Genomic profiling of tumor tissue may identify gene signatures (GS) predictive of tumor response to treatment. We prospectively evaluated a GS linked to clinical benefit following MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic in patients with advanced melanoma. One-year overall survival was similar in patients with and without the GS: the GS was not predictive of outcome after MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic treatment.

Keywords: MAGE-A3 antigen, gene signature, melanoma, immunotherapy, predictive biomarkers

Abstract

Background

Genomic profiling of tumor tissue may aid in identifying predictive or prognostic gene signatures (GS) in some cancers. Retrospective gene expression profiling of melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer led to the characterization of a GS associated with clinical benefit, including improved overall survival (OS), following immunization with the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic. The goal of the present study was to prospectively evaluate the predictive value of the previously characterized GS.

Patients and methods

An open-label prospective phase II trial (‘PREDICT’) in patients with MAGE-A3-positive unresectable stage IIIB-C/IV-M1a melanoma.

Results

Of 123 subjects who received the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic, 71 (58.7%) displayed the predictive GS (GS+). The 1-year OS rate was 83.1%/83.3% in the GS+/GS− populations. The rate of progression-free survival at 12 months was 5.8%/4.1% in GS+/GS− patients. The median time-to-treatment failure was 2.7/2.4 months (GS+/GS−). There was one complete response (GS−) and two partial responses (GS+). The MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic was similarly immunogenic in both populations and had a clinically acceptable safety profile.

Conclusion

Treatment of patients with MAGE-A3-positive unresectable stage IIIB-C/IV-M1a melanoma with the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic demonstrated an overall 1-year OS rate of 83.5%. GS− and GS+ patients had similar 1-year OS rates, indicating that in this study, GS was not predictive of outcome. Unexpectedly, the objective response rate was lower in this study than in other studies carried out in the same setting with the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic. Investigation of a GS to predict clinical benefit to adjuvant MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic treatment is ongoing in another melanoma study.

This study is registered at www.clinicatrials.gov NCT00942162.

introduction

Gene expression profiling of tumors may help to define which tumors are likely to respond to treatment, and has been studied in various cancers, including melanoma [1]. Patients with advanced melanoma typically have a poor prognosis, with 1-year overall survival (OS) of 40%–60% in patients with AJCC stage IV (M1a–M1c) disease [2]. Immune checkpoint blockers, targeted inhibitors, and adoptive T-cell therapies improve outcomes in these patients [3], but are associated with toxicity, resistance, or technical issues, respectively, and other therapeutic approaches are warranted.

MAGE-A3 is a tumor antigen expressed in various cancers [4–6]. The MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic comprises a recombinant MAGE-A3 protein administered with the immunostimulant AS15 (MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic) [7]. Phase I–II trials studying MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic administered to melanoma or non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients provided encouraging clinical results, with induction of specific humoral and cellular immune responses and excellent safety [8–11]. Its efficacy as adjuvant therapy was further evaluated in large phase III studies in NSCLC (NCT00480025, MAGRIT) [12] and melanoma patients (NCT00796445, DERMA, results not yet published).

Microarray analysis of mRNA from pre-treatment biopsies of metastatic melanoma identified a gene signature (GS) comprising 84 genes, whose expression appeared associated with clinical benefit, including improved OS, in patients treated with MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic [1]. Expression of the same GS in patients with resected NSCLC suggested a similar correlation with clinical outcome following MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic. Our aim was to evaluate the value of this GS in predicting a response to MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic in a larger prospective trial. Because of frequent rapid progression in M1b-c melanoma patients, we included patients naive to previous systemic treatment with non-resectable stage IIIB-C and IV-M1a melanoma. This study was not controlled, as placebo administration is unethical in this population and no highly effective treatment was available at the time of study design.

methods

This open-label, phase II study (NCT00942162, ‘PREDICT’) was conducted in 49 centers in Europe and the United States.

Patients >18 years of age with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–1, and histologically proven, unresectable, MAGE-A3-positive stage IIIB-C or IV-M1a cutaneous melanoma were included. Prior systemic cancer treatment was not permitted except adjuvant systemic immunomodulatory therapy. All patients received recMAGE-A3 + AS15 until melanoma progression, death, serious adverse event (SAE), or consent withdrawal. Details of safety assessments, ethics, MAGE-A3 assay, and treatment regimen are described in the supplementary Material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Identification of the GS was done centrally on RNA extracted from fresh tumor tissue using Affymetrix HG-U133.Plus 2.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) microarray gene chips on the same biopsy tissue used for determination of MAGE-A3 gene expression. The previously designed GS was used [1]. Each study centre remained blinded to GS results.

The primary objective was to evaluate the 1-year OS rate in patients with tumors presenting the predictive GS (GS+ population) and in patients without the GS (GS−population). The following end points were also evaluated in both populations: progression-free survival (PFS: time from study registration until disease progression or death), time-to-treatment failure (TTF: time from registration until the date of the last treatment administration), best clinical response, and duration of the response.

Evaluations were carried out at weeks 12, 23, 31, 54 and then every 6 months for the next 3 years using modified RECIST criteria [13]. All adverse events (AEs) occurring throughout the study till 30 days after the last product administration were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Version 3.0). The investigator assessed potential causal relationships between the study treatment and each AE.

Anti-MAGE-A3 IgG antibodies were measured at regular intervals using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; cut-off 27 EU/ml) [10]. An immune response to MAGE-A3 was defined as an antibody concentration ≥ assay cut-off value in initially seronegative patients, and as a twofold increase in concentration in initially seropositive patients.

A second exploratory GS (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) derived from an analytical protocol developed by Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium, was assessed with similar end points. Normalized patient sample hybridization was predicted as responder or non-responder by a Support Vector Machine decision rule [14] limited to a 33 ProbeSet classifier. Post hoc exploratory analyses were also carried out to assess the effect on OS of disease stage, number of treatment doses, center effect (excluding centers who recruited one patient), treatment with vemurafenib/dabrafenib or ipilimumab (drugs that became largely tested or available during the study) after progression, or BRAFV600 mutational status on stored tumor tissue.

Response was assessed on all patients who received at least one dose of treatment. The primary study objective was analyzed using a one-sample proportion exact binomial test. It was speculated that in the GS+ population, treatment with MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic would increase the 1 year-OS from 50% to 71%. With α and β risks set to 0.025 and 0.15, 53 GS+ patients should be recruited. Speculating that 50% of included patient tumors would be GS+ and 7% lost to follow-up rate, 115 should be recruited. One-year OS and other time-to-event secondary objectives (PFS, TTF) were displayed using non-parametric Kaplan–Meier estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Best clinical response, slow progressive disease (PD), and mixed response (MR, either a case of stable disease or of PD, defined in the supplementary Material, available at Annals of Oncology online) were also assessed. Immunogenicity to MAGE-A3 was tested on all patients who met eligibility criteria, and complied with protocol-defined procedures.

results

We present data available at the time of data lock point when all enrolled patients had been followed for at least 1 year, or until death (supplementary Material, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Of 370 tumors screened for MAGE-A3 expression, 332 had a valid test results (supplementary Figure S1 and Results, available at Annals of Oncology online). Of these, 173 (52.1%) were MAGE-A3-positive. A total of 127 MAGE-A3-positive patients were enrolled, of whom 123 received ≥1 dose of the study treatment. Only two tumors had an unknown GS status because of insufficient amplified material. There were 71 of 121 (58.7%) patients in the GS+ group.

The median age was 68 and 63 years in the GS+ and GS− populations, respectively. Fifty-nine percent of the GS+ population was female compared with 46% of the GS− population (Table 1). GS+ and GS− populations were balanced in terms of ECOG status, disease stage, lesion size, and type of prior therapy. Exposure to the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic was similar (median 6 doses) in the GS+ and GS− populations (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). The median follow-up time was 19.6 months (95% CI 14.3–24.0) in the GS+ population and 19.7 months (95% CI 15.9–24.5) in the GS− population.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristic of enrolled and treated subjects (total treated population)

| Parameter | GS+ (n = 71) | GS− (n = 50) | Totala (n = 123) | Kruit et al. (n = 36b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||

| Median (range) | 68 (28–91) | 63 (36–86) | 65 (28–91) | 69 (30–86) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 42 (59) | 23 (46) | 65 (53) | 22 (61) |

| Male | 29 (41) | 27 (54) | 58 (47) | 14 (39) |

| ECOG statusc, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 52 (73) | 40 (80) | 94 (76) | 35 (97) |

| 1 | 18 (25) | 10 (20) | 28 (23) | 1 (3) |

| Stage, n (%) | ||||

| IIIB | 11 (15) | 4 (8) | 16 (13) | NA |

| IIIC | 21 (30) | 19 (38) | 41 (33) | NA |

| IV-M1a | 39 (55) | 27 (54) | 66 (54) | NA |

| Lesion diameter, n (%) | ||||

| All <20 mm | 25 (35) | 14 (28) | 40 (33) | 14 (39) |

| All ≥20 mm | 24 (34) | 24 (48) | 48 (39) | — |

| Lesions < and ≥20 mm | 22 (31) | 12 (24) | 35 (29) | 22 (61) |

| Type of prior therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Interferon | 14 (20) | 16 (32) | 31 (25) | 11 (31) |

| Radiotherapy | 12 (17) | 5 (10) | 17 (14) | 2 (6) |

| Isolated limb perfusion | 5 (7) | 4 (8) | 9 (7) | 2 (6) |

| Cancer vaccine | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | — |

| Anti-CTLA-4-based therapy | 0 | 2 (4) | 2 (2) | — |

n, number of patients in each population.

n (%), number (percentage) of patients with the indicated characteristic.

aTotal include characteristics of two patients with unknown GS status.

bAS15 group.

cOne subject in the GS+ population had an ECOG score of 2.

One hundred and fifteen patients (68 GS+, 47 GS−) discontinued the study treatment, with the main reason being disease progression [53/71 (75%) in the GS+ population and 43/50 (86%) in the GS− population].

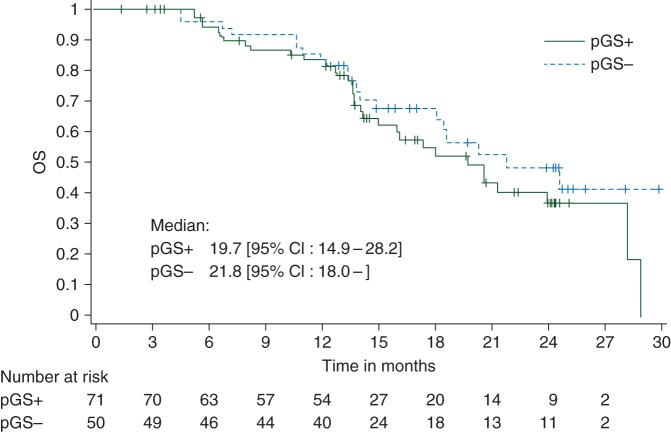

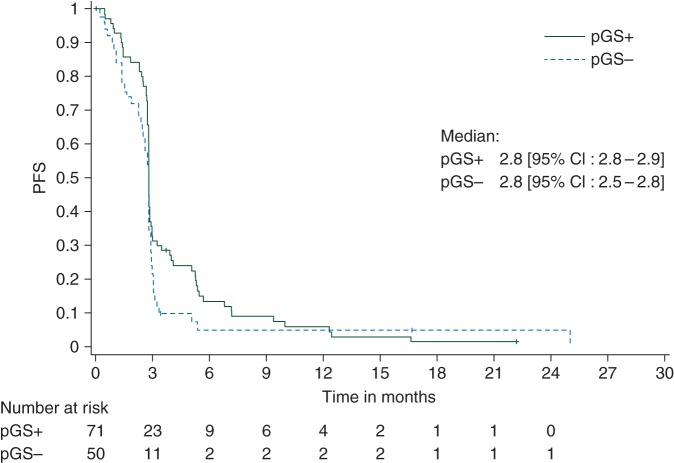

The 1-year OS rate in the GS+ population was 83.1% (95% CI 71.7–91.2, one-sided P value <0.0001) (Figure 1). However, a similar OS was observed in the GS− population (83.3%, 95% CI 69.8–92.5). The median OS was 19.7 months in the GS+ and 21.8 months in the GS− population. The median PFS was 2.8 months in GS+ and GS− populations, and the Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS were similar in both populations (Figure 2). The median TTF was 2.7 months (95% CI 2.4–5.4) in the GS+ population and 2.4 months (95% CI 2.3–2.6) in the GS− population. The number of patients with stable disease was 12 of 71 (16.9%) in the GS+ population and 4 of 50 (8.0%) in the GS− population (Table 2). In addition, 3 of 71 patients in the GS+ population (and none in the GS− population) had stable disease/partial response. Three objective responses were recorded: two partial responses in the GS+ population [median response duration 8.3 months (95% CI 6.9–9.7)] and one complete response (ongoing >4 years after study entry) in the GS− population. An MR was recorded in 16 of 71 (22.5%) and 9 of 50 (18.0%) of the GS+ and GS− populations, respectively.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve giving overall survival (OS) in the total treated population. pGS+, predictive gene signature-positive population; pGS−, predictive gene signature-negative population.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve giving progression-free survival (PFS) in the total treated population. pGS+, predictive gene signature-positive population; pGS−, predictive gene signature-negative population.

Table 2.

Clinical response and secondary clinical end points (total treated population)

| End point | GS+ (n = 71) | GS− (n = 50) | Totala (n = 123) | Kruit et al. (n = 35b) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best response, n (%) | Complete response (CR) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (8) |

| Partial response (PR) | 2 (3) | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | |

| Stable disease (SD) | 12 (17) | 4 (8) | 16 (13) | 5 (14) | |

| Stable disease/partial response (SD/PR) | 3 (4) | 0 | 3 (2) | Not defined | |

| Progressive disease | 51 (72) | 44 (88) | 97 (79) | 26 (72) | |

| Not evaluablec | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 4 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| Disease control, n (%) | CR + PR + SD + SD/PR | 17 (24) | 5 (10) | 22 (18) | 9 (25) |

n, number of patients in each population.

n (%), number (percentage) of patients with the indicated characteristic.

aTwo patients with unknown GS status.

bAS15 group.

cPatients in whom no or inadequate imaging/measurements were done after baseline, thus preventing conclusive evaluation of tumor response.

Disease control (sum of patients with complete/partial response/stable disease of minimum 12 weeks duration) was observed in 24% (17/71) of GS+ patients and 10% (5/50) GS− patients.

No differences in OS rate or any of the other end points were observed in populations with or without the exploratory GS (data not shown).

Post hoc analyses for OS are displayed in supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. The 1-year OS rate was 83.3% and 86.4% in the GS+ and GS− populations with stage III disease, and 82.9% and 80.8%, respectively, in patients with stage IV disease. No clinically relevant differences were observed in secondary clinical outcome measures between patients with stage III or IV disease at enrolment (data not shown). In patients who received at least 9 doses of study treatment, the 1-year OS rate was 93.8% in the GS+ and 100% in the GS− population. Of 75 tumors who could be tested for B-RAF mutation status, 17 of 41 (41.5%) of B-RAF-mutation-positive tumors were from patients belonging to the GS+ population and 17 of 34 (50.0%) were from patients belonging to the GS− population. The 1-year OS rate was 91.3% in 23 GS+ patients who received vemurafenib/dabrafenib or ipilimumab after study discontinuation, versus 78.6% in GS+ patients who did not receive any of these drugs. In the GS− population, the 1-year OS rate was 86.4% in those who did, and 80.8% in those who did not receive vemurafenib/dabrafenib or ipilimumab after study discontinuation. The use of vemurafenib/dabrafenib or ipilimumab appeared to extend OS in GS+ and GS− populations until around month 12, after which OS rates decreased similarly in vemurafenib/dabrafenib or ipilimumab-treated and untreated populations (data not shown).

There were few grade 3 treatment-related AE and no treatment-related grade 4–5 AE (Table 3). Fifty-three deaths had occurred, none considered as treatment-related. Fifty patients died due to disease progression and three due to fatal SAEs that occurred >1 year after the last treatment dose received (supplementary Safety Results, available at Annals of Oncology online). Seventeen patients reported 21 SAEs, of which one (Guillain–Barré syndrome 8 days post-dose-1) was considered possibly treatment-related. Three additional potential immune-mediated diseases were reported: autoimmune colitis (SAE) 225 days post-dose-6; autoimmune hemolytic anemia (non-serious) 13 days post-dose-15; and worsening of pre-existing vitiligo (non-serious) 21 days post-dose-10 (the best overall response for this patient was stable disease). All except the case of colitis were considered possibly treatment-related.

Table 3.

Treatment-related adverse events from dose 1 until the data lock point and reported by at least four patients, by maximum CTCAE grade (total treated cohort)

|

n = 123 (GS+/GS−/GS unknown) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1, n (%) | Grade 2, n (%) | Grade 3, n (%) | |

| Any event | 66 (54%) | 21 (17%) | 11 (9%) |

| Injection site | 60 (49%) | 13 (11%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Pyrexia/body temperature increased | 35 (28%) | 4 (3%) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 15 (12%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (3%) |

| Chills | 19 (15%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Asthenia | 8 (7%) | 4 (3%) | 2 (2%) |

| Influenza-like illness | 11 (9%) | 3 (2%) | 0 |

| Nausea | 8 (7%) | 4 (3%) | 0 |

| Myalgia | 5 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (2%) |

| Pain in extremity | 4 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 6 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 0 |

| Constipation | 7 (6%) | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 6 (5%) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 3 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Lacrimation increased | 4 (3%) | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 3 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Pain | 4 (3%) | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 3 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Rash | 4 (3%) | 0 | 0 |

n, number of patients in each population.

n/%, number/percentage of patients reporting the adverse event at least once.

Four GS+ and three GS− patients were seropositive for anti-MAGE-A3 IgG antibodies at baseline. All patients had an immune response by week 12 (after 6 doses) (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The anti-MAGE-A3 IgG geometric mean concentration (GMC) after two doses of the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic was 728.7 EU/ml in the GS+ population and 1385.7 EU/ml in the GS− population. After 6 doses, the GMC was >5600 EU/ml in both populations.

discussion

We explored prospectively the 84-gene GS previously identified from a retrospective evaluation of 56 patients with stage III–IV-M1a melanoma after treatment with MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic [1]. While a survival advantage was previously shown for a MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic-treated GS+ population, using the same treatment in a similar population, we observed no difference between GS+ and GS− populations in clinical outcomes, including a similar 1-year OS rate and humoral immune responses. Our study highlights the difficulties in predicting the clinical results that can be achieved by immunotherapy.

The results do not seem to be due to lower efficacy of MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic in this trial. Considering patients who did not receive additional vemurafenib/dabrafenib or ipilimumab treatment, we observed a similar OS rate (78.6% in the GS+ population) as that reported in another study of the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic in patients with metastatic melanoma (median 1-year OS rate 74%), which included fewer stage IV patients (30.6% versus 54.5%) [8].

Post hoc analyses suggested that neither disease stage, study centre, nor cumulative number of treatment doses influenced the 1-year OS rate in the GS+ population. Moreover, treatment with vemurafenib/dabrafenib or ipilimumab tended to prolong the OS rate during the first year in both the GS+ and GS− populations. The 1-year OS rate in the GS+ group that did not receive vemurafenib/dabrafenib or ipilimumab was also higher than what might be expected from historical data, but was similar to observations by Kruit et al. [8]. The percentage of invalid samples was within the expected range (unpublished).

Unexpectedly, we observed a lower rate of objective clinical response compared with previous studies of the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic in patients with metastatic melanoma, although the disease control rate was within the previously reported range [6, 8, 9]. A similar proportion of patients achieved disease control in the GS+ population in this study (24% of GS+ and 10% of GS− patients) compared with Kruit et al. (25% and 14%, respectively) [8]. It is increasingly recognized that clinical responses to cancer immunotherapeutic treatments may have a delayed onset [8, 15, 16], although the number of doses and time needed to observe a response is not defined. The low number of clinical responders may have been due to the high rate of early treatment discontinuation in our study.

Heterogeneity of the tumor microenvironment of different lesions for the same patient may pose an issue for the use of biomarkers to predict response. Indeed, inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity has been reported in other biomarkers such as somatic mutations [17, 18]. The same issue may have arisen in our study, which may have resulted in patients having heterogeneous GS. The consistency of GS expression between different lesions from the same patient is currently being investigated (www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT00896480). This might be a limitation for the application of biomarkers in the advanced disease setting, while potentially less of a concern in the adjuvant setting where GS determination would be done on a single primary lesion in each patient.

Limitations of this study also include the absence of a control group. Moreover, the primary end point of this study was a fixed 1-year OS time-point. A high number of patients were still alive at the 1-year time-point and beyond, and were therefore censored for the OS analysis. However, a repeated analysis after 2 years of follow-up (as planned per protocol) did not change the interpretation of the data (data not shown). The study may have been subject to biases when determining the 1-year OS rate because OS was calculated from the date of study entry rather than from the date of diagnosis of metastatic disease; thus, patients with rapidly progressive melanoma and eligible for the study may have been preferentially selected for trials, including ipilimumab or vemurafenib as first treatment option; in particular toward the second half of the study when these products became widely tested. Thus, we could have included more patients with less aggressive disease.

MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic was generally well tolerated with few grade 3 or 4 reactions, and the safety profile was consistent with previous reports [6, 8, 9].

In conclusion, in this prospective phase II trial of patients with MAGE-A3-positive unresectable stage IIIB-C/IV-M1a melanoma, treatment with the MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic demonstrated a 1-year OS rate of 83.5%. Unexpectedly, GS patients had a similar 1-year OS as GS+ patients. Investigation of the potential value of a GS to predict clinical benefit to adjuvant MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic treatment is ongoing in another study of melanoma (NCT00796445).

funding

This work was supported by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA that was involved in all stages of the study conduct and analysis. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA also funded all costs associated with the development and the publishing of the present manuscript. All authors had full access to the data. The corresponding author was responsible for submission of the publication. No grant number was attached to this study.

disclosure

PS reports receiving personal grant/fees, and/or other support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche-Genetech, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, GSK, and Novartis. RG reports receiving grants/fees, and/or other support, and/or non-financial support from GSK, LEO, Roche Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, MSD, Celgene, Lilly, EISAI, Vical, Philogen, Pfizer, Merck Serono, Almirall Hermal, Amgen, and Janssen, for activities outside the scope of the submitted work. PAA reports a consultancy/advisory role for BMS, Roche-Genentech, MSD, GSK, Ventana, Novartis, and Amgen; research funds from BMS, Roche-Genentech, and Ventana; and honoraria from BMS, Roche-Genentech, and GSK. MM reports receiving an institutional grant from GSK for conduct of the study; advisory Boards and paid lectures by GSK, Roche, and Bristol Myer Squibb; research grants from Bristol Myer Squibb. J-JG reports receiving fees and/or grants from GSK for activities outside the scope of the submitted work, acting as advisor and speaker for GSK. BD reports receiving fees and/or grants from GSK for activities outside the scope of the submitted work. MR reports receiving fees from Merck Inc., Genomic Health, and GSK for activities outside the scope of the submitted work. JW reports receiving honoraria for participation on advisory boards for GSK, Roche, Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Amgen, and Genentech. AH reports receiving consultancy fees from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, GSK, MedImmune, MelaSciences, Merck Serono, MSD/Merck, Novartis, Oncosec, Roche Pharma, honoraria from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, GSK, MedImmune, MelaSciences, Merck Serono, MSD/Merck, Novartis, Oncosec, Roche Pharma, and clinical trial grants from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, GSK, MelaSciences, Merck Serono, MSD/Merck, Novartis, Oncosec, and Roche Pharma. PR reports receiving fees and other from GSK, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Roche for activities outside the scope of the submitted work. LM received an institutional fee from GSK for conduct of this study. AE received honoraria and consulting fees from Roche, BMS, MSD, Biotest, Galderma. CVA, IV, OP, VGB, and PT are employees of GSK group of companies at the time of the study conduct. VGB and PT have stock/stock options of GSK group of companies. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study. They also acknowledge the investigators and their clinical teams for their contribution to the study and their support and care of patients, in particular Vanna Chiarion-Sileni, Dirk Schadendorf, Bernard Guillot, Lev Demidov, Jochen Utikal, Erwin Schultz, Eric Whitman, Claus Garbe, Alexander Roesch, Patrick Terheyden, Cord Sunderkoetter, Jens Ulrich, Anja Gesierich, Rudolf Herbst, Cornelia Mauch, Edgar Dippel, Christine Bayerl, Susana Puig Sarda, Pascal Joly, Sophie Dalac, François Aubin, Henry Redmond, Wojciech Rogowski, Thomas Gajewski, Gerald Linette, Scott Pruitt, Omid Hamid, Takami Sato, Bartosz Chmielowski, John Nemunaitis, Christine Longvert, Véronique Clerisse, Sina Krengel, and Riccardo Danielli. The authors thank the global and regional clinical operations and safety teams of GSK Vaccines for their contribution to the study, the scientific writer for clinical protocol and clinical report writing and the team of statisticians, in particular Corinne Jamoul and Bart Spiessens, at GSK for the statistical analysis. The authors would like to thank also Channa Debruyne and Jamila Louahed for their contribution in the study. Medical writing services were provided by Dr Joanne Wolter on behalf of GSK. Publication coordination and editorial assistance was provided by Dr Nicolas Matuszak (XPE Pharma & Science) on behalf of GSK.

references

- 1.Ulloa-Montoya F, Louahed J, Dizier B et al. Predictive gene signature in MAGE-A3 antigen-specific cancer immunotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 2388–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong S-J et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 6199–6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eggermont AMM, Spatz A, Robert C. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet 2014; 383: 816–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brasseur F, Rimoldi D, Liénard D et al. Expression of MAGE genes in primary and metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Int J Cancer 1995; 63: 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P. T cell defined tumor antigens. Curr Opin Immunol 1997; 9: 684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruit WHJ, van Ojik HH, Brichard VG et al. Phase 1/2 study of subcutaneous and intradermal immunization with a recombinant MAGE-3 protein in patients with detectable metastatic melanoma. Int J Cancer 2005; 117: 596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cluff CW. Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) as an adjuvant for anti-cancer vaccines: clinical results. Adv Exp Med Biol 2010; 667: 111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruit WHJ, Suciu S, Dreno B et al. Selection of immunostimulant AS15 for active immunization with MAGE-A3 protein: results of a randomized Phase II study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Melanoma Group in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 2413–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchand M, Punt CJA, Aamdal S et al. Immunisation of metastatic cancer patients with MAGE-3 protein combined with adjuvant SBAS-2: a clinical report. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39: 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vantomme V, Dantinne C, Amrani N et al. Immunologic analysis of a phase I/II study of vaccination with MAGE-3 protein combined with the AS02B adjuvant in patients with MAGE-3-positive tumors. J Immunother 2004; 27: 124–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atanackovic D, Altorki NK, Stockert E et al. Vaccine-induced CD4+ T cell responses to MAGE-3 protein in lung cancer patients. J Immunol 2004; 172: 3289–3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vansteenkiste J, Cho B, Vanakesa T et al. MAGRIT, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase III study to assess the efficacy of the recMAGE-A3 + AS15 cancer immunotherapeutic as adjuvant therapy in patients with resected MAGE-A3-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol 2014; 25(25 Suppl 4): iv409–iv416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boser B, Guyon I, Vapnik V. A training algorithm for optimal margin classifiers. In Fifth Annual Workshop on Computational Learning Theory ACM, Pittsburgh, 1992. pp. 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burch PA, Croghan GA, Gastineau DA et al. Immunotherapy (APC8015, Provenge) targeting prostatic acid phosphatase can induce durable remission of metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer: a Phase 2 trial. Prostate 2004; 60: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher R, Pusztai L, Swanton C. Cancer heterogeneity: implications for targeted therapeutics. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jamal-Hanjani M, Thanopoulou E, Peggs KS et al. Tumour heterogeneity and immune-modulation. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2013; 13: 497–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.