Abstract

Serious lung infections, such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, and chronic obstructive cystic fibrosis-related bacterial diseases, are increasingly difficult to treat and can be life-threatening. Over the last decades, an array of therapeutics and/or diagnostics have been exploited for management of pulmonary infections, but the advent of drug-resistant bacteria and the adverse conditions experienced upon reaching the lung environment urge the development of more effective delivery vehicles. Nanotechnology is revolutionizing the approach to circumventing these barriers, enabling better management of pulmonary infectious diseases. In particular, polymeric nanoparticle-based therapeutics have emerged as promising candidates, allowing for programmed design of multi-functional nanodevices and, subsequently, improved pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficiency, as compared to conventional routes of delivery. Direct delivery to the lungs of such nanoparticles, loaded with appropriate antimicrobials and equipped with “smart” features to overcome various mucosal and cellular barriers, is a promising approach to localize and concentrate therapeutics at the site of infection while minimizing systemic exposure to the therapeutic agents. The present review focuses on recent progress (2005 to 2015) important for the rational design of nanostructures, particularly polymeric nanoparticles, for the treatment of pulmonary infections with highlights on the influences of size, shape, composition, and surface characteristics of antimicrobial-bearing polymeric nanoparticles on their biodistribution, therapeutic efficacy, and toxicity.

Introduction

Serious lung infections, such as pneumonia, tuberculosis (TB), and chronic obstructive cystic fibrosis (CF)-related bacterial diseases, are increasingly difficult to treat and can be life-threatening. A number of therapeutics and/or diagnostics have been employed in the management of pulmonary infections. However, poor solubility of some antimicrobial agents, unfavorable pharmacokinetics, lack of selectivity for penetration into diseased tissues, advent of bacteria with multiple drug resistances,1,2 and, as a result, administration of higher-intensity antibiotic regimens pose significant obstacles to optimizing therapeutics.3 A promising approach to alleviate these critical barriers in traditional treatment is the development of engineered nanoparticles (NPs) (i.e., particles in the size range 5–1000 nm) as alternative delivery carriers for a wide range of therapeutics, including drugs, antibodies, proteins, nucleic acids, and various diagnostic agents.1,4 A wide range of types of NPs, such as dendrimers, lipids, ceramic, fullerenes, and metallic NPs, have been loaded with therapeutic agents and/or imaging probes to improve pharmacokinetics and biodistribution profiles of their small-molecule cargo, aiming to achieve maximum delivery to diseased tissues while reducing exposure of healthy tissues to the introduced materials.5,6 Among the diverse selection of nanocarriers, NPs constructed from polymeric backbone-structured building blocks offer precise control over their architectures, surface characteristics, and supramolecular assembly.7 Direct delivery of polymeric NPs, loaded with appropriate antimicrobials and equipped with “smart” features to overcome various mucosal and cellular barriers, is a promising approach to localize treatment to the site of infection with minimal systemic adverse effects or toxicity from the applied therapeutic agents. This review focuses on recent progress (2005–2015) in the rational development of polymeric NPs for the treatment of pulmonary infections, detailing their chemistry, antimicrobial activity, biodistribution, and toxicity.

1. Lungs as a Target Site

Drugs used for treatment of pulmonary diseases are typically administered via oral, intravenous (IV), or inhalational routes. Among many organs in the human body, the lungs represent an attractive target for local drug delivery due to unique anatomical and physiological features and minimal interactions between the targeted sites and other organs.8

Oral (enteral) administration of therapeutics for systemic distribution has been routinely applied for treatment of a broad range of diseases, including pulmonary infections, due to the large surface area (ca. 200 m2) of the intestinal epithelium and ease of administration, facilitating patient compliance with scheduled dosing.9 However, the enteral route involves several significant potential complications, such as inhibited absorption of hydrophilic drugs by the epithelial barrier, limited accessibility of the therapeutics to the site of action (i.e., poor distribution), degradation of active moieties during gastrointestinal transit (especially resulting from degradative and proteolytic enzymes and diverse pHs found along the gastrointestinal tract), and toxicity due to non-selective distribution of encapsulated cargo.10,11 Many of these barriers can be circumvented by parenteral (usually IV) administration. Delivery of pulmonary therapies via the IV route bypasses the need to traverse or diffuse through mucosal barriers, which is a challenge in inhalational treatment approaches.12 However, the IV approach is an invasive administration route that confers substantial inconvenience, costs, and adverse effects (e.g., central venous catheter complications) over a long course of therapy. Furthermore, both the enteral and IV routes suffer from non-selective distribution and from filtering or metabolism of active ingredients by multiple organ-level clearance mechanisms (e.g., mononuclear phagocytes of the liver and the spleen, or first-pass chemical modification in the liver) before the intended destination in the body is reached.8 In IV delivery of nanostructures, it is necessary to use submicron particles to avoid adverse effects, such as pulmonary embolism, that may be associated with larger particle size (> 5 μm).13

In addition to favoring patient compliance, principal advantages of the direct administration of antimicrobials into the lungs via inhalation, relative to oral or IV administration (Figure 1), relate to unique anatomical and physiological features of the lungs that are favorable for drug absorption: large surface area of the alveolar epithelium, ca. 70–140 m2 in an adult human; high vascularization and thin vascular-epithelial barrier in alveolar region, ca. 0.1–0.5 μm as compared to ca. 20–30 μm of the columnar intestinal epithelium, that mediates considerable permeation and mass transfer with close contact to the central blood circulation; exposure of the lungs to the entire cardiac output (ca. 5 L/min); avoidance of hepatic first-pass metabolism; and relatively lower local proteolytic activity as compared to that of the gastrointestinal tract.14–16 In this last regard, inhalation represents an attractive alternative to IV administration for systemic delivery of inhaled therapeutic macromolecules, such as proteins, peptides, and DNAs or RNAs.8,17 Furthermore, the pulmonary route allows for 10- to 200-fold greater bioavailability of such macromolecules as compared with other non-invasive routes.17 Consequently, aerosolized antibiotics have been suggested to avoid the high and frequent dosing of oral and IV antibiotics (and associated systemic effects), enabling the delivery of locally high doses of antimicrobials with more rapid attainment of effective concentrations at the site of infection, without excessive absorption of the therapeutics into the systemic circulation.8

Figure 1.

Challenges and biodistribution of nanoparticles following (A) intravenous, (B) oral, and (C) inhalational administrations.

Despite these substantial advantages of inhalation treatment, such delivery of relatively small therapeutics typically suffers from their rapid clearance by alveolar macrophages upon deposition into the lungs, resulting in a limited amount of residence time and a reduced drug concentration in the vicinity of bacteria.16,17 Considering the inherent functions of the lungs (i.e., exchange of gas between the blood and the external environment and maintenance of pH homeostasis, not absorption of nutrients), the lung epithelium is not well equipped with transporters and channels as observed in liver and intestine.15 Additionally, inefficient delivery of the small fractions of inhaled therapeutics deep into the bronchial tree where the mucosal and epithelial barriers have a high resistance, possible degradation of the free drugs, and non-target selectivity of the applied therapeutics are likely to require a higher and more frequent doses of drugs, inducing concerns of systemic toxicity.18 Additionally, loss of active compounds and/or deformation of particles during generation of inhalable particles may complicate the administration of accurate doses of active ingredients in the final formulation.19

2. Pulmonary Delivery of Polymeric Nanocarriers: Promises versus challenges

To address the aforementioned limits in the treatment of lung infections, advances in nanomedicine hold great promise for the delivery of therapeutic agents.20,21 Inorganic NPs, ranging from ceramic to metallic, showed their potential pulmonary applications in the field of magnetic resonance imaging and stimuli-responsive therapeutic and/or diagnostic delivery, but limited surface chemical availability, instability, and poor biocompatibility are drawbacks.22,23 Various types of particles in nano-sized system (from organic to inorganic to metallic) present maximized incorporation of targeting ligand and protective coating at their periphery, but the usage of inorganic or metallic NPs for pulmonary application is rather limited to their use as imaging agent. On the other hand, polymeric NPs, in general, offers precise control over particle composition, size, and structure contributing to the improved pharmacokinetics, enhanced aqueous solubility of insoluble hydrophobic drugs, stabilization of therapeutic agents against possible hydrolytic and/or enzymatic degradation, feasibility to incorporate surface decorating moieties (e.g., cell-targeting peptides) onto the particle, mediation of sustained and/or stimuli-responsive release of the payloads, and mimicking natural nanosystems (e.g., viruses, lipoproteins, and proteins) for cell-specific targeted delivery with increased bioavailability.7,24

Yet, major challenges associated with pulmonary NP delivery include formulation of particles into a desired size range, durability of NPs against shear forces during nebulization, deposition of particles onto the intended sites, mucociliary clearance, steric hindrance, adhesiveness and enzymatic activity of the mucus gel or sputum, uptake by alveolar macrophages, and internalization of particles into epithelial cells.25,26 For instance, delivery of drugs or nucleic acids loaded within nanocarriers into the airways for treatment of CF-related bacterial infections is typically inefficient, ascribed mostly to the presence of sputum having a bulk viscosity ca. 105 times greater than water.26,27 As a delivery carrier, destabilization of NPs can be a direct consequence of drug leakage, disassembly and/or biodegradation of the particles, detachment of surface-decorating moieties, and opsonization.28 Even though the drug encapsulation-strategy into NPs has shown superiority in targeting and sustained release, as compared to free drugs, it still suffers from rapid and nonselective NP clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) upon deposition in the lungs.29 For effective treatment of intracellular infections, such as TB, pneumonia, and aspergillosis, the inhaled therapeutic particles would have to effectively reach the macrophages, which bacteria and fungi utilize as a breeding ground, at therapeutic levels.30,31 Furthermore, exhalation, effects of degradation products, cytotoxicity, and immunogenicity should be also accounted for in the design and administration of polymeric NPs for treatment of respiratory diseases.32

3. Biodistribution: Effects of size, shape, and surface chemistry of polymeric nanoparticles

Physicochemical characteristics of the particles, such as size,33–36 shape,37–39 surface charge,40,41 and composition29,42 influence their biodistribution, (sub)cellular internalization, and toxicity.43–46 Numerous studies have attempted to address the effects of these factors individually; however, what is not fully understood is the interdependent role(s) of these determinants for the intracellular fate of NPs, with some exceptions.39,47,48 The degree of success in effectively delivering nanotherapeutics to various anatomic sites hinges strongly on the attributes of the applied delivery carriers; for instance, size plays a predominant role in achieving deep-lung deposition of inhaled NPs, while carrier stability in traversing the harsh gastrointestinal environment should be also considered in NPs intended for oral administration. In the meantime, the antimicrobial activity of therapeutic NPs via IV administration depends on the capabilities of NPs to internalize into specific cellular and/or sub-cellular compartments and to remain stable during blood circulation. In the following sections, the effects of size, surface charge, and other important variables on the biodistribution and therapeutic efficacy of polymeric NPs will be highlighted.

3.1 Effects of Particle Size and Surface Properties on Distribution following IV Administration

It is generally accepted that the diameter determines the tissue distribution of spherical particles. Spherical particles smaller than ca. 5 nm become rapidly cleared from blood circulation through extravasation or renal clearance, and those larger than 15 μm are eliminated by mechanical filtration in lung capillary beds, posing risk for pulmonary embolism. Spherical particles in the range of ca. 5 nm–15 μm in diameter are taken up by the MPS in liver, spleen, lung, and bone marrow following IV administration.49,50

Particle surface is often modified into hydrophilic and/or charged characteristics to improve the blood circulation time by avoiding MPS uptake (e.g., PEGylation), to enhance cellular uptake and endosomal escape (e.g., positive charge), or to change hydrophilicities and/or conformations at different pH values (e.g., negative charge).7 Nevertheless, this surface modification strategy does not appear to be valid for targeted lung delivery following IV administration, as seen with lack of targeted in vivo biodistribution of PEGylated or charged NPs via intravenous route of administration. 51–53 Upon IV injection of carboxyl-coated PS spheres in three different sizes, ca. 20, 100, or 1000 nm into F344 female rats, all three types of particles deposited mostly in liver, spleen, and lung, and the proportion of particles of ca. 100 and 1000 nm in the spleen increased significantly over time due to their clearance via the MPS.54 Among three particles recovered in the uterus and ovary, 20-nm particles showed a longer circulation than 1000-nm particles with two orders of magnitude increases in the number from 1 h to 28 days post-injection. This report was consistent with the data seen with short-term distribution, at 30 min, of amino-modified PS particles injected into mice, where 1000-nm spherical particles showed a faster clearance, ca. 85%, from the blood and higher uptake by the liver, as compared to ca. 60% of 100-nm particles.55 Small fractions, ca. 1–3%, of both particles in different sizes were found in the spleen.

Formulating particles in micron size could be ideal to achieve passive targeting by venous filtration and entrapment into the capillary beds of the lungs after IV administration,50 A few recent studies demonstrated preparation of NP aggregates in micron size. For instance, Sinko et al. prepared poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-stabilized aggregated nanogel particles (SANPs) with a size of ca. 30 μm, where the crosslinker, 1,6-hexane-bis-vinylsulfone, was programmed to be degraded by enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinase-2 present in the lungs, and the subsequent PEG monomers could be eliminated by renal filtration.56 The particles accumulated selectively in the lungs (primarily in alveolar regions) in rats within 30 min following tail vein injection, and the majority of them remained in the lungs for 48 h. In contrast, controls (i.e., free dyes) were rapidly eliminated (< 30 min) from the body upon injection. The enzymatically degraded products were found in the urine after elimination by renal filtration. In another study, Sinko et al. highlighted the size effects of polystyrene (PS) NPs of ca. 2–10 μm in diameter on lung targeting efficiency, intra-lung distribution, and retention time after IV administration to rats, where microparticles (MPs) with diameter between ca. 6 and 10 μm were claimed to be the optimal size for transient but highly efficient targeting to pulmonary capillaries.50 Prud’homme et al. prepared lung-targeting composite gel MPs (CGMPs) in the size range of 10–40 μm, composed of ca. 100 nm in a PEG gel matrix.57 Following tail vein injection of ca. 16 μm CGMPs in mice, uniform and selective delivery of CGMPs to the lungs was observed without off-site deposition in the heart, kidney, spleen, or liver. Meanwhile, hydrolysis of ester bonds in the network allowed for complete degradation of CGMP after 55 days in aqueous solution, which was promising to improve the retention time in the lung for sustained delivery.

3.2 Effects of Particle Size and Surface Properties on Distribution following Pulmonary Administration

The distribution of particulates following inhalational administration is highly particle size-dependent.58 In general, inhaled particulates with aerodynamic diameter (daer) between 0.5 and 5 μm deposit in the central and distal tracts, while those > 5 μm become trapped in the upper airways (i.e., mouth, trachea, and main bronchi) and those < 0.5 μm are mostly exhaled.59 As daer of the particle formulation could be directly influenced by the aerosolization mode, interplay between the design of aerosol particles and the choice of aerosolization mode should be carefully considered. Detailed information on the type, development history, mechanism, and characteristics of aerosol delivery devices, including nebulizer, metered-dose inhaler, and dry powder inhaler, have been discussed in other review articles.16,60–62

Upon particulate deposition, transport of polymeric NPs across a thick mucus layer (as found in CF patients) first depends on particle size, typically permeable only for NPs ca. 30–500 nm in diameter.63,64 Modification of the particle surface may help avoid retention and clearance in the mucus, thereby allowing for enhanced drug delivery.26 Hanes et al. assessed the different diffusion rates of uncoated carboxyl-modified (muco-adhesive) or PEGylated (e.g. 2 or 5 kDa) (muco-inert) PS NPs on ex vivo fresh murine tracheal tissue mucus layers, where 100 nm muco-inert NP diffused successfully while 100 nm muco-adhesive NPs were immobilized.65

Meanwhile, mucociliary clearance of particles trapped in the pulmonary mucus blanket appears to be independent of size (ca. 50 nm up to 6 μm), shape (spheres and rods) and surface charge (ca. −50 to +50 mV) of particles. Lehr et al. claimed that the equally efficient mucociliary clearance of particles with varying size and surface characteristics was ascribed to the immobilization of such particles inside the mucus blanket, upon tracking the trajectories of inhaled particles in the mucus blanket ex vivo and in silico.66,67 Instead, the chemical property of NP determined the mucociliary clearance rate based on a trachea-based in vitro model using NPs. Particles, in the rage of ca. 50 nm–6 μm in size and ca. −42 +47 mV in zeta potential, composed of different PLGA-based copolymers showed significant effect on particle clearance in contrast to PS particles displaying no difference.67 Particularly, PEG-PLGA particles exhibited the fastest transport rates (i.e., ca. 5.9±1.7 mm/min) and mucoadhesive chitosan-PLGA particles were transported at the slowest rate (i.e., ca. 0.7±0.3 mm/min) among tested NPs. In another study, Brody et al. observed rapid clearance of polyacrylamide-based hydrogel MPs of 1–5 μm in diameter by mucociliary transport and through the circulation as opposed to prolonged lung retention of 20–40 nm counterparts, enhanced by cell-penetrating peptides, nona-arginine, following intratracheal administration.68

3.3 Effect of Particle Size, Shape, and Surface Properties on Clearance by the MPS following Pulmonary Administration

It is generally understood that increasing the particle size leads to the higher possibility of phagocytosis by macrophages. Mitragotri et al. demonstrated this particle size-dependent alveolar phagocytosis in rats (e.g., the maximal phagocytosis and attachment with particles in the size range of ca. 2–3 μm).33 In concert with this finding, Makino et al. observed a higher degree of alveolar macrophage uptake with PS particles with a diameter of 1 μm than those with diameters < 500 nm or > 6 μm.69 Meanwhile, trapping of PS particles of 1 μm in diameter by alveolar macrophages was also influenced by their surface properties; particles displaying primary amines were most effectively trapped as compared to those functionalized with carboxyl, sulfate, or hydroxyl groups. Based on this information, more effective uptake and therapeutic action of NPs might be achieved with NP size < ca. 500 nm in diameter to avoid the alveolar macrophages, unless intended. On the other hand, DeSimone and Ting et al. reported more uptake of smaller particles of ca. 80 × 320 nm in vivo by monocytes and macrophages than larger particles of ca. 6 μm diameter, using PLGA or PEG hydrogel particles prepared by Particle Replication in Non-wetting Template (PRINT) fabrication process.70 More recently, three sizes of PEGylated PRINT nanogel particles (i.e., 80 × 320 nm, 1.5, and 6 μm donuts) showed increased lung residence time, with the largest increase in residence time for the smallest 80 × 320 nm particles, upon instillation in the airways of C57BL/6 mice.71 These particles were retained in the lung for at least a month without obvious inflammation.

Mitragotri et al. highlighted the complex interplay between size and shape of particulates in phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages, using six different types of PS particles (i.e., spheres, oblate ellipsoids, prolate ellipsoids, elliptical disks, rectangular disks, and UFO-shaped particles).33,39 Rapid internalization in < 6 min of elliptical disks occurred when their long axis began to attach perpendicularly to cell membrane, causing a symmetrical spread of the membrane around the particle. In the meantime, attachment of the short-axis (flat) side of the particle to cell membranes did not induce observable phagocytic activities. This study concluded that phagocytosis or simple spreading on the particle was determined by the local particle shape at the point of initial contact by macrophages, not by size. Meanwhile, particle size dictated the completion of phagocytosis if the particle volume was larger than the macrophage volume. Other studies by the same group illustrated the maximum initial attachment of elongated particles, in the range of ca. 2–3 μm, to macrophage surface as compared with that of spherical particles, which was not directly related to their phagocytic uptake efficiency.72,73 Taken together, spheres or oblate ellipsoids may be most suitable for targeting macrophages (e.g., in the case of intracellular infections such as TB) via pulmonary administration, while elongated shapes may help to achieve prolonged blood circulation and avoidance of macrophage uptake, suitable for IV administration.

3.4 Effect of Particle Size and Surface Property on Translocation from the Lung to Extrapulmonary Compartments

The combined effects of size, surface charge, and NP composition on the ability to translocate from the lungs into the lymph nodes and bloodstream and on their in vivo fate were investigated following lung instillation in rats of inorganic/organic hybrid or organic NPs, engineered with varying chemical compositions, sizes and surface charges.74 The limited translocation of NPs with diameter greater than ca. 38 nm from the lung to extrapulmonary compartments of the body at 30 min after administration could be due to mucociliary and/or macrophage-mediated clearance. A small amount of the NPs < ca. 5 nm in diameter migrated rapidly to lymph nodes within 3 min, reached the kidneys and were ultimately excreted into urine by 30 min after administration. Only NPs with a size threshold of ca. 34 nm, regardless of chemical composition and shape, rapidly translocated from the alveolar luminal surface into the septal interstitium, the regional draining lymph nodes, and, finally, the bloodstream.

Notably, the biodistribution of NPs of size < ca. 34 nm was governed by charge effect, where zwitterionic, anionic, and neutral surfaces resulted in a higher transepithelial translocation, in contrast to the limited penetration of cationic NPs. NPs with size < ca. 6 nm and zwitterionic surface translocated from the alveolar airspaces to the bloodstream and were, finally, cleared via renal filtration. Based on these observations, the authors claimed that the use of non-cationic nanoparticles with the size range of ca. 6–34 nm would have the highest potential of achieving optimal delivery to the lungs via pulmonary administration route. With respect to this biokinetic analysis on the fate of intratracheally-instilled NPs, Kreyling et al. pointed out that quantitative investigation including a differentiation between transport to the blood through lymphatic drainage and direct translocation across the air-blood barrier to the blood should be pursued.75 Additionally, employing highly-functionalized NPs with targeting, therapeutic and diagnostic molecules may induce different consequences from the results observed here. Reineke et al. also compared the translocation and organ distribution of relatively larger PS NPs of ca. 50–900 nm in diameter upon pulmonary administration into mice.76 NP size influenced the rate and extent of NP uptake, in which larger NPs of ca. 250 or 900 nm displayed the highest total uptake (15% of administered dose) at 1 h, whereas smaller NPs of ca. 50 nm had the highest total uptake of ca. 24% at 3 h. The highest deposition of NPs of all sizes tested was found in the lymph nodes than other tissues, accounting for a total of ca. 35–50% of absorbed NPs.

3.5 Nanoparticle-In-Microparticles Formulations for Pulmonary Administration

Micron-sized particles can also be formulated and administered via the pulmonary route to reach the deep lungs. Ungaro et al. developed PLGA NPs of ca. 250 nm in diameter embedded in an inert microcarrier made of lactose, referred to as nano-embedded micro-particles, ranging from ca. 11–12 μm in diameter, as a pulmonary delivery system for tobramycin.77 In vivo biodistribution studies revealed that NP deposition was dependent on NP composition: chitosan (CS)-modified particles, having more difficult particle dispersion in the air flux than poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA)-modified counterparts, were found in the upper airways, lining lung epithelial surfaces whereas PVA-modified NPs reached the deep lung. However, surface coating with PVA could be problematic for penetration across mucus. Hanes et al. reported immobilization of PVA-coated PS NPs with speeds at least 4000-fold lower in fresh human cervicovaginal mucus (having similar biochemical and rheological properties as pulmonary mucus) than in water, regardless of PVA molecular weight (MW) or incubation concentration.78 Similarly, the transport of NPs of PLGA or PEG-b-PLGA coated with PVA also slowed at ca. 29000- and 2500-fold, respectively, compared to their uncoated counterparts.

Despite the promising results of nanoparticle-in-microparticles as pulmonary delivery carriers, particles of micrometer scale are prone to slow diffusion and to uptake by alveolar macrophages, which, consequently, may hamper their effectiveness as drug delivery carriers for inhalation administration.60

3.6 Effect of Size, Surface Charge, and Composition of Particles on Diffusion through Pulmonary Mucus

Size-dependent particle diffusion through the ca. 220 μm-thick mucus was investigated in vitro by De Smedt et al., where CF sputa almost completely blocked the transport of all tested PS-based spherical NPs of ca. 120–560 nm in diameter, having similar negative charges, ca. −50 mV, over 150 min.63 The mass percentage of NPs that diffused through CF sputum was ca. 1.3-, 6.8- and 42-fold smaller for 120-, 270-, and 560-nm NPs, respectively, as compared with their diffusion through buffer. The different transport rates of NPs of varying sizes was probably due to greater steric obstruction in the CF sputum, possessing pores ca. 100–400 nm in diameter, with increasing particle size. There was an interesting observation – a higher degree of NP diffusion through the more viscous sputum samples, which might be due to structural changes in CF sputum network (i.e., having a more macroporous structure when the sputum becomes more viscoelastic).

In addition to size, the diffusion of polymeric NPs in respiratory mucus is highly sensitive to NP surface characteristics. When comparing the mean diffusion coefficients of amine-modified and carboxylated PS particles, in the diameter range of ca. 100–500 nm, on transport in human CF sputum, amine-modified (neutrally-charged) NPs underwent more rapid transport than the carboxylated (negatively-charged) particles because of their reduced electrostatic adhesiveness.64 Similarly, De Smedt et al. reported the hindered mobility of charged NPs of ca. 100 nm or 200 nm in size, either positively or negatively charged, in bacterial biofilms and CF sputum, while their PEGylated neutral counterparts showed increased mobility.79 This particle surface chemistry-dependent mucus penetration was, in part, due to the altered rheological properties of the mucin network. Chin et al. found that positively-charged PS NPs could crosslink the mucin network, resulting in the formation of viscous mucus and impediment of mucin gel hydration.80 In contrast, carboxyl-functionalized counterparts enhanced the dispersion of aggregated mucin, perhaps due to the combined effects of electrostatic repulsion, chelation, reduction in intra/inter-mucin hydrogen bonding density, and network hydration. These results indicate the influence of NP surface charge on mucus penetration and transport during pulmonary administration.

The rapid penetration of polymeric NPs through highly viscoelastic mucus was demonstrated by coating them densely with low MW PEG, preventing the hydrophobic core of NPs from adhering to the hydrophobic domains of the mucin and minimizing the interaction between the neutral, non-mucoadhesive PEG-containing NP surface and the polyanionic mucus contents.81,82 Hanes et al. reported that PEG-coated NPs of ca. 100 and 200 nm in diameter rapidly penetrated respiratory mucus by ca. 15- and 35-fold than their uncoated counterparts, respectively, while NPs of size larger than ca. 500 nm in diameter were sterically immobilized by the mucus mesh.83 The densely PEG-coated PS NPs of ca. 200 nm in diameter displayed ca. 90-fold higher geometric mean effective diffusivity (Deff) due to their minimized interaction with CF sputum constituents, as compared to similarly sized, uncoated NPs.84–86

Importantly, the penetration of NPs of 200 nm in diameter across the CF sputum was more feasible when they were coated with PEG with MW between 2 and 5 kDa,86 whereas NPs coated with 10-kDa PEG were mucoadhesive.87 Transport of both coated and uncoated NPs in ca. 500 nm was hindered, this selective penetration, in agreement with another study,64 was partially due to the average 3D mesh spacing of CF sputum, i.e., ca. 140 ± 50 nm (range: 60–300 nm86 or 100–400 nm63).86 In the meantime, the smaller curvature of ca. 100 nm NPs did not appear to provide a sufficient PEG coating to be mucus inert, resulting in their more hindered transport in CF sputum as compared to ca. 200-nm NPs.

De Smedt et al. also demonstrated effective diffusion of PEG-coated NPs of ca. 200 nm in diameter across the P. aeruginosa biofilm extracellular polymeric substance matrix, in contrast to the hindered diffusion of their non-coated and charged counterparts.79 Interestingly, they observed ca. 15- and 400-fold lower Deff of ca. 200 and 500 nm PEG-coated particles, respectively, in CF sputum than in cervicovaginal mucus, demonstrating elevated adhesive and obstructive properties unique to the CF sputum mesh.25,26

Hanes et al. applied the PEGylation strategy to partially biodegradable polymeric NPs, composed of poly(sebacic acid) (PSA) and 5-kDa PEG.84 A rapid penetration of NPs of PSA-b-PEG, with an average hydrodynamic diameter of ca. 170 nm (i.e., a ca. 50-fold greater transport rate than uncoated counterparts at a time scale of 1 s) in sputum expectorated from the lungs of CF patients was ascribed to the efficient partitioning of the muco-inert PEG coating to the particle surface.

The surface modification of polyethylenimine (PEI)-based nanocomplexes with PEG has been broadly employed for pulmonary delivery of nucleic acids in CF to alleviate electrostatic association of cationic particulates with negatively-charged mucus constituents. Hanes et al. reported rapid penetration of highly compacted, densely PEG-coated DNA/PEI NPs in the human CF mucus ex vivo and mouse airway mucus ex situ.88 In addition to enhanced particle diffusion and distribution of gene carriers in mouse airways, densely PEG-coated DNA/PEI NPs delivered a full-length plasmid encoding the CF transmembrane conductance regulator protein in mouse lungs and airways, without causing acute inflammation or toxicity. In contrast, Kissel et al. observed only moderate gene expression in vivo and severe lung inflammation from PEG-grafted PEI/DNA despite its efficient transfection in cell culture.89

Optimization of the degree of PEGylation and PEG MW should be carefully executed for efficient mucosal drug delivery. For example, Saltzman et al. observed an improved diffusion, up to 10 times, of ca. 170 nm-PLGA NPs upon PEG surface coating in human cervical mucus, where their diffusion was strongly dependent on both PEG MW and density on the particle surface.90 Varying MW of PEG was tested to reduce the mucoadhesion of highly compacted DNA NPs, composed of single molecules of plasmid DNA complexed with PEG-block-poly(L-lysine) NPs (CK30PEG).91 Even though CK30PEG5k and CK30PEG10k DNA NPs displayed resistance to DNase I digestion and high gene transfer to the lung airways of mice after inhalation, immobilization of all CK30PEG DNA NP formulations in freshly expectorated human CF sputum could be ascribed to insufficient PEG surface density on the DNA NPs, as compared to the mucus-penetrating NPs of PS-b-PEG2k. Despite its popular use, recent data have also raised immunogenic concerns with PEGylation, including activation of the immune system and a loss of macrophage-escaping efficacy upon repeated administration.81,92

3.7 Surface Modification with Mucoadhesive Polymers

As summarized above, the prevailing paradigm in penetrating the human lung mucus secretions has been to employ non-adhesive polymers, such as PEG, at the surfaces of NPs.84,93 In contrast to this concept, Ungaro et al. employed hydrophilic mucoadhesive polymers, such as cationic CS and non-ionic PVA, to modulate interactions between NPs and mucus by increasing their residence time and intimate contact with the mucosa.77 Increased in situ residence of NPs with hydrophilic mucoadhesive polymers was observed, where CS-coated PLGA NPs showed a higher interaction with polyanionic mucus than PVA-engineered NPs due to their stronger electrostatic interaction. The mucoadhesive CS-engineered NPs penetrated the mucus more readily than the PVA-coated NPs in an artificial CF mucus model.

3.8 Application of Mucolytic Agents for Efficient Mucus Penetration

Beyond NP coating with non-mucoadhesive or mucoadhesive polymers, enhancement of particle penetration in the CF sputum could also be realized by lowering the viscosity of pulmonary secretions using mucolytic agents (e.g., recombinant human DNase (rhDNase) or N-acetyl cysteine (NAC)) before deployment of NPs containing active ingredients in the lungs.94,95 To reduce the barrier properties of sputum, proteolytic enzymes such as trypsin have been extensively studied as peptide mucolytics, but nonspecific serine proteolysis could be problematic. Hanes et al. combined the two strategies of applying NAC and modifying NP surface with PEG to synergistically avoid adhesive trapping and aggregation of the NPs in CF sputum.96 NAC hydrolyzes the disulfide bonds linking mucin monomers, resulting in depolymerization of mucin.25 NAC pretreatment enhanced penetration by the densely PEG-coated 200 nm NPs, with average speeds approaching their theoretical speeds in water. This rapid penetration correlated with increased average spacing between sputum mesh elements (i.e., from ca. 145 ± 50 to 230 ± 50 nm) upon NAC treatment. In contrast, uncoated NPs were trapped in NAC-pretreated CF sputum to the same extent as in native sputum, demonstrating the NAC-facilitated penetration of PEG-coated, muco-inert NPs.

Inhalation administration might allow for pulmonary absorption and deposition of therapeutic macromolecules, such as peptides and proteins, which otherwise must be injected. However, gene carrier diffusion across adhesive and hyper-viscoelastic sputum is challenging.17 Hanes et al. illustrated the enhancement of CF sputum penetration and airway gene transfer of compacted DNA NPs upon pre-treatment with NAC.97 Unlike the highly compacted DNA NPs of poly-L-lysine conjugated with 10-kDa PEG segment (CK30PEG10k/DNA NPs) trapped in CF sputum, pre-treatment of lungs with adjuvant regimens consisting of NAC or a combination of NAC and rhDNase increased the average effective diffusivities by ca. 6-fold and 13-fold, respectively, leading to a higher degree of sputum layer penetration of the gene carriers. Gene expression was enhanced up to ca. 12-fold with pre-treatment of intranasal dosing of NAC prior to application of CK30PEG10k/DNA NPs to the airways of mice with P. aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide-induced mucus hypersecretion, as compared to saline control. In another study, the same group highlighted an enhanced diffusion of adeno-associated virus gene vectors (AAV1) in CF sputum upon mucolytic therapy with NAC (i.e., rapid diffusion of > ca. 47% of the applied AAV1 in NAC-treated sputum vs. ca. 5% in untreated sputum).98 Collectively, these studies demonstrated the potential utility of adjuvant mucolytic therapy with NAC or a combination of NAC and rhDNase prior to administration of a NP gene carrier for promoting improved gene transfer.

3.9 Biodistribution of Degradable Particulates Delivered via Pulmonary Route

Biodegradable polymeric NPs have shown to have sufficient drug-loading capacity, sustained drug-release profile, ability to penetrate viscoelastic human mucus, and low immune toxicities.26,99 For example, a recent pharmacokinetic study by Wooley et al. demonstrated extended lung retention time for near-infrared (IR) dyes conjugated onto amphiphilic block copolymers comprising biodegradable polyphosphoester-based polymeric micelles and their stabilized, shell crosslinked knedel-like (SCK) analogs (e.g., lung extravasation half-life (t1/2) of ca. 4.2 and 8.3 days, respectively) as compared to the small-molecule near-IR probe (e.g., t1/2 of 0.2 days) upon their intratracheal administration in mice.100 It was also observed that lung retention of 111Ag was prolonged when 111Ag-radiolabeled species were loaded into similar amphiphilic block copolymer NPs.101 Although these biodistribution studies provided insights into the understanding of results of increased in vivo therapeutic efficacy,102 there were limitations in the conclusions that could be drawn. Those limitations require further consideration, theoretically and experimentally, in determining the fate of NPs by tracking the probes in terms of their biodistribution and pharmacokinetics because of the possible disassembly of polymeric NPs and subsequent undesired release of probe molecules from NPs, whether covalently conjugated or physically loaded.

Fattal et al. reported that PLGA NPs of different surface charges showed unique patterns of penetration across the mucus layer and internalization by the underlying epithelial cells.103 While the hydrophilic poloxamer (PF68)-coated NPs resulted in fast diffusion through the mucus layer and high internalization by the cells, the mobility of CS- and PVA-coated NPs was reduced due to interactions with the mucin chains. Decrease in transepithelial electrical resistance was observed only with CS-coated NPs because of their transient and reversible opening of the tight junctions. No increase of in vitro MUC5AC gene expression or the protein levels in the Calu-3 cells from all three NP formulations confirmed the non-impairment of the bronchial epithelial barrier.

Hsia and Nguyen et al. compared in vitro cell uptake and in vivo pulmonary uptake of naturally- and synthetically-derived biocompatible polymeric NPs for inhalational protein/DNA delivery.104 While all of six polymeric NPs (i.e. gelatin, CS, alginate, PLGA, PLGA-CS, and PLGA-b-PEG) were cyto-compatible and displayed dose-dependent uptake by type 1 alveolar epithelial cells, PLGA-based NPs had the highest cyto-compatibility and natural polymer NPs showed the highest in vitro uptake at specified concentrations. Upon a single inhalation of gelatin or PLGA NPs encapsulating yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) plasmid DNA or rhodamine-conjugated erythropoietin (EPO) into rat lungs, both NPs displayed a widespread EPO distribution for up to 10 days and increasing YFP expression for at least seven days. Overall, the authors favored PLGA and gelatin NPs as promising carriers for pulmonary protein/DNA delivery.

Upon intratracheal instillation of fluorescently-labeled, hydrophobically-modified glycol CS NPs of ca. 350 nm in diameter into mice, the NPs remained in the lungs for the first 24 h with the half-life of fluorescence intensity of ca. 130 h.105 While there was minor accumulation of NPs in extrapulmonary organs including liver, kidney, spleen, heart, salivary gland, mesenteric lymph node, accessory sex gland, testis, and brain, the fluorescence intensity was at its highest level in the lungs. The concentration of NPs in plasma displayed the maximum level at 1 h after instillation, and returned to control levels by day 7 (half-life in plasma ca. 42 h). The highest level of NP concentration excreted via urine appeared at 6 h after instillation.

In another pathologic examination of tissues after intratracheal instillation of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-encapsulated PLGA NPs of ca. 240 nm in average diameter, PLGA NPs remained in type 1 alveolar epithelial cells, alveolar spaces, and blood basement membrane for > 1.5 h after administration.106 Prompt transit through type 1 alveolar epithelial cells and resistance to uptake by macrophages (such as alveolar macrophages and Kupffer cells) were hypothesized, based on immediate detection of encapsulated FITC in the blood. However, tracking PLGA NPs by the detection of FITC has complications in concluding the fate of PLGA NPs due to the likelihood of premature release of free, diffusible FITC from NPs.

3.10 Effect of Particle Size and Surface Characteristics of Particles on Cellular Uptake and Internalization

The endocytosis of NPs is strongly dependent on their size and charge. In one study, the clathrin-mediated pathway of endocytosis showed an upper size limit for internalization of particles of ca. 200 nm in diameter, while NPs of greater size relied on caveolae-mediated internalization.35 In other examples, cationic NPs with larger diameter, in the range of ca. 80–250 nm, took a clathrin-dependent pathway107 and those < 25 nm in diameter became transported via non-clathrin mediated routes,108 while some particles may have used multiple pathways in parallel.109

PEGylation could be beneficial not only for enhancing penetration across the mucosal barrier and movement of administered NPs through human CF mucus but also for promoting entry into alveolar epithelial cells. Brody et al. demonstrated that PEGylation of cationic poly(acrylamidoethylamine-graft-poly(ethylene glycol))-block-polystyrene) (PEG-g-PAEA-b-PS)-based SCK NPs (cSCKs) of ca. 14–25 nm in diameter could alleviate inflammation and enhance entry and uptake of NPs into alveolar type II cells after intratracheal administration.110 With respect to the enhanced cell entry behavior of cSCKs modified with PEG grafts (1.5-kDa PEG) in lung alveolar epithelial cells and improved surfactant penetration, the authors speculated an altered mechanism of endocytosis of the NPs (i.e., clathrin-independent entry of PEGylated cSCKs as compared to clathrin-dependent entry of non-PEGylated cSCKs), helping to overcome physiological barriers in the alveolar epithelium. This study did not demonstrate an exact mechanism, which would be crucial to understand the effect of PEGylation of NPs on systemic delivery through the pulmonary route. Similarly, endocytosis of cationic non-PEGylated polysaccharide NPs of ca. 60 nm via the clathrin pathway was also observed by Betbeder et al.107

Based on the findings of PEG MW-dependent mucus penetration of CK30PEG DNA NPs in the lungs, Hanes et al. compared the intracellular trafficking of CK30PEG DNA NPs, having two different MWs of PEG, 5 or 10 kDa, in BEAS-2B human bronchial epithelial cells.111 Both CK30PEG5k and CK30PEG10k DNA NPs were able to escape degradative endolysosomal trafficking by entering the cells via a caveolae-mediated pathway, with slower transport, ca. 3- to 8-fold in BEAS-2B cells, compared to clathrin-mediated endocytosis of PS NPs of 100 nm. Rapid accumulation of the two types of NPs in the perinuclear region of cells was shown within 2 h, ca. 38 and 48%, respectively. Meanwhile, there was no significant effect of PEG MW on NP morphology and intracellular transport.

In a study of differential uptake of PS-based particles by human alveolar type 1 cells and primary human alveolar type 2 cells, Kemp et al. found that surface charge, rather than size, could be a key parameter for cell internalization.112 While particles of ca. 50 nm and 1 μm in diameter were internalized in equal numbers, more internalization of negatively-charged particles occurred at a significantly higher rate, ca. 4.4-fold at 30 min, as compared to positively-charged particles. Similarly, Kissel et al. observed higher in vitro cell internalization of anionic NPs of branched polyester, diethylaminopropyl amine-poly(vinyl alcohol)-graft-poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (DEAPA-PVAL-g-PLGA) in the size range of ca. 70–250 nm, despite their low rate of in vitro A549 cell association due to electrostatic repulsion between the anionic NPs and the cell membrane.113 Opposite results were observed with the cationic counterparts, which exhibited high electrostatic affinity for the membrane, albeit without evidence of internalization.

3.11 Effect of NP Surface Charge and Hydrophobicity on Toxicity

The surface charge and hydrophobicity of NPs are important determinants of inducing in vivo respiratory toxicity (tissue damage, cytokine release, etc.). Benita et al. reported NPs possessing negative surface charge, rather than those with positive surface charge, would be suitable as drug carriers for local delivery following repeated local pulmonary instillation.114 When they assessed local and systemic effects of PEG-b-PLA NPs as a function of surface charge following repetitive instillation in a murine model, anionic NPs of ca. 120 nm in diameter and ca. −30 mV in zeta potential showed reduced local inflammation as compared to cationic NPs of ca. 140 nm in diameter and ca. +30 mV in zeta potential. Increased pulmonary side effects and transient systemic toxicity observed with cationic NPs were attributed to a higher propensity of being captured and bound to sputum components than anionic counterparts. In another study, Fattal et al. compared in vitro cytotoxicity and inflammatory response on A549 human lung epithelial cells to three different types of PLGA NPs of ca. 230 nm in diameter, using different stabilizers (i.e., neutrally-charged PVA, positively-charged CS or negatively-charged PF68).115 While neither significant cytotoxicity nor inflammatory cytokine release was induced by these PLGA NPs on a Calu-3-based model of bronchial epithelium, the higher tendency of internalization and cell metabolic activity of PF68-coated PLGA NPs may underlie their high toxicity among the tested constructs.

Forbes and Dailey et al. related the NP surface hydrophobicity of three different biomaterial types (i.e., PS, poly(vinyl acetate) (PVAc), and PEGylated lipid nanocapsules of either ca. 50 or 150 nm in diameter) to acute respiratory toxicity following pulmonary administration.116 NPs with higher hydrophobicity (i.e., PS and PVAc) induced acute respiratory toxicity upon single-dose administration, being retained in the surfactant monolayer and inhibiting surfactant function,117 whereas PEGylated lipid nanocapsules with lower hydrophobicity caused little or no inflammation. Collectively, optimization of surface hydrophobicity should be carefully considered for design of safe pulmonary nanomaterials.

4. Antimicrobial Nanoparticles

4.1 Silver-based Antimicrobial-bearing System

Cannon and Youngs et al. developed nebulizable L-tyrosine polyphosphate (LTP) NPs of ca. 920 nm in diameter, encapsulating silver-based antimicrobials (i.e., silver N-heterocyclic carbene complex (SCC10)) for treatment of the CF-relevant pathogen P. aeruginosa.118 Silver is highly biocidal against a wide range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus, P. aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli.119,120 The SCC10-loaded LTP particles of ca. 1200 nm in diameter showed potent in vivo antimicrobial efficacy, ca. 75% survival rate, against P. aeruginosa over the course of several days with only two administered doses over a 72 h period. Fre chet and Cannon et al. then devised smaller, ca. 100 nm in diameter, nebulizable acetalated dextran NPs (Ac-DEX NPs)encapsulating a hydrophobic SCC.121 Silver loading capacity of Ac-DEX NPs was increased with an increasing initial feed up to ca. 30%, resulting in encapsulation efficacy up to ca. 65%. Ac-DEX NP formulations demonstrated activity in vitro against P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and E. coli, including the silver-resistant strain E. coli J53/pMG101.

In parallel, benefiting from polymeric formulation with precisely controlled architectures, surface characteristics, and supramolecular assembly, Cannon, Youngs, and Wooley et al. designed nebulizable, multifunctional SCK NPs of poly(acrylic acid)-block-polystyrene (PAA-b-PS) that were loaded with silver cations and/or SCCs.102 Antimicrobial efficacy of SCK NPs (shell-loaded with silver cations, core-loaded with SCC10, or loaded via both strategies) was evaluated in a mouse pneumonia model of P. aeruginosa. Two SCK NP formulations with SCC10 loaded in the core displayed superior antimicrobial activity and efficacy compared to shell-loaded SCK NPs, probably due to the stability of SCC10 allowing for sustained delivery of the encapsulated SCCs. The Ag+ dosage required to achieve ca. 60% survival rate from SCC10-loaded SCK NPs was 16 times less than that required from the free drug, at 12 h intervals. Interestingly, SCK NPs with shell-loaded silver cation did not show good efficacy in vivo, perhaps due to the relative susceptibility of the weakly complexed Ag+ to precipitation with Cl− or other counter-ions and/or its reduction to Ag0. In spite of promising in vitro and in vivo antimicrobial efficacy data, translational concerns remained regarding long-term in vivo accumulation and possible toxicity that may be elicited by the non-degradable NPs.

To address these limits, two new series of potentially fully-degradable polymeric NPs, composed of phosphoester and/or L-lactide, have been designed specifically for silver loading into the hydrophilic shell and/or the hydrophobic core, as potential delivery carriers for three different types of silver-based antimicrobials – silver acetate or two SCCs.122 Silver-loading capacities of these NPs reached up to ca. 12% (w/w), and kinetic studies of silver-bearing NPs revealed ca. 50% release at 2.5–5.5 h, depending on the type of silver compound loaded. Interestingly, packaging of SCCs in the NP-based delivery system enhanced MICs up to ca. 70%, compared with the SCCs alone, as measured in vitro against ten contemporary epidemic strains of S. aureus and eight uropathogenic strains of E. coli. Meanwhile, degradability of these NPs was demonstrated by assessing the rates of hydrolytic or enzymatic degradation, by structural characterization of the degradation products, and by biological assays.

Cannon and Wooley et al. developed another type of degradable polyphosphoester-based silver-bearing NPs, composed of amphiphilic block terpolymer, poly(2-ethylbutoxy phospholane)-block-poly(2-butynyl phospholane)-graft-poly(ethylene glycol), for potential treatment of bacterial lung infections.123 Loading of antimicrobial silver cations was possible via the formation of silver acetylides with different coordination geometries, which allowed for up to ca. 15% (w/w) loading and a sustained release over five days. These silver-bearing NPs displayed enhanced in vitro antibacterial activities against a series of CF-associated pathogens, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and Burkholderia spp., and decreased cytotoxicity to human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro, in comparison to free silver acetate.

4.2 Other Antimicrobial Polymeric Systems

Nebulization of PLGA NPs, in the size range of ca. 190–290 nm, containing three different anti-tubercular drugs (i.e., rifampicin, isoniazid, or pyrazinamide) showed superior drug bioavailability and reduced dosing frequency for management of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected guinea pigs, compared with oral and IV administration of the parent drugs.124 Upon a single nebulization of drug-loaded PLGA NPs, a therapeutic drug level was sustained in plasma for 6–8 days and in the lungs for up to 11 days. The increased relative bioavailability, by ca. 13-, 33-, and 15-fold for rifampicin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide, respectively, was ascribed to prolonged elimination half-time and residence time upon nebulization of the drug-encapsulated NPs, as compared to oral administration of the parent drugs. In another study by the same group, treatment with only five doses of drug-loaded PLGA NPs at 10-day intervals to M. tuberculosis-infected guinea pigs was sufficient for clearance of tubercle bacilli in the lung, whereas 46 daily doses of orally administered drugs were required to achieve equivalent therapeutic efficacy.125 Rifampicin was formulated into aggregated PLGA NPs of ca. 190 nm in size, namely porous NP-aggregate particles (PNAPs), suitable for aerosol delivery 126 The systemic level of rifampicin delivered to guinea pigs following intratracheal insufflation of PNAPs was detectable for six to eight hours whereas the free drug, delivered without NPs, was not detected even in the lungs at eight hours. The authors speculated that the prolonged residence of PNAP-delivered rifampicin in the lungs was due to the association of drugs with alveolar macrophages or with remaining intact particles in the lungs. However, it will be important to study the fate of PNAPs after pulmonary administration, including macrophage uptake and mucus penetration of particles. When compared with oral administration at equivalent doses, pulmonary administration of PNAPs to guinea pigs resulted in higher and longer rifampicin plasma concentrations, demonstrating the advantage of pulmonary delivery over oral administration.

A combination of enhanced interaction of anti-TB drugs with M. tuberculosis-infected phagocytes and controlled drug release into the infected tissues would be desirable to treat TB effectively.127,128 Báfica et al. claimed that a direct interaction of PLGA NPs (ca. 180 nm in diameter) carrying an anti-mycobacterial drug, E-N2-3,7-dimethyl-2-E,6-octadienylidenyl isonicotinic acid hydrazide (JVA), with M. tuberculosis led to high activity against extracellular and intracellular mycobacteria.129 With significant loading efficiency of JVA in PLGA NPs, up to ca. 80%, association of JVA-loaded NPs with mycobacterial cell walls contributed to enhanced M. tuberculosis killing inside macrophages, although the mechanism by which JVA-NPs gained access to M. tuberculosis was not clear.

4.3 Lipid-Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticle System

Lipid-polymer hybrid NPs exhibit complementary characteristics of both structural integrity of polymeric NPs and highly biocompatible nature of lipids in liposomes. To improve the biocompatibility and cellular affinity of polymeric NP cores, PLGA is often incorporated into lipid shells.130 Chono et al. investigated the influence of particle size of liposomes on drug delivery to alveolar macrophages in rats following pulmonary administration. They observed enhanced antibiotic delivery efficiency of PLGA-containing liposomes with increase in the particle size over the range of ca. 100–1000 nm.131 Hadinoto et al. compared the effect of phosphatidylcholine-coated, lipid-polymer hybrid NPs of ca. 300 or 420 nm in size, encapsulating a fluoroquinolone antibiotic, levofloxacin, against P. aeruginosa biofilm cells in vitro, with PLGA NPs of ca. 240 nm in size.132 The presence of the lipid coat contributed to the gradual release of the highly water-soluble levofloxacin over 24 h. Although their affinity toward P. aeruginosa biofilms was not improved, the hybrid NPs exhibited a ca. 50-fold increase in anti-pseudomonal biofilm affinity over their non-lipid-coated counterparts. Differences in antibiotic activity, release rate, and biofilm cell detachment between uncoated and lipid-coated polymeric NPs were ruled out as contributing factors to the higher anti-biofilm efficacy of the hybrid NPs; the mechanisms for anti-biofilm enhancement in the lipid-polymer hybrid NPs are yet to be identified.

5. Smart Polymeric Nanoparticles

In addition to the advantage of nanosized formulation, polymeric NPs take advantage from their capability to incorporate multi-functional “smart” ingredients, such as responsiveness to a stimulus, allowing for controlled drug release at specific sites or under applied conditions.28 Such triggers might include internal stimuli (e.g., reducing environment in the cytosol or endosome) or external stimuli (e.g., temperature, ultrasound, magnetic field, or light).

5.1 pH-Responsive Polymeric Nanoparticles

Gene therapy via the respiratory tract has gained much attention for the treatment of lung diseases.25 Hanes et al. formulated pH-responsive rod-shaped PEG-CH12K18 DNA NPs of poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(L-histidine)-block-poly(L-lysine) (PEG-CH12K18) to transfect cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis while overcoming inefficient endosomal escape of DNA NPs of PEG-CK30., as observed in other studies82,133,134. Incorporation of functional groups, L-histidine, having buffering capacity between pH 5.1–7.4, was designed to facilitate endo-lysosomal escape via the proton sponge effect.135 While the terminal PEG chains retained a neutral surface charge, poly(L-histidine) buffered the pH without interfering with DNA compaction by poly(L-lysine). The endowed buffering capacity by insertion of poly(L-histidine) enhanced their gene transfer efficiency without affecting their physicochemical properties. The authors claimed that this gene transfer was mediated via clathrin-dependent endocytosis followed by endolysosomal processing, as compared to the nucleolin-dependent entry of PEG-CK30 DNA NPs. PEG-CH12K18 DNA NPs displayed enhanced in vitro gene transfer by ca. 20-fold over plasmid DNA NPs of PEG-CK30, and in vivo gene transfer to lung airways in BALB/c mice by ca. 3-fold at 14 days post administration.

Farokhzad et al. developed vancomycin-encapsulated, pH-responsive, and surface charge-switching NPs of ca. 200 nm in size of triblock copolymer, poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid)-block-poly(L-histidine)-block-poly(ethylene glycol) (PLGA-b-PLH-b-PEG), potentially for targeting bacterial cell walls at acidic sites of infection.136 The overall positive charge on the NP surface upon protonation of imidazole groups on the PLH block segment in acidic pH promoted multivalent electrostatic-induced cell binding capability and drug delivery efficiency. In contrast, cell binding affinity and drug delivery efficiency were partially limited at pH 7.4. NP binding to bacteria at pH 6.0 increased at ca. 3.5-fold for S. aureus and ca. 5.8-fold for E. coli as compared with those at pH 7.4. At pH 6.0, a loss of antimicrobial efficacy of vancomycin within NPs of PLGA-b-PLH-b-PEG was minimal (i.e., ca. 1.3-fold increase in MIC against S. aureus) as compared to that of free vancomycin and vancomycin-encapsulated NPs of PLGA-b-PEG (i.e., ca. 2.0- and 2.3-fold increase, respectively). Further study on selective targeting of these charged NPs toward bacteria surrounded with negatively-charged host cell membranes at sites of infection should be conducted.

5.2 Enzyme-Responsive Polymeric Nanoparticles

Development of respirable particulates with adequate daer that can confer deposition in the deep lung, evasion from macrophage uptake, and rapid penetration into mucus is one of the major challenges in inhalation therapy. Several efforts, including hydrogel MPs with desired respirable daer when dry but enlargement and swelling upon deposition in the moist lung, were made, but those systems were limited to micron-sized carriers.137,138 Roy et al. developed a multi-tiered two-stage system, nanoparticle-in-microgel, that was designed to fulfill these requirements on daer.139 The swelling of the microgels of ca. 1.9 μm in average geometric diameter in PBS buffer for 24 h allowed for a highly porous internal structure and geometric diameter > ca. 6 μm, providing optimal aerodynamic carrier size for deep lung delivery. Macrophage uptake of the pre-swelled microgels was effectively avoided in vitro, only ca. 12% uptake after 24 h, which was attributed to the hydrophilic and swellable nature of microgels. The enzymatic degradability of the microgels was derived from a trypsin-sensitive di-sulfhydryl peptide (CGRGGC) introduced as a crosslinker in four-arm-PEG-acrylate-10 kDa. A triggered burst release of various types of encapsulated compounds was observed within 30 min upon addition of physiological levels of trypsin, whereas they were retained in the absence of enzyme.

Wang et al. developed a strategy of differential delivery of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections, using a bacterial-lipase sensitive polymeric triple-layered nanogel (TLN) as the nanocarrier.140 The TLN of ca. 430 nm in diameter and ca. −20 mV in zeta-potential was composed of three compartments: crosslinked polyphosphoester core, bacterial lipase-sensitive poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) interlayer, and PEG shell. The presence of PCL prevented premature drug leakage or non-specific drug release in aqueous solution by surrounding the drug reservoir prior to reaching the sites of bacterial infection. Upon contact with bacterial lipases abundant in microbial flora, degradation of the PCL interlayer induced the release of encapsulated antibiotics. Encapsulated vancomycin was almost completely released from the TLN within 24h only in the presence of lipase-secreting S. aureus, thereby achieving targeted inhibition of S. aureus growth. This approach could be applied to on-demand delivery of antibiotics for the treatment of a variety of infections caused by lipase-secreting bacteria.

6. Use of Red Blood Cells as NP Delivery Carriers Targeting the Lung

As delivery vehicles in the circulatory system, unique characteristics of red blood cells (RBCs), including permeability to biological barriers and expression of ligands (e.g., CD47 and CD300) that bind to inhibitory receptors expressed by macrophages, make RBCs intriguing.28,142 Mitragotri et al. demonstrated “cellular hitchhiking” of polymeric NPs onto RBCs to avoid MPS clearance and thereby improving the accumulation of NPs in lungs.143 Reversible, non-covalent attachment of spherical PS NPs of ca. 200 or 500 nm in diameter to RBCs was possible via electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. For instance, RBCs carried about 24 NPs of ca. 200 nm in diameter per cell at a particle/RBC feed ratio of 100:1. Upon IV administration, NP desorption occurred rapidly, likely due to shear or direct RBC-endothelium contact during their transit through the tissue microvasculature.144 As a result, ca. 6% of NPs remained on the surface of RBCs in circulation after 30 min. The significant factors affecting the rate of NP detachment appeared to be the size and geometry of vasculature and the location of NP attachment to RBCs. The RBC-adsorbed NPs exhibited blood persistence ca. 3-fold higher than free NPs over 24 h, leading to ca. 7-fold higher accumulation in lungs. A distinct accumulation profile of RBC-adsorbed NPs in the lungs was observed (i.e., ca. 15- and 10-fold of improvement of lung/liver and lung/spleen NP ratios, respectively). The authors speculated that accumulation of NPs in the lungs was due to mechanical transfer of NPs from the RBC surface to lung endothelium. In contrast, uptake of NPs attached to RBCs was reduced in mononuclear phagocytic organs such as liver and spleen. Conjugation of anti-ICAM-1 antibody to the RBC-adsorbed NPs increased lung targeting and retention over a period of 24 h, indicating a transfer of NPs from RBCs to endothelium in the vasculature. The RBC-mediated circulation time of NPs could be further controlled by modifying NP surface characteristics or by endowing NPs with binding specificity toward RBCs.

7. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs) for Pulmonary Delivery

Targeted aerosol delivery of superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs (SPIONs), nanomagnetosols, to specific lung regions other than the airways or the lung periphery in combination with a target-directed magnetic gradient field was demonstrated by Rudolph et al.145 When an aqueous suspension of nanomagnetosols was nebulized via intratracheal intubation to mouse lungs, ca. 3-fold higher lung deposition of SPIONs was achieved under application of the magnetic field. When the magnet’s tip was centered directly above the right lung lobe, ca. 8-fold higher relative SPION deposition in the right lobe was observed as compared to that in the left lobe. The potential use of nanomagnetosols in the targeted aerosol drug delivery system was then demonstrated by formulation of plasmid DNA (pDNA) with the SPIONs. Nebulization of the pDNA-SPIONs inure to the lungs of intact mice in the presence of a magnetic field resulted in a ca. 2-fold higher dose of pDNA in the magnetized right lung than in the unmagnetized left lung. Based on these results, application of nanomagnetosols to polymeric NPs could be utilized for targeted delivery towards a desired lung region in vivo by a properly positioned magnetic field.

8. Summary: Chemical design and future directions

Physical and chemical properties determine the lung deposition, mucus penetration and subsequent biodistribution of administered therapeutic NPs (Figure 2). For example, daer of NPs is known to be the major physical parameter that influences their deposition site in the lungs, but upon deposition in the lung, combined effects of size and surface properties, such as hydrophilicity and charge, regulate subsequent transport in the mucus and to the epithelial surface. In the design of polymeric NPs for pulmonary delivery, these strategies should be accounted for to maximize their efficacy. The following sections focus on the particle features in nanometer scale that allow for delivery of therapeutics via pulmonary route.

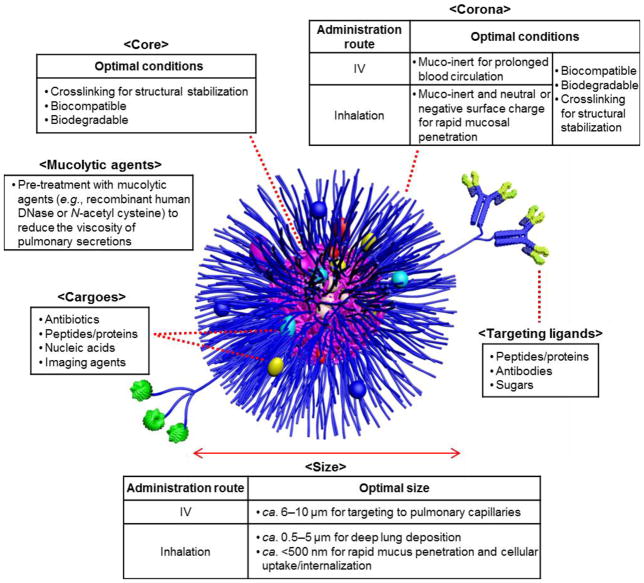

Figure 2.

Rational design of multifunctional polymeric NPs as delivery carriers for intravenous or pulmonary administration based on the published/introduced data.

8.1 Size

In the rational design of drug carriers for pulmonary delivery, there are several conflicting requirements for optimal daer of particles: (a) between ca. 500 nm and 5 μm to achieve deep lung deposition, (b) < ca. 500 nm or > ca. 6 μm and hydrophilic surface chemistry to avoid rapid clearance by alveolar macrophages, and (c) < ca. 200 nm for efficient mucus penetration and intracellular drug delivery.16,26,33,137 To meet these conflicting restrictions on daer, nanometer-sized particles have been assembled in micrometer-sized aggregates.77

Once deposited in the lungs, transport of polymeric NPs is strongly dependent on the particle size and surface charge. NPs should be sufficiently smaller than ca. 200 nm, and coated with low MW stealth-like polymer chains, to overcome steric hindrance dictated by the mucus pores and the particulate interactions with the respiratory mucus contents.83,86 However, cationic NPs of size smaller than ca. 34 nm showed lower transepithelial translocation from the lung than zwitterionic, anionic and neutral NPs.74,110

8.2 Target/Binding Specificity

Introducing a mechanism to mediate a target-specific binding and/or triggered-drug release at the disease sites would enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects on normal tissues.146,147 Although enhanced lung delivery by immuno-targeting the pulmonary endothelium with antibodies has been demonstrated following IV treatment,148–152 the role of biomacromolecules as auxiliary devices for localized NP delivery via inhalation administration for treatment of pulmonary infections remains poorly understood.

Meanwhile, enhanced uptake of NP formulations by alveolar macrophages, which express mannose receptors, could be realized by modifying the particle surface with mannose.153 Chono et al. reported enhanced targeting efficiency to rat alveolar macrophages following pulmonary administration of mannosylated liposomes with 4-aminophenyl-a-D-mannopyranoside, which could be useful for the treatment of respiratory intracellular parasitic infections.154

8.3 Shape

Particles with various morphologies and/or aspect ratios may have different therapeutic loading capacities, in vivo fate, and toxicity. There is currently great effort to study the effect of particle shape and dimensions on cellular internalization and intracellular tracking, and phagocytosis both in vitro and in vivo, led particularly by DeSimone et al. and Mitragotri et al.39,43,73,155–157 Recent studies by DeSimone et al. demonstrated non-inflammatory response, homogenous lung distribution, increased lung residence time, and/or size-dependent macrophage uptake of donut and cylinder hydrogels in varying sizes upon instillation into the lungs of mice.70,71 These results suggest that careful design and control over physical parameters of polymeric NPs will optimize their effective delivery of therapeutics to the lungs.

8.4 Surface Characteristics of NPs

Because of the presence of highly branched and negatively charged mucus glycoproteins of CF sputum overlying epithelial cells in the conductive airways and the higher tendency to provoke pulmonary inflammation by positively-charged polymeric NPs, it is generally accepted that the anionic or neutral surface characteristics of particulates would be optimal for pulmonary administration.158 In particular, coating of NPs with inert polymers such as PEG showed promising results in penetrating into the highly viscoelastic human mucus secretions, minimizing adhesive interactions of NPs with mucus and protecting them against clearance by alveolar macrophages.25,26

8.5 Pre-Treatment of Mucus with Mucolytic Agents

Beyond modifying the surface chemistry of NPs, addition of mucolytic agents (e.g., rhDNase and NAC) can improve the mucus penetration of polymeric NPs by decreasing the mucus viscosity.159 Examples included a ca. 3-fold improvement in the diffusion of NPs across the mucus upon addition of rhDNase demonstrated by De Smedt et al.,63 ca. 13-fold increase in NP diffusion velocity in the presence of NAC showed by Hanes et al.,96 formation of more homogeneous mucus pores leading to uniform NP diffusion velocities upon addition of rhDNase as highlighted by Hanes et al,64 and improved penetration of DNase-functionalized NPs into CF sputum by Scott et al.160 Careful selection of mucolytic agents is required because of possible inhibition of other mucolytics in combined pre-treatment strategies.161

8.6 Degradability of NPs

To address the concerns about immunotoxicity and long-term accumulation, use of biodegradable polymeric NP formulations is of critical importance,16,162 as evidenced by reduced inflammation in the murine lung after intratracheal instillation of PLGA-based NPs of ca. 75 and 220 nm in diameter as compared to the PS-based non-biodegradable counterparts of comparable size by Kissel et al.162 Among other studies, CS- or PVA-modified PLGA NPs also did not show significant cytotoxicity to cultured lung epithelial cells.115,163

Despite extensive use of PLGA formulation in the inhaled delivery of therapeutics due to its biodegradability and biocompatibility, several factors, including its acidic degradation products, relatively slow hydrolysis rates, absence of functional moieties, and high degree of hydrophobicity, are detrimental for its use in pulmonary drug delivery.114,164 Faster degradation rate of the PLGA component could be accomplished by preparing hydrophilic derivatives of PLGA, whereby increasing water saturation within the particles would promote hydrolytic degradation.113,165,166

An alternative aerosolized particle system of degradable polymer, polyketals, producing non-acidic degradation products upon hydrolysis was developed as a pulmonary delivery method by Baker et al.167 Even though the polyketal-based particles were micron-sized (ca. 1.5—2.5 μm in diameter), they displayed no detectable alveolar or airway inflammation upon intratracheal instillation. Other classes of degradable NPs developed for pulmonary drug delivery include poly(ether-anhydrides),168,169 polyphosphoesters,122,123 polycarbonates, etc., and more comprehensive functional and toxicological studies are still needed with these systems.

8.7 Concluding Remarks

Polymeric NPs have been developed as effective carriers for delivery of various therapeutics and/or diagnostics for management of pulmonary infections due to their abilities to overcome drug resistance and to improve pharmacokinetics and biodistribution profiles of the administered drugs, thereby maximizing direct delivery and retention at the sites of infection while minimizing systemic exposure. Smart features also enable NPs to selectively release the loaded cargoes in specific microenvironments, disease sites, or other target sites in the body. However, there remain several challenges in the development of clinical nanomedicines for treatment of lung infections, including those associated with the conditions experienced during circulation and/or upon reaching the lung environment. For example, Dawson et al. raised concern over possible loss of the intended targeting capability of functionalized NPs in a biological environment.170 In this study, the uptake of fluorescent silica NPs (SiO2-PEG) conjugated with human transferrin (Tf), a transferrin receptor (TfR)-binding glycoprotein, in different types of serum was evaluated. The presence of fetal bovine serum reduced both the TfR-non-specific and specific uptakes, demonstrating the total loss of TfR target specificity, depending on the type of serum. The authors postulated that this diminished target specificity of Tf-conjugated NPs arose from interactions with other proteins in the medium and the formation of a protein corona. This work highlights the significance of careful evaluation of the recognition, interactions and fates of bio-conjugated NPs in a complex biological milieu. Recognition of the presence of a protein corona has become more prevalent, with significant enhancements in studies and techniques to evaluate the stability of synthetic NPs in the presence of biological macromolecules, including the kinetics and thermodynamics of the formation and dynamic remodeling of protein corona.171–175 There is much effort to minimize non-specific interactions with biological macromolecules while promoting selective binding to receptors, the content of which has formed the basis of entirely separate review articles.28,146,176–178

In addition, promising results upon in vitro treatment in cell culture or in vivo administration in animal models may not guarantee the same outcomes in clinical trials. Hence, in vitro characterization data such as cytotoxicity, sputum penetration, and cellular uptake of medicated NPs should be validated with in vivo experiments for initial evidence that they can be tested under clinical settings. Although NPs have demonstrated significant potential in the treatment of lung infectious diseases, our current understanding of the complex interactions of the polymeric nanotherapeutics and the human body remains incomplete. Finally, lessons learned in the development of pulmonary NPs can be increasingly applied to NP administration at other epithelial sites, such as the gut, skin, and urinary tract. Such local administration is conceptually attractive due to diminished systemic effects of therapy, but each of these epithelial sites carries specific considerations for NP delivery optimization, such as mucus layers, immune cell populations, and other interacting moieties. Continued investigation at these various epithelial interfaces will inform the development of NP-based local therapies for common infections as well as for other epithelial diseases.

Table 1.

General Effect of Particle Characteristics (e.g., Size, Shape, and Surface Properties) on the Deposition and Distribution upon IV Administration

| Factors | Particle size (in diameter) | Effects on NP biodistribution |

|---|---|---|

| Particle size (spherical) | < 5 nm |

|

| 5 nm–15 μm |

|

|

| > 15 μm |

|

|

| Particle shape | Discoidal or filamentous (vs. spherical) |

|

| Particle surface | PEGylation |

|

Table 2.

General Effect of Particle Characteristics (e.g., Size, Shape, and Surface Properties) on the Deposition and Distribution upon Pulmonary Administration

| Particle Characteristics | Remarks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Deposition pattern in the lungs | 5–10 μm | Upper airways (mouth, trachea, and primary bronchi) | |