Abstract

Despite the availability of efficacious treatments, only half of patients with hypertension achieve adequate blood pressure (BP) control. This paper describes the protocol and baseline subject characteristics of a 2-arm, 18-month randomized clinical trial of titrated disease management (TDM) for patients with pharmaceutically-treated hypertension for whom systolic blood pressure (SBP) is not controlled (≥140mmHg for non-diabetic or ≥130mmHg for diabetic patients). The trial is being conducted among patients of four clinic locations associated with a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. An intervention arm has a TDM strategy in which patients' hypertension control at baseline, 6, and 12 months determines the resource intensity of disease management. Intensity levels include: a low-intensity strategy utilizing a licensed practical nurse to provide bi-monthly, non-tailored behavioral support calls to patients whose SBP comes under control; medium-intensity strategy utilizing a registered nurse to provide monthly tailored behavioral support telephone calls plus home BP monitoring; and high-intensity strategy utilizing a pharmacist to provide monthly tailored behavioral support telephone calls, home BP monitoring, and pharmacist-directed medication management. Control arm patients receive the low-intensity strategy regardless of BP control. The primary outcome is SBP. There are 385 randomized (192 intervention; 193 control) veterans that are predominately older (mean age 63.5 years) men (92.5%). 61.8% are African American, and the mean baseline SBP for all subjects is 143.6mmHg. This trial will determine if a disease management program that is titrated by matching the intensity of resources to patients' BP control leads to superior outcomes compared to a low-intensity management strategy.

Keywords: hypertension, randomized controlled trial, veterans

1. Introduction

Despite its prevalence, associated morbidity and mortality, presence of evidence-based guidelines, and availability of more than 100 anti-hypertensive medications,1 only approximately half of American adults with hypertension (HTN) have achieved adequate blood pressure (BP) control.2, 3 Clinical trial results indicate that self-management support is critical to successful management of HTN and other chronic conditions.4–8 Results from randomized trials would typically lead decision-makers to implement effective strategies per protocol. However, one size may not fit all. Instead, analogous to titrating medications when BP is above clinical targets,9 patients might reasonably require differing intensity of disease management depending on whether they have achieved these clinical targets. We are conducting a pragmatic clinical trial to evaluate the effectiveness of titrated disease management in which the intensity of disease management is adjusted based on an individual’s systolic blood pressure (SBP).

1.1. Defining Titrated Disease Management (TDM)

We view the process of TDM as analogous to the common process of titrating medication dosage in clinical care. For example, clinical guidelines often recommend adjusting the dosage and/or number of anti-hypertensive agents based on clinical parameters. This is often in the form of stepped care, where patient’s initial medication dose is low to minimize risks of treatment (such as side effects).10 If patients are not responsive to initial treatments, their medication regimen is intensified until clinical goals are met. Absent some change in the underlying pathophysiology of disease (e.g., weight loss) or side effects, patients do not have their treatment reduced once clinical goals are reached; it is assumed that any reduction in intensity would diminish level of control.11–13

We are conducting a pragmatic trial to examine the effectiveness of titrated (not stepped) care when applied to disease management. Specifically, we are adjusting (titrating) the resource intensity (and expense) of a disease management strategy based upon the patient’s clinical status. Depending on the individual’s BP, resources are either intensified or reduced to achieve or maintain BP control. This resource intensity differs by: 1) who delivers disease management; 2) the complexity of the treatment (i.e., whether there is medication intensification); and 3) frequency of patient contacts. The assumption of this novel approach is that patients will be titrated to different initial resource levels and will be evaluated over time to determine if they will: 1) remain at the same level of resource intensity; 2) increase to a higher intensity level; or 3) decrease to a lower resource intensity level. This type of titration addresses a criticism about stepped care where there is no plan to reduce level of drug or other resource use for patients with improving illness severity.14

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sponsorship and IRB Approval

This trial is funded by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development Service (grant # IIR 10–383; clinicaltrials.gov registration # NCT01390272). It is being conducted under the approval of the Intuitional Review Board (IRB) of the Durham VA Medical Center.

2.2. Specific Aims of the Pragmatic Trial

The primary question of the pragmatic trial is: will the TDM intervention reduce systolic blood pressure (SBP) over 18-months compared to licensed practical nurse (LPN)-delivered behavioral support calls occurring every two months [control arm]? The primary hypothesis is that veterans randomized to TDM will have greater improvement in mean SBP over the 18 months of follow-up than veterans in the control arm. Secondary outcomes include HTN control (dichotomous), cost-effectiveness (if successful), and adherence to hypertension medications.

2.2. Setting

The study is being conducted among patients receiving primary care at clinics in four separate locations affiliated with the Durham VA Medical Center. One location is the main VA hospital, one satellite clinic is located approximately 1.5 driving miles to the north, a second clinic is located approximately 45 driving miles to the east, and a final clinic is located approximately 110 driving miles east of the hospital. In 2015, these sites had approximately 46 primary care provider (PCP) full-time equivalents for delivery of care to approximately 44,000 unique patients.

2.3. Summary of the Intervention

This is a two-arm 18-month pragmatic randomized clinical trial for veterans with pharmaceutically-treated hypertension and uncontrolled SBP (defined as ≥ 140mmHg for non-diabetic or ≥ 130mmHg for diabetic patients). The intervention arm includes three levels of resource intensity targeted to improve patients’ SBP (Table 1).

Low resource intensity: An LPN provides non-tailored behavioral support telephone calls every two months to patients whose SBP comes under control. The low resource intensity also serves as the control arm (described below).

Medium resource intensity: A registered nurse (RN) provides monthly tailored behavioral support telephone calls plus home BP monitoring.

High resource intensity: A pharmacist provides monthly tailored behavioral support telephone calls, home BP monitoring and pharmacist-directed medication management.

Table 1.

Summary of Differences in Intervention Resource Levels

| Attributes | Resource Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low* | Medium | High | |

| Delivered by | Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) |

Registered Nurse (RN) | Pharmacist |

| Key clinician attributes |

|

|

|

| Behavioral call frequency | Every two months | Monthly | Monthly |

|

Modules activated by telephone calls will be tailored to patient |

No | Yes | Yes |

|

Clinician trained in motivational interviewing |

No | Yes | Yes |

| Home BP monitoring | Not part of intervention | Yes | Yes |

|

Pharmaceutical management |

No | No | Yes |

The control arm for the study is delivery of the LPN / low intensity calls as described.

At the initial baseline visit patients who are randomized into the intervention arm are first titrated to either RN or pharmacist levels based on baseline blood pressure values. Subsequent titrations that include the LPN level happen at the 6 and 12 month study visits.

In the control arm (Table 1), a LPN provides behavioral support telephone calls every two months. This is identical to the low resource intensity component of the TDM intervention. This control arm differs from usual care in that patients receive additional regular contact that has been shown to enhance BP control among veterans15 and medication adherence among North Carolina Medicaid beneficiaries.16

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible individuals included English speaking adults living in the community with access to a telephone who had been seen at a study clinic in the last year, had a VA PCP (Table 2). and had a history of pharmaceutically-treated HTN with uncontrolled SBP in the past year.17 Specifically, based on the Seventh Report of the Joint National Commission on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC7), HTN is considered uncontrolled if SBP is ≥ 140mmHg for patients without diabetes or ≥ 130mmHg for patients with diabetes. While JNC 8 guidelines were issued during the trial,9 we continued to utilize JNC 7 criteria so we could maintain consistent therapeutic goals throughout the study. BP control was based on mean SBP during the year prior to periodic data pulls from the VA electronic health record (described below). Because of the labile nature of blood pressure, patients were identified in the data pulls as being potentially eligible based on a SBP 10mmHG over JNC7 guidelines. (i.e., 150mmHg for patients without diabetes or 140mmHg for patients with diabetes).

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria |

Inclusion Criteria Determined by Initial Review of the VA Electronic Health Record

|

Inclusion Criteria Determined during the Initial Screening Phone Call

|

| Exclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria Determined by Initial Review of the VA Electronic Health Record by Chart Review

|

Exclusion Criteria Determined during the Initial Screening Phone Call

|

Exclusion Criteria Determined during the Baseline In-Person Visit

|

BP - blood pressure; CBOC - community-based outpatient clinic; CVD - cardiovascular disease; PCP - primary care provider; VAMC - Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Patients were excluded if they had known type 1 diabetes, class IV congestive heart failure, end stage renal disease, metastatic cancer, a history of solid organ or bone marrow transplantation, or a diagnosis of active psychosis at baseline. Additionally, patients were excluded if they were enrolled in any ongoing clinical trial or specific clinical program that would be expected to impact blood pressure control. Women who reported being pregnant or planning to become pregnant over the next 18 months were also excluded.

2.4.1. Change In Inclusion Criteria During the Study

To be eligible, patients were initially required to have uncontrolled study SBP (≥ 140mmHg without diabetes; ≥ 130mmHg with diabetes) at baseline, which was assessed after the patient provided informed consent, but before randomization. While this criterion was in place, 41.3% of patients who consented did not meet the threshold for being out of control. Because these patients are likely to have been cycling in and out of control, we decided patients meeting study criteria while having baseline SBP control would likely benefit from the intervention and, as such, should be randomized. The IRB approved this modification.

2.5. Screening and Enrollment

Potential subjects were initially identified based upon data extracted from the VA electronic health record (EHR) using inclusion and exclusion criteria (above). PCPs were informed of the study and could request to review lists of potentially eligible patients to approve patients’ potential participation in the study (i.e., whether individual patients could remain on the list). Providers choosing to review lists of potentially eligible patients had 14 days from receiving the list to conduct the review and contact study team with any concerns about individual listed patients participating in the study. Only one PCP chose to review patient lists.

Letters were sent from the principal investigator and study physician to potentially eligible patients allowing them to opt out of the study. For subjects who did not opt-out, study staff conducted a screening phone call to further assess inclusion and exclusion criteria and schedule baseline study visits. Given the large number of potentially eligible subjects, chart review was prioritized for patients having upcoming appointments within 4–6 weeks; doing so allowed baseline study visits to coincide with a patient’s clinic visit. After approximately 7 months of enrollment, patients living within approximately 50 miles of a participating clinic were also prioritized to enhance enrollment rates.

2.6. Patient Compensation

Patients receive $15 for each of the four data collection visits (baseline, 6, 12, and 18-months), for a total potential payment of $60 for participating in the study.

2.7. Protocol for Measuring Baseline and Outcome Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP)

At each study visit (including baseline), the SBP outcome is based on the mean of three BP measures obtained 30 seconds apart after the patient has sat for 5 minutes. All BP measurements are performed using electronic BP cuffs, which have been shown to be equivalent to (and ecologically safer) than the gold standard of random zero sphygmomanometers.18 The same type of electronic BP cuff is being used for all clinic locations in the study (Omron Digital Blood Pressure Monitor HEM-907XL).

2.8. Randomization

We used blocked randomization stratified by diabetes status (because of differing HTN treatment goals) and baseline SBP [up to moderately out of control: SBP < 150mmHg for non-diabetic patients (or < 140mmHg for diabetic patients); significantly out of control: SBP ≥ 150mmHg for non-diabetic patients (or ≥ 140mmHg for diabetic patients)]. Research assistants were blinded to randomization block size. Diabetes was defined from EHR data as having both: ICD-9 diagnosis code 250.xx on ≥ 2 outpatient encounters during the prior year and a prescription for oral hypoglycemic medication (e.g., sulfonylurea, metformin, thiazolidinedione, secretagogues, acarbose) and/or insulin during the past year.

It was not feasible to blind personnel who collected study outcome data to the assigned study arm. To minimize bias, baseline outcome data were collected prior to randomization and SBP measurement outcome data collection utilized an electronic blood pressure machine and standard protocol, which is described above.

2.9. Intervention

2.9.1. Titration Algorithms

The protocol for titrating resource intensity of the intervention depended on BP control. Titration algorithms are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Intervention Titration Algorithm

| Baseline Titration |

Based on mean baseline study visit SBP values:

|

| Planned Titration at 6 and 12 Months |

Based on the mean of all available SBP values up to 31 days prior to the patients study visit, including study visit BP values, any clinic BP values, and/or any home BP values provided to during the intervention:

|

| Unplanned Titration Between 6 and 12 Months |

intensity level for at least 6 months (for example, if a patient is up stepped at month 3, they will not be reevaluated for possible down stepping until month 12). |

BP - blood pressure; mmHg – millimeters of mercury; LPN – licensed practical nurse; RN – registered nurse; SBP – systolic blood pressure; VA – Veterans Affairs

2.9.2. Intervention Component – Telephone Self-Management Support [medium- and high-level resource intensity]

Patients receiving medium resource intensity disease management receive calls from a RN; patients receiving high resource intensity disease management receive calls from a pharmacist (PharmD). The calls combine tailored information and feedback that address aspects of hypertension management specifically relevant to a particular patient.19 Drawing on stages of change,20, 21 and a revised Health Decision Model (HDM) that considers how patients’ beliefs, environment, and characteristics impact decisions concerning health behaviors,21–23 the intervention addresses how to: 1) set realistic, healthy goals that reflect patient preferences and readiness to change and support self-efficacy for achieving those goals,24–27 2) implement healthful behaviors and monitor performance, and 3) maintain the behaviors and associated hypertension control over time. To further tailor the intervention, callers use scripted modules based on patients’ specific needs identified from questions asked during the call. For example, patients who report they are current smokers are asked about their readiness to quit smoking.

Training Personnel Making Calls

Prior to starting the intervention, the RNs and pharmacist delivering the calls were trained in motivational interviewing (MI). MI is a tool that can assist individuals work through ambivalence about behavior change. Interventionists were provided didactic training on the basic principles of MI, including asking open-ended questions, learning how to use reflective listening, and learning to identify and elicit “change talk” from a patient. The LPN delivering low resource intensity calls did not receive training in MI and followed non-tailored telephone call scripts.

Mechanics of Making Calls

The interventionist calls patients within two weeks after randomization. Subsequent contacts are scheduled approximately monthly. Between scheduled calls, patients are encouraged to telephone the interventionist with questions related to their hypertension, including (but not limited to) control of their BP and the pharmacological or non-pharmacological management of HTN. Should emergent healthcare issues arise during these calls, the study contacts the patient’s PCP (or covering provider) via a note in the EHR or refers the patient to emergency care.

Content of Calls

The interventionist utilizes computerized software to guide tailored patient modules during the intervention calls. Each module addresses either (1) a health behavior (e.g., exercise) that is desirable for BP control or (2) a modifiable patient factor that can improve control (e.g., hypertension knowledge, memory) that may impact medication adherence. The modules are “activated” (introduced as a topic) when a patient reports a barrier that the module was designed to address.

A major emphasis of the intervention is initiating and maintaining specific health behaviors related to HTN. During each monthly call, a core group of modules were available. All RN and PharmD phone calls addressed medication management, side effects (with the exception of the first call) and home BP monitoring. An additional health behavior or modifiable patient factor was also addressed. Topics covered in calls can be found in Table 4. The call schedules for the RN, pharmacist, and LPN (control arm) calls can be found in Table 5.

Table 4.

Intervention Arm Module Content – Medium (RN) and High (pharmacist) Resource Levels*

| Topic | Module Content |

|---|---|

|

Opening Module/Medication Management [delivered during each call] |

|

|

Adverse Effects of Antihypertensive Medication [delivered during each call] |

|

| Memory |

|

|

Knowledge/Risk Perception |

|

|

Participatory Decision- Making and Patient- Provider Communication |

|

| Diet |

|

| Weight |

|

| Exercise |

|

|

Social and Medical Environment/Access to Care. |

|

|

Stress, Mental Health, Insomnia and Sleep Apnea. |

|

| Smoking |

|

|

Closing Module [delivered during each call] |

|

BP - blood pressure; PCP - primary care provider

LPN calls provide knowledge-based information on these topics, with the exception of diet, exercise, mental health, and sleep apnea based on the schedule in Table 5.

Table 5.

TDM Trial Module Schedule

| RN & PharmD Encounters with Module Topic | ||

|

Encounter 1: Opening/Closing Medications/Side Effects CVD knowledge Memory Adverse Events |

Encounter 7 Opening/Closing Medications/Side Effects Weight loss Alcohol Adverse Events |

Encounter 13 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Weight loss goal f/u Adverse Events |

|

Encounter 2 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Tobacco use Social Support Adverse Events |

Encounter 8 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Diet Tobacco use goal f/u 1 mo weight loss f/u Adverse Events |

Encounter 14 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Alcohol Adverse Events |

|

Encounter 3 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Mental Health 1 mo f/u tobacco use Adverse Events |

Encounter 9 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Insomnia Apnea Adverse Events |

Encounter 15 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Insomnia Apnea Adverse Events |

|

Encounter 4 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Diet Pt-Physician Interaction Adverse Events |

Encounter 10 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects CVD knowledge Memory Adverse Events |

Encounter 16 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Diet Adverse Events |

|

Encounter 5 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Exercise Adverse Events |

Encounter 11 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Pt-Physician interaction 6 mo f/u Adverse Events |

Encounter 17 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Stress Adverse Events |

|

Encounter 6 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Stress 1 mo f/u exercise Adverse Events |

Encounter 12 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Diet Mental Health Adverse Events |

Encounter 18 Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Adverse Events Final call summary |

| LPN Encounters with Module Topic | ||

|

Encounter 1 (maps to Enc. 1 & 2 of RN/PharmD schedule): Opening/Closing Medications HTN knowledge* Memory Tobacco Use Adverse Events |

Encounter 5 (maps to Enc. 9 & 10 of RN/PharmD schedule): Opening/Closing Medications Memory HTN Knowledge* Adverse Events |

*HTN Knowledge is similar to the RN/PharmD script for CVD Knowledge *Decision Making is similar to the to the RN/PharmD script for Patient-Physician Interaction |

|

Encounter 2 (maps to Enc. 3 & 4 of RN/PharmD schedule without goal follow up): Opening/Closing Medications Social Support Decision Making* Adverse Events |

Encounter 6 (maps to Enc. 11 & 12 of RN/PharmD schedule without goal follow up): Opening/Closing Medications Decision Making* Adverse Events |

|

|

Encounter 3 (maps to Enc. 5 & 6 of RN/PharmD schedule without goal follow up): Opening/Closing Medications Stress Adverse Events |

Encounter 7 (maps to Enc. 13 &.14 of RN/PharmD schedule): Opening/Closing Medications Alcohol Adverse Events |

|

|

Encounter 4 (maps to Enc. 7 & 8 of RN/PharmD schedule without goal follow up): Opening/Closing Medications Alcohol Tobacco Use Adverse Events |

Encounter 8 (maps to Enc. 15 & 16 of RN/PharmD schedule): Opening/Closing Medications Adverse Events |

|

|

Encounter 9 (maps to Enc. 17 & 18 of RN/PharmD schedule): Opening/Closing Medications/ Side Effects Stress Adverse Events |

||

Enc. - encounter ; LPN – licensed practical nurse; PharmD - doctor of pharmacy (pharmacist); RN - registered nurse; HTN – hypertension, Pt – Patient, f/u – follow-up

2.9.3. Intervention Component – Booster Level Phone Calls

Patients whose SBP comes under control at 6 or 12 months are switched to low resource intensity LPN phone calls. Low resource intensity calls occur every two months instead of monthly and follow a standardized script with no tailoring or probing about BP measurements.

2.9.4 Intervention Component – Home BP Monitoring: Medium and High Resource Intensity

All patients randomized to the intervention arm who do not currently have a VA approved home BP monitor were eligible to receive one. They receive training in its use at their baseline study visit according to a protocol developed in our prior studies.28 Patients are instructed to check their BP every other day using a defined protocol similar to previous studies.29 We request individuals to provide their BP values for the two weeks prior to the monthly intervention calls so that the interventionist (RN or pharmacist) could assess their BP control. Patients are reminded to record their BP as part of the intervention calls.

2.9.5. Intervention Component – Pharmacist-Directed Algorithmic Medication Management [high resource intensity only]

Patients who meet criteria for high resource intensity disease management receive medication management from a clinical pharmacist, who will be backed up by a study physician. Pharmacists are authorized to make medication changes according to accepted treatment algorithms and based on their scope of practice. Via the VA EHR, the pharmacist will also communicate these changes to the patient’s PCP. While pharmacists in the VA may collaborate with the patients’ providers when clinically indicated, they do not have to rely on them to make the changes. The study pharmacist attempts to contact patients every month while they are in the high-intensity titration level of the intervention. During each contact, the pharmacist has information from both the VA EHR and the behavioral support calls conducted as part of the intervention so information on such topics as patient medication and barriers to adherence can be available. During the initial call, the pharmacist assesses the patient’s medication adherence, reviews all BP-related medications, and discusses the purpose and appropriate administration of each medication. The pharmacist (or appropriately licensed clinical backup) may discuss other medicines if he or she feels that this is needed to appropriately manage BP medication. At subsequent contacts, the pharmacist reviews any medication changes with the patients and updates patients’ medication lists. For patients who require a change in their prescription, the pharmacist writes the prescription, and then communicates the change to the patient’s PCP using standard clinic procedures.

2.10. Control Arm

Control patients receive the low resource intensity intervention, which is described above, for the entire study period.

2.11. Outcomes and Study Measures

Table 6 lists all study measures and time points at which information is being collected.

Table 6.

Study Measures

| Baseline | 6 Month |

12 Month |

18 Month |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | ||||

| Blood pressure | X | X | X | X |

| Adverse Events | ||||

| Adverse events* | X | X | X | |

| Falls, lightheadedness, fatigue | X | X | X | |

| Assessment of Cognitive Ability for Determination of Eligibility | ||||

| Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ)52–54 | X | |||

| Demographics and Socioeconomic Status | ||||

| Gender | X | |||

| Age | X | |||

| Race | X | |||

| Ethnicity | X | |||

| Educational level (highest completed grade) | X | |||

| Marital Status | X | X | X | X |

| Number of people living in the patient’s household | X | X | X | X |

| Adequacy of income | X | X | X | X |

| Employment status | X | X | X | X |

| Help with tasks | X | X | X | X |

| Components of Body Mass Index | ||||

| Height | X | X | X | X |

| Weight | X | X | X | X |

| Additional Measures | ||||

| Self-reported medication adherence – Modification of the Morisky measure68 |

X | X | X | X |

| Self-efficacy for management of hypertension69 | X | X | X | X |

| Exercise – Short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)70 | X | X | X | X |

| Literacy – Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM)71 | X | |||

| Social support – Presence of a close personal relationship | X | |||

| Quality of Life – EuroQol (EQ)-5D-5L72 | X | X | X | X |

| Organization of Primary Care – Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC)73–75 |

X | X | ||

| Risk of having sleep apnea - Berlin questionnaire76 | X | |||

| Health Behavior (smoking & alcohol use) | X | X | X | X |

| Health (years living with hypertension; home use of BP monitor; diagnosis of sleep apnea and subsequent use of cpap machine) |

X | X | X | X |

| Family history of hypertension | X | |||

Adverse events reported during study phone calls are also collected and reported.

2.11.1. Primary Outcome – Continuous Change in Systolic Blood Pressure

SBP is the primary outcome because it has greater association with cardiovascular disease risk than diastolic BP among patients with pharmaceutically-treated hypertension.30–32 The procedure for measuring SBP at all study visits is described above in section 2.7.

2.11.2. Secondary Outcome – SBP Control

This is a dichotomous outcome in which control is defined as SBP ≤ 130mmHg for hypertensive patients with diabetes and ≤ 140mmHg for patients without diabetes.

2.11.3. Secondary Outcome – Adherence to Blood Pressure Medication

Adherence is measured as the supply of medications patients have, expressed as a Medication Possession Ratio (MPR). We use the ReComp MPR algorithm,33, 34 which was developed and validated using pharmacy refill data to measure adherence with antihypertensive medication [considered together for adherence].

2.12. Planned Data Analysis

Our pre-specified primary and secondary hypotheses will be tested with two-sided p-values at the p < 0.05 level using intent-to-treat basis; we analyze all data up to the 18-months follow-up (or last available prior to exclusion or dropout).35 Statistical analyses will be performed using SAS for Windows (version 9.4: SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (http://www.R-project.org).

2.12.1. Planned Analysis

To examine the impact of TDM on mean SBP over 18 months, we will use a linear mixed model.36 Baseline, 6-, 12- and 18-month values in the response vector will be used to estimate changes in SBP over time and test the primary hypothesis. The predictors in the model will include time and the intervention-by-time interaction. This constrained longitudinal model (cLDA) assumes the study arms have equal baseline means, which is appropriate for a randomized control trial and is equivalent in efficiency to an ANCOVA.37 Results from exploratory graphical methods as well as model selection criteria will be used to select the most appropriate way to model time over the 18 month follow up.

We will fit models using the SAS procedure MIXED (Cary, NC), which handles dropout in a principled manner. However, depending on the type and scope of missing data, we will also explore multiple imputation as a strategy to use in conjunction with our primary analytic tools.38 Secondary analyses will be conducted in a similar manner, testing for differences in medication adherence as a continuous outcome. For BP control and dichotomous adherence, similar modeling procedures will be followed using generalized linear mixed models using PROC GLIMMIX with adaptive quadrature.36

2.12.2. Sample Size Considerations

We estimated that 400 subjects (200 per arm) would be required to detect a 5mmHg difference in SBP at 18 months with 80% power and a type-I error of 5%. We used a method based on ANCOVA type analyses39 where we assumed an expected mean baseline mean SBP of 145mmHg, standard deviation of 17.5mmHg, correlation between repeated measurements of 0.4, and attrition rate of 15% by 18 months.

2.12.3. Planned Analysis of Secondary Outcome – Cost Effectiveness

The primary objective of the cost-effectiveness analysis is to estimate the cost per unit difference in effectiveness (if intervention is effective). The incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) will be calculated as the difference in the average cost per patient between the treatment and control arm divided by the difference in mmHg between the treatment and control arms. Salaries specific to LPN, RN, and pharmacist will be used to calculate cost of interventionist time. This time includes preparing for intervention calls, attempting to make calls, and delivering the intervention. We will account for the amount of time that patients spend at the high, medium, and low resource levels of the intervention (including actions taken). Sensitivity analyses will also be performed on types of costs: intervention, resource utilization, and total (intervention plus resource utilization) costs. If there are no differences in resource utilization across arms, we will simply include the intervention costs in the ICER calculation. All dollars will be expressed in constant dollars (e.g. 2016), using the Consumer Price Index for Medical Care for medical items or Consumer Price Index for other items.

3.0. Results of Enrollment Procedures

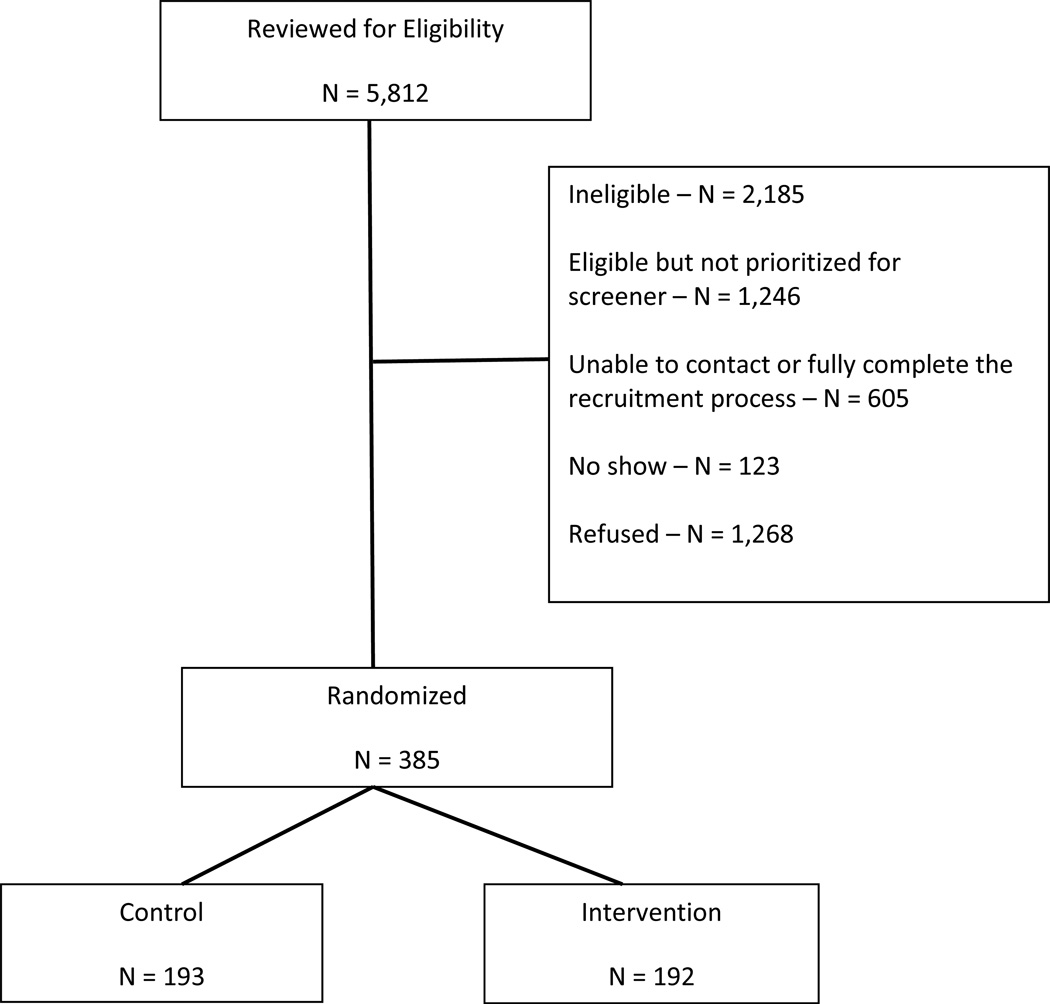

Chart review eligibility assessments were performed on 5,812 patients (Figure 1). Patients may have been found to be ineligible during the recruitment process (2,185), not prioritized for further screening based on operating procedures described above (1,246), unable to contact for or fully complete a recruitment process [e.g., not able to complete a screening call in the time allotted] (605), not attending the baseline study visit (123) or have declined to participate when the recruitment letter was sent, during the screening telephone call, or at the baseline/consent study visit (1,268). In total, 385 veterans were enrolled and randomized between November 6, 2012 and April 9, 2015, 192 to the intervention arm and 193 to the control arm.

Figure 1.

Study Flow through Randomization

Reflecting the VA patient population as a whole, subjects are predominately men (92.5%). Their mean age was = 63.5 years. The majority of patients are black (61.8%), with 33.8% being white and 4.5% being of another race or multiple races; 3.4% are of Latino(a) or Hispanic origin or decent. The majority are married (57.0%) and approximately one-quarter have a low level of literacy. More than half have diabetes (57.1%) and mean baseline SBP of 143.6mmHg). Detailed baseline characteristics by arm can be found in Table 7. The two arms were similar at baseline.

Table 7.

Baseline Study Characteristics.

| Overall N = 385 |

TDM intervention N = 192 |

Control N = 193 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.5 (8.8) | 64.2 (9.0) | 62.9 (8.5) |

| Gender, observed | |||

| Male | 356 (92.5) | 176 (91.7) | 180 (93.3) |

| Female | 29 (7.5) | 16 (8.3) | 13 (6.7) |

| Marital statusd | |||

| Married | 219 (57.0) | 115 (60.2) | 104 (53.9) |

| Living together, committed relationship |

6 (1.6) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.1) |

| Divorced/separated | 110 (28.6) | 50 (26.2) | 60 (31.1) |

| Widowed | 17 (4.4) | 8 (4.2) | 9 (4.7) |

| Single, never married | 32 (8.3) | 16 (8.4) | 16 (8.3) |

| Latino(a) or Hispanic origin/descentd |

|||

| Yes | 13 (3.4) | 9 (4.8) | 4 (2.1) |

| No | 366 (96.6) | 179 (95.2) | 187 (97.9) |

| Raced | |||

| White | 129 (33.8) | 68 (35.6) | 61 (31.9) |

| Black | 236 (61.8) | 111 (58.1) | 125 (65.4) |

| Other | 17 (4.5) | 12 (6.3) | 5 (2.6) |

| Highest level of education | |||

| Less than high school graduate | 27 (7.0) | 14 (7.3) | 13 (6.7) |

| High school graduate or GED | 108 (28.1) | 60 (31.3) | 48 (24.9) |

| Some college or technical school | 160 (41.6) | 78 (40.6) | 82 (42.5) |

| College graduate | 59 (15.3) | 26 (13.5) | 33 (17.1) |

| Post college education | 31 (8.1) | 14 (7.3) | 17 (8.8) |

| REALMd | |||

| Less than 60 | 93 (24.5) | 40 (21.3) | 53 (27.7) |

| 60 or more | 286 (75.5) | 148 (78.7) | 138 (72.3) |

| Household financial situationd | |||

| After paying the bills, you still have enough money for special things that you want |

142 (37.3) | 74 (38.9) | 68 (35.6) |

| You have enough money to pay the bills, but little spare money to buy extra or special things |

155 (40.7) | 68 (35.8) | 87 (45.5) |

| You have money to pay the bills, but only because you have to cut back on things |

47 (12.3) | 27 (14.2) | 20 (10.5) |

| You are having difficulty paying the bills, no matter what you do |

37 (9.7) | 21 (11.1) | 16 (8.4) |

| Current living situation | |||

| Own home/apartment | 364 (94.5) | 184 (95.8) | 180 (93.3) |

| No stable residence | 21 (5.5) | 8 (4.2) | 13 (6.7) |

| Blood relative(s) with high blood pressure |

|||

| Yes | 305 (79.2) | 150 (78.1) | 155 (80.3) |

| No | 36 (9.4) | 16 (8.3) | 20 (10.4) |

| Don’t know | 44 (11.4) | 26 (13.5) | 18 (9.3) |

| Ever smoked or used tobacco products |

|||

| Yes | 283 (73.5) | 142 (74.0) | 141 (73.1) |

| No | 102 (26.5) | 50 (26.0) | 52 (26.9) |

| Smoked or used tobacco products in past 6 monthsd |

|||

| Yes | 108 (28.1) | 49 (25.7) | 59 (30.6) |

| No | 276 (71.9) | 142 (74.3) | 134 (69.4) |

| Current smokerd | |||

| Yes | 94 (24.5) | 45 (23.6) | 49 (25.4) |

| No | 290 (75.5) | 146 (76.4) | 144 (74.6) |

| Diabetes | |||

| Yes | 220 (57.1) | 109 (56.8) | 111 (57.5) |

| No | 165 (42.9) | 83 (43.2) | 82 (42.5) |

| Satisfied with BP controla,d, mean (SD) |

6.2 (2.8) | 6.1 (2.7) | 6.2 (2.8) |

| Average systolic BPb, mean (SD) | 143.6 (17.6) | 143.5 (17.7) | 143.7 (17.5) |

| Average diastolic BPb, mean (SD) | 79.9 (13.6) | 79.4 (14.6) | 80.3 (12.4) |

| Systolic BP statuse | |||

| Significantly out of control | 180 (46.8) | 88 (45.8) | 92 (47.7) |

| Moderately out of control | 115 (29.9) | 57 (29.7) | 58 (30.1) |

| In control | 90 (23.4) | 47 (24.5) | 43 (22.3) |

| Have someone to help with tasks, if neededd |

|||

| Yes | 337 (88.2) | 163 (85.3) | 174 (91.1) |

| No | 45 (11.8) | 28 (14.7) | 17 (8.9) |

| Medication adherence on modified BP medication adherencec |

|||

| Non-adherent | 164 (42.6) | 82 (42.7) | 82 (42.5) |

| Adherent | 221 (57.4) | 110 (57.3) | 111 (57.5) |

| Health professionals control my healthd |

|||

| Strongly agree | 66 (17.2) | 37 (19.4) | 29 (15.1) |

| Agree | 148 (38.6) | 73 (38.2) | 75 (39.1) |

| Disagree | 131 (34.2) | 60 (31.4) | 71 (37.0) |

| Strongly disagree | 38 (9.9) | 21 (11.0) | 17 (8.9) |

SD = standard deviation, BP = blood pressure, REALM = Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine

Note. n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Scale of 1–10, with 1 = definitely not satisfied and 10 = definitely satisfied

Average of three blood pressure measurements taken at baseline

Assessed using Morisky self-reported adherence measure. A positive response to at least one question indicated non-adherence.

Missing data: note, unless otherwise indicated, responses of ‘don’t know’ or ‘refused’ were considered missing. Information is missing as follows: marital status-1, race-3, Latino(a)/Hispanic origin- 6, household finances-4, smoker, current and 6mo-1, satisfaction with blood pressure control-1, REALM-6, Help with tasks- 3, Health professionals control my health-2

Significantly out of control: systolic BP ≥ 140 for diabetics and ≥ 150 for those without diabetes; Moderately out of control: systolic BP ≥ 130 for diabetics and ≥ 140 for those without diabetes; In control: systolic BP < 130 for diabetics and < 140 for those without diabetes

4.0. Discussion

The TDM Trial is a pragmatic trial designed to test interventions in “real world” practices so that, if effective, they can be more rapidly implemented. In this particular study intervention patients have the intensity of their care titrated based upon their BP control.40–42 By reserving the most intensive and expensive strategies to veterans with greatest clinical need, this titrated strategy can potentially lead to more efficient use of resources. Our study of how to best and most efficiently allocate disease management resources will provide critical evidence about increasing access to enhanced primary care required under the VA patient-aligned care team (PACT) model, the VA’s version of the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH).43–45 Further, the study will provide evidence concerning whether the titrated disease management process may be used as a method for healthcare systems to enhance the allocation of scarce resources.

The TDM Trial recognizes that LPNs, RNs, and clinical pharmacists have varying scopes of practice, as well as differing salaries. LPNs [known as licensed vocational nurses (LVNs) in California and Texas] differ from RNs in several important dimensions. While both are nurses, LPNs focus on providing specified services under the direction of another licensed clinician, often a RN. While RNs can assess patients and develop plans for nursing care, LPNs cannot independently assess and take action in relation to patient care. As we have done, LPNs complete assigned patient care tasks, observe patients, and report observations to other clinicians. Further, RNs have training in areas such as educating patients about health issues. As a result of their greater responsibilities and time in training, RNs are paid significantly more than LPNs.46, 47

Clinical pharmacists have been studied as part of clinical teams managing hypertension to improve BP control.7, 48 They are trained in medication management and, in that role, can provide clinical assessments of patients. In the VA and many states, clinical pharmacists can directly prescribe medications within their scope of practice. Even in settings where prescribing is not permitted pharmacists can recommend pharmaceutical management to prescribing providers. However, there are far fewer clinical pharmacists than nurses available to participate in disease and self-management programs in most clinical settings, making use or RNs and LPNs appealing, when clinically appropriate. Additionally, clinical pharmacists have significantly higher salaries due to their greater scope of practice.

The TDM Trial is testing a disease management program that 1) matches the resources intensity and skill set of clinicians to the clinical needs of patients and 2) allows the intensity to be adjusted up or down over the course of the program. The strategy is appealing because most health systems do not have the human resources necessary to provide the highest intensity resources to all patients who could potentially benefit from disease management programs and patients’ clinical needs likely vary over time. Finally, the decision was made to test the intervention against a type of non-tailored telephone intervention that has been previously shown to improve blood pressure control because we believed that organizations would need to see superiority over such a low intensity program to consider the potential for utilizing resources to implement a TDM approach.

The TDM Trial has limitations and considerations that may impact the study. The participants are predominantly older men, which reflects the VA population as a whole.49 Further, the trial is being conducted among patients receiving primary care from one of four locations affiliated with only one VA medical center. Although our participants are racially diverse and are socioeconomically vulnerable, these factors limit generalizability. Second, we did not have the study personnel needed to maintain blinding among those collecting study outcomes. However, baseline outcomes were obtained before randomization, and we used a standardized protocol for measuring BP and implemented procedures to audit and maintain data quality. These processes have been employed to reduce the potential of bias resulting from the inability to maintain blinding during the study. Third, we lack the resources to examine whether any differences in results will continue after the study ends. However, we recently evaluated clinical benefits of calls similar to those in the TDM Trial and home BP monitoring after the trial concluded. The positive effect of the intervention, which did not include titration of resource intensity, was sustained 18 months following study conclusion50 Finally, we were not able to maintain our original goal of only including patients who had uncontrolled SBP at baseline. In the final sample, 23.4% of patients had blood pressure under control based on measurements collected at the baseline study visit.

5.0. Conclusion

The TDM Trial is a pragmatic health services research clinical trial testing an 18-month intervention titrating the resource intensity of disease management based on the clinical status of patients. The 385 individuals randomized in the trial represent a diverse group of veterans treated by the VA. The VA, like all healthcare organizations, must make the best use of available resources to enhance the health of those who receive care within the system. The TDM Trial will provide additional evidence concerning how to organize population-health interventions to lead to maximum benefit of patients.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. This research is supported by the Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Service of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) [IIR 10-383]. Drs. Bosworth (RCS 08-027) and Weinberger (RCS 91-408) are supported by Senior Research Career Scientist awards from the VA HSR&D Service. We also thank P. Michael Ho, MD, Ph.D., who is a study investigator and will focus on efforts to encourage implementation of the intervention in the VA, if successful.

References

- 1.Gu Q, Burt VL, Dillon CF, Yoon S. Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among United States adults with hypertension: the National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001 to 2010. Circulation. 2012 Oct 23;126(17):2105–2114. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016 Jan 26;133(4):e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillespie CD, Hurvitz KA Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Prevalence of hypertension and controlled hypertension - United States, 2007–2010. MMWR Suppl. 2013 Nov 22;62(3):144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002 Oct 16;288(15):1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai AC, Morton SC, Mangione CM, Keeler EB. A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illnesses. Am J Manag Care. 2005 Aug;11(8):478–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damush TM, Jackson GL, Powers BJ, et al. Implementing evidence-based patient self-management programs in the Veterans Health Administration: perspectives on delivery system design considerations. J Gen Intern. Med. 2010 Jan;25(Suppl 1):68–71. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1123-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter BL, Bosworth HB, Green BB. The hypertension team: the role of the pharmacist, nurse, and teamwork in hypertension therapy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012 Jan;14(1):51–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stellefson M, Dipnarine K, Stopka C. The chronic care model and diabetes management in US primary care settings: a systematic review. Prev Chronic. Dis. 2013;10:E26. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014 Feb 5;311(5):507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radin AM, Black HR. Hypertension in the elderly: the time has come to treat. J Am Geriatr. Soc. 1981 May;29(5):193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1981.tb01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Von Korff M, Tiemens B. Individualized stepped care of chronic illness. West J. Med. 2000 Feb;172(2):133–137. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McFarland KF. Type 2 diabetes: stepped-care approach to patient management. Geriatrics. 1997 Oct;52(10):22–26. 35, 39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern. Med. 1997 Dec 15;127(12):1097–1102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laragh JH. Modification of stepped care approach to antihypertensive therapy. Am J. Med. 1984 Aug 20;77(2A):78–86. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(84)80062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Dudley T, et al. Patient education and provider decision support to control blood pressure in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2009 Mar;157(3):450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bosworth HB, DuBard CA, Ruppenkamp J, Trygstad T, Hewson DL, Jackson GL. Evaluation of a self-management implementation intervention to improve hypertension control among patients in Medicaid. Translational Behav. Med. doi: 10.1007/s13142-010-0007-x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003 May 21;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JW, Bosworth HB, Voils CI, et al. How well do clinic-based blood pressure measurements agree with the mercury standard? J Gen Intern. Med. 2005 Jul;20(7):647–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woolf B. Customer Specific Marketing. New York, NY: Rand McNally; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Prog Behav Modif. 1992;28:183–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bosworth HB, Voils CI. Theoretical models to understand treatment adherence. In: Bosworth HB, Oddone EZ, Weinberger M, editors. Patient Treatment Adherence: Concepts, Interventions, and Measurement. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 13–48. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eraker SA, Kirscht JP, Becker MH. Understanding and improving patient compliance. Ann Intern. Med. 1984 Feb;100(2):258–268. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-2-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosworth HB, Oddone EZ. A model of psychosocial and cultural antecedents of blood pressure control. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002 Apr;94(4):236–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology & Health. 1998;13:623–649. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A, Adams NE, Beyer J. Cognitive processes mediating behavioral change. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1977 Mar;35(3):125–139. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.35.3.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002 Nov 20;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001 Nov;39(11):1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J. Med. 2008 Jun 12;358(24):2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melnyk SD, Zullig LL, McCant F, et al. Telemedicine cardiovascular risk reduction in veterans. Am Heart J. 2013 Apr;165(4):501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Larson MG, O'Donnell CJ, Roccella EJ, Levy D. Differential control of systolic and diastolic blood pressure : factors associated with lack of blood pressure control in the community. Hypertension. 2000 Oct;36(4):594–599. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002 Dec 14;360(9349):1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strandberg TE, Pitkala K. What is the most important component of blood pressure: systolic, diastolic or pulse pressure? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2003 May;12(3):293–297. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200305000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryson CL, Au DH, Young B, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. A refill adherence algorithm for multiple short intervals to estimate refill compliance (ReComp) Med Care. 2007 Jun;45(6):497–504. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180329368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thorpe CT, Bryson CL, Maciejewski ML, Bosworth HB. Medication acquisition and self-reported adherence in veterans with hypertension. Med Care. 2009 Apr;47(4):474–481. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e31818e7d4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Statistical principles for clinical trials. International Conference on Harmonisation E9 Expert Working Group. Stat. Med. 1999 Aug 15;18(15):1905–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzmaurice G, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. New York, NY: Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borm GF, Fransen J, Lemmens WA. A simple sample size formula for analysis of covariance in randomized clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;60(12):1234–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roland M, Torgerson DJ. What are pragmatic trials? BMJ. 1998 Jan 24;316(7127):285. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7127.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 May;62(5):464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maclure M. Explaining pragmatic trials to pragmatic policymakers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 May;62(5):476–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263–e272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bidassie B, Davies ML, Stark R, Boushon B. VA Experience in Implementing Patient-Centered Medical Home Using a Breakthrough Series Collaborative. J Gen Intern. Med. 2014 Jul;29(Suppl 2):563–571. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2773-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nelson KM, Helfrich C, Sun H, et al. Implementation of the Patient-Centered Medical Home in the Veterans Health Administration: Associations With Patient Satisfaction, Quality of Care, Staff Burnout, and Hospital and Emergency Department Use. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014 Jun 23; doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.NCIOM. Task Force on the North Carolina Nursing Workforce. Durham, NC: North Carolina Institute of Medicine; 2004. May, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beverage PA. How LPNs can be part of the solution. N C Med J. 2004 Mar-Apr;65(2):96–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santschi V, Chiolero A, Burnand B, Colosimo AL, Paradis G. Impact of pharmacist care in the management of cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Intern. Med. 2011 Sep 12;171(16):1441–1453. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hausmann LR, Gao S, Mor MK, Schaefer JH, Jr, Fine MJ. Understanding racial and ethnic differences in patient experiences with outpatient health care in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. Med Care. 2013 Jun;51(6):532–539. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318287d6e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maciejewski ML, Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, et al. Do the Benefits of Participation in a Hypertension Self-Management Trial Persist After Patients Resume Usual Care? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014 Mar 11; doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bosworth HB, Powers BJ, Olsen MK, et al. Can home blood pressure management improve blood pressure control: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern. Med. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.276. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr. Soc. 1975 Oct;23(10):433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Tierney WM. Documentation and evaluation of cognitive impairment in elderly primary care patients. Ann Intern. Med. 1995 Mar 15;122(6):422–429. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-6-199503150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanlon JT, Horner RD, Schmader KE, et al. Benzodiazepine use and cognitive function among community-dwelling elderly. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998 Dec;64(6):684–692. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Goldstein MK, et al. The veterans' study to improve the control of hypertension (V-STITCH): design and methodology. Contemp Clin Trials. 2005 Apr;26(2):155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nicolucci A, Carinci F, Ciampi A. Stratifying patients at risk of diabetic complications: an integrated look at clinical, socioeconomic, and care-related factors. SID-AMD Italian Study Group for the Implementation of the St. Vincent Declaration. Diabetes Care. 1998 Sep;21(9):1439–1444. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jamerson K, DeQuattro V. The impact of ethnicity on response to antihypertensive therapy. Am J. Med. 1996 Sep 30;101(3A):22S–32S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tuck ML. Role of salt in the control of blood pressure in obesity and diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 1991 Jan;17(1 Suppl):I135–I142. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.1_suppl.i135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hutchinson RG, Watson RL, Davis CE, et al. Racial differences in risk factors for atherosclerosis. The ARIC Study. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities. Angiology. 1997 Apr;48(4):279–290. doi: 10.1177/000331979704800401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Svetkey LP, George LK, Tyroler HA, Timmons PZ, Burchett BM, Blazer DG. Effects of gender and ethnic group on blood pressure control in the elderly. Am J Hypertens. 1996 Jun;9(6):529–535. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(96)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kornitzer M, Dramaix M, De Backer G. Epidemiology of risk factors for hypertension: implications for prevention and therapy. Drugs. 1999 May;57(5):695–712. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooper R, Rotimi C. Hypertension in populations of West African origin: is there a genetic predisposition? J Hypertens. 1994 Mar;12(3):215–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Svetkey LP, Moore TJ, Simons-Morton DG, et al. Angiotensinogen genotype and blood pressure response in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) study. J Hypertens. 2001 Nov;19(11):1949–1956. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moore TJ, Conlin PR, Ard J, Svetkey LP. DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet is effective treatment for stage 1 isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2001 Aug;38(2):155–158. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J. Med. 2001 Jan 4;344(1):3–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003 Nov;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Grafe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2) J Psychosom. Res. 2005 Feb;58(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986 Jan;24(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Gentry P, et al. Nurse administered telephone intervention for blood pressure control: a patient-tailored multifactorial intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2005 Apr;57(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003 Aug;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam. Med. 1993 Jun;25(6):391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life. Res. 2013 Sep;22(7):1717–1727. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) Med Care. 2005 May;43(5):436–444. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160375.47920.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Glasgow RE, Whitesides H, Nelson CC, King DK. Use of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) with diabetic patients: relationship to patient characteristics, receipt of care, and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005 Nov;28(11):2655–2661. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Glasgow RE, Emont S, Miller DC. Assessing delivery of the five 'As' for patient-centered counseling. Health Promot. Int. 2006 Sep;21(3):245–255. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dal017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern. Med. 1999 Oct 5;131(7):485–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]