Abstract

The optimal second- and third-line chemotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with advanced esophagogastric cancer is still a matter of debate. Therefore, a literature search was carried out in Medline, EMBASE, CENTRAL, and oncology conferences until January 2016 for randomized controlled trials that compared second- or third-line therapy. We included 28 studies with 4810 patients. Second-line, single-agent taxane/irinotecan showed increased survival compared to best supportive care (BSC) (hazard ratio 0.65, 95 % confidence interval 0.53–0.79). Median survival gain ranged from 1.4 to 2.7 months among individual studies. Taxane- and irinotecan-based regimens showed equal survival benefit. Doublet chemotherapy taxane/irinotecan plus platinum and fluoropyrimidine was not different in survival, but showed increased toxicity vs. taxane/irinotecan monotherapy. Compared to BSC, second-line ramucirumab and second- or third-line everolimus and regorafenib showed limited median survival gain ranging from 1.1 to 1.4 months, and progression-free survival gain, ranging from 0.3 to 1.6 months. Third- or later-line apatinib showed increased survival benefit over BSC (HR 0.50, 0.32–0.79). Median survival gain ranged from 1.8 to 2.3 months. Compared to taxane-alone, survival was superior for second-line ramucirumab plus taxane (HR 0.81, 0.68–0.96), and olaparib plus taxane (HR 0.56, 0.35–0.87), with median survival gains of 2.2 and 4.8 months respectively. Targeted agents, either in monotherapy or combined with chemotherapy showed increased toxicity compared to BSC and chemotherapy-alone. This review indicates that, given the survival benefit in a phase III study setting, ramucirumab plus taxane is the preferred second-line treatment. Taxane or irinotecan monotherapy are alternatives, although the absolute survival benefit was limited. In third-line setting, apatinib monotherapy is preferred.

Keywords: Advanced esophagogastric cancer, Chemotherapy, Targeted therapy, Second-line, Third-line, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Worldwide, advanced esophageal and gastric cancers are major causes of mortality [1]. In the first-line setting, fluoropyrimidine and platinum combinations are preferred [2]. As virtually all patients become resistant to first-line treatment, effective second- or later-line treatments are warranted. Previously, it has been shown that single-agent irinotecan and taxane as second-line chemotherapy increase survival compared to best supportive care (BSC) [3, 4]. Also, targeted agents that were shown to be active in clinical trials have been introduced into clinical practice, for example ramucirumab, a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) inhibitor [5, 6]. Although evidence for active treatments after progression on first-line (chemo)therapy has been established, to date, there are several questions that remain unanswered.

First, as “salvage” chemotherapy usually consists of irinotecan or taxane, these two strategies are generally regarded as equally effective [7]. However, a literature review to assess the possible differences in efficacy, defined as the maximum effect achievable for a drug in clinical trial setting, and safety of irinotecan and taxane is not available. Second, to increase the efficacy of second-line irinotecan or taxane single-agent chemotherapy, several trials have been conducted in which another cytotoxic agent, for example platinum or fluoropyrimidine, was added to a backbone of irinotecan or taxane. However, the results of these randomized controlled trials (RCT) are inconsistent and despite the publication of a recent systematic review [8], doublet chemotherapy compared to single chemotherapy including the newest RCTs has not been investigated in a fluoropyrimidine add-on and platinum add-on subgroup structured meta-analysis yet. Third, safety data were not included in recent reviews or meta-analyses, which makes it more difficult to put the findings into a clinical perspective [3, 4, 9]. Fourth, many small trials have been conducted with targeted agents that did not receive much attention in literature reviews or meta-analyses [10, 11] since usually only larger phase III trials have been included [5, 6, 12]. Overview of the smaller trials will help to identify the potentially most efficacious targeted agents for future studies. Fifth, in addition to second-line therapy, also third- or later-line therapy has been subject of investigation lately, but an overview is currently missing [13, 14]. Finally, usually only relative effect sizes are used in meta-analysis, which may be difficult to interpret in clinical practice. In order to enhance the clinical applicability of the findings, also a more absolute efficacy summary statistic should be incorporated into literature reviews or meta-analyses, for example the absolute median survival gain from an experimental treatment over the control treatment/best supportive care.

In sum, the evidence regarding all possible second- or third-line treatments is inadequately summarized, which may be difficult for decision-making in clinical practice. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of all currently available randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Methods

Literature search

Medline, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were searched for eligible RCTs up to January 2016. The search strategy consisted of medical subject headings (MeSH) combined with text words for esophageal and gastric cancer and with text words associated with second- or later-line therapy (Table 1). Also, the conference abstracts of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) between 1990 and January 2016 were searched. NHM and EtV screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts independently. Disagreements were discussed with a third arbiter (HvL) until consensus was reached.

Table 1.

Full search strategy

| Medline via Pubmed |

| (“stomach neoplasms” [MeSH terms] or “esophageal neoplasms” [MeSH terms]) and (((refractory [title/abstract] or previously treated [title/abstract]) or salvage treatment [title/abstract]) or second line [title/abstract]) and Clinical trial [ptyp] |

| EMBASE via Ovid |

| 1. esophagus tumor/or exp esophagus cancer |

| 2. stomach tumor/or exp stomach cancer |

| 3. ((esophag* or oesophag* or stomach or gastric or gastroesophag* or gastrooesophag*)adj5 (neoplas* or cancer* or carcino* or adenocarcino* or tumor or tumors or tumour or tumours or malig*)).ti,ab. |

| 4. refractory.mp. |

| 5. previously treated.mp |

| 6. salvage treatment.mp. |

| 7. second line.mp. |

| 8. 1 or 2 or 3 |

| 9. 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 |

| 10. exp controlled clinical trial/or randomized.ti,ab. or randomised.ti,ab. or placebo.ti,ab. or randomly.ti,ab. or trial.ti |

| 11. 8 and 9 and 10 |

| Additional filters: |

| 1. year = “2005–2016” |

| 2. not (conference abstract or conference paper or “conference review” or conference proceeding) |

| 3. articles |

| Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) |

| #1 MeSH descriptor: [esophageal neoplasms] explode all trees |

| #2 MeSH descriptor: [stomach neoplasms] explode all trees |

| #3 #1 or #2 |

| #4 (refractory): ti,ab,kw |

| #5 (previously treated): ti,ab,kw |

| #6 (salvage treatment): ti,ab,kw |

| #7 (second line): ti,ab,kw |

| #8 #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 |

| #9 #3 and #9 |

| Additional filter: trials |

| Conference search |

| Searching journal content for gastric (all words) in title or abstract and random* or advance* OR metasta* (all words) in full text, from Jan 2004 through Jan 2016 in http://www.ascopubs.org/search and http://www.annonc.oxfordjournals.org/search |

Study selection

Studies had to meet the following criteria of eligibility: (1) prospective phase II or III randomized controlled trials; (2) included patients with pathologically proven metastatic, unresectable, or recurrent adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ), or stomach; (3) patients were previously treated with systemic therapy.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The major efficacy outcome of interest was overall survival (OS), since an international expert consensus panel stated that OS as endpoint in oncology clinical trials is most appropriate [15]. Other outcomes of interest were progression-free survival (PFS) and the incidence of grade 3–4 adverse events (AEs) to assess the safety (http://ctep.cancer.gov). Two reviewers (LN and RM) were involved in data extraction; discrepancies were solved by discussion with an arbiter (EtV). The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of bias tool (version 5.1.0). Items were scored as low, high, or unknown risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

For time-to-event outcomes OS and PFS, hazard ratios (HR) with 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI), number of events or p values were extracted to calculate the logHR and standard error based on intention-to-treat study populations [16]. Also, medians were extracted to calculate the absolute median OS and PFS gain (Δmedian) in months from an experimental treatment over the control treatment arm. The Δmedians were shown for individual studies and the range of Δmedians for comparisons with multiple studies. For the comparison of grade 3–4 AEs between groups, the number of events and sample-sizes were used to calculate risk ratios (RR) and 95 % CI’s. Review Manager 5.3 was used for statistical analysis.

First, we examined the efficacy and safety of second-line chemotherapy compared to best supportive care (BSC). Second, we compared the efficacy and safety of irinotecan- and taxane-based chemotherapy regimens. Third, the efficacy and safety of combination chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy-alone was examined. Fourth, single targeted agents were compared to a reference arm of BSC. Fifth, the added value of targeted therapy to chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy-alone was examined. Finally, targeted agents for specific molecular subgroups were examined.

In case of statistical heterogeneity, as tested with the Cochran Q and quantified by the I2 index, baseline characteristics in the corresponding studies were explored and subsequent sensitivity analysis conducted by omitting the heterogeneous studies. All comparisons were tested at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

Description of the studies

A total of 423 unique references were identified in Medline, EMBASE, and CENTRAL. Of the remaining 284 reports after title/abstract screening, 8 studies were excluded based on full text. Searching conference abstracts provided five additional studies. In total, 28 studies (N = 4810 patients) were included (Fig. 1). The number of studies that scored low risk of bias on all items of the Cochrane risk of bias tool for the primary outcome was 18 (64 %) (Fig. 2a). Five studies (18 %) were reported as meeting abstract or presentation. The risk of bias assessment for PFS is summarized in Fig. 2b. All patients included in the studies received a platinum and fluoropyrimidine-based first-line chemotherapy regimen (Table 2). No major differences in sex, age, disease status and Eastern Collaborative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status were observed between the included studies, as shown in Table 2. In the majority of the studies, the inclusion was restricted to patients with an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1, as indicated in Table 2. In the following sections, recommendations about the performance status of patients to be eligible for a certain therapy are based on performance status as inclusion criterion of the specific trials (Table 2).

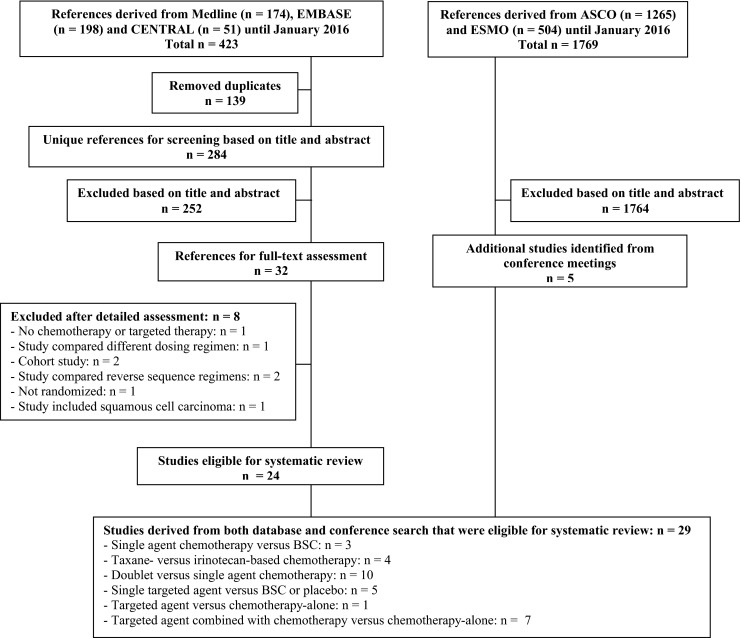

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of included studies. Flowchart of references derived from database search (left) and from conference search (right). Notes: the study of Kang and colleagues (2012) [19] was included in both the single-agent chemotherapy vs. BSC as well as the taxane- vs. irinotecan-based chemotherapy comparison

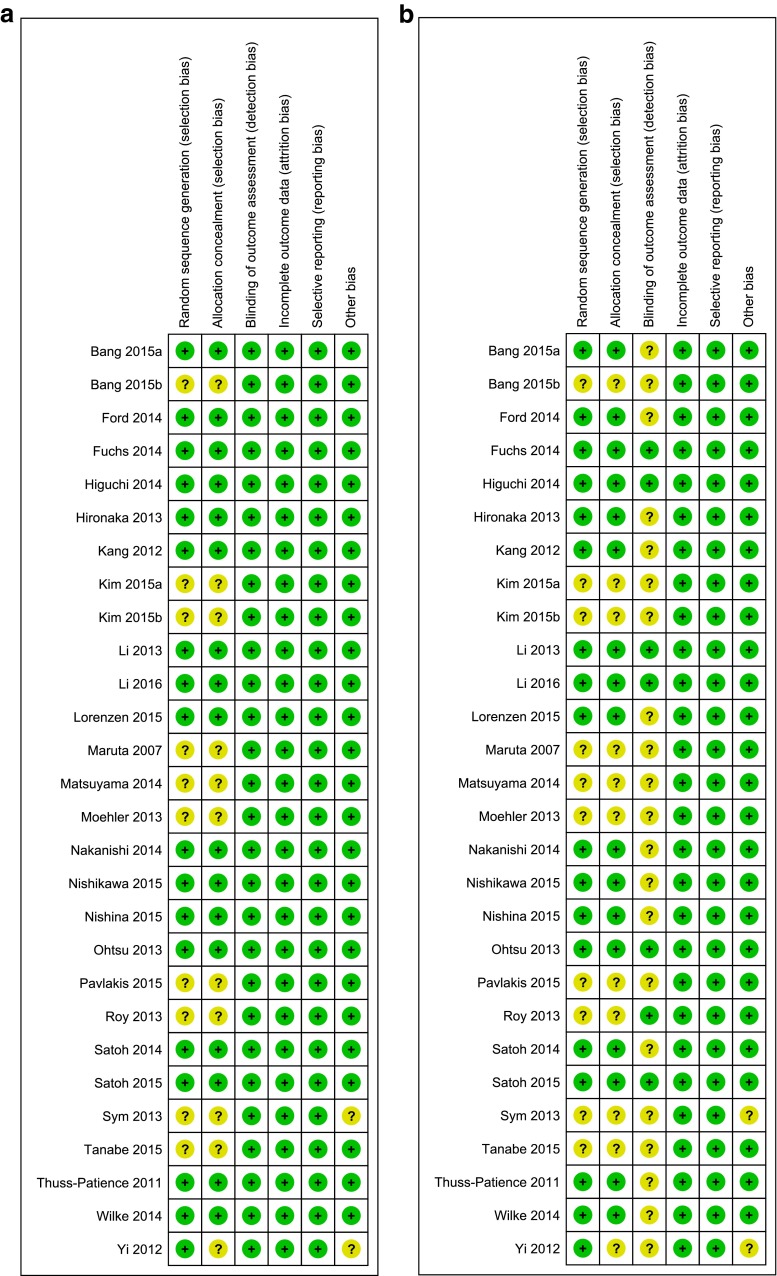

Fig 2.

Risk of bias assessment for overall survival and progression-free survival. Risk of bias assessment for the primary outcome overall survival (a) and progression-free survival (b). The green spots with a “plus sign” indicate low risk of bias on an item, whereas the yellow spots with “question mark” indicate unknown risk of bias on an item. Notes: single-center studies and studies without a published full article report were rated unclear risk of other possible bias. The absence of a description of a blinded-imaging review committee was not regarded of bias for OS, since the primary outcome OS would not be influenced by this parameter

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

| Study | N | Treatment arms | Sex male (%) | Age median (range) | Disease status metastatic (%) | ECOG PS inclusion | ECOG PS distribution | Treatment line | Prior treatment | Primary endpoint | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 (%) | 2 (%) | ||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | |||||||||||

| Ford 2014 [17] | 84 84 |

Docetaxel + BSC BSC |

69 (82) 67 (80) |

65 (29–84) 66 (36–84) |

73 (87) 74 (88) |

0–2 | 70 (83) 72 (86) |

14 (17) 12 (14) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | OS |

| Thuss-Patience 2011 [18] | 21 19 |

Irinotecan BSC |

18 (86) 11 (58) |

58 (43–73) 55 (35–72) |

21 (100) 19 (100) |

0–2 | 17 (81) 14 (74) |

4 (19) 5 (26) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum or taxane | OS |

| Kang 2012 [19] | 133 69 |

Docetaxel or irinotecan BSC |

93 (70) 44 (64) |

56 (31–83) 56 (32–74) |

133 (100) 69 (100) |

0–1 | 133 (100) 69 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

2nd or 3rd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | OS |

| Hironaka 2013 [20] | 108 111 |

Paclitaxel Irinotecan |

84 (78) 87 (78) |

65 (37–75) 65 (38–75) |

108 (100) 11 (100) |

0–2 | 104 (96) 107 (96) |

4 (4) 4 (4) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | OS |

| Nishikawa 2015a [21] | 43 42 20 22 |

Paclitaxel Irinotecan Paclitaxel + S-1 Irinotecan + S-1 |

35 (81) 30 (71) 12 (60) 15 (68) |

65 (31–74) 65 (44–74) 63 (37–74) 67 (47–73) |

NA NA NA NA |

0–2 | 41 (95) 42 (100) 20 (100) 21 (95) |

2 (5) 0 (0) 0 (0) 2 (5) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | OS |

| Roy 2013 [22] | 44 44 44 |

Docetaxel Irinotecan PEP-02 |

34 (77) 34 (77) 35 (79) |

58 (33–81) 62 (33–79) 56 (38–81) |

43 (98) 40 (91) 43 (98) |

0–2 | 40 (91) 41 (93) 41 (93) |

4 (9) 3 (7) 3 (7) |

2nd | Not specified | ORR |

| Higuchi 2014 [23] | 64 63 |

Irinotecan + cisplatin Irinotecan |

49 (77) 55 (87) |

66 (29–80) 67 (49–78) |

44 (69) 40 (63) |

0–2 | 64 (100) 63 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum or taxane | PFS |

| Nishikawa 2015b [24] | 84 84 |

Irinotecan + cisplatin Irinotecan |

68 (81) 63 (75) |

67 (36–85) 68 (35–87) |

64 (78) 71 (84) |

0–1 | 84 (100) 84 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine monotherapy | OS |

| Kim 2015a [25] | 23 25 23 |

Docetaxel + cisplatin Docetaxel + S-1 Docetaxel |

21 (87) 15 (60) 18 (78) |

55 (38–74) 55 (39–68) 56 (34–68) |

23 (100) 25 (100) 23 (100) |

0–2 | 22 (92) 23 (92) 23 (100) |

2 (8) 2 (8) 0 (0) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + cisplatin | ORR |

| Kim 2015b [26] | 25 27 |

Docetaxel + oxaliplatin Docetaxel |

18 (72) 24 (89) |

59 54 |

NA NA |

0–2 | 24 (96) 26 (96) |

1 (4) 1 (4) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + cisplatin | ORR |

| Nakanishi 2015 [27] | 38 40 |

Paclitaxel + S-1 Paclitaxel |

29 (76) 34 (85) |

64 (42–79) 62 (38–80) |

NA NA |

0–2 | 37 (97) 46 (93) |

1 (3) 3 (7) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | PFS |

| Tanabe 2015 [28] | 145 148 |

Irinotecan + S-1 Irinotecan |

99 (68) 109 (74) |

67 (37–84) 66 (22–83) |

NA NA |

0–1 | 145 (100) 148 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine-based regimen | OS |

| Sym 2013[29] | 30 29 |

Irinotecan + 5-FU/Lv Irinotecan |

14 (47) 20 (69) |

61 (30–75) 60 (45–76) |

28 (93) 27 (93) |

0–2 | 27 (90) 27 (93) |

3 (10) 2 (7) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | ORR |

| Maruta 2007 [30] | 12 12 |

Docetaxel + 5′DFUR Docetaxel |

9 (75) 9 (75) |

61 (38–74) 65 (59–71) |

NA NA |

0–2 | 11 (92) 11 (92) |

1 (8) 1 (8) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | ORR |

| Nishina 2015 [31] | 49 51 |

5-FU + methotrexate Paclitaxel |

33 (67) 36 (71) |

59 (30–74) 64 (39–75) |

49 (100) 51 (100) |

0–2 | 48 (98) 49 (96) |

1 (2) 2 (4) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + cisplatin or methotrexate | OS |

| Targeted therapy | |||||||||||

| Fuchs 2014 [5] | 238 117 |

Ramucirumab BSC |

169 (71) 79 (68) |

60 (52–67) 60 (51–71) |

NA NA |

0–1 | 238 (100) 116 (99) |

0 (0) 1 (1) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | OS |

| Ohtsu 2013 [12] | 439 217 |

Everolimus Placebo + BSC |

322 (73) 161 (74) |

62 (20–86) 62 (20–88) |

439 (100) 217 (100) |

0–2 | 413 (94) 190 (87) |

25 (6) 27 (12) |

2nd or 3rd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | OS |

| Pavlakis 2015 [32] | 97 50 |

Regorafenib BSC |

78 (80) 40 (80) |

NA NA |

NA NA |

0-1 | 97 (100) 50 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

2nd or 3rd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | PFS |

| Wilke 2014 [6] | 330 335 |

Ramucirumab + paclitaxel Paclitaxel + placebo |

229 (69) 243 (73) |

61 (25–83) 61 (24–84) |

NA NA |

0–1 | 330 (100) 335 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | OS |

| Bang 2015a [33] | 62 62 |

Olaparib + paclitaxel Paclitaxel |

49 (79) 44 (71) |

63 (31–77) 61 (26–79) |

NA NA |

0-2 | 62 (100) 60 (96.8) |

0 (0) 2 (3) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | PFS |

| Yi 2012 [11] | 56 49 |

Sunitinib + docetaxel Docetaxel |

40 (71) 33 (67) |

54 (20–72) 52 (36–70) |

47 (84) 47 (96) |

0–2 | 30 (89) 46 (94) |

6 (11) 3 (6) |

2nd or 3rd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | TTP |

| Moehler 2013 [34] | 45 46 |

Sunitinib + irinotecan + 5-FU/Lv Irinotecan + 5-FU/Lv |

NA NA |

NA NA |

NA NA |

KPS 100–70 % | NA NA |

NA NA |

2nd or 3rd | Taxane and/or platinum | PFS |

| Satoh 2015 [10] | 40 42 |

Nimotuzumab + irinotecan Irinotecan |

33 (82) 33 (79) |

60 (27–75) 63 (32–75) |

39 (97.5) 42 (100) |

0–1 | 40 (100) 42 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

2nd or 3rd | Fluoropyrimidine-based regimen | PFS |

| Bang 2015b [35] | 41 30 |

AZD-4547 Paclitaxel |

29 (71) 22 (73) |

63 62 |

NA NA |

NA | NA NA |

NA NA |

2nd or 3rd | Not specified | PFS |

| Satoh 2014 [36] | 132 129 |

Lapatinib + paclitaxel Paclitaxel |

101 (77) 106 (82) |

61 (32–79) 62 (22–80) |

127 (96) 121 (94) |

0–1 | 132 (100) 129 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + cisplatin | OS |

| Lorenzen 2015 [37] | 18 19 |

Lapatinib + capecitabine Lapatinib |

17 (94) 14 (74) |

56 (44–75) 62 (46–76) |

18 (100) 19 (100) |

0–2 | 16 (88) 18 (95) |

2 (11) 1 (5) |

2nd | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | ORR |

| Li 2013 [13] | 47 46 48 |

Apatinib 850 mg once daily Apatinib 425 mg twice daily Placebo |

39 (83) 34 (74) 36 (75) |

55 53 54 |

43 (91) 45 (98) 48 (100) |

0–1 | 47 (100) 46 (100) 48 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

3rd or later | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | PFS |

| Li 2016 [14] | 176 91 |

Apatinib 850 mg once daily Placebo + BSC |

132 (75) 69 (76) |

58 (32–71) 58 (28–70) |

NA NA |

0–1 | 176 (100) 91 (100) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

3rd or later | Fluoropyrimidine + platinum | OS |

The most important baseline characteristics of all 28 studies are shown

5-FU 5-fluorouracil, BSC best supportive care, ECOG PS Eastern Collaborative Oncology Group performance status, GEJ gastro-esophageal junction, KPS Karnofsky performance status, Lv leucovorin, NA not available, NR not reached

Single cytotoxic agent compared to best supportive care

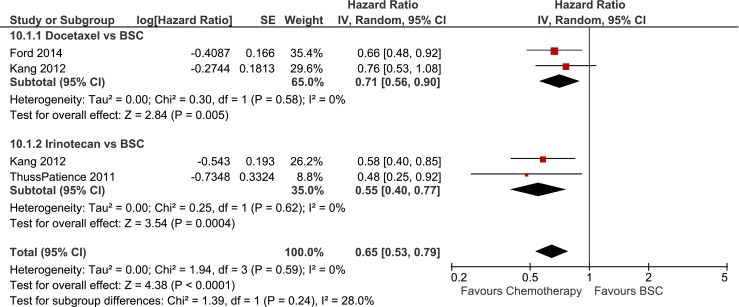

Increased overall survival was found for single cytotoxic agents vs. BSC (HR 0.65, 0.53–0.79) by meta-analysis of 3 studies including 410 patients as shown in Fig. 3 [17–19]. In subgroup analysis, increased OS was shown for both taxane (HR 0.71, 0.56–0.90) and irinotecan (HR 0.55, 0.40–0.77) compared to BSC. Absolute median survival gain ranged from Δ1.4 to Δ1.6 months for taxane compared to BSC and ranged from Δ1.6 to Δ2.7 months for irinotecan compared to BSC (Table 3). Both taxane and irinotecan were associated with statistically significant increased grade 3–4 neutropenia (33/207 vs. 2/198, RR 12.17, 3.41–43.50) and febrile neutropenia (9/100 vs. 0/91, RR 8.69, 1.14–66.42) compared to BSC.

Fig. 3.

Overall survival in studies comparing single-agent taxane and irinotecan to best supportive care. Forest-plot of single-agent taxane and irinotecan compared to best supportive care in terms of overall survival (A). BSC best supportive care, IRI irinotecan, TAX taxane, PTX paclitaxel, DTX docetaxel

Table 3.

Efficacy of second-line chemotherapy

| Study | Efficacy sample | Arms | Overall survival | Progression-free survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Median difference | HR (95 % CI) | P | Median | Median difference | HR (95 % CI) | P | |||

| Taxane/irinotecan vs. BSC | ||||||||||

| Ford 2014 [17] | 84 84 |

Docetaxel BSC |

5.2 3.6 |

Δ 1.6 | 0.66 (0.48–0.92) | *0.01 | NA NA |

NA | NA | NA |

| Thuss-Patience 2011 [18] | 21 19 |

Irinotecan BSC |

4.0 2.4 |

Δ 1.6 | 0.48 (0.25–0.92) | *0.02 | NA NA |

NA | NA | NA |

| Kang 2012 [19] | 66 60 69 |

Docetaxel Irinotecan BSC |

5.2 6.5 3.8 |

Δ 1.4 Δ 2.7 |

0.76 (0.53–1.08) 0.58 (0.40–0.85) |

0.13 *0.01 |

NA NA NA |

NA NA |

NA NA |

NA NA |

| Taxane-based vs. irinotecan-based regimens | ||||||||||

| Kang 2012 [19] | 66 60 |

Docetaxel Irinotecan |

5.2 6.5 |

Δ −1.3 | 1.31 (0.78–2.20) | 0.12 | NA NA |

NA | NA | NA |

| Hironaka 2013 [20] | 108 111 |

Paclitaxel Irinotecan |

9.5 8.4 |

Δ 1.1 | 0.88 (0.67–1.16) | 0.38 | 3.6 2.3 |

Δ 1.3 | 0.87 (0.67–1.14) | 0.33 |

| Nishikawa 2015a [21] | 63 64 |

S-1 + paclitaxel and paclitaxel-alone S-1 + irinotecan and irinotecan-alone |

11.1 11.8 |

Δ −0.7 | 0.98 (0.68–1.42) | 0.92 | 4.1 3.6 |

Δ 0.5 | 0.67 (0.47–0.97) | *0.03 |

| Roy 2013 [22] | 44 44 44 |

Docetaxel Irinotecan PEP02 |

7.7 7.8 7.3 |

Δ 0.2 | 0.83 (0.54–1.27) | 0.51 | 2.7 2.6 2.7 |

Δ 0.1 | 1.00 (0.68–1.47) | 0.38 |

| Combination therapy vs. taxane/irinotecan-alone | ||||||||||

| Cisplatin-based | ||||||||||

| Nishikawa 2015b [24] | 84 84 |

Cisplatin + irinotecan Irinotecan |

13.9 12.7 |

Δ 1.2 | 0.83 (0.60–1.17) | 0.29 | 2.6 2.1 |

Δ 0.5 | 0.86 (0.61–1.20) | 0.38 |

| Higuchi 2014 [23] | 64 63 |

Cisplatin + irinotecan Irinotecan |

10.7 10.1 |

Δ 0.6 | 1.00 (0.69–1.44) | 0.98 | 3.8 2.8 |

Δ 1.0 | 0.68 (0.47–0.98) | *0.04 |

| Kim 2015a [25] | 23 23 |

Cisplatin + docetaxel Docetaxel |

5.6 10.0 |

Δ −4.4 | 1.34 (1.02–1.77) | *0.03 | 1.8 1.3 |

Δ 0.5 | 0.96 (0.72–1.29) | 0.80 |

| Oxaliplatin-based | ||||||||||

| Kim 2015b [26] | 25 27 |

Oxaliplatin + docetaxel Docetaxel |

8.1 7.2 |

Δ 0.9 | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) | 0.35 | 4.9 2.0 |

Δ 2.9 | 0.64 (0.48–0.85) | *<0.01 |

| Fluoropyrimidine-based | ||||||||||

| Nishikawa 2015a [21] | 42 85 |

S-1 + paxlitaxel and S-1 + irinotecan Paclitaxel-alone and irinotecan-alone |

11.3 11.1 |

Δ 0.2 | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) | 0.81 | 3.7 3.7 |

Δ 0.0 | 1.01 (0.69–1.49) | 0.93 |

| Kim 2015a [25] | 25 23 |

S-1 + docetaxel Docetaxel |

6.9 10.0 |

Δ 3.1 | 1.12 (0.84–1.50) | 0.42 | 2.7 1.3 |

Δ 1.4 | 0.73 (0.54–0.98) | *0.03 |

| Nakanishi 2015 [27] | 38 40 |

S-1 + paclitaxel Paclitaxel |

10.0 10.0 |

Δ 0.0 | 0.83 (0.51–1.36) | NA | 4.6 4.6 |

Δ 0.0 | 0.86 (0.54–1.37) | NA |

| Tanabe 2015 [28] | 145 148 |

S-1 + irinotecan Irinotecan |

8.8 9.5 |

Δ −0.7 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 0.92 | 3.8 3.4 |

Δ 0.4 | 0.85 (0.67–1.07) | *0.02 |

| Sym 2013[29] | 30 29 |

5-FU/Lv + irinotecan Irinotecan |

6.7 5.8 |

Δ 0.9 | 0.83 (0.47–1.45) | 0.51 | 3.0 2.2 |

Δ 0.8 | 0.83 (0.50–1.39) | 0.48 |

| Maruta 2007 [30] | 12 12 |

5′DFUR + docetaxel Docetaxel |

7.6 4.0 |

Δ 3.6 | NA | *<0.05 | NA NA |

NA | NA | NA |

| 5-FU + methotrexate | ||||||||||

| Nishina 2015 [31] | 49 51 |

5-FU + methotrexate Paclitaxel |

7.7 7.7 |

Δ 0.0 | 1.13 (0.73–1.75) | 0.30 | 2.4 3.7 |

Δ -1.3 | 1.76 (1.15–2.70) | *<0.01 |

To summarize, treatment efficacy, median overall survival (months), median progression-free survival, hazard ratios (HR), 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI), and p values are shown for all chemotherapy studies

Notes: *P < 0.05

5-FU 5-fluorouracil, 95 % CI 95 % confidence interval, BSC best supportive care, RR risk ratio, Lv leucovorin, NA not available

Taxane or irinotecan as second-line monotherapy can be used in the second-line setting to treat patients with a performance status of 0 to 2, but the modest absolute survival benefit compared to best supportive care should be considered.

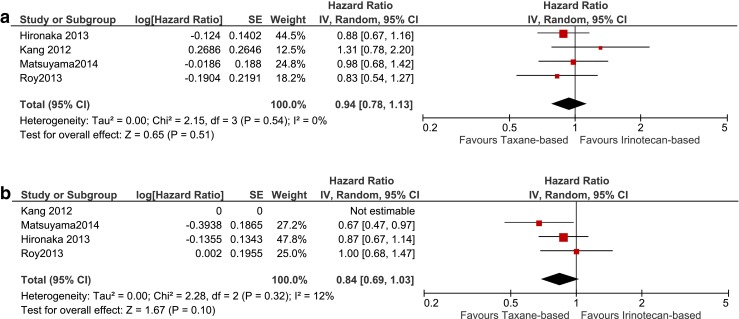

Taxane-based compared to irinotecan-based chemotherapy

Meta-analysis of four studies including 604 patients showed that there was no difference between taxane-based and irinotecan-based regimens in OS (HR 0.94, 0.78–1.13) and PFS (HR 0.84, 0.69–1.03), with absolute median OS gains ranging from Δ−1.3 to Δ1.1 months and absolute PFS gains ranging from Δ0.1 to Δ1.3 months (Fig. 4; Table 3)[19–22]. Irinotecan was associated with increased grade 3–4 neutropenia, diarrhea and anorexia compared to taxane, whereas taxane was associated with increased neuropathy (Table 3). In sum, taxane and irinotecan were similar in efficacy. For an individual patient, a taxane or irinotecan can be chosen based on the specific toxicity profile of these agents. Taxane and irinotecan will be regarded as comparators in the next sections.

Fig. 4.

Studies comparing taxane-based and irinotecan-based chemotherapy. Forest-plot of taxane-based compared to irinotecan-based chemotherapy terms of overall survival (a) and progression-free survival (b). Notes: Roy 2012 irinotecan and PEP02 arms were pooled and compared to the docetaxel arm. BSC best supportive care, IRI irinotecan, TAX taxane, PTX paclitaxel, DTX docetaxel

Combination chemotherapy compared to single-agent taxane or irinotecan

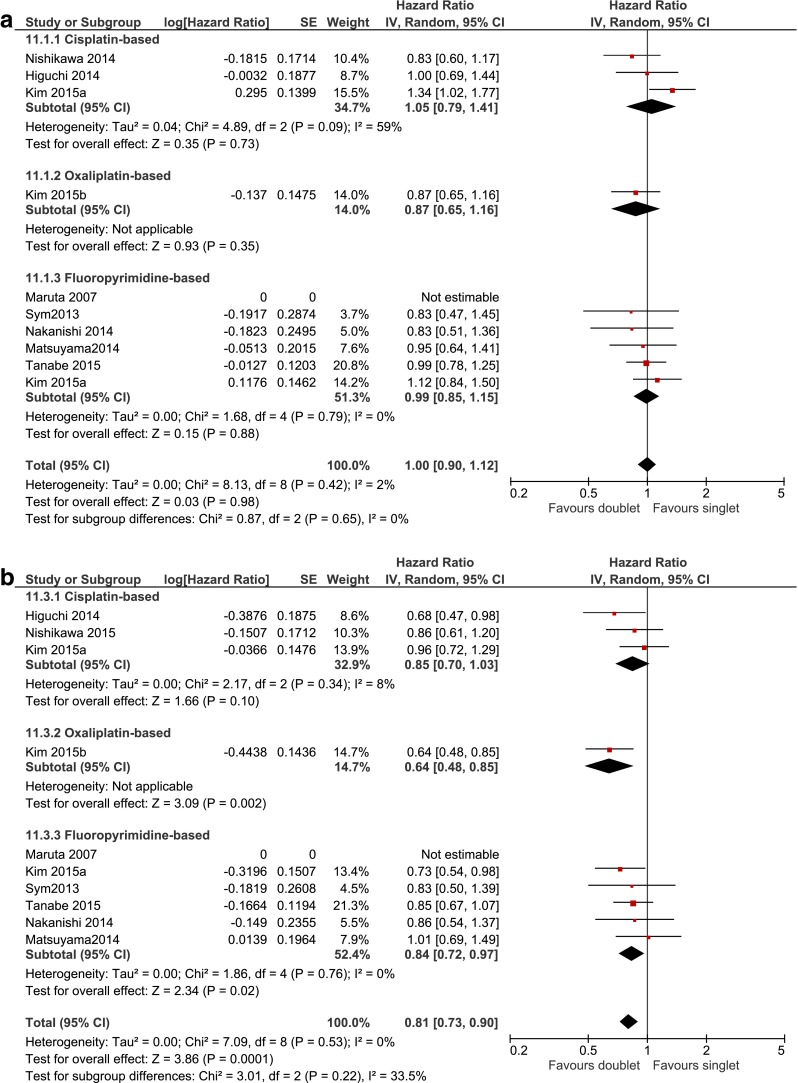

The effect of adding cisplatin, oxaliplatin or fluoropyrimidine to single-agent irinotecan or taxane was assessed in three studies including 341 patients [23–25], in one study including 52 patients [26] and in six studies including 629 patients [21, 25, 27–30] respectively (Fig. 5; Table 3). A HR for OS and PFS could not be calculated for one small study [30].

Fig. 5.

Studies comparing doublet and single-agent chemotherapy. The efficacy of doublet chemotherapy regimen, consisting of a taxane or irinotecan backbone combined with cisplatin, oxaliplatin, or fluoropyrimidine, vs. taxane or irinotecan single agent in terms of overall survival (a) and progression-free survival (b). BSC best supportive care, IRI irinotecan, TAX taxane, PTX paclitaxel, DTX docetaxel

Meta-analysis showed that doublets were not more effective compared to single agents in OS (HR 1.00, 0.90–1.12) and no significant differences were found with subgroup analysis by type of additional cytotoxic agent. On the other hand, the pooled effect for PFS was significant (HR 0.81, 0.73–0.90). Subgroup analysis showed that the addition of oxaliplatin to the taxane or irinotecan backbone was associated with increased PFS with HR 0.64 (0.48–0.85) and absolute median PFS gain of Δ2.9 months. Also, the addition of fluoropyrimidine resulted in longer PFS with HR 0.84 (0.72-0.97), but absolute median PFS gain ranged from Δ0 to Δ1.4 months only. The cisplatin-based subgroup did not reach statistical significance over monotherapy. No statistically significant heterogeneity was detected in any of the analyses (Fig. 5; Table 3). Overall, none of the grade 3–4 adverse events showed statistically significant differences between doublet and monotherapy, although a general trend towards increased toxicity could be observed for doublets (Table 4). Exploratory subgroup analysis showed that oxaliplatin-based doublets were associated with significantly increased grade 3–4 neutropenia (8/25 vs. 0/27, RR 18.31, 1.11–301.60) and fluoropyrimidine-based doublets with increased grade 3–4 anemia (37/292 vs. 26/336, RR 1.65, 1.02–2.66).

Table 4.

Grade 3–4 adverse events of second-line chemotherapy

| Grade 3–4 AE | Irinotecan-based vs. taxane-based chemotherapy | Combination chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy-alone | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irinotecan | Taxane | Estimate | Heterogeneity | Doublet | Singlet | Estimate | Heterogeneity | |||||||||||

| n | N | n | N | RR (95 % CI) | P | Trials | I 2 (%) | P | n | N | n | N | RR (95 % CI) | P | Trials | I 2 (%) | P | |

| Hematological | ||||||||||||||||||

| Neutropenia | 82 | 321 | 55 | 282 | 1.40 (1.04–1.88) | *0.03 | 4 | 0 | 0.74 | 144 | 487 | 124 | 533 | 1.21 (0.98–1.49) | 0.07 | 10 | 0 | 0.58 |

| Leukopenia | 27 | 173 | 25 | 172 | 1.07 (0.60–1.91) | 0.81 | 2 | 10 | 0.29 | 59 | 398 | 50 | 440 | 0.91 (0.47–1.76) | 0.79 | 8 | 56 | *0.03 |

| Trombocytopenia | 8 | 321 | 4 | 282 | 1.65 (0.51–5.30) | 0.40 | 4 | 0 | 0.94 | 8 | 408 | 8 | 454 | 1.16 (0.44–3.04) | 0.76 | 7 | 0 | 0.72 |

| Anemia | 62 | 321 | 53 | 282 | 1.16 (0.84–1.60) | 0.36 | 4 | 0 | 0.64 | 63 | 462 | 41 | 506 | 1.61 (0.97–2.66) | 0.06 | 9 | 22 | 0.24 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 18 | 261 | 10 | 216 | 1.30 (0.25–6.78) | 0.75 | 3 | 63 | 0.07 | 24 | 393 | 13 | 440 | 1.68 (0.52–5.42) | 0.39 | 8 | 42 | 0.10 |

| Non-hematological | ||||||||||||||||||

| Diarrhea | 5 | 110 | 1 | 282 | 5.06 (1.85–13.87) | *0.002 | 4 | 0 | 0.74 | 16 | 475 | 21 | 521 | 0.89 (0.47–1.70) | 0.73 | 9 | 0 | 0.77 |

| Nausea | 19 | 321 | 7 | 282 | 2.02 (0.82–4.99) | 0.13 | 4 | 0 | 0.51 | 21 | 434 | 23 | 481 | 1.01 (0.57–1.79) | 0.98 | 8 | 0 | 0.88 |

| Vomiting | 11 | 261 | 7 | 216 | 1.09 (0.40–2.97) | 0.87 | 3 | 0 | 0.48 | 5 | 334 | 10 | 380 | 0.65 (0.22–1.90) | 0.43 | 5 | 0 | 0.79 |

| Fatigue | 13 | 211 | 20 | 174 | 0.82 (0.25–2.66) | 0.74 | 3 | 46 | 0.16 | 22 | 392 | 19 | 439 | 1.29 (0.70–2.39) | 0.42 | 7 | 0 | 0.66 |

| Anorexia | 35 | 321 | 15 | 282 | 2.06 (1.13–3.73) | *0.02 | 4 | 0 | 0.51 | 58 | 462 | 57 | 506 | 1.11 (0.78–1.56) | 0.56 | 9 | 0 | 0.80 |

| Stomatitis | 3 | 60 | 2 | 66 | 1.65 (0.29–9.54) | 0.58 | 1 | NA | NA | 4 | 59 | 3 | 58 | 1.28 (0.29–5.69) | 0.75 | 3 | 0 | 0.51 |

| Neuropathy | 0 | 110 | 8 | 108 | 0.06 (0.00–0.99) | *0.05 | 1 | NA | NA | 2 | 64 | 2 | 61 | 0.91 (0.14–6.00) | 0.92 | 2 | 0 | 0.37 |

| Toxicity-related death | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 175 | 3 | 178 | 0.25 (0.03–2.27) | 0.22 | 2 | 0 | 0.84 |

Grade 3–4 adverse events of taxane-based vs. irinotecan-based chemotherapy (left) and doublet vs. single-agent chemotherapy (right)

Notes: the irinotecan and PEP02 arms from Roy 2012 were pooled and compared to the docetaxel arm

*P < 0.05

5-FU 5-fluorouracil, 95 % CI 95 % confidence interval, Lv leucovorin, RR risk ratio, NA not available

One study including 100 patients was analyzed separately, since only patients with peritoneal metastasis were included and seven out of 48 patients (15 %) in the methotrexate plus 5-FU combination arm did in fact receive 5-FU monotherapy [31]. Taxane monotherapy was associated with increased PFS (HR 0.57, 0.37–0.88) compared to a combination of methotrexate and 5-FU or 5-FU monotherapy (Table 3). There was no difference in OS. An increased rate of grade 3–4 neutropenia was found for methotrexate plus 5-FU vs. taxane (14/49 vs. 6/51, RR 2.43, 1.02–5.81). In sum, combination chemotherapy is not recommended as second-line treatment due to lack of superior efficacy at the cost of additional toxicity.

Single targeted agents compared to best supportive care

Meta-analysis was only possible for apatinib compared to placebo with 2 studies including 408 patients [13, 14], since all other targeted agents were investigated in one study only. In Table 5, the efficacy and statistically significant grade 3–4 adverse events of single targeted agents compared to BSC and single cytotoxic agents are summarized.

Table 5.

Efficacy and safety of second- or third-line targeted therapy

| Study | Efficacy sample size | Arms | Treatment line | Overall survival | Progression-free survival | Safety | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Median difference | HR (95%CI) | P | Median | Median difference | HR (95%CI) | P | Safety sample size | Grade 3–4 Toxicity | Exp n (%) vs. control n (%) | ||||

| Single targeted agent | ||||||||||||||

| Ramucirumab | 2nd | |||||||||||||

| Fuchs 2014 [5] | 238 117 |

Ramucirumab BSC |

5.2 3.8 |

Δ1.4 | 0.78 (0.60–1.00) | *0.05 | 2.1 1.3 |

Δ 0.8 | 0.48 (0.38–0.62) | *<0.01 | 236 115 |

No differences | ||

| Everolimus | 2nd or 3rd | |||||||||||||

| Ohtsu 2013 [12] | 439 217 |

Everolimus Placebo |

5.4 4.3 |

Δ 1.1 | 0.90 (0.75–1.08) | 0.12 | 1.7 1.4 |

Δ 0.3 | 0.66 (0.56–0.78) | *<0.01 | 437 215 |

Anorexia Hypokalemia Thrombocytopenia Stomatitis |

48 (11 %) vs. 12 (6 %) 26 (6 %) vs. 2 (1 %) 22 (5 %) vs. 3 (1 %) 20 (5 %) vs. 0 (0 %) |

|

| Regorafenib | 2nd or 3rd | |||||||||||||

| Pavlakis 2015 [32] | 97 50 |

Regorafenib Placebo |

5.8 4.5 |

Δ 1.3 | 0.74 (0.51–1.08) | 0.11 | 2.5 0.9 |

Δ 1.6 | 0.41 (0.28–0.59) | *<0.01 | 97 50 |

No differences | ||

| Targeted agent + chemotherapy | ||||||||||||||

| Ramucirumab + taxane | 2nd | |||||||||||||

| Wilke 2014 [6] | 330 335 |

Ramucirumab + Paclitaxel Paclitaxel + placebo |

9.6 7.4 |

Δ 2.2 | 0.81 (0.68–0.96) | *0.02 | 4.4 2.9 |

Δ 1.5 | 0.64 (0.54–0.75) | *<0.01 | 327 329 |

Hypertension Fatigue Neuropathy |

48(15 %) vs. 19 (6 %) 39 (12 %) vs. 18 (5 %) 27 (8 %) vs. 15 (5 %) |

|

| Sunitinib + chemotherapy | 2nd or 3rd | |||||||||||||

| Yi 2012 [11] | 56 49 |

Sunitinib + docetaxel Docetaxel |

8.0 6.6 |

Δ 1.4 | 0.94 (0.60–1.49) | 0.80 | NA | NA | 0.77 (0.52–1.16) | 0.21 | 56 49 |

|||

| Moehler 2013 [34] | 45 46 |

Sunitinib + Irinotecan + 5-FU/Lv Irinotecan + 5-FU/Lv |

10.5 9.0 |

Δ 1.5 | 0.82 (0.50–1.34) | 0.42 | 3.6 3.3 |

Δ 0.3 | 1.10 (0.70–1.74) | 0.66 | 45 46 |

|||

| Pooled | Sunitinib + CT vs. CT | 0.88 (0.63–1.24) | 0.47 | 0.91 (0.65–1.28) | 0.59 | Neutropenia | 43 (43 %) vs. 19 (20 %) | |||||||

| Nimotuzumab + Irinotecan | 2nd or 3rd | |||||||||||||

| Satoh 2015 [10] | 40 42 |

Nimotuzumab + Irinotecan Irinotecan |

8.2 7.6 |

Δ 0.6 | 0.99 (0.62–1.60) | 0.98 | 2.4 2.8 |

Δ -0.4 | 0.86 (0.52–1.44) | 0.57 | 40 42 |

No differences | ||

| Olaparib + taxane | 2nd | |||||||||||||

| Bang 2015a [33] | 62 62 |

Olaparib + paclitaxel Paclitaxel |

13.1 8.3 |

Δ 4.8 | 0.56 (0.35–0.87) | *0.01 | 3.9 3.5 |

Δ 0.4 | 0.80 (0.54–1.18) | 0.13 | 61 62 |

Neutropenia | 34 (56 %) vs. 24 (39 %) | |

| Targeted agents for specific molecular prespecified subgroups | ||||||||||||||

| HER-2 positive | 2nd | |||||||||||||

| Satoh 2014 [36] | 132 129 |

Lapatinib + paclitaxel Paclitaxel |

11.0 8.9 |

Δ 2.1 | 0.84 (0.64–1.11) | 0.10 | 5.5 4.4 |

Δ 1.1 | 0.85 (0.63–1.13) | 0.15 | 131 129 |

Febrile neutropenia Diarrhea |

9 (7 %) vs. 2 (2 %) 23 (18 %) vs. 0 (0 %) |

|

| Lorenzen 2015 [37] | 18 19 |

Capecitabine + lapatinib Lapatinib |

NR 4.7 |

NC | 1.06 (0.34–3.29) | 0.92 | 1.5 1.3 |

Δ 0.2 | NA | NS | 18 19 |

No differences | ||

| Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 amplification | 2nd or 3rd | |||||||||||||

| Bang 2015b [35] | 41 30 |

AZD-4547 Paclitaxel |

NA NA |

NA | NA NA |

1.8 3.5 |

Δ 1.7 | 1.57 (1.12–2.21) | NS | Not reported | ||||

| Third- or further-line single targeted agent | ||||||||||||||

| Apatinib | 3rd or further | |||||||||||||

| Li 2016 [14] | 176 91 |

Apatinib Placebo |

6.5 4.7 |

Δ 1.8 | 0.71 (0.54–0.94) | *0.01 | 2.6 1.8 |

Δ 0.8 | 0.44 (0.33–0.60) | *<0.01 | 176 91 |

|||

| Li 2013 [13] | 47 46 48 |

Apatinib 850 mg Apatinib 425 mg Placebo |

4.8 4.3 2.5 |

Δ 2.3 Δ 1.8 |

0.37 (0.22–0.62) 0.41 (0.24–0.71) |

*<0.01 *<0.01 |

3.7 3.2 1.4 |

Δ 2.3 Δ 1.8 |

0.18 (0.10–0.34) 0.21 (0.11–0.38) |

*<0.01 *<0.01 |

47 46 48 |

|||

| Pooled | Apatinib vs. placebo | 0.50 (0.32–0.79) | *<0.01 | 0.27 (0.14–0.51) | *<0.01 | HFS Hypertension |

23 (9 %) vs. 1 (%) 17 (6 %) vs. 0 (0 %) |

|||||||

To summarize treatment efficacy of targeted therapy, median overall survival (months), median progression-free survival and hazard ratios (HR) with 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) were shown. For safety of targeted therapy, only grade 3–4 AEs were reported for which a statistically significant difference exist between the occurrence in the treatments arms.

Notes: since more than one study was available for the comparisons for sunitinib and apatinib, also the pooled HRs were given.

*P < 0.05

5-FU 5-fluorouracil, 95 % CI 95 % confidence interval, BSC best supportive care, CT chemotherapy, d days, exp experimental agent, Lv leucovorin, HFS hand-foot syndrome, HR: hazard ratio, RR risk ratio, NA: not available, NC not calculable, NS: not statistically significant

In second-line setting, ramucirumab monotherapy showed increased benefit in both OS, HR 0.78 (0.61–1.00) with absolute median OS gain of Δ1.4 months and in PFS, HR 0.48 (0.38–0.62) with absolute median PFS gain of Δ0.8 months compared to BSC. In second- or third-line setting, no OS benefit of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus and the multityrosine kinase inhibitor regorafenib was found over BSC. Increased PFS was found for both everolimus, HR 0.66 (0.56–0.78), with median PFS gain of Δ0.3 months and for regorafenib, HR 0.41 (0.28–0.59), with median PFS gain of Δ1.6 months respectively. As third- or later-line therapy, apatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that selectively inhibits VEGFR-2, showed increased OS and PFS, HR 0.50 (0.32–0.79) and HR 0.27 (0.14–0.51) vs. BSC, with a median OS gain ranging from Δ1.8 to Δ2.3 months and PFS gain ranging from Δ0.8 to Δ2.3 months.

In Table 5, only grade 3–4 AEs were reported for which a statistically significant difference exist between the occurrence in the treatments arms. Compared to BSC, significantly increased grade 3–4 toxicities were anorexia, hypokalemia, thrombocytopenia, and stomatitis for second-or third-line everolimus, and hand-foot syndrome and hypertension with third- or later-line apatinib (Table 5). None of the AEs associated with second-line ramucirumab and second- or third-line regorafenib reached statistical significance compared to BSC. In sum, in third-line single-agent apatinib and in second-line single-agent ramucirumab may be considered for patients with performance status 0 or 1 who cannot or do not want to undergo chemotherapy. However, the modest absolute survival benefit compared to best supportive care should be taken into consideration.

The addition of a targeted agent to chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy-alone

In second-line setting, increased OS was shown for ramucirumab plus taxane (HR 0.81 0.68–0.96), with a median survival gain of Δ2.2 months, and for the enzyme poly-ADP ribose polymerase [PARP] inhibitor olaparib plus taxane (HR 0.56, 0.35–0.87), with a median survival gain of Δ4.8 months compared to taxane-alone. Also, increased PFS was found for ramucirumab plus taxane (HR 0.64, 0.54–0.75), with a median PFS gain of Δ1.5 months, but not for olaparib plus taxane (Table 5). In second- or third-line setting, the epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR] inhibitor nimotuzumab plus irinotecan and the multityrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib plus irinotecan-based chemotherapy did not show any significant difference in OS and PFS compared to chemotherapy-alone (Table 5). Compared to chemotherapy-alone, second-line ramucirumab plus taxane was associated with increased grade 3–4 hypertension, fatigue and neuropathy and both second-line olaparib plus taxane and second-or third-line sunitinib plus chemotherapy were associated with increased neutropenia (Table 5). None of the AEs associated with second- or third-line nimotuzumab plus taxane reached statistical significance compared to taxane-alone.

In sum, based on results of phase III studies ramucirumab plus taxane is the only combination therapy that can be recommended as second-line therapy for patients with a performance status of 0–1. Olaparib in combination with a taxane shows potential as a second-line regimen when results are confirmed by phase III results.

Targeted agents in specific molecular sub-populations

In HER-2 positive patients, the addition of lapatinib, a dual inhibitor of EGFR and HER-2 tyrosine kinase activity, to a taxane as second-line regimen was not associated with increased efficacy in OS and PFS over taxane-alone (Table 5). However, a significant effect was observed in the immunohistochemistry (IHC) 3+ subgroup for OS (HR 0.59, 0.37-0.93) and PFS (HR 0.54 0.33-0.90) [36]. The addition of capecitabine to lapatinib vs. lapatinib alone showed no difference in both OS and PFS in an HER-2 positive population [37]. Furthermore, one small study failed to demonstrate a benefit in OS or PFS for the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)1-3 inhibitor AZD-4547 over taxane-alone in a FGFR-2-amplificated population [35] (Table 5). In sum, there is no evidence for HER-2 directed second-line therapy, although lapatinib plus taxane showed promising efficacy in patients with HER2 IHC 3+.

Best supportive care: palliative treatment for obstruction and dysphagia

Stent placement, intraluminal brachytherapy, or intraluminal balloon dilatation are widely accepted palliative procedures to relief obstruction and dysphagia caused by locally advanced esophageal tumours [38, 39]. On the one hand, stent placement can provide rapid palliation but there is a risk of complications, compared to brachytherapy. On the other hand, brachytherapy is associated with long-term relief and with fewer complications compared to stent placement, but it takes longer before relief of symptoms is initiated [40]. Also, it has been shown that the combination of both brachytherapy and stent placement is more effective in survival and symptom relief compared to stent placement-alone [41]. Guidelines recommend the concurrent use of these palliative procedures and multimodality therapy, for example chemotherapy or targeted therapy, but these procedures should be carefully chosen based on the patients’ prognosis and needs.

Discussion

In this systematic review we showed that both taxane and irinotecan as single agents significantly prolonged survival compared to BSC. Although the hazard ratios were statistically significant, the absolute survival benefit was marginal and this should be taken into consideration in clinical practice. In contrast to earlier meta-analyses, the current meta-analysis provided evidence that taxane and irinotecan-based regimens are equally effective in terms of both OS and PFS. However, the two regimens showed a different toxicity profile, which may guide clinical decision-making in the use of a specific cytotoxic agent in an individual patient.

No OS benefit was detected for the addition of another cytotoxic agent (i.e., platinum or fluoropyrimidine) to a backbone of taxane or irinotecan. The addition of fluoropyrimidine significantly resulted in a statistically significant pooled HR of 0.84, but it is debatable whether a 16 % risk reduction of PFS is clinically relevant. According to a large international expert consensus panel, OS as endpoint in oncology clinical trials is more appropriate and a HR ≤ 0.80 is clinically relevant [15]. The panel stated a similar or even stricter criterion for PFS compared to the criterion of OS. The HR of 0.84 in the current meta-analysis does not meet the criterion of HR ≤ 0.80 for PFS. Moreover, the majority of the studies within this comparison did not show any absolute gain in median PFS. Of note, PFS was prolonged by the addition of oxaliplatin (HR 0.64, 0.48–0.85) in a small phase II study with patients that received cisplatin in the first-line treatment [26], so the potential of oxaliplatin for cisplatin-refractory patients could be subject of a larger prospective study. Based on this evidence, and acknowledging that toxicity was increased with combination therapy, we conclude that there is currently no role for combination chemotherapy in the second-line setting.

Regarding targeted therapy, the current systematic review provided evidence from phase III studies for three treatments. Second-line ramucirumab plus taxane significantly prolonged OS and PFS compared to taxane-alone with a clinically relevant absolute survival gain in patients with performance status 0 or 1 [6]. On the other hand, second-line ramucirumab as monotherapy showed a marginal absolute survival gain compared to BSC [5]. Apatinib monotherapy is currently the only treatment that has been tested in a third- or later-line setting (in both phase II and III studies) and might be clinically relevant in terms of relative and absolute gain in survival for patients with ECOG performance status 0 or 1 [13, 14]. In phase II studies, regorafenib monotherapy met its primary outcome criterion PFS by a HR of 0.41, but the median gain in PFS was only 1.6 months. Future large prospective studies should indicate if regorafenib could be utilized in second- or third-line setting [32]. Although olaparib plus taxane did not meet its primary endpoint PFS, OS was significantly prolonged as quantified by a HR of 0.56 and an absolute survival gain of median 4.8 months [34]. Results of a phase III RCT are awaited for olaparib (NCT01924533). Evidence for the addition of lapatinib to taxane in an HER-2 positive population was weak; only patients with HER2 IHC 3+ benefited from lapatinib while toxicity was increased [36].

We also discuss the limitations of this review. First, some studies with targeted agents, such as regorafenib monotherapy [32], were conducted in second- as well as in third-line setting. This makes the assessment of the specific indication for the targeted agent difficult. However, the study population is homogeneous as all included patients were refractory to fluoropyrimidine and platinum-based regimens. Furthermore, except for apatinib and sunitinib, meta-analysis was not possible for the majority of targeted agents since those were examined in a single study only. As most targeted agents have different mechanisms of action, pooling would introduce heterogeneity and would complicate the interpretation of results. Moreover, the overview of both relative and absolute efficacy results as well as the statistically significant grade 3–4 adverse events provided in Table 5 might be sufficient to value each targeted agent against current evidence.

In conclusion, based on the currently available phase III evidence, ramucirumab plus taxane can be regarded standard treatment for fit patients with a performance status of 0 or 1, who wish to undergo second-line treatment. The phase III results of olaparib in combination with paclitaxel are eagerly awaited. Combination chemotherapy has currently no role in the second-line treatment due to lack of efficacy. Taxane or irinotecan as monotherapy might be alternatives for patients with a performance status of 2 and thus not eligible for ramucirumab plus taxane or for patients with performance status 0 or 1 who prefer monotherapy. However, the modest absolute survival benefit of taxane or irinotecan monotherapy compared to best supportive care should be considered. Apatinib is a valuable option as third-line therapy for fit patients with a performance status of 0 or 1, again with limited absolute survival benefit. Finally, patient with a performance status larger than 2 after first- or second-line therapy, should be offered BSC.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Literature search: EtV and NHM

Quality assessment: EtV, NHM, and HvL

Data extraction: EtV, LN, RM, and NHM

Statistical analysis: GvV, EtV, and LN

Manuscript writing: EtV, NHM, HvL, MvO, and GvV

Overview of the study: MvO and HvL

All authors gave final approval for the submission of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

No funding source

Disclosure

Dr. Martijn G. H. van Oijen has received unrestricted research grants from Bayer, Lilly, Merck Serono, and Roche. Prof. dr. Hanneke W. M. van Laarhoven has served as a consultant for Celgene, Lilly, and Nordic, and has received unrestricted research funding from Bayer, Celgene, Lilly, Merck Serono, MSD, Nordic, and Roche. Dr. Gert H. M. van Valkenhoef has served as a consultant for Johnson & Johnson. All other authors have no disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner AD, Unverzagt S, Grothe W, Kleber G, Grothey A, Haerting J, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 2010;3:CD004064. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004064.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HS, Kim HJ, Kim SY, Kim TY, Lee KW, Baek SK, et al. Second-line chemotherapy versus supportive cancer treatment in advanced gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology. 2013;24(11):2850–2854. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janowitz T, Thuss-Patience P, Marshall A, Kang JH, Connell C, Cook N, et al. Chemotherapy vs supportive care alone for relapsed gastric, gastroesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of patient-level data. British Journal of Cancer. 2016;114(4):381–387. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs C, Tomasek J, Yong C, Dumitru F, Passalacqua R, Goswami C, et al. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9911):31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilke H, Muro K, Cutsem E, Oh S, Bodoky G, Shimada Y, et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15(11):1224–1235. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waddell T, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A, Arnold D. Gastric cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2014;40(5):584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Ma B, Huang XT, Li YS, Wang Y, Liu ZL. Doublet versus single gent as second-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(8):e2792. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iacovelli R, Pietrantonio F, Farcomeni A, Maggi C, Palazzo A, Ricchini F, et al. Chemotherapy or targeted therapy as second-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer. A systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satoh T, Lee K, Rha S, Sasaki Y, Park S, Komatsu Y, et al. Randomized phase II trial of nimotuzumab plus irinotecan versus irinotecan alone as second-line therapy for patients with advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18(4):824–832. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0420-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yi JH, Lee J, Park SH, Park JO, Yim DS, Park YS, et al. Randomised phase II trial of docetaxel and sunitinib in patients with metastatic gastric cancer who were previously treated with fluoropyrimidine and platinum. British Journal of Cancer. 2012;106(9):1469–1474. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohtsu A, Ajani JA, Bai YX, Bang YJ, Chung HC, Pan HM, et al. Everolimus for previously treated advanced gastric cancer: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III GRANITE-1 study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(31):3935–3943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Guo W, Xiong J, Bai Y, et al. Apatinib for chemotherapy-refractory advanced metastatic gastric cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, phase II trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(26):3219–3225. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.8585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Xiong J, Wu C, Bai Y, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis, L. M., Bernstein, D. S., Voest, E. E., Berlin, J. D., Sargent, D., Cortazar, P., et al. (2014). American Society of Clinical Oncology perspective: raising the bar for clinical trials by defining clinically meaningful outcomes. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(12):1277–1280. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, Janowitz T, Coxon FY, Wadsley J, et al. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15(1):78–86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thuss-Patience, P.C., Kretzschmar, A., Bichev, D., Deist, T., Hinke, A., Breithaupt, et al. (2011). Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer—a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). European Journal of Cancer, 47(15), 2306–2314. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim DH, Park KW, Oh SY, Kwon HC, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(13):1513–1518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hironaka S, Ueda S, Yasui H, Nishina T, Tsuda M, Tsumura T, et al. Randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing irinotecan with paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer without severe peritoneal metastasis after failure of prior combination chemotherapy using fluoropyrimidine plus platinum: WJOG 4007 trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(35):4438–4444. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishikawa, K., Imamura, H., Kawase, T., Gotoh, M., Kimura, Y., Ueda, S., et al. (2015). A randomized phase II factorial design trial of CPT-11 versus PTX versus each combination with S-1 in patients with advanced gastric cancer refractory to S-1: final results of OGSG0701. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33 (3 suppl. 1). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Roy A, Cunningham D, Hawkins R, Sorbye H, Adenis A, Barcelo JR, et al. Docetaxel combined with irinotecan or 5-fluorouracil in patients with advanced oesophago-gastric cancer: a randomised phase II study. British Journal of Cancer. 2012;107(3):435–441. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higuchi K, Tanabe S, Shimada K, Hosaka H, Sasaki E, Nakayama N, et al. Biweekly irinotecan plus cisplatin versus irinotecan alone as second-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer: a randomised phase III trial (TCOG GI-0801/BIRIP trial) European Journal of Cancer. 2014;50(8):1437–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishikawa K, Fujitani K, Inagaki H, Akamaru Y, Tokunaga S, Takagi M, et al. Randomised phase III trial of second-line irinotecan plus cisplatin versus irinotecan alone in patients with advanced gastric cancer refractory to S-1 monotherapy: TRICS trial. European Journal of Cancer. 2015;51(7):808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim B, Lee KW, Kim MJ, Han HS, Park YI, Park SR. A multicenter randomized phase II study of docetaxel vs. docetaxel plus cisplatin vs. docetaxel plus S-1 as second-line chemotherapy in metastatic gastric cancer patients who had progressed after cisplatin plus either S-1 or capecitabine. European Journal of Cancer. 2015;51(suppl 3):S432. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(16)31216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J, Ryoo H, Bae S, Kang B, Chae Y, Yoon S, et al. Multi-center randomized phase ii study of weekly docetaxel versus weekly docetaxel-plus-oxaliplatin as a second-line chemotherapy for patients with advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Research. 2015;35(6):3531–3536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakanishi K, Kobayashi D, Mochizuki Y, Ishigure K, Ito S, Kojima H, et al. Phase II multi-institutional prospective randomized trial comparing S-1 plus paclitaxel with paclitaxel alone as second-line chemotherapy in S-1 pretreated gastric cancer (CCOG0701) International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0919-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanabe K, Fujii M, Nishikawa K, Kunisaki C, Tsuji A, Matsuhashi N, et al. Phase II/III study of second-line chemotherapy comparing irinotecan-alone with S-1 plus irinotecan in advanced gastric cancer refractory to first-line treatment with S-1 (JACCRO GC-05) Annals of Oncology. 2015;26(9):1916–1922. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sym SJ, Hong J, Park J, Cho EK, Lee JH, Park YH, et al. A randomized phase II study of biweekly irinotecan monotherapy or a combination of irinotecan plus 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (mFOLFIRI) in patients with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma refractory to or progressive after first-line chemotherapy. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2013;71(2):481–488. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maruta, F., Ishizone, S., Hiraguri, M., Fujimori, Y., Shimizu, F., Kumeda, et al. (2007). A clinical study of docetaxel with or without 5′DFUR as a second-line chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Medical Oncology, 24(1):71–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Nishina T, Boku N, Gotoh M, Shimada Y, Hamamoto Y, Yasui H, et al. Randomized phase II study of second-line chemotherapy with the best available 5-fluorouracil regimen versus weekly administration of paclitaxel in far advanced gastric cancer with severe peritoneal metastases refractory to 5-fluorouracil-containing regimens (JCOG0407) Gastric Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavlakis, N., Sjoquist, K., Tsobanis, E., Martin, A., Kang, Y-K., Bang, Y-J., (2015). INTEGRATE: A randomized phase II double-blind placebo-controlled study of regorafenib in refractory advanced oesophagogastric cancer (AOGC)—a study by the Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group (AGITG), first results. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(3 suppl. 1).

- 33.Bang, Y.J., Im, S.A., Lee, K.W., Cho, J.Y., Song, E.K., Lee, K.H., et al. (2015). Randomized, double-blind phase II trial with prospective classification by ATM protein level to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of olaparib plus paclitaxel in patients with recurrent or metastatic gastric cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(33, 3858–3865). doi:10.1200/jco.2014.60.0320. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Moehler, M., Thuss-Patience, P., Schmoll, H.J., Hegewisch-Becker, S., Wilke, H., Al-Batran, et al. S.E., (2013). Na-Folfiri plus sunitinib versus Na-Folfiri alone in advanced chemorefractory esophagogastric cancer patients: a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled multicentric AIO phase II trial. Onkologie, 36, 73–74. doi:10.1159/000356365.

- 35.Bang, Y.J., Van Cutsem, E., Mansoor, W., Petty, R.D., Chao, Y., Cunningham, D. et al., (2015). A randomized, open-label phase II study of AZD4547 (AZD) versus paclitaxel (P) in previously treated patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC) with fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) polysomy or gene amplification (amp): SHINE study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(15), Abstract 4014.

- 36.Satoh T, Xu RH, Chung HC, Sun GP, Doi T, et al. Lapatinib plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone in the second-line treatment of HER2-amplified advanced gastric cancer in Asian populations: TyTAN—a randomized, phase III study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(19):2039–2049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorenzen S, Riera KJ, Haag GM, Pohl M, Thuss-Patience P, Bassermann F, et al. Lapatinib versus lapatinib plus capecitabine as second-line treatment in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-amplified metastatic gastro-oesophageal cancer: a randomised phase II trial of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. European Journal of Cancer. 2015;51:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Almhanna K, Bentrem DJ, Besh S, Chao J, et al. Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 1.2015. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2015;13(2):194–227. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evans JA, Early DS, Chandraskhara V, Chathadi KV, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA. The role of endoscopy in the assessment and treatment of esophageal cancer. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77(3):328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Homs MY, Steyerberg EW, Eijkenboom WM, Tilanus HW, Stalpers LJ, et al. Single-dose brachytherapy versus metal stent placement for the palliation of dysphagia from oesophageal cancer: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9444):1497–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu HD, Guo JH, Mao AW, Lv WF, Ji JS, Wang WH. Conventional stents versus stents loaded with (125)iodine seeds for the treatment of unresectable oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15(6):612–619. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]