Significance

The evolutionary hypothesis for T-cell antigen receptor–peptide major histocompatibility complex (TCR–pMHC) interaction posits the existence of germ-line–encoded rules by which the TCR is biased toward recognition of the MHC. Understanding these rules is important for our knowledge of how to manipulate this important interaction at the center of adaptive immunity. In this study, we highlight the flexibility of thymic selection as well as the existence of these rules by generating knockin mutant MHC mice and extensively studying the TCR repertoires of T cells selected on the mutant MHC molecules. Identifying novel TCR subfamilies that are most evolutionarily conserved to recognize specific areas of the MHC is the first step in advancing our knowledge of this central interaction.

Keywords: T-cell receptor, MHC, evolution, mutation, variable region

Abstract

The interaction of αβ T-cell antigen receptors (TCRs) with peptides bound to MHC molecules lies at the center of adaptive immunity. Whether TCRs have evolved to react with MHC or, instead, processes in the thymus involving coreceptors and other molecules select MHC-specific TCRs de novo from a random repertoire is a longstanding immunological question. Here, using nuclease-targeted mutagenesis, we address this question in vivo by generating three independent lines of knockin mice with single-amino acid mutations of conserved class II MHC amino acids that often are involved in interactions with the germ-line–encoded portions of TCRs. Although the TCR repertoire generated in these mutants is similar in size and diversity to that in WT mice, the evolutionary bias of TCRs for MHC is suggested by a shift and preferential use of some TCR subfamilies over others in mice expressing the mutant class II MHCs. Furthermore, T cells educated on these mutant MHC molecules are alloreactive to each other and to WT cells, and vice versa, suggesting strong functional differences among these repertoires. Taken together, these results highlight both the flexibility of thymic selection and the evolutionary bias of TCRs for MHC.

The genes for immunoglobulins (Igs), αβ T-cell receptors (TCRs), and antigen-presenting MHC proteins appeared at least 450 million years ago in the cartilaginous fish and are present in all modern vertebrates (1–3). The more primitive hagfish and lampreys lack these genes and have an adaptive immune system comprised of unrelated proteins (4). The main ligands for αβ TCRs are short peptides derived from self and foreign proteins, captured in a specialized groove of MHC class I (MHCI) and class II (MHCII) molecules and presented to T cells (5, 6). Functional Igs and TCRs are created by very similar recombination mechanisms involving fusion of V, J, and sometimes D gene segments with additional variations at the junctions to create an enormous potential repertoire of Igs and TCRs, suggesting a common, unknown evolutionary origin for these loci.

These observations have raised several unanswered questions. For example,why did a separate TCR-rearranging gene system develop for lymphocytes recognizing peptide–MHC ligands? How did the extraordinarily polymorphic MHC genes stay functionally connected to TCR genes throughout 450 million years of evolution? One long-standing hypothesis has been that certain features of TCRs and MHC molecules are evolutionarily conserved to promote their interaction (7–10). Like Igs, the antigen-recognition portions of TCRs are partially encoded in the complementary determining region (CDR) CDR1 and CDR2 loops of germ-line TCR Vα (TRAV) and Vβ (TRBV) genes and are partially generated by somatic recombination processes that form the CDR3 loops. This initial repertoire is culled dramatically during T-cell development in the thymus. First, only those T cells whose TCRs have at least some minimal affinity for the self-peptide–MHC molecules expressed in the thymus are positively selected for further development (11, 12). The T cells in this population whose TCRs have too high an affinity for these self-peptide–MHC molecules are eliminated by an apoptotic mechanism termed “negative selection” (13, 14). The remaining T cells go on to mature and form the peripheral T-cell repertoire.

The effect of positive and negative thymic selection on limiting the T-cell repertoire has made it difficult to test directly whether germ-line features of TCRs and MHC molecules have been conserved to promote their interaction. However, some data consistent with this notion have accumulated over the past several decades through sequencing, X-ray crystallographic, mutational, and developmental studies. For example, random examination of mouse T cells before positive selection showed a high frequency of MHC-reactive cells (15–17). In mice constructed to allow positive selection but incomplete negative selection, an even higher frequency of generically MHC-reactive T cells was observed (18). Structural and sequencing studies of MHC molecules have shown that the great majority of their polymorphisms are within the peptide-binding groove, not on the tops of the MHC α- and β-chain helices that interact with TCRs (Table 1). The CDR1 and CDR2 loops of TCRs are much less variable in length than those of Igs (19). In the dozens of structures of peptide–MHC/TCR complexes that have been solved, a diagonal orientation of the TCR is nearly always seen. This orientation usually causes the somatically generated CDR3s to be focused on the peptide and the germ-line–encoded CDR1 or CDR2 amino acids, especially those of CDR2, to be docked on the conserved portions of the MHC helices (9). Mutation of these TCR amino acids impairs T-cell recognition of the ligand and affects thymic development of the T cells in vivo (8, 20–22). Some of these germ-line TCR amino acids can be traced back to the TCRs of fish, and, despite their overall weak sequence homology, substitution of fish V segments for the mouse V segments preserves antigen recognition of the mouse peptide–MHC complex (23). Finally, although RAG-mediated rearrangement makes the CDR3 more diverse, the CDR1 and CDR2 loops in TCRs, unlike those in Igs, do not undergo antigen-selected somatic mutation; thus they keep their germ-line sequence and antigen-driven responses throughout development, suggesting a conserved function (24, 25).

Table 1.

Alignment of I-A haplotype helix residues

|

The solvent-exposed residues of I-Aα or I-Aβ mutated in this study are numbered.

Consensus sequence.

Differences from consensus sequence.

Another model for the MHC restriction of TCRs has been put forth. According to the selection model, MHC restriction is not intrinsic to TCR structure but imposed is by the CD4 and CD8 coreceptors that promote signaling by delivering the tyrosine kinase Lck to TCR–MHC complexes through coreceptor binding to MHC during positive selection (26).

In the current study we assessed the importance of several MHCII conserved docking sites for TCRs by introducing specific point mutations into mouse I-Ab MHCII α or β genes. In vitro these mutations had little effect on the collection of self-peptides bound by the mutant I-Ab but often disrupted the recognition of peptide plus MHC by T cells specific for a variety of foreign or self-peptides. In vivo, mice carrying these MHC point mutations developed TCR repertoires that were similar in size to those of WT mice but with altered TRAV or TRBV gene use. Furthermore, in vitro in mixed lymphocyte reactions, T cells from each of the WT and mutant mice responded strongly to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) from the other mice but not to their own cells. We discuss these results in relation to the current ideas and data about the role of evolution vs. somatic selection in framing the T-cell repertoire.

Results

Mutations of the I-Ab Conserved Amino Acids Affect the Presentation of Foreign Peptides to Antigen-Specific T-Cell Hybridomas.

Although MHC genes are extremely polymorphic, the amino acids on the α and β helices of MHCII that are frequently engaged by the TCR CDR1 and CDR2 loops are usually conserved, sometimes even across species (9). Ten of these amino acids tend to be almost monomorphic in the mouse I-A alleles found in the majority of laboratory strains (Table 1). A number are conserved as well in mouse I-E molecules and in the MHCII alleles of humans and other species (Table S1). These residues are located on the tops of the MHCII α-helices, in positions where they are less likely to affect peptide binding and are more likely to affect interactions of the MHCII protein with TCRs (Fig. 1A). Thus, we hypothesize that these amino acids may have been conserved during evolution to promote interactions with TCRs.

Table S1.

Species comparison of conserved MHC helix residues

|

The highlighted solvent-exposed residues of I-Aα (cyan) or I-Aβ (magenta) mutated in this study are conserved to varying extents.

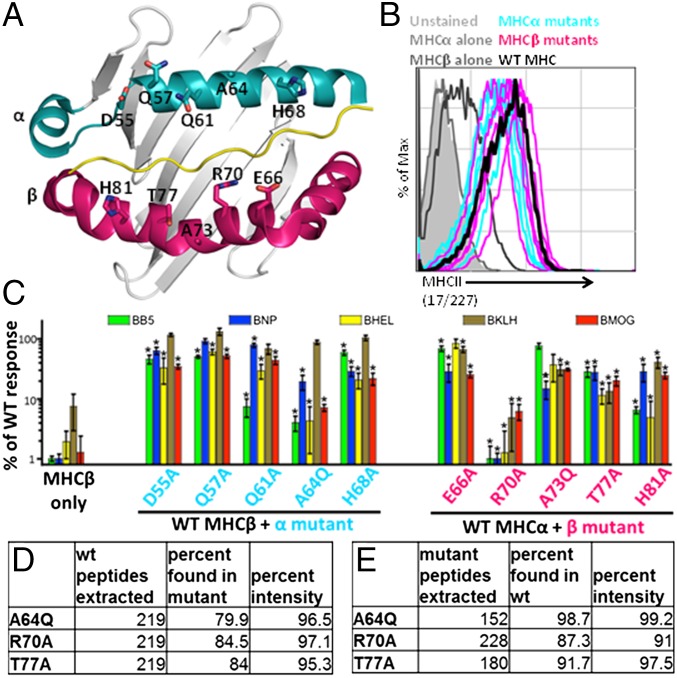

Fig. 1.

Screening and selection of I-Ab mutants that affect mature T-cell responses. The WT and mutant MHC molecules are expressed at similar levels in cell lines and present peptides. (A) The solvent-exposed residues that were targeted for mutations are indicated for the α- (cyan) and β- (magenta) chains of H-2 I-Ab. Residues were chosen for mutational analysis based on their conservation between H2 molecules and their predicted interaction with TCRs. (B) M12.C3 cells expressing the mutant constructs were stained with the 17/227 mAb, and the expression of I-Ab was determined by flow cytometry. (C) Hybridomas were stimulated with cognate antigen presented by APCs expressing WT or mutant I-Ab. Activation was determined by flow cytometry and was defined as the MFI of CD69. The ability of each mutant to stimulate the hybridomas is displayed after normalization to WT responses. Data are representative of three or four biological replicates per group; *P < 0.05 by a one-sample t test with a true value of 100. (D) Peptides were eluted from WT I-Ab and were analyzed by MS. Peptides with identical HPLC retention times that were present in three separate WT samples were identified. Data indicate the percentage of peptides that were also identified in duplicate runs isolated from βT77A, βR70A, and αA64Q cells. (E) Peptides present in duplicate runs from each of the mutants were identified and compared with WT. Data are representative of multiple MS and MS-MS runs.

To study the relative importance of these amino acids in TCR recognition of peptide–I-Ab complexes, we mutated each of these 10 residues separately. Nonalanine amino acids were replaced with alanine (A), and alanines were replaced with glutamine (Q). Alanine was chosen as a neutral, frequently used mutational replacement, and glutamine was chosen because it is already present at the other positions on the helix and thus would not greatly alter the chemistry at the surface of the protein. Genes encoding either the mutant I-Ab α- or β-chain, paired with the corresponding WT I-Ab α or β gene, were transduced into an MHCII-deficient B-cell lymphoma, M12.C3 (27, 28), to create APCs expressing the mutant I-Ab molecules. M12.C3 cells, derived from an H-2d mouse, lack an I-Ad β-chain but express a functional I-Ad α-chain from the original M12 BALB/c lymphoma. This I-Ad α-chain can sometimes pair with some other introduced I-A β-chains, including that of I-Ab. For this reason we prepared M12.C3 cells transduced with only the WT I-Ab β-chain to control for the possible activity of the I-Ad/b mixed molecule. M12.C3 cells transduced with both of the WT I-Ab genes served as a positive control, and M12.C3 cells with only the WT I-Ab α-gene were also used as a negative control.

All the M12.C3 transductants were cloned at limiting dilution, and surface expression of I-Ab was confirmed by flow cytometry. Because each mutation might have affected the epitopes recognized by individual mAb differently, we stained the cells using a variety of anti–I-Ab–specific mAbs. Fig. 1B shows data for the 227 mAb, the antibody least affected by the mutations. With this mAb, the WT and mutant I-Ab cells all stained with a mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) 10- to 30-fold higher than that of the negative controls. The MFI for the cells expressing the I-Ab/d mixed molecule was much lower. Thus, all the mutants were expressed at about the same level.

Next, we devised a system in which the responses of many different T cells to antigen bound to the mutant MHCIIs could be assessed simultaneously. C57BL/6 mice were immunized separately with five different antigens (Table 2). Seven days later, T cells from the draining lymph nodes of the immunized mice were restimulated with their cognate antigens, expanded in vitro, and fused in bulk to the TCR αβ− BW5147 thymoma cell line to create T-cell hybridomas. The preparations were named for their target MHC-II allele, I-Ab, and antigen (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bulk hybridomas and their immunizing antigen

| Bulk hybridoma | Protein or peptide antigen | Sequence |

| BB5 | Vaccinia B5 peptide | FTCDQGYHSSDPNAV |

| BNP | LCMV NP peptide | SGEGWPYIACRTSIVGRA |

| BHEL | Hen egg lysozyme | Whole protein |

| BKLH | Keyhole limpet hemocyanin | Whole protein |

| BMOG | Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide | MEVGWYRSPFSRWHLYRNGK |

Bulk hybridomas are named for the haplotype of the mouse (H-2b) and the immunized antigen shown in this table.

The bulk T-cell hybridoma preparations were cultured with M12.C3 cells expressing WT I-Ab, each of the mutant I-Abs, or WT I-Ad/b with or without the immunizing antigen. Activation of the T-cell hybridomas was assessed by up-regulation of CD69 on the cells, as measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 1C). On average, about 50-fold more of the T-cell hybridomas in the bulk populations responded to their immunizing antigen plus M12.C3 cells bearing WTαβ I-Ab than to control M12.C3 cells with only I-Ab WTβ. Nearly all the responses of the peptide or hen egg lysozyme (HEL)-specific bulk T-cell hybridomas were significantly reduced when the mutant APCs were used instead of WT APCs, again with their immunizing antigen. The responses by bulk keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH)-specific T-cell hybridomas were also reduced 1.5- to 16-fold in various β-chain mutants but not in α-chain mutants, perhaps because the large KLH protein may have many potential I-Ab–binding epitopes, and therefore, as group, T cells specific for KLH may be less sensitive to any one MHCII mutation. Consistent with this relative lack of sensitivity to α-chain mutants, some of the bulk KLH-specific cells were also cross-reactive to KLH presented by APCs bearing the mixed I-A molecule in which the I-Ad α-chain replaced the I-Ab α-chain.

These results confirmed and extended our previous studies (29) because they showed that the conserved amino acids on the MHCII helices are not required for MHCII surface expression. However, in agreement with previous work, they are often important for TCR docking during CD4+ T-cell responses, leaving open the possibility that their conservation might be required to ensure germ-line–encoded favorable MHCII docking sites for TCRs.

We selected mutants from this group for in vivo studies to find out if they also affected T-cell thymic development. We considered the four mutations that most consistently inhibited T-cell activation: A64Q on the α-chain and R70A, T77A, and H81A on the β-chain. αA64 is invariant in mouse and human MHCII and creates a docking “cup” for TCR Vβs that contain a tyrosine (Y) at position 48 of CDR2 (9). βT77 and βH81 are adjacent on the I-Ab β-chain α-helix (Fig. 1A). βT77 is invariant in common mouse I-A and I-E alleles and in human HLA-DR and HLA-DQ alleles. In TCR/MHC structures, βT77 and βH81 are often contacted by the TRAV CDR1 loop (9). However, the highly conserved βH81 has been implicated in the activity of mouse H-2DM and human HLA-DM, the proteins that catalyze endosomal peptide loading into MHC (30), and in TCR/MHC structures often makes a surface-exposed H-bond to the peptide backbone. Therefore we decided not to mutate this amino acid in our experiments. βR70 is nearly monomorphic in all mouse I-A alleles (Table 1) but is not conserved in mouse I-E alleles or in the MHCII alleles of other species. In nearly all published TCR/I-A structures it lies in the central region of the TCR footprint interacting with the TCR CDR3s and therefore might be expected to influence somatic CDR3 selection during thymic selection but perhaps not to have as strong an influence on germ-line Vα and Vβ use. Therefore we choose αA64Q and βT77A as the primary mutations to test our hypothesis and βR70A as a potential control.

Effects of the βT77A, βR70A, and αA64Q Mutations on the Peptides Bound to I-Ab.

Before proceeding to in vivo experiments with these mutants, we considered the possibility that, despite the predicted lack of a direct role for these I-Ab amino acids in peptide binding, they might indirectly change the spectrum of I-Ab–presented self-peptides. Such changes would confound our experiments because positive selection involves reaction of the TCRs with both MHC and peptide, and we intended to examine the effects of MHC mutations independent of changes in the bound peptide. To determine whether the MHCII mutations we created altered the spectrum of bound peptides, we compared the repertoire of peptides bound to WT I-Ab with those of the three I-Ab mutants expressed in our M12.C3 transfectants. One caveat of these experiments is the thymus presents a different set of peptides in a cathepsin L-dependent fashion (31) and thus may behave differently than the transfected M12.C3 cells.

The WT and mutant I-Ab proteins were immunoprecipitated from lysates of the transduced M12.C3 cells. Peptides were eluted from these preparations and subjected to MS or MS-MS analysis as previously reported (32) and as described in Materials and Methods. A preliminary MS-MS analysis of the peptides isolated from WT and mutant I-Ab showed that they had I-Ab–binding motifs (Table S2) (33, 34). This finding served to validate our method of peptide isolation and suggested that the I-Ab mutations did not affect the I-Ab peptide-binding motif.

Table S2.

Ms-Ms peptides eluted from I-Ab contain the known binding motif

|

List of peptides identified by Ms-Ms in trial runs eluted from WT and mutant I-Ab molecules. The known I-Ab binding motif is shown to be present in these peptides, and most of these peptides appear as nested sets.

To compare the peptides bound to WT vs. mutant I-Ab proteins, immunoprecipitations and elutions for each sample were performed and analyzed with duplicate runs by MS. Limited MS-MS again confirmed the presence of the I-Ab–binding motif in the peptides. A list of the peptides with identical HPLC retention times and calculated masses that were present in three separate WT I-Ab samples was compared with those in duplicate runs of mutant samples (Fig. 1D). Nearly all the total peptide intensities found in the WT I-Ab samples were also identified in all the mutant I-Ab samples. To determine if unique peptides appeared only in the mutants, we first created a list of peptides that were found in duplicate MS runs of the same mutant sample. Any peptide in this list that also appeared in any of the three WT samples was also called present. Once again, most of the peptides and nearly all the intensity from the mutant samples were found in the WT runs (Fig. 1E). Less stringent criteria, e.g., requiring that a peptide be present in only two of the three WT or mutant I-Ab samples, identified even more peptides shared among the samples. This analysis does not identify peptides belonging to nested sets; therefore the similarity between samples may be underestimated, because differently trimmed peptides were considered to be different by our analyses, although the peptide they present to T cells is identical. Taken together, these experiments support the notion that βT77A, βR70A, and αA64Q MHC mutations do not notably alter the repertoire of self-peptides bound to I-Ab. We therefore proceeded to test the effects of these mutations on thymic selection in vivo.

Creation of Mice Bearing the βT77A, βR70A, and αA64Q Mutations.

We produced mice expressing only the WT or mutant forms of I-Ab. To ensure that the mutant and WT genes were expressed on the proper cells at the appropriate levels, we changed the coding sequences of the genes in situ, using zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) technology to generate knockin point mutations directly in fertilized C57BL/six eggs (35, 36).

Custom ZFNs were designed (Sigma Aldrich) for both H2-Ab1 and H2-Ab2, the genes that encode the α- and β-chains of the only MHCII molecule expressed in C57BL/6N mice. To reduce off-target effects, the ZFNs were designed to ensure that no other region of the mouse genome had fewer than five DNA base mismatches to the sequence targeted by the ZFNs. A template for homology-directed repair (HDR) was used to introduce our mutations into mice. This template had four components: (i) the mutation of interest; (ii) a silent mutation to create a new restriction enzyme site for screening of progeny; (iii) a silent mutation to disrupt the ZFN binding so that a subsequent insertion or deletion event caused by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) would not occur after our mutation of interest had been introduced; and (iv) roughly 1,000 bp of homology on either side of the target of the ZFN (Fig. 2A) (37).

Fig. 2.

Generation of MHCII mutant mice and characterization of the effects of mutation on thymic selection. (A) The schematic depicts the ZFN-targeting strategy used to generate MHC mutant mice. The DNA for HDR was designed to target exon 3 of either H2-AB (R70A, T77A) or H2-AA (A64Q); the positions of screening primers are indicated. The structure of the DNA for HDR included 1,000 bp of homology flanking at either end the ZFN recognition site. Mutations in H2-AB are indicated in red, and mutations in H2-AA are shown in teal. The restriction sites introduced to allow screening are indicated in green. The locations of ZFN recognition sites are also indicated; these sites were disrupted by the introduction of a silent mutation in the vector. (B) Splenocytes were stained for MHCII and markers of lymphocyte lineages and were analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms depict the level of expression of MHCII on TCRβ− cells in βR70A and βT77A (magenta traces), αA64Q (teal trace), and WT (dark gray shaded area) mice. (C and D) Thymocyte composition is shown for WT, βR70A and βT77A (C), and for WT and αA64Q mice (D) as determined by expression of CD4 and CD8. Thymocytes undergoing selection are identified by the expression of CD5 and CD69. (E) Frequency of mature SP4 and SP8 thymocytes in the indicated strains. (F) Frequency of thymocytes undergoing selection in the different mice. Data in C–F are representative of three or four independent experiments containing 7–10 mice per group. Error bars represent SEM; *P < 0.05.

DNA from the resultant mice was analyzed to identify chromosomes bearing the desired mutation. The method was surprisingly robust, with NHEJ events identified in nearly all the mice and at least one chromosome with the correct mutation found in >10% of the mice overall. Mutant mice were crossed to WT mice and then intercrossed to create mice homozygous for each of the three mutations. All mice showed equivalent levels of I-Ab cell-surface expression on peripheral cells (Fig. 2B).

Phenotypic Analysis of Thymic T Cells in the Mutant Mice.

To determine whether any of our MHC mutations affected the development of CD4+ T cells, the thymus of each mouse strain was analyzed by flow cytometry. No significant difference in the number of thymocytes in the double-negative (DN), double-positive (DP), and single-positive (SP) populations was detected between the thymi of the mutant mice vs. WT mice (Fig. 2 C–E). Analysis of CD5 and CD69 expression, markers of DP thymocyte activation during positive selection, showed that the size of the expressing population was not changed in the βR70A and βT77A mutant mice but was significantly reduced in the αA64Q mutant mice (Fig. 2 C, D, and F), suggesting that at least the αA64Q mutation reduced positive selection and MHCII reaction by TCRs.

Effect of the βT77A and βR70A Mutations on the Use of TRAVs.

We next examined the TCR repertoire of peripheral T cells selected in WT and mutated mice. Because the germ-line portions of the TCRs interacting with I-Ab βT77 were predicted to be those of TRAV CDR1s, we predicted that the TRAVs used in the mutant mice would be more affected by these mutations than the TRBVs. Therefore, we compared TRAV use in the βT77A mice with that in the WT mice, using the βR70A mutant mice as a possible control, because this amino acid most often interacts with randomly generated CDR3 regions rather than the germ-line encoded DR1 and CDR2 regions. Anti-TRAV staining with the four available anti-TRAV mAbs (TRAV14, TRAV9, TRAV12, and TRAV4) revealed a significant reduction in TRAV14 use in the mutant mice (Fig. 3 A–C). As expected, this reduction was seen only in CD4 T cells, not in CD8 T cells. This TRAV14 shift was the first indication of an altered TCR repertoire in the T77A mice.

Fig. 3.

Differential use of TRAV families and subfamilies in T77A mutant mice. (A) Representative analysis via flow cytometry of TRAV14 expression in spleen CD4+ T cells from WT, βR70A, or βT77A mice. (B and C) Frequency of TRAV14+ cells in CD8+ (B) and CD4+ (C) T cells in the spleen of the indicated mice. Data are representative of three or four independent experiments containing 7–10 mice per group. Error bars indicate SEM. (C) Next-generation sequencing of the entire TCRα repertoire expressed in naive CD4+ T cells sorted from the spleen of WT, βR70A, or βT77A mice. (D) Frequencies indicate the proportion of any given TRAV family out of all valid sequences. (E and F) Heat maps representing the positive (E) or negative (F) fold change in the use of the individual TRAV subfamily genes in CD4+ cells from the indicated strains. Green, yellow, and red indicate high, medium, and low use, respectively. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is indicated by an asterisk in C and by blue squares in D–F.

This analysis was limited by the small number of anti-TRAV–specific mAbs available. Moreover, the TRAV antibodies that are available might not distinguish between subfamily members in each TRAV family (see below). To overcome this reagent limitation, we examined the TRAV repertoires of the MHCβ mutant mice in greater detail using deep sequencing. We used a set of forward primers specific for the TRAV families and common Cα reverse primers to generate a diverse PCR product that encoded the TRAVs present in the naive CD4+ T cells from each strain of mice. These fragments were sequenced with high-throughput methods. Using software developed in house, we filtered out short sequences and determined the TRAV, TRAJ, and CDR3 used by each sequence. Although we designed our TRAV primers to be family specific, of similar length, and with similar melting temperatures, we expected our results to be quantitative only in comparisons within TRAV families and to be just semiquantitative in comparisons between TRAV families. Nevertheless, the biases in analysis between each TRAV family should be common to the different types of mice, so we believed comparisons of TRAV use between mouse genotypes were justified.

We compared the use of the TRAV family and the TRAV subfamily among the mice. First, we looked at the average use of the 20 TRAV families present in the mice (Fig. 3D) in the WT vs. mutant mice. Use of the DESeq2 package (38), which is often implemented in comparing mRNA expression in different cell populations, revealed no significant differences in the frequency of TRAV use by the T cells in WT and R70A mice. However, there were reproducible and statistically significant differences in TRAV use by the T cells in T77A and WT mice. The TRAV 3, 6, and 11 families were used more frequently, and the TRAV 5, 7, and 14 families were used less frequently by T cells in T77A mice than by T cells in WT mice; the latter finding confirms our mAb-staining results (Fig. 3 A and B).

However, TRAV family analysis does not compare the use of TRAV subfamily members. In C57BL/6 mice, a portion of the TRAV locus has been triplicated. Herein genes in the supposed “original” [ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) designation] mouse TRAV locus are designated “A.” Genes in the second of the triplications are designated “D,” and genes in the third triplication are designated “N.” Distinction between these subfamily genes is important because often, but not always, the various subfamily members differ in nucleotide and consequently in protein sequence, particularly in their CDR1 and CDR2 sequences, which are of interest for our experiments (9, 19). Thus, each family is designated by a number (e.g., TRAV1, TRAV6, and so forth), and a second number and letter are used to designate the particular subfamily member (e.g., TRAV6-5A, TRAV6-5D, and TRAV6-5N).

We compared TRAV subfamily use for all the 88 TRAVs we could distinguish with our sequencing by the CD4+ T cells in the WT, βT77A, and βR70A mice. The data for all the individual TRAV subfamily genes are contained in Fig. 3 E and F. TRAVs underrepresented in the βT77A mice were 7-6A, 7-6D, 7-6N, 8-1AD, 8-2D, 12-1AN, 13-2AN. and 14-3A. TRAVs overrepresented in the βT77A mice were 3-3A, 4-4D, 6-2A, 6-3ADN, 6-4A, 6-4D, 6-6N, 6-7A, 9-2D, and 11-1AD. Differences between WT and T77A cells for all the subfamilies and their significance scores can be found in Table S3. Many of these subfamily differences account for the differences in overall family use shown in Fig. 3D.

Table S3.

Differential expression TRAV subfamily between T77A and WT

| TRAV (family-subfamily) | Log2 fold-change | Adjusted P value |

| 07-6D | 0.91 | 0.00020 |

| 08-1AD | 0.65 | 0.00002 |

| 14-3A | 0.61 | 0.00010 |

| 07-6N | 0.51 | 0.01650 |

| 07-6A | 0.50 | 0.04788 |

| 13-2AN | 0.45 | 0.02961 |

| 05-1A | 0.41 | 0.11099 |

| 12-1AN | 0.40 | 0.01353 |

| 07-2D | 0.37 | 0.10716 |

| 08-2D | 0.36 | 0.04788 |

| 14-2D | 0.36 | 0.11099 |

| 14-2AN | 0.36 | 0.09718 |

| 05-4DN | 0.34 | 0.11099 |

| 05-4A | 0.33 | 0.11099 |

| 07-4DN | 0.33 | 0.09718 |

| 14-1AN | 0.26 | 0.12138 |

| 16-1N | 0.25 | 0.07499 |

| 14-3N | 0.25 | 0.19229 |

| 07-4A | 0.24 | 0.27330 |

| 12-1N | 0.24 | 0.38439 |

| 07-3D | 0.21 | 0.18941 |

| 08-2A | 0.21 | 0.33896 |

| 09-1A | 0.19 | 0.28620 |

| 16-3D | 0.19 | 0.25871 |

| 09-1D | 0.17 | 0.34018 |

| 09-4N | 0.15 | NA |

| 14-3D | 0.13 | 0.51305 |

| 07-3A | 0.12 | 0.46563 |

| 16-1AD | 0.12 | 0.46563 |

| 01-1A | 0.10 | 0.63847 |

| 07-5DN | 0.10 | 0.63847 |

| 09-2N | 0.09 | 0.76323 |

| 07-1A | 0.09 | NA |

| 12-2DN | 0.06 | 0.77747 |

| 15-1A | 0.05 | 0.90749 |

| 13-1D | 0.05 | 0.92264 |

| 15-2A | 0.04 | 0.95188 |

| 13-4N | 0.04 | 0.95188 |

| 15-2DN | 0.02 | NA |

| 14-1D | 0.02 | NA |

| 12-3DN | 0.02 | 0.96543 |

| 17-1A | 0.02 | 0.96543 |

| 15-1D | 0.02 | NA |

| 13-2D | 0.01 | 0.96543 |

| 13-3DN | 0.00 | 0.99229 |

| 21-1A | –0.01 | 0.97915 |

| 13-1AN | –0.01 | 0.96543 |

| 09-3D | –0.01 | 0.96543 |

| 04-3AN | –0.01 | 0.96543 |

| 07-5A | –0.02 | 0.96543 |

| 13-3A | –0.02 | 0.96543 |

| 04-3D | –0.02 | 0.96543 |

| 13-4D | –0.04 | 0.96308 |

| 03-1A | –0.05 | 0.82313 |

| 12-1D | –0.09 | 0.61201 |

| 18-1A | –0.11 | 0.69596 |

| 09-2A | –0.12 | 0.61108 |

| 15-1N | –0.12 | 0.66099 |

| 12-3A | –0.13 | 0.46563 |

| 04-2A | –0.15 | 0.61201 |

| 09-4A | –0.16 | 0.48289 |

| 19-1A | –0.17 | 0.48289 |

| 06-7DN | –0.18 | 0.42806 |

| 02-1A | –0.19 | 0.34909 |

| 10-1A | –0.19 | 0.33728 |

| 06-5D | –0.19 | 0.28620 |

| 10-1DN | –0.23 | 0.19505 |

| 13-4A | –0.25 | 0.28620 |

| 06-6AD | –0.26 | 0.11099 |

| 13-5A | –0.27 | 0.19146 |

| 06-5A | –0.28 | 0.11554 |

| 03-3DN | –0.29 | 0.10319 |

| 11-1N | –0.30 | 0.13234 |

| 06-1A | –0.31 | 0.07275 |

| 04-4N | –0.32 | 0.07275 |

| 03-3A | –0.36 | 0.04078 |

| 06-7A | –0.36 | 0.02961 |

| 11-1AD | –0.36 | 0.04587 |

| 03-4A | –0.38 | 0.06653 |

| 04-4D | –0.39 | 0.02911 |

| 06-4A | –0.41 | 0.02911 |

| 06-4D | –0.43 | 0.01761 |

| 06-6N | –0.46 | 0.03018 |

| 06-3ADN | –0.50 | 0.01353 |

| 06-2A | –0.50 | 0.00117 |

| 09-2D | –0.54 | 0.00325 |

The DESeq2 package calculated fold-change and adjusted P values for the comparison of TRAV subfamilies are shown in this table.

Comparison of the TCRα Repertoire Used by Naive CD4 T Cells from WT and I-Abβ Mutant Mice.

Sequencing identified not only the TRAV families and subfamilies used in the WT and mutant mice but also the complete sequences of the TCRα domains, including the TRAVs, TRAJs, and the somatically generated CDR3α regions. Thus, we analyzed the diversity of the entire TCRα sequences among the naive splenic CD4 T cells in WT and mutant mice in several different ways. First, we examined the properties of the overall TRAV–CDR3–TRAJ repertoires. Initially, to measure the richness and diversity in the population, we used a species accumulation curve (39) in which a random sampling of our population along the x axis is shown on the y axis if each included sequence adds a unique sequence to the total number of unique sequences (Fig. 4A). This curve should plateau as the data approach the saturation of all sequences present in the cDNA sample. Sequences of the TCRαs from the three types of mice have similar curves and do not plateau even after analyzing 500,000 randomized sequences. Therefore, the naive CD4 T cells in WT, βR70A, and βT77A mice all express similarly large, diverse TCRα repertoires.

Fig. 4.

Differential use of complete TCRα in T77A mutant mice. (A) Species accumulation curves for the WT, βR70A, and βT77A mice. Each curve represents the average of the accumulation curves of three mice of the indicated genotype. (B) A Poisson-predicted distribution based on the average number of repeats in any sample is compared with the accumulation of sequences based on its frequency in the sample. (C) PCA showing that each individual run clusters by genotype on the first three components. (D and E) TCRα sequences differentially expressed in T77A and WT cells are expressed in heat maps ordered by positive (D) or negative (E) fold-change. Green, yellow, and red indicate high, medium, and low use, respectively. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is indicated by blue squares.

However, a different type of accumulation curve shows that this large repertoire is not randomly dispersed, i.e., the frequency of each sequence is not determined by a simple Poisson distribution (Fig. 4B). Despite the lack of saturation, the average number of repeats of any given unique sequence in the samples was about five but ranged from 1 to more than 10,000. Using this frequency, we constructed a Poisson-predicted accumulation curve that predicts the proportion of total sequences that should accumulate as we added sequences that occur from 1 to 20 times. This curve predicts that, if TCRα use is Poissonian, we should account for nearly all the sequences by the time we include those that occur 15 times or less, but the experimental accumulation curve generated from the sequencing data shows that these sequences account for only ∼50% of the total sequences. Likewise, more sequences were found fewer than three times than predicted by the Poisson curve. Similar results were seen with the data from the mutant mice. Thus, despite the great diversity of sequences, their frequency was not as predicted by a Poisson distribution, a feature shared with previous repertoire analyses of different human T-cell populations (40). Some of these results might be attributable to uneven efficiencies during the PCRs with the cDNA templates, but it is likely that both thymic and peripheral selective pressures also contributed.

Finally, we examined the differences in overall sequences for the three types of mice. Two types of analyses were done on the total TCRα (combining the TRAV subfamily, TRAJ, and CDR3) sequences. First, in Fig. 4C the overall data from the nine mice are represented as a three-component principal component analysis (PCA). PCA is a transformation of the data (in this case expression values for all samples) into a new coordinate system whose axes (the principal components) are defined by the variability in the data. By construction, the first principal component is the linear combination of TCRs that yields the highest variance in expression levels between samples. The second principal component is then the linear combination of TCRs that yields the highest variance in expression levels subject to being perpendicular to the first principal component, and so forth. Often the first several principal components explain the majority of the variance in the data. One then can plot the samples along the first few principal component axes to visualize high-dimensional expression data in terms of a set of simpler axes that represent the most important features of these data. In these plots, clear separation between and clustering within genotype groups indicates that the genotype is driving repertoire-wide differences in expression patterns. The WT, βT77A, and βR70A mice clustered well and were separated from each other for two of the three components. Particularly well separated were the WT and βT77A data. As a second analysis we directly compared the TRAV–CDR3–TRAJ combinations in the nine mice. Given the very large number of comparisons being made, the bar for significance differences was set very high. To reduce the number of comparisons, we set a threshold of TCRαs sequenced at least 10 times combined in all nine runs. As shown in the heat maps in Fig. 4 D and E, 84 combinations were found to be significantly different between WT and T77A mice. The figure gives a “gestalt” view of the data; the complete data for these sequences, including the TRAV, TRAJ, and CDR3 sequences and significance scores are contained in Table S4.

Table S4.

Complete TCRα differentially expressed in T77A and WT cells

| TRAV (family-subfamily) | TRAJ | CDR3 | Log2 fold-change | Adjusted P value |

| 11-1N | 4 | CVVGAVLSGSFNKLTF | 10.18 | 5.48E-03 |

| 11-1N | 27 | CVVAYNTNTGKLTF | 9.81 | 7.88E-03 |

| 11-1AD | 32 | CVVVYYGSSGNKLIF | 9.79 | 1.65E-06 |

| 01-1A | 30 | CAVSTNAYKVIF | 9.79 | 7.29E-03 |

| 11-1AD | 39 | CVVGARGNNAGAKLTF | 9.61 | 3.20E-02 |

| 01-1A | 34 | CAVRVPSNTNKVVF | 9.55 | 7.56E-06 |

| 21-1A | 56 | CIMATGGNNKLTF | 9.31 | 3.16E-02 |

| 11-1N | 17 | CVVGSAGNKLTF | 7.27 | 1.37E-09 |

| 21-1A | 56 | CILVATGGNNKLTF | 6.51 | 1.19E-02 |

| 21-1A | 49 | CILRADTGYQNFYF | 5.84 | 3.38E-02 |

| 13-2AN | 34 | CAIDPNTNKVVF | 3.93 | 2.17E-02 |

| 14-3A | 15 | CAASVGGRALIF | 3.83 | 3.99E-03 |

| 11-1AD | 57 | CVVGVNQGGSAKLIF | 3.82 | 9.71E-03 |

| 16-1N | 21 | CAMREDSNYNVLYF | 3.10 | 5.25E-04 |

| 11-1AD | 53 | CVVGADSGGSNYKLTF | 2.93 | 3.63E-02 |

| 11-1N | 57 | CVVGNQGGSAKLIF | 2.74 | 4.21E-02 |

| 16-3D | 45 | CAMREGNTEGADRLTF | 2.08 | 3.61E-02 |

| 01-1A | 30 | CAVRYTNAYKVIF | 1.86 | 1.17E-05 |

| 14-2D | 40 | CAADTGNYKYVF | 1.78 | 6.93E-03 |

| 11-1AD | 18 | CVVGSDRGSALGRLHF | 1.60 | 1.96E-02 |

| 01-1A | 28 | CAVRPGTGSNRLTF | 1.22 | 5.80E-03 |

| 19-1A | 42 | CAAGGGSNAKLTF | 0.86 | 2.03E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 21 | CVVGPMSNYNVLYF | 0.84 | 5.25E-04 |

| 06-5A | 18 | CALRRGSALGRLHF | 0.79 | 1.18E-03 |

| 21-1A | 47 | CILRNYANKMIF | 0.30 | 2.38E-05 |

| 21-1A | 45 | CILRVGAEGADRLTF | 0.16 | 1.10E-02 |

| 19-1A | 39 | CAAGGNNNAGAKLTF | –0.17 | 8.53E-03 |

| 06-5A | 34 | CALSSNTNKVVF | –1.34 | 8.29E-03 |

| 11-1AD | 42 | CVVGPNSGGSNAKLTF | –1.94 | 4.96E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 33 | CVVGVSNYQLIW | –2.09 | 4.90E-04 |

| 03-3DN | 37 | CAVVTGNTGKLIF | –2.39 | 3.21E-02 |

| 11-1N | 26 | CVVGGNNYAQGLTF | –2.45 | 1.07E-02 |

| 06-7DN | 27 | CALGDRTNTGKLTF | –2.48 | 3.75E-02 |

| 03-3DN | 27 | CAVSASTNTGKLTF | –2.48 | 1.32E-02 |

| 10-1DN | 23 | CAARYNQGKLIF | –2.53 | 1.60E-02 |

| 03-1A | 27 | CAVSDNTNTGKLTF | –2.94 | 4.65E-02 |

| 03-3DN | 13 | CAVRANSGTYQRF | –3.01 | 3.84E-02 |

| 01-1A | 9 | CAVRDLGYKLTF | –3.07 | 3.59E-02 |

| 21-1A | 57 | CILRVPMNQGGSAKLIF | –3.16 | 1.88E-02 |

| 10-1A | 21 | CAASVSNYNVLYF | –3.19 | 3.25E-02 |

| 03-3A | 32 | CAVRGGSSGNKLIF | –3.27 | 3.61E-02 |

| 06-5A | 44 | CALSDLTGSGGKLTL | –3.85 | 1.60E-02 |

| 03-4A | 39 | CAVRNNAGAKLTF | –3.93 | 2.88E-02 |

| 03-3A | 27 | CAVSASTNTGKLTF | –4.09 | 8.11E-04 |

| 10-1A | 37 | CAVITGNTGKLIF | –4.18 | 4.61E-02 |

| 01-1A | 18 | CAVREGGSALGRLHF | –4.45 | 3.18E-02 |

| 10-1DN | 12 | CAARAGGYKVVF | –4.46 | 3.15E-02 |

| 03-3DN | 27 | CAVSGNTNTGKLTF | –4.47 | 5.80E-03 |

| 06-5A | 53 | CALSASGGSNYKLTF | –4.48 | 4.51E-02 |

| 21-1A | 58 | CILRVHGTGSKLSF | –4.58 | 7.62E-03 |

| 11-1AD | 27 | CVVGRNTNTGKLTF | –4.68 | 3.14E-03 |

| 03-1A | 5 | CAVSGTQVVGQLTF | –5.06 | 3.16E-02 |

| 11-1N | 11 | CVVGEDSGYNKLTF | –5.12 | 1.65E-02 |

| 11-1N | 56 | CVVATGGNNKLTF | –5.27 | 7.29E-03 |

| 11-1AD | 18 | CVVGAEGSALGRLHF | –5.55 | 2.48E-02 |

| 03-3DN | 9 | CAVRRNMGYKLTF | –6.02 | 1.60E-02 |

| 03-3A | 40 | CAVSARTGNYKYVF | –6.32 | 7.62E-03 |

| 11-1AD | 26 | CVVNYAQGLTF | –6.40 | 6.27E-03 |

| 11-1AD | 40 | CVVGAGNYKYVF | –6.42 | 1.84E-03 |

| 11-1N | 17 | CVVGARSAGNKLTF | –6.67 | 6.85E-04 |

| 11-1AD | 6 | CVVGAGGGNYKPTF | –6.73 | 2.28E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 15 | CVVGAKGGRALIF | –6.88 | 4.20E-02 |

| 01-1A | 27 | CAVTTNTGKLTF | –8.09 | 1.85E-06 |

| 01-1A | 6 | CAVTSGGNYKPTF | –8.11 | 3.22E-06 |

| 11-1AD | 18 | CVVVYRGSALGRLHF | –9.13 | 6.20E-03 |

| 01-1A | 9 | CAVRAMGYKLTF | –9.40 | 1.75E-04 |

| 11-1AD | 27 | CVVGAPGTNTGKLTF | –9.52 | 1.65E-06 |

| 11-1AD | 32 | CVVGEDYGSSGNKLIF | –9.53 | 2.07E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 34 | CVVGATSNTNKVVF | –9.57 | 2.07E-02 |

| 11-1N | 6 | CVVGLLTSGGNYKPTF | –9.67 | 6.12E-06 |

| 21-1A | 31 | CILRVAGNNRIFF | –9.71 | 5.25E-04 |

| 11-1AD | 26 | CVVGDNNYAQGLTF | –9.79 | 1.57E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 38 | CVVPNVGDNSKLIW | –9.92 | 2.88E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 9 | CVVVNMGYKLTF | –9.92 | 2.07E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 39 | CVVGAYNNAGAKLTF | –9.98 | 3.59E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 27 | CVVVHNTNTGKLTF | –10.03 | 4.90E-04 |

| 11-1AD | 27 | CVVGAENTNTGKLTF | –10.13 | 3.19E-03 |

| 21-1A | 47 | CILRVARDYANKMIF | –10.18 | 1.22E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 27 | CVVGAKDTNTGKLTF | –10.20 | 1.31E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 26 | CVVPYAQGLTF | –10.36 | 1.65E-06 |

| 11-1AD | 6 | CVVGLLTSGGNYKPTF | –10.57 | 5.90E-04 |

| 11-1AD | 15 | CVVGASQGGRALIF | –10.66 | 1.55E-02 |

| 11-1AD | 31 | CVVGVNSNNRIFF | –10.76 | 7.56E-06 |

| 11-1AD | 27 | CVVGDTGKLTF | –11.13 | 1.89E-04 |

The DESeq2 package calculated the fold-change and adjusted P values for TCRα differentially expressed in T77A and WT cells.

In summary, although both WT and mutant mice develop large diverse repertoires, significant changes have occurred in TRAV family and subfamily and in TCRα CDR3 sequences to accommodate the mutations.

Effect of the αA64Q Mutation on the T-Cell TRBV13 Repertoire.

Our analysis of the thymus in the αA64Q mice showed apparently reduced activation from positive selection in DP thymocytes based on CD5/CD69 expression (Fig. 2 D and F). Because substantial biological and structural data have shown that the site that includes αA64Q is often used as a docking site for βY48 of the CDR2 loop of the TRBV13-2 Vβ element and perhaps also the TRBV13-3 Vβ element (21), we focused our analysis of the effects of this mutation on the repertoire of T cells using these elements. We analyzed CD4 SP thymocytes and splenic CD4+ T cells from WT and αA64Q mice with a mAb that discriminates TRBV13-2 from TRBV13-3 (Fig. 5 A and B). Flow cytometric data showed a substantial, significant shift in use from TRBV13-2 to TRBV13-3 in both populations in the A64Q mutant mice as compared with WT mice.

Fig. 5.

Differential use of TRBV13 subfamilies in A64Q mutant mice. (A and B) Representative staining with mAb MR5-2 distinguishing TRBV13-2 and TRBV13-3 (A) and frequency, represented as a ratio of TRBV13-2 to TRBV13-3 in thymic and splenic CD4+ T cells (B). Data are representative of three independent experiments containing seven mice per group. Error bars indicate SEM. (C) The frequency of the three genes that are members of the TRBV13 family as determined by next-generation sequencing. Data are averages of three independent runs. Error bars indicate SEM. (D and E) Heat maps for the TRBV–TRBJ combinations are ordered by positive (D) or negative (E) fold change. (F) Individual TCRβ sequences that are differentially expressed in A64Q and WT cells. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is indicated by asterisks in B and C and by blue squares in D–F.

Next, with a strategy similar to that used in our analysis of the TCRα repertoire in the βT77A and βR70A mice, we deep sequenced the TRBV13 domains present in naive CD4+ T cells in three WT and αA64Q mice. We created a PCR fragment with a 5′-primer common to all three members of the TRBV13 family and a 3′-primer within Cβ. Fig. 5C shows that the sequence data confirmed the significant shift from TRBV13-2 to TRBV13-3 in the αA64Q mice, but there was no change in the use of the third family member, TRBV13-1. The heat map in Fig. 5D shows all the TRBV13/TRBJ combinations with an increased frequency in WT samples compared with A64Q, and Fig. 5E shows the combinations used more frequently in the mutant. The blue squares in Fig. 5 D and E indicate statistical significance (Table S5), and these combinations group almost perfectly with TRBV13 subfamily. Furthermore, looking at the more commonly found TCRs, DESeq2 identifies individual TCRβs that are differentially expressed in the WT and A64Q mice (Fig. 5E and Table S6). Thus, these data support the previous findings on a more global scale, with particular TRBV13-2–containing domains associating the TRBV13-2 CDR2 loop with docking on the portion of the MHCII β1 helix containing with an evolutionary preference for MHCαA64.

Table S5.

Differential expression of TRBV—TRBJ combinations between A64Q and WT

| TRBV (family-subfamily) | TRBJ | Log2 fold-change | Adjusted P value |

| 13-2 | 2-1 | 0.41 | 3.33E-15 |

| 13-2 | 2-5 | 0.31 | 8.30E-09 |

| 13-2 | 1-2 | 0.26 | 9.72E-07 |

| 13-2 | 2-7 | 0.25 | 8.63E-06 |

| 13-2 | 2-3 | 0.23 | 4.15E-05 |

| 13-2 | 2-4 | 0.23 | 5.51E-07 |

| 13-2 | 2-2 | 0.22 | 1.38E-05 |

| 13-2 | 1-6 | 0.21 | 6.68E-04 |

| 13-2 | 1-1 | 0.19 | 1.88E-04 |

| 13-2 | 1-3 | 0.10 | 7.50E-02 |

| 13-2 | 1-4 | 0.10 | 7.47E-02 |

| 13-1 | 2-3 | 0.09 | 7.47E-02 |

| 13-1 | 2-7 | 0.07 | 1.51E-01 |

| 13-1 | 2-5 | 0.06 | 2.43E-01 |

| 13-1 | 2-1 | 0.06 | 3.02E-01 |

| 13-1 | 2-4 | 0.05 | 3.02E-01 |

| 13-1 | 1-6 | 0.03 | 5.67E-01 |

| 13-2 | 1-5 | 0.02 | 7.40E-01 |

| 13-1 | 1-2 | 0.00 | 9.99E-01 |

| 13-1 | 2-2 | –0.02 | 7.26E-01 |

| 13-1 | 1-1 | –0.05 | 3.25E-01 |

| 13-1 | 1-5 | –0.06 | 3.02E-01 |

| 13-1 | 1-3 | –0.09 | 1.02E-01 |

| 13-3 | 2-5 | –0.15 | 2.24E-02 |

| 13-1 | 1-4 | –0.15 | 7.17E-03 |

| 13-3 | 1-6 | –0.19 | 3.34E-04 |

| 13-3 | 2-7 | –0.27 | 6.12E-06 |

| 13-3 | 2-4 | –0.28 | 4.39E-09 |

| 13-3 | 2-1 | –0.30 | 5.07E-09 |

| 13-3 | 1-5 | –0.33 | 1.86E-08 |

| 13-3 | 2-2 | –0.35 | 1.37E-09 |

| 13-3 | 2-3 | –0.40 | 4.88E-09 |

| 13-3 | 1-3 | –0.42 | 1.38E-10 |

| 13-3 | 1-2 | –0.48 | 4.83E-13 |

| 13-3 | 1-4 | –0.48 | 6.96E-15 |

| 13-3 | 1-1 | –0.51 | 7.95E-20 |

The DESeq2 package calculated fold change and adjusted P values for the comparison of TRBV—TRBJ combinations between A64Q and WT.

Table S6.

Differentially expressed complete TCRβ between A64Q and WT

| TRBV (family-subfamily) | TRBJ | CDR3 | Log2 fold-change | Adjusted P value |

| 13-2 | 2-5 | CASGDDRGQDTQYF | 3.94 | 4.49E-02 |

| 13-2 | 1-1 | CASGDGTANTEVFF | 3.27 | 4.49E-02 |

| 13-1 | 2-4 | CASSDPGQNTLYF | 2.99 | 3.31E-02 |

| 13-1 | 2-7 | CASSDAGGTYEQYF | 2.78 | 2.40E-02 |

| 13-2 | 2-7 | CASGDARGSYEQYF | 2.58 | 4.80E-02 |

| 13-2 | 2-5 | CASGDGGNQDTQYF | 1.66 | 4.42E-02 |

| 13-1 | 2-3 | CASSDSAETLYF | 1.14 | 4.16E-02 |

| 13-3 | 2-3 | CASSDSAETLYF | –0.82 | 4.42E-02 |

| 13-3 | 1-3 | CASSDRDSGNTLYF | –0.96 | 4.42E-02 |

| 13-2 | 1-1 | CASGDAGQNTEVFF | –1.24 | 7.84E-03 |

| 13-3 | 2-7 | CASSDAGYEQYF | –1.68 | 4.49E-02 |

| 13-3 | 2-3 | CASSAETLYF | –1.87 | 4.49E-02 |

| 13-3 | 2-3 | CASSDPGSAETLYF | –2.02 | 4.16E-02 |

| 13-3 | 2-5 | CASSDSQDTQYF | –2.05 | 4.49E-02 |

| 13-1 | 2-7 | CASSDALGSSYEQYF | –2.49 | 4.16E-02 |

| 13-1 | 1-1 | CASSEQANTEVFF | –2.75 | 4.49E-02 |

| 13-3 | 2-2 | CASSENTGQLYF | –2.78 | 2.40E-02 |

| 13-3 | 2-5 | CASSDWDTQYF | –3.01 | 2.40E-02 |

| 13-3 | 2-3 | CASSDRGTSAETLYF | –3.18 | 4.16E-02 |

| 13-3 | 2-4 | CASSDESQNTLYF | –3.39 | 4.16E-02 |

| 13-3 | 2-1 | CASSEGTGGNYAEQFF | –3.59 | 4.49E-02 |

| 13-3 | 1-3 | CASSGQSGNTLYF | –3.80 | 2.45E-04 |

| 13-3 | 2-2 | CASSDGTANTGQLYF | –4.12 | 5.91E-03 |

| 13-3 | 2-3 | CASSETGGSAETLYF | –4.39 | 2.76E-02 |

The DESeq2 package calculated fold-change and adjusted P values for differentially expressed TCRβ between A64Q and WT.

Reciprocal T-Cell Recognition of the I-Ab Mutations.

Our data clearly point to adjustments in the use of particular germ-line TRAV and TRBV elements driven by the mutations in the conserved amino acids on the α1 and β1 helices of I-Ab, but they do not reveal the functional consequences of the overall change in the TCR repertoire. To begin to address this question, we tested how “foreign” the WT and mutant I-Ab molecules appeared to CD4+ T cells from the various mice. We set up one-way mixed lymphocyte reactions using all combinations of purified CD4+ T cells and APCs from the WT and mutant mice. T cells and APCs from an I-Af mouse (B10.M) were used as a control. The results (Fig. 6) show that the CD4+ T cells did not respond to APCs from the same mouse but did respond to APCs from all the other mice, as measured by IL-2 production. The T-cell responses from the WT and mutant I-Ab mice were on the same order of magnitude as the alloresponses seen with the I-Af T cells and APCs. These results predict that differences in the TCR repertoires among the WT and mutant I-Ab mice should be similar to those among mice of different MHCII haplotypes, indicating that the changes in TCR repertoire had dramatic effects on the specificity and alloreactivity of the T cells. Furthermore, in addition to the previously demonstrated influence of the varying peptide repertoire among MHC haplotypes (41), these results provide evidence for the previously suggested (42) role of the germ-line bias of TCRs for MHC in alloreactivity. Thus, it is likely that both the peptide repertoire and the germ-line–encoded bias contribute to alloreactivity to some extent.

Fig. 6.

Functional TCR repertoire differences identified by reciprocal T-cell recognition of the I-Ab mutations. One-way mixed lymphocyte reactions using all combinations of purified CD4+ T cells and APCs from WT and mutant mice. T cells and APCs from an H-2f haplotype mouse (B10.M) were used as a control. Data shown are from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

The roots of our current thinking on the evolutionary conservation of interactions between TCR and MHC amino acids came from our studies of CD4+ T cells in mice expressing a single fixed peptide–MHCII complex (18). These mice had impaired negative selection because of the absence of a diverse set of self-peptides bound to their MHCII. The T cells thus created reacted strongly to self-MHC occupied by the normal complement of self-peptides and also, surprisingly, to many different allo-MHCII alleles. We concluded that, although negative selection functions to remove high-affinity self-specific T cells, in so doing it also eliminates a large population of highly MHCII cross-reactive T cells.

Based on our subsequent functional, mutational, and structural studies, we concluded that the high cross-reactivity of these T cells was caused by dominant interactions of certain conserved amino acids in their TRAV and TRBV CDR1 or CDR2 loops with conserved sites on the MHCII helices. In complexes between the TCRs of T cells from normal mice and their activating peptide–MHCII ligands, reported by ourselves (20) and others (8), these conserved interactions were seen often, but they usually were not so dominant. These findings have led us to our current hypothesis that random combinations of germ-line TCR α- and β-genes create, with high frequency, T cells reactive to MHCII, regardless of allele, and that, to escape negative selection and contribute to the functional peripheral repertoire, T cells must bear TCRs whose somatically generated CDR3s have modulated this tendency away from generic MHC reactivity and toward peptide dependence. The results of direct mutagenesis experiments by us and others are consistent with this idea.

Our purpose in this present study was to determine how mutations in MHCII I-Ab amino acids affect T-cell development and the peripheral T-cell TCR repertoire. We chose I-Ab βT77 and αA64 for this study for several reasons: They are highly conserved among MHCII molecules; they have been seen repeatedly as sites of interaction with certain germ-line TRAV CDR1 and TRBV CDR2 amino acids; their mutation often disrupts the activation of peripheral antigen-specific T cells in response to antigen; and they do not participate directly in peptide binding. We choose I-Ab Rβ70 as a control because it is less conserved and usually interacts with the TCR CDR3 loops.

Our results show that none of the mutations prevented the development of large, diverse peripheral CD4 T-cell populations. However, depending on the mutation, there were significant changes in thymocyte subpopulations and changes in the peripheral CD4 T-cell TCR repertoire. The subtlest changes were seen with the βT77A mutation. There were no changes with this mutation in thymic cellularity or in the size of the thymic population undergoing selection (CD4+CD69+). However, compared with WT mice, the βT77A mutation led to significant shifts in TRAV family and subfamily use. In addition, this mutation led to changes in the TRAV–CDR3–TRAJ repertoire, demonstrated by PCA that clearly separated the unique sequences in the mutant mice from WT mice and from each other. Our analysis of the αA64Q mice also showed normal thymic cellularity, but in this case there was a significant reduction in the activation in thymocytes undergoing selection. In a more abbreviated peripheral repertoire analysis, we compared the use of TRBV13-2 with the other two members of this family. The importance of the intimate interaction of evolutionarily conserved TRBV-Y48 in the CDR2 of TRBV13-2 with the portion of MHCII α-chain helix containing A64 has been documented in numerous structural, functional, and thymic developmental studies (1, 20, 21). The importance of this amino acid in the other family members is not as clear: It is present, but there are other differences between the family members in their CDR1 and CDR2 regions. Our analysis showed that TRBV13-2 use by both thymic and peripheral CD4 T cells is reduced in the mutant mice, with a concomitant rise in TRBV13-3 but no change in TRBV13-1 compared with the WT mice.

The results of the present study clearly show that mutation of either βT77 or αA64 alters the repertoire of developing CD4 T cells. However, the magnitude of these effects was less than those we saw on the response of antigen-primed WT peripheral CD4 T cells to antigenic peptides presented by the mutant MHCII proteins. Likewise, mutation of conserved amino acids in the CDR2 loop of TRBV13-2 had a much more profound effect on T-cell development than did the αA64Q mutation (21). These results suggest that, during the development of the TCR repertoire, adjustments not only in TRAV use but likely also in αβ pairing and somatically generated CDR3 sequences can largely compensate for the loss of a single conserved docking site on MHCII. However, once a T-cell has been selected by WT MHCII, it no longer can make these adjustments to the loss of the docking site. It also is worth noting that our previous results with mutations in TRBV13-2 CDR2 were done with a transgenic TCR β-chain with a fixed CDR3, thus limiting the possible adjustments in repertoire to changes only in α-chain pairing. With the advent of paired TCRαβ sequencing from single cells, a future direction could be to explore the entire TCRαβ pairs and elucidate any potential compensation on the opposite TCR chain.

It has been suggested that the great deal of latitude seen in the docking angle of TCRs binding to MHC argues against the idea of evolutionarily conserved amino acids in TCR–MHC interactions. However, the many structures of TCRs that include TRBV13-2 bound to MHC show that conserved amino acids in its CDR2 loop unfailingly react with related sites on the MHCII α1 helix, even in the face of various docking angles of the TCRs. The set of structures available for analysis involving other TRAV and TRBV elements has not been as extensive, so analyses with the other TRAVs and TRBVs are not currently possible. However, because much of the tops of the MHC helices are conserved, it is possible that individual TRAV or TRBV elements prefer docking to different conserved sites or can use alternatives to the preferred site.

A recent study consistent with this idea comes from the Garcia laboratory (43). They analyzed the structures of the same TCR bound to the MHCI allele, H2-Ld (Ld), engaged by many peptides. The results showed that, although the TRAV CDR1 and CDR2 locations on the Ld α2 helix were very similar in the structures, the TRBV13-1 CDR1 and CDR2 loops had more than one docking site on the Ld α1 helix, altering the angle of engagement of the TCR with Ld. Interestingly there were discrete docking positions, not a continuous series. These results establish multiple discrete, conserved sites for TRBV13-1 docking on MHCI, the choice of which is determined by the peptide. Therefore, the single amino acid mutational approach used here may make it difficult to establish completely the TRAV or TRBV partners for a particular conserved site on the MHC helices.

The results of the current study are not inconsistent with any of the recent reports that have shown highly unusual MHC docking modes by some TCRs and non-MHC ligands for some TCRs. For example, natural killer T cells (NKT cells) and mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAIT cells) have nonconventional MHC ligands that lack the conserved MHC docking sites (44, 45). The invariant NKT and MAIT TCRs dock on their ligands in very nonconventional ways. These specialized T cells and their ligands arose evolutionarily after the development the conventional TCR–MHC system. One could consider that they have “hijacked” a part of system for another purpose, much as certain MHC-like molecules no longer function as ligands for T cells but have taken on new functions over evolutionary time.

The set of conventional TCRs that deviate most in the orientations and location with which they interact with conventional peptide–MHC complexes comes primarily from autoreactive T cells. Their footprints on MHC can drift dramatically away from those seen with foreign peptide–MHC complexes and, in one case, even reverse the orientation of the TCR on the ligand (46). These T cells are the survivors of thymic negative selection and as such may need to venture into these unusual docking modes, not found in the thymus, to improve their affinity to achieve T-cell activation.

Experiments aimed at the discovery of T cells that use non-MHC ligands have turned up T cells that recognize other molecules. Most dramatically, one laboratory constructed a mouse lacking MHCI, MHCII, CD4, and CD8 and introduced mutations to uncouple essential downstream TCR-signaling molecules from essential interactions (47–49). The mice developed a peripheral T-cell repertoire that contains T cells reactive to the surface protein CD155. The authors conclude that these experiments show that the TCR repertoire need not be MHC dependent and that the usual specificity for MHC is not inherent in the germ-line sequences of the MHC and TRAV/TRBV elements. Rather, they suggest that in normal mice MHC specificity arises by selection from a somatically generated random repertoire of TCRs, yielding TCRs that can satisfy the MHC-dependent geometry of the many components of the large TCR/coreceptor signaling complex.

Our experiments do not argue against the generation of T cells of these non-MHC specificities. In fact, given the recombinational capacity of the thymus to generate an enormous number of unique TRAV and TRBV CDR3 loops, their existence is inevitable. However, if the initial, unselected TCR repertoire is random, the frequency of T cells specific for any particular protein, such as CD155 or MHC proteins, will be very low. Subsequent culling of this scarce MHC-specific repertoire during the nonproliferative phase of T-cell development to make it both self-MHC restricted and self-MHC tolerant will further reduce its size greatly, making the generation of the well-established, very large peripheral T-cell repertoire very difficult. However, predisposing the preselection TCR repertoire toward MHC recognition via embedded conserved amino acids in MHC and TCR proteins to promote their interaction should separate the “wheat” from the “chaff” during selection much more efficiently. Evidence presented here and in previous papers suggests that this idea is, to some extent, correct and that the preselected TCR repertoire is already skewed toward MHC reactivity (9, 15–17, 21, 23).

Materials and Methods

Mutant MHC I-Ab α- and β-Chains.

Plasmids encoding MHCII I-Ab α- and β-chains were previously used (29). MHC mutations were cloned by overlapping primers using engineered restriction sites. The I-Ab α-chain was cloned into a murine stem cell virus (MSCV)-based retroviral plasmid with an internal ribosome entry site plus Thy1.1 as a reporter. The I-Ab β-chain was cloned into a similar MSCV vector with a GFP reporter. These MSCV vectors were also available in the J.W.K./P.M. laboratory.

Retroviral Packaging.

Retroviral plasmids were cotransfected into Phoenix cells with pCLEco accessory plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Retrovirus-containing supernatants were collected 48–72 h after transfection and were filtered through a 0.45-μm filter to remove cell debris.

MHC-Expressing Cell Lines.

MHC constructs were expressed by retroviral transduction of an APC line, M12.C3. M12.C3 cells are derived from a BALB/C B-cell lymphoma that was selected for loss of I-A expression (27), although they contain a functional I-Ad α-chain. For retroviral infection of M12.C3 cells, 105 cells were spin-infected with retroviral supernatants containing 8 µg/mL of Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) for 90 min at 37 °C. Cells were expanded in culture and subsequently were cloned by limiting dilution; clones of equal MHC expression were chosen.

Preparation and Stimulation of Bulk T-Cell Hybridomas.

Antigen-specific T-cell hybridomas were generated by immunizing mice with the desired antigen emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant. The para-aortic lymph node cells were isolated 7 d later, expanded in culture for 3 d with the same antigen with which the mice had been immunized, and cultured in IL-2 for 5 d. After this in vitro culture, activated T cells were fused to BWα−β−, a variant of the fusion partner BW5147 generated to lack both TCR α- and β-chains (50).

For stimulations, 5 × 104 to 1 × 105 hybridomas were cultured with different stimuli for 4–24 h in 200 µL culture medium in 96-well microtiter plates. Hybridoma responses were measured by CD69 expression and IL-2 production. IL-2 ELISAs were done using the anti–IL-2 antibody JES6-1A12 (eBioscience) to capture and the biotinylated antibody clone JES6-5A4 (eBioscience) with streptavidin conjugated to HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch) to detect the bound antibody.

MS.

WT and mutant I-Ab proteins were immunoprecipitated from lysates of roughly 109 of the transduced M12.C3 cells using antibody clone Y3P. Peptides were eluted in 2.5-M acetic acid and were separated from beads, antibodies, and MHCII molecules by passage through a 10,000-Da cutoff ultrafiltration unit (Millipore) and were subjected to MS or MS-MS analysis as previously reported (32). Peptides were analyzed via LC/MS-MS or LC/MS on an Agilent Q-TOF instrument (model 6520) as described in detail in SI Materials and Methods.

Flow Cytometry.

Cells, either ex vivo or hybridomas, were preincubated with supernatant from the anti-CD16/CD32 producing hybridoma, 2.4G2. Cells were stained under saturating conditions with antibodies to mouse TCRβ (clone H57-597), CD4 (clone GK1.5), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), CD25 (clone PC61), CD44 (clone IM7), CD5 (clone 53-7.3), CD69 (clone H1.2F3), CD24 (clone M1/69), B220 (clone RA3-6B2), CD11b (clone M1/70), γδ TCR (clone GL3), CD62L (clone MEL-14), Vβ8.x (clone F23.1), Vβ8.2 (clone F23.2), Vβ8.3 (clone 1B3.3), Vβ8.1/2 (clone MR5-2), and Vα2 (B20.1), purchased from eBioscience or BD Pharmingen or generated in house. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan, LSR II, or LSRFortessa system (BD Biosciences).

Generation of Knockin MHC Mutant Mice.

As described in detail in the SI Materials and Methods, embryos were isolated from superovulated female mice (51) and pronuclear injections performed with ZFN mRNA (Sigma-Aldrich) to introduce point mutations in the genes encoding IAb. All animals were housed and maintained in the Biological Resource Center within NJH in accordance with the research guidelines of the National Jewish Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Sequencing of TCR Repertoire.

Naive CD4 T cells were stained as described above and sorted at the National Jewish Health Flow Cytometry Core Facility. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Kit (Invitrogen). cDNA was made using the SuperScript VILO Kit (Invitrogen). Details on the PCRs used to generate the sequencing library and the sequences of the primers can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis of TCR Repertoires.

Differential expression analyses were performed using the DESeq2 package (v1.8.1) (38) in the R language (v3.2.2) (52). Details of these analyses can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

MS.

Samples were analyzed by LC/MS in duplicate. Data were mined in Mass Hunter Qualitative Analysis software (Agilent Technologies) using an untargeted feature-finding algorithm. Extracted molecular features, e.g., isotopes, charge states, and adducts, were deconvoluted and assigned to peptide masses. For each peptide, all assigned charge states were combined, the peak areas for each were summed, and the total area (volume) was used for relative peptide abundance. Extracted peptide molecular features were imported into Mass Profiler Professional (Agilent Technologies). Peptides were aligned by mass and retention time and were filtered for minimum relative frequency across replicates.

LC/MS.

Peptides were analyzed via LC/MS-MS or LC/MS on an Agilent Q-TOF (model 6520) mass spectrometer with an HPLC-Chip interface. All HPLC components were Agilent 1100. Buffer A of the Nanopump was comprised of HPLC grade water and 0.1% formic acid, and buffer B was 90% acetonitrile, 10% HPLC-grade water, and 0.1% formic acid. The loading pump used 3% acetonitrile, 97% HPLC-grade water, and 0.1% formic acid. The HPLC chip (Agilent G4240-62006) consisted of a 40-nL enrichment column and a 150 mm × 75 μm analytical column.

To ensure that comparable amounts of peptide material were analyzed for each fraction, 0.5 μL of each sample was analyzed initially to establish overall relative abundance. Initial runs were performed with a 10-min LC/MS method (gradient was from 3–30% buffer B over 0–5 min). Areas of extracted total ion currents were used to calculate injection volumes for each sample. Subsequent runs were with injection volume-corrected samples and used a 30-min LC/MS-MS or LC/MS/ method (gradient from 3–30% buffer B over 0–25 min).

Raw LC/MS-MS data were extracted and searched using the Agilent Spectrum Mill search engine, and spectra were searched against a UniProt mouse database. “Peak picking” was performed within Spectrum Mill with the following parameters: signal-to-noise was set at 10:1, variable modifications were searched for oxidized methionine and deamidated asparagine, maximize charge state for peptides was set at 7, with a precursor mass tolerance of 20 ppm and a product mass tolerance of 50 ppm. Matched peptides were filtered with a score >6 and a scored peak intensity of >60%.

Generation of Knockin MHC Mutant Mice.

Female mice were superovulated using pregnant mare serum gonadotropin and human chorionic gonadotropin (Calbiochem) to mimic FSH and luteinizing hormone, respectively. Superovulated females were placed in a cage containing a stud male. The following morning, females were checked for the presence of a vaginal plug. Embryos from plugged females were isolated, and cumulus cells were digested and washed in hyaluronidase to produce clean single-cell embryos for microinjection (51).

Pronuclear injection of the single-cell embryo was done at the Mouse Genetic Core Facility at National Jewish Health. Pronuclei were injected with ZFN mRNA (Sigma-Aldrich) and an oligo homology-directed repair template (Integrated DNA Technologies), or a dsDNA fragment was generated and purified in house as follows. A plasmid encoding roughly 2,000 bp of homology plus the desired mutation was digested with restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs) engineered to remove the bacterial portion of the plasmid. Digestion products were run on an ultra-pure SeaPlaque agarose gel (Lonza). The correct DNA band was excised and purified sequentially using a Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research), a PureLink PCR Purification Kit (Invitrogen), and Millipore Dot Dialysis (Millipore).

Injected embryos were surgically implanted into pseudopregnant females. After birth pups were screened for presence of the desired mutation by restriction digest and sequencing.

Sequencing of the TCR Repertoire.

For sequencing of TCR α-chains, a two-step PCR was done which added the machine oligonucleotides as well as barcodes for the sequencing runs. The first PCR included a reverse oligonucleotide in the constant region of the α-chain and a mixture of forward oligonucleotides that together cover all the different TCRα family members. The sequence or sequences for each TRAV family are as follows:

TRAV01: GAGGGAACCTTTGCTCGGGTC

TRAV02: TATGAAGGGCAAGAAGTGAAC

TRAV03: CArGTCTTCAGTTGCTTATGA

TRAV04: TGCTCTGAGATGCAATTTTwC

TRAV05a: GGTGGAACAGCTCCCTTCCTC

TRAV05b: ATGGCTGCAGCTGGATGGGA

TRAV06a: GGACAAGGTCCACAGCTCCT

TRAV06b: GGAGAAGGTCCACAGCTCCTC

TRAV06c: GTCCAATATCCTGGAGAAGG

TRAV07: AGCAGAGCCCAGAATCCCTCA

TRAV08: AAAGAGCCAATGGGGAGAAG

TRAV08, GAATAGTCAACTAGCAGAAG

TRAV09: AGCTGAGATGCAAsTATTCCT

TRAV10: ACTTACACAGATACTGCyTCA

TRAV11: CACAGGCAAAGGTCTTGTGTC

TRAV12: GCTGAACTGCACCTATCAGA

TRAV13: TGGTTCTGCAGGAGGGGGArA

TRAV14: GTCCCCAATCTCTGACAGTCT

TRAV15: ACTGTTCATATrAGACAAGT

TRAV16: TGGAGAAGACAACGGTGACA

TRAV17: GTTATTCATACAGTGCAGCAC

TRAV18: ACCGCACGCTGCAGCTCCTCA

TRAV19: TACCCTGACAACAGCCCCACA

TRAV21: GTAGCCACGCCACAATCAGTG

The second PCR included just one forward oligonucleotide to add the machine oligonucleotide and a reverse oligonucleotide to add the barcode. For TCR β-chains, one PCR was done that contained a forward oligonucleotide priming all three TRBV13 family members at an identical region, the sequencing machine oligonucleotide CCACTACGCCTCCGCTTTCCTCTCTATGGGCAGTCGGTGATGCTGAGGCTGATCCATTA, and a reverse oligonucleotide that primed the Cβ region and contained the machine oligonucleotide and the barcode, CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCCGACTCAGCTAAGGTAACGATCTTGGGTGGAGTCACATTTCTC.

Statistical Analysis of TCR Repertoires.

Differential expression analyses were performed using the DESeq2 package (v1.8.1) (38) in the R language (v3.2.2) (52). This widely used package was designed for RNA sequencing experiments, but its statistical model can be appropriate for count data generated by other high-throughput methods. For example, DESeq2 is used to test for differential abundance of microbial DNA sequences (53), and its predecessor DESeq has been used for differential methylation analyses (54, 55). In conjunction with the DiffBind package (56), DESeq2 has also been used for differential binding analyses of ChIP-Seq data (57).

DESeq2 fits negative binomial regression models to each feature (each TCR family or subfamily in the present context) to compare between groups (genotypes). First, it calculates size factors for each sample (in this case, each animal) to account for differences in repertoire size. Then it estimates the negative binomial dispersion parameter for each feature, sharing information across features with similar expression levels to moderate extreme empirical dispersion estimates. Finally, with the computed size factors and dispersions it performs Wald tests on each feature to test for differential expression between groups (genotypes). Features were considered differentially expressed if they had a Benjamini–Hochberg (58) adjusted P value (i.e., false-discovery rate) <0.05.

Two and three-dimensional principal components plots were created using the pca3d package in R (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pca3d/index.html). Because the results of a PCA using raw counts would be overly impacted by the highest-expression features, the raw counts were first regularized using the rlog transformation in DESeq2. This transformation is similar to a log2 transformation but returns finite values when counts equal 0. The principal components of this regularized data were computed by the prcomp function, which first normalizes the features to have mean 0 and variance 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Francis Crawford and Ella Kushner, Randy Anselment and Thomas Danhorn of the National Jewish Health Center for Genes, Environment and Health, Josh Loomis and Shirley Sobus of the National Jewish Health Cytometry Core for technical assistance, and Dr. Greg Kirchenbaum for assistance with some of the experiments in this paper. This work was supported by NIH Grants AI-18785 (to P.M.), AI092108 (to L.G.), AI103736 (to L.G.), and T32 AI007405.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1609717113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Yin L, Scott-Browne J, Kappler JW, Gapin L, Marrack P. T cells and their eons-old obsession with MHC. Immunol Rev. 2012;250(1):49–60. doi: 10.1111/imr.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sunyer JO. Evolutionary and functional relationships of B cells from fish and mammals: Insights into their novel roles in phagocytosis and presentation of particulate antigen. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2012;12(3):200–212. doi: 10.2174/187152612800564419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Criscitiello MF, et al. Shark class II invariant chain reveals ancient conserved relationships with cathepsins and MHC class II. Dev Comp Immunol. 2012;36(3):521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper MD, Alder MN. The evolution of adaptive immune systems. Cell. 2006;124(4):815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babbitt BP, Allen PM, Matsueda G, Haber E, Unanue ER. Binding of immunogenic peptides to Ia histocompatibility molecules. Nature. 1985;317(6035):359–361. doi: 10.1038/317359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buus S, Sette A, Colon SM, Jenis DM, Grey HM. Isolation and characterization of antigen-Ia complexes involved in T cell recognition. Cell. 1986;47(6):1071–1077. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jerne NK. The somatic generation of immune recognition. Eur J Immunol. 1971;1(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830010102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng D, Bond CJ, Ely LK, Maynard J, Garcia KC. Structural evidence for a germline-encoded T cell receptor-major histocompatibility complex interaction ‘codon’. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):975–983. doi: 10.1038/ni1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marrack P, Scott-Browne JP, Dai S, Gapin L, Kappler JW. Evolutionarily conserved amino acids that control TCR-MHC interaction. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:171–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia KC, Adams JJ, Feng D, Ely LK. The molecular basis of TCR germline bias for MHC is surprisingly simple. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(2):143–147. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fink PJ, Bevan MJ. H-2 antigens of the thymus determine lymphocyte specificity. J Exp Med. 1978;148(3):766–775. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.3.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. Restriction of in vitro T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic choriomeningitis within a syngeneic or semiallogeneic system. Nature. 1974;248(5450):701–702. doi: 10.1038/248701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappler JW, Roehm N, Marrack P. T cell tolerance by clonal elimination in the thymus. Cell. 1987;49(2):273–280. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kisielow P, Blüthmann H, Staerz UD, Steinmetz M, von Boehmer H. Tolerance in T-cell-receptor transgenic mice involves deletion of nonmature CD4+8+ thymocytes. Nature. 1988;333(6175):742–746. doi: 10.1038/333742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]