro-VWF dimers but remains non-covalently bound to the developing VWF multimers until both are secreted into flowing blood. VWFpp is rapidly cleared from circulation with a half-life of 2-3 hours, whereas multimeric VWF has a longer half-life of 8-12 hours.[16] Since alterations in VWF synthesis or secretion would be expected to affect VWF and VWFpp levels similarly, relative differences in the steady state levels of these two proteins in plasma should reflect differences in their clearance rates. For this reason, elevation in the ratio of VWFpp to VWF has been used to differentiate the subset of individuals with von Willebrand disease due to rapid clearance of VWF from those with reduced synthesis or secretion.[17, 18]

To identify genetic variants affecting plasma VWFpp concentrations and to determine if SNPs previously associated with VWF variation operate primarily through altered synthesis/secretion or clearance mechanisms, we measured VWFpp levels in plasma samples from the Genes and Blood Clotting Study (GABC) and the Trinity Student Study (TSS) where VWF levels had already been measured and their association results reported.[3] Using an initial measure of VWFpp in the GABC cohort we identified a strong association with a non-synonymous SNP in the VWFpp coding portion of VWF. However, this association was not present when a different set of monoclonal antibodies were used to determine VWFpp concentrations, suggesting an altered epitope due to this SNP has generated the apparent association. We therefore only used VWFpp assay results without interference from this altered epitope in association and linkage studies, and identified significant associations with VWFpp and variants at ABO and a new locus on chromosome 7. Comparison of these results with our previously reported VWF studies[3] suggest that variants at VWF and the Chr 2 linkage interval modify VWF concentrations mainly through clearance mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Genes and Blood Clotting Study (GABC)

1,189 healthy siblings between the ages of 14 and 35 years were recruited from the students and staff at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor between 6/2006 and 1/2009.[3, 19] Subjects who reported that they were pregnant or had a known bleeding disorder or chronic illness requiring regular medical care were excluded. All subjects gave informed consent prior to their participation.[20]

The Trinity Student Study (TSS)

Healthy Irish individuals aged 18-28 years, attending Trinity College of the University of Dublin, were recruited between 2003-2004 for genetic analysis of nutrition and diet related traits. A total of 2,490 participants completed questionnaires and donated blood samples. Ethical approval from the Dublin Federated Hospitals Research Ethics Committee was obtained and reviewed by the Office of Human Subjects Research at the United States National Institute of Health. Participants provided written informed consent prior to recruitment.

Plasma VWFpp Levels

VWFpp levels were measured in the GABC and TSS cohorts with AlphaLISA (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA).[3] To create VWFpp specific AlphaLISA assays, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were produced in the Blood Center of Wisconsin Hybridoma Core Lab (Milwaukee, WI) by immunizing mice with purified recombinant human. mAbs were purified from ascites and epitope mapping was performed using standard enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assays (ELISA) with truncated fragments of recombinant VWFpp as targets (Figure S1). For TSS plasma samples, which were collected using EDTA as an anticoagulant, 0.8mM CaCl2 was added to the assay buffer to correct for signal loss associated with the presence of EDTA (Figure S2).

VWFpp levels were calculated assuming a 1:1 ratio of VWF to VWFpp in laboratory control plasma from pooled donors (FACT, George King Bio-medical, Overland Park, KS). Each sample was independently assayed at least 4 times. The mean sample coefficient of variation was 1.0% (GABC, anti-D2), 1.1% (GABC, anti-D1) and 2.8% (TSS, anti-D1). After quality control, 3,381 subjects (1,110 GABC, 2,271 TSS) had VWFpp levels available for heritability analysis and 3,238 for association and linkage testing.

Phenotype Data Processing

The raw VWFpp distribution was normalized by log transformation and adjusted for the effects of age, gender and population genetic structure. We evaluated the correlation between each of the first 10 principal component (PC) scores and the age- and gender-corrected VWFpp levels for GABC and TSS separately, and used the Pearson's correlation coefficients and p-values to determine which PCs have a significant impact (p < 0.05) on the phenotype. After analyzing the Pearson's correlation coefficients, p-values and GC factors, we selected the principal component(s) that were highly correlated with the two traits and resulted in the lowest GC factors. For use in GWAS and linkage studies, log transformed VWFpp levels were adjusted for age, gender and the selected principal component(s): PC2 and PC7 for GABC, and PC4 for TSS.

Genotyping, Imputation and Quality Control

GABC

Details of the genotyping and data-cleaning process have been previously published.[3, 20],[21] The final cleaned dataset contained 763,195 SNPs and 1,152 subjects representing 489 sibships. Imputation was carried out by the GENEVA Consortium Data Coordinating Center using BEAGLE v3.3.1 [22] on a set of 767,243 genotyped SNPs. The final dataset included ~ 7.50 million SNPs. We then removed SNPs with low imputation quality (R-squared <0.3) and low allele frequency (MAF <2%), resulting in ~ 5.95 million SNPs.

TSS

After extensive cleaning, the final dataset contained 757,577 SNPs. For imputation, we first pre-phased the cleaned dataset using SHAPEIT2 v2.r778[23], and used IMPUTE2 v2.3.0[24] and the 1000 Genomes Phase I release v3 integrated haplotypes (produced using SHAPEIT2 in December 2013) for imputation. This generated 10,520,121 imputed SNPs. After removing the SNPs with low imputation quality (R-squared<0.3), low allele frequency (MAF<2%), low call rate (<95%) and failing the test of Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (P < 1.0 × 10−6), the final dataset contained ~7.37 million SNPs in 2,304 individuals.

The TSS and GABC imputed datasets had ~ 4.51 million SNPs in common; and this set was used for the meta-analyses. The genome-wide significance level was set at P = 5.0 × 10−8 based on a conservative Bonferroni correction for ~1 million independent tests.

Genetic Analyses

Population Substructure

Due to the presence of sibships of varying size, GABC samples were analyzed using a two-step approach[25] as detailed previously.[3, 19]

Association analyses

For the GABC cohort, we performed single-SNP association analysis of the transformed and adjusted VWFpp antigen levels using the imputed set of ~ 5.95 million SNPs. To account for the inferred relatedness and subtle population stratification, we applied a mixed linear model implemented in EMMAX[26]. For the TSS cohort, we performed single-SNP association tests on the set of ~7.37 million imputed SNPs using PLINK (v1.07)[27], assuming an additive mode of allelic effect. For both cohorts, we calculated the genomic control factor[28] to assess the degree of residual stratification.

Meta-analysis

We performed a meta-analysis of GABC and TSS association results using a sample-size-weighted approach on the common set of ~ 4.51 million imputed SNPs using METAL[29]. The genomic control factor was near 1 for both analyses: 0.972 and 1.013 for GABC (EMMAX) and TSS (PLINK), respectively, and the association statistics were corrected to reach a genomic control factor of 1.000 by METAL before being used in the meta-analysis. Regional plots of the significant findings were produced using LocusZoom.[30]

Detection of an antibody-specific SNP association with VWFpp

VWFpp levels were initially determined by using a pair of monoclonal anti-VWFpp D2 domain antibodies (Figure S1). In the European subset (n=934) of GABC, a single SNP, rs1800378(T), with a minor allele frequency of 33% in our cohort, was associated with VWFpp (P = 1.15 × 10−12, β = 0.051 IU/dL per allele in an additive model) (Figure S3A-C). This SNP encodes a histidine to arginine substitution at position 484 in the D2 domain of VWFpp, and is predicted by PolyPhen-2[31] to be a benign variant. It was not significantly associated with plasma VWF levels (P = 0.52). We repeated the VWFpp measurement using a second pair of anti-VWFpp D1 domain antibodies (Figure S1). Although the log transformed VWFpp levels measured with the anti-D2 domain antibodies were highly correlated with those with the anti-D1 domain antibodies (Spearman's ρ = 0.97, P < 0.0001), VWFpp levels measured with the anti-D1 domain antibodies did not produce a significant signal at rs1800378 (P = 0.061, Figure S3D-E), suggesting that VWFpp bearing this coding change has an altered affinity to the anti-D2 domain antibody pair. We used VWFpp levels determined by the anti-D1 domain in subsequent association and linkage analyses.

Linkage Analysis

Linkage analysis was carried out using MERLIN-REGRESS[32] on the European sibling subset of GABC and sibling subset of TSS (n=138). We employed a clustering algorithm, and a permutation-based locus-counting approach to calculate empiric P values for the top linkage signals as previously described.[3] Starting with the MERLIN-REGRESS output, the subsequent analysis was carried out using custom scripts in R.[33]

Heritability Analysis

For the combined sibling subset of TSS and 1,139 GABC individuals (557 sibships), we used two pedigree-based methods for estimating heritability, intraclass correlation and MERLIN-REGRESS (v1.1.2) as previously described.[3, 19, 32]

Variance-Explained by Association and Linkage Regions

The Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) package[34] was used to estimate the proportion of variance in VWFpp levels explained by the entire genome, the top associated SNPs, or intervals representing individual genes or loci as previously described.[3, 19]

Haplotype-based Association Analysis

PLINK[27] was used to carry out haplotype association using the one degree-of-freedom haplotype-specific test. ABO serotypes (A1, A2, O, B) were tagged by the three SNPs: rs687289, rs8176704 and rs8176749 as reported by Barbalic et al.[35]

Results

VWFpp levels are highly heritable

Details of the demographic characteristics of the TSS and GABC cohorts are shown in Table 1. There were differences in the distribution of unadjusted VWFpp (Figure S4A) between the GABC and TSS cohorts (K-S test, P = 0.0001) with a median VWFpp of 100.0 IU/dL in GABC and 86.1 IU/dL in TSS (Table 1). These differences may have been due to sample collection in acid citrate dextrose for GABC versus in EDTA for TSS that were not adequately corrected by additions of CaCl2 to the assay buffer (see Methods). However, when the VWFpp values were log transformed, mean centered within each cohort, adjusted for age, sex and the population structure, this removed the distribution differences between GABC and TSS (Figure S4B). Based on interclass correlation among the siblings in the GABC and TSS cohorts, the narrow-sense heritability of VWFpp was 77.6%, consistent with the value of 80.4% obtained with MERLIN REGRESS. These heritability estimates are similar to those we reported for VWF, 64.5% and 66.3%, using interclass correlation and MERLIN REGRESS, respectively.[3] There was a significant positive correlation between the adjusted VWFpp and VWF, with Spearman's rank correlations (ρ) of 0.52 for the GABC cohort (P <0.0001) and 0.53 (P <0.0001) for the TSS cohort, respectively (Figure S5A-B).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Cohort | *GABC | TSS |

|---|---|---|

| Subject counts, n | 1,152 | 2,304 |

| Age, years (Q1,Q3) | 21 (19, 23) | 22 (21,24) |

| Female, n (%) | 721 (63) | 1352 (59) |

| Sibship Size (n sibships) | 1 (13); 2 (366); 3 (94); 4 (22); 5 (5); 6 (2) | 2(66); 3(2) |

| median VWF, IU/dL (Q1,Q3) | 100.2 (77.5, 130.7) | 99.8 (79.6, 128.1) |

| median VWFpp, IU/dL (Q1,Q3) | 100.0 (82.2,122.1) | 86.1 (71.8, 104.6) |

Data from previous VWF analysis[3], except for VWFpp concentration.

Common variants at ABO and 7q11 are associated with VWFpp levels

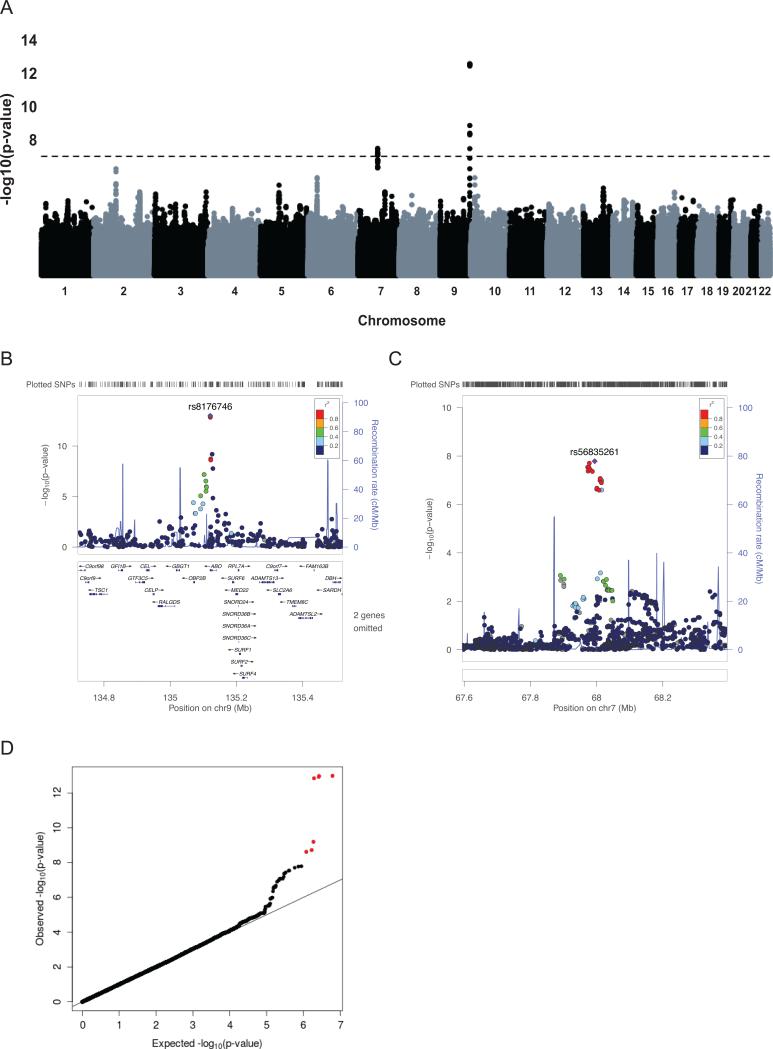

VWFpp association results for the GABC and TSS cohorts (Figure S3D and Figure S6A, respectively) were combined in meta-analysis using a common set of ~ 4.51 million genotyped and imputed SNPs. Two regions with significant associations were identified (Table 2). First, eight SNPs on Chr 9q34 at the ABO locus demonstrated significant associations (Figure 1A-B, D) with the top SNP, rs8176746 (P = 1.1 × 10−13), encoding a L266M substitution in ABO and tagging the common ABO B allele. All SNPs at the ABO locus (N=28) explained 7.40% of the variation in the adjusted VWFpp levels compared to 19.6% of the variation in the adjusted VWF levels (Table 3). Second, seven associated SNPs were identified on Chr 7q11.22 in an intergenic region, top SNP: rs56835261 (P = 1.6 × 10−8) (Figure 1C). Taken together, the 15 significant SNPs at these two loci explained 3.50% of the variation in the adjusted VWFpp levels (Table 3). A heterogeneity analysis of these top SNPs showed no significant difference across the two cohorts (all with I2 = 0 %, P > 0.05). When a conditional analysis using the top meta-analysis SNP, rs8176746, was performed, no new signal arose at the ABO locus or elsewhere, and the signal at Chr 7q11, rs56835261, was reduced to just below the threshold for significance (P = 5.5 × 10−8).

Table 2. Top 22 imputed meta-analysis SNPs for VWFpp.

Genome-wide significant (p-value < 5.0E-8) SNPs in GABC (EMMAX) + TSS (Plink) meta-analysis and individual cohorts, sorted by genomic location, with respect to their relationship to the nearest gene.

| *Meta-Analysis | GABC | TSS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Chr | Position† | SNP Allele | P-Value | Closest Gene | Allele Freq. | Beta (SE) | P-Value | Allele Freq. | Beta (SE) | P-Value |

| rs10251762 | 7 | 68335032 | T | 2.9E-08 | AUTS2 | 0.078 | 0.034 (0.011) | 2.9E-03 | 0.065 | 0.034 (0.0072) | 2.4E-06 |

| rs12531236 | 7 | 68336435 | T | 4.2E-08 | AUTS2 | 0.081 | 0.034 (0.010) | 1.6E-03 | 0.062 | 0.031 (0.0068) | 6.3E-06 |

| rs10246260 | 7 | 68338971 | A | 2.9E-08 | AUTS2 | 0.078 | 0.034 (0.011) | 2.9E-03 | 0.065 | 0.034 (0.0072) | 2.4E-06 |

| rs55800567 | 7 | 68340079 | A | 2.0E-08 | AUTS2 | 0.079 | 0.035 (0.011) | 2.0E-03 | 0.060 | 0.034 (0.0072) | 2.4E-06 |

| rs10252976 | 7 | 68343237 | T | 3.7E-08 | AUTS2 | 0.92 | −0.033 (0.011) | 3.9E-03 | 0.93 | −0.034 (0.0072) | 2.4E-06 |

| rs11977562 | 7 | 68349402 | A | 4.3E-08 | AUTS2 | 0.92 | −0.033 (0.011) | 3.9E-03 | 0.94 | −0.034 (0.0072) | 2.8E-06 |

| rs56835261 | 7 | 68356258 | A | 1.6E-08 | AUTS2 | 0.92 | −0.035 (0.011) | 2.1E-03 | 0.93 | −0.034 (0.0072) | 1.9E-06 |

| rs8176749 | 9 | 136131188 | A | 1.1E-13 | ABO | 0.070 | 0.052 (0.012) | 2.0E-05 | 0.073 | 0.040 (0.0066) | 8.5E-10 |

| rs8176746 | 9 | 136131322 | A | 1.0E-13 | ABO | 0.070 | 0.052 (0.012) | 2.0E-05 | 0.073 | 0.040 (0.0066) | 8.3E-10 |

| rs8176743 | 9 | 136131415 | A | 1.2E-13 | ABO | 0.070 | 0.052 (0.012) | 2.0E-05 | 0.073 | 0.040 (0.0065) | 9.5E-10 |

| rs8176741 | 9 | 136131461 | T | 1.4E-13 | ABO | 0.070 | 0.052 (0.012) | 2.0E-05 | 0.073 | 0.040 (0.0066) | 1.1E-09 |

| rs8176725 | 9 | 136132617 | T | 1.9E-09 | ABO | 0.093 | 0.042 (0.010) | 5.7E-05 | 0.099 | 0.026 (0.0057) | 4.5E-06 |

| rs8176722 | 9 | 136132754 | T | 2.4E-09 | ABO | 0.093 | 0.042 (0.010) | 7.0E-05 | 0.099 | 0.026 (0.0057) | 4.8E-06 |

| rs687289 | 9 | 136137106 | T | 6.4E-10 | ABO | 0.36 | 0.023 (0.0065) | 2.7E-04 | 0.25 | 0.020 (0.0039) | 4.7E-07 |

| rs657152 | 9 | 136139265 | T | 1.7E-08 | ABO | 0.38 | 0.023 (0.0062) | 1.7E-04 | 0.28 | 0.016 (0.0038) | 1.5E-05 |

In the combined set of 934 individuals in the GABC and 2,304 individuals in the TSS cohort

Coordinates are in NCBI36/hg18

Chr: Chromosome

Beta values based on log transformed, adjusted VWFpp values.

SE: Standard error

Figure 1. VWFpp Meta-analysis results.

(A) Genome-wide plot of −log10(P) for ~4.51 million SNPs. The dotted line marks the 1.10 × 10−8 threshold of genome-wide significance. (B) Regional plot for the associated region on Chr 9q34. (C) Regional plot for the associated region on Chr 7q11.22. (D) Quantile-quantile plot of observed vs. expected −log10(P) for VWF meta-analysis. The observed −log10(P) > 7.96 are shown in red.

Table 3.

Variance of adjusted VWFpp levels calculated by GCTA and explained by combined GABC and TSS cohorts with imputed SNPs (n= 3,238)

| Region | VWF | VWFpp |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-wide (All SNPs) | 62.6 | 56.2 |

| All Significant SNPs* | 21.1 | 3.50 |

| ABO†(28 SNPs) | 19.6 | 7.40 |

| VWF†(415 SNPs) | 2.87 | 1.90 |

Results from meta-analysis, VWFpp (22 SNPs), VWF (129 SNPS)

All SNPs tested in the gene region

ABO haplotypes are associated with VWFpp levels, but less strongly than with VWF

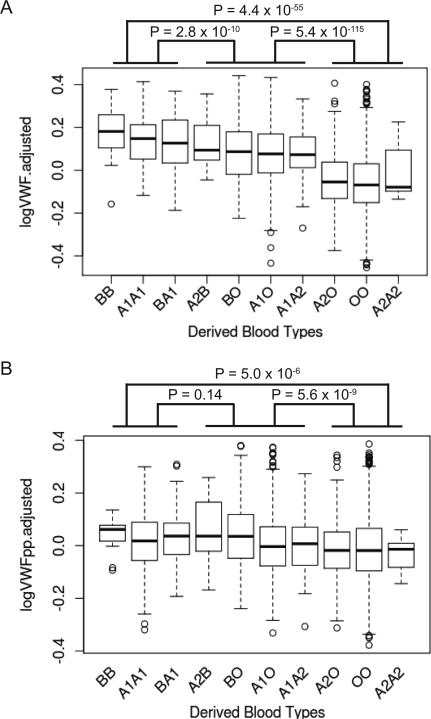

Twenty-eight SNPs at the ABO locus explained 7.40% of the variance of VWFpp compared to 19.6% of the variance of VWF (Table 3).[3] A1, B, O and A2 tagging haplotypes had the same direction of effect in both VWFpp and VWF associations, but the effect sizes were weaker in VWFpp than VWF (Table 4). The difference in effect size of the ABO haplotype on VWF compared to VWFpp is evident when the adjusted VWF and VWFpp levels are plotted according to ABO haplotypes predicted by three ABO SNPs[35] (Figure 2). There were significant differences in the VWF levels between the homozygous low group (A2/O, O/O, A2/A2) and the homozygous high group (B/B, A1/A1, B/A1) (t-test P = 4.4 × 10−55) as well as the homozygous high group and the heterozygous high/low group (A2/B, B/O, A1/O, A1/A2) (t-test P = 2.8 × 10−10) (Figure 2A). For VWFpp levels, significant differences existed between the homozygous low group and the homozygous high group (t-test P = 5.0 × 10−6), and the heterozygous high/low group and the homozygous low group (t-test P = 5.6 × 10−9), but not between the homozygous high group and the heterozygous high/low group (t-test P = 0.14) (Figure 2B).

Table 4.

ABO haplotype association results for VWF and VWFpp

| VWF | VWFpp | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Haplotype* | Allele Freq. | Beta | P value | Beta | P value |

| O | GGC | 0.72 | −0.100 | 4.1E-136 | −0.019 | 5.5E-9 |

| A1 | AGC | 0.16 | 0.110 | 1.6E-100 | 0.010 | 1.1E-2 |

| B | AGT | 0.072 | 0.110 | 1.4E-47 | 0.043 | 1.2E-13 |

| A2 | AAC | 0.053 | −0.017 | 0.045 | −0.005 | 4.2E-2 |

Haplotypes based on rs687289, rs8176704 and rs8176749.

Figure 2. Distributions of log transformed and covariate adjusted VWF and VWFpp levels in the combined GABC and TSS cohorts (N=3,238) grouped by SNP derived ABO haplotype groups.

P-values show the comparisons between the homozygous high (BB, A1A1, BA1), heterozygous high/low (A2B, BO, A1O, A1A2) and homozygous low groups (A2O, OO, A2A2) (with “high” and “low” defined by their adjusted VWF levels).

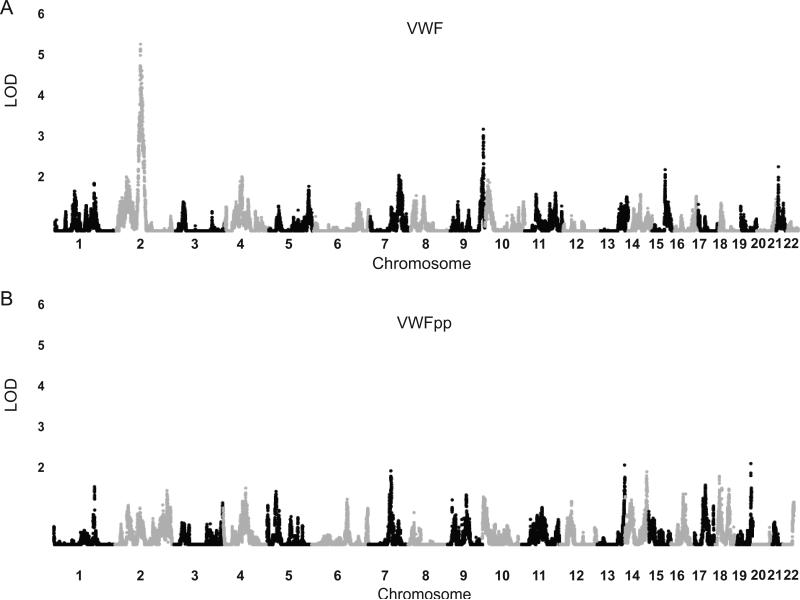

No significant linkage signal at 2q12 for VWFpp

Using the sibling subset of GABC and linkage disequilibrium-based 36,658 SNP clusters (see Supplementary Methods), we performed linkage studies to identify additional genetic factors affecting VWFpp levels. Unlike VWF, which has a significant linkage signal at Chr 2q12 and 9q34 (containing ABO)[3] (Figure 3A), VWFpp has no significant signal in the 2q12 VWF linkage interval, nor at any loci elsewhere (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Linkage analysis results in TSS and GABC sibs (n = 1,065).

Genome-wide LOD scores plotted for 36,658 “clusters”, defined in MERLIN to model independent regions of linkage. (A) Manhattan plot VWF linkage results from previously published analysis [3], (B) Manhattan plot of VWFpp linkage results.

Comparisons of association results of VWF and VWFpp suggest differential clearance mechanisms for ABO, VWF, Chr 7 regions

If a DNA variant affects the clearance process of either VWF or VWFpp, we expect it to show different association signals for VWF and VWFpp. Conversely, if a variant affects the shared synthesis or secretion processes of VWF and VWFpp, it is expected to generate a similar association effect size and direction for both VWF and VWFpp. Consistent with this expectation, rs687289 and rs8176746, tagging the O and B alleles of ABO respectively, had a strong association with VWF and much weaker association with VWFpp, suggesting that although these ABO SNPs were associated with both VWF traits, the difference in the magnitude of their effects is best explained by an unequal SNP effect on the rate of clearance from the circulation. This result agrees with the well-described ABO blood group association with VWF clearance but is a new finding for VWFpp (Table 5, Figure S7A-B).

Table 5.

Comparison of effect size and direction of top meta-analysis SNPs for VWF and VWFpp

| VWF | VWFpp | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP (Minor Allele) | Chr | Locus | Beta* | P value* | Beta | P value |

| rs687289(A)† | 9 | ABO | 0.096 | 7.7E-138 | 0.019 | 1.3E-9 |

| rs8176746(T)‡ | 9 | ABO | 0.11 | 1.2E-49 | 0.044 | 1.6E-13 |

| rs1063856(C)§ | 12 | VWF | 0.031 | 6.7E-17 | 0.014 | 7.7E-6 |

| rs56835261(A) | 7 | Intergenic | 0.015 | 3.5E-2 | 0.035 | 8.5E-9 |

SNPs were selected for further analysis if they were the top SNPs defining a locus in the meta-analysis for VWF[3] or VWFpp levels.

Results from previous VWF analysis[3]

This SNP tags the common O allele of ABO

This SNP tags the common B allele of ABO

This SNP encodes a non-synonymous VWF variant T789P in D’ domain

The top SNP at the VWF locus was rs1063856, which encodes a non-synonymous variant (T789P) in the D’ domain of VWF. However, in the VWFpp analysis, no VWF SNPs reached genome-wide significance. rs1063856 had the same effect directions for both VWF and VWFpp but the effect size was greater with VWF (Table 5, Figure S7C), again consistent with a variant primarily affecting a VWF clearance mechanism. In the meta-analysis, seven SNPs in the intergenic regions of Chr 7 were associated with VWFpp. These SNPs were not significant in previous VWF GWAS studies [3, 9] and had a lower effect size with VWF suggesting the presence of a variant affecting clearance of VWFpp but not VWF (Figure S7D).

Discussion

This study reports the first heritability, linkage and genome-wide association analyses of VWFpp levels, with comparisons to previously published linkage and association studies of plasma VWF measured in the same cohorts. We found that both plasma VWF and VWFpp concentrations are highly heritable quantitative traits.

In our initial analysis of the VWFpp concentrations measured with a pair of anti-D2 domain antibodies, we detected a significant association for a non-synonymous SNP in the D2 domain of VWF. However, we determined that this result was likely an artifact due to an amino-acid substitution affecting antibody binding, not a genuine association with VWFpp levels. Similar apparent associations with non-synonymous SNPs in cis have been identified for several plasma proteins in the hemostatic system.[3, 36-38] In addition, according to the NHGRI GWAS catalog[39] (accessed on 12/16/2015), of the 150 reported GWAS of quantitative protein traits relying on antibody-based assays, 62 (40%) yielded significant associations with SNPs residing at the locus encoding the protein under investigation. While these SNPs may tag variants altering the level of the corresponding protein, our findings with rs1800378 and VWFpp suggest that a subset of these signals may be false positives generated by altered antibody binding affinities to the variant protein. This finding is similar to a report of a common VWF SNP causing altered VWF:RCo activity but not changing VWF levels.[40] These observations also resemble the caveats reported for gene expression QTL analysis where some cis-eQTLs may be due to variants in cDNA directly affecting hybridization to microarray probes.[41, 42] The implication for the genomics community is that extra caution is warranted in the interpretation of cis-QTLs for antibody-based protein traits. We suggest that non-synonymous SNP associations should be replicated using alternative antibody reagents.

Many genome-wide association studies have found significant associations with variants in intergenic regions that presumably regulate gene expression. This study identified an association between VWFpp and fourteen SNPs in an intergenic region on chromosome 7 that were ~725 Kb upstream from the nearest coding sequence of AUTS2. None of these SNPs affect gene expression according to an eQTL database[43] (accessed on 01/07/2016). For nine of these SNPs, “minimal binding evidence” was found by RegulomeDB[44] based on DNase-Seq and transcription factor binding motif hits (accessed on 01/25/2016); and twelve of these SNPs had an effect on at least one regulatory motif according to HaploReg[45] (version 4.1, accessed on 01/25/2016).There was no significant association of these SNPs with VWF levels which suggests that they may regulate the expression of a factor that affects the clearance of VWFpp from circulation independent of VWF. Since these SNPs were detected in the meta-analysis alone, further replication in an independent cohort is necessary for confirmation.

ABO blood group is an established modifier of plasma VWF levels. As other groups have reported,[46, 47] we found a significant difference in the VWF levels between high group homozygotes and high/low group heterozygotes suggesting an ABO allelic dose effect altering steady-state levels of plasma VWF as opposed to a clean dominant affect of A1 and B type antigens where we would expect no differences between homozygous high group and high/low group heterozygotes. Previous studies have failed to detect an association between ABO blood groups and VWFpp levels.[12, 48-50] Given the sample size of 3,238 individuals, our finding of a significant association was likely due to an increased power compared to earlier studies, which had smaller sample sizes ranging from 47 to 948 individuals. There are 4 potential N-linked glycosylation sites on VWFpp but no occupancy of ABO blood group antigens on these sites has been reported.[49] However, Groeneveld et al.[11] recently reported a study of VWF clearance suggesting the genotype of the individual is the primary determinant of ABO associated VWF clearance not the ABO glycoslylation pattern on VWF itself. If this finding applies to VWFpp as well, then the glycosylation pattern on VWFpp would be irrelevant. Nevertheless, the effect of the major ABO haplotypes on VWF and VWFpp was in the same direction, suggesting a shared mechanism of action but functional studies will be required to clarify how ABO antigens alter VWFpp clearance.

For the VWF SNPs, the difference in effect size between VWF and VWFpp and the absence of significant association with VWFpp levels suggest that the VWF variants operate through an altered clearance pathway(s). Investigators have cloned and functionally characterized many VWF mutations causing VWD,[51] but common VWF variants causing variation in VWF concentrations in healthy individuals have not yet been identified or well characterized. Previous studies by our group and others have documented an association of VWF levels with common variants at the VWF locus.[3, 9, 10] The top VWF SNP in our meta-analysis, rs1063856(C), encodes a missense variant in the D’ domain of VWF and could be a functional variant driving the association. Our study suggests that the VWF haplotype tagged by this SNP expresses a form of VWF with a prolonged plasma half-life compared to the VWF produced by the reference allele, and that the effect of this haplotype on VWFpp clearance is much weaker. The precise mechanism for the altered clearance of this VWF variant remains unknown.

Linkage analysis of VWFpp did not detect a QTL at Chr 2q12, which was previously identified as a QTL for VWF levels. The linkage interval contains many potential candidate genes; and our results suggest that genes potentially affecting protein clearance, such as sialotransferases (ST3GAL5) or lectin receptors (LMAN2L) are more attractive candidates than genes likely to affect synthesis or secretion pathways such as SNARE complex (VAMP5, VAMP8) or golgi-associated proteins (TGOLN2).

Our study used the comparative analysis of VWF and VWFpp to distinguish genetic variants affecting VWF or VWFpp clearance from those affecting synthesis and secretion. However, as a novel strategy to interpret differential association of two related proteins, our analyses had several limitations. First, by necessity, the measurement of VWFpp was performed with a different pair of antibodies than those employed in the VWF assay. This allows for differences in assay performance that may have led to false negative associations of VWFpp and therefore suggest differential clearance mechanism. However, this scenario is not very likely, as the heritability of the VWFpp was very similar to VWF, and both traits were measured in the same cohorts. Secondly, variants that were associated with both clearance and synthesis/secretion rates of VWFpp may have been undetectable in our analysis, for example, a variant associated with both decreased secretion rates and decreased clearance rates. Although our results strongly suggest a clearance mechanism for the major common modifiers of VWF, functional studies will be required for confirmation.

Taken together, the results of our VWFpp analyses provide new insights into the mechanism of action for common variants (at ABO and VWF) and potentially rare variants (at Chr 2 linage region) altering plasma VWF concentrations, and demonstrate a newly discovered association signal for VWFpp at Chr 7. This study is expected to facilitate the identification of functional variants controlling VWF variation and improve our understanding of the molecular mechanisms in individuals with bleeding disorders due to low VWF levels, or in individuals at risk for venous thromboembolic disease due to elevated VWF levels.[52]

Supplementary Material

Essentials.

Variants at ABO, von Willebrand Factor (VWF) and 2q12 contribute to the variation in plasma in VWF.

We performed a genome-wide association study of plasma VWF propeptide in 3,238 individuals.

ABO, VWF and 2q12 loci had weak or no association or linkage with plasma VWFpp levels.

VWF associated variants at ABO, VWF and 2q12 loci primarily affect VWF clearance rates.

Acknowledgments

We would like to recognize the contributions of the participants of the Genes and Blood Clotting Studies and the Trinity Student Studies to this study. This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, P01HL081588 (S.L. Haberichter), R37HL039693 (K.C. Desch, D. Ginsburg) and R01HL112642 (D. Ginsburg, J.Z. Li, A.B. Ozel and K.C. Desch). Additionally, D. Ginsburg is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. The TSS study was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

Author Contribution: A. B. Ozel, D. Ginsburg, J. Z. Li and K. C. Desch designed the research; P. M. Jacobi, B. McGee, and K. C. Desch and performed the experiments; A. B. Ozel, J. Z. Li and K. C. Desch analyzed results; A. B. Ozel and K. C. Desch made the figures; L. C. Brody, A. Molloy and J. L. Mills provided plasma samples from the TSS. K. C. Desch, A. B. Ozel, P. M. Jacobi, S. L. Haberichter, J. L. Mills, A. Molloy, L. C. Brody, D. Ginsburg and J. Z. Li wrote the paper.

Authors state no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Bladbjerg EM, de Maat MP, Christensen K, Bathum L, Jespersen J, Hjelmborg J. Genetic influence on thrombotic risk markers in the elderly--a Danish twin study. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2006 Mar;4:599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01778.x. PubMed PMID: 16371117. Epub 2005/12/24.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lange M, Snieder H, Ariens RA, Spector TD, Grant PJ. The genetics of haemostasis: a twin study. Lancet. 2001 Jan 13;357:101–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03541-8. PubMed PMID: 11197396. Epub 2001/02/24.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desch KC, Ozel AB, Siemieniak D, Kalish Y, Shavit JA, Thornburg CD, Sharathkumar AA, McHugh CP, Laurie CC, Crenshaw A, Mirel DB, Kim Y, Cropp CD, Molloy AM, Kirke PN, Bailey-Wilson JE, Wilson AF, Mills JL, Scott JM, Brody LC, et al. Linkage analysis identifies a locus for plasma von Willebrand factor undetected by genome-wide association. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Jan 8;110:588–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219885110. PubMed PMID: 23267103. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3545809. Epub 2012/12/26.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orstavik KH, Magnus P, Reisner H, Berg K, Graham JB, Nance W. Factor VIII and factor IX in a twin population. Evidence for a major effect of ABO locus on factor VIII level. Am J Hum Genet. 1985 Jan;37:89–101. PubMed PMID: 3919575. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1684532. Epub 1985/01/01.eng. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souto JC, Almasy L, Soria JM, Buil A, Stone W, Lathrop M, Blangero J, Fontcuberta J. Genome-wide linkage analysis of von Willebrand factor plasma levels: results from the GAIT project. Thromb Haemost. 2003 Mar;89:468–74. PubMed PMID: 12624629. Epub 2003/03/08.eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadler JE. von Willebrand factor: two sides of a coin. J Thromb Haemost. 2005 Aug;3:1702–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01369.x. PubMed PMID: 16102036. Epub 2005/08/17.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonneveld MA, de Maat MP, Leebeek FW. Von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13 in arterial thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Rev. 2014 Jul;28:167–78. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.04.003. PubMed PMID: 24825749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders YV, van der Bom JG, Isaacs A, Cnossen MH, de Maat MP, Laros-van Gorkom BA, Fijnvandraat K, Meijer K, van Duijn CM, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Eikenboom J, Leebeek FW, Wi NSG. CLEC4M and STXBP5 gene variations contribute to von Willebrand factor level variation in von Willebrand disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2015 Jun;13:956–66. doi: 10.1111/jth.12927. PubMed PMID: 25832887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith NL, Chen MH, Dehghan A, Strachan DP, Basu S, Soranzo N, Hayward C, Rudan I, Sabater-Lleal M, Bis JC, de Maat MP, Rumley A, Kong X, Yang Q, Williams FM, Vitart V, Campbell H, Malarstig A, Wiggins KL, Van Duijn CM, et al. Novel associations of multiple genetic loci with plasma levels of factor VII, factor VIII, and von Willebrand factor: The CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genome Epidemiology) Consortium. Circulation. 2010 Mar 30;121:1382–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.869156. PubMed PMID: 20231535. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2861278. Epub 2010/03/17.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campos M, Sun W, Yu F, Barbalic M, Tang W, Chambless LE, Wu KK, Ballantyne C, Folsom AR, Boerwinkle E, Dong JF. Genetic determinants of plasma von Willebrand factor antigen levels: a target gene SNP and haplotype analysis of ARIC cohort. Blood. 2011 May 12;117:5224–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300152. PubMed PMID: 21343614. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3109544. Epub 2011/02/24.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groeneveld DJ, van Bekkum T, Cheung KL, Dirven RJ, Castaman G, Reitsma PH, van Vlijmen B, Eikenboom J. No evidence for a direct effect of von Willebrand factor's ABH blood group antigens on von Willebrand factor clearance. J Thromb Haemost. 2015 Apr;13:592–600. doi: 10.1111/jth.12867. PubMed PMID: 25650553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallinaro L, Cattini MG, Sztukowska M, Padrini R, Sartorello F, Pontara E, Bertomoro A, Daidone V, Pagnan A, Casonato A. A shorter von Willebrand factor survival in O blood group subjects explains how ABO determinants influence plasma von Willebrand factor. Blood. 2008 Apr 1;111:3540–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-122945. PubMed PMID: 18245665. Epub 2008/02/05.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Donnell J, Boulton FE, Manning RA, Laffan MA. Amount of H antigen expressed on circulating von Willebrand factor is modified by ABO blood group genotype and is a major determinant of plasma von Willebrand factor antigen levels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002 Feb 1;22:335–41. doi: 10.1161/hq0202.103997. PubMed PMID: 11834538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohlke KL, Purkayastha AA, Westrick RJ, Smith PL, Petryniak B, Lowe JB, Ginsburg D. Mvwf, a dominant modifier of murine von Willebrand factor, results from altered lineage-specific expression of a glycosyltransferase. Cell. 1999 Jan 8;96:111–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80964-2. PubMed PMID: 9989502. Epub 1999/02/16.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Springer TA. Biology and physics of von Willebrand factor concatamers. J Thromb Haemost. 2011 Jul;9(Suppl 1):130–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04320.x. PubMed PMID: 21781248. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4117350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haberichter SL, Balistreri M, Christopherson P, Morateck P, Gavazova S, Bellissimo DB, Manco-Johnson MJ, Gill JC, Montgomery RR. Assay of the von Willebrand factor (VWF) propeptide to identify patients with type 1 von Willebrand disease with decreased VWF survival. Blood. 2006 Nov 15;108:3344–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015065. PubMed PMID: 16835381. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1895439. Epub 2006/07/13.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haberichter SL, Castaman G, Budde U, Peake I, Goodeve A, Rodeghiero F, Federici AB, Batlle J, Meyer D, Mazurier C, Goudemand J, Eikenboom J, Schneppenheim R, Ingerslev J, Vorlova Z, Habart D, Holmberg L, Lethagen S, Pasi J, Hill FG, et al. Identification of type 1 von Willebrand disease patients with reduced von Willebrand factor survival by assay of the VWF propeptide in the European study: molecular and clinical markers for the diagnosis and management of type 1 VWD (MCMDM-1VWD). Blood. 2008 May 15;111:4979–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110940. PubMed PMID: 18344424. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2384129. Epub 2008/03/18.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haberichter SL. von Willebrand factor propeptide: biology and clinical utility. Blood. 2015 Oct 8;126:1753–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-512731. PubMed PMID: 26215113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma Q, Ozel AB, Ramdas S, McGee B, Khoriaty R, Siemieniak D, Li HD, Guan Y, Brody LC, Mills JL, Molloy AM, Ginsburg D, Li JZ, Desch KC. Genetic variants in PLG, LPA, and SIGLEC 14 as well as smoking contribute to plasma plasminogen levels. Blood. 2014 Nov 13;124:3155–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-560086. PubMed PMID: 25208887. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4231423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desch K, Li J, Kim S, Laventhal N, Metzger K, Siemieniak D, Ginsburg D. Analysis of informed consent document utilization in a minimal-risk genetic study. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Sep 6;155:316–22. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-5-201109060-00009. PubMed PMID: 21893624. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3540806. Epub 2011/09/07.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mailman MD, Feolo M, Jin Y, Kimura M, Tryka K, Bagoutdinov R, Hao L, Kiang A, Paschall J, Phan L, Popova N, Pretel S, Ziyabari L, Lee M, Shao Y, Wang ZY, Sirotkin K, Ward M, Kholodov M, Zbicz K, et al. The NCBI dbGaP database of genotypes and phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2007 Oct;39:1181–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1007-1181. PubMed PMID: 17898773. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2031016. Epub 2007/09/28.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Browning BL, Browning SR. A unified approach to genotype imputation and haplotype-phase inference for large data sets of trios and unrelated individuals. Am J Hum Genet. 2009 Feb;84:210–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.005. PubMed PMID: 19200528. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2668004. Epub 2009/02/10.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaneau O, Howie B, Cox AJ, Zagury JF, Marchini J. Haplotype estimation using sequencing reads. Am J Hum Genet. 2013 Oct 3;93:687–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.09.002. PubMed PMID: 24094745. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3791270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012 Aug;44:955–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. PubMed PMID: 22820512. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3696580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu X, Li S, Cooper RS, Elston RC. A unified association analysis approach for family and unrelated samples correcting for stratification. Am J Hum Genet. 2008 Feb;82:352–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.10.009. PubMed PMID: 18252216. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2427300. Epub 2008/02/07.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang HM, Sul JH, Service SK, Zaitlen NA, Kong SY, Freimer NB, Sabatti C, Eskin E. Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2010 Apr;42:348–54. doi: 10.1038/ng.548. PubMed PMID: 20208533. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3092069. Epub 2010/03/09.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007 Sep;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. PubMed PMID: 17701901. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1950838. Epub 2007/08/19.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devlin B, Roeder K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics. 1999 Dec;55:997–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00997.x. PubMed PMID: 11315092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilier CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010 Sep 1;26:2190–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. PubMed PMID: 20616382. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2922887. Epub 2010/07/10.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR, Willer CJ. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010 Sep 15;26:2336–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. PubMed PMID: 20634204. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2935401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature methods. 2010 Apr;7:248–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. PubMed PMID: 20354512. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2855889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. Merlin--rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet. 2002 Jan;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. PubMed PMID: 11731797. Epub 2001/12/04.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ihaka R, Gentleman R. R: A language for data analysis and graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 1996;5:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011 Jan 7;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. PubMed PMID: 21167468. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3014363. Epub 2010/12/21.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbalic M, Dupuis J, Dehghan A, Bis JC, Hoogeveen RC, Schnabel RB, Nambi V, Bretler M, Smith NL, Peters A, Lu C, Tracy RP, Aleksic N, Heeriga J, Keaney JF, Jr., Rice K, Lip GY, Vasan RS, Glazer NL, Larson MG, et al. Large-scale genomic studies reveal central role of ABO in sP-selectin and sICAM-1 levels. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 May 1;19:1863–72. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq061. PubMed PMID: 20167578. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2850624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Vries PS, Boender J, Sonneveld MA, Rivadeneira F, Ikram MA, Rottensteiner H, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Leebeek FW, Franco OH, Dehghan A, de Maat MP. Genetic variants in the ADAMTS13 and SUPT3H genes are associated with ADAMTS13 activity. Blood. 2015 May 1; doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-629865. PubMed PMID: 25934476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang J, Sabater-Lleal M, Asselbergs FW, Tregouet D, Shin S-Y, Ding J, Baumert J, Oudot-Mellakh T, Folkersen L, Johnson AD, Smith NL, Williams SM, Ikram MA, Kleber ME, Becker DM, Truong V, Mychaleckyj JC, Tang W, Yang Q, Sennblad B, et al. Genome-wide association study for circulating levels of PAI-1 provides novel insights into its regulation. Blood. 2012 Dec 6;120:4873–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-436188. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang W, Basu S, Kong X, Pankow JS, Aleksic N, Tan A, Cushman M, Boerwinkle E, Folsom AR. Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci for plasma levels of protein C: the ARIC study. Blood. 2010 Dec 2;116:5032–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-283739. PubMed PMID: 20802025. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3012596. Epub 2010/08/31.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welter D, MacArthur J, Morales J, Burdett T, Hall P, Junkins H, Klemm A, Flicek P, Manolio T, Hindorff L, Parkinson H. The NHGRI GWAS Catalog, a curated resource of SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jan;42:D1001–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1229. PubMed PMID: 24316577. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3965119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flood VH, Gill JC, Morateck PA, Christopherson PA, Friedman KD, Haberichter SL, Branchford BR, Hoffmann RG, Abshire TC, Di Paola JA, Hoots WK, Leissinger C, Lusher JM, Ragni MV, Shapiro AD, Montgomery RR. Common VWF exon 28 polymorphisms in African Americans affecting the VWF activity assay by ristocetin cofactor. Blood. 2010 Jul 15;116:280–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249102. PubMed PMID: 20231421. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2910611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sliwerska E, Meng F, Speed TP, Jones EG, Bunney WE, Akil H, Watson SJ, Burmeister M. SNPs on chips: the hidden genetic code in expression arrays. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 Jan 1;61:13–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.023. PubMed PMID: 16690034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benovoy D, Kwan T, Majewski J. Effect of polymorphisms within probe-target sequences on olignonucleotide microarray experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008 Aug;36:4417–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn409. PubMed PMID: 18596082. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2490733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veyrieras JB, Kudaravalli S, Kim SY, Dermitzakis ET, Gilad Y, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. High-resolution mapping of expression-QTLs yields insight into human gene regulation. PLoS genetics. 2008 Oct;4:e1000214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000214. PubMed PMID: 18846210. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2556086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyle AP, Hong EL, Hariharan M, Cheng Y, Schaub MA, Kasowski M, Karczewski KJ, Park J, Hitz BC, Weng S, Cherry JM, Snyder M. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012 Sep;22:1790–7. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. PubMed PMID: 22955989. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3431494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Jan;40:D930–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. PubMed PMID: 22064851. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3245002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souto JC, Almasy L, Muniz-Diaz E, Soria JM, Borrell M, Bayen L, Mateo J, Madoz P, Stone W, Blangero J, Fontcuberta J. Functional effects of the ABO locus polymorphism on plasma levels of von Willebrand factor, factor VIII, and activated partial thromboplastin time. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000 Aug;20:2024–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.8.2024. PubMed PMID: 10938027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shima M, Fujimura Y, Nishiyama T, Tsujiuchi T, Narita N, Matsui T, Titani K, Katayama M, Yamamoto F, Yoshioka A. ABO blood group genotype and plasma von Willebrand factor in normal individuals. Vox Sang. 1995;68:236–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1995.tb02579.x. PubMed PMID: 7660643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eikenboom J, Federici AB, Dirven RJ, Castaman G, Rodeghiero F, Budde U, Schneppenheim R, Batlle J, Canciani MT, Goudemand J, Peake I, Goodeve A. VWF propeptide and ratios between VWF, VWF propeptide, and FVIII in the characterization of type 1 von Willebrand disease. Blood. 2013 Mar 21;121:2336–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-455089. PubMed PMID: 23349392. Epub 2013/01/26.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nossent AY, V VANM, NH VANT, Rosendaal FR, Bertina RM, JA VANM, Eikenboom HC. von Willebrand factor and its propeptide: the influence of secretion and clearance on protein levels and the risk of venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2006 Dec;4:2556–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02273.x. PubMed PMID: 17059421. Epub 2006/10/25.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marianor M, Zaidah AW, Maraina Ch C. von Willebrand Factor Propeptide: A Potential Disease Biomarker Not Affected by ABO Blood Groups. Biomarker insights. 2015;10:75–9. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S24353. PubMed PMID: 26339184. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4548735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hampshire DJ, Goodeve AC. The international society on thrombosis and haematosis von Willebrand disease database: an update. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011 Jul;37:470–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281031. PubMed PMID: 22102189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith NL, Rice KM, Bovill EG, Cushman M, Bis JC, McKnight B, Lumley T, Glazer NL, van Hylckama Vlieg A, Tang W, Dehghan A, Strachan DP, O'Donnell CJ, Rotter JI, Heckbert SR, Psaty BM, Rosendaal FR. Genetic variation associated with plasma von Willebrand factor levels and the risk of incident venous thrombosis. Blood. 2011 Jun 2;117:6007–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-315473. PubMed PMID: 21163921. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3112044. Epub 2010/12/18.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.