Abstract

The enthalpic and entropic contributions to the binding affinity of drug candidates have been acknowledged to be important determinants of the quality of a drug molecule. These quantities, usually summarized in the thermodynamic signature, provide a rapid assessment of the forces that drive the binding of a ligand. Having access to the thermodynamic signature in the early stages of the drug discovery process will provide critical information towards the selection of the best drug candidates for development. In this paper, the Enthalpy Screen technique is presented. The enthalpy screen allows fast and accurate determination of the binding enthalpy for hundreds of ligands. As such, it appears to be ideally suited to aid in the ranking of the hundreds of hits that are usually identified after standard high throughput screening.

Introduction

The binding energy (ΔG) is composed of enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (−TΔS) components:

| (1) |

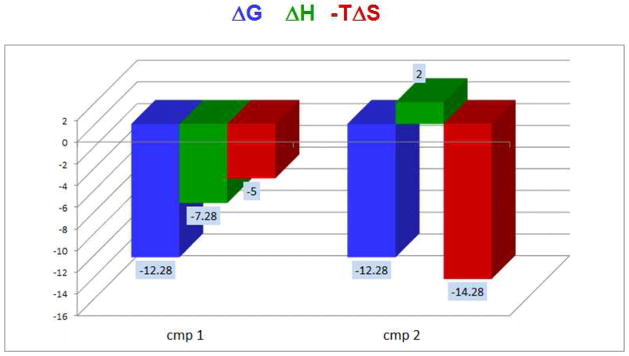

Since the enthalpic and entropic components reflect different types of interactions, it has been acknowledged that the proportion by which the enthalpy and entropy changes contribute to the total binding energy is a critical determinant of important drug properties [1–8]. A favorable binding enthalpy is associated with the presence of strong hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions between ligand and protein [9, 10]. On the contrary, an unfavorable binding enthalpy usually reflects the unproductive desolvation of polar groups; i.e. polar groups that become buried within the protein without establishing good hydrogen bonds [11, 12]. A favorable entropy, on the other hand, is associated with the desolvation of nonpolar groups (hydrophobic effect) and also polar groups [11, 12]. An unfavorable binding entropy is usually associated with structuring or refolding like the one observed in the binding of ligands to intrinsically disordered domains [13]. A convenient representation of the enthalpic and entropic contributions to the binding energy is the thermodynamic signature determined by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Figure 1 illustrates the thermodynamic signatures of two hypothetical compounds that bind with the same affinity (Kd = 1nM) but different enthalpic/entropic balance. In this example, compound 1 binds with favorable enthalpy whereas compound 2 does not. A favorable binding enthalpy is indicative of strong hydrogen bonding interactions. Since strong hydrogen bonds need to satisfy stringent distance and geometric constraints, they contribute not only to affinity but also to selectivity [14]. It has been shown that strong hydrogen bonds that do not contribute to affinity (due to significant enthalpy/entropy compensation) do contribute significantly to selectivity [14]. The lipohilic efficiency (LipE) has been acknowledged as a good indicator of the quality of a drug candidate, as it reflects the proportion of the binding affinity that cannot be attributed to hydrophobicity [15]. Different studies indicate that high quality drug candidates are characterized by high LipE and that LipE is correlated with the binding enthalpy of the compounds [16, 17].

Figure 1.

Hypothetical situation for two ligands that exhibit the same binding affinity but different thermodynamic signatures. The binding of cmp1 is characterized by favorable enthalpy and entropy whereas the binding of cmp2 is entropically driven and characterized by unfavorable enthalpy. The thermodynamic signatures of cmp1 and cmp2 reflect that the binding is controlled by different types of molecular interactions. Even though the affinity is the same under the measuring conditions, their response to changes in the environment will be different and also other drug like properties like selectivity.

Until today, thermodynamic signatures have been determined by ITC using standard calorimetric titrations. Because ITC is a low throughput technique that utilizes relatively large amounts of protein, its use in drug discovery has been relegated to the final stages of the development process, when only a handful of compounds remain under consideration. It would be a significant development if the thermodynamic signatures could be determined up front, immediately after a primary screen. In standard high throughput screening (HTS) campaigns, tens of thousands of compounds are tested, usually resulting in few hundred hits with activity in the low micromolar range. The resulting hits need to be confirmed, classified and the top compounds selected for further development. Having the ability to determine the thermodynamic signature of those hundreds hits at this stage of the process, will greatly improve the criteria for selecting the best candidates. In this paper, we present a technique denominated Enthalpy Screen that allows a fast and accurate calorimetric determination of the binding enthalpy of a large number of compounds. These binding enthalpies can be combined with Kd, Ki or IC50 values measured by other techniques in order to approximate the thermodynamic signature of the hits obtained by HTS.

Materials and Methods

Materials

HIV-1 protease was expressed and purified as described elsewhere [12, 18]. The active protease concentration used in these experiments was 88%, determined by active site titration as described before [19, 20]. The experimental inhibitors KNI-10769, KNI-577, KNI-272, KNI-10265 KNI-10074, KNI-10033, KNI-10006, KNI-764, KNI-10075 were kindly provided by Prof. Y. Kiso (Kyoto Pharmaceutical University, Kyoto, Japan). The clinical inhibitors amprenavir and indinavir were obtained from the NIH AIDS reagent program. The stock solutions of inhibitors were prepared in 100% DMSO at concentrations of 10 – 20 mM.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

All calorimetric experiments were carried out using an Affinity ITC from TA Instruments (New Castle, DE) equipped with auto sampler. This instrument allows automatic enthalpy screening of up to 96 compounds. All experiments were carried out in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0, with 2% DMSO. The auto sampler uses the solutions in one 96-well plate to fill the calorimetric reaction cell and the solutions in another 96-well plate to fill the injection syringe. The 96-well plates can be kept at constant temperature anywhere from 4 – 22°C. For these experiments the 96-well plates temperature was kept at 20°C. For the enthalpy screen the first well (A1) in the plate designated to contain the solutions for the calorimetric cell was filled with 630 μL of buffer and wells A2–A12 were filled with 630 μL of the different inhibitor solutions. The concentration of the inhibitors was 100 μM except for KNI-10006 which was prepared at 60 μM because of its lower solubility.

Although the actual volume of the calorimetric cell is less than 200 μL, 630 μL is loaded into each well as the auto sampler uses an excess volume to fill the cell without introducing air. A single well in the 96-well plate designated for filling of the syringe was filled with 305 μL of 50 μM HIV-1 protease. The instrument was programmed to make an initial 0.5 μL injection followed by three injections of 2 μL of the HIV-1 protease solution into the calorimetric cell. The smaller first injection smaller is standard in titration calorimetry and minimizes the effect of any diffusion out of the syringe during experiment preparation. The instrument software allows this small injection to be programmed to take place during the equilibration time, which speeds up the screen significantly. The well containing only buffer was used for the determination of the heat of dilution/injection of the protease. Injections were made at 1 μL/s at intervals of 200 s and the stirring speed was 200 rpm. All measurements were made at 25 °C.

Results and Discussion

Enthalpy Screen

The main goal of the enthalpy screen is to accurately measure the binding enthalpy of a large number of compounds in a fast and efficient way, using small amounts of protein. The basic implementation of the enthalpy screen involves injecting a small amount of protein into an excess concentration of ligand in the ITC reaction cell, such that all the injected protein binds to the ligand. Under those conditions, the binding enthalpy is simply the heat associated with the reaction divided by the amount of injected protein and can be determined without any data fitting to a binding model. The required excess inhibitor concentration that is needed in the enthalpy screen can be estimated from the Kd of the ligand. As a rule of thumb, if the ligand concentration is 10×Kd, 90% of the protein will bind and if the ligand concentration is 100×Kd, 99% of the protein will bind.

A typical enthalpy screen experiment involves the following steps: 1) The injection syringe is filled with protein solution (250 μL); 2) The reaction cell is filled with the first compound (400 μL); 3) Protein injections are performed (in this paper three consecutive 2 μL injections spaced 200 seconds were made) and the associated heat measured; 4) The reaction cell is emptied, cleaned and filled with the next compound; 5) The procedure is repeated until the last compound has been measured; 6) In one of the steps (usually the first) the reaction cell is filled with only buffer and no ligand in order to determine the heat of dilution of the protein. Since the volume of the injection syringe is 250 μL, up to 125 2 μL injections can be made.

The inhibitor concentrations used in the experiments presented here were more than 100-fold larger than their Kd-values, which ensures >99% saturation of the protease with inhibitor upon each injection. In general, not all compounds need to be at the same concentration, as the required concentration depends on Kd. If Kd, is not known the required concentration can be calculated from the Ki or IC50 determined in the standard screen. This approach could be important for high affinity low solubility compounds. The enthalpy of binding was calculated according to the following equation:

| (2) |

where QInh and QBuf are the heats obtained from the injections of protease into inhibitor solution and into buffer alone, respectively; VInj is the injection volume and [P] is the concentration of active HIV-1 protease. Figure 2 shows the ITC enthalpy screen data obtained for 2 μL injections of 50 μM HIV-1 protease into the calorimetric cell containing buffer alone and solutions of the inhibitors KNI-10769 and KNI-10006, each at a concentration of 100 μM. The experiments were performed in triplicate in order to evaluate the repeatability of each injection. In these experiments the injections were spaced 200 seconds, but judging from the prompt return to baseline, the spacing can be reduced to 100 or even fewer seconds. The average enthalpy values and the standard deviations measured for these and remaining HIV-1 protease inhibitors are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Enthalpy screen data for two HIV-1 protease inhibitors, KNI-10769 and KNI-10006. In these experiments 2 μL of 50 μM protease are injected into the reaction cell containing buffer (top row) or 100 μM inhibitor. The injection of protease into buffer provides the heat of dilution (QBuf). The interval between the injections is 200 s and the rate of injection 1 μL/s. The solution in the calorimetric cell was stirred at a constant rate of 200 rpm. The buffer was 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0, with 2% DMSO. All measurements were carried out at 25 °C.

Table 1.

Enthalpy values for inhibitor binding to HIV-1 protease*

| Inhibitor | ΔH (kcal/mol) Enthalpy Screen | ΔH (kcal/mol) Conventional ITC Titration | Kd or Ki (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| KNI-10769 | −4.5 ± 0.1 | −4.5 (a) | 12 (a) |

| KNI-577 | −4.5 ± 0.1 | −4.7 (b) | 0.2 (b) |

| KNI-272 | −5.4 ± 0.4 | −5.4 (c) | 0.17 (f) |

| KNI-10265 | −5.2 ± 0.1 | −5.4 (a) | 3.5 (a) |

| KNI-10074 | −6.1 ± 0.2 | −6.2 (a) | 0.52 (a) |

| KNI-10006 | −6.1 ± 0.3 | −6.5 (a) | 0.14 (a) |

| KNI-764 | −7.5 ± 0.3 | −7.6 (d) | 0.030 (d) |

| KNI-10033 | −8.4 ± 0.3 | −8.2 (e) | 0.013 (e) |

| KNI-10075 | −11.0 ± 0.5 | −12.1 (e) | 0.020 (e) |

| Amprenavir | −6.6 ± 0.3 | −6.9 (f) | 0.6Ki (g), 0.21Kd (f) |

| Indinavir | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 1.8 (f) | 0.56Ki (h), 0.76Kd (f) |

The quality of the data obtained from the enthalpy screen of eleven inhibitors is demonstrated in Figure 3. In this figure, the enthalpy values determined with the enthalpy screen have been plotted against previously published values [9, 10, 19–23] determined in this laboratory by standard ITC titrations under identical conditions. The enthalpy values cover a wide range, from highly exothermic (−11 kcal/mol) to endothermic compounds (2.7 kcal/mol). The average difference between binding enthalpies determined by the enthalpy screen and standard titrations is 0.3 kcal/mol and the correlation coefficient is 0.96.

Figure 3.

The correlation between the enthalpy values obtained by the enthalpy screen and the values obtained by a standard ITC titration under identical conditions. The correlation coefficient is 0.96.

It is known that if a binding process is coupled to a protonation/deprotonation reaction, the value of the measured binding enthalpy depends on the ionization enthalpy of the buffer used to perform the experiments [20, 24, 25]. In the enthalpy screen, the same situation occurs. In fact, the enthalpy screen provides the fastest and most accurate way of determining any coupling of binding to protonation/deprotonation.

The enthalpy screen allows accurate binding enthalpy measurements for a large number of compounds in an automated way, using about 5 μg of protein per compound.

The Binding Affinity and the Thermodynamic Signature

It is generally acknowledged that the gold standard to measure binding affinities is ITC; however, ITC is a low throughput technique that requires on the order of 0.1 – 0.5 mg of protein per compound. As such ITC cannot be used to measure the affinity of the hundreds of compounds routinely identified by a primary screen. However, ITC can be used to accurately measure the binding enthalpy of hundreds of compounds using the enthalpy screen technique described above. In fact, calorimetry is the only technique that measures the binding enthalpy. If the binding enthalpy is known, the thermodynamic signature of each compound can be approximated by using binding affinities measured by other methods. High throughput screening assays or other techniques (surface plasmon resonance, enzyme inhibition assays, thermophoresis, etc) provide IC50, Ki and Kd values that can be used to approximate ΔG and calculate the thermodynamic signature. If those values are known, ΔG can be approximated by:

| (3) |

And the entropic contribution (−TΔS) can be estimated by using the ΔH value measured in the enthalpy screen:

| (4) |

The binding enthalpy measured by the ITC enthalpy screen and the ΔG and −TΔS values calculated with equations 3 and 4 allows for a good approximation of the thermodynamic signature.

The binding enthalpy measured by the enthalpy screen is as accurate as the binding enthalpy determined by conventional ITC titrations. To calculate the thermodynamic signature, the additional necessary element is the entropic contribution (−TΔS) which can be estimated from a knowledge of Kd, Ki or IC50. Some techniques, like SPR are capable of measuring Kd’s accurately [26–28] and consequently provide excellent approximations to the thermodynamic signature when combined with the enthalpy screen. On the other hand, in many instances, enzyme inhibition constants or IC50’s are the only available quantities. If this is the case, Ki’s and IC50’s will only provide rough estimates of the binding affinity. Nevertheless, if the Ki or IC50 bracket the true binding affinity within a span of one order of magnitude, the average difference will be 0.68 kcal/mol as one full order of magnitude in Kd is equal to 1.36 kcal/mol at 25°C. This observation can be assessed using as an example the case of the FDA approved HIV-1 protease inhibitors indinavir and amprenavir. Indinavir is one of the first generation HIV-1 protease inhibitors with a published Ki of 0.56 nM [29] which is close to the Kd of 0.76 nM measured by ITC [6, 21]. Amprenavir is a second generation inhibitor with a published Ki of 0.6 nM [30] and a Kd of 0.2 nM determined by ITC [6, 21]. Figure 4 shows the thermodynamic signatures for indinavir and amprenavir obtained by standard ITC titration data [6] and the one obtained by combining published Ki data and the binding enthalpy obtained from the enthalpy screen. It is evident in both graphs that the binding of indinavir is entropically driven and that the binding enthalpy do not favor but opposes binding. The binding of amprenavir, on the other hand, is characterized by favorable enthalpy and entropy changes and reflected in both graphs. Except for minor differences, the thermodynamic signature approximated by the combination of enthalpy screen and Ki data provides an accurate description of the driving forces and binding character of an inhibitor.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the thermodynamic signatures for the FDA approved HIV-1 protease inhibitors indinavir and amprenavir, obtained from ITC standard titration data (Kd, ΔH, −TΔS) (left) and by combining published inhibition data (Ki) and binding enthalpy obtained from enthalpy screen (right). Despite minor numerical differences, the binding characteristics and the nature of the predominant binding forces are well defined in both cases.

Figure 5 shows the thermodynamic signatures of all the HIV-1 protease inhibitors considered in this paper. The first nine inhibitors correspond to different analogs of a single scaffold (the allophenylnorstatine or KNI scaffold originally described by Kiso [31, 32]. The thermodynamic signature obtained with the enthalpy screen discriminates between different analogs belonging to a single scaffold. It allows immediate assessment of the effects and contributions of specific chemical modifications to the affinity and the enthalpic and entropic contributions to the Gibbs energy of binding. As such, it becomes an important guide in the optimization of a lead compound.

Figure 5.

Thermodynamic signatures for eleven HIV-1 protease inhibitors. The first nine correspond to a series of allophenylnorstatine inhibitors (KNI inhibitors) and the remaining two, to indinavir and amprenavir. This data demonstrates that the thermodynamic signatures obtained with enthalpy screen data provides critical information towards the ranking and optimization of drug candidates.

Conclusions

The thermodynamic signature is a powerful tool in the characterization of the quality of a compound as a potential drug candidate. In the past, the thermodynamic signature has only been obtained in the last stages of the development process or in a retrospective fashion. The enthalpy screen described here, in combination with already available potency data (Ki, IC50) should be able to approximate the thermodynamic signature of hundreds of compounds in two or three days, thus providing this critical information at the early stages of the drug discovery process.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation MCB-1157506

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ohtaka H, Freire E. Adaptive inhibitors of the HIV-1 protease. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2005;88:193–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ladbury JE, Klebe G, Freire E. Adding calorimetric data to decision making in lead discovery: a hot tip. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:23–27. doi: 10.1038/nrd3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carbonell T, Freire E. Binding thermodynamics of statins to HMG-CoA reductase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11741–11748. doi: 10.1021/bi050905v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarver RW, Peevers J, Cody WL, Ciske FL, Dyer J, Emerson SD, Hagadorn JC, Holsworth DD, Jalaie M, Kaufman M, Mastronardi M, McConnell P, Powell NA, Quin J, 3rd, Van Huis CA, Zhang E, Mochalkin I. Binding thermodynamics of substituted diaminopyrimidine renin inhibitors. Anal Biochem. 2007;360:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaires JB. Calorimetry and thermodynamics in drug design. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:135–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freire E. Do enthalpy and entropy distinguish first in class from best in class? Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:869–874. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruben AJ, Kiso Y, Freire E. Overcoming roadblocks in lead optimization: a thermodynamic perspective. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;67:2–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2005.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freire E. A thermodynamic approach to the affinity optimization of drug candidates. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74:468–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lafont V, Armstrong AA, Ohtaka H, Kiso Y, Mario Amzel L, Freire E. Compensating enthalpic and entropic changes hinder binding affinity optimization. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2007;69:413–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawasaki Y, Chufan EE, Lafont V, Hidaka K, Kiso Y, Mario Amzel L, Freire E. How much binding affinity can be gained by filling a cavity? Chem Biol Drug Des. 2010;75:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabani S, Gianni P, Mollica V, Lepori L. Group contributions to the thermodynamic properties of non-ionic organic solutes in dilute aqueous solution. Journal of Solution Chemistry. 1981;10:563–595. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luque I, Todd MJ, Gomez J, Semo N, Freire E. Molecular basis of resistance to HIV-1 protease inhibition: a plausible hypothesis. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5791–5797. doi: 10.1021/bi9802521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schon A, Madani N, Klein JC, Hubicki A, Ng D, Yang X, Smith AB, 3rd, Sodroski J, Freire E. Thermodynamics of binding of a low-molecular-weight CD4 mimetic to HIV-1 gp120. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10973–10980. doi: 10.1021/bi061193r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawasaki Y, Freire E. Finding a better path to drug selectivity. Drug Discov Today. 2011;16:985–990. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryckmans T, Edwards MP, Horne VA, Correia AM, Owen DR, Thompson LR, Tran I, Tutt MF, Young T. Rapid assessment of a novel series of selective CB2 agonists using parallel synthesis protocols: A Lipophilic Efficiency (LipE) analysis. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2009;19:4406–4409. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freire E. Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Drug Binding. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2015. The Binding Thermodynamics of Drug Candidates; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shultz MD. The thermodynamic basis for the use of lipophilic efficiency (LipE) in enthalpic optimizations. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:5992–6000. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Todd MJ, Luque I, Velazquez-Campoy A, Freire E. Thermodynamic basis of resistance to HIV-1 protease inhibition: calorimetric analysis of the V82F/I84V active site resistant mutant. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11876–11883. doi: 10.1021/bi001013s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velazquez-Campoy A, Kiso Y, Freire E. The binding energetics of first- and second-generation HIV-1 protease inhibitors: implications for drug design. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;390:169–175. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velazquez-Campoy A, Luque I, Todd MJ, Milutinovich M, Kiso Y, Freire E. Thermodynamic dissection of the binding energetics of KNI-272, a potent HIV-1 protease inhibitor. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1801–1809. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohtaka H, Schon A, Freire E. Multidrug resistance to HIV-1 protease inhibition requires cooperative coupling between distal mutations. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13659–13666. doi: 10.1021/bi0350405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohtaka H, Velazquez-Campoy A, Xie D, Freire E. Overcoming drug resistance in HIV-1 chemotherapy: the binding thermodynamics of Amprenavir and TMC-126 to wild-type and drug-resistant mutants of the HIV-1 protease. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1908–1916. doi: 10.1110/ps.0206402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vega S, Kang LW, Velazquez-Campoy A, Kiso Y, Amzel LM, Freire E. A structural and thermodynamic escape mechanism from a drug resistant mutation of the HIV-1 protease. Proteins. 2004;55:594–602. doi: 10.1002/prot.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker BM, Murphy KP. Evaluation of linked protonation effects in protein binding reactions using isothermal titration calorimetry. Biophys J. 1996;71:2049–2055. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomez J, Freire E. Thermodynamic mapping of the inhibitor site of the aspartic protease endothiapepsin. J Mol Biol. 1995;252:337–350. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rich RL, Myszka DG. Higher-throughput, label-free, real-time molecular interaction analysis. Anal Biochem. 2007;361:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rich RL, Day YS, Morton TA, Myszka DG. High-resolution and high-throughput protocols for measuring drug/human serum albumin interactions using BIACORE. Anal Biochem. 2001;296:197–207. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navratilova I, Papalia GA, Rich RL, Bedinger D, Brophy S, Condon B, Deng T, Emerick AW, Guan HW, Hayden T, Heutmekers T, Hoorelbeke B, McCroskey MC, Murphy MM, Nakagawa T, Parmeggiani F, Qin X, Rebe S, Tomasevic N, Tsang T, Waddell MB, Zhang FF, Leavitt S, Myszka DG. Thermodynamic benchmark study using Biacore technology. Anal Biochem. 2007;364:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brik A, Wu CY, Wong CH. Microtiter plate based chemistry and in situ screening: a useful approach for rapid inhibitor discovery. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 2006;4:1446–1457. doi: 10.1039/b600055j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadler BM, Stein DS. Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacokinetics of Amprenavir. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2002;36:102–118. doi: 10.1345/aph.10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mimoto T, Kato R, Takaku H, Nojima S, Terashima K, Misawa S, Fukazawa T, Ueno T, Sato H, Shintani M, Kiso Y, Hayashi H. Structure-activity relationship of small-sized HIV protease inhibitors containing allophenylnorstatine. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1789–1802. doi: 10.1021/jm980637h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiso Y. Design and synthesis of a covalently linked HIV-1 protease dimer analog and peptidomimetic inhibitors. J Synthetic Org Chem (Jpn) 1998;56:32–43. [Google Scholar]