This study has the largest sample size of over 12 000, and is also the most comprehensive assessment of the literature to date regarding prognostic role of tumor PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer (CRC). We find that in patients with CRC, PIK3CA mutation may not add prognostic information regarding overall survival or progression-free survival.

Keywords: PIK3CA, mutation, colorectal cancer, prognosis

Abstract

Background

Somatic mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase/AKT pathway play a vital role in carcinogenesis. Approximately 15%–20% of colorectal cancers (CRCs) harbor activating mutations in PIK3CA, making it one of the most frequently mutated genes in CRC. We thus carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the prognostic significance of PIK3CA mutations in CRC.

Materials and methods

Electronic databases were searched from inception through May 2015. We extracted the study characteristics and prognostic data of each eligible study. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were derived and pooled using the random-effects Mantel–Haenszel model.

Results

Twenty-eight studies enrolling 12 747 patients were eligible for inclusion. Data on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were available from 19 and 10 studies, respectively. Comparing PIK3CA-mutated CRC patients with PIK3CA-wild-type CRC patients, the summary HRs for OS and PFS were 0.96 (95% CI 0.83–1.12) and 1.20 (95% CI 0.98–1.46), respectively. The trim-and-fill, Copas model and subgroup analyses stratified by the study characteristics confirmed the robustness of the results. Five studies reported the CRC prognosis for PIK3CA mutations in exons 9 and 20 separately; neither exon 9 mutation nor exon 20 mutation in PIK3CA was significantly associated with patient survival.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that PIK3CA mutation has the neutral prognostic effects on CRC OS and PFS. Evidence was accumulating for the establishment of CRC survival between PIK3CA mutations and patient-specific clinical or molecular profiles.

introduction

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K) is one of the crucial kinases in the PI3K/AKT1/MTOR pathway, playing a role in the cellular growth, proliferation and survival of multiple solid tumors [1–3]. Approximately 15%–20% of colorectal cancers (CRCs) harbor activating mutations in PIK3CA exon 9 and/or exon 20, making PIK3CA one of the most frequently mutated genes in CRC [4–7].

A number of studies have examined a prognostic role of somatic PIK3CA mutations in CRC [8–35]. Although some studies have reported the prognostic effect of the PIK3CA mutation status on CRC patient survival [4, 33, 36–40], several other studies of patients in various settings have reported varying results on the association of PIK3CA mutation with CRC survival outcomes [8, 9, 11–14]. It has been found in several studies that PIK3CA mutations showed significant positive association with CRC survival [8, 38, 39], while still others reported negative [9–11, 13, 14, 20, 35] or null association [12, 21, 24, 30]. Therefore, the prognostic role of PIK3CA mutations in CRC remains uncertain.

We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the evidence for the association between PIK3CA mutation and CRC patient recurrence and survival outcomes. In our secondary analysis considering the studies [38, 39] which have reported survival benefit associated with aspirin use in PIK3CA-mutated CRC (but not in PIK3CA-wild-type CRC), we meta-analyzed the prognostic associations of aspirin use after CRC diagnosis in strata of tumor PIK3CA mutation status.

materials and methods

search strategy

A computerized literature search of PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library Central Register of Controlled Trials and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) databases through May 2015 was conducted for all peer-reviewed studies that reported an association between CRC survival outcomes and PIK3CA mutations. As is presented in supplementary Appendix Table SA1–4, available at Annals of Oncology online, the following combinations of free-text words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)/EMTREE terms were used: ‘PIK3CA or Phosphoinositide-3-kinase catalytic alpha polypeptide or PIK3 catalytic alpha polypeptide’, ‘mutation* or mutated’, and ‘colorect* or colon* or rectum or rectal’, ‘cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or carcinom* or neoplas* or adenocarcinoma* or malignan*’ and ‘prognos* or survival or recurren* or mortality or predict* or outcome* or death’. In our secondary analysis concerning patients using aspirin, we also combined ‘aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDS’ as searching words with the Boolean logical operator ‘AND’. We also manually searched recent relevant papers (since 2004) in major journals such as Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology (Annals of Oncology), American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (Diseases of the Colon & Rectum) and JNCI (the Journal of the National Cancer Institute). The references of primary selected studies, reviews or meta-analyses were scrutinized for additional records that were not identified through database search. We did not apply restrictions to the date or language in our search strategy.

study selection and inclusion criteria

Two reviewers (ZM and CD) independently selected and identified the appropriate studies based on the prespecified selection criteria. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion or the senior author (SO). Prospective or retrospective studies if all of the following criteria were met: (i) studies published as an original article, regardless of the language; (ii) studies reporting on the outcome measures, such as overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS); and (iii) studies evaluating the PIK3CA mutation status in resected samples of primary CRC and providing relevant patient survival data with a hazard ratio (HR) estimate and its 95% confidence interval (CI) comparing PIK3CA-mutated cases with PIK3CA-wild-type cases. The exclusion criteria were: (i) studies having no prognostic outcomes recorded; (ii) studies including no sufficient data for analysis; and (iii) letters, comments, reviews or meta-analyses containing no original data. When more than one publication reported on the same population or overlapping populations, a study with a larger sample size (with PIK3CA mutation data) was selected into the meta-analysis.

data extraction and quality assessment

For each study, the following details were extracted: the full names of the first and last authors; publication year; study design; country where the study was carried out; number of hospitals involved; number of outcome events (number of PIK3CA mutated aspirin user); sample size; tumor site and disease stage; mutation detection assay; number of PIK3CA mutants; the availability of KRAS and BRAF mutation status data; survival end points; and HRs with corresponding 95% CIs and adjustment variables. For each study, we assessed the quality of the evidence on the association between the CRC survival outcomes and PIK3CA mutation status using a set of modified predefined criteria for evaluating the quality of the studies [41, 42].

statistical analyses

The primary outcomes of interest were OS and PFS of CRC patients with PIK3CA mutations compared with those with wild-type PIK3CA. For the quantitative aggregation of the survival outcomes, the HRs with corresponding 95% CIs were directly retrieved from the original studies and pooled with the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model [43] or using the method described by Parmar et al. [44]. We investigated the between-study heterogeneity by the Cochran's Q-test and I2 statistic, and a P value for heterogeneity by the I2 value ≥50% suggested substantial heterogeneity [45]. The source of heterogeneity was explored using subgroup analyses by examining all the possible factors that could explain the heterogeneity observed. Differences between the subgroups were assessed using the methods described by Deeks et al. [46]. We also conducted a secondary analysis based on aspirin use after CRC diagnosis (compared with non-use) in PIK3CA-mutated cancer patients. Further analysis was also carried out limited to those studies investigating CRC patients treated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy.

We assessed the evidence of publication bias by visual inspection of the contour-enhanced funnel plot symmetry as well as by Begg's regression and Egger's linear regression method [47, 48]. Duval's non-parametric trim-and-fill procedure was applied to further assess the possible effect of publication bias [49]. Moreover, the Copas model was used to conduct sensitivity analysis by considering both the effect size and sample size [50]. The statistical analyses were carried out with R software version 3.1.2. All statistical tests were two-sided, and significance was defined as a P value of <0.05.

results

search and selection of studies

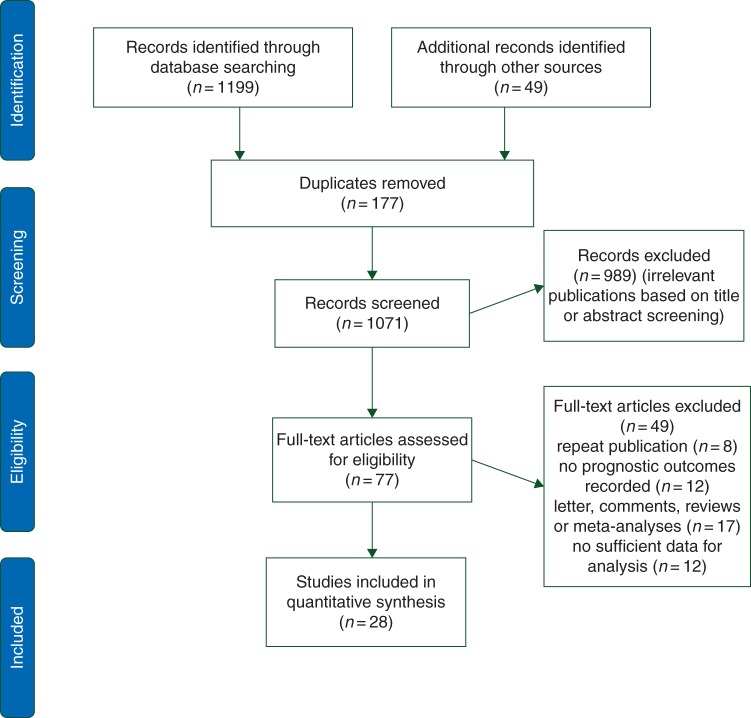

We identified 1248 eligible citations in the initial literature search and 77 potentially relevant studies for further review. After removing 49 studies, a total of 28 studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (Figure 1 and supplementary Tables S1, S7 and S8, available at Annals of Oncology online) [8–35].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection.

study characteristics

A total of 12 747 patients were included in the studies with a median sample size of 258 (inter-quartile range, 112–628). The median follow-up period ranged from 28 to 113 months. Table 1 and supplementary Table S11, available at Annals of Oncology online, provide the basic characteristics of each study that met our inclusion criteria. All studies were published between 2009 and 2015 in English peer-reviewed journals. For case ascertainment, 9 studies had a prospective design (7264 participants) [10, 12, 16, 18, 22, 23, 27, 34, 35], and 19 had a retrospective design (5483 participants) [8, 9, 11, 13–15, 17, 19–21, 24–26, 28–33].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies on survival outcomes of colorectal cancer patients according to PIK3CA mutation status

| Authors [ref.] | Study design | Country | No. of hospitals involved | No. of events | Sample size | Tumor site | Disease stage | Specimens used/mutation detection assay | No. of PIK3CA mutants |

KRAS data | BRAF data | Survival end points | Adjusted variables | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon 9 | Exon 20 | |||||||||||||

| Chen et al. [19] | Retrospective cohort | China | 1 | 88 | 214 | CRC | I–IV | FFPE/SS | 12 | 14 | Y | Y | OS | Age, sex, differentiation grade, tumor diameter, number of lymph nodes examined, TNM stage and KRAS/BRAF genotype |

| Day et al. [25] | Retrospective cohort | Australia | Multiple | NR | 589 | CRC | II, III | Fresh-frozen or FFPE/SS | 49 | 19 | Y | Y | DFS | Age at diagnosis, gender, tumor location, stage, differentiation, MSI status and adjuvant treatment |

| De Roock W et al. [31] | Retrospective cohort | 11 centers in seven European countries | Multiple | NR | 743 | CRC | IV | Fresh-frozen or FFPE/SS | 74 | 22 | Y | Y | OS, PFS | Age, sex, number of previous chemotherapy lines and center |

| Eklof et al. [24] | Retrospective cohorts | Sweden | Multiple | NR | 611 | CRC | I–IV | FFPE/SS | NR | 13 | Y | Y | CS | Sex, age, tumor site and tumor stage. |

| Farina Sarasqueta et al. [14] | Retrospective cohort | The Netherlands | Multiple | 183 | 616 | Colon cancer | I–III | FFPE/SS | 66 | 17 | Y | Y | CS | Age, gender, tumor location, adjuvant chemotherapy, T stage, MMR status, tumor differentiation |

| Garrido-Laguna I, et al. [28] | Retrospective cohort | USA | 1 | 25 | 168 | CRC | IV | FFPE/PS | 9 | 5 | Y | Y | OS | Sex, tumor stage, KRAS and BRAF status |

| Gavin et al. [27] | Prospective cohort | USA | Multiple | NR | 2299 | Colon cancer | II, III | FFPE/SS | NR | NR | Y | Y | OS, RFS | BRAF, KRAS, KRAS, NRAS, MET and PIK3CA mutations |

| He et al. [35] | Prospective cohort | The Netherlands | Multiple | 84 | 240 | Rectal cancer | I–III | Fresh-frozen/SS | 12 | 7 | Y | Y | RFS | TNM stage, CRM |

| Iida et al. [13] | Retrospective cohort | Japan | 1 | 26 | 165 | CRC | I–IV | FFPE/SS | NR | NR | Y | N | CS | Sex, age, tumor location, stage, differentiation, methylation etc. |

| Kang et al. [23] | Prospective population-based cohort | USA | Multiple | 59 | 304 | CRC | I–IV | FFPE/SS | NR | NR | Y | Y | OS | Age, sex, tumor location, chemotherapy, MSI status etc. |

| Karapetis et al. [18] | Prospective cohort | Canada, Australia, New Zealand | Multiple | NR | 572 | CRC | IV | FFPE/SS | 44 | 6 | Y | Y | OS, PFS | ECOG performance status, gender, age, baseline lactate dehydrogenase level, baseline alkaline phosphatase, baseline hemoglobin, number of disease sites, number of previous chemotherapy drug classes, primary tumor site, presence of liver metastases, treatment, BRAF/PTEN status |

| Kishiki et al. [17] | Retrospective cohort | Japan | 1 | 6 | 84 | CRC | IV | FFPE/SS | NR | NR | Y | Y | OS, PFS | KRAS, BRAF mutation status; PTEN or MET expression |

| Liao et al. [30] | Retrospective cohort | China | 1 | NR | 61 | CRC | IV | FFPE/PS | NR | NR | Y | Y | OS | Treatment regimens, mutation status, metastatic location, number of metastatic lesions |

| Liao et al. [12] | Prospective cohort | USA | Multiple | 552 | 1170 | CRC | I–IV | FFPE/PS | 116 | 80 | Y | Y | OS, CS | Age at diagnosis, sex, tumor location, CIMP status, MSI status, LINE-1 methylation, BRAF mutation, KRAS mutation |

| Manceau et al. [8] | Retrospective cohort | France | Multiple | 99 | 693 | Colon cancer | I–III | Fresh-frozen/SS | 66 | 43 | Y | Y | RFS, OS | Sex, age, tumor location, stage, KRAS, BRAF mutation status, CIMP status |

| Mouradov et al. [22] | VICTOR and community prospective cohort | Australia UK, | Multiple | 99 | 1197 | CRC | II, III | FFPE/SS | NR | NR | Y | Y | DFS | Age, gender, cancer location, tumor stage and grade, use of radiochemotherapy, randomization to rofecoxib treatment, MSI, CIN, measures of LOH and specific gene mutations |

| Ogino et al. [21] | Retrospective cohort | USA | Multiple | 502 | 627 | Colon cancer | III | FFPE/PS | 48 | 25 | Y | Y | OS, RFS, DFS | Age, sex, baseline body mass index, family history of colorectal cancer in first-degree relatives, baseline performance status, presence of bowel perforation or obstruction at the time of surgery, treatment arm, tumor location, stage, KRAS, BRAF and MSI status |

| Perrone et al. [15] | Retrospective cohort | Italy | 1 | NR | 32 | CRC | IV | FFPE/SS | NR | NR | Y | Y | PFS | NR |

| Phipps et al. [20] | Retrospective woman cohort | USA | Multiple | 97 | 275 | CRC | I–IV | FFPE/PS, SS | NR | NR | Y | Y | OS, CS | Age and stage at diagnosis |

| Prenen et al. [34] | Prospective cohort | Belgium | Multiple | NR | 200 | CRC | IV | FFPE/SS | NR | NR | Y | N | OS, PFS | NR |

| Reimers et al. [16] | VICTOR and community prospective cohort | The Netherlands | Multiple | 298 | 631 | Colon cancer | I–IV | FFPE/SS | NR | NR | N | N | OS | Sex, age, comorbidity, year of incidence, histologic grade, stage and chemotherapy |

| Rosty et al. [10] | Prospective cohort | Australia, New Zealand | Multiple | 261 | 651 | CRC | I–IV | FFPE/SS | 81 | 27 | Y | Y | OS | Sex, age at diagnosis, tumor location, histologic grade, MSI status, MGMT expression, KRAS and BRAF status |

| Saridaki et al. [29] | Retrospective cohort | Greece | 1 | NR | 112 | CRC | I–IV | FFPE/SS | 8 | 3 | Y | Y | OS, PFS | KRAS, BRAF mutation, EREG mRNA expression, skin rash, tumor differentiation |

| Sartore-Bianchi et al. [33] | Retrospective cohort | Italy, Switzerland | Multiple | 88 | 110 | CRC | IV | FFPE/SS | 4 | 11 | N | Y | OS, PFS | Score of cutaneous toxicity and number of previous chemotherapy line |

| Sood et al. [26] | Retrospective cohort | USA | 1 | NR | 76 | CRC | IV | FFPE/PS | NR | NR | Y | Y | OS, PFS | NR |

| Souglakos et al. [32] | Retrospective cohort | Greece, USA | Multiple | 43 | 92 | CRC | I–IV | FFPE/SS | 18 | 8 | Y | Y | OS, PFS | Age, differentiation, tumor location, solitary metastasis and BRAF mutations |

| Ulivi et al. [11] | Retrospective cohort | Italy | 1 | NR | 67 | CRC | IV | FFPE/SS | 7 | 2 | Y | Y | OS, PFS | ECOG performance status, cutaneous toxicity, and number of previous chemotherapy lines |

| Zhu et al. [9] | Retrospective cohort | China | 1 | 21 | 148 | CRC | I–III | FFPE/PS | NR | NR | Y | Y | RFS | KRAS and BRAF mutation status, stage, distance to anal verge, CRM |

CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype; CIN, chromosomal instability; CRC, colorectal cancer; CRM, cumferential resection margin; CS, cancer-specific survival; DFS, disease-free survival; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EREG, epiregulin; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; LINE-1, long interspersed nucleotide element-1; LOH, loss of heterozygosity; MMR, mismatch repair; MSI, microsatellite instability; N, no; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, pyrosequencing; RFS, recurrence-free survival; SS, Sanger sequencing; Y, yes.

Ten studies involved single-center data [9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 26, 28–30], whereas 18 were multi-center studies [8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20–25, 27, 31–35]. Seven studies were conducted in the USA [12, 20, 21, 23, 26–28], nine in Europe [8, 11, 14–16, 24, 29, 34, 35], five in Asia [9, 13, 17, 19, 30], and seven covered multiple continents [10, 18, 22, 25, 31–33]. Nineteen studies investigated the association between PIK3CA status and OS for CRC patients [8, 10–12, 17–21, 23, 26–34], whereas 10 studies reported the PFS [11, 15, 17, 18, 26, 29, 31–34]. Most studies involved patients with both colon and rectal cancers. Five studies evaluated only colon cancer [8, 14, 16, 21, 27], and one study evaluated only rectal cancer [35]. A mixture of I–IV disease stages was included in 18 studies [8–10, 12–14, 16, 19–25, 27, 29, 32, 35], and only stage IV cancers were included in 10 studies [11, 15, 17, 18, 26, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34]. Two methods for detecting the sequence were employed in the included studies; 21 used Sanger sequencing [8, 10, 11, 13–19, 22–25, 27, 29, 31–35]; 6 used pyrosequencing [9, 12, 21, 26, 28, 30]; and 1 used pyrosequencing combined with Sanger sequencing [20]. Most of the included studies (24/28) used formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) CRC samples, one used fresh-frozen samples and the other three used both FFPE CRC samples and fresh-frozen samples (Table 2). Most studies investigated the prognostic impact of the overall PIK3CA mutation status (exon 9 or 20 mutation) on CRC survival. Five studies also separately assessed the prognostic association of PIK3CA exon 20 or 9 mutations with the CRC survival [12, 14, 21, 24, 31]; one study investigated the effect of concomitant PIK3CA exon 9 and 20 mutations with CRC survival [12]. Gender, age at diagnosis, tumor location, stage and KRAS and BRAF mutation status are commonly investigated covariates that were adjusted for in Cox's proportional-hazard model evaluation of the relationship between the PIK3CA mutations and survival.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of the associations between PIK3CA mutation and overall survival or progression-free survival

| Comparison variables | Overall survival |

Progression-free survival |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies (I2 statistics %; Phet) | HR (95% CI) | Pinteraction | Number of studies (I2 statistics %; Phet) | HR (95% CI) | Pinteraction | |

| Total | 19 (40.9; 0.027) | 0.96 (0.83–1.12) | NA | 10 (0; 0.93) | 1.2 (0.98–1.46) | NA |

| Study design | 0.77 | 0.27 | ||||

| Prospective | 7 (54.3; 0.041) | 0.95 (0.79–1.15) | 2 (0; 0.93) | 1.08 (0.82–1.41) | ||

| Retrospective | 12 (37.1; 0.080) | 1.00 (0.77–1.29) | 8 (0; 0.97) | 1.35 (1.01–1.81) | ||

| Research country | 0.33 | 0.75 | ||||

| USA | 7 (0; 0.96) | 0.93 (0.81–1.06) | 1 (—) | 2.31 (1.07–5.01) | ||

| Europe | 6 (73.1; 0.001) | 0.90 (0.63–1.30) | 6 (0; 0.96) | 1.17 (0.93–1.46) | ||

| Asia | 3 (0, 0.82) | 1.57 (0.73–3.35) | 1 (—) | 2.22 (1.07–3.86) | ||

| Cross-continent | 3 (0, 0.75) | 1.16 (0.86–1.57) | 2 (0; 0.38) | 1.18 (0.75–1.86) | ||

| Centers involved | 0.13 | 0.16 | ||||

| Single | 7 (0; 0.97) | 1.33 (0.86–2.05) | 5 (0; 0.99) | 2.00 (0.95–4.22) | ||

| Multiple | 12 (56.2; 0.005) | 0.93 (0.78–1.10) | 5 (0; 0.93) | 1.15 (0.94–1.41) | ||

| Stage of disease | 0.033 | 0.29 | ||||

| I–III | 10 (56.5; 0.011) | 0.86 (0.70–1.06) | 2 (0; 0.92) | 2.00 (0.76–5.29) | ||

| IV | 9 (0; 0.99) | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) | 8 (0; 0.97) | 1.17 (0.95–1.43) | ||

| Sample size | 0.14 | 0.081 | ||||

| <200 | 8 (0; 0.95) | 1.24 (0.87–1.76) | 7 (0; 0.99) | 1.99 (1.09–3.64) | ||

| ≥200 | 11 (58.5; 0.004) | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) | 3 (0; 0.97) | 1.12 (0.91–1.39) | ||

| Tumor location | 0.018 | NA | ||||

| Colon | 3 (78.4; 0.003) | 0.70 (0.50–0.98) | – | – | – | |

| Rectum | – | – | – | – | ||

| Colorectum | 16 (0; 0.97) | 1.08 (0.95–1.22) | 10 (0; 0.93) | 1.2 (0.98–1.46) | ||

| Mutation detection assay | 0.18 | 0.51 | ||||

| Pyrosequencing | 6 (64.8; 0.009) | 0.79 (0.59–1.06) | 1 (—) | 2.31 (0.32–16.6) | ||

| Sanger sequencing | 12 (0; 0.87) | 1.05 (0.92–1.19) | 9 (0; 0.96) | 1.19 (0.97–1.45) | ||

CI, confidence interval; het, heterogeneity; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not available.

relationship between PIK3CA mutations and CRC prognosis

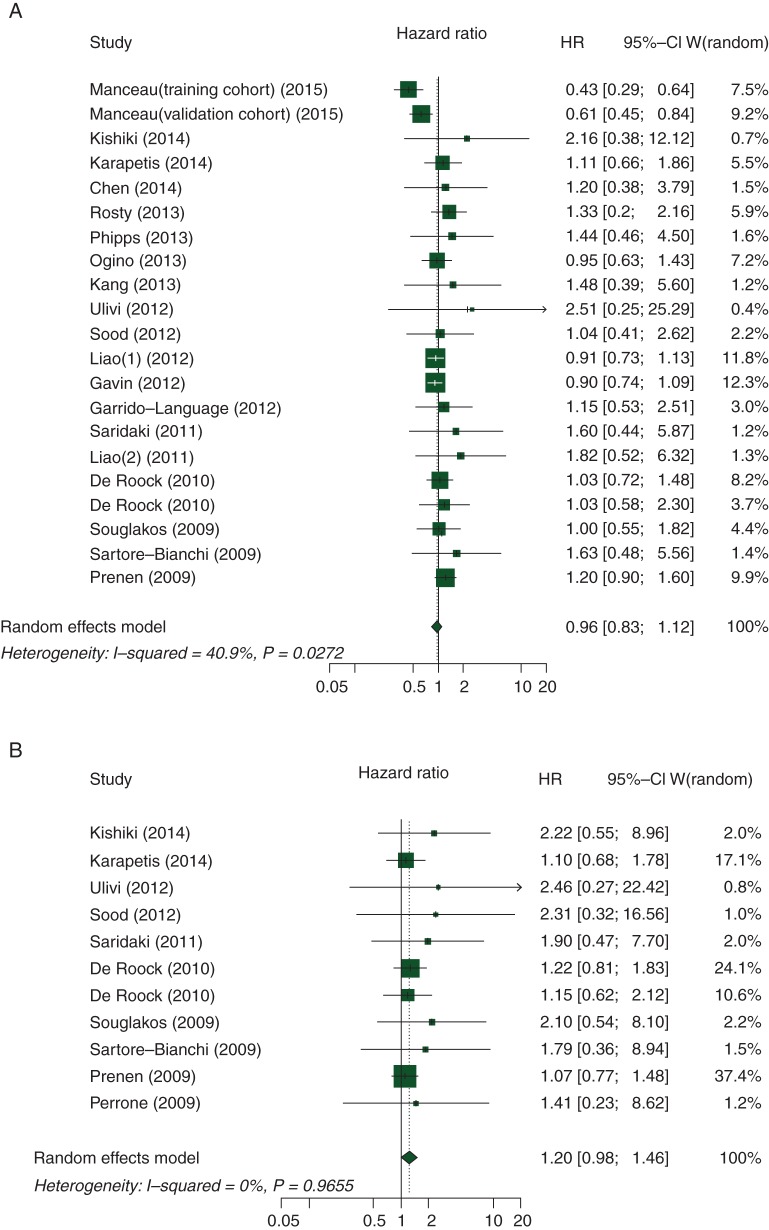

As shown in Figure 2A, the summary HR for the OS comparing PIK3CA mutation versus wild-type PIK3CA was 0.96 (95% CI 0.83–1.12; P = 0.60), and there was moderate heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 40.9%, Pheterogeneity = 0.027). Figure 2B summarizes the HR (1.20; 95% CI 0.98–1.46; P = 0.079) for PFS, and there was no heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0, Pheterogeneity = 0.97). We also found no association between the PIK3CA mutation status and survival in patients with CRC in terms of other outcome measures (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 2.

Association between PIK3CA mutation status and (A) overall survival and (B) progression-free survival.

Table 2 presents the results of the subgroup analyses by potential sources of heterogeneity among certain major clinical characteristics of the included studies for the OS and PFS. The summary HR estimates in most subgroups were not significantly altered by the study characteristics, including the study design, research country, the number of centers involved, sample size and mutation detection assay. A possible interaction was noted in two features (stage of disease and tumor location) for OS, although there was multiple hypothesis testing by seven features. Results of analyses limited to stage I–III and stage IV are presented in Table 2. For patients with colon cancer, a possible prognostic association of PIK3CA mutation was noted. However, due to the small number of studies in each of these subgroups, further studies should investigate the prognostic association of PIK3CA mutation in these subgroups.

Five studies reported on the prognostic association of PIK3CA exon 9 mutation, and that of PIK3CA exon 20 mutation, separately [12, 14, 21, 24, 31]. Nevertheless, neither exon 9 nor exon 20 PIK3CA mutations was significantly associated with survival (supplementary Table S3 and supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). We assessed a difference in frequencies of PIK3CA mutations in exon 9 versus exon 20 among the included studies. A difference in studies that showed varying frequencies of mutations in exon 9 and exon 20 did not appear to influence our main conclusion of no substantial prognostic role of PIK3CA mutation in CRC (supplementary Table S10, available at Annals of Oncology online).

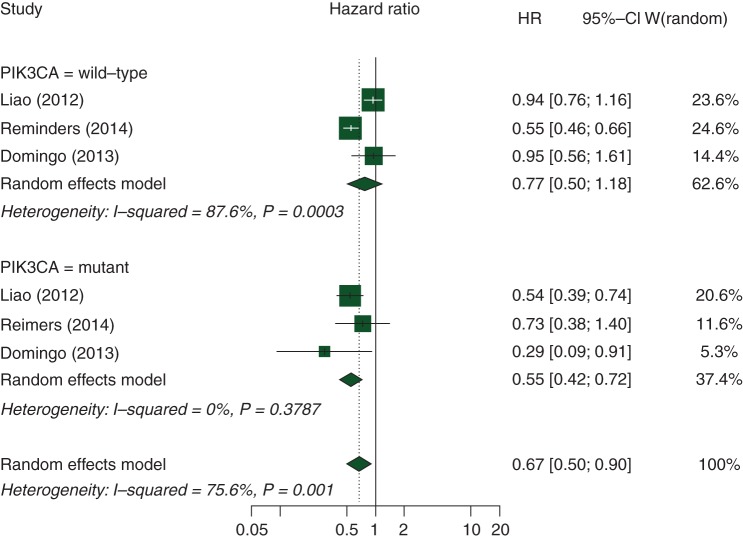

prognostic association of post-diagnosis aspirin use according to PIK3CA mutation status in CRC

In our secondary analysis, we identified three studies investigating the prognostic association of post-diagnosis aspirin use according to PIK3CA mutation status [16, 38, 39] (supplementary Table S11, available at Annals of Oncology online). Compared with aspirin non-users, regular aspirin use after CRC diagnosis was associated with longer OS in PIK3CA-mutated CRC patients (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.42–0.72; P = 0.015), but not in PIK3CA-wild-type CRC patients (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.50–1.18; P = 0.20; supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online and Figure 3). Furthermore, we did not observe statistically significant association of tumor PIK3CA mutations with PFS (HR 1.20, 95% CI 0.98–1.46; P = 0.079) or OS (HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.97–1.39; P = 0.138) in metastatic CRC patients treated with anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies.

Figure 3.

Summary estimates of the hazard ratio (and 95% confidence interval) for the overall survival of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients with mutated versus wild-type PIK3CA in patients who regularly ingested aspirin after a CRC diagnosis.

study quality and publication bias

The methodological quality score of the prognosis studies was moderate to high in 86% (24/28) of the included studies according to the quality score (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online); most studies had adequate follow-up and prognostic factor measurement, had a sufficient measurement of outcomes, carried out appropriate covariate measurements and used appropriate statistical analysis, but most studies used hospital-based convenience sample, and only rare studies [10, 12, 16, 23, 24] did use a population-representative sample (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

We also carried out a subgroup analysis according to the study quality, which showed no significant difference among the low-, moderate- and high-quality studies for OS (P = 0.22) or PFS (P = 0.68). The summary HRs for the OS were similar for studies with low quality (n = 3; HR 1.20, 95% CI 0.92–1.57; I2 = 0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.85), moderate quality (n = 10; 0.99 95% CI 0.85–1.14; I2 = 0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.95) and high quality (n = 6; 0.84, 95% CI 0.61–1.15; I2 = 71.8%, Pheterogeneity = 0.002). Similar results were obtained stratified by some of the clinical, pathological and molecular features for the OS and PFS panels (supplementary Tables S6 and S9, available at Annals of Oncology online).

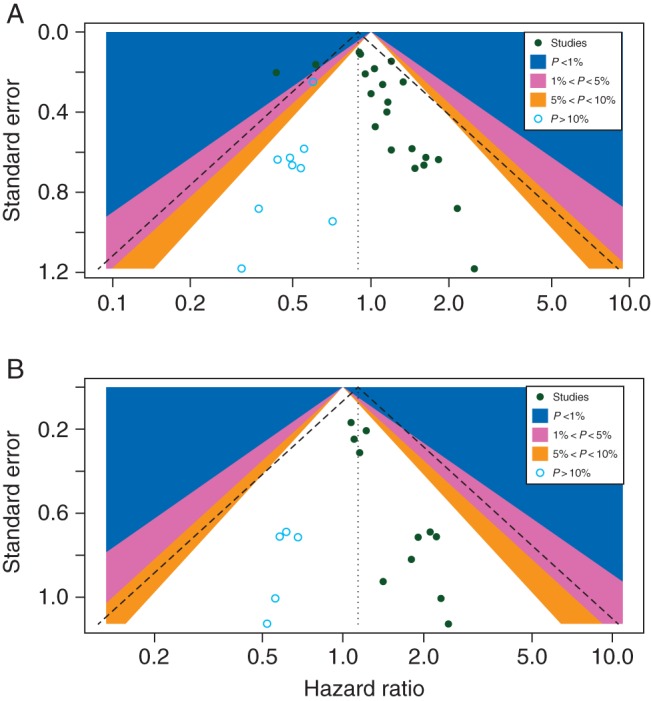

For OS, the contour-enhanced funnel plot demonstrated asymmetry, indicating the presence of publication bias (Figure 4A). The hollow circles show the eight missing studies that lay in the non-significant regions of the plot, suggesting that the asymmetry was attributed mainly to publication bias, which was further confirmed with the Begg's rank correlation test (P = 0.016). The adjusted random effects summary HRs of 0.89 (95% CI 0.78–1.03) obtained using the trim-and-fill method and 0.90 (95% CI 0.76–1.07) using the Copas model were consistent with our primary analysis. For the PFS, there was also evidence of asymmetry (Figure 4B). The results did not significantly change after applying the trim-and-fill method when including five missing studies, with the adjusted random effects summary HR of 1.14 (95% CI 0.94–1.38), similar to the summary HR of 1.16 (95% CI 0.95–1.42) using the Copas model (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 4.

(A) Contour-enhanced funnel plot for meta-analysis of the association between the PIK3CA mutation status and overall survival. The left blank area represents the area where eight studies (blue circles) were included when the trim-and-fill method was applied. (B) Contour-enhanced funnel plot for meta-analysis of the association between the PIK3CA mutation status and progression-free survival. The left blank area represents the area where five studies (blue circles) were included when the trim-and-fill method was applied.

discussion

We conducted this study to test the hypothesis that PIK3CA mutation in CRC might be associated with patient survival. Studies have demonstrated that PIK3CA mutations in CRC are related to various clinical and tumor molecular features, including associations with KRAS mutations and proximal tumor location, which may be due to varying biogeographical influence of the host–microbiota–tumor interaction along the colorectal axis [10, 51]. As PIK3CA has been known as one of the major driver oncogenes in CRC, the prognostic significance of PIK3CA mutations in CRC needs to be elucidated.

Our current systematic review and meta-analysis have demonstrated that the PIK3CA mutation status is not significantly associated with CRC patient survival. PIK3CA mutation status did not appear to have a substantial prognostic role in most of the subgroups examined according to certain relevant study characteristics, including study design, country, hospital, sample size and mutation detection assay. The survival association remained similar when the results were adjusted by the trim-and-fill method, or Copas model, considering the publication bias. There are a limited number of studies that examined a prognostic role of PIK3CA exon 9 mutations and exon 20 mutations, separately [12, 14, 21, 24, 31], and there is only one study that examined a prognostic role of coexisting mutations in both exons 9 and 20 in PIK3CA in CRC [12]. Interestingly, our secondary analysis has provided evidence for a prognostic role of regular aspirin use after CRC diagnosis (compared with non-use) in PIK3CA-mutated CRC patients, but not in PIK3CA-wild-type CRC patients.

PIK3CA mutation has no substantial prognostic role, in that some tumors have PIK3CA mutation as a driver mutation plus other driver mutations, while other tumors do not carry PIK3CA mutation but have another set of driver mutations. Tumor behavior may depend on multiple differing driver events as well as interaction of many molecular alterations in tumor, not solely on PIK3CA mutation status. Moreover, host factors such as immune response to tumor may influence prognosis. Thus, it is not surprising to find that any driver mutation (such as PIK3CA mutation) has no substantial prognostic role.

In the meta-analysis of OS, moderate inter-study heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 40.9%, Pheterogeneity = 0.027). We found that one study with a large sample size contributed to almost all of the observed heterogeneity [8]. Sensitivity analyses showed that exclusion of this study did not largely alter the pooled estimate (HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.92–1.13; I2 = 0, Pheterogeneity = 0.95). The results using the trim-and-fill model, Copas model and subgroup analyses based on some main clinical variables were consistent with our primary analyses, indicating that our results were robust and not affected by publication bias. However, caution is warranted when interpreting the results, because publication bias is ubiquitous [52] and statistical tests for publication bias are imperfect.

Three previous systematic reviews have outlined the PIK3CA mutation status for predicting outcome in metastatic CRC [53–55]. The first meta-analysis by Mao et al. found that stage IV patients with PIK3CA exon 20 mutations had a shorter PFS and OS, which was observed only in one study with KRAS wild-type metastatic CRC patients treated with anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies. The findings of the other two reviews by Wu et al. and Therkildsen et al. were consistent with the results of the first, which showed that PIK3CA mutations were significantly associated with worse PFS and shorter OS in metastatic CRC with anti-EGFR treatment. However, no previous systematic reviews or meta-analyses have assessed overall prognostic significance of tumor PIK3CA mutation in patients with CRC in all stages.

Our meta-analysis is the first to provide robust statistical evidence against substantial prognostic role of PIK3CA mutation status in CRC patients. Although four previous studies [9, 11, 13, 14] showed a prognostic association of PIK3CA mutation in CRC, the statistical power was limited due to the small sample sizes of these studies (ranging from 67 to 616). Several factors might have contributed to the seemingly contradictory results of these studies. First, sample sizes enormously vary from study to study in the literature. It is well known that smaller studies generate unstable estimates of effect sizes for any association, and are prone to publication bias. The funnel plots (Figure 4) clearly demonstrated asymmetrical distribution of studies with low statistical power. Secondly, study designs greatly vary; many studies used a convenience sample from a single hospital (with unaccountable selection bias), while others used cases in clinical trials (with highly selected enrolment samples) either in a single institution or multiple institutions, or population-based CRC samples in epidemiologic settings. Thirdly, there are differences in mutation detection assays; two main detection systems used are pyrosequencing and Sanger sequencing. The previous validation study demonstrated higher analytic sensitivity of pyrosequencing over Sanger sequencing [56]. Fourthly, somewhat related to the second point, disease characteristics including disease stage and tumor location vary from study to study, which might cause heterogeneity in study findings. Studies have shown that PIK3CA mutations are more common in proximal colon cancer than in distal colon cancer and rectal cancer [10, 51, 57]. We conducted subgroup analyses according to various study characteristics, and found no substantial heterogeneity in the prognostic association of tumor PIK3CA mutation. Moreover, we applied the trim-and-fill model and Copas model for adjustment, and the results were consistent, indicating no significant association between PIK3CA mutation and CRC patient survival.

There are limitations in our systematic review. First, the statistical analysis of publication bias was not well powered because of the limited number of included studies (n = 28), although the results were adjusted by two models (trim-and-fill and Copas). Secondly, we could not perform sensitivity analyses related to the KRAS, BRAF mutation or microsatellite status, patient treatment regimen or detailed subgroup analyses according to the tumor site (such as left colon cancer, right colon cancer and rectal cancer) and disease stage (stages II, III and IV, separately) because of limited availability of subgroup analysis data in the included studies. Some of these factors have been associated with both PIK3CA mutation and prognosis in CRC patients. Thirdly, the different survival analysis methods could have affected the accuracy and precision of the pooled estimates. Although the majority of the studies used the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, other studies did not report the statistical model [15, 26, 34], while another study applied univariate analysis only (without providing multivariate analysis data) [28]. In addition, adjustment variables varied considerably. Fourthly, we could not adequately assess the risk of bias for each of publication because details on the analysis were not available in many of the original reports. In addition, we were not able to contact the authors or sponsors of some studies to retrieve the data [58]. Although additional data such as Kaplan–Meier curves were provided for us to estimate the HRs and 95% CI in some studies [15, 18, 26, 33, 34], such estimations might have led to uncertain bias for pooled estimates. Fifthly, as reported [55, 59, 60], detection limits (analytical sensitivity) of the Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing techniques were generally 5%–25% of mutant alleles among all alleles, and hence, false-negative laboratory results remain problems in our meta-analysis.

The present work has several important strengths. First, we conducted a systematic, comprehensive and reproducible search of the relevant studies in multiple online databases without language or publication status limitations, enabling us to select the appropriate studies for our meta-analysis. Secondly, the large sample size including over 12 000 patients enabled us to quantitatively assess the association of the PIK3CA mutation status with CRC prognosis, making it the most powerful and comprehensive synthesis of the evidence on this issue to date. Thirdly, appropriate subgroup analyses were carried out for certain key study characteristics, such as the study design, disease stage, mutation detection method, follow-up period and overall study quality, and we obtained generally consistent findings independent of most of the study characteristics. Fourthly, although there was subjectivity in our assessment, we formally rated the strength of evidence based on the quality scale for the existing prognostic studies. Fifthly, most studies provided null associations with PIK3CA mutation status, while others with negative or positive associations, which indicated the uncertainty of the survival outcomes for PIK3CA mutation in CRC. Besides, the potential for selection bias was acknowledged, we believe it was minimized by the strict pre-specification of screening process based on study eligibility criteria. Furthermore, we utilized the multiple modalities, to assess the extent of publication bias.

In summary, our current systematic review and meta-analysis provide evidence that do not support a substantial prognostic role of PIK3CA mutation status in CRC. Our data suggest a differential prognostic association of aspirin use after the diagnosis of CRC according to tumor PIK3CA mutation status, which needs to be confirmed by further studies. Large-scale or multi-center studies with patient-level data are warranted to establish the validity of the predictive role of PIK3CA mutation status in CRC for specific clinical or molecular profiles as well as treatment outcomes.

standardized official symbols for genes and gene products

We use HUGO (Human Genome Organisation)-approved official symbols for genes and gene products, including BRAF, EREG, KRAS, MGMT, PIK3CA and PTEN, all of which are described at www.genenames.org.

funding

This research was supported by USA National Institute of Health (grant no. R01CA151993 and R35CA197735), Shanghai TCM promotion “3-year action plan” (grant no. ZY3-CCCX-3-3034 and ZY3-CCCX-2-1003), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant no. 14401931000). Shanghai Key Laboratory of Psychotic Disorders sponsored by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant no. 13dz2260500).

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

references

- 1.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature 2006; 441: 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samuels Y, Diaz LA Jr, Schmidt-Kittler O et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 2005; 7: 561–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dienstmann R, Salazar R, Tabernero J. Personalizing colon cancer adjuvant therapy: selecting optimal treatments for individual patients. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 1787–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ et al. PIK3CA mutation is associated with poor prognosis among patients with curatively resected colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 1477–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nosho K, Kawasaki T, Ohnishi M et al. PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer: relationship with genetic and epigenetic alterations. Neoplasia 2008; 10: 534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velho S, Oliveira C, Ferreira A et al. The prevalence of PIK3CA mutations in gastric and colon cancer. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41: 1649–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science 2004; 304: 554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manceau G, Marisa L, Boige V et al. PIK3CA mutations predict recurrence in localized microsatellite stable colon cancer. Cancer Med 2015; 4: 371–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu K, Yan H, Wang R et al. Mutations of KRAS and PIK3CA as independent predictors of distant metastases in colorectal cancer. Med Oncol 2014; 31: 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosty C, Young JP, Walsh MD et al. PIK3CA activating mutation in colorectal carcinoma: associations with molecular features and survival. PLoS One 2013; 8: e65479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ulivi P, Capelli L, Valgiusti M et al. Predictive role of multiple gene alterations in response to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer: a single center study. J Transl Med 2012; 10: 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao X, Morikawa T, Lochhead P et al. Prognostic role of PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer: cohort study and literature review. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 2257–2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iida S, Kato S, Ishiguro M et al. PIK3CA mutation and methylation influences the outcome of colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett 2012; 3: 565–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farina Sarasqueta A, Zeestraten EC, van Wezel T et al. PIK3CA kinase domain mutation identifies a subgroup of stage III colon cancer patients with poor prognosis. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2011; 34: 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perrone F, Lampis A, Orsenigo M et al. PI3KCA/PTEN deregulation contributes to impaired responses to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2009; 20: 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reimers MS, Bastiaannet E, Langley RE et al. Expression of HLA class I antigen, aspirin use, and survival after a diagnosis of colon cancer. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174: 732–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kishiki T, Ohnishi H, Masaki T et al. Overexpression of MET is a new predictive marker for anti-EGFR therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer with wild-type KRAS. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2014; 73: 749–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karapetis CS, Jonker D, Daneshmand M et al. PIK3CA, BRAF, and PTEN status and benefit from cetuximab in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer—results from NCIC CTG/AGITG CO.17. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 744–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J, Guo F, Shi X et al. BRAF V600E mutation and KRAS codon 13 mutations predict poor survival in Chinese colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phipps AI, Makar KW, Newcomb PA. Descriptive profile of PIK3CA-mutated colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. Int J Colorectal Dis 2013; 28: 1637–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogino S, Liao X, Imamura Y et al. Predictive and prognostic analysis of PIK3CA mutation in stage III colon cancer intergroup trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105: 1789–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mouradov D, Domingo E, Gibbs P et al. Survival in stage II/III colorectal cancer is independently predicted by chromosomal and microsatellite instability, but not by specific driver mutations. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 1785–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang M, Shen XJ, Kim S et al. Somatic gene mutations in African Americans may predict worse outcomes in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biomark 2013; 13: 359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eklof V, Wikberg ML, Edin S et al. The prognostic role of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 2153–2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Day FL, Jorissen RN, Lipton L et al. PIK3CA and PTEN gene and exon mutation-specific clinicopathologic and molecular associations in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19: 3285–3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sood A, McClain D, Maitra R et al. PTEN gene expression and mutations in the PIK3CA gene as predictors of clinical benefit to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapy in patients with KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2012; 11: 143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavin PG, Colangelo LH, Fumagalli D et al. Mutation profiling and microsatellite instability in stage II and III colon cancer: an assessment of their prognostic and oxaliplatin predictive value. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 6531–6541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrido-Laguna I, Hong DS, Janku F et al. KRASness and PIK3CAness in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: outcome after treatment with early-phase trials with targeted pathway inhibitors. PLoS One 2012; 7: e38033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saridaki Z, Tzardi M, Papadaki C et al. Impact of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutations, PTEN, AREG, EREG expression and skin rash in >/= 2 line cetuximab-based therapy of colorectal cancer patients. PLoS One 2011; 6: e15980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao W, Liao Y, Zhou JX et al. Gene mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor signaling network and their association with survival in Chinese patients with metastatic colorectal cancers. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2010; 293: 1506–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Souglakos J, Philips J, Wang R et al. Prognostic and predictive value of common mutations for treatment response and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2009; 101: 465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sartore-Bianchi A, Martini M, Molinari F et al. PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with clinical resistance to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 1851–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prenen H, De Schutter J, Jacobs B et al. PIK3CA mutations are not a major determinant of resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 3184–3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He Y, Van't Veer LJ, Mikolajewska-Hanclich I et al. PIK3CA mutations predict local recurrences in rectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 6956–6962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kato S, Iida S, Higuchi T et al. PIK3CA mutation is predictive of poor survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2007; 121: 1771–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shima K, Morikawa T, Yamauchi M et al. TGFBR2 and BAX mononucleotide tract mutations, microsatellite instability, and prognosis in 1072 colorectal cancers. PLoS One 2011; 6: e25062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1596–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Domingo E, Church DN, Sieber O et al. Evaluation of PIK3CA mutation as a predictor of benefit from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 4297–4305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Domingo E, Ramamoorthy R, Oukrif D et al. Use of multivariate analysis to suggest a new molecular classification of colorectal cancer. J Pathol 2013; 229: 441–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altman DG. Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. BMJ 2001; 323: 224–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayden JA, Cote P, Bombardier C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 427–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 1998; 17: 2815–2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context, 2nd edition 2008; 285–312. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994; 50: 1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000; 56: 455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin ZC, Zhou XH, He J. Statistical methods for dealing with publication bias in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2015; 34: 343–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamauchi M, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A et al. Assessment of colorectal cancer molecular features along bowel subsites challenges the conception of distinct dichotomy of proximal versus distal colorectum. Gut 2012; 61: 847–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ioannidis JP. How to make more published research true. PLoS Med 2014; 11: e1001747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu S, Gan Y, Wang X et al. PIK3CA mutation is associated with poor survival among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer following anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2013; 139: 891–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mao C, Yang ZY, Hu XF et al. PIK3CA exon 20 mutations as a potential biomarker for resistance to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 2012; 23: 1518–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Therkildsen C, Bergmann TK, Henrichsen-Schnack T et al. The predictive value of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN for anti-EGFR treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol 2014; 53(7): 852–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M et al. Sensitive sequencing method for KRAS mutation detection by Pyrosequencing. J Mol Diagn 2005; 7: 413–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamauchi M, Lochhead P, Morikawa T et al. Colorectal cancer: a tale of two sides or a continuum? Gut 2012; 61: 794–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kothari N, Kim R, Jorissen RN et al. Impact of regular aspirin use on overall and cancer-specific survival in patients with colorectal cancer harboring a PIK3CA mutation. Acta Oncol 2015; 54: 487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ang D, O'Gara R, Schilling A et al. Novel method for PIK3CA mutation analysis: locked nucleic acid–PCR sequencing. J Mol Diagn 2013; 15(3): 312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsiatis AC, Norris-Kirby A, Rich RG et al. Comparison of Sanger sequencing, pyrosequencing, and melting curve analysis for the detection of KRAS mutations: diagnostic and clinical implications. J Mol Diagn 2010; 12(4): 425–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.