Significance

Reversal of the “exhausted” phenotype of T-cells that target persistent viruses, such as HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C represents a potentially novel means to control persistent infections. Here we examined the drop in hepatitis C viral levels that often follows pregnancy as a potential model of T-cell restoration. We found that women with significant postpartum reductions in viremia had stronger postpartum T-cell responses against hepatitis C and were more likely to carry a favorable IFN-λ3 (IFNL3) genotype and high-expression HLA-DPB1 (human leukocyte antigen DP β-chain) alleles than women with stable persistent viremia. These findings support the concept that the postpartum period may indeed serve as a unique model for identifying factors associated with immune restoration against persistent infections.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, pregnancy, T-cell, IFNL3, HLA-DPB1

Abstract

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is characterized by exhaustion of virus-specific T-cells and stable viremia. Pregnancy is an exception. Viremia gradually climbs during gestation but sometimes declines sharply in the months following delivery. Here, we demonstrated that postpartum HCV control was associated with enhanced virus-specific T-cell immunity. Women with viral load declines of at least 1 log10 between the third trimester and 3-mo postpartum exhibited HCV-specific T-cell responses of greater breadth (P = 0.0052) and magnitude (P = 0.026) at 3-mo postpartum than women who failed to control viremia. Moreover, viral dynamics were consistent in women after consecutive pregnancies, suggesting genetic underpinnings. We therefore searched for genetic associations with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles and IFN-λ3 gene (IFNL3) polymorphisms that influence HCV infection outcome. Postpartum viral control was associated with the IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype CC (P = 0.045 at 6 mo) that predicts a positive response to IFN-based therapy. Suppression of virus replication after pregnancy was also strongly influenced by the HLA class II DPB1 locus. HLA-DPB1 alleles are classified by high and low patterns of expression. Carriage of at least one high-expression HLA-DPB1 allele predicted resurgent virus-specific T-cell immunity and viral control at 3-mo postpartum (P = 0.0002). When considered together in multivariable analysis, IFNL3 and HLA-DPB1 independently affected viral control at 3- and 6-mo postpartum. Together, these findings support a model where spontaneous control of HCV such as sometimes follows pregnancy is governed by genetic polymorphisms that affect type III IFN signaling and virus-specific cellular immune responses.

Nearly 75% of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections persist long-term, predisposing to complications such as hepatic cirrhosis and carcinoma. The HCV-specific T-cell response is a major determinant of whether an infection will resolve or persist (1). In resolving infections, CD8+ cytotoxic and CD4+ helper T cells target a broad array of viral epitopes and maintain antiviral activity until viremia is no longer detectable (1, 2). Persisting infections may similarly begin with robust HCV-specific T-cell responses that transiently reduce viremia, but viral control is ultimately lost (1, 2). In the chronic phase of infection CD8+ T-cells typically exhibit impaired cytotoxicity and antiviral cytokine secretion or fail to recognize circulating viruses because of escape mutations in viral class I epitopes (1–3). At the same time, virus-specific CD4+ T cells lack proliferative capacity and often become undetectable (4). With the onset of immune exhaustion, stable high-level viremia becomes the norm (5).

A unique exception to this pattern of stable high-level viremia during chronic infection has been described in pregnancy. HCV replication tends to increase with gestation and then sometimes falls markedly 1–3 mo after delivery (6–8). The physiologic basis for this phenomenon is uncertain, but resurgence of antiviral immunity may be important. A recent retrospective analysis of banked serum samples from HCV-infected pregnant women found that serum IL-12 and IFN-γ levels were higher in the postpartum period in women whose viral load declined after delivery compared with aviremic women who had previously resolved infection (9). We recently noted in two women with large declines in viremia after pregnancy that circulating viral genomes lost escape mutations in several human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I epitopes during late gestation and then regained escape mutations by 3-mo postpartum (10). These findings pointed to a reduction of CD8+ T-cell pressure on HCV during pregnancy, presumably as a result of the regulatory mechanisms that mediate maternofetal tolerance. These findings also suggested that postpartum declines in viremia might be caused by restoration of functional HCV-specific cellular immunity, an intriguing hypothesis given the exhausted state of cellular immunity in chronic HCV infection.

Genome-wide association studies have highlighted the importance of both innate and adaptive immunity in the control of HCV infection. The polymorphisms most strongly linked to spontaneous resolution cluster on chromosome 19 near the type III IFN gene encoding IFN-λ3 (IFNL3) and on chromosome 6 near class II HLA genes (11). Favorable IFNL3 genotypes, such as rs12979860 CC, predict both spontaneous resolution of acute infection and resolution of chronic infection upon treatment with pegylated-IFN-α and ribavirin (11–13). Specific class II HLA alleles, such as HLA-DQB1*03 and -DRB1*11, and several class I alleles, such as HLA-B*27, -B*57, and -C*01, have been linked to spontaneous resolution of acute HCV infection, although effects vary between populations (14–18). Whether IFNL3 or HLA genotypes influence late spontaneous control of chronic infection after pregnancy is unknown. Here we examined effects of HCV-specific cellular immune responses, IFNL3 and HLA genotypes, and other host factors on viral dynamics in a cohort of HCV-monoinfected women. Postpartum viral control was associated with a rebound of virus-specific T-cell immunity and was predicted by maternal IFNL3 genotype, and unexpectedly, maternal HLA-DPB1 (HLA-DP β-chain) genotype.

Results and Discussion

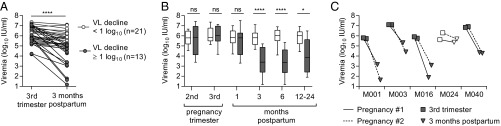

To identify determinants of postpartum HCV control, we obtained serial blood samples from 34 HCV-infected women from the third trimester of pregnancy through 3- to 24-mo postpartum (demographic data provided in Table 1 and Table S1). Consistent with prior reports (6–8), median viral load fell from a peak of 5.96 log10 IU/mL in the third trimester of pregnancy to a nadir of 5.15 log10 IU/mL 3 mo after delivery (P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test), with individual changes in viremia ranging from a 0.2 log10 increase to a 4.1 log10 reduction during this timeframe (Fig. 1A). Subjects were first parsed based on whether (n = 13) or not (n = 21) they achieved a 1 log10 IU/mL drop in viral load from the third trimester of pregnancy to 3-mo postpartum (Fig. 1A). The 1 log10 threshold was selected because this magnitude of viral load change is unusual in nonpregnant chronically infected adults, where viral load typically fluctuates by less than 0.5 log10 (5). Viremia in the two groups was similar in late pregnancy (P = 0.8) but remained substantially lower through at least 1-y postpartum in the group of women whose viral load had fallen at least 1 log10 by 3-mo postpartum (Fig. 1B). Among five women in whom viremia was tracked through consecutive pregnancies, patterns of viral load decline after the first and second deliveries were remarkably consistent (Fig. 1C). Four women had viral load declines in excess of 1 log10 with each pregnancy, whereas one subject (M024) had minimal viral load reduction after each pregnancy, suggesting that the capacity to control viremia postpartum may be governed by stable host or viral factors.

Table 1.

Viral genotype, IFNL3 genotype, and demographic characteristics of 34 HCV-infected mothers

| Characteristics | Median (range) or n (%)* |

| Age at delivery (y) | 27 (17–36) |

| Estimated duration of HCV infection at delivery (y) | 2.8 (0.5–29) |

| Route of HCV acquisition | |

| Injection drug use | 26 (76) |

| Vertical | 2 (6) |

| Needle stick | 1 (3) |

| Unknown/multiple | 5 (15) |

| HCV genotype | |

| 1a/1b | 21 (62) |

| 2a/2b | 7 (21) |

| 3a | 6 (18) |

| IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype | |

| CC | 14 (41) |

| CT | 16 (47) |

| TT | 4 (12) |

| Gravida | 3 (1–7) |

| Gestational age at delivery (wk) | 39 (27.9–40.1) |

| Cesarean delivery | |

| Yes | 9 (26) |

| Breastfeeding | |

| Yes | 13 (38) |

| Duration (wk) | 9 (2–17) |

n (%) is in boldface.

Table S1.

Individual viral genotypes, IFNL3/4 genotypes, and demographic characteristics of HCV-infected mothers

| Subject ID | Age at delivery (y) | Estimated duration of HCV infection* (y) | Presumed route of infection | HCV genotype | IFNL3 rs12979860 | IFNL4 rs368234815 | Gravida | Pregnancy gestation at delivery (wk) | Mode of delivery | Breast-feeding duration (wk) |

| M001† | ||||||||||

| First | 27 | 12.4 | IDU | 2b | CC | TT/TT | 4 | 39.6 | Cesarean | 0 |

| Second | 30 | 15.3 | 5 | 40.1 | Cesarean | 0 | ||||

| M003† | ||||||||||

| First | 34 | 0.6 | Needle stick | 1a | CC | TT/TT | 4 | 34.0 | Vaginal | 21 |

| Second | 36 | 1.9 | 5 | 38.0 | Vaginal | 15 | ||||

| M005 | 36 | 16.6 | IDU | 1a | CC | TT/TT | 7 | 27.9 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M006 | 33 | 1.5 | IDU | 3a | CT | ΔG/TT | 4 | 36.4 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M008 | 17 | 17.3 | Vertical | 1a | CT | ΔG/TT | 1 | 36.0 | Vaginal | 11 |

| M009 | 27 | 2.5 | IDU | 1a | CT | ΔG/TT | 3 | 37.1 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M010 | 28 | 5.6 | IDU | 1a | CT | ΔG/TT | 6 | 37.3 | Vaginal | 11 |

| M013 | 26 | 0.9 | Unknown | 3a | CC | TT/TT | 5 | 34.9 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M016† | ||||||||||

| First | 24 | 4.6 | IDU | 2a | CC | TT/TT | 2 | 36.4 | Cesarean | 0 |

| Second | 26 | 6.0 | 3 | 38.3 | Cesarean | 0 | ||||

| M018 | 24 | Unknown | Unknown | 1b | CC | TT/TT | 2 | 39.0 | Cesarean | 2 |

| M019 | 29 | Unknown | Unknown | 3a | CT | ΔG/TT | 7 | 28.6 | Cesarean | 13 |

| M022 | 24 | 6.3 | IDU | 1b | CT | ΔG/TT | 3 | 40.0 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M023 | 30 | 9.6 | IDU | 2 | CT | ΔG/TT | 2 | 39.0 | Cesarean | 0 |

| M024† | ||||||||||

| First | 28 | 28.4 | Vertical | 1a | CT | ΔG/TT | 5 | 34.1 | Cesarean | 11 |

| Second | 29 | 29.3 | 6 | 36.1 | Vaginal | 7 | ||||

| M025 | 26 | 1.5 | IDU | 1a | CT | ΔG/TT | 2 | 40.1 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M026 | 27 | 1.5 | IDU | 1a | CC | TT/TT | 3 | 38.4 | Vaginal | 9 |

| M027 | 23 | 1.8 | IDU | 3a | CC | TT/TT | 3 | 38.3 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M028 | 29 | 1.9 | IDU | 2 | CT | ΔG/TT | 5 | 39.7 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M030 | 31 | 13.9 | Unknown | 1a | CT | ΔG/TT | 4 | 38.6 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M031 | 32 | 0.5 | IDU | 1a or 1c | CT | ΔG/TT | 5 | 35.0 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M033 | 26 | 0.6 | IDU | 1a | CC | TT/TT | 2 | 39.1 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M034 | 25 | 11.2 | IDU | 1b | CC | TT/TT | 3 | 39.1 | Vaginal | 17 |

| M036 | 26 | 3.2 | IDU | 2b | CC | TT/TT | 2 | 39.9 | Vaginal | 3 |

| M037 | 27 | Unknown | Unknown | 1a or 1b | CT | ΔG/TT | 5 | 38.9 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M038 | 30 | 2.8 | IDU | 3a | TT | ΔG/ΔG | 2 | 39.9 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M039 | 30 | 3.8 | IDU | 2b | CT | ΔG/TT | 4 | 40.0 | Cesarean | 0 |

| M040† | ||||||||||

| First | 24 | 3.4 | IDU | 1a | CC | TT/TT | 2 | 39.3 | Cesarean | 0 |

| Second | 25 | 4.5 | 3 | 39.1 | Cesarean | 15 | ||||

| M043 | 30 | 1.3 | IDU | 1a | TT | ΔG/ΔG | 3 | 39.0 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M048 | 28 | 1.2 | IDU | 1a | TT | ΔG/ΔG | 3 | 39.1 | Vaginal | 6 |

| M051 | 26 | 7.2 | IDU | 1a | CT | ΔG/TT | 4 | 39.1 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M062 | 25 | 1.8 | IDU | 1a | CC | TT/TT | 6 | 38.9 | Vaginal | 9 |

| M066 | 25 | 1.1 | IDU | 3a | CC | TT/TT | 4 | 39.4 | Vaginal | 0 |

| M067 | 26 | 3.7 | IDU | 1a | CT | ΔG/TT | 3 | 39.2 | Cesarean | 5 |

| M068 | 25 | 1.0 | IDU | 2b | TT | ΔG/ΔG | 2 | 39 | Cesarean | 0 |

IDU, injection drug use.

Assumed HCV infection acquired 6 mo after initiation of IDU or at end of reported period of IDU if duration less than 6 mo.

For mothers followed through two consecutive pregnancies (M001, M003, M016, M024, and M040), the second pregnancy was used for statistical analyses.

Fig. 1.

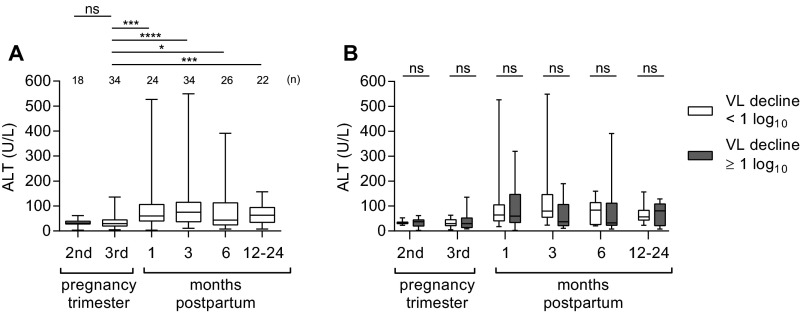

Postpartum dynamics of hepatitis C viremia. (A) Individual viral loads of 34 HCV monoinfected women at pregnancy and 3-mo postpartum. (B) Longitudinal viral load differences of women with (gray shaded) and without (white) a postpartum viral load decline of 1 log10 or more by 3-mo postpartum (Mann–Whitney U test). Boxes indicate median and interquartile range (IQR); whiskers indicate range. (C) Third trimester and 3-mo postpartum viral load in five subjects followed through first (solid line) and second (dashed line) pregnancies. P value summary: ns, P ≥ 0.05; *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001.

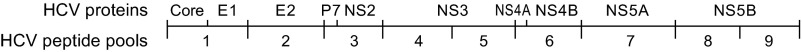

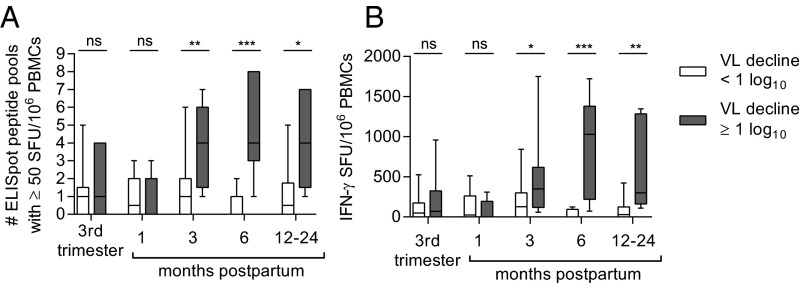

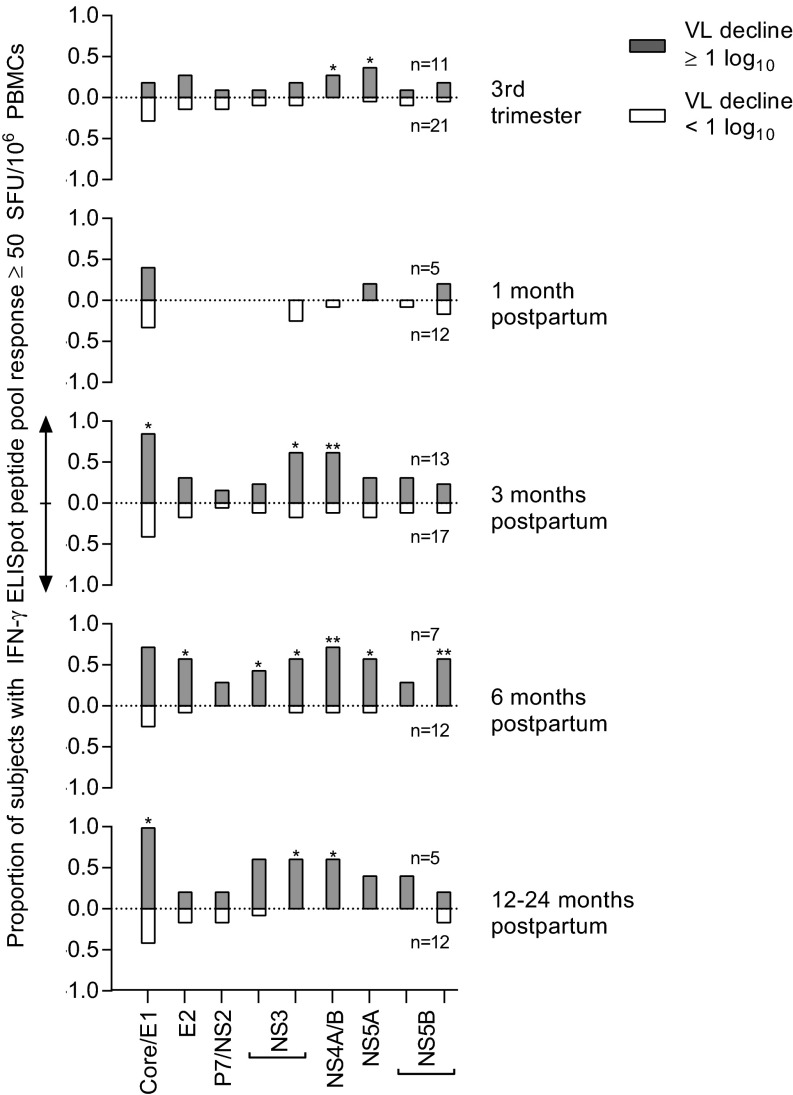

We first tested our primary hypothesis that a restoration of cellular immunity contributes to postpartum viral control by comparing longitudinal peripheral blood HCV-specific T-cell responses of women with and without postpartum viral load declines. Nine pools of genotype-matched overlapping peptides spanning the HCV polyprotein were used to stimulate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in an IFN-γ ELISpot assay (Fig. S1). We found that the HCV-specific T-cell responses of the two groups of women were of similar breadth (number of peptide pools targeted) and magnitude (sum of responses) in late pregnancy and at 1-mo postpartum. However, by 3-mo postpartum the breadth (P = 0.0052) and magnitude (P = 0.026) of the antigen-specific T-cell responses were significantly greater in women with viral control, and remained so through more than 1 y of follow-up (Fig. 2), targeting both structural and nonstructural viral proteins (Fig. S2). The finding of restored T-cell immunity in subjects with a significant viral load decline is consistent with our earlier study of HCV genome evolution in two of these subjects (M001 and M003) that provided indirect virologic evidence for restored T-cell immunity after pregnancy. In that study, we noted emergence of viral variants with escape mutations in class I epitopes after delivery, suggesting a postpartum resurgence of CD8+ T-cell selection pressure (10).

Fig. S1.

HCV proteins represented in the nine peptide pool arrays used for the IFN-γ ELISpot assay.

Fig. 2.

Longitudinal HCV specific T-cell responses as measured by IFN-γ ELISpot breadth (A) and magnitude (B) in women with (gray shaded) and without (white) a postpartum viral load decline of 1 log10 between the third trimester and 3-mo postpartum (Mann–Whitney U test). P value summary: ns, P ≥ 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Fig. S2.

Distribution of HCV-specific T-cell responses across the viral polyprotein in women with (gray bars, upward y axis) and without (white bars, downward y axis) viral load decline of 1 log10 by 3-mo postpartum (Fisher’s exact test). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels are known to rise in some HCV-infected women after delivery (7–9, 19), presumably because of immune-mediated hepatocyte injury (1, 2). Postpartum ALT elevations in our cohort were generally mild, with median levels peaking at 75 U/L at 3-mo postpartum (Fig. S3A). ALT elevation was not associated with viral control (Fig. S3B). In fact, ALT levels were normal (<40 U/L) at 3- and 6-mo postpartum in over half of the women who achieved viral control. This finding suggests that noncytolytic immune mechanisms, such as IFN-γ production by HCV-specific T-cells, may be important for controlling HCV replication after pregnancy. A similar phenomenon has been described in acute HCV infections where viral control is not always associated with ALT elevation even when HCV-specific T-cells are found to infiltrate the liver (20).

Fig. S3.

Postpartum ALT elevation and relation to viral control. (A) Matched pairs analysis of ALT levels among 34 HCV monoinfected women versus third-trimester values (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). (B) Longitudinal ALT differences of women with (gray shaded) and without (white) a postpartum viral load decline of 1 log10 or more by 3-mo postpartum (Mann–Whitney U test). P value summary: ns, P ≥ 0.05; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Because of the very consistent pattern of viremia in women followed through two consecutive pregnancies (Fig. 1C), we considered the possibility that HCV control in the postpartum period is genetically regulated. We first examined effects of maternal IFNL3 genotype and other host and viral factors on ability to achieve a ≥1 log10 drop in viremia at 3 or 6 mo after delivery. In addition to strong and broad T-cell responses, postpartum viral control was found to be associated with maternal IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype CC (P = 0.045 at 6-mo postpartum) (Table S2). No significant effects were found for maternal age, estimated duration of maternal infection, number of prior pregnancies, gestational age at delivery, mode of delivery, breastfeeding, ALT, viral genotype, or third-trimester viral load in these univariable analyses (Table S2).

Table S2.

Predictors of 1 log10 decline in viremia at 3- or 6-mo postpartum

| Viral load decline: Third trimester to 3 mo postpartum | Viral load decline: Third trimester to 6 mo postpartum | |||||||||

| <1 log10 IU/mL | ≥1 log10 IU/mL | <1 log10 IU/mL | ≥1 log10 IU/mL | |||||||

| Variable | n | Median (IQR) | n | Median (IQR) | P | n | Median (IQR) | n | Median (IQR) | P |

| Maternal age at delivery (y) | 21 | 26.6 (24.7, 30) | 13 | 27.2 (25.6, 30.1) | 0.625 | 12 | 26.2 (24, 30.2) | 14 | 26.5 (25.4, 30) | 0.631 |

| Estimated duration of HCV infection | 19 | 3.7 (1.8, 11.2) | 12 | 1.5 (1.1, 5.7) | 0.108 | 12 | 3 (1.8, 5.7) | 12 | 1.9 (1.5, 8.7) | 0.660 |

| Gravida | 21 | 4 (3, 5) | 13 | 3 (2.5, 4.5) | 0.578 | 12 | 3 (2.3, 4.8) | 14 | 3.5 (2.8, 5) | 0.619 |

| Pregnancy gestation (wk) | 21 | 38.9 (36.6, 39.5) | 13 | 39 (38.1, 39.3) | 0.581 | 12 | 38.9 (36.4, 39.9) | 14 | 39.1 (38.2, 39.5) | 0.752 |

| HCV viral load (log10 IU/mL) | ||||||||||

| Third trimester | 21 | 5.8 (5.5, 6.8) | 13 | 6.0 (5.5, 7.0) | 0.807 | 12 | 6.1 (5.4, 6.6) | 14 | 6.4 (5.7, 7) | 0.322 |

| ALT (U/L) | ||||||||||

| Third trimester | 21 | 29.5 (21.5, 45.8) | 13 | 30 (14, 52.5) | 0.814 | 12 | 33.5 (20.8, 46.8) | 14 | 29.5 (17, 61.4) | 0.990 |

| 3-mo postpartum | 21 | 80 (55.5, 147) | 13 | 37 (21.5, 107) | 0.056 | 12 | 95 (57.3, 237) | 14 | 61.5 (23.8, 103) | 0.078 |

| 6-mo postpartum | 15 | 84 (26, 114) | 11 | 33 (23, 112) | 0.356 | 12 | 93.5 (25.3, 116) | 14 | 36 (23, 91) | 0.494 |

| ELISpot magnitude (EM) | ||||||||||

| Third trimester | 21 | 50 (0, 173.8) | 11 | 70 (0, 325) | 0.502 | 12 | 83.8 (0, 190) | 12 | 113.1 (0, 324) | 0.545 |

| 3-mo postpartum | 17 | 127.5 (0, 299) | 13 | 350 (119, 619) | 0.026 | 8 | 63.8 (0, 167) | 14 | 361.3 (72.5, 579) | 0.055 |

| ΔEM 3 mo* | 17 | 0 (0, 167.5) | 11 | 132.5 (60, 378) | 0.129 | 8 | 6.3 (-60, 145) | 12 | 110 (1.6, 348) | 0.173 |

| 6-mo postpartum | 12 | 0 (0, 93.8) | 7 | 1030 (220, 1380) | 0.0002 | 10 | 27.5 (0, 108) | 9 | 320 (36.3, 1310) | 0.024 |

| ΔEM 6 mo* | 12 | −10 (106, 0) | 6 | 192 (-3.1, 1380) | 0.005 | 10 | −27.5 (-111, 0) | 8 | 83.1 (0, 1090) | 0.006 |

| ELISpot breadth (EB) | ||||||||||

| Third trimester | 21 | 1 (0, 1.5) | 11 | 1 (0, 4) | 0.420 | 12 | 1 (0, 1.8) | 12 | 1 (0, 4) | 0.472 |

| 3-mo postpartum | 17 | 1 (0, 2) | 13 | 4 (1.5, 6) | 0.005 | 8 | 0.5 (0, 2) | 14 | 3.5 (1, 6) | 0.044 |

| ΔEB 3 mo* | 17 | 0 (0, 1.5) | 11 | 2 (0, 2) | 0.078 | 8 | 0 (-0.8, 2) | 12 | 1 (0, 2) | 0.311 |

| 6-mo postpartum | 12 | 0 (0, 1) | 7 | 4 (3, 8) | 0.0002 | 10 | 0.5 (0, 1.3) | 9 | 3 (0.5, 7) | 0.024 |

| ΔEB 6 mo* | 12 | 0 (0, 0) | 6 | 2.5 (-0.3, 5) | 0.056 | 10 | 0 (-0.5, 0.3) | 8 | 1 (0, 3.8) | 0.121 |

| New ELISpot responses† | ||||||||||

| 3-mo postpartum | 17 | 0 (0, 2) | 11 | 2 (1, 3) | 0.025 | 8 | 0 (0, 2) | 12 | 1.5 (1, 2.8) | 0.162 |

| 6-mo postpartum | 12 | 0 (0, 0) | 6 | 2.5 (0.8, 5) | 0.002 | 10 | 0 (0, 0.3) | 8 | 1.5 (0, 3.8) | 0.047 |

| Viral genotype | ||||||||||

| 1 | 15 | 6 | 0.141 | 8 | 7 | 0.391 | ||||

| 2 or 3 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7 | ||||||

| IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype | ||||||||||

| CC | 7 | 7 | 0.238 | 3 | 9 | 0.045 | ||||

| CT or TT | 14 | 6 | 9 | 5 | ||||||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||||||

| Cesarean | 3 | 6 | 0.057 | 2 | 6 | 0.216 | ||||

| Vaginal | 18 | 7 | 10 | 8 | ||||||

| Breastfed ever | ||||||||||

| Yes | 8 | 5 | 0.983 | 5 | 6 | 0.951 | ||||

| No | 13 | 8 | 7 | 8 | ||||||

| Breastfed ≥ 4 wk | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 5 | 0.709 | 4 | 5 | 1 | ||||

| No | 15 | 8 | 8 | 9 | ||||||

Boldface entries indicate P < 0.05.

Δ indicates difference between third trimester and postpartum values (e.g., value3 mo postpartum – valuethird trimester).

Number of HCV peptide pools that had negative ELISpot responses in the third trimester and positive responses at the indicated postpartum time point.

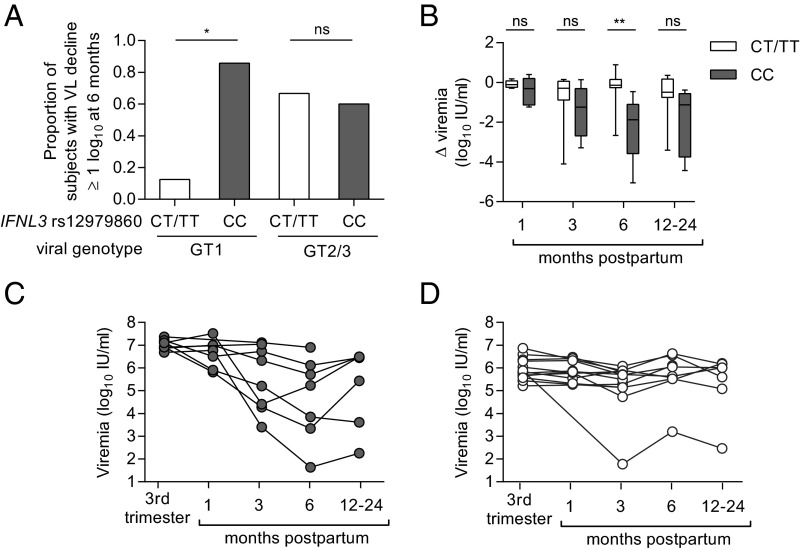

The potential association of rs12979860 genotype CC with postpartum viral control is congruent with its associations with resolution of acute HCV infection and response to interferon treatment (11–13). Although a significant effect of IFNL3 genotype CC was seen across the cohort (Table S2), it was especially pronounced in subjects with genotype 1 infection (Fig. 3A), the most prevalent HCV genotype in our cohort and globally (21). Among genotype 1-infected subjects, 86% (6 of 7) with IFNL3 CC experienced a postpartum viral load decline of at least 1 log10 IU/mL at 6 mo, compared with only 13% (1 of 8) with IFNL3 CT or TT (Fig. 3A). We did not observe an effect of IFNL3 genotype on viral control in the smaller subset of mothers with viral genotypes 2 and 3 (Fig. 3A), but effects of IFNL3 polymorphisms are also known to be less apparent for IFN treatment response rates in genotype 2 and 3 infections (22). Although the CC genotype favors spontaneous resolution of acute HCV infection, it is also associated with higher viral loads in nonpregnant adults who develop persistent infection (13, 23). The same seems to hold true in late pregnancy, where individuals with CC genotype and virus genotype 1 had significantly higher viral loads than CT/TT mothers (Fig. 3 C and D and Fig. S4A). This finding could be clinically relevant because high viral loads in pregnancy have been linked to an increased risk of mother-to-child transmission of HCV in some studies (24, 25). Nevertheless, by 6-mo postpartum a greater proportion of CC mothers experienced a substantial drop in viremia, shifting the median viral load of CC mothers below that of CT/TT mothers at that time point (Fig. 3 B–D and Fig. S4A). The mechanism by which polymorphisms at rs12979860 might contribute to control of HCV after pregnancy is not clear. The rs12979860 SNP itself may not be functional; rather, its effect appears to be mediated by other closely linked IFN-λ polymorphisms, including the IFNL4 ΔG/TT variant rs368234815 (26, 27). The ΔG frameshift variant permits production of the novel protein IFN-λ4, which is paradoxically associated with impaired resolution of HCV infection (26, 27). In our cohort, the favorable IFNL3 rs12979860 C allele was in 100% linkage disequilibrium with the favorable IFNL4 rs368234815 TT allele (Table S1). The favorable IFNL3/4 genotype did not appear to be associated with HCV-specific T-cell IFN-γ responses, even for the subset with genotype 1 infection (Fig. S4 B and C), suggesting that it might act independently of T-cells to mediate postpartum viral control. Outside of pregnancy, studies of chronically infected individuals have also failed to detect an effect of IFNL3 polymorphisms on HCV-specific T-cell responses (28, 29).

Fig. 3.

Influence of IFNL3 rs12979860 polymorphism on HCV viremia during and after pregnancy. (A) Effect of IFNL3 genotype and viral genotype on achievement of 1 log10 IU/mL viral load decline by 3-mo postpartum (Fisher’s exact test). (B) Change in viral load relative to third trimester for 21 genotype 1-infected women parsed by IFNL3 genotype (Mann–Whitney U test). (C and D) Individual courses of viremia in genotype 1-infected women with IFNL3 genotype CC (C) or CT or TT (D). P value summary: ns, P ≥ 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Fig. S4.

Influence of IFNL3 rs12979860 polymorphism on viral load (A) and breadth (B) and magnitude (C) of longitudinal HCV-specific T-cell responses as measured by IFN-γ ELISpot in genotype 1 infected subjects (Mann–Whitney U test). P value summary: ns, P ≥ 0.05; *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001.

Given the apparent association of HCV-specific T-cell responses with viral control after pregnancy, we extended the search for genetic determinants of postpartum viral control to include HLA class I and II genes. Among 46 class I and 62 class II allelic variants in our cohort, HLA-C*07:02, -DPB1*03:01, and -DPB1*04:01 exhibited associations with a 1 log10 reduction in viral load at 3- or 6-mo postpartum. The HLA-C*07:02 and -DPB1*03:01 associations were not significant after permutation-resampling adjustment for multiple comparisons. Importantly, a negative association of HLA-DPB1*04:01 remained significant; subjects with expression of this class II HLA allele were less likely to control HCV replication at 3-mo postpartum (unadjusted P = 0.0014, adjusted P = 0.013) (Tables S3 and S4).

Table S3.

HLA class I associations with 1 log10 decline in viremia at 3- or 6-mo postpartum

| Viral load decline: Third trimester to 3-mo postpartum | Viral load decline: Third trimester to 6-mo postpartum | |||||||

| HLA allele | <1 log10 IU/mL (n = 21), % | ≥1 log10 IU/mL (n = 13), % | P | P-adjusted | <1 log10 IU/mL (n = 12), % | ≥1 log10 IU/mL (n = 14), % | P | P-adjusted |

| A*01:01 | 38 | 23 | 0.465 | 1 | 25 | 29 | 1 | 1 |

| A*02:01 | 57 | 46 | 0.725 | 1 | 75 | 50 | 0.248 | 1 |

| A*03:01 | 38 | 15 | 0.251 | 0.999 | 25 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| A*11:01 | 14 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| A*23:01 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| A*24:02 | 10 | 23 | 0.348 | 1 | 17 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| A*25:01 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| A*26:01 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| A*29:02 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| A*30:01 | 0 | 15 | 0.139 | 0.997 | 0 | 14 | 0.483 | 1 |

| A*31:01 | 5 | 15 | 0.544 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 0.483 | 1 |

| A*32:01 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| A*36:01 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| A*68:01 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| B*07:02 | 43 | 15 | 0.14 | 0.997 | 58 | 21 | 0.105 | 0.962 |

| B*08:01 | 14 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| B*13:02 | 5 | 15 | 0.544 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 0.483 | 1 |

| B*15:01 | 29 | 31 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 36 | 0.391 | 1 |

| B*15:10 | 0 | 8 | 0.382 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| B*15:18 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| B*18:01 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| B*35:01 | 10 | 15 | 0.627 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 0.483 | 1 |

| B*35:03 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| B*38:01 | 0 | 15 | 0.139 | 0.997 | 0 | 14 | 0.483 | 1 |

| B*39:01 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| B*39:06 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| B*40:01 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| B*40:02 | 10 | 0 | 0.513 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0.203 | 1 |

| B*44:02 | 24 | 15 | 0.682 | 1 | 17 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| B*44:03 | 10 | 0 | 0.513 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| B*45:01 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| B*51:01 | 10 | 15 | 0.627 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 0.225 | 1 |

| B*55:01 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0.203 | 1 |

| B*57:01 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| C*02:02 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| C*03:03 | 29 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| C*03:04 | 10 | 15 | 0.627 | 1 | 8 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| C*04:01 | 24 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| C*05:01 | 24 | 15 | 0.682 | 1 | 17 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| C*06:02 | 10 | 23 | 0.348 | 1 | 8 | 21 | 0.598 | 1 |

| C*07:01 | 14 | 23 | 0.653 | 1 | 17 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| C*07:02 | 52 | 23 | 0.153 | 0.998 | 75 | 29 | 0.047 | 0.564 |

| C*07:04 | 5 | 15 | 0.544 | 1 | 8 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| C*12:03 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| C*15:02 | 10 | 15 | 0.627 | 1 | 8 | 21 | 0.598 | 1 |

| C*16:01 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

Boldface entries indicate P < 0.05.

Table S4.

HLA class II associations with 1 log10 decline in viremia at 3- or 6-mo postpartum

| Viral load decline: Third trimester to 3-mo postpartum | Viral load decline: Third trimester to 6-mo postpartum | |||||||

| HLA Allele | <1 log10 IU/mL (n = 21) % | ≥1 log10 IU/mL (n = 13), % | P | P-adjusted | <1 log10 IU/mL (n = 12), % | ≥1 log10 IU/mL (n = 14), % | P | P-adjusted |

| DRB1*01:01 | 24 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 29 | 0.33 | 1 |

| DRB1*01:02 | 0 | 8 | 0.382 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DRB1*03:01 | 24 | 15 | 0.682 | 1 | 33 | 14 | 0.365 | 1 |

| DRB1*04:01 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| DRB1*04:03 | 0 | 8 | 0.382 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DRB1*04:04 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| DRB1*04:07 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| DRB1*07:01 | 29 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 42 | 21 | 0.401 | 1 |

| DRB1*09:01 | 0 | 8 | 0.382 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DRB1*10:01 | 0 | 8 | 0.382 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DRB1*11:01 | 10 | 23 | 0.348 | 1 | 8 | 21 | 0.598 | 1 |

| DRB1*11:04 | 0 | 15 | 0.139 | 0.997 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DRB1*13:01 | 24 | 8 | 0.37 | 1 | 17 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| DRB1*13:02 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0.203 | 1 |

| DRB1*14:01 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DRB1*14:54 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 0.483 | 1 |

| DRB1*15:01 | 38 | 15 | 0.251 | 0.999 | 42 | 21 | 0.401 | 1 |

| DRB1*16:01 | 10 | 0 | 0.513 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| DRB3*01:01 | 29 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 33 | 21 | 0.665 | 1 |

| DRB3*02:02 | 38 | 54 | 0.484 | 1 | 33 | 57 | 0.267 | 1 |

| DRB3*03:01 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0.203 | 1 |

| DRB4*01:01 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 7 | 0.58 | 1 |

| DRB4*01:03 | 38 | 46 | 0.728 | 1 | 33 | 43 | 0.702 | 1 |

| DRB5*01:01 | 38 | 15 | 0.251 | 0.999 | 42 | 21 | 0.401 | 1 |

| DRB5*02:02 | 10 | 0 | 0.513 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| DQB1*02:01 | 24 | 15 | 0.682 | 1 | 33 | 14 | 0.365 | 1 |

| DQB1*02:02 | 19 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| DQB1*03:01 | 19 | 46 | 0.13 | 0.959 | 25 | 36 | 0.683 | 1 |

| DQB1*03:02 | 14 | 23 | 0.653 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 0.225 | 1 |

| DQB1*03:03 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 7 | 0.58 | 1 |

| DQB1*05:01 | 24 | 38 | 0.451 | 1 | 8 | 43 | 0.081 | 0.785 |

| DQB1*05:02 | 10 | 0 | 0.513 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| DQB1*05:03 | 10 | 15 | 0.627 | 1 | 8 | 21 | 0.598 | 1 |

| DQB1*06:02 | 38 | 15 | 0.251 | 0.999 | 42 | 21 | 0.401 | 1 |

| DQB1*06:03 | 24 | 0 | 0.132 | 0.968 | 17 | 7 | 0.58 | 1 |

| DQB1*06:04 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0.203 | 1 |

| DQA1*01:01 | 24 | 31 | 0.704 | 1 | 8 | 36 | 0.17 | 0.987 |

| DQA1*01:02 | 52 | 23 | 0.153 | 0.998 | 58 | 21 | 0.105 | 0.962 |

| DQA1*01:03 | 24 | 0 | 0.132 | 0.968 | 17 | 7 | 0.58 | 1 |

| DQA1*01:04 | 10 | 15 | 0.627 | 1 | 8 | 21 | 0.598 | 1 |

| DQA1*01:05 | 0 | 8 | 0.382 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DQA1*02:01 | 29 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 42 | 21 | 0.401 | 1 |

| DQA1*03:01 | 14 | 23 | 0.653 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 0.225 | 1 |

| DQA1*03:02 | 0 | 8 | 0.382 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DQA1*03:03 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 7 | 0.58 | 1 |

| DQA1*05:01 | 24 | 15 | 0.682 | 1 | 33 | 14 | 0.365 | 1 |

| DQA1*05:05 | 10 | 38 | 0.079 | 0.905 | 8 | 29 | 0.33 | 1 |

| DPB1*01:01 | 19 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| DPB1*02:01 | 29 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| DPB1*03:01 | 0 | 23 | 0.048 | 0.761 | 0 | 21 | 0.225 | 1 |

| DPB1*04:01 | 81 | 23 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 83 | 36 | 0.021 | 0.266 |

| DPB1*04:02 | 19 | 46 | 0.13 | 0.959 | 8 | 43 | 0.081 | 0.785 |

| DPB1*05:01 | 0 | 15 | 0.139 | 0.997 | 0 | 14 | 0.483 | 1 |

| DPB1*06:01 | 5 | 23 | 0.274 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DPB1*10:01 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| DPB1*11:01 | 0 | 15 | 0.139 | 0.997 | 0 | 14 | 0.483 | 1 |

| DPB1*14:01 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| DPA1*01:03 | 100 | 92 | 0.382 | 1 | 100 | 93 | 1 | 1 |

| DPA1*01:05 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0.462 | 1 |

| DPA1*02:01 | 29 | 54 | 0.168 | 0.998 | 33 | 57 | 0.267 | 1 |

| DPA1*02:02 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| DPA1*03:01 | 0 | 8 | 0.382 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

Boldface entries indicate P < 0.05.

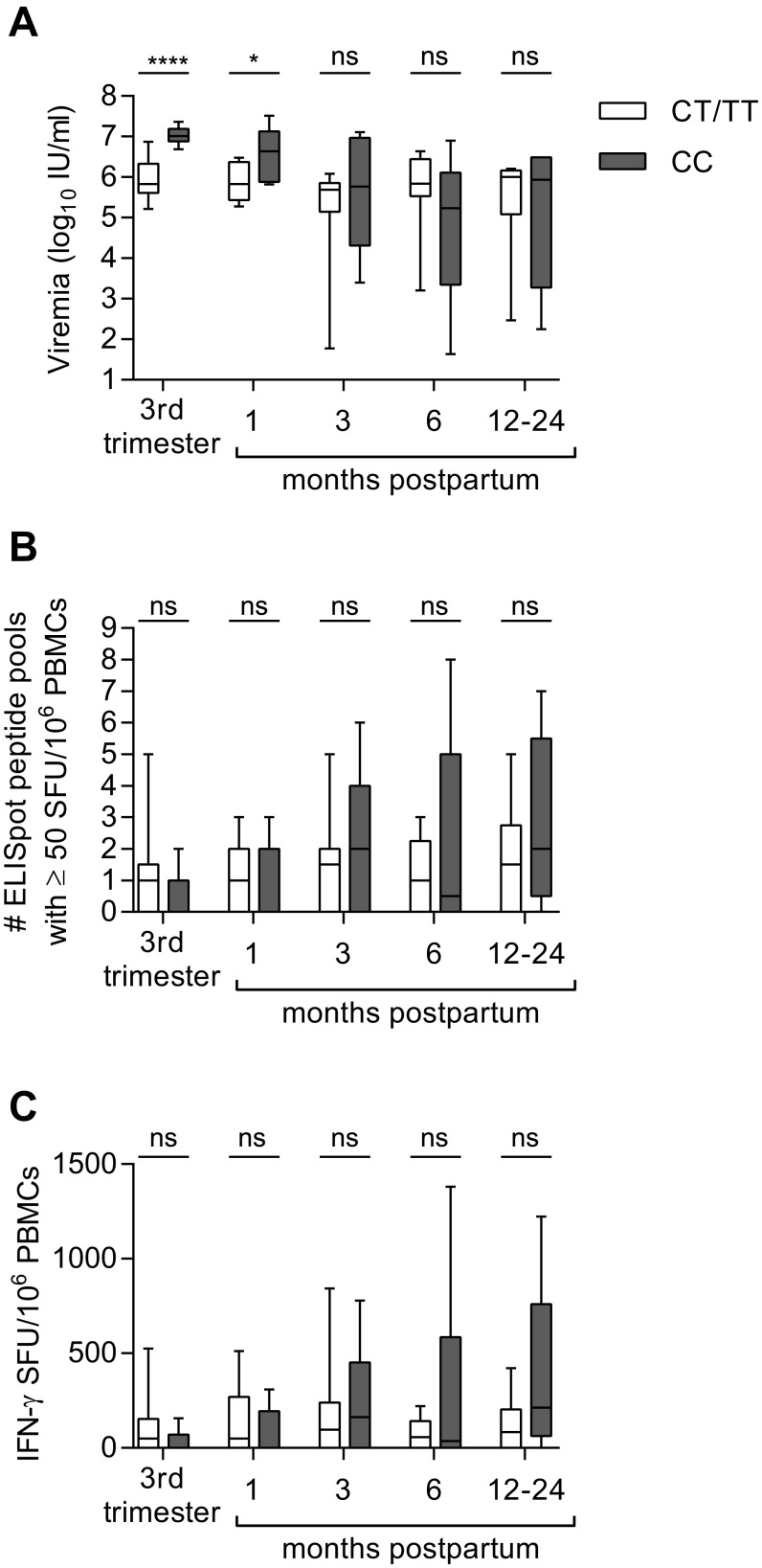

HLA-DPB1 alleles can be grouped by high or low patterns of expression (30, 31) that influence organ rejection after transplantation (31) and the outcome of hepatitis B virus infection (30, 32). HLA-DPB1*04:01 is classified as a low-expression allele. We therefore assessed whether the HLA-DPB1 locus had a more pervasive influence on virus control based on known allelic expression patterns. Thirteen subjects were homozygous for low-expression DPB1 alleles, one subject was homozygous for high-expression alleles, and the remaining 20 were heterozygous (Fig. 4A). Thirteen (62%) of 21 individuals with at least one high-expression HLA-DPB1 allele achieved a 1 log10 decline in viremia by 3-mo postpartum, whereas none of the 13 individuals who lacked high-expression HLA-DPB1 alleles met this threshold (P = 0.0002, Fisher’s exact test). This association of DP expression with viral control was stronger than the association for HLA-DPB1*04:01 (unadjusted P = 0.0014). Unlike IFNL3, high DP expression did not affect median viral load during pregnancy, but rather was associated with substantially lower absolute viral loads at 3-, 6-, and 12- to 24-mo postpartum (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Influence of expected HLA-DPB1 expression on HCV viremia and HCV-specific T-cell responses during and after pregnancy. (A) Comparison of change in viral load from third trimester to 3-mo postpartum among women categorized by their number of high-expression HLA-DPB1 alleles. (B–D) Longitudinal differences in viral load (B) and HCV-specific IFN-γ ELISpot breadth (C) and magnitude (D) between women with (gray shaded) and without (white shaded) at least one high-expression HLA-DPB1 allele. P value summary: ns, P ≥ 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Importantly, women with high-expression HLA-DPB1 alleles exhibited greater breadth and frequency of HCV-specific T-cell responses at 6-mo postpartum (P = 0.0027, P = 0.0015), with at least a trend toward stronger responses in late pregnancy, 3-mo postpartum, and 12- to 24-mo postpartum (P < 0.1 at each timepoint) (Fig. 4 C and D). Given this association, it is plausible that high expression of class II HLA-DPB1 alleles contributes directly to recovery of HCV-specific CD4+ T-cell immunity in the postpartum period. The mechanisms by which high-expression DPB1 alleles might mediate this effect are unknown. These alleles may present a unique set of protective HCV class II epitopes, but this seems unlikely as common HLA-DPB1 alleles appear to bind a similar repertoire of antigenic peptides regardless of high- or low-expression pattern (33). It is possible that the level of HLA-DPB1 expression influences the expansion, differentiation status, or effector function of CD4+ T cells after pregnancy. Such a possibility has been suggested for the impact of HLA-DPB1 on the outcome of hepatitis B virus infection (30).

The HLA-DPB1 locus has not been previously linked to control of HCV replication or infection outcome. It is unknown whether HLA-DP contributes to HCV control overall, or whether HLA-DP is perhaps specially regulated during pregnancy or the postpartum period. It will be important to confirm its effect in other cohorts of HCV-infected pregnant women and also to assess whether it affects the outcome of acute HCV infection in nonpregnant individuals, where most prior HLA association studies did not include HLA-DP typing (17, 34, 35). One recent study did identify HLA-DP haplotypes linked to HCV outcomes in Han Chinese populations, although the effect appeared to be driven primarily by variation in HLA-DPA1 rather than HLA-DPB1 (36).

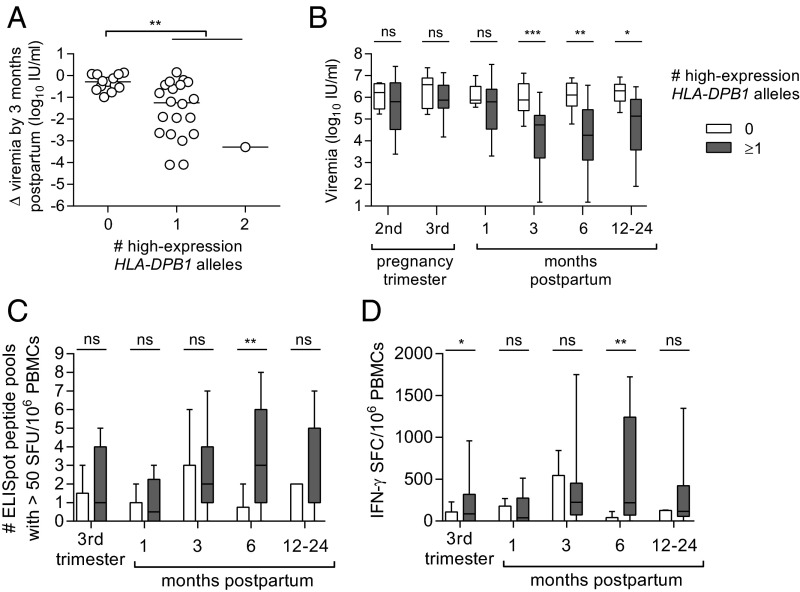

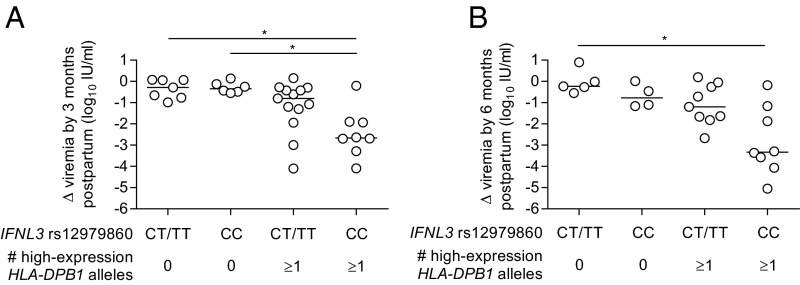

Prior studies of IFNL3 genotype and HLA class II alleles (HLA-DR and HLA-DQ) in acute HCV infection found their effects to be independent and additive (11, 35). IFNL3 and HLA-DPB1 genotypes may have analogous effects in the postpartum period (Fig. 5). Multivariable linear regression analysis incorporating both IFNL3 rs12979860 CC and presence of a high-expression HLA-DPB1 allele identified independent effects of each genetic variable on viral load decline at 3-mo (P = 0.046 and P < 0.001, respectively) and 6-mo postpartum (P = 0.006 and P = 0.003, respectively) (model 1 in Table 2). IFNL3 effects on viral control appeared most prominent in women possessing a high-expression HLA-DPB1 allele (Fig. 5), suggesting a possible synergistic interaction, but an interaction variable added to the linear regression model did not meet significance at 3- or 6-mo postpartum. Because IFNL3 effects on viral control at 6-mo postpartum had been most evident in the subset of women infected with HCV genotype 1 (Fig. 3A), we examined a model incorporating viral genotype, IFNL3, and HLA-DPB1 (model 2 in Table 2). In this model, IFNL3 and HLA-DPB1 retained their effects on viral control and viral genotype was not a significant factor.

Fig. 5.

Combined effect of IFNL3 rs12979860 and HLA-DPB1 on change in viral load from third trimester to 3-mo (A) and 6-mo (B) postpartum (Kruskall–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparison test). P value summary: *P < 0.05.

Table 2.

Multivariable linear regression models of decline in log10-viral load by 3- and 6-mo postpartum

| Model | Viral load decline third trimester to 3-mo postpartum | Viral load decline third trimester to 6-mo postpartum | ||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P | Coefficient (95% CI) | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype CC | 0.73 (0.01, 1.45) | 0.046 | 1.36 (0.44, 2.27) | 0.006 |

| ≥1 high expression HLA-DPB1 allele | 1.39 (0.66, 2.12) | <0.001 | 1.55 (0.59, 2.51) | 0.003 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype CC | 0.73 (-0.01, 1.46) | 0.053 | 1.35 (0.42, 2.29) | 0.007 |

| ≥1 high-expression HLA-DPB1 allele | 1.37 (0.61, 2.14) | 0.001 | 1.61 (0.59, 2.65) | 0.004 |

| HCV genotype 1 | −0.06 (−0.83, 0.71) | 0.875 | −0.22 (−0.77, 1.21) | 0.649 |

CI, confidence interval.

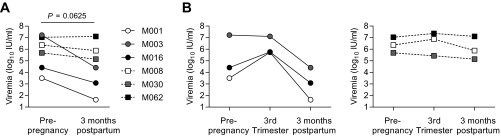

The study does have limitations. Our findings indicate that the drop in virus load after pregnancy was associated with enhanced T-cell immunity, a favorable IFNL3 genotype, and high HLA-DPB1 expression. High antigen loads contribute to T-cell exhaustion (37). It is therefore possible that reduced virus replication after pregnancy caused or contributed to reversal of T-cell exhaustion. We do not favor this interpretation, given the association of viral control with an HLA locus responsible for antigen presentation to T-cells (Fig. 4), our prior evidence for enhanced T-cell selection pressure on viral genomes after delivery (10), and the biological plausibility of postpartum T-cell recovery following pregnancy (38). It should also be emphasized that women were enrolled during late pregnancy, so it was not possible to formally test whether postpartum viral loads were lower than baseline prepregnancy values. Several findings do suggest, however, that the 3–6 mo after delivery did in fact constitute a period of uniquely enhanced viral control and not just a return to baseline control. Among six women in whom we were able to identify prepregnancy viral loads, five of them had lower viral loads at 3-mo postpartum than before pregnancy (P = 0.063) (Fig. S5), including all three mothers who achieved a 1 log10 postpartum viral load reduction (Fig. S5B). Viral loads in the postpartum period were also lower than would be expected for “baseline” levels in chronic infection. At 3- and 6-mo postpartum, nearly 45% of women had viral loads below 105 IU/mL, whereas normally only 8–13% of chronically infected individuals have such low-level viremia, although admittedly the proportion with low-level viremia may be slightly greater among young women (5, 39). Furthermore, the IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype CC is normally associated with higher viral loads in chronic HCV infection (13, 23), but at 6-mo postpartum it was associated with numerically lower viral loads (Fig. S3A).

Fig. S5.

(A) Comparison of HCV viremia before pregnancy and 3 mo after delivery among the six subjects who had prepregnancy samples available (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). (B) HCV viremia before, during, and 3-mo after pregnancy for the same six women, divided by whether (Left) or not (Right) they achieved a 1 log10 postpartum viral load decline.

In conclusion, we have found that HCV-specific T-cell responses and IFNL3 genotype, two factors governing spontaneous resolution of acute HCV infection, are also determinants of postpartum immune control in persistent HCV infection. Furthermore, we have identified an association of HLA-DPB1 expression with postpartum viral control and T-cell recovery. These findings support the notion that the postpartum period provides a unique opportunity for understanding mechanisms of spontaneous recovery of dysfunctional immune responses to chronic viral pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Samples.

Pregnant women with hepatitis C viremia were recruited from The Ohio State University Substance Treatment Education and Prevention Program, which provides multidisciplinary prenatal care for women with histories of substance abuse. Several additional subjects were enrolled from other university prenatal clinics, the labor and delivery unit, and a satellite site in Portsmouth, Ohio. All subjects provided informed consent before participation in the study. Peripheral blood collection time points included the third trimester (range: 27-wk gestation through the delivery hospitalization) and 1, 3, 6, and 12–24 mo after delivery. When available, pre-enrollment viral load and ALT data were collected from the Ohio State University clinical laboratory to determine prepregnancy and second-trimester values. Thirty-four HCV-monoinfected women (negative for HIV antibody and hepatitis B surface antigen) with follow-up visits through at least 3-mo postpartum were included in this analysis. One subject was African American; the remaining 33 subjects were European American. Other demographics are provided in Table 1 and Table S1. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of The Ohio State University and Nationwide Children’s Hospital and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Viral load.

Concentrations of HCV-RNA in EDTA plasma were measured by the Roche Taqman COBAS RT-PCR. Logarithmic-10 transformed values of viral load were used in statistical analyses.

Viral genotype.

Viral genotype/subtype was determined by the line probe assay (LiPA 2.0 HCV Genotype, Siemens) or through RT-PCR and direct sequencing of the 5′UTR.

HCV Peptides and IFN-γ ELISpot.

HCV-specific T-cell responses were quantified using the IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay. Briefly, EDTA PBMCs isolated by Ficoll (Sigma-Aldrich) gradient centrifugation were suspended in AIM-V lymphocyte medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% (vol/vol) human AB serum (Gemini-BioScience) and plated at 200,000 cells per well in 96-well polyvinylidene fluoride plates (Millipore) precoated with anti-human IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (U-Cytech). PBMCs were stimulated with arrays of overlapping peptides divided into nine pools spanning the entire HCV polyprotein (Fig. S1) at a concentration of 1 μg/mL per peptide. HCV peptide arrays were selected to match the subject’s HCV genotype and included sets corresponding to viral strains H77 and 1/910 (genotype 1a), J4/91 (genotype 1b), a genotype 2a consensus sequence (used for subjects with genotype 2a or 2b viruses), and K3a/650 (genotype 3a). Peptides in these sets were 15–20 amino acids in length and overlapped by 10–12 residues. Samples were tested in duplicate along with phytohemagglutinin positive controls and no-antigen negative controls. Plates were incubated for 36–44 h at 37 °C in 7.5% CO2 and developed according to manufacturer’s instructions [Human IFN-γ ELISpot kit (black spots); U-Cytech]. Spot counts were determined by an automated ELISpot plate reader using Immunospot 5.0 Professional software with background-adjusted sensitivity settings (Cellular Technology). Duplicate counts were averaged, and positive responses to HCV peptide pools were defined as those having counts at least 10 spot-forming units per well above the negative control. Assays with averaged negative control background counts in excess of 10 spot-forming units per well were excluded.

IFNL3 rs12979860 and IFNL4 rs368234815 Genotype.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from donor-derived B lymphoblastoid cell-lines using the Qiagen REPLI-g mini kit (Qiagen). Genotypes were determined by Taqman allelic discrimination assay using previously described primers and probes for IFNL3 rs12979860 (40) and the following primer/probe combination for IFNL4 rs368234815: forward primer 5′-TGCTGCAGAAGCAGAGATGC-3′, reverse primer 5′-GCTCCAGCGAGCGGTAGTG-3′; 5′-VIC-CACGGTGATCGCAGAAGGCC-3′ and 5′-FAM-ACGGTGATCGCAGCGGCC-3′ (Life Technologies). All samples were run in duplicate using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR instrument. Genotypes were auto-called by SDS 1.2 software (Applied Biosystems) with a 0.900 minimum confidence value.

HLA typing.

High-resolution HLA typing was performed at the University of Oklahoma Health Science Center by sequence-based typing (SBT) as previously described (41).

Statistical Analyses.

Differences between groups were determined by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests or the Kruskall–Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons for continuous variables, and χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables. Changes over time within individuals were assessed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. HLA class I and class II associations with viral control at 3- and 6-mo postpartum were determined by Fisher’s exact test with adjustment for multiple comparisons by permutation-resampling. Permutation adjustment was selected as a nonparametric procedure useful in cases with a large number of dependent comparisons such as for HLA associations that is not as overly stringent as common adjustment procedures, such as the Bonferroni correction. The data were resampled without replacement 100,000 times, and a P value was computed for each new sample. The P values from the resampled datasets then formed the distribution of P values that would be expected given no difference by viral control. The observed P value was then compared with the estimated distribution to determine the chance for false significance (Type 1 error), accounting for multiple testing as well as the correlation among each of the different tests. A multiplicity adjusted P value <0.05 indicates that there is less than a 5% chance that the difference would occur by chance alone. Multivariable linear regression was used to test for additive versus synergistic effects of IFNL3 and HLA-DPB1 on degree of postpartum log10 viral load decline. For mothers followed through two consecutive pregnancies (M001, M003, M016, M024, and M040), the second pregnancy was used for statistical analysis. Calculations were completed in GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software) and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Hunkler of the Nationwide Children’s Hospital Family AIDS Clinic and Education Services, M. Irwin and staff of The Counseling Center of Portsmouth, Ohio, and J. Stone of the Southern Ohio Medical Center maternity ward for their project coordination efforts; Wei Wang for statistical support; and the subjects for their participation in this longitudinal study. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health Grants R37-AI47367 (to C.M.W.), R56-AI096882 and R01-AI096882 (to C.M.W. and J.R.H.), T32-HD043003 and K12-HD043372 (to J.R.H.), and R01AI070101, 1R21AI118337, and R01AI124680 (to A.G.); The Ohio State University Clinical and Translational Science Award Grants UL1TR001070 and ORIP/OD P51OD011132 (formerly NCRR P51RR000165) to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center; and the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (C.M.W. and J.R.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1602337113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rehermann B. Hepatitis C virus versus innate and adaptive immune responses: A tale of coevolution and coexistence. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(7):1745–1754. doi: 10.1172/JCI39133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowen DG, Walker CM. Adaptive immune responses in acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2005;436(7053):946–952. doi: 10.1038/nature04079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowen DG, Walker CM. Mutational escape from CD8+ T cell immunity: HCV evolution, from chimpanzees to man. J Exp Med. 2005;201(11):1709–1714. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulze Zur Wiesch J, et al. Broadly directed virus-specific CD4+ T cell responses are primed during acute hepatitis C infection, but rapidly disappear from human blood with viral persistence. J Exp Med. 2012;209(1):61–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGovern BH, et al. Improving the diagnosis of acute hepatitis C virus infection with expanded viral load criteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(7):1051–1060. doi: 10.1086/605561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin HH, Kao JH. Hepatitis C virus load during pregnancy and puerperium. BJOG. 2000;107(12):1503–1506. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paternoster DM, et al. Viral load in HCV RNA-positive pregnant women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(9):2751–2754. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gervais A, et al. Decrease in serum ALT and increase in serum HCV RNA during pregnancy in women with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2000;32(2):293–299. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Extremera A, et al. Variation of transaminases, HCV-RNA levels and Th1/Th2 cytokine production during the post-partum period in pregnant women with chronic hepatitis C. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honegger JR, et al. Loss of immune escape mutations during persistent HCV infection in pregnancy enhances replication of vertically transmitted viruses. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1529–1533. doi: 10.1038/nm.3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duggal P, et al. Genome-wide association study of spontaneous resolution of hepatitis C virus infection: Data from multiple cohorts. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):235–245. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas DL, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461(7265):798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge D, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461(7262):399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt J, Thimme R, Neumann-Haefelin C. Host genetics in immune-mediated hepatitis C virus clearance. Biomarkers Med. 2011;5(2):155–169. doi: 10.2217/bmm.11.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKiernan SM, et al. Distinct MHC class I and II alleles are associated with hepatitis C viral clearance, originating from a single source. Hepatology. 2004;40(1):108–114. doi: 10.1002/hep.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thio CL, et al. HLA-Cw*04 and hepatitis C virus persistence. J Virol. 2002;76(10):4792–4797. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4792-4797.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuniholm MH, et al. Specific human leukocyte antigen class I and II alleles associated with hepatitis C virus viremia. Hepatology. 2010;51(5):1514–1522. doi: 10.1002/hep.23515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong X, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class II DQB1*0301, DRB1*1101 alleles and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus infection: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(46):7302–7307. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i46.7302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wejstål R, Widell A, Norkrans G. HCV-RNA levels increase during pregnancy in women with chronic hepatitis C. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30(2):111–113. doi: 10.1080/003655498750003456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thimme R, et al. Viral and immunological determinants of hepatitis C virus clearance, persistence, and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(24):15661–15668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202608299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messina JP, et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):77–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.27259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rauch A, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment failure: A genome-wide association study. Gastroenterol. 2010;138(4):1338–1345, e1331–e1337. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uccellini L, et al. HCV RNA levels in a multiethnic cohort of injection drug users: Human genetic, viral and demographic associations. Hepatology. 2012;56(1):86–94. doi: 10.1002/hep.25652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mast EE, et al. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and the natural history of HCV infection acquired in infancy. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(11):1880–1889. doi: 10.1086/497701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dal Molin G, et al. Mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: Rate of infection and assessment of viral load and IgM anti-HCV as risk factors. J Med Virol. 2002;67(2):137–142. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prokunina-Olsson L, et al. A variant upstream of IFNL3 (IL28B) creating a new interferon gene IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nat Genet. 2013;45(2):164–171. doi: 10.1038/ng.2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Brien TR, et al. Comparison of functional variants in IFNL4 and IFNL3 for association with HCV clearance. J Hepatol. 2015;63(5):1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bes M, et al. IL28B genetic variation and hepatitis C virus-specific CD4(+) T-cell responses in anti-HCV-positive blood donors. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(12):867–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2012.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grimm D, Neumann-Haefelin C, Kersting N, Blum HE, Thimme R. IL28B genotype and hepatitis C virus specific T cell response. Zeitschrift für Gastroenterologie. 2011;49(01):P4_23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas R, et al. A novel variant marking HLA-DP expression levels predicts recovery from hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2012;86(12):6979–6985. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00406-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersdorf EW, et al. High HLA-DP Expression and graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(7):599–609. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamatani Y, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies variants in the HLA-DP locus associated with chronic hepatitis B in Asians. Nat Genet. 2009;41(5):591–595. doi: 10.1038/ng.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sidney J, et al. Five HLA-DP molecules frequently expressed in the worldwide human population share a common HLA supertypic binding specificity. J Immunol. 2010;184(5):2492–2503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKiernan SM, et al. The MHC is a major determinant of viral status, but not fibrotic stage, in individuals infected with hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(6):1124–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzmaurice K, et al. Irish HCV Research Consortium; Swiss HIV Cohort Study Additive effects of HLA alleles and innate immune genes determine viral outcome in HCV infection. Gut. 2015;64(5):813–819. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu X, et al. Genetic variants in human leukocyte antigen-DP influence both hepatitis C virus persistence and hepatitis C virus F protein generation in the Chinese Han population. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(6):9826–9843. doi: 10.3390/ijms15069826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahan SM, Wherry EJ, Zajac AJ. T cell exhaustion during persistent viral infections. Virology. 2015;479-480:180–193. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh N, Perfect JR. Immune reconstitution syndrome and exacerbation of infections after pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(9):1192–1199. doi: 10.1086/522182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ticehurst JR, Hamzeh FM, Thomas DL. Factors affecting serum concentrations of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in HCV genotype 1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(8):2426–2433. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02448-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urban TJ, et al. IL28B genotype is associated with differential expression of intrahepatic interferon-stimulated genes in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;52(6):1888–1896. doi: 10.1002/hep.23912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lanteri MC, et al. Association between HLA class I and class II alleles and the outcome of West Nile virus infection: An exploratory study. PloS One. 2011;6(8):e22948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]