Abstract

The role of tumor PD-L1 expression was investigated across the nivolumab clinical development program. Phase III nivolumab trials have shown that patients with tumors not expressing PD-L1 may benefit; therefore, testing is not required to select patients for therapy. The Dako PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx assay may be used to determine tumor PD-L1 expression as a complementary and informative test.

New therapies targeting the programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) are changing the outcomes of patients with advanced cancers, with randomized trials reporting improvements in overall survival (OS) compared with standard treatment [1–6]. However, there is debate about whether patients should be selected for treatment with these agents based on expression of the PD-1 ligand, PD-L1. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved nivolumab for the treatment of advanced melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma regardless of PD-L1 expression; pembrolizumab for advanced NSCLC in tumors expressing PD-L1, as determined by an FDA-approved test, and for advanced melanoma; and atezolizumab for previously treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, regardless of PD-L1 expression. The European Medicines Agency has approved nivolumab and pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma, and nivolumab for advanced NSCLC and RCC. The FDA also approved the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab for advanced melanoma. In addition, the FDA has approved companion (pembrolizumab) and complementary (nivolumab and atezolizumab) PD-L1 assays.

Key questions to inform the role of PD-L1 in patient selection include:

Does tumor PD-L1 expression identify a population deriving greater benefit from PD-1 inhibition than tumors not expressing PD-L1?

Do patients with low or no tumor PD-L1 expression benefit from PD-1-targeted therapy compared with the current standard of care?

Can tumor PD-L1 expression be reliably and consistently measured?

What threshold should be used to define tumor PD-L1-positive expression?

Across the clinical development program of nivolumab for multiple tumor indications, Bristol-Myers Squibb addressed these key questions as part of a comprehensive, prospective PD-L1 diagnostic strategy.

immunological control of tumor growth and role of PD-1 and PD-1 ligands

Tumor cells can up-regulate negative signals to block T-cell activation in their local microenvironment, avoiding elimination by the immune system [7]. PD-1 is a key inhibitory co-receptor expressed on activated T cells and on other immune cells, including B cells, natural killer cells, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and activated T regulatory cells [8, 9]. There are two identified ligands for PD-1, PD-L1 and PD-L2. Expressed by immune cells and other cell types, PD-L1 is involved in protecting tissues from excessive inflammation and autoimmune conditions [8, 10]. PD-L2 is primarily expressed on antigen-presenting cells [8].

Tumor cells may express PD-L1, and possibly PD-L2. Both ligands bind to PD-1 on T cells in the tumor microenvironment, inhibiting the T-cell response and facilitating tumor escape from the immune system. The aim of PD-1-directed therapy is to block this interaction, preventing or disrupting these inhibitory signals, and increase the ability of the immune system to eliminate tumor cells. PD-L1 has been shown to be expressed by different tumor cell types, including melanoma, NSCLC, RCC, glioblastoma, and multiple myeloma [9, 10]. Across studies and tumor types, tumor PD-L1 expression has variably been associated with poor or favorable prognosis, or had no association with prognosis [9]. In some tumor types, tumor PD-L1 expression may be a surrogate for the extent to which tumors can suppress immune-mediated elimination.

nivolumab clinical development: establishing the hypotheses

Nivolumab is a fully human IgG4 antibody that blocks the interaction of PD-1 with PD-L1 and PD-L2. In a phase I study in patients with advanced solid tumors, durable objective responses (OR; RECIST v1.0) were reported in patients with melanoma, NSCLC, and RCC [11]. The association between PD-L1 status and response was investigated in a subgroup of 42 patients; all patients in this subgroup who had an OR had at least one pretreatment tumor sample that stained positive for PD-L1 expression (defined as ≥5% of tumor cells having expression on the cell membrane as detected using the mouse monoclonal anti-PD-L1 antibody 5H1). In other phase I studies, lower frequencies of ORs were also observed in PD-L1 non-expressing tumors. These early data suggested an association between tumor cell PD-L1 expression and OR to nivolumab, meriting further investigation into the relationship between tumor PD-L1 expression and efficacy outcomes.

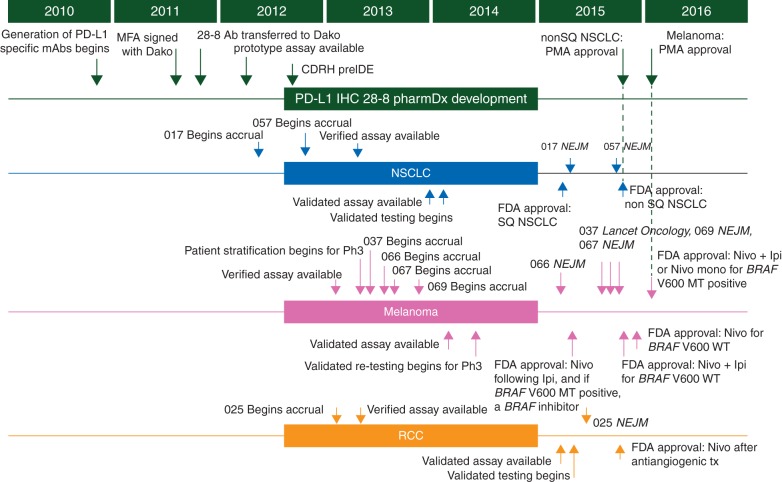

We hypothesized that in phase III registration trials in melanoma, NSCLC, and RCC, nivolumab would demonstrate superior OS to the standard of care in populations unselected for PD-L1 expression. However, in order to establish the relationship between tumor PD-L1 expression and clinical efficacy, we fully implemented an immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay for PD-L1 into the clinical development program. The trials required tumor tissue samples for all patients, and tumor PD-L1 expression was determined using the analytically validated Dako PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx assay [12, 13]. Efficacy outcomes were determined across predefined ranges of 1%, 5%, and 10% expression levels with a predetermined significance level of P <0.2 for a treatment–marker interaction. To establish the validated PD-L1 assay, we consulted academic and industry experts to gain their experience with the PD-L1 biomarker and assay technology. Evaluation of PD-L1 antibodies started early in the nivolumab development program, with the aim of expediting development of a sensitive, specific, and reproducible prototype IHC assay (Figure 1). We partnered with an experienced in vitro diagnostic company (Dako) to provide a high-quality IHC test for the clinical studies, and to optimize development, manufacturing, approval, and commercialization as required. We also began discussions with the FDA Center for Devices and Regulatory Health before analytical validation to ensure that our plans were consistent with a premarket approval application pathway that would be adequate for regulatory approval.

Figure 1.

Co-development of a companion diagnostic for tumor PD-L1, fully integrated into the clinical development of nivolumab. Ab = antibody; CDRH = Center for Devices and Radiological Health; IDE = investigational device exemption (application); IHC = immunohistochemistry; mAb = monoclonal antibody; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; PD-L1 = programmed death ligand 1; Ph3 = phase III; PMA = Premarket Approval Application; RCC = renal cell carcinoma; SQ = squamous.

nivolumab benefit across tumor PD-L1 expression subgroups

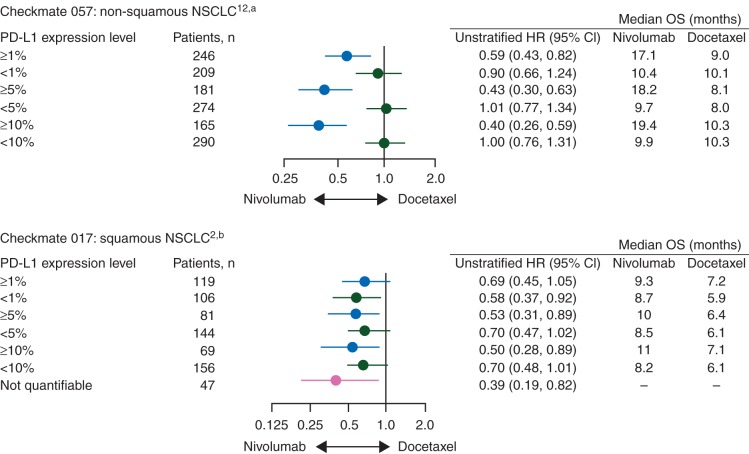

The nivolumab phase III data demonstrated superior OS to the standard of care in populations unselected for tumor PD-L1 expression. Nivolumab showed a consistent OS benefit in populations unselected for tumor PD-L1 expression in BRAF wild-type melanoma compared with dacarbazine [5], in squamous [2] and non-squamous [1] NSCLC compared with docetaxel, and in RCC compared with everolimus [4]. Survival benefit was seen across tumor PD-L1 expression groups in all tumor types, with the exception of non-squamous NSCLC [1, 2, 4, 5]. Data in non-squamous NSCLC suggested a predictive interaction between tumor PD-L1 expression and outcome for all efficacy end points (Figure 2) [1, 2, 14]. While this study showed no difference in OS between nivolumab and docetaxel among patients whose tumors did not express PD-L1, the improved safety profile and durability of ORs (median duration of response: nivolumab, 18.3 months; docetaxel, 5.6 months) with nivolumab suggest that it might be a reasonable option for patients regardless of tumor PD-L1 expression [1].

Figure 2.

Overall survival hazard ratios by tumor PD-L1 expression at baseline in nivolumab non-small-cell lung cancer phase III trials. aInteraction P-values are as follows: 0.06 (≥1%, <1%), <0.001 (≥5%, <5%), <0.001 (≥10%, <10%). bInteraction P-values are as follows: 0.56 (≥1%, <1%), 0.47 (≥5%, <5%), 0.41 (≥10%, <10%).

The efficacy and safety of nivolumab (alone or in combination with ipilimumab) versus ipilimumab alone were evaluated in previously untreated patients with advanced melanoma [15]. In patients with tumor PD-L1 expression ≥5%, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 14.0 months for both combination therapy and nivolumab and 3.9 months for ipilimumab; the median PFS in patients with tumor PD-L1 expression <5% was 11.2 months for the combination, 5.3 months for nivolumab, and 2.8 months for ipilimumab. However, OR rates were numerically higher for the combination than either agent alone regardless of tumor PD-L1 expression. OS data remain immature, but based on current evidence, nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab may provide better efficacy outcomes than either agent alone, particularly for patients with tumor PD-L1 expression <5%.

The safety and efficacy of nivolumab monotherapy was compared with everolimus in patients with advanced RCC previously treated with ≥1 antiangiogenic therapy [4]. There was quantifiable tumor PD-L1 expression in 92% of patients; 90% in the nivolumab group and 94% in the everolimus group. The median OS was higher for patients treated with nivolumab regardless of tumor PD-L1 expression.

PD-L1: a challenging biomarker

With over 13 000 clinical samples tested with the analytically validated PD-L1 assay, the nivolumab clinical development program has provided considerable evidence regarding the association between nivolumab efficacy and tumor PD-L1 expression. OS benefit has been demonstrated in NSCLC, melanoma, and RCC, regardless of tumor PD-L1 expression. For both non-squamous NSCLC and melanoma, tumor PD-L1 expression ≥1%, as measured with the Dako PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx assay [12, 13], is informative regarding the magnitude of treatment effect. Therefore, the assay was approved by the FDA and may be considered a ‘complementary diagnostic’, in contrast to a companion diagnostic that would be required for the safe and effective use of nivolumab.

Two ongoing phase III trials include patients with advanced NSCLC selected based on tumor PD-L1 expression. CheckMate 026 (NCT02041533) includes an enrichment design to investigate the role of nivolumab in first-line treatment among patients whose tumors express PD-L1. CheckMate 227 (NCT02477826) is evaluating the benefit of nivolumab monotherapy, nivolumab combined with ipilimumab, and nivolumab combined with chemotherapy compared with standard chemotherapy among patients stratified by PD-L1 tumor expression.

Beyond the relationship of tumor PD-L1 expression to nivolumab efficacy, questions regarding reliability, consistency, feasibility, and selection of an expression threshold remain controversial. Tumor PD-L1 expression is inducible, heterogeneous, and subject to pre-analytical variables. Furthermore, tumor PD-L1 expression is continuously distributed, in contrast to activating mutations that may define distinct tumor populations with different biology. Therefore, it may not be feasible to select an expression threshold that can identify biologically relevant subpopulations who may receive therapeutic benefit versus those who do not.

Further challenges stem from the development by multiple sponsors of PD-L1 assays using different monoclonal IHC antibody clones, scoring systems, and platforms in conjunction with different PD-1/PD-L1 therapeutics and the availability of several laboratory development tests [16, 17]. Efforts by industry collaborations and professional societies to compare analytical performance and standardize testing are underway [18, 19].

conclusions

The role of PD-L1 expression in association with PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint-directed therapy is rapidly evolving. Assay methodology, currently limited to IHC in vitro diagnostics, must be rigorously validated for analytical performance to provide for the clinical validation and utility of PD-L1 expression to be determined through adequately controlled phase III trials comparing the checkpoint inhibitor to standard of care. In all studies to date, patients with tumors that do not express PD-L1 may also receive OS and OR benefit from nivolumab; therefore, tumor PD-L1 expression testing is not required to select patients for nivolumab therapy when alternative second-line therapies are unavailable. Multiple phase III nivolumab clinical trials have demonstrated that the role of tumor PD-L1 expression is different across tumors and lines of therapy. In studies of non-squamous NSCLC and melanoma, tumor PD-L1 expression was associated with greater nivolumab treatment effect. In melanoma, tumor PD-L1 expression may inform which patients have a favorable risk to benefit profile with nivolumab monotherapy compared with combination therapy with ipilimumab. For these tumors, the Dako PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx assay has been established as a reliable complementary and informative test.

funding

This work was supported by funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

disclosure

All authors are employees of and stockholders in Bristol-Myers Squibb.

acknowledgements

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Lauren Gallagher and Anne Cooper (StemScientific, NJ, USA, an Ashfield company) and was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

references

- 1.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1627–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 123–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 1540–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF et al. ; CheckMate 025 Investigators. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1803–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomized, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 908–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakravarti N, Prieto VG. Predictive factors of activity of anti-programmed death 1/programmed death ligand-1 drugs: immunohistochemistry analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2015; 4: 743–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2008; 26: 677–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12: 252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou W, Chen L. Inhibitory B7-family molecules in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8: 467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2443–2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dako PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDX IFU. http://www.dako.com/download.pdf?objectid=128371002 (26 January 2016, date last accessed).

- 13.Phillips T, Simmons P, Inzunza HD et al. Development of an automated PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay for non-small cell lung cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2015; 23: 541–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.OPDIVO (Package Insert). Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cagle PT, Bernicker CH. Challenges to biomarker testing for PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2015; 139: 1477–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther 2015; 14: 847–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.FDA. A blueprint proposal for companion diagnostic comparability. 2015. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/NewsEvents/WorkshopsConferences/UCM439440.pdf (27 January 2016, date last accessed).

- 19.Kerr KM, Tsao MS, Nicholson AG et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 immunohistochemistry in lung cancer: in what state is this art? J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10: 985–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]