Abstract

Mutations in striated muscle contractile proteins have been found to be the cause of a number of inherited muscle diseases; in most cases the mechanism proposed for causing the disease is derangement of the thin filament-based Ca2+-regulatory system of the muscle. When considering the results of experiments reported over the last 15 years, one feature has been frequently noted, but rarely discussed: the magnitude of changes in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity due to myopathy-causing mutations in skeletal or heart muscle seems to be always in the range 1.5–3x EC50. Such consistency suggests it may be related to a fundamental property of muscle regulation; in this article we will investigate whether this observation is true and consider why this should be so. A literature search found 71 independent measurements of HCM mutation-induced change of EC50 ranging from 1.15 to 3.8-fold with a mean of 1.87 ± 0.07 (sem). We also found 11 independent measurements of increased Ca2+-sensitivity due to mutations in skeletal muscle proteins ranging from 1.19 to 2.7-fold with a mean of 2.00 ± 0.16. Investigation of dilated cardiomyopathy-related mutations found 42 independent determinations with a range of EC50 wt/mutant from 0.3 to 2.3. In addition we found 14 measurements of Ca2+-sensitivity changes due skeletal muscle myopathy mutations ranging from 0.39 to 0.63. Thus, our extensive literature search, although not necessarily complete, found that, indeed, the changes in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity due to disease-causing mutations have a bimodal distribution and that the overall changes in Ca2+-sensitivity are quite small and do not extend beyond a three-fold increase or decrease in Ca2+-sensitivity. We discuss two mechanism that are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Firstly, it could be that the limit is set by the capabilities of the excitation-contraction machinery that supplies activating Ca2+ and that striated muscle cannot work in a way compatible with life outside these limits; or it may be due to a fundamental property of the troponin system and the permitted conformational transitions compatible with efficient regulation.

Keywords: muscle regulation, Ca2+-sensitivity, troponin C, HCM, DCM, myopathy, mutation

Mutations in striated muscle contractile proteins have been found to be the cause of a number of inherited muscle diseases; in most cases the mechanism proposed for causing the disease is derangement of the thin filament-based Ca2+-regulatory system of the muscle. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and hypercontractile diseases of skeletal muscle, such as distal arthrogryposis and “stiff child syndrome,” have been linked to a higher myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity (Marston, 2011; Donkervoort et al., 2015). In contrast dilated cardiomyopathy mutations are commonly, but not exclusively, linked to decreased Ca2+-sensitivity. Mutations in contractile proteins that are linked to nemaline myopathy and related skeletal muscle myopathies have also been found to be associated with reduced Ca2+ sensitivity (Marttila et al., 2012, 2014). The causative connection between myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity and muscle dysfunction is a field of intensive research that is too complex to consider in this account. However, when considering the results of such experiments reported over the last 15 years, one feature has been frequently noted, but rarely discussed. The magnitude of changes in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity due to myopathy-causing mutations in skeletal or heart muscle seems to be always in the range 1.5–3x EC50. Such consistency suggests it may be related to a fundamental property of muscle regulation; in this article we will investigate whether this observation is true and consider why this should be so.

Most investigations have found increased Ca2+-sensitivity in muscle with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM)-causing mutations. Our literature search found 71 independent measurements of the mutation-induced change of EC50 ranging from 1.15 to 3.8-fold with a mean of 1.87 ± 0.07 (sem) (Table 1). We also found 11 independent measurements of increased Ca2+-sensitivity due to mutations in skeletal muscle proteins ranging from 1.19 to 2.7-fold with a mean of 2.00 ± 0.16 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Effect of HCM-associated mutations on myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity.

| Gene name | Mutation | wt/mutant EC50 ratio | Measured in | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCM | ||||

| ACTC | E99K | 2.45 | IVMA | Song et al., 2011 |

| ACTC | E99K | 1.24 | IVMA (human) | Song et al., 2011 |

| ACTC | E99K | 1.89 | IVMA | Papadaki et al., 2015 |

| ACTC | E99K | 1.3 | Fibers TG | Song et al., 2011 |

| ACTC | E99K | 2.35 | Myofibrils TG | Song et al., 2013 |

| MYL2 | R58Q | 1.29 | Fibers X | Szczesna-Cordary et al., 2004 |

| MYL2 | D166V | 1.78 | Fibers TG | Kerrick et al., 2009 |

| MYL2 | D166V | 1.82 | Fibers TG | Yuan et al., 2015 |

| MYH7 | R403Q | 1.79 | Human fibers | Sequeira et al., 2013 |

| MYH7 | R403Q | 1.41 | Fibers TG | Blanchard et al., 1999 |

| MYH7 | R453C | 1.99 | Human fibers | Palmer et al., 2004 |

| MYBPC3 | Cat R820W | 2.01 | IVMA | Messer et al., 2016a |

| MYBPC3 | “KI” | 1.35 | Fibers TG | Fraysse et al., 2012 |

| MYBPC3 | E258K | 1.80 | Human fibers | Sequeira et al., 2013 |

| TNNC1 | A8V | 2.51 | Fibers TG | Martins et al., 2015 |

| TNNC1 | A8V | 2.3 | Fibers X | Pinto et al., 2009 |

| TNNC1 | L29Q | 1.26 | Fibers X 2.3 μm | Li et al., 2013 |

| TNNC1 | L29Q | 1.17 | Fibers X 1.9 μm | Li et al., 2013 |

| TNNC1 | L29Q | 2.1 | IVMA | Schmidtmann et al., 2005 |

| TNNC1 | A31S | 1.48 | Fibers X | Parvatiyar et al., 2012 |

| TNNC1 | A31S | 2.75 | ATPase | Parvatiyar et al., 2012 |

| TNNC1 | D145E | 1.74 | Fibers X | Pinto et al., 2009 |

| TNNC1 | C84Y | 1.86 | Fibers X | Pinto et al., 2009 |

| TNNI3 | R21C | 2.16 | Fibers X | Gomes et al., 2005a |

| TNNI3 | L144Q | 2.04 | Fibers X | Gomes et al., 2005b |

| TNNI3 | R145G | 3.63 | ATPase | Elliott et al., 2000 |

| TNNI3 | R145G | 2.09 | ATPase | Takahashi-Yanaga et al., 2001 |

| TNNI3 | R145G | 1.82 | IVMA | Brunet et al., 2014 |

| TNNI3 | R145G | 1.41 | IVMA | Deng et al., 2001 |

| TNNI3 | R145G | 1.35 | Fibers X | Lang et al., 2002 |

| TNNI3 | R145G | 1.15 | Fibers TG | Krüger et al., 2005 |

| TNNI3 | R145Q | 1.41 | Fibers X | Takahashi-Yanaga et al., 2001 |

| TNNI3 | R145Q | 1.70 | ATPase | Takahashi-Yanaga et al., 2001 |

| TNNI3 | R145W | 2.45 | Fibers X | Gomes et al., 2005b |

| TNNI3 | R145W | 1.15 | Human fibers | Sequeira et al., 2013 |

| TNNI3 | R162W | 1.28 | ATPase | Takahashi-Yanaga et al., 2001 |

| TNNI3 | A171T | 1.38 | Fibers X | Gomes et al., 2005b |

| TNNI3 | K178E | 2.95 | Fibers X | Gomes et al., 2005b |

| TNNI3 | ΔK182 | 1.51 | ATPase | Takahashi-Yanaga et al., 2001 |

| TNNI3 | ΔK183 | 3.8 | IVMA | Köhler et al., 2003 |

| TNNI3 | R192H | 2.29 | Fibers X | Gomes et al., 2005b |

| TNNI3 | G203S | 3.02 | IVMA | Köhler et al., 2003 |

| HCM | ||||

| TNNI3 | K206Q | 2.51 | IVMA | Köhler et al., 2003 |

| TNNI3 | K206Q | 1.51 | ATPase | Takahashi-Yanaga et al., 2001 |

| TNNI3 | K206I | 1.81 | ATPase | Warren et al., 2015 |

| TNNT2 | TnTΔ14 | 2.51 | Fibers X | Gafurov et al., 2004 |

| TNNT2 | TnTdel | 2.69 | ATPase | Redwood et al., 2000 |

| TNNT2 | I79N | 1.41 | Fibers X | Szczesna et al., 2000 |

| TNNT2 | I79N | 2.04 | Fibers TG | Baudenbacher et al., 2008 |

| TNNT2 | R92L | 1.65 | Fibers TG | Ford et al., 2012 |

| TNNT2 | R92Q | 1.66 | Fibers TG | Ford et al., 2012 |

| TNNT2 | R92Q | 1.74 | ATPase | Robinson et al., 2002 |

| TNNT2 | R92Q | 1.94 | IVMA | Robinson et al., 2002 |

| TNNT2 | F110I | 2.34 | Fibers TG | Szczesna et al., 2000 |

| TNNT2 | F110I | 1.32 | Fibers TG | Baudenbacher et al., 2008 |

| TNNT2 | ΔE160 | 1.41 | Fibers TG | Lu et al., 2003 |

| TNNT2 | R278C | 2.19 | Fibers TG | Szczesna et al., 2000 |

| TNNT2 | K280N | 1.64 | IVMA | Messer et al., 2016b |

| TNNT2 | K280N | 1.26 | IVMA (human Tn) | Messer et al., 2016b |

| TPM1 | E62Q | 1.21 | ATPase | Chang et al., 2005 |

| TPM1 | A63V | 1.91 | Transfected cell | Michele et al., 1999 |

| TPM1 | A63V | 1.99 | ATPase | Heller et al., 2003 |

| TPM1 | K70T | 1.58 | Transfected cell | Michele et al., 1999 |

| TPM1 | K70T | 2.13 | ATPase | Heller et al., 2003 |

| TPM1 | D175N | 1.23 | IVMA | Bing et al., 2000 |

| TPM1 | E180G | 1.30 | IVMA | Bing et al., 2000 |

| TPM1 | E180G | 1.63 | IVMA | Papadaki et al., 2015 |

| TPM1 | E180G | 1.44 | Transfected cell | Michele et al., 1999 |

| TPM1 | E180G | 2.75 | ATPase | Chang et al., 2005 |

| TPM1 | L185R | 2.51 | ATPase | Chang et al., 2005 |

| TPM1 | I284V | 1.50 | Human fibers | Sequeira et al., 2013 |

The criteria for inclusion in the table are (1) that a missense mutation has been convincingly linked to the myopathy phenotype and (2) that only direct Ca2+-sensitivity comparisons of mutant and “normal” are included. Seventy-one independent measurements of the HCM mutation-induced change of EC50 shown as EC50 WT/mutant. Values range from 1.15 to 3.8-fold with a mean of 1.87 ± 0.07 (sem). Shading indicates gene studied.

Gene names: ACTC, cardiac alpha actin; TNNI3, cardiac troponin I; TNNT2, cardiac troponin T (T3 isoform); TNNC2 cardiac troponin C; MYL2, ventricular regulatory myosin light chain; MYH7, beta myosin heavy chain; MYBPC3, cardiac myosin binding protein C; TPM1, alpha tropomyosin, Tpm1.1.

Measurement methods: IVMA, in vitro motility assay; Fibers TG, skinned fibers from transgenic or knock-in mouse heart; Myofibrils TG, single myofibrils from transgenic or knock-in mouse heart; Fibers X, skinned fibers with mutation protein exchanged in Human fibers, skinned fibers from human heat muscle; ATPase, reconstituted thin filament activation of myosin ATPase activity.

Table 2.

Effect of skeletal muscle gain-of -function mutations on Ca2+-sensitivity shown as EC50 WT/mutant.

| Gene name | Mutation | wt/mutant EC50 ratio | Measured in | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTA1 | K326N | 2.50 | IVMA | Jain et al., 2012 |

| TPM2 | ΔK49 | 1.19 | IVMA | Marston et al., 2013 |

| TPM2 | ΔE139 | 1.51 | IVMA | Marston et al., 2013 |

| TPM2 | E181K | 1.58 | Human fibers | Ochala et al., 2012 |

| TPM2 | ΔK7 50% | 2.00 | IVMA | Mokbel et al., 2013 |

| TPM2 | ΔK7 | 2.70 | Human fibers | Mokbel et al., 2013 |

| TPM3 | K168E | 2.67 | IVMA | Marston et al., 2013 |

| TPM3 | K168E 50% | 1.85 | IVMA | Marston et al., 2013 |

| TPM3 | ΔE224 | 1.34 | Human fibers | Donkervoort et al., 2015 |

| TPM3 | ΔE224 | 2.2 | IVMA | Donkervoort et al., 2015 |

| TPM3 | Δ218 | 2.5 | IVMA | Donkervoort et al., 2015 |

The mean change is 1.65± 0.16-fold (range 1.19–2.70).

GENE NAMES: ACTA1, skeletal muscle alpha actin; TPM2, beta tropomyosin, Tpm2.2; TPM3, Tpm3.12, “gamma tropomyosin.”

Shading indicates gene studied.

Dilated cardiomyopathy-causing mutations were initially found to decrease Ca2+-sensitivity but more recent studies have indicated the situation is more complex. DCM-linked mutations can both increase and decrease Ca2+-sensitivity depending on the individual mutations, moreover the direction of change can be different with a single mutation measured in different systems (Marston, 2011; Memo et al., 2013). This is illustrated in Table 3 where 42 independent determinations show a range of EC50 wt/mutant from 0.3 to 2.3. In addition we found 14 measurements of Ca2+-sensitivity changes due skeletal muscle myopathy mutations ranging from 0.39 to 0.63 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Effect of dilated cardiomyopathy linked mutations on Ca2+-sensitivity.

| Gene name | Mutation | wt/mutant EC50 ratio | Measured in | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTC | E361G | 1.05 | IVMA | Song et al., 2010 |

| ACTC | E361G skTn | 0.30 | IVMA | Song et al., 2010 |

| TNNI3 | K36Q | 0.47 | IVMA | Memo et al., 2013 |

| TNNI3 | K36Q | 0.41 | ATPase | Carballo et al., 2009 |

| TNNI3 | N185K | 0.42 | ATPase | Carballo et al., 2009 |

| TNNT2 | R131W | 0.59 | ATPase | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | R131W | 0.63 | IVMA | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | R134G | 0.89 | Fibers X | Hershberger et al., 2009 |

| TNNT2 | R141W | 0.69 | IVMA | Memo et al., 2013 |

| TNNT2 | R141W | 0.80 | ATPase | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | R141W | 0.89 | Fibers X | Venkatraman et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | R151C | 0.81 | Fibers X | Hershberger et al., 2009 |

| TNNT2 | R159Q | 0.83 | Fibers X | Hershberger et al., 2009 |

| TNNT2 | R206L | 0.35 | IVMA | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | R205L | 0.34 | ATPase | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | R205L | 0.68 | Fibers X | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | R205W | 0.83 | Fibers X | Hershberger et al., 2009 |

| TNNT2 | ΔK210 hetero | 0.63 | IVMA | Du et al., 2007 |

| TNNT2 | ΔK210 | 0.75 | Fibers X | Venkatraman et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | ΔK210 | 0.45 | IVMA | Du et al., 2007 |

| TNNT2 | ΔK210 recombinant | 1.54 | ATPase | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | ΔK210 50% | 0.46 | IVMA | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | D270N | 0.65 | IVMA | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNT2 | D270N | 0.64 | ATPase | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNC1 | Y5H | 0.82 | Fibers X | Pinto et al., 2011 |

| TNNC1 | D73N | 0.55 | ATPase | McConnell et al., 2015 |

| TNNC1 | D73N | 0.59 | Fibers X | McConnell et al., 2015 |

| TNNC1 | D145E | 0.52 | Fibers X | Pinto et al., 2011 |

| TNNC1 | I148V | 0.91 | Fibers X | Pinto et al., 2011 |

| TNNC1 | G159D | 0.56 | ATPase | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNC1 | G159D | 0.55 | IVMA | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TNNC1 | G159D | 1.86 | IVMA | Dyer et al., 2009 |

| TNNC1 | G159D skTn | 0.56 | IVMA | Dyer et al., 2009 |

| TNNC1 | G159D | Fibers X | Biesiadecki et al., 2007 | |

| TPM1 | E40K | 0.69 | IVMA | Memo et al., 2013 |

| TPM1 | E40K baculovirus | 0.38 | IVMA | Memo et al., 2013 |

| TPM1 | E40K | 0.64 | ATPase | Chang et al., 2005 |

| TPM1 | E54K | 0.58 | ATPase | Mirza et al., 2005 |

| TPM1 | E54K | 1.90 | Ca binding | Robinson et al., 2007 |

| TPM1 | D230N baculovirus | 2.30 | IVMA | Memo et al., 2013 |

| TPM1 | D230N bacu+skTn | 0.59 | IVMA | Memo et al., 2013 |

| TPM1 | D230N Recombinant | 0.54 | ATPase | Lakdawala et al., 2010 |

Forty-two independent measurements of the mutation-induced change of EC50 shown as EC50 WT/mutant.

Shading indicates gene studied.

Table 4.

Skeletal myopathy mutations causing a loss of function.

| Gene name | Mutation | wt/mutant EC50 ratio | Measured in | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM2 | E117K | 0.41 | IVMA | Marttila et al., 2012 |

| TPM2 | Q147P | 0.63 | IVMA | Marttila et al., 2012 |

| TPM3 | L100M | 0.52 | IVMA | Marttila et al., 2012 |

| TPM3 | R167C | 0.36 | Myofibers | Ochala et al., 2012 |

| TPM3 | R167H | 0.59 | IVMA | Marston et al., 2013 |

| TPM3 | R167H 50% | 0.58 | IVMA | Marston et al., 2013 |

| TPM3 | R244G | 0.46 | IVMA | Marston et al., 2013 |

| TPM3 | R244G 50% | 0.60 | IVMA | Marston et al., 2013 |

| TPM3 | K169E | 0.55 | Myofibers | Yuen et al., 2015 |

| TPM3 | R245G | 0.45 | Myofibers | Yuen et al., 2015 |

| TPM3 | L100M | 0.53 | Myofibers | Yuen et al., 2015 |

| TPM3 | R168G | 0.48 | Myofibers | Yuen et al., 2015 |

| TPM3 | R168H | 0.42 | Myofibers | Yuen et al., 2015 |

| TPM3 | R167C | 0.39 | Myofibers | Yuen et al., 2015 |

Fourteen independent measurements of the mutation-induced change of EC50 shown as EC50 WT/mutant. The mean change is 0.49 ± 0.02-fold (range 0.36–0.63).

Shading indicates gene studied.

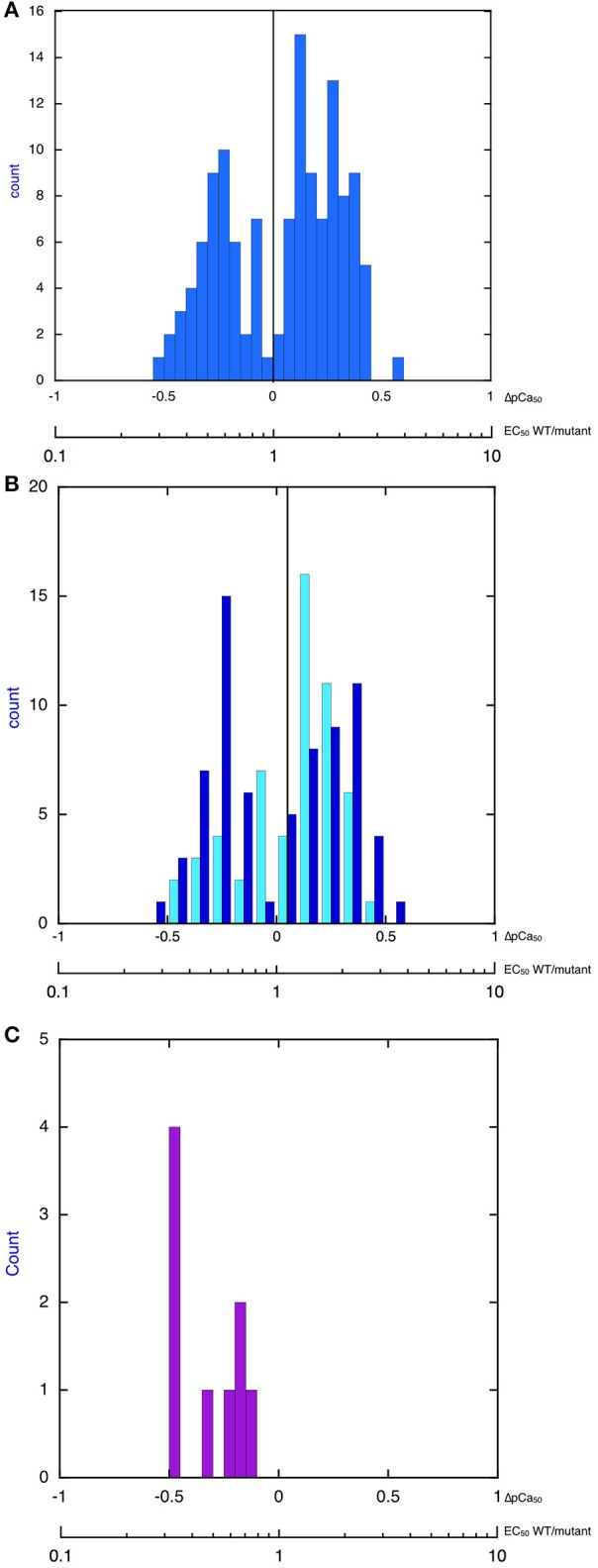

Thus, our extensive literature search, although not necessarily complete, found that, indeed, the changes in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity due to disease-causing mutations have a bimodal distribution and that the overall changes in Ca2+-sensitivity are quite small and do not extend beyond a 3–4-fold increase or decrease in Ca2+-sensitivity. Indeed when all the findings are plotted as a histogram one finds that increases in Ca2+-sensitivity on a log scale have an approximately normal distribution with mean increase in Ca2+-sensitivity (EC50 wt/mutant) of 1.86-fold (corresponding to ΔpCa50 = 0.255 ± 0.015), whilst the decreases in Ca2+ sensitivity have a mean EC50 wt/mutant of 0.54-fold (corresponding to ΔpCa50 of –0.286 ± 0.01; Figure 1A). It is also worth noting that this small Ca2+-sensitivity shift is observed independent of the measurement method Figure 1B compares the ΔpCa50 distribution measured by unloaded assays (actomyosin ATPase or in vitro motility) and by loaded assays (force measurements in skinned muscles, cell, and isolated myofibrils). The mean magnitude of the Ca2+-sensitivity change is about 20% less when measured in loaded assays.

Figure 1.

Histograms showing distribution of the change in Ca2+-sensitivity due to mutations and phosphorylation. The X-axis is pCa50(mutant-WT, ΔpCa50) or EC50 (WT/mutant), log scale. (A) All 149 values from Tables 1–4 are plotted. The plot is bimodal. Mean of decreased Ca2+-sensitivity (ΔpCa50 < 0) = –0.286 ± 0.016, Mean of increased Ca2+ sensitivity (ΔpCa50 > 0) = 0.255 ± 0.015. (B) Distribution of change in Ca2+-sensitivity is compared for loaded (pale blue) and unloaded (dark blue) assays of cardiac muscle regulation (data from Tables 1, 3). Unloaded assays are IVMA and ATPase, loaded assays are Fibers TG, Myofibrils TG, Fibers X, Human fibers, For decreased Ca2+ sensitivity mean unloaded ΔpCa50 is –0.27 ± 0.02 and mean loaded is –0.21 ± 0.03, p = 0.05. For increased Ca2+-sensitivity mean unloaded ΔpCa50 is 0.26 ± 0.02 and mean loaded is 0.021 ± 0.02, p = 0.04. (C) Distribution of change in Ca2+-sensitivity due to troponin I phosphorylation (EC50 unphosphorylated/EC50 phosphorylated). Data from Table 5. The mean change is 0.50 ± 0.06-fold (n = 9), ΔpCa50 = −0.30.

What could be the underlying reason for this consistent and small effect of mutations on EC50? We will consider two possible mechanisms that are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Firstly, it could be that the limit is set by the capacity of the EC coupling system that supplies activating Ca2+ and that striated muscle cannot work in a way compatible with life outside these limits; alternatively it may be due to a fundamental property of the troponin system and the permitted conformational transitions compatible with efficient regulation.

Before attempting to discuss these mechanisms it is worthwhile considering some additional evidence on Ca2+-sensitivity shifts. Perhaps the most puzzling observation is that there appears to be no correlation between the Ca2+-sensitivity shift and disease severity. Skeletal myopathy mutations that cause life-threating muscle weakness from birth and often require mechanical assistance in breathing (Ravenscroft et al., 2015), have the same Ca2+-sensitivity shifts as dilated cardiomyopathy mutations which are considerably less lethal (Hershberger et al., 2013). Whilst heart muscle has compensatory strategies not available in skeletal muscle to account for this difference, the small change in Ca2+-sensitivity even in the most severe skeletal muscle disease might be indicative of a fundamental structure-based limit on changes in EC50.

Consideration of the Ca2+-sensitivity shifts in cardiomyopathies (Tables 1, 3) do not indicate any correlation with disease severity. Any relationship that may exist is masked by the extreme variability of Ca2+-sensitivity shift measurements. For instance, the “severe” TNNI3 R145G HCM/RCM-linked mutation features at both extremes of the Ca2+-sensitivity range (1.15x and 3.65x); for the 6 assays in the table the mean is 1.84, close to the mean of all 71 HCM measurements (1.87). The same variability can be seen with other mutations where multiple values are available: ACTC E99K, n = 5, 1.24–2.45 mean 1.85; TPM1 E180G, n = 4, 1.30–2.75, mean 1.78. The second relevant observation is that the physiological modulation of cardiac muscle myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity due to phosphorylation of troponin I by protein kinase A has been known to be a 2–3-fold shift for many years (Solaro et al., 2008). Table 5 lists a number of recent determinations of this Ca2+-sensitivity shift in several species and measured by both loaded and unloaded assays illustrating its small range. Figure 1C shows how the magnitude and distribution of measured changes is similar to the changes induced by disease-causing mutations. It would be logical to conclude that this represents the range of achievable Ca2+ sensitivity shifts in cardiac muscle due to the limitations of the EC coupling system.

Table 5.

Ca2+ sensitivity change due to troponin I phosphorylation 8 independent measurements of the phosphorylation-induced change of EC50 shown as ratio of EC50 unphosphorylated/phosphorylated (uP/P).

| EC50 | wt/mutant EC50 ratio | Measured in | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human failing/donor | 0.57 | IVMA | Messer, 2007; Messer et al., 2007 |

| Human failing/donor | 0.68 | Human fibers | van der Velden et al., 2003 |

| Donor uP/P | 0.34 | IVMA | Song et al., 2011 |

| Donor uP/P | 0.32 | IVMA | Bayliss et al., 2012 |

| Donor uP/P | 0.34 | IVMA | Memo et al., 2013 |

| Mouse uP/P | 0.33 | IVMA | Song et al., 2010 |

| Mouse uP/P | 0.50 | IVMA | Memo et al., 2013 |

| Mouse uP/P | 0.74 | Myofibrils | Vikhorev et al., 2014 |

| WT cTnI/cTnI-DD | 0.69 | Fibers X | Biesiadecki et al., 2007 |

Measurements were made with troponin (IVMA) or skinned muscle from human (donor) or mouse heart. The mean change is 0.50 ± 0.06-fold (range 0.32–0.74).

In principle, it should be possible to go beyond the Ca2+-sensitivity limits set by EC coupling in an in vitro system where Ca2+ binding affinity can be much greater or much less than the native troponin. Cardiac troponin C presents extreme examples in a single molecule. Only site II binds Ca2+ in the physiologically relevant range (2.5 × 105 M−1) and so is solely responsible for Ca2+-regulation (Holroyde et al., 1980). A few amino acid changes in the EF-hand motifs results in sites that do not bind Ca2+ (Site I) or sites that bind Ca2+ 200x tighter (sites III and IV) and are permanently occupied by Ca2+ or Mg2+ (Li and Hwang, 2015). Thus, it would seem that neither a very high Ca2+ sensitivity nor a very low one are able to participate in regulation. How much deviation of Ca2+ affinity from the norm is compatible with muscle regulation?

It is known that for mutations, the small Ca2+-sensitivity changes correlate with Ca2+ binding affinity to thin filaments (Robinson et al., 2007). In a study of mutations induced in skeletal muscle troponin C, Davis et al. achieved a 243-fold range of Ca2+ binding affinities for troponin C. However, this did not translate into such a great range when Ca2+-binding was measured in the presence of TnI (96-148) and caused a still smaller shift in the Ca2+-sensitivity of force production (Davis et al., 2004). Thus, the most extreme Ca2+-sensitizing mutation, V45Q increased TnC Ca2+ binding affinity 19-fold, but the increase was only 3.1-fold when measured in the presence of the TnI peptide and Ca2+-sensitivity in skinned fibers was just 2.3-fold more than wild-type. This is within the same range of many HCM-causing mutations (Table 1). A similar picture emerges from Cardiac troponin C where the single regulatory Ca2+-binding site simplifies the argument: V44Q increases Ca2+-binding affinity to TnC 6.5-fold but increases myocyte Ca2+-sensitivity by just 3.4-fold (Parvatiyar et al., 2010). Thus, it seems that the structure of troponin and its interactions with the rest of the thin filament does limit the consequences of a modification that increases Ca2+ binding affinity.

A slightly different situation arises when Ca2+ binding affinity is less than wild-type. Davis et al., noted that the mutations that decreased Ca2+ binding affinity the most (F26Q, 63-fold, I37Q, 24-fold and I62Q, 10-fold) could not properly regulate force in skinned fibers since they only produced about 13% of the maximal force of wild-type muscle at saturating Ca2+ concentrations. On the other hand, two less extreme mutations, M81Q and F78Q decreased Ca2+-sensitivity whilst retaining the same maximum force production as wild type. In these cases, again, the increased Ca2+ binding affinity for TnC was substantially greater than the increased Ca2+-sensitivity of skinned fibers (5.9x vs. 1.8x for M81Q and 8.4x vs. 4.2x for F78Q). Thus, thin filament structure seems to limit the possible effects of changes in Ca2+-binding affinity.

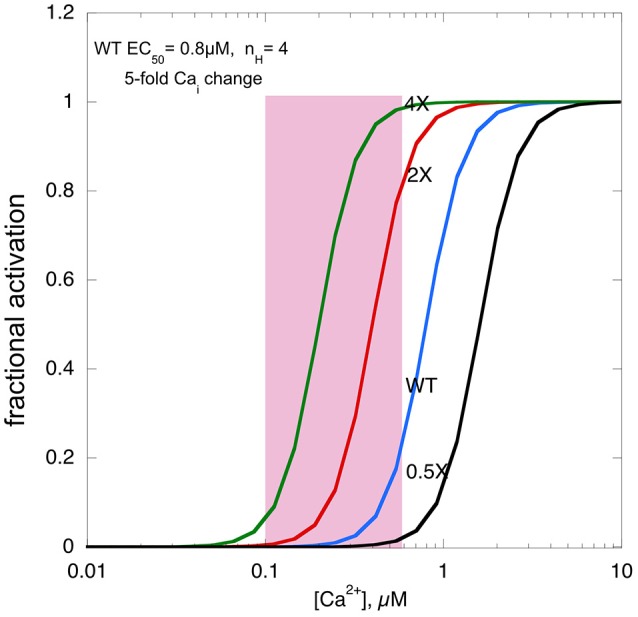

It is self-evident that changing myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity will affect contractile output in muscle. It is well-established that EC50 for skinned muscle fibers is about 1 μM and that Ca2+-activation of contraction is highly cooperative. Most measurements suggest a five-fold range in free Ca2+ concentration during a cardiac muscle contraction. Peak Ca2+ concentration is about 600 nM at rest and can be substantially higher during adrenergic stimulation, thus normally muscle is only partially activated (Negretti et al., 1995; Dibb et al., 2007).

Figure 2 shows a real life example: in a mouse model of HCM (ACTC E99K) we measured both the Ca2+-activation curve for myofibrils and the contractility of intact papillary muscle as well as the Ca2+-transient (Song et al., 2013). Under the conditions of this experiment the Ca2+ transient was the same in Wild-type and ACTC E99K muscle, Ca2+ sensitivity was 0.8 μM for wild-type and 0.34 μM for ACTC E99K with a Hill coefficient of about 4. The increase in Ca2+-sensitivity due to the ACTC E99K HCM mutation corresponds to an approximately four-fold increase in twitch force in the absence of a change in the Ca2+-transient that was actually observed.

Figure 2.

The effects of changing Ca2+-sensitivity on contractility. Ca2+-activation curves for mouse myofibrils with EC50 of 0.8 μM, a Hill coefficient of 4 and a [Ca2+]i range from 500 nM at peak to 100 nM when relaxed (pink box). The curves with two-fold higher Ca2+ sensitivity, as found with HCM mutations, four-fold higher Ca2+ sensitivity and 0.5-fold Ca2+-sensitivity, as may be found in some DCM mutations, is plotted for comparison.

We can use this model to consider what would happen if Ca2+-sensitivity changed beyond the normal range. If myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity was 4 times normal, maximum force would reach close to 100%, leaving no range for it to be modulated by adrenergic agents. Moreover, it is likely that the muscle would not fully relax, since, based on the five-fold range of the Ca2+ transient even at the lowest Ca2+ level force would be 5–10%, a substantial fraction of the peak force of wild-type muscle, thus the hypercontractile phenotype would impose a major defect in relaxation, much more severe than the diastolic dysfunction associated with HCM mutations with only a 1.8-fold average Ca2+ sensitivity increase.

If myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity were decreased to half the normal, contractility would be very low indeed. The fact that mutations that decrease Ca2+-sensitivity are not lethal and indeed in transgenic mice, may exhibit little phenotype, is probably due to a compensatory increase in the Ca2+-transient (Du et al., 2007). However, this compensation may not be enough to support normal contraction in the long term, leading to DCM, the phenotype commonly associated with reduced Ca2+-sensitivity.

Conclusion

The objective of this article was to confirm that Ca2+-sensitivity of contractility only varies within an narrow range of three-fold above and below the normal EC50 at rest and to investigate why this should be. The high cooperativity of muscle activation by Ca2+ means there is a narrow [Ca2+] range between relaxed and active muscle. It would appear that the excitation-contraction coupling machinery of the cell has limited ability to change the amplitude of the Ca2+-transient or baseline [Ca2+] to compensate for changes in EC50; thus increased Ca2+-sensitivity would be limited by inability to relax and reduced Ca2+-sensitivity would be limited by inability to contract. It is intriguing that the Ca2+-sensitivity range of the thin filament itself is independently limited. Mutations that change Ca2+-binding affinity to TnC by a large amount nevertheless only produce a small change in EC50 for activation of loaded or unloaded contractility in vitro. Whether this property is an evolutionary adaptation that limits the deleterious effects of mutations in thin filaments or simply fortuitous in unknown.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Funding

SM's research is funded by British Heart Foundation programme grant RG/11/20/29266.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HCM

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- RCM

Restrictive cardiomyopathy

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- EC50

Ca2+ concentration that gives 50% maximal activation

- pCa50

–log EC50.

References

- Baudenbacher F., Schober T., Pinto J. R., Sidorov V. Y., Hilliard F., Solaro R. J., et al. (2008). Myofilament Ca2+ sensitization causes susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmia in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3893–3903. 10.1172/jci36642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss C. R., Jacques A. M., Leung M.-C., Ward D. G., Redwood C. S., Gallon C. E., et al. (2012). Myofibrillar Ca2+-sensitivity is uncoupled from troponin I phosphorylation in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy due to abnormal troponin T. Cardiovasc. Res. 97, 500–508. 10.1093/cvr/cvs322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesiadecki B. J., Kobayashi T., Walker J. S., John Solaro R., de Tombe P. P. (2007). The troponin C G159D mutation blunts myofilament desensitization induced by troponin I Ser23/24 phosphorylation. Circ. Res. 100, 1486–1493. 10.1161/01.RES.0000267744.92677.7f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing W., Knott A., Redwood C. S., Esposito G., Purcell I., Watkins S., et al. (2000). Effect of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in human cardiac a-tropomyosin (Asp175Asn and Glu180Gly) on the regulatory properties of human cardiac troponin determined by in vitro motility assay. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 32, 1489–1498. 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard E., Seidman C., Seidman J. G., LeWinter M., Maughan D. (1999). Altered crossbridge kinetics in the alphaMHC403/+ mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 84, 475–483. 10.1161/01.RES.84.4.475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet N. M., Chase P. B., Mihajlovic G., Schoffstall B. (2014). Ca2+-regulatory function of the inhibitory peptide region of cardiac troponin I is aided by the C-terminus of cardiac troponin T: effects of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations cTnI R145G and cTnT R278C, alone and in combination, on filament sliding. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 552, 11–20. 10.1016/j.abb.2013.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo S., Robinson P., Otway R., Fatkin D., Jongbloed J. D., de Jonge N., et al. (2009). Identification and functional characterization of cardiac troponin I as a novel disease gene in autosomal dominant dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 105, 375–382. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.196055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A. N., Harada K., Ackerman M. J., Potter J. D. (2005). Functional consequences of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy-causing mutations in alpha-tropomyosin. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34343–34349. 10.1074/jbc.M505014200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. P., Rall J. A., Alionte C., Tikunova S. B. (2004). Mutations of hydrophobic residues in the N-terminal domain of troponin C affect calcium binding and exchange with the troponin C-troponin I96-148 complex and muscle force production. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 17348–17360. 10.1074/jbc.M314095200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Schmidtmann A., Redlich A., Westerdorf B., Jaquet K., Thieleczek R. (2001). Effects of phosphorylation and mutation R145G on human cardiac troponin I function. Biochemistry 40, 14593–14602. 10.1021/bi0115232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibb K. M., Eisner D. A., Trafford A. W. (2007). Regulation of systolic [Ca2+]i and cellular Ca2+ flux balance in rat ventricular myocytes by SR Ca2+, L-type Ca2+ current and diastolic [Ca2+]i. J. Physiol. 585, 579–592. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.141473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkervoort S., Papadaki M., de Winter J. M., Neu M. B., Kirschner J., Bolduc V., et al. (2015). TPM3 deletions cause a hypercontractile congenital muscle stiffness phenotype. Ann. Neurol. 78, 982–994. 10.1002/ana.24535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du C. K., Morimoto S., Nishii K., Minakami R., Ohta M., Tadano N., et al. (2007). Knock-in mouse model of dilated cardiomyopathy caused by troponin mutation. Circ. Res. 101, 185–194. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.146670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer E. C., Jacques A. M., Hoskins A. C., Ward D. G., Gallon C. E., Messer A. E., et al. (2009). Functional analysis of a unique troponin C mutation, Gly159Asp that causes familial dilated cardiomyopathy, studied in explanted heart muscle. Circ. Heart Fail. 2, 456–464. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.818237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott K., Watkins H., Redwood C. S. (2000). Altered regulatory properties of human cardiac troponin I mutants that cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22069–22074. 10.1074/jbc.M002502200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford S. J., Mamidi R., Jimenez J., Tardiff J. C., Chandra M. (2012). Effects of R92 mutations in mouse cardiac troponin T are influenced by changes in myosin heavy chain isoform. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 53, 542–551. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraysse B., Weinberger F., Bardswell S. C., Cuello F., Vignier N., Geertz B., et al. (2012). Increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and diastolic dysfunction as early consequences of Mybpc3 mutation in heterozygous knock-in mice. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 52, 1299–1307. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafurov B., Fredricksen S., Cai A., Brenner B., Chase P. B., Chalovich J. M. (2004). The Delta 14 mutation of human cardiac troponin T enhances ATPase activity and alters the cooperative binding of S1-ADP to regulated actin. Biochemistry 43, 15276–15285. 10.1021/bi048646h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A. V., Harada K., Potter J. D. (2005a). A mutation in the N-terminus of troponin I that is associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy affects the Ca(2+)-sensitivity, phosphorylation kinetics and proteolytic susceptibility of troponin. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 39, 754–765. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A. V., Liang J., Potter J. D. (2005b). Mutations in human cardiac troponin I that are associated with restrictive cardiomyopathy affect basal ATPase activity and the calcium sensitivity of force development. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30909–30915. 10.1074/jbc.M500287200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller M. J., Nili M., Homsher E., Tobacman L. S. (2003). Cardiomyopathic tropomyosin mutations that increase thin filament Ca2+ sensitivity and tropomyosin N-domain flexibility. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41742–41748. 10.1074/jbc.M303408200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger R. E., Hedges D. J., Morales A. (2013). Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 10, 531–547. 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger R. E., Pinto J. R., Parks S. B., Kushner J. D., Li D., Ludwigsen S., et al. (2009). Clinical and functional characterization of TNNT2 mutations identified in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2, 306–313. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.846733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyde M. J., Robertson S. P., Johnson J. D., Solaro R. J., Potter J. D. (1980). The calcium and magnesium binding sites on cardiac troponin and their role in the regulation of myofibrillar adenosine triphosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 11688–11693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R. K., Jayawant S., Squier W., Muntoni F., Sewry C. A., Manzur A., et al. (2012). Nemaline myopathy with stiffness and hypertonia associated with an ACTA1 mutation. Neurology 78, 1100–1103. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8ebe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrick W. G., Kazmierczak K., Xu Y., Wang Y., Szczesna-Cordary D. (2009). Malignant familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy D166V mutation in the ventricular myosin regulatory light chain causes profound effects in skinned and intact papillary muscle fibers from transgenic mice. FASEB J. 23, 855–865. 10.1096/fj.08-118182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler J., Chen Y., Brenner B., Gordon A. M., Kraft T., Martyn D. A., et al. (2003). Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in troponin I (K183D, G203S, K206Q) enhance filament sliding. Physiol. Genomics 14, 117–128. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00101.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger M., Zittrich S., Redwood C., Blaudeck N., James J., Robbins J., et al. (2005). Effects of the mutation R145G in human cardiac troponin I on the kinetics of the contraction–relaxation cycle in isolated cardiac myofibrils. J. Physiol. 564, 347–357. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakdawala N. K., Dellefave L., Redwood C. S., Sparks E., Cirino A. L., Depalma S., et al. (2010). Familial dilated cardiomyopathy caused by an alpha-tropomyosin mutation: the distinctive natural history of sarcomeric dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 320–329. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R., Gomes A. V., Zhao J., Housmans P. R., Miller T., Potter J. D. (2002). Functional analysis of a troponin I (R145G) mutation associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11670–11678. 10.1074/jbc.M108912200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A. Y., Stevens C. M., Liang B., Rayani K., Little S., Davis J., et al. (2013). Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy related cardiac troponin C L29Q mutation alters length-dependent activation and functional effects of phosphomimetic troponin I*. PLoS ONE 8:e79363. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. X., Hwang P. M. (2015). Structure and function of cardiac troponin C (TNNC1): implications for heart failure, cardiomyopathies, and troponin modulating drugs. Gene 571, 153–166. 10.1016/j.gene.2015.07.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q. W., Morimoto S., Harada K., Du C. K., Takahashi-Yanaga F., Miwa Y., et al. (2003). Cardiac troponin T mutation R141W found in dilated cardiomyopathy stabilizes the troponin T-tropomyosin interaction and causes a Ca(2+) desensitization. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 35, 1421–1427. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston S. B. (2011). How do mutations in contractile proteins cause the primary familial cardiomyopathies? J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 4, 245–255. 10.1007/s12265-011-9266-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston S., Memo M., Messer A., Papadaki M., Nowak K., McNamara E., et al. (2013). Mutations in repeating structural motifs of tropomyosin cause gain of function in skeletal muscle myopathy patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 4978–4987. 10.1093/hmg/ddt345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins A. S., Parvatiyar M. S., Feng H.-Z., Bos J. M., Gonzalez-Martinez D., Vukmirovic M., et al. (2015). In vivo analysis of troponin C knock-in (A8V) mice: evidence that TNNC1 is a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy susceptibility gene. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 8, 653–664. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marttila M., Lehtokari V.-L., Marston S., Nyman T. A., Barnerias C., Beggs A. H., et al. (2014). Mutation update and genotype-phenotype correlations of novel and previously described mutations in TPM2 and TPM3 causing congenital myopathies. Hum. Mutat. 35, 779–790. 10.1002/humu.22554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marttila M., Lemola E., Wallefeld W., Memo M., Donner K., Laing N. G., et al. (2012). Abnormal actin binding of aberrant β-tropomyosins is a molecular cause of muscle weakness in TPM2-related nemaline and cap myopathy. Biochem. J. 442, 231–239. 10.1042/BJ20111030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell B. K., Singh S., Fan Q., Hernandez A., Portillo J. P., Reiser P. J., et al. (2015). Knock-in mice harboring a Ca2+ desensitizing mutation in cardiac troponin C develop early onset dilated cardiomyopathy. Front. Physiol. 6:242. 10.3389/fphys.2015.00242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memo M., Leung M.-C., Ward D. G., dos Remedios C., Morimoto S., Zhang L., et al. (2013). Mutations in thin filament proteins that cause familial dilated cardiomyopathy uncouple troponin I Phosphorylation from changes in myofibrillar Ca2+-sensitivity. Cardiovasc. Res. 99, 65–73. 10.1093/cvr/cvt071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer A. (2007). Structural and Functional Polymorphisms of Troponin in Failing Heart. Ph.D., Thesis NHLI London, London. 343. [Google Scholar]

- Messer A., Bayliss C., El-Mezgueldi M., Redwood C., Ward D. G., Leung M.-C, et al. (2016b). Mutations in troponin T associated with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy increase Ca2+-sensitivity and suppress the modulation of Ca2+-sensitivity by troponin I phosphorylation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 601, 113–120. 10.1016/j.abb.2016.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer A. E., Jacques A. M., Marston S. B. (2007). Troponin phosphorylation and regulatory function in human heart muscle: dephosphorylation of Ser23/24 on troponin I could account for the contractile defect in end-stage heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 42, 247–259. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer A. E., Papadaki M., Vikhorev P. G., Sebzali Y., El-Mezgueldi M., Daley A., et al. (2016a). *Primary effects of HCM mutations in humans and cats. Biophys. J. 110, 123a–124a. 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.11.713 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michele D. E., Albayya F. P., Metzger J. M. (1999). Direct, convergent hypersensitivity of calcium-activated force generation produced by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutant alpha-tropomyosins in adult cardiac myocytes. Nat. Med. 5, 1413–1417. 10.1038/70990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza M., Marston S., Willott R., Ashley C., Mogensen J., McKenna W., et al. (2005). Dilated cardiomyopathy mutations in three thin filament regulatory proteins result in a common functional phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28498–28506. 10.1074/jbc.M412281200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokbel N., Ilkovski B., Kreissl M., Memo M., Jeffries C. M., Marttila M., et al. (2013). K7del is a common TPM2 gene mutation associated with nemaline myopathy and raised myofibre calcium sensitivity. Brain 136, 494–507. 10.1093/brain/aws348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negretti N., Varro A., Eisner D. A. (1995). Estimate of net calcium fluxes and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content during systole in rat ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 486(Pt 3), 581–591. 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochala J., Gokhin D. S., Pénisson-Besnier I., Quijano-Roy S., Monnier N., Lunardi J., et al. (2012). Congenital myopathy-causing tropomyosin mutations induce thin filament dysfunction via distinct physiological mechanisms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 4473–4485. 10.1093/hmg/dds289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer B. M., Fishbaugher D. E., Schmitt J. P., Wang Y., Alpert N. R., Seidman C. E., et al. (2004). Differential cross-bridge kinetics of FHC myosin mutations R403Q and R453C in heterozygous mouse myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H91–H99. 10.1152/ajpheart.01015.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki M., Vikhorev P. G., Marston S. B., Messer A. E. (2015). Uncoupling of myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity from troponin I phosphorylation by mutations can be reversed by epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Cardiovasc. Res. 108, 99–110. 10.1093/cvr/cvv181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvatiyar M. S., Landstrom A. P., Figueiredo-Freitas C., Potter J. D., Ackerman M. J., Pinto J. R., et al. (2012). A mutation in TNNC1-encoded cardiac troponin C, TNNC1-A31S, predisposes to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and ventricular fibrillation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 31845–31855. 10.1074/jbc.M112.377713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvatiyar M. S., Pinto J. R., Liang J., Potter J. D. (2010). Predicting cardiomyopathic phenotypes by altering Ca2+ affinity of cardiac troponin C. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27785–27797. 10.1074/jbc.M110.112326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto J. R., Parvatiyar M. S., Jones M. A., Liang J., Ackerman M. J., Potter J. D. (2009). A functional and structural study of troponin C mutations related to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19090–19100. 10.1074/jbc.M109.007021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto J. R., Siegfried J. D., Parvatiyar M. S., Li D., Norton N., Jones M. A., et al. (2011). Functional characterization of TNNC1 rare variants identified in dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 34404–34412. 10.1074/jbc.M111.267211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft G., Laing N. G., Bönnemann C. G. (2015). Pathophysiological concepts in the congenital myopathies: blurring the boundaries, sharpening the focus. Brain 138(Pt 2), 246–268. 10.1093/brain/awu368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redwood C., Lohmann K., Bing W., Esoposito G., Elliott K., Abdulrazzak H., et al. (2000). Investigation of a truncated troponin T that causes familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Ca2+ regulatory properties of reconstituted thin filaments depend on the ratio of mutant to wild-type peptide. Circ. Res. 86, 1146–1152. 10.1161/01.RES.86.11.1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson P., Griffiths P. J., Watkins H., Redwood C. S. (2007). Dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in troponin and alpha-tropomyosin have opposing effects on the calcium affinity of cardiac thin filaments. Circ. Res. 101, 1266–1273. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson P., Mirza M., Knott A., Abdulrazzak H., Willott R., Marston S., et al. (2002). Alterations in thin filament regulation induced by a human cardiac troponin T mutant that causes dilated cardiomyopathy are distinct from those induced by troponin T mutants that cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40710–40716. 10.1074/jbc.M203446200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtmann A., Lindow C., Villard S., Heuser A., Mügge A., Gessner R., et al. (2005). Cardiac troponin C-L29Q, related to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, hinders the transduction of the protein kinase A dependent phosphorylation signal from cardiac troponin I to C. FEBS J. 272, 6087–6097. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira V., Wijnker P. J., Nijenkamp L. L., Kuster D. W., Najafi A., Witjas-Paalberends E. R., et al. (2013). Perturbed length-dependent activation in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with missense sarcomeric gene mutations. Circ. Res. 112, 1491–1505. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaro R. J., Rosevear P., Kobayashi T. (2008). The unique functions of cardiac troponin I in the control of cardiac muscle contraction and relaxation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 369, 82–87. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Dyer E., Stuckey D., Copeland O., Leung M., Bayliss C., et al. (2011). Molecular mechanism of the Glu99lys mutation in cardiac actin (ACTC gene) that causes apical hypertrophy in man and mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27582–27593. 10.1074/jbc.M111.252320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Dyer E., Stuckey D., Leung M.-C., Memo M., Mansfield C., et al. (2010). Investigation of a transgenic mouse model of familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 49, 380–389. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Vikhorev P. G., Kashyap M. N., Rowlands C., Ferenczi M. A., Woledge R. C., et al. (2013). Mechanical and energetic properties of papillary muscle from ACTC E99K transgenic mouse models of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Pysiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 304, H1513–H1524. 10.1152/ajpheart.00951.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczesna D., Zhang R., Zhao J., Jones M., Guzman G., Potter J. D. (2000). Altered regulation of cardiac muscle contraction by troponin T mutations that cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 624–630. 10.1074/jbc.275.1.624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczesna-Cordary D., Guzman G., Ng S. S., Zhao J. (2004). Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-linked alterations in Ca2+ binding of human cardiac myosin regulatory light chain affect cardiac muscle contraction. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3535–3542. 10.1074/jbc.M307092200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi-Yanaga F., Morimoto S., Harada K., Minakami R., Shiraishi F., Ohta M., et al. (2001). Functional consequences of the mutations in human cardiac troponin I gene found in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 33, 2095–2107. 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Velden J., Papp Z., Zaremba R., Boontje N. M., de Jong J. W., Owen V. J., et al. (2003). Increased Ca2+-sensitivity of the contractile apparatus in end-stage human heart failure results from altered phosphorylation of contractile proteins. Cardiovasc. Res. 57, 37–47. 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00606-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman G., Gomes A. V., Kerrick W. G., Potter J. D. (2005). Characterization of troponin T dilated cardiomyopathy mutations in the fetal troponin isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17584–17592. 10.1074/jbc.M409337200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikhorev P. G., Song W., Wilkinson R., Copeland O., Messer A. E., Ferenczi M. A., et al. (2014). The dilated cardiomyopathy-causing mutation ACTC E361G in cardiac muscle myofibrils specifically abolishes modulation of Ca(2+) regulation by phosphorylation of troponin I. Biophys. J. 107, 2369–2380. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren C. M., Karam C. N., Wolska B. M., Kobayashi T., de Tombe P. P., Arteaga G. M., et al. (2015). A green tea catechin normalizes the enhanced Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments regulated by a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated mutation in human cardiac troponin I (K206I). Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 8, 765–773. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan C.-C., Muthu P., Kazmierczak K., Liang J., Huang W., Irving T. C., et al. (2015). Constitutive phosphorylation of cardiac myosin regulatory light chain prevents development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E4138–E4146. 10.1073/pnas.1505819112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen M., Cooper S. T., Marston S. B., Nowak K. J., McNamara E., Mokbel N., et al. (2015). Muscle weakness in TPM3-myopathy is due to reduced Ca2+-sensitivity and impaired acto-myosin cross-bridge cycling in slow fibres. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 6278–6292. 10.1093/hmg/ddv334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]